Abstract

Quantifying nitrous oxide (N2O) fluxes, a potent greenhouse gas, from soils is necessary to improve our knowledge of terrestrial N2O losses. Developing universal sampling frequencies for calculating annual N2O fluxes is difficult, as fluxes are renowned for their high temporal variability. We demonstrate daily sampling was largely required to achieve annual N2O fluxes within 10% of the ‘best’ estimate for 28 annual datasets collected from three continents—Australia, Europe and Asia. Decreasing the regularity of measurements either under- or overestimated annual N2O fluxes, with a maximum overestimation of 935%. Measurement frequency was lowered using a sampling strategy based on environmental factors known to affect temporal variability, but still required sampling more than once a week. Consequently, uncertainty in current global terrestrial N2O budgets associated with the upscaling of field-based datasets can be decreased significantly using adequate sampling frequencies.

Scientists have been quantifying soil nitrous oxide (N2O) fluxes in the field for at least 60 years1. Interest in soil N2O fluxes originated from a desire to better understand the fate of soil nitrogen2,3. Efforts to measure soil N2O fluxes were further increased when N2O was recognized as a potent greenhouse gas (GHG) that also plays a significant role in the depletion of stratospheric ozone4,5. Quantifying annual soil N2O emissions, the dominating source for atmospheric N2O, has consequently become a priority for signatory countries to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, who are required to present national GHG inventories on an annual basis to the Conference of Parties ( http://unfccc.int).

Quantifying annual N2O fluxes from soils is challenging. Fluxes vary spatially, and differ from day-to-day (and within the day) in response to multiple factors that regulate N2O production, consumption and emission6. Manual (static) chambers are currently the most widely used technique for quantifying soil N2O fluxes. Chamber flux measurements are short-term (e.g., hourly), repeated usually in intervals of days to weeks, and are in turn integrated across time to finally calculate an annual losses. However, fluxes estimated using static chambers can be adversely affected by inadequate mixing of the headspace air, pressure changes, and increases in headspace gas concentration in response to changes to the natural concentration gradient between the soil and atmosphere7. Despite these documented short-comings, this approach is favored for N2O measurements as fluxes can be orders of magnitude smaller than CO2 fluxes and the accumulation of gas in the headspace leads to best results with respect to flux detection limit compared to, for instance, dynamic chamber or micrometeorological techniques8. Furthermore manual chambers are simple to use, relatively inexpensive, and can be deployed in small experimental plots so the effect of multiple treatments on soil N2O fluxes can be investigated simultaneously6. Temporal coverage is typically limited to weekly, bi-weekly or monthly measurements when using manual chambers9. However, manual chambers are likely to underestimate annual N2O fluxes if the frequency of measurements does not adequately characterize N2O emissions during the year, in particular peak emissions following N fertilizer applications, irrigation, soil re-wetting or spring-thaw events, which may contribute up to 70% of the total annual flux10,11,12.

Guidelines for sampling frequency to estimate annual N2O fluxes using manual chambers are not well defined for all land-uses and environments. Instead the approach often taken comes down to an “educated guess” and resource availability13. A number of studies have investigated the influence of sampling frequency on cumulative N2O fluxes, however with the exception of Liu et al.14 these studies have mainly used short-term N2O flux data sets (<1 year), and have been confined to a single study site in an agricultural setting9,15,16,17,18. These short-term studies have demonstrated that high frequency measurements should coincide with management practices likely to increase N2O fluxes, with less frequent measurements during the intervening periods. Yet, the effect of sampling frequency on annual N2O flux estimates requires investigation across a broader range of land-uses and climates.

The introduction of automated chambers has enabled researchers to better characterize temporal variation in N2O fluxes6. Although this technology is expensive and not available to all researchers, it does provide a unique opportunity to better assess how sampling frequency affects estimates of annual N2O fluxes. Such an analysis is particularly beneficial to those new to measuring in situ N2O fluxes from land and to those planning to investigate a previously unstudied land-use. Consequently, the objective of the following study was to investigate the effect of sampling frequency on estimates of annual soil N2O fluxes using 28 published datasets of subdaily N2O fluxes from a variety of different terrestrial ecosystems across the globe.

