Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the location-specific tissue properties and age-related changes of the facial fat and facial muscles using quantitative MRI (qMRI) analysis of longitudinal magnetization (T1) and transverse magnetization (T2) values.

Methods:

38 subjects (20 males and 18 females, 0.5–87 years old) were imaged with a mixed turbo-spin echo sequence at 1.5 T. T1 and T2 measurements were obtained within regions of interest in six facial fat regions including the buccal fat and subcutaneous cheek fat, four eyelid fat regions (lateral upper, medial upper, lateral lower and medial lower) and five facial muscles including the orbicularis oculi, orbicularis oris, buccinator, zygomaticus major and masseter muscles bilaterally.

Results:

Within the zygomaticus major muscle, age-associated T1 decreases in females and T1 increases in males were observed in later life with an increase in T2 values with age. The orbicularis oculi muscles showed lower T1 and higher T2 values compared to the masseter, orbicularis oris and buccinator muscles, which demonstrated small age-related changes. The dramatic age-related changes were also observed in the eyelid fat regions, particularly within the lower eyelid fat; negative correlations with age in T1 values (p < 0.0001 for age) and prominent positive correlation in T2 values in male subjects (p < 0.0001 for male × age). Age-related changes were not observed in T2 values within the subcutaneous cheek fat.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates proof of concept using T1 and T2 values to assess age-related changes of the facial soft tissues, demonstrating tissue-specific qMRI measurements and non-uniform ageing patterns within different regions of facial soft tissues.

Keywords: ageing, facial muscles, adipose tissue, magnetic resonance imaging, quantitative evaluation

Introduction

The face is a complex, multifunctional structure responsible for conveying various emotional expressions. The investigations into the mechanisms of facial ageing have revealed a multifactorial process involving a combination of structures with functional and structural changes including loss of elasticity, facial fat atrophy, weakened muscular support and bony remodelling.1–13 These age-related changes ultimately lead to alteration in facial appearance with the characteristic wrinkle formation, deepened facial lines, soft tissue descent and prominence of the lower eyelids associated with an older facial appearance.1,2 Strategies aimed at facial rejuvenation and anti-ageing medicine are part of a growing industry involving cosmetic, reconstructive and rejuvenation procedures. In addition to traditional rejuvenating surgeries, such as facelifts and blepharoplasty, non-invasive procedures aimed at remodelling the skin surface and targeting the deep soft tissues, including the facial fat and muscles, are becoming popular.14–17 Maintaining control of facial volume and conditioning of the facial soft tissues are important targets for non-invasive rejuvenating strategies.

In the maxillofacial plastic surgery, computer-aided modelling tools have become widely available. The image-assisted presurgical assessment and planning, including three dimensional volumetric data, surface topography and reconstruction of the defects using the mirror image, improves success of surgery.18,19 Therefore, advanced imaging modalities could play a more important role in the pre- and post-treatment evaluation of patients undergoing anti-ageing procedures of the face. Since the appearance of the face is one of the most important measures for the evaluation of facial ageing, many studies have attempted to use qualitative measures to evaluate the progression of facial ageing and the response to rejuvenation treatments via the use of facial photographs as a primary assessment tool.3,4,20–22 Few radiology studies have been used for the assessment of facial ageing. CT has been used to evaluate age-related changes in deeper facial structures such as facial bones.6–12,23 Other studies have examined age-related volumetric changes in the facial soft tissue and described an increase in the orbital fat and lower eyelid fat, as well as selective atrophy in the cheek fat associated with increasing patient age.1,24–27 While prior studies have described the repositioning of facial soft tissues and the volume changes in the facial fat as primary contributors to the appearance of an older face, it is also possible that specific, age-related changes in facial tissue properties also contribute to the findings associated with an older appearing face.

When considering anti-ageing evaluation, CT has the disadvantage of using ionizing radiation, whereas MRI is a non-invasive, free of ionizing radiation assessment tool with much higher soft tissue contrast resolution and provides both qualitative and quantitative data. The soft tissue relaxation times of the longitudinal magnetization (T1) and the transverse magnetization (T2) are primarily determined by 1H-protonic content and mobility, tissue structure and chemical composition. The primary MR relaxation mechanisms include nuclear magnetic dipole–dipole interactions between the protons of water and macromolecules.28 T1 relaxation time, or spin–lattice relaxation time, reflects interaction between hydrogen protons and the surrounding structure and is longer in free water and shorter in soft tissue where water interacts with macromolecules (proteins, lipids). T2 relaxation time, also known as spin–spin relaxation time, is a time constant characterizing the signal decay and is longer in free water and shorter in bound water. T1 and T2 relaxation times represent different biophysical information, while T1 and T2 relaxation times are not fully independent as all spin–lattice interactions that cause T1 recovery also contribute to T2 decay.29,30 Using those characteristics, the relaxometry has been used to assess changes in tissue properties within the brain and a variety of other tissues caused by disease and normal ageing processes.28–35 It is assumed that T1 and T2 relaxation values can help understand the changes in tissue properties in facial ageing.

