Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cerebrospinal fluid is in contact with brain parenchyma and ventricles, and its composition might influence the cellular physiology of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) thereby contributing to disease pathogenesis.

OBJECTIVE

To identify the transcriptional changes that distinguish the transcriptional response induced in proliferating rat OPCs upon exposure to CSF from PPMS or RRMS patients and other neurological controls.

METHODS

We performed gene microarray analysis of OPCs exposed to CSF from neurological controls, or definitive RRMS or PPMS disease course. Results were confirmed by qRT-PCR, immunocytochemistry and western blot of cultured cells and validated in human brain specimens.

RESULTS

We identified common and unique genes for each treatment group. Exposure to CSF from PPMS uniquely induced branching of cultured progenitors and related transcriptional changes, including up-regulation (p < 0.05) of the adhesion molecule GALECTIN-3/Lgals3, which was also detected at the protein level in brain specimens from PPMS patients. However it also resulted in discordant patterns of gene expression when compared with the transcriptional program of oligodendrocyte differentiation during development.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite evidence of morphological differentiation induced by exposure to CSF of PPMS patients, the overall transcriptional response elicited in cultured OPCs was consistent with the activation of an aberrant transcriptional program.

Keywords: cerebrospinal fluid, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, gene expression, differentiation

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory autoimmune disease of the central nervous system, characterized by demyelination, axonal damage and remyelination1, 2. Strategies to repair central nervous system myelin during the disease course of MS have gained significant momentum and many studies focused on mechanisms responsible for impaired remyelination3, 4. In addition to intrinsic factors, progenitors are exposed to disease-specific changes in the environmental milieu possibly affecting their differentiation and the ability to repair damaged myelin. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is in contact with the brain parenchyma5, 6 and might influence the cellular physiology of OPCs. Extensive studies have been performed in order to identify soluble factors that mediate nervous system damage and inhibit repair in distinct types of multiple sclerosis, including proteomics7–9, metabolomics10, 11, RNA expression in peripheral blood12, and microRNAs13–15. Numerous studies have attempted to identify soluble factors in the CSF of MS patients that could account for the observed cellular effects. For example, we recently showed that ceramides present in MS CSF promote axonal injury and neuronal damage through oxidative stress mechanisms and mitochondrial bioenergetic failure16. In addition, microarray profiling of MS cortical gray matter revealed gene changes in oxidative stress, and remyelination/repair17. This study was designed to define the transcriptional changes occurring in proliferating OPCs, after exposure to the CSF of patients with distinct disease course. We found that proliferating OPCs exposed to CSF from PPMS patients up-regulate the expression of molecules implicated in OPC morphological differentiation, while down-regulating genes, which are highly expressed during developmental myelination. We conclude that the CSF from PPMS patients induces an aberrant transcriptional response in rat OPCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject material

Cerebral spinal fluid was collected by lumbar puncture from MS patients. We selected patients with definitive MS from our database according the 2010 McDonald criteria. For our study we selected two clinical forms of MS: a set of PPMS patients, defined by a progressive onset for more than one year of neurological dysfunction with magnetic resonance Swanton criteria of dissemination in space (McDonald criteria) and in which IgG oligoclonal bands were present in both the serum and the CSF, with more bands presents only in the CSF, an OCB pattern that have been recognized as more specific of PPMS. And a RRMS patient cohort defined by two or more relapses separated by one month; Swanton criteria for dissemination in time and space, and also the OCB of the IgG type should be present in the CSF16, 17. The control cohort consisted of patients with other neurological disorders including parainfectious myelitis, Miller-Fisher syndrome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The spinal fluid was immediately placed on ice, aliquoted and snap frozen on dry ice. Post-mortem human brain samples from frontal lobe region were obtained from the UK Multiple Sclerosis Tissue Bank and at UCLA.

Oligodendrocyte cultures

Oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPCs) were isolated from the cortex of postnatal day 1 rats and cultured according to published procedure18., as we have previously described (REFS). OPCs were grown in oligodendrocyte chemically-defined media (ODM) (REF). Cells were allowed to proliferate for 48 h in chemically-defined media supplemented with growth factors (GFs) (20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and 10 ng/mL platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGF-AA)) prior to treatment.

CSF treatment, RNA extraction and qPCR

OPCs were treated with a 1:1 dilution of CSF in ODM with GFs for 24 h and RNA was extracted following the Qiagen RNeasy kit manufacturer’s instructions and concentrations were determined using NanoDrop and quality verified by using 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent). For RNA extraction from human brain, normal appearing white matter was dissected from surrounding tissue and RNA isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and subsequent purification with RNeasy columns (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA, using Quanta Biosciences qScript™ cDNA SuperMix kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions and amplified using gene-specific primers (Table 1), and normalization to Gapdh (rat) or GAPDH, DHX32 and RPLP0 (human).

Table 1.

qPCR primers

| Gene Name | Accession | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bcan | NM_001033665.1 | gagcactcactctcccaggt | tgatgcacccagctgtagaa | Rat |

| Bcat1 | NM_017253.2 | ccgtgaggaccactctgc | atgagctgaagaacgcattg | Rat |

| Fau | NM_001012739.1 | ccgaagatcaagtcgtgctt | ggccagctacctccagagt | Rat |

| Gapdh | NM_017008.4 | agacagccgcatcttcttgt | cttgccgtgggtagagtcat | Rat |

| Gfap | NM_017009.2 | tcaagaggaacatcgtggtaaagac | tgctcctgcttcgactcctta | Rat |

| Lgals3 | NM_031832.1 | gtgaagcccaacgcaaac | tcattgaagcgggggtta | Rat |

| Lingo1 | NM_001100722.1 | aaaaccgcatcaagacactcaac | acagcgctcacaatgttctcat | Rat |

| Mag | NM_017190.4 | tcaacagtccctaccccaag | gagaagcagggtgcagtttc | Rat |

| Mog | NM_022668.2 | gagggacagaagaacccaca | cagttctcgacccttgcttc | Rat |

| Pcyt1a | NM_078622.2 | ggtacctggccctaatggag | ctggctgccgtaaaccaa | Rat |

| Pdgfra | NM_012802.1 | accatttctgttcacgagaaagg | gcaggttcacagtttccagatg | Rat |

| Pik3r3 | NM_022213.1 | agctgcgtaagatccgagac | tctgtgtcctcactcttgatcc | Rat |

| Pla2g7 | NM_001009353.1 | cataaagactttgatcagtgggact | cgggatgaggttctcgttc | Rat |

| Ppt1 | NM_022502.2 | ggacatctggacccacctt | gctcatggggttacagcag | Rat |

| Rasa1 | NM_013135.1 | catctaataaacgccttcgtca | tggtagtttatgagcttcttcaatatg | Rat |

| Rnf26 | NM_001113748.1 | cctgcctctagggctgtctt | ggaccaaaaactcccaacaa | Rat |

| Stk10 | NM_019206.2 | gtggatgccatcatgctaga | gcggtggatgattctcttg | Rat |

| Stk38 | NM_001015025.1 | tcagaatatgaattctaaaaggaaagc | gggtgcccactgtagagaag | Rat |

| Tbk1 | NM_001106786.1 | cctcggaggaacaaagaagtaa | tccagatattgcaccagaagg | Rat |

| DHX32 | NM_018180.2 | gccactgtgacttcatgaacag | gatttccatcattatccagtgc | Human |

| GAPDH | NM_002046 | acccactcctccacctttga | cataccaggaaatgagcttgacaa | Human |

| LGALS3 | AB006780.1 | cttctggacagccaagtgc | aaaggcaggttataaggcacaa | Human |

| RPLP0 | NM_001002.3 | gcgacctggaagtccaac | gtctgctcccacaatgaaac | Human |

MTT assay

The MTT assay was performed as previously described19. After 24 h of treatment, 5 mg/mL MTT was added to the cell media to a final concentration of 0.05 mg/mL and allowed to incubate for 4 h to allow MTT reduction. The formazan precipitate formed by viable cells was solubilized in DMSO, and read spectrophotometrically at 540 nm with background subtraction at 655 nm.

