Abstract

This study evaluated a theory-guided cognitive-behavioral counseling (CBC) intervention for smoking cessation during pregnancy and postpartum. It also explored the mediating role of cognitive-affective variables on the impact of CBC. Underserved inner city pregnant women (N = 277) were randomized to the CBC or a best practice (BP) condition, each of which consisted of two prenatal and two postpartum sessions. Assessments were obtained at baseline, late pregnancy, and 1- and 5-months postpartum. An intent-to-treat analysis found no differences between the two groups in 7-day point-prevalence abstinence. However, a respondents-only analysis revealed a significantly higher cessation rate in the CBC (37.3 %) versus the BP (19.0 %) condition at 5-months postpartum follow-up. This effect was mediated by higher quitting self-efficacy and lower cons of quitting. CBC, based on the Cognitive-Social Health Information Processing model, has the potential to increase postpartum smoking abstinence by assessing and addressing cognitive-affective barriers among women who adhere to the intervention.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Underserved pregnant women, Postpartum, Cognitive behavioral intervention, Psychosocial mediators

Introduction

Despite the adverse maternal, fetal, and infant health risks (Erickson & Arbour, 2012; Schneider et al., 2010), approximately 22 % of women in the U.S. smoke during the 3 months prior to pregnancy and two-thirds of them continue to smoke during pregnancy (Tong et al., 2009). Among the women who quit smoking while pregnant, more than half relapse by 6 months postpartum, and up to 80 % relapses by 1 year (Mullen, 2004; Tran et al., 2013). In particular, low-income (i.e., under $15,000) women are twice as likely as their higher income counterparts to both smoke during pregnancy and relapse within 4 months postpartum (Tong et al., 2009), representing an important target population for smoking cessation during pregnancy and the transition to the postpartum period. Low-income inner city, underserved pregnant women experience a number of unique challenges, including single parenting, living in disruptive home environments and violent neighborhoods, feeling isolated, as well as having additional comorbid health risk factors (Pletsch et al., 2003). These life stressors may not only precipitate smoking behavior, but also produce greater barriers to initiate or sustain cessation.

Potentially effective interventions for underserved pregnant women include clinic-based large scale interventions utilizing the 5A’s model recommended in the clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, which was originally established in 2000 and updated in 2008 (Fiore et al., 2000, 2008). Although these interventions (Manfredi et al., 1999; Windsor et al., 2011, 2014) have demonstrated effectiveness in achieving smoking cessation compared to usual care, the post-intervention cessation rates only reach 10–17 %. Since available programs are generally low intensity, consisting of health providers’ advice to quit, brief cessation counseling (e.g., 10–15 min), and/or provision of an education booklet or video during pregnancy, this type of low dose intervention may be insufficient to address the challenges stemming from the complex psychosocial issues faced by low-income inner city women smokers.

Further, most clinic-based studies focused on prenatal smoking cessation, with few studies leveraging the critical period of the prepartum to postpartum transition. This transition represents a unique window of opportunity for postpartum cessation since the barriers to smoking cessation have been shown to change after delivery. Decreased motivation and low social pressure to maintain abstinence, stress associated with caring for a newborn, insufficient support and resources for coping with new challenges as they arise, and postpartum depression become paramount (Curry et al., 2001; Park et al., 2009; Wen et al., 2014a, b), particularly among those who live in disadvantaged urban areas (Harmer & Memon, 2013).

The existing studies that focus on the prepartum to postpartum transition in prenatal clinics and other health care delivery settings (El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Gadomski et al., 2011; Mullen et al., 2000; Reitzel et al., 2010) show greater abstinence (22–42 %) during the follow-up period in the pre/post intervention group than the usual care group or those who receive only prepartum assistance (16–28 %). However, the interventions under study either provided only generic health communication materials, such as educational videos and newsletters (Mullen et al., 2000), or a combination of 5As-based brief cessation counseling and provision of an incentive (e.g., voucher for diapers) for abstinence (Gadomski et al., 2011), rather than delivering a theory-based approach. In addition, the study populations were primarily Caucasian (75–91 %). Although two of the studies (El-Mohandes et al., 2008; Reitzel et al., 2010) used theory-based interventions (e.g., social-cognitive approaches), tailored to the stage of readiness for change among diverse or minority underserved women, they did not systematically assess or address individuals’ unique psychosocial barriers to cessation.

Further, it is important to delineate the processes underlying therapeutic change in order to interpret effects obtained; yet few studies examined the factors that mediate intervention effects. Therefore, there is a need to further develop and evaluate theory-guided smoking cessation interventions that assess and address the unique cognitive affective barriers of diverse underserved inner city women as they transition into the postpartum period. Exploration of the potential mediators of the relative effectiveness of the interventions is an additional need for further advancements in this area.

Guided by the Cognitive-Social Health Information Processing (C-SHIP) model (Miller et al., 1996), the present study explored the impact of an intervention tailored to the target population’s psychosocial barriers to smoking cessation during pregnancy, as well as the shift in barriers into postpartum. The C-SHIP model provides an integrative framework that builds on existing cognitive-social theory to identify the key cognitive and affective processing units (e.g., risk perception, self-efficacy, decisional balance, and emotional distress) that influence the uptake and maintenance of health-related behaviors. The cornerstone of this approach is that these factors interact with each other as the information is processed cognitively and emotionally, and this cognitive-affective processing is ultimately transformed into decisions and behavioral scripts. Therefore, C-SHIP based interventions focus on assessing and addressing the distinct pattern of the specific cognitive and affective variables that are activated in a given individual. In the area of smoking cessation, higher levels of self-efficacy (Manfredi et al., 2007; Roske et al., 2008) and the pros of quitting (Bock et al., 2014), along with lower levels of the cons of quitting (Schnoll et al., 2005) and emotional distress (Park et al., 2009; Psaros et al., 2012) have been associated with initiation and maintenance of smoking abstinence.

