Abstract

Frustration is a normative affective response with adaptive value in motivating behavior. However, excessive anger in response to frustration characterizes multiple forms of externalizing psychopathology. How a given trait subserves both normative and pathological behavioral profiles is not entirely clear. One hypothesis is that the magnitude of response to frustration differentiates normative versus maladaptive reactivity. Disproportionate increases in arousal in response to frustration may exceed normal regulatory capacity, thus precipitating aggressive or antisocial responses. Alternatively, pathology may arise when reactivity to frustration interferes with other cognitive systems, impairing the individual’s ability to respond to frustration adaptively. In this paper we examine these two hypotheses in a sample of kindergarten children. First we examine whether children with conduct problems (CP; n = 105) are differentiated from comparison children (n = 135) with regard to magnitude of autonomic reactivity (cardiac and electrodermal) across a task that includes a frustrative non-reward block flanked by two reward blocks. Second we examine whether cognitive processing, as reflected by magnitude of the P3b brain response, is disrupted in the context of frustrative non-reward. Results indicate no differences in skin conductance, but a greater increase in heart rate during the frustration block among children in the CP group. Additionally, the CP group was characterized by a pronounced decrement in P3b amplitude during the frustration condition compared with both reward conditions. No interaction between cardiac and P3b measures was observed, suggesting that each system independently reflects a greater sensitivity to frustration in association with externalizing symptom severity.

Keywords: affective reactivity, antisocial, conduct problems, P3b, motivation

Theoretical models of affective neuroscience focus on the evolutionary function of emotions, the most basic of which are not only consistently evident across cultures but across a broad range of mammalian species (e.g. Panksepp, 2012). Emotions can be viewed as the activation of primary motivational drives to pursue rewards, defend safety, or withdraw from uncertainty (Harkness, Reynolds, & Lilienfeld, 2014). However, extreme, chronic, or contextually dissonant emotions are viewed as the foundation of many major mental health disorders. Thus research is needed to understand how affective processes that support basic behavioral systems can lead to psychopathology. The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) generated by the National Institute of Mental Health identifies 5 distinct subconstructs of negative affect believed to contribute to a range of mental health disorders from depression to aggression. Among these subconstructs is “frustrative nonreward”, defined as the removal of, or impediment to obtaining, a previously available award.

Frustrative Non-Reward

The omission of an expected reward results in a decrease in striatal dopamine that signals the discrepancy between the actual versus predicted outcome, and facilitates an adaptive learning response (Porter-Stransky, Seiler, Day, & Aragona, 2013). Theoretical models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) posit that deficient processing of non-reward cues contributes to the resistance of behavioral symptoms to normal operant conditioning (Sagvolden, Johansen, Aase, & Russell, 2005). Imaging data provides support for this model, demonstrating that adolescents across multiple externalizing disorders, including ADHD and conduct disorder (CD), fail to show changes in neural activation from rewarded to non-rewarded blocks, in contrast to their normally developing peers (Gatzke-Kopp et al., 2009). These findings suggest that individuals with externalizing disorders have difficulty in extinguishing previously rewarded behaviors, but do not address the affective domain of externalizing behaviors. Negative affectivity is proposed to be a key component of externalizing psychopathology, particularly conduct disorder, and thus further attention is warranted to the psychophysiological responses to non-reward (Eckhardt & Kassinove, 1998; Hubbard et al., 2002; Roberton, Daffern, & Bucks, 2012; Sanderlin, 2001).

In addition to the effects on adaptive learning, reward omission, or frustration, is typically accompanied by an affective reaction of anger, which is associated with patterns of neural activity distinct from those that mediate learning. Omission of reward is associated with greater activation in the anterior cingulate, and greater right-lateralized activation in the anterior insula and ventral prefrontal cortex (Abler, Walter, & Erk, 2005). These regions have documented roles in the processing of affect, with right-lateralized regions thought to contribute to negative affect in particular (Davidson & Irwin, 1999). In addition, regions such as the dorsal anterior cingulate and anterior insula are integrally involved in translating cognitive representations of affect into physiological arousal through autonomic activation (Critchley, 2005). Thus activation of these neural regions likely contributes to the visceral responses to frustration. Sympathetic activation (skin conductance) has been shown to be reactive to conditions of perceived unfairness, particularly when the unfairness is relevant to personal goals (Civai, Corradi-Dell’Acqua, Gamer, & Rumiati, 2010).

Anger in the face of frustrative non-reward is a normative affective response, and the associated increase in arousal facilitates behavioral activation needed to overcome obstacles to goal achievement (Dixon, MacLaren, Jarick, Fugelsand, & Harrigan, 2013; Otis & Ley, 1993). The individual’s perception of this behavioral activation can manifest in prosocial (e.g. determination) or antisocial (e.g. anger) states (Harmon-Jones, Schmeichel, Mennitt, & Harmon-Jones, 2011). Anger is considered a key factor in behaviors such as reactive aggression, which characterize several clinical conditions. In adults, borderline personality disorder (BPD) is viewed as resulting from intense and dysregulated negative affect in response to frustration that can include physical violence and suicidal gestures (Harkness et al., 2014; Linehan & Dexter-Mazza, 2008). In children these behaviors are best captured in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (CD) in which intense negative affect can lead to pathological non-compliance, fighting behaviors, and destruction of property (Cappadocia, Desrocher, Pepler & Schroeder, 2009).

Disproportionate Affective Arousal

It is possible that these clinical conditions are distinguished from normative responses to frustration by the magnitude of affective distress. In the context of acute stress, neural processing in limbic regions becomes prioritized to facilitate sensitivity to affective information (Oei et al., 2012). This re-prioritization can come at the expense of activation in the dorsolateral cortex, a region involved in working memory and other executive systems (Krause-Utz et al., 2012). Researchers have found that individuals with BPD show a greater increase in amygdala activation than controls when presented with emotional distractors during a working memory task, as well as a significant increase in reaction times, indicating greater interference of affective arousal with cognitive processing (Krause-Utz et al., 2012). Thus more extreme reactions to frustration may effectively re-prioritize neural processing away from systems engaged in regulatory control. Interestingly, a recent study examining the mechanisms of response to an intervention focused on anger management among men with trauma histories found that successful reduction in anger symptoms was mediated by increasing skills in reducing physiological arousal and not related to cognitive-based coping skills (Mackintosh, Morland, Frueh, Greene, & Rosen, 2014). These findings support a model whereby psychopathology might arise in the context of hypersensitivity toward affective arousal that competes with regulatory systems.

Some evidence suggests that children with externalizing tendencies react with greater degrees of sympathetic arousal when frustrated. Among a sample of 2nd grade children, high levels of teacher-rated reactive aggression were associated with greater increases in both heart rate and skin conductance in response to an anger-inducing game in which the child loses to another child who has cheated (Hubbard et al., 2004). Further research found that the tendency for individuals with a history of aggression to be more physiologically reactive was specific to conditions of anger compared to other forms of negative affect (Wang, Guo, You, & Gao, 2007).

Disrupted Cognitive Control

From the behavioral surface, it is difficult to determine exactly what mechanisms underlie the tendency of individuals with externalizing disorders to resort to aggressive behavioral responses to this type of emotional arousal. Because anger in response to frustration is a normal emotion, it is not clear whether it is the affective experience (e.g. anger), or the behavioral response to it (e.g. aggression), that differentiates individuals with externalizing problems. In other words, individuals with externalizing symptoms could have stronger anger reactions wherein the magnitude of physiological arousal exceeds that of typical individuals, or they could have comparable levels of affective arousal to frustration, but lack appropriate cognitive resources to direct their increased behavioral activation in socially appropriate and adaptive ways. Although not mutually exclusive, each pathway lends itself to specific hypotheses.

