Significance

The passive movement of ions across biological membranes is controlled by channels. How these membrane proteins are activated and become permeable to ions, a process with high biomedical and biotechnological impact, has been the subject of numerous structural, functional, and computational studies. We have investigated the light-gated cation channel channelrhodopsin-2 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, widely used in optogenetics, by combining time-resolved infrared spectroscopy and electrophysiology. The temporal evolution of the hydration of transmembrane α-helices, identified by spectroscopic markers, matches the kinetics of ion conductance, as monitored by electrophysiology. Our results provide a solid experimental ground for previous computational studies suggesting that the thermodynamics and kinetics of hydration of the ion-conducting pore are key aspects to understand the regulation of ion channels.

Keywords: channelrhodopsin, optogenetics, channel gating, infrared spectroscopy, time-resolved spectroscopy

Abstract

The discovery of channelrhodopsins introduced a new class of light-gated ion channels, which when genetically encoded in host cells resulted in the development of optogenetics. Channelrhodopsin-2 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, CrChR2, is the most widely used optogenetic tool in neuroscience. To explore the connection between the gating mechanism and the influx and efflux of water molecules in CrChR2, we have integrated light-induced time-resolved infrared spectroscopy and electrophysiology. Cross-correlation analysis revealed that ion conductance tallies with peptide backbone amide I vibrational changes at 1,665(−) and 1,648(+) cm−1. These two bands report on the hydration of transmembrane α-helices as concluded from vibrational coupling experiments. Lifetime distribution analysis shows that water influx proceeded in two temporally separated steps with time constants of 10 μs (30%) and 200 μs (70%), the latter phase concurrent with the start of ion conductance. Water efflux and the cessation of the ion conductance are synchronized as well, with a time constant of 10 ms. The temporal correlation between ion conductance and hydration of helices holds for fast (E123T) and slow (D156E) variants of CrChR2, strengthening its functional significance.

Ion channels are membrane proteins that mediate the passive movement of cations and anions across biological membranes, a process not only central for most living organisms but key to electrical excitability of cells. Upon activation, ion channels constitute a transient pathway to facilitate the permeation of ions across the cellular membrane. Ion channels can be switched, or gated, from a closed (nonconductive) to an open (conductive) state by external stimuli, such as ligands, voltage, or mechanical stress (1–3). Available structural information indicates that the ion-conducting pathway generally comprises a pore with wide regions solvated by water and constrictions sites formed by specific polar groups that confer ion selectivity (4). In the nonconductive state, the permeation of ions is prevented by energy barriers along the pore, either from physical occlusion or from the hydrophobic nature of residues lining the pore: the pore does not need to be physically occluded to be functionally closed (5). Habitual suspects for the gating mechanism, i.e., how the protein transits from the nonconductive to the conductive state, are diverse types of structural changes, such as orientation/rotation changes of transmembrane helices or of bulky (aromatic) side chains (6). Several computational studies have suggested a more subtle gating mechanism, where the thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydration of the ion-conducting pore might play a vital role (5, 7, 8). However, experimental support for this last proposal relies largely on studies on synthetic nanometric pores (9).

Channelrhodopsins (ChRs) belong to the new class of light-gated ion channels, i.e., ion channels activated by light absorption (10–12). Light-driven cation-selective conductance by ChRs was first proven in electrophysiological experiments on Xenopus oocytes and HEK cells expressing genetically encoded ChR1 or ChR2 from the unicellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (13, 14). The passive currents elicited by illumination of CrChR2 are sufficient to depolarize the cell membrane and to trigger action potentials in excitable cells, a feature that boosted the field of optogenetics (15). CrChR2 represents not only a successful optogenetic tool but a model system to characterize the nonequilibrium dynamics in the gating mechanism of an ion channel with unprecedented temporal resolution. Photoisomerization of the all-trans retinal chromophore around the C13=C14 bond, tightly coupled to structural changes of the peptide backbone (16), is the primary event in the activation of CrChR2. After this (sub)picosecond (<10−12 s) “proteinquake” (17), a series of thermally activated structural rearrangements and protonation changes lead to the formation (t1/2 ∼200 μs) and decay (t1/2 ∼10 ms) of the conductive state for cations (18). The resting dark state is recovered following two pathways: from the conductive state with t1/2 ∼10 ms, and from a desensitized state with t1/2 ∼20 s (19). The former pathway is predominant under single-turnover conditions (single flash excitation), whereas the latter is preferred under multiple-turnover conditions (continuous illumination), accounting for the decrease of the ion conductance of CrChR2 under sustained illumination (11). Similarly, channel desensitization/inactivation upon sustained stimuli also occurs in ligand-gated, voltage-gated, and mechanosensitive channels (2, 3, 20).

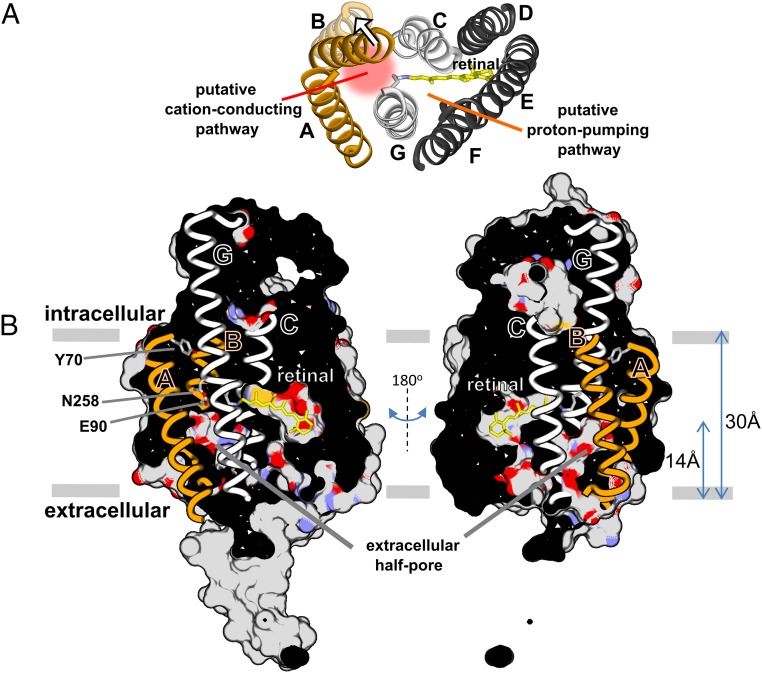

The crystal structure of a chimera of CrChR1 and CrChR2 (C1C2) in the dark (nonconductive) state showed that helices A, B, C, and G form an extracellular vestibule intruding halfway across the transmembrane part of the protein (Fig. 1), identified as part of the ion-conducting pathway (21). In support, exchanges of residues located in helices A, B, C, and G alter cation selectivity, even to the point to convert CrChR2 from a cation-selective to a chloride-conducting channel (22). Upon photoactivation, protein backbone changes are expected to extend the half-pore across the membrane. Indeed, molecular distances derived from pulsed electron–electron double resonance (pELDOR) spectroscopy indicate that the putative conductive state of CrChR2 exhibits an outward movement of the intracellular end of helix B by at least 2.5 Å (and of helix F to a lower degree) with respect to the nonconductive dark state (23), as illustrated in Fig. 1A. The tilt of helix B is preserved in the desensitized state (24). Projection maps at 6 Å resolution of the putative conductive state by cryoelectron microscopy indicate rearrangements not only in helix B and F but also in helix G (25). The static nature of the above experiments precluded the determination of the timing of these structural rearrangements. It was recently concluded from a combination of homology modeling and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that helix B tilts outwardly by 3.9 Å and a water-filled pore between helices A–C and G is formed within less than 100 ns after isomerization of the retinal from the all-trans to 13-cis conformation (26). Thus, helical tilt changes and water influx might precede the onset of ion permeation by more than three orders of time (<100 ns vs. ∼200 μs).

Fig. 1.

Structural model of channelrhodopsin-2 in the inactive dark-state, based on the C1C2 chimera (21). (A) Intracellular view of the seven transmembrane helices. Helices A, B, C, and G frame the putative ion-conductive pathway, whose activation presumably involves an outward tilt of helix B (see arrow). Helices C, D, E, F, and G enclose the retinal and line the proton-pumping pathway (19). (B) Lateral view of the solvent-accessible surface of C1C2, clipped in half. The solvent-accessible surface is colored by atom type for the transmembrane region [oxygen (red), nitrogen (purple), sulfured (orange), carbon (gray)] and in gray for the intracellular and extracellular areas. Note the presence of two important internal cavities: one is occupied by the retinal (yellow) and the other forms an intruding pore from the extracellular side with E90 (helix B) and N258 (helix G) located at its tip (21). The aromatic side chain of Y70 (helix A) forms an intracellular constriction site (21). Molecular drawings were performed with Ballview (70).

