Abstract

Objective

The indolent nature and expression of progesterone receptor (PR), a well-known estrogen-induced gene, in a subset of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs), raise the possibility of hormonal regulation in these tumors.

Methods

Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen receptors (ER) α and β and mRNA expression of estrogen-induced genes (PR, EIG121, IGF-1, IGF-1R, sFRP1, and sFRP4) by qRT-PCR were examined in 131 WHO G1-G2 PanNETs and correlated expression with clinicopathologic features.

Results

39 PanNETs (30%) showed high positive ERβ staining and 87 cases (66%) had low positive ERβ staining; only 5 cases (4%) had no nuclear staining. PanNETs with small size (P=.02), low WHO grade (P=.02) and low AJCC stage (P=.006) more frequently showed high positive ERβ staining. Among estrogen-induced genes studied, PanNETs had significantly higher expression of PR, EIG121, IGF-1, sFRP1, and sFRP4 compared to normal pancreas, independent of age or gender. High positive ERβ staining was associated with increased expression of PR (P < .001) and EIG121 (P=.02).

Conclusions

Our study showed that PanNETs with favorable prognostic features have higher ERβ expression, which is associated with upregulated PR and EIG121 mRNA expression. Estrogen regulation in PanNETs could potentially help in risk stratification and provide a rational target for novel treatment strategies.

Keywords: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, ERβ, estrogen-induced genes

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms are rare, representing approximately 3% of primary pancreatic neoplasms1, although their incidence has risen sharply in the United States, increasing more than 100% over the past three decades2. They have a highly variable clinical behavior, ranging from indolent to highly aggressive. Up to 61% of patients present with distant metastases and only 26% of whom undergo surgical resection3. The poor survival in some patients is due, in part, to the limited treatment options for these patients4. Platinum-based chemotherapy with radiation and surgery may be a treatment option for patients with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (HGNEC), however, studies suggest that these tumors are clinically and molecularly more similar to small cell carcinomas of other sites and distinct from well-differentiated [low (G1) and intermediate grade (G2)]5 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs)6–8. For patients with PanNETs, surgery remains the primary treatment option. Recently, two new targeted therapies have been recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients with advanced PanNETs. Sunitinib (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and everolimus (mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor) have been shown in phase III trials to improve progression-free survival compared to placebo4. Despite these advances, treatment of patients with advanced PanNET remains unclear9. One important challenge in therapy development for PanNETs is that the mechanisms of tumorigenesis are not clear.

The indolent nature and the expression of progesterone receptor (PR), a well-known estrogen-induced gene, in some PanNETs raise the question of possible hormonal regulation in these neoplasms. Substantial subsets of prostate, breast, and endometrial carcinoma are similarly indolent; these subsets are characterized by hormonal dependence. For prostatic carcinoma, it is well-known that metastasis and aggressive clinical course are tightly linked to androgen independence. Androgen-independent tumors typically have high-grade neuroendocrine features and patients survive < 1 year10. It is well-documented that in carcinomas of the breast and endometrium, estrogen regulation has played a pivotal role in tumor subclassification, risk assessment and treatment strategies. Estrogen receptor (ER) status has remained one of the most important molecular markers in the management of patients with breast cancer, as it provides both prognostic and predictive value11. In endometrial carcinoma, classification of tumors into type I and type II categories has been traditionally based, in part, on ER status, namely, most type I tumors are ER positive while most type II tumors are ER negative12. Moreover, quantitative assessment of expression of genes induced by estrogen, including IGF-1, IGF-1R, RALDH2, sFRP1, sFRP4, and EIG12113–15, has been shown to provide important prognostic data for endometrial carcinoma14. Specifically, high expression of estrogen-induced genes in endometrial carcinoma is associated with endometrioid histotype and significantly prolonged recurrence-free survival14.

The role of estrogen regulation in PanNETs is unclear, and studies on ER expression are conflicting with reported rates of 0–13% ER alpha positivity by immunohistochemistry16, 17 and up to 40% positivity in insulinomas18. However, previous studies have shown that PR, is important in islet cell function19–22 and has prognostic significance in PanNETs12, 17, 23. Loss of PR immunohistochemical expression is associated with presence of metastasis, lymphovascular invasion and involvement of adjacent organs17. Moreover, two previous reports have shown that loss of PR expression correlated with shorter disease-free12 and overall23 survival by univariate analysis.

Given these previous findings, we hypothesized that low and intermediate grade PanNETs would express the hormone receptors ERα and/or ERβ and, thus, estrogen-induced genes. Results from this study can potentially provide insight into hormonal regulation and novel hormonal therapeutic targets in PanNETs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and tissue samples

