Abstract

Acremonium spp. cause human superficial infections including mycetoma, onychomycosis and keratitis. There are a few reports of systemic involvement in immunocompromised patients. However, isolated pulmonary infection in otherwise healthy hosts has never been reported in the literature.

Herein, we report a 59 year-old diabetic man with non-resolving pneumonia due to Acremonium spp. and provide a consensus review of the published clinical cases of systemic and respiratory tract infections.

Keywords: Acremonium, Pneumonia, Diabetes, Immunocompromised host, Systemic infection

INTRODUCTION

Acremonium formerly known as cephalosporium, is recognized as a causative agent of human skin infections (1). Eumycotic mycetoma– mycetoma due to fungi- is caused by a variety of fungi but not commonly by Acremonium (2). Moreover, the most common pathogens of onychomycosis (fungal infection of nails) are dermatophytes and Fusarium spp. followed by Acremonium spp. (3).

Several cases of ocular infections particularly keratitis have been published in the literature (4).

Localized infections (other than skin, nail and eyes) and systemic involvement due to Acremonium spp. are not common and have been reported in case reports.

Pneumonia and disseminated infections including meningitis, endocarditis, and cerebritis have been rarely reported. The reports of systemic infections, particularly pulmonary diseases, are almost always in patients with underlying risk factors such as malignancies and transplantation (1). Literature reviews revealed no case of pulmonary disease in otherwise healthy patients.

We report an unusual case of pulmonary infection due to Acremonium in a diabetic man who was properly treated with itraconazole.

CASE SUMMARIES

A 59 year-old man was admitted with complaints of productive cough and dyspnea. He was healthy until approximately 2 months earlier when he experienced fever, chills and productive cough during a trip to the north of Iran. Non-massive hemoptysis occurred soon after initial presentation. His symptoms worsened despite outpatient management of pneumonia with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. He also developed night sweat and purulent sputum.

Due to progressive symptoms and significant weight loss as well as chest imaging findings (Figure 1), bronchoscopy was performed without remarkable findings. Due to antibiotic treatment failure, he had been treated with standard anti-tuberculosis regimen for 6 weeks in another center without any response.

Figure 1.

The left chest-X-ray revealed alveolar infiltration in the right lower lobe before diagnosis.

He lived with his wife and three healthy children and worked as a manager of a service company. He reported smoking 3 cigarettes per day since 20 years ago and occasionally inhaled opiates. He was diabetic since 19 years ago controlled with oral medications. He was otherwise healthy. He did not recall any contact with birds and animals nor with chemical agents.

On admission, he was febrile (38.5°C oral temperature) and normotensive with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute and oxygen saturation rate of 91% with ambient air.

Physical examination was normal except for pallor of conjunctiva.

Further investigations revealed normochromic normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.5 mg/dl), leukocytosis (12400 cells/mm3, polymorphonuclears: 76%, eosinophils: 4%), thrombocytosis (536,000/mm3), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (130 mm/1st hr.), normal liver biochemistry and renal function tests. Urinalysis was normal. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were negative. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) were 6.9% and 115 mg/dl, respectively. Level of immunoglobulins and lymphocytes, flow cytometric analysis and nitroblue tetrazolium test as well as human immune deficiency virus serology were unremarkable. Moreover, scar of the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine was evident.

Echocardiography was normal. Repeated bronchoscopy in our center revealed mucosal secretion without endobronchial lesion. Transbronchial lung biopsy as well as bronchoalveolar lavage specimens were negative for pathogenic bacteria, fungi and mycobacterial agents by smears, cultures and polymerase chain reaction.

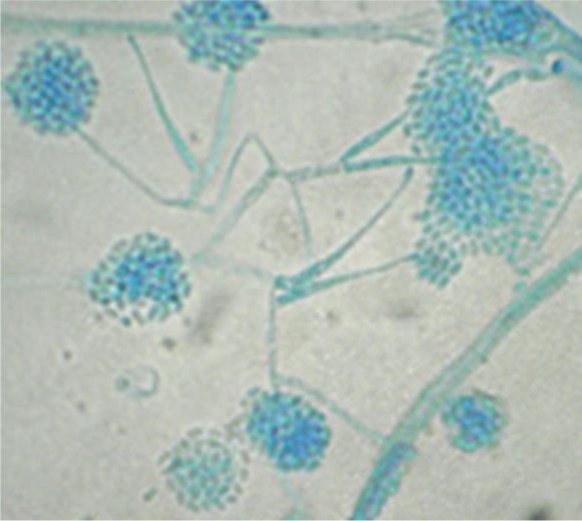

Based on his progressive condition and negative investigations (Figure 2), CT-guided biopsy of the lung lesion was performed, which revealed alveolated lung parenchyma with interstitial thickening due to infiltration of lymphoplasma cells as well as some eosinophils and a few ill-defined hyaline septate hyphae. After a few days, white yellow colonies grew in Sabouraud dextrose agar. As observed microscopically, it was hyaline mold producing conidia in clusters compatible with Acremonium spp. The conidia were elongated and arranged in loose clusters in a crisscross formation at the tip of a long, slender, delicate conidiophore (Figures 3 and 4). Biochemical analysis confirmed the morphological diagnosis of the cultured microorganism to be Acremonium spp.

