Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most successful bacterial pathogens, harboring a vast repertoire of virulence factors in its arsenal. As such, the genetic manipulation of S. aureus chromosomal DNA is an important tool for the study of genes involved in virulence and survival in the host. Previously reported allelic exchange vectors for S. aureus are shuttle vectors that can be propagated in Escherichia coli, so that standard genetic manipulations can be carried out. Most of the vectors currently in use carry the temperature-sensitive replicon (pE194ts) that was originally developed for use in Bacillus subtilis. Here we show that in S. aureus, the thermosensitivity of a pE194ts vector is incomplete at standard non-permissive temperatures (42 °C), and replication of the plasmid is impaired but not abolished. We report rpsL-based counterselection vectors, with an improved temperature-sensitive replicon (pT181 repC3) that is completely blocked for replication in S. aureus at non-permissive and standard growth temperature (37 °C). We also describe a set of temperature-sensitive vectors that can be cured at standard growth temperature. These vectors provide highly effective tools for rapidly generating allelic replacement mutations and curing expression plasmids, and expand the genetic tool set available for the study of S. aureus.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Allelic exchange, rpsL, Counterselection, Temperature-sensitive, Streptomycin

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen that carries a plethora of virulence factors, including toxins, immunomodulatory factors, and coenzymes that allow it to survive in adverse conditions within a human host. S. aureus pathogenesis is further compounded by the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains. Therefore, knowledge of staphylococcal factors involved in infection, growth, pathology and transmission is important for the understanding of staphylococcal pathobiology.

In recent years, S. aureus genome sequencing projects have led to the generation of a large amount of sequence information. High-throughput methods to identify open reading frames (ORFs) important for S. aureus virulence and survival have implicated a large number of ORFs of unknown function that are of particular interest. The development of complementation vectors (Charpentier et al., 2004) and allelic exchange systems (Arnaud et al., 2004; Bae and Schneewind, 2006) have made S. aureus more amenable to molecular genetic analysis, and this has greatly facilitated studies of its biochemistry, physiology and pathogenicity (Chatterjee et al., 2013; Geiger et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2013; Price-Whelan et al., 2013; Tormo-Mas et al., 2010; Valle et al., 2012). To date, most of the temperature-sensitive allelic exchange vectors developed for S. aureus rely on the pE194ts replicon that was originally developed for use in Bacillus subtilis (Villafane et al., 1987). In S. aureus, the replication of a vector with pE194ts is not blocked, but only severely impaired at 42 °C (see Results), and higher incubation temperature (43 °C) or liquid passaging is often required to reliably lose the vector (Bae and Schneewind, 2006). High incubation temperature can be problematic in S. aureus, as it is one of the primary environmental stresses that have been linked to spontaneous secondary mutations, such as those reported in the sae locus (Sun et al., 2010).

Here, we describe an additional system for allelic replacement in S. aureus, adapted from an rpsL-based counterselection strategy (Ortiz-Martin et al., 2006; Russell and Dahlquist, 1989; Sander et al., 1995; Skorupski and Taylor, 1996). Streptomycin belongs to the aminoglycoside class of antibiotics that inhibit prokaryotic protein synthesis by binding to the small subunit of the ribosome. Bacteria have evolved several resistance mechanisms to streptomycin, and one of them involves common single-step mutations within the rpsL gene coding for ribosomal protein S12 (Funatsu and Wittmann, 1972). However, in merodiploid strains with both wild type and mutant alleles, streptomycin sensitivity is dominant over resistance (Lederberg, 1951). Vectors pJC1202, pJC1600, and pJC1619 carry a wild type copy of the S. aureus rpsL gene (rpsL+), and can be used for counterselection in strains that are streptomycin resistant due to mutations in rpsL (rpsL*). A key feature of these vectors is improved temperature-sensitivity, which is based on a pT181 repC3 replicon that is not only completely blocked for replication at standard non-permissive temperature (42 °C) (Novick et al., 1982), but also at standard growth temperature (37 °C), and permits the entire allelic exchange to be carried out on a series of agar plates by streaking for single colonies at standard growth temperatures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains (TOP 10 or XL1-Blue) were grown on LB agar and LB broth supplemented with ampicillin: 100 µg/ml as needed. S. aureus strains were usually grown on glycerol lactate (Novick, 1991) or tryptic soy (TS) broth or agar supplemented with antibiotics (cadmium chloride: 0.1 mM; chloramphenicol: 10 µg/ml; erythromycin: 5 µg/ml; streptomycin: 300 µg/ml; tetracycline: 5 µg/ml) as needed.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study.

