Significance

The southward displacement of the East Asian monsoon rain belt heightens concerns over the warming-induced drying of northern China. Paleovegetation change on the Chinese Loess Plateau provides insights into future climate changes. We find that the spatial distribution of C4 plant biomass is a robust analog for the monsoon rain belt, which migrated at least 300 km to the northwest from the cold Last Glacial Maximum (∼19 ka) to the warm Holocene (∼4 ka). These results strongly support the idea that the Earth's thermal equator will move northward in a warmer world, and that the observed southward migration of the monsoon rain belt over the last few decades is transient and northern China will eventually become wet as global warming advances.

Keywords: C4 plants, loess, East Asian summer monsoon, Last Glacial Maximum, Holocene

Abstract

Glacial–interglacial changes in the distribution of C3/C4 vegetation on the Chinese Loess Plateau have been related to East Asian summer monsoon intensity and position, and could provide insights into future changes caused by global warming. Here, we present δ13C records of bulk organic matter since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) from 21 loess sections across the Loess Plateau. The δ13C values (range: –25‰ to –16‰) increased gradually both from the LGM to the mid-Holocene in each section and from northwest to southeast in each time interval. During the LGM, C4 biomass increased from <5% in the northwest to 10–20% in the southeast, while during the mid-Holocene C4 vegetation increased throughout the Plateau, with estimated biomass increasing from 10% to 20% in the northwest to >40% in the southeast. The spatial pattern of C4 biomass in both the LGM and the mid-Holocene closely resembles that of modern warm-season precipitation, and thus can serve as a robust analog for the contemporary East Asian summer monsoon rain belt. Using the 10–20% isolines for C4 biomass in the cold LGM as a reference, we derived a minimum 300-km northwestward migration of the monsoon rain belt for the warm Holocene. Our results strongly support the prediction that Earth's thermal equator will move northward in a warmer world. The southward displacement of the monsoon rain belt and the drying trend observed during the last few decades in northern China will soon reverse as global warming continues.

The East Asian summer monsoon plays a crucial role in interhemispheric heat and moisture transport and serves as the main moisture supply for East Asia (1). In recent years, the impact of global warming on the East Asian monsoon has been the subject of intense investigation (2), because even a minor change in monsoon intensity can have a profound effect on the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Several authors (3) argue that meridional asymmetries caused by prominent warming between 45° N and 60° N, compared with the tropics, induces a weakened meridional thermal contrast over eastern Asia and may explain the southward shift in the monsoon rainfall belt (4–7), with more droughts in northern China countered by more floods in southern China, as observed since the 1970s. This is consistent with the prediction of Held and Soden (8) that Earth's dry regions will become drier, and its wet regions wetter, with global warming. Broecker and Putnam (9), however, argue that an increased interhemispheric temperature contrast would tend to shift the thermal equator northward in a warmer world, instead leading to a northward shift in the East Asian summer monsoon rainfall belt and increased precipitation in northern China. It remains unclear whether the recent drying is transient, and linked to El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) or other large-scale variability, or if it signals the start of a long-term drying trend induced by global warming.

The Chinese Loess Plateau is located in the marginal zone of the summer monsoon and is characterized by a steep climatic gradient, where the spatiotemporal change of C3/C4 vegetation is closely related to the summer monsoon intensity (10–17). The warming interval from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the Holocene offers a useful test for future hydroclimatic changes (18). Consequently, we examined spatial changes in C4 plant biomass for the LGM and Holocene based on δ13C records of bulk organic matter across the Loess Plateau, with the aim of estimating the shift of the monsoon rain belt associated with past global warming as well as predicting future hydroclimatic trends.

Spatial Changes in C4 Plant Abundance During the LGM and Holocene

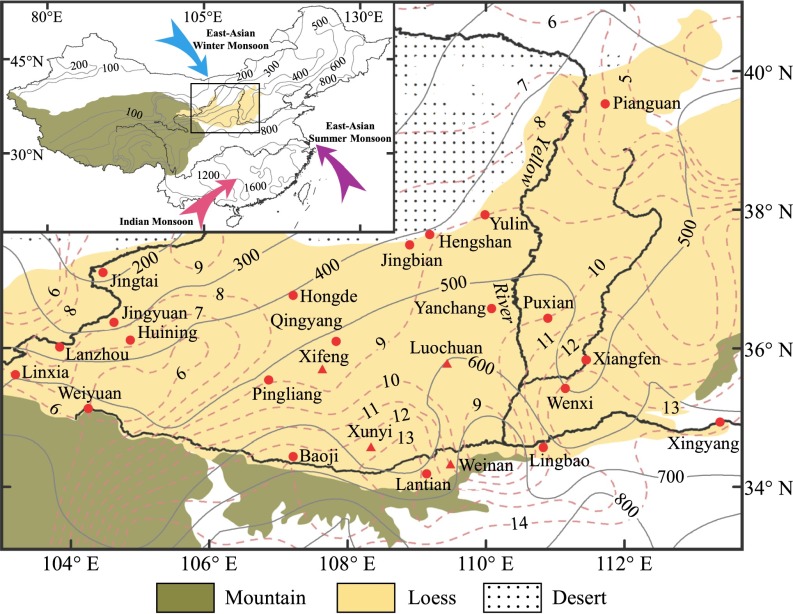

The modern climate of East Asia is characterized by seasonal alternations of a wet, warm summer monsoon and a dry, cold winter monsoon (Fig. 1). In the Chinese Loess Plateau, mean annual temperature increases from ∼7 to ∼13 °C, and mean annual precipitation from ∼250 to ∼600 mm, from northwest to southeast (Fig. 1), with ∼60–80% of the precipitation concentrated in the summer season. Across these large gradients on the Loess Plateau, the alternation of loess (L) and soils (S) documents large-scale oscillations between glacial and interglacial conditions (19–21). We logged and sampled 21 sections (Fig. 1) to characterize late Quaternary changes in C3/C4 vegetation as a proxy for the intensity and position of the East Asian Monsoon rain belt across the Loess Plateau.

Fig. 1.

