Significance

Many cancers are driven by aberrant activation of members of the EGF receptor (EGFR) family including ErbB2 (HER2) and ErbB3 (HER3). EGFR and ErbB3 exist in equilibrium between a tethered, inactive conformation and an extended, active state poised toward formation of homo- or heterodimers with other members of the EGFR family, normally in a ligand-dependent manner. In cancers, these receptors are activated by aberrant ligand stimulation or via a ligand-independent mechanism. Here we describe the crystal structure of the extracellular domain of ErbB3 in complex with a therapeutic antibody, revealing a unique allosteric mechanism for inhibition of cancer cells by locking ErbB3 in the autoinhibited configuration. This mechanism offers new therapeutic opportunities for treating cancers driven by aberrant EGFR, ErbB2, or ErbB3 activation.

Keywords: cancer, surface receptor, cell signaling, therapeutic antibodies, crystal structure

Abstract

ErbB3 (HER3) is a member of the EGF receptor (EGFR) family of receptor tyrosine kinases, which, unlike the other three family members, contains a pseudo kinase in place of a tyrosine kinase domain. In cancer, ErbB3 activation is driven by a ligand-dependent mechanism through the formation of heterodimers with EGFR, ErbB2, or ErbB4 or via a ligand-independent process through heterodimerization with ErbB2 overexpressed in breast tumors or other cancers. Here we describe the crystal structure of the Fab fragment of an antagonistic monoclonal antibody KTN3379, currently in clinical development in human cancer patients, in complex with the ErbB3 extracellular domain. The structure reveals a unique allosteric mechanism for inhibition of ligand-dependent or ligand-independent ErbB3-driven cancers by binding to an epitope that locks ErbB3 in an inactive conformation. Given the similarities in the mechanism of ErbB receptor family activation, these findings could facilitate structure-based design of antibodies that inhibit EGFR and ErbB4 by an allosteric mechanism.

The EGF receptor (EGFR)/ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) participates in a multitude of roles during embryonic development and in adult homeostasis. In healthy tissues, ErbB signal transduction is initiated through ligand-induced homo- or heterodimerization of receptor extracellular domains leading to the stimulation of tyrosine kinase activity and autophosphorylation of several tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain followed by recruitment and activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways (1). In contrast, unregulated ErbB signaling through activating mutations, receptor overexpression, or aberrant autocrine ligand signaling loops can lead to cellular transformation and tumorigenesis (2). Thus, members of the ErbB receptor family (in particular EGFR and ErbB2) have become well-validated targets for the development of anticancer therapeutics, resulting in a number of Food and Drug Administration-approved and marketed monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors used for treatment of different cancers (3).

The activity of ErbB3 (also designated HER3) is normally regulated by the neuregulin (NRG) family of growth factors (4), but, unlike other members of the family, ErbB3 functions as an obligate heterodimer with other ErbB receptors because its cytoplasmic domain contains a pseudo kinase in place of a tyrosine kinase domain (5, 6). ErbB3 therefore takes part in heterodimer formation through ligand binding, whereas its coreceptor (most often ErbB2) provides enzymatic activity to phosphorylate multiple tyrosine residues located primarily in the ErbB3 C-terminal tail. The role of ErbB3 in cancer has been fully appreciated only within the last decade and has prompted the development of several monoclonal antibodies geared at inhibiting its action in solid tumors. ErbB3 phosphorylation and subsequent signaling have been associated with driving tumor progression in several solid tumor types such as breast, lung, head-and-neck, gastric, and thyroid cancers (7–9). Moreover, it was proposed that tumor cells use AKT activation through ErbB3 upregulation as a compensatory mechanism for therapeutic inhibition of EGFR and ErbB2 and for targeted inhibition of the MEK and PI3K pathways (10).

By analogy with EGFR and ErbB4, ErbB3 is thought to exist in an equilibrium between an autoinhibited (tethered) state, which is stabilized by interdomain contacts between extracellular domains 2 and 4, and an extended conformation in which a dimerization arm in domain 2 is exposed (1, 11, 12). Ligand binding to ErbB3 cross-links domains 1 and 3 intramolecularly and stabilizes the extended form of ErbB3, inducing conformational changes that foster ErbB3 heterodimerization with ErbB2 or other ligand-bound ErbB receptors (13). In cancer cells, tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB3 through autocrine or paracrine NRG loops promotes tumor cell growth and survival by robustly stimulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Ligand-dependent ErbB3 activation can be inhibited by several therapeutic antibodies that function mostly by directly blocking ligand-receptor interactions, resulting in significant antitumor activity in preclinical models of human cancer (14–16). By contrast, the requirement for NRG is bypassed in tumors that highly overexpress ErbB2 (such as in subpopulations of ErbB2-amplified breast, ovarian, gastric, and esophageal cancers) (17, 18). Through mass action, overexpression of ErbB2 can force heterodimerization with ErbB3 in a ligand-independent mechanism to provide survival cues to cancer cells. Importantly, because many ErbB3 antibodies currently in clinical development interfere with ligand binding, their ability to inhibit cancers driven by ligand-independent mechanism will be limited.

Here we report the crystal structure of the extracellular domain of ErbB3 bound to the Fab fragment of KTN3379, a fully human anti-ErbB3 antibody currently in phase 1 clinical development for cancer patients that robustly blocks both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent modes of ErbB3 signaling in models of human cancer. KTN3379 binds with high affinity to a unique epitope in the boundary between domains 2 and 3 in ErbB3 and prevents a conformational rearrangement to the extended form of the receptor that is required for both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent ErbB3 activation. Our data uncover a novel allosteric mechanism for ErbB3 inhibition with antitumor activity in distinct cancer settings and further suggest that exploiting a similar epitope in EGFR and ErbB4 could yield potent and novel mono- or bispecific therapeutic antibodies.

Results and Discussion

KTN3379 Binds to ErbB3 with High Affinity and Inhibits Both Ligand-Dependent and Ligand-Independent ErbB3 Signaling.

KTN3379 was identified as a strong ErbB3-binding Fab from a phage-library screen, followed by affinity maturation to bind ErbB3 with very high affinity. Upon conversion to a fully human IgG1, the CH2 domain in the heavy chain also was modified to improve serum half-life by increasing its affinity to the neonatal Fc receptor (19). A key criterion in selecting KTN3379 was its ability to inhibit both NRG-dependent and NRG-independent ErbB3 activation in cell-based assays.

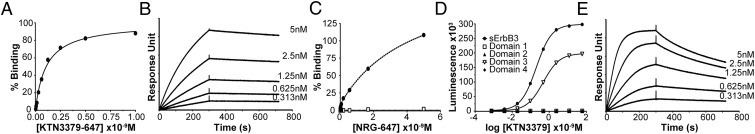

We first analyzed the binding of KTN3379 to T47D breast cancer cells, which express moderate levels of ErbB3 on their cell surface. The experiment presented in Fig. 1A depicts a titration of fluorescently labeled KTN3379 (KTN3379-647), revealing binding to T47D breast cancer cells with an apparent affinity of 98 pM. Similar binding affinity was obtained from surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements in which the kinetics and binding of purified soluble ErbB3 extracellular domain (sErbB3) to the Fab fragment of KTN3379 (Fab3379) molecules that were immobilized on a sensor chip surface were analyzed. The SPR experiments revealed a Kd of 166 pM and an extremely slow dissociation rate of 1.56 × 10−4⋅s−1 (Fig. 1B). As determined by binding experiments using SPR measurements, the similarity in the binding affinities of intact bivalent KTN3379 to cells expressing ErbB3 and of monovalent Fab3379 to cells expressing sErbB3 demonstrate that KTN3379 binding to ErbB3 is driven by strong binding affinity rather than by an avidity effect mediated by KTN3379 bivalency.