Figure 2.

Chest CT revealed alveolar consolidation and adjacent ground glass opacity in the right lower lobe.

Figure 3.

Lung biopsy revealed alveolated lung parenchyma with interstitial thickening due to infiltration of lymphoplasma cells and a few eosinophils.

Figure 4.

Microscopic view of Acremonium hypha and conidia; direct smear of the isolated organism from the culture medium

Itraconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated and within a week, respiratory symptoms ameliorated and after a couple of weeks he was symptom-free and chest-X-ray was completely normal (Figure 5). The patient continued taking itraconazole for a period of 6 months.

Figure 5.

Chest-X-ray 8 weeks after treatment with itraconazole.

DISCUSSION

This case is extremely rare according to previous reports of all over the world. Acremonium pneumonia has been reported in a few case series and single reports (1) occurring in immunocompromised hosts such as leukemic or post-transplantation patients. Although our patient may be considered relatively immunocompromised due to diabetes, we could not find any report of lung infection in patients with minor immunodeficiency. On the other hand, our patient had controlled diabetes according to A1C and FPG analyses, and he had neither microvascular nor macrovascular complications of diabetes. He had no prior episode of infection and physical examinations and laboratory investigations did not demonstrate any other immunodeficiency.

Guarro et al. reviewed all cases of Acremonium spp. published in the literature until 1997. Thirty-seven localized and disseminated infections other than well-known superficial infections (skin and ocular) were found. All patients, except for 3 cases whose data regarding possible underlying risk factors were not available, were significantly immunocompromised. Nine patients had documented malignancies and 4 were diagnosed as transplant-related (1).

Five cases of lung infection were reported among them one patient had multiple myeloma with multi-organ involvement. In a patient with chronic granulocytic leukemia, Acremonium was isolated from blood and lungs; two others had concurrent skin infection occurred after trauma and environmental inoculation (1). Only in one patient with underlying chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), an isolated pulmonary infection was noted.

Literature review since 1997 revealed 39 cases of systemic infections in addition to previous reports. All of them were in patients with significant immunodeficiency and compromising conditions. CGD, leukemia, bone marrow transplantation, and prolonged neutropenia were found in patient histories. A vast majority of patients (12 cases) had inoculated infections associated with peritoneal dialysis, implanted devices and indwelling catheters. Thus, real systemic infections appeared to be only 15 cases (5–9). Pulmonary infection due to Acremonium spp. has only been reported in 10 cases summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

All cases of pulmonary infections due to Acremonium spp. published in the literature

| Year of publication | Underlying disease | Involved sites | Species | Reference number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Chronic granulomatous disease | Lungs | A. strictum* | 6 |

| 2003 | Mantle cell lymphoma | Fungemia, skin and lungs | NA** | 7 |

| 2003 | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Fungemia, skin and probably lungs | NA | 7 |

| 2002 | Chronic myelocytic lymphoma | Lungs | A. strictum | 8 |

| 1998 | Post-chemotherapy medullary aplasia | Lungs | A. strictum | 9 |

| 1998 | Myeloma | Lung, nail, heart, kidney | A. strictum | 1 |

| 1991 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | Lungs, skin | Acremonium spp. | 1 |

| 1943 | Pneumothorax | Lungs | Acremonium spp. | 1 |

| 1984 | Chronic granulomatous disease | Lungs | A. strictum | 1 |

| 1993 | Multiple trauma | Skin, Lungs | A. strictum | 1 |

Acremonium strictum,

Not available

In a case of colon adenocarcinoma, Staphylococcus aureus and Acremonium strictum were isolated from the pleural fluid (10). Herrera et al. assumed that indoor exposure to Acremonium spp., as a biological contaminant, increased the occurrence of symptoms of asthma in young children; interestingly, their analysis showed greater association of Acremonium than dust mites (11). However, the role of Acremonium in hypersensitivity pneumonia has not been demonstrated in the literature (12).

Identification of Acremonium and differentiation from other similar fungi including Fusarium, Paecilomyces and etc. is important for histopathologists. A few reports demonstrated misidentification of the aforementioned isolates in tissue biopsy as Aspergillus or Candida (13).

