Abstract

BACKGROUND

Both bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and c-kit+ cardiac stem cells (CSCs) improve left ventricular remodeling in porcine models and clinical trials. We previously showed, using xenogeneic (human) cells in immunosuppressed animals with acute ischemic heart disease, that these 2 cell types act synergistically in combination.

OBJECTIVES

To more accurately model the clinical situation, we tested whether the combination of autologous MSCs and CSCs produced greater improvement of cardiac performance than MSCs alone in a nonimmunosuppressed porcine model of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy.

METHODS

Three months after ischemia/reperfusion infusion injury, Gottingen mini-swine were injected transendocardially with MSCs alone (n = 6) or in combination with cardiac-derived CSCs (n = 8), MSCs, or placebo (vehicle; n = 6). Cardiac functional and anatomic parameters were assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance at baseline and before and after therapy.

RESULTS

Both groups of cell-treated animals exhibited significantly reduced scar size (MSCs: −44.1 ± 6.8%; CSC/MSC: −37.2 ± 5.4%; placebo: −12 ± 4.2%; p < 0.0001), increased viable tissue, and improved wall motion relative to placebo 3 months post-injection. Ejection fraction (EF) improved (MSCs: +2.9 ± 1.6; CSC/MSC: +6.9 ± 2.8; placebo: +2.5 ± 1.6 EF units; p = 0.0009), as did stroke volume, cardiac output, and diastolic strain, but only in the combination-treated animals, which also exhibited increased cardiomyocyte mitotic activity.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings illustrate that interactions between MSCs and CSCs enhance cardiac performance more than MSCs alone, establish the safety of autologous cell combination strategies, and support the development of second-generation cell therapeutic products.

Keywords: cardiac, combination therapy, heart failure, mesenchymal, stem cell

INTRODUCTION

There is accumulating evidence that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a safe and efficacious approach to treating disorders characterized by left ventricular (LV) remodeling (1–3). MSCs are antifibrotic (4,5), produce LV reverse remodeling (6) in both preclinical models and in patients (7), and improve quality of life in patients with heart failure secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy (1,2,8–10). Still, it remains important to define strategies that enhance the actions of MSCs. We previously demonstrated that transepicardial injection of human MSCs plus c-kit+ cardiac stem cells (CSCs) into immunosuppressed swine 2 weeks post-myocardial infarction (MI) improved LV performance and reduced myocardial scar to a greater degree than either cell type alone (11). Similarly, we showed that cell engraftment and systolic and diastolic recovery were superior with combination therapy (11). We hypothesized that transendocardial administration of autologous MSCs plus CSCs would similarly produce greater therapeutic potential than MSCs alone in a swine model of chronic heart failure due to post-infarct LV remodeling.

METHODS

All experiments were conducted in female Göttingen swine (12). Twenty-eight animals survived closed-chest ischemic reperfusion MI induced by inflation of a coronary angioplasty balloon in the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery, as previously described (12). Animals were randomized to receive transendocardial injections of either: 1 × 106 autologous CSCs co-administered with 200 × 106 MSCs; 200 × 106 MSCs alone; or placebo (Plasma-Lyte, Baxter International Inc., Deerfield, Illinois). Each animal underwent extensive safety evaluation. Noninvasive cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed (12,15,16). The study design is outlined in Online Figure 1 and the timeline for serial measurements of cardiac function can be seen in Online Table 1.

CELL MANUFACTURING AND DELIVERY

CSCs were isolated from 5 to 8 endomyocardial biopsies (1 to 2 mm), obtained from the septal wall of the right ventricle immediately following MI/reperfusion, then expanded, harvested, and cryopreserved as previously described (17–19). MSCs were isolated from bone marrow obtained from the tibial cavity as previously described (11). On the morning of stem cell injection, cells were thawed, washed, re-suspended in Plasma-Lyte A (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois), counted, and total cell viability determined. Cells (200 × 106 MSCs ± 1 × 106 CSCs) were resuspended in Plasmalyte A (total volume: 6 ml) before injection. Criteria for release of product were cell viability ≥70% and negative sterility testing. Placebo injection consisted of Plasmalyte alone (Online Appendix).

Transendocardial stem cell injection (TESI) was performed 3 months post-MI using the NOGA® system for electroanatomical mapping (Biosense Webster, Inc., Diamond Bar, California) (14). The mapping catheter was advanced through an 8-F introducer sheath and retrograde across the aortic valve into the left ventricle. A complete map of LV geometry and function was generated by collecting local position and electrocardiographic data at >50 points in the endocardium. Cells were injected using the NOGA Myostar catheter directly into the endocardium in ≈0.5 cc aliquots for each of 10 sites encompassing the infarction and its viable border zone (BZ) (unipolar voltage of ≥6 mV). Injection sites were recorded both in the electroanatomical NOGA map and in 2 orthogonal radiographic projections, and marked on a tracing of the endocardial silhouette.