Chinese Loess Plateau, prevailing monsoon circulation, and modern climatic gradients. Solid circles show locations of 21 sites investigated in this study, and solid triangles denote locations of 4 additional sites previously studied by Liu et al. (14). Arrows in Inset map indicate the direction of the winter and summer monsoonal winds. The isohyets (in millimeters; gray lines) and isotherms (in degrees Celsius; dashed lines) are values averaged over 51 y (1951–2001).

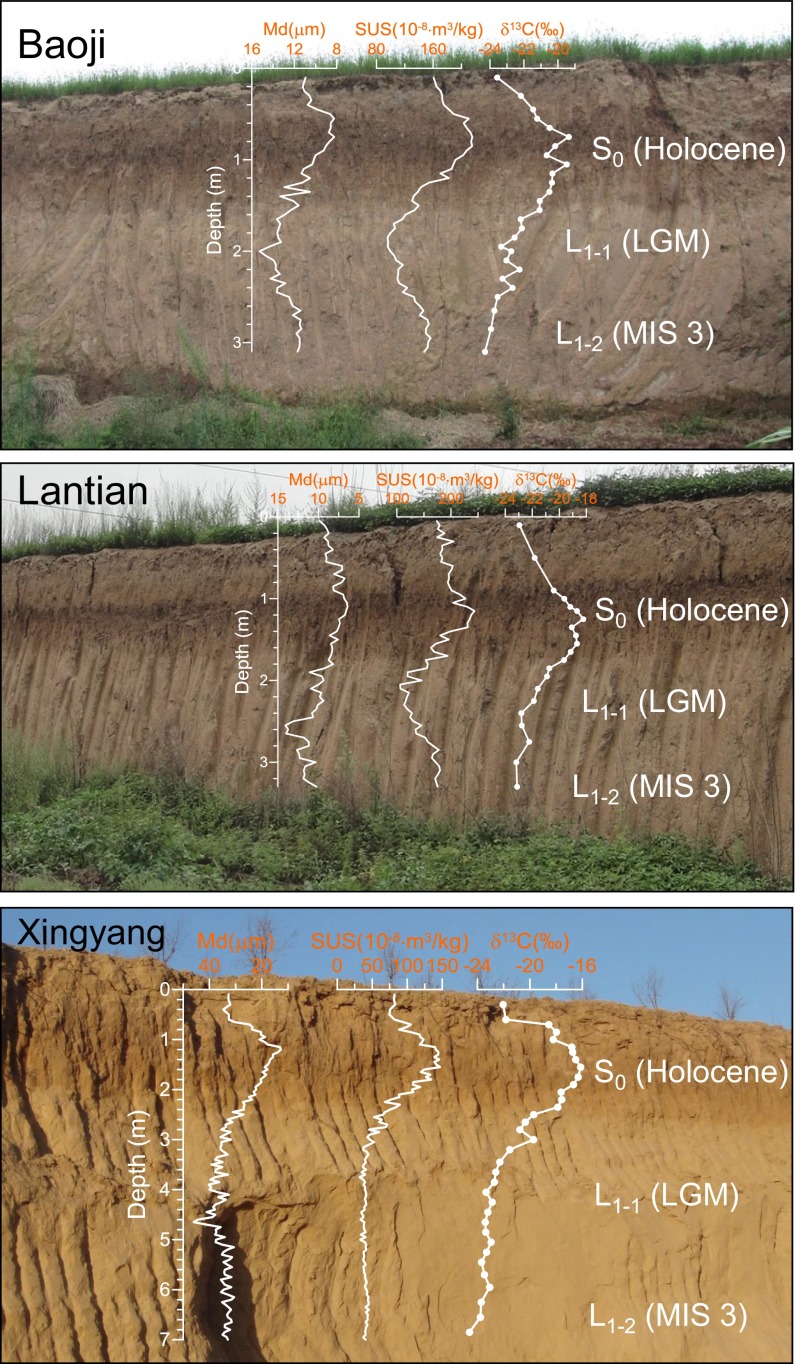

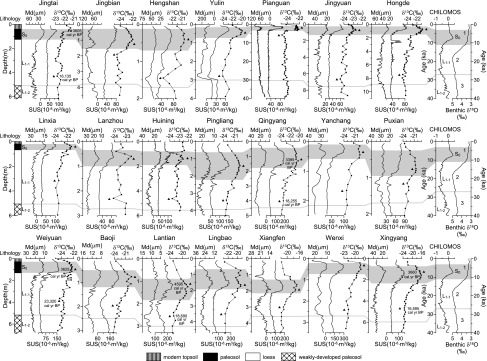

All sections consist of soil unit S0 and the upper part of loess unit L1 (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). The Holocene soil (S0), overlain by modern topsoil, is dark in color because of its relatively high organic matter content. Loess unit L1, yellowish in color and massive in structure, was deposited during the last glacial period. L1 can generally be divided into five subunits termed L1-1, L1-2, L1-3, L1-4, and L1-5 (22, 24). L1-2 and L1-4 are weakly developed soils, and the other subunits are typical loess horizons. Previous studies (19, 20, 22, 25) demonstrate that (i) L1-1 was deposited in marine isotope stage (MIS) 2 (∼27–11 ka), which includes the LGM (∼26.5–19 ka) (26); (ii) S0 was deposited in the early-mid–Holocene (∼11–3 ka), which includes the Holocene Thermal Maximum (HTM) (∼11–5 ka) (27); and (iii) L1-2 was deposited in late MIS 3 (∼38–27 ka). To ensure that we used a complete cold–warm cycle for C3/C4 vegetation reconstruction, almost all of the sections were sampled down to loess unit L1-2.

Fig. 2.

Stratigraphic column, median grain size (Md), magnetic susceptibility (SUS), and δ13C of bulk organic matter for the 21 loess sections (Fig. 1) across the Chinese Loess Plateau, and correlation with a stacked Chinese loess grain-size record [Chinese Loess Millennial-Scale Oscillation Stack (CHILOMOS) (22)] and a stacked benthic δ18O record (23). The stratigraphic positions of the selected samples used in Figs. 4 and 5 are indicated by solid triangles in each section. Median calibrated radiocarbon ages of the bulk organic fraction for 10 of those selected samples are labeled beside the triangles. Marine isotope stages (MIS) 1–3 are labeled. The shaded zones indicate the Holocene soil (S0). The gray lines indicate the top of MIS 3 (L1-2).

