Significance

Adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) is distinct in its high starch and low fat accumulation. However, the underlying genetic basis is still not well understood. In this study, we generated a high-quality draft genome sequence of adzuki bean by using whole-genome shotgun sequencing strategy. By comparative genomic and transcriptome analyses, we demonstrated that the significant difference in starch and fat content between adzuki bean and soybean were caused by transcriptional abundance rather than copy number variations in the genes related to starch and oil synthesis. Furthermore, through resequencing of 49 population accessions, we identified strong selection during domestication and suggested that the semiwild adzuki bean was a preliminary landrace. Generally, our results provide insight into evolution and metabolism of legumes.

Keywords: adzuki bean, genome sequence, starch synthesis genes, fat synthesis genes, domestication

Abstract

Adzuki bean (Vigna angularis), an important legume crop, is grown in more than 30 countries of the world. The seed of adzuki bean, as an important source of starch, digestible protein, mineral elements, and vitamins, is widely used foods for at least a billion people. Here, we generated a high-quality draft genome sequence of adzuki bean by whole-genome shotgun sequencing. The assembled contig sequences reached to 450 Mb (83% of the genome) with an N50 of 38 kb, and the total scaffold sequences were 466.7 Mb with an N50 of 1.29 Mb. Of them, 372.9 Mb of scaffold sequences were assigned to the 11 chromosomes of adzuki bean by using a single nucleotide polymorphism genetic map. A total of 34,183 protein-coding genes were predicted. Functional analysis revealed that significant differences in starch and fat content between adzuki bean and soybean were likely due to transcriptional abundance, rather than copy number variations, of the genes related to starch and oil synthesis. We detected strong selection signals in domestication by the population analysis of 50 accessions including 11 wild, 11 semiwild, 17 landraces, and 11 improved varieties. In addition, the semiwild accessions were illuminated to have a closer relationship to the cultigen accessions than the wild type, suggesting that the semiwild adzuki bean might be a preliminary landrace and play some roles in the adzuki bean domestication. The genome sequence of adzuki bean will facilitate the identification of agronomically important genes and accelerate the improvement of adzuki bean.

Adzuki bean (Vigna angularis var. angularis) was domesticated in China ∼12,000 y ago (1) and is grown in more than 30 countries of the world, especially in East Asia (2, 3). Adzuki bean seed is an important source of protein, starch, mineral elements, and vitamins (4, 5). Because of its low caloric and fat content, digestible protein and abundant bioactive compounds, adzuki bean is referred to as the “weight loss bean” (6, 7). Given these characteristics, adzuki bean is widely used in a variety of foods (e.g., paste in pastries, desserts, cake, porridge, adzuki rice, jelly, adzuki milk, ice cream) for at least a billion people (8). Furthermore, adzuki bean is a traditional medicine that has been used as a diuretic and antidote, and to alleviate symptoms of dropsy and beriberi in China (9, 10).

Adzuki bean has broad adaptability, high tolerance to poor soil fertility, and is a high-value rotation crop that contributes to the improvement of soil condition by nitrogen fixation (11, 12). Additionally, adzuki bean can be used as a model species, especially for non-oilseed legumes because of its short growth period and small genome size (13, 14).

To accelerate the application of genomics for breeding and to better understand the biological mechanisms underlying its distinct characters, we generated and analyzed the genome sequence of adzuki bean variety Jingnong 6, which was bred by the Beijing University of Agriculture, China. The draft genome sequence provides a resource for studying adzuki bean genomics and genetics, promoting adzuki bean improvement.

Results and Discussion

Genome Sequencing and Assembly.

The widely adopted Chinese cultivar “Jingnong 6” was targeted for whole genome shotgun sequencing by using the HiSeq 2000 sequencing platform. In total, 132.28 Gb sequence data were generated (SI Appendix, Table S1). After filtering out low-quality reads, 90.88 Gb high-quality sequences (168 × coverage of the adzuki bean genome) were obtained and used for assembly with SOAPdenovo software (15). Briefly, we generated 450 Mb contigs with an N50 size of 38 kb, and 466.7 Mb scaffolds with an N50 size of 1.29 Mb (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). The assembled scaffolds represent 86.11% of adzuki bean genome (542 Mb) predicted by K-mer analysis (SI Appendix, Table S4). The GC content of adzuki bean genome is 34.8%, similar to other sequenced legume genomes (16–21) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

