Abstract

Platelets have an emerging and incompletely understood role in a myriad of host immune responses, extending their role well beyond regulating thrombosis. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a complex disease process characterized by a range of pathophysiologic processes including oxidative stress, lung deformation, inflammation, and intravascular coagulation. The objective of this review is to summarize existing knowledge on platelets and their putative role in the development and resolution of lung injury.

Keywords: ARDS, platelet, lung injury, ALI, aspirin

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening pulmonary syndrome characterized by the acute development of diffuse lung injury in the setting of a known insult such trauma, sepsis, pneumonia, transfusion, or aspiration. The clinical hallmarks of ARDS are hypoxemic respiratory failure requiring positive pressure ventilation and acute diffuse bilateral lung infiltrates on chest radiography. The diagnostic criteria for ARDS have evolved since the syndrome was first recognized in 1967 (6) and were most recently updated in the 2012 Berlin Definition of ARDS (Table 1) (37).

Table 1.

Berlin definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Berlin Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Within 1 wk of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms | ||

| Chest imaging | Bilateral opacities (on chest radiograph or chest computed tomography) not fully explained by effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or nodules. | ||

| Origin of edema | Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. | ||

| Oxygenation | |||

| Mild | 200 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg with PEEP or CPAP ≥5 cmH2O | ||

| Moderate | 100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤200 mmHg with PEEP ≥5 cmH2O | ||

| Severe | PaO2/FiO2 ≤100 mmHg with PEEP ≥5 cmH2O | ||

| Common risk factors | Pneumonia | Aspiration | Inhalational injury |

| Sepsis | Trauma | Pancreatitis | |

| Pulmonary contusion | Burns (severe) | Shock (noncardiogenic) | |

| Near drowning | Drug overdose | Multiple transfusions | |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

The public health impact of ARDS is considerable, and it is estimated that 200,000 cases of ARDS occur annually in the United States (87). Estimates of mortality associated with ARDS range from 26 to 51% (9, 16, 35, 36, 87, 97). With the exception of preventing further iatrogenic lung injury through lung-protective mechanical ventilation (1, 38), neuromuscular blockade (81), prone positioning (40), and conservative fluid management (76), no effective ARDS therapeutic strategies presently exist. Recent studies have indicated that both the incidence of ARDS, particularly hospital-acquired ARDS, and ARDS-associated mortality are decreasing over the last decade (33, 58). Nonetheless, the impact of ARDS on patient morbidity and mortality remains substantial, and there is a pressing need to develop ARDS prevention strategies with a view to ultimately improving patient-important outcomes.

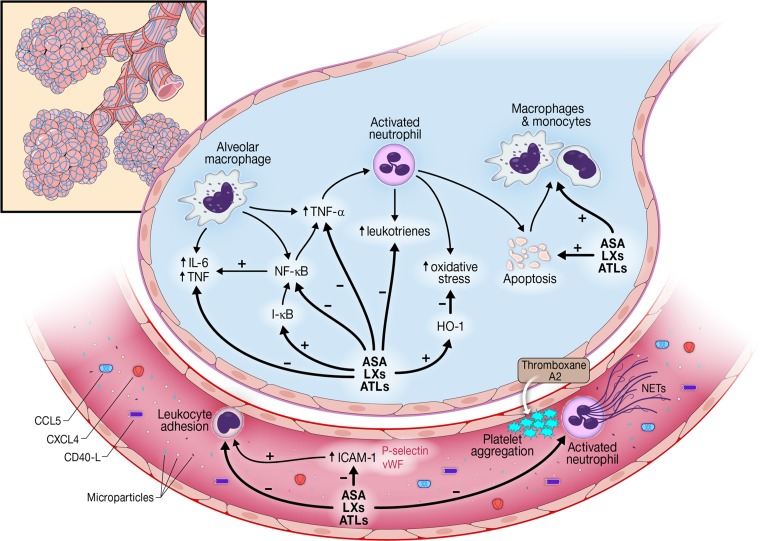

The clinical syndrome of ARDS is characterized by injury to the alveolar-capillary barrier resulting in alveolar flooding and hypoxemia (99). Although preliminary work supports roles for oxidative stress (23, 48), endothelial activation and injury (70, 80, 98), lung epithelial injury (17, 31), inflammation (82), intravascular coagulation (100), and platelet activation (43, 107), the precise mechanisms underlying ARDS remain incompletely understood, particularly in the clinical setting. Emerging evidence has suggested a plausible role for platelets in both the pathogenesis and resolution of lung injury. The purpose of this review is to summarize current understanding of the role of platelets in lung injury development and resolution, as well as to examine plausible platelet-associated ARDS preventative strategies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms by which platelets may contribute to the development and resolution of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NF-кB, nuclear factor-к-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; ASA, aspirin; LXs, lipoxins; ATLs, aspirin-triggered lipoxins; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule; CCL-5, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-5; CXCL4, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-4; vWF, von-Willebrand factor; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps.

Platelet Function, Structure, and Biology

Platelets are anucleate multipurpose circulating cells derived from megakaryocyte precursors. Although the majority of megakaryopoiesis occurs in the bone marrow, there is considerable evidence for megakaryopoiesis occurring in other organs, including the lungs (29, 102). Traditionally viewed as mediators of hemostasis and coagulation, emerging data suggest an additional and significant role for platelets in immune modulation including both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory host responses, as well as antimicrobial host defense (46, 51, 105).

Platelets in homeostasis.