In the present study, we compared a C-SHIP based cognitive-behavioral counseling (CBC) smoking cessation intervention with a moderate intensity best practice control condition (BP) across the prepartum and postpartum phases. It was hypothesized that smokers receiving CBC would show higher cessation rates, compared to those receiving BP, at the prenatal follow-up, and at the two postpartum follow-ups. We also evaluated whether the effect of the C-SHIP based intervention on smoking status was mediated through changes in cognitive-affective variables (i.e., enhanced self-efficacy; high pros and low cons of quitting; and reduced emotional distress), in order to delineate the processes underlying intervention effects. It was expected that participants in the CBC group would show greater change in the cognitive-affective variables, compared to those in the BP group, and that these changes would mediate the impact of the CBC on abstinence rates.

Methods

The study utilized a prospective randomized controlled design (clinicaltrials.gov registration number NCT022 11430). The Fox Chase Cancer Center and Temple University Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures. Participants were recruited at the Prenatal Care Clinic at Temple University Hospital (TUH) in Philadelphia from January 2003 to May 2007. The 2008 Update of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence was not yet issued when the study data were collected. However, the components of both the control and intervention conditions in the study were designed to be consistent with the anticipated 2008 recommendations, since the evidence base already suggested that these approaches would be the most effective, depending on the context. Specifically, for the control condition, the present study followed the 5A’s based best practice guidelines originally established in 2000. In the 2008 update, the 5A’s model is still considered the best practice brief intervention and is recommended as a standard of care in the clinic setting. With regard to the intervention condition in the present study, the 2008 update recommends the provision of tailored self-help materials, multiple counseling sessions, utilization of motivation intervention techniques for smokers not willing to make a quit attempt, provision of counseling interventions for identified light smokers, and the addition of medication whenever feasible and appropriate. The CBC which was used in the intervention group incorporated these components. Because the updated guidelines also indicate that pregnant women are one of the specific populations in which medication has not been shown to be effective, the provision of counseling without medication was considered to be most medically conservative and appropriate by the treating providers.

Participants

Recruitment procedures involved providing initial recruitment forms to the clinic that were compiled with the medical forms so that potential participants could complete them during their initial prenatal clinic visit. Women were eligible for study participation if they were: (1) pregnant (in their first trimester), (2) had smoked one puff of a cigarette in the 30 days prior to recruitment, (3) 18 years or older, (4) reachable by a telephone. Of the 1121 patients initially screened for study eligibility by telephone, 608 (54.2 %) were ineligible due to the following reasons: 249 (40.9 %) were over 25 weeks gestation, 27 (4.4 %) had not smoked at least one puff in the last 30 days, and 275 (45.3 %) were not reachable by telephone. In addition, patients who were unable to communicate readily in English (n = 9), were receiving substance abuse treatment and/or had evidence of drug and alcohol abuse (n = 4), or had miscarriages (n = 20) or were no longer a patient at clinic (n = 24) were excluded. Of the 513 eligible women, 448 (87 %) patients expressed interest in the study by providing verbal consent and scheduling a baseline study appointment. The primary reasons reported for those who were eligible but who declined study participation (n = 65) were a lack of interest and time. Of the 448 women who were scheduled, 277 (62 %) patients attended the initial appointment. A predictive power analysis indicated that we required 275 women to have 80 % power to detect a small effect size (d = 0.15).

Procedure

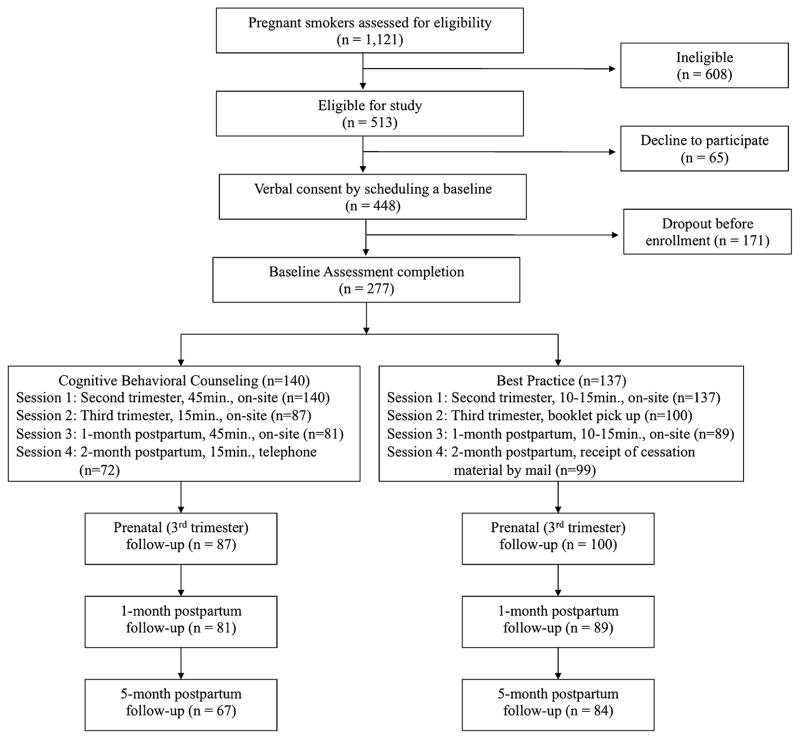

When participants (n = 277) came to the clinic for their second trimester visits, women provided written informed consent and completed a baseline assessment. Following the baseline assessment, participants were allocated to either: (1) the C-SHIP based CBC intervention; or (2) the BP control condition, using computer-generated random number sequences. As shown in the flowchart of recruitment and retention (Fig. 1), 140 women were randomized to the CBC group and 137 were randomized to the BP group. The interventions were provided by a master’s level health educator who received CBC and BP protocol training and ongoing supervision. Intervention session time was dedicated to the delivery of intervention or control group content, and did not include the completion of assessments.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of recruitment and attendance at counseling sessions and follow-up assessments

Cognitive behavioral counseling (CBC) group

The intervention condition consisted of two prenatal and two postpartum contacts, which is consistent with the recommendation of high intensity with multiple sessions. Participants in the CBC intervention met with a health educator: for 45 minutes (session 1) during their second trimester visit (13–25 weeks gestation); for 15 minutes (session 2) during their third trimester visit (26–38 weeks gestation); and for 45 minutes (session 3) during the first postpartum visit (2–6 weeks postpartum). Session 4 was a booster session delivered by telephone at 8–10 weeks postpartum for 15 min.