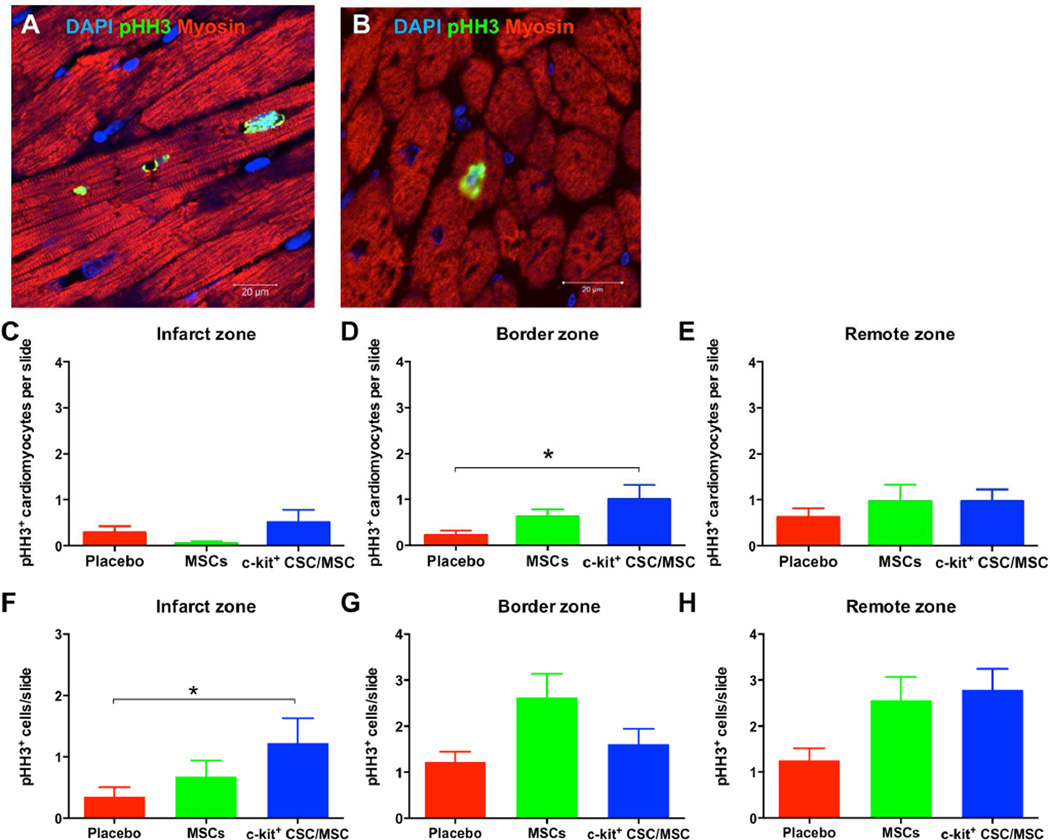

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

Twelve slides (4 each per infarct zone [IZ], BZ, and remote zone [RZ]) were randomly chosen from each animal for quantification of phospho-histone H3 (pHH3) positive nuclei (see Online Appendix). Slides were examined by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX81, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and the number of pHH3 positive nuclei was quantified per slide. Representative samples were selected and stained with anti-pHH3 and anti-myosin light chain 2 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, Colorado). Image acquisition was performed with a Zeiss LSM-710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, New York).

STUDY ENDPOINTS AND ASSESSMENTS

Specified safety endpoints were assessed. Endpoints included: survival; body weights; and continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring for ventricular or supraventricular arrhythmias post-injection using implanted monitoring devices (Reveal® DX 9528 and Reveal® XT 9529 [Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota]), as described (6). Laboratory values included hematology, chemistry, and markers of cardiac injury: creatine phosphokinase, creatine kinase MB isoenzyme, and troponin I (Online Table 2 and Online Figure 2); and, at sacrifice, gross and microscopic tissue analysis from brain, liver, spleen, kidney, lung, and ileum for the presence of neoplastic tissue at necropsy were obtained. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed using a 3.0T clinical scanner (Magnetom, Siemens AG, Munich, Germany). Swine underwent serial CMR at baseline, 1 and 3 months post-MI, and 1, 2, and 3 months post-TESI. Global and regional function were assessed through the measurement of end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, stroke volume (SV), EF, scar size, viable tissue, Eulerian circumferential strain, diastolic strain rate, and perfusion. Endothelial function was measured by the brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) (20) (Online Appendix).

STATISTICS

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. All data points were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Version 4.03, La Jolla, California). For within-group changes, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. For between-group comparisons, unpaired 2-tailed Student t test, 1- and 2-way ANOVA were applied with Tukey’s multiple comparison test when applicable. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline and post-MI conditions for all animals were assessed (Online Table 2). There were no differences between groups for body weight or age at baseline or at scheduled time points (Online Tables 1& 2). Serum hematology, chemistry, and cardiac enzymes were measured at several time points throughout this study. There was no evidence of clinically relevant laboratory abnormalities after TESI (Online Figure 2) in any of the groups. TESI was tolerated; there were no sustained arrhythmias and no evidence of ectopic tissue formation (Online Tables 3 and 4).