The purpose of this study was to investigate location-specific, age-related changes in soft tissue properties of the face, such as muscular and fatty hypertrophy or atrophy, fatty infiltration and oedema, which could contribute to specific morphological changes in facial appearance, using quantitative MRI (qMRI) analysis of T1 and T2 values.

Methods and materials

Subjects

All subjects were enrolled prospectively and consented for the experimental qMRI sequence following the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guideline of the National Institutes of Health over a 3-year period (May 2005 through May 2008). The protocol for both volunteers and patients was approved by the internal review board of Boston Medical Center. The qMRI studies of 38 subjects (age range, 0.5–87 years; mean age, 31.2 years) were available for the analysis (Table 1). The gender composition of the subject population was 20 males (age range, 0.6–87 years; mean age, 33.3 years) and 18 females (age range, 0.5–78 years; mean age, 28.9 years). The subjects consisted of 4 healthy volunteers (4 males; age range, 28–47 years) and 34 patient volunteers who underwent MRI for various clinical reasons (Table 2), none of which were related to orbital or facial disorders. A review of the electronic medical records and imaging records for all included subjects demonstrated no history of orbital or facial pathology or risk factors predisposing to potential abnormalities, such as trauma, facial weakness, prior surgery or infection, nerve enhancement, cancer and systematic muscular diseases. Patients with pathological conditions known to contribute to changes in relaxometry, including sickle cell disease (14 subjects) and radiotherapy (1 subject) were excluded. Studies with severe motion or dental artefacts were also excluded (four subjects). In accordance with our institutional clinical protocol, MRIs acquired on children less than 7 years of age were performed with sedation.

Table 1.

Age distribution of the 38 subjects included in this study

| Age (years) | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| 10–19 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 20–29 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 30–39 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 40–49 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 50–59 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 60–69 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 70–79 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 80–89 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 20 | 18 | 38 |

Table 2.

Clinical indications for brain MRI in 34 patients

| Clinical indication | Number of patients | Clinical indication | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrocephaly | 2 | Seizure | 8 |

| Microcephaly | 1 | Syncope | 1 |

| Abnormal skull shape | 1 | Epilepsy | 3 |

| Developmental delay | 3 | Headache | 6 |

| Short stature | 1 | Dizziness | 1 |

| Low hormone level | 1 | Stroke | 3 |

| Attention deficit hyperactive syndrome | 1 | Memory loss/dementia | 2 |

Image acquisition

All subjects were scanned with the mixed turbo-spin echo (mixed-TSE) pulse sequence, using either of two 1.5 T MRI units (Intera and Achieva; Philips Medical Systems of North America, Cleveland, OH). The key imaging parameters of the mixed-TSE sequence are as follows: effective echo time, 7.142 and 100 ms; repetition time, 14,882 ms; inversion time, 700 and 7441 ms; echo train length, 18 (9 per echo: centric, liner), acquisition matrix, 256 × 192; field of view, 240 × 180 mm; 80 slices with no gap, reconstructed voxel size, 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 3.000 mm3 and scan time, 9 min. For all scans, the quadrature body and head coils were used for radiofrequency excitation and signal detection, respectively. Mixed-TSE is a fast multislice quadruple time point qMRI pulse sequence that combines the principles of T1-weighting by inversion recovery and of T2-weighting by dual-echo sampling in a single acquisition. The principles of mixed-TSE have been described previously in the literature.29,30 The acquired images were digital imaging and communication in medicine transferred and processed to generate qMRI maps portraying the T1 and T2 distributions simultaneously and with the native spatial resolution and anatomic coverage of the directly acquired mixed-TSE scan.