Building on our established cognitive-affective processing protocols (Miller et al., 2013; Schnoll et al., 2005; Wen et al., 2014a, b), and guided by the C-SHIP model, the intervention sessions were designed to identify and address participants’ cognitive-affective barriers to smoking cessation in the context of pregnancy and postpartum adaptation, focusing on risk perceptions, quitting self-efficacy, the pros and cons of quitting, emotional distress, and self-regulatory strategies. An individual’s particular barriers to cessation were identified by her cognitive-affective responses elicited through prompts and role-play exercises during the initial session. The prompts and role-play exercises allowed the participant to experience and assess her own likely cognitive-affective reactions to smoking cessation efforts, thereby anticipating potential barriers (e.g., depressed mood, etc.) to behavior change. Once the participant’s distinctive pattern of cognitive-affective barriers was identified, an individualized quit plan and coping strategies were discussed and practiced.

Specifically, sessions 1 and 2 focused on discussing participants’ cognitive-affective barriers, developing and evaluating a quit plan tailored to their personal beliefs and affective reactions, and practicing self-regulatory techniques for resisting personal smoking triggers. Session 3 focused on reviewing smoking history during pregnancy, discussing postpartum barriers to abstinence, reinforcing the effects of smoking on the health of both the mother and infant, identifying postpartum smoking triggers, and practicing coping strategies to deal with existing and new barriers to cessation. Session 4 was conducted to boost participants’ motivation to quit smoking and to review the ongoing practice of individualized cessation strategies.

Best practice (BP) group

Since the Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence was established in 2000 (Fiore et al., 2000), the 5A’s based brief smoking cessation counseling has been recommended to be offered to pregnant smokers during a clinic visit. The 5A’s model suggests that clinicians should provide care to their patients by (1) Asking about smoking, (2) Advising to stop smoking, (3) Assessing motivation to quit, (4) Assisting with strategies and resources, and (5) Arranging specific follow-up. Despite these guidelines, a significant portion of obstetric providers still do not fully comply with this approach for prenatal patients. Most prenatal care providers usually or always ask about smoking and advise to quit. However, only one quarter or fewer providers use all 5A’s (Bailey & Jones Cole, 2009; Chang et al., 2013). The study clinic was one of those that did not have the resources to reliably implement the 5A’s method as their standard of care. Nonetheless, for the purpose of the present study, the control group was designed to conform to the BP guideline to be consistent with the extant optimal patient management and for ethical considerations.

Specifically, participants in the BP condition attended a 5A’s based counseling session for 10–15 min during their second trimester visit (session 1) and received generic quit smoking materials at the time of their third trimester visit (session 2). Additionally, to equate for postpartum attention, the BP group attended another brief 5A’s based counseling session at the first postpartum visit (session 3) and received a mailing of an education newsletter as a booster session (session 4). The timing of the BP contacts was designed to match the timing of the CBC’s prenatal and postpartum counseling.

Data collection

Assessments were obtained at the second trimester (baseline), the third trimester (prenatal follow-up), and 2–6 weeks postpartum (1-month postpartum follow-up), to coincide with women’s clinic appointments and counseling sessions. The final assessment was obtained at 20–22 weeks post-partum (5-month postpartum follow-up). As part of the assessment, women who reported quitting were asked to provide a saliva sample to confirm self-reported smoking cessation status. Ninety-six percent of participants who reported being abstinent for the previous 7 days provided saliva samples, thus cotinine level was used as the criterion. For those who did not provide saliva samples, self-report was used as a measure of smoking cessation status. Participants were provided $20 as compensation for completing the baseline assessment, $25 for completing the prenatal follow-up assessment, $30 for the completion of the 1- and 5-month postpartum follow-up assessments, respectively. All eligible participants were tracked for future appointment contacts regardless of their adherence to a previous appointment.

Measures

Demographics (measured at baseline)

Information on age, ethnicity, educational level, marital status, income level, and number of children living in the household was collected at baseline.

Baseline smoking behaviors (measured at baseline)

Nicotine addiction level

The Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Addiction (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991) was used to assess the level of nicotine dependence. The FTND consists of six items yielding a sum score between 1 (low dependence) and 10 (high dependence).

Average number of cigarettes

Average number of cigarettes smoked per day in past 7 days was assessed by self-report.

Intention to quit

Intention to quit in the next 30 days was assessed by self-report through a yes or no question.

Outcome variable (measured at baseline and all three follow-up assessments)

Smoking cessation rate

Cessation rates were assessed through self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence which was biochemically verified through saliva cotinine level. Cotinine is a metabolite of nicotine that has a half-life of 18–24 h; therefore it is sensitive to recent changes in smoking behaviors. Cotinine levels of <10 mg are considered to be consistent with no active smoking (Jarvis et al., 2008). Therefore, participants with a cotinine level of 10 mg or above were considered smokers. Cotinine level was assessed at each follow-up but not at baseline, given that we recruited self-reported smokers and smoking behaviors are generally under-, not over-reported due to social desirability and related factors.