Here, we aimed at resolving and characterizing molecular events associated to the start and end of ion permeation of CrChR2 following a nanosecond laser pulse. We performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings on host cells expressing CrChR2, providing dynamics of ion conductance with microsecond resolution. These measurements were compared in detail to time-resolved UV/Vis and FTIR difference spectroscopy experiments on solubilized CrChR2, reporting on the dynamics of structural changes in the retinal and in the apoprotein. We identified changes at 1,665 and 1,648 cm−1 from the amide I vibration of the peptide backbone, which tally ion permeation. The same correlation holds for fast and slow variants of CrChR2, endorsing its functional significance. Inspection of the coupling of peptide backbone and vibrations of water molecules, assessed by comparing experiments in H216O and H218O, revealed that these two amide I bands report on the hydration of transmembrane α-helices. Our experimental results provide compelling evidence for water influx and efflux to tightly follow the start and end of ion permeation in CrChR2, respectively, in stark contrast to a previous suggestion (26).

Results and Discussion

Ion Conductance Correlates with Protein Backbone Conformational Changes.

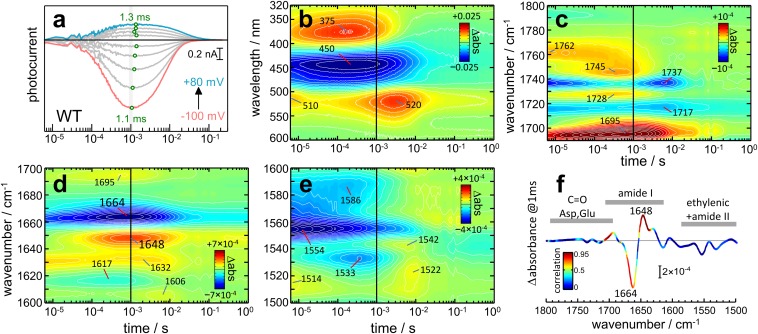

Ion permeation in CrChR2 was determined by recording light-induced currents (photocurrents) in HEK cells by patch-clamp electrophysiology (Fig. 2A), reporting on cation flow through the cell membrane (18). The short laser pulse (10 ns) ensured a single turnover of the photoreaction of CrChR2. Due to the clamped voltage, the photocurrents are directly proportional to transient changes in ion conductance of CrChR2, mostly to Na+ and H+ (27). The amplitude of the photocurrents is voltage dependent and typical for an inward rectified channel (28). The rise and decay of the photocurrents reflects the start (on-gating) and end (off-gating) of cation permeation, which are temperature, pH, and voltage dependent (14, 29). Nevertheless, the time of maximal conductance, tmax, is virtually voltage independent at a fixed temperature and pH, tmax = 1.2 ± 0.1 ms from −100 to +80 mV at 23 °C and pH 7.4 (Fig. 1A, open green circles), rendering tmax an ideal parameter for comparison with spectroscopic experiments on solubilized CrChR2. From the activation energy of the photocurrents (13), we extrapolated the tmax to be 1.0 ms at 25 °C, the temperature used in the spectroscopic experiments.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of time-resolved currents and absorption changes of CrChR2 wild type following pulsed (10 ns) light excitation. (A) Photocurrents at various voltages (from −100 to +80 mV in 20-mV steps) for CrChR2 expressed in HEK cells measured by whole-cell electrophysiology at 23 °C. The photocurrents at 0 mV were subtracted to remove/attenuate electrical signals unrelated to passive cation flow (see Fig. S7 for uncorrected photocurrents). The tmax of the currents is indicated by green open circles. (B–E) Color surface with 40 equidistant contour lines of the transient absorption changes of detergent solubilized CrChR2 at 25 °C at various spectral ranges. The vertical black line, at 1 ms, indicates the tmax of the photocurrents. (F) Infrared difference spectrum at 1 ms, colored by the correlation coefficient between the photocurrent at −40 mV and the transient absorption changes. Hotspots of high correlation (red) are predominantly located in the amide I region.

We performed time-resolved UV/Vis and FTIR spectroscopy on CrChR2 to gather additional information on the nature of the ion-conductive state. The former spectroscopy is the standard method to characterize intermediate states of retinal proteins from the electronic structure of the chromophore. The latter spectroscopy is particularly informative about the dynamics of conformational and protonation changes in proteins when probing vibrational modes of the protein backbone and of the side chain of amino acids (30, 31). Two bands are resolved at 375 and 520 nm in the photocycle of CrChR2 (Fig. 2B), from the P2390 and P3520 intermediates. These intermediate states reach a maximum accumulation at 150 μs and 3 ms, respectively (Fig. 2B), seven times before and three times after the tmax of the photocurrents, in agreement with a former report (18). Consequently, although ion permeation in CrChR2 is triggered by retinal photoisomerization, the ion-conducting state is not associated with a specific conformation/protonation state of the retinal. We arrived at the same conclusion upon analysis of the ethylenic (C=C) stretching vibrations of the retinal (Fig. 2E). It is noted that photocurrents and absorption changes in the UV/Vis spectral region have been measured for other less-studied ChRs as well. The photocurrents of ChR1 from Chlamydomonas augustae occur during the lifetime of the P2 intermediate (32), whereas those of a ChR1–ChR2 chimera from Volvox carteri (33) and of ChR2 from Platymonas subcordiformis (34) were assigned exclusively to the P3 intermediate. The diversity of intermediates associated to the conductive state further supports that factors other than retinal conformation/protonation state control ion permeation in ChRs.

The gating mechanism of ion channels typically involves protonation changes of the side chains of internal amino acids (35). Several protonation changes have been resolved after activation of CrChR2—namely, those of the retinal Schiff base and of the residues E90, D156, and D253 (18, 19, 36). Some of these proton transfer reactions account for the proton-pumping activity coexisting with ion permeation in CrChR2 (19, 29). Protonation changes and H-bonding changes of Asp and Glu side chains are monitored by the C=O stretching vibration of the COOH group, absorbing in the 1,780- to 1,690-cm−1 region (37), shown in Fig. 2C. Bands at 1,762(+), 1,745(+), and 1,737(−) cm−1 are from the terminal C=O of D156 (19, 38, 39), and bands at 1,728(+) and 1,717(−) cm−1 from E90 (19, 40). Noteworthy is that none of the above bands showed a bell-shaped evolution in logarithmic time scale akin to the photocurrents. The band at 1,695 cm−1 shows a bell-shaped temporal evolution, albeit peaking almost two times earlier than the photocurrents. Because only about a quarter of the intensity of this band is due to the C=O vibration of D253 (19), it is ambiguous at the present stage to conclude whether D253 remains protonated during the conductive state of CrChR2. This relevant issue will be clarified by analysis of the E123T variant (vide infra).

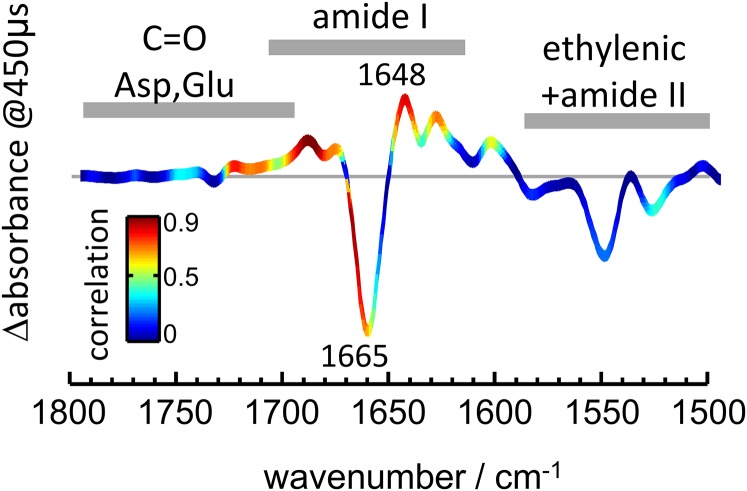

The frequency of the amide I vibration, a mode contributed mostly by the protein backbone amide carbonyl (C=O) stretching vibration, largely depends on H bonding and transition dipole–dipole interactions between peptide groups, rendering it sensitive to the protein structure (30, 41). Fig. 2D shows transient absorption changes between 1,700 and 1,600 cm−1, where amide I vibrations contribute. Intense bands at 1,664(−) and 1,648(+) cm−1, in the upper (42, 43) and lower (44, 45) range for amide I vibrations of α-helical structures in proteins and peptides, show a bell-shaped time evolution with maximum absorption changes at 0.8 and 1.0 ms, respectively (Fig. 2D), well in agreement with the tmax of the photocurrents (Fig. 2A). We conclude that ion permeation in CrChR2 tallies with changes in α-helices, the nature of which will be clarified in the following.

For a quantitative analysis, we cross-correlated the time traces between 1,800 and 1,500 cm−1 from IR spectroscopy and the photocurrents measured at −40 mV (Methods and Fig. S1). The goal was to identify vibrational signatures of molecular events that followed ion permeation. The cross-correlation coefficient R2 is presented color-coded on top of the light-induced IR difference spectrum extracted at 1 ms after the exciting laser pulse (Fig. 2F). Values close to 1 (red color) correspond to wavenumbers with kinetics highly similar to the photocurrents, whereas those close to 0 (blue color) do not show any similarity. Hotspots indicating high correlation (R2 > 0.8) are clustered within three spectral intervals: 1,709–1,698, 1,672–1,665, and 1,652–1,637 cm−1. These are regions typical for amide I vibrations, but the former interval does also contain contributions from the C=O stretch of D253. The value of R2 is <0.25 in the ethylenic region of the retinal and <0.4 in most of the carboxylic region (Fig. 2F), illustrating how ion permeation poorly correlates with structural changes of the retinal chromophore and with the protonation and H-bonding states of E90 and D156 (Fig. S1 A and B).