As mentioned above, frustration is a common experience, and most individuals encounter frustrating or goal blocking situations on a regular basis. One of the primary goals of development is learning to regulate responses to frustration in socially appropriate ways. For instance, imagine a child playing with her favorite toy when her older sibling comes along and snatches it from her hands. Anger would be a normal and fully appropriate emotional response. The objective would be for the child to resist any inclination to respond aggressively but employ a more prosocial strategy, such as appealing to an adult for help. Children with externalizing behaviors characteristically fail to engage the non-aggressive response. Recent theories have posited that this results from disruptions in cognitive function, specifically in motivationally salient contexts. Individuals with externalizing behavior problems appear to prioritize motivationally relevant information for attentional processing, which detracts from executive function resources needed to regulate arousal (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2012). In a small study of 27 children treated for externalizing behavior disorders, those who showed clinical improvement in response to treatment also showed improvement in cortical brain potentials specific to the temporal window of inhibitory control from pretest to posttest (Lewis et al., 2008). The authors interpret this change as reflecting improvement in cognitive control rather than a decrease in emotional arousal. This perspective highlights the importance of examining cognitive processing within affective contexts.

The study of cognition x affect interactions is facilitated by the use of event-related potential (ERP) studies in which individual trials are embedded within affective blocks in order to examine the state-dependent effects of context on cognitive processing. Studies of this type have reported an association between context-specific effects on ERP amplitudes and symptoms of psychopathology, suggesting that the extent to which affect disrupts cognitive processing may be a unique feature that discriminates between normative and pathological affective responses. One study of children diagnosed with bipolar disorder reported a context-specific effect of frustration on P3b amplitude during an attention task that was not present in typically developing children, or those with other mood disorders (Rich et al., 2007). Additional studies focusing on externalizing and internalizing symptoms have been conducted with go/no-go paradigms embedded into an affective block design containing blocks of reward and non-reward trials (Lewis, Lamm, Segalowitz, Stieben, & Zelazo, 2006; Stieben et al., 2007). In one study comparing groups with externalizing problems, internalizing problems, comorbid profiles, and typically developing children, differential patterns of ERP amplitudes were found to be dependent on the affective context in which they were assessed. Reduced ERN amplitude in children with externalizing symptoms was only evident when assessed prior to the frustration condition, and enhanced N2 amplitude in children with comorbid symptoms was only evident when assessed post-frustration (Stieben et al., 2007). These results demonstrate the susceptibility of discrete cognitive processes to manipulations of affective state.

One of the most extensively examined ERP components associated with externalizing disorders is the P3b, a posteriorly located component thought to reflect attentional allocation (Polich, 2007). Research has reported reduced amplitude in the P3b event-related potential across a broad range of externalizing phenotypes (Euser et al., 2012; Gao & Raine, 2009; Iacono, Carlson, Malone, & McGue, 2002; Iacono & Malone, 2011; Patrick et al., 2006; Polich, Pollock, & Bloom, 1994). Lower P3b amplitude measured in childhood is associated with both concurrent and future levels of externalizing symptoms (Ehlers, Wall, Garcia-Andrade, & Phillips, 2001; Gao, Raine, Venables, & Mednick, 2013), and lower P3b amplitude characterizes children with high family risk for substance use disorders (Begleiter, Porjesz, Rawlings, & Eckardt, 1987; Viana-Wackermann, Furtado, Esser, Schmidt, & Laucht, 2007). Cognitive research indicates that P3b amplitude is associated with attentional allocation to stimuli, and individual differences in amplitude are associated with a range of cognitive skills (Hillman et al., 2012; Polich, 2007; Russo, De Pascalis, Varriale, & Barratt, 2008). However, little research has examined the effects of affective manipulations on P3b amplitude. One study found that greater self-reported negative affect during a frustration condition was associated with increased frontal P3 amplitude during the frustration portion of the task in a sample of typically developing 10–16 year old children (Lewis et al., 2006), suggesting that children in this range can harness emotional arousal toward increasing cognitive allocation to task completion, similar to the concept of determination (Harmon Jones et al., 2011). It is possible that children with externalizing problems are not able to show this type of cognitive enhancement in the face of frustration. Thus examination of state-related changes in P3b may provide further insight into the types of cognitive systems relevant for understanding how reactivity to frustration predisposes toward externalizing behavioral outcomes.

Present Study

In this study we examine psychophysiological responding to a frustrative non-reward condition to assess whether externalizing problems are associated with greater affective reactivity to frustration, and/or deficient cognitive processing in the context of frustration. Children identified by their kindergarten teachers as displaying externalizing behavior problems were compared with typically developing children during a cognitive task with reward and frustration conditions. We hypothesized that if externalizing problems are associated with disproportionate affective responses, sympathetic reactivity would be amplified during the frustration block among the children with externalizing symptoms compared to their peers. If externalizing problems are associated with deficits in regulatory control, we hypothesize that P3b amplitude would decrease during the frustration block among children in the externalizing group. We then examined whether these two processes are independent, or if cognitive disruption mediates or moderates an association between affective reactivity and externalizing problems. Finally, we predicted that responses to frustrative non-reward would be specific to the negative affect that characterizes externalizing behavior problems and not associated with internalizing symptom comorbidity, despite internalizing disorders also being characterized by greater negative affectivity.

Method

Data were drawn from a longitudinal clinical trial of a multi-component intervention for children with early onset aggression. Only data from the pre-intervention assessment will be presented here. Participants were drawn from all elementary schools within a single urban school district in which 79% of students are classified as low-income (qualifying for free or reduced price school meals), the majority of households are headed by a single female (69%), and 79% of parents are estimated to have no more than a high school education. Regional statistics indicate that property crimes are twice as high and violent crimes are 4.5 times as high as comparable statistics for the entire state. Overall, the entire sample is presumed to be of high demographic risk.

Participants

All kindergarten teachers within the participating school district completed a 10-item aggressive behavior rating scale for each child in their class during the fall of 2008 (Cohort I) and 2009 (Cohort II). Items were drawn from the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation-Revised (TOCA-R; Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991) and included descriptive statements such as “Gets in many fights” and “Cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others,” that were rated on a 6-point Likert scale. This brief screening scale was used to identify children at higher risk for aggressive behavior problems, to be recruited into the clinical component of the study. More detail regarding sample recruitment can be found in Gatzke-Kopp, Greenberg, Fortunato & Coccia, 2012. A total of 207 children screened high in aggression were enrolled in the study and an additional 132 children selected from the lowest quartile of aggression and matched for sex and classroom with children in the high aggression group were recruited (total n = 339).

Psychopathology symptoms

For all children enrolled in the study, teachers were asked to complete more extensive behavioral ratings, including the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997), approximately 3 months after the initial screening but prior to the start of the intervention. This assessment allowed for more thorough information about the child and better differentiated between stable traits and transient behavior problems limited to the start of school. Teachers who provided ratings received a $15 gift card as compensation for their time. Some teachers did not complete these ratings resulting in missing information for 40 of the children enrolled in the study. Teachers who did not provide ratings failed to do so for all participant children in their classrooms and thus missingness was equivalent with regard to original screening status.

Children’s externalizing status was determined using the conduct problems subscale of the SDQ. This scale consists of 5 items assessing a range of antisocial and oppositional behaviors including “often loses temper”, “often fights or bullies other children”, and “often lies and cheats”. Each of the 5 items is rated on a scale of 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true) and 2 (certainly true). Across the full sample, total scores ranged from 0–10 (M = 2.46, SD = 2.80). Children were classified into the conduct problems (CP) group if they had at least one rating of “certainly true” or at least two ratings of “somewhat true”. Children were classified into the comparison (non-conduct problem) group if they scored no higher than a 1 (somewhat true) on no more than one symptom.