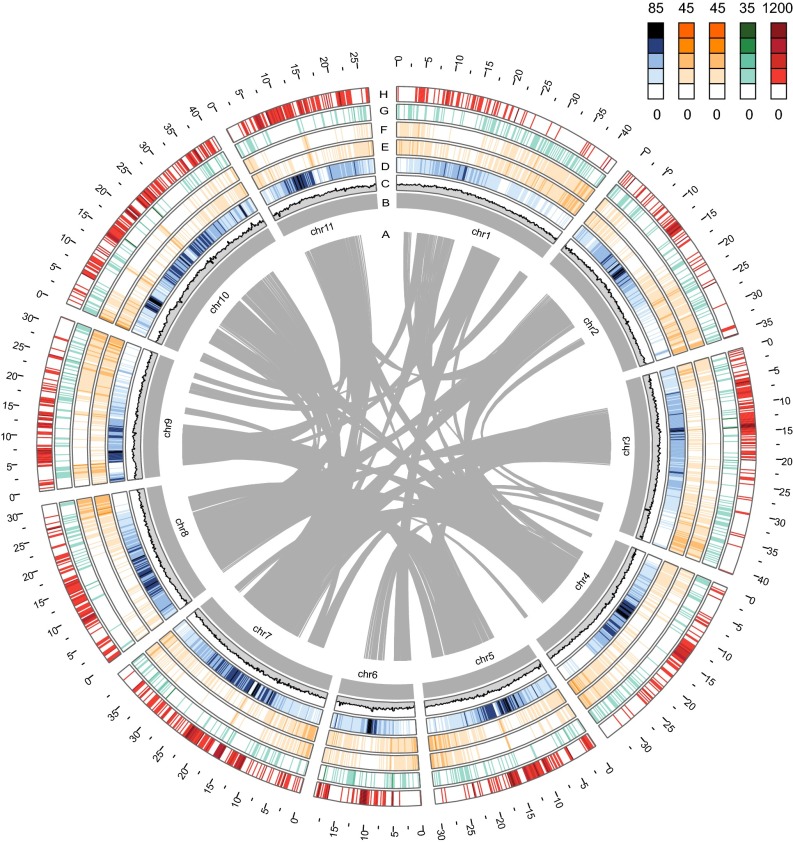

To anchor the scaffolds to the chromosomes, we constructed a high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genetic map via restriction-site associated DNA-sequencing (RAD-Seq) approach by using 150 F2 individuals derived from a cross of cultivar Ass001 with the wild adzuki bean accession no. CWA108. The genetic map was comprised of 1,571 SNPs covering 11 linkage groups, spanning 1,031.17 cM with an average of 4.33 mapped SNPs per scaffold, and a mean marker distance of 0.67 cM (Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In total, 372.9 Mb of scaffolds, representing 79.9% of adzuki bean genome, were assigned to the 11 pseudomolecules using these mapped SNPs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Fig. 1B). A low conflict between genetic map and the assembled scaffolds indicates high quality of the genome assembly (SI Appendix, Table S5 and Fig. S4).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the adzuki bean genome. (A) Gray lines connect duplicated genes among chromosomes of adzuki bean, and each line indicates a duplication block containing at least 30 genes. (B) Pseudomolecules of adzuki bean. Distribution of GC content (C), repeat sequences density (D), gene density (E), expressive gene density (F), SSR density (G), and SNP density (H) in continuous 200-kb windows were shown. The GC values range from 0.30 to 0.45.

Repetitive Sequence Analysis and Gene Prediction.

To analyze the repetitive sequences, we searched the genome sequence by using a combination of de novo and homology tools, and found that ∼44.51% (207.7 Mb) of adzuki bean genome consisted of repetitive DNA. The percentage of the repetitive sequences in adzuki bean genome is higher than that of Medicago and Lotus, and lower than that of soybean, chickpea, and pigeonpea, but similar to common bean (SI Appendix, Table S6). Consistent with the other legume genomes, the majority of the transposable elements were retrotransposons (34.57% of genome), whereas DNA transposons made up only 5.75% of the genome (SI Appendix, Table S7). Overall, ∼76.49% of the repetitive DNA was long terminal repeat retrotransposons of which 43.99% were Gypsy-type and 23.66% were Copia-type elements. An analysis of the adzuki bean genome with MIcroSAtellite (MISA) program (22) also allowed us to identify 16,230 simple sequence repeats (SSRs), containing di- (68.95%), tri- (18.12%), tetra- (1.98%), penta- (4.16%), and hexa- (6.79%) repeat units. Using these information, we designed 9,038 SSR primer pairs, and found that 24.7% of them exhibited polymorphism by analyzing 1,572 pair primers (SI Appendix, Table S8). These SSRs will be a useful resource for developing genetic markers and in genetic analysis of adzuki bean.

To predict protein-coding genes, we sequenced the transcriptomes of roots, stems, leaves, and seeds from three different developmental stages (beginning, full, and mature seed) of Jingnong 6, and generated ∼309 million RNA reads, which were used for mapping, clustering, and annotation of the whole genome (SI Appendix, Table S9). The transcriptome assembly consisted of 59,909 unitranscripts, of which 97.4% were covered by the genome assembly and 92.6% were captured in one scaffold with more than 90% of the unitranscript length, further confirms the high quality of the genome assembly (SI Appendix, Table S10).

Subsequently, we used a combination of de novo gene prediction, homology-based search, and RNA-Seq to predict gene models in the adzuki bean genome (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). A total of 34,183 protein-coding genes were predicted (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S11), of which 53.92% (18,432 genes) were supported by RNA-Seq data, 81.33% (27,801 genes) by TrEMBL, 59.67% (20,398 genes) by Swiss-Prot (23), and 63.35% (21,656 genes) by Interpro (24) database (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). There were 6,196 genes (18.13% of total genes) that were functionally unannotated (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The genes were distributed unevenly with an increase in density toward the ends of the pseudomolecules (Fig. 1E). The density of expressed genes was similar to the pattern of gene distribution being lower or absent in the high repeat DNA regions of the pseudomolecules (Fig. 1 D and F). Additionally, we identified 312 microRNAs, 307 tRNAs, 3,730 rRNAs and 314 small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) (SI Appendix, Table S12).