Fig. 1.

KTN3379 binds to ErbB3 with high affinity and prevents NRG binding to ErbB3. (A) Binding of fluorescently conjugated KTN3379 (KTN3379-647) to ErbB3-expressing T47D breast cancer cells. The fluorescent intensity of cells labeled with KTN3379-647 was quantitated by flow cytometry analysis. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. (B) SPR sensorgram of sErbB3 to Fab3379 immobilized on the BIAcore sensor chip surface. (C) KTN3379 prevents binding of NRG to Ba/F3 cells expressing ErbB3. ErbB3-expressing Ba/F3 cells were incubated with (open squares) and without (filled circles) 10 nM KTN3379, followed by titration with fluorescently conjugated NRG (NRG-647). The fluorescent intensity of cells labeled with NRG-647 was quantitated by flow cytometry analysis. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. (D) KTN3379 binds to sErbB3 (filled circles) and to isolated domain 3 (open triangles). KTN3379 was titrated on ELISA plates coated with sErbB3 or each purified domain 1, 2, 3, or 4 and subsequently was incubated with an HRP-conjugated anti-human antibody. (E) SPR sensorgram of isolated domain 3 of ErbB3 to Fab3379 immobilized on a BIAcore sensor chip surface. Isolated domain 3 binds Fab3379 with an approximately twofold weaker affinity and accelerated kinetics relative to sErbB3.

We next examined whether the binding of KTN3379 to cells harboring ErbB3 on their surface affects NRG binding to the ErbB3 receptor. Ba/F3 cells expressing ErbB3 were treated with 10 nM KTN3379 or buffer alone for 1 h at 4 °C followed by treatment with increasing concentrations of fluorescently labeled NRG (NRG-647) for 2 h at 4 °C. The experiment presented in Fig. 1C shows that the high-affinity NRG binding mediated by simultaneous NRG binding to domains 1 and 3 of the extended ectodomain configuration is blocked completely by KTN3379 binding to the ErbB3 receptor expressed on the cell surface of Ba/F3 cells. The experiment presented in Fig. 1D shows that KTN3379 binds primarily to an epitope located in domain 3 of ErbB3. In this experiment, KTN3379 was titrated on ELISA plates coated with sErbB3 or coated with each ErbB3 subdomain produced in Sf9 cells, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-human antibodies. Indeed, the SPR experiment presented in Fig. 1E shows that purified domain 3 binds to Fab3379 immobilized on a BIAcore sensor chip surface. However, a comparison of the SPR analyses reveals that isolated domain 3 binds to Fab3379 with approximately twofold reduced Kd of 377 pM that most likely is caused by a 10-fold accelerated dissociation rate (1.74 × 10−3⋅s−1), suggesting that KTN3379 may interact with additional ErbB3 region(s).

We next examined the ability of KTN3379 to affect ErbB3-dependent cellular responses in cancer cells. As shown in Fig. S1, titration of KTN3379 in MDA-MB-175-vii cells, which contain high levels of activated ErbB3 by virtue of an autocrine NRG loop, inhibits ErbB3 and downstream AKT phosphorylation (Fig. S1A) and demonstrates robust antiproliferative activity with IC50 values in the single-nanomolar range (Fig. S1B). The same titration in BT-474 cells, which express very high levels of ErbB2 but no measurable NRG, also led to a reduction in ErbB3 tyrosine phosphorylation and phospho-AKT levels (Fig. S1C) and antiproliferative activity with IC50 values in the mid-picomolar range (Fig. S1D). Similar results were obtained in other cell lines in which constitutive ErbB3 activity is driven through either NRG or high ErbB2 overexpression. Interestingly, the measured KTN3379 IC50 values in ligand-dependent and ligand-independent models differ by one to two orders of magnitude. In ligand-dependent models, KTN3379 competes with continuously secreted NRG for ErbB3, yielding IC50 values in the high picomolar to low nanomolar range. By contrast, the IC50 values in ligand-independent models are markedly lower (and are similar to its measured affinity), likely reflecting the largely unimpeded binding of KTN3379 to ErbB3.

Fig. S1.

KTN3379 inhibits ligand-dependent and ligand-independent ErbB3 activities in cancer cells. (A) KTN3379 inhibits ErbB3 (open circles) and AKT phosphorylation (filled triangles) in the ligand-dependent cell line MDA-MB-175 with low-nanomolar IC50 values. (B) Similarly, KTN3379 demonstrates antiproliferative activity on MDA-MB-175 cells with similar IC50 values. In this cell line, ErbB3 is activated by a NRG autocrine loop, and cell growth is largely dependent on ErbB3 activity. (C) KTN3379 inhibits ErbB3 (open circles) and AKT phosphorylation (filled triangles) in the ligand-independent cell line BT-474 with mid-picomolar IC50 values. (D) KTN3379 also demonstrates antiproliferative activity on BT-474 cells with a similar potency. This cell line expresses very high levels of ErbB2 and no detectable NRG. (E and F) KTN3379 exhibits significant single-agent antitumor activity in mouse xenograft models of human cancer. Twice weekly dosing of KTN3379 at 20 mg/kg significantly delays tumor growth of the ligand-dependent model of head-and-neck cancer Cal27 (E) and the ligand-independent model of gastric cancer NCI-N87 (F).

We further evaluated the antitumor activity of KTN3379 in mouse xenograft models of human cancer in which tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB3 is NRG-dependent (Cal27) or NRG-independent and ErbB2-amplified (NCI-N87). Biweekly dosing of KTN3379 at 20 mg/kg for 4 wk was well tolerated and demonstrated significant single-agent antitumor activity in both the Cal27 and NCI-N87 models (Fig. S1 E and F). Similar results were observed in other tumor models. Thus, KTN3379 antagonizes ErbB3-dependent tumor growth independent of the manner by which it is activated. The inhibitory potency of KTN3379 can be explained by its high binding affinity for ErbB3.

It is noteworthy that KTN3379 treatment of ErbB2-amplified cancer cells resulted in incomplete inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB3, AKT, and cell proliferation. Similarly, treatments with other antibodies against ErbB3 or anti-ErbB2 (such as trastuzumab or pertuzumab) also yield incomplete inhibition of signaling (20, 21). ErbB2-mediated signaling in this context could result from the formation of several homo- and heterodimer species nucleated by ErbB2, and therefore treatment with a single antibody alone is insufficient to inhibit signaling fully. Indeed, the combination of KTN3379 with trastuzumab resulted in enhanced activity in ErbB2-amplified cancer models relative to either antibody alone. Therefore, KTN3379 is well suited for clinical use in combination treatment with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, therapeutic antibodies that target ErbB2 and EGFR, or other targeted agents, such as the V600E BRAF mutation in melanoma, which upon inhibition relapse through feedback reactivation of ErbB3 (22).

Crystal Structure of sErbB3 in Complex with Fab3379.