Results

Annual N2O fluxes calculated from the average daily fluxes, which is used here as the reference annual flux, varied from 0.03 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 to 8.1 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 (Table 1). The smallest annual flux was recorded for a sandy soil cropped to a grain legume in a semiarid environment11, while the greatest was from a loam soil cropped to tree fruit in a subtropical climate19. Daily N2O fluxes were highly variable within each dataset, but more so for some; the coefficient of variation (CV) of the mean daily N2O flux ranged from 78% for a subtropical rainforest to 913% for a semiarid soil planted to a grain legume. The variation in daily means was not related to the magnitude of the annual N2O flux (Table 1), but instead reflected the episodic nature of the daily fluxes for a particular study site (Fig. 1). We subsequently classified the data sets as having either moderate (CV > 50–100%), high (CV > 100–200%) or extreme (CV > 200%) ‘episodicity’ based on the CV of the mean daily flux (Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of data sets used to assess the effect of sampling frequency on estimated annual N2O fluxes.

| Location†, Year | Climate | Rainfall‡ (mm yr−1) | Soil C§ (g kg−1) | Soil texture§ | Land use | Annual datasets | Study period (days) | Annual flux (kg N2O-N ha−1yr−1) | Daily flux CV (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wongan Hills, Australia. 2009–2011 | Semiarid | 374 | 10 | Sand | Grain crop, rainfed,+/− lime,+/− N fertilizer | 8 | 364–371 | 0.03–0.07 | 380–913 | Barton et al.11 |

| Cunderdin, Australia. 2005–2009 | Semiarid | 368 | 9.8 | Sand | Grain crop, rainfed,+/- N fertilizer | 8 | 337–379 | 0.08–0.16 | 173–428 | Barton et al.10 Li et al.26 Barton et al.27 Barton et al.28 |

| Xilin, Inner Mongolia. 2007–2008 | Semiarid, cool temperate | 335 | 26 | Sandy loam | Steppe grassland, not grazed | 1 | 365 | 0.21 | 260 | Wolf et al.12 |

| Höglwald, Germany. 1996–1997 | Temperate | 850 | 22 | Silty clay | Spruce and beech forest (plantation) | 2 | 365 | 0.58–2.46 | 169–179 | Papen & Butterbach-Bahl (1999)29 Wu et al.30 |

| Kingsthorpe, Australia. 2009–2010 | Subtropical | 630 | 15 | Clay | Wheat-cotton crop, irrigated, N fertilizer | 3 | 334 | 2.61–2.93 | 181–235 | Scheer et al.31 Scheer et al.32 |

| Mooloolah Valley, Australia. 2007–2009 | Subtropical | 1709 | 28 | Loam | Pasture, mowed, not grazed | 2 | 365 | 1.16–2.12 | 155–172 | Rowlings et al.33 |

| Mooloolah Valley, Australia.2008–2009 | Subtropical | 1709 | 35 | Loam, silt loam | Rainforest (notophyll vine) | 1 | 365 | 0.48 | 78 | Rowlings et at.34 |

| Mooloolah Valley, Australia. 2007–2009 | Subtropical | 1709 | 27 | Loam | Tree crop (lychee) | 2 | 365 | 1.68–8.12 | 93 | Rowlings et at.19 |

| Bellenden Ker, Australia. 2001–2002 | Tropical | 4360 | 31 | Sandy loam | Rainforest (mesopyll vine) | 1 | 365 | 1.16 | 98 | Kiese et al.23 |

†Cunderdin, 31°36′S, 117°13′E; Wongan Hills, 30°89′S, 116°72′E; Höglwald 48°30′N, 11°10′E; Xilin 43° 33′ N, 116° 42.3′ E; Bellenden Ker, 17°16′S, 145°54′E; Kingsthorpe, 27°30′S, 151°46′E; Mooloolah Valley 26°75′ S, 152°93′ E

‡Long-term average value

§Surface soil (e.g., 0–15cm).

