Abstract

Aquilaria sinensis, a kind of typically wounding-induced medicinal plant with a great economical value, is widely used in the production of traditional Chinese medicine, perfume and incense. Coronatine-insensitive protein 1 (COI1) acts as a receptor in jasmonate (JA) signaling pathway, and regulates the expression of JA-responsive genes in plant defense. However, little is known about the COI1 gene in A. sinensis. Here, based on the transcriptome data, a full-length cDNA sequence of COI1 (termed as AsCOI1) was firstly cloned by RT–PCR and rapid-amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) strategies. AsCOI1 is 2330 bp in length (GenBank accession No. KM189194), and contains a complete open frame (ORF) of 1839 bp. The deduced protein was composed of 612 amino acids, with a predicted molecular weight of 68.93 kDa and an isoelectric point of 6.56, and was predicted to possess F-box and LRRs domains. Combining bioinformatics prediction with subcellular localization experiment analysis, AsCOI1 was appeared to locate in nucleus. AsCOI1 gene was highly expressed in roots and stems, the major organs of agarwood formation. Methyl jasmonate (MeJA), mechanical wounding and heat stress could significantly induce the expression level of AsCOI1 gene. AsCOI1 is an early wound-responsive gene, and it likely plays some role in agarwood formation.

KEY WORDS: Aquilaria sinensis, Agarwood, Coronatine-insensitive protein 1, Rapid-amplification of cDNA ends, Jasmonate, Expression, Subcellular localization

Graphical abstract

This paper characterizes the basic function about AsCOI1 gene including the full-length cDNA sequence cloning, informatics prediction analysis, tissue expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization analysis, and the wounding-induced expression analysis. AsCOI1 gene responded to different stresses; it belongs to an early wound-responsive gene, and it may be playing some role in agarwood formation.

1. Introduction

Agarwood is a non-timber fragrant wood and widely used in perfume, incense and medicine across Asia, Middle East, and Europe1, 2. Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Gilg is one of the most important plant resources for agarwood production in China, as well as the only certified source for agarwood products listed in China Pharmacopoeia3. The formation of agarwood only happens when the tree is wounded, and also as a result of defensive response. The main agarwood compounds are sesquiterpenes and phenylethyl chromone derivatives4, 5, 6, 7. But so far, the wounding-induced molecular mechanism of agarwood formation remains largely unknown.

In plants, jasmonate (JA) is not only a key endogenous plant hormone but also a long-distance transportation wound signal molecule that participates in plant defense responses8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. As reported, the application of exogenous JA to the suspension cells of Aquilaria plants could increase the expression level of δ-guaiene synthases gene and the biosynthetic content of sesquiterpenes4; A. sinensis calli treated with methyl jasmonate (MeJA), an elicitor of plant defensive responses, could cause an increase in sesquiterpene synthase genes (ASSs) expression and four sesquiterpenes production15. Up to now, the general and specific components of JA signaling pathway in Aquilaria tree are not clear yet. We are interested in the relationship between JA signaling pathway and the regulation mechanism of secondary metabolites biosynthesis-related genes in A. sinensis.

Coronatine-insensitive protein 1 (COI1), an F-box protein, interacts with SKP1 and Cullin proteins to form SCF complexes that recruit regulatory proteins targeted for ubiquitination16. In Arabidopsis thaliana, COI1 mediates JA signalling pathway by promoting hormone-dependent ubiquitylation and degradation of transcriptional repressor JAZ proteins liberating the transcription factors to start the transcription of JA-responsive genes16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. GmCOI1, a soybean F-box protein gene, shows ability to interact with Arabidopsis ASK1 and Cullin1 proteins to form SCFCOI1 complex that mediates JA-regulated plant defense and fertility in Arabidopsis23. Similar roles have been reported for COI1 homologs in several other species, including tomato, tobacco and Oryza sativa24, 25, 26, 27, indicating a conserved function of plant COI1. In order to investigate the mechanism of JA signaling pathway in A. sinensis, we cloned A. sinensis COI1 gene, the key factor of JA response pathway. The full-length cDNA sequence of AsCOI1 from A. sinensis was isolated, and its expression patterns responding to MeJA, mechanical wounding and heat were investigated. The results may lay a foundation for further exploring the biological functions of gene and revealing the underlying mechanism of sesquiterpene biosynthesis in A. sinensis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials

A. sinensis trees were grown in a field nursery. Leaves, roots, stems and branches were collected from the four-year-old plants and stored in liquid nitrogen for tissue expression analysis. The well-grown A. sinensis calli were subcultured to the modified Murashige−Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 100 µmol/L MeJA, and incubated for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h in darkness and then sampled. The same well-grown calli were crushed with a pair of metal forceps and cultured for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h in darkness and then sampled as mechanical wounding stress analysis materials. The calli without MeJA treatment or crush wounding treatment were sampled at the same time period and used as control. All samples were quickly poured into liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for analysis. Well-grown A. sinensis suspension cells (100 mL) were placed in shaking water bath with 50 °C and 110 rpm holding for 30 min. After heat treatment, A. sinensis suspension cells were transferred back to shaker at 25 °C and 110 rpm until harvested. Treated suspension cells were sampled by filtration 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 h. The A. sinensis suspension cells that without heat treatment were simultaneously sampled at the same time period and used as control. All samples were removed under sterile conditions, rapidly filtered, and shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. RNA isolation and synthesis of cDNA

