Abstract

RNAs have diverse structures that include bulges and internal loops able to form tertiary contacts or serve as ligand binding sites. The recent increase in structural and functional information related to RNAs has put them in the limelight as a drug target for small molecule therapy. In addition, the recognition of the marked difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic rRNA has led to the development of antibiotics that specifically target bacterial rRNA, reduce protein translation and thereby inhibit bacterial growth. To facilitate the development of new antibiotics targeting RNA, we here review the literature concerning such antibiotics, mRNA, riboswitch and tRNA and the key methodologies used for their screening.

KEY WORDS: RNA, Antibiotics, Drug targeting, Bacteria

Graphical abstract

Many antibiotics are known to target ribosomal RNA (rRNA) in prokaryotes to inhibit the growth of bacteria. In order to facilitate the discovery of improved antibiotics targeting RNA, we describe the secondary structures of partial rRNA and indicate the binding sites for tetracycline, puromycin, lincomycin and other antibiotics. With the development of new drug discovery technologies, targeting RNA for better antibiotics is emerging as a new frontier in drug discovery.

1. Introduction

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the major genetic material in eukaryotes and generally exists in the form of double-stranded helices1. In contrast, ribonucleic acid (RNA) can fold into numberless tertiary structures that reflect its diverse functions. Thus it serves as the genetic material in some viruses, as the mediator of genetic information from DNA to protein, as the structural component in many ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) and, in some cases, as a catalyst2. RNA is usually associated with RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) which serve to either protect, stabilize or transport it and regulate its interaction with other molecules3, 4. RNA plays many crucial roles in protein synthesis, transcriptional regulation and retroviral replication that make it a prime target for drug action.

The recent publication of high resolution crystal structures of prokaryotic rRNA subunits has transformed our understanding of RNA5, 6, 7, 8. The structures of RNA alone9, 10 and of RNA–protein complexes11 reveal a variety of tertiary structures and patterns of RNA–protein interaction. RNA can fold into complex three-dimensional structures comprising loops, pseudoknots, bulges and turns which afford specific binding sites for small molecules12. Compared to DNA, RNA is not only more flexible but lacks repair mechanisms which enhance its susceptibility to the action of therapeutics13. These include both natural and synthetic compounds that can influence the biological activity of RNA by changing its configuration or inhibiting its catalytic function13, 14.

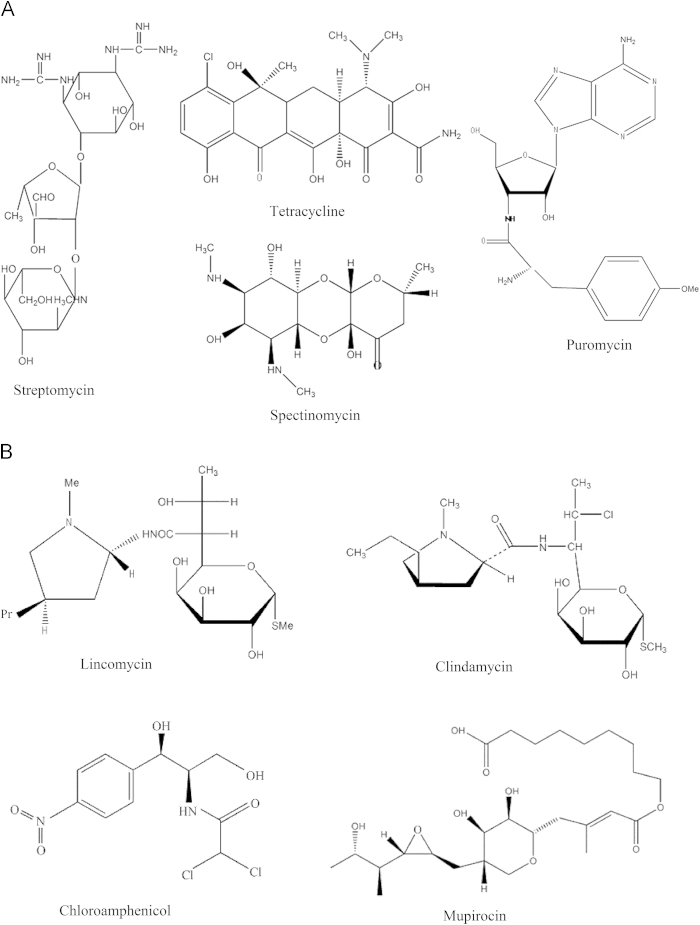

Many antibiotics are known to target rRNA in prokaryotes and thereby alter protein translation15, 16. Their diverse structures (Fig. 1A and B) witness both to the importance attached to this class of drugs and to the long period of their development since their discovery in the 1930s. Concomitant with the marketing of powerful antibiotics has emerged the phenomenon of antibiotic resistance which poses a serious threat to human health. The recent slow-down in the pace of novel antibiotic development17, 18 has further complicated the global health issue. However, antibiotics remain an attractive area for investment and represent the third largest therapeutic area with global financing of more than $34 billion in 200619. To assist in the discovery of new antibiotics, we here summarize the most commonly used drugs targeting bacterial rRNA in clinical development.

Figure 1.