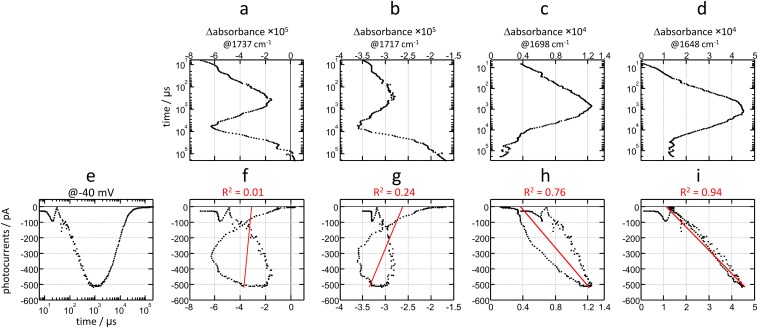

Fig. S1.

Illustration of the correlation procedure used in the manuscript to compare time traces from absorbance changes and photocurrents. Absorbance changes at (A) 1,737 cm−1 (D156), (B) 1,717 cm−1 (E90), (C) 1,698 cm−1 (D253 + other), and (D) 1,648 cm−1 (hydrated helices) are compared with (E) the photocurrents at −40 mV. (F–I) These absorption changes are represented as a function of the photocurrents (black dots) and fitted by linear regression (red line). The correlation coefficient (R2), calculated with the MATLAB function regress, summarizes the similarity of the compared time traces. We accounted for differences in temperature between the photocurrents and the absorption changes (23 °C vs. 25 °C) by rescaling the time of the photocurrents by 0.83. To make the calculation of the correlation possible, the photocurrents and the absorption changes were interpolated to 200 common time values, uniformly spaced in logarithmic scale from 6 μs to 200 ms.

Spectral Changes in the Amide I Region Report on the Hydration of Transmembrane Helices.

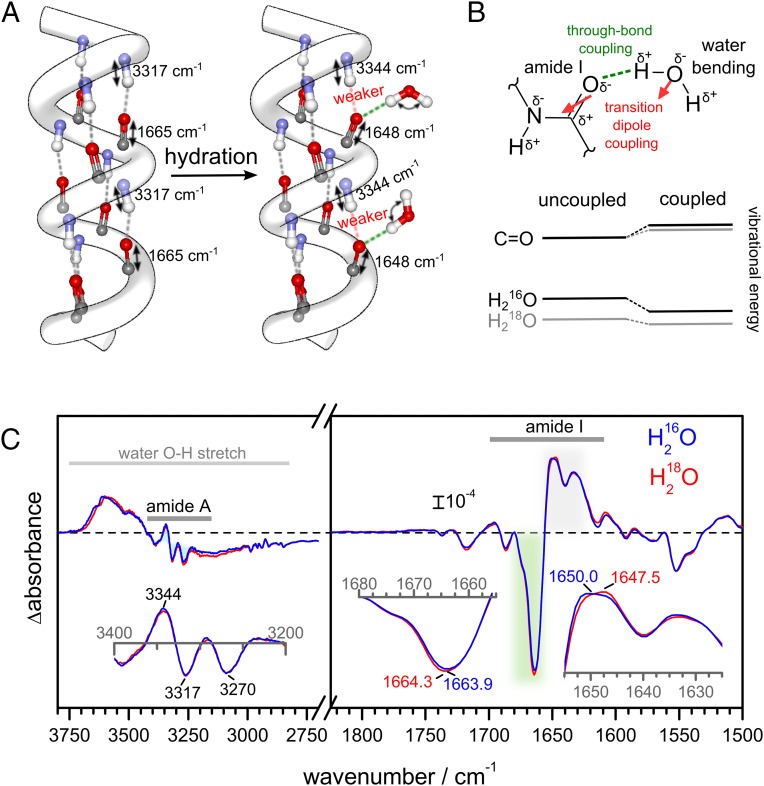

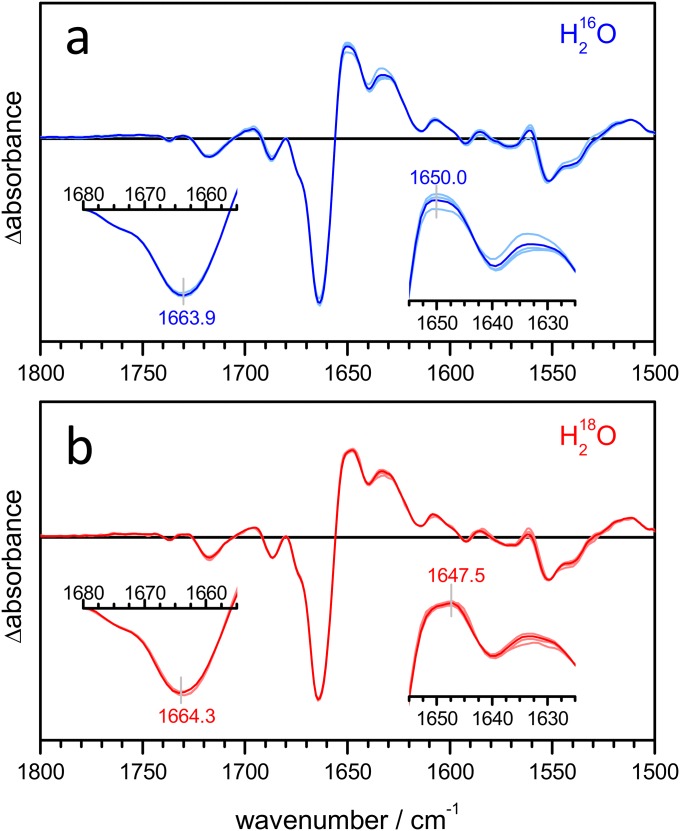

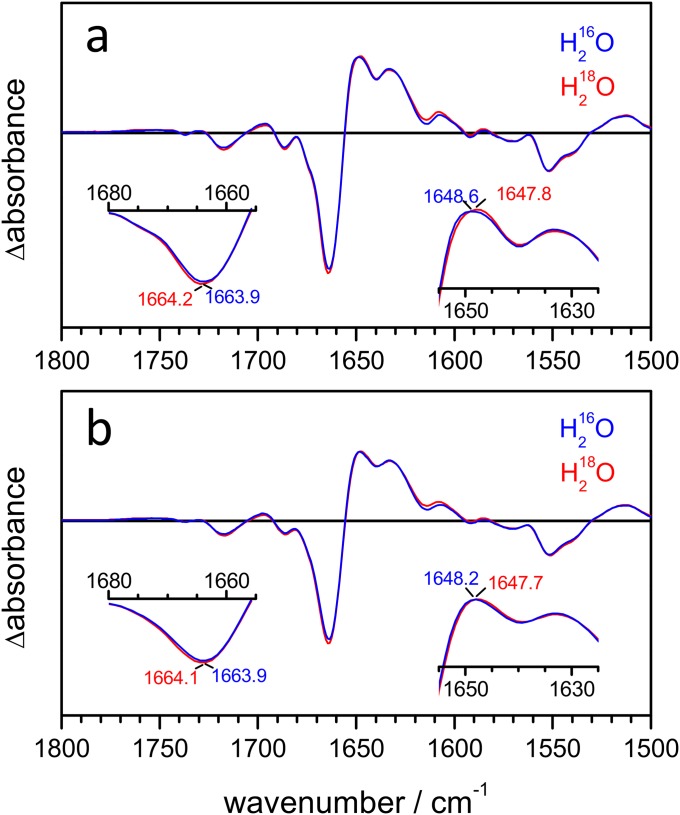

It has been shown that the amide I frequency of α-helices downshifts upon hydration (46) when the backbone carbonyl group forms a bifurcated H bond to a water molecule (Fig. 3A). To test if the frequency shift from 1,665 to 1,648 cm−1 in CrChR2 might report on the hydration of transmembrane helices as well, we examined the coupling between the amide I and the water-bending vibrational mode. These two vibrational modes exhibit a similar frequency and, thus, will couple in hydrated helices (Fig. 3B). The presence of vibrational coupling between amide and water vibrations can be assessed by comparing experiments in H216O and in H218O (Fig. 3B), because the latter molecule displays a 7-cm−1 lower bending vibrational frequency (47).

Fig. 3.