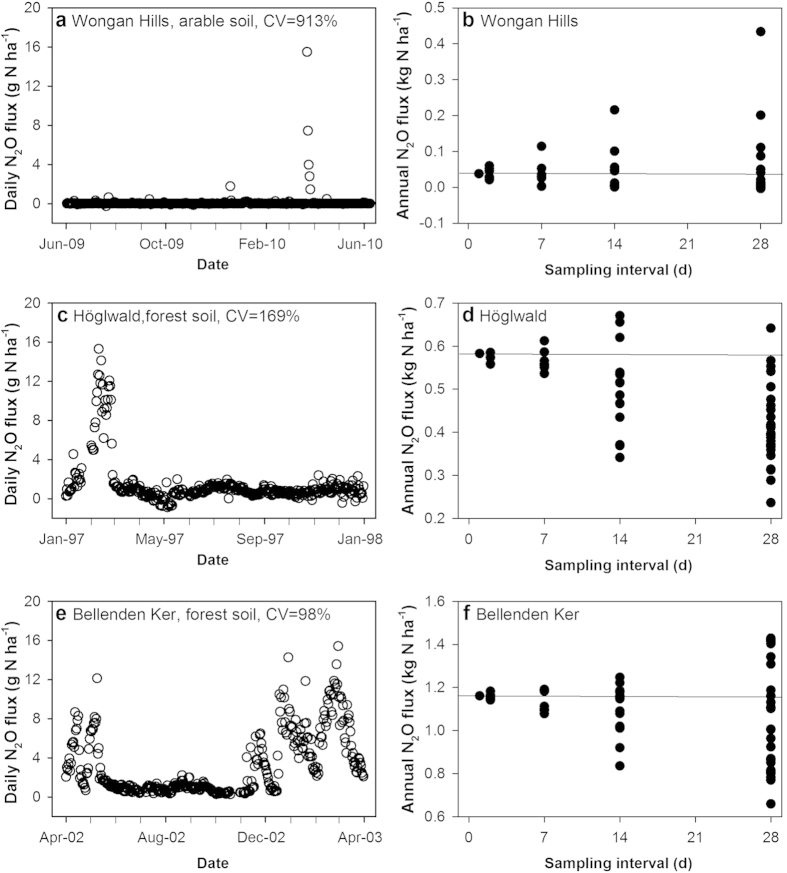

Figure 1. Daily N2O fluxes and the influence of sampling frequency on annual N2O fluxes.

The daily N2O flux (a,c,e) for the three data sets shown have varying coefficients of variation (CV), which influences the effect of sampling frequency on annual N2O fluxes (b,d,f). See Table 4 for description of sampling intervals.

Table 2. The relationship between the ‘episodicity’ of each study location and the minimum sampling frequency needed to meet a given accuracy.

| Location | Minimum sampling frequency |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodicity† | 10% accuracy | 0% accuracy | |

| Wongan Hills, Australia. | Extreme | Daily | Daily to 3 days a week |

| Cunderdin, Australia. | High to Extreme | Daily or 3 days a week | Daily to weekly |

| Xilin, Inner Mongolia. | Extreme | 3 days a week | Weekly |

| Höglwald, Germany. | High | 3 days a week | Weekly to bi-weekly |

| Kingsthorpe, Australia. | High to Extreme | Daily | Daily |

| Mooloolah Valley, (Pasture) Australia. | High | Daily to 3 days a week | 3 days a week to weekly |

| Mooloolah Valley, (Rainforest) Australia. | Moderate | 3 days a week | Bi-weekly |

| Mooloolah Valley, (Tree crop) Australia. | Moderate | 3 days a week | Weekly |

| Bellenden Ker, Australia. | Moderate | Weekly | Bi-weekly |

†Episodicity determined using coefficient of the mean daily flux (Table 1). Moderate, CV > 50–100%; high, CV > 100–200%; extreme, CV > 200%.