The structures of antibiotic drugs (streptomycin, spectinomycin, tetracycline, and puromycin) whose mechanism of action is related to rRNA. A: Streptomycin, spectinomycin and tetracycline target bacterial 16S rRNA; puromycin resembles the 3′ end of the aminoacylated tRNA. B: Lincomycin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol target bacterial 23S rRNA; mupirocin targets aminoacyl tRNA synthetase.

2. Antibiotic drugs targeting rRNA

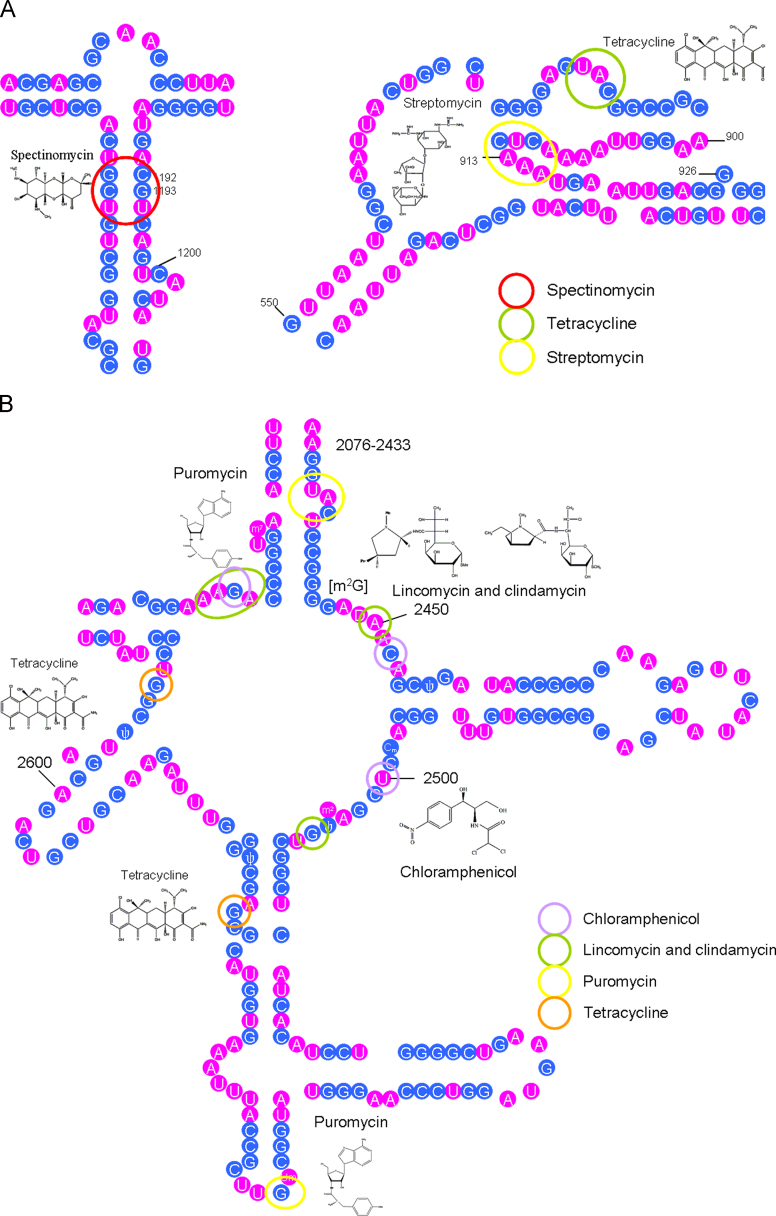

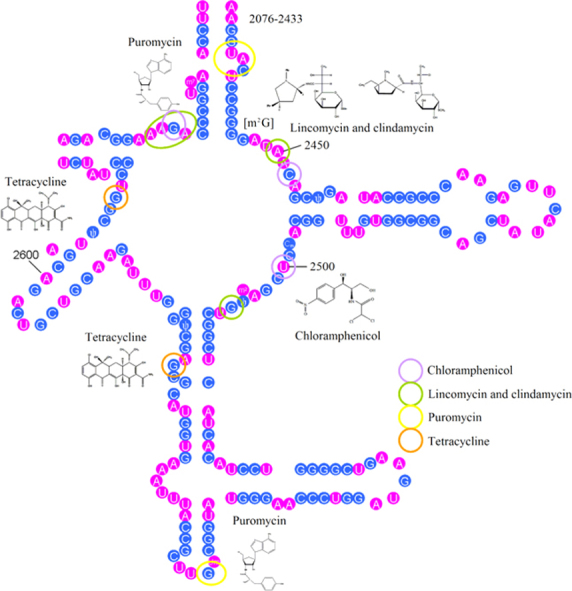

rRNA is the most commonly exploited RNA target for small molecules. The bacterial ribosome comprises 30S and 50S ribonucleoprotein subunits, contains a number of binding sites for known antibiotics and is an attractive target for novel antibacterial agents. The large difference between prokaryotic and eucaryotic rRNA enables rRNA-targeting against a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacteria20. Bacterial ribosomes have two ribonucleoprotein subunits of which approximately two-thirds are RNA. The bacterial rRNA includes 5S, 16S and 23S rRNA, the smallest (5S rRNA) being a ~120 nt RNA. The smaller 30S subunit contains a single ~1500 nt RNA (16S rRNA) and about 20 different proteins while the larger 50S subunit contains a ~2900 nt RNA (23S rRNA) and about 30 different proteins21. Recently, the application of X-ray crystallography has elucidated many antibiotic-binding sites on the ribosomal subunit22, 23 facilitating the design of novel antibiotics Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

A: The secondary structures of partial 16S rRNA (numbers indicate nucleotide positions). Nucleotides interacting with spectinomycin, tetracycline and streptomycin are marked with red, green and yellow circles, respectively. B: The secondary structures of partial 23S rRNA. Nucleotides interacting with chloramphenicol, lincomycin and clindamycin, puromycin and tetracycline are marked with purple, green, yellow, and red circles, respectively.