Comparison of Gene Families with Other Sequenced Legume Genomes.

Compared with six other sequenced legume genomes, the number of predicted genes in the adzuki bean genome was lower than soybean, pigeonpea, and Medicago, but higher than common bean, chickpea, and Lotus. Based on the proportion of the gene sequence to the whole genome (total gene length/genome size), adzuki bean has a higher ratio (22.98%) than the other legume species with the exception of Medicago (SI Appendix, Table S11).

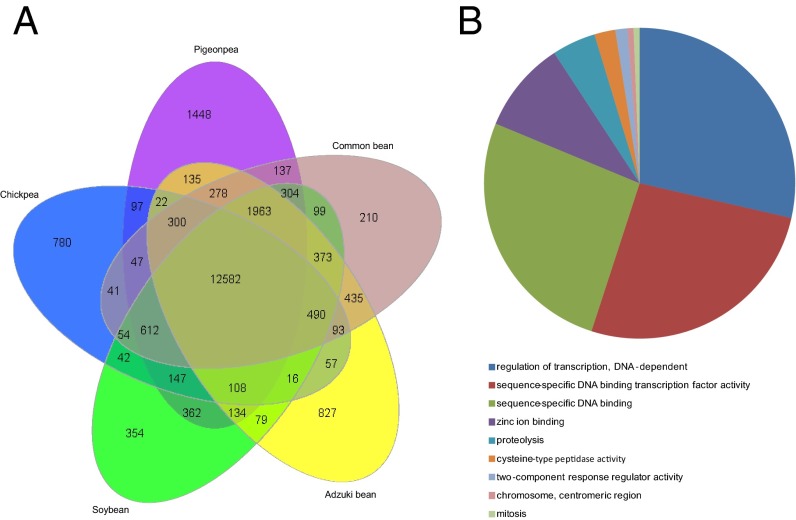

For further analysis, 76,211 gene families of adzuki bean, soybean, common bean, pigeonpea, and chickpea were clustered. We found that 12,582 gene families were common (orthologs) to all five legume genomes, whereas 827 gene families containing 5,446 genes were specific to adzuki bean, more than soybean, common bean, and chickpea, and lower than that in pigeonpea (Fig. 2A). An analysis of these specific genes using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) revealed that their functions mainly focused on the categories of zinc ion binding, proteolysis, cysteine-type peptidase activity, two-component response regulator activity, and mitosis (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Table S13). We also found that the single copy gene orthologs in adzuki bean were significantly more than those in soybean and similar to those in pigeonpea, chickpea, and common bean, whereas the multicopy orthologs in adzuki bean and the other three legume genomes were much less than that in soybean. This difference between adzuki bean and soybean is most likely related to the additional whole genome duplication (WGD) in soybean (17).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of gene families in genomes of adzuki bean, common bean, soybean, pigeonpea, and chickpea. (A) Venn diagram illustrating shared and unique gene families among the five species. (B) GO category of unique gene families of adzuki bean.

In total, 3,508 adzuki bean transcription factor genes, belonging to 63 families, were identified by a sequence comparison with known transcription factors, and by searching for known DNA-binding domains. These genes represented 10.26% of the total predicted genes in adzuki bean; this number was much lower than those in common bean, soybean, and Lotus but similar to that in other sequenced legume species (SI Appendix, Table S14). In addition, we analyzed the genes encoding R proteins in adzuki bean genome and compared them with other legume species (SI Appendix, Table S15). In total, 421 genes containing NBS or LRR domains were detected in the adzuki bean genome, which is significantly lower than that in soybean and common bean. However, there were markedly more CC_NBS genes in adzuki bean genome than that in soybean (SI Appendix, Table S15). This information should be helpful to identify the genes responsible for plant disease and for disease resistance breeding.

It has been reported that adzuki bean has quite low beany flavor and contains digestible protein and abundant bioactive compounds (4, 25, 26). Therefore, we analyzed genes related to flavonoid biosynthesis, lipoxygenase (LOX), and trypsin inhibitor in adzuki bean and other sequenced legume species, and no significant difference was observed in the gene number ratio (the gene number/the total gene number in the genome) (SI Appendix, Table S16). However, when we checked the expression of the LOX, which are responsible for the beany flavor in soybean (27), we found that their transcriptional amount was markedly lower in adzuki bean than that of soybean (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These results explain the low beany flavor of adzuki bean.

Legume lectin, which is widely distributed among leguminous plants, is a proteinaceous toxic factor that interacts with glycoprotein on the surface of red blood cells, causing them to agglutinate and a major antinutritional factor that inhibits the animal growth, and affects the nutritional value and nutrient digestibility (28). The lectin content (average 11.91 mg·g−1) is high in the grain of soybean (29), whereas it is low in adzuki bean (30). We found that legume lectin genes in adzuki bean showed significantly lower gene number ratio than that of other sequenced legume species with an exception of chickpea. Consistently, the expression of the lectin genes [sum of the reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (RPKM) of individual genes] was significantly lower in adzuki bean than that of soybean, particularly for Le1, which is an important lectin gene in soybean (gmx:100818710), but it is lacking in adzuki bean (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 and Table S17). This result indicates that Le1 may play a main role in lectin accumulation in soybean seed.

