Abstract

Our previous work found that DMH1 (4-[6-(4-isopropoxyphenyl)pyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]quinoline) was a novel autophagy inhibitor. Here, we aimed to investigate the effects of DMH1 on chemotherapeutic drug-induced autophagy as well as the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs in different cancer cells. We found that DMH1 inhibited tamoxifen- and cispcis-diaminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP)-induced autophagy responses in MCF-7 and HeLa cells, and potentiated the anti-tumor activity of tamoxifen and CDDP for both cells. DMH1 inhibited 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced autophagy responses in MCF-7 and HeLa cells, but did not affect the anti-tumor activity of 5-FU for these two cell lines. DMH1 itself did not induce cell death in MCF-7 and HeLa cells, but inhibited the proliferation of these cells. In conclusion, DMH1 inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced autophagy response and the enhancement of efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs by DMH1 is dependent on the cell sensitivity to drugs.

KEY WORDS: Autophagy, Tamoxifen, 5-Fluorouracil, Cancer cells

Graphical abstract

DMH1 inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced autophagy response. The enhancement of chemotherapeutic drug efficacy by DMH1 is dependent on the cell sensitivity to the drugs, not the autophagy inhibition action.

1. Introduction

Autophagy is a physiologic process which functions to digest long-lived proteins and damaged organelles in order to sustain cellular metabolism. It has been reported that autophagy is involved in various diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, pathogen invasion, and muscle and liver disorders1. Currently, autophagy is considered as a “double-edged sword” that allows cells to survive during nutrient depletion2, yet excessive autophagy leads to programmed cell death3. In most conditions, there is a robust increase of autophagy responses in cancer cells treated by some chemotherapeutics, and pharmacological inhibition of autophagy potentiates the anti-tumor effects of chemotherapeutic drugs4, 5. However, several anti-tumor drugs such as lapatinib exert a growth inhibitory effect in hepatoma cells via inducing autophagic cell death6.

DMH1(4-[6-(4-isopropoxyphenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]quinoline) is a small molecular weight chemical which has been used as an inhibitor of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signal7. Recent studies showed that DMH1 promoted neurogenesis of hiPSCs and suppressed the growth and metastasis of lung cancer8, 9. Our previous work found that DMH1 inhibited cellular autophagy responses in a range of cell types; the underlying mechanisms included activation of the Akt pathway10. Since the pharmacological inhibition of autophagy sensitizes cancer cells to various cancer therapies, in the present study, we aimed to (1) study the effects of DMH1 on chemotherapeutic drug-induced autophagy response, and (2) study the effects of DMH1 on the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical reagents and antibodies

MCF-7 and HeLa cell lines were obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China. cis-Diaminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP), 5-FU, DMH1, anti-LC3B antibody were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tamoxifen was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (UK). MTT and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Amresco (USA). Dulbecco׳s modified Eagle׳s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Hyclone (USA). Live/dead viability/cytotoxicity assay kit and CFSE cell proliferation kit were obtained from Invitrogen. In situ cell death detection (TUNEL) kit was obtained from Roche. DAPI staining solution was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (China).

2.2. Cell culture

MCF-7 and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco׳s modified Eagle׳s medium/High Glucose (DMEM/High) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After the cells grew to appropriate density, they were treated with the chemotherapeutic drugs CDDP, tamoxifen and 5-fluorouracil, or together with DMH1 for 24 h. The time of treatment and the concentration of agents are specified in the figures and/or figure legends.

2.3. MTT assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with different drugs for appropriate time. Then 5 mg/mL MTT was added and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Medium was then removed and 200 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the crystal. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm with a plate reader (Tecan Infinite m200, Mannedorf, Switzerland).

2.4. Live and dead staining

The live/dead® viability/cytotoxicity assay kit (Invitrogen) was used to detect dead cells. Briefly, cells were grown on coverslips at a density of 3.75×104/mL and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were washed with PBS and stained according to the manufacturer׳s instructions. The labeled cells were photographed under a fluorescence microscope. The live cells fluoresce green and dead cells fluoresce red.