Mediating variables (measured at baseline, 1- and 5-month postpartum follow-up assessments)

Quitting self-efficacy

This scale is based on the well-validated Multidimensional Health-Related Control and Self-Efficacy Scale (Randall et al., 1991) and the items that are relevant to quitting smoking were used. The scale contains 10 Likert-type items (e.g. ‘I have confidence in my abilities to quit smoking for good’), ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The items were summed to yield a quitting self-efficacy score. Higher scores on this scale indicate greater quitting self-efficacy. This scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

Pros and cons of quitting

The well-validated decisional balance scale (Velicer et al., 1985) consists of eight pros and eight cons of quitting. A sample pro of quitting is: “Smoking cigarettes is hazardous to my health”. A sample con of quitting is: “I am relaxed and therefore more pleasant when smoking”. Items are assessed using a Likert-type scale with scores ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Summing the pros and cons items separately yielded a quitting pros and a quitting cons score (from 8 to 32), respectively. Higher scores on each scale indicate a greater level of pros or cons of quitting. The internal consistency reliabilities for the pros and cons scales in this study were 0.69 and 0.63, respectively.

Affective distress about quitting

The 30-item Profile of Mood States (POMS) short form was used to assess affective distress about quitting (Curran et al., 1995). The POMS consists of six sub-dimensions: anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. Each item was scored using a Likert-type scale, with values ranging from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘extremely’. A Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score was obtained by summing the five negative subscales (anger, confusion, depression, fatigue and tension) and subtracting the only positive affect subscale (vigor). The score ranges from 20 to 100 and a higher score indicates the presence of negative moods and psychological distress. The POMS short form is widely used and has been shown to possess good reliability and validity (Cranford et al., 2006).

Data analysis

Potential baseline differences in the two intervention groups (CBC vs. BP) were examined by a series of Chi square and t tests. The impact of the intervention on smoking cessation rates was examined by binary logistic regression analysis to determine if the quit rate was higher for the CBC intervention, after adjusting for potential confounding variables such as demographics and baseline smoking behaviors (e.g., average number of cigarettes for 7 days, nicotine addiction level at baseline). Both intent-to-treat and responder-only approaches were conducted for each follow up time point. For the intent-to-treat approach, participants who did not complete follow-up assessments were coded as smokers.

For the mediation analysis, the indirect effect was estimated using the non-parametric bootstrapping technique (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) which provides a robust method to test the significance of the indirect path with greater statistical power. The indirect effect of individual cognitive-affective variables was evaluated by a series of univariate mediation analyses and the total indirect effect of multiple mediators was assessed by a multiple mediation analysis.

Results

Baseline demographic and smoking-related characteristics

Participants were predominantly of minority race/ethnicity (i.e. African-American, 56 %; Hispanic, 12 %), single (89 %), low-income (50 %; <$15,000), low education (>65 % high school or less). Mean age was 27 years, and average number of children in the household was two. Women reported smoking an average of 7.6 cigarettes per day (7-day point prevalence; SD = 7.4), with a low level of nicotine dependence (M = 2.03, SD = 1.12) at baseline. Women had an average of 6.3 quit attempts that lasted for at least 24 h in the past year (M = 6.3, SD = 17.8), and the majority (88.7 %) of them reported an intention to quit in 30 days. Regarding baseline psychosocial variables, participants indicated a low to moderate level of quitting self-efficacy (M = 28.1, SD = 4.51) and endorsed more pros (M = 25.04, SD = 3.10) than cons of quitting (M = 19.28, SD = 2.82). POMS TMD score (M = 17.1, SD = 19.1) indicated a low level of general mood disturbance among study participants. T test and Chi squared comparisons showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on any of the baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants characteristics by treatment group

| Predictor variables | BP (N = 137)

|

CBC (N = 140)

|

Total (N = 277)

|

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | N | Percent | N | Percent | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.65 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 45 | 33.83 | 38 | 28.57 | 83 | 31.20 | |

| Hispanic | 16 | 12.03 | 17 | 12.78 | 33 | 12.41 | |

| Black/African American | 72 | 54.14 | 78 | 58.65 | 150 | 56.39 | |

| Marital status | 0.65 | ||||||

| Married/living with a partner | 9 | 7.83 | 16 | 13.79 | 25 | 10.82 | |

| Single | 106 | 92.17 | 100 | 86.21 | 206 | 89.18 | |

| Education level | 0.40 | ||||||

| High school or less | 88 | 66.17 | 97 | 69.79 | 185 | 67.97 | |

| Some college | 44 | 31.58 | 40 | 28.77 | 84 | 30.15 | |

| College graduate | 3 | 2.26 | 2 | 1.44 | 5 | 1.84 | |

| Income level | 0.77 | ||||||

| $0–15,000 | 54 | 54.55 | 45 | 45.92 | 99 | 50.25 | |

| $15,001–30,000 | 28 | 28.28 | 34 | 34.69 | 62 | 31.47 | |

| $30,001–45,000 | 12 | 12.12 | 12 | 12.24 | 24 | 12.18 | |

| $45,001–60,000 | 4 | 4.04 | 6 | 6.12 | 10 | 5.08 | |

| $60,001–75,000 | 1 | 1.01 | 1 | 1.02 | 2 | 1.02 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

| |||||||

| Age | 26.62 | 6.57 | 26.76 | 5.95 | 26.69 | 6.26 | 0.86 |

| Number of children in household | 1.57 | 1.50 | 1.59 | 1.65 | 1.58 | 1.57 | 0.94 |

| Smoking behaviors | |||||||

| Number of cigarettes per day for 7 days | 7.90 | 7.62 | 7.37 | 7.17 | 7.61 | 7.39 | 0.55 |

| Fag. test of nicotine addiction | 2.01 | 1.11 | 2.04 | 1.14 | 2.03 | 1.12 | 0.84 |