Teachers also completed the emotional symptoms (ES) subscale of the SDQ which consists of 5 items that assess a range of internalizing symptoms including “many worries or seems worried”, “unhappy depressed or tearful”, and “nervous or clingy in new situations, easily loses confidence”. Scores for the total sample ranged from 0–10 (M = 1.86, SD = 2.28). Table 1 reports the mean levels of ES and CP for each CP group. Children in the CP group did have significantly higher ES scores. In order to examine whether reactivity to frustration is specific to externalizing or applies to internalizing symptoms as well, children were classified into ES problems groups along the same criterion as used for the CP groups.

Table 1.

Sample distributions for the dependent cognitive and psychopathological variables.

| Conduct Problems (n = 105) | Non-Conduct Problems (n = 135) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AgeK | 5. 64 (.37) | 5.65 (.32) | F (1, 239) = .13 |

| % Males | 66% | 61% | Χ2 (1) = 0.63 |

| % African American | 67% | 65% | Χ2 (1) = 0.06 |

| Emotional Symptoms | 2.15 (2.40) | 1.34 (1.92) | F (1, 239) = 8.45* |

| Conduct Problems | 4.74 (2.37) | .27 (.45) | F (1, 239) = 460.03* |

| Mean Response Time | 518.79 (53.42) | 510.21 (56.33) | F (1, 239) = 1.41 |

| Response Accuracy | .65 (.07) | .65(.08) | F (1, 239) = .30 |

| Accuracy reactivity | .10 (.06) | .11 (.05) | F (1, 237) = .40 |

| P3b reactivity | 1.68 (4.36) | .17 (4.85) | F (1, 234) = 6.13* |

| HR reactivity | −1.38 (5.84) | .82 (5.00) | F (1, 200) = 8.24* |

| SCR reactivity | −.04 (1.28) | .21 (1.14) | F (1, 199) = 2.11 |

Note. AgeK is computed as age at kindergarten entry. Mean response time is measured in ms. Response accuracy is computed as the average of errors on go-trials and no-go trials. Reactivity is computed as the quadratic term across the 3 task blocks (i.e., the frustration block subtracted from the average of the two flanking reward blocks). Positive values indicate a greater U shape, with lower values during the frustration block compared to the flanking reward blocks. Negative values indicate a greater inverted-U shape with higher values during the frustration block.

p < .01.

Sample

Of the 299 participants with teacher-report data, 38 did not have data from the go/no-go task for one of the following reasons: refused participation in the physiological assessment (n = 1), was not assessed (e.g. moved, excessive absence; n = 27), equipment failure (n = 2), corrupt data file (n = 3), experimenter error (n = 5). An additional 21 participants were excluded from analyses because they were deemed to have failed to engage the task appropriately (additional details regarding data loss are provided below). Of the 240 available participants, 135 were classified into the comparison group and 105 were classified into the CP group. A total of 150 children were classified as having no ES and 90 were classified as having ES. Table 1 reports demographic characteristics of the comparison and CP groups. These groups did not differ in age at kindergarten entry F (1, 239) = .13, p = .72. However, the groups did differ at the age of psychophysiological assessment, as individuals selected for the clinical intervention trial were prioritized for baseline assessments, F (1, 239) = 5.83, p = .02. On average, children in the comparison group were, M = 6.12 (SD = .35) years at the time of psychophysiological assessment and children in the CP group were, M = 6.00 (SD = .41) years. Groups did not differ with regard to sex, Χ2 (1) = .63, p = .43 or race, Χ2 (1) = .06, p = .81.

Neurophysiological Assessments

Psychophysiological equipment was installed into a recreational vehicle (RV) and driven to each school to conduct assessments. This maximized consistency of the testing environment across the school sites while minimizing burden on parents. In order to reduce apprehension, the RV was decorated with a space theme depicting a familiar cartoon character in an astronaut suit. At the start of each school year all kindergarten classes toured the RV with their teacher to ensure that children were familiar with the vehicle. On the day of the assessment, RAs met children at their classroom and escorted them to the bathroom to wash their hands prior to arriving at the RV. The tasks were explained to the children verbally, who were then asked to provide verbal assent. Children who asked to return were escorted back promptly, but approached on a separate day and offered the possibility to participate again. Most children who were initially apprehensive eagerly participated on the second day.

During the set up process, children were provided with a coloring page and crayons and asked to draw a picture. This was used as an assessment of the child’s dominant hand, which the RAs made note of, ensuring that electrodes were placed on the non-dominant hand. Children were seated while the RAs applied the physiological electrodes for the event-related potential, cardiac, and electrodermal measures described below.

Protocol

Assessments took place with the child seated at a table with a computer monitor and response box. One RA was positioned behind the child where s/he monitored data recording from two laptops. The second RA sat on a bench to the right of the child but did not interact with the child unless necessary. The RA explained that the child was now going to “travel through space” to a planet where s/he would play a game. The child was instructed to sit very still during the travel, which consisted of a 2 minute baseline recording during which a moving star-field video was played on the computer monitor. The children were then asked to play a go/no-go game embedded in an affective context (described below) for approximately 12 minutes, followed by a break and a subsequent task involving emotional film clips that will not be reported in this paper.

Go/No-go

The task used was patterned after a go/nogo paradigm first reported by Lewis et al. (2006) and Stieben et al. (2007). This task consists of individual events embedded within blocks that establish an affective context within which cognitive processing occurs. In order to be appealing and appropriate for kindergarten children, stimuli consisted of a series of cartoon character images that children were told were “alien critters” that they should “zap” by pressing the response box button whenever one appeared. The children were instructed that they were not allowed to zap the same character twice in a row, so they should resist hitting the button (no-go condition) if the same critter popped up who was just zapped.

RAs explained the task to the children with the use of full page color images to familiarize them with the character stimuli as well as the large red square that would appear around the stimuli when they made a mistake. After the verbal and visual instructions, children were asked to practice the game before beginning the task. RAs observed the child’s performance and the computer calculated the child’s error rate on no-go trials after the practice session. In order to assess error-related negativity (data not presented here), error rates were targeted to be between 40–60% on no-go trials. If the child’s error rate was outside of this range after the practice session RAs administered additional practice sessions as needed, with appropriate adjustments in presentation speed to facilitate decreased or increased errors. During the task, a dynamic computer algorithm tracked no-go error rates; when error rates exceeded 60% the program slowed the trial presentation rate, and when error rates fell below 40% the program speeded the trial presentation rate in order to increase the consistency of task performance across participants. Adjustments in presentation rate were made in 50ms increments. Presentation rate ranged between 435–535 ms (M = 515) from the time of response to the next stimulus presentation.

Across the task, observed no-go error rates ranged from 3%–100% (M = 39.64, SD = 16.98). The finding that the mean error rate was on the lower bound of the targeted error window indicates that children generally performed well on the task, and that for some children there was an improvement in performance across the task that exceeded the incremental changes in difficulty induced by the dynamic algorithm. As indicated above, 21 (8% of participants) children had an error rate in excess of 60%. Participants who exceeded the targeted no-go error maximum had lower error rates on go-trials compared with those within the targeted no-go error limit, F (260) = 9.06, p = .003. This was deemed to be indicative of lack of effort to withhold responses (e.g. non-contingent button pressing). Because this would likely affect the validity of the entire task for that child, those participants were excluded from analyses. Participants who were excluded were slightly younger on average at the time of assessment, F (1, 260) = 3.05, p = .08. Excluded participants did not differ with regard to original aggression screening score, F (260) = .05, p = .82, or conduct problem symptoms, F (1, 260) = .16, p = .69.

An overall measure of accuracy was computed for each participant separately by blocks. Accuracy was defined as the average of the percentage of correct go and correct no-go trials. The combined go/no-go metric corrects for cases in which high accuracy in go-trials is due to habitual responding, which would be consequently associated with low accuracy in no-go trials (see Lewis et al., 2006). Across the sample accuracy for each block ranged from (A) 42% – 89% (M = 67.32, SD = 8.83), (B) 40% – 88% (M = 58.06, SD = 8.37), and (C) 37% – 93% (M = 69.97, SD = 10.01).