Fig. S1.

Correlation of lithostratigraphy, median grain size (Md), magnetic susceptibility (SUS), and δ13C of bulk organic matter between the Baoji, Lantian, and Xingyang sections. Note (i) the stratigraphic contrast between soil unit S0 (Holocene) and loess unit L1-1 [Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)] in each section, and (ii) the similarity in the structure of Md, SUS, and δ13C curves.

In general, soil units S0 (Holocene) and L1-2 (late MIS 3) are characterized by higher magnetic susceptibility values and finer grain sizes compared with the LGM loess unit L1-1, and there is a strong similarity in the structure of the grain size and magnetic susceptibility curves between the different loess sections (Fig. 2). The correlation of lithostratigraphy, grain size, and magnetic susceptibility (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1) between sections demonstrates the remarkable stratigraphic and spatial continuity of the loess deposits at orbital or even millennial timescales.

δ13C Contour Maps.

Plants use two principal biosynthetic pathways to fix carbon, C3 and C4, which have distinct carbon isotope signatures (28, 29). Modern surveys (30) demonstrate that, in the loess region of northern China, C3 plants have δ13C values ranging from –21.7‰ to –30‰ with a mean of –26.7‰; and that C4 plants have δ13C values ranging from –10‰ to –15.8‰ with a mean of –12.8‰. In all of the sections, the δ13C values of soil organic matter fall within the range of –25‰ to –21‰ for the LGM loess unit and within the range of –23‰ to –16‰ for the Holocene soil. From the LGM to the Holocene, the δ13C values increased consistently at each site (Fig. 2) and they exhibit a good correlation with the grain size and magnetic susceptibility records. Given that the L1-1 loess unit has a low organic matter content (<0.5%) (31), the effects of percolation of soluble organic substances (32) and soil texture (33, 34) on the observed glacial–interglacial δ13C pattern (Fig. 2) need to be carefully evaluated before definitively linking the δ13C records to C3/C4 vegetation change.

Radiocarbon (14C) measurements of bulk organic matter and humin fractions from five sections yielded ages of 4595−3395 cal y B.P. and 4730−3860 cal y B.P., respectively, for the finest-grained part of S0, and 23,320−16,135 cal y B.P. and 23,930−16,370 cal y B.P., respectively, for the coarsest part of L1-1 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The radiocarbon ages of S0 and L1-1 overlap with or are slightly younger than the dates of HTM (∼11–5 ka) and LGM (∼26.5–19 ka), respectively. Because measured 14C ages of soil organic matter are always younger than the true age of deposition, due to addition of younger organic matter through rootlet penetration, bioturbation, and percolation of soluble organic substances (32, 35), our radiocarbon dates are compatible with the widely accepted assumption that the coarsest interval of L1-1 represents the coldest interval of the LGM, whereas the finest interval of S0 represents the warmest interval in the Holocene (22, 24).

Table 1.

Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon ages for bulk organic and humin fractions from five sections across the Chinese Loess Plateau

| Section | Unit | Depth, m | Soil fraction | 14C age, y B.P. | 2σ cal age, y B.P. | Median cal age, y B.P. | Beta no. |

| Jingtai | S0 | 0.55 | Bulk sediment | 3360 ± 30 | 3650‒3555 | 3605 | 417149 |

| Humin | 3570 ± 30 | 3935‒3825 | 3870 | 414142 | |||

| L1-1 | 4.30 | Bulk sediment | 13,410 ± 40 | 16,295‒15,960 | 16,135 | 414501 | |

| Humin | 19,880 ± 60 | 24,140‒23,700 | 23,930 | 414502 | |||

| Weiyuan | S0 | 0.95 | Bulk sediment | 3380 ± 30 | 3695‒3565 | 3625 | 414153 |

| Humin | 4190 ± 30 | 4765‒4620 | 4730 | 414154 | |||

| L1-1 | 4.05 | Bulk sediment | 19,370 ± 60 | 23,570‒23,060 | 23,320 | 414155 | |

| Humin | 16,990 ± 60 | 20,680‒20,280 | 20,490 | 414156 | |||

| Qingyang | S0 | 1.25 | Bulk sediment | 3170 ± 30 | 3450‒3345 | 3395 | 417151 |

| Humin | 3690 ± 30 | 4095‒3960 | 4035 | 414146 | |||

| L1-1 | 4.00 | Bulk sediment | 15,020 ± 40 | 18,405‒18,070 | 18,255 | 414503 | |

| Humin | 17,470 ± 50 | 21,315‒20,880 | 21,095 | 414504 | |||

| Lantian | S0 | 1.15 | Bulk sediment | 4090 ± 30 | 4650‒4515 | 4595 | 414157 |

| Humin | 3750 ± 30 | 4160‒4065 | 4115 | 415474 | |||

| L1-1 | 2.65 | Bulk sediment | 15,420 ± 50 | 18,805‒18,565 | 18,690 | 414158 | |

| Humin | 13,590 ± 40 | 16,580‒16,195 | 16,370 | 415475 | |||

| Xingyang | S0 | 1.25 | Bulk sediment | 3410 ± 30 | 3720‒3575 | 3660 | 417150 |

| Humin | 3560 ± 30 | 3930‒3820 | 3860 | 415476 | |||

| L1-1 | 4.65 | Bulk sediment | 13,740 ± 40 | 16,835‒16,365 | 16,595 | 414160 | |

| Humin | 13,890 ± 50 | 17,045‒16,580 | 16,830 | 415477 |

At each site, the samples dated were selected from the finest-grained part of the Holocene soil (S0) and the coarsest part of the LGM loess unit (L1-1). The stratigraphic positions of the samples are indicated in Fig. 2. The radiocarbon dates yield an average of ∼3775 cal y B.P. (bulk sediment) and ∼4120 cal y B.P. (humin) for S0, and ∼18,600 cal y B.P. (bulk sediment) and ∼19,740 cal y B.P. (humin) for L1-1.