Image processing

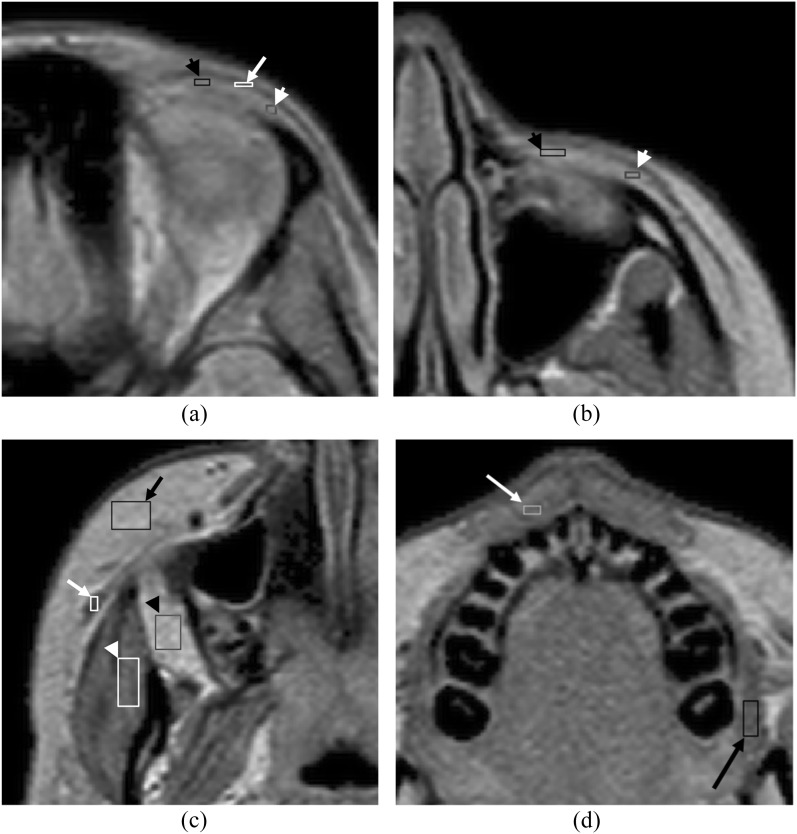

In this study, a spatial resolution enhancement technique was applied to the qMRI maps and each voxel (size, 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 3.000 mm3) was subdivided into smaller voxels (size, 0.31 × 0.31 × 3.00 mm3) to measure smaller structures. The spatial resolution enhancement technique enhances the spatial resolution of MR images based on the method of voxel sensitivity function deconvolution and cubic spline interpolation.36 After selecting a level with minimal motion artefacts, a rectangular voxel-based region of interest (ROI) was manually placed within each structure of maximal possible size without inclusion of adjacent structures. At the level of the upper end of the ocular globe, the ROIs were placed within the orbicularis oculi muscle, the medial and lateral portions of the eyelid fat (Figure 1a). At the level of the lower orbit, ROIs were placed within the medial and lateral portions of the eyelid fat (Figure 1b). At the level of the muscle belly of the zygomaticus major muscles, ROIs were placed within the masseter and zygomaticus major muscles, subcutaneous cheek fat and buccal fat (Figure 1c). At the upper lip level, ROIs were placed within the buccinator and orbicularis oris muscles (Figure 1d). Mean values and standard deviation of T1 and T2 measurements and the voxel count within the ROI were obtained in total of five facial musculatures and six facial fat regions bilaterally. The average voxel count of each structure ranged from 19 within the orbicularis oculi muscle to 302 within the buccal fat. To ensure anatomical consistency of ROI positioning, ROI placement was performed by two investigators and inspected for internal consistency by a single investigator (MW) with 14 years of experience in radiology and with familiarity specific to the placement of ROIs in these structures. Acquired measurements of the right and left paired structures as specified above were combined and plotted as functions against subject age.

Figure 1.

Axial images of the mixed turbo-spin echo sequence with spatial resolution enhancement technique in a 17-year-old female. (a) At the level of the upper end of the ocular bulb, the rectangular region of interests (ROIs) are placed within the orbicularis oculi muscle (white arrow), the medial (black arrow head) and lateral (white arrow head) portions of the eyelid fat of maximal possible size. (b) At the level of the lower orbit, ROIs are placed within the medial (black arrow head) and lateral (white arrow head) portions of the eyelid fat. (c) At the cheek level, ROIs are placed within the right zygomaticus major muscle (white arrow), right masseter muscle (white arrow head), the subcutaneous cheek fat (black arrow) and the buccal fat (black arrow head). (d) At the upper lip level, ROIs are placed within the left buccinator muscle (black arrow) and orbicularis oris muscle (white arrow).

Statistical analysis

We fitted multiple linear regression models for the dependent variables T1 and T2 while controlling for the sex of the subject. We checked for linear and quadratic associations with age and modifying effects of sex. Higher order independent variables (quadratic age effects and interaction variables) remained in the model if their p-value was ≤0.05. When there are interactions, the significance of the main effect [age (centred at 30), male] is not necessary if the higher order (age2 or age × male) is significant. The percentage of the variation in the T1 or T2 values that is explained by the variables in the model is represented by the adjusted R2 for each regression model. Adjusted R2 is the amount of variation in the T1 (or T2) outcome variable that is explained by the age and sex variables. Age in years, a continuous independent variable, was centred to allow better interpretation of quadratic effects. We checked model assumptions with residual plots. Our a priori hypotheses are that there are associations between age and our 22 T1 and T2 muscle and fat-dependent variables. We note p-values that are <0.05 but that are possible “false discoveries” using the method described in the literature.37 For this study, the association is a possible false discovery if the p-value is ≤0.05 but >0.041 using the false-discovery method.

Results

There was no significant left–right asymmetry for most of the structures, with the exception of T2 values within the masseter muscle, buccinator muscle, subcutaneous cheek fat and buccal fat (p = 0.02, 0.033, 0.0003 and 0.02, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in age between male and female subjects (p = 0.63).