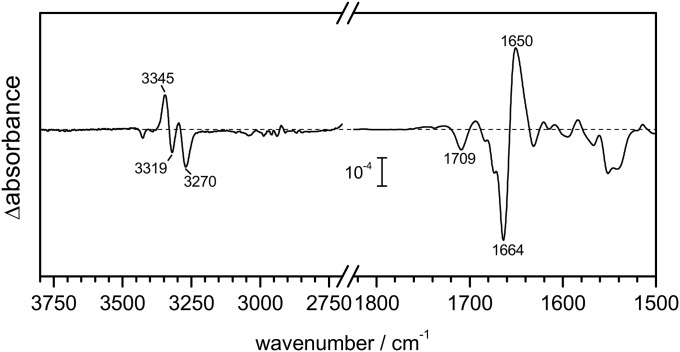

Hydration of helices monitored by amide A and I vibrations. (A) Sketch showing the effect of H bonding of water molecules to amide carbonyl groups on the amide I (C=O stretch) and amide A (N–H stretch) frequencies. (B) An amide carbonyl H-bonded to water shows through-bond coupling and through-space coupling (between the dipole moments of the two vibrations). The vibration of the C=O group is different when interacting with H216O and H218O. (C) Steady-state light-induced IR spectra at 2-cm−1 resolution of CrChR2 hydrated with either H216O (blue curve) or H218O (red curve) between 3,800 and 2,700 cm−1 (Left) and 1,825 and 1,500 cm−1 (Right). The slight differences in band position between steady-state (C) and time-resolved (Fig. 2 D and F) difference spectra are due to the higher spectral resolution of the former experiments (Fig. S8). (Inset, Left) Zoom-in of the 3,400- to 3,200-cm−1 region (amide A) after baseline correction and (Inset, Right) zoom-in of the 1,680- to 1,655-cm−1 and 1,655- to 1,625-cm−1 amide I regions. Note how the positive band at 1,650 cm−1 downshifts to 1,647.5 cm−1 in H218O.

We measured light-induced steady-state IR difference spectra of CrChR2 using either H216O or H218O as a solvent (Fig. 3C, Right). The frequency of the negative band at 1,664 cm−1 hardly shifted upon H218O exchange: 0.4 ± 0.3 cm−1 (±SD, n = 3). The maximum of the positive band at 1,650 cm−1, however, clearly downshifted by 2.5 ± 0.3 cm−1 in H218O (see Fig. S2 for replicate spectra). These results strongly support the assignment of the 1,648-cm−1 band to the amide I vibration of hydrated helices (Fig. 3A).

Fig. S2.

Steady-state FTIR difference spectra of ChR2-WT at 2 cm−1 resolution hydrated with (A) H216O and (B) H218O. Three replicates are shown in pale blue/red colors, with the average shown in blue/red. Note how band positions are preserved between replicates despite some differences in band intensity.

An amide C=O group at position i forming an H bond with water preserves the standard helical H bond to an amide proton at position i + 4 (48), although distorted and slightly weaker (for soluble proteins the amide N to carbonyl O distance in α-helices increases from 2.91 to 3.09 Å on average upon hydration) (49). As a consequence, whereas the amide I frequency of the residue i is downshifted (46), the backbone N–H stretch (amide A) frequency of the residue i + 4 will upshift upon hydration, a useful spectral marker for further confirmation of the hydration of helices. We characterized the changes in the amide A region (∼3,350–3,200 cm−1) of CrChR2 (Fig. 3C, Left). The amide A frequency increased after illumination as expected for the formation of intermolecular H bonds between helices and water, with three major bands at 3,344(+), 3,317(−), and 3,269(−) cm−1. The presence of two negative bands in the amide A (3,317 and 3,269 cm−1) is related to two strongly overlapped negative bands in the amide I region at 1,665 cm−1 and 1,662 cm−1 (19), the latter assigned to an helix distortion coupled to retinal isomerization (16). The amide A and I frequencies assigned to dehydrated transmembrane helices in CrChR2 (3,317 and 1,665 cm−1) are not far from those of the transmembrane helices of bacteriorhodopsin (50), a protein with well-packed and largely water-inaccessible transmembrane helices. The upshift of the amide A frequency upon hydration (from 3,317 to 3,344 cm−1) is coherent with weaker intermolecular H bond between the amide C=O and N–H groups (41), which might contribute to increase the structural flexibility of the hydrated helices. Indeed, an increase of flexibility of helix B has been proposed to occur upon formation of the conductive state (25). Nevertheless, even if potentially more flexible, the hydrated helices remain structurally stable, as concluded by the insensitivity of the amide A bands when the protein was illuminated in the presence of D2O (Fig. S3). Given the requirement that H bonds need to be transiently broken for H/D exchange to occur (51), the H/D exchange resistance of the amide groups attest to the strong stability of the intermolecular H bond between the amide C=O and N–H groups also in hydrated helices.

Fig. S3.

Steady-state light-induced FTIR difference spectrum of ChR2-WT hydrated with D2O (>24 h incubation). Note how the intensity and position of the amide A bands are preserved in D2O (compare with Fig. 3 in the MS), indicating that they arise from amide groups in secondary structures fully resistant to H/D exchange.

Lifetime Distribution of the Kinetics of Cation Permeation and Protein Backbone Conformational Changes.

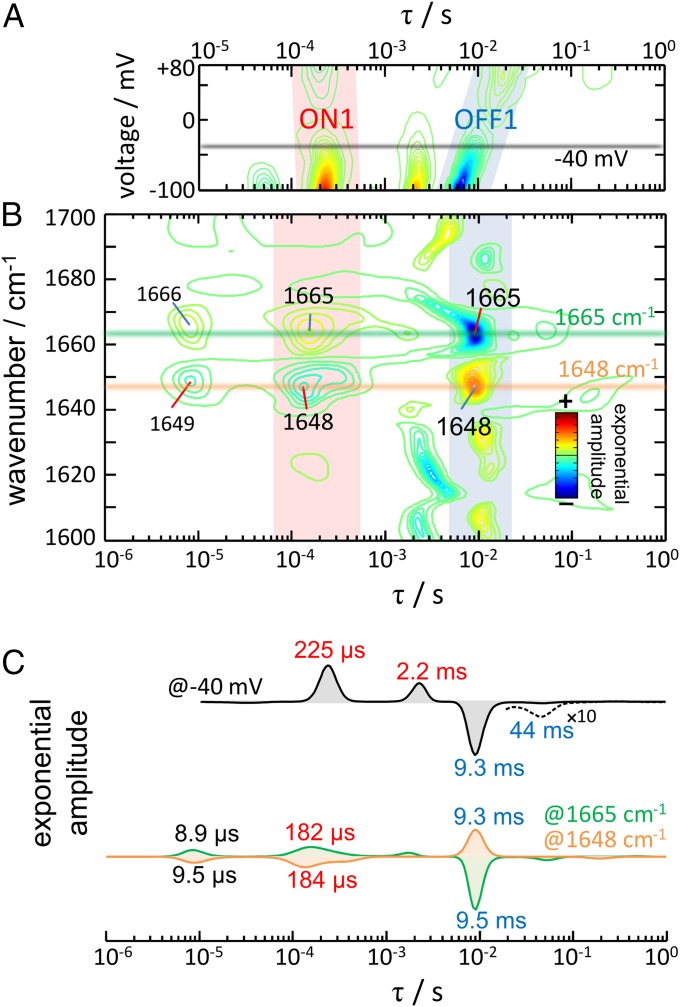

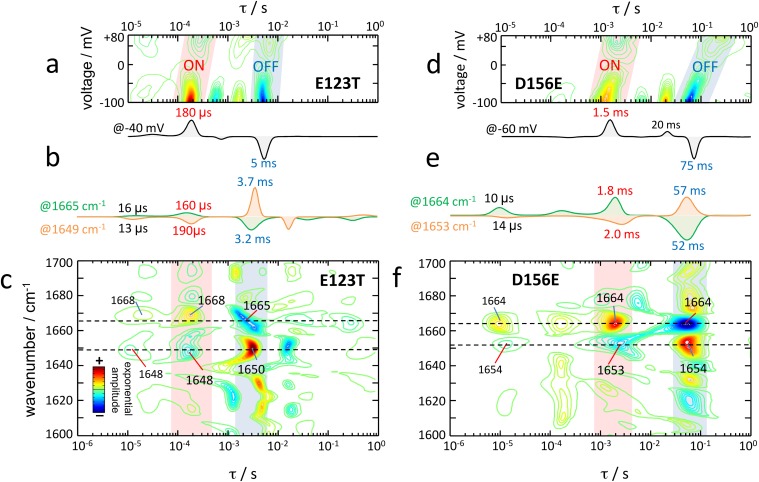

To gather additional kinetic information regarding channel on- and off-gating steps, and their connection to hydration of the protein interior, we performed a maximum-entropy lifetime distribution analysis (52). For the photocurrents, the lifetime distribution provides the density of exponential amplitudes as a function of the time constant and the membrane voltage (Fig. 4A). For the absorption changes in the IR, the lifetime distribution provides exponential amplitudes as a function of the time constant and the wavenumber (Fig. 4B and Fig. S4), with bands resolved according to their kinetics of appearance/disappearance and vibrational frequency. The benefit of a lifetime distribution analysis over other approaches is that it does not assume a prefixed number of exponential processes or require assumption of a specific kinetic model. Note that, as in any exponential analysis, in a lifetime distribution, positive amplitudes correspond to decaying kinetics and negative amplitudes to rising kinetics.

