Abstract

Giant cell tumour (GCT) of the spine is rarely encountered in daily clinical practice. Most of the tumours occur at the sacrum instead of at the spine above the sacrum, which has been reported to account for 1.3–9.3% of all spine GCTs. This article is a review of our radiological experience of the diagnosis of spine GCT above the sacrum based on 34 patients at a single institution. The purpose of this pictorial review is to highlight the imaging findings of GCT and to provide clues that may distinguish it from other, more common neoplasms.

Giant cell tumour (GCT) of the spine is rarely encountered in the daily clinical practice. Most of the tumours occur at the sacrum instead of at the spine above the sacrum, which has been reported to account for 1.3–9.3% of all spine GCTs.1 There are only a few published reports focusing on GCT of the spine above the sacrum in the literature.2,3 This article was a review of our radiological experience of the diagnosis of spine GCT above the sacrum based on 34 patients at a single institution. The purpose of this pictorial review is to highlight the imaging findings of GCT and to provide clues that may distinguish it from other, more common neoplasms.

CLINICAL INFORMATION

GCT of the spine above the sacrum frequently affects the thoracic and lumbar spine and rarely affects the cervical spine.2,3 Most tumours are limited to one vertebral segment, but may also involve the adjacent vertebrae (Figure 1). Spine GCTs frequently affect patients between 20 and 40 years of age and show a predominance in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 2 : 1.

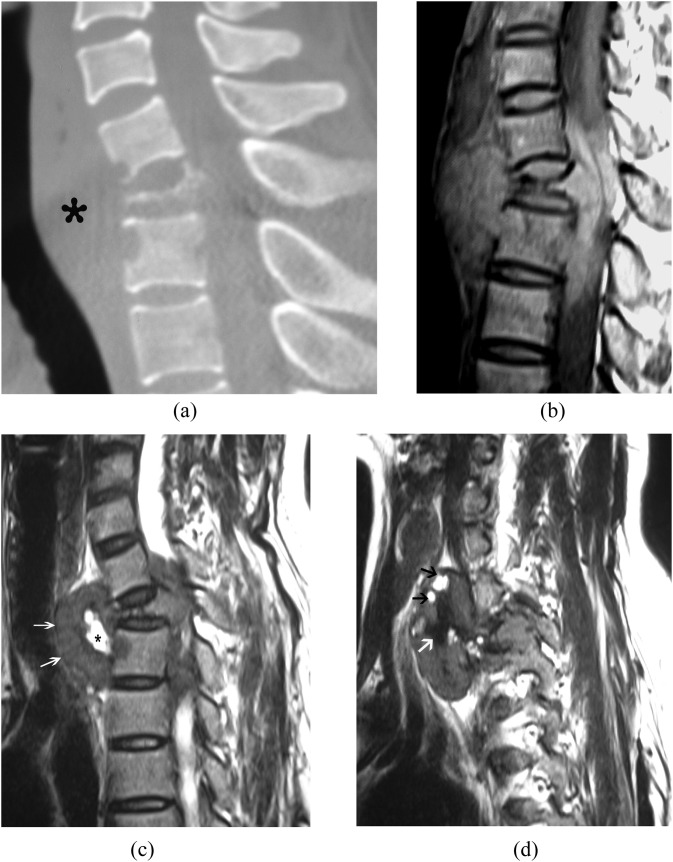

Figure 1.

(a–d) A 36-year-old female with giant cell tumour of C6–T1. (a) Sagittal reconstruction of CT image reveals that the lesion involves three vertebral segments and complete vertebra plana of C7 with an anterior soft-tissue mass (asterisk). (b) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI shows heterogeneous isosignal large mass in the anterior soft tissue and intraspinal canal that compresses the dura and spinal cord. (c) Sagittal T2 weighted MRI shows low signal intensity of the solid component of the tumour (arrows) and cystic areas (asterisk). The intervertebral disc appears to be intact. (d) Sagittal T2 weighted MRI in the lateral slice showing cystic areas (black arrows) and zonal low signal area (white arrow) caused by haemosiderin deposition.

TUMOUR LOCATION AND EXTENSION

Our series shows that 85% of tumours arose from the vertebral body and all extended to the vertebral arch (Figures 2–5); the other 15% of tumours arose from the posterior elements and all involved the vertebral body (Figure 6). The pedicle of the vertebral arch was involved in all cases. This location feature is valuable in the differential diagnosis of the spine GCT, as other spine tumours such as osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma and aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) of the spine frequently affect the posterior elements.4 If the lesions arise in the vertebral body, they can be distributed centrally or eccentrically (Figures 2–5). Lesions that are large at presentation more frequently appear central in location.