2.5. TUNEL staining

After three times PBS washing, treated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 sodium citrate buffer. Then an in situ cell death detection kits (Roche) were used to label apoptotic cells, and the nuclei were stained with DAPI. The numbers of total cells and TUNEL-positive cells were automatically counted by Image-Pro plus version. The apoptosis rate was defined as ratio of apoptotic cells to total cells.

2.6. Western blot

Detailed information was described in our previous works10. Western blot bands were quantified by using Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR) and Odyssey v3.0 software.

2.7. Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined by carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) staining. The cells were suspended in PBS contained 0.1% BSA and labeled for 10 min at 4 °C using 5 μmol/L CFSE. Then 4-fold volume of ice-cold medium was added for 5 min, and the cells were washed with PBS two times. The stained cells were allowed to grow at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Then the cells were suspended in PBS, and the intensity of CFSE staining was quantified by flow cytometry (excitation: 492 nm; emission: 517 nm). CFSE is a fluorescent cell staining dye. CFSE is retained within cells and covalently couples to intracellular molecules. So the dye can be used to monitor cell proliferation due to the progressive halving of CFSE fluorescence within daughter cells following each cell division. The cell proliferation is negatively correlated to the intensity of fluorescence.

2.8. Data analysis

Data are presented as mean±SEM. Significance was determined by using Student t test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