| S. aureus strains | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strain | Genotype or description | Reference |

| RN4220 | Restriction-defective derivative of RN450 | (Kreiswirth et al., 1983) |

| JCSA17 | RN4220 rpsL* | (This work) |

| JCSA133 | JCSA417 Δagr | (This work) |

| JCSA416 | RN0001 rpsL* | (This work) |

| JCSA417 | RN6734 rpsL* | (This work) |

| JCSA418 | RN6390 rpsL* | (This work) |

| JCSA434 | MW2 rpsL* | (This work) |

| JCSA436 | USA300 LAC rpsL* | (This work) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | E. coli cloning vector | (Yanisch-Perron et al., 1985) |

| pCN33 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector | (Charpentier et al., 2004) |

| pCN47 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector | (Charpentier et al., 2004) |

| pCN49 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector | (Charpentier et al., 2004) |

| pRN7145 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector | (Charpentier et al., 2004) |

| pSA0321 | S. aureus temperature sensitive plasmid | (Novick et al., 1982) |

| pI524 | S. aureus natural plasmid | (Novick, 1963) |

| pJC1125 | pJC1079 with pT181 repC3 | (Chen and Novick, 2007) |

| pJC1200 | pUC18 with blaZ promoter cloned | (Chen and Novick, 2007) |

| pJC1201 | pUC18 with rpsL gene cloned | (Chen and Novick, 2007) |

| pJC1202 | pJC1125 cat194, Pbla-rpsL+ | (Chen and Novick, 2007) |

| pJC1204 | pJC1202 with agr::ermC knockout construct | (This work) |

| pJC1306 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector tetM | (Chen et al., 2014b) |