The most clearly established role for platelets is in homeostasis (49). Circulating platelets are quiescent until there is a break in the vascular endothelium that exposes the underlying extracellular matrix. Exposure to collagen, tissue factor, thrombin, or other extracellular matrix constituents triggers platelet activation leading to a sequence of events designed to promote hemostasis (49). Firstly, platelets release mediators such as thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) that go on to promote both chemotaxis to the site of injury and activation of additional platelets. Secondly, activated platelets induce integrins such as the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) receptor to bind to fibrin and fibrinogen. Since fibrinogen binds multiple GP IIb/IIIa receptors, and each platelet has thousands of GP IIb/IIIa receptors, this process results in rapid platelet aggregation and clot stabilization. Thirdly, platelet aggregation is further enhanced by conformational changes in platelet shape. The cross-linked fibrin clot further stabilizes this platelet-fibrin aggregate, promoting mechanical clot stabilization at the site of injury (26, 49).

Platelets and immune response.

In addition to their primary role of facilitating homeostasis, platelets are increasingly recognized as playing an important supportive role in the host immune response. Platelet activation causes the release of a number of immunomodulatory mediators that are both pro- and anti-inflammatory in nature. These can be broadly divided into cell membrane proteins and mediators released from the activated platelet into surrounding tissues or the blood stream.

Several platelet-expressed cell surface proteins are implicated in the immunomodulatory process. The selectin family is one such family of proteins, with several putative roles proposed. P-selectin is a cell surface protein that, when activated, creates a phospholipid framework that facilitates the recruitment of neutrophils to the site of injury (51, 104). In animal studies, P-selectin knockout mice have substantially reduced neutrophil recruitment with attenuated neutrophil-mediated inflammation (94). Platelet-derived P-selectin is also a key facilitator in the phenomenon of “neutrophil rolling.” This is a process whereby P-selectin-mediated adhesion of neutrophils to endothelium-bound platelets slows neutrophil flow in capillaries and ultimately facilitates migration across the endothelium (41). This process is also known as “secondary capture” where platelets first interact with neutrophils before promoting neutrophil-endothelium interactions (57). In addition to neutrophils, the phospholipid framework created by P-selectin has been shown to facilitate the recruitment of monocytes and lymphocytes. This property has been implicated in the development of atherosclerotic plaques in atherosclerosis, as well as in acute myocardial infarction (77).

Another series of platelet cell surface proteins strongly implicated in the immune response are the surface proteins CD40 and CD154 (previously known as CD40L) (45). These receptors are crucial in the interaction between lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells. The most common pathway for this to occur is for CD40 on antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells or macrophages to interact with lymphocytes expressing CD154. However, platelet-expressed CD154 also interacts with CD40 on endothelial cells. This causes numerous downstream effects, upregulating a number of proinflammatory mediators such as intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), and the chemokine chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL2) (5, 42). These mediators in turn recruit neutrophils to sites of tissue injury. CD154 in its soluble form is released by platelets and facilitates the release of interleukin-6 and tissue factor, as well as the upregulation of E-selectin and P-selectin on both endothelial cells and other platelets (50). Platelet-expressed CD154 also promotes B-cell differentiation and class switching (32). Infusion of wild-type platelets into CD154-deficient mice promotes virus-specific IgG levels and protects from viral infection (95). Understanding of these processes remains the focus of active research.

Platelets also express several Toll-like receptors (TLRs) at low levels in their resting state. These TLRs recognize structurally conserved molecular patterns on pathogens (28). Following platelet activation, TLRs are upregulated and present on the cell surface in increasing concentrations (7). TLR activation within platelets is linked to the release of numerous proinflammatory mediators such as chemokines, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (7, 10). Since platelets are often present early at sites of tissue injury, platelets may have an important role in the innate immune response and additionally can augment the systemic inflammatory response after contact with pathogens.

In addition to cell surface proteins, platelets secrete several mediators that have nonhomeostatic functions. These are typically stored in intracellular pockets known as “granules.” These granules are nonspecific and contain a large and varied array of mediators. For example, on activation, α-granules contain and release chemokines [such as CXC chemokine ligand 4 (CXCL4), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-5 (CCL5), and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-3 (CCL3)], promitogenic factors, adhesive proteins, and coagulation factors [such as von-Willebrand factor (vWF) and fibrinogen]. While many of these mediators play an active role in the clotting cascade, many also have varying effects on the immune response (84).

Notably, the role of the multiple chemokines released during platelet activation is relatively well established. In areas of tissue injury, they create a local concentration gradient that facilitates leukocyte migration and recruitment. Several chemokines have been described, such as the kinocidin family of microbicidal chemokines such as CXCL4 and CCL5. Platelets additionally recognize a wide range of chemokines, including those secreted by other platelets. This positive feedback loop consequently amplifies both the homeostatic and immune response at the site of tissue injury (27).

The α-granules within platelets additionally contain defensins, antibacterial proteins that are the thrombocidin family and are also released at the site of tissue injury. These cationic proteins have an intrinsic bactericidal effect against a range of pathogens, such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus Aureus, and Bacillus subtilis and therefore form an important part of the host innate immune response (55). In keeping with a direct role for platelets in the immune response, several studies have shown platelets are independently capable of killing pathogens in specific settings. For example, purified platelets can kill Plasmodium falciparum species in culture, and both platelet-deficient and aspirin-treated mice were more susceptible to death during erythrocytic infection with Plasmodium chabaudi (68).

While the majority of platelet-mediated immune effects are proinflammatory, platelets additionally contain large quantities of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), a largely immunosuppressive mediator. Patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) have low circulating TGF-β and reduced concentrations of regulatory T-cells (3, 4). Treatment of ITP increases levels of TGF-β and CD4-positive T-regulatory cells (60, 61). The expression of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators suggests a potentially more complex role for platelets in immune modulation, where they are capable of both upregulating and downregulating aspects of the innate and adaptive immune response. Mediators other than those discussed here have been also identified in platelets, but their precise roles also remain areas of ongoing research (88).

Platelets and Lung Injury

Both dysregulated coagulation and an excessive inflammatory response are key pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of ARDS (103). The hypothesis linking platelets to lung injury in ARDS is largely predicated on the key roles for platelets in these two pathways. Indeed, there is substantial evidence linking platelets to the development of lung injury.