Total RNA was extracted using a Tiangen RNA extraction kit (RNAprep pure Plant Kit. Tiangen Biotech Beijing Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer׳s instructions. Quality and quantity of each total RNA sample were assessed in agarose gels (1%, w/v) and spectrophotometricaly at 260 and 280 nm (Bio-Rad, NanoDrop 2000), respectively.

cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription (RT) to transcribe poly(A)+ mRNA with oligo-dT primers using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer׳s instructions. The cDNA was stored at −20 °C for qRT–PCR analysis and gene clone.

2.3. Cloning of AsCOI1 by rapid-amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method

The primers used in this study are showed in Table 1. The first-strand cDNA was used as the template for AsCOI1 core fragment amplication based on the unigenes of 454 data15. Both 5′ and 3′ untranslatable regions (UTRs) of the AsCOI1 were obtained by SMARTerTMRACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, USA), following the manufacturer׳s instructions. The primer 3′-PA and 5′-PA were used as the primer to synthesize 3′ and 5′ first strand cDNA, respectively. The gene-specific primers of the AsCOI1 were designed based on previously cloned fragments. Antisense primers COI1-5′GSP1 and COI1-5′GSP2 were used for synthesizing 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends, and sense primers COI1-3′GSP1 and COI1-3′GSP2 were synthesized for 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. Those primers were all paired with UPM to amplify 5′ and 3′ cDNA ends. The NUP was used as the nested primer. The RACE reaction was performed in a total volume of 50 mL containing 2.5 μL first-strand cDNA, 5 μL Universal Primer Mix (UPM) (10×), 1 μL 10 μmol/L 5′ or 3′ specific primer, 5.0 μL 10× advantage 2 PCR buffer, 2.0 μL 10 μmol/L dNTP mix, and 1.0 μL 50× advantage 2 polymerase mix. Touchdown-PCR reactions were performed at 94 °C (pre-denaturation) for 4 min, followed by 94 °C for 30 s, 70 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 90 s in the first cycle, and the annealing temperature was decreased by 1 °C per cycle. After ten cycles, the conditions were changed to 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 90 s for 20 cycles. The duration of the 72 °C elongation step was 10 min.

Table 1.

Primers for gene cloning and real-time PCR detection.

| Primer purpose | Name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 5′-RACE primers | COI1-5′GSP1 | GCAAGCTCATGAAGCCATTGGCCATC |

| COI1-5′GSP2 | CCTGCAGAACACTCCCTCGCTCCCTAG | |

| 3′-RACE primers | COI1-3′GSP1 | GGAGTACGGGCTCTCCTAAGAGGTTGC |

| COI1-3′GSP2 | GCTTTGGCTGAGGGCTGCCTTGAGCTTG | |

| Full-length CDS cloing | COI1-LF | ATGGAGGAGAGCAGTTACAAG |

| COI1-LR | CCAGTTGGATCCTTTACCGTAA | |

| Reference gene primer | TUA-f | GCCAAGTGACACAAGCGTAGGT |

| TUA-r | TCCTTGCCAGAAATAAGTTGCTC | |

| AsCOI1 RT–qPCR primer | COI1-1f | CATCGTCATCGTCTTCTTCAGG |

| COI1-1r | GAGTCACATAGCCGCCCCA | |

| Universal primer A Mix (UPM) | UPM-Long | CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT |

| UPM-Short | CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC | |

| Nested universal primer A | NUP | AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT |

The PCR products were then subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel for detection and purification. The amplified subjective fragments were cloned into the pGM-T vector (Tiangen). Recombinant plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli, selected by blue/white screening, and verified by PCR. Nucleotide sequencing was performed by Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Service Company, China.

2.4. Isolation and bioinformatics analysis

The sequence encoding AsCOI1 was determined by homology searches in the NCBI databases using the BLAST program, and the homology sequences were downloaded from these databases. The alignment of the AsCOI1 protein with other structurally-related COI1 proteins was performed using the Clustal X program. Some other bioinformatic sequence features of AsCOI1, such as molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI) and stability, were determined as described28. The cNLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) was used to predict the nuclear localization signals29. Conserved motifs of COI1s in A. sinensis and other species were analyzed using Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation (MEME) version 4.9.130 with the following parameters. Optimum motif width was set to ≥6 and ≤50. The conserved residues were analyzed by aligning amino acid sequences using T-coffee31 and by searching literature references. SWISS-MODEL was used to analyze the molecular modeling of AsCOI1 protein32.To determine the relationship between AsCOI1 and other COI1 proteins, phylogenetic analysis was constructed for 16 COI1 proteins of different species using MEGA version 5.05 by the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates33.