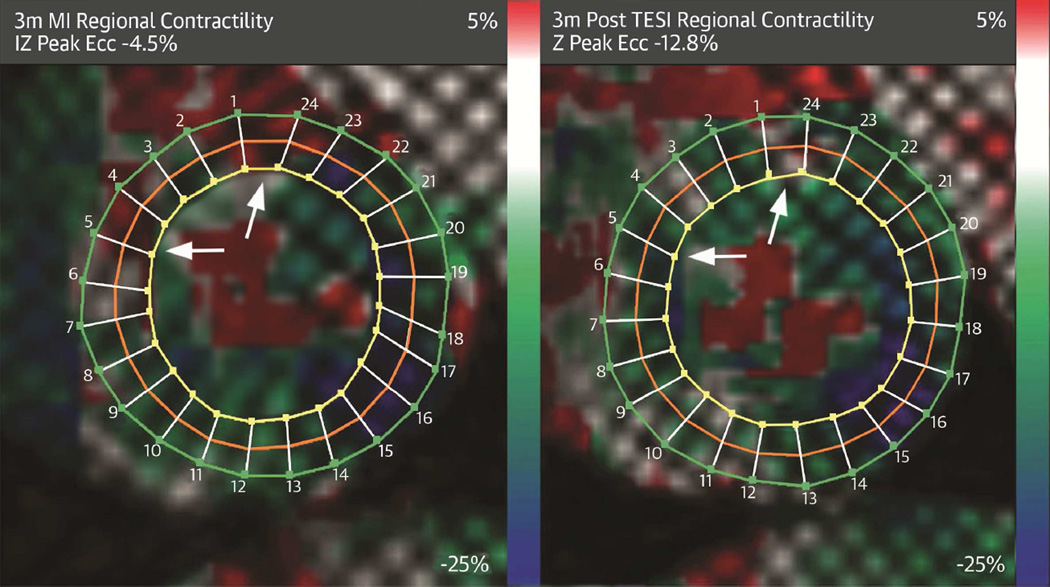

All study groups had similar infarct sizes, whether evaluated as a percentage of LV mass or absolute scar size 3 months after infarction (Online Table 5). Stem cell treatment, but not placebo, produced substantially reduced scar size (CSC/MSC: −37.2.9 ± 5.4%; MSCs: −44.1 ± 6.8%; placebo: −12.9 ± 4.2; p < 0.0001) and increased viable tissue (CSC/MSC: 30.9 ± 7%; MSCs: 43.7 ± 13.3%; placebo: 13.5 ± 5.9; p = 0.0002) relative to placebo (Figure 1, Online Table 5). Scar size reduction was evident 1 month post-TESI and persisted for 3 months (Figure 1). There was a strong correleation between scar size, measured by delayed enhancement CMR, and scar size, measured by gross pathology sections (r = 0.93; 95% confidence interval: 0.80 to 0.98; p < 0.0001; Online Figure 3).

FIGURE 1. Antifibrotic Effects Post-TESI.

Short-axis sections of delayed enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance (A–C) depict the infarct extension (scar = red with white arrows) before treatment and, as seen in comparable gross pathology sections (D–F) 3 months following transendocardial stem cell injection (TESI). While TESI with placebo (n = 6) increased scar size from 7.2 g to 9.0 g (A,D), scar reductions occurred with autologous MSC (n = 5) from 9.7 g to 5.9 g (B,E) and autologous combination of ckit+ CSC/ MSC (n = 7) from 8.9 g to 5.8 g (C,F). (G) Cell-treated groups have similar scar size reduction (between-group comparison 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] p < 0.0001) and (H) increased viable tissue (between-group comparison 2-way ANOVA p = 0.0002). Graphs = mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 within-group repeated measures 1-way ANOVA; 2-way ANOVA between-group comparison and Tukey's multicomparison test **p < 0.05 CSC/MSC vs. placebo at 1, 2, and 3 months post-TESI and +p < 0.05 MSC vs. placebo at 1, 2, and 3 months post-TESI. CSC = cardiac stem cell; LV = left ventricular; MSC = mesenchymal stem cell; MI = myocardial infarction.

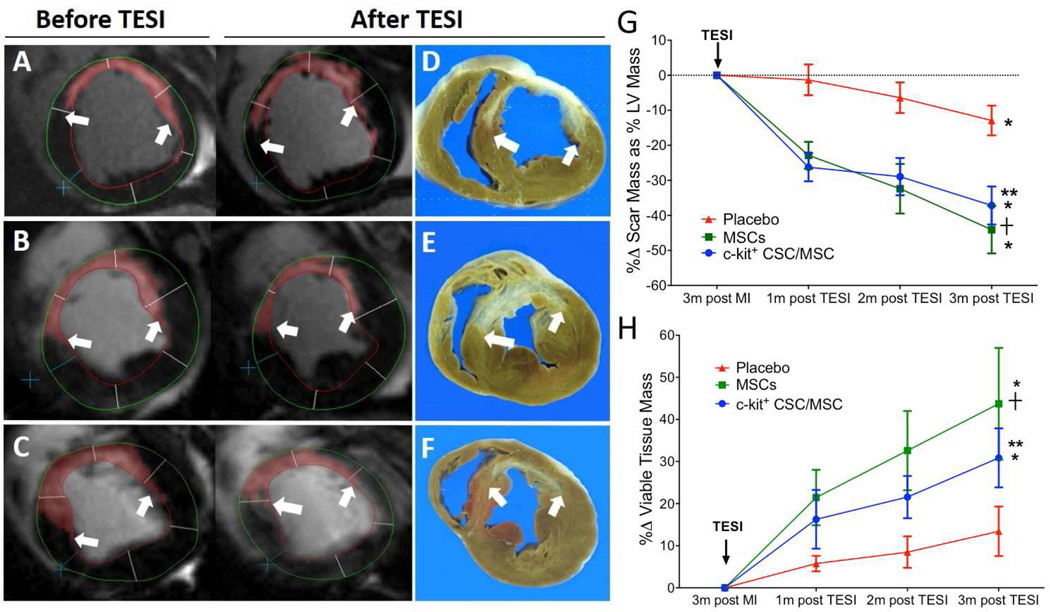

All animals had similar depression of EF due to MI (Online Table 6). EF increased 3 months post-TESI in the combination group by 6.9 ± 2.8 EF units (p = 0.0003), in MSCs by 2.9 ± 1.6 (p = NS), and placebo by 2.5 ± 1.6 (p = NS; between-group p = 0.0009, CSC/MSC vs. MSC and CSC/MSC vs. placebo, each p <0.05). EF as a percent change from post-MI improved only in the CSC/MSC group, 20.61 ± 2.11%, 14.37 ± 3.64%, and 13.9 ± 6.2%, at 1, 2, and 3 months post-TESI, respectively (between group p = 0.0004; 3 months post-MI vs. 1, 2, and 3 months post-TESI, each p < 0.05) but was unchanged in MSCs and placebo (each p =NS) (Figure 2B). Ejection fraction restoration was accompanied by a substantial improvement in stroke volume in the CSC/MSC group, exceeding that of MSCs or placebo (CSC/MSC: 47.2 ± 11.1% vs. MSCs: 21.2 ± 4.7% vs. placebo: 22.4 ± 12.0, between-group p = 0.008; CSC/MSC vs. MSC, MSC vs. placebo, each p <0.05; Figure 2C). Furthermore, cardiac output increased only in the CSC/MSC group: (50.5 ± 11.3%, p = 0.007; MSCs: 27.8 ± 13.6%, p = 0.2; placebo: 15.5 ± 9.5%, p = 0.02; between-group comparison p = 0.008) (Figure 2D, Online Table 6).