Gene microarray, data normalization and gene validation

The labeled cRNA was hybridized to Agilent SurePrint G3 Rat GE8×60K Microarray (GEO-GPL13521, in situ oligonucleotide) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the mRNA was reverse transcribed in the presence of T7-oligo-dT primer, labeled and scanned on an Agilent G2565CA microarray scanner. Data were extracted using the Feature Extraction Software (Agilent). Statistical analysis was conducted after background noise correction using NormExp method20. Differential expression analysis was carried out on non-control probes with an empirical Bayes approach on linear models (Smyth G.K., 2004). Results were corrected for multiple testing hypothesis using false discovery rate (FDR), and all statistical analyses were performed with the Bioconductor project (http://www.bioconductor.org/) in the R statistical environment (http://cran.r-project.org/)21. To filter out low expressed features, the 30% quantile of the whole array was calculated, and probe sets falling below threshold were filtered out. After merging the probes corresponding to the same gene on the microarray, the statistical significance of difference in gene expression were assessed using a standard one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis (cutoff p<0.01 and FDR <0.1). All data processing and analysis including PCA plot was carried out using R functions.

Immunostaining

Immunocytochemistry (IHC) of OPCs was performed as previously described22. Briefly, cells were fixed and incubated overnight in anti-GALECTIN-3 antibody (1:100 Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-20157) diluted in blocking solution (10% goat serum in PGBA) followed by detection using fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. For histological analysis frozen blocks of human brain were sectioned and slides were post-fixed in ice-cold methanol, quenched by incubation in H2O2 followed by antigen retrieval in citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) and incubation with mouse anti-GALECTIN-3 primary antibody (1:50, ab2787, Abcam) followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies (Mount Sinai Shared Resource Facility).

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described18. Briefly, proliferating oligodendrocyte progenitors were plated in 6-well poly-D-lysine coated plates, and treated with 1 mL of a 1:1 mixture of CSF: SFM + GFs for 24 h. Cells were harvested in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Ten micrograms of protein lysates were electrophoresed and blots were probed with antibodies for GALECTIN-3 (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-20157) and actin (1:1000, clone AC-40, Sigma). Blots were visualized using the Enhanced ECL detection system (Amersham). Quantification was performed using ImageJ.

Data Analysis and Overlap

Uniquely up-regulated or down-regulated genes in OPC by exposure to PPMS CSF were compared with a known oligodendrocyte specific transcriptome database (Zhang et al., 2014). We overlaid the uniquely up- or down-regulated genes in PPMS vs Control with the entire RNA-seq database in “oligodendrocyte precursor cell”, “newly formed oligodendrocyte” and “myelinating oligodendrocytes”.

RESULTS

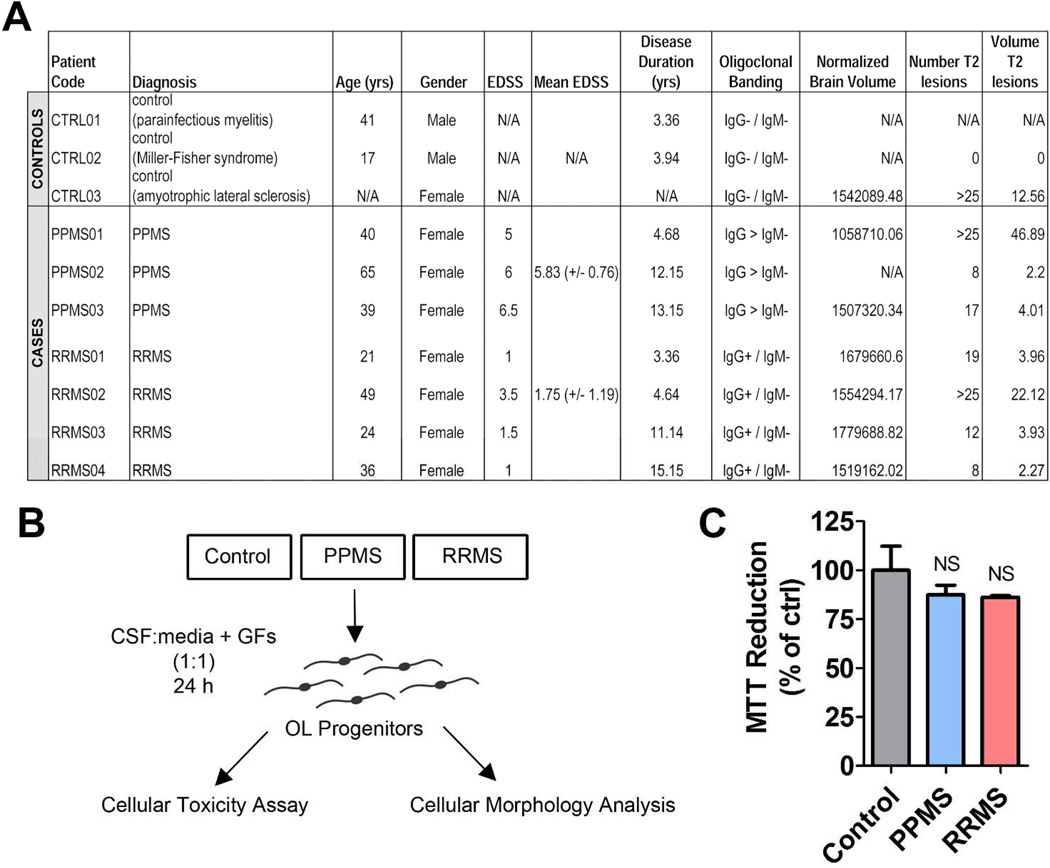

Since progenitor cells in the human brain have the ability to come to close contact with the CSF, we hypothesized that understanding how exposure to human CSF from RRMS or PPMS patients might affect gene expression, may uncover disease subtype specific transcriptional difference in oligodendrocyte lineage cells and inform us of potential differences in pathobiology. The purpose of our study was to determine the effect of exposure to CSF from patients with either primary progressive, or relapsing remitting MS on the transcriptional signatures of cultured OPCs. CSF samples from neurological patients (including an ALS patient with numerous T2-weighted lesions corresponding to concurrent ischemic strokes) were used as controls (Figure 1A). Of note is that controls and PPMS patients were characterized by similar disability.

Figure 1. Multiple sclerosis and control patient cohorts and experimental plan.

(A) Table describing patient cohort including the neurological controls and PPMS and RRMS patients. (B) Schematic diagram of treatment protocol for rat OPCs exposed to CSF. (C) MTT assay reduction of rat OPCs exposed to different patient group CSFs for 24 h. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction (NS = p > 0.05).