2.5. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription–PCR (qRT–PCR)

The tissue-specific expression in roots, stems, leaves and branches of four-year-old A. sinensis plants as well as the AsCOI1expression pattern analysis induced by MeJA, mechanical wounding and heat were analyzed using the qRT–PCR method as described previously28. Briefly, gene-specific forward and reverse primers were designed and synthesized (Table 1). About 15 ng cDNA reversely transcribed from total RNA was used as a template in a 25 mL volume. Tubulin (TUA) was used as a reference gene34. qRT–PCR was carried out in triplicates for each biological sample using the BIORAD iQTM5 system (Bio-Rad). Three fully independent biological replicates were performed. The amplification specificity was assessed by dissociation curve analysis. Gene expression levels were determined using the 2−△△Ct method, where Ct represents the threshold cycle35. Relative amount of transcripts was calculated and normalized as described previously35. The average Cts were log transformed, mean centered and autoscaled36. Standard deviations of the mean value from three biological replicates were calculated as described previously36.

2.6. Subcellular localization analysis

A vector pAN580 containing the open reading frame of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used in this study. The whole coding sequence of AsCOI1 gene was amplified with primers AsCOI1-GFP-F and AsCOI1-GFP-R (Table 1) using Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, USA). The amplification sequence was ligated with Xho I- and BamH I-digested pAN580 vector to generate a AsCOI1-EGFP fusion construct under the control of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S (CaMV 35S) promoter. The construct was confirmed by sequencing and used for transient transformation of onion epidermis via a gene gun (Bio-Rad, PDS-1000, USA). After 24 h of incubation in dark, GFP fluorescence in transformed onion cells was observed under a confocal microscope (OLYMPUS V-TV0.5XC-3, Japan).

3. Resluts

3.1. Molecular cloning of full-length cDNAs and characterization of AsCOI1

Based on the sequences of unigenes from A. sinensis transcriptome data, a full-length cDNA clone was obtained using 5′-/3′-RACE extension methods. Two specific primers COI1-5′GSP1 and COI1-5′GSP2 for 5′-RACE, and COI1-3′GSP1 and COI1-3′GSP2 for 3′-RACE were designed (Table 1) to yield a 651 bp 5′-cDNA ends sequence and a 819 bp 3′-cDNA ends sequence.

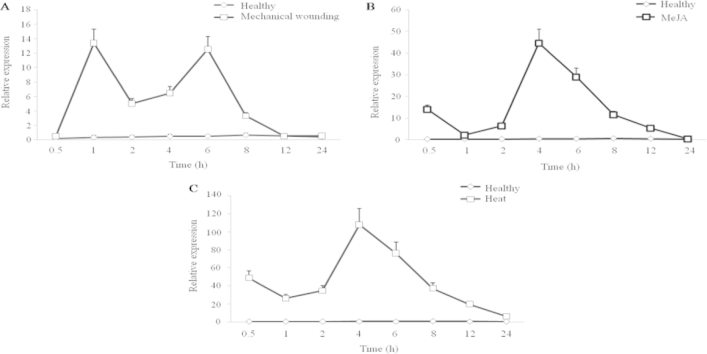

The sequence analysis confirmed that the clone is a COI1 gene. The full-length AsCOI1 comprises 2330 bp, containing a 191-bp 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR), a 300-bp 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR), and a 30-bp polyA. Its ORF is 1839 bp (Fig. 1), encoding a deduced protein of 612 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 68.93 kDa and an isoelectric point of 6.56. The cloned cDNA has been submitted to GenBank under the accession number KM189194.

Figure 1.

The cDNA sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence of AsCOI1. The translation initiation and termination condons are bolded. The characteristic motifs of the AsCOI1 are shown as follows: 4 LRR domains boxed in black; 2 F-box-like domains italic and bold; CGGC domains underlined.