| pJC1600 | pJC1202 ermC, Pbla-rpsL+ | (This work) |

| pJC1601 | pJC1125 ermC | (This work) |

| pJC1619 | pJC1202 tetM, Pbla-rpsL+ | (This work) |

| pJC1945 | pJC1125 tetM | (This work) |

| pJC1983 | pJC1600 with agr::cadCA knockout construct | (This work) |

| Primers | 5′ to 3′ | |

| JCO 134 | CTCATCCCTTCTTCATTAC | (This work) |

| JCO 136 | CCTAGGTGCTGTTCCACGTTTACCATCTAAC | (This work) |

| JCO 176 | GGGCCCAGCTTACTATGCC | (This work) |

| JCO 177 | CTCGAGAATAAACCCTCCG | (This work) |

| JCO 178 | CTCGAGCGTCAATGCGACAATAGTAGCATTG | (This work) |

| JCO 337 | GGTACCTGAAGCGGGCGAGCGAG | (This work) |

| JCO 830 | CTCATATATCAAGCAAAGTGACAGGC | (This work) |

| JCO 831 | GCACATACTGTGTGCATATCTGATC | (This work) |

| JCO 832 | CCGCAGTGCGTTGGATAG | (This work) |

| JCO 833 | GGAGGTGTAGCATGTCTCATTC | (This work) |

2.2. Plasmid construction

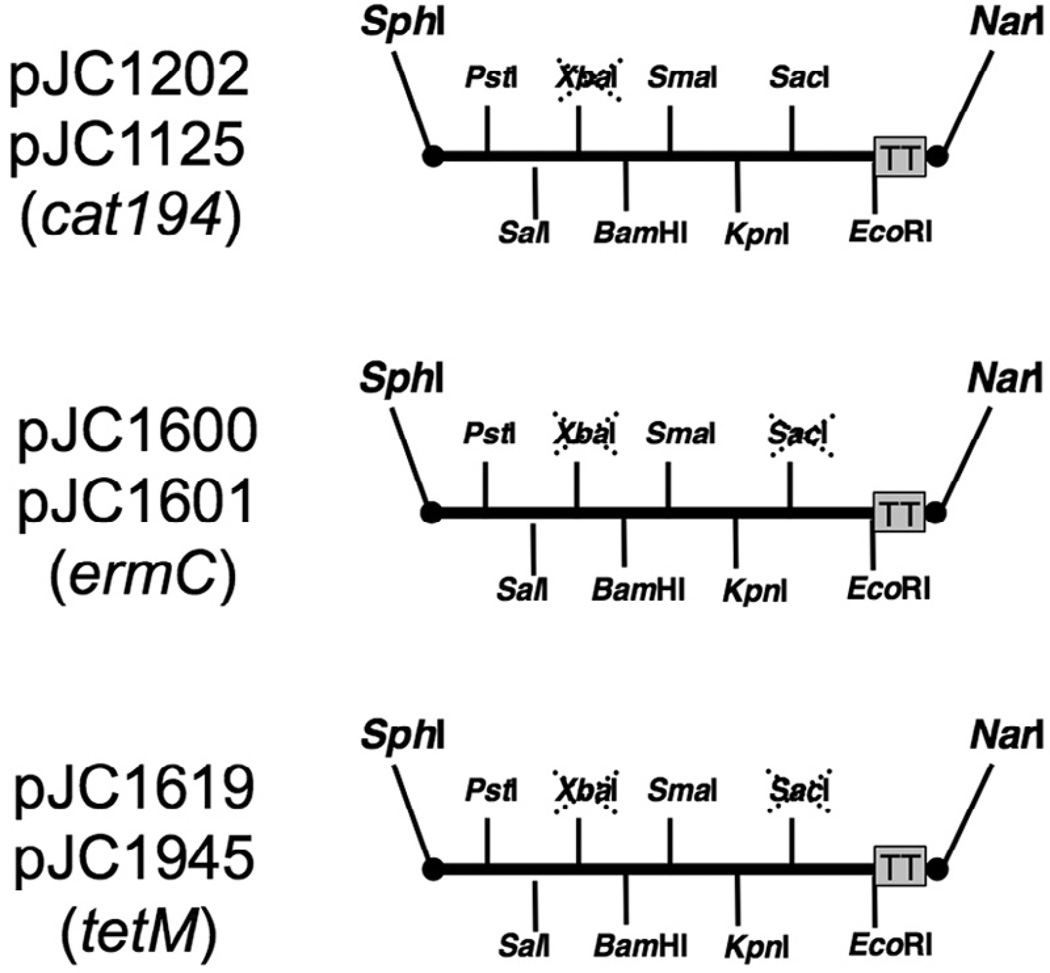

The pT181 repC3 replicon was sequenced with primers JCO 830, JCO 831, JCO 832, and JCO 833. The plasmids (see Table 1) used in this study were constructed by cloning PCR products amplified with oligonucleotide primers purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Clones were sequenced by Macrogen (Rockville, MD). Blunt-ended PCR products were cloned into the HincII site of pUC18. The HpaI fragment from pSA0321, containing the repC3 temperature sensitive replicon, replaced the pT181 replicon in pJC1079 to generate pJC1125. The blaZ promoter was amplified fromS. aureus plasmid, pI524, using primers JCO 176 and JCO 177. The wild type rpsL gene was amplified from strain RN0001 with primers JCO 178 and JCO 136. A 3-way ligation with the pJC1200 ApaI-XhoI fragment and pJC1201 XhoI-AvrII fragments were cloned into pJC1125 to generate pJC1202. The ermC from pCN33was used to replace the cat194 of pJC1202 and pJC1125 to generate pJC1600 and pJC1601, respectively. The tetM from pJC1306 was used to replace the cat194 of pJC1202 and pJC1125 to generate pJC1619 and pJC1945, respectively. The multi-cloning sites of the vectors presented in this study are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Map of multi-cloning sites of the pT181repC3 replicon-based vectors. Vectors pJC1202, pJC1600, and pJC1619 are counterselection vectors for allelic exchange. Vectors pJC1125, pJC1601, and pJC1945 are temperature-sensitive vectors that can be used for expression and complementation.

2.3. Strain construction

To select for streptomycin resistant strains in the rpsL gene, wild type strains were grown to stationary phase and 0.5 ml of culture were plated on streptomycin (300 µg/ml) plates at 37 °C. Spontaneous streptomycin resistant mutants were checked for mutations in rpsL by transformation or transduction with pJC1202, which carries the rpsL+ gene. Strains that are rpsL* carrying pJC1202 are no longer resistant to streptomycin, and will not survive double selection on streptomycin (300 µg/ml) and chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml) plates at 28–32 °C. This method can be used to rapidly generate an rpsL* derivative of any strain, provided it is sensitive to streptomycin at the onset.