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded PanNET tumor sections from routinely processed partial pancreatectomy specimens (including pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy and enucleation) and/or resected metastases were retrieved from the Surgical Pathology files at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, between 2000 – 2010. A total of 131 PanNETs, low grade (G1) and intermediate grade (G2) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria5, were included. High-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas were specifically excluded, as these tumors have different clinical behavior and molecular profile from G1 and G2 PanNETs7. Clinical data were extracted from patient medical records. Functionality was defined as documented increase in blood hormone levels and concomitant constellation of typical signs and symptoms, as defined by the WHO 5. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were reviewed in all cases, as well as the corresponding surgical pathology reports. The pathologic tumor stage was determined according to the pancreatic tumor staging system based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual, 7th edition criteria24. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry were initially performed on tissue microarrays (TMA) of 80 PanNETs and validated using 5 µm-thick formalin-fixed (10% buffered formalin), paraffin-embedded whole tissue sections of 131 PanNETs. Standard avidin-biotin complex (ABC) technique was employed using antibodies to Ki-67 (clone MIB-1, 1:100; DAKO, Capinteria, CA), ERα (clone 6F11, 1:35; Novocastra), and ERβ (clone EMR02, 1:100, Leica microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Quantification of the proliferative index by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry was performed using computer-assisted image analysis with Aperio ImageScope Version 11.2.0.780 (copyright © Aperio Technologies, Inc. 2003 – 2012) and counting at least 2,000 tumor nuclei in the areas with the highest percentage of nuclear staining (“hotspots”), as per the 2010 WHO guidelines5. PanNETs were categorized as low grade (G1, 0−2.9% Ki-67 labeling) or intermediate grade (G2, 3−20% Ki-67 labeling). High-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas, those with greater than 20% Ki-67 labeling, were excluded. Nuclear staining for ERα in greater than or equal to 1% of the whole tumor section was considered positive, while those cases with less than 1% were considered negative, a cut-off used in breast cancer25, 26. Nuclear staining for ERβ was evaluated using computer-assisted image analysis with Aperio ImageScope Version 11.2.0.780 (copyright © Aperio Technologies, Inc. 2003 – 2012) and evaluating a representative area, attempting to encompass most of the tumor section. ERβ was scored using the Allred scoring system used in breast carcinoma26, 27. Briefly, the proportion of positively stained tumor nuclei (0, none; 1, < 1/100; 2, 1/100 to 1/10; 3, 1/10 to 1/3; 4, 1/3 to 2/3; and 5, > 2/3) and intensity of the majority of tumor cells (0, none; 1, weak; 2, intermediate; and 3, strong) were added to obtain a total score, ranging from 0 to 8. ERβ immunohistochemical staining was then categorized as high positive (Allred scores = 7−8), low positive (Allred scores = 3−6) and negative (Allred score = 0).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and real-time quantitative PCR

H&E stained sections of PanNET from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were microscopically analyzed by a gastrointestinal pathologist (JSE) to confirm the presence of low-intermediate grade tumor. Forty-one cases had sufficient normal pancreatic tissue that was used as control. Briefly, twenty 10-µm sections were cut from each paraffin block and then deparaffinized in xylene. T&C Lysis solution (Master Pure RNA Purification Kit, catalogue number MCR 85102, Madison, WI) with proteinase K was used for tissue digestion. RNA was extracted using the MasterPure Reagent Kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI). The real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) assays were performed using the 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Probe-based real-time quantitative assays were initially developed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) based on sequences from Genbank. The sequences for qRT-PCR analyses of the estrogen-induced genes PR, EIG121, IGF-I, IGF-IR, sFRP1, and sFRP4 are listed in Table 1. Each qRT-PCR experiment was performed in duplicate using assay-specific sDNAs (synthetic amplicon oligonucleotides, Biosource, Camarillo, CA) serially diluted in 10-fold decrements to obtain a standard curve covering a 5-log range in template concentration. A linear relationship between the threshold cycle (Ct) and the log of the starting sDNA copy number was established (correlation coefficient > 0.99) and used to construct a standard curve. The copy number for each transcript assayed was interpolated from the standard curve by the ABI SDS software. The final transcript values were normalized to 18S rRNA and were presented as ratios of gene transcript/molecules of 18S rRNA. We used 18S rRNA as a normalizer, because levels of 18S rRNA do not fluctuate significantly over time or with exposure to hormones.

Table 1.

Sequences for real-time quantitative PCR assays

| Transcripts | Sequences | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | (535+) GAGGGAGCCTGAGAAACGG (602−) GTCGGGAGTGGGTAATTTGC (555+) FAM-TACCACATCCAAGGAAGGCAGCAGG |

M10098 |

| PR | 2689(+) GAGCACTGGATGCTGTTGCT 2754(−) GGCTTAGGGCTTGGCTTTC 2710(+) FAM-TCCCACAGCCATTGGGCGTTC |

NM_000926 |

| EIG121 | 3074(+) CTTGCATAGCACCTTTGCAAG 3135(−) CAGTGGGTGTTGCAGGATG 3096(+) FAM-CTGCGGCGATT TGGGTGCC |

NM_020775 |

| IGF-1 | 146(+)GCAATGGGAAAAATCAGCAG 237(−)GAGGAGGACATGGTGTGCA 217(−)FAM-CTTCACCTTCAAGAAATCACAAAAGCAGCA-BHQ1 |

M26544 |

| IGF-1R | 163(+) CGCAACGACTATCAGCAGCT 238(−) AGATGAGCAGGATGTGGAGGT 189(+) FAM-CCTGGAGAACTGCACGGTGATCGA-BHQ1 |

NM_000875 |

| sFRP1 | 720(+)GAGCCGGTCATGCAGTTCT 786()CCTCCGGGAACTTGTCACA 740(+)FAM-CGGCTTCTACTGGCCCGAGATCG-BHQ1 |

NM_003012 |

| sFRP4 | 1175(+)GCGCACCAGTCGTAGTAATCC 1246()TTCTTGGGACTGGCTGGTT 1202(+)FAM-ACCAAAGGGAAAGCCTCCTGCTCC-BHQ1 |

AF026692 |

Statistical Methods

Associations between ERβ staining category and clinicopathologic categorical data were determined using Fisher’s exact test. Associations between estrogen-induced gene mRNA expression and continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ), and categorical variables using either Wilcoxon rank sum test (those with two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis test (those with three groups). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 for Windows (Copyright © 1989, 2012 by IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic characteristics