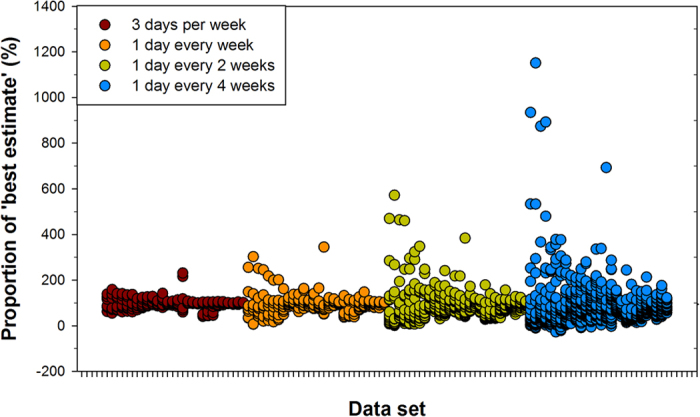

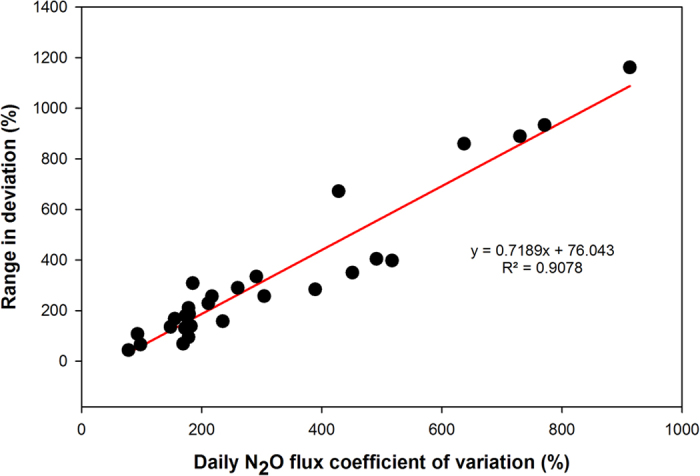

Increasing the interval between sampling days increased the variance in the estimated annual N2O fluxes, and hence decreased the accuracy of the estimate (Fig. 1). As the sampling frequency decreased, the deviation from the ‘best estimate’, or expected value obtained using all daily fluxes, increased and caused annual losses to be either over- or underestimated (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 1). Across all sites and sampling frequencies (n = 1568), 22% and 58% of annual emission values were more than 10% higher or lower, respectively, than the ‘best estimate’ annual flux. The extent that decreased sampling frequency increased the deviation from the reference annual N2O flux appeared to be largely related to the variability, or coefficient of variation, of the daily fluxes (Fig. 3). The greater the variation in daily N2O within a dataset, the greater the impact of decreasing the sampling frequency had on the accuracy of the estimated annual flux. For example, for a tropical rainforest (Bellenden Kerr) with a daily N2O flux CV of 98%, sampling every 28 days resulted in an annual N2O flux that was up to 1.2 times greater than the best estimate; whereas for cropped soil in a semiarid region with a daily N2O flux CV of 913%, sampling every 28 days resulted in an annual N2O flux that was up to 12 times greater than the best estimate (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. The proportion (%) of the ‘best estimate’ annual N2O flux estimated by each sampling frequency.

For each dataset (28), the average annual flux estimate (calculated from replicate chambers) for each sampling frequency (and each permutation, Table 4) was compared to the ‘best estimate’ flux calculated from the average daily fluxes (expressed as a %). The ‘best estimate’ was calculated using all daily fluxes. For each sampling frequency, the datasets are presented in the same order (from left to right in the above Figure) as that listed in Supplementary Table 1. Specific values for each dataset are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 3. Relationship between the coefficient of variation of the daily N2O flux and the deviation (range) from the ‘best estimate’ annual N2O flux.

For each dataset (28; represented as single point in the above Figure), the range in deviation was determined after comparing the annual N2O fluxes calculated from a sample interval of 4-weekly (every 28 days) with the ‘best estimate’ for each permutation (Table 4). The ‘best estimate’ was calculated using all daily fluxes. Specific values for each dataset are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