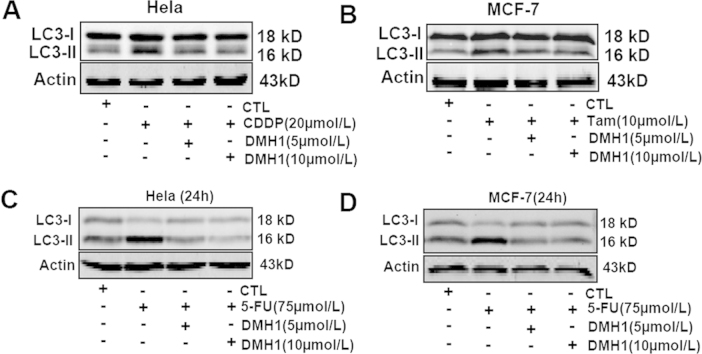

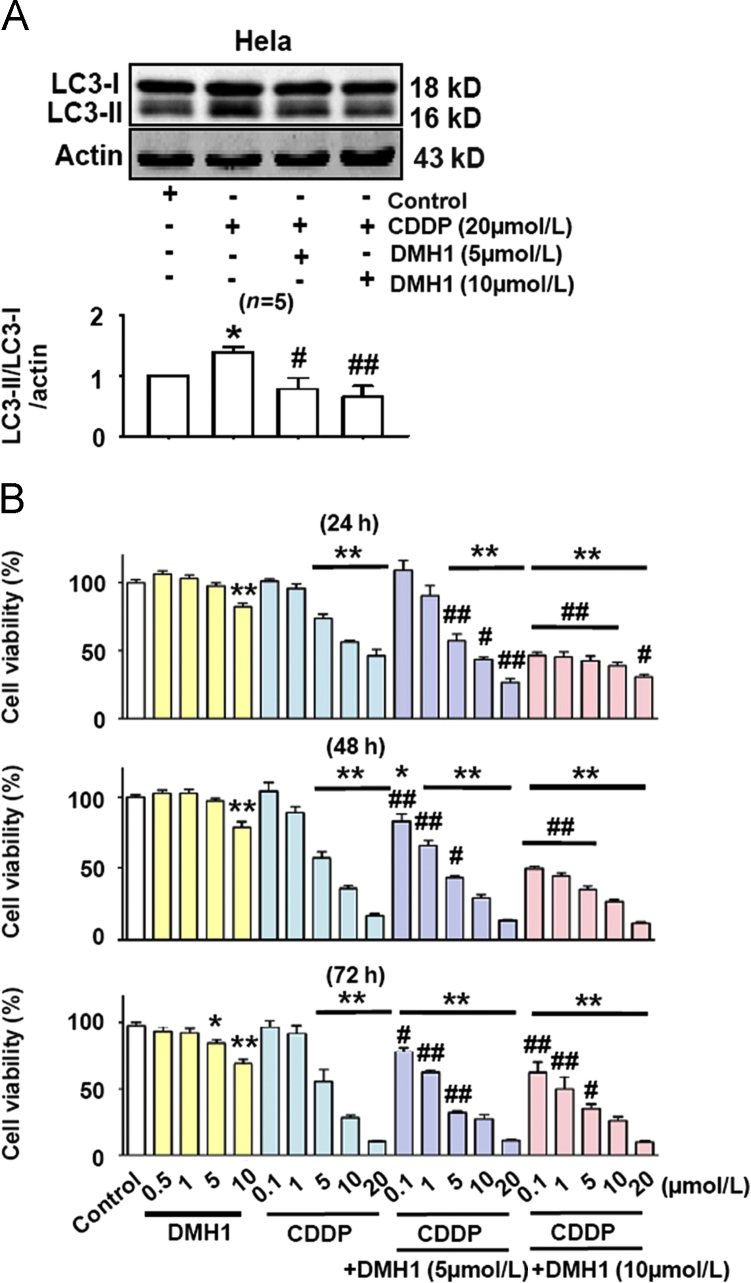

3.1. DMH1 inhibits CDDP-induced autophagy in HeLa cells and enhances the ability of CDDP to reduce HeLa cell viability

CDDP is widely used to treat solid tumors in clinical therapy, although drug resistance can severely limit the effects of many chemotherapy drugs11. It was reported that CDDP activated autophagy in an osteosarcoma cell line and that inhibition of autophagy enhanced CDDP-induced cell apoptosis12. Here, we first examined whether CDDP could induce autophagy in HeLa cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, CDDP (20 μmol/L) treatment for 24 h strongly activated autophagy response in HeLa cells and pretreatment with DMH1 (5 μmol/L and 10 μmol/L) completely inhibited this effect. Hao et al.9 reported that DMH1 suppressed lung cancer cells growth and invasion. Similarly, we found that DMH1 significantly reduced the viability of HeLa cells (Fig. 1B). Since DMH1 inhibited CDDP-induced autophagy in HeLa cells, we hypothesized that DMH1 could possibly increase the anti-tumor effects of CDDP. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 1B, CDDP treatment dose-dependently reduced HeLa cell viability, and DMH1 treatment potentiated CDDP-induced inhibition of HeLa cell viability.

Figure 1.

DMH1 potentiates the anticancer activity of CDDP for HeLa cells. (A) DMH1 inhibited CDDP-induced autophagy in HeLa cells. Cells were treated with DMH1 or CDDP for 24 h. *P<0.05 vs. Control; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. CDDP. (B) Co-application of DMH1 enhanced the ability of CDDP to reduce HeLa cell viability. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. counterpart CDDP dose. n=10.