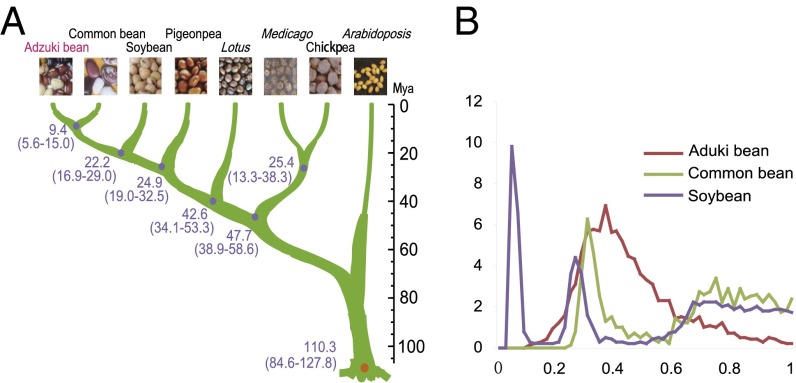

We analyzed gene family expansion and contraction (31) in seven legumes and Arabidopsis. Among all 26,120 gene families of the eight species, 5.39% (1,407) and 7.83% (2,046) of the genes were substantially expanded and contracted, respectively, in the adzuki bean during the 14 million years after speciation from common bean, whereas soybean had many more expanded gene families than common bean and adzuki bean (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), indicating that soybean has a universal expansion in gene families, coincident with the larger gene number. We subsequently analyzed the gene functions in the expanded gene families of adzuki bean and found enrichment in GO categories of zinc ion binding, proteolysis, cysteine-type peptidase activity, endopeptidase activity, endopeptidase inhibitor activity, lipid binding, and lipid transport (SI Appendix, Tables S18 and S19). For the contracted gene families of adzuki bean, they were enriched in the categories of protein serine/threonine kinase activity, protein kinase activity, protein tyrosine kinase activity, and defense response (SI Appendix, Table S20).

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny of the seven genome-sequenced legumes. (A) Phylogenetic tree and divergence time of genome-sequenced legume species, taking Arabidoposis thaliana as an out group taxon. (B) Distributions of 4DTv distance within adzuki bean, common bean, and soybean genomes.

Genome Duplication and Synteny Analysis.

Through ortholog search, we detected a total of 1,501 duplicated syntenic blocks within the adzuki bean genome. The gene number in a syntenic block ranged from 6 to 103 with an average of 11.7. The nucleotide diversity for the fourfold degenerate third-codon transversion site (4DTv) showed one clear peak (4DTv∼0.36) in the adzuki bean genome (Fig. 3B), consistent with the whole genome duplication (WGD) event of Papilionoideae (32, 33). We did not identify the peak of the recent WGD (4DTv∼0.056) found in soybean, indicating that adzuki bean, like most of the sequenced legumes, does not have this glycine-specific event. Further phylogenetic analysis showed that adzuki bean diverged from pigeonpea ∼19.0–32.5 million years ago (Mya), from soybean at ∼16.9–29.0 Mya, and from common bean at ∼5.6–15.0 Mya (Fig. 3A).

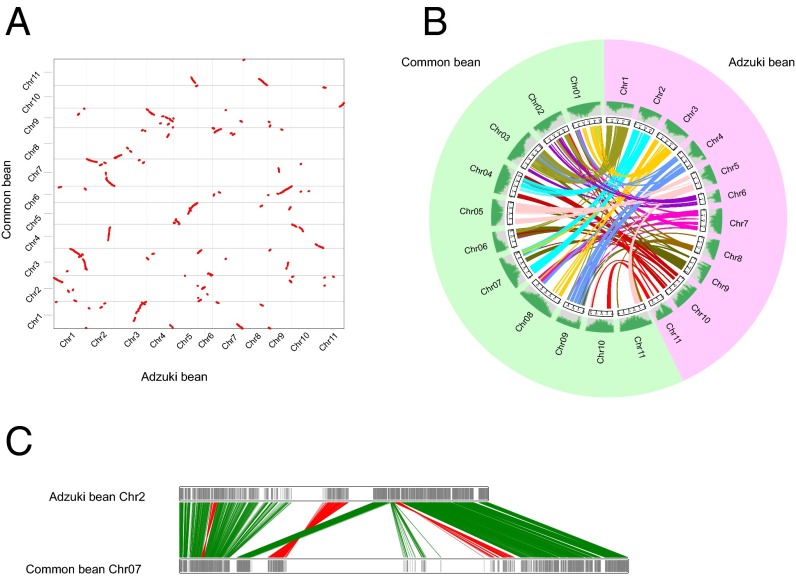

Synteny analysis revealed that, as expected, adzuki bean had higher conservation with common bean than with other legume species (SI Appendix, Table S21 and Fig. 4A). Most of the chromosomes aligned between adzuki bean and common bean (e.g., adzuki bean chromosome 2 and common bean chromosome 7, adzuki bean chromosome 5 and common bean chromosome 5, adzuki bean chromosome 1 and common bean chromosome 3, and adzuki bean chromosome 4 and common bean chromosome 9) (Fig. 4 A–C). However, some chromosomes of adzuki bean matched to more than one chromosome of common bean, suggesting chromosome rearrangements had occurred in the two genomes after speciation.

Fig. 4.