Proliferating rat OPCs were exposed for 24 h to CSF diluted 1:1 in chemically-defined media (Figure 1B) and the effect on viability (Figure 1C), morphology (Figure 2) and transcripts (Figure 2–3) changes were evaluated. We first performed an MTT cellular toxicity assay to determine whether CSF-exposed OPCs were viable (Figure 1C) and no difference was detected amongst the CSF groups tested (p > 0.05).

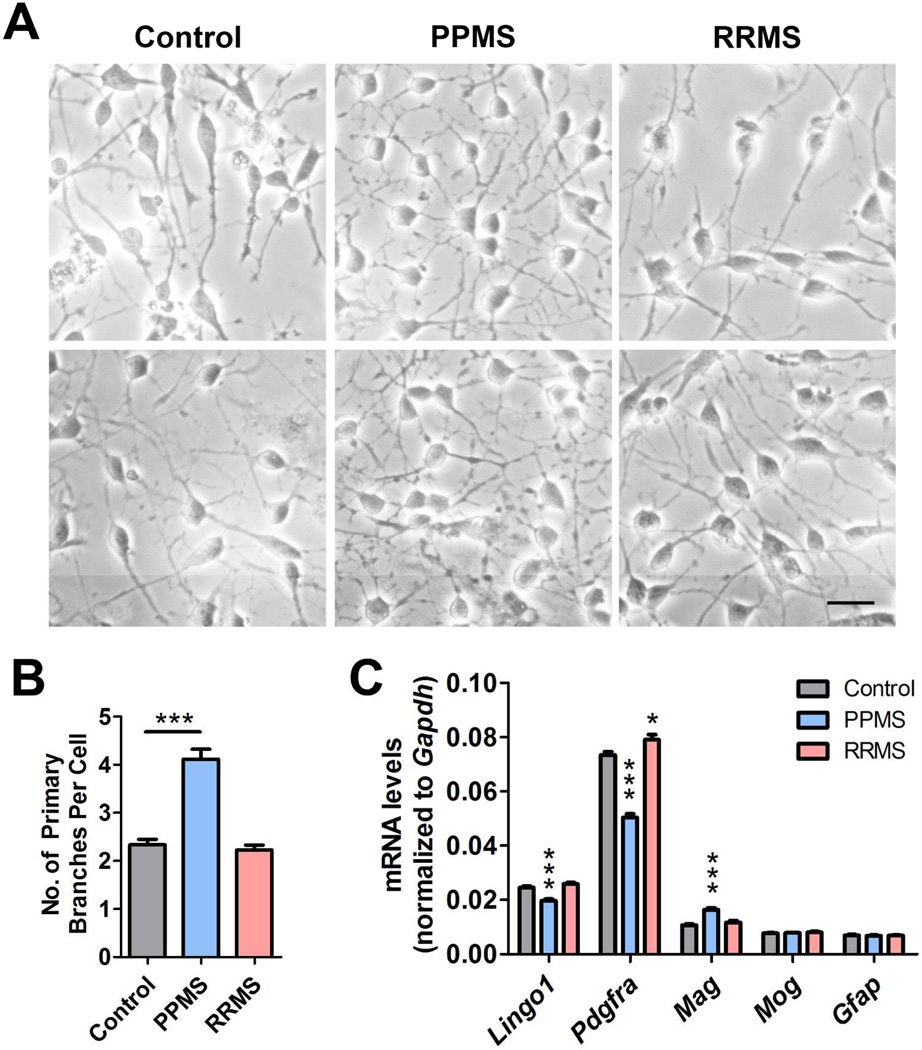

Figure 2. Cerebrospinal fluid from patients with a PPMS disease course promotes changes in OPC which are consistent with differentiation.

(A) Phase contrast micrographs showing the morphology of OPCs exposed to CSF for 24 h. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Quantification of primary processes in OPCs exposed to CSF from neurological controls, PPMS or RRMS patients. (C) qPCR analysis of differentiation markers in OPCs treated with CSF from different patient groups. Statistical differences in (B), and (C) were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 vs. control).

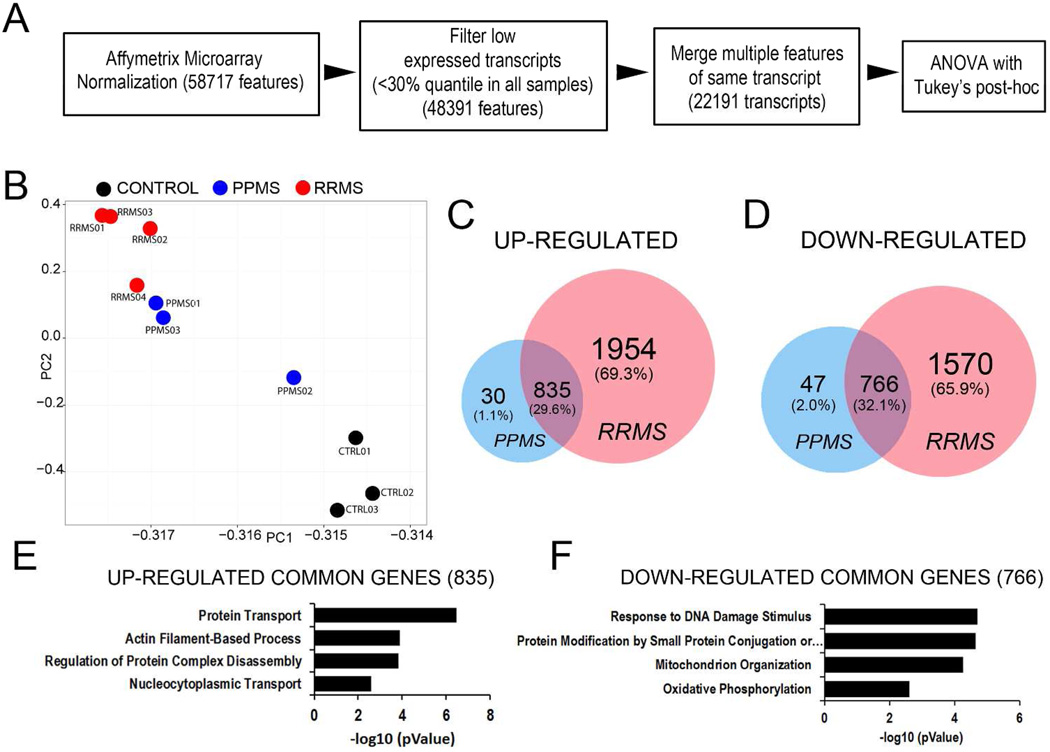

Figure 3. Exposure of rat OPC to human CSF form patients with distinct disease course results in distinctive transcriptional responses.

(A) Flowchart of the microarray analysis performed in OPCs incubated with CSF from patients with PPMS, RRMS or neurological controls for 24 h. (B) Principal component analysis of samples revealed a tight clustering of the samples within each treatment group. (C) Venn diagrams depicting uniquely and commonly up-regulated genes amongst PPMS and RRMS groups compared to control group. (D) Venn diagrams depicting uniquely and commonly down-regulated genes amongst PPMS and RRMS groups compared to control group. (E) Gene ontology analysis of up-regulated genes shared between PPMS and RRMS. (F) Gene ontology analysis of down-regulated genes shared between PPMS and RRMS.