To understand the mechanism of dual inhibition by KTN3379 at the molecular level, the crystal structure of sErbB3 in complex with Fab3379 was determined at 3.20-Å resolution (Table S1). The crystals were grown from 18% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium citrate dibasic, and 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using the structure of autoinhibited conformation of ErbB3 (15) and the structure of a Fab fragment that has a high sequence identity with Fab3379 as search models. The protein complex was crystallized in space group P1 with four complex molecules per asymmetric unit. The fully refined structure revealed that Fab3379 binds to a unique epitope in domains 2 and 3 of sErbB3 and locks the receptor in its autoinhibited state (Fig. 2A). Least-square superposition of sErbB3 in our structure with the structure of the previously determined autoinhibited sErbB3 extracellular domain (23) shows an α-carbon rmsd of 1.41 Å, confirming that Fab3379-bound sErbB3 is indeed in its inactive conformation (Fig. S2).

Table S1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for sErbB3–Fab3379

| Data collection | APS 24-ID-E |

| Space group | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c, Å | 84.378, 127.141, 138.078 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 87.10, 85.54, 89.92 |

| Wavelength, Å | 0.97918 |

| Resolution, Å* | 69.39–3.20 (3.314–3.20) |

| Observed reflections* | 180,887 (18,118) |

| Unique reflections* | 92,683 (9,252) |

| Redundancy* | 1.9 (2.0) |

| Completeness, %* | 98.31 (98.25) |

| < I/σ>* | 7.45 (2.62) |

| Rmerge*,† | 0.1015 (0.3211) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution, Å | 69.39–3.20 |

| Rwork/Rfree‡ | 0.2523/0.2777 |

| Number of residues | |

| Protein | 3,646 |

| N-acetylglucosamine | 11 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 67.80 |

| N-acetylglucosamine | 52.30 |

| Rmsd | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.002 |

| Bond angle (o) | 0.57 |

Highest resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

Rmerge = ∑ | Ii - <I> | /∑ Ii.

Rwork = ∑ | Fo – Fc | /∑ Fo. Rfree is the cross-validation R factor for the test set of reflections (5% of the total) omitted in model refinement.

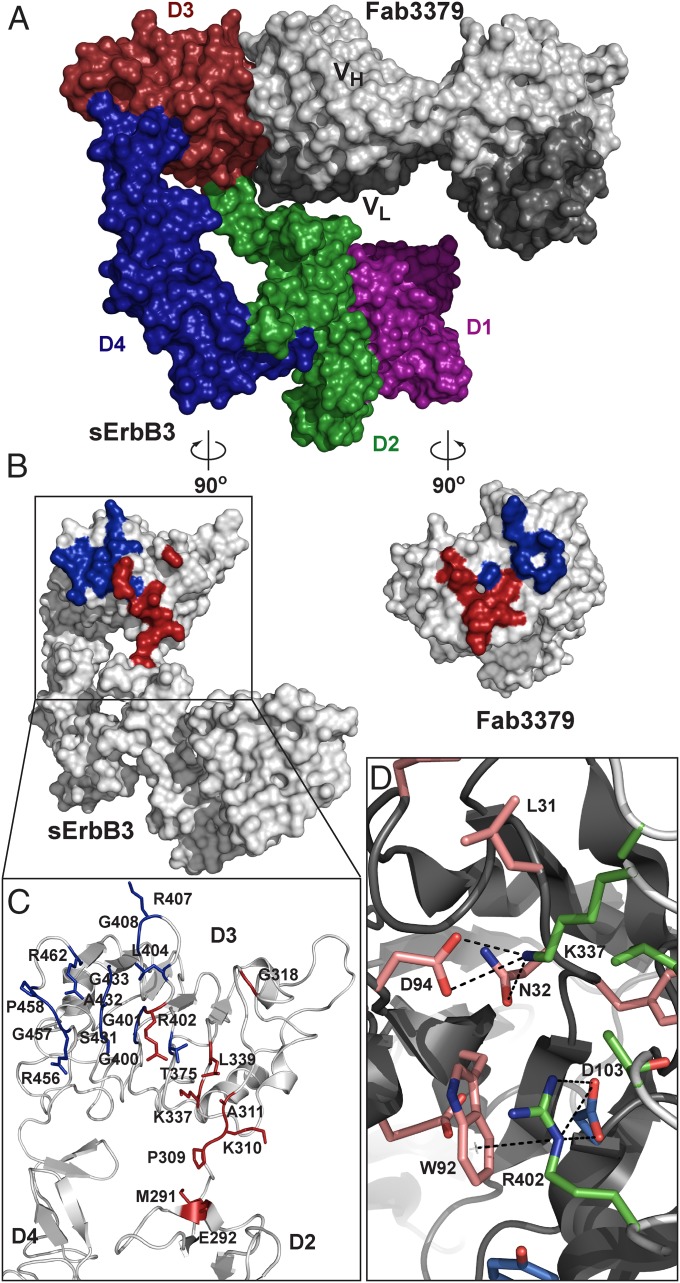

Fig. 2.

Crystal structure of the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex. (A) Surface representation model of the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex shows that Fab3379 (gray) binds primarily to the side of domain 3 (red) in sErbB3, to domain 2 (green), and to the hinge region between domain 2 and domain 3 and stabilizes the inactive tethered state of sErbB3. The heavy chain region is shown in light gray, and the light chain region is shown in dark gray. (B) “Open-book” representation of the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex shown in A. The Fab3379-binding epitope in sErbB3 is highlighted in blue (heavy chain epitope) and red (light chain epitope). Likewise, the sErbB3-binding paratope in Fab3379 is highlighted in blue (heavy chain) and red (light chain). (C) Detailed view of region in sErbB3 that interacts with Fab3379. The heavy chain binds exclusively to domain 3, and the light chain contacts part of domain 3, the C terminus of domain 2, and the hinge region between both domains. (D) Representative interactions between Fab3379 and domain 3 of sErbB3 in the region centered on Arg402 in sErbB3. Sidechain atoms in stick representation from the epitope in sErbB3, the heavy chain paratope in Fab3379, and the light chain paratope in Fab3379 were colored in light green, light blue, and bright red, respectively. Both Arg402 and Lys337 in sErbB3 make multiple contacts with Fab3379, contributing significantly to the overall stability of receptor antibody complex.

Fig. S2.

Overlay of Fab3379-bound sErbB3 with a tethered conformation of sErbB3. Structure-based comparison between Fab3379-bound sErbB3 (dark blue) and a previously determined sErbB3 structure (orange, PDB ID code: 1M6B) in its native tethered conformation. The overall Cα rmsd is 1.41 Å. The Fab3379 molecule is omitted for clarity.

The structure shows that KTN3379 binds predominantly to an epitope in domain 3 of sErbB3, a finding that is in agreement with binding data to each purified ErbB3 subdomain (Fig. 1 D and E). The heavy chain variable domain (VH) of the antibody binds exclusively to the side of domain 3, and the light chain variable domain (VL) exploits part of domain 3 and wedges itself into the hinge boundary between domains 2 and 3 (Figs. 2 A and B and 3A). The combined sum of all interactions buries a total surface area of 900 Å2 in sErbB3, where the VH chain contributes 470 Å2 and the VL chain contributes 430 Å2. The nearly equal contributions of VH and VL to the overall binding to sErbB3 can be seen clearly in Fig. 2 B and C. The overall shape complementarity parameter for the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex is 0.65, within the values typically observed for antibody–antigen interfaces (24).