Genome synteny between adzuki bean and common bean chromosomes. Dotplot (A) and circos (B) figures of gene syntenic blocks (≥30 genes in each block) between adzuki bean and common bean chromosomes. The chromosome orientations in B are clockwise. (C) Colinearity of genes of adzuki bean chromosome 2 with common bean chromosome 7. The green and red lines indicate forward and reverse syntenic relationships, respectively.

We also did a comparison between adzuki bean and soybean. These results showed that each adzuki bean chromosome matched to several chromosomes of soybean, indicating that more arrangements occurred after speciation, and it is probably a result of the recent independent WGD in soybean (SI Appendix, Fig. S10).

Starch and Fatty Acid Biosynthesis and Metabolism Genes.

The legume family, the second most important crop family, is divided into oil and non-oil types based on the storage compounds in the seed. Adzuki bean is a typical non-oil legume, whereas soybean belongs to the oil type. Compared with soybean, adzuki bean seed has much more starch (57.06% vs. 25.3%) and much less crude fat (0.59% vs. 22.5%) (5, 34). To investigate the bases behind this difference, we analyzed genes related to starch and oil biosynthesis.

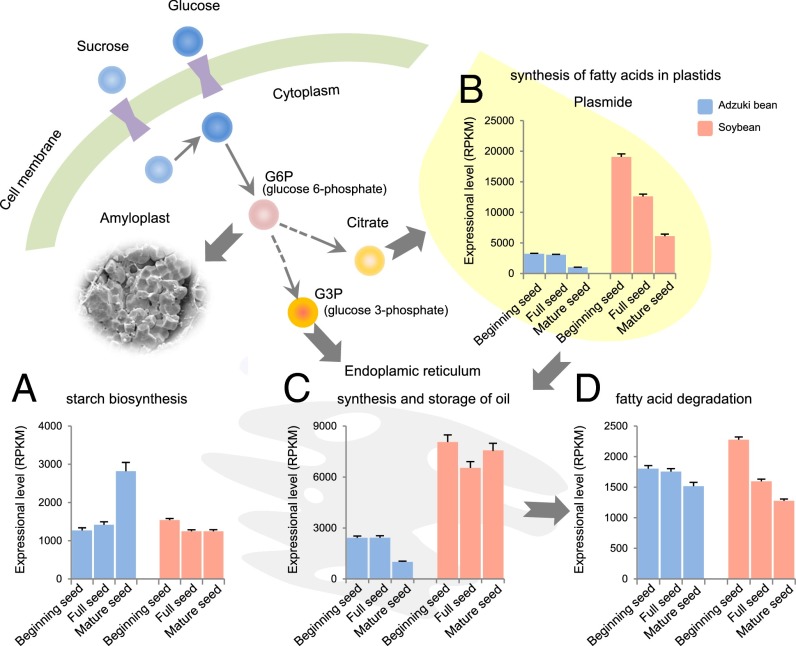

Using the starch biosynthesis genes in rice (35, 36) as bait, we performed an ortholog search in the adzuki bean and soybean genomes. In total, fewer starch biosynthesis genes were found in adzuki bean than in soybean (27 vs. 46) (SI Appendix, Table S22), but the χ2 test result showed that the ratio of the starch biosynthesis genes (number of starch synthesis genes/total gene numbers) was not significantly different between these two genomes (P = 0.4135). We then examined the transcriptional activity of these genes at three seed development stages (beginning, full, and mature seed) of the two species with two biological replicates collected in 2013 and 2014. The transcriptional level of each gene was normalized by using 47 constitutive expression genes in both species (SI Appendix, Table S23). We found that both the total transcriptional amount of starch biosynthesis genes (sum of the RPKM of individual genes) and average transcription of individual starch biosynthesis genes (mean of the RPKM of individual genes) in adzuki bean at the mature seed stage was significantly higher than that in soybean (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12 and Table S24), although more starch biosynthesis genes were detected in the soybean genome (SI Appendix, Table S22). However, no significant differences were observed at the two earlier stages of seed development. Another interesting phenomenon was that the transcription of starch biosynthesis genes continuously increased in adzuki bean, especially at the mature seed stage, whereas the expression of these genes in soybean decreased at the full and mature seed stages (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the expression of the genes related to starch, fatty acid, and oil biosynthesis in adzuki bean and soybean. The transcriptional amount of genes related to starch biosynthesis (A), synthesis of fatty acids in plastids (B), synthesis and storage of oil (C), and fatty acid degradation (D) in adzuki bean and soybean seeds at three developmental stages.