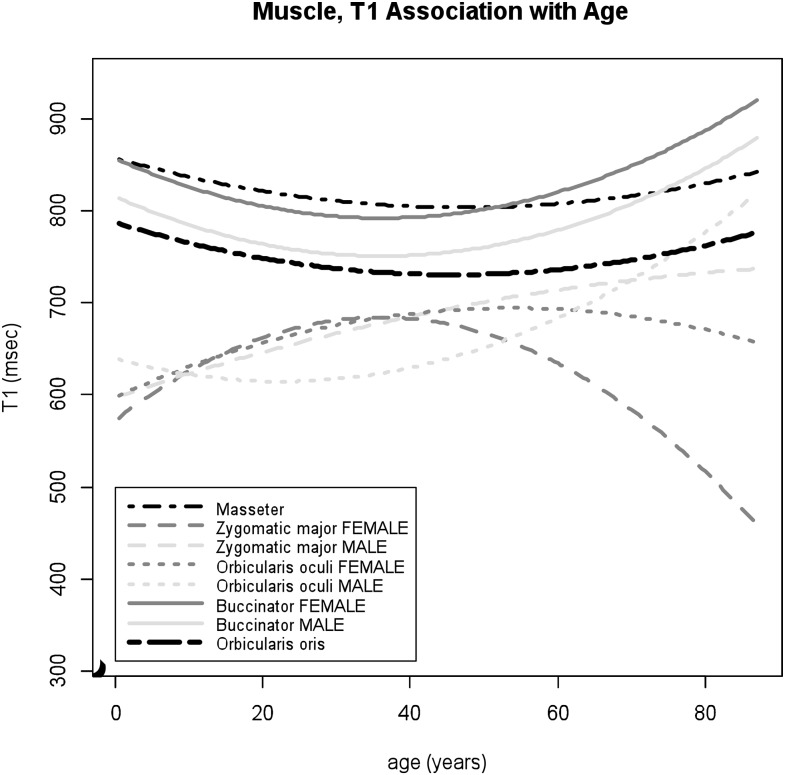

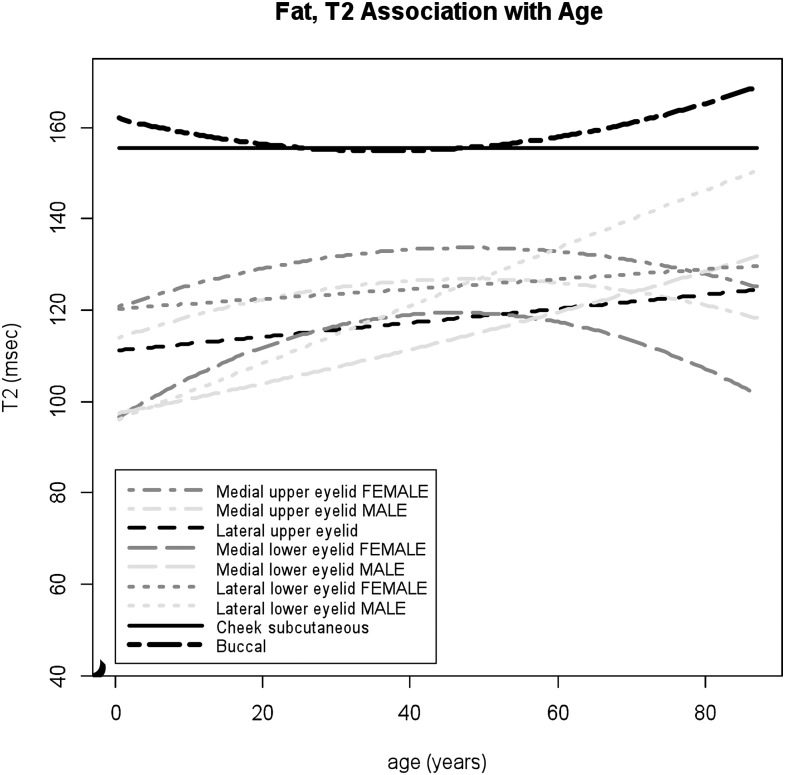

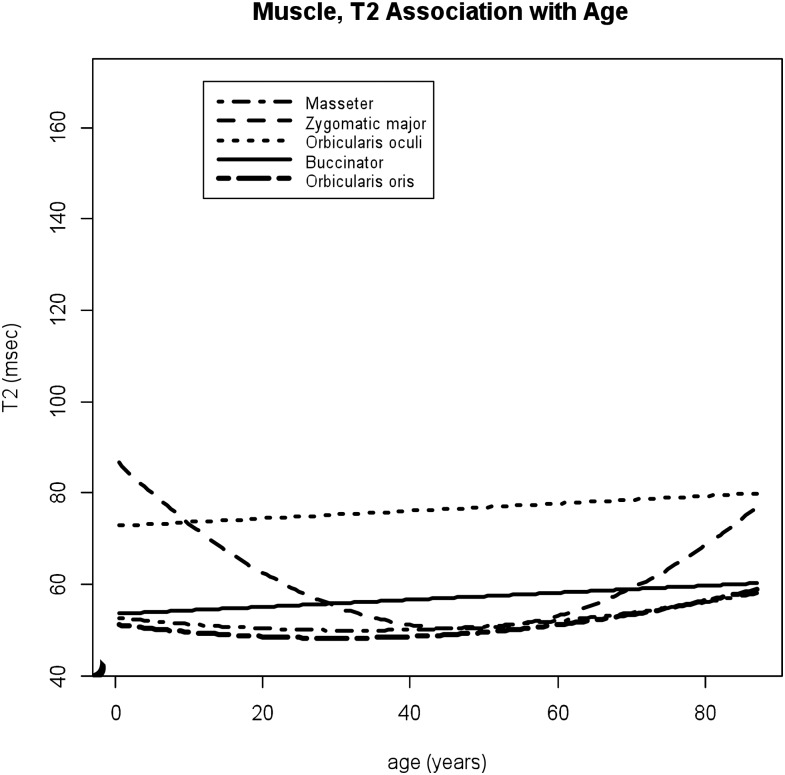

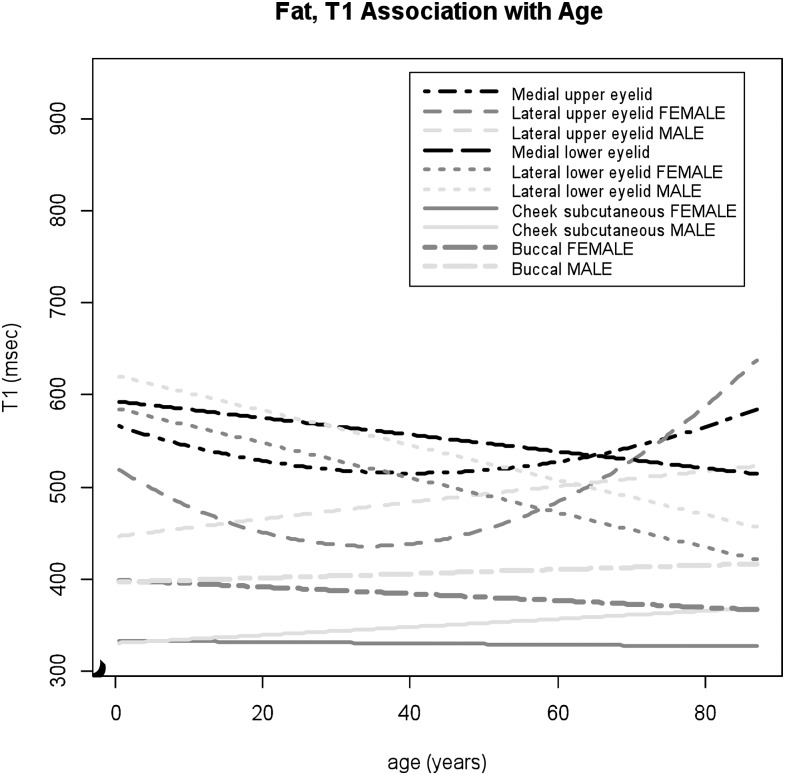

The regression model analysis of association of age and sex with T1 and T2 values within each structure is presented in Figures 2–5, in which the higher-order regression models with linear and quadratic terms were shown for each facial soft tissue. Significant age-related changes were observed in the T1 and T2 values within most of the facial musculatures and fat areas, with the exception of T2 values within the subcutaneous cheek fat.

Figure 2.

T1 values of the facial muscles associated with increasing patient age. The quadratic age-related changes are noted in T1 values particularly within the zygomaticus major muscle in female subjects, with prominent age-associated T1 decreases after middle age.

Figure 5.

T2 values of the facial fat associated with increasing patient ages. The greater age effects are shown in the lower eyelid fat, particularly in the lateral lower eyelid in the male group, compared to the upper eyelid fat. T2 values of the buccal fat and subcutaneous cheek fat are higher than those of the eyelid fat.

Facial musculatures

Among facial musculatures, large age-related changes were observed within the zygomaticus major muscle in T1 and T2 values. The data of both T1 and T2 values within the zygomaticus major muscle fit to the quadratic regressions with moderate to high adjusted R2 (p = 0.0002 and <0.0001 for age2, adjusted R2 = 36% and 47%, respectively). For T1 values within the zygomaticus major muscle, significant gender