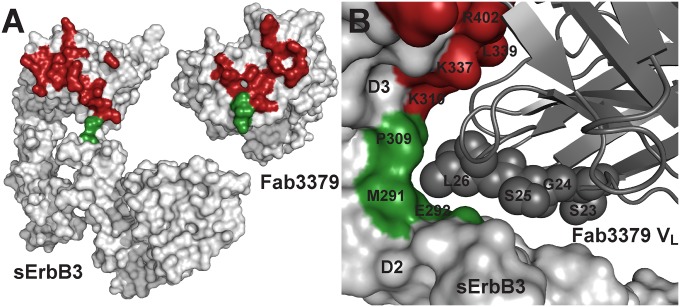

Fig. 3.

Contacts between Fab3379 and the hinge region connecting domains 2 and 3 of ErbB3 are critical for the mechanism of inhibition. (A) Contact regions between Fab3379 and domain 3 and domain 2 of sErbB3 are colored in red and green, respectively. Also highlighted are the contacts by domain 3 (red) and domain 2 (green) on the surface of Fab3379. sErbB3 and Fab3379 are shown in same orientation as in Fig. 2B. (B) Detailed view focusing on the interaction between the Fab3379 VL (gray) and the hinge region between domain 2 (red) and domain 3 (green). CDR1 residues in Fab3379 VL wedge the antibody into the hinge region, preventing the conformational rearrangement required for transition from the autoinhibited configuration of sErbB3 to its extended activated form. Listed residues in Fab3379 VL were modified to strengthen the interaction with domain 2 of ErbB3 further, lowering the off-rate of the reaction (Fig. S5).

All the contacts observed between Fab3379 and sErbB3 are mediated by the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of the antibody molecule. In some cases, several residues in Fab3379 coordinate binding to a single side chain from sErbB3. Of particular importance is Arg402, which forms a partially buried salt bridge with VH Asp103 as well as cation-π interaction with the indole ring of VL Trp92 (Fig. 2D) and thus likely contributes a substantial amount of binding energy to the overall stability of the complex. In addition, Lys337 forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone carboxyl oxygen of VL Leu31 as well as with the side chains of VL Asn32 and VL Asp94 (Fig. 2D). Conversely, there also are amino acid residues in Fab3379 that simultaneously contact multiple amino acids in sErbB3. For example, VH Tyr33 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone oxygen of Gly400 as well as hydrophobic interactions with Gly401, Arg402, Ser431, and Arg432. The amino acid residues that make intermolecular contacts and their interactions are summarized in Fig. S3.

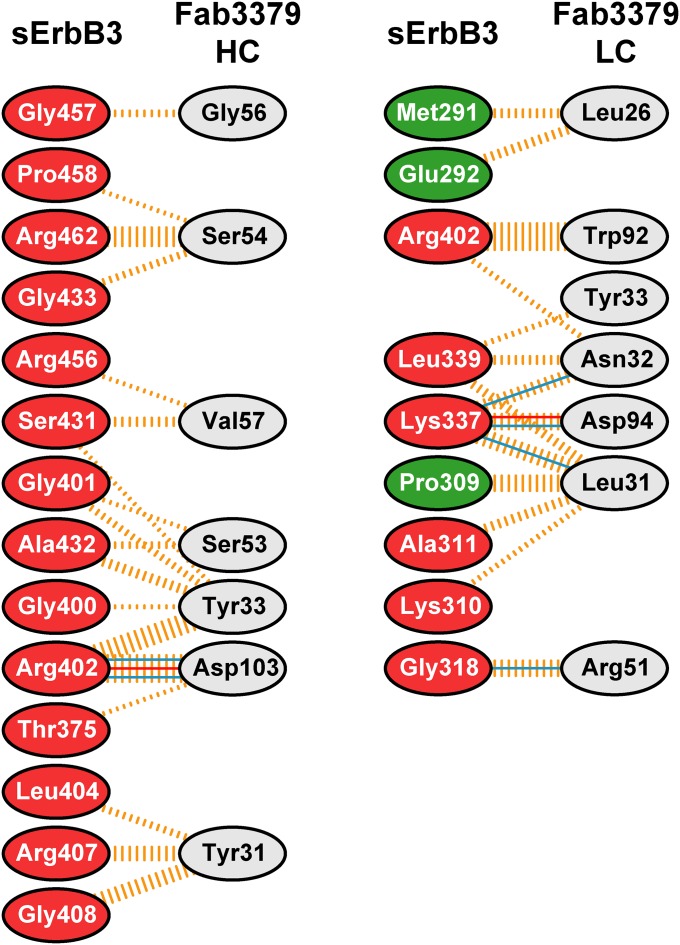

Fig. S3.

Summary of interactions between sErbB3 and Fab3379 identified from the crystal structure. The diagram showing the amino acid residues that make intermolecular contact was generated by PDBsum (36). The residues in sErbB3 are colored according to the domains: green for domain 2, and red for domain 3. The interactions are represented by lines connecting the residues: solid blue lines for hydrogen bonds; solid red lines for salt bridges; and dashed orange lines for nonbonded contacts. The thickness of the lines indicates the number of contacts.

Fab3379 VL Binding to Domain 2 Locks sErbB3 in an Inactive Conformation.

Inspection of the ErbB3 surface that is occupied by KTN3379 shows that the antibody interacts primarily with domain 3 and that fewer interactions also take place with domain 2 and with the hinge connecting domain 3 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3). The VL region of Fab3379 makes a set of contacts with domain 2 and the hinge region between domains 2 and 3 that are critical for the inhibitory activity of KTN3379. A set of residues from VL CDR1 effectively complements the curvature of the hinge region by enforcing a diverse set of contacts. In particular, VL Leu26 and Leu31 form hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions with hinge region residues Met291 and Pro309, and the interactions are strengthened further by the aliphatic part of Glu292 in domain 2 as well as Ala311 and the aliphatic part of Lys337 in domain 3 (Fig. 3B). This complementary interface stabilizes the inactive conformation of ErbB3 by restricting the receptor motions essential for the formation of the ErbB3 extended conformation (Movies S1 and S2). Moreover, these interactions have important kinetic consequences for the stability of the complex. Our SPR studies demonstrate that the affinity with which Fab3379 binds to the isolated domain 3 of ErbB3 is approximately twofold lower than the affinity with which it binds to the entire ErbB3 extracellular domain (Fig. 1 A and E). Kinetic analysis of SPR data shows that the association and dissociation rates for isolated domain 3 are increased compared with the rates for the intact extracellular domain, arguing that the contacts between Fab3379 and domain 2 of ErbB3 contribute significantly to both kinetic processes. Notably, the Kd for sErbB3 is approximately 10 times slower than that for isolated domain 3, indicating that interactions of Fab3379 with domain 2 enhance the Kd mainly by decreasing the dissociation rate. The interactions with domain 2 also cause a decrease in the association rate with sErbB3, suggesting that ErbB3, which exists in equilibrium between different configurations, adopts a more restricted configuration(s) upon antibody binding and that the light chain CDR1 of Fab3379 is critical for the stability of the final complex.

The importance of the domain 2–3 hinge region in ErbB receptor activation has been elucidated previously from crystallographic and solution studies of active and inactive ErbB receptors (13). The hinge region, which is flanked by two rigid disulfide bridges, imposes an important thermodynamic barrier for the transition between the tethered and extended forms of EGFR. Comparison of the crystal structures of inactive EGFR and of ligand-bound EGFR reveal that although the relationship between domains 3 and 4 remains relatively unchanged, the domain 2–3 hinge region acts as a pivot point upon which the receptor rotates and adopts an active conformation. Thus, a high-affinity antibody that binds to this region, such as KTN3379, would be predicted to inhibit EGFR or ErbB4 activation potently by stabilizing the tethered autoinhibited receptor form.