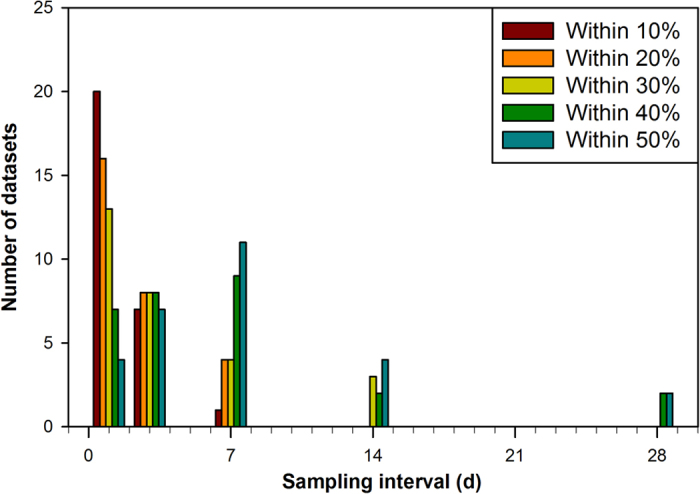

The minimum sampling frequency required to robustly estimate an annual N2O flux varied depending upon the ‘episodicity’ of the dataset and the required accuracy (Fig. 2; Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). Twenty, or 74%, of the datasets required daily sampling to achieve an annual N2O flux value within 10% of the best estimate (Fig. 4). In only one case (tropical rainforest, Bellenden Ker), and when the daily N2O flux CV was relatively low (98%), did weekly sampling result in annual N2O flux within 10% of the best estimate. Generally speaking, highly or extremely episodic data sets (CV > 100%) required sampling either daily or 3 days a week (Table 2). Lowering the desired accuracy decreased the required frequency of sampling, however 89% of the data sets still needed to be sampled at least weekly to achieve ±30% accuracy (Fig. 4). Lowering the level of accuracy to ±40% meant two datasets could be sampled once every 4 weeks (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Impact of sampling interval on estimating annual N2O fluxes at a given accuracy.

The number of datasets obtaining annual N2O fluxes at a given accuracy are listed as a function of sampling interval. Specific values for each datasets are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

Nitrous oxide emissions need to be measured daily to accurately determine annual N2O flux in environments where data has not previously been collated. Measuring N2O fluxes on a daily basis ensured that annual N2O fluxes were estimated within 10% of the expected value for all datasets in the present study. Although a similar result could be achieved in some instances (25%, or 7 datasets) by sampling 3 days a week, this still represents a highly regularly sampling regime. Our findings are consistent with others who have investigated the effects of sampling frequency on estimates of annual N2O fluxes. For example, a relatively frequent sampling regime (once every 2 to 3 days) was required to estimate cumulative losses within 10% of the expected cumulative loss from N-fertilized crops in China and the United States of America9,14. Our findings further confirm the importance of deploying automated chamber systems when determining annual N2O fluxes in previously unstudied environments, and when the drivers of temporal variability are not well understood.

The frequency of sampling required to accurately calculate an annual N2O flux will depend on the episodic nature of the N2O flux at the study site of interest, rather than the magnitude of the annual flux. This was particularly well demonstrated by studies conducted in semiarid environments of Australia and Inner Mongolia, where relatively low annual N2O losses ( ≤ 0.21 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 ) resulted from a limited number of elevated daily N2O fluxes during the year11,12. For example in a cropped soil in south-western Australia, 75 to 85% of the annual fluxes were attributed to isolated, short-lived summer rainfall events11. Understanding the underlying temporal variability of daily N2O fluxes is therefore likely to improve the efficacy of sampling regimes.

Sampling efficacy for determining annual N2O fluxes may be improved, and the regularity of sampling decreased, if N2O flux responses can be anticipated. This may occur if previous research has been conducted in a similar environment, or if preliminary work is undertaken to assess the temporal variability of N2O fluxes. In either case, refining the sampling regime will require some underlying understanding of temporal variation in the N2O flux and its regulation. Using this approach, we estimated annual N2O fluxes for three of our datasets (Fig. 1) based on the authors’ informed understanding of the factors driving daily losses. While we found the annual N2O fluxes estimated by the authors’ did not vary statistically from the ‘best’ estimate calculated using all daily fluxes, the informed sampling approach still required sampling to occur every 2 to 6 days depending on the dataset (Table 3). A number of short-term studies have also devised strategies for characterizing N2O fluxes in response to N inputs to cropping and grazed soils setting9,15,16,17,18. Notably, various authors used automated chambers to develop a sampling regime for measuring N2O emissions from temperate grasslands in response to ruminant urine deposition16 in New Zealand, N fertilized potato fields in Europe18, and rainfed cereal crops in subtropical Australia17; agricultural land use not captured in the present study. Interestingly, some of these authors recommended weekly sampling (with a higher frequency following anticipated N2O events), which is less frequent than our analysis would recommend for agricultural and non-agricultural study sites in the present study.