Fig. 4.

Lifetime distribution analysis of the photocurrents and the absorption changes in the amide I region. (A) Contour plot of the amplitude of the photocurrents to respect the time constant and the voltage. (B) Contour plot of the amplitude of the absorption changes with respect to the time constant and the wavenumber. For better band resolution, the time-resolved spectra were mathematically narrowed by Fourier deconvolution before performing the lifetime distribution analysis (see Fig. S4 for the lifetime distribution without band narrowing). (C) Comparison of the lifetime distribution of the photocurrents at −40 mV and of the absorption changes at 1,664 and 1,647 cm−1.

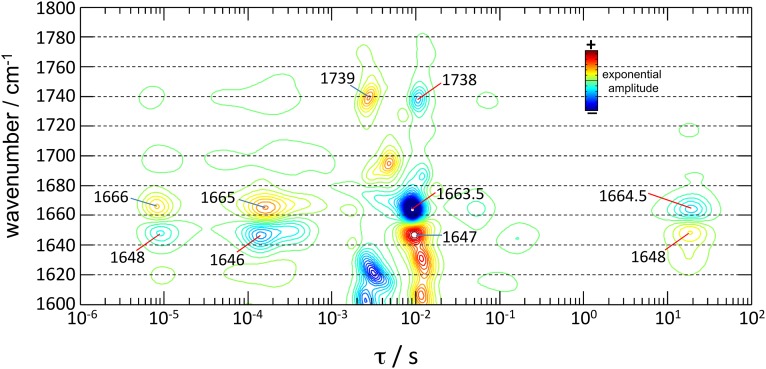

Fig. S4.

Lifetime distribution of ChR2-WT in the 1,800- to 1,600-cm−1 region. The lifetime distribution was estimated by the maximum entropy method, and bands resolved according to their wavenumber and time constant for rise (blue) and decay (red). Bands from dry (∼1,665 cm−1) and hydrated helices (∼1,648 cm−1) are labeled, as well as bands indicative of protonation changes of D156 (∼1,738 cm−1). Contrary to Fig. 4, the MS spectra were not narrowed by Fourier self-deconvolution before estimating the lifetime distribution.

The rise and the decay of the photocurrents contain at least two exponential components each (Fig. 4A), as best appreciated in a slice of the lifetime distribution at −40 mV (Fig. 4C, black trace). Cation permeability rises and decays in two steps to which we will refer hereon as channel on-gating step 1 (ON1) and step 2 (ON2). The most intense and faster component (ON1) peaks at τ = 225 μs at −40 mV (70% of the area), whereas the slower and smaller component (ON2) does it at τ = 2.2 ms (30% of the area). The time constant for ON1 is barely affected by voltage (τ = 225 μs at −100 mV and τ = 200 μs at +80 mV) and modestly for ON2 (τ = 2.1 ms at −100 mV and τ = 4.3 ms at +80 mV). Channel off-gating occurs mostly with one exponential component (τ = 9.3 ms at −40 mV, with 96% of the area), to which we will refer hereon as channel off-gating step 1 (OFF1). The time constant for OFF1 is markedly delayed as the membrane voltage becomes more positive: τ = 6.3 ms at −100 mV and τ = 21.3 ms at +80 mV (note the tilt of the blue blurred area in Fig. 4A). The second component for the decay of the photocurrents, τ = 44 ms with 4% of the area at −40 mV (Fig. 4C, black trace), is strongly delayed at positive voltages: τ = 37 ms at −100 mV and τ = 190 ms at +80 mV. Time constants with confidence limits at −100, 40, and +80 mV are collected in Table S1.

Table S1.

Time constants for the photocurrents and for amide I absorption changes

| Electrophysiology | Infrared spectroscopy | |||

| −100 mV | −40 mV | +80 mV | 1,665 cm−1 | 1,648 cm−1 |

| 8.9 ± 0.4 μs | 9.5 ± 0.4 μs | |||

| 225 ± 4 μs | 225 ± 8 μs | 200 ± 10 μs | 182 ± 8 μs | 184 ± 7 μs |

| 2.1 ± 0.1 ms | 2.2 ± 0.1 ms | 4.3 ± 0.3 ms | ||

| 6.3 ± 0.1 ms | 9.3 ± 0.1 ms | 21.3 ± 0.3 ms | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.5 ms |

| 37 ± 3 ms | 44 ± 6 ms | 190 ± 15 ms | ||

| 18 ± 2 s | 19 ± 3 s | |||

Time constants were determined from a maximum entropy lifetime distribution analysis, as the first moment (mean). The confidence interval is given plus/minus 2× the SD of the first moment, calculated by a multidimensional Gaussian approximation to the posterior probability (Methods).

The lifetime distribution in the 1,700- to 1,600-cm−1 region of CrChR2 resolves several components (Fig. 4B). The prominent kinetics at ∼1,665 and 1,648 cm−1 report on the hydration of transmembrane helices as was deduced above. Applying an empirical expression that successfully modeled the effect of hydration on the amide I vibration frequency of peptides and proteins (53), the observed downshift of the amide I band by 17 ± 1 cm−1, indicates an H-bond distance of 2.03 ± 0.03 Å between the amide C=O and water (carbonyl O to water H distance) in CrChR2. This distance is longer than average H bonds of liquid water, 1.88 Å (54), and thus presumably weaker, but similar in length as the intermolecular amide H bond of a canonical α-helix (2.06 ± 0.16 Å) (55).

Fig. 4C reproduces the lifetime distribution at 1,665 (green trace) and at 1,648 cm−1 (orange trace), reporting on the kinetics of dry and hydrated helices, respectively. The traces are almost mirror images as expected. The former distribution shows main components at τ = 8.9 μs, 182 μs, 9.5 ms, and 18 s, and the latter at τ = 9.5 μs, 184 μs, 9.3 ms, and 19 s. It is apparent that similar time constants are observed for the main rise and decay of bands reporting the hydration of helices and for channel on- and off-gating: ∼200 μs and ∼9 ms (Fig. 4C). Close agreement between the lifetime distributions indicates a very similar dynamic for ion permeation and hydration of transmembrane helices.

The lifetime distribution of the photocurrents and of the absorption changes in the amide I region resolves additional components, specific either to ion permeation and/or to the hydration of helices. First, one-third of the amplitude for the bands reporting the hydration of helices rises with τ ∼ 9 μs, largely preceding ion permeation. Second, the step where cation conductance increases from 70% to 100% (ON2, τ = 2 ms) is not associated with helix hydration; instead, it correlates with small components in the lifetime distribution at 1,690(+), 1,672(−), 1,620(−), and 1,603(−) cm−1 (Fig. 4B). These bands might correspond to backbone amide I vibrations but also to H-bonding changes in Tyr, Lys, Arg, Asn, and/or Gln side chains (30). The ON2 step also correlates with a component at 1,739(+) cm−1 in the carboxylic region (Fig. S4), reporting on the deprotonation of D156 (19). Finally, 25% of the hydration of helices decays with τ ∼ 18 s (Fig. S4), when the nonconductive desensitized state decays to the initial dark state.

Fast and Slow Functional Variants of CrChR2.

The analysis of photocurrents and of the time-resolved IR spectroscopic experiments provides evidence that the ion permeation in CrChR2 and the hydration of transmembrane helices are temporally correlated. We should note, however, that electrophysiological experiments on CrChR2 were conducted in the complex cellular membrane of the host cell, and the spectroscopic experiments were performed on solubilized and purified CrChR2. Because of these differences in the protein’s environment, we scrutinized the above temporal correlation using two functional CrChR2 variants with accelerated (56) and delayed (19) photocurrents: CrChR2-E123T and CrChR2-D156E.

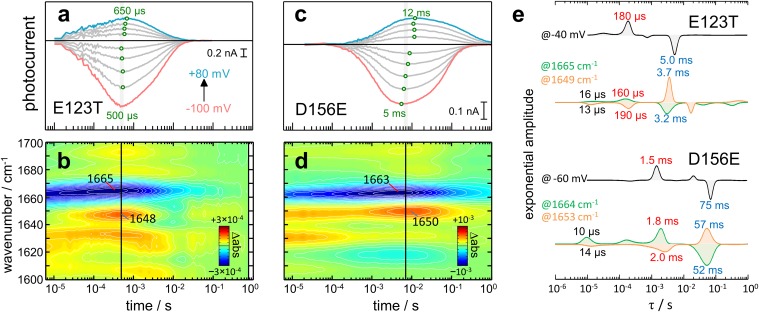

In CrChR2-E123T, the photocurrents are faster than in the wild type (compare Fig. 5A and Fig. 2A). The time of maximal conductance is voltage-insensitive and is reached at ∼550 μs, i.e., two times earlier than in CrChR2-WT (Fig. 5A). Time-resolved IR difference spectra of CrChR2-E123T (Fig. 5B) exhibit intense amide I bands at 1,665(−) and 1,648(+) cm−1, which reach maximum amplitude at 350 and 500 μs, respectively, correlating well with the tmax of the photocurrents (extrapolated to 450 μs at 25 °C). When quantitatively comparing the transients from IR spectroscopy to the photocurrents, high cross-correlation (R2 > 0.8) appears predominantly in the amide I region (Fig. S5), at similar wavenumbers as in CrChR2-WT. Notably, good correlation (R2 > 0.6) is also observed between 1,730 and 1,712 cm−1, near the frequency of the C=O stretch of the side chain of D253 in the E123T variant (19), indicating that D253 remains protonated during the conductive state, coherent with indications from CrChR2-WT.