Patient-derived CSF induces unique morphological and transcriptional changes in proliferating OPCs

A striking observation was the detection of a more highly branched phenotype only in OPC exposed to the CSF from PPMS patients (Fig. 2A). Quantification of the number of primary branches revealed a statistically significant (p < 0.001) increase only in cells treated with the CSF from PPMS patients, but not from RRMS or other neurological controls (Fig. 2B). These morphological changes were also associated with an overall pattern suggestive of a pro-differentiative effect of PPMS CSF, including down-regulation of transcript levels for Lingo1 and Pdgfra and concomitant upregulation of the myelin gene Mag (Fig. 2C). Together these changes were suggestive of a pro-differentiative effect of the CSF form PPMS patients on OPCs.

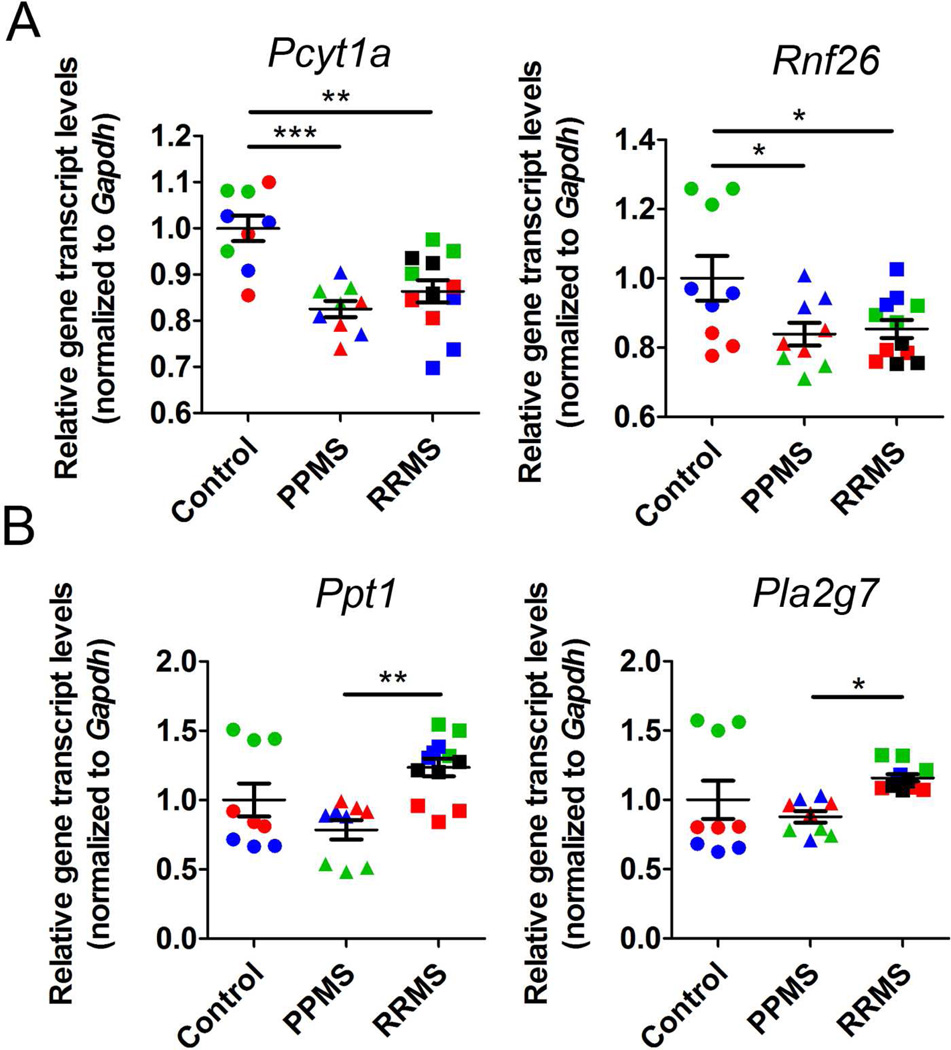

We next performed an Agilent microarray analysis to determine whether the changes that occurred in proliferating OPCs in response to patient CSF were consistent with a global reorganization of the transcriptional signature of oligodendrocyte differentiation. We performed gene expression value normalizations, and filtered out low expressed transcripts, followed by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Figure 3A) in order to determine genes that were significantly changed compared to control samples. A principal component analysis revealed the transcripts in treated OPC clustered according to patient diagnosis, with the CSF from RRMS patients inducing the most dramatic changes (Figure 3B). The overlap of genes that were up-regulated in OPC after treatment for 24 hours with the CSF form PPMS or RRMS (Figure 3C), revealed 29.6% of genes up-regulated by the CSF of both groups compared to controls and 32.1% down-regulated (Figure 3D). The RRMS specimens in general induced a much more robust transcriptional response compared to the PPMS. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the genes up-regulated by exposure to the CSF of either RRMS or PPMS revealed genes involved in protein transport, actin filament-based processes, protein complex disassembly and nucleo-cytoplasmic transport (Figure 3E). Down-regulated gene ontology categories included response to DNA damage stimulus, protein modification by small protein conjugation or removal, mitochondrial organization, and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 3F). Together these data revealed transcriptional changes that were induced in OPCs by exposure to the CSF of MS patients, regardless of the disease-type, but not by the CSF of patients with other neurological diseases. Of the genes similarly regulated by exposure to the CSF from the RRMS or PPMS group, we noted Pcyt1a, a gene involved in lipid metabolism19 and Rnf26, a gene encoding for a transcriptional regulator20 (Figure 4A). Transcripts uniquely induced by the CSF from RRMS included Ppt1 encoding for a protein involved in lipid catabolism21 and Pla2g7 a gene encoding for phospholipase A2, group VII (platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, plasma) which uses phosphatidylcholine as substrate to generate lysophosphatidylcholine and arachidonic acid22 (Figure 4B). Together these results suggested important differences induced in OPC by treatment with CSF from PPMS or RRMS patients.

Figure 4. Common and unique gene expression changes associated with exposure of rat OPCs to CSF from patients with distinct disease course.

(A) qPCR analysis of genes commonly regulated by exposure of rat OPCs to CSF from RRMS and PPMS patients. (B) qPCR analysis of genes uniquely regulated by exposure of rat OPCs to CSF from RRMS patients. Different colors are used to indicate triplicates for each sample. Values were normalized to Gapdh and statistical differences using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison correction (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Aberrant transcriptional changes in cultured OPC exposed to the CSF from patients with a diagnosis of PP or RR MS