Allosteric Inhibition of NRG Binding to ErbB3 by KTN3379.

One important question arising from our structure is whether KTN3379 blocks NRG binding to ErbB3, because ErbB3 activation in many tumors depends on the formation of an NRG–ErbB3 complex. Most reported therapeutic antibodies against EGFR and ErbB3 function mainly by competing directly with ligand–receptor interactions (15, 16, 25). Because the structure of NRG in complex with sErbB3 has not been solved yet, the structure of domain 3 of sErbB3 was superimposed on the corresponding structure of soluble ErbB4 extracellular domain (sErbB4) in complex with NRG (26) to demonstrate that the ligand-binding footprint of the two receptors is nearly identical. This result is not surprising, because NRG is a high-affinity ligand for both ErbB3 and ErbB4. This analysis shows that the ligand-binding site, as revealed by overlaying the KTN3379-bound sErbB3 structure with NRG-bound sErbB4, is clearly distinct from the antibody-binding site on domain 3 of sErbB3 (Fig. 4A).

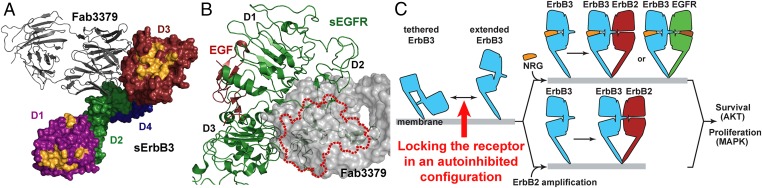

Fig. 4.

KTN3379 blocks NRG binding to ErbB3 through an allosteric mechanism. (A) The sErbB3–Fab3379 complex in which NRG-binding sites in domain 1 and 3 of sErbB3 are highlighted in yellow. The NRG-binding sites were identified by superposition of the NRG-bound form of ErbB4 onto the structure of the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex. The model reveals that KTN3379 and NRG bind to mutually exclusive sites in ErbB3. (B) KTN3379 binding is incompatible with the extended form of ErbB3 and other family members. Superimposing the extended conformation of sEGFR (PDB ID code: 1IVO) on the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex centered on domain 3 reveals that KTN3379 would clash significantly with domain 2 in the extended form; the area in the extended conformation of sEGFR that would clash with Fab3379 is marked by the red dotted line. Superimposing the extended conformations of other ErbB receptors, sErbB2 and NRG-bound sErbB4, also demonstrates that KTN3379 would clash with the extended forms of all ErbB receptors (Fig. S4). (C) Mechanism of ErbB3 inhibition by KTN3379. KTN3379 binds and blocks ErbB3 in the first step of ErbB3 activation to lock the ErbB3 extracellular domain in the tethered configuration (marked with a red arrow). Similar to EGFR and ErbB4, ErbB3 exists in equilibrium between a predominantly autoinhibited form and an extended form. The tethered form of ErbB3 (light blue) is stabilized primarily by contacts between domains 2 and 4. During normal physiological stimulation and in several cancers (Upper), NRG binding induces and stabilizes the formation of a dimerization-competent form of the receptor by binding to domains 1 and 3, enabling heterodimerization with ErbB2 (red), ligand-bound EGFR (light green), or ErbB4. In tumors in which ErbB2 is highly overexpressed (Lower), ErbB3 can be activated in the absence of NRG through forced dimerization with ErbB2. In either scenario, ErbB3 activation strongly elicits proliferative and antiapoptotic signals. The dual mechanism of action of KTN3379 therefore hinges on its ability to prevent ErbB3 from sampling a dimerization-competent conformation.

The crystal structure shows that Fab3379 and NRG bind to separate regions in ErbB3, but KTN3379 potently blocks NRG binding to ErbB3 expressed on the surface of cells. Indeed, preincubation of Ba/F3 cells coexpressing ErbB3 and ErbB2 with 10 nM of KTN3379 fully blocks the binding of NRG-647 to ErbB3 (Fig. 1C). These data support the notion that high-affinity binding of NRG to ErbB3 requires that both ligand-binding sites in domains 1 and 3 are allowed to come into close proximity, similar to EGF binding to EGFR and NRG binding to ErbB4. Therefore, KTN3379 allosterically blocks NRG binding to ErbB3 by preventing domains 1 and 3 from simultaneously binding the ligand, revealing a mechanism of action that is distinct from that of other ErbB antagonists. SI Discussion contains a brief discussion of a previously published antibody (20) that blocks ErbB3 activation through an alternate allosteric mechanism.

A Structural Explanation for the Dual Mechanism of Action of KTN3379.

The key distinguishing feature of KTN3379 is its ability to inhibit the first step in a chain of events that leads to both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent ErbB3 activation. Superimposing the activated forms of soluble EGFR extracellular domain (sEGFR) (27), sErbB4 (26), or sErbB2 (28) on domain 3 of Fab3379-bound sErbB3 shows that Fab3379 clashes dramatically with a significant portion of domain 2 (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4). The same clash is predicted to occur with the extended form of ErbB3, based on previous small-angle X-ray scattering studies, which demonstrated that NRG binding to ErbB3 stabilizes the extended form of the receptor, resembling that of EGF-bound sEGFR and sErbB2 (13). This finding confirms that Fab3379 must restrain any intramolecular domain rearrangements when it is bound to ErbB3, particularly given the extremely slow dissociation rate of the complex. Because both NRG-dependent and NRG-independent ErbB3 signaling require that ErbB3 adopt an extended state to form stable heterodimers, blocking domain rearrangement by KTN3379 would effectively prevent the downstream signaling via both pathways. Recently published molecular dynamics studies (29) predict that an NRG-driven ErbB3/ErbB2 heterodimer would form an asymmetric complex resembling a dimer of a ligand-bound form of Drosophila EGFR (30, 31), and a symmetric NRG-independent heterodimer can stably exist also, particularly under extremely high local concentrations of ErbB2. KTN3379 tightly blocks the very first step in ErbB3 activation and restricts any downstream molecular events, no matter whether the activating source is NRG or high levels of ErbB2 (Fig. 4C).

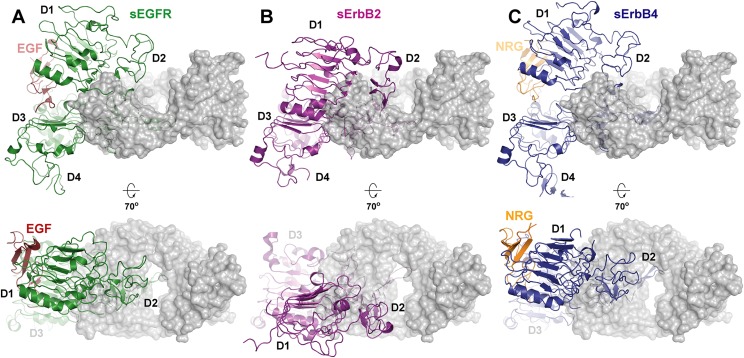

Fig. S4.