2.4. Plasmid stability assay

For liquid stability assays (Chen et al., 2014b), strains were grown overnight on TS agar with selection at 28 °C. Cells were resuspended in TS broth without antibiotics, adjusted to OD600 = 0.5, diluted 10−6 in TS broth without antibiotics, and shaken at 37 °C or 42 °C. Every 2 hours, dilutions were plated on TS agar without selection for single colonies at 28 °C, and plasmid retention was measured by picking 100 colonies from the non-selective plates onto plates with selection at 28 °C.

For agar plate stability assays, strains were grown overnight on TS agar plates with selection at 28 °C. Single colonies were re-streaked onto pre-warmed TS agar without antibiotics and incubated at 28 °C, 32 °C, 37 °C, or 42 °C. Plasmid retention was measured by picking 100 colonies from the non-selective plates onto plates with selection at 28 °C.

2.5. S. aureus allelic exchange

Allelic exchange vectors were first electroporated into RN4220. For pJC1202 or its derivatives, selection medium was TS agar + chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml); for pJC1600 or its derivatives, the selection medium was TS agar + erythromycin (5 µg/ml); and for pJC1619 or its derivatives, GL or TS agar + tetracycline (5 µg/ml). All plates were incubated at 32 °C. Plasmids were moved to a streptomycin-resistant strain of choice by phage transduction as previously described (Chen et al., 2014a; Ubeda et al., 2007) and transductants were patched on fresh plates with the same antibiotic. Alternatively, plasmids can be prepared from RN4220 or E. coli DC10B (Monk et al., 2012) and electroporated into the streptomycin-resistant strain of choice. To select for the first crossover, patched colonies were streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed (37 °C) TS agar + antibiotic plates and incubated at 37 °C. The “antibiotic” here refers to the resistance gene in the cassette used to generate an insertion or deletion. Alternatively, the antibiotic resistance of the vector can be selected, with the exception of pJC1202 derivatives, since cat194 in single copy requires lower concentrations of chloramphenicol (5 µg/ml) and does not provide a clean selection at 37 °C or higher. Subsequently, only colonies with plasmid that had recombined into the chromosome will grow to form normal colonies. Because the plasmid carries the same rpsL gene as the chromosome, integration is possible at the rpsL gene, and several merodiploids were chosen for the second crossover. In order to carry out the second crossover event, integrants were streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed (37 °C) TS agar + antibiotic (resistant gene in the cassette used to generate an insertion or deletion) + streptomycin (300 µg/ml) plates and incubated at 37 °C. Only clones that had excised the plasmid, while retaining the antibiotic resistance gene marking the disrupted gene of interest, should form colonies. At this stage, the allelic exchange was complete. Knockout clones that had undergone the double crossover event should have also lost resistance to the antibiotic marker on the plasmid backbone (chloramphenicol for pJC1202, erythromycin for pJC1600, tetracycline for pJC1619). A phage lysate was then grown on the allelic exchanged strain, and the disrupted gene marker was moved to a fresh genetic background by phage transduction. Finally, we note that markers introduced near the native rpsL gene can result in co-transduction of the rpsL* mutation.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Construction of rpsL-based counterselection and temperature-sensitive complementation vectors

Allelic exchange vectors pJC1202, pJC1600, and pJC1619 carry the wild type rpsL+ gene cloned under a blaZ promoter, allowing rpsL+ to be used as counter-selectable marker for plasmid loss in streptomycin-resistant S. aureus strains, even when the vector is present in single copy in the chromosome. Spontaneous rpsL* derivatives of standard laboratory S. aureus strains that are resistant to streptomycin were generated for this study, and a protocol is described for generating rpsL* derivatives of any S. aureus strain (Material and Methods). The construction of allelic exchange vector pJC1202 was previously described (Chen and Novick, 2007), and also in the Material and Methods. The cat194 gene of plasmid pJC1202 was replaced with ermC or tetM to generate pJC1600 and pJC1619, respectively (Fig. 1). In addition, vectors without the rpsL gene (pJC1125, pJC1601, and pJC1945) are also described here, and can be used for conditional complementation or expression.