3.2. Bioinformatics analysis of AsCOI1

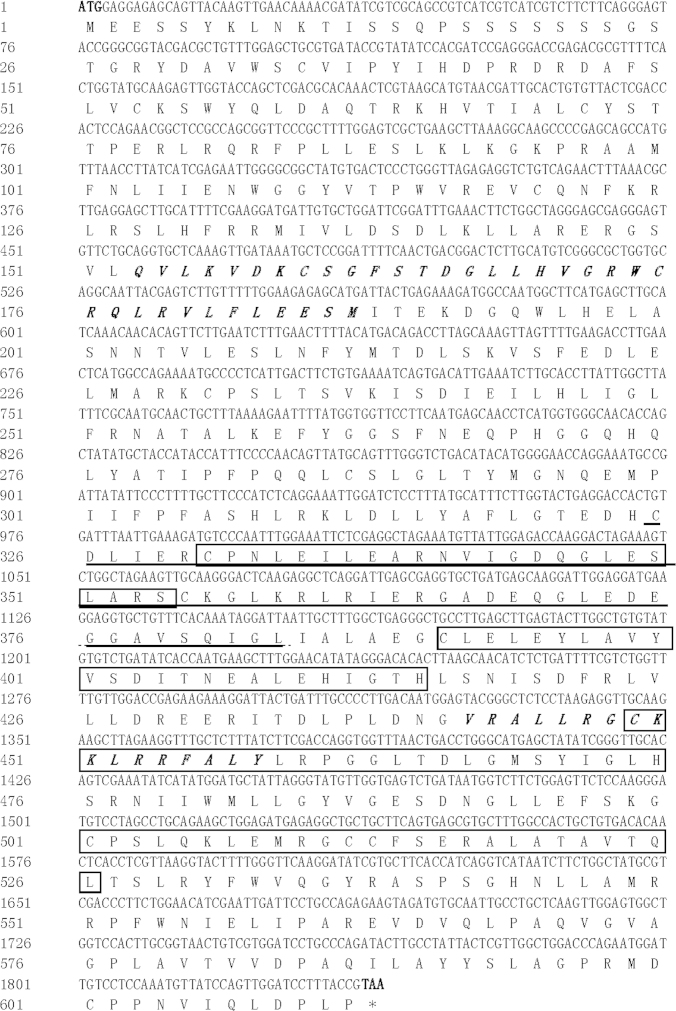

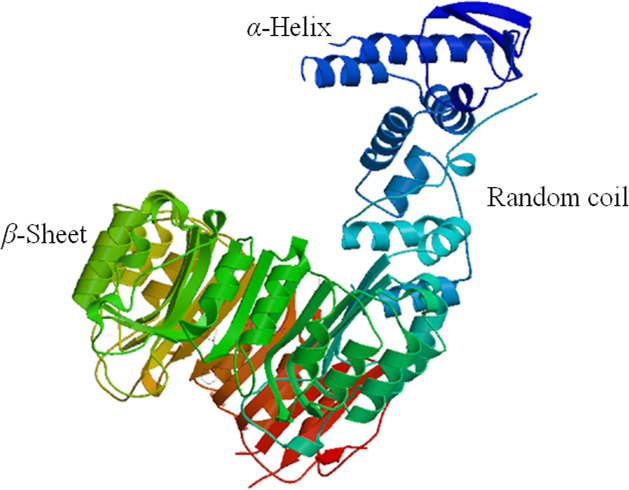

AsCOI1 protein contains 29.25% α-helix, 12.25% β-sheet, and 58.50% random coil, and is hydrophilic with a hydropathy value of −0.108 on average. Nuclear localization signals prediction result showed that AsCOI1 has a nuclear localization signal, suggesting that AsCOI1 might be a nuclear protein, and its location needs more empirical evidence. The search for the conserved domains in AsCOI1 protein against the NCBI Conserved Domain Database and SMART online tools showed that AsCOI1 contains the Leucine-rich repeats (LRR) domain, F-box-like domain and CGGC domain. A three-dimensional structural model was also constructed by SWISS-MODEL (Fig. 2). The MEME motif search tool was used to analyze the conserved motifs of AsCOI1 and COI1 in other species (Fig. 3A). The results revealed three motifs conserved in all the seven lipoxygenases (LOXs). These highly conserved motifs might be associated with the gene function of AsCOI1. The sequence alignment of COI1 proteins from A. sinensis and other species using T-coffee31 showed that AsCOI1 contains the WMLLGYVGESD and GCPSLQKLE signature, the partial sequence of the third motif (Fig. 3B).

Figure 2.

Predicted AsCOI1 3-D mode.

Figure 3.

Conserved motifs and sequences of COI1 proteins in A. sinensis and other species. (A) Conserved motifs identified with the MEME search tool. Motifs are represented by boxes. The numbers (1–3) and different colors in boxes represent motif 1–3, respectively. Box size indicates the length of motifs. Abbreviation: Aquilaria sinensis (A. sinensis), Theobroma cacao (T. cacao), Malus domestica (M. domestica), Prunus mume (P. mume), Vitis vinifera (V. vinifera), Hevea brasiliensis (H. brasiliensis), Cucumis melo (C. melo). (B) Alignment of partial sequences using T-coffee. Consistent sequences are boxed. Different colors represent different alignment qualities: red for the highest, and green for the worst.