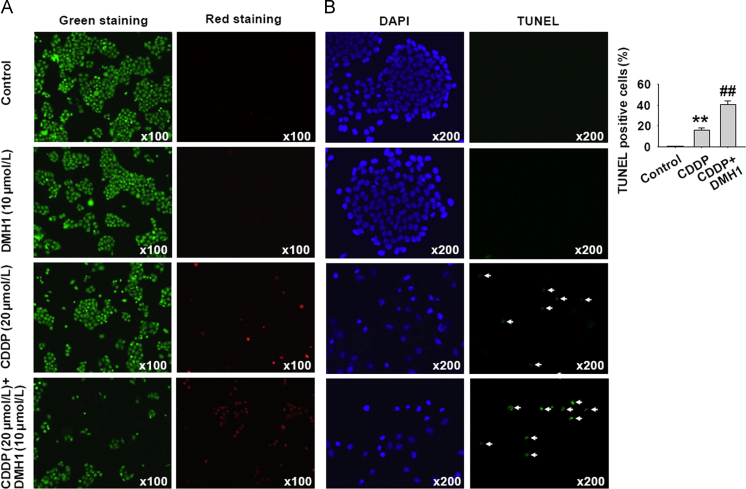

3.2. DMH1 increases CDDP-induced apoptotic cell death in HeLa cells

Since DMH1 treatment potentiated CDDP-induced inhibition of HeLa cell viability, we investigated whether apoptosis was involved in the effects produced by DMH1 and CDDP. Firstly, we examined the effects of DMH1 and CDDP on cell death by using live and dead staining in HeLa cells. The calcein AM stained the live cells green, and ethidium homodimer-1 stained the dead cells red. As shown in Fig. 2A, DMH1 treatment had no effect on cell death, but CDDP significantly decreased the number of green cells and increased the number of red cells, indicating that CDDP induced cell death. The CDDP-induced cell death was increased when DMH1 was further co-applied. As shown in Fig. 2B, DMH1 did not induce apoptosis in HeLa cells, but significantly enhanced the ability of CDDP to induce cell apoptosis.

Figure 2.

DMH1 enhances the apoptotic induction effects of CDDP on HeLa cells after 24 h treatment. (A) DMH1 enhanced CDDP-induced cell death after 24 h treatment. The live cells were stained with calcein AM in green, and the dead cells were stained with ethidium homodimer-1 in red. (B) TUNEL staining showed that DMH1 enhanced CDDP-induced cell apoptosis after 24 h treatment. The analyzed cell number was 6219 in control group, 3468 in CDDP group and 3615 in CDDP plus DMH1 group. **P<0.01 vs. Control; ##P<0.01 vs. CDDP.