differences were observed (p = 0.01 for male × age2). Lower T1 and higher T2 values were noted during childhood for both male and female subjects (Figures 2 and 3). As age increases, T1 values decrease in the female group, while T1 values increase slightly in the male group. T2 values within this muscle showed age-associated increases in older ages (p < 0.0001 for age2). For the orbicularis oculi muscles, the sex-specific age dependencies were noted in T1 values (p = 0.01 for male × age2); inverted U-shaped trajectory for females and U-shaped trajectory for male subjects (Figure 2). T2 values within the orbicularis oculi muscle demonstrated slight but statistically significant increases with age with higher values compared to other facial muscles (p = 0.044 for age) (Figure 3). For the masseter and orbicularis oris muscles, T1 and T2 values remained relatively constant over multiple age ranges (Figures 2 and 3), while slight quadratic effects were seen (masseter p = 0.006 and 0.02 for age2, orbicularis oris p = 0.03 and 0.03 for age2, respectively). For the buccinator muscles, the data of T1 values fitted to the quadratic models with male and female separately (p = 0.0002 for age2 and p = 0.01 for male), showing age-related increases after middle ages (Figure 2), while T2 values showed small but statistically significant increases with age (p = 0.036 for age).

Figure 3.

T2 values of the facial muscles associated with increasing patient ages. T2 values of the zygomaticus major muscle demonstrates dynamic age-related changes with higher T2 values during childhood and age-associated T2 increases in older ages.