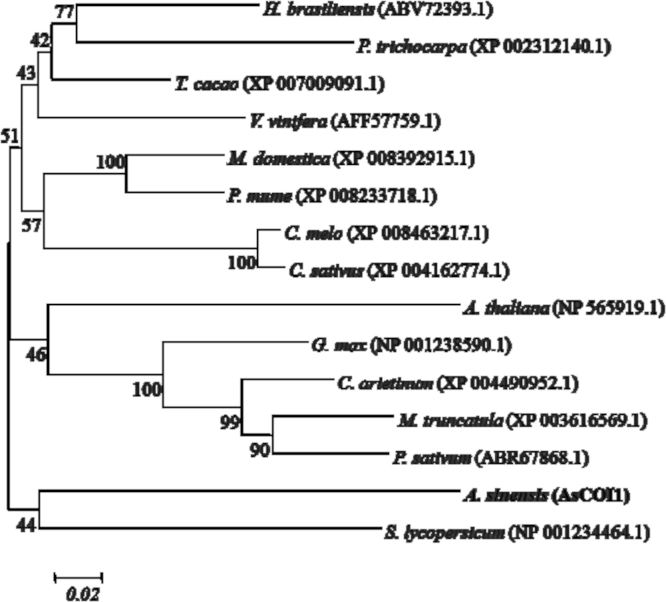

3.3. Homologous alignment and phylogenetic analysis of AsCOI1

To determine the evolutionary relationship among COI1 proteins from A. sinensis and other species, an unrooted neighbor-joining tree was constructed for further identifying the relationships between the AsCOI1 and COI1 protein sequences of other 14 plants already obtained. As shown in Fig. 4, A. sinensis COI1 lined up with Solanum lycopersicum COI1, which indicted that both proteins had similar structures and likely enjoyed some same gene function.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequence of AsCOI1 and other homologues sequences. The relationships were analyzed for deduced full-length amino acid sequences using MEGA 5.05 by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values are shown near the nodes. Abbreviation: Populus trichocarpa (P. trichocarpa), Cucumis sativus (C. sativus), Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana), Glycine max (G. max), Cicer arietinum (C. arietinum), Medicago truncatula (M. truncatula), Solanum lycopersicum (S. lycopersicum).

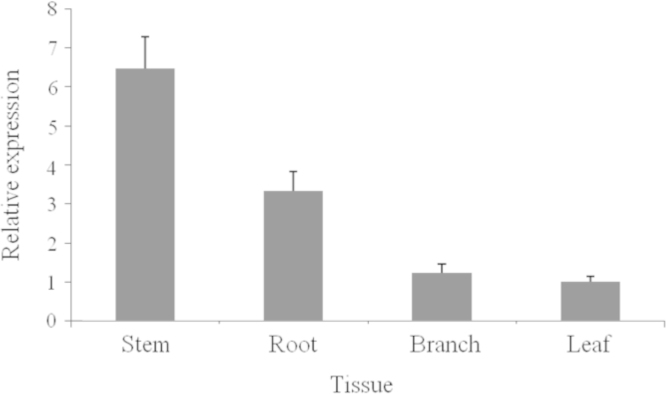

3.4. Tissue-specific expression of AsCOI1 gene

To preliminarily elucidate the function of AsCOI1 gene, we analyzed the expression patterns of the AsCOI1 in roots, stems, leaves and branches of four-year-old and field nursery-grown A. sinensis tree using the quantitative RT–PCR technique. The results showed that AsCOI1 was constitutively expressed in all tested tissues, but at very different levels. The transcription of AsCOI1 gene was the highest in roots, moderate in stems and the weakest in leaves (Fig. 5). The highest transcript of AsCOI1 tested in roots was more than 10 times higher than in leaves.

Figure 5.

The relative expression of AsCOI1 in roots, stems, leaves and branches of A. sinensis. The expression patterns were analyzed by the quantitative RT–PCR method. PCR was carried out in triplicates for each biological sample. Three independent biological replicates were performed. Tubulin (TUA) was used as a reference. Fold changes of AsCOI1 expression were measured. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the mean value of three biological replicates.