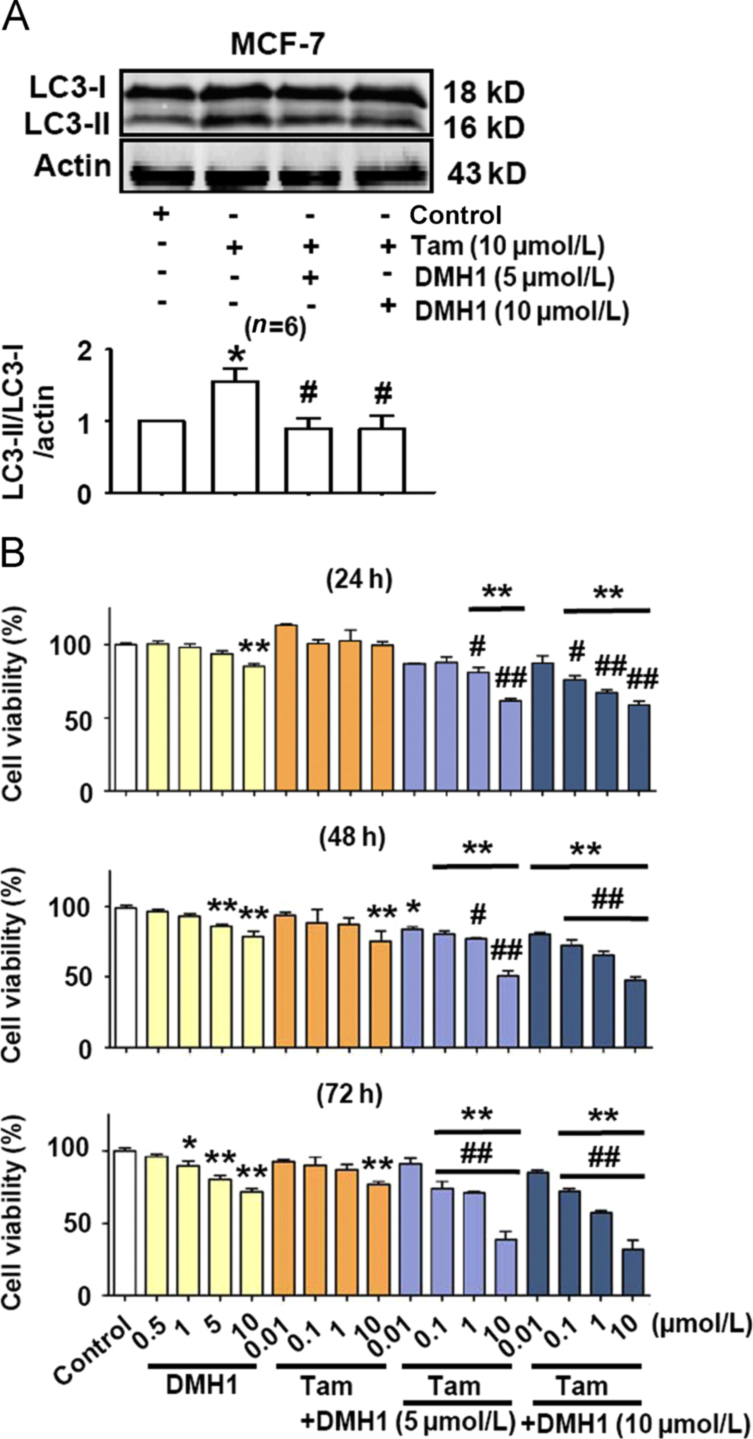

3.3. DMH1 inhibits tamoxifen-induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells and enhances the ability of tamoxifen to reduce MCF-7 cell viability

Tamoxifen is effective in treating breast cancer by binding to estrogen receptor13. We further examined whether the effects of DMH1 as measured above also recurred in tamoxifen-treated MCF-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, DMH1 (5 μmol/L and 10 μmol/L) treatment for 24 h completely abolished the tamoxifen-induced increase of autophagy responses in MCF-7 cells. Both DMH1 and tamoxifen reduced MCF-7 cell viability respectively, and co-treatment of DMH1 and tamoxifen exerted an additional inhibitory effect on cell viability in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

DMH1 potentiates the anticancer activity of tamoxifen for MCF-7 cells. (A) DMH1 inhibited tamoxifen-induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with DMH1 or tamoxifen for 24 h. *P< 0.05 vs. Control; #P<0.05 vs. tamoxifen. (B) Co-application of DMH1 enhanced the ability of tamoxifen to reduce MCF-7 cell viability. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. counterpart tamoxifen dose. n=10.

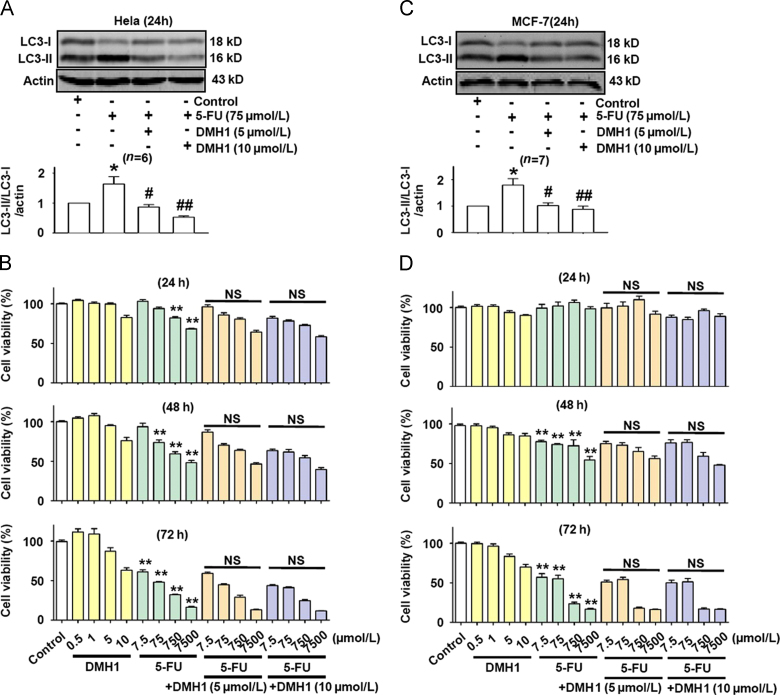

3.4. DMH1 inhibited 5-FU-induced autophagy in both MCF-7 and HeLa cells but did not affect the inhibitory effects of 5-FU on MCF-7 and HeLa cell viability

Next, we used 5-FU, which is generally sensitive to gastrointestinal tumors, but not sensitive to breast and cervical tumors, to test whether DMH1 enhanced the inhibitory effect of 5-FU on MCF-7 and HeLa cells. Similar to the effects of tamoxifen and CDDP, 5-FU also induced autophagy responses in MCF-7 and HeLa cells, and the induced autophagy was inhibited by DMH1 treatment (Fig. 4A). However, DMH1 (5 μmol/L and 10 μmol/L) did not enhance the inhibitory effects of 5-FU on MCF-7 and HeLa cell viability after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