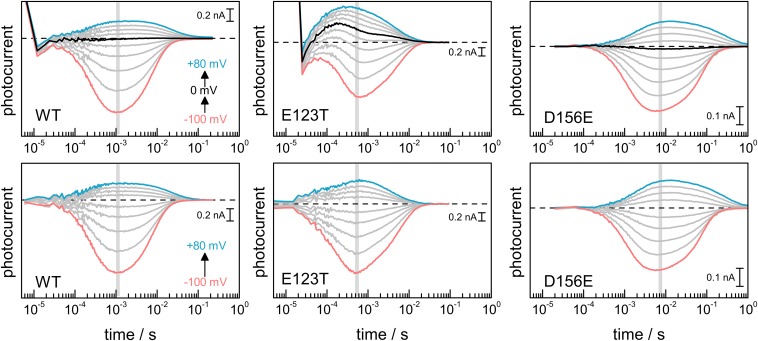

Fig. 5.

Comparison of time-resolved currents and absorption changes of fast (E123T; Left) and slow (D156E; Right) CrChR2 variants after 10 ns light excitation. (A and C) Photocurrents at various voltages: (A) CrChR2-E123T and (C) CrChR2-D156E. The maximum (tmax) of the currents is indicated by green open circles. (B and D) Color surface of the transient absorption changes in the amide I region: (B) CrChR2-E123T and (D) CrChR2-D156E. (E) Comparison of the lifetime distribution of the photocurrents and the amide I changes for CrChR2-E123T and CrChR2-E156E.

Fig. S5.

IR difference spectrum of ChR2-E123T 450 μs after photoexcitation, color-coded by the correlation coefficient with the photocurrents at −40 mV. Details of the correlation procedure are given in Fig. S1.

In CrChR2-D156E, channel on- and off-gating are delayed with respect to CrChR2-WT at all voltages (compare Figs. 5C and 2A). The time for maximal conductance depends on the voltage, ranging from 5 to 12 ms (Fig. 5C), i.e., 5–12 times slower than in CrChR2-WT. Time-resolved IR spectral changes in the amide I region show intense bands at 1,663(−) and 1,650(+) cm−1 peaking at 5 and 9 ms, respectively (Fig. 5D), correlating reasonably well with the tmax of the photocurrents.

We performed a lifetime distribution analysis on the E123T and D156E variants (Fig. S6). At −40 mV, channel on- and off-gating in CrChR2-E123T occurs predominantly with τ = 180 μs and τ = 5.0 ms, respectively (Fig. 5E). In good agreement, the lifetime distribution of the absorption changes at 1,665 and 1,649 cm−1 shows major components at τ ∼ 170 μs and τ ∼ 3.4 ms (Fig. 5E). In CrChR2-D156E, on- and off-gating occurs predominantly with τ = 1.5 ms and τ = 75 ms at −60 mV (Fig. 5E). Accordingly, the lifetime distribution of the absorption changes at 1,664 and 1,653 cm−1 shows major components at τ ∼ 1.9 ms and τ ∼ 55 ms (Fig. 5E).

Fig. S6.

Lifetime distribution of (A and D) the photocurrents and (C and F) the absorption changes in the 1,700– to 1,600-cm−1 region for (A–C) ChR2-E123T and (D–F) ChR2-D156E. Lifetime distributions were estimated by the maximum entropy method. In C and F, only bands assigned to dry and hydrated helices are labeled. (B and E) Extracted lifetime distribution at a representative voltage and wavenumber values.

General Discussion

Our understanding of ion channels in the past two decades has progressed thanks to static atomic structural information on trapped inactive and conducting states, complemented by dynamic information from MD trajectories. Structural methodologies have typically emphasized conformational changes in the protein (in secondary/ternary motives or at the side chain level) as determinant for gating (6), whereas MD studies stress dynamical aspects in the nanosecond time scale, often of water molecules (5). More recently, in a full-atom MD study on a voltage-gated potassium channel running for hundreds of microseconds, water dynamics and structural changes in the protein were sampled across the relevant time scale for channel gating, providing mechanistic insights into activation and deactivation mechanisms (57). Common alternative approaches to gather additional information on channel gating are voltage-clamp fluorimetry (58) or cysteine scanning mutagenesis with thiol reactants (59). IR spectroscopy, however, is a label-free technique that combines notable structural sensitivity and excellent temporal resolution. In the past, steady-state IR spectroscopy has been used to obtain information about the gating mechanism of pH and ligand-gated ion channels (60, 61). Technical challenges have limited so far the application of time-resolved IR spectroscopy to study the dynamics of ion channels (62).

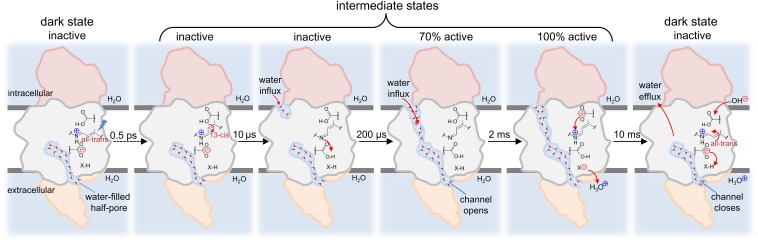

CrChR2, with its light sensitivity, represents a model system to integrate time-resolved electrophysiology and optical spectroscopies with microsecond resolution. Comparing the dynamics of ion conduction with those of conformational changes reveals that the conductive state of CrChR2 is not characterized by a specific state of the retinal chromophore but specifically correlates with a shift of the peptide backbone amide I vibration from 1,665 to 1,648 cm−1. The correlation between ion conduction and amide I spectral changes is functionally relevant, because it is also observed in two CrChR2 variants with altered kinetics of ion permeation (Fig. 5). We have established, by exploiting vibrational coupling, that these two amide I bands report on the hydration of transmembrane α-helices: 1,665 cm−1 for dry and 1,648 cm−1 for hydrated helices (Fig. 3). Thus, the start (τ ∼ 200 μs) and end (τ ∼ 10 ms) of cation permeation in CrChR2 involves influx and efflux of water into transmembrane regions. In addition, we observed some reporter bands for the hydration of transmembrane helices at τ ∼ 10 μs, i.e., before cation permeation starts (Fig. 4 B and C). Therefore, water influx to hydrate transmembrane helices occurs in two steps. One-third of the hydration of helices takes place with τ ∼ 10 μs, an amount apparently insufficient to trigger ion conductance. The remaining two-thirds occur with τ ∼ 200 μs, presumably forming a continuous water-pore competent for ion conduction. A similar behavior is observed in CrChR2-E123T and CrChR2-D156E variants (Fig. 5). The main hydration phase correlates with the on-gating kinetics in both variants (τ ∼ 180 μs in CrChR2-E123T and τ ∼ 1.5 ms in CrChR2-D156E), whereas a minor hydration step occurs at ∼10–15 μs in both variants independently of differences in the start of ion permeation. However, the closing of the channel correlates in all variants with the dewetting of helices, which follows dark-state recovery: τ ∼ 10 ms in CrChR2-WT, τ ∼ 4 ms in CrChR2-E123T, and τ ∼ 60 ms in CrChR2-D156E. Combining our current results with previous studies focused on proton transfer reactions (19), we can now derive a simple model comprising the timing of relevant events during the functional mechanism of CrChR2 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the gating steps in channelrhodopsin-2 following light excitation, including water influx and efflux steps, retinal isomerization, and proton transfers involved in proton pumping (and potentially in the gating mechanism). Water influx takes place in two cooperative steps (τ = 10 and 200 μs). Cation permeation starts with τ = 200 μs, when the hydration of the pore is completed, and ends with τ = 10 ms, when half of the pore dewets and collapses. The carboxylic groups above and below the retinal (only a small part of the retinal molecule is shown) correspond to D156 and D253, respectively. X–H it is the terminal proton release group, still unassigned.