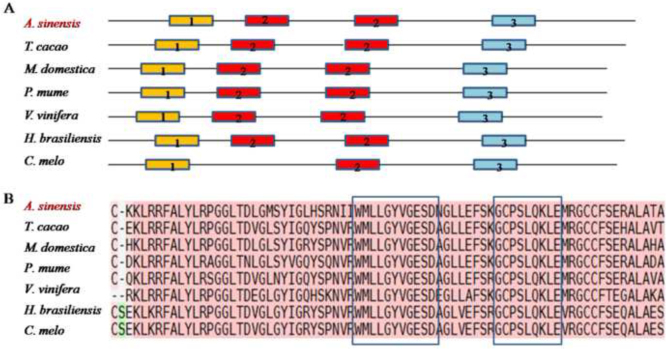

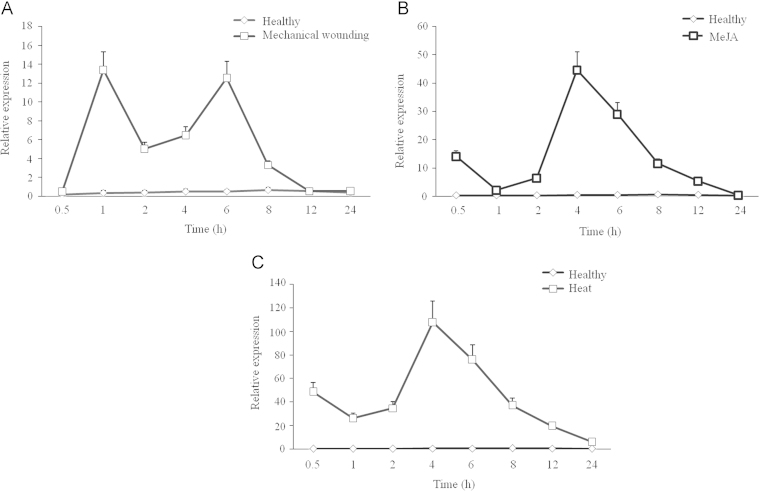

3.5. The response of AsCOI1 to MeJA, mechanical wounding, and heat treatment

To examine the response of AsCOI1 to different stresses, mechanical wounding, MeJA and heat, the level of AsCOI1 transcripts was analyzed using the quantitative RT–PCR method in A. sinensis calli and suspension cells. Results showed that AsCOI1 were positively and significantly induced in all the test stresses (Fig. 6A–C). Generally speaking, the expression level of the AsCOI1 transcripts increased firstly, then decreased, and finally went back to the normal. In mechanical wounding treatment, there appeared a relative higher increase at 1 h about 20 times, and the highest expression level represented at 6 h about 33 times (Fig. 6A). The above results indicated that AsCOI1 might be involved in wound defense in A. sinensis. In MeJA treatment, the relative higher increase was at 0.5 h nearly 40 times of control, and the highest point was at 4 h about more than 80 times compared to the control and declined rapidly to the normal (Fig. 6B). In heat treatment group, there presented a more dramatic rise. The highest increase peak appeared at 4 h about 100 times compared to the control, and decreased back to the normal at 24 h after heat treatment (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

The expression analysis of AsCOI1 gene responding to stresses. (A) Mechanical wounding. (B) MeJA treatment. (C) Heat stress. The expression patterns were analyzed using the quantitative RT–PCR method. PCR was carried out in triplicates for each biological sample. Three independent biological replicates were performed. Tubulin (TUA) was used as a reference gene.

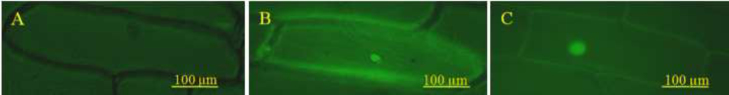

3.6. Localization of AsCOI1

To examine the subcellular localization of AsCOI1, the ORF of AsCOI1 gene was fused to the N-terminal of the GFP reporter gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. The recombinant constructs of the AsCOI1-GFP fusion gene and GFP alone were introduced into onion epidermal cells by gold particle bombardment, respectively. As showed in Fig. 7, the AsCOI1-GFP fusion gene was specifically localized in the nucleus, whereas GFP alone showed ubiquitous distribution in the whole cell. This result indicated that the AsCOI1 protein was localized in the nucleus and may act as binding protein in gene transcriptional regulating.

Figure 7.

Nuclear localization of AsCOI1. (A) Onion epidermis cells. (B) Onion epidermis cells transformed with pGEX-4 T-1 plasmid. (C) Nuclear localization of AsCOI1-GFP. Confocal images of onion epidermis cells under the GFP channel show the constitutive localization of GFP and nuclear localization of AsCOI1-GFP.

4. Discussion

In plants, COI1 gene has been cloned and characterized from Arabidopsis, soybean, tobacco, rubber, and a few other species18, 25, 26, 27, 37, but not from Aquilaria sp. trees. Here, we firstly report on the COI1 gene cloning and characterization. The deduced amino acid sequence of AsCOI1 showed extensive similarity to its counterparts in other species. COI1, the first identified F-box protein, is one of the three components of the SCF complex, which mediates ubiquitination of the proteins targeted for degradation by the proteasome38. In A. thaliana, COI1 is a gene required for JA-regulated defense17. In Nicotiana plants26, 27, the transgenic suppression of Nicotiana COI1 (NtCOI1) homologs results in JA insensitivity of root growth, impaired anther dehiscence, and down-regulated JA-responsive genes; Furthermore, NtCOI1 functions upstream of NtMYB305 and plays a fundamental role in coordinating plant primary carbohydrate metabolism and correlative physiological processes39. In Arabidopsis, the mutation of thylakoid formation 1 (THF1) lead to basal and wound-induced levels of oxylipins increase that stimulate anthocyanin biosynthesis via COI1 signaling40. These results suggest that the COI1-related F-box protein is an essential conserved component of JA signaling pathway in plants secondary metabolism.