FIGURE 2. EF Improvement Post-TESI.

Change in ejection fraction (EF) for individual animals for EF units (A) and as a percent change (B; p = 0.01) post-TESI. Accompanying this EF restoration was a substantial improvement in the CSC/MSC group in (C) stroke volume (p = 0.008) and (D) cardiac output, which increased only in the CSC/MSC group (p = 0.007). Graphs represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 1-way ANOVA, 3 months post-MI vs. 1, 2, and 3 months post TESI with CSC/MSC; **p < 0.05 CSC/MSC vs. placebo; †p < 0.05 CSC/MSC vs. MSCs. CO = cardiac output; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

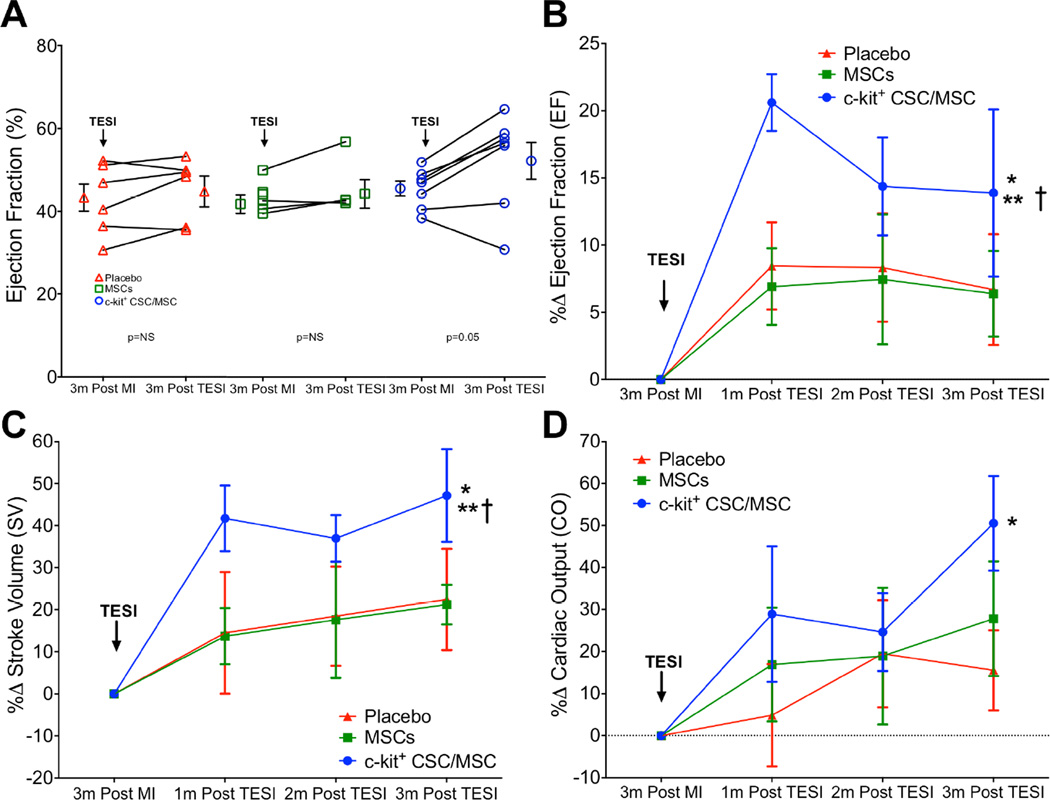

Circumferential strain rate (peak Eulerian circumferential shortening strain [Ecc]), a measure of regional contractility calculated from tagged CMR, showed improved regional function (greater negative delta) of the IZ only in cell-treated groups (CSC/MSC: −3.2 ± 1.2, p = 0.004; MSCs: −1.1 ± 0.9, p = 0.04; placebo delta:0.2 ± 0.9 p = NS; Figure 3A; between-group comparison p = 0.1). TESI did not improve regional function in the BZ compared to placebo (data not shown).

FIGURE 3. Contractility and Diastolic Strain.

(A) Circumferential strain rate (peak Ecc) in the infarct zone improved in both cell-treated animal groups, but not the placebo group (*MSC: p = 0.04; ** CSC/MSC: p <0.004; between-group comparison: p = 0.1. (B) Diastolic strain increased only in the combination-treated animals (*p = 0.04), remaining unchanged in the MSC (p = NS) and placebo (p = NS) groups (between-group comparison: p = 0.9). Ecc = Eulerian circumferential shortening strain; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

We used CMR tagging to evaluate diastolic performance. Diastolic strain increased only in the combination-treated animals (0.44 ± 0.07; p = 0.04) and remained unchanged in the MSC (0.38 ± 0.11; p = NS) and placebo (0.25 ± 0.08; p = NS) groups (between-group comparison p = 0.9) (Figure 3B).