Facial fat

For the eyelid fat, location-specific relaxometric features were demonstrated. The data of T1 values within the medial and lateral aspects of the upper eyelid fitted to the quadratic regression model (p = 0.01 and 0.004 for age2, respectively) with stronger quadratic effects observed within the lateral upper eyelid in female subjects (p = 0.02 for male × age2) (Figure 4), whereas T1 values within the lower eyelid demonstrated negative correlations with age, with larger T1 decreases within the lateral lower eyelid (medial p = 0.0003 for age, lateral p < 0.0001 for age) (Figure 4). For T2 values within the lower eyelid fat, significant gender differences were observed (medial p = 0.046 for male × age2, lateral p < 0.0001 for male × age). A prominent positive correlation was noted within the lower eyelid in male subjects, with larger increases within the lateral than the medial aspect (Figure 5). For female subjects, T2 values within the medial lower eyelid showed inverted U-shaped trajectory and T2 values within the lateral lower eyelid slightly increased with age (Figure 5). The data of T1 and T2 values within the lateral lower eyelid fitted well to the model (adjusted R2 = 42% and 56%, respectively). Age-related changes in T2 values within the upper eyelid areas were statistically significant but relatively small throughout the lifespan (medial p = 0.04 for age and 0.03 for male, lateral p = 0.01 for age) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

T1 values of the facial fat associated with increasing patient ages. The lower eyelid fat shows significant age-associated decreases in T1 values, while U-shaped trajectory of T1 values within the upper eyelid is noted particularly obviously within the lateral upper eyelid in the female group. Both the buccal fat and subcutaneous cheek fat show lower T1 values compared to the eyelid fat.

The subcutaneous cheek and buccal fat showed relatively lower T1 and higher T2 values compared to those of eyelid regions (Figures 4 and 5). The data of T1 values within both the buccal fat and subcutaneous cheek fat fitted to the linear model with common gender-specific age dependency; slight decreases in T1 values with age in female group and slight increases in male group (subcutaneous cheek p = 0.004 for male × age, buccal p = 0.048 for male × age) (Figure 4). T2 values within the buccal fat showed small but statistically significant age effects as U-shaped trajectory (p = 0.01 for age2), whereas there were no age-related changes observed in T2 values within the subcutaneous cheek fat (Figure 5).

Discussion

This is a pilot study demonstrating the feasibility of using MRI to illustrate and quantify the non-uniform tissue-specific properties and ageing patterns affecting the facial soft tissues. Within the facial musculature, the relaxometry within the zygomaticus major muscle demonstrated non-uniform age-related changes that were modelled with quadratic regressions with moderate to high adjusted R2. The early qMRI changes during childhood may be suggestive of an increase in the musculature tissue, although the possibility of contamination with the adjacent adipose tissue cannot be excluded due to the small size of this structure. After middle ages, significant age-associated T2 increases within the zygomaticus major muscle were demonstrated with decreases in T1 values in female subjects. Those changes in relaxometry may be reflective of fatty atrophy. An increase in T2 values was also observed in other muscle groups within the body including the tibialis anterior, soleus and gastrocnemius muscles.38 The zygomaticus major muscle is primarily responsible for lifting and drawing the angle of the mouth laterally with smiling and is a part of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system, a continuous and organized fibrous network connecting muscles of the face with the dermis, which is a key structure for facial ageing. Loss of tension in those structures results in gravity-induced descent of the facial soft tissues. The age-related qMRI changes in the zygomaticus major muscle observed in this study may reflect these structural alternations and may relate to indirect modification of facial muscle contour as observed in the study by Le Louarn et al.1 Conversely, the masseter and orbicularis oris muscles demonstrated relatively constant qMRI measurements with high T1 and low T2 values from childhood through old age. This may possibly be related to the preserved and constant functional demands of these structures throughout life.

One of the most common morphologic changes associated with the characteristic appearance of an older face is the distinctive prominence of the lower eyelids.3,5 Prior histopathological study was unable to demonstrate age-related morphological changes in the orbicularis oculi muscles,39 whereas our study showed statistically significant age-related changes in this muscle. The age-related increases in T2 values, accompanied by increases in T1 values particularly in male subjects, are suggestive of increasing water content, which may be associated with unique properties of the orbit as previously described.26 Those qMRI characteristics would help in designing anti-ageing strategies specifically for eye regions.

Within the eyelids, the retro-orbicularis oculus fat and suborbicularis oculi fat consist primarily of fibrofatty tissue in contrast to a pure fatty nature of the intra-orbital fat.40 The results of this study support the concept of the fibrofatty composition of the eyelid with higher T1 and lower T2 values compared to the cheek subcutaneous and buccal fat. Considering those qMRI findings suggestive of fibrofatty nature, age-associated T1 decreases and T2 increases in the lower eyelid may be indicative of fatty changes or hypertrophy, with more prominent changes over time at the lateral side, particularly in the male group. These findings are further supported by a prior study describing more prominent sagging of the lower eyelid in males compared to females.3 In our study, age-related changes in T1 and T2 values were non-uniform within the eyelid regions. The increases in T1 values and decreases in T2 values observed after middle ages within the medial upper eyelid fat may relate to fibrous changes, while the increases in both T1 and T2 values seen within the lateral upper eyelid in the elderly population may suggest increased water content. In contrast, the buccal fat demonstrated relatively constant T1 and T2 measurements throughout the lifespan. These findings are compatible with the histological observation that the buccal fat consists of pure white fat with very few fibrous trabeculae and has a stable function as an intramuscular sliding structure.41 However, in this study, T1 values of the buccal fat were higher than those of the subcutaneous fat, which is histologically much more fibrous.41 Considering relatively high T2 values in both buccal and subcutaneous fat, one possible explanation would be the presence of less fluid in the superficial fat tissue.