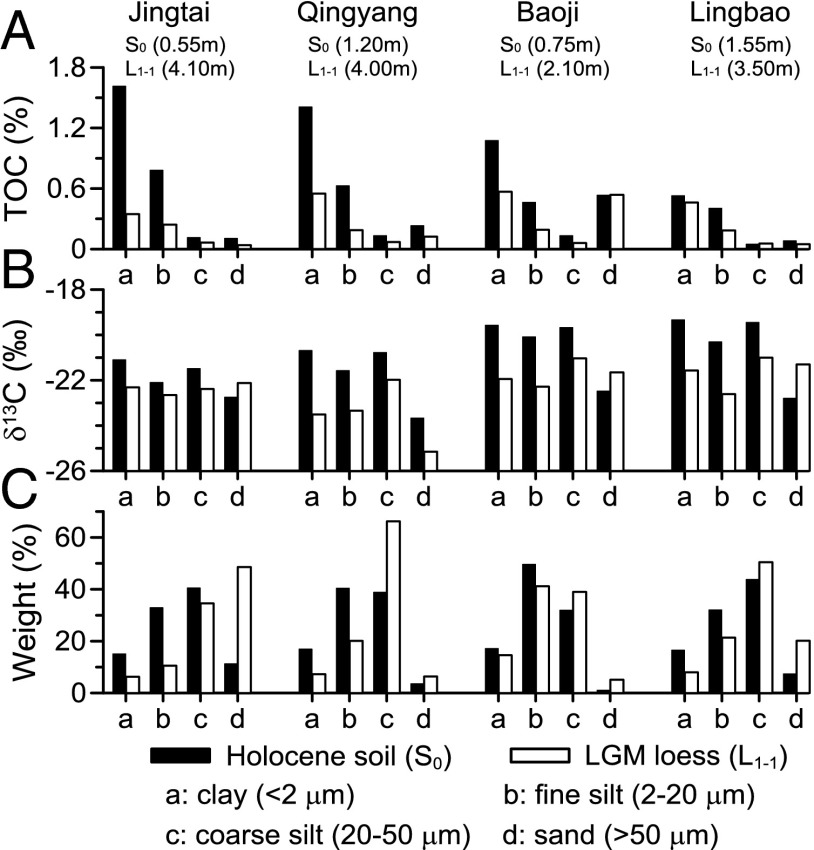

It should be noted that the 14C ages of bulk organic matter for most samples, especially those from S0, are ∼15% younger on average compared with the ages obtained from the humin fraction (the stable and insoluble fraction of soil humic substances), indicating a moderate contamination by younger soluble organic substances. However, an average age difference of ∼15 ka between S0 (average, ∼4 ka) and L1-1 (average, ∼19 ka), as indicated by the dates for both bulk organic carbon and more stable humin fractions (Table 1), demonstrates a negligible effect of translocation of organic matter from S0 into the underlying L1-1. This may result from the fact that Chinese loess has a strong adsorption capacity due to the large clay (<2 μm)−silt (2−50 μm) fraction (>50%; Fig. 3C), which minimizes the potential for contamination by percolation of soluble organic substances (36, 37).

Fig. 3.

Total organic carbon (TOC) content (A), δ13C of soil organic matter (B), and weight percentage data (C) for different size fractions in loess (L1-1) and soil (S0) samples. TOC and weight percentage were measured on a carbonate-free basis.

Size fractionation results show that (i) soil organic matter is mainly concentrated in clay (<2 μm) and fine silt (2−20 μm) fractions (Fig. 3A), and (ii) δ13C values fluctuate without significant size dependence across the observed size range (Fig. 3B), except for the relatively low δ13C values for the sand fraction of the Holocene soil samples. However, the effect of this fraction on the δ13C of bulk samples is very limited due to the low content of both the sand fraction (Fig. 3C) and its associated organic matter (Fig. 3A). In addition, the δ13C value of a specific size fraction in L1-1 is generally lower than its counterpart in S0 (Fig. 3B), exhibiting the same pattern as observed for the bulk δ13C record (Fig. 2). In this context, the glacial–interglacial δ13C pattern (Fig. 2) faithfully mirrors C3/C4 vegetation change.