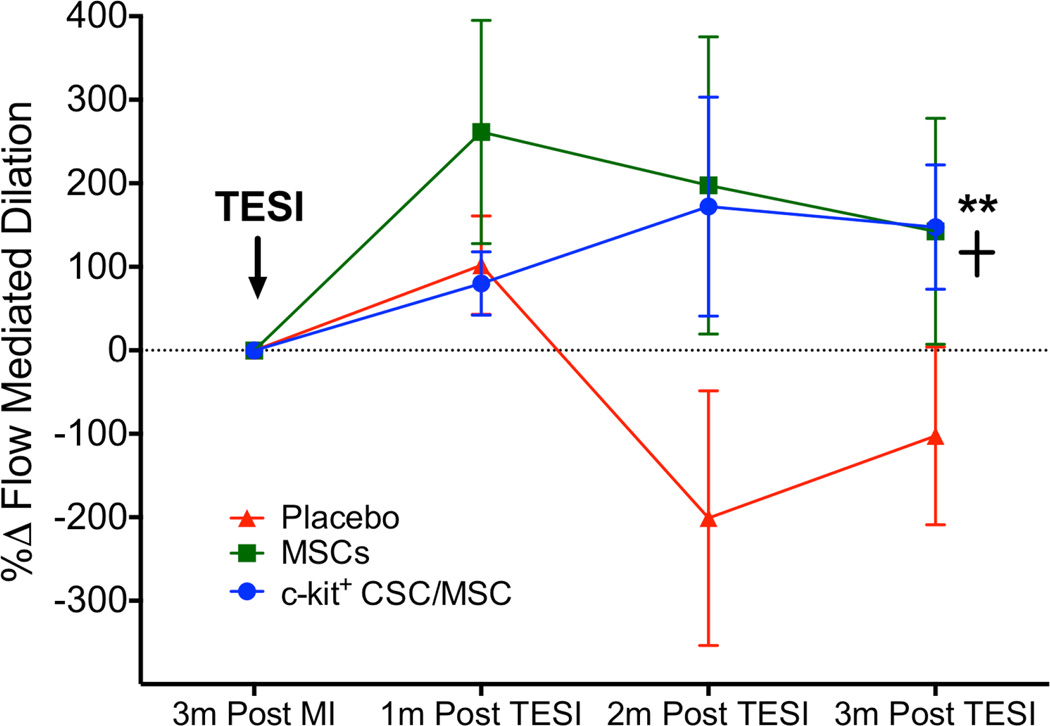

We also explored the impact of cell therapy on peripheral vascular function by measuring FMD of the brachial artery, which improved similarly in both cell-treated groups but worsened in the placebo group (CSC/MSC: +147.6 ± 74.5%, 1-way ANOVA p <0.0001; MSCs: 142.5 ± 135.4%, 1-way ANOVA p = 0.04; placebo: −102.4 ± 106.5%, 1-way ANOVA p = NS; between-group comparison p = 0.01; Tukey's multiple comparison test p <0.05 CSC/MSC vs. MSC and p <0.05 MSCs vs. placebo) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Endothelial Function.

Flow-mediated dilation improved endothelial function in both cell-treated groups CSC/MSC vs. MSCs: **p <0.05; MSCs vs. placebo: +p < 0.05. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

We analyzed 11 to 12 slides from each of 20 pigs. In the combination group there were significantly more mitotic pHH3-positive nuclei found within the myocardium in the infarct zone (Figure 5C) per slide compared to the placebo group (CSC/MSC: 1.2 ± 0.2; MSCs: 0.7 ± 0.3; placebo: 0.2 ± 0.1; p = 0.05). Importantly, when we co-stained pHH3+ slides with anti-Myosin Light Chain 2, a cardiac-specific marker, (Figure 5A, B) we found increased cardiomyocyte mitosis (Figure 5C–E) with a greater number of pHH3+ cardiomyocytes in the border zone (TESI site) in the CSC/MSC group (1.0 ± 0.3) compared to the placebo group (0.2 ± 0.1; p = 0.05). Similarly the total number of pHH3+ cells in the infarct zone in the CSC/MSC group (1.2±0.1) was significantly greater than in the placebo group (0.4±0.03; p = 0.0465; Figure 5G–H).

FIGURE 5. Treatment-enhanced Myocardial Mitotic Activity.

Confocal microscopy depicts increased mitotic activity of endogenous cardiomyocytes (pHH3+ nuclei) in border (A) and remote (B) zones in cell-treated hearts at 3 months post-TESI. Based on the average number of pHH3+ mitotic cells within the myocardium per slide per group in the infarct (C), border (D), and remote (E) zones, combination cell therapy significantly increased myocardial mitotic activity in the border zone compared to placebo (*p = 0.05). (F, G, H) According to the average number of pHH3+ cardiomyocytes per slide per group in the infarct (F), border (G), and remote (H) zones, combination therapy produced significant increases in cardiomyocytes in the infarct zone (TESI site) compared to placebo (*p = 0.05). DAPI = 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; PHH3 = phosphohistone H3; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