3.2. Comparing the temperature sensitivity of the pT181 repC3 and pE194ts replicons

3.2.1. The pT181 repC3 replicon is unstable at standard growth temperature (37 °C)

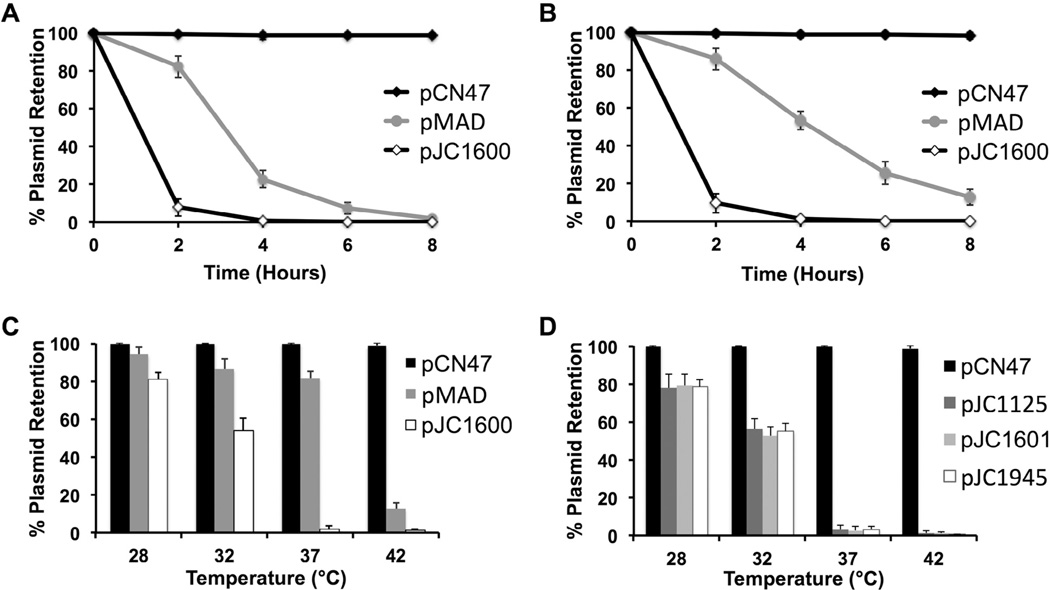

The pT181 repC3 allele was originally isolated as a copy number and replication mutant of the pT181 replicon. This allele exhibited lower copy numbers at permissive temperature and a severe replication defect at non-permissive temperature (Novick et al., 1982). Sequencing of this replicon revealed two point mutations (447A > T and 649C > T) downstream of the pT181 origin of replication in the repC gene, which are predicted to result in two amino acid substitutions (E149D and L217F) in the RepC protein that are likely responsible for the temperature-sensitive phenotype. To determine whether pT181 repC3 is an improved temperature-sensitive replicon (over the standardly used pE194ts replicon), S. aureus strains carrying either pCN47 (wild type pT181), pJC1600 (pT181 repC3), or pMAD (pE194ts) were sub-cultured into TS broth at 42 °C, and the temperature sensitivity of these replicons was measured by testing for plasmid loss during growth without antibiotic selection. These representative plasmids were chosen for comparison because all three are selectable with erythromycin. As expected, pCN47 was highly stable and rarely lost from the population (Fig. 2A). In contrast, pJC1600 and pMAD were highly unstable, and were retained by less than 10% of the cultures by 2 and 6 hours, respectively, showing that pJC1600 is more unstable than pMAD at 42 °C. Moreover, since S. aureus has a typical doubling time of approximately 25–30 minutes (Novick, 1991), the 8% retention observed for pJC1600 at 2 hours (4–5 generations) suggests that pJC1600 replication was inactivated almost immediately following a temperature shift to 42 °C, as it approximates the theoretical retention (6.3%) that is predicted for a non-replicating plasmid at 4 generations.

Fig. 2.

Vectors carrying the pT181 repC3 replicon are unstable at 37 and 42 °C. (A and B) S. aureus RN4220 strains with pCN47 (wild type pT181), pMAD (pE194ts), or pJC1600 (pT181 repC3) were grown in TS broth in the absence of selection at 42 °C (A) or 37 °C (B). Cells were plated at regular intervals on TS agar for single colonies at permissive temperature without selection. (C and D) S. aureus RN4220 strains with allelic exchange vectors (C) or temperature-sensitive vectors pJC1125, pJC1601, or pJC1945 (D) were streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed TS agar and incubated at various temperatures without selection. (A–D) Plasmid retention was measured by picking 100 colonies from the non-selective plates onto plates with selection at permissive temperature. T0 was set to 100% for all samples because all strains were grown with selection at 28 °C prior to temperature shift. Values are means ± SD (n = 3 independent samples).