2.1. Aminoglycoside antibiotics

Aminoglycosides are a group of well-known antibiotics that have been used successfully for over half a century. Streptomycin and spectinomycin are typical examples which function by binding to specific sites on prokaryotic rRNA and affecting the fidelity of protein synthesis. The rRNA aminoacyl-tRNA site (rRNA A-site) is a major target for aminoglycosides which, because of the difference between prokaryotic 16S and human 18S rRNA, selectively kills bacterial cells24. Binding of drug to the 16S subunit near the A-site of the 30S subunit leads to a decrease in translational accuracy and inhibition of the translocation of the ribosome23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29. Direct binding to 16S rRNA has been demonstrated by NMR27, mass spectroscopy29, surface plasmon resonance28 and X-ray crystallography23.

The therapeutic and adverse effects of the aminoglycosides have been intensively studied. The main issue in clinical practice relates to their toxicity and the rapid increase in the emergence of resistant strains. Hopefully, modification and reconstruction of sugar moieties will lead to new aminoglycoside derivatives that will overcome the undesirable properties of the naturally occurring compounds30. A small library of four aminoglycosides that bind to a 16384-member bacterial rRNA A-site-like internal loop has been established to recognize the RNA motifs using two-dimensional combinatorial screening (2DCS). This may enable the rational and modular design of small molecules targeting RNA31.

2.1.1. Streptomycin

Streptomycin disturbs several steps of protein synthesis leading to translational errors and slowdown of translocation32, 33, 34, 35. It binds firmly to a single site on 16S rRNA36, 37, 38 without binding to the ribonucleoprotein39 as supported by footprinting and mutation studies. Footprinting studies showed that streptomycin protects specific residues of 16S rRNA within the 30S subunit40 and can be linked to specific portions of 16S rRNA41. Moreover, a mutation in Euglena chloroplast 16S rRNA resulted in streptomycin resistance42 and mutations in different regions of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA changed the ribosomal response to streptomycin43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. Streptomycin also interacts with ribosomal proteins in the 30S subunit49, 50 and mutations in S4, S5 and S12 ribosomal proteins are shown to influence its binding51.

Streptomycin can bind to E. coli 16S rRNA in the absence of ribosomal proteins and can protect bases in the decoding center from dimethyl sulfate (DMS) attack52. These interactions were evaluated in the classic high ionic strength buffer (20 mmol/L MgCl2, and 300 mmol/L KCl) used to separate active 30S subunits from 16S rRNA and ribosomal proteins. A similar set of bases was protected by streptomycin in RNA fragments corresponding to 16S rRNA. The magnesium ion is indispensable for the protection of the decoding analog afforded by streptomycin.

2.1.2. Spectinomycin

Spectinomycin is an aminocyclitol antibiotic produced by Streptomyces spectabilis which inhibits the growth of many Gram-negative bacteria and is particularly useful in treating gonorrhea. Chemical footprinting has demonstrated that spectinomycin binds to the N-7 position of E. coli 16S rRNA40 and the fact that several mutations in RNA and protein lead to spectinomycin resistance implicates a probable binding site in 16S rRNA53. Such binding may block the attachment of elongation factor G and thereby prevent the translocation of peptidyl-tRNAs from the ribosomal A-site to the P-site. The A(aminoacyl)-site close to the 3′-end of 16S rRNA is highly important in the decoding process such that binding of an aminoglycoside leads to erroneous protein synthesis and bacterial death. A set of overlapping, complementary 2′-O-methyl (OMe) 10-mer oligoribonucleotides was used to target the A-site on purified 30S ribosomal subunits from E. coli and shown to be almost ideal inhibitors of in vitro translation. However, the correlation of inhibition activity with binding strength to the A-site was limited54.

The X-ray crystallographic structure of the complex between spectinomycin and the 30S subunit of Thermus thermophilus confirms that the antibiotic-binding site is in the minor groove near the end of helix 34 of 16S rRNA23. Spectinomycin can form a stable complex with multiple RNA bases via hydrogen bonding suggesting that other RNA structures may serve as binding sites for spectinomycin either through homology to helix 34 or by different ensembles of interactions. It has been shown that over-expression of 16S rRNA fragments containing helix 34 can induce some resistance to spectinomycin in vivo55.