Subsequently, we searched for genes related to fatty acid synthesis in plastids, the synthesis and storage of oil, and fatty acid degradation in the adzuki bean and soybean genomes. Although more genes were found in soybean than that in adzuki bean, the copy number of the genes was not significantly different relative to the total gene numbers of the two genomes (SI Appendix, Table S25). The transcription of the genes related to fatty acid synthesis in plastids and the synthesis and storage of oil were markedly higher in soybean than those in adzuki bean (Fig. 5 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12 and Tables S26 and S27). We also found that the two classes of genes exhibited differential expression patterns. Genes related to fatty acid synthesis in plastids exhibited a higher transcriptional level at earlier developmental stages in both adzuki bean and soybean, whereas the expression of oil synthesis and storage genes was maintained in soybean but decreased in adzuki bean at the later stage. The transcriptional amount of genes related to fatty acid degradation in soybean was higher at the beginning seed stage and lower at the latter two stages than that observed in adzuki bean (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12 and Table S28). In addition, we checked the expression of five key genes that encode the proteins that were involved in the conversion from starch to oil synthesis: amylase (an enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of starch into sugars) (37), starch phosphorylase (an enzyme involving in phosphorolytic degradation of starch) (38), phosphofructokinase (PFK, a kinase catalyzing the phosphorylation of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate in the glycolytic pathway) (39), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH, an enzyme catalyzing the dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol-3-phosphate, and serving as a major link between carbohydrate metabolism and lipid metabolism; ref. 40), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC, a biotin-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the irreversible carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to produce malonyl-CoA for the biosynthesis of fatty acids) (41). All of the five genes showed a higher expression in soybean at all three seed development stages compared with adzuki bean (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 and Table S29). Based on these results, we speculated that the transcriptional amount of the genes related to starch and oil synthesis between soybean and adzuki bean are responsible for the differences of starch and fat content in the two species. Future detailed comparative genomic analysis of different species will help to answer the underlying mechanism.

Diversity and Domestication Analysis.

In general, it is believed that adzuki bean cultigen, including landraces and improved cultivated variety, was domesticated from its putative wild progenitor (V. angularis var. nipponensis) (42). To investigate the genetic diversity variation and selective sweeps during adzuki bean domestication, we performed whole genome resequencing of 11 wild, 17 landraces, and 10 improved cultivars (SI Appendix, Table S30). Besides the wild type, landrace, and cultivar, another intermediate type, semiwild adzuki bean (weedy), has been recognized (2, 43). However, the genetic base of semiwild adzuki bean was arguable. So far, it is not clear whether semiwild adzuki bean was closely related to cultigen or wild adzuki bean or belongs to the landrace (44, 45). To make the resequencing population representative, we performed resequencing of 11 semiwild adzuki beans as well. Therefore, a total of 49 adzuki bean accessions were resequenced in this study.

The whole genome resequencing yielded 254.41 Gb of high-quality clean data. The sequencing depths of the 49 accession genomes ranged from 5.3× to 27.34×. The reads were aligned to adzuki bean reference genome by using SOAP2 (46) software, showing a mapping rate varied from 80.11 to 95.37%. In total, 5,539,411 SNPs were identified among the 50 accessions across the entire genome by SOAPsnp (47). Similar results were obtained by BWA (48) along with SAMtools (49) analysis (SI Appendix, Table S31).