Children were informed that during the game they would be earning points for their performance and that if they got enough points they would win a prize. No specific criterion of point value was associated with earning a prize so children would be motivated to maximize points. Prizes were shown to the child ahead of time and consisted of goody bags filled with small toys, stickers, and other items. Because the age of children in this sample was younger than that for whom the original task was designed, additional modifications were made to ensure adequate processing of the incentive component of the task. Accumulated points, which were displayed approximately every 10 trials, were depicted non-numerically to eliminate potential individual differences in basic numeric comprehension at this age. During each feedback session, a thermometer was displayed that identified the current total points. In addition, a large cartoon happy face displaying a “thumbs-up” appeared if children had earned points since the last feedback or a frowning face displaying a “thumbs-down” if points had been lost since the last feedback.

The task was administered in three blocks. In the first block (A), the algorithm awarding points strongly favored correct responses and weakly punished incorrect responses, thus resulting in a rapid accumulation of points. In the second block (B), this algorithm was reversed, resulting in a loss of points regardless of equivalent performance, thus representing a frustrative condition where the participant’s objective (winning points to get the prize) is impeded. The final block (C) employed the same algorithm as Block A and thus all participants ended the game with enough points to win the prize. Participants were given a 30-s break between blocks. The entire task lasted approximately 12 min.

Physiological Data Processing

Autonomic psychophysiology

Cardiac and skin conductance measures were collected continuously with a sampling frequency of 500 Hz using the Biolab 2.4 acquisition software (Mindware, Westerville, OH). Skin conductance activity was measured as the conductance between two disposable pre-gelled electrodes placed on the palm of the child’s non-dominant hand. ECG was recorded from three disposable, pre-jelled, electrodes placed over the distal right collar bone, lower left rib, and lower right rib. Of the 240 participants with task data, 38 were missing skin conductance data due to equipment failure and 30 were missing cardiac data due to equipment failure or experimenter error.

Skin conductance activity

Data were analyzed using software from Mindware Technologies (EDA v. 3.0 – 3.0.15) with gain set at 10 μS/Volt, and bandpass filtered between .05 and 10 Hz. Data were visually inspected by trained RAs to identify and reject artifactual segments. Data were quantified in 30-s epochs across the task as the number of skin conductance responses (SCRs), defined as a .05 μS increase. Averages were computed for each of the 3 blocks.

Heart rate

Data were scored using Mindware software (HRV v. 3.0–3.0.15), which identifies the peak of each R wave and estimates heart rate as the average number of beats/min within each epoch. Cardiac waves were inspected by trained RAs to identify and correct erroneously identified R peaks. Heart rate was quantified in 30-s epochs and averages were computed for each of the 3 blocks.

EEG

EEG was recorded using an extended 10–20 montage with a 32-channel elastic stretch BioSemi headcap with the Active Two BioSemi system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Head circumference was measured to identify cap size. Two additional electrodes were placed on the left and right mastoids, and four additional facial electrodes were used to measure eye movement. Vertical eye movements were measured from electrodes placed on the infra-orbital ridges centered under the pupils of both eyes and corresponding supra-orbital electrodes embedded within the cap. Horizontal eye movement was measured from electrodes placed approximately 1 cm outside the participants’ right and left outer canthi. Data were recorded at 512 Hz with Actiview Software, v8.0.

P3b

Data were post-processed using Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0 and re-referenced to the average of all sites. EEG data were strongly affected by slow frequency power in the delta band, considered typical of young children and conceptualized as a marker of developmental immaturity (Somsen, van’t Klooster, van der Molen, van Leeuwen, & Licht, 1997; Yordanova & Kolev, 2008). In order to reduce the impact of the delta frequency noise and maximize the ability to detect individual differences in P3b amplitude in response to the experimental paradigm, some research with young children employs a 1 to 30 Hz bandpass filter (Lewis et al., 2006; Yordanova & Kolev, 2008). This setting mitigates the impact of excess very-low delta while preserving power in the delta and theta frequencies thought to contribute predominantly to P3b amplitude, and is associated with the cognitive ability to encode stimuli (Klimesch, 1999).

Participants completed a total of 330 trials, 68% of which were classified as go-trials. Repetitions (no-go condition) occurred on 32% of the trials. A total of 45 different character stimuli were used, thus each stimulus occurred 2% of the time, making each stimulus rare. Success on the task requires participants to attend actively to each go-stimulus for comparison with the subsequent trial. Unlike target stimuli in perceptual oddball tasks (e.g. auditory tones), the target stimuli in the present task did not involve objectively salient characteristics that would be expected to automatically capture attention and thus reliably elicit a large P3b response across all participants. Therefore, higher P3b amplitudes to go trials in this task are presumed to be a function of subjectively determined salience, and thus reflect sustained attention allocation, whereas lower P3b amplitudes reflect a failure to dedicate sufficient attentional resources to the task.

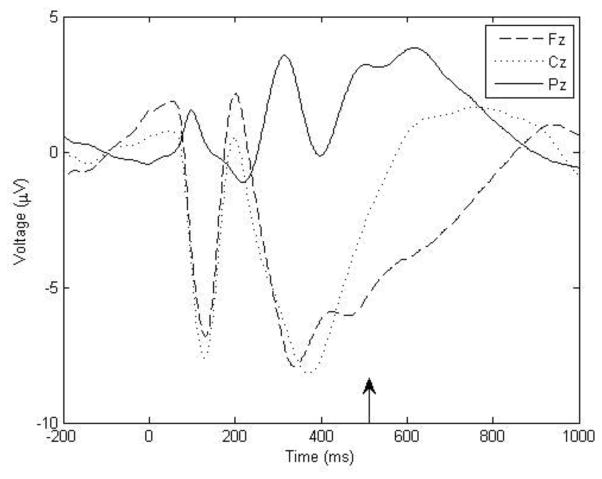

Correct responses on go trials, defined as those in which the child responded to the stimulus between 100 and 1,000 ms after stimulus onset, were segmented from −200 to 1,000 ms relative to stimulus onset. Trials were baseline-corrected to the mean amplitude across the 200 ms prior to stimulus onset and corrections were made for eye blink artifacts using the Gratton and Coles algorithm, as implemented by Brain Vision Analyzer 2.0 (Gratton, Coles, & Donchin, 1983). Any trials with a voltage step of more than 100 μV between sampling points or a voltage reading outside the range of −75 μV to 75 μV was marked as artifactual and removed from the analysis. Average waveforms were examined at the midline electrodes Fz, Cz, and Pz and are illustrated in Figure 1. Consistent with previous studies (see Szuromi, Czobor, Komlosi, & Bitter, 2011 for review) amplitude appeared maximal at the Pz site in the time window associated with P3b. The average response time for the entire sample was 509 ms (SD = 55 ms). Individual average response times ranged from 332 ms to 680 ms post stimulus onset. In order to mitigate effects of intra-individual variability in latency (Luck, 2005), a mean voltage was computed in the temporal window from 500 to 700 ms post-stimulus, consistent with the location of the peak in the average waveform (see Figure 1) as well as with previous studies in children (Pfueller et al., 2011; Thomas & Nelson, 1996).

Figure 1.

Stimulus presentation occurred at the zero point along the time axis. P3b was defined as the average voltage in the 500 to 700 ms window at the Pz electrode site.

Grand-average waveform of correct go-trials at the midline electrodes. The vertical arrow indicates the average response time.

Across the task, participants had an average of 147.3 trials in which an appropriate go response was executed (SD = 36.7). After artifact rejection, the number of usable P3b trials for each block were (A) M = 38.5 (SD = 14.6), ranging from 0–67 (B) M = 33.2 (SD = 13.4), ranging from 0 – 63 (C) M = 40.6 (SD = 16.1), ranging from 0 – 71. Participants who had fewer than 3 usable trials in a given block were excluded for that block; (A) n = 5, (B) n = 6, (C) n = 5. The number of usable trials within each block was not correlated with P3b amplitude for that, or any other block (all p’s > .27), and groups did not differ in the number of artifact-free trials available for analysis in any of the 3 blocks (all p’s > .26).