In a mouse model investigating platelet-neutrophil interactions in acid-induced lung injury, there was an increase in platelet-derived thromboxane-A2 and P-selectin, and these in turn led to increased neutrophil activation (108). Activated platelets additionally induced expression of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells, promoting neutrophil adhesion and migration. Inhibition of platelet-neutrophil aggregation resulted in reduced neutrophil recruitment, increased animal survival time, and less hypoxia. Taken together, these results were suggestive of an important adjunctive role for platelets in the immune response in ARDS (108). In a study of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) fluid from patients with ARDS, platelet-derived CCL5-CXCL4 heteromers were correlated with BAL leukocyte counts. In a murine model, the same investigators found that platelet depletion in a murine model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung injury markedly reduced the degree of lung neutrophil infiltration, suggesting an important role for platelets in lung injury. The investigators then used antibodies targeted against CCL5 and CXCL4, which markedly reduced vascular permeability and neutrophil lung recruitment. The use of a peptide antagonist to specifically disrupt the CCL5-CXCL4 heteromers also markedly reduced lung edema, neutrophil infiltration, and tissue damage in the LPS-, acid-, and sepsis-induced lung injury models. Taken together, this suggests an important and causal role for platelet-derived chemokines in the development of lung injury (39). In a rat model of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI), high tidal volume ventilation was associated with increased levels of vWF, platelet glycoprotein 1b, and platelet P-selectin on endothelial cells (106). Selective removal of platelets and administration of monoclonal antibodies directed against P-selectin reduced endothelial cell vWF expression. Homozygous, but not heterozygous, P-selectin knockout mice also had reduced endothelial cell vWF expression (106). These data suggest that during lung-injurious mechanical ventilation platelets deliver leukocyte-binding proteins to endothelial cell surfaces promoting leukocyte recruitment and playing a key role in forming the proinflammatory milieu.

Human studies have also shown a link between platelets and lung injury. In a study of BAL in patients with ARDS compared with healthy controls, there were increased levels of platelet-derived α-granules and other platelet-derived proteins. Increased concentrations of these platelet-derived proteins were also associated with greater severity of ARDS (47). In a small case series of patients with lung injury, patients with ARDS had greater evidence of platelet activation than healthy controls. Interestingly, while platelet activation was greater, homeostasis was impaired, suggesting that platelets could be potentially “diverted” from their regular role in homeostasis to a more immunomodulatory role (18).

Several studies have highlighted possible genetic predispositions to ARDS. For example, genetic variants in genes involved in inflammation (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) (71), coagulation (plasminogen activator inhibitor-1) (64), sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-3 (46), and endothelial integrity (angiopoetin-2) (72) have all been implicated in ARDS risk. Recently, a single-center study identified the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7766874 within the LRRC16A gene that determined both platelet count and ARDS risk [odds ratio (OR): 0.68; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.51–0.90] in a cohort of patients at risk of developing ARDS (101). LRRC16A encodes capping protein ARP2/3 and myosin-linker (CARMIL), a scaffold protein involved in actin-based cellular processes. The SNP rs7766874 is hypothesized to cause abnormal megakaryocyte maturation, altered platelet formation, and thus lower platelet counts. However, it is unclear precisely how the reduced platelet counts in patents with the LRRC16A SNP affect ARDS risk: whether it is a reflection of reduced platelet production, increased platelet activation/consumption, or platelet sequestration in lung tissues.

Another mechanism by which platelets are hypothesized to modulate the immune response is their role in the generation of microparticles (MP) (109). MPs are small (50 nm to 1 μm) circulating cell-derived vesicles that break off from intact cells and may contain a wide variety of enzymes and proteins, as well as mRNA (54, 69). MPs are then phagocytosed by other cells, thus facilitating intercellular communication. This intracellular communication occurs either through the exchange of genetic material or through transfer of soluble cell signaling molecules (72, 101). MPs can originate from any cell. However, the majority of MPs in humans originate from platelets and megakaryocytes (59). In vivo studies suggest that platelet-derived microparticles (PMPs) have a half-life of ∼10 min and have distinct intracellular and cell surface characteristics separating them from MPs of other cellular origins (2). For example, PMPs have surface receptors for CD31, CD40L, CD41a, CD42a, CD42b, CD61, CD62P, CD63, CD107a, fibrinogen, and vWF, a cell surface profile that is distinct MPs from other inflammatory cells (54). Proposed triggers for PMP formation include mechanical injury, shear injury to platelets, and inflammation. However, studies in humans are relatively limited, with the majority of data in vitro or in animal models.

Several putative roles for MPs in ARDS have been proposed. Firstly, MPs can promote the inflammatory response in lung injury through interactions with neutrophils and endothelial cells. In cultured human cells, PMPs can interact with neutrophils through activation of cell surface proteins (including mediators such as P-selectin) (8, 93). Similarly, PMPs can promote cytokine and inflammatory mediator production in endothelial cells (30). In response to LPS, MPs from LPS-stimulated platelets induce VCAM-1 production in cultured human endothelial cells (56). While the nature of the immune modulatory potential of PMPs remains incompletely characterized, in vitro studies have certainly indicated the potential for PMPs as a contributor to the pathogenesis of ARDS. However, data are limited and it is important to note little evidence has directly linked PMPs to lung injury in humans.

Another mechanism by which platelets interact with the immune system is through activation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs are a mechanism by which neutrophils facilitate antibacterial effects beyond phagocytosis. Activation of neutrophils release web-like structures of DNA and decondensed chromatin that have intrinsic proteolytic activity targeted against microbes (15). NETs exist primarily in the bloodstream, targeting circulating pathogens (14), but can also exist in tissues themselves (11, 12). While important as part of the innate immune response, NET formation requires neutrophil cell death, and the inflammatory response that this cell death causes may lead to excess inflammation in certain clinical settings such as ARDS and severe sepsis. For example, in a mouse model of influenza-induced ARDS, large amounts of NETs were found in areas of lung injury. Inhibition of neutrophil activity through anti-myeloperoxidase and anti-superoxide dismutase antibodies reduced NET formation and reduced lung injury. However, no treatments specifically block NET formation, and consequently, it is difficult to disentangle the role of NETs from the wider role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of these syndromes (75).