Since pJC1600 was so highly unstable at 42 °C, we next determined plasmid instability at standard laboratory growth temperature (37 °C). As shown in Fig. 2B, pMAD was still unstable, but was lost at a slower rate than that observed at 42 °C, and never reached below 10% retention, even at 8 hours. In contrast, the rapid loss of pJC1600 at 37 °C was nearly indistinguishable from that of 42 °C, indicating that pT181 repC3 is an effective temperature-sensitive replicon at 37 °C.

3.2.2. Curing pT181 repC3 replicons from S. aureus strains on agar plates at standard growth temperature (37 °C)

In S. aureus, allelic exchange protocols involving vectors carrying the pE194ts replicon require liquid passaging at high incubation temperatures for plasmid curing (Bae and Schneewind, 2006). To determine the efficiency of plasmid curing on agar plates, S. aureus strains carrying the same plasmids above were streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed TS agar plates and the temperature sensitivity of these replicons was measured by testing for plasmid loss during growth without antibiotic selection at various temperatures. As expected, the wild type pT181 replicon was highly stable across all temperatures (Fig. 2C). The pE194ts replicon-carrying pMAD was mostly stable up to 37 °C, and was rapidly lost at 42 °C; however, even at 42 °C, roughly 13% still retained the plasmid, which explains why liquid passaging is often required to reliably cure vectors carrying the pE194ts replicon. In contrast, the pT181 repC3 replicon-carrying pJC1600 was efficiently cured and rarely observed in the population at 37 and 42 °C. Parallel results were observed for the 3 temperature-sensitive vectors that also carry the pT181 repC3 replicon (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results show that vectors carrying the pT181 repC3 replicon can be efficiently cured from S. aureus strains by passaging on agar plates at 37 °C, and suggest that allelic exchange can be performed under these same temperature conditions.