Table 3. Annual N2O fluxes for three contrasting study sites estimated using either an informed sampling strategy or from daily measurements.

| Location† | Best estimate | Informed sampling regime‡ |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual flux (kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1) | Annual flux (kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1) | No. measurements | |

| Wongan Hills, Australia. | 0.04 (0.0)a | 0.03 (0.0)a | 60 |

| Höglwald, Germany. | 0.58 (0.1)a | 0.64 (0.1)a | 83 |

| Bellenden Ker, Australia. | 1.16 (0.1)a | 1.35 (0.2)a | 156 |

Values represent means (and standard errors) of three to five replicates depending on the study site. Values followed by the same letter in the same row are not statistically different (P < 0.05).

†For further details see Table 1. Corresponds to data set numbers 2 (Wongan Hills), 19 (Höglwald) and 28 (Bellenden Ker) in Supplementary Table 1.

‡Informed sampling strategy for each location: Wongan Hills, N2O fluxes measured daily for five consecutive days when daily rainfall > 5 mm rainfall (December–June) or > 10 mm rainfall (July–November); Höglwald, N2O fluxes measured daily for seven days consecutive day when air temperature between −0.7 and 0.7 °C or if daily rainfall > 15 mm; Bellenden Ker, N2O fluxes measured daily for six days consecutive day when daily rainfall > 15 mm.

The uncertainty of current global N2O estimates maybe partly attributed to the sampling frequency of the datasets selected for inclusion in the analysis. Modelling of global soil N2O emissions has been largely derived from manual chambers measurements covering more than 300 days in a year20. However, less than a third of the 464 studies included in the metadata analysis by Stehfest and Bouwman20 measured N2O on at least a daily basis, with 50% of the data used collected 3 days a week, or less than weekly. Given the influence of sampling frequency on annual N2O fluxes in the present paper, it is likely that current global N2O values have not been accurately captured. Instead, we recommend that revision of global estimates using high frequency measurements (at least daily) or an ‘informed’ sampling approach for at least a year.

Finally, we recommend data from automated chambers should be continuously used to build on existing guidelines for use of manual chambers21. While the present study included and discussed a large number of datasets from a variety of climates, soils and land uses, there were a number of environments not represented. For example, grazed soils outside temperate climate, a broader range of horticultural soils, and non-agricultural soils in semiarid environments. We therefore encourage researchers utilizing automated chamber systems to determine annual N2O fluxes from soils, to in turn also utilize the data to investigate the impacts of sampling frequency on these losses.

Methods

Study sites

The meta-analysis included datasets from published research studies, and where N2O fluxes had been measured on a subdaily basis for approximately one year using automated chambers. Annual data sets were sourced from measurements in Australia, Germany, and Inner Mongolia, representing a variety of climates, soil types and land uses (Table 1). Climates ranged from semiarid (including a Mediterranean-type climate) to tropical, soil textures varied from sands to heavy clays, while land use included various agricultural production and forest systems. A number of study sites also included different treatments (Table 1). Consequently our meta-analysis included 28 sub-daily N2O datasets.

Automated chamber system

Nitrous oxide fluxes were measured at each study location using soil chambers connected to a fully automated system that enabled in situ determination of N2O fluxes. Details of the design and operation of the automated gas sampling systems have been described by Breuer et al.22 and Kiese et al.23. Briefly, the various systems consisted of a gas chromatograph (e.g., Texas Instruments, SRI 8610C) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD) for N2O analysis, an automated sampling unit for collecting and distributing gas samples, and a series of chambers (three to five replicates depending on the study site). Chambers (0.5 m × 0.5 m or 0.7 m × 0.7 m) were placed on metal bases inserted into the ground (0.05–0.1 m), and fitted with a top (0.15 m or 0.3 m in height) that could be automatically opened and closed by means of pneumatic actuators. The height of the chambers was progressively increased to accommodate crop growth at some study sites, with a maximum height of 0.95 m. Furthermore, in some instances the chambers were programmed to open if the air temperature in the chamber exceeded a set value, or if rain fell while the chambers were closed. The automated gas sampling unit enabled N2O to be monitored continuously, providing up to eight (hourly) emission rates per day. Specific N2O measurement details for each study site are described in the associated published papers (Table 1).