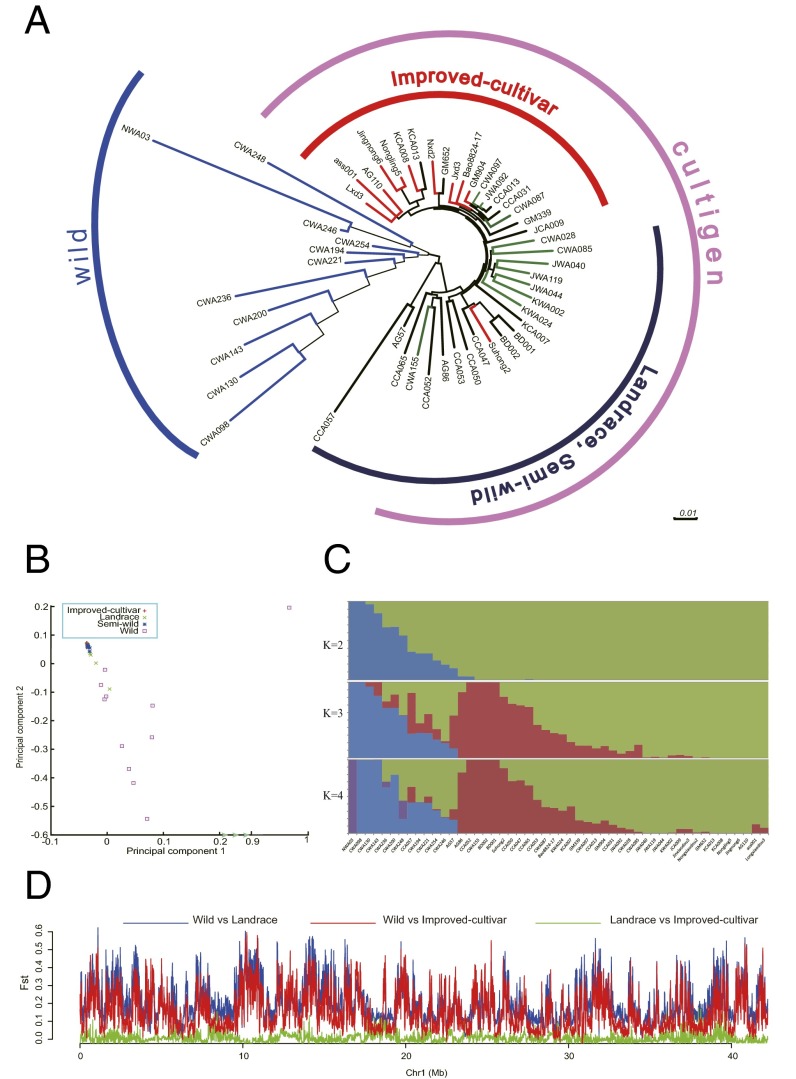

The neighbor joining tree illustrated that the 50 adzuki bean accessions could be divided into two main groups (Fig. 6A). The 11 wild accessions clustered clearly together in a group, whereas the remaining 39 accessions, including the semiwild accessions, landraces, and improved varieties, were grouped in another group. The 11 semiwild accessions spread among the landraces and improved varieties. These results demonstrated that the semiwild adzuki bean had a closer relationship to cultigen adzuki bean than that of wild type. Principal components analysis (50) also suggested that the semiwild adzuki beans had a closer relationship with landraces and improved varieties than wild adzuki beans (Fig. 6B). The structure plots (51) showed the three types were separated into three groups when K was set as 3 without clear admixture (Fig. 6C). Based on all these comprehensive analyses, the semiwild adzuki bean seemed to be a distinct ecotype as the progenitor of cultigen accessions (44), rather than an escape from old cultivars and derivatives from a hybrid between wild and cultivars (42). Therefore, we classified the semiwild adzuki beans into landrace in the following selection analyses.

Fig. 6.

Genetic relationships in 50 adzuki bean accessions. (A) Neighbor joining tree showing relationships of wild (blue), semiwild type (green), landraces (black), and improved varieties (red). (B) Principal component analysis of the 50 adzuki bean individuals. (C) Structure analysis of the 50 adzuki bean individuals based on SNP data. (D) Fst distribution on Chr1 for landrace vs. wild, improved variety vs. wild, and landrace vs. improved variety.

We detected strong selection sweep signals [indicated by fixation index (FST)] during the adzuki bean domestication, which distribute across all chromosomes (SI Appendix, Figs. S14 and S15 and Table S31). The selection pressure detected between landraces and cultivars were obviously lower than that between wild and cultivars, which had much lower FST values, for example the FST values of the adzuki bean chromosome 1 (Fig. 6D). The results suggested that the domestication from the wild accession to cultivars is thorough and continuous. The genes in the selection regions enriched mainly in the KEGG pathways of plant–pathogen interaction, plant hormone signal transduction, aminobenzoate degradation, cell cycle, and folate biosynthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S16).

Conclusion

In this study, we obtained a high quality draft adzuki bean genome sequence, in which more than 86% of the genome was assembled, and approximately 80% of sequences were assigned to chromosomes. A total of 34,183 protein-coding genes were predicted. Genome duplication analysis revealed that the adzuki bean genome, unlike soybean, lacked the event of the recent whole genome duplication. Compared with other sequenced legume genomes, the adzuki bean genome had a higher synteny with common bean than that of soybean, pigeonpea, Medicago, chickpea, and Lotus. More interestingly, we revealed that the low fat and high starch contents in adzuki bean seed were not caused by the gene copy number variation, but by gene expression amount in comparison with soybean. Additionally, we also found that the semiwild adzuki bean would be a kind of preliminary landrace by population analysis with the 11 wild, 11 semiwild accessions, 17 landraces, and 11 improved varieties, and detected strong selection signals in domestication. Generally, our results valuably reinforce the legume species genomes, provide insight into evolution and metabolic differences of legumes, and will accelerate studying of genetics and genomics for adzuki bean improvement.

Materials and Methods

Adzuki bean (V. angularis var. angularis) cultivar Jingnong 6 (a popular variety in China) was used for whole genome sequencing. Forty-nine adzuki bean accessions, including 11 wild adzuki bean (V. angularis var. nipponensis), 11 semiwild type, 17 landraces, and 10 improved cultivars were performed for their whole genome resequencing. The details of sequencing, assembly, annotation, genome analysis, and diversity and evolution analysis were described in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Huimin Wang (Beijing University of Agriculture) and Yuncong Yao (Beijing University of Agriculture) for project initiation and support and Dr. Scott Allen Jackson (University of Georgia) for revising the manuscript. Financial support was provided by Research Base and Technological Innovation Platform Project of Beijing Municipal Education Committee Grant PXM2014_014207_000017, Enhancing Scientific Research Level of the Beijing University of Agriculture Grant 1086716176, and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31371694, 31272238, and 31071474. This paper is dedicated to the late Professor Wenlin Jin, who devoted his life to adzuki bean research. The sequencing Jingnong 6 variety was bred by Prof. Jin.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.A.W. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DNA Data Bank of Japan/European Molecular Biology Laboratory/GenBank under the accession no. JZJH00000000. The version described in this paper is version JZJH01000000. All short-read data have been deposited into the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession no. SRA259080. Raw sequence data of the transcriptomes have been deposited into the SRA under accession no. SRA260020.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1420949112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Liu L, Bestel S, Shi J, Song Y, Chen X. Paleolithic human exploitation of plant foods during the last glacial maximum in North China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(14):5380–5385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217864110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomooka N, et al. In: The Asian Vigna: Genus Vigna Subgenus Ceratotropis Genetic Resources. Tomooka N, editor. Kluwer Acad Pub; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2002. pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer C, et al. Control of volunteer adzuki bean in soybean. Agri Sci. 2012;3(4):501–509. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin RF, et al. In: Minor Grain Crops in China. Yun L, editor. Agric Sci Tech Press; Beijing: 2002. pp. 192–209. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu N, et al. Establishment of an adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) core collection based on geographical distribution and phenotypic data in China. Acta Agron Sin. 2008;34(8):1366–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amarowicz R, et al. Antioxidant activity of extract of adzuki bean and its fractions. J Food Lipids. 2008;15(1):119–136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitano-Okada T, et al. Anti-obesity role of adzuki bean extract containing polyphenols: in Vivo and in vitro effects. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92(13):2644–2651. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lestari P, et al. Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism discovery and validation in adzuki bean. Mol Breed. 2014;33(2):497–501. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li S (1590, Ming Dynasty) (2010) Compendium of Materia Medica (Yunnan Educ Press, Kunming, China), p 255.