KTN3379 binding is incompatible with the extended and active form of ErbB receptors. Superimposing available structures of extended ErbB receptors with the sErbB3–Fab3379 complex centered on domain 3 reveals that KTN3379 would clash significantly with domain 2 of all receptors. Ligand-bound sEGFR (PDB ID code: 1IVO) (A), sErbB2 (PDB ID code: 2A91) (B), and NRG-bound sErbB4 (PDB ID code: 3U7U) (C) demonstrate that Fab3379 (gray) clashes with the extended forms of ErbB receptors.

Improvement of Binding Kinetics Through Structure-Based Modification of Fab3379.

The crystal structure of this complex provides a template that can be used to improve the binding affinity and potency of KTN3379. Thorough inspection of all interactions and complementarity in the complex interface suggests potential mutations that may further improve the stability of the complex. In particular, the interface between VL CDR1 of Fab3379 and the C terminus of domain 2 in ErbB3 (Fig. 3B) was subjected to structure-based modifications that may provide new interactions without disrupting previously existing ones. Structure-guided introduction of novel interactions in this interface is expected to reduce the flexibility of the domain 2–3 hinge region further and to lower the dissociation rate, thereby improving the overall affinity. Mutation of Fab3379 VL Ser23 to Arg (S23R) and Ser25 to His (S25H) decreased the complex dissociation rate from 1.1 × 10−4⋅s−1 to 8.2 × 10−5⋅s−1 and 5.5 × 10−5⋅s−1, respectively (Fig. S5). These data further emphasize the importance of domain 2 contacts in mediating complex stability and suggest that structure-guided mutations can be used to develop more potent or versatile variants of KTN3379.

Fig. S5.

Improvement of KTN3379 binding kinetics by structure-guided modifications. SPR sensorgrams of sErbB3 to Fab3379 and its VL variants, S23R and S25H, immobilized on a BIAcore sensor chip. A single-cycle kinetics method was used with an extended dissociation time (4,800 s) to compare the off-rates. Measurements were done in triplicate.

Therapeutic Targeting of Other ErbB Receptors by Exploiting the Same Mechanism of Action.

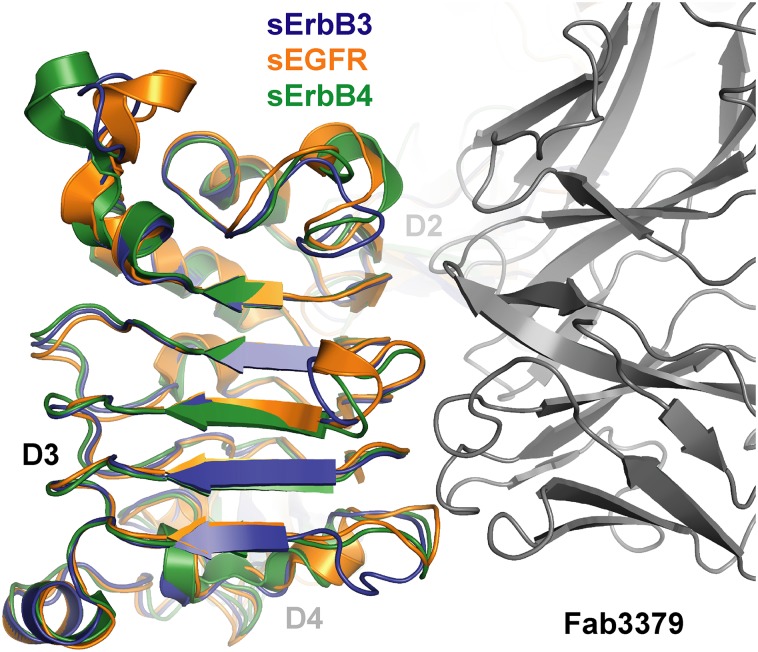

Our data present the possibility of targeting the domain 2–3 hinge region in other receptors, in particular EGFR and ErbB4, with novel and potent therapeutic antibodies with an activity profile similar to KTN3379. Unlike ErbB2, which exists predominantly in an extended state, activation of EGFR and ErbB4 requires intramolecular motions similar to those described for ErbB3 (13). Empirical approaches such as phage display can be used to develop antibodies that exploit the same region in EGFR and ErbB4. Overlays of Fab3379-bound sErbB3 with the inactive forms of sEGFR and sErbB4 reveal that the overall architecture of the Fab3379-binding epitope is well conserved in all three family members (Fig. S6). Thus, using our structure as a platform, structure-based antibody engineering could be used to develop antibodies that may cross-react with other ErbB receptors while maintaining the same mode of action. Fig. S6 shows that Fab3379 can be accommodated quite well into the same region of EGFR, ErbB3, and ErbB4, particularly into the flexible domain 2–3 hinge. Only a few minor clashes, largely arising from VH contacts with domain 3, may obstruct binding of KTN3379 directly. Although KTN3379 does not bind to the rest of the ErbB family, conservative modifications in the VH CDR2 predicted to alleviate clashing with a loop in domain 3 along with interface-optimizing mutations may suffice to convert KTN3379 into an EGFR- or ErbB4-inhibitory antibody. These engineered antibodies could provide a significant clinical advantage in oncological indications where several ErbB receptors contribute to promote tumor growth, without the need to create bispecific antibodies with two different Fab arms.

Fig. S6.

EGFR and ErbB4 share a similar topology with ErbB3 in the KTN3379-binding epitope. An overlay of the autoinhibited structures of EGFR (orange; PDB ID code: 1YY9), ErbB4 (green; PDB ID code: 2AHX), and the sErbB3 (dark blue)–Fab3379 (gray) complex centered on domain 3 highlights the overall architectural conservation of the KTN3379-binding epitope among autoinhibited ErbB receptors. Minor clashes arise from differences in a flexible loop within domain 3. By contrast, this epitope is not present in ErbB2 because it exists in a constitutively extended state. The same mechanism of inhibition therefore could be exploited in EGFR and ErbB4 with KTN3379-like antibodies.

SI Discussion

Most anti-ErbB3 antibodies described in the literature were identified by screening for antibodies that block NRG binding, and therefore these antibodies bind to the NRG-binding sites located in either domain 1 or domain 3 of ErbB3 (14–16). On the other hand, Garner et al. (20) described an anti-ErbB3 antibody designated “LJM716” that binds to an epitope located in domain 2 and domain 4 of ErbB3. Structural analysis of LJM716 Fab in complex with the ErbB3 extracellular domain showed that LJM716 binds simultaneously to an epitope located within domain 2 and domain 4 in the autoinhibited configuration of ErbB3. Because LJM716 locks ErbB3 in the inactive configuration, it is expected that LJM716 will block both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent ErbB3 cellular responses. However, binding experiments to isolated sErbB3 or to ErbB3 expressed on the cell surface of cultured cells demonstrated that LJM716 does not prevent NRG binding to ErbB3 (20). Although experiments presented in the text demonstrate that LJM716 binds to human or rodent ErbB3 with subnanomolar dissociation constants (20), it is not clear whether the inability of LJM716 to interfere with NRG binding is caused by rapid LJM716 dissociation from the tethered inactive ErbB3 state. In this scenario, high-affinity NRG binding would overcome the inhibitory constraint imposed by LJM716 on the tethered inactive ErbB3 state by shifting the equilibrium toward the extended active conformation.