Data Analysis

Group differences in task block effects were assessed using the MIXED procedure in SAS 9.3 to conduct separate linear mixed models predicting accuracy, skin conductance, heart rate, and P3b amplitude. Various repeated-measures covariance structures were tested for each dependent variable using a baseline model with task block as the only predictor. The tested covariance structures included compound symmetry (the usual assumption of repeated-measured ANOVA), first-order autoregressive, Toeplitz, and unstructured, as well as heterogenous-variance versions of each of these covariance structures. The best-fitting repeated-measures covariance structure for each dependent variable was selected using relative model fit statistics, and this structure was used in all subsequent models for that dependent variable.

For the main analyses, task block was entered as a categorical within-subjects effect, CP group was entered as a categorical between-subjects effect, and the group x block interaction was tested to assess whether the effect of task block varied between the high and low CP groups. In addition, the hypothesized effect of reactivity to frustration was examined as the contrast between the frustration block (B), and the average of the two reward blocks (A and C). For each model a second analysis was conducted in which ES group, ES x block, ES x CP, and the three-way interaction, ES x CP x block were added to the model. These analyses evaluated whether the predicted group x block interactions are unique to externalizing symptoms as hypothesized, or whether internalizing symptoms are associated with a similar pattern of effects. These analyses further examine whether externalizing and internalizing symptom comorbidity is associated with reactivity to frustration. For each model, potential covariates were examined for statistical significance. Age at the time of the physiological assessment was not associated with any of the physiological variables or with accuracy, and was therefore not included as a covariate. Males had significantly higher skin conductance and higher accuracy across the task than females, and so sex was included as a covariate in those models. As previously observed, racial groups differed in skin conductance activity across the task and so a dichotomous variable for race (African American or other) was also included as a covariate in the model examining skin conductance (Wesley & Maibach, 2003).

Following the analyses of group x block effects for heart rate, skin conductance, and P3b amplitude considered separately, potential mediating and moderating effects of reactivity in these different physiological systems in predicting conduct problems were examined using linear regression models. Reactivity to frustration was quantified for each physiological system by subtracting the value during the frustration block (Block B) from the average value of the 2 reward blocks (Blocks A and C). Positive values indicate a greater U-shaped function with levels lowest during the middle (frustration) block, and negative values indicate that levels are higher during the frustration block.

Results

Task Performance

Based on relative model fit criteria, a heterogeneous Toeplitz covariance structure was selected for modeling response accuracy across the three task blocks. The linear mixed model with CP group, block, and group x block effects, including sex as a covariate, indicated a strong effect for block, F (2, 472) = 439.8, p < .001 (adjusted means: Block A = 66.9%, Block B = 57.8%, Block C = 69.8%). Response accuracy in Block B (frustration) was significantly lower than the average accuracy in Blocks A and C (reward), F (1, 472) = 865.3, p < .001. CP groups did not differ significantly in overall response accuracy, F (1, 237) = 0.21, p = .65. Likewise, the omnibus CP group x block interaction term was not significant, F (2, 472) = 0.62, p = .54, nor did the reactivity contrast (reward-frustration) differ between CP groups, F (1, 472) = 0.67, p = .41.

When ES was added to the model, CP group and the CP group x block interaction remained non-significant. ES group status did not significantly predict response accuracy, F (1, 235) = 0.59, p = .44, and the overall ES group x block interaction term failed to reach significance, F (2, 468) = 2.00, p = .14. Accuracy reactivity (reward-frustration) did not differ by ES group status, F (1, 468) = 0.00, p = 1.00. Neither the ES x CP interaction, F (1, 235) = 0.00, p = .95, nor the 3-way interaction CP x ES x block, F (2, 468) = 0.47, p = .63, predicted overall accuracy.

Autonomic Arousal

Skin Conductance

Based on relative model fit criteria, a compound symmetric covariance structure was selected for modeling skin conductance activity across the three task blocks. The linear mixed model with CP group, block, and group x block effects, including sex and race as covariates, indicated no omnibus effect of task block on skin conductance activity, F (2, 400) = 0.42, p = .66, nor did SCRs differ significantly in the reactivity contrast (reward-frustration), F (1, 400) = 0.72, p = .40. There was no main effect of CP group on SCRs, F (1, 203) = 0.05, p = .83. The overall CP group x block interaction was not significant, F (2, 400) = 1.60, p = .20, and the reactivity contrast (reward – frustration) similarly did not differ between CP groups, F (1, 400) =1.87, p = .17.

The pattern of findings for the CP group was not altered when ES group was added to the model. However, ES groups did significantly differ in SCRs across the full task, F (1, 201) = 4.09, p = .04. Examination of group means indicates that children with ES symptoms show consistently more SCR activity across all blocks (adjusted mean SCRs per 30-second epoch = 4.0 for the ES group and 3.4 for the non-ES group). The ES group x block interaction was not significant, F (2, 396) = 0.53, p = .59, and the ES groups did not differ on the SCR reactivity contrast, F (1, 396) = 0.69, p = .41. Neither the 2-way interaction, ES x CP, F (1, 201) = 1.10, p = .30, nor the 3-way interaction, ES x CP x block, F (2, 396) = 0.02, p = .98, were significant.

Heart Rate

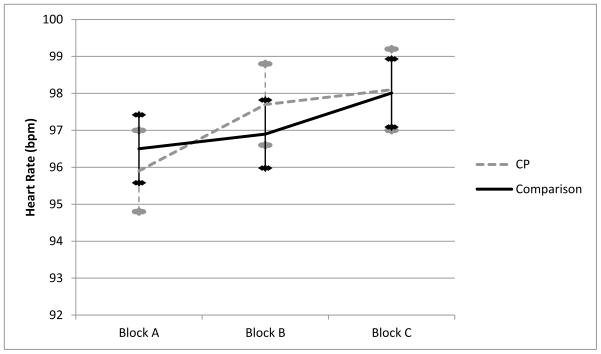

A compound symmetric covariance structure also provided the best fit for the repeated measures of heart rate across the three task blocks. The linear mixed model with CP group, block, and group x block effects indicated a main effect of block, F (2, 413) = 35.4, p < .001 (adjusted mean beats per minute: Block A = 96.2, Block B = 97.3, Block C = 98.1). This effect was not due to changes in heart rate between frustration and reward conditions, F (1, 413) = 0.64, p = .42, but rather a significant increase in heart rate from Block A to Block C, F (1, 413) = 70.0, p < .001. No main effect of CP group was evident, F (1, 218) = 0.01, p = .93, but there was a significant CP x block interaction, F (2, 413) = 4.50, p = .01. As hypothesized, CP groups differed specifically in the reactivity contrast between the frustration and reward conditions, F (1, 413) = 7.23, p = .01. There was no significant difference between CP groups in the degree to which heart rate increased between Blocks A and C, F (1, 413) = 1.72, p = .19. This interaction is illustrated in Figure 2. The CP group exhibits a steeper increase in heart rate from the first reward block to the frustration block. However, post-hoc tests revealed that heart-rate levels did not differ between groups within any given block (p’s > .50).

Figure 2.

Small increases in average heart rate across the three blocks were observed in both groups. A significant quadratic interaction term indicates a more rapid increase in heart rate during the frustration block among the CP group.

Mean values of heart rate across task blocks.