| Intention to quit in the next 30 days [N (%)] | |||||||

| Yes | 121 | 89 | 121 | 86.4 | 243 | 87.7 | 0.59 |

| No | 16 | 11.2 | 19 | 13.6 | 34 | 12.3 | |

| Cognitive affective variables | |||||||

| Self-efficacy score | 2.81 | 0.43 | 2.82 | 0.47 | 2.82 | 0.45 | 0.80 |

| Pros of quitting score | 25.17 | 3.02 | 24.94 | 3.19 | 25.04 | 3.10 | 0.54 |

| Cons of quitting score | 19.42 | 2.96 | 19.17 | 2.67 | 19.28 | 2.82 | 0.47 |

| POMS total score | 17.80 | 19.76 | 16.46 | 18.62 | 17.11 | 19.16 | 0.57 |

Counseling utilization and follow-up attrition

Of the total four counseling sessions, 128 (46 %) completed all four sessions, 58 (21 %) completed three sessions only, and 28 (10 %) completed two sessions only. Sixty-three (23 %) participants never returned for the following sessions after the first session. In the CBC group (n = 140), 57 (40.7 %) completed all four sessions, 25 (17.9 %) completed three sessions, 19 (13.6 %) completed two sessions, and 39 (27.9 %) completed one session only. In the BP group (n = 137), 71 (52.2 %) completed all four session, 33 (24.3 %) completed three sessions, 10 (7.3 %) completed two sessions, and 23 (16.9 %) completed one session only. More women in the CBC group than in the BP group completed only one session (p = .031). There were no significant group differences among those who completed two, three, and four counseling sessions.

Participant attrition was 32 % (n = 90) for the prenatal, 39 % (n = 107) for 1-month postpartum, and 45 % (n = 126) for 5-month postpartum follow-ups. Women in the BP group were more likely than those who were in the CBC group to complete prenatal follow-up assessment (53.5 vs. 46.5 %, p = .043) and 5-month postpartum follow-up assessment (55.6 vs. 44.4 %, p = .020). No significant attendance differences between the BP and CBC groups were found for the 1-month postpartum follow-up assessment.

Effects of the CBC intervention on smoking cessation by intent-to-treat and respondents only approaches

As shown in Table 2, smoking cessation rates were not significantly different between the CBC and BP groups at all three follow-up time points in the intent-to-treat analysis. However, in the respondent-only analysis at 5-months post-partum (n = 151), participants in the CBC group (37.3 %) were significantly more likely to be abstinent compared with those in the BP group [19.0 %; χ2(1) = 6.29, p = .012]. This effect was not found at the prenatal and 1-month postpartum follow-ups.

Table 2.

Abstinence rates at follow-ups by treatment condition

| Outcome 7-Days abstinence |

BP group

|

CBC group

|

Odds ratio | 95 % CI | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | 95 % CI | N | Percent | 95 % CI | ||||

| Pre-partum follow-up | |||||||||

| Intent-to-treat (n = 277) | 16/137 | 11.70 | 6.8–18.3 | 21/140 | 15.00 | 9.5–22 | 1.32 | 0.66–2.7 | 0.430 |

| Responder only (n = 187) | 16/100 | 16.00 | 9.4–24.7 | 20/87 | 23.00 | 14.6–33.2 | 1.57 | 0.75–3.3 | 0.227 |

| 1-Month postpartum follow up | |||||||||

| Intent-to-treat (n = 277) | 26/137 | 19.80 | 12.8–26.6 | 21/140 | 15.00 | 9.5–22 | 1.41 | 0.75–2.63 | 0.288 |

| Responder only (n = 170) | 26/89 | 29.20 | 20.1–39.8 | 21/81 | 25.90 | 16.8–36.9 | 1.18 | 0.60–2.32 | 0.632 |

| 5-Month postpartum follow up | |||||||||

| Intent-to-treat (n = 277) | 16/137 | 11.70 | 6.8–18.3 | 25/140 | 17.90 | 11.9–25.2 | 1.63 | 0.82–3.2 | 0.155 |

| Responder only (n = 151) | 16/84 | 19.00 | 11.3–29.1 | 25/67 | 37.30 | 25.8–50 | 2.53 | 1.21–5.28 | 0.012* |

p < 0.05

Effects of the CBC intervention on smoking cessation by counseling utilization

To explore whether these results were related to the number of sessions participants attended, the impact of counseling utilization on intervention outcome was examined in a post hoc analysis. The results showed that there was greater smoking cessation in the CBC group (30.5 %) than in the BP group [15.4 %; χ2(1) = 6.09; p = .014] among the women who completed at least three of four counseling sessions (n = 186), but not among those who completed one or two counseling sessions (n = 91). One hundred fifty (99.3 %) out of 151 women who responded to the 5-month postpartum assessment completed 3 or 4 sessions, whereas 67.1 % of study participants who were included in the intent-to-treat analysis (n = 277) completed 3 or 4 sessions.

Mediating role of cognitive-affective variables in the impact of the CBC intervention on smoking cessation

Effects of CBC intervention on cognitive-affective variables

Assessment of differences between the two conditions with regard to change in the cognitive-affective variables from baseline to the 1- and 5-month postpartum follow-ups was conducted by repeated measures ANOVA. Compared to the BP condition, participants in the CBC intervention exhibited a greater decrease in the cons of quitting [F(1, 144) = 6.56, p = .011] and a greater improvement in quitting self-efficacy [F(1, 148) = 7.59, p = .007] from baseline to the 5-month postpartum follow-up. There were no significant differential changes in cognitive-affective variables between the two conditions from baseline to the 1-month postpartum follow-up.