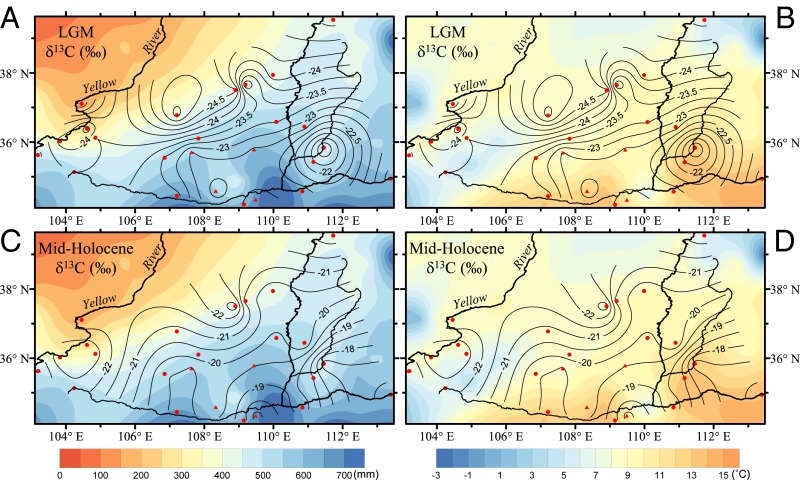

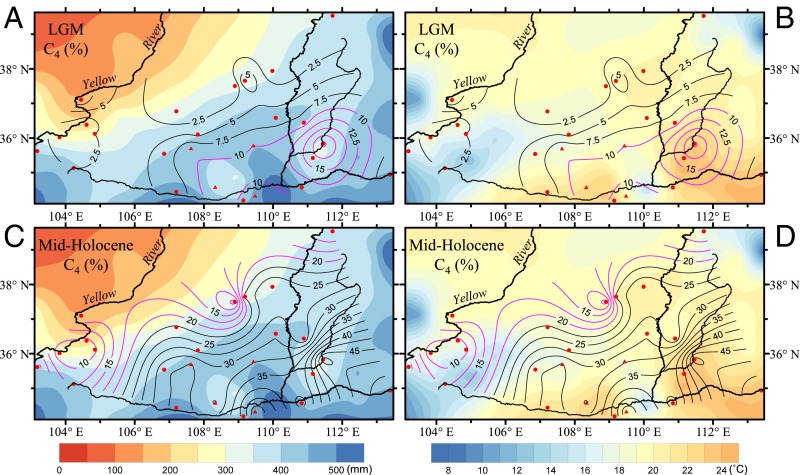

To plot the δ13C contour maps, we selected the δ13C value of a sample from within the interval of coarsest grain size of L1-1 for the LGM, and that of a sample from within the interval of finest grain size of S0 for the mid-Holocene. The δ13C contour maps were constructed using the kriging algorithm in the Surfer software package. The δ13C isolines exhibit a northeast–southwest trend in both the LGM and the mid-Holocene (Fig. 4), which is generally consistent with the present-day climatic pattern, i.e., a northeast–southwest trend for both the modern annual isohyets (Fig. 4 A and C) and isotherms (Fig. 4 B and D). From northwest to southeast, the δ13C values increase from –24‰ to –22‰ during the LGM and from –22.5‰ to –17.5‰ during the mid-Holocene.

Fig. 4.

δ13C (‰) contour maps for the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (A and B) and the mid-Holocene (C and D), together with modern mean annual precipitation (A and C) and temperature (B and D) over 51 y (1951–2001). The contour maps were constructed using δ13C data from the 21 sites in this study (solid circles; Figs. 1 and 2) and four additional sites in Liu et al. (14) (solid triangles; Fig. 1). All of the δ13C data used in this paper were obtained from the same laboratory by identical methods, thereby minimizing interlaboratory variability.

C4 Abundance Contour Maps.

To estimate the C3/C4 biomass, it is crucial to determine end-member δ13C values for C3 and C4 plants in the LGM and mid-Holocene. In so doing, we considered the effects of the δ13C of atmospheric CO2 (δ13Catm), precipitation, and temperature change on the δ13C values of C3 and C4 plants (Table S1). However, we ignored the effect of changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration because the relationship between CO2 concentration and δ13C of C3 plants on the Loess Plateau is unknown. After correcting for these factors, and for organic matter degradation, the end-member δ13C values of soil organic matter for C3 (δ13CC3) and C4 plants (δ13CC4) were obtained for the LGM and mid-Holocene (Table S1). C4 plant abundance was estimated by applying the measured δ13C values to an isotope mass-balance equation: C4(%) = [(δ13C – δ13CC3)/(δ13CC4 – δ13CC3)] × 100.

Table S1.

Calculation of end-member δ13C values of soil organic matter for C3 (δ13CC3) and C4 vegetation (δ13CC4) for the mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)

| Factor | δ13CC3, ‰ | δ13CC4, ‰ | Calculation basis and data sources |

| Mid-Holocene* | |||

| Today's vegetation | −26.7 | −12.8 | Ref. 30 |

| δ13Catm correction (+1.7‰) | −25.0 | −11.1 | δ13C of atmospheric CO2: −8.06‰ for the present (Mauna Loa Observatory, 2000; ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/co2c13/flask/surface/co2c13_mlo_surface-flask_1_sil_month.txt); −6.33‰ for the mid-Holocene (53) |

| Degradation correction (+1.0‰) | −24.0 | −10.1 | Refs. 17 and 54 |

| LGM | |||

| Today's vegetation | −26.7 | −12.8 | Ref. 30 |

| δ13Catm correction (+1.6‰) | −25.1 | −11.2 | δ13C of atmospheric CO2: −8.06‰ for the present (Mauna Loa Observatory, 2000; ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/co2c13/flask/surface/co2c13_mlo_surface-flask_1_sil_month.txt); −6.46‰ for the LGM (53) |

| Precipitation correction (C3: +0.6‰) | −24.5 | −11.2 | ∼150 mm lower in the LGM than at the present (55, 56); −0.40‰/100 mm for C3 plants and a negligible coefficient for C4 plants (30) |

| Temperature correction (C3: −0.6‰) | −25.1 | −11.2 | 6 °C lower in the LGM than at the present (56); 0.104‰/°C for C3 plants and no significant correlation for C4 plants (57) |

| Degradation effect (+1.0‰) | −24.1 | −10.2 | Refs. 17 and 54 |

The climatic conditions in the mid-Holocene are assumed to be similar to the present, and thus the precipitation and temperature corrections for the mid-Holocene are ignored.