Our present data does not provide clear-cut information regarding the location of the hydrated α-helical segments, but we can assume to be those surrounding the putative cation pathway, i.e., between helices A, B, C, and G (Fig. 1A). An open question remains how many water molecules, besides those already present in the dark state, are required in transmembrane regions to allow for ion permeation in CrChR2. We can roughly estimate from the area of the amide I band at 1,648 cm−1 that ∼10 backbone carbonyls get engaged in additional H bonds to water in the conductive state, using as an internal standard the band at 1,738 cm−1 from D156 and accounting for differences in the integrated extinction coefficient between the C=O stretch of amide and carboxylic groups (63). Because of the 3.6 periodicity of helices (∼11 residues to complete three turns), and considering four helices framing the ion-conducting pore, 10 water molecules would be sufficient to hydrate all of the backbone carbonyls in a pore of 12 Å in length (or 16 Å considering the involvement of only three helices). Such length would be roughly sufficient to form a transmembrane pore when considering that a half-pore 14 Å long is already present in the dark-state structure (Fig. 1B). Likely, more than 10 additional water molecules are required for ion permeation, but not detected here because they do not interact with backbone carbonyl groups but with polar side chains or with other water molecules. As a reference, in voltage-gated potassium channels there is an influx of 40–50 water molecules in the transition between the resting and active states (57, 64).

The fast phase for water influx (τ ∼ 10 μs) temporally correlates with the deprotonation of the retinal Schiff base in CrChR2 (19). Bacteriorhodopsin, structurally homologous to ChRs, shows a small outward tilt of helix B when the retinal Schiff base deprotonates (65), which might also occur in CrChR2 and account for the early phase of water influx. A water-filled ion-conducting pore is formed in ChR2 with τ ∼ 200 μs, likely coupled to a large outward tilt of helix B by 2.5–4 Å (23, 24). The helix tilt cannot be directly detected in our spectroscopic experiments, performed in nonoriented samples. An open question unresolved by our current data is the molecular connection between the two hydration phases and the tilt of helix B. The formation of the pore by the tilt of helix B will be initially opposed by surface tension, largely reduced once the pore gets sufficiently wet (7). Two extreme scenarios are possible: structural changes during the photocycle build a pore that becomes then hydrated (water follows protein kinetics), or, at the other extreme, water penetration allows for structural changes to occur by cooperatively reducing the initial surface tension opposed to the formation of a pore (protein follows water kinetics). The first step for helix hydration, with τ ∼ 10 μs, might be rate limited by water dynamics given its minor sensitivity to mutations that change the photoreaction kinetics. In contrast, the time constant for the second hydration step (τ ∼ 200 μs) and for the dehydration step (τ ∼ 10 ms) are prominently modulated by mutations affecting the photoreaction kinetics, pointing to protein dynamics instead of water dynamics as the rate-limiting step for channel opening and closing. However, the dynamics of large-scale protein changes from microseconds to seconds have been proposed to be slaved to water dynamics (66). Thus, it is ambiguous to conclude whether the tilt of helix B or water penetration itself is the rate-limiting step controlling the formation of the ion-conducting pore in CrChR2, because both can be tightly connected. Future experiments altering the solvent viscosity, and thus water dynamics, might allow settling the connection between protein and solvent dynamics in the activation and deactivation mechanism of CrChR2.

Though ion permeation occurs concomitantly with the hydration of helices (τ ∼ 200 μs), there is a ∼1.5-fold increase in cation conductance at a later stage (τ ∼ 2 ms; Fig. 4 A and C). Interestingly, this rise in conductance lacks spectral changes associated with the hydration of helices (Fig. 4B), i.e., cation conductance in CrChR2 increased without an apparent additional influx of water molecules. The transition between the P2390 and P3520 intermediates also takes place with τ ∼ 2 ms (19). In this step the retinal SB is reprotonated from D156, and a proton is released from an unknown group to the extracellular side. H-bond rearrangements following protonation changes might affect the polarity of the ion-conducting pore, or electrostatic changes might locally increase the voltage, accounting for the increase in cation conductance.

Our spectral correlation analysis indicates that D253 gets and remains protonated in the conductive state: the kinetics of the absorption changes at 1,695 cm−1 for CrChR2-WT and at 1,715 cm−1 for CrChR2-E123T exhibit good correlation with the photocurrents (note that the C=O stretch of D253 is upshifted in the E123T variant) (19). We have shown before that the D253N variant displays hardly any photocurrents, indicating the essential role of protonation changes of D253 in the functional mechanism of CrChR2, but nevertheless it still displays bands characteristic for hydration of helices (19). Likewise, the desensitized state of CrChR2 still shows amide I bands from hydrated helices but low or no conductance (19). Both observations indicate that water influx is required but not sufficient for ion permeation. As an example, in the active state of a voltage-gated potassium channel, permeation is suddenly halted upon interaction of specific side chains that block the pore, with only a 25% drop in the number of water molecules in the channel (57). A conceptually similar mechanism might be operative in CrChR2, dependent on the protonation state of D253, blocking ion permeation with minor changes in the water content.

In summary, we have obtained experimental information on the gating mechanism of an ion channel by cross-correlating time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy and electrophysiology. Structural changes in transmembrane helices are required for formation of the pore, but ion permeation is coupled to water influx. Future work should aim at clarifying whether structural changes builds a pore that becomes rapidly hydrated and competent for ion conduction or, conversely, lubrication allows for structural changes to occur by cooperatively reducing the surface tension opposed to the formation of a pore.

Methods

Photocurrents of CrChR2 in HEK cells at room temperature (23 °C) were initialed by a short laser pulse (10 ns, 450 nm, 50–150 µJ/mm2) and recorded at different holding potentials (−100 to +80 mV in 20-mV steps) as described (19). The photocurrents were logarithmically averaged to 50 points per decade. We subtracted the photocurrents recorded at 0 mV to correct for excitation artifacts and residual active currents (Fig. S7 shows the uncorrected data). For spectroscopic studies, CrChR2 was heterologously expressed in Pichia pastoris and purified by NTA affinity chromatography. The purified protein was solubilized in 0.2% decyl maltoside, 100 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) as done before (19). Time-resolved FTIR experiments on hydrated films of detergent solubilized CrChR2 were performed at 8 cm−1 spectral resolution (19, 67) using a commercial FTIR spectrometer (Vertex 80v; Bruker). The sample holder was kept at 25 °C using a circulating water bath (F25; JULABO). Transient absorption changes in the UV/Vis for detergent-solubilized CrChR2 in solution were measured in a commercial flash photolysis (LKS80; Applied Photophysics), with the cuvette holder kept at 25 °C by a circulating water bath (F25; JULABO). In both cases, the sample was excited by a short (∼10 ns, λ = 450 nm, 3 mJ/cm2) laser pulse (λ = 470 nm for CrChR2-E123T). Controls confirmed that for hydrated films (∼93% relative humidity) the kinetic response was slowed down only by a factor of ∼1.5 to respect solution (19). Time-resolved FTIR and UV/Vis data were subjected to singular value decomposition (SVD) and reconstructed with a minimum of five SVD components. The correlation coefficient between the kinetics of the photocurrents and the absorption changes was calculated by linear regression using logarithmically spaced data. The procedure is illustrated in Fig. S1. Spectral band narrowing was performed by Fourier self-deconvolution (68). Lifetime distribution analysis was performed by the maximum entropy method, with a regularization value automatically determined by the L-curve method (52). The area and the time constant of a component were calculated from its zero and first moments, and its error represents a 96% confidence interval obtained from a multidimensional Gaussian approximation to the posterior probability (69). To detect amide A vibrations and the vibrational coupling between amide I and water vibrations steady-state FTIR difference spectra were recorded at 2 cm−1 resolution, alternating 30 s of darkness and 10 s of illumination with a blue light-emitting diode (λmax = 462 nm). Three independent samples were used, first hydrated with H216O and later with H218O, to obtain SDs for the observed spectral shifts.

Fig. S7.

(Upper) Uncorrected photocurrents for ChR2 wild-type, E123T, and D156E variants at various voltages. (Lower) Photocurrents corrected for the current recorded at 0 mV. The scaling factor used was optimized to remove the peak artifact below 20 μs, and ranged from 0.8 to 1.2 (for D156E, we used a fixed scaling factor of 1).

Fig. S8.

Steady-state FTIR difference spectra of ChR2-WT hydrated with H216O and H218O at (A) 4 and (B) 8 cm−1 instrumental resolution (see Fig. S2 for spectra at 2 cm−1 resolution). Note that as the spectral resolution is decreased, the positive band is downshifted (1,650.0, 1,648.6, and 1,648.2 cm−1 at 2, 4, and 8 cm−1 resolution), reducing the observed downshift in H218O (2.5, 0.8, and 0.5 cm−1 at 2, 4, and 8 cm−1 resolution).