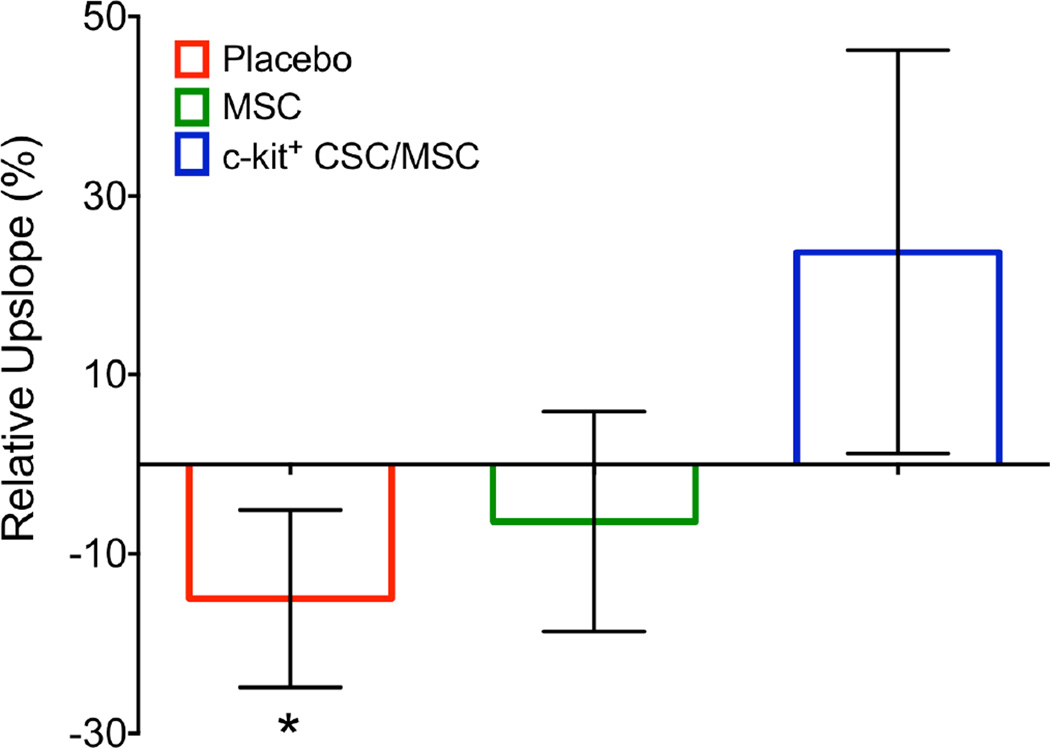

We assessed perfusion in all 3 zones (IZ, BZ, and RZ). In the IZ, there was a borderline trend towards progressively deteriorating tissue perfusion (−15.0 ± 9.9%; p = 0.07), which was offset by each cell therapy group (MSC −6.4 ± 12.2%; p = 0.32; CSC/MSC 23.7 ± 22.5%; p = 0.72) when comparing 3 months post-MI and 3 months post-TESI (Figure 6). Heart sections from each zone were stained with vonWillebrand reagent and blood vessels were counted. Vascular density was similar in all 3 groups (Online Figure 4).

FIGURE 6. Infarct Zone Perfusion.

Using contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance images there was a trend towards deterioration of tissue perfusion in the infarct zone with placebo (−15.0 ± 9.9%;*p = 0.07). This decline did not occur in the cell treatment groups (MSC −6.4 ± 12.2%, p = 0.32; c kit+ CSC/MSC 23.7 ± 22.5%, p = 0.72). Bar graphs depict change in tissue perfusion from 3 months post-MI and 3 months post-TESI as measured by upslope analyses. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

This preclinical animal study was designed to provide a rigorous placebo-controlled and blinded safety and efficacy assessment using autologous MSCs alone or in combination with autologous CSCs in a chronic MI-reperfusion model. There are 3 major findings. First, we established that coinjection of autologous MSCs and CSCs is safe and not associated with an increased risk of adverse effects. Second, both cell treatments produced similar antifibrotic effects. Third, only the coadministration of cells improved myocardial contractile performance. These findings are the first demonstration that autologous cell combination therapy is superior to MSCs alone in a model of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, and, therefore, have important implications for future clinical trial design.

The efficacy of autologous MSCs alone has been established preclinically and clinically (3,4). MSCs are thought to act primarily via paracrine signaling (21–23), proangiogenic effects (24,25), and stimulation of endogenous CSC proliferation, differentiation (26–29), and recruitment (30). For the combination of the 2 cell types, efficacy was demonstrated by improvement in both structural and functional parameters. CSCs are located in niches within the heart and they exert important regulatory and regenerative roles (31) that can be augmented by cell therapy (32). Together these results suggest that TESI, with a combination of MSCs plus CSCs, provides an advantage by overcoming factors that inhibit or counteract the efficacy of the current single cell-type therapy (26).

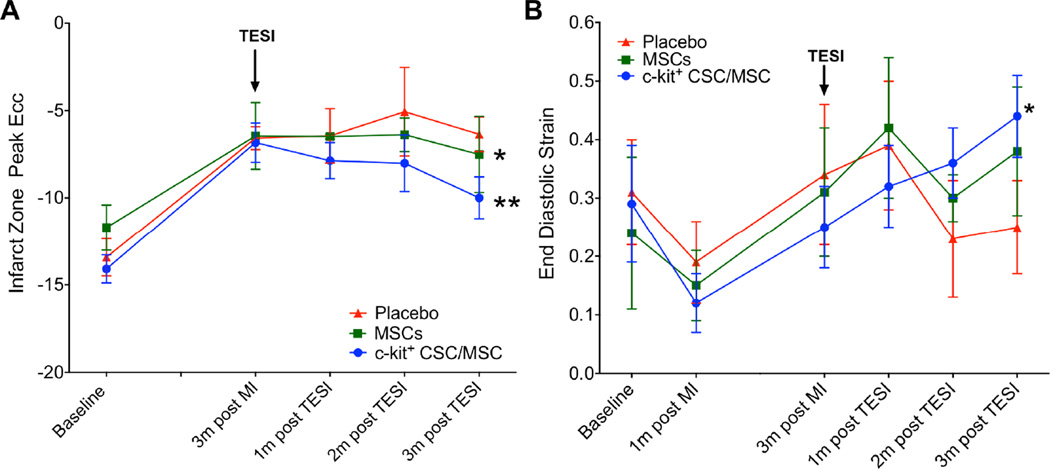

The current study illustrates that autologous MSCs alone or in combination with CSCs similarly reduce infarct size and increase viable tissue compared to placebo. We previously showed a 2-fold greater reduction in scar size with combination therapy compared with either cell administered alone in the setting of acute MI and xenogeneic (human) cells 4 weeks post-injection (11). Coadministration of human CSCs and MSCs also significantly increased (7-fold) retention and engraftment compared to either cell type administrated alone, suggesting direct cell contribution to myocardial regeneration (11). One mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of stem cell therapy is endogenous tissue regeneration including CSC activation and myocyte division (26). Here, we demonstrate that the CSC/MSC combination leads to increased cardiomyocyte mitosis 3 months post-TESI and is associated with sustained improvement of cardiac performance and scar size reduction (Central Illustration). Scar size reduction in all cell-treated pigs was accompanied by substantial recovery in cardiac function, but was less robust when MSCs were administered alone. Interestingly, significant improvement in cardiac function was demonstrated only in the combination group, as measured by EF, SV, cardiac output, regional diastolic strain rate, and endothelial function. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the 2 models: autologous versus xenogenic cells (porcine vs. human), timing (chronic vs. subacute), delivery methods (transendocardial vs. direct via thoracotomy), and immunosuppression (absence vs. presence).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Combination Stem Cell Therapy for Heart Failure.