DMH1 inhibited 5-FU-induced autophagy in MCF-7 and HeLa cells but did not affect the inhibitory effects of 5-FU on MCF-7 and HeLa cell viability after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment. (A) DMH1 inhibited 5-FU-induced autophagy in HeLa cells. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. 5-FU. (B) DMH1(5 and 10 μmol/L) did not affect the inhibitory effects of 5-FU on HeLa cell viability after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment. **P<0.01 vs. Control. n=10. (C) DMH1 inhibited 5-FU-induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs. 5-FU. (D) DMH1 (5 and 10 μmol/L) did not affect the inhibitory effects of 5-FU on MCF-7 cell viability after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment. **P<0.01 vs. Control. NS, no significance vs. counterpart drug dose. n=10.

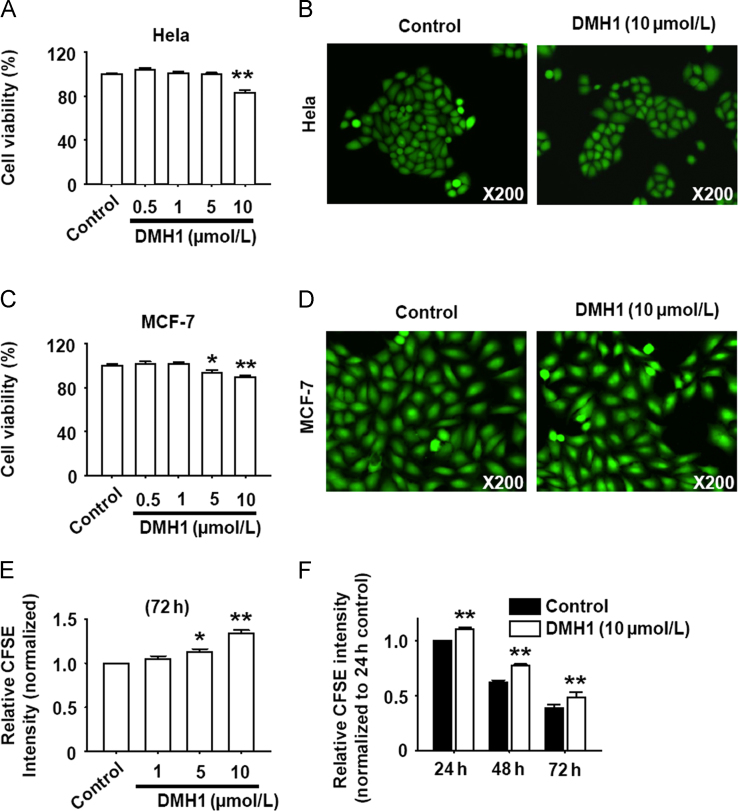

3.5. DMH1 inhibits HeLa and MCF-7 cell proliferation

As shown in Figs. 5A–D, DMH1 reduced MCF-7 and HeLa cell viability but did not induce cell death. To test the hypothesis that the reduced cell viability might be due to inhibition of cell proliferation, we further examined the effects of DMH1 on cell proliferation with HeLa cells as example. Results showed that DMH1 dose- and time-dependently inhibited HeLa cell proliferation (Fig. 5E and F). Since it was demonstrated that DMH1 had no effect on the basal autophagy level10, the DMH1-induced inhibition of cell proliferation was not related to the DMH1-induced autophagy inhibition.

Figure 5.

DMH1 inhibits HeLa and MCF-7 cell proliferation. (A) DMH1 reduced HeLa cells viability. **P<0.01 vs. Control. n=10. (B) Representative photos of live and dead staining by which the live cells fluoresce green and death cells fluoresce red. (C) DMH1 reduced MCF-7 cells viability. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control. n=10. (D) Representative photos of live- and dead staining by which the live cells fluoresce green and death cells fluoresce red. (E) DMH1 dose-dependently inhibited HeLa cell proliferation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control. n=4. (F) The time course of DMH1-inhibited cell proliferation in HeLa cells. **P<0.01 vs. Control. n=4.