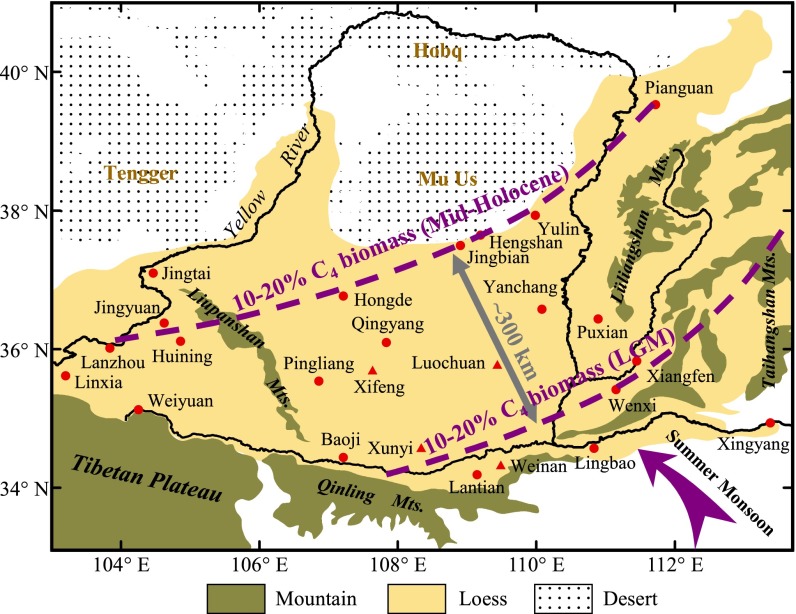

The LGM and mid-Holocene share two common features in the C4 biomass contour maps (Fig. 5). First, the isolines of C4 biomass exhibit a northeast–southwest zonal distribution pattern. Second, C4 biomass increases consistently from northwest to southeast. These similarities demonstrate that the C4 abundance in both the LGM and mid-Holocene was controlled by the same environmental factor(s). However, two differences between the two time intervals are noteworthy. First, C4 vegetation increased considerably throughout the Loess Plateau in the mid-Holocene compared with the LGM, with an increase of ∼15% in the northwest and ∼25% in the southeast. Second, a greater spatial change in C4 biomass is evident in the mid-Holocene (from 10% to 20% in the northwest to >40% in the southeast) than in the LGM (from <5% in the northwest to 10–20% in the southeast). These differences indicate that the environmental factor(s) controlling C4 abundance varied considerably between the LGM and Holocene.

Fig. 5.

Contour maps of estimated C4 biomass (%) for the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (A and B) and the mid-Holocene (C and D), together with modern mean warm-season precipitation (A and C) and temperature (B and D) (May to September) over 51 y (1951–2001). The C4 biomass was calculated using δ13C data from the 21 sites in this study (solid circles; Figs. 1 and 2) and four additional sites in Liu et al. (14) (solid triangles; Fig. 1). Note the migration of the 10–20% isolines for C4 biomass (pink lines) between the LGM and the mid-Holocene.

Factors Controlling C4 Abundance on the Loess Plateau.

Plant biogeographical studies have shown that lower atmospheric pCO2, higher growing season temperature, and enhanced summer precipitation favor C4 over C3 plants (38). Given that atmospheric CO2 concentrations rose from ∼180 ppmv in the LGM to ∼260 ppmv in the mid-Holocene (39), the significant increase in C4 abundance during this interval (Figs. 2 and 5) cannot be explained by pCO2 change. On the Chinese Loess Plateau, both growing season temperature and precipitation are higher in the southeast than in the northwest (Fig. 5), all favoring increased C4 vegetation in the southeast. However, the relative importance of temperature and precipitation for C4 vegetation cannot be disentangled due to the seasonal synchrony of rainfall and temperature in the East Asian monsoon region (Fig. 5). Because warm-season precipitation is a defining feature of the summer monsoon circulation (16), it is clear that the northeast–southwest zonal distribution pattern of C4 biomass on the Loess Plateau can serve as a robust analog for the East Asian summer monsoon rain belt.

Migration of the East Asian Summer Monsoon Rain Belt from the LGM to the Mid-Holocene

The similarities in the spatial pattern of C4 abundance between the LGM and mid-Holocene (Fig. 5) demonstrate a similar pattern of the summer monsoon rain belt during the two time intervals, i.e., a northeast–southwest trend for the monsoon isohyets through the recent cold–warm cycle. It is especially striking that the C4 percentage isolines of a specific value exhibit a significant northwest–southeast migration between the LGM and mid-Holocene (Fig. 5). For example, the 10–20% isolines for C4 biomass in the southeastern part of the Plateau during the LGM moved to the northwestern part during the mid-Holocene, indicating a major northwestward advance of the summer monsoon rain belt from the LGM to the mid-Holocene. Using the plot of 10–20% C4 biomass as a reference (Fig. 6), we estimate a northwesterly monsoon rain belt advance of ∼300 km for the warm Holocene compared with the cold LGM.

Fig. 6.

Migration of the East Asian summer monsoon rain belt (purple dashed lines) between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and the mid-Holocene as reconstructed using the 10–20% isolines for C4 biomass shown in Fig. 5.

It should be noted that the decline of atmospheric CO2 level in the LGM would have caused increased δ13C values of C3 plants, because modern observations (40, 41) reveal a wide range of coefficients, from −0.019‰/100 ppmv to −2.7‰/100 ppmv, depending on targeted species and CO2 concentrations. In view of an ∼80-ppmv increase in atmospheric CO2 levels in the mid-Holocene relative to the LGM (39), the end-member δ13C of C3 plants for the LGM should be higher than that used for the calculation of C4 biomass (Table S1). Thus, the C4 percentages estimated for the LGM (Fig. 5 A and B) should be regarded as upper limits. With regard to the mid-Holocene (S0), the C4 biomass may be overestimated because the microbial effect on 13C enrichment appears to be more pronounced for C3- than for C4-derived organic matter (42, 43). However, this effect may be counterbalanced by the addition of modern organic matter, characterized by relatively low δ13C values, to S0 (Fig. 2), which is indicated by the young 14C ages obtained from both the bulk organic and humin fractions (Table 1). In this context, the estimated ∼300-km rain belt advance can be regarded as a minimum for the mid-Holocene (Fig. 6).

Paleotemperature reconstructions demonstrate that from the LGM to the Holocene (preindustrial), global mean sea surface temperature increased by 0.7–2.7 °C (44, 45), whereas global mean surface air temperature increased by as much as 3–8 °C (45), indicating a greater warming over land areas than over oceans. Our results demonstrate a northwestward advance of the East Asian summer monsoon rain belt from the cold LGM to the warm Holocene. This may be explained by the following physical process: the decay of continental ice in the Northern Hemisphere by the HTM, as well as the vast continent itself (warming more rapidly than the oceans), caused a northward shift of Earth's thermal equator, thus driving the northward migration of the Asian monsoon rain belt (9). An additional process could be the rise of global sea level in the Holocene, which led to a northwesterly transgression of the Western Pacific marginal seas (46), thereby facilitating the northwestward penetration of the monsoon rain belt.

Our study strongly supports the prediction of Broecker and Putnam (9) that monsoonal Asia will become wetter in a warmer world. The observed drying trend in northern China since the 1970s is likely to be caused by increased winter and spring snow ice cover in the Tibetan Plateau (47) and by an ENSO-like mode of sea surface temperature (48). In this context, northern China is expected eventually to become wet as global warming continues.