Conclusions

ErbB3 has been recognized as an important player in solid tumor biology. Here we report that the inhibitory ErbB3 antibody KTN3379 blocks both NRG-dependent and -independent mechanisms of activation by binding to a novel epitope. KTN3379 forms a complex with ErbB3 with picomolar monovalent affinity and interferes with the first step of its activation, which is required for both modes of signaling. The antibody also precludes ligand–receptor interactions through an indirect mechanism, by interfering with high-affinity cross-linking of NRG by domains 1 and 3. The high affinity measured for the complex is largely the result of an extremely slow off-rate, a highly desirable property in therapeutic antibodies. The unusual stability of the complex results in large measure from the interaction and stabilization of KTN3379 with domain 2, as demonstrated by the accelerated binding kinetics of Fab3379 to domain 3 in isolation. Interestingly, our data suggest that KTN3379 binding to cell-surface ErbB3 is likely to be largely monovalent and not driven by avidity, because the apparent affinity for ErbB3-expressing cells did not increase measurably relative to the monovalent affinity measured by SPR. One potential implication of this finding is that KTN3379 could be well suited as one arm of an antibody that engages multiple targets, because the potential loss of avidity (at least to ErbB3) would not be an issue. We further show that the dissociation rate of Fab3379 can be decreased even further through structure-guided mutations, predicted to forge new contacts with domain 2, indicating that further improvements can be made.

Our structure describes a novel and versatile mode of inhibiting ErbB3, a concept that can be expanded to other ErbB receptors such as EGFR and ErbB4 (but not ErbB2). Although the epitope itself is not fully conserved in these receptors, the architecture of this region and their overall mechanism of activation are well conserved. Therefore it is possible to engineer novel inhibitors using structure-based design that simultaneously target more than one ErbB receptor, either by generating antibodies de novo or by modifying KTN3379 using our structural information. These antibodies would function via the same mechanism of action as KTN3379 and might have favorable dissociation kinetics as described above.

Overall, the improved binding kinetics and versatile mechanisms of action that can be achieved by targeting a critical allosteric site essential for receptor activation can provide an advantage over therapies that compete directly with ligand-receptor interactions.

Materials and Methods

The protein complex was concentrated to 8 mg/mL and screened for crystallization with commercially available kits (Hampton Research) and the mosquito automated liquid handler (TTP Labtech) using a hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method. When the equal volumes of the protein solution and reservoir containing 18% PEG 3350, 0.2 M di-ammonium citrate hexahydrate, and 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate were mixed and equilibrated over the reservoir, crystals with the shape of a thin hexagonal prism grew within 1 wk. The size of crystals increased dramatically when the ratio between the protein solution and the reservoir was changed to 2:1. The crystals were cryoprotected by slow transfer to artificial mother liquor supplemented with 30% PEG 400. The diffraction qualities of the crystals were improved significantly by extensive trials of dehydration (32). The crystals were dehydrated by stepwise transfer to a mother liquor containing 25% PEG 3350, 0.2 M di-ammonium citrate hexahydrate, and 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate and were equilibrated over the same mother liquor for 5 d before cryoprotection. Cryopreserved crystals then were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

A 3.20-Å diffraction native dataset was collected at Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) beamline 24-ID-E and processed with XDS (33). The structure was solved by molecular replacement (PHASER) using tethered conformation of sErbB3 (PDB ID code: 4LEO, chain C) and a structure of Fab that has high sequence identities with Fab3379 (PDB ID code: 3H42, chains H and L). Fab3379 in complex with sErbB3 crystallized in space group P1, with unit-cell parameters of a = 84.378 Å, b = 127.141 Å, c = 138.078 Å, and α = 87.10, β = 85.54, γ = 89.92, containing four complex molecules per asymmetric unit (Table S1). Iterative rounds of refinement were done using PHENIX (34) with manual inspection using COOT (35).

All procedures and protocols for in vivo studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of WuXi AppTec. Full details about the experiments describing the properties of KTN3379 and expression and purification procedures for proteins used in the study are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

In Vitro Phosphorylation and Proliferation Assays.

Phosphorylation assays.

Cell lines were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection and grown as recommended. Twenty thousand cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and grown overnight in 10% serum. KTN3379 was titrated on cells and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Washed cells were lysed on ice-cold lysis buffer [25 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate] with protease inhibitors (Roche). Lysates were applied to ELISA plates coated with anti-ErbB3 (R&D) or anti-AKT (Millipore) capture antibodies. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, ErbB3-treated plates were incubated with an HRP-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (R&D) for 1 h followed by washing. AKT-coated plates were incubated with a biotinylated secondary anti–phospho-AKT (Cell Signaling) antibody for 2 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with Streptavidin-HRP (Thermo). Plates were developed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo) and read using a BioTek plate reader. Normalized chemiluminescent data were plotted as a function of the log-transformed antibody concentration, and the data were fit to a four-parameter nonlinear regression algorithm using GraphPad Prism, from which IC50 values were derived.

Proliferation assays.

Cells were seeded at a density of 5,000–10,000 cells per well in black 96-well proliferation plates (Corning) and incubated overnight in full serum. KTN3379 was titrated on cells and incubated for 5–7 d in serum-reduced conditions at 37 °C. The plates were treated with CellTiter-Glo (Promega), which provides an indirect measurement of cell proliferation. Data were fit and analyzed as described above.

ELISA Binding Assay.

sErbB3 and each of the four domains that constitute the full ErbB3 extracellular domain were engineered to contain a His-tag at their C termini and were expressed in baculovirus-infected Sf9 insect cells. Conditioned media containing each protein were purified over Ni-NTA resin (GE Healthcare) and eluted with an imidazole step gradient in PBS (Gibco). Fractions containing the protein of interest were purified further by size exclusion chromatography using a Sephadex-200 column preequilibrated with PBS. Each purified protein was coated on ELISA high-bind plates (Greiner Bio-One) and blocked with 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton-X100 (TBST). KTN3379 was titrated and incubated on plates containing each immobilized protein in the presence of 1% BSA in TBST. Plates were washed with TBST, incubated with an HRP-linked secondary goat anti-human antibody, washed again, and developed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo). Luminescence data were transformed and fit as described above using an agonist algorithm rather than an inhibitory one.

Flow Cytometry Binding Assays.

KTN3379 and NRG1-β1 (R&D) were fluorescently labeled with Alexa-647 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, yielding KTN3379-647 and NRG-647. The molar loading ratio of dye to protein was maintained under 2:1 to prevent protein denaturation and nonspecific binding.

Apparent Kd determination.

T47D breast cancer cells were dissociated from a T150 flask, washed, and blocked with ice-cold FACS buffer (PBS + 2% newborn calf serum). KTN3379-647 was titrated into the cells and incubated for at least 2 h on ice. Cells were washed twice in FACS buffer and resuspended in FACS buffer containing 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; Life Technologies) to allow gating of live cells. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was measured by flow cytometry, using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Nonspecific binding was determined by incubating the KTN3379-647 titration with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled KTN3379. Specific binding data were plotted as a function of antibody concentration using GraphPad Prism and were fit to a single binding site isotherm, from which the apparent Kd was derived.

NRG blocking assay.

NRG-647 was titrated and incubated on Ba/F3 cells engineered to coexpress ErbB2 and ErbB3, which previously had been washed and blocked as described above. The treatment was done on cells alone or on cells preincubated with 10 nM KTN3379 for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were washed, incubated with 7-AAD, and subjected to flow cytometry. Background-subtracted MFI values were plotted as a function of NRG concentration, and the data were best fit to a two-site binding model using GraphPad prism.

Xenograft Studies.