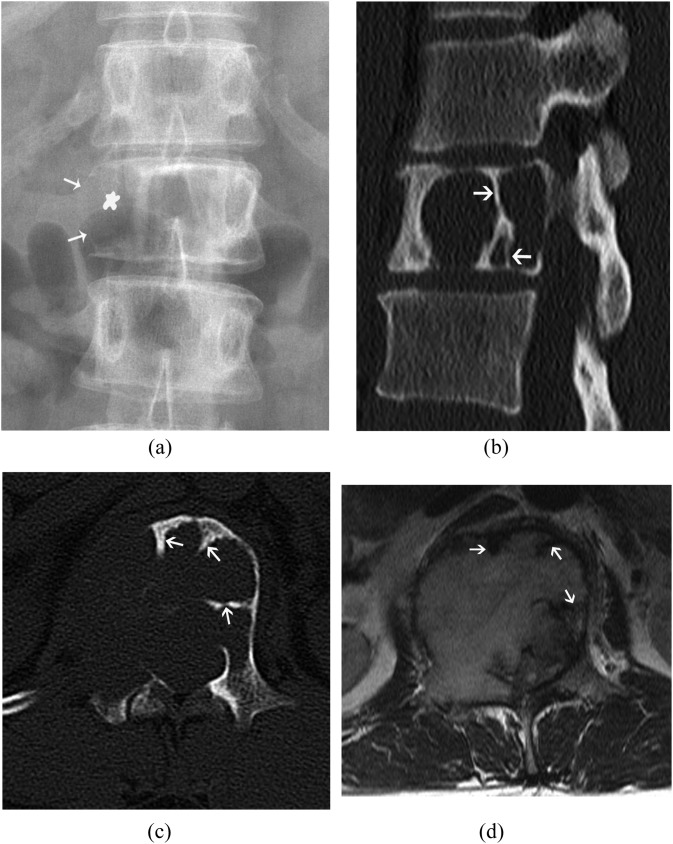

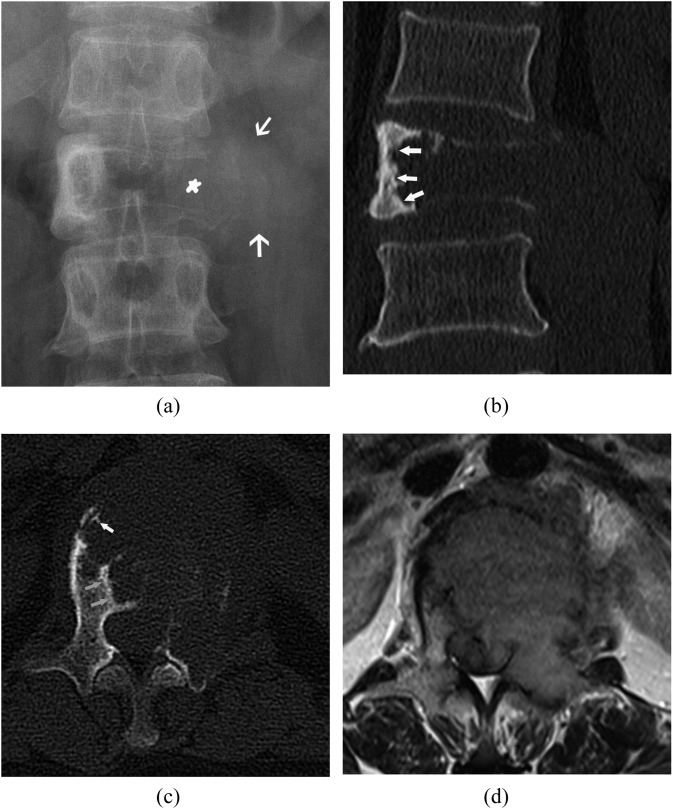

Figure 2.