Patients’ clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Mean age was 56 years (range: 18 – 79 years). The female to male ratio was 1:1.6. Twenty females were of pre-menopausal age (< 50 years old) while 30 females were of post-menopausal age (≥ 50 years old). Eleven patients (8%) had associated multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1 (MEN1). Twenty-two (17%) PanNETs were functional, including 14 insulinomas, 5 gastrinomas and 3 glucagonomas. Mean tumor size was 4.5 cm (range: 0.7 – 20 cm). According to the WHO classification standards5, 55% (72 cases) were G1 PanNETs and 45% (59 cases) were G2 PanNETs. Based on the AJCC (7th edition) staging manual, 35 patients (27%) had stage I disease, 59 patients (45%) had stage II disease and 37 patients (28%) had stage IV disease. No patient had stage III disease, as those patients would not be surgical candidates. Liver was the most common site of distant metastasis at presentation (29 patients, 78%).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of 131 patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean=56 years (range 18–79 years) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 50 (38) |

| <50 years old | 20 (15) |

| ≥50 years old | 30 (23) |

| Male | 81 (62) |

| Associated syndrome | |

| MEN1 | 11 (8) |

| Othera | 1 (1) |

| Functional tumors | 22 (17) |

| Tumor size | |

| Mean=4.5 cm (range 0.7–20 cm) | |

| WHO grade | |

| Low (G1) | 72 (55) |

| Intermediate (G2) | 59 (45) |

| AJCC stage | |

| IA | 22 (17) |

| IB | 13 (10) |

| IIA | 26 (20) |

| IIB | 33 (25) |

| III | 0 (0) |

| IV | 37 (28) |

Abbreviation: MEN1, Multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 1.

Other, tuberous sclerosis.

ERα and ERβ immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for ERα was first assessed in a subset of PanNETs using TMAs (n=80). None of these had any detectable ER nuclear staining, so additional studies with ERα were not pursued. ERβ immunohistochemical staining was present in the majority of PanNETs. We, next, investigated ERβ protein expression by immunohistochemistry in 131 PanNETs using whole tissue sections. The majority of PanNETs (96%) exhibited nuclear ERβ. In these tumors, ERβ immunostaining was typically stronger than the adjacent normal pancreatic acini, ducts and islets of Langerhans (Figures 1A-B). By Allred scoring, ERβ staining was as follows: Allred score = 8 (18 cases), 7 (21 cases), 6 (50 cases), 5 (23 cases), 4 (10 cases), 3 (4 cases), and 0 (5 cases).