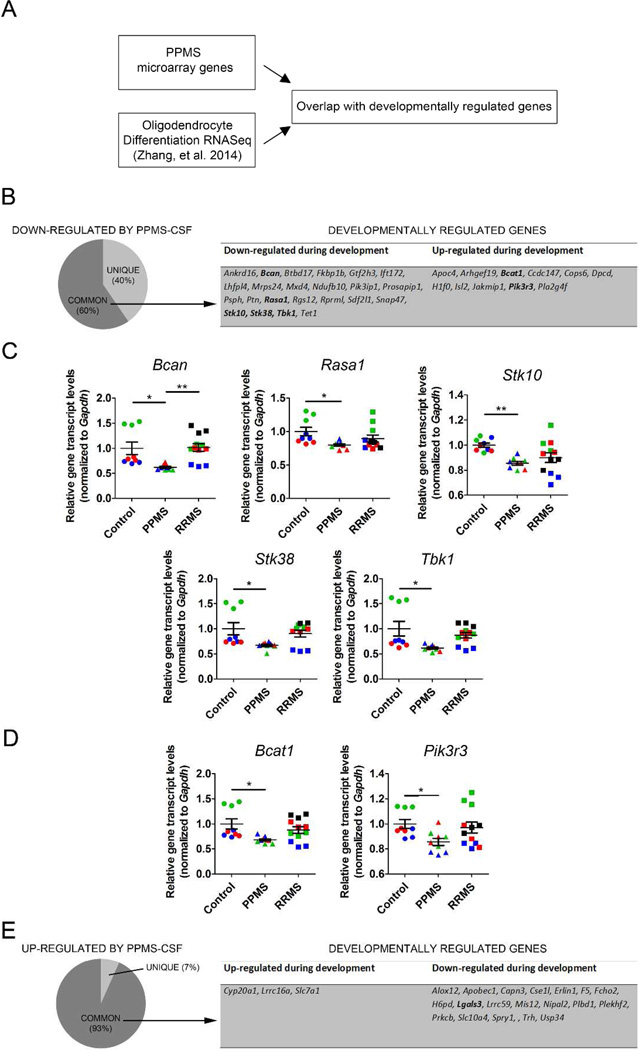

In an attempt to define whether the CSF from PPMS patients induced a pro-differentiative response we overlapped our data set with recently published RNA Sequencing data (Figure 5A) in cultured oligodendrocyte progenitors differentiated into oligodendrocytes23. We further noticed that the percent of overlap between transcripts decreased by CSF exposure and developmentally regulated was 60% (Figure 5B) and included genes that have been previously shown to be down-regulated during oligodendrocyte development including Brevican (Bcan), which has been implicated in regulating process outgrowth in differentiating oligodendrocyte progenitors24, Stk 38 and Stk10, which encode for serine-threonine kinases with the ability to inhibit MAPK activity in cells25, 26 (Figure 5C). Remarkably, the exposure to the CSF from PPMS patients, but not to RRMS CSF induced a down-regulation similar to the one detected during the normal process of differentiation (Figure 5C). Despite these concordant changes, we also detected changes that were discordant between the CSF induction and the physiological process of differentiation. One example is the expression of Bcat1 and Pik3r3, which were down-regulated in OPC exposed to the CSF and up-regulated during differentiation (Figure 5D). Of the genes that were up-regulated by PPMS treatment, we noticed that over 90% were present also in the oligodendrocyte transcriptome (Figure 5E). However, also in this case the changes were discordant, as transcripts that were down-regulated in differentiating oligodendrocytes during developmental myelination were up-regulated by exposure to the CSF from PPMS patients (Figure 6A).

Figure 5. Cerebrospinal fluid from PPMS patients induces aberrant transcriptional changes in oligodendrocyte progenitors.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the analysis between microarray gene changes induced by PPMS-CSF on proliferating OPCs and RNAseq data from Zhang Y, et al 2014 during oligodendrocyte differentiation. (B) Pie chart showing the overlap between the developmentally regulated genes and the genes down-regulated by exposure to the CSF of PPMS patients. Note that genes were labeled as “common” (present in both data sets) or “unique” (only present in the OPC treated with CSF); the table depicts developmentally regulated genes also modulated by CSF exposure. (C) qPCR analysis of down-regulated gene targets. Different colors are used to indicate triplicates for each culture exposed t CSF. Values were normalized to Gapdh and statistical differences using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison correction (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). (D) qPCR analysis of genes down-regulated by CSF exposure but up-regulated during oligodendrocyte differentiation. (E) Pie chart showing the overlap between the developmentally regulated genes and those up-regulated by CSF exposure. The table identifies some of the genes regulated by the development al process and by exposure to CSF.

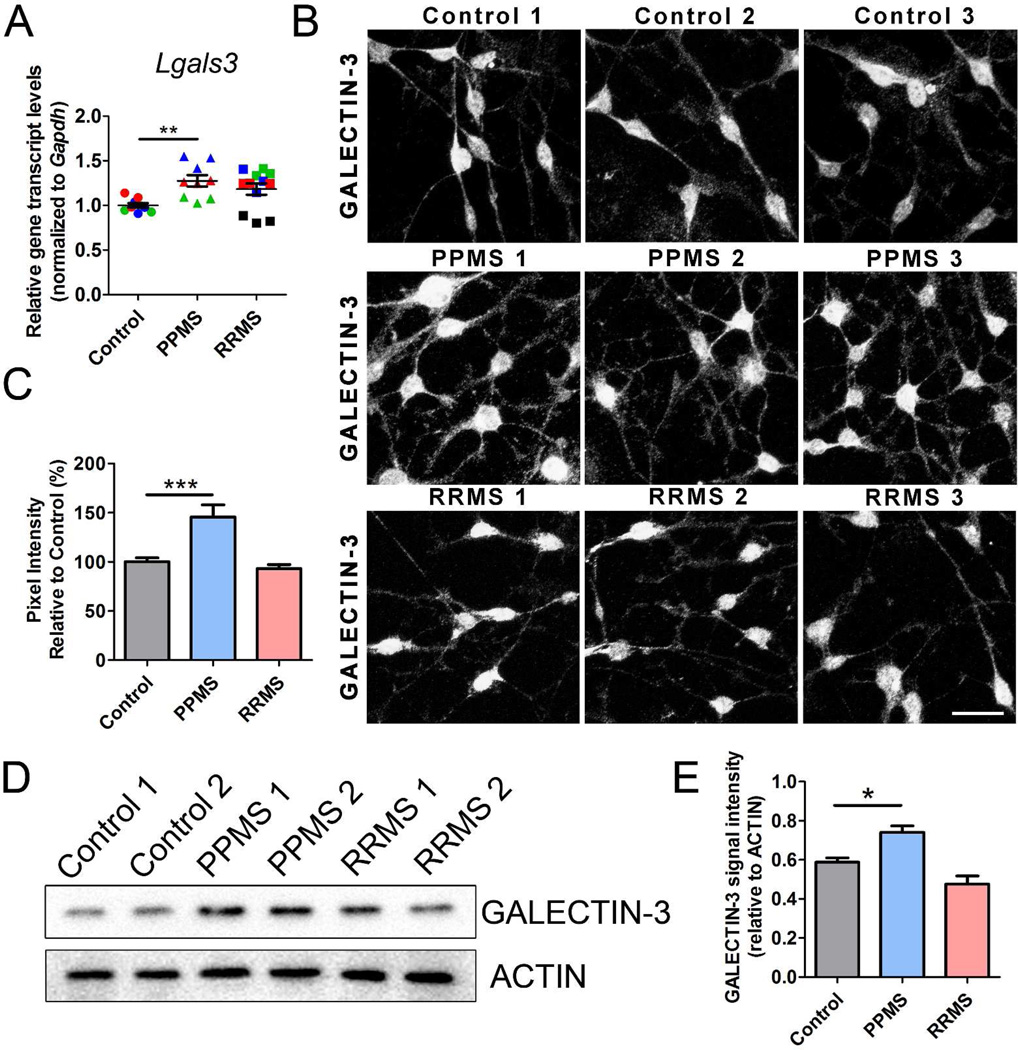

Figure 6. Exposure of rat OPCs to the CSF from PPMS patients results in high Galectin-3 transcript and protein levels.