The CP x block interaction remained significant when ES group and its interactions were added to the model, indicating that the CP group difference in frustration reactivity was not driven by comorbid ES symptoms. There was no main effect of ES group on average heart rate across the task, F (1, 216) = 0.30, p = .58, and neither the ES x block interaction, F (2, 409) = 0.34, p = .71, nor the specific ES x reactivity contrast, F (1, 409) = 0.15, p = .70, was significant. Moreover, neither the 2-way interaction (ES x CP), F (1, 216) = 0.43, p = .51, nor the 3-way interaction (ES x CP x block) was significant, F (2, 409) = 0.33, p = .72.

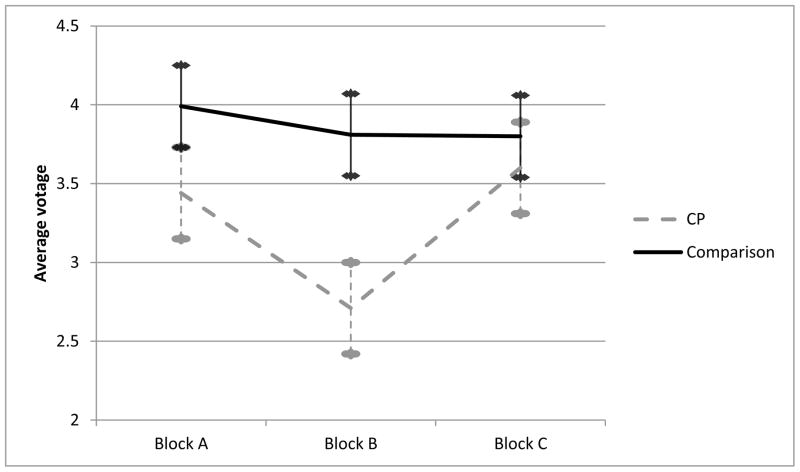

Cognitive Engagement

A compound symmetric covariance structure also provided the best fit for P3b amplitude across the three task blocks. The linear mixed model with CP group, block, and group x block effects revealed a main effect of block, F (2, 464) = 4.61, p = .01 (adjusted mean amplitudes: Block A = 3.7 μV, Block B = 3.3 μV, Block C = 3.7 μV). P3b amplitude was significantly lower in the frustration versus reward conditions, F (1, 464) = 9.21, p = .003, and did not differ between the two reward blocks, F (1, 464) = 0.01, p = .93. There was a marginal main effect of group, F (1, 234) = 3.50, p = .06, with the CP group having lower P3b amplitudes on average (adjusted mean amplitudes: CP group = 3.2 μV, comparison = 3.9 μV). However, this trend-level main effect was qualified by a significant CP x block interaction, F (2, 464) = 3.54, p = .03. As predicted, this was due entirely to the reactivity contrast; a greater decrement in P3b amplitude during the frustration (Block B) versus reward (Blocks A and C) in the CP group than the comparison group, F (1, 464) = 6.09, p = .01. Mean P3b amplitudes in each block for the CP and comparison groups are illustrated in Figure 3. Post-hoc tests of group differences within each block revealed that the groups did not differ in amplitude in either reward block (Block A, F (1, 234) = 1.99, p = .16; Block C, F (1, 234) = 0.28, p = .60), but the CP group evidenced significantly lower P3b amplitude during the frustration block, F (1, 234) = 8.23, p = .005. Therefore, the marginally significant main effect of CP group appears to be driven by the decrement in amplitude specific to the frustration block.

Figure 3.

The CP group evidenced a significantly pronounced decrement in P3b amplitude during the frustration block compared with the comparison group. Groups did not differ in amplitude at blocks A or C.

Mean values of P3b amplitude across task blocks.

Once again, the CP x block interaction remained significant when ES group and its interactions were added to the model, indicating that the CP group difference in P3b amplitude reactivity to frustration was not driven by comorbid ES symptoms. Average P3b amplitude did not differ by ES group, F (1, 232) = 0.27, p = .61. The overall ES x block interaction did not reach significance, F (2, 460) = 2.20, p = .11, and the ES groups did not differ in the reactivity contrast, F (1, 460) = 0.00, p = .98. Neither the 2-way interaction, ES x CP, F (1, 232) = 0.17, p = .68, nor the 3-way interaction, ES x CP x block, F (2, 460) = 0.51, p = .60, was significant.

Physiological Effects of Frustration

A measure of reactivity was computed for each physiological variable and task accuracy by subtracting the value during the frustration block from the average value of the 2 reward blocks. The correlations among the reactivity variables are reported in Table 2. Reactivity in task accuracy was negatively correlated with skin conductance reactivity such that there was a tendency for those with lower levels of accuracy during frustration to have higher levels of skin conductance activity during frustration. The correlation between accuracy reactivity and heart rate reactivity failed to reach significance (p = .07) although the correlation was in the same direction, and heart rate reactivity and skin conductance reactivity were positively correlated with one another (p < .001). Taken together, reactivity to frustration was associated with lower task accuracy among those with greater autonomic arousal, across the entire sample.

Table 2.

Correlations among frustration reactivity measures.

| Accuracy reactivity | P3b reactivity | HR reactivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3b reactivity | .10 | . | |

| HR reactivity | −.13 | .00 | . |

| SCR reactivity | −.14* | −.07 | .25** |

Note.

<.05,

< .01. Age is measured as age at time of physiological assessment. Accuracy is computed as the average percentage of both go- and no-go-trials across all three blocks.

As reported in Table 2, P3b reactivity was not correlated with reactivity in either autonomic system. Therefore group differences in cardiac reactivity cannot be considered to mediate the relationship between conduct problems and disruptions in P3b amplitude during frustration. A regression analysis was conducted to examine whether heart rate reactivity moderated the association between P3b and CP symptoms. CP symptom severity was entered as a dependent variable with centered reactivity measures for heart rate and for P3b amplitude entered as predictors in step 1. The centered interaction term was entered at step 2. The overall model was significant at step 1, F (2, 196) = 5.06, p = .007, R2 = .05. Negative heart rate reactivity (indicating an increase in heart rate during the frustration block) was associated with greater CP symptom severity (β = −.14, p = .05). Positive P3b reactivity scores (indicating a decrease in amplitude during the frustration block) also predicted greater CP symptom severity (β = .18, p = .01). No improvement in the model was observed at step 2, ΔF (1, 193) = .16, p = .69, ΔR2 = .001, indicating no significant interaction between autonomic and cortical indices of reactivity to frustration.

Discussion

Sensitivity to frustration is believed to be at least one mechanism underlying reactive aggressive behavior among individuals with externalizing problems (Blair, 2010). In this study, we examined how children with conduct problems respond physiologically to a laboratory-based frustration condition. We tested two potential processes by which reactivity to frustration could lead to aggressive tendencies: (1) greater autonomic reactivity leading to ‘fight or flight’ levels of sympathetic arousal in response to moderate frustration and (2) affective disruption in cognitive processing that impairs prosocial responding to frustration. Results indicate that children with conduct problems are more sensitive to frustration in that they display a greater relative increase in heart rate during the frustration block, although they do not appear to display a higher magnitude of sympathetic arousal overall. In addition, evidence indicates that children with conduct problems exhibit greater disruptions in ongoing cognitive processes in the context of frustration than comparison children. Our results also indicate that this pattern is associated with externalizing symptoms, and is not attributable to comorbidity between externalizing and internalizing symptoms.

Affective Reactivity

Results from the present study do not indicate that children in the CP group showed higher overall sympathetic arousal. No differences were evident in skin conductance reactivity with regard to the CP groups. However, children characterized by emotional symptoms did show greater skin conductance activity across all blocks. Interestingly, the results do indicate that children in the CP group showed a greater increase in heart rate from the first reward block to the frustration block than the children in the comparison group. Group differences in heart rate were not significant at any individual block, indicating that autonomic arousal was not necessarily exacerbated among children in the CP group, but that the relative change from the reward to frustration block was greater for children in this group. These findings suggest that children with conduct problems may exhibit physiological reactivity in response to lower levels of frustration than those needed to induce reactivity in typically developing children. This interpretation is consistent with a study of boys, ages 9–13, in which those with disruptive behavior disorders evidenced more self-reported anger, more aggressive retaliation, and greater increases in heart rate at lower levels of provocation than typically developing peers (Waschbusch et al., 2002). At high levels of peer provocation, comparison children did not differ from those with disruptive disorders. Thus children with externalizing problems may react more readily with anger in response to frustration.