Platelets are one of the mechanisms by which NETs can be activated, and this has been investigated in several clinical contexts (65). In a study of patients with severe sepsis and bacterial blood stream infection, platelet-bound TLR4 detected TLR4 ligands in blood, activating neutrophils and facilitating the formation of NETs in the bloodstream, primarily in liver sinusoids and pulmonary capillaries (25). Interestingly, LPS in high concentrations in the absence of platelets is not able to generate NET formation, suggesting that platelets are not just facilitators in this process but in fact an essential mediator. This study also noted substantial tissue injury at the site of NET formation as a byproduct of bacterial entrapment. Data also implicate NET formation in lung injury. In a mouse model of transfusion-associated lung injury, platelet inhibition through either aspirin or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor reduced the degree of lung injury and reduced the formation of NETs (19). Consequently, platelet inhibition could plausibly reduce tissue injury in ARDS through reduced production of NETs.

Platelets and the resolution of lung injury.

While the initial inflammatory response is important in host defense, dysregulated or unrestrained inflammation can be deleterious and an important contributor to clinical syndromes such as ARDS (56). Mediators that promote the resolution of lung injury are being increasingly identified. Given the paucity of effective preventative or therapeutic strategies for ARDS, promoting either the concentration or activity of specific resolution-phase molecules could be a potentially fruitful avenue of research.

Several physiologic processes occur during the resolution of acute inflammation in the lung (56, 83, 86). Neutrophils and other acute phase inflammatory cells undergo apoptosis and are cleared by macrophages in a noninflammatory manner. As the numbers of neutrophils reduce, further neutrophil recruitment and migration declines. Cells that promote organized tissue healing, particularly macrophages and lymphocytes, increase. Endothelial and epithelial cells also start to regenerate, with the eventual goal of reforming barrier integrity at the alveolar/capillary junction. Capillaries and tissue lymphatics resorb excess lung water. The processes underlying lung resolution have been more extensively reviewed elsewhere (56).

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition that many of these resolution pathways are mediated by a novel family of lipid mediators known as specialized proresolving mediators (SPMs) (56). SPMs derive from essential omega-3 fatty acids, in particular eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). SPMs are divided into several families of molecules: the resolvins, protectins, lipoxins, and maresins. While the function of SPMs remains incompletely characterized, these mediators are thought to primarily promote the cessation of acute inflammatory and stimulate proresolution processes.

Platelets are believed to play an important role in the production and regulation of several of these proresolving mediators. An example of such interactions is highlighted with the lipoxin family of SPMs. Lipoxins are immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory bioactive mediators derived enzymatically from arachidonic acid. Lipoxins are found in low levels during acute inflammation and increase in concentration during the resolution of inflammation (44). Lipoxins are produced by platelet 12-lipoxygenase from LTA4, a precursor protein derived in neutrophils. Two lipoxins have been described, LXA4 and LXB4 (91). Lipoxins activate transmembrane receptors such as LTA4R and go on to inhibit a range of proinflammatory processes such as chemotaxis, reactive oxygen species generation, and neutrophil proliferation (21). During the resolution of inflammation, lipoxins promote macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic inflammatory cells (73).

Interestingly, aspirin can trigger lipoxins. Aspirin irreversibly acetylates cyclooxygenase, blocking prostaglandin production among other actions. However, one additional action of acetylated COX-2 is to convert arachidonic acid into a precursor for neutrophils to produce 15(R)-epi-LXA4 and 15(R)-epi-LXB4. These are ultimately transformed by platelets into metabolically active lipoxins (24). These lipoxins are different structurally from endogenously produced lipoxins, and aspirin is the only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory capable of triggering lipoxin formation. In humans, aspirin ingestion has been shown to increase aspirin-triggered lipoxin concentrations (22, 74). In addition to lipoxins, aspirin has also been shown to increase concentrations of resolvins (79) through acetylation of endothelial cell cyclooxygenase-2. The unique ability of aspirin to promote proresolution mediatiors is part of the reason for the active interest in aspirin as a possible preventative therapy for ARDS. Resolvins, and other SPMs, are more fully reviewed elsewhere (90, 92).

Beyond using aspirin to promote the development of aspirin-triggered lipoxins, synthetic lipoxins have also been developed. Again, the primary goal of these synthetic mediators is to potentially promote the cessation of acute inflammation and resolution of inflammation in clinical settings such as ARDS or septic shock, where the inflammatory response may be excessive or dysregulated (67). However, at present, little data exist about the role of exogenous synthetic lipoxins in human studies or animal studies of ARDS.

Antiplatelet Therapies in the Prevention of Lung Injury

Several studies have linked antiplatelet therapies with anti-inflammatory properties, particularly in atherosclerosis. For example, in a study of primary prevention of cardiac disease in patients with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), aspirin therapy was associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction and reduced hs-CRP (85). However, other studies of aspirin in patients with elevated hs-CRP have shown no clear anti-inflammatory properties of aspirin, and equipoise remains (96).

Given the evidence supporting the role of platelets in lung injury, several studies have specifically investigated plausible roles for anti-platelet agents in the prevention or treatment of ARDS. As discussed earlier, in a mouse model of acid-induced lung injury, platelet depletion resulted in reduced neutrophil recruitment, increased animal survival time, and less hypoxia (108). In a mouse model of transfusion-associated acute lung injury (TRALI), both platelet depletion and aspirin administration reduced plasma thromboxane B2 production, lowered extravascular lung water values, and improved survival (62).