Tagged harmonic phase cardiac magnetic resonance strain maps show significantly depressed regional function by peak Eulerian circumferential shortening strain (Ecc) at 3 months post-myocardial infarction (A) (white arrows). Red/white indicates weak contractility (more positive Ecc) and green/blue indicates vigorous contractility (more negative Ecc) in harmonic phase strain maps. At 3 months post-cell injection (B), infarct zone (IZ) contractility has improved (less red/white, more green/blue). TESI = transendocardial stem cell injection.

The interactions of immunosuppressant drugs with MSCs remain controversial. Buron et al. showed that cyclosporine A and other immunosuppressant drugs reduce the ability of MSCs to suppress lymphocyte proliferation (39). In contrast, other studies show that cyclosporin A promotes the lymphocyte-suppressing effects of MSCs (40,41). The longer follow-up time may also play a role, suggesting that the combination of stem cells may help sustain the beneficial effects over a longer period of time. Recently the POSEIDON (Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis) (1) and TAC-HFT (Transendocardial Autologous Cells in Ischemic Heart Failure Trial) (2) clinical trials showed that injections of autologous MSCs did not improve EF 12 months post-delivery, although there was significant improvement in the clinical status of patients, as measured by the 6-minute walk distance and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) score.

Our regional analysis of contractility revealed improved peak diastolic strain rate in the targeted areas in the combination-treated animals. Peak diastolic strain rate (42) is a measure of diastolic function that, in impaired myocardial regions, can remain persistently compromised despite complete systolic functional recovery after reperfusion post-MI. FMD, as a measure of endothelial function that can be imaged and quantified as an index of vasomotor function (43), is an attractive technique because it is noninvasive and allows for repeated measurements throughout the study. Both cell-treated groups demonstrated improved FMD, suggesting that stem cell treatment promotes nitric oxide release by the endothelium with subsequent vasodilation. The improvement in endothelial function due to cell therapy in this study is important in the context of our finding that tissue perfusion was improved in the IZ of cell-treated pigs in the absence of increased vascular density. Recently, we showed that MSCs increase endothelial function and release of endothelial progenitor cellsin patients with heart failure (44).

Finally, our study suggested that combining cell types can have clinical benefits such as enhancing myocardial contractile performance improvement (45,46). The strategy tested here supported the feasibility of clinical trials, as both cell types have been tested in early-stage clinical trials. Admixtures of cell types that complement each other’s capabilities seem to provide synergistic benefits that enhance the short- (11) and long-term therapeutic outcomes compared to 1 type of cell alone.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

While this study was well-designed, it lacked a CSC-alone group. However, in early phase clinical trials (33), autologous CSCs had a successful safety profile, including increased EF, regional wall motion, New York Heart Association classification, and quality of life MLHFQ score (33). While in vitro and rodent studies show that CSCs are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair (34), others show that endogenous CSCs may produce new cardiomyocytes at low levels (35). There is now a growing consensus (36) that CSCs alone may be insufficient to repair the failing myocardium and strategies are being developed to address this (37). Adding MSCs may overcome these shortfalls by providing the needed paracrine factors, stromal support, and cell-to-cell contact that contribute to cardiac niche reconstitution. Interestingly, Konfino et al. demonstrated that the type of injury, resection, or infarction dictates the mode of repair in the neonatal and adult murine heart (38). They suggested that MI and subsequent inflammation might inhibit complete regeneration. Thus, MSCs’ immunomodulatory properties render this cell type an indispensable component to effective cell combinations.

Another limitation is that this study lacked dose escalations of each stem cell therapy. However, there are many contradictory reports relating therapeutic efficacy with higher (6) or lower (1) doses of MSCs and there is still no defined efficacious dose range for CSCs. Additionally, using autologous cells precludes quantification of engraftment.

CONCLUSIONS

Transendocardial injection of autologous MSCs plus autologous CSCs produced scar size reduction, increased viable tissue, and restored contractile performance 3 months post-MI. These findings demonstrated for the first time that important interactions between these stem cells produce substantial enhancement in cell-based therapy for at least 3 months post-treatment. The current and previous cell combination studies have demonstrated excellent safety and highly encouraging efficacy profiles, supporting the conduct of clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

Chronic heart failure due to ischemic heart disease involves deleterious myocardial remodeling that impairs patients’ functional capacity. Combination therapy with MSCs and CSCs reduces scar size and improves LV contractility.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Clinical trials are needed to assess the effectiveness and safety of combination cell therapy in patients with heart failure due to ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Martin and Doug Suehr from Biosense Webster, Inc., Diamond Bar, CA, for their assistance with the NOGA system. Neither received compensation for their contribution and David Valdes and Jose Da Silva for valuable technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant R01HL084275 awarded to JMH. JMH is also supported by NIH grants R01HL107110 and UM1HL113460, R01HL110737, and a grant from the Starr Foundation and the SofFer Family Foundation. VK is funded by the American Heart Association.