It is important to note that although cardiac arousal is associated with affective arousal, the nature of this affective state cannot be inferred. Increased cardiac arousal can reflect excitement as well as anger. However, the higher heart rate in the CP group during Block B is not likely to be a result of children in this group entering Block B more excited about their winnings, given a wide range of literature indicating that individuals across a range of antisocial categories show less cardiac reactivity to reward (see Beauchaine, 2012; Matthys, Vanderschuren & Schutter, 2013). It is also noteworthy that children in both groups evidence comparable levels of cardiac arousal in block C, which reflects a peak heart rate for both groups. Heart rate increases appear to be accumulating across the task for both groups, but proceed at different rates. It is possible that this difference reflects different subjective emotions. For instance, the increase in heart rate observed in block C for the comparison children could reflect excited anticipation at the reinstatement of reward and impending prize. Future research attending to self-report of subjective emotions may help illuminate these associations.

Although support for increased sensitivity to frustration among individuals with externalizing behaviors does exist, less research has specifically attended to the affective, as opposed to operant, effects of reward omission. Some studies have found consistent support for reduced sensitivity to reward conditions among externalizing individuals but have not identified evidence of increased sensitivity to reward omission (see Beauchaine, 2012). Thus greater attention to the correlates of sensitivity to frustration is warranted in future research. One possible explanation for discrepant findings is that heightened affective arousal in response to frustration could be more specifically associated with aggressive retaliatory behaviors and not necessarily with non-aggressive externalizing tendencies. Although participants in this sample were grouped by symptoms of conduct problems, selection criteria for recruitment was based on teacher-reported aggression, and so this sample may include a higher representation of aggressive externalizing behavior than other high-risk samples that focused on non-aggressive externalizing traits such as oppositionality and hyperactivity.

Affective Interference in Cognitive Function

Deficiencies in cognitive control are believed to be one component of externalizing behavior problems (Matthys et al., 2013). P3b amplitude is among the most consistently reported biomarker of purported cognitive deficits among children with, or at increased risk for, externalizing problems (Begleiter et al., 1987; Polich et al, 1994; Viana-Wackermann et al., 2007). Our study extends these findings to a younger, predominantly racial minority, and lower SES sample than existing studies. Furthermore, this study is the first to our knowledge to examine the effect of affective context on P3b amplitude among children with externalizing behavior problems. Whereas children in the comparison group evidenced general stability in P3b amplitude across blocks, those in the CP group evidenced a marked decrement in amplitude during the frustration block. Notably, amplitude returned to the pre-frustration levels when reward was reinstated in Block C, suggesting a state-dependent association between P3b and conduct problems.

The specificity of the P3b findings to the frustration block is somewhat inconsistent with the existing literature suggesting a global deficit in P3b amplitude. In our sample, mean P3b in the reward conditions is correlated with executive function and academic achievement, but is not associated with behavior problems (see Willner, Gatzke-Kopp, Bierman, Greenberg, & Segalowitz, in press). It is not clear whether the lack of findings in the reward condition reflects a failure to replicate previous studies, or is a function of the unique affective nature of the present task. The current study lacked an assessment of the P3b in an affectively neutral condition comparable to previous work. As such, it is possible to postulate that deficits would be observed in the CP group in neutral conditions, but that the incentivized context motivates engagement in this group, bringing their attentional allocation in line with their peers. Previous research has demonstrated the ability of reward-incentivized contexts to modulate behavioral performance and neural activation patterns among individuals with impulsivity disorders such as ADHD (Herrera, Speranza, Hampshire, & Bekinschtein, 2014; Liddle et al., 2011).

Given that children with conduct problems evidenced comparable attentional capacity during the reward conditions, it is not entirely clear whether the reduced P3b amplitudes in the frustration condition reflect a disruption in attentional control, or a reallocation of attention to something other than the task-relevant stimulus. This possibility is consistent with a previous study conducted with a sample of male prisoners in which evidence indicated that participants scoring high in externalizing proneness were not over-reactive to motivationally relevant threat cues, but rather showed greater emotion-induced attentional biases (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2012). The authors posited that high-externalizing individuals exhibit a reduction in attentional flexibility that could impede adaptive responding to affective challenges. A recent functional MRI study indicated that children with extreme irritability showed decreased neural activation in regions associated with attention and emotion in response to negative feedback during a frustration condition (Deveney et al., 2013). Like the model proposed by Baskin-Sommers et al., these authors suggest that frustration reduces attentional control resulting in a decrease in flexibility rather than capacity. Our own findings are highly consistent with these models and suggest that negative affect associated with frustrative non-reward functions similarly to negative affect induced by threat cues (e.g. Baskin-Sommers et al., 2012) with regard to attention.

Although the effects of negative affect on attentional biases have been widely reported in association with internalizing disorders (see Baskin-Sommers et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2010), our analyses indicate that the association between reactivity to frustration and conduct problems is not a function of comorbidity with internalizing symptoms. Thus while internalizing disorders are clearly associated with heightened negative affectivity, negative affect associated with frustrative non-reward may be more specific to externalizing symptoms. Attentional bias toward motivationally salient cues is frequently observed in externalizing samples (Avila & Parcet, 2001; Baskin-Sommers et al., 2012; Wallace & Newman, 1997).

Our direct assessment of autonomic activity in addition to P3b amplitude enables us to examine the independent contributions of affective reactivity and cognitive disruption. No interaction between cardiac and P3b measures of reactivity was observed, indicating that the association between P3b amplitude reactivity and conduct problems was not moderated by the degree of cardiac arousal in response to frustration. Furthermore, no direct association between these measures of reactivity was observed and as such, P3b reactivity did not appear to mediate the association between cardiac arousal and conduct problems. It is important to note that groups did not differ in the effects of the frustration condition on performance accuracy. It is possible that this is due to a floor effect in performance for both groups during this block. However, it is also possible that the physiological reactivity observed in the CP group is not accompanied by disruptions in behavioral performance during the task.

Limitations

Although the racial and socioeconomic status of the sample contributes to greater diversity in the literature, these factors may also represent caveats to generalization that should be taken into account. For instance, analyses were conducted with respect to relative levels of P3b amplitude within the sample, but it is possible that the entire sample was drawn from a lower portion of the distribution of the full population. As reflected in the neighborhood demographics, the sample presented here would be considered “high risk” from many developmental perspectives regardless of symptom level. Furthermore, externalizing symptoms were measured only by teacher-reported symptom checklists, and may therefore differ in comparison to samples recruited through psychiatric diagnostic processes.

The sample available for these analyses was relatively large compared with many other ERP studies with children, however missingness was problematic with at least one relevant measure missing for nearly 1/3 of the sample. This led to a scenario in which some participants represented in certain analyses were not represented in others. For instance, the sample size for the ERP analyses was larger than that for the autonomic analyses. The largest contributor to missing data was equipment failures that occurred for a variety of reasons. In order to adhere to inflexible data collection timelines, data collection often had to proceed while new equipment was on order. In addition, some participants were excluded based on their performance on the go/no-go task, which suggested that they were not appropriately engaged in stimulus processing, rendering their P3b amplitudes invalid. Although these excluded participants did not have higher levels of externalizing behaviors, they did show worse performance on cognitive and intellectual measures. As such, it is possible that these individuals were not electively disengaged from the task but rather not capable of the task demands. Thus these findings are not likely to generalize to individuals with cognitive impairment.