The primary limitation of this work is that the qMRI results from the study herein were from a single institution and may be limited for extrapolation to a general application due to differences in scanner performance and sequence acquisition. Second, this is a cross-sectional study and may not represent the lifelong changes in qMRI parameters in each individual. Third, the measurements were obtained using the ROI method. Therefore, the selection bias has to be considered. In addition, our sample size is relatively small, which comprises 36 subjects with an age distribution skewed towards a younger population. Small sample size and unbalanced age distribution of subject population may not fully characterize age-related changes in qMRI parameters. However, the model checking methods did not find problems. The statistical analyses performed in this study included evaluations of multiple hypotheses for multiple structures. Therefore, we performed an analysis to correct for potential false discoveries that ultimately changed some of the results and the levels of statistical significance for three of the outcomes observed in this study (T1 values within the buccal fat, and T2 values within the orbicularis oculi muscle, and the medial lower eyelid fat). The study population may not completely exclude all of the possible causes that might affect relaxometry measurements, including systematic illness such as diabetes and strokes, and a history of a bruxing or clenching habit. Another limitation is that there are no histopathology specimens obtained from the subjects included in this study to corroborate the qMRI results of this study. Validation by the studies with larger sample size and with histopathological correlation would be anticipated. Finally, the use of ROIs with a slice thickness of 3 mm may be vulnerable to partial volume effects even when using a spatial resolution enhancement technique. The relatively long acquisition time, approximately 9 min, for mix-TSE sequence may make this sequence vulnerable to motion artefacts, resulting in exclusion of multiple subjects. The application of surface coils, higher magnetic fields and shorter acquisition times may improve spatial resolution and artefact-related problems. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of applying MRI to facial ageing assessment should be addressed. However, compared to CT, MRI has an advantage as a non-invasive assessment tool for healthy subjects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this proof of concept study demonstrated the utility of using qMRI parameters to assess age-related changes of the facial soft tissues, demonstrating tissue-specific qMRI measurements and non-uniform ageing patterns within different regions of the eyelid fat, facial fat and facial musculature. It is important to consider the non-uniform, age-related changes in the property of facial soft tissues in addition to the volume changes.

Contributor Information

M Watanabe, Email: memi.watanabe@bmc.org, memi.watanabe@gmail.com.

K Buch, Email: karen.buch@bmc.org.

A Fujita, Email: akifumi.fujita@bmc.org.

C L Christiansen, Email: cindylc@bu.edu.

H Jara, Email: hjara@bu.edu.

O Sakai, Email: osamu.sakai@bmc.org.