Indirect effect of the mediators

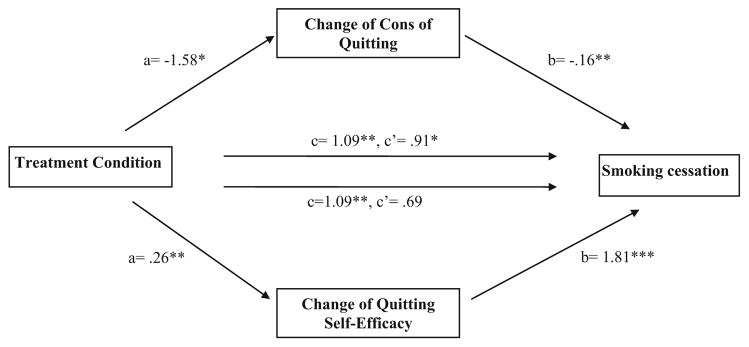

Because the cognitive-affective variables, particularly self-efficacy and cons of quitting, changed significantly more following the CBC intervention than the BP intervention from baseline to the 5-month postpartum follow-up, mediation analysis was conducted among those who participated in the 5-month postpartum follow-up. The total indirect effect of mediators was examined first by entering the changes of the scores of quitting self-efficacy, pros and cons of quitting, and POMS in the multiple mediation model, simultaneously. The result showed that the total indirect effect of the four mediators was significant (0.53; 95 % CI 0.12, 1.22). Next, the indirect effects of individual cognitive-affective variables on the impact of treatment condition on smoking cessation at the 5-month postpartum follow-up were examined by a series of univariate mediation analyses. The results showed that the indirect effects for self-efficacy (0.47; 95 % CI 0.16, 1.03) and cons of quitting (0. 24; 95 % CI 0.05, 0.64) were significant. As Fig. 2 shows, when change of quitting self-efficacy was entered into the model, the association between treatment condition and smoking cessation (c′ path) was no longer significant, indicating full mediation. When change of cons of quitting was entered in the model, the significance of the relationship between treatment condition and smoking cessation (c′ path) was reduced although remained significant, indicating partial mediation.

Fig. 2.

Mediation pathway of treatment condition on smoking cessation at 5-month postpartum assessment with change of cons of quitting as the mediator. Note: a is an unstandardized regression coefficient, and b, c, and c′ are unstandardized logistic regression coefficients. *p < .05; **p <.01; ***p < .001

Discussion

This study examined the efficacy of a theory-guided counseling intervention designed to address prototypic cognitive-affective barriers to smoking cessation among low income pregnant women before and after delivery. We found comparable cessation rates between the CBC and BP groups in the intent-to-treat analysis. However, among those who participated in the 5-month postpartum follow-up assessment, women who were in the CBC group were more likely to be abstinent, compared to those in the BP group. There are two main likely explanations for these findings.

First, the lack of a significant difference between the two group arms may be due in part to the fairly strong intervention received by the BP group, in that it contained all of the components of active quit-smoking programs, except with shorter sessions and less personalized content. This is consistent with the results of a Cochrane review of 86 randomized controlled trials (Chamberlain et al., 2013), showing that the effectiveness of counseling is less pronounced when the comparison group receives moderately intensive interventions than when the comparison group receives usual care. Second, participants in the present study exhibited a relatively high level of motivation to quit. Indeed, approximately 90 % of women in this study reported an intention to quit smoking in the next 30 days. The higher motivation may have generated positive effects, even with a less intensive intervention, for this subset of women.

Of note, the CBC intervention did show efficacy for those who participated in at least 3–4 sessions. The 5-month postpartum assessment was conducted after all four counseling sessions were completed, whereas the prenatal and 1-month postpartum assessments were administered immediately before the second and third intervention sessions, respectively. Therefore, the ‘dose’ of intervention might not have been sufficient to yield group differences at the prenatal and 1-month postpartum follow-up time points. Given that the majority of respondents at the 5-month postpartum follow-up had completed at least three of the four counseling sessions, they may be the women who received adequate exposure to the tailored CBC components. This finding is consistent with studies that report a significant effect on smoking cessation of cognitive behavioral interventions with multiple sessions (i.e., three to eight) (Dornelas et al., 2006; Joseph et al., 2009; Reitzel et al., 2010).

Taken together, our results suggest that it may be effective to provide basic cessation counseling based on the 5A’s framework, combined with provision of educational materials to underserved pregnant smokers, particularly among those who manifest high levels of motivation to quit and low levels of intention to participate in an intensive intervention. However, for those who need or are willing to participate in a more intensive intervention with multiple counseling sessions (3–4 sessions), the CBC intervention may be beneficial in addressing complex psychosocial barriers and reducing smoking over the long-term.

This interpretation is consistent with the findings that the CBC intervention, but not the BP intervention, increased participants’ quitting self-efficacy and decreased their cons of quitting only at the 5-month follow-up (among the subset who completed at least three counseling sessions), but not 1-month, postpartum follow-up; these changes, in turn, were positively associated with differential post-intervention abstinence at 5-months postpartum. Previous studies have highlighted the role of psychosocial factors as mediators of smoking cessation intervention effects (Baldwin et al., 2006; Gwaltney et al., 2009; Hettema & Hendricks, 2010). In the present study, the positive associations between increased self-efficacy and decreased cons of quitting with smoking cessation contribute to the extant knowledge base (Rothman, 2000), showing that smokers’ behaviors are determined by the favorable expectations they hold about outcomes (e.g., high benefits and low costs of smoking cessation) and their confidence in their ability to achieve desired outcomes (e.g., quitting self-efficacy). The results also imply that psychosocial approaches for smoking cessation with pregnant women should include therapeutic techniques to focus specifically on these mediators.

The study has certain limitations, including a modest sample size and a relatively high rate of attrition. Although we had a sufficient number of participants at baseline, follow-up data were only available from 187, 170, and 151 women at the third trimester prenatal, 1-month postnatal, and 5-month postnatal time-points, respectively. Thus, there is the possibility that the study was underpowered for the follow-up points. Recruiting and retaining underserved women into smoking cessation programs, particularly into intensive and temporally demanding interventions, has been recognized as a challenge in the literature (Katz et al., 2008; Paskett et al., 2008; Ussher et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2012).