In this study, based on the unigene sequence of COI1, we designed specific primers and firstly cloned the full-length cDNA sequence from A. sinensis, named AsCOI1. The deduced AsCOI1 protein was observed to contain 2F-box domains and 4 LRR domains, indicating that this predicted protein belonged to the plant COI1 protein family. Besides that, it also contained a CGGC domain, which was rich in many conserved cysteines and histidines, suggesting that it might has a zinc-binding function. Multiple alignments analysis showed that AsCOI1 had more than 70% sequence identity with the COI1 proteins of several other species, which suggested that COI1 proteins were highly conserved. COI1 proteins were observed to be highly conserved, confirming the high degree of COI1 conservation during the evolution, which reflects the selective pressure imposed by the essential functions of COI1 in plants.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the COI1 gene expression patterns in plants are not identical: some are constitutive type, and some are inducible type. In our experiment, AsCOI1 was expressed mainly in roots and stems, the major organs for agarwood accumulation in Aquilaria plants. This result suggested that AsCOI1 might play an important role in agarwood accumulation. Rice OsCOI1 expression was induced by MeJA and abscisic acid (ABA)41, and the Hevea brasiliensis HbCOI1 was induced by JA and tapping wound42. In this study, the expression of AsCOI1 gene was significantly induced by MeJA and mechanical wounding in A. sinensis calli, and by heat in A. sinensis suspension cells. AsCOI1 more dramatically responded to heat, moderately to MeJA and relative weaker to mechanical wounding. The highest peak pointed at 4–6 h after been treated, and went back to the normal at 12–24 h after been treated. All the above results suggested that COI1 gene probably worked in different way in the JA signal transduction pathway responding to different stresses in plants. Proper responses to JA were dependent on COI1 dosage, and most COI1-dependent JA-responsive genes require COI1 in dose-dependent manner and specific JA responses have different sensitivities to COI1 abundance40. Although JA responses molecular mechanism is already mostly clear in plants, it is completely unclear in A.sp. plants. Consequently, our study on AsCOI1 would help to reveal the relation between the JA signal transduction and the regulated natural agarwood accumulation in Aquilaria defense responses.

5. Conclusions

Here we cloned a lipoxygenase gene (AsCOI1) from A. sinensis trees for the first time. According to the experimental results, the full-length ORF of AsCOI1 is 2330 bp, encoding 612 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight (MW) of 68.93 kDa and an isoelectric point (PI) of 6.56. AsCOI1 belongs to a kind of conservative protein, F-box and LRRs domains. AsCOI1 gene is mainly expressed in roots and stems, but lowest in leaves. AsCOI1 locates in nucleus. The expression of AsCOI1 could be significantly induced by MeJA, mechanical wounding and heat stress in A. sinensis callus. This work may lay a theoretical and experimental foundation for the future research on gene functions, and the transgenic A. sinensis trees with varied AsCOI1 expression will give deeper insight into the AsCOI1 role in A. sinensis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31100220, 81173481 and 31000136), the Program for Xiehe Scholars in Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (No. 282), and the Innovative Team and Innovative Talents Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Persoon GA, Van Beek HH. Growing ʻthe Wood of the Godsʼ: agarwood production in southeast Asia. In: Snelder DJ, Lasco RD, editors. Smallholder tree growing for rural development and environmental service: lessons from Asia. Springer; Netherlands: 2008. pp. 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagura T, Shibayama N, Ito M, Kiuchi F, Honda G. Three novel diepoxy tetrahydrochromones from agarwood artificially produced by intentional wounding. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:4395–4398. [Google Scholar]

- 3.China Pharmacopoeia Committee. The Pharmacopoeia of People's Republic of China (I). Beijing: Chemical Industry Press; 2010, p. 172