Human studies have also suggested a possible role for antiplatelet therapies in ARDS (Table 2). In a retrospective single-center study of prehospitalization antiplatelet therapy in a cohort of patients with at least one risk factor for developing ARDS, patients receiving an antiplatelet agent (most commonly aspirin) had a substantially reduced incidence of ARDS (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.84) (34). These findings were replicated in a secondary analysis of a large single-center prospective study that evaluated 1,149 patients with ARDS. Those with prehospital aspirin use were again found to have a reduced incidence of ARDS (OR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.46–0.94) (20). The findings from these studies were tested in a larger, more heterogeneous, multicenter cohort evaluating prehospital aspirin and risk of ARDS. In this larger study, prehospital aspirin did not significantly mitigate ARDS risk, but a trend to reduced incidence was seen (OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.48–1.03; P = 0.07) (52). In addition to ARDS prevention, studies have also evaluated outcomes in patients with ARDS receiving antiplatelet therapies. In a prospective observational study of 202 adult patients with ARDS, prehospital aspirin therapy was associated with a substantial reduction in overall intensive care unit mortality (OR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.15–0.96) (13).

Table 2.

Human studies evaluating the roles of platelets in lung injury/ARDS

| Authors | Study Year | Study Type | n | Study Setting | Study Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erlich JM et al. (34) | 2011 | Retrospective cohort study | 161 | Single center, medical ICU | Prehospital antiplatelet therapy was associated with a reduced incidence of ARDS (12.7 vs. 28.0%). |

| Kor DJ et al. (52) | 2011 | Prospective cohort study | 3855 | Multicenter (22 hospitals), all ICUs | Prehospital antiplatelet therapy was not associated with the development of ARDS. |

| O'Neal HR Jr et al. (78) | 2011 | Prospective cross sectional | 575 | Single center, all ICUs | Prehospital aspirin use was not associated with the development of ARDS. |

| Chen W et al. (20) | 2015 | Prospective cohort study (secondary analysis) | 1149 | Single center, all ICUs | Prehospital aspirin use was associated with a reduced incidence of ARDS (OR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.46–0.94). |

| Mazzeffi M et al. (66) | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 22 | Single-center, postaortic valve surgery | Preoperative aspirin use was not associated with a decreased incidence of ARDS or improved oxygenation after aortic valve replacement surgery. |

| Boyle AJ et al. (13) | 2015 | Prospective cohort study | 202 | Single center, medical/surgical ICU | Prehospital aspirin therapy was associated with reduced mortality in patients with ARDS (OR: 0.38, 95%, CI: 0.15 to 0.96). |

| Wei et al. (101) | 2015 | Observational cohort study | 1655 | Single center, medical/surgical ICU | In patients with ARDS, an intronic single nucleotide polymorphism in the locus LRRC16A that was associated with lower platelet counts and an increased risk of developing ARDS. |

| LIPS-A investigators (54) | Ongoing | Phase III double-blind randomized control trial | 400 | Multicenter (14 hospitals), all ICUs | Patients at risk of developing ARDS randomized to receive aspirin (325 mg once followed by 81 mg daily for 7 days) or placebo. Primary outcome will be development of ARDS. |

ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

While these studies do suggest possible protective effects of aspirin in ARDS, other studies have shown no significant association between prehospital aspirin use and the development of ARDS (78) nor any beneficial effect of aspirin in reducing the incidence of ARDS after elective surgery (66). Given the ongoing uncertainty about the potential utility of antiplatelet therapies in ARDS, a multicenter randomized control trial of aspirin for the prevention of ALI (LIPS-A) is currently underway (ClincalTrials.gov ID: NCT01504867) (54).