Materials and Methods

A total of 2,383 samples were collected at a 5-cm interval. For stratigraphic correlation, grain size and bulk magnetic susceptibility were measured on all samples using a SALD-3001 laser diffraction particle analyzer and a Bartington Instruments MS2 magnetic susceptibility meter. The grain-size analytical procedures were as detailed by Ding et al. (49).

A total of 590 samples were selected for δ13C analysis of bulk organic matter. Sample splits (∼2 g) were first screened for modern rootlets and then digested for 24 h in 1 M HCl at room temperature to remove inorganic carbonate. The samples were then washed to pH >4 with distilled water and dried cryogenically at −80 °C. The dried samples (∼500 mg) were combusted for over 4 h at 850 °C in evacuated sealed quartz tubes in the presence of 1 g of Cu, 1 g of CuO, and a Pt wire. The CO2 was purified and isolated by cryogenic distillation for isotopic analysis. Carbon isotopic composition of CO2 was then determined using a MAT-251 gas mass spectrometer at the Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). The δ13C results are reported in per mil units (‰) relative to Vienna Peedee belemnite (VPDB) standard with an error of less than 0.2‰.

Ten samples were selected from S0 and L1-1 at five widely separated sites for the measurement of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C ages for both bulk organic carbon (acid wash treatment) and humin (acid–alkali–acid treatment) fractions. All samples were pretreated and analyzed by Beta Analytic. Calibration of 14C dates was done in Calib Rev 7.0.4 (calib.qub.ac.uk/calib/calib.html) (50) using the IntCal13 curve (51).