Evaluating sample frequency effects

The effect of sampling frequency on estimates of annual N2O-N fluxes was assessed using a modified jackknife technique24,25. Average daily flux measurements were calculated for each replicate chamber in each dataset from the sub-daily flux measurements as we did not consistently observe diurnal flux variations at each location. Each site’s daily flux population was subsequently subsampled daily, three times per week, weekly, bi-weekly and 4-weekly, and for each permutation of the time interval, for each dataset (Table 4). There were 7 to 28 jackknifed populations depending on the sampling frequency (Table 4). Estimates of annual N2O-N flux for a given chamber, site and frequency permutation were then calculated by linear interpolation and integration of daily fluxes with time. Missing daily N2O flux data was not replaced. The average annual flux estimate (calculated from replicate chambers) from each sampling frequency, and for each of the dataset, was then compared to the ‘best estimate’ annual flux calculated from the average daily fluxes (expressed as a %) so as to assess the accuracy of each of the sampling frequencies. An annual flux determined using an informed sampling regime (based on the authors’ understanding of the factors driving daily N2O fluxes) was also compared with the ‘best estimate’ annual flux using a general analysis of variance (Genstat for Windows, 14th Edition, VSN International).

Table 4. Description of sampling frequencies.

| Sampling frequency | Sampling interval (days) | Permutations | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 1 | 1 | Sunday |

| Monday | |||

| Tuesday etc | |||

| 3 days a week | 2 | 7 | Sunday-Tuesday-Thursday |

| Monday-Wednesday-Friday | |||

| Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday etc | |||

| 1 day a week (weekly) | 7 | 7 | Every Sunday |

| Every Monday | |||

| Every Tuesday etc | |||

| 1 day every 2 weeks (bi-weekly) | 14 | 14 | Every Sunday (week 1 of 2) |

| Every Sunday (week 2 of 2) | |||

| Every Monday (week 1 of 2) | |||

| Every Monday (week 2 of 2) etc | |||

| 1 day every 4 weeks (4-weekly) | 28 | 28 | Every Sunday (week 1 of 4) |

| Every Sunday (week 2 of 4) | |||

| Every Sunday (week 3 of 4) | |||

| Every Sunday (week 4 of 4) etc |

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Barton, L. et al. Sampling frequency affects estimates of annual nitrous oxide fluxes. Sci. Rep. 5, 15912; doi: 10.1038/srep15912 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the Australian Government’s Climate Change Research Program, Australian Research Council (DP0559791), Department of Agriculture & Food Western Australia, Grains & Research Development Corporation (GRDC), EU Integrating Activity (IA) project InGOS, the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCFAS) of CGIAR institutes and the German Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.B. had the main responsibility for the design and writing of the manuscript together with B.W. All co-authors participated, commented and provided contributions relevant to their own data and area of expertise.

References

- Arnold P. Losses of nitrous oxide from soil Journal of Soil Science 5, 116–128 (1954). [Google Scholar]