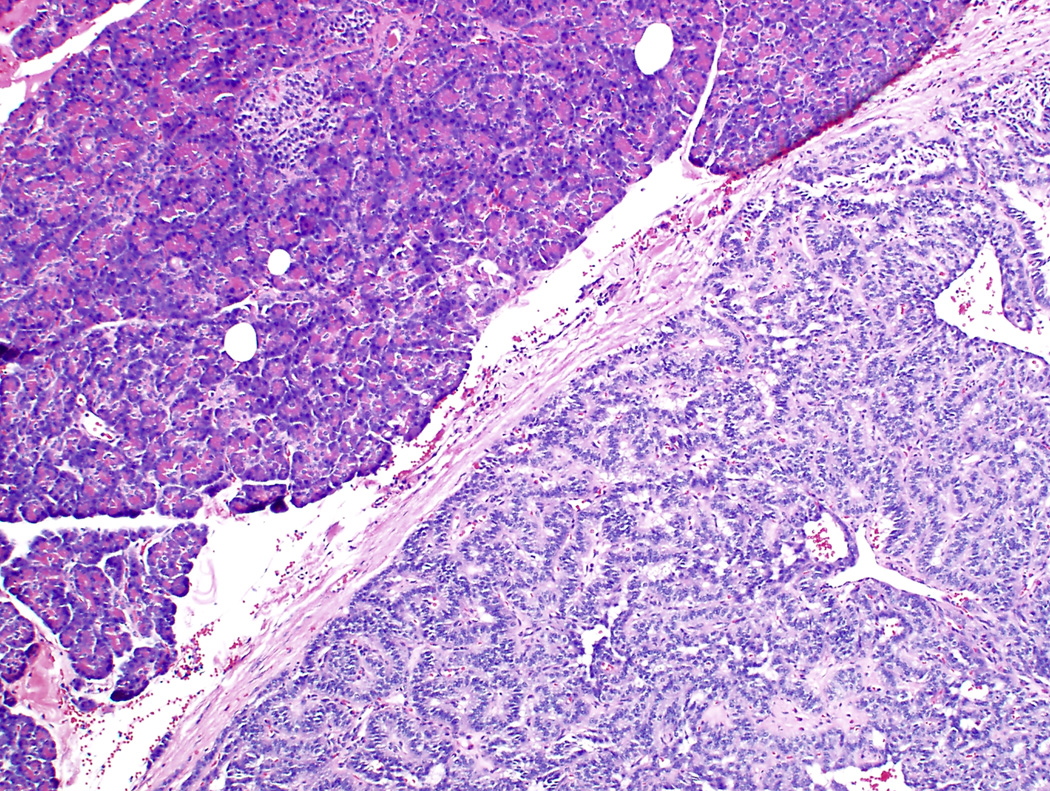

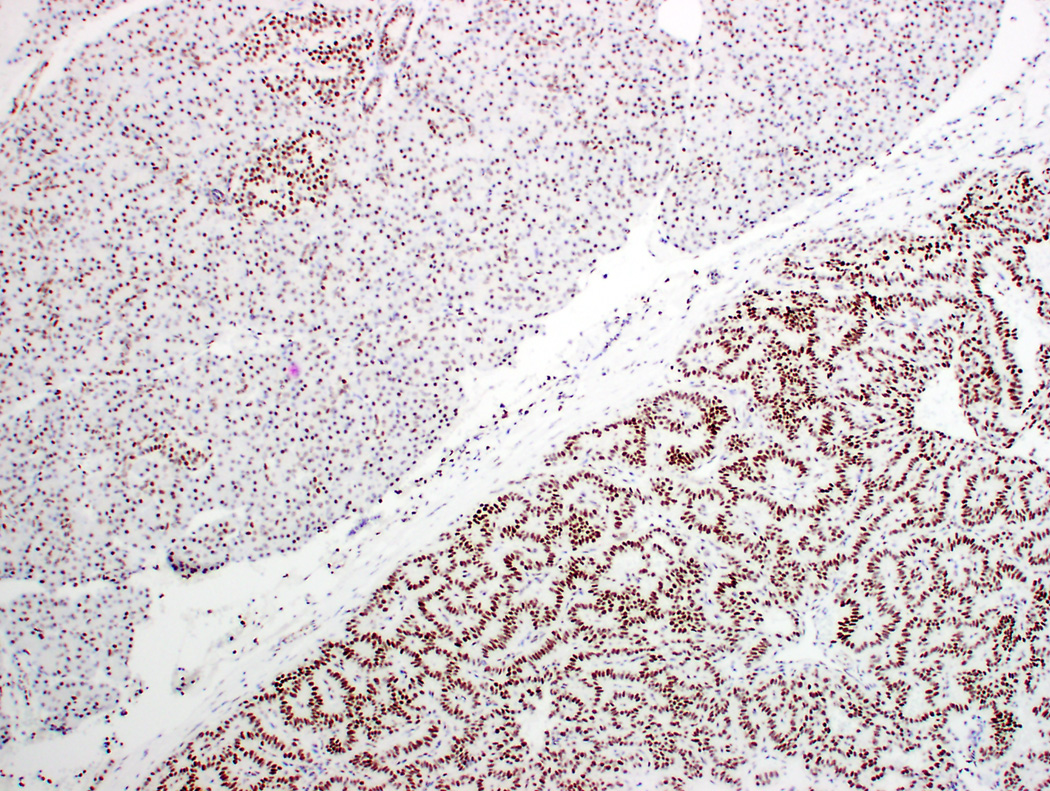

Figure 1.

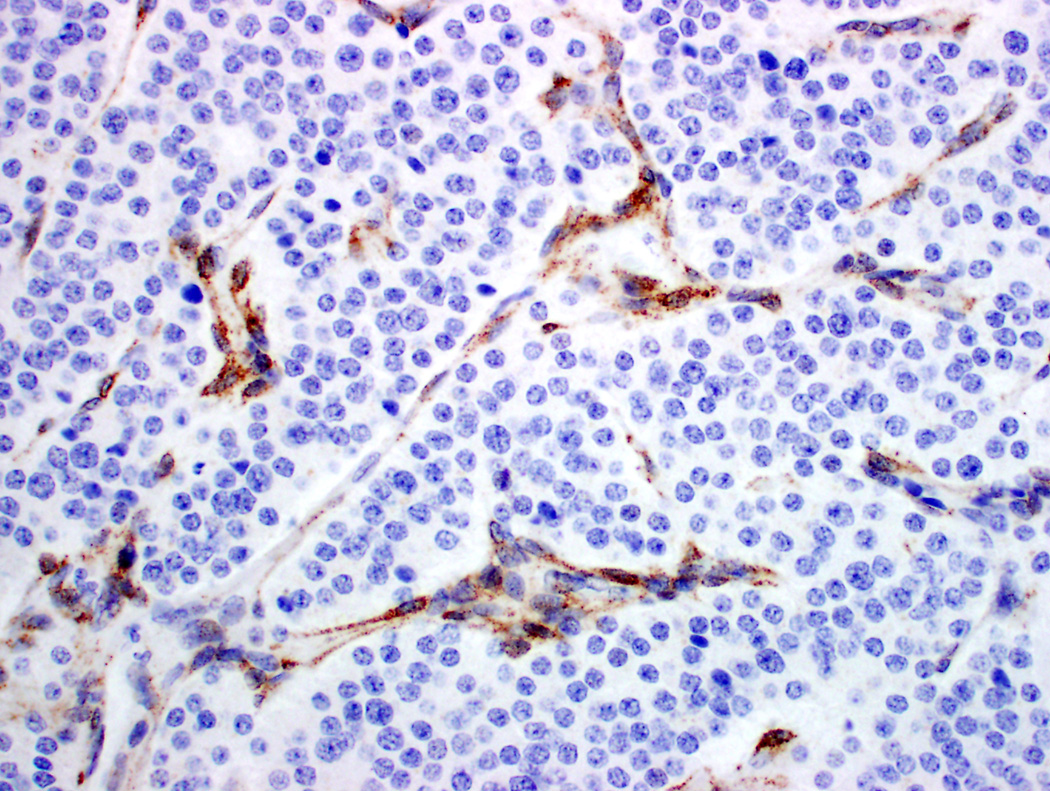

Differential expression of estrogen receptor (ER) β in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNET). A-B PanNET exhibiting strong, diffuse staining for ER β (A: H&E ×100; B: ERβ ×100). ERβ staining was also seen in acinar cells, duct epithelium and islets of Langerhans (A-B, top left). C. PanNET exhibiting no nuclear staining for ERβ (×400). There is staining of stromal cells, which served as internal positive control.

Among 131 PanNETs, 39 (30%) showed high levels of ERβ staining (high positive, Figure 1A-B). Low levels of ERβ staining were seen in 87 (66%) cases (low positive). Five cases (4%) had no nuclear ERβ staining (negative, Figures 1C-D). Correlation with ERβ immunohistochemistry and clinicopathologic features are summarized in Table 3. ERβ staining correlated with tumor size (P=.02), WHO grade (P=.02), and AJCC stage (P=.006). No significant correlation between ERβ immunohistochemical staining and age, including reproductive age, gender, functional tumors, and MEN1 syndrome, were seen.