Implications

Results from the present study suggest that externalizing problems are characterized by a reduced threshold for responding to frustration (increasing affective arousal at lower levels of frustrative challenge than comparison children) and greater disruption in cognitive attentional processes to task-relevant stimuli. Taken with other literature, externalizing problems may be characterized by greater sensitivity to frustration, but less ability to incorporate frustrative feedback in the conditioning of behavior, possibly due to a redirection of attentional focus toward affective cues. It is further possible that affectively directed attention is associated with decrements in other executive domains such as inhibitory control and mental flexibility, which could further impede resources that could be used to direct frustration in socially adaptive ways (Farmer, Whitehead, & Woolcock, 2007). This may be especially problematic in younger children where the prosocial strategies may be more recently imposed and thus require more effortful selection over habitual response strategies.

Externalizing psychopathology may be represented by a confluence of effects of frustrative non-reward that requires measurement across multiple systems to fully characterize. Initial instantiations of the RDoC matrix have populated the cells with physiological measures thought to most specifically index the primary construct of interest. Frustrative non-reward is biologically defined by the dopaminergic signal of omission of expected reward. Our results support the need to consider affective responses to frustration independent of the midbrain dopamine system, as well as the need to evaluate broader systems, such as the implications of negative affect for attentional systems (listed separately in the RDoC framework). The evaluation of interactions between individual RDoC constructs (such as negative affect via non-reward and attention) introduces a level of complexity to the matrix framework, but may be accommodated by a hierarchical structure in which, for instance, valence systems can be viewed as state-level contexts for other neural systems. In the present study, attentional allocation reflected in the P3b showed state-dependent associations with conduct problems that were not evident under presumably positive (reward) affective contexts.

Highlights.

Conduct problems (CP) are associated with heightened sensitivity to frustration

Children with CP showed faster but not larger changes in heart rate across the task

CP was associated with a marked decrement in P3b amplitude during frustration

Results indicate the need to consider interactions between affect and attention

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health and by The Social Science Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University to the first author, by grant R305B090007 from the Institute of Education Sciences to the second and fourth authors, by grant 5T32 DA017629-07 to the fifth author, and by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to the last author.

The authors also wish to thank Jennifer Ford for her extensive work in managing the complex data collection in this project, the numerous research assistants who contributed to this endeavor, and Jim Stieben for his generosity with the task software. The authors also would like to acknowledge Mark Greenberg, Karen Bierman, and Robert Nix, for their roles in designing, executing, overseeing, and managing the project from which these data are drawn.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. Gatzke-Kopp, Email: lisakopp@psu.edu.

Michelle K. Jetha, Email: michelle_jetha@cbu.ca.

Sidney J. Segalowitz, Email: sid.segalowitz@brocku.ca.

References

- Abler B, Walter H, Erk S. Neural correlates of frustration. NeuroReport. 2005;16:669–672. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200505120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila C, Parcet MA. Personality and inhibitory deficits in the stop-signal task: The mediating role of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:975–986. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers AR, Curtin JJ, Larson CL, Stout D, Kiehl KA, Newman JP. Characterizing the anomalous cognition-emotion interactions in externalizing. Biological Psychology. 2012;91:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Physiological measures of emotion from a developmental perspective: State of the Science: Physiological markers of emotion and behavior dysregulation in externalizing psychopathology. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012;77:79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Rawlings R, Eckardt M. Auditory recovery function and P3 in boys at high risk for alcoholism. Alcohol. 1987;4:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(87)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. Psychopathy, frustration, and reactive aggression: The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex. British Journal of Psychology. 2010;101:383–399. doi: 10.1348/000712609X418480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia MC, Desrocher M, Pepler D, Schroeder JH. Contextualizing the neurobiology of conduct disorder in an emotion dysregulation framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:506–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civai C, Corradi-Dell’Acqua C, Gamer M, Rumiati RI. Are irrational reactions to unfairness truly emotionally-driven? Dissociated behavioral and emotional responses in the Ultimatum Game task. Cognition. 2010;114:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD. Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;493:154–166. doi: 10.1002/cne.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveney CM, Connolly ME, Haring CT, Bones BL, Reynolds RC, Leibenluft E. Neural mechanisms of frustration in chronically irritable children. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:1186–1194. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MJ, MacLaren V, Jarick M, Fugelsang JA, Harrigan KA. The frustrating effects of just missing the jackpot: Slot machine near-misses trigger large skin conductance responses, but no post-reinforcement pauses. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2013;29:661–664. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Kassinove H. Articulated cognitive distortions and cognitive deficiencies in martially violent men. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1998;12:231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Garcia-Andrade C, Phillips E. Visual P3 findings in Mission Indian youth: Relationship to family history of alcohol dependence and behavioral problems. Psychiatry Research. 2001;105:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euser AS, Arends LR, Evans BE, Greaves-Lord K, Huizink AC, Franken IH. The P300 event-related brain potential as a neurobiological endophenotype for substance use disorders: A meta-analytic investigation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36:572–603. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Whitehead KA, Woolcock CM. Temperament, executive functions, and the allocation of attention to punishment feedback in passive avoidance learning. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:569–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Raine A. P3 event-related potential impairments in antisocial and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Raine A, Venables PH, Mednick SA. The association between P3 amplitude at age 11 and criminal offending at age 23. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:120–130. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.719458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzke-Kopp LM, Beauchaine TP, Shannon KE, Chipman J, Fleming AP, Crowell SE, Liang O, Johnson LC, Aylward E. Neurological correlates of reward responding in adolescents with and without externalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:203–213. doi: 10.1037/a0014378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzke-Kopp LM, Greenberg M, Fortunato CK, Coccia MA. Aggression as an equifinal outcome of distinct neurocognitive and neuroaffective processes. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:985–1002. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MGH, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55:468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness AR, Reynolds SM, Lilienfeld SO. A review of systems for psychology and psychiatry: Adaptive systems, personality psychopathology five (PSY-5) and the DSM-5. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2014;96:121–139. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.823438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones C, Schmeichel BJ, Mennitt E, Harmon-Jones E. The expression of determination: Similarities between anger and approach-related positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:172–181. doi: 10.1037/a0020966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera PM, Speranza M, Hampshire A, Bekinschtein TA. Monetary rewards modulate inhibitory control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8:1– 14. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Motl RW, O’Leary KC, Johnson CR, Scudder MR, Castelli DM. From ERPs to academics. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2S:S90– S98. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Smithmyer CM, Ramsden SR, Parker EH, Flanagan KD, Dearing KF, Simons RF. Observational, physiological, and self–report measures of children’s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Development. 2002;73:1101–1118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Malone SM, McGue M. P3 event-related potential amplitude and the risk for disinhibitory disorders in adolescent boys. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:750–757. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM. Developmental endophenotypes: Indexing genetic risk for substance abuse with the P300 brain event-related potential. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;29:169–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Utz A, Oei NYL, Niedtfled I, Bohus M, Spinhoven P, Schmahl C, Elzinga BM. Influence of emotional distraction on working memory performance in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:2181–2192. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Granic I, Lamm C, Zelazo PD, Stieben J, Todd RM, Pepler D. Changes in the neural bases of emotion regulation associated with clinical improvement in children with behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:913–939. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Lamm C, Segalowitz SJ, Stieben J, Zelazo PD. Neurophysiological correlates of emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:430–443. doi: 10.1162/089892906775990633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle EB, Hollis C, Batty MJ, Groom MJ, Totman JJ, Liotti M, Kiddle PF. Task-related default mode network modulation and inhibitory control in ADHD: effects of motivation and methylphenidate. Journal of child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Dexter-Mazza ET. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders: A Step-by-Step Treatment Manual. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 365–420. [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh MA, Morland LA, Frueh BC, Greene CJ, Rosen CS. Peeking into the black box: mechanisms of action for anger management treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28:687–695. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, Vanderschuren LJ, Schutter DJ. The neurobiology of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: Altered functioning in mental domains. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:193–207. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]