Disclosures: Dr. Hare reported having a patent for cardiac cell-based therapy. He holds equity in Vestion and maintains a professional relationship with Vestion as a consultant and member of the Board of Directors and Scientific Advisory Board. Vestion Inc. did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study. Dr. Heldman reported having a patent for cardiac cell-based therapy, receiving research support from Biocardia, and being a board member, consultant, and having equity interest in Vestion Inc.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CSC

c-kit+ cardiac stem cell

- FMD

flow-mediated dilation

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- TESI

transendocardial stem cell injection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The other authors report no conflicts

REFERENCES

- 1.Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2369–2379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heldman AW, DiFede D, Fishman JE, et al. Transendocardial Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Mononuclear Bone Marrow Cells for Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: The TAC-HFT Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2014;311:62–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karantalis V, Hare JM. Use of mesenchymal stem cells for therapy of cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1413–1430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amado LC, Saliaris AP, Schuleri KH, et al. Cardiac repair with intramyocardial injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11474–11479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuleri KH, Feigenbaum GS, Centola M, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells produce reverse remodelling in chronic ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2722–2732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suncion VY, Schulman IH, Hare JM. Concise review: the role of clinical trials in deciphering mechanisms of action of cardiac cell-based therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:29–35. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malliaras K, Makkar RR, Smith RR, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells after myocardial infarction: evidence of therapeutic regeneration in the final 1-year results of the CADUCEUS trial (CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricUlar dySfunction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perin EC, Borow KM, Silva GV, et al. A Phase II Dose-Escalation Study of Allogeneic Mesenchymal Precursor Cells in Patients With Ischemic or Non-Ischemic Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306332. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanina C, Hare JM. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Biological Drug for Heart Disease: Where Are We With Cardiac Cell-Based Therapy? Circ Res. 2015;117:229–233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams AR, Hatzistergos KE, Addicott B, et al. Enhanced effect of combining human cardiac stem cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to reduce infarct size and restore cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2013;127:213–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.131110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall FC, Telukuntla KS, Karantalis V, et al. Myocardial infarction and intramyocardial injection models in swine. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1479–1496. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Silva JS, Hare JM. Cell-based therapies for myocardial repair: emerging role for bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the treatment of the chronically injured heart. Methods in molecular biology. 2013;1037:145–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyongyosi M, Dib N. Diagnostic and prognostic value of 3D NOGA mapping in ischemic heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:393–404. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angeli FS, Shapiro M, Amabile N, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: characterization of a swine model on beta-blocker therapy. Comp Med. 2009;59:272–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1422–1434. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jankowski RJ, Haluszczak C, Trucco M, Huard J. Flow cytometric characterization of myogenic cell populations obtained via the preplate technique: potential for rapid isolation of muscle-derived stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:619–628. doi: 10.1089/104303401300057306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston PV, Sasano T, Mills K, et al. Engraftment, differentiation, and functional benefits of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells in porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;120:1075–1083. 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oskouei BN, Lamirault G, Joseph C, et al. Increased Potency of Cardiac Stem Cells Compared with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cardiac Repair. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:116–124. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Xiong Y, Liu D, et al. The effect of enhanced external counterpulsation on C-reactive protein and flow-mediated dilation in porcine model of hypercholesterolaemia. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32:262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2012.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry MF, Engler AJ, Woo YJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell injection after myocardial infarction improves myocardial compliance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2196–H2203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohnishi S, Sumiyoshi H, Kitamura S, Nagaya N. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate cardiac fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis through paracrine actions. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3961–3966. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva GV, Litovsky S, Assad JA, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into an endothelial phenotype, enhance vascular density, and improve heart function in a canine chronic ischemia model. Circulation. 2005;111:150–156. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151812.86142.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang YL, Zhao Q, Zhang YC, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation induce VEGF and neovascularization in ischemic myocardium. Regul Pept. 2004;117:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatzistergos KE, Quevedo H, Oskouei BN, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ Res. 2010;107:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi C, Yamagishi M, Yamahara K, et al. Activation of cardiac progenitor cells through paracrine effects of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quevedo HC, Hatzistergos KE, Oskouei BN, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells restore cardiac function in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy via trilineage differentiating capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14022–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903201106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, Wang S, Yu Z, Hoyt RF, Jr, Qu X, Horvath KA. Marrow stromal cells differentiate into vasculature after allogeneic transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1206–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Windmolders S, De Boeck A, Koninckx R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted platelet derived growth factor exerts a pro-migratory effect on resident Cardiac Atrial appendage Stem Cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;66:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urbanek K, Cesselli D, Rota M, et al. Stem cell niches in the adult mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600635103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazhari R, Hare JM. Mechanisms of action of mesenchymal stem cells in cardiac repair: potential influences on the cardiac stem cell niche. Nature Clin Practice Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(Suppl 1):S21–S26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D'Amario D, et al. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Ellison GM, Vicinanza C, Smith AJ, et al. Adult c-kit(pos) cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell. 2013;154:827–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Berlo JH, Kanisicak O, Maillet M, et al. c-kit cells minimally contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart. Nature. 2014;509:337–341. doi: 10.1038/nature13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. An emerging consensus on cardiac regeneration. Nat Med. 2014;20:1386–1393. doi: 10.1038/nm.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Z, Pu WT. Strategies for cardiac regeneration and repair. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:239rv1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konfino T, Landa N, Ben-Mordechai T, Leor J. The type of injury dictates the mode of repair in neonatal and adult heart. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buron F, Perrin H, Malcus C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells and immunosuppressive drug interactions in allogeneic responses: an in vitro study using human cells. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3347–3352. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi D, Liao L, Zhang B, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells facilitate the immunosuppressive effect of cyclosporin A on T lymphocytes through Jagged-1-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:214–224. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maccario R, Moretta A, Cometa A, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells and cyclosporin a exert a synergistic suppressive effect on in vitro activation of alloantigen-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:1031–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azevedo CF, Amado LC, Kraitchman DL, et al. Persistent diastolic dysfunction despite complete systolic functional recovery after reperfused acute myocardial infarction demonstrated by tagged magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitta Y, Obata JE, Nakamura T, et al. Persistent impairment of endothelial vasomotor function has a negative impact on outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Premer C, Blum A, Bellio M, et al. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells Restore Endothelial Function in Heart Failure by Stimulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karantalis V, Schulman IH, Balkan W, Hare JM. Allogeneic cell therapy: a new paradigm in therapeutics. Circ Res. 2015;116:12–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karantalis V, Balkan W, Schulman IH, Hatzistergos KE, Hare JM. Cell-based therapy for prevention and reversal of myocardial remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H256–H270. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00221.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.