Table 3.

Correlation between estrogen receptor (ER)β and clinicopathologic parameters in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

| Characteristics (%) | ERβ Category | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n=5) | Low (n=87) | High (n=39) | ||

| Median age (range) | 56 y (49–63) | 54 y (22–79) | 60 y (18–76) | 0.41 |

| Median size (range) | 5.0 cm (2.0 – 8.0) | 4.0 cm (1.1 – 15.0) | 2.6 (0.7 – 20.0) | 0.02 |

| Functionality | 0.23 | |||

| Non-functional | 4 (4) | 76 (70) | 29 (26) | |

| Insulinoma | 0 (0) | 7 (50) | 7 (50) | |

| Non-insulinoma | 1 (13) | 4 (50) | 3 (37) | |

| MEN1 | 1 (9) | 5 (45) | 5 (45) | 0.26 |

| WHO grade | 0.02 | |||

| Low (G1) | 5 (7) | 41 (57) | 26 (36) | |

| Intermediate (G2) | 0 (0) | 46 (78) | 13 (22) | |

| AJCC Stage | 0.006 | |||

| I-IIA | 1 (2) | 34 (55) | 26 (43) | |

| IIB | 3 (9) | 21 (64) | 9 (27) | |

| IV | 1 (3) | 32 (86) | 4 (11) | |

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer

mRNA expression of estrogen-induced genes

Given that the majority of PanNETs had immunohistochemical expression of ERβ, we next wanted to determine whether PanNETs expressed genes known to be induced by estrogen. PanNETs showed increased mRNA expression of PR, EIG121, IGF-1, sFRP1 and sFRP4, compared to normal pancreas. Expression of these genes was independent of age, including reproductive age, and gender (Table 4). Of note, there was a 10-fold increase in EIG121 mRNA expression compared to other estrogen-induced genes, suggesting that EIG121 may be a dominant estrogen regulated gene in PanNETs.

Table 4.

Correlation between estrogen-induced genes and ERβ immunohistochemistry in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

| Characteristics | N | Median Estrogen-Induced Genes (mRNA/18S rRNA) ×104 (range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | EIG121 | IGF-1 | IGF-1R | sFRP1 | sFRP4 | ||

| ERβ Allred score (ρ) | 131 | 0.39 | 0.30 | −0.14 | 0.17 | −0.14 | −0.10 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.28 | |

| ERβ Category* | |||||||

| Negative | 5 | 17 (4.9 – 38) | 230 (71 – 640) | 1.9 (1.0 – 23) | 16 (9.6 – 74) | 7.9 (1.0 – 16) | 34 (2.0 – 320) |

| Low | 87 | 23 (0 – 450) | 350 (9.4 – 1800) | 1.6 (0 – 14) | 17 (0 – 130) | 6.6 (0.2 – 210) | 22 (0.1 – 540) |

| High | 39 | 57 (12 – 540) | 490 (79 – 1700) | 1.2 (0.1 – 11) | 32 (2.6 – 230) | 4.0 (0.3 – 106) | 17 (0.2 – 280) |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.39 | |

ERβ category: negative = Allred scrore 0, low = Allred score 3–6, high = Allred score 7–9.

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; EIG121, estrogen-induced gene – 121; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; sFRP, secreted frizzled-related protein; ρ, Spearman correlation coefficient.

We, then, analyzed the association between ERβ immunohistochemical staining and expression of the estrogen-induced genes (Table 4). High ERβ expression was associated with increased expression of PR and EIG121 mRNA expression. These results suggest that of the genes examined in this study, expression of PR and EIG121 may be the most tightly linked to ERβ protein expression. Among those associated with ERβ immunohistochemical staining, increased PR mRNA expression was seen in tumors with low grade (P=.03), and low stage (P=.003), and increased EIG121 mRNA expression was seen in low stage (P=.02), but did not correlate with WHO grade. Correlation between mRNA expression and clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation between estrogen-induced genes and clinicopathologic parameters in normal pancreas and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

| Characteristics | N | Median Estrogen-Induced Genes (mRNA/18S rRNA) ×104 (range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | EIG121 | IGF-1 | IGF-1R | sFRP1 | sFRP4 | ||

| Normal | 41 | 2.2 (0.6 – 14) | 110 (41 – 230) | 0.8 (0.2 – 18) | 22 (8 – 45) | 1.3 (0.3 – 9) | 1.2 (0.1 – 595) |

| Tumor | 131 | 32 (0 – 540) | 380 (9.4 – 1800) | 1.5 (0 – 23) | 20 (0 – 230) | 6.2 (0.2 – 210) | 20 (0.1 – 540) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.84 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Age (ρ) | 131 | .05 | .05 | .02 | .02 | .06 | .03 |

| P value | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.71 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female <50 years | 20 | 28 (3.4 – 140) | 420 (82 – 1800) | 1.7 (0.3 – 10) | 18 (3.2 – 73) | 6.8 (0.4 – 110) | 13 (0.2 – 360) |

| Female ≥50 years | 30 | 34 (1.5 – 450) | 460 (40 – 1400) | 1.1 (0.1 – 11) | 21 (2.5 – 200) | 7.2 (0.2 – 39) | 17 (0.2 – 240) |

| Male | 81 | 31 (0 – 540) | 310 (9.4 – 1700) | 1.5 (0 – 23) | 20 (0 – 230) | 5.4 (0.2 – 210) | 20 (0.1 – 540) |

| P value | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.97 | |

| Tumor size (ρ) | 131 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.21 | −0.18 | 0.23 | −0.26 |