The post hoc analyses showed that in the CBC group, compared to those who attended three or four sessions, women who completed only one or two sessions had high school or less education [χ2(1) = 7.36; p = .007]. Previous studies with similar underserved or pregnant populations show that lower educational attainment compounds the risk of smoking cessation counseling attrition (Borrelli et al., 2002; Leeman et al., 2006). This may be because less educated women are less aware of the risk of smoking during pregnancy and postpartum and thus are less motivated to make further efforts to complete smoking cessation intervention sessions. Less educated smokers may also experience limited future orientation and a greater tendency to fatalism, believing that it would be futile to enact health behavior change (Layte & Whelan, 2009).

An additional limitation involves potential sample bias due to the lack of first-trimester initiation of prenatal care among low-income pregnant women. We recruited women in their first trimester given the importance of smoking cessation early during pregnancy. However, low-income pregnant women have been found to be more likely to initiate prenatal care after the first trimester (Beeckman et al., 2010). Indeed, 41 % of women initially assessed for study eligibility were excluded from study participation because they were over 25 weeks gestation. Barriers to timely prenatal care use among low-income women include delay in obtaining government or private organization support coverage (e.g., Medi-Cal) (Egerter et al., 2002) and practical challenges such as child care, transportation, lack of time and support (Heaman et al., 2015).

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the few to develop and evaluate a theory-based smoking cessation intervention from pregnancy through the postpartum phase for underserved inner city women. This integration of the prepartum and postpartum smoking cessation program and the assessment of multiple follow-up outcomes prepartum and postpartum was informative and innovative. In addition, we conducted theory-based mediator analyses with longitudinal data that allowed us to observe the temporal interactions between hypothetical mediators and outcome variables. Further, this study collected biochemical verification of smoking status among the majority of participants (96 %) who reported being abstinent, which increases the accuracy of the cessation rates provided.

A key agenda for future research is to enhance access to, and retainment of, underserved pregnant and postpartum women for effective delivery of evidence-based programs. Proactive recruitment strategies, that include assessing the risks of smoking with a focus on child health during routine clinic visits and provision of referral information about clinical trials to all identified smokers, may improve recruitment rates among underserved women (Collins et al., 2011). Potentially effective retention strategies for low-income minority women include provision of financial and other incentives, regular updates of contact information, and emphasis on cultural sensitivity of research staff (El-Khorazaty et al., 2007).

In order to increase attendance and participation for eligible women in CBC programs, future interventions may need to highlight the adverse effects of smoking during pregnancy and postpartum, streamline the counseling content, and focus on facilitating perceptions of women’s personal control and their ability to change maladaptive behaviors. Of great promise, with the increasing prevalence of mobile phone and text messaging use among under-served inner city populations (Smith & Schatz, 2010), texting-based interventions may be useful to access these hard-to-reach populations. Since mobile text messaging interventions can be personalized, proactive, cost-effective, and easily disseminated, this delivery channel has great potential as an adjunct resource for future smoking cessation programs (Nasi et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2014a, b).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by American Cancer Society Grant TURSG 02-227-01, the National Institute of Health Grants RC1 CA145063 and R01 CA104979, and the Fox Chase Cancer Center Behavioral Research Core Facility P30 CA06927. The authors would like to thank Mary Anne Ryan and Deirdre Kurtz for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Minsun Lee, Suzanne M. Miller, Kuang-Yi Wen, Sui-kuen Azor Hui, Pagona Roussi and Enrique Hernandez declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Human and animal rights and Informed consent All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