(a–d) A 29-year-old female with giant cell tumour of L1. (a) Anteroposterior radiograph shows expansile osteolytic destruction of L1. The cortex in the right edge of the vertebral body (white arrows) and the oval structure of the right pedicle disappear (asterisk). (b) Sagittal reconstructed CT image shows the lesion displaying isomuscle density with long bony septa (white arrows). (c) Axial CT image shows that the lesion arises from the vertebral body with eccentric distribution and extends to the right pedicle and articular facet. Long bony septa from the border of the tumour extending to the inside of the tumour are seen opposite to the eccentric side (arrows). The cortex disappears in some lytic areas. (d) Axial T2 weighted MRI shows that the tumour extends to the paravertebral soft tissue and spinal canal, causing spinal cord and nerve root compression. Curvilinear low signal areas are also seen (arrows).

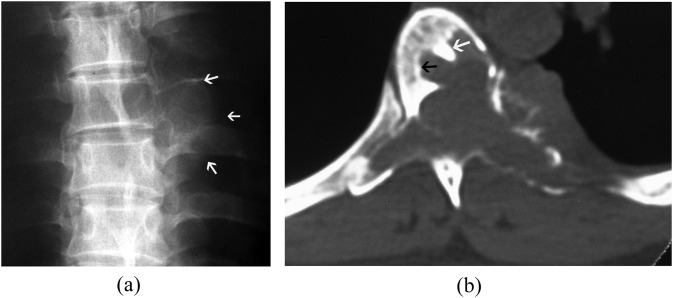

Figure 5.

(a, b): A 32-year-old female with giant cell tumour of L5. (a) Axial CT image shows a geographical lesion with isomuscle density. Bony septa (black arrows) are seen at the border of the tumour opposite to the eccentric side. Areas of disappearance of the cortex and associated soft-tissue mass are seen (white arrows). (b) Sagittal T1 weighted MRI displaying a band of low signal intensity (white arrow) around the margin of the tumour and linear low signal intensity (black arrow) within the tumour.

Figure 6.

(a, b) A 44-year-old female with giant cell tumour of T7. (a) Anteroposterior radiograph of the thoracic spine shows destruction of the posterior elements, the left pedicle disappears. A large soft-tissue mass (white arrows) is seen in the paravertebral line. (b) Axial CT image shows the tumour arising from the posterior elements with extension to the vertebral body. Bony septum (white arrow) and thin sclerotic border (black arrow) are also seen.

Although it is a benign tumour, spine GCT can be locally aggressive. It usually extends to the paravertebral soft tissue and spinal canal, causing spinal cord and/or nerve root compression (Figures 1–5).1,4 In our series, spinal canal extension (92%) was more frequent than paravertebral extension (68%). The tumours can also extend through the vertebral articulation, costovertebral articulation, intervertebral disc (Figure 7) and adjacent vertebral segment (Figure 1). This is different from the appendicular GCTs, which rarely cross the joint.4 Hence, spine GCT is more aggressive on imaging appearance than appendicular GCT. Although involvement of the intervertebral disc is possible (Figure 7), it is not a common finding. This appearance easily differentiates inflammatory lesions, which usually destruct the intervertebral disc in the early period.4

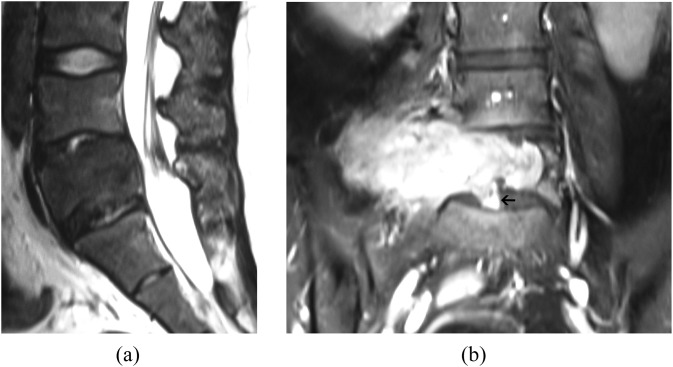

Figure 7.

(a, b) A 25-year-old female with giant cell tumour of L5. (a) Sagittal T2 weighted MRI shows an expansile low signal intensity lesion in L5. (b) Contrast-enhanced coronal T1 weighted MRI shows marked heterogeneous enhancement of the tumour. The adjacent intervertebral discs are partly involved (arrow).

RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF SPINE GIANT CELL TUMOURS

On radiographs, spine GCT often shows an expansile osteolytic lesion (Figures 2a and 3a). The lesion often produces collapse of the vertebral body, ranging from mild collapse (Figure 3a) to a complete vertebra plana (Figure 1). The cortex in the lytic areas appears blurred or lost with associated soft-tissue mass (Figures 2a and 3a). The oval-shaped pedicle of the vertebral arch appears deformed or disappears by destruction (Figures 2a, 3a and 6a). The soft-tissue masses usually appear in the paravertebral line of the thoracic spine (Figure 6a), the major psoas muscle of the lumbar spine (Figures 2a and 3a) and the anterior vertebral soft tissue of the cervical spine (Figure 1a).

Figure 3.

(a–d) A 43-year-old female with giant cell tumour of L1. (a) Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine shows an expansile osteolytic lesion with large soft tissue mass (white arrows). The oval structure of the left pedicle disappears (asterisk). (b) Coronal reconstructed CT image showing the sclerotic rim appears at the border of the tumour opposite to the eccentric side (white arrows). (c) Axial CT image shows the short bony septa (white arrow) and sclerotic rim (grey arrows) opposite to the eccentric side. (d) Axial T2 weighted MRI displays a low signal intensity lesion that extends to the paravertebral soft tissue and spinal canal, causing spinal cord and nerve root compression.

CT APPEARANCE OF SPINE GIANT CELL TUMOURS

On CT scans, the tumour has soft-tissue attenuation with no evidence of mineralized matrix (Figures 2, 3, 5 and 6).4 Areas of haemorrhage or necrosis may create a heterogeneous density with foci of low attenuation.4 The cortex at the lytic areas becomes thin or gets penetrated, or disappears with an associated soft-tissue mass (Figures 2c, 3c and 5a). A sclerotic margin at the periphery of the tumour is not uncommon,5,6 and was seen in 33% of the 30 cases that had CT scans in our series. If the lesion distributes eccentrically, such as biased to the left, the thin sclerotic rim usually appears at the right border of the tumour, opposite to the eccentric side (Figures 3b, 3c, 5a and 6b). Then, on one side of the tumour, there is an expansile remodelling and breakthrough of the cortex, while on the other side, there is a sclerotic border (Figures 3b and 5a). This paradoxical appearance is helpful in diagnosing GCT. Some special bony septa can be seen arising from the border of the lesion extending to the inside of the mass, which are demonstrated best in the axial image. These bony septa may give a radiographic “soap bubble” appearance.3 In our series, 70% cases showed this appearance, especially at the border of the tumour opposite to the eccentric side. Short bony septa appear as serrations and longer septa appear as spurs (Figures 2c, 3c and 5a). This appearance may be caused by the thickened remaining trabecular bone, a compensatory response to the weakened bone by the lytic process. If the lesion progresses, the remaining septa will also be gradually destroyed. We think that this appearance is characteristic of spine GCTs, although it can also be seen in plasmacytoma and haemangioma.7,8

MRI APPEARANCE OF SPINE GIANT CELL TUMOURS

Spine GCTs often show as heterogeneous signal intensity on all MR sequences. Generally, the solid components of GCT demonstrate low-to-intermediate signal intensity on T2 weighted MR images in 63–96% cases (Figures 1c and 7a) owing to high collagen content as well as haemosiderin deposition.9,10 Although this feature is not unique to GCT of the spine, it is very helpful in differential diagnosis because most of the other spinal neoplasms, such as metastases, lymphoma and chordoma usually demonstrate hyperintense signal on T2 weighted MR images.9 Haemosiderin deposition usually shows nodular, zonal, whorled or diffuse low signal intensity on all sequence images (Figure 1d),10 and the areas of low signal intensity are exaggerated on T2 weighted images and more on gradient-recalled echo images for their sensitive of haemosiderin.10 This phenomenon could support a diagnosis of GCT.10

Curvilinear low signal areas on both T1 and T2 weighted images are a common MRI feature of spine GCT (Figures 2d and 5b). This was observed in nine of the ten GCTs studied by Kwon et al9 and 69% of the tumours in our series. This appearance might correspond to a multiloculated lesion with thickened trabeculae, fibrous septa or haemosiderin deposit.9 Focal cystic areas with low signal intensity on T1 weighted MR images and with high signal on T2 weighted MR images without internal enhancement are frequent (Figures 1 and 4). These were found in 55% of tumours in our series.

Figure 4.

(a, b) A 25-year-old female with giant cell tumour of L2. (a) Axial T2 and (b) sagittal T2 weighted MR images show the lesion displaying heterogeneous signal intensity with multiple cystic areas and fluid–fluid levels (arrows). The lesion extends to the paravertebral soft tissue and spinal canal, causing spinal cord and nerve root compression.