| P value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.002 | |

| WHO grade | |||||||

| Low (G1) | 72 | 43 (1.6 – 350) | 360 (9.3 – 1800) | 1.2 (0.1 – 23) | 25 (3.5 – 230) | 4.3 (0.2 – 110) | 14 (0.2 – 340) |

| Intermediate (G2) | 59 | 26 (0 – 540) | 400 (40 – 1300) | 1.7 (0 – 14) | 15 (0 – 130) | 8.6 (0.2 – 210) | 30 (0.1 – 540) |

| P value | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.24 | |

| AJCC Stage | |||||||

| IA – IIA | 61 | 44 (1.6 – 350) | 390 (9.4 – 1700) | 1.5 (0.1 – 11) | 24 (2.6 – 230) | 3.9 (0.3 – 210) | 20 (0.2 – 360) |

| IIB | 33 | 38 (0 – 540) | 490 (40 – 1800) | 1.6 (0.1 – 23) | 20 (2.4 – 200) | 6.4 (0.2 – 65) | 17 (0.1 – 540) |

| IV | 37 | 18 (0 – 310) | 270 (54 – 1100) | 1.6 (0 – 14) | 15 (0 – 91) | 9.1 (0.2 – 190) | 15 (0.2 – 340) |

| P value | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.98 | |

Abbreviations: PR, progesterone receptor; EIG121, estrogen-induced gene – 121; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; sFRP, secreted frizzled-related protein; ρ, Spearman correlation coefficient; WHO, World Health Organization; AJCC, American Joint Commission on Cancer.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 131 PanNETs, we demonstrated that most PanNETs express the hormone receptor ERβ, and that the ERβ Allred score significantly correlated with expression of some estrogen-induced genes, suggesting a role of ERβ in their regulation. Our study also showed that high levels of ERβ immunohistochemical staining and high expression of some estrogen-induced genes were significantly associated with PanNETs with small size, low WHO grade and low AJCC stage, suggesting that this “hormonal” subset of PanNETs is associated with better prognostic features. The novelty of this study is that it demonstrates the possible involvement of estrogen regulation in PanNET tumorigenesis, thereby providing rationale for molecular subclassification and novel hormonal therapeutic strategies. For an indolent malignancy such as PanNET, hormonal approaches may be an attractive therapeutic option for patients.

ERα and ERβ are both members of the nuclear steroid receptor superfamily of transcription. They are present on distinct chromosomes; ERα is located on chromosome 6 (6q25)28 while ERβ is located on chromosome 14 (14q22-24)29. Both have a highly conserved DNA binding domain region which allows them to bind to similar target sites, but the activation function domain (AF-1, involved in protein-protein interaction30 and transcriptional activation31), hinge region (nuclear localization signal), ligand binding domain, coregulator binding surface, dimerization domain, and activation function 2 domain (AF-2, involved in hormone-dependent activation32) are not well conserved (30 – 53% homology between the two receptors)33. While both exhibit similar affinities for estradiol, they show different affinities for a wide variety of other compounds including anti-estrogens and phytoestrogens34. Although they have been shown to have overlapping organ distribution, they also localize to distinct tissue and/or cell subtype in the same tissue or exhibit differing levels of expression in the same tissue34. These differences may account for the differences in their tissue specific biologic action.

The previous studies on ERα immunohistochemical expression in PanNETs showed conflicting results. Alabraba, et al found ER (alpha) positivity in 10 of 25 insulinomas (40%)18, Arnason, et al. found only weak and focal staining in 5 of 40 tumors (12.5 %) with no tumors exhibiting strong nuclear staining in their study 12 while Viale, et al. (n=96)17 found no ER staining in the tumors analyzed. Similar to Viale, et al., we found no ERα staining in the 80 PanNETs included in our TMAs, which included 5 insulinomas.

On the other hand, ERβ immunohistochemistry has been reported in insulinomas, although studies on other types of PanNETs, non-functional tumors and non-insulinomas, are lacking. In the study by Alabraba, et al. analyzing 25 insulinomas, they also found strong, diffuse (greater than 50% of tumor cells) immunohistochemical staining in 20 of 25 and weak, focal (less than 50% of tumor cells) staining in one other case, totaling 21 of 25 (84%) PanNETs with positive immunohistochemical staining for ERβ18. In our study, we showed that strong diffuse nuclear ERβ immunohistochemical staining was present in normal pancreatic acinar cells, ductal epithelium and islets of Langerhans (Figure 1) and 30% of PanNETs, low positivity was seen in 66% of PanNETs while only 4% of PanNETs had no nuclear staining for ERβ. Our results are compatible with the high frequency of ERβ staining previously reported in insulinomas18.

The physiologic role of ERβ in the pancreas is unclear. Previous studies suggest a role for ERβ in β–cell function. In vitro studies have shown that 17β-estradiol regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by inhibiting ATP-sensitive potassium channels through ERβ in mouse pancreatic β–cells35, as well as in human islets of Langerhan cells36. In addition, the selective ERβ agonist WAY200070 restores β–cell mass by increased proliferation in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic mice36. The mechanism through which ERβ increases β–cell proliferation remains unknown. Based on our results, we hypothesize that dysregulation of this ERβ signaling contributes to the development of PanNETs.