Odabasi et al. stated that Beta -D glucan (BG) has the potential to identify invasive fungal infections such as Acremonium spp. However, further investigations are required to establish a definite cut off for such rare fungal agents. On the other hand, the effect of treatment on the serum levels of BG remains to be clarified (14).

Anecdotal reports recommend that treatment of invasive Acremonium infections requires a combination of medical treatment with amphotericin B and surgical intervention (4).

A study by Guarro et al. revealed the Acremonium strains had little susceptibility to antifungals such as ketoconazole, amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, itraconazole, miconazole, and fluconazole (1). Fluconazole and 5-fluorocytosine were completely ineffective; and amphotericin B was the best choice. A study by Saldarreaga et al. revealed a similar resistance profile for azoles; although voriconazole was not included. They recommended susceptibility testing for Acremonium spp. due to high-rate of resistance to azoles (15).

Recently, several cases of successful treatment with voriconazole have been published and it seems that voriconazole, at least according to case series, is going to be the choice of treatment for Acremonium; although, this topic remains to be studied with appropriately designed clinical trials and more cases (7). Interestingly, our patient was treated efficiently with itraconazole without any complication.

CONCLUSION

Acremonium fungal infection may emerge in immunocompromised hosts particularly after chemotherapy, in post-transplantation period and in patients with primary immunodeficiency e.g. CGD. Physicians should be aware of rare fungal pathogens in patients with non-resolving pneumonia.

To our knowledge, this case is the first pulmonary infection caused by Acremonium in a patient without significant immunodeficiency except for well-controlled diabetes. Interestingly, in contrast to previous reports, our case was successfully treated with itraconazole and his follow-up revealed complete remission without respiratory or systemic complications.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, Gené J. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists--in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25 (5): 1222– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. Mycetoma. In: Medical Mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1992: 560– 93. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hay RJ. Dermatophytosis and Other Superficial Mycoses. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. (Editors). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. &th Edition Philadelphia: Churchill and Livingstone Elsevier; 2010: 3345– 55. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, Newman CL, Espinel-Ingroff A, Shadomy HJ. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore) 1991; 70 (6): 398– 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan Z, Al-Obaid K, Ahmad S, Ghani AA, Joseph L, Chandy R. Acremonium kiliense: reappraisal of its clinical significance. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49 (6): 2342– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pastorino AC, Menezes UP, Marques HH, Vallada MG, Cappellozi VL, Carnide EM, et al. Acremonium kiliense infection in a child with chronic granulomatous disease. Braz J Infect Dis 2005; 9 (6): 529– 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mattei D, Mordini N, Lo Nigro C, Gallamini A, Osenda M, Pugno F, et al. Successful treatment of Acremonium fungemia with voriconazole. Mycoses 2003; 46 (11–12): 511– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herbrecht R, Letscher-Bru V, Fohrer C, Campos F, Natarajan-Ame S, Zamfir A, et al. Acremonium strictum pulmonary infection in a leukemic patient successfully treated with posaconazole after failure of amphotericin B. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2002; 21 (11): 814– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breton P, Germaud P, Morin O, Audouin AF, Milpied N, Harousseau JL. Rare pulmonary mycoses in patients with hematologic diseases. Rev Pneumol Clin 1998; 54 (5): 253– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nedret Koç A, Mutlu Sarigüzel F, Artiş T. Isolation of Acremonium strictum from pleural fluid of a patient with colon adenocarcinoma. Mycoses 2009; 52 (2): 190– 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herrera AB, Rodríguez LA, Niederbacher J. Biological pollution and its relationship with respiratory symptoms indicative of asthma, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Biomedica 2011; 31 (3): 357– 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Unoura K, Miyazaki Y, Sumi Y, Tamaoka M, Sugita T, Inase N. Identification of fungal DNA in BALF from patients with home-related hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respir Med 2011; 105 (11): 1696– 703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu K, Howell DN, Perfect JR, Schell WA. Morphologic criteria for the preliminary identification of Fusarium, Paecilomyces, and Acremonium species by histopathology. Am J Clin Pathol 1998; 109 (1): 45– 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Odabasi Z, Mattiuzzi G, Estey E, Kantarjian H, Saeki F, Ridge RJ, et al. Beta-D-glucan as a diagnostic adjunct for invasive fungal infections: validation, cutoff development, and performance in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39 (2): 199– 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saldarreaga A, Garcia Martos P, Ruiz Aragón J, García Agudo L, Montes de Oca M, Puerto JL, et al. Antifungal susceptibility of Acremonium species using E-test and Sensititre. Rev Esp Quimioter 2004; 17 (1): 44– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]