- Denmead O. Chamber systems for measuring nitrous oxide emission from soils in the field. Soil Sc. Soc. Am. J. 43, 89–95 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson G. & Mosier A. Improved Soil cover method for field measurement of nitrous oxide fluxes. Soil Sc. Soc. Am. J. 45, 311–316 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankara A., Daniel J. & Portmann R. Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326, 123–125 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen P. J. in Denitrification, nitrification, and atmospheric nitrous oxide (ed Delwiche C C ) 17–44 (John Wiley & Sons, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Butterbach-Bahl K., Baggs E., Dannenmann M., Kiese R. & Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: how well do we understand the processes and their controls? Phil Trans R Soc B 368, 20130122 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlatie M. et al. Comparison of static chambers to measure CH4 emissions from soils. Agr. Forest. Meteorol. 171–172, 124–136 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Denmead O. T. Approaches to measuring fluxes of methane and nitrous oxide between landscapes and the atmosphere. Plant Soil 309 309, 5–24 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Parkin T. B. Effect of sampling frequency on estimates of cumulative nitrous oxide emissions. J. Environ. Qual. 37, 1390–1395 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from a cropped soil in a semiarid climate. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 177–192 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Barton L., Murphy D. & Butterbach-Bahl K. Influence of crop rotation and liming on greenhouse gas emissions from a semiarid soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 167, 23–32 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wolf B. et al. Grazing-induced reduction of natural nitrous oxide release from continental steppe. Nature 464, 881–884 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S., Kimber S., Grace P. & Van Zweiten L. Improving the statistical preparation for measuring soil N2O flux by closed chamber. Sci. Total Environ. 465, 166–172 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. Nitrous oxide and nitric oxide emissions from an irrigated cotton field in Northern China. Plant Soil 332, 123–134 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. A. & Dobbie K. E. The impact of sampling frequency and sampling times on chamber-based measurements of N2O emissions from fertilized soils. Global Change Biol. 7, 933–945 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- van der Weeden T., Clough T. & Styles T. Using near-continuous measurements of N2O emission from urine-affected soil to guide manual gas sampling regimes. New Zeal. J. Agr. Res. 56, 60–76 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Reeves S. & Wang W. Optimum sampling time and frequency for measuring N2O emissions from a rain-fed cereal cropping system. Science of The Total Environment 530–531, 219–226, doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.117 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flessa H. et al. N2O and CH4 fluxes in potato fields: automated measurement, management effects and temporal variation. Geoderma 105, 307–325 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Rowlings D., Grace P., Scheer C. & Kiese R. Influence of nitrogen fertiliser application and timing on greenhousegas emissions from a lychee (Litchi chinensis) orchard in humid subtropical Australia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 179, 168–178 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Stehfest E. & Bouwman L. N2O and NO emission from agricultural fields and soils under natural vegetation: summarizing available measurement data and modeling of global annual emissions. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystem 74, 207–228 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- de Klein C. & Harvey M. Nitrous oxide chamber methodology guidelines. (Ministry for Primary Industries, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Breuer L., Papen H. & Butterbach-Bahl K. N2O emission from tropical forest soils of Australia. J. Geophys. Res. 105 26, 353–326,367 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Kiese R., Hewett B., Graham A. & Butterbach-Bahl K. Seasonal variability of N2O emissions and CH4 uptake by tropical rainforest soils of Queensland, Australia. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1043 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Computers and the theory of statistics: Thinking the unthinkable. SIAM Review 21, 460–480 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. & Gong G. A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross-validation. Am. Stat. 37, 36–48 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Barton L. & Chen D. Simulating response of N2O emissions to fertiliser N application and climatic variability from a rain-fed and wheat-cropped soil in Western Australia. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92, 1130–1143 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L., Murphy D. V., Kiese R. & Butterbach-Bahl K. Soil nitrous oxide and methane fluxes are low from a bioenergy crop (canola) grown in a semiarid climate. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2, 1–15 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Barton L., Butterbach-Bahl K., Kiese R. & Murphy D. Nitrous oxide fluxes from a grain-legume crop (narrow-leafed lupin) grown in a semiarid climate. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 1153–1166 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Papen H. & Butterbach-Bahl K. A 3-year continuous record of nitrogen trace gas fluxes from untreated and limed soil of a N-saturated spruce and beech forest ecosystem in Germany: 1. N2O emissions. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 18, 487–418,503 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. Environmental controls over soil–atmosphere exchange of N2O, NO and CO2 in a temperate Norway spruce forest. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24, 773–787 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Scheer C., Grace P., Rowlings D. & Payero J. Nitrous oxide emissions from irrigated wheat in Australia: impact of irrigation management. Plant Soil 359, 351–362 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Scheer C., Grace P., Rowlings D. & Payero J. Soil N2O and CO2 emissions from cotton in Australia under varying irrigation management. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystem 95, 43–56 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rowlings D., Grace P., Scheer C. & Liu S. Rainfall variability drives interannual variation in N2O emissions from a humid, subtropical pasture. Sci. Total Environ. 512–513, 8–18 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlings D., Grace P., Kiese R. & Weier K. Environmental factors controlling temporal and spatial variability in the soil-atmosphere exchange of CO2, CH4 and N2O from an Australian subtropical rainforest. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 726–738 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.