(A) qPCR analysis of Lgals3 in OPCs treated with CSF from different patient groups. Values were normalized to Gapdh and statistical differences evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison correction (**p<0.01). (B) GALECTIN-3 staining in rat OPCs treated with CSF from control, PPMS and RRMS patients. Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) GALECTIN-3 signal intensity, quantified from (B). (D) Western blot analysis of GALECTIN-3 levels in OPCs treated with CSF from different patient groups. (E) GALECTIN-3 signal intensity, quantified from (D) relative to ACTIN levels. Statistical differences in (C) and (E) were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction (*p<0.05; ***p<0.001 vs. control).

Particularly relevant, was the gene Lgals3, which encodes GALECTIN-3 and was only up-regulated in the PPMS group. This gene had been previously implicated in diverse cellular functions, including cell adhesion and growth and also OPC branching27. To further understand whether this increase was reflected also in higher protein levels, we performed immunocytochemistry with GALECTIN-3 antibodies in primary cultures of proliferating OPCs exposed to the CSF from control subjects or from patients with a diagnosis of RRMS, or PPMS (Figure 6B). Consistent with a protein up-regulation, GALECTIN-3 signal intensity was increased 1.4 fold (p < 0.01) in oligodendrocyte lineage cells exposed to PPMS CSF compared to RRMS or control (Figure 6C) and this corresponded to a two-fold increase in the number of primary branches extending from the soma (p < 0.001). Western blot analysis confirmed the up-regulation of GALECTIN-3 in cultured cells (Figure 6D–E). Thus, exposure to the CSF from PPMS triggered an aberrant transcriptional response characterized by the up-regulation of genes involved in morphological differentiation.

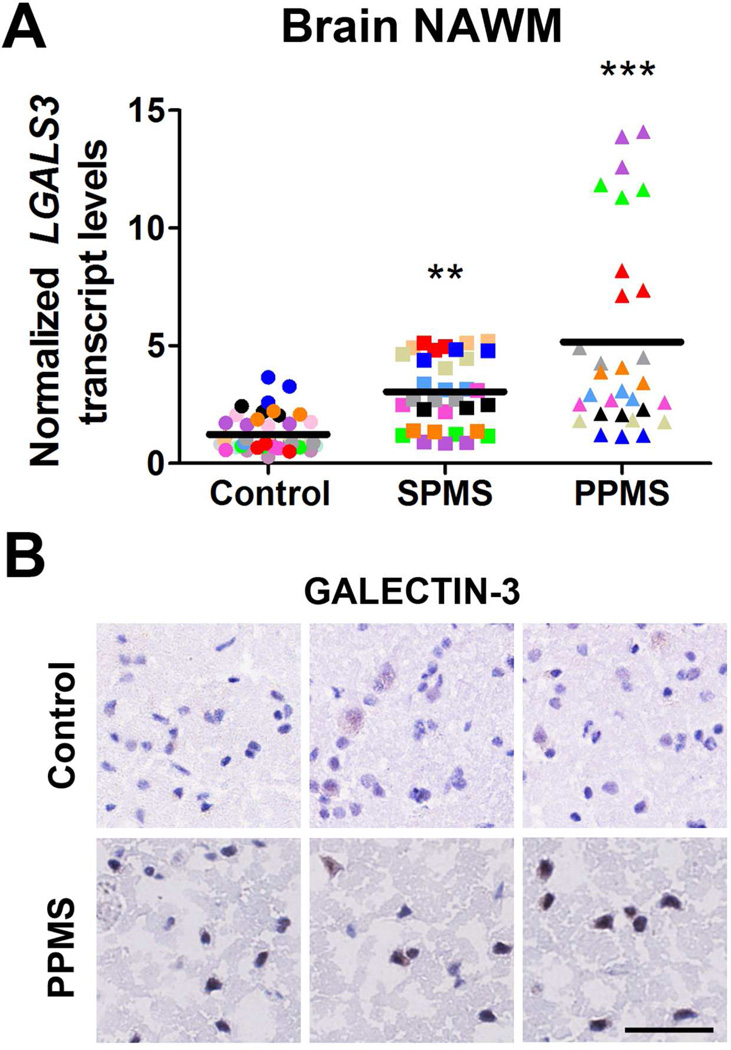

LGALS3 mRNA transcript levels are up-regulated in human post-mortem PPMS brain normal-appearing white matter

To validate the findings in rodent OPC in humans, we also analyzed RNA that was isolated from post-mortem brain tissue from patients with secondary progressive or primary progressive disease course at the time of death (Table 3). We opted to measure the transcripts only in the normal-appearing white matter of human patients, in order to avoid potential complications consequent to cellular infiltration, we only selected tissue devoid of inflammatory cells, as also previously described28. Interestingly, we detected an increasing trend for LGALS3 levels in SPMS patients, with even higher levels in patients with a primary progressive disease course (Figure 7A). Also in this case the increased transcript levels were accompanied by the detection of higher protein levels in MS brain sections (Figure 7B).

Table 3.

Characteristics of human post-mortem samples

| Patient ID |

Gender | Age | MS type |

MS duration (yrs) |

Post-mortem interval (hrs) |

Additional Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS4218 | F | 63 | CP | 18 | 15 | Cerebral atherosclerosis, chronic UTI |

| MS3931 | F | 74 | PP | 11 | 9.5 | Pneumonia |

| MS2771 | F | 64 | SP | 33 | 17.3 | |

| MS377 | F | 50 | SP | NA | 22 | Pneumonia |

| MS094 | F | 42 | PP | 6 | 11 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS088 | F | 54 | SP | NA | 22 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS342 | F | 35 | SP | 5 | 9 | |

| MS076 | F | 49 | SP | 18 | 31 | Chronic renal failure, heart disease |

| MS058 | F | 51 | SP | 21 | 15 | |

| MS4201 | F | 75 | CP | 29 | 13.8 | Chronic UTI, HPN, hypothyroidism, migraine |

| MS3010 | F | 50 | SP | 24 | 15 | |

| MS062 | F | 49 | SP | 19 | 10 | Respiratory infection |

| MS2765 | F | 51 | CP | 32 | 9 | |

| MS109 | F | 60 | SP | 25 | 22 | Cerebral atherosclerosis, MI |

| MS3840 | F | 61 | PP | 17 | 22.8 | Chronic UTI, Pneumonia |

| MS093 | F | 57 | SP | 26 | 25 | Pneumonia |

| MS231 | F | 59 | PP | 27 | 12 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS273 | M | 61 | PP | 31 | 24 | Septicemia, UTI |

| MS097 | M | 55 | SP | 22 | 31 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS286 | M | 45 | SP | 16 | 7 | |

| MS2946 | M | 59 | PP | 12 | 15 | Dementia |

| MS3502 | M | 78 | SP | 52 | 15.5 | Bell’s Palsy, CVA, seizure disorder |

| MS100 | M | 46 | SP | 8 | 7 | Acute polyarthritis, peptic ulceration, pneumonia |

| MS141 | M | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| MS083 | M | 54 | PP | 16 | 13 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS060 | M | 55 | SP | 43 | 16 | |