It is well established that increased signaling through hormone receptors plays an important role in the development of large subsets of breast, endometrial and prostate cancers. Cancers with intact expression of ERα and AR are typically slow-growing and confer a better prognosis than tumors that are negative for hormone receptor expression. ERβ has similar properties in cancers. In vitro studies of ovarian cancer cell lines have shown that ERβ inhibited cell proliferation by decreasing the proportion of cells in S phase and increasing the proportion of cells in G2/M phase by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation thereby reducing cyclin D1 expression, and in turn downregulating phosphorylation of Rb37. In breast cancer cell lines, ERβ induced G2 cell cycle arrest by downregulating cyclin D1, cyclin A and c-myc expression thereby upregulating expression of p21 and p27, in a ligand-independent mechanism38. Moreover, studies on patients with breast carcinoma have shown that ERβ immunohistochemical expression correlated with negative axillary node status (P < .0001)39 and low grade (P=.0003)39, was an independent predictor of longer disease-free survival (HR=0.264, 95% CI 0.12 – 0.58, P=.001)40 and overall survival (HR=0.384, 95% CI 0.18 – 0.80, P=.01)40 by multivariate analysis. Among PanNETs in our study, we found that high immunohistochemical positivity for ERβ significantly correlated with small size (P=.01), low WHO grade (G1, P=.02) and low AJCC stage (stage I-IIB, P=.006).

Among the estrogen-induced genes evaluated, we found that PR and EIG121 mRNA expression were significantly correlated with ERβ immunohistochemical staining in PanNETs, suggesting a possible role for ERβ in their regulation. The remaining genes in the panel utilized for this study, while regulated by estrogen in the female endometrium, may be regulated by other factors in addition to estrogen in the pancreas. The utility of PR immunohistochemistry as a prognostic factor has been shown in previous studies. Viale, et al. analyzed 96 PanNETs and showed that absent PR staining is significantly associated with the presence of metastases, large vessel invasion and extension into adjacent organs (P=.0003)17. Pelosi, et al. analyzed 54 PanNETs and showed that absent PR staining correlated with shorter survival (P=.013) by univariate analysis23. Recently, we found that patients with PR-negative PanNETs had a significantly worse overall survival, independent of AJCC stage (HR=3.1, CI=1.4-7.1, P=.007)41. Our study is the first to evaluate the prognostic significance of PR mRNA expression in PanNETs. In agreement with immunohistochemical studies, decreased PR mRNA expression was significantly associated with WHO intermediate grade and AJCC stage IV disease.

EIG121 upregulation has been shown in type I endometrial carcinomas, tumors associated with estrogen regulation and generally favorable prognosis. Deng, et al. analyzed EIG121 mRNA expression in endometrium of premenopausal and postmenopausal women and found a 1.9-fold increase in proliferative (estrogen-dominated) phase compared to secretory phase and a 3.8- and > 21-fold increase in endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma, respectively, compared to normal endometrium15. In their study, they also found that EIG121 was significantly down-regulated in type II endometrial carcinomas, which are typically not associated with estrogen exposure and, present with advanced stage and confer worse patient prognosis. Our study is the first to investigate the expression of EIG121 in PanNETs. Similar to other carcinomas, we found upregulation of EIG121 mRNA expression in tumors with low AJCC stage. We have previously shown that EIG121 regulates autophagy and promotes cell survival under stress42, however, the function of high EIG121 in PanNETs is not entirely clear.

The finding that PanNETs with small size, low WHO grade and/or low AJCC stage disease showed high immunohistochemical positivity for ERβ and upregulation of PR and EIG121 mRNA expression suggest that a subset of PanNETs, namely those with indolent disease, may be molecularly distinct from intermediate grade tumors and those with advanced disease. As we have learned from breast and uterine carcinomas, the heterogeneity of patient outcome may be influenced, in part, by hormone receptor status. Molecular classification of breast carcinoma into ER+/HER2−, ER+/HER2+, and ER−/HER2−, described by Kapp, et al.43 has significantly helped in risk assessment and guiding optimal treatment of patients. Similarly, classification of endometrial carcinomas into type I and type II has been traditionally based on tumor response to estrogen and ER status16. Molecular subclassification of PanNETs based on estrogen regulation may help in risk stratification. Our results demonstrate that routinely acquired formalin-fixed paraffin embedded patient material may be used effectively for this purpose.

To date, the primary treatment of patients with PanNETs remains surgery. Two new targeted therapies have been recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients with advanced PanNETs. Sunitinib (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and everolimus (mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor) have been shown in phase III trials to improve progression-free survival compared to placebo4. Despite these advances, treatment of patients with advanced PanNET remains sub-optimal9. ERβ has been identified as a potential molecular target in breast, ovarian, prostate and colon cancer chemoprevention by the American Association for Cancer Research task Force Report44. Evidence presented here suggests that targeting ERβ in a subset of patients with PanNETs may provide another treatment avenue.

In summary, we found that a subset of PanNETs, those with indolent behavior, have upregulated PR and EIG121 mRNA expression, which may be regulated by ERβ. Thus, estrogen regulation in PanNETs may uncover the underlying mechanisms driving outcome heterogeneity and could potentially provide a rational target for novel treatment strategies in patients with PanNETs.

Acknowledgments

Grant numbers and sources of support:

NIH 2P50 CA098258-06 SPORE in Uterine Cancer (RRB)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fesinmeyer MD, Austin MA, Li CI, et al. Differences in survival by histologic type of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1766–1773. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Merkow RP, et al. Application of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma staging system to pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao JC, Lagunes DR, Kulke MH. Targeted Therapies in Neuroendocrine Tumors (NET): Clinical Trial Challenges and Lessons Learned. Oncologist. 2013;18:525–532. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klimstra DS, Arnold R, Capella C, et al. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. pp. 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith J, Reidy-Lagunes D. The management of extrapulmonary poorly differentiated (high-grade) neuroendocrine carcinomas. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:100–108. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yachida S, Vakiani E, White CM, et al. Small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas are genetically similar and distinct from well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:173–184. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182417d36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rindi G, Bordi C. Highlights of the biology of endocrine tumours of the gut and pancreas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:427–436. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al. Consensus Guidelines for the Management and Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2013;42:557–577. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31828e34a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tetu B, Ro JY, Ayala AG, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Part I. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1987;59:1803–1809. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10<1803::aid-cncr2820591019>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allred DC, Carlson RW, Berry DA, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Estrogen Receptor and Progesterone Receptor Testing in Breast Cancer by Immunohistochemistry. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(Suppl 6):S1–S21. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0079. quiz S22-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnason T, Sapp HL, Barnes PJ, et al. Immunohistochemical expression and prognostic value of ER, PR and HER2/neu in pancreatic and small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;93:249–258. doi: 10.1159/000326820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng L, Shipley GL, Loose-Mitchell DS, et al. Coordinate regulation of the production and signaling of retinoic acid by estrogen in the human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2157–2163. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westin SN, Broaddus RR, Deng L, et al. Molecular clustering of endometrial carcinoma based on estrogen-induced gene expression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2126–2135. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.22.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng L, Broaddus RR, McCampbell A, et al. Identification of a novel estrogen-regulated gene, EIG121, induced by hormone replacement therapy and differentially expressed in type I and type II endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8258–8264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lax SF, Kurman RJ. A dualistic model for endometrial carcinogenesis based on immunohistochemical and molecular genetic analyses. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1997;81:228–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viale G, Doglioni C, Gambacorta M, et al. Progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in pancreatic endocrine tumors. An immunocytochemical study of 156 neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, and skin. Cancer. 1992;70:2268–2277. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921101)70:9<2268::aid-cncr2820700910>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alabraba EB, Taniere P, Reynolds GM, et al. Expression and functional consequences of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in human insulinomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:1081–1088. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieuwenhuizen AG, Schuiling GA, Hilbrands LG, et al. Proliferation of pancreatic islet-cells in cyclic and pregnant rats after treatment with progesterone. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30:649–655. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnaterra R, Porzio O, Piemonte F, et al. The effects of pregnancy steroids on adaptation of beta cells to pregnancy involve the pancreatic glucose sensor glucokinase. J Endocrinol. 1997;155:247–253. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1550247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao J, Qiao L, Friedman JE. Prolactin, progesterone, and dexamethasone coordinately and adversely regulate glucokinase and cAMP/PDE cascades in MIN6 beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E304–E310. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00210.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picard F, Wanatabe M, Schoonjans K, et al. Progesterone receptor knockout mice have an improved glucose homeostasis secondary to beta -cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15644–15648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202612199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelosi G, Bresaola E, Bogina G, et al. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas: Ki-67 immunoreactivity on paraffin sections is an independent predictor for malignancy: a comparative study with proliferating-cell nuclear antigen and progesterone receptor protein immunostaining, mitotic index, and other clinicopathologic variables. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1124–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Wolff AC. Clinical Notice for American Society of Clinical Oncology-College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations on ER/PgR and HER2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, et al. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuqua SA, Schiff R, Parra I, et al. Estrogen receptor beta protein in human breast cancer: correlation with clinical tumor parameters. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2434–2439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosden JR, Middleton PG, Rout D. Localization of the human oestrogen receptor gene to chromosome 6q24----q27 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1986;43:218–220. doi: 10.1159/000132325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, et al. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onate SA, Boonyaratanakornkit V, Spencer TE, et al. The steroid receptor coactivator-1 contains multiple receptor interacting and activation domains that cooperatively enhance the activation function 1 (AF1) and AF2 domains of steroid receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12101–12108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bardin A, Hoffmann P, Boulle N, et al. Involvement of estrogen receptor beta in ovarian carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5861–5869. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tremblay GB, Tremblay A, Copeland NG, et al. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional analysis of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:353–365. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.3.9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearce ST, Jordan VC. The biological role of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;50:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallo D, De Stefano I, Grazia Prisco M, et al. Estrogen receptor beta in cancer: an attractive target for therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:2734–2757. doi: 10.2174/138161212800626139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soriano S, Ropero AB, Alonso-Magdalena P, et al. Rapid regulation of K(ATP) channel activity by 17{beta}-estradiol in pancreatic {beta}-cells involves the estrogen receptor {beta} and the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1973–1982. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alonso-Magdalena P, Ropero AB, Garcia-Arevalo M, et al. Antidiabetic actions of an estrogen receptor beta selective agonist. Diabetes. 2013;62:2015–2025. doi: 10.2337/db12-1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bossard C, Busson M, Vindrieux D, et al. Potential role of estrogen receptor beta as a tumor suppressor of epithelial ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paruthiyil S, Parmar H, Kerekatte V, et al. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits human breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor formation by causing a G2 cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2004;64:423–428. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarvinen TA, Pelto-Huikko M, Holli K, et al. Estrogen receptor beta is coexpressed with ERalpha and PR and associated with nodal status, grade, and proliferation rate in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64702-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakopoulou L, Lazaris AC, Panayotopoulou EG, et al. The favourable prognostic value of oestrogen receptor beta immunohistochemical expression in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:523–528. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Estrella J, Broaddus R, Mathews A, et al. Progesterone Receptor and PTEN Expression Predict Survival in Patients with Low and Intermediate Grade Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0195-OA. Accepted Sept. 2013, In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng L, Feng J, Broaddus RR. The novel estrogen-induced gene EIG121 regulates autophagy and promotes cell survival under stress. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e32. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapp AV, Jeffrey SS, Langerod A, et al. Discovery and validation of breast cancer subtypes. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelloff GJ, Lippman SM, Dannenberg AJ, et al. Progress in chemoprevention drug development: the promise of molecular biomarkers for prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer--a plan to move forward. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3661–3697. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]