4. Discussion

Our previous study evidences that DMH1 is a novel autophagy inhibitor which inhibits starvation, AICAR (aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide)- and rapamycin-induced autophagy by activating AKT/mTOR pathway10, but whether DMH1 can also inhibit the autophagy triggered by chemotherapeutic drugs and/or enhance the antitumor activity of chemotherapeutic drugs remained unclear. In the present study, we found for the first time that DMH1 inhibits CDDP, tamoxifen and 5-FU induced autophagy responses and potentiates the antitumor effects of CDDP and tamoxifen in HeLa and MCF-7 cells.

Autophagy plays a complicated role in tumorigenesis and treatment responsiveness. On the one hand, induction of autophagy seems to be beneficial for cancer prevention and induction of autophagic cell death is as a therapeutic strategy. On the other hand, inhibiting autophagy can enhance the efficacy of anticancer therapies. Several studies have demonstrated that inhibition of autophagy sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy and gene therapy14, 15. However, many factors involved in the relationship between autophagy and chemosensitivity were still undetermined. Since DMH1 inhibited autophagy, we examined whether it influenced the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs by using different cell lines and different drugs. In the present study, we used MCF-7 and HeLa cancer cells which were sensitive to tamoxifen and CDDP respectively. Tamoxifen and CDDP induced autophagy in MCF-7 and HeLa cells and inhibited the cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Co-application of DMH1 significantly potentiated the anticancer activity of tamoxifen and CDDP in MCF-7 and HeLa cells. Furthermore, we treated HeLa and MCF-7 cells with 5-FU which was not sensitive to these two cell lines. We found that 5-FU induced autophagy in HeLa and MCF-7 cells and dose- and time-dependently inhibited the cell viability, although DMH1 showed no enhancing effect for 5-FU in these cells. Abedin et al.16 found that autophagy inhibition enhanced apoptosis in camptothecin-treated primary and noninvasive breast cell lines, but not metastatic breast cell lines. These results, together with our present data, implied that the relationship between autophagy and chemosensitivity was complicated and it could not be simply concluded that autophagy inhibition enhanced chemosensitivity under all conditions. Our previous work showed that the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine induced cell death but its interaction with chemotherapeutic drugs was independent of autophagy17. Therefore, the role of autophagy inhibition in chemotherapy needs further elucidating.

Besides the inhibitory effect on autophagy, DMH1 also has other actions, so we could not exclude the possibility that DMH1 sensitized cancer cells to chemotherapy through targeting other signal pathways. It was reported that BMPs were aberrantly expressed in many types of carcinoma cells including prostate, lung, breast, gastric and ovarian18, 19, 20, 21, overexpression of BMP-2 in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines significantly enhanced tumor growth in a mouse model of lung cancer22. Conversely, the BMP inhibitor noggin and DMH1 dramatically reduced lung tumor growth in subcutaneous xenograft mouse models9, 23, suggesting that DMH1 increased the efficacy of anti-tumor drugs which might be due to its role in blocking BMP signal. On the other hand, we found DMH1 inhibited intracellular ATP levels in L6 cells24. Targeting cancer cell mitochondria to deplete ATP was an effective therapeutic approach25. ATP depletion stimulated by norcantharidin induced prostate cancer cells apoptosis and inhibited the proliferation-relate genes PCNA, Ki67 and p27 expression in gallbladder carcinoma cells26, 27. So the effect of DMH1 to decrease cellular ATP levels might also be involved.