| MS122 | M | 44 | SP | 10+ | 16 | Bronchopneumonia |

| MS104 | M | 53 | SP | 11 | 12 | UTI |

| N3175 | F | 54 | - | - | 21.5 | Hypothyroidism, pancytopenia, T1DM |

| N3348 | F | 76 | - | - | 9 | CHD, HPN, T1DM |

| PDC08 | F | 71 | - | - | NA | Cerebral atherosclerosis |

| N3406 | F | 72 | - | - | 20.1 | Breast cancer, CHF, TSC |

| N3482 | F | 79 | - | - | 14 | CHD, HPN |

| N3558 | F | 59 | - | - | 19.5 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| N3543 | F | 73 | - | - | 12 | COPD |

| CO14 | M | 64 | - | - | 18 | MI, TIA |

| PDC05 | M | 58 | - | - | NA | Cervical ependymoma |

| CO51 | M | 68 | - | - | 24 | IHD |

| N3276 | M | 54 | - | - | 19 | CHD, CKD, PVD |

| N3602 | M | 66 | - | - | 13.1 | Metastatic larynx cancer, T1DM |

| CO36 | M | 68 | - | - | 30 | CAD, cor pulmonale, IPF |

| N3529 | M | 58 | - | - | 9 | Colon cancer |

| N3611 | M | 64 | - | - | 17.5 | CAD, lymphoma |

| N3535 | M | 81 | - | - | 14 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| N3606 | M | 71 | - | - | 11.5 | COPD |

| N3589 | M | 53 | - | - | 15 | Melanoma |

| PDC022 | M | 71 | - | - | NA |

CP=chronic progressive. PP=primary progressive. SP=secondary progressive. NA=not available. UTI=urinary tract infection. HPN=hypertension. MI=myocardial infarction. CVA=cerebral vascular accident. T1DM=type 1 diabetes mellitus. CHD=coronary heart disease. CHF=congestive heart failure. TSC=tuberous sclerosis complex. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. TIA=transient ischemic attack. IHD=ischemic heart disease. CKD=chronic kidney disease. PVD=peripheral vascular disease. CAD=coronary artery disease. IPF=idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Figure 7. LGALS3, the gene encoding for Galectin 3 is up-regulated in human normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) from secondary progressive and PPMS patients.

(A) Quantitative PCR analysis of LGALS3 in human NAWM, normalized to the geometric average of GAPDH, DHX32 and RPLP0. Different colors are used to indicate triplicates for each sample. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction (**p<0.01; ***p< 0.001 vs. control). (B) Immunostaining of NAWM slides with antibodies against GALECTIN-3 and counterstained with hematoxylin to identify cellular nuclei. Scale bar = 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to define whether human CSF samples form patients with benign or aggressive disease course could differentially modulate the behavior of cultured oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPC). In MS lesions, OPCs migrate to plaque areas, but often fail to efficiently remyelinate possibly due to aberrant intracellular signaling pathways, and extracellular factors inhibiting differentiation (for review see29) and inefficient repair could results in a more aggressive disease course. In this study we tested the overarching hypothesis that soluble factors in the CSF could influence the ability of OPCs to differentiate and therefore affect their ability to effectively repair damaged myelin. Because OPC differentiation is characterized by the execution of a complex transcriptional program, we sought to define the unique transcriptional signature induced in cultured OPCs by exposure to the CSF from multiple sclerosis patients with a more benign (i.e., RRMS) or aggressive (i.e., PPMS) disease course. One of the most striking observation was that exposure to CSF from the RRMS group resulted in large changes of the OPC transcriptome while only a small number of unique transcriptional changes occurred in OPCs exposed to CSF from PPMS patients. These results are consistent with the fact that PPMS disease course is characterized by prominent neurodegeneration, and modest inflammatory demyelination and possibly fewer soluble ligands in the CSF.

A recent manuscript had reported that the CSF from patients with a diagnosis of PPMS and SPMS could induce differentiation of human neural precursor cells in vitro30. However, only specific markers were tested to evaluate differentiation. Our study employs an array method to evaluate the overall effect of the exposure to CSF from PPMS or RRMS patients on the OPC transcriptome. In agreement with the previously published study, we noticed that only the CSF from PPMS patients (and not from RRMS) elicited a pro-differentiative response in OPC, that was defined in terms of: increased branching, as sign of morphological differentiation, down-regulation of molecules associated with the progenitor state (i.e. Lingo1, Pdgfra,) and a modest up-regulation of the myelin gene Mag. The increased branching was correlated with the detection of higher transcript levels of Lgals3, a gene encoding for the galactoside-binding protein GALECTIN-3, that has been previously involved in promoting OPC branching27. The exact mechanism as to how GALECTIN-3 regulates OPC differentiation is unknown; however, carbohydrate interactions may mediate its effect. Interestingly, however, in physiological conditions Lgals3 is mostly expressed by astrocytes and microglia and down-regulated during the process of OPC differentiation. In OPCs exposed to PPMS CSF, however GALECTIN-3 is up-regulated and this results in enhanced branching. These transcriptional changes occurred not only in rodent cells but also in human normal-appearing white matter from both SPMS and PPMS patients and it was associated with a corresponding increase in protein levels.

Unfortunately, however, despite the evidence of pro-differentiative effects of the exposure to CSF from PPMS patients, the overall transcriptional changes induced by the CSF were discordant from those occurring during the differentiation of OPC into oligodendrocytes and this revealed the activation of an aberrant transcriptional program in OPC, which was likely associated with impaired differentiation. This suggests that molecules in the CSF of PPMS patients have the capability to up-regulate genes associated with a pro-differentiative effect but are unable to induce the entire transcriptional program leading to successful differentiation and enhanced repair. Future studies are needed to define the identity of these signals and the precise intracellular mechanism modulating the transcriptional effects.

| UP-REGULATED | |||

| Category | Term | p-value | Genes |

| GO | protein transport | 3.50E-07 | RAB3A, AP1M1, YWHAZ, SEC31A, EXOC7, LOC688430, AP2S1, COPZ1, SNX1, EIF5A, PPT1, CALR, TGFB1, AP1S1, TRIM3, CLK2, POU2F2, RAB11B, APBA2, RHOB, HSPA9, SEC61A2, ASPSCR1, RAMP2, NUP153, ATG9A, RAB4B, STXBP1, TOMM40, STX1B, CDK5, YWHAE, YWHAH, VCP, UBE2M, ARF4, CFL1, PTTG1IP, SORT1, VAMP2, KPNA4, RAB10, COPG, COL20A1 |

| GO | actin filament-based process | 1.24E-04 | FMNL1, ARHGEF2, TAOK2, LOC688430, ACTN1, EVL, MYO9B, CALR, CAPZB, TPM1, CDK5, PPP1R9B, MK1, PFN1, RIL, PTK2B, CFL1, CAP1, DBN1 |

| GO | regulation of protein complex disassembly | 1.52E-04 | ARHGEF2, LOC688430, MAP1A, CFL1, EIF5A, CLIP2, TPM1, CAPZB, MAP6D1 |

| GO | nucleocytoplasmic transport | 0.0026 | ZFP384, LOC688430, HNRPD, EIF5A, CALR, CDK5, TGFB1, CFL1, PTTG1IP, THOC4, KPNA4, MYBBP1A, HSPA9 |