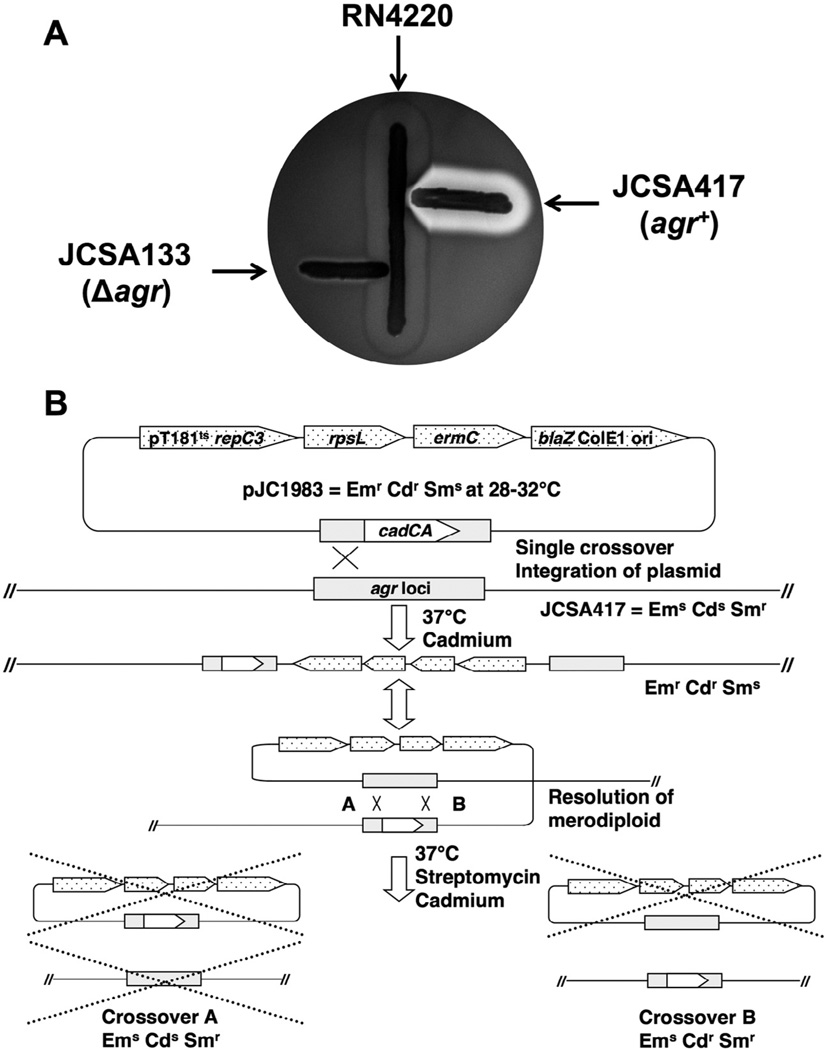

3.3. Allelic exchange in S. aureus

Next we tested the counterselection allelic exchange vector pJC1202 by inactivating the agr locus (Novick and Geisinger, 2008; Peng et al., 1988) using standard non-permissive temperature (42 °C). Plasmid pJC1204 (agr::ermC knockout construct) was introduced by electroporation into S. aureus strain RN4220, and the transformants were selected at 32 °C on TS agar containing chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml). Plasmid pJC1204 was then moved by phage transduction to a streptomycin-resistant derivative of an agr wild type strain, and the colonies were patched onto the same medium and incubated overnight at 32 °C. In the first step, a patched colony was picked and streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed (42 °C) TS agar + erythromycin (5 µg/ml) plates and incubated overnight at 42 °C. The resulting colonies represent integrants of pJC1204 into the chromosome by a single crossover event. To select for the second crossover, merodiploids were streaked for single colonies on pre-warmed (42 °C) TS agar + erythromycin (5 µg/ml) + streptomycin (300 µg/ml) plates and incubated overnight at 42 °C. The colonies thus obtained had presumably excised the plasmid, but retained the erythromycin resistance, and hence, represented completion of the allelic exchange event. Of the streptomycin-resistant, erythromycin-resistant and chloramphenicol-sensitive colonies, all (20 out of 20) had the expected deletion and replacement of the agr locus, as confirmed by PCR analysis with oligonucleotides JCO134 and JCO339. Furthermore, we evaluated the functionality of the agr locus in wild type and agr deletion-mutant strains for the production of α- and δ-hemolysins. On sheep blood agar plates (Adhikari et al., 2007), the agr wild type strain produced both α- and δ-hemolysins while the agr deletion mutant did not produce either, confirming the agr-null phenotype (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

(A) Allelic replacement with pJC1204 generates a deletion in the agr locus. Hemolytic activities of the wild type strain and its Δagr derivative were confirmed on sheep blood agar. The wild type (JCSA 417) and agr deletion mutant (JCSA133) were streaked at right angles to RN4220 and the plate incubated overnight. The wild type strain produces α-hemolysin and δ-hemolysin, making a characteristic clearing zone caused by lysis of red blood cells in the agar plate, and V-shaped zone at intersection with RN4220. (B) Schematic representation of an allelic exchange of the agr locus using plasmid pJC1983, a derivative of the allelic exchange vector pJC1600.

Next we determined whether the system could efficiently inactivate agr at 37 °C, by using plasmid pJC1983 (agr::cadCA knockout construct) to test the exchange vector pJC1600 (Fig. 3B). First we performed the counterselection step on 3 independent merodiploids, without selection for the cadmium insertion, to test for the efficiency of generating mutations without a selectable marker, and observed that 100% of the recombinants had excised the vector (Table 2), suggesting that counterselection was highly efficient and that spontaneous suppressor mutations for streptomycin resistance, such as those that would inactivate the rpsL+ counterselection cassette, are rare and not detectable in this sample size. Of the streptomycin resistant recombinants, roughly 62% showed an agr-null phenotype, which is higher than that which is expected by chance; however, we note that the efficiency of excising the wild type DNA, as opposed to excising the deletion construct, is largely determined by the particular stretches of DNA that support homologous recombination to resolve the merodiploid, and the frequency observed here is likely specific to this agr deletion construct, and should be expected to vary with other constructs. Next we performed counterselection on the same merodiploids, but with marker selection, and observed that 100% of the recombinants had excised the vector, and roughly 99% showed the agr-null phenotype. Taken together, these results show that rpsL-based counterselection is highly efficient in S. aureus for the selection of recombinants that have excised and lost the exchange vector, and when combined with the pT181 repC3 temperature-sensitive replicon, permits efficient allelic exchange at standard growth temperature on agar plates.

Table 2.

Allelic exchange of the agr locus by counterselection at standard growth temperature.

| % Plasmid Retention |

% agr-null | |

|---|---|---|

| Counterselection | 0 | 62.3 ± 8.1 |

| Counterselection + Selection | 0 | 98.7 ± 1.5 |

JCSA417 merodiploids of pJC1983 were streaked on pre-warmed TS agar plates containing streptomycin (300 µg/ml) for “counterselection” or cadmium chloride (10 µg/ml) + streptomycin (300 µg/ml) for “counterselection + selection” and incubated at 37 °C. Plasmid retention was measured by picking 100 colonies from the non-selective plates onto plates with selection at permissive temperature, and the agr-null phenotype was determined by patching colonies onto sheep blood agar plates at 37 °C for hemolytic activity. Values are means ± SD (n = 3 independent samples).