Eight samples from the L1-1−S0 couplet at four sites were separated into sand (>50 μm), coarse silt (20−50 μm), fine silt (2−20 μm), and clay (<2 μm) fractions according to standard sieving and pipette methods (52). Bulk samples (20−30 g) were first screened for modern rootlets and decarbonated as described above, and then dispersed in 300 mL of distilled water with 10 mL of 0.05 M (NaPO3)6 and treated ultrasonically. The sand (>50 μm) fraction was separated by wet sieving, and the resulting <50-μm suspension was separated into 20- to 50-μm, 2- to 20-μm, and <2-μm fractions by gravity sedimentation (52). Particle size separates were then freeze-dried, weighed to obtain a mass for each fraction, ground, and analyzed to determine δ13C and total organic carbon (TOC) content. TOC content of the samples (200 mg for each) were measured by high-temperature combustion (950 °C) using an Elementar rapid CS CUBE.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Zhou, S. H. Feng, X. X. Yang, Z. L. Chen, S. J. Zhao, W. G. Liu, J. W. Fan, and L. C. Guo for field and laboratory assistance, and J. L. Betancourt, J. T. Han, G. A. Wang, Z. Y. Gu, and J. L. Xiao for valuable discussions and suggestions. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which greatly improved the manuscript. This study was supported by Chinese Academy of Sciences Grants XDA05120204 and XDB03020503, and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 41172157 and 41472318.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1504688112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Webster PJ, et al. Monsoons: Processes, predictability, and the prospects for prediction. J Geophys Res. 1998;103(C7):14451–14510. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Stocker TF, et al., editors. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Wu Z, Jiang Z, He J. Can global warming strengthen the East Asian summer monsoon? J Clim. 2010;23(24):6696–6705. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H. The weakening of the Asian monsoon circulation after the end of 1970’s. Adv Atmos Sci. 2001;18(3):376–386. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chase TN, Knaff JA, Pielke RA, Kalnay E. Changes in global monsoon circulations since 1950. Nat Hazards. 2003;29(2):229–254. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding Y, Wang Z, Sun Y. Inter-decadal variation of the summer precipitation in East China and its association with decreasing Asian summer monsoon. Part I: Observed evidences. Int J Climatol. 2008;28(9):1139–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai XG, Wang P, Zhang KJ. A decomposition study of moisture transport divergence for inter-decadal change in East Asia summer rainfall during 1958–2001. Chin Phys B. 2012;21(11):119201. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Held IM, Soden BJ. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J Clim. 2006;19(21):5686–5699. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broecker WS, Putnam AE. Hydrologic impacts of past shifts of Earth’s thermal equator offer insight into those to be produced by fossil fuel CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):16710–16715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301855110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu Z, et al. Climate as the dominant control on C3 and C4 plant abundance in the Loess Plateau: Organic carbon isotope evidence from the last glacial-interglacial loess-soil sequences. Chin Sci Bull. 2003;48(12):1271–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Zhao M, Lu H, Faiia AM. Lower temperature as the main cause of C4 plant declines during the glacial periods on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2003;214(3-4):467–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidic NJ, Montañez IP. Climatically driven glacial-interglacial variations in C3 and C4 plant proportions on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Geology. 2004;32(4):337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 13.An Z, et al. Multiple expansions of C4 plant biomass in East Asia since 7 Ma coupled with strengthened monsoon circulation. Geology. 2005;33(9):705–708. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, et al. Summer monsoon intensity controls C4/C3 plant abundance during the last 35 ka in the Chinese Loess Plateau: Carbon isotope evidence from bulk organic matter and individual leaf waxes. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2005;220(3-4):243–254. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao Z, Wu H, Liang M, Shi X. Spatial and temporal variations in C3 and C4 plant abundance over the Chinese Loess Plateau since the last glacial maximum. J Arid Environ. 2011;75(10):881–889. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Ding Z, Wang X, Tang Z, Gu Z. Negative δ18O-δ13C relationship of pedogenic carbonate from northern China indicates a strong response of C3/C4 biomass to the seasonality of Asian monsoon precipitation. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2012;317-318:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao Z, et al. High-resolution summer precipitation variations in the western Chinese Loess Plateau during the last glacial. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2785. doi: 10.1038/srep02785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quade J, Broecker WS. Dryland hydrology in a warmer world: Lessons from the Last Glacial period. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2009;176(1):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kukla G. Loess stratigraphy in central China. Quat Sci Rev. 1987;6(3-4):191–219. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding ZL, et al. Stacked 2.6-Ma grain size record from the Chinese loess based on five sections and correlation with the deep-sea δ18O record. Paleoceanography. 2002;17(3):1033. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang S, Ding Z. Drastic climatic shift at ∼2.8 Ma as recorded in eolian deposits of China and its implications for redefining the Pliocene–Pleistocene boundary. Quat Int. 2010;219(1-2):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S, Ding Z. A 249 kyr stack of eight loess grain size records from northern China documenting millennial-scale climate variability. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2014;15(3):798–814. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lisiecki LE, Raymo ME. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography. 2005;20(1):PA1003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang S, Ding Z. Advance-retreat history of the East-Asian summer monsoon rainfall belt over northern China during the last two glacial-interglacial cycles. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;274(3-4):499–510. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YC, Wang XL, Wintle AG. A new OSL chronology for dust accumulation in the last 130,000 yr for the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat Res. 2007;67(1):152–160. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark PU, et al. The Last Glacial Maximum. Science. 2009;325(5941):710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.1172873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renssen H, Seppä H, Crosta X, Goosse H, Roche DM. Global characterization of the Holocene Thermal Maximum. Quat Sci Rev. 2012;48:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deines P. The isotopic composition of reduced organic carbon. In: Fritz P, Fontes JC, editors. Handbook of Environmental Isotope Geochemistry I, The Terrestrial Environment. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1980. pp. 329–406. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Leary MH. Carbon isotopes in photosynthesis. Bioscience. 1988;38(5):328–336. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang G, et al. Paleovegetation reconstruction using δ13C of soil organic matter. Biogeosciences. 2008;5(5):1325–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J, Liu T. Multiple origins and interpretations of the magnetic susceptibility signal in Chinese wind-blown sediments. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2000;180(3-4):287–296. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geyh MA, Roeschmann G, Wijmstra TA, Middeldorp AA. The unreliability of 14C dates obtained from buried sandy Podzols. Radiocarbon. 1983;25(2):409–416. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desjardins T, Andreux F, Volkoff B, Cerri CC. Organic carbon and 13C contents in soils and soil size-fractions, and their changes due to deforestation and pasture installation in eastern Amazonia. Geoderma. 1994;61(1-2):103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telles ECC, et al. Influence of soil texture on carbon dynamics and storage potential in tropical forest soils of Amazonia. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2003;17(2):1040. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Amundson R, Trumbore S. Radiocarbon dating of soil organic matter. Quat Res. 1996;45(3):282–288. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei XR, Shao MA. The transport of humic acid in soils. China Environ Sci. 2007;27(3):336–340. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plante AF, Conant RT, Stewart CE, Paustian K, Six J. Impact of soil texture on the distribution of soil organic matter in physical and chemical fractions. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2006;70(1):287–296. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sage RF, Wedin DA, Li M. The biogeography of C4 photosynthesis: Patterns and controlling factors. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 Plant Biology. Academic; San Diego: 1999. pp. 313–373. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lüthi D, et al. High-resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650,000–800,000 years before present. Nature. 2008;453(7193):379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Feng X. Response of plants’ water use efficiency to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(16):8610–8620. doi: 10.1021/es301323m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schubert BA, Jahren AH. The effect of atmospheric CO2 concentration on carbon isotope fractionation in C3 land plants. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2012;96:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natelhoffer KJ, Fry B. Controls on natural nitrogen-15 and carbon-13 abundances in forest soil organic matter. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1988;52(6):1633–1640. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanaiotti TM, Martinelli LA, Victoria RL, Trumbore SE, Camargo PB. Past vegetation changes in Amazon savannas determined using carbon isotopes of soil organic matter. Biotropica. 2002;34(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44.MARGO Project Members Constraints on the magnitude and patterns of ocean cooling at the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat Geosci. 2009;2(2):127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masson-Delmotte V, et al. Information from paleoclimate archives. In: Stocker TF, et al., editors. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2013. pp. 383–464. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang P. Response of West Pacific margin seas to glacial cycles: Paleoceanographic and sedimentological features. Mar Geol. 1999;156(1-4):5–39. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding Y, Sun Y, Wang Z, Zhu Y, Song Y. Inter-decadal variation of the summer precipitation in China and its association with decreasing Asian summer monsoon Part II: Possible causes. Int J Climatol. 2009;29(13):1926–1944. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang F, Lau KM. Trend and variability of China precipitation in spring and summer: Linkage to sea-surface temperatures. Int J Climatol. 2004;24(13):1625–1644. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding ZL, Ren JZ, Yang SL, Liu TS. Climate instability during the penultimate glaciation: Evidence from two high-resolution loess records, China. J Geophys Res. 1999;104(B9):20123–20132. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stuiver M, Reimer PJ. Extended 14C data base and revised CALIB 3.0 14C age calibration program. Radiocarbon. 1993;35(1):215–230. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reimer PJ, et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon. 2013;55(4):1869–1877. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackson ML. Soil Chemical Analysis—Advanced Course. 2nd Ed University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmitt J, et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO₂ rise from ice cores. Science. 2012;336(6082):711–714. doi: 10.1126/science.1217161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melillo JM, et al. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics along the decay continuum: Plant litter to soil organic matter. Plant Soil. 1989;115(2):189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maher BA, Thompson R, Zhou LP. Spatial and temporal reconstructions of changes in the Asian palaeomonsoon: A new mineral magnetic approach. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1994;125(1-4):461–471. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu HY, Wu NQ, Liu KB, Jiang H, Liu TS. Phytoliths as quantitative indicators for the reconstruction of past environmental conditions in China II: Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction in the Loess Plateau. Quat Sci Rev. 2007;26(5-6):759–772. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang G, Li J, Liu X, Li X. Variations in carbon isotope ratios of plants across a temperature gradient along the 400 mm isoline of mean annual precipitation in north China and their relevance to paleovegetation reconstruction. Quat Sci Rev. 2013;63:83–90. [Google Scholar]