| DOWN-REGULATED | |||

| Category | Term | p-value | Genes |

| GO | response to DNA damage stimulus | 1.97E-05 | TRPC2, XRCC5, BRCC3, RGD1307983, FAM175A, SHFM1, HUS1, TIPIN, BRCA2, POT1B, SOD1, RGD1310686, KIN, GTF2H2, NAE1, RPA3, MNAT1, RPAIN, MAPK14, FTSJD2, RNF168, AATF, MCTS2 |

| GO | protein modification by small protein conjugation or removal | 2.21E-05 | ATG10, BRCC3, COPS5, VHL, UBE2G1, ANAPC11, RBBP6, NAE1, MTMR11, PIAS3, TRIM32, UBA3, FTSJD2, RNF168, CHFR |

| GO | mitochondrion organization | 5.51E-05 | CAV2, MTX1, TIMM10, BNIP3, SYNJ2BP, TIMM8B, TFAM, NRF1, SH3GLB1, GFM1, FXC1, TOMM20, TOMM22, PMPCB |

| KEGG | Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.0025 | ATP5E, NDUFA8, SDHC, NDUFV1, ATP5F1, NDUFC2, ATP5L, LOC685322, ATP5I, LOC687508, PPA2, ATP5J |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Dr. Thin and Donovan for immunostaining of human brain tissue and Mr. Sowa from Dr. Dickstein’s lab for imaging. Grant support: Consolider-Ingenio CSD2006-49 (Network Group Valencia) from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, (Spain) to GL-R; Instituto Carlos III del Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad PI13/00663 and NIH-NINDS grants R01-NS69385 and R37-NS42925 to PC. JDH holds a postdoctoral fellowship from MS Society Canada and Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS. PC, JDH, OGV responsible for the project design, experimentation on rat oligodendrocyte progenitors, and RNA isolation, figure preparation and writing the manuscript. FZ for array data analysis. GLR, contributed to writing and with ALR-C, JC, to microarray; BC provided CSF samples and clinical evaluation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haines JD, Inglese M, Casaccia P. Axonal damage in multiple sclerosis. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:231–243. doi: 10.1002/msj.20246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagemeier K, Bruck W, Kuhlmann T. Multiple sclerosis - remyelination failure as a cause of disease progression. Histology and histopathology. 2012;27:277–287. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franklin RJ. Why does remyelination fail in multiple sclerosis? Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:705–714. doi: 10.1038/nrn917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi S, Motta C, Studer V, et al. Tumor necrosis factor is elevated in progressive multiple sclerosis and causes excitotoxic neurodegeneration. Multiple sclerosis. 2014;20:304–312. doi: 10.1177/1352458513498128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi S, Furlan R, De Chiara V, et al. Interleukin-1beta causes synaptic hyperexcitability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:76–83. doi: 10.1002/ana.22512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komori M, Matsuyama Y, Nirasawa T, et al. Proteomic pattern analysis discriminates among multiple sclerosis-related disorders. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:614–623. doi: 10.1002/ana.22633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teunissen CE, Koel-Simmelink MJ, Pham TV, et al. Identification of biomarkers for diagnosis and progression of MS by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Mult Scler. 2011;17:838–850. doi: 10.1177/1352458511399614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottervald J, Franzen B, Nilsson K, et al. Multiple sclerosis: Identification and clinical evaluation of novel CSF biomarkers. Journal of proteomics. 2010;73:1117–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutz NW, Viola A, Malikova I, et al. Inflammatory multiple-sclerosis plaques generate characteristic metabolic profiles in cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolinska A, Blanchet L, Buydens LM, Wijmenga SS. NMR and pattern recognition methods in metabolomics: from data acquisition to biomarker discovery: a review. Analytica chimica acta. 2012;750:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo P, Zhang Q, Zhu Z, Huang Z, Li K. Mining gene expression data of multiple sclerosis. PloS one. 2014;9:e100052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenoglio C, Ridolfi E, Cantoni C, et al. Decreased circulating miRNA levels in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis. 2013;19:1938–1942. doi: 10.1177/1352458513485654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sondergaard HB, Hesse D, Krakauer M, Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Differential microRNA expression in blood in multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis. 2013;19:1849–1857. doi: 10.1177/1352458513490542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otaegui D, Baranzini SE, Armananzas R, et al. Differential micro RNA expression in PBMC from multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidaurre OG, Haines JD, Katz Sand I, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid ceramides from patients with multiple sclerosis impair neuronal bioenergetics. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2014;137:2271–2286. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer MT, Wimmer I, Hoftberger R, et al. Disease-specific molecular events in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 2013;136:1799–1815. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JY, Shen S, Dietz K, et al. HDAC1 nuclear export induced by pathological conditions is essential for the onset of axonal damage. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:180–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoover-Fong J, Sobreira N, Jurgens J, et al. Mutations in PCYT1A, encoding a key regulator of phosphatidylcholine metabolism, cause spondylometaphyseal dysplasia with cone-rod dystrophy. American journal of human genetics. 2014;94:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katoh M. Molecular cloning and characterization of RNF26 on human chromosome 11q23 region, encoding a novel RING finger protein with leucine zipper. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2001;282:1038–1044. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calero G, Gupta P, Nonato MC, et al. The crystal structure of palmitoyl protein thioesterase-2 (PPT2) reveals the basis for divergent substrate specificities of the two lysosomal thioesterases, PPT1 and PPT2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:37957–37964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tew DG, Southan C, Rice SQ, et al. Purification, properties, sequencing, and cloning of a lipoprotein-associated, serine-dependent phospholipase involved in the oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1996;16:591–599. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa T, Hagihara K, Suzuki M, Yamaguchi Y. Brevican in the developing hippocampal fimbria: differential expression in myelinating oligodendrocytes and adult astrocytes suggests a dual role for brevican in central nervous system fiber tract development. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2001;432:285–295. doi: 10.1002/cne.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuramochi S, Matsuda Y, Okamoto M, Kitamura F, Yonekawa H, Karasuyama H. Molecular cloning of the human gene STK10 encoding lymphocyte-oriented kinase, and comparative chromosomal mapping of the human, mouse, and rat homologues. Immunogenetics. 1999;49:369–375. doi: 10.1007/s002510050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enomoto A, Kido N, Ito M, et al. Negative regulation of MEKK1/2 signaling by serine-threonine kinase 38 (STK38) Oncogene. 2008;27:1930–1938. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasquini LA, Millet V, Hoyos HC, et al. Galectin-3 drives oligodendrocyte differentiation to control myelin integrity and function. Cell death and differentiation. 2011;18:1746–1756. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huynh JL, Garg P, Thin TH, et al. Epigenome-wide differences in pathology-free regions of multiple sclerosis-affected brains. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:121–130. doi: 10.1038/nn.3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau LW, Cua R, Keough MB, Haylock-Jacobs S, Yong VW. Pathophysiology of the brain extracellular matrix: a new target for remyelination. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:722–729. doi: 10.1038/nrn3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cristofanilli M, Cymring B, Lu A, Rosenthal H, Sadiq SA. Cerebrospinal fluid derived from progressive multiple sclerosis patients promotes neuronal and oligodendroglial differentiation of human neural precursor cells in vitro. Neuroscience. 2013;250:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]