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have described improved temperature-sensitive vectors for allelic exchange and expression in S. aureus. The advantages of these allelic exchange vectors include: (i) An improved temperature-sensitive replicon; (ii) No broth culture is required and no serial dilutions are involved; (iii) All of the experiments can be performed on agar plates, which reduces the time and effort to generate knockouts; (iv) The allelic exchange is highly efficient; (v) The allelic exchange can be performed at 37 °C. The development of the pT181 repC3 replicon adds to the available replicons that are temperature-sensitive at standard growth temperatures (Monk et al., 2012), and the adaptation of rpsL-based allelic exchange adds to the growing list of counterselection systems that have been developed or adapted for S. aureus (Bae and Schneewind, 2006; Pagels et al., 2010; Redder and Linder, 2012). Taken together, these vectors expand the genetic tool set available for the study of S. aureus physiology and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01AI022159 to RPN and JRP, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- Adhikari RP, et al. A nonsense mutation in agrA accounts for the defect in agr expression and the avirulence of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4 traP::kan. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:4534–4540. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00679-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud M, et al. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae T, Schneewind O. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid. 2006;55:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E, et al. Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6076–6085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6076-6085.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee SS, et al. Essential Staphylococcus aureus toxin export system. Nat. Med. 2013;19:364–367. doi: 10.1038/nm.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Novick RP. svrA, a multi-drug exporter, does not control agr. Microbiology. 2007;153:1604–1608. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, et al. Intra- and inter-generic transfer of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence genes by cos phages. ISME J. 2014a doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, et al. Single-copy vectors for integration at the SaPI1 attachment site for Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid. 2014b;76C:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu G, Wittmann HG. Ribosomal proteins. 33. Location of amino-acid replacements in protein S12 isolated from Escherichia coli mutants resistant to streptomycin. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;68:547–550. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, et al. The stringent response of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on survival after phagocytosis through the induction of intracellular PSMs expression. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003016. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiswirth BN, et al. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederberg J. Streptomycin resistance: a genetically recessive mutation. J. Bacteriol. 1951;61:549–550. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.5.549-550.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk IR, et al. Transforming the untransformable: application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. MBio. 2012;3 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00277-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP. Analysis by transduction of mutations affecting penicillinase formation in Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1963;33:121–136. doi: 10.1099/00221287-33-1-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:587–636. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04029-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Geisinger E. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008;42:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, et al. Coding sequence for the pT181 repC product: a plasmid-coded protein uniquely required for replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1982;79:4108–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Martin I, et al. Suicide vectors for antibiotic marker exchange and rapid generation of multiple knockout mutants by allelic exchange in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2006;67:395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagels M, et al. Redox sensing by a Rex-family repressor is involved in the regulation of anaerobic gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;76:1142–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HL, et al. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AR, et al. The Holliday junction resolvase RecU is required for chromosome segregation and DNA damage repair in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price-Whelan A, et al. Transcriptional profiling of Staphylococcus aureus during growth in 2MNaCl leads to clarification of physiological roles for Kdp and Ktr K + uptake systems. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00407-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redder P, Linder P. New range of vectors with a stringent 5-fluoroorotic acid-based counterselection system for generating mutants by allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:3846–3854. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00202-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CB, Dahlquist FW. Exchange of chromosomal and plasmid alleles in Escherichia coli by selection for loss of a dominant antibiotic sensitivity marker. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:2614–2618. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2614-2618.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander P, et al. rpsL+: a dominant selectable marker for gene replacement in mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupski K, Taylor RK. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene. 1996;169:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, et al. Aureusimines in Staphylococcus aureus are not involved in virulence. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormo-Mas MA, et al. Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature. 2010;465:779–782. doi: 10.1038/nature09065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C, et al. SaPI operon I is required for SaPI packaging and is controlled by LexA. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle J, et al. Bap, a biofilm matrix protein of Staphylococcus aureus prevents cellular internalization through binding to GP96 host receptor. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002843. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafane R, et al. Replication control genes of plasmid pE194. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:4822–4829. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4822-4829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanisch-Perron C, et al. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]