2.2. Tetracycline

Tetracycline inhibits binding of RNA to ribosomes56 mainly by influencing binding to the A-site although some reports implicate binding of Ac-Phe-tRNA to the P-site57, 58. A strong binding site exists on the 30S subunit and a lot of weaker sites on the 30S and 50S subunits59, 60, 61. Tetracycline may incorporate mainly into ribosomal proteins62, 63 since, in the absence of ribonucleoprotein, 16S RNA and the proteins S3, S7, S8, S14 and S19 show high affinity for tetracycline64 particularly S760. In addition, using a photoreactive benzophenone derivative of tRNA [3-(4-benzoylphenyl)propionyl-phenylalanine transfer RNA (BP-Phe-tRNA)], the photoreaction of 23S RNA was completely inhibited by tetracycline and tetracycline itself interacted efficiently with the loop V region of 23S RNA65, 66. 16S RNA and 23S RNA are targets of tetracycline and activity data from crosslinked subunits has shown that tetracycline crosslinks with 16S RNA at the strong binding site67.

2.3. Lincomycin and clindamycin

Lincomycin is a lincosamide antibiotic which, together with its derivative, clindamycin (7-chloro-7-deoxylincomycin), inhibits bacterial growth by preventing peptide bond formation15, 68. The two drugs act by targeting the peptidyl transferase loop in domain V of 23S rRNA of the 50S ribosomal subunit which is the site of peptide bond formation. The peptidyl tranferase loop has a complex tertiary structure probably containing the adjacent hairpin loop69, 70. The fact that a transition mutation at position 2032 leads to clindamycin resistance in E. coli and lincomycin resistance in tobacco chloroplast supports this mechanism of action. The fact that clindamycin is more potent than lincosamide in inhibiting the growth of Gram negative bacteria is probably the result of its higher lipid solubility that enables it to more readily penetrate the bacterial outer membrane and bind at the same ribosomal target site. In vitro chemical footprinting indicates that the two antibiotics interact with 23S rRNA in E. coli ribosomes71.

2.4. Chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is a broad spectrum antibiotic which acts as a potent inhibitor of bacterial protein biosynthesis. It has a long clinical history but bacterial resistance is common. Chloramphenicol footprinting studies with specific nucleotides has revealed the binding sites72, 73 to be on the 50S ribosomal subunit where chloramphenicol interacts with the central loop of 23S rRNA domain V to inhibit peptidyl transferase activity68, 71, 72. Details of the binding to the 50S subunits in Deinococcus radiodurans and Haloarcula marismortui have been revealed by X-ray studies74, 75. Mutations in RNA can affect chloramphenicol binding76, 77.

3. The possibility of targeting with bacterial messenger RNA (mRNA)

Some novel drugs to target eukaryotic mRNAs are now being developed. Although the structure of mRNA is less complicated than that of rRNA, it still incorporates some special structures such as hairpins and pseudoknots that provide binding sites for small molecules. For example, the iron response element (IRE) present in several mRNAs involved in iron homeostasis78 and identified in Alzheimer׳s amyloid precursor protein is considered to be a target for small molecules. Another is the non-structured AU-rich element (ARE) that spatiotemporally regulates mRNA translation and stability. Some of these interactions are critical for physiological processes and are being explored as targets for drug discovery78.

Certain mRNAs also use allosteric control to mediate regulatory responses79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84. For example, the mRNAs encoding enzymes involved in thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis in E. coli can bind to thiamine or its pyrophosphate derivative without the need for protein cofactors85. In addition, bacterial riboswitches that consist of structured RNA domains usually residing at the 5′ untranslated region of mRNAs can directly bind specific metabolites and serve as logic gates regulating their own expression without the need for any regulatory proteins. RNA switches may serve as novel targets for drug discovery since they are widely used by bacteria to sense changes in cell physiology and to regulate metabolic pathways. In depth information on this topic is available in the literature86, 87, 88.

Notwithstanding the above, there are big differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic mRNAs. These include: (1) the fact that prokaryotic mRNA does not need to be processed or transported so that translation by the ribosome can begin immediately after the end of transcription or coupled with transcription. Splicing of pre-messenger RNA into mature messenger RNA is an essential step for the expression of most genes in eukaryotes and is being employed for disease therapy89; (2) the fact that, in general, the lifespan of prokaryotic mRNA is much shorter than that of eukaryotic mRNA because the absence of a 5′ cap and 3′ polyA in prokaryotic mRNA enables its immediate degradation by exonuclease.

4. Antibiotics relevant to bacterial tRNA

4.1. Puromycin

Puromycin is an aminonucleoside antibiotic derived from Streptomyces alboniger which causes premature chain termination during translation in the ribosome. Part of the puromycin molecule resembles the 3′ end of the aminoacylated tRNA90 such that it enters the A-site and transfers to the growing chain leading to an immature puromycylated chain and its premature release91. However, the lack of selectivity of puromycin makes it unsuitable as an antibiotic and it is now mainly used as a biochemical tool to study protein synthesis. It is also under investigation as an anticancer drug92, 93.

4.2. Mupirocin

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetase (aaRSs) has been recognized as a useful drug target and many natural compounds specifically target it to inhibit bacterial growth. In fact there are some 20 essential aaRSs, each of which may represent a potential target for novel antibiotics. However, mupirocin (pseudomonic acid A) is the only marketed drug that targets this enzyme. Mupirocin exhibits good activity against Coagulase-negative Enterococcus faecium, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae 94. It has also been shown in in vitro studies to inhibit the growth of pathogenic fungi such as dermatophytes. Recent genomic and biochemical research has provided a wealth of information relevant to aaRSs including their crystal structures and active sites. Clearly they represent promising targets for novel antibiotics95.