Conclusion

While platelets are primarily considered mediators of homeostasis, our review has outlined emerging evidence linking platelets to roles beyond thrombosis, particularly in the context of immune modulation and ARDS. However, our understanding of these additional platelet functions, and how best to modulate them in patients with or at risk for ARDS, remains incompletely characterized. Given the paucity of therapeutic and preventative options in ARDS, further delineating the role of platelets in ARDS and particularly the efficacy of antiplatelet therapy is of profound importance and a crucial avenue for ongoing research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: H.Y. and D.J.K. conception and design of research; H.Y. and D.J.K. analyzed data; H.Y. and D.J.K. prepared figures; H.Y. and D.J.K. drafted manuscript; H.Y. and D.J.K. edited and revised manuscript; H.Y. and D.J.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury, and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network N Engl J Med 342: 1301–1308, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal NR, King LS, D'Alessio FR. Diverse macrophage populations mediate acute lung inflammation and resolution. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L709–L725, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson PO, Olsson A, Wadenvik H. Reduced transforming growth factor-beta1 production by mononuclear cells from patients with active chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 116: 862–867, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson PO, Stockelberg D, Jacobsson S, Wadenvik H. A transforming growth factor-beta1-mediated bystander immune suppression could be associated with remission of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Hematol 79: 507–513, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andre P, Nannizzi-Alaimo L, Prasad SK, Phillips DR. Platelet-derived CD40L: the switch-hitting player of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 106: 896–899, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet 2: 319–323, 1967.4143721 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslam R, Speck ER, Kim M, Crow AR, Bang KW, Nestel FP, Ni H, Lazarus AH, Freedman J, Semple JW. Platelet Toll-like receptor expression modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced thrombocytopenia and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in vivo. Blood 107: 637–641, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastarache JA, Fremont RD, Kropski JA, Bossert FR, Ware LB. Procoagulant alveolar microparticles in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1035–L1041, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bersten AD, Edibam C, Hunt T, Moran J; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Incidence and mortality of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome in three Australian States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 443–448, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair P, Rex S, Vitseva O, Beaulieu L, Tanriverdi K, Chakrabarti S, Hayashi C, Genco CA, Iafrati M, Freedman JE. Stimulation of Toll-like receptor 2 in human platelets induces a thromboinflammatory response through activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Circ Res 104: 346–354, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosmann M, Grailer JJ, Ruemmler R, Russkamp NF, Zetoune FS, Sarma JV, Standiford TJ, Ward PA. Extracellular histones are essential effectors of C5aR- and C5L2-mediated tissue damage and inflammation in acute lung injury. FASEB J 27: 5010–5021, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosmann M, Ward PA. Protein-based therapies for acute lung injury: targeting neutrophil extracellular traps. Expert Opin Ther Targets 18: 703–714, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle AJ, Di Gangi S, Hamid UI, Mottram LJ, McNamee L, White G, Cross LJ, McNamee JJ, O'Kane CM, McAuley DF. Aspirin therapy in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is associated with reduced intensive care unit mortality: a prospective analysis. Crit Care 19: 109, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303: 1532–1535, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Beneficial suicide: why neutrophils die to make NETs. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 577–582, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT; National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 351: 327–336, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calfee CS, Ware LB, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Wickersham N, Matthay MA. Plasma receptor for advanced glycation end products and clinical outcomes in acute lung injury. Thorax 63: 1083–1089, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carvalho AC, Quinn DA, DeMarinis SM, Beitz JG, Zapol WM. Platelet function in acute respiratory failure. Am J Hematol 25: 377–388, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, Nguyen JX, Marques MB, Monestier M, Toy P, Werb Z, Looney MR. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 122: 2661–2671, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W, Janz DR, Bastarache JA, May AK, O'Neal HR Jr, Bernard GR, Ware LB. Prehospital aspirin use is associated with reduced risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill patients: a propensity-adjusted analysis. Crit Care Med 43: 801–807, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory circuitry: lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor ALX. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 73: 163–177, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang N, Bermudez EA, Ridker PM, Hurwitz S, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers antiinflammatory 15-epi-lipoxin A4 and inhibits thromboxane in a randomized human trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15178–15183, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow CW, Herrera Abreu MT, Suzuki T, Downey GP. Oxidative stress and acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29: 427–431, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claria J, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers previously undescribed bioactive eicosanoids by human endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 9475–9479, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, Keys EM, Allen-Vercoe E, Devinney R, Doig CJ, Green FH, Kubes P. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med 13: 463–469, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clemetson KJ, Clemetson JM. Platelet collagen receptors. Thromb Haemost 86: 189–197, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clemetson KJ, Clemetson JM, Proudfoot AE, Power CA, Baggiolini M, Wells TN. Functional expression of CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CXCR4 chemokine receptors on human platelets. Blood 96: 4046–4054, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cognasse F, Hamzeh H, Chavarin P, Acquart S, Genin C, Garraud O. Evidence of Toll-like receptor molecules on human platelets. Immunol Cell Biol 83: 196–198, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deutsch VR, Tomer A. Megakaryocyte development and platelet production. Br J Haematol 134: 453–466, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eickmeier O, Seki H, Haworth O, Hilberath JN, Gao F, Uddin M, Croze RH, Carlo T, Pfeffer MA, Levy BD. Aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 reduces mucosal inflammation and promotes resolution in a murine model of acute lung injury. Mucosal Immunol 6: 256–266, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisner MD, Parsons P, Matthay MA, Ware L, Greene K. Plasma surfactant protein levels and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Thorax 58: 983–988, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elzey BD, Tian J, Jensen RJ, Swanson AK, Lees JR, Lentz SR, Stein CS, Nieswandt B, Wang Y, Davidson BL, Ratliff TL. Platelet-mediated modulation of adaptive immunity. A communication link between innate and adaptive immune compartments. Immunity 19: 9–19, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erickson SE, Martin GS, Davis JL, Matthay MA, Eisner MD, Network NN. Recent trends in acute lung injury mortality: 1996–2005. Crit Care Med 37: 1574–1579, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erlich JM, Talmor DS, Cartin-Ceba R, Gajic O, Kor DJ. Prehospitalization antiplatelet therapy is associated with a reduced incidence of acute lung injury: a population-based cohort study. Chest 139: 289–295, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Muriel A, Ferguson ND, Penuelas O, Abraira V, Raymondos K, Rios F, Nin N, Apezteguia C, Violi DA, Thille AW, Brochard L, Gonzalez M, Villagomez AJ, Hurtado J, Davies AR, Du B, Maggiore SM, Pelosi P, Soto L, Tomicic V, D'Empaire G, Matamis D, Abroug F, Moreno RP, Soares MA, Arabi Y, Sandi F, Jibaja M, Amin P, Koh Y, Kuiper MA, Bulow HH, Zeggwagh AA, Anzueto A. Evolution of mortality over time in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 220–230, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estenssoro E, Dubin A, Laffaire E, Canales H, Saenz G, Moseinco M, Pozo M, Gomez A, Baredes N, Jannello G, Osatnik J. Incidence, clinical course, and outcome in 217 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 30: 2450–2456, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L, Brower R, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, Rhodes A, Slutsky AS, Vincent JL, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ranieri VM. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med 38: 1573–1582, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Futier E, Pereira B. Intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation. N Engl J Med 369: 1862–1863, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grommes J, Alard JE, Drechsler M, Wantha S, Morgelin M, Kuebler WM, Jacobs M, von Hundelshausen P, Markart P, Wygrecka M, Preissner KT, Hackeng TM, Koenen RR, Weber C, Soehnlein O. Disruption of platelet-derived chemokine heteromers prevents neutrophil extravasation in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 628–636, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, Mercier E, Badet M, Mercat A, Baudin O, Clavel M, Chatellier D, Jaber S, Rosselli S, Mancebo J, Sirodot M, Hilbert G, Bengler C, Richecoeur J, Gainnier M, Bayle F, Bourdin G, Leray V, Girard R, Baboi L, Ayzac L; PROSEVA Study Group. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 368: 2159–2168, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammer DA, Apte SM. Simulation of cell rolling and adhesion on surfaces in shear flow: general results and analysis of selectin-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Biophys J 63: 35–57, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammwohner M, Ittenson A, Dierkes J, Bukowska A, Klein HU, Lendeckel U, Goette A. Platelet expression of CD40/CD40 ligand and its relation to inflammatory markers and adhesion molecules in patients with atrial fibrillation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 232: 581–589, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashimoto N, Kawabe T, Imaizumi K, Hara T, Okamoto M, Kojima K, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y. CD40 plays a crucial role in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30: 808–815, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haworth O, Cernadas M, Yang R, Serhan CN, Levy BD. Resolvin E1 regulates interleukin 23, interferon-gamma and lipoxin A4 to promote the resolution of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol 9: 873–879, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henn V, Slupsky JR, Grafe M, Anagnostopoulos I, Forster R, Muller-Berghaus G, Kroczek RA. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature 391: 591–594, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herold S, Gabrielli NM, Vadasz I. Novel concepts of acute lung injury and alveolar-capillary barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L665–L681, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Idell S, Maunder R, Fein AM, Switalska HI, Tuszynski GP, McLarty J, Niewiarowski S. Platelet-specific alpha-granule proteins and thrombospondin in bronchoalveolar lavage in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Chest 96: 1125–1132, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, Veldhuizen R, Leung YH, Wang H, Liu H, Sun Y, Pasparakis M, Kopf M, Mech C, Bavari S, Peiris JS, Slutsky AS, Akira S, Hultqvist M, Holmdahl R, Nicholls J, Jiang C, Binder CJ, Penninger JM. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 133: 235–249, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson SP. The growing complexity of platelet aggregation. Blood 109: 5087–5095, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapur R, Zufferey A, Boilard E, Semple JW. Nouvelle cuisine: platelets served with inflammation. J Immunol 194: 5579–5587, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katz JN, Kolappa KP, Becker RC. Beyond thrombosis: the versatile platelet in critical illness. Chest 139: 658–668, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kor DJ, Erlich J, Gong MN, Malinchoc M, Carter RE, Gajic O, Talmor DS; U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators. Association of prehospitalization aspirin therapy and acute lung injury: results of a multicenter international observational study of at-risk patients. Crit Care Med 39: 2393–2400, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kor DJ, Talmor DS, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Carter RE, Hinds R, Park PK, Gajic O, Gong MN; US Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention with Aspirin Study Group (USCIITG: LIPS-A). Lung Injury Prevention with Aspirin (LIPS-A): a protocol for a multicentre randomised clinical trial in medical patients at high risk of acute lung injury. BMJ Open 2: 5, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krijgsveld J, Zaat SA, Meeldijk J, van Veelen PA, Fang G, Poolman B, Brandt E, Ehlert JE, Kuijpers AJ, Engbers GH, Feijen J, Dankert J. Thrombocidins, microbicidal proteins from human blood platelets, are C-terminal deletion products of CXC chemokines. J Biol Chem 275: 20374–20381, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levy BD, Serhan CN. Resolution of acute inflammation in the lung. Annu Rev Physiol 76: 467–492, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 678–689, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li G, Malinchoc M, Cartin-Ceba R, Venkata CV, Kor DJ, Peters SG, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O. Eight-year trend of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 59–66, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X, Li C, Liang W, Bi Y, Chen M, Dong S. Protectin D1 promotes resolution of inflammation in a murine model of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via enhancing neutrophil apoptosis. Chin Med J (Engl) 127: 810–814, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ling Y, Cao X, Yu Z, Ruan C. Circulating dendritic cells subsets and CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in adult patients with chronic ITP before and after treatment with high-dose dexamethasome. Eur J Haematol 79: 310–316, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu B, Zhao H, Poon MC, Han Z, Gu D, Xu M, Jia H, Yang R, Han ZC. Abnormality of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Haematol 78: 139–143, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Looney MR, Nguyen JX, Hu Y, Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA, Matthay MA. Platelet depletion and aspirin treatment protect mice in a two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 119: 3450–3461, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madach K, Aladzsity I, Szilagyi A, Fust G, Gal J, Penzes I, Prohaszka Z. 4G/5G polymorphism of PAI-1 gene is associated with multiple organ dysfunction and septic shock in pneumonia induced severe sepsis: prospective, observational, genetic study. Crit Care 14: R79, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maniatis NA, Kotanidou A, Catravas JD, Orfanos SE. Endothelial pathomechanisms in acute lung injury. Vasc Pharmacol 49: 119–133, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mazzeffi M, Kassa W, Gammie J, Tanaka K, Roman P, Zhan M, Griffith B, Rock P. Preoperative aspirin use and lung injury after aortic valve replacement surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Anesth Analg 121: 271–277, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMahon B, Mitchell S, Brady HR, Godson C. Lipoxins: revelations on resolution. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22: 391–395, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McMorran BJ, Marshall VM, de Graaf C, Drysdale KE, Shabbar M, Smyth GK, Corbin JE, Alexander WS, Foote SJ. Platelets kill intraerythrocytic malarial parasites and mediate survival to infection. Science 323: 797–800, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McVey M, Tabuchi A, Kuebler WM. Microparticles and acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L364–L381, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mehta D, Ravindran K, Kuebler WM. Novel regulators of endothelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L924–L935, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meyer NJ, Feng R, Li M, Zhao Y, Sheu CC, Tejera P, Gallop R, Bellamy S, Rushefski M, Lanken PN, Aplenc R, O'Keefe GE, Wurfel MM, Christiani DC, Christie JD. IL1RN coding variant is associated with lower risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome and increased plasma IL-1 receptor antagonist. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 950–959, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meyer NJ, Li M, Feng R, Bradfield J, Gallop R, Bellamy S, Fuchs BD, Lanken PN, Albelda SM, Rushefski M, Aplenc R, Abramova H, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Beers MF, Calfee CS, Cohen MJ, Pittet JF, Christiani DC, O'Keefe GE, Ware LB, May AK, Wurfel MM, Hakonarson H, Christie JD. ANGPT2 genetic variant is associated with trauma-associated acute lung injury and altered plasma angiopoietin-2 isoform ratio. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 1344–1353, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitchell S, Thomas G, Harvey K, Cottell D, Reville K, Berlasconi G, Petasis NA, Erwig L, Rees AJ, Savill J, Brady HR, Godson C. Lipoxins, aspirin-triggered epi-lipoxins, lipoxin stable analogues, and the resolution of inflammation: stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2497–2507, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morris T, Stables M, Hobbs A, de Souza P, Colville-Nash P, Warner T, Newson J, Bellingan G, Gilroy DW. Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans. J Immunol 183: 2089–2096, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Narasaraju T, Yang E, Samy RP, Ng HH, Poh WP, Liew AA, Phoon MC, van Rooijen N, Chow VT. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to acute lung injury of influenza pneumonitis. Am J Pathol 179: 199–210, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 354: 2564–2575, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neumann FJ, Zohlnhofer D, Fakhoury L, Ott I, Gawaz M, Schomig A. Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade on platelet-leukocyte interaction and surface expression of the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 34: 1420–1426, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Neal HR Jr, Koyama T, Koehler EA, Siew E, Curtis BR, Fremont RD, May AK, Bernard GR, Ware LB. Prehospital statin and aspirin use and the prevalence of severe sepsis and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 39: 1343–1350, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oh SF, Pillai PS, Recchiuti A, Yang R, Serhan CN. Pro-resolving actions and stereoselective biosynthesis of 18S E-series resolvins in human leukocytes and murine inflammation. J Clin Invest 121: 569–581, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ong T, McClintock DE, Kallet RH, Ware LB, Matthay MA, Liu KD. Ratio of angiopoietin-2 to angiopoietin-1 as a predictor of mortality in acute lung injury patients. Crit Care Med 38: 1845–1851, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, Jaber S, Arnal JM, Perez D, Seghboyan JM, Constantin JM, Courant P, Lefrant JY, Guerin C, Prat G, Morange S, Roch A, Investigators AS. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 363: 1107–1116, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, Ancukiewicz M, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP; NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Trials Network. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 33: 1–6; discussion 230–232, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Persson CG, Uller L. Resolution of cell-mediated airways diseases. Respir Res 11: 75, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Puneet P, Moochhala S, Bhatia M. Chemokines in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L3–L15, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 336: 973–979, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rogers AJ, Matthay MA. Applying metabolomics to uncover novel biology in ARDS. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L957–L961, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 353: 1685–1693, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 264–274, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Serhan CN, Chiang N. Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: agonists of resolution. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13: 632–640, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Serhan CN, Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. Lipoxins: novel series of biologically active compounds formed from arachidonic acid in human leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 5335–5339, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, Moussignac RL. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med 196: 1025–1037, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shang Y, Yao S. Pro-resolution of inflammation: a potential strategy for treatment of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chin Med J 127: 801–802, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singbartl K, Forlow SB, Ley K. Platelet, but not endothelial, P-selectin is critical for neutrophil-mediated acute postischemic renal failure. FASEB J 15: 2337–2344, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sprague DL, Elzey BD, Crist SA, Waldschmidt TJ, Jensen RJ, Ratliff TL. Platelet-mediated modulation of adaptive immunity: unique delivery of CD154 signal by platelet-derived membrane vesicles. Blood 111: 5028–5036, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takeda T, Hoshida S, Nishino M, Tanouchi J, Otsu K, Hori M. Relationship between effects of statins, aspirin and angiotensin II modulators on high-sensitive C-reactive protein levels. Atherosclerosis 169: 155–158, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Villar J, Blanco J, Anon JM, Santos-Bouza A, Blanch L, Ambros A, Gandia F, Carriedo D, Mosteiro F, Basaldua S, Fernandez RL, Kacmarek RM; ALIEN Network. The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med 37: 1932–1941, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ware LB, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, Parsons PE, Matthay MA. Significance of von Willebrand factor in septic and nonseptic patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 766–772, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1334–1349, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ware LB, Matthay MA, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Januzzi JL, Eisner MD; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Trials Network. Pathogenetic and prognostic significance of altered coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 35: 1821–1828, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wei Y, Wang Z, Su L, Chen F, Tejera P, Bajwa EK, Wurfel MM, Lin X, Christiani DC. Platelet count mediates the contribution of a genetic variant in LRRC16A to ARDS risk. Chest 147: 607–617, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets in lung biology. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 569–591, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Williams AE, Chambers RC. The mercurial nature of neutrophils: still an enigma in ARDS? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L217–L230, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang J, Furie BC, Furie B. The biology of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1: its role as a selectin counterreceptor in leukocyte-endothelial and leukocyte-platelet interaction. Thromb Haemost 81: 1–7, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yeaman MR. Platelets: at the nexus of antimicrobial defence. Nat Rev Microbiol 12: 426–437, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yiming MT, Lederer DJ, Sun L, Huertas A, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya S. Platelets enhance endothelial adhesiveness in high tidal volume ventilation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 39: 569–575, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zarbock A, Ley K. The role of platelets in acute lung injury (ALI). Front Biosci 14: 150–158, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zarbock A, Singbartl K, Ley K. Complete reversal of acid-induced acute lung injury by blocking of platelet-neutrophil aggregation. J Clin Invest 116: 3211–3219, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zimmerman GA. Thinking small, but with big league consequences: procoagulant microparticles in the alveolar space. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1033–L1034, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]