For in vivo studies, 10 × 106 Cal27 or NCI-N87 cells mixed with Matrigel (1:1) were implanted s.c. into nu/nu athymic mice. Animals were randomized once tumors reached 150 mm3 in size and were segregated into different cohorts. KTN3379 or a control IgG1 antibody was dosed i.p. at 20 mg/kg twice a week for 4 wk. Experiments were performed by Wuxi Apptec.

Protein Expression and Purification for Crystallization.

Human ErbB3 amino acid 1-640 with a C-terminal hexa-histidine tag was cloned into pFastbac1, and the recombinant bacmid was generated after the sequence was confirmed. High-titer virus generated by the bacmid then was used to infect Sf9 cells grown in Sf-900 II serum-free medium (Life Technologies). At 120 h post infection, the medium was collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g and filtered. The medium was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen; 2 mL/L of medium) overnight at 4 °C. The resin was washed extensively with PBS containing 5 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted from the beads with the buffer containing 20 mM Tris 8.0 and 300 mM imidazole, and the eluted fractions were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0). The protein was deglycosylated using endoglycosidase F1 and subjected to anion exchange chromatography (MonoQ HR; GE Healthcare). The typical yield was 2 mg pure protein per liter of culture.

The DNA sequence for Fab3379 was codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli and was synthesized (Blue Heron Biotechnology, Inc.). The sequences for heavy chain and light chain were cloned into a vector pET26b (Novagen), each containing the pelB signal peptide for periplasmic secretion. The vector was transformed into BL21(DE3) cells, and a single colony was grown in LB medium and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 20 °C for 16 h. The cell pellet was lysed with a French press at 15,000 psi, and the supernatant, after centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 30 min, was incubated with protein A Sepharose 4B (Life Technologies) for 2 h at 4 °C. The resin was washed extensively with PBS, and the protein was eluted with 100 mM glycine⋅HCl (pH 3.5) and neutralized immediately with 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0). The protein then was subjected to cation exchange chromatography (MonoS HR; GE Healthcare), and the fractions that contained equimolar amounts of heavy chain and light chain were combined and concentrated. Purified sErbB3 and Fab3379 were mixed and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C before being subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl.

SPR Measurements.

SPR experiments were performed using a BIAcore T100 instrument (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C (Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University). Fab3379 and its VL CDR1 variants, S23R and S25H, were prepared for SPR measurements as described above and immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip using a standard amine-coupling method. Three surfaces of Fab3379 having different concentrations were created, with the optimal coupling condition of 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5). A series of twofold dilution of sErbB3 or isolated domain 3 was injected onto the surface sequentially and in random. The surface was regenerated using 3 M NaCl and 3 M MgCl2. For the VL variants, single-cycle kinetics analysis, incorporating a dissociation period of 4800 s, was applied to compare extremely slow dissociation rates among the Fab molecules. A series of solutions of sErbB3 with five twofold dilution concentrations was flowed over the sensor chip with immobilized Fabs. The binding kinetics was evaluated using BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare), and all sensorgrams were fitted to a 1:1 binding model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the J.S. laboratory for excellent scientific and technical input; Titus Boggon and the staff of the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team at the Advanced Photon Source for assistance with data collection; Ewa Folta-Stogniew for assistance with the SPR experiments; and Theresa M. LaVallee for critical reading of and comments on our manuscript. The T100 BIAcore instrumentation was supported by NIH Award S10RR026992-0110.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.S. is a founder and consultant of Kolltan. G.F.L., J.S.L., E.J.N., D.A., and Y.H. are Kolltan employees.

Data deposition: Crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5CUS).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518361112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141(7):1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arteaga CL, Engelman JA. ERBB receptors: From oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arteaga CL. ErbB-targeted therapeutic approaches in human cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284(1):122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falls DL. Neuregulins: Functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284(1):14–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi F, Telesco SE, Liu Y, Radhakrishnan R, Lemmon MA. ErbB3/HER3 intracellular domain is competent to bind ATP and catalyze autophosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(17):7692–7697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002753107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jura N, Shan Y, Cao X, Shaw DE, Kuriyan J. Structural analysis of the catalytically inactive kinase domain of the human EGF receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):21608–21613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912101106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funayama T, et al. Overexpression of c-erbB-3 in various stages of human squamous cell carcinomas. Oncology. 1998;55(2):161–167. doi: 10.1159/000011851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee-Hoeflich ST, et al. A central role for HER3 in HER2-amplified breast cancer: Implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68(14):5878–5887. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ocana A, et al. HER3 overexpression and survival in solid tumors: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(4):266–273. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrabarty A, Sánchez V, Kuba MG, Rinehart C, Arteaga CL. Feedback upregulation of HER3 (ErbB3) expression and activity attenuates antitumor effect of PI3K inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(8):2718–2723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess AW, et al. An open-and-shut case? Recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;12(3):541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson JP, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization and activation require ligand-induced conformational changes in the dimer interface. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(17):7734–7742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7734-7742.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson JP, Bu Z, Lemmon MA. Ligand-induced structural transitions in ErbB receptor extracellular domains. Structure. 2007;15(8):942–954. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoeberl B, et al. An ErbB3 antibody, MM-121, is active in cancers with ligand-dependent activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(6):2485–2494. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirschberger C, et al. RG7116, a therapeutic antibody that binds the inactive HER3 receptor and is optimized for immune effector activation. Cancer Res. 2013;73(16):5183–5194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer G, et al. A two-in-one antibody against HER3 and EGFR has superior inhibitory activity compared with monospecific antibodies. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(4):472–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Fiore PP, et al. erbB-2 is a potent oncogene when overexpressed in NIH/3T3 cells. Science. 1987;237(4811):178–182. doi: 10.1126/science.2885917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slamon DJ, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244(4905):707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dall’Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) J Biol Chem. 2006;281(33):23514–23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner AP, et al. An antibody that locks HER3 in the inactive conformation inhibits tumor growth driven by HER2 or neuregulin. Cancer Res. 2013;73(19):6024–6035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sergina NV, et al. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature. 2007;445(7126):437–441. doi: 10.1038/nature05474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abel EV, et al. Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(5):2155–2168. doi: 10.1172/JCI65780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho HS, Leahy DJ. Structure of the extracellular region of HER3 reveals an interdomain tether. Science. 2002;297(5585):1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1074611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape complementarity at protein/protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234(4):946–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P, et al. A single ligand is sufficient to activate EGFR dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(27):10861–10866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201114109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu C, et al. Structural evidence for loose linkage between ligand binding and kinase activation in the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(22):5432–5443. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00742-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bostrom J, et al. Variants of the antibody herceptin that interact with HER2 and VEGF at the antigen binding site. Science. 2009;323(5921):1610–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1165480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arkhipov A, Shan Y, Kim ET, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Her2 activation mechanism reflects evolutionary preservation of asymmetric ectodomain dimers in the human EGFR family. eLife. 2013;2:e00708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarado D, Klein DE, Lemmon MA. ErbB2 resembles an autoinhibited invertebrate epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature. 2009;461(7261):287–291. doi: 10.1038/nature08297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarado D, Klein DE, Lemmon MA. Structural basis for negative cooperativity in growth factor binding to an EGF receptor. Cell. 2010;142(4):568–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heras B, Martin JL. Post-crystallization treatments for improving diffraction quality of protein crystals. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61(Pt 9):1173–1180. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905019451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laskowski RA. Enhancing the functional annotation of PDB structures in PDBsum using key figures extracted from the literature. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(14):1824–1827. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.