Mupirocin inhibits iso-leucyl-tRNA synthetase (IleRS) and represents the starting point for the development of other aaRS inhibitors. Pseudomonas fluorescens has a 74-kb gene cluster encoding mupirocin which includes polyketide synthetase and a fatty acid synthetase system96, 97. Mupirocin is a secondary metabolite produced during the late stationary phase98 which inhibits protein synthesis by specifically binding to bacterial IleRS and inhibiting the formation of Ile-tRNA. Selectivity studies have demonstrated that mupirocin inhibits bacterial, archaeal and fungal IleRS but not their mammalian orthologs99. There are two genes (ileRS1 and ileRS2) in P. fluorescens which display remarkable differences100. IleRS2 has no sensitivity to mupirocin and exhibits eukaryotic features suggesting that, in P. fluorescens, the ileRS2 gene functions to protect the bacteria from mupirocin attack100. A mutation in E. coli thrS, a Thr-tRNA ligase, can resist an inhibitor of deacetylase LpxC, one of the most promising targets for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections101. Structural and energetic aspects of the binding of aristololactam-β-d-glucoside and daunomycin to tRNA(phe) have been investigated using various biophysical techniques102.

5. Techniques crucial for the discovery of drugs targeting RNA

Great strides have been made in the discovery of drugs targeting RNA. High-resolution NMR, electrospray mass spectroscopy (ESI-MS), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), together with other technologies have facilitated discovery in this field. For example, the structure of a 27 nucleotide RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic has been determined by NMR spectroscopy27; a technique based on ESI-MS (IBIS Therapeutics) can screen tens of thousands of compounds in one day29, 103 but its high cost limits its wider application; SPR is a sensitive and convenient technique to monitor the binding to RNA of up to 100 small molecules per day.

There are also methods to establish the binding situation of small molecules to RNA in the absence of RNA-binding proteins. For example, the scintillation proximity assay (SPA) is a means of screening inhibitors of RNA–protein interaction12. The technique uses labeled complementary oligonucleotides to monitor the changes in the equilibrium between the folded and unfolded state of an RNA stem-loop structure produced by the binding of a small molecule104. In cells, the interaction between RNA and proteins can be measured using reporter gene fusion105. Moreover, a novel method to identify new compounds that disrupt the function of ribosomes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis106 has identified two compounds (T766 and T054) with potent specific activity against M. tuberculosis and low toxicity to mice and other bacterial strains.