Evidence of haemorrhage may also be apparent with high signal intensity on T1 and T2 weighted images or fluid–fluid levels on MR images (Figure 4), which were seen in 34% and 24% of our cases, respectively. These appearances are not specific, and they are more common in ABC.

Sometimes, a band of low signal intensity around the margin of the tumour can be seen (Figure 5b). This appearance corresponds to the thin sclerotic border of the tumour or fibrous capsule.3

The tumours frequently show marked enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT and MR images because of the hypervascular nature of the tumour (Figure 7b).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

GCT is the most common lesion associated with secondary ABC. It should be differentiated from primary ABC. ABC of the spine usually affects the posterior elements, and patients are typically young below the age of 20 years, and the tumour demonstrates as a purely cystic appearance on MR images.1,3 Although spine GCT usually affects the vertebral body and patients are typically between 20 and 40 years of age. There are solid components in the tumour except for the cystic areas, and these areas are usually at the centre of the lesion (Figure 1).

Plasmacytomas often have bony septa on CT scans and linear low signal intensity on MR images also.7 Plasmacytomas are more common in patients over 40 years of age, and cystic change is unusual in plasmacytoma,7 which is common in GCT.

Symptomatic haemangiomas are more likely to show irregular vertical trabeculae; nevertheless, marked pathological compression of vertebral bodies is infrequent in haemangioma. Marked hyperintensity on T2 weighted images and identification of an intact cortex adjacent to a paraspinal or epidural mass is helpful in diagnosing symptomatic haemangioma.8

In conclusion, GCT almost always affects the vertebral body and pedicle, with female predominance in patients between 20 and 40 years of age. It is an expansile, aggressive osteolytic lesion usually with heterogeneous low-to-intermediate signal intensity on the T2 weighted MR images. Bony septa within the tumour on CT scans and linear low signal areas on MR images are characteristic features. Cystic changes, sclerotic border and haemosiderin deposition can support the diagnosis. Although it may be difficult to make a correct pre-operative diagnosis, the interpreting radiologist must be aware of the typical imaging features of GCT to provide a complete and accurate differential diagnosis.

Contributor Information

L S Shi, Email: shilish@126.com.

Y Q Li, Email: liyuqing121@126.com.

W J Wu, Email: wenjwu@163.com.

Z K Zhang, Email: zhangzkjia@163.com.

F Gao, Email: alan846829@163.com.

M Latif, Email: 1096296634@qq.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanjay BK, Sim FH, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Klassen RA. Giant-cell tumours of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75: 148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boriani S, Bandiera S, Casadei R, Boriani L, Donthineni R, Gasbarrini A, et al. Giant cell tumor of the mobile spine: a review of 49 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012; 37: E37–45. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182233ccd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Si MJ, Wang CG, Wang CS, Du LJ, Ding XY, Zhang WB, et al. Giant cell tumours of the mobile spine: characteristic imaging features and differential diagnosis. Radiol Med 2014; 119: 681–93. doi: 10.1007/s11547-013-0352-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphey MD, Andrews CL, Flemming DJ, Temple HT, Smith WS, Smirniotopoulos JG. From the archives of the AFIP. Primary tumors of the spine: radiologic pathologic correlation. Radiographics 1996; 16: 1131–58. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.16.5.8888395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junming M, Cheng Y, Dong C, Jianru X, Xinghai Y, Quan H, et al. Giant cell tumor of the cervical spine: a series of 22 cases and outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008; 33: 280–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318162454f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphey MD, Nomikos GC, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH, Temple HT, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of AFIP. Imaging of giant cell tumor and giant cell reparative granuloma of bone: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2001; 21: 1283–309. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.5.g01se251283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Major NM, Helms CA, Richardson WJ. The “mini brain”: plasmacytoma in a vertebral body on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000; 175: 261–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DP. Symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: MR findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167: 359–64. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.2.8686604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon JW, Chung HW, Cho EY, Hong SH, Choi SH, Yoon YC, et al. MRI findings of giant cell tumors of the spine. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: 246–50. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki J, Tanikawa H, Ishii K, Seo GS, Karakida O, Sone S, et al. MR findings indicative of hemosiderin in giant-cell tumor of bone: frequency, cause, and diagnostic significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 166: 145–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]