In conclusion, DMH1 inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced autophagy response. The enhancement of chemotherapeutic drug efficacy by DMH1 is dependent on the cell sensitivity to the drugs, not the autophagy inhibition action.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81373406).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Shintani T., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306(5698):990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Codogno P., Meijer A.J. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12 Suppl 2:S1509–S1518. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debnath J., Baehrecke E.H., Kroemer G. Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy. 2005;1:66–74. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J., Hou N., Faried A., Tsutsumi S., Takeuchi T., Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA enhances the effect of 5-FU-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:761–771. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishikawa T., Tsuno N.H., Okaji Y., Shuno Y., Sasaki K., Hongo K. Inhibition of autophagy potentiates sulforaphane-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:592–602. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0696-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y.J., Chi C.W., Su W.C., Huang H.L. Lapatinib induces autophagic cell death and inhibits growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:4845–4854. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hao J., Ho J.N., Lewis J.A., Karim K.A., Daniels R.N., Gentry P.R. In vivo structure-activity relationship study of dorsomorphin analogues identifies selective VEGF and BMP inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:245–253. doi: 10.1021/cb9002865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neely M.D., Litt M.J., Tidball A.M., Li G.G., Aboud A.A., Hopkins C.R. DMH1, a highly selective small molecule BMP inhibitor promotes neurogenesis of hiPSCs: comparison of PAX6 and SOX1 expression during neural induction. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:482–491. doi: 10.1021/cn300029t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao J., Lee R., Chang A., Fan J., Labib C., Parsa C. DMH1, a small molecule inhibitor of BMP type i receptors, suppresses growth and invasion of lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng Y., Sun B., Guo W.T., Liu X., Wang Y.C., Xie X. 4-[6-(4-isopropoxyphenyl)pyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl] quinoline is a novel inhibitor of autophagy. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:4970–4980. doi: 10.1111/bph.12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woźniak K., Błasiak J. Recognition and repair of DNA-cisplatin adducts. Acta Biochim Pol. 2002;49:583–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Z., Tao L., Shen C., Liu B., Yang Z., Tao H. Silencing of Barkor/ATG14 sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to cisplatininduced apoptosis. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:271–276. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazarali S.A., Narod S.A. Tamoxifen for women at high risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2014;6:29–36. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S43763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang P.M., Liu Y.L., Lin Y.C., Shun C.T., Wu M.S., Chen C.C. Inhibition of autophagy enhances anticancer effects of atorvastatin in digestive malignancies. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7699–7709. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S., Rehman S.K., Zhang W., Wen A., Yao L., Zhang J. Autophagy is a therapeutic target in anticancer drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abedin M.J., Wang D., McDonnell M.A., Lehmann U., Kelekar A. Autophagy delays apoptotic death in breast cancer cells following DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:500–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng Y., Sun B., Guo W.T., Zhang Y.H., Liu X., Xing Y. 3-Methyladenine induces cell death and its interaction with chemotherapeutic drugs is independent of autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsuno Y., Hanyu A., Kanda H., Ishikawa Y., Akiyama F., Iwase T. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling enhances invasion and bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through Smad pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:6322–6333. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye L., Lewis-Russell J.M., Kyanaston H.G., Jiang W.G. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:1129–1147. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alarmo E.L., Kallioniemi A. Bone morphogenetic proteins in breast cancer: dual role in tumourigenesis? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R123–R139. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thawani J.P., Wang A.C., Than K.D., Lin C.Y., La Marca F., Park P. Bone morphogenetic proteins and cancer: review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:233–246. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000363722.42097.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langenfeld E.M., Kong Y., Langenfeld J. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 stimulation of tumor growth involves the activation of Smad-1/5. Oncogene. 2006;25:685–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feeley B.T., Liu N.Q., Conduah A.H., Krenek L., Roth K., Dougall W.C. Mixed metastatic lung cancer lesions in bone are inhibited by noggin overexpression and Rank: Fc administration. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1571–1580. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie X., Xu X.M., Li N., Zhang Y.H., Zhao Y., Ma C.Y. DMH1 increases glucose metabolism through activating Akt in L6 rat skeletal muscle cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen S., Zhu D., Huang P. Targeting cancer cell mitochondria as a therapeutic approach. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:53–67. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen B., He P.J., Shao C.L. Norcantharidin induced DU145 cell apoptosis through ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and energy depletion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan Y.Z., Fu J.Y., Zhao Z.M., Chen C.Q. Influence of norcantharidin on proliferation, proliferation-related gene proteins proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Ki-67 of human gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3:603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]