6. The future of antibiotics targeting bacterial RNAs

The genomic revolution has revealed many RNAs as potential targets for novel antibiotic drugs. Targeting RNA is challenging and complementary to traditional drug discovery that focuses on proteins and may have some advantages. First, more sites are accessible at the RNA level while targeting proteins is usually restricted to their active sites. Secondly, it is cost-effective to subject RNAs to high-throughput screening. With developments in new drug discovery technologies, targeting RNAs for better antibiotics is emerging as a new frontier in drug discovery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81371851, 81071316, 81271882 and 81301394), the New Century Excellent Talents in Universities (No. NCET-11-0703), the National Megaprojects for Key Infectious Diseases (No. 2008ZX10003-006), an excellent Ph.D Thesis Fellowship of Southwestern University (Nos. kb2010017 and ky2011003), the Fundamental Research Fund for Central Universities (Nos. XDJK2011D006, XDJK2012D011, XDJK2012D007, XDJK2013D003 and XDJK2014D040), the Natural Science Foundation Project of CQ CSTC (No. CSTC 2010BB5002), the Chongqing Municipal Committee of Education for Postgraduate Excellence Program (No. YJG123104) and an Undergraduate Teaching Reform Program (No. 2013JY201).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Watson JD, Crick FH. A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons RW, Grunberg-Manago M. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1998. RNA structure and function. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai K, Mattaj IW, Hames B, Glover DM. Irl Press; Oxford: 1994. RNA–protein interactions. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cusack S. RNA–protein complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:66–73. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemons WM Jr., May JL, Wimberly BT, McCutcheon JP, Capel MS, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of a bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit at 5.5 A resolution. Nature. 1999;400:833–840. doi: 10.1038/23631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cate JH, Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Earnest TN, Noller HF. X-ray crystal structures of 70S ribosome functional complexes. Science. 1999;285:2095–2104. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5436.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tocilj A, Schlunzen F, Janell D, Gluhmann M, Hansen HA, Harms J. The small ribosomal subunit from Thermus thermophilus at 4.5A resolution: pattern fittings and the identification of a functional site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14252–14257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ban N, Nissen P, Hansen J, Capel M, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Placement of protein and RNA structures into a 5 A-resolution map of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Nature. 1999;400:841–847. doi: 10.1038/23641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferré-D׳Amaré AR, Doudna JA. RNA folds: insights from recent crystal structures. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:57–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batey RT, Rambo RP, Doudna JA. Tertiary motifs in RNA structure and folding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:2326–2343. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990816)38:16<2326::aid-anie2326>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draper DE. Themes in RNA-protein recognition. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:255–270. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaman GJ, Michiels PJ, van Boeckel CA. Targeting RNA: new opportunities to address drugless targets. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermann T, Westhof E. RNA as a drug target: chemical, modelling, and evolutionary tools. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1998;9:66–73. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(98)80086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afshar M, Prescott CD, Varani G. Structure-based and combinatorial search for new RNA-binding drugs. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gale EF, Cundliffe E, Reynolds PE, Richmond M, Waring M. Wiley; London: 1972. The molecular basis of antibiotic action. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spahn C, Prescott C. Throwing a spanner in the works: antibiotics and the translation apparatus. J Mol Med. 1996;74:423–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00217518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alekshun MN. New advances in antibiotic development and discovery. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:117–134. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE Jr., Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. Bad bugs need drugs: an update on the development pipeline from the antimicrobial availability task force of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:657–668. doi: 10.1086/499819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush K. Antibacterial drug discovery in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10 doi: 10.1111/j.1465-0691.2004.1005.x. Suppl 4:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard M, Frizzell RA, Bedwell DM. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore CFTR function by overcoming premature stop mutations. Nat Med. 1996;2:467–469. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore PB. The ribosome at atomic resolution. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3243–3250. doi: 10.1021/bi0029402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brodersen DE, Clemons WM Jr, Carter AP, Morgan-Warren RJ, Wimberly BT, Ramakrishnan V. The structural basis for the action of the antibiotics tetracycline, pactamycin, and hygromycin B on the 30S ribosomal subunit. Cell. 2000;103:1143–1154. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter AP, Clemons WM, Brodersen DE, Morgan-Warren RJ, Wimberly BT, Ramakrishnan V. Functional insights from the structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit and its interactions with antibiotics. Nature. 2000;407:340–348. doi: 10.1038/35030019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyun Ryu D, Rando RR. Aminoglycoside binding to human and bacterial A-site rRNA decoding region constructs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2601–2608. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ecker DJ, Griffey RH. RNA as a small-molecule drug target: doubling the value of genomics. Drug Discov Today. 1999;4:420–429. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas JR, Hergenrother PJ. Targeting RNA with small molecules. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1171–1224. doi: 10.1021/cr0681546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fourmy D, Recht MI, Blanchard SC, Puglisi JD. Structure of the A Site of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Science. 1996;274:1367–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong C-H, Hendrix M, Manning DD, Rosenbohm C, Greenberg WA. A library approach to the discovery of small molecules that recognize RNA: use of a 1, 3-hydroxyamine motif as core. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8319–8327. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffey RH, Hofstadler SA, Sannes-Lowery KA, Ecker DJ, Crooke ST. Determinants of aminoglycoside-binding specificity for rRNA by using mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10129–10133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J, Wang G, Zhang LH, Ye XS. Modifications of aminoglycoside antibiotics targeting RNA. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:279–316. doi: 10.1002/med.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran T, Disney MD. Two-dimensional combinatorial screening of a bacterial rRNA A-site-like motif library: defining privileged asymmetric internal loops that bind aminoglycosides. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1833–1842. doi: 10.1021/bi901998m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilgin N, Claesens F, Pahverk H, Ehrenberg M. Kinetic properties of Escherichia coli ribosomes with altered forms of S12. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:1011–1027. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90466-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis BD. Mechanism of bactericidal action of aminoglycosides. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:341–350. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.341-350.