- 4.Kumeta Y, Ito M. Characterization of δ-guaiene synthases from cultured cells of Aquilaria, responsible for the formation of the sesquiterpenes in agarwood. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1998–2007. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.161828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen HQ, Wei JH, Yang JS, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Gao ZH. Chemical constituents of agarwood originating from the endemic genus Aquilaria plants. Chem Biodivers. 2012;9:236–250. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HQ, Yang Y, Xue J, Wei JH, Zhang Z, Chen HJ. Comparison of compositions and antimicrobial activities of essential oils from chemically stimulated agarwood, wild agarwood and healthy Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) gilg trees. Molecules. 2011;16:4884–4896. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagura T, Ito M, Kiuchi F, Honda G, Shimada Y. Four new 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromone derivatives from withered wood of Aquilaria sinensis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2003;51:560–564. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer EE, Alméras E, Krishnamurthy V. Jasmonates and related oxylipins in plant responses to pathogenesis and herbivory. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:372–378. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li CY, Schilmiller AL, Liu GH, Lee GI, Jayanty S, Sageman C. Role of β-oxidation in jasmonate biosynthesis and systemic wound signaling in tomato. Plant Cell. 2005;17:971–986. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glauser G, Dubugnon L, Mousavi SAR, Rudaz S, Wolfender JL, Farmer EE. Velocity estimates for signal propagation leading to systemic jasmonic acid accumulation in wounded Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34506–34513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endt DV, Silva MS, Kijne JW, Pasquali G, Memelink J. Identification of a bipartite jasmonate-responsive promoter element in the Catharanthus roseus ORCA3 transcription factor gene that interacts specifically with AT-Hook DNA-binding proteins. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1680–1689. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo AJ, Gao X, Jones AD, Howe GA. A rapid wound signal activates the systemic synthesis of bioactive jasmonates in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;59:974–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang JH, Liu GH, Shi F, Jones AD, Beaudry RM, Howe GA. The tomato odorless-2 mutant is defective in trichome-based production of diverse specialized metabolites and broad-spectrum resistance to insect herbivores. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:262–272. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Allmann S, Wu JS, Baldwin IT. Comparisons of LIPOXYGENASE3- and JASMONATE-RESISTANT4/6-silenced plants reveal that jasmonic acid and jasmonic acid-amino acid conjugates play different roles in herbivore resistance of Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:904–915. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu YH, Zhang Z, Wang MX, Wei JH, Chen HJ, Gao ZH. Identification of genes related to agarwood formation: transcriptome analysis of healthy and wounded tissues of Aquilaria sinensis. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devoto A, Nieto-Rostro M, Xie DX, Ellis C, Harmston R, Patrick E. COI1 links jasmonate signalling and fertility to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;32:457–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie DX, Feys BF, James S, Nieto-Rostro M, Turner JG. COI1: an Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science. 1998;280:1091–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu LH, Liu F, Lechner E, Genschik P, Crosby WL, Ma H. The SCF(COI1) ubiquitin-ligase complexes are required for jasmonate response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1919–1935. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsir L, Schilmiller AL, Staswick PE, He SY, Howe GA. COI1 is a critical component of a receptor for jasmonate and the bacterial virulence factor coronatine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7100–7105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802332105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melotto M, Mecey C, Niu YJ, Chung HS, Katsir L, Yao J. A critical role of two positively charged amino acids in the Jas motif of Arabidopsis JAZ proteins in mediating coronatine- and jasmonoyl isoleucine-dependent interactions with the COI1 F-box protein. Plant J. 2008;55:979–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chini A, Fonseca S, Fernández G, Adie B, Chico JM, Lorenzo O. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2007;448:666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thines B, Katsir L, Melltto M, Niu YJ, Mandaokar A, Liu GH. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2007;448:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang ZL, Dai LY, Jiang ZD, Peng W, Zhang LH, Wang GL. GmCOI1, a soybean F-box protein gene, shows ability to mediate jasmonate-regulated plant defense and fertility in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:1285–1295. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee HY, Seo JS, Cho JH, Jung H, Kim JK, Lee JS. Oryza sativa COI homologues restore jasmonate signal transduction in Arabidopsis coi1-1 mutants. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e52802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Zhao YF, McCaig BC, Wingerd BA, Wang JH, Whalon ME. The tomato homolog of CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 is required for the maternal control of seed maturation, jasmonate-signaled defense responses, and glandular trichome development. Plant Cell. 2004;16:126–143. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paschold A, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Co(i)-ordinating defenses: NaCOI1 mediates herbivore-induced resistance in Nicotiana attenuata and reveals the role of herbivore movement in avoiding defenses. Plant J. 2007;51:79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoji T, Ogawa T, Hashimoto T. Jasmonate-induced nicotine formation in tobacco is mediated by tobacco COI1 and JAZ genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1003–1012. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao FJ, Lu SF. Genome-wide identification, molecular cloning, expression profiling and posttranscriptional regulation analysis of the Argonaute gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza, an emerging model medicinal plant. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:512. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kousugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10171–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900604106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao DQ, Zhou CH, Kong F, Tao J. Cloning of phytoene desaturase and expression analysis of carotenogenic genes in persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) fruits. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:3935–3943. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao ZH, Wei JH, Yang Y, Zhang Z, Zhao WT. Selection and validation of reference genes for studying stress-related agarwood formation of Aquilaria sinensis. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:1759–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willems E, Leyns L, Vandesompele J. Standardization of real-time PCR gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal Biochem. 2008;379:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng SQ, Xu J, Li HL, Tian WM. Cloning and molecular characterization of HbCOI1 from Hevea brasiliensis. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 2009;73:665–670. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulman BA, Carrano AC, Jeffrey PD, Bowen Z, Kinnucan ERE, Finnin MS. Insights into SCF ubiquitin ligases from the structure of the Skp1−Skp2 complex. Nature. 2000;408:381–386. doi: 10.1038/35042620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang WJ, Liu GS, Niu HX, Timko MP, Zhang HB. The F-box protein COI1 functions upstream of MYB305 to regulate primary carbohydrate metabolism in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.cv. TN90) J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2147–2160. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gan Y, Li H, Xie Y, Wu WJ, Li MY, Wang XM. THF1 mutations lead to increased basal and wound-induced levels of oxylipins that stimulate anthocyanin biosynthesis via COI1 signaling in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014;56:916–927. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu TZ, Wang WP, Cao KM, Wang XP. OsCOI1, a putative COI1 in rice, show MeJA and ABA dependent expression. Prog Biochem Biophys. 2006;33:388–393. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng SH, Ma LG, Wang XP, Xie DX, Dinesh-Kumar SP, Wei N. The COP9 signalosome interacts physically with SCFCOI1 and modulates jasmonate responses. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1083–1094. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]