References

- Bailey BA, Jones Cole L. Are obstetricians following best practice guidelines for addressing pregnancy smoking? Results from Northeast Tennessee. Southern Medicine Journal. 2009;102:894–899. doi: 10.1097/smj.0b013e3181aa579c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AS, Rothman AJ, Hertel AW, Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Finch EA, et al. Specifying the determinants of the initiation and maintenance of behavior change: An examination of self-efficacy, satisfaction, and smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2006;25:626–634. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman K, Louckx F, Putman K. Predisposing, enabling and pregnancy-related determinants of late initiation of prenatal care. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;15:1067–1075. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0652-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock BC, Papandonatos GD, de Dios MA, Abrams DB, Azam MM, Fagan M, et al. Tobacco cessation among low-income smokers: Motivational enhancement and nicotine patch treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16:413–422. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Hogan JW, Bock B, Pinto B, Roberts M, Marcus B. Predictors of quitting and dropout among women in a clinic based smoking cessation program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:22–27. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.16.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2013;10:CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Alexander S, Holland C, Arnold R, Landsittel D, Tulsky J, et al. Smoking is bad for babies: Obstetric care providers’ use of best practice smoking cessation counseling techniques. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2013;27:170–176. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110624-QUAL-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Wileyto EP, Hovell MF, Nair US, Jaffe K, Tolley NM, et al. Proactive recruitment predicts participant retention to end of treatment in a secondhand smoke reduction trial with low-income maternal smokers. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1:394–399. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yip T, Bolger N. A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:917–929. doi: 10.1177/0146167206287721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:80. [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, McBride C, Grothaus L, Lando H, Pirie P. Motivation for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:126–132. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas EA, Magnavita J, Beazoglou T, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando H, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a clinic-based counseling intervention tested in an ethnically diverse sample of pregnant smokers. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;64:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerter S, Bravemen P, Marchi K. Timing of insurance coverage and use of prenatal care among low-income women. Research and Practice. 2002;92:423–427. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, Subramanian S, Laryea HA, et al. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, Joseph JG, Subramanian S, Johnson AA, Blake SM, et al. An intervention to improve postpartum outcomes in African-American mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112:611–620. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181834b10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson AC, Arbour LT. Heavy smoking during pregnancy as a marker for other risk factors of adverse birth outcomes: A population-based study in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S, Dorfman S, Goldstein M, Gritz E, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependance. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T, Bailey W, Benowitz N, Curry S, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guidelines. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gadomski A, Adams L, Tallman N, Krupa N, Jenkins P. Effectiveness of a combined prenatal and postpartum smoking cessation program. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15:188–197. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler CW, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C, Memon A. Factors associated with smoking relapse in the postpartum period: An analysis of the child health surveillance system data in Southeast England. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15:904–909. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaman MI, Sward W, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Helewa ME, Morris H, et al. Barriers and facilitators related to use of prenatal care by inner-city women: Perceptions of health care providers. Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0431-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Fidler J, Mindell J, Feyerabend C, West R. Assessing smoking status in children adolescents and adults: Cotinine cut-points revisited. Addiction. 2008;103:1553–1561. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JG, El-Mohandes AA, Kiely M, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG, Johnson AA, et al. Reducing psychosocial and behavioral pregnancy risk factors: Results of a randomized clinical trial among high-risk pregnant african american women. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1053–1061. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz KS, Blake SM, Milligan RA, Aharps PW, White DB, Rodan MF, et al. The design, implementation and acceptability of an integrated intervention to address multiple behavioral and psychosocial risk factors among pregnant African American women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layte R, Whelan CT. Explaining social class inequalities in smoking: The role of education, self-efficacy, and deprivation. European Sociological Review. 2009;25:399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Quiles ZN, Molinelli LA, Donna MT, Beth LN, Arthur JG, et al. Attrition in a multi-component smoking cessation study for females. Tob Induc Dis. 2006;3:59–71. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-3-2-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Cho YI, Crittenden KS, Dolecek TA. A path model of smoking cessation in women smokers of low socio-economic status. Health Education Research. 2007;22:747–756. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi C, Crittenden KS, Warnecke R, Engler J, Cho YI, Shaligram C. Evaluation of a motivational smoking cessation intervention for women in public health clinics. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:51–60. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Hui SA, Wen K, Scarpato J, Zhu F, Buzaglo J, et al. Tailored telephone counseling to improve adherence to follow-up regimens after an abnormal pap smear among minority, underserved women. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93:488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Shoda Y, Hurley K. Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: Breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:70–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PD. How can more smoking suspension during pregnancy become lifelong abstinence? Lessons learned about predictors, interventions, and gaps in our accumulated knowledge. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:S217–S238. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PD, DiClemente C, Bartholomew L. Theory and context and project PANDA: A program to help postpartum women stay off cigarettes. In: Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb H, editors. Designing theory and evidence-based health promotion programs. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishers; 2000. pp. 453–477. [Google Scholar]

- Nasi G, Cucciniello M, Guerrazzi C. The role of mobile technologies in health care processes: The case of cancer supportive care. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2015;17:e26. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park ER, Chang Y, Quinn V, Regan S, Cohen L, Viguera A, et al. The association of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms and postpartum relapse to smoking: A longitudinal study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:707–714. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett ED, Reeves KW, McLaughlin JM, Katz ML, McAlearney AS, Ruffin MT, et al. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: The Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities experience. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29:847–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletsch PK, Morgan S, Pieper AF. Context and beliefs about smoking and smoking cessation. MCN; American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2003;28:320–325. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaros C, Pajolek H, Park ER. The role of negative affect management in postpartum relapse to smoking. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2012;15:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall E, Marshall JR, Graham S, Brasure J. High-risk health behaviors associated with various dietary patterns. Nutrition and Cancer. 1991;16:135–151. doi: 10.1080/01635589109514151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Costello TJ, Li Y, et al. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among diverse low-income women: A randomized clinical trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:326–335. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roske K, Schumann A, Hannover W, Grempler J, Thyrian JR, Rumpf HJ, et al. Postpartum smoking cessation and relapse prevention intervention: A structural equation modeling application to behavioral and non-behavioral outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:556–568. doi: 10.1177/1359105308088528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychology. 2000;19:64–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Huy C, Schutz J, Diehl K. Smoking cessation during pregnancy: A systematic literature review. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29:81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll RA, Rothman RL, Wielt DB, Lerman C, Pedri H, Wang H, et al. A randomized pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus basic health education for smoking cessation among cancer patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:1–11. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Schatz BR. Feasibility of mobile phone-based management of chronic illness. AMIA annual symposium proceedings; 2010. pp. 757–761. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran T, Reeder A, Funke L, Richmond N. Association between smoking cessation interventions during prenatal care and postpartum relapse: Results from 2004 to 2008 multi-state PRAMS data. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17:1269–1276. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher M, Etter JF, West R. Perceived barriers to and benefits of attending a stop smoking course during pregnancy. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;61:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Brandenburg N. Decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:1279–1289. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen KY, Miller SM, Kilby L, Fleisher L, Belton TD, Roy G, et al. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among inner city women: Development of a theory-based and evidence-guided text messaging intervention. JMIR Research Protocols. 2014a;3:e20. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen KY, Miller SM, Lazev A, Fang Z, Hernandez E. Predictors of smoking cessation counseling adherence in a socioeconomically disadvantaged sample of pregnant women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2012;23:1222–1238. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen KY, Miller SM, Roussi P, Belton TD, Baman J, Kilby L, et al. A content analysis of self-reported barriers and facilitators to preventing postpartum smoking relapse among a sample of current and former smokers in an underserved population. Health Education Research. 2014b doi: 10.1093/her/cyu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor R, Clark J, Cleary S, Davis A, Thorn S, Abroms L, et al. Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation and Reduction in Pregnancy Treatment (SCRIPT) Dissemination Project: A science to prenatal care practice partnership. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014;18:180–190. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor R, Woodby L, Miller T, Hardin M. Effectiveness of Smoking Cessation and Reduction in Pregnancy Treatment (SCRIPT) methods in Medicaid-supported prenatal care: Trial III. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38:412–422. doi: 10.1177/1090198110382503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]