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants SFB 1078/B3 (to J.H.) and B4 (to R.S.), Cluster of Excellence Frankfurt “Macromolecular Complexes” Grant (to E.B.), and the Max Planck Society (C.B and E.B).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1511462112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Isacoff EY. How does voltage open an ion channel? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:23–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020404.145837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naismith JH, Booth IR. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels--MscS: Evolution’s solution to creating sensitivity in function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:157–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-101211-113227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezanilla F. How membrane proteins sense voltage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):323–332. doi: 10.1038/nrm2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gouaux E, Mackinnon R. Principles of selective ion transport in channels and pumps. Science. 2005;310(5753):1461–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1113666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckstein O, et al. Ion channel gating: Insights via molecular simulations. FEBS Lett. 2003;555(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou HX, McCammon JA. The gates of ion channels and enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anishkin A, Akitake B, Kamaraju K, Chiang CS, Sukharev S. Hydration properties of mechanosensitive channel pores define the energetics of gating. J Phys Condens Matter. 2010;22(45):454120. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aryal P, Sansom MS, Tucker SJ. Hydrophobic gating in ion channels. J Mol Biol. 2015;427(1):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasaiah JC, Garde S, Hummer G. Water in nonpolar confinement: From nanotubes to proteins and beyond. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59:713–740. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stehfest K, Hegemann P. Evolution of the channelrhodopsin photocycle model. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11(6):1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, Heberle J. Channelrhodopsin unchained: Structure and mechanism of a light-gated cation channel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837(5):626–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spudich JL, Sineshchekov OA, Govorunova EG. Mechanism divergence in microbial rhodopsins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837(5):546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagel G, et al. Channelrhodopsin-1: A light-gated proton channel in green algae. Science. 2002;296(5577):2395–2398. doi: 10.1126/science.1072068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagel G, et al. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13940–13945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenno L, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. The development and application of optogenetics. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:389–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann-Verhoefen MK, et al. Ultrafast infrared spectroscopy on channelrhodopsin-2 reveals efficient energy transfer from the retinal chromophore to the protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(18):6968–6976. doi: 10.1021/ja400554y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansari A, et al. Protein states and proteinquakes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(15):5000–5004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamann C, Kirsch T, Nagel G, Bamberg E. Spectral characteristics of the photocycle of channelrhodopsin-2 and its implication for channel function. J Mol Biol. 2008;375(3):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, et al. Transient protonation changes in channelrhodopsin-2 and their relevance to channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(14):E1273–E1281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219502110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keramidas A, Lynch JW. An outline of desensitization in pentameric ligand-gated ion channel receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(7):1241–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1133-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato HE, et al. Crystal structure of the channelrhodopsin light-gated cation channel. Nature. 2012;482(7385):369–374. doi: 10.1038/nature10870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wietek J, et al. Conversion of channelrhodopsin into a light-gated chloride channel. Science. 2014;344(6182):409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.1249375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause N, Engelhard C, Heberle J, Schlesinger R, Bittl R. Structural differences between the closed and open states of channelrhodopsin-2 as observed by EPR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(20):3309–3313. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sattig T, Rickert C, Bamberg E, Steinhoff HJ, Bamann C. Light-induced movement of the transmembrane helix B in channelrhodopsin-2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(37):9705–9708. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller M, Bamann C, Bamberg E, Kühlbrandt W. Light-induced helix movements in channelrhodopsin-2. J Mol Biol. 2015;427(2):341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhne J, et al. Early formation of the ion-conducting pore in channelrhodopsin-2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(16):4953–4957. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider F, Gradmann D, Hegemann P. Ion selectivity and competition in channelrhodopsins. Biophys J. 2013;105(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bamann C, Nagel G, Bamberg E. Microbial rhodopsins in the spotlight. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(5):610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldbauer K, et al. Channelrhodopsin-2 is a leaky proton pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(30):12317–12322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barth A, Zscherp C. What vibrations tell us about proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35(4):369–430. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radu I, Schleeger M, Bolwien C, Heberle J. Time-resolved methods in biophysics. 10. Time-resolved FT-IR difference spectroscopy and the application to membrane proteins. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2009;8(11):1517–1528. doi: 10.1039/b9pp00050j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sineshchekov OA, Govorunova EG, Wang J, Li H, Spudich JL. Intramolecular proton transfer in channelrhodopsins. Biophys J. 2013;104(4):807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst OP, et al. Photoactivation of channelrhodopsin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(3):1637–1643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szundi I, Bogomolni R, Kliger DS. Platymonas subcordiformis Channelrhodopsin-2 (PsChR2) function: II. Relationship of the photochemical reaction cycle to channel currents. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(27):16585–16594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.653071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller C. ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens. Nature. 2006;440(7083):484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature04713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhauer K, et al. In channelrhodopsin-2 Glu-90 is crucial for ion selectivity and is deprotonated during the photocycle. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(9):6904–6911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie B, Stutzman J, Xie A. A vibrational spectral maker for probing the hydrogen-bonding status of protonated Asp and Glu residues. Biophys J. 2005;88(4):2833–2847. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nack M, et al. The DC gate in Channelrhodopsin-2: Crucial hydrogen bonding interaction between C128 and D156. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9(2):194–198. doi: 10.1039/b9pp00157c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, et al. Pre-gating conformational changes in the ChETA variant of channelrhodopsin-2 monitored by nanosecond IR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(5):1850–1861. doi: 10.1021/ja5108595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritter E, Stehfest K, Berndt A, Hegemann P, Bartl FJ. Monitoring light-induced structural changes of Channelrhodopsin-2 by UV-visible and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(50):35033–35041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806353200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1986;38:181–364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haris PI, Chapman D. Does Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy provide useful information on protein structures? Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17(9):328–333. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90305-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haris PI, Chapman D. The conformational analysis of peptides using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 1995;37(4):251–263. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venyaminov SYu, Kalnin NN. Quantitative IR spectrophotometry of peptide compounds in water (H2O) solutions. II. Amide absorption bands of polypeptides and fibrous proteins in α-, β-, and random coil conformations. Biopolymers. 1990;30(13-14):1259–1271. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarver RW, Jr, Krueger WC. Protein secondary structure from Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: a data base analysis. Anal Biochem. 1991;194(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh ST, et al. The hydration of amides in helices; a comprehensive picture from molecular dynamics, IR, and NMR. Protein Sci. 2003;12(3):520–531. doi: 10.1110/ps.0223003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lappi SE, Smith B, Franzen S. Infrared spectra of H216O, H218O and D2O in the liquid phase by single-pass attenuated total internal reflection spectroscopy. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2004;60(11):2611–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2003.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thanki N, Umrania Y, Thornton JM, Goodfellow JM. Analysis of protein main-chain solvation as a function of secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;221(2):669–691. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80080-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barlow DJ, Thornton JM. Helix geometry in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1988;201(3):601–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothschild KJ, Clark NA. Polarized infrared spectroscopy of oriented purple membrane. Biophys J. 1979;25(3):473–487. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85317-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates and pathways studied by hydrogen exchange. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, Kandori H. Bayesian maximum entropy (two-dimensional) lifetime distribution reconstruction from time-resolved spectroscopic data. Appl Spectrosc. 2007;61(4):428–443. doi: 10.1366/000370207780466172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamm P, Lim MH, Hochstrasser RM. Structure of the amide I band of peptides measured by femtosecond nonlinear-infrared spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(31):6123–6138. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Modig K, Pfrommer BG, Halle B. Temperature-dependent hydrogen-bond geometry in liquid water. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(7):075502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.075502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker EN, Hubbard RE. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1984;44(2):97–179. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(84)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunaydin LA, et al. Ultrafast optogenetic control. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(3):387–392. doi: 10.1038/nn.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jensen MØ, et al. Mechanism of voltage gating in potassium channels. Science. 2012;336(6078):229–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1216533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cha A, Bezanilla F. Characterizing voltage-dependent conformational changes in the Shaker K+ channel with fluorescence. Neuron. 1997;19(5):1127–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang N, George AL, Jr, Horn R. Molecular basis of charge movement in voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 1996;16(1):113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manor J, et al. Gating mechanism of the influenza A M2 channel revealed by 1D and 2D IR spectroscopies. Structure. 2009;17(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.daCosta CJ, Dey L, Therien JP, Baenziger JE. A distinct mechanism for activating uncoupled nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(11):701–707. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng Q, Du M, Ramanoudjame G, Jayaraman V. Evolution of glutamate interactions during binding to a glutamate receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1(6):329–332. doi: 10.1038/nchembio738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Venyaminov SYu, Kalnin NN. Quantitative IR spectrophotometry of peptide compounds in water (H2O) solutions. I. Spectral parameters of amino acid residue absorption bands. Biopolymers. 1990;30(13-14):1243–1257. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmerberg J, Bezanilla F, Parsegian VA. Solute inaccessible aqueous volume changes during opening of the potassium channel of the squid giant axon. Biophys J. 1990;57(5):1049–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82623-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dencher NA, Dresselhaus D, Zaccai G, Büldt G. Structural changes in bacteriorhodopsin during proton translocation revealed by neutron diffraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(20):7876–7879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frauenfelder H, et al. A unified model of protein dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(13):5129–5134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900336106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, Heberle J. Proton transfer and protein conformation dynamics in photosensitive proteins by time-resolved step-scan Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. J Vis Exp. 2014;88(88):e51622. doi: 10.3791/51622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lórenz-Fonfría VA, Kandori H, Padrós E. Probing specific molecular processes and intermediates by time-resolved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: Application to the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115(24):7972–7985. doi: 10.1021/jp201739w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gull SF, Skilling J. Quantified Maximum Entropy MemSys5 User’s Manual. Maximum Entropy Data Consultants Ltd; Suffolk, England: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moll A, Hildebrandt A, Lenhof HP, Kohlbacher O. BALLView: A tool for research and education in molecular modeling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(3):365–366. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]