- 10.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission 2010. Chinese Pharmacopeia (the 2010 Edition), eds Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission (China Med Sci Press, Beijing), p 147.

- 11.Duan H. Small bean. In: Duan H, Long J, Lin L, Xu H, editors. Edible Bean Crops. Sci Pub House; Beijing: 1989. pp. 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikkema PH, et al. Response of adzuki bean to pre-emergence herbicides. Can J Plant Sci. 2006;86(2):601–604. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parida A, Raina SN, Narayan RKJ. Quantitative DNA variation between and within chromosome complements of Vigna species (Fabaceae) Genetica. 1990;82(2):125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada T, Teraishi M, Hattori K, Ishimoto M. Transformation of azuki bean by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2001;64(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20(2):265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmutz J, et al. A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):707–713. doi: 10.1038/ng.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmutz J, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varshney RK, et al. Draft genome sequence of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), an orphan legume crop of resource-poor farmers. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(1):83–89. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varshney RK, et al. Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):240–246. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young ND, et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature. 2011;480(7378):520–524. doi: 10.1038/nature10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato S, et al. Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 2008;15(4):227–239. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106(3):411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R. InterProScan--an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(9):847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao Y, Cheng X, Wang L, Wang S, Ren G. A determination of potential α-glucosidase inhibitors from Azuki Beans (Vigna angularis) Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(10):6445–6451. doi: 10.3390/ijms12106445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto A, et al. Partial purification and product specificity of adzuki bean lipoxygenase. J Jap Soc Food Sci Tech. 1991;38(3):214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies CS, Nielsen SS, Nielsen NC. Flavor improvement of soybean preparations by genetic removal of lipoxygenase-2. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1987;64(10):1428–1433. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant G. Anti-nutritional effects of soyabean: A review. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1989;13(3-4):317–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang ML, Wang JA. Agglutinin content determination and germplasm cluster analysis in soybean seed. Soybean Bulletin. 2009;5:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant G, More LJ, McKenzie NH, Stewart JC, Pusztai A. A survey of the nutritional and haemagglutination properties of legume seeds generally available in the UK. Br J Nutr. 1983;50(2):207–214. doi: 10.1079/bjn19830090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. CAFE: A computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(10):1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertioli DJ, et al. An analysis of synteny of Arachis with Lotus and Medicago sheds new light on the structure, stability and evolution of legume genomes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavin M, Herendeen PS, Wojciechowski MF. Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary. Syst Biol. 2005;54(4):575–594. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin WL, et al. Appraisal of quality characters for seeds of Chinese adzuki bean local varieties. J Chin Cereals Oils Assoc. 2006;21(4):50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian Z, et al. Allelic diversities in rice starch biosynthesis lead to a diverse array of rice eating and cooking qualities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):21760–21765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912396106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohdan T, et al. Expression profiling of genes involved in starch synthesis in sink and source organs of rice. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(422):3229–3244. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manners DJ. Enzymic synthesis and degradation of starch and glycogen. Adv Carbohydr Chem. 1962;17:371–430. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tiwari R, Kumar A. Starch phosphorylase: Biochemical and biotechnological perspectives. Biotechnol Mol Bio Rev. 2012;7(3):69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sweetlove LJ, Kruger NJ, Hill SA. Starch synthesis in transgenic potato tubers with increased 3-phosphoglyceric acid content as a consequence of increased 6-phosphofructokinase activity. Planta. 2001;213(3):478–482. doi: 10.1007/s004250100544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen W, et al. Metabolic and transcriptional responses of glycerolipid pathways to a perturbation of glycerol 3-phosphate metabolism in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(30):22957–22965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abo Alrob O, Lopaschuk GD. Role of CoA and acetyl-CoA in regulating cardiac fatty acid and glucose oxidation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(4):1043–1051. doi: 10.1042/BST20140094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaguchi H. Wild and weed azuki beans in Japan. Econ Bot. 1992;46(4):384–394. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi H, Nikuma Y. Biometric analysis on classification of weed, wild and cultivated azuki beans. J Weed Sci Technol. 1996;41(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu RQ, Tomooka N, Vaughan DA, Doi K. The Vigna angularis complex: Genetic variation and relationships revealed by RAPD analysis, and their implications for in situ conservation and domestication. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2000;47(2):123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon MS, Lee J, Kim CY, Baek HJ. Genetic relationships among cultivated and wild Vigna angularis (Willd.) Ohwiet Ohashi and relatives from Korea based on AFLP markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2007;54(4):875–883. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li R, et al. SOAP2: An improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li R, et al. SNP detection for massively parallel whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 2009;19(6):1124–1132. doi: 10.1101/gr.088013.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang H, Peng J, Wang P, Risch NJ. Estimation of individual admixture: Analytical and study design considerations. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;28(4):289–301. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.