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karimi R, Ehrenberg M. Dissociation rates of peptidyl-tRNA from the P-site of E. coli ribosomes. EMBO J. 1996;15:1149–1154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powers T, Noller HF. Selective perturbation of G530 of 16S rRNA by translational miscoding agents and a streptomycin-dependence mutation in protein S12. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:156–172. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang F, Flaks JG. Binding of dihydrostreptomycin to Escherichia coli ribosomes: characteristics and equilibrium of the reaction. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972;2:294–307. doi: 10.1128/aac.2.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grisé-Miron L, Brakier-Gingras L. Effect of neomycin and protein S1 on the binding of streptomycin to the ribosome. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:643–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lando D, Cousin MA, Ojasoo T, Raymond JP. Paromomycin and dihydrostreptomycin binding to Escherichia coli ribosomes. Eur J Biochem. 1976;66:597–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biswas DK, Gorini L. The attachment site of streptomycin to the 30S ribosomal subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:2141–2144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.8.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moazed D, Noller HF. Interaction of antibiotics with functional sites in 16S ribosomal RNA. Nature. 1986;327:389–394. doi: 10.1038/327389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gravel M, Melancon P, Brakier-Gingras L. Cross-linking of streptomycin to the 16S ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6227–6232. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montandon PE, Nicolas P, Schümann P, Stutz E. Streptomycin-resistance of Euglena gracilis chloroplasts: identification of a point mutation in the 16S rRNA gene in an invariant position. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:4299–4310. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.12.4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frattali AL, Flynn MK, De Stasio EA, DahÍberg AE. Effects of mutagenesis of C912 in the streptomycin binding region of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) –Gene Struct Expr. 1990;1050:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90136-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leclerc D, Melançon P, Brakier-Gingras L. The interaction between streptomycin and ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 1991;73:1431–1438. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lodmell JS, Gutell RR, Dahlberg AE. Genetic and comparative analyses reveal an alternative secondary structure in the region of nt 912 of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10555–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinard R, Payant C, Melançon P, Brakier-Gingras L. The 5′proximal helix of 16S rRNA is involved in the binding of streptomycin to the ribosome. FASEB J. 1993;7:173–176. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powers T, Noller HF. A functional pseudoknot in 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1991;10:2203–2214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santer M, Santer U, Nurse K, Bakin A, Cunningham P, Zain M. Functional effects of a G to U base change at position 530 in a highly conserved loop of Escherichia coli 16S RNA. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5539–5547. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melancon P, Boileau G, Brakier-Gingras L. Cross-linking of streptomycin to the 30S subunit of Escherichia coli with phenyldiglyoxal. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6697–6703. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abad JP, Amils R. Location of the streptomycin ribosomal binding site explains its pleiotropic effects on protein biosynthesis. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1251–1260. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill WE. American Society for Microbiology; Washington DC: 1990. The ribosome: structure, function, and evolution. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spickler C, Brunelle MN, Brakier-Gingras L. Streptomycin binds to the decoding center of 16S ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:586–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilgin N, Richter AA, Ehrenberg M, Dahlberg AE, Kurland CG. Ribosomal RNA and protein mutants resistant to spectinomycin. EMBO J. 1990;9:735–739. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abelian A, Walsh AP, Lentzen G, Aboul-Ela F, Gait MJ. Targeting the A site RNA of the Escherichia coli ribosomal 30S subunit by 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides: a quantitative equilibrium dialysis binding assay and differential effects of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Biochem J. 2004;383:201–208. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thom G, Prescott CD. The selection in vivo and characterization of an RNA recognition motif for spectinomycin. Bioorg Med Chem. 1997;5:1081–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gottesman ME. Reaction of ribosome-bound peptidyl transfer ribonucleic acid with aminoacyl transfer ribonucleic acid or puromycin. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:5564–5571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epe B, Woolley P, Hornig H. Competition between tetracycline and tRNA at both P and A sites of the ribosome of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1987;213:443–447. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geigenmuller U, Nierhaus KH. Tetracycline can inhibit tRNA binding to the ribosomal P site as well as to the A site. Eur J Biochem. 1986;161:723–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Epe B, Woolley P. The binding of 6-demethylchlortetracycline to 70S, 50S and 30S ribosomal particles: a quantitative study by fluorescence anisotropy. EMBO J. 1984;3:121–126. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01771.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldman RA, Hasan T, Hall CC, Strycharz WA, Cooperman BS. Photoincorporation of tetracycline into Escherichia coli ribosomes. Identification of the major proteins photolabeled by native tetracycline and tetracycline photoproducts and implications for the inhibitory action of tetracycline on protein synthesis. Biochemistry. 1983;22:359–368. doi: 10.1021/bi00271a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tritton TR. Ribosome-tetracycline interactions. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4133–4138. doi: 10.1021/bi00637a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldman RA, Cooperman BS, Strycharz WA, Williams BA, Tritton TR. Photoincorporation of tetracycline into Escherichia coli ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 1980;118:113–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)81230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reboud AM, Dubost S, Reboud JP. Photoincorporation of tetracycline into rat-liver ribosomes and subunits. Eur J Biochem. 1982;124:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buck MA, Cooperman BS. Single protein omission reconstitution studies of tetracycline binding to the 30S subunit of Escherichia coli ribosomes. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5374–5379. doi: 10.1021/bi00474a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barta A, Steiner G, Brosius J, Noller HF, Kuechler E. Identification of a site on 23S ribosomal RNA located at the peptidyl transferase center. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3607–3611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steiner G, Kuechler E, Barta A. Photo-affinity labelling at the peptidyl transferase centre reveals two different positions for the A- and P-sites in domain V of 23S rRNA. EMBO J. 1988;7:3949–3955. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oehler R, Polacek N, Steiner G, Barta A. Interaction of tetracycline with RNA: photoincorporation into ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1219–1224. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vazquez D. Inhibitors of protein synthesis. FEBS Lett. 1974;40:S48–S62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80689-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Douthwaite S. Functional interactions within 23S rRNA involving the peptidyltransferase center. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1333–1338. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1333-1338.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doring T, Greuer B, Brimacombe R. The three-dimensional folding of ribosomal RNA; localization of a series of intra-RNA cross-links in 23S RNA induced by treatment of Escherichia coli 50S ribosomal subunits with bis-(2-chloroethyl)-methylamine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3517–3524. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Douthwaite S. Interaction of the antibiotics clindamycin and lincomycin with Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4717–4720. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.18.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moazed D, Noller HF. Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin B protect overlapping sites in the peptidyl transferase region of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 1987;69:879–884. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodriguez-Fonseca C, Amils R, Garrett RA. Fine structure of the peptidyl transferase centre on 23S-like rRNAs deduced from chemical probing of antibiotic-ribosome complexes. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:224–235. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schlunzen F, Zarivach R, Harms J, Bashan A, Tocilj A, Albrecht R. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature. 2001;413:814–821. doi: 10.1038/35101544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hansen JL, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Structures of five antibiotics bound at the peptidyl transferase center of the large ribosomal subunit. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Long KS, Porse BT. A conserved chloramphenicol binding site at the entrance to the ribosomal peptide exit tunnel. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:7208–7215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science. 2000;289:920–930. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Theil EC. Targeting mRNA to regulate iron and oxygen metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gold L, Brown D, He Y-y, Shtatland T, Singer BS, Wu Y. From oligonucleotide shapes to genomic SELEX: novel biological regulatory loops. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:59–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gold L, Singer B, He YY, Brody E. SELEX and the evolution of genomes. Curr Opin Genet Develop. 1997;7:848–851. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nou X, Kadner RJ. Adenosylcobalamin inhibits ribosome binding to btuB RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7190–7195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130013897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Jomantas J, Kozlov YI, Perumov DA. A conserved RNA structure element involved in the regulation of bacterial riboflavin synthesis genes. Trends Genet. 1999;15:439–442. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miranda-Ríos J, Navarro M, Soberón M. A conserved RNA structure (thi box) is involved in regulation of thiamin biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9736–9741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161168098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stormo GD, Ji Y. Do mRNAs act as direct sensors of small molecules to control their expression? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9465–9467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181334498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature. 2002;419:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Penchovsky R, Stoilova CC. Riboswitch-based antibacterial drug discovery using high-throughput screening methods. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2013;8:65–82. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.740455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jentzsch F, Hines JV. Interfacing medicinal chemistry with structural bioinformatics: implications for T box riboswitch RNA drug discovery. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl 2):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S2-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Feng X, Liu L, Duan X, Wang S. An engineered riboswitch as a potential gene-regulatory platform for reducing antibacterial drug resistance. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:173–175. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00980f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Havens MA, Duelli DM, Hastings ML., Targeting RNA. splicing for disease therapy. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: RNA. 2013;4:247–266. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vázquez D, Kleinzeller A. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 1979. Inhibitors of protein biosynthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pestka S. Inhibitors of ribosome functions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1971;25:487–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.25.100171.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jung JH, Sohn EJ, Shin EA, Lee D, Kim B, Jung DB. Melatonin suppresses the expression of 45S preribosomal RNA and upstream binding factor and enhances the antitumor activity of puromycin in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:879746. doi: 10.1155/2013/879746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soderlund G, Haarhaus M, Chisalita S, Arnqvist HJ. Inhibition of puromycin-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells by IGF-I occurs simultaneously with increased protein synthesis. Neoplasma. 2004;51:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sutherland R, Boon RJ, Griffin KE, Masters PJ, Slocombe B, White AR. Antibacterial activity of mupirocin (pseudomonic acid), a new antibiotic for topical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:495–498. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim S, Lee S, Choi EC, Choi S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their inhibitors as a novel family of antibiotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;61:278–288. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cooper SM, Laosripaiboon W, Rahman AS, Hothersall J, El-Sayed AK, Winfield C. Shift to Pseudomonic acid B production in P. fluorescens NCIMB10586 by mutation of mupirocin tailoring genes mupO, mupU, mupV, and macpE. Chem Biol. 2005;12:825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.El-Sayed AK, Hothersall J, Cooper SM, Stephens E, Simpson TJ, Thomas CM. Characterization of the mupirocin biosynthesis gene cluster from Pseudomonas fluorescens NCIMB 10586. Chem Biol. 2003;10:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.El-Sayed AK, Hothersall J, Thomas CM. Quorum-sensing-dependent regulation of biosynthesis of the polyketide antibiotic mupirocin in Pseudomonas fluorescens NCIMB 10586. Microbiology. 2001;147:2127–2139. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nakama T, Nureki O, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for the recognition of isoleucyl-adenylate and an antibiotic, mupirocin, by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47387–47393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yanagisawa T, Kawakami M. How does Pseudomonas fluorescens avoid suicide from its antibiotic pseudomonic acid? Evidence for two evolutionarily distinct isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases conferring self-defense. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25887–25894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zeng D, Zhao J, Chung HS, Guan Z, Raetz CR, Zhou P. Mutants resistant to LpxC inhibitors by rebalancing cellular homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5475–5486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Das A, Bhadra K, Suresh Kumar G. Targeting RNA by small molecules: comparative structural and thermodynamic aspects of aristololactam-beta-d-glucoside and daunomycin binding to tRNA(phe) PLoS One. 2011;6:e23186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Swayze EE, Jefferson EA, Sannes-Lowery KA, Blyn LB, Risen LM, Arakawa S. SAR by MS: a ligand based technique for drug lead discovery against structured RNA targets. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3816–3819. doi: 10.1021/jm0255466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Engineering precision RNA molecular switches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mei HY, Mack DP, Galan AA, Halim NS, Heldsinger A, Loo JA. Discovery of selective, small-molecule inhibitors of RNA complexes—1. The tat protein/TAR RNA complexes required for HIV-1 transcription. Bioorg Med Chem. 1997;5:1173–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin Y, Li Y, Zhu Y, Zhang J, Liu X, Jiang W. Identification of antituberculosis agents that target ribosomal protein interactions using a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17412–17417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110271109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]