References

- 1.Le Louarn C, Buthiau D, Buis J. Structural aging: the facial recurve concept. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2007; 31: 213–18. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald R, Graivier MH, Kane M, Lorenc ZP, Vleggaar D, Werschler WP, et al. Update on facial aging. Aesthet Surg J 2010; 30 Suppl.: 11S–24S. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10378696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezure T, Yagi E, Kunizawa N, Hirao T, Amano S. Comparison of sagging at the cheek and lower eyelid between male and female faces. Skin Res Technol 2011; 17: 510–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezure T, Amano S. Influence of subcutaneous adipose tissue mass on dermal elasticity and sagging severity in lower cheek. Skin Res Technol 2010; 16: 332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2010.00438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagien S. The role of the orbicularis oculi muscle and the eyelid crease in optimizing results in aesthetic upper blepharoplasty: a new look at the surgical treatment of mild upper eyelid fissure and fold asymmetries. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 125: 653–66. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c87cc6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelson BC, Hartley W, Scott M, McNab A, Granzow JW. Age-related changes of the orbit and midcheek and the implications for facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2007; 31: 419–23. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0120-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn DM, Shaw RB. Overview of current thoughts on facial volume and aging. Facial Plast Surg 2010; 26: 350–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw RB, Jr, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, Yaremchuk MJ, Girotto JA, Kahn DM, et al. Aging of the facial skeleton: aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 127: 374–83. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f95b2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw RB, Jr, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, Kahn DM, Girotto JA, Langstein HN. Aging of the mandible and its aesthetic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 125: 332–42. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c2a685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaremchuk MJ, Kahn DM. Periorbital skeletal augmentation to improve blepharoplasty and midfacial results. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 124: 2151–60. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bcf5bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn DM, Shaw RB, Jr. Aging of the bony orbit: a three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Aesthet Surg J 2008; 28: 258–64. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw RB, Jr, Kahn DM. Aging of the midface bony elements: a three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 119: 675–81. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000246596.79795.a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narici MV, Maganaris CN, Reeves ND, Capodaglio P. Effect of aging on human muscle architecture. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003; 95: 2229–34. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00433.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood V, Nanda S. Patient satisfaction with hyaluronic acid fillers for improvement of the nasolabial folds in type IV & V skin. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2012; 11: 78–81. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0256-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White WM, Makin IRS, Barthe PG, Slayton MH, Gliklich RE. Selective creation of thermal injury zones in the superficial musculoaponeurotic system using intense ultrasound therapy: a new target for noninvasive facial rejuvenation. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2007; 9: 22–9. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.9.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh DH, Shin MK, Lee SJ, Rho JH, Lee MH, Kim NI, et al. Intense focused ultrasound tightening in Asian skin: clinical and pathologic results. Dermatol Surg 2011; 37: 1595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'souza R, Kini A, D'souza H, Shetty N, Shetty O. Enhancing facial aesthetics with muscle retraining exercises—a review. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: ZE09–11. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9792.4753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markiewicz MR, Bell RB. The use of 3D imaging tools in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2011; 19: 655–82. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honrado CP, Larrabee WF, Jr. Update in three-dimensional imaging in facial plastic surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 12: 327–31. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000130578.12441.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hester TR, Sullivan K. The role of the midface lift in perioral rejuvenation. Semin Plast Surg 2003; 17: 157–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezure T, Hosoi J, Amano S, Tsuchiya T. Sagging of the cheek is related to skin elasticity, fat mass and mimetic muscle function. Skin Res Technol 2009; 15: 299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2009.00364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odunze M, Rosenberg DS, Few JW. Periorbital aging and ethnic considerations: a focus on the lateral canthal complex. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121: 1002–8. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000299381.40232.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richard MJ, Morris C, Deen BF, Gray L, Woodward JA. Analysis of the anatomic changes of the aging facial skeleton using computer-assisted tomography. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25: 382–6. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b2f766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JM, Lee H, Park M, Lee TE, Lee YH, Baek S. The volumetric change of orbital fat with age in Asians. Ann Plast Surg 2011; 66: 192–5. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181e6d052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosain AK, Klein MH, Sudhakar PV, Prost RW. A volumetric analysis of soft-tissue changes in the aging midface using high-resolution MRI: implications for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 115: 1143–55. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000156333.57852.2F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darcy SJ, Miller TA, Goldberg RA, Villablanca JP, Demer JL, Rudkin GH. Magnetic resonance imaging characterization of orbital changes with age and associated contributions to lower eyelid prominence. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 122: 921–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181811ce8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YS, Tsai TH, Wu ML, Chang KC, Lin TW. Evaluation of age-related intraorbital fat herniation through computed tomography. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 122: 1191–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318185d370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelbrecht V, Rassek M, Preiss S, Wald C, Mödder U. Age-dependent changes in magnetization transfer contrast of white matter in the pediatric brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 1923–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki S, Sakai O, Jara H. Combined volumetric T1, T2, and secular-T2 quantitative MRI of the brain: age-related global changes (preliminary results). Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 24: 877–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito N, Sakai O, Ozonoff A, Jara H. Relaxo-volumetric multispectral quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the brain over the human lifespan: global and regional aging patterns. Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 27: 895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson GD, Connelly A, Duncan JS, Grünewald RA, Gadian DG. Detection of hippocampal pathology in intractable partial epilepsy: increased sensitivity with quantitative magnetic resonance T2 relaxometry. Neurology 1993; 43: 1793–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.9.1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito N, Sakai O, Bauer CM, Norbash AM, Jara H. Age-related relaxo-volumetric quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the major salivary glands. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2013; 37: 272–8. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31827b4729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao J, Saito N, Ozonoff A, Jara H, Steinberg M, Sakai O. Quantitative MRI analysis of salivary glands in sickle cell disease. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 630–6. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/31672000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buch K, Watanabe M, Elias EJ, Liao JH, Jara H, Nadgir RN, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging analysis of the lacrimal gland in sickle cell disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2014; 38: 674–80. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elias EJ, Liao JH, Jara H, Watanabe M, Nadgir RN, Sakai Y, et al. Quantitative MRI analysis of craniofacial bone marrow in patients with sickle cell disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 622–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker DL, Du YP, Davis WL. The voxel sensitivity function in Fourier transform imaging: applications to magnetic resonance angiography. Magn Reson Med 1995; 33: 156–62. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glickman ME, Rao SR, Schultz MR. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 850–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwenzer NF, Martirosian P, Machann J, Schraml C, Steidle G, Claussen CD, et al. Aging effects on human calf muscle properties assessed by MRI at 3 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 29: 1346–54. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H, Park M, Lee J, Lee ES, Baek S. Histopathologic findings of the orbicularis oculi in upper eyelid aging: total or minimal excision of orbicularis oculi in upper blepharoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2012; 14: 253–7. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2011.1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang K, Joong Kim D, Chung RS. Pretarsal fat compartment in the lower eyelid. Clin Anat 2001; 14: 179–83. doi: 10.1002/ca.1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahn JL, Wolfram-Gabel R, Bourjat P. Anatomy and imaging of the deep fat of the face. Clin Anat 2000; 13: 373–82. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]