Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is recognized as one of three gasotransmitters together with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO). As a signaling molecule, H2S plays an important role in physiology and shows great potential in pharmaceutical applications. Along this line, there is a need for the development of H2S prodrugs for various reasons. In this review, we summarize different H2S prodrugs, their chemical properties, and some of their potential therapeutic applications.

KEY WORDS: Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), Gasotransmitters, H2S prodrugs, H2S-hybrid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Controllable H2S prodrugs, Hydrolysis-based H2S prodrugs

Graphical abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is recognized as one of three gasotransmitters together with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO). As a signaling molecule, H2S plays an important role in physiology and shows great potential in pharmaceutical applications. Along this line, there is a need for the development of H2S prodrugs for various reasons. In this review, we summarize different H2S prodrugs, their chemical properties, and some of their potential therapeutic applications.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a well-known lethal, toxic gas with the smell of rotten eggs, is recognized as one of the three gasotransmitters in mammals, which also include nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO)1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The literature evidence suggests that hydrogen sulfide possesses the following activities: anti-inflammatory7, 8, 9, anti-tumor10, ion channel regulation11, 12, 13, cardiovascular protection14, 15, 16 and antioxidation17. However, the exact role that hydrogen sulfide plays depends on the specific circumstance, its concentration, and the interplays with other signaling molecules, especially NO and CO18. This is a major area of research in developing hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics, but is beyond the scope of this review. Another major issue is finding appropriate ways of delivering hydrogen sulfide to the relevant location, at the right concentration, and with the appropriate pharmacokinetics. Much of this issue stems from the fact that it is unrealistic to use gaseous hydrogen sulfide itself or its salt such as sodium sulfide in therapeutic applications in human. Thus there is a great deal of interest in searching for appropriate hydrogen-sulfide-releasing agents, which are commonly referred to as H2S donors or prodrugs. This review provides a summary of developments in this field mostly during the last five years with a focus on the chemistry concepts19.

1.1. H2S chemistry

H2S is a weak acid and soluble in water (up to 80 mmol/L at 37 °C20). The pKa values (37 °C) for the first and second dissociation steps are about 6.88 and 19, respectively21. Under physiological conditions (pH=7.4), H2S largely exists in two forms: the neutral molecular form (H2S) and an ionic form (HS−) (Scheme 1). S2− is a very minor component simply because of the second pKa being very high. However, the bioactive form is still unknown, and the term H2S is usually used referring to the total sulfide species. Although H2S has good solubility in water, it is still very unstable in solution. It is easy oxidized in the presence of oxygen. In addition, the volatility of hydrogen sulfide adds complications to experiments. For example, half of the dose of H2S could be lost in 5 min from open cell culture wells22. H2S concentration can decrease so rapidly that the precise measurement of H2S concentration is a great challenge in this field23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28.

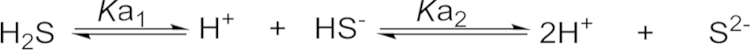

Scheme 1.

Hydrogen sulfide disassociation19, where pKa1=6.88, and pKa2=19.

1.2. H2S biology

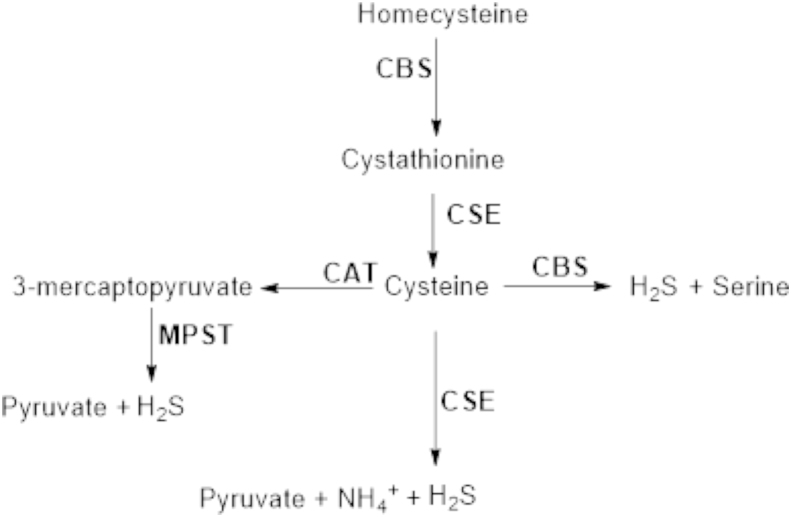

In mammals, three enzymes are involved in sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism and thus responsible for the in vivo production of H2S. Two of them are pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes: cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE). CBS is expressed predominantly in the central nervous system (CNS)29. Relatively high concentrations (47 μmol/L to 166 μmol/L) of H2S have been observed in the brains of mammals30, 31, 32. The normal cellular function of CBS is in the trans-sulfuration pathway, catalyzing the condensation of homocysteine with serine to form cystathionine. In the 1980s, CBS isolated from rat liver and kidney was reported to produce H2S from cysteine33. In contrast to CBS, CSE is mainly responsible for the production of H2S outside of the CNS7. CBS and CSE share a common feature of catalytic promiscuity. The relative contributions of CBS and CSE to H2S generation at low homocysteine concentration are about 7:3. However, CBS activity is confined to chemical transformations at the β-position34, while CSE is proficient at catalyzing reactions at the β- and γ-carbons of substrates35. Furthermore, because homocysteine appears to be unable to bind to the site at which the external aldimine with PLP is formed in CBS, CSE׳s contribution to the H2S pool is increased under conditions of moderate and severe hyperhomocysteinemia. A third H2S-producing enzyme, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST), was thought to exist, as H2S was not depleted in CBS knockout mouse brain36. 3MST, a PLP-independent enzyme, is localized in the neurons in the brain along with cysteine aminotransferase (CAT), while CBS is localized in the astrocytes, a type of glia, in the CNS. 3MST and CAT are also found in the vascular endothelium. CAT catalyzes the reaction of l-cysteine with α-ketoglutarate to form 3-mercaptopyruvate (3MP), which is further catalyzed by 3MST to generate H2S in the presence of thiol and reducing agents (Fig. 1)37. Overall, H2S production in mammals is intimately connected to the metabolic pathways of sulfur containing amino acids. The PLP-dependent trans-sulfuration pathway, which contains both CBS and CSE for H2S production, is localized in the cytosol. H2S synthesis via CAT and 3MST occurs in the cytosol and mitochondria.

Figure 1.

Enzymatic pathways of H2S production in mammalian cells.

2. H2S prodrugs

In the past several years, many series H2S prodrugs have been developed. They could be divided into three general classes: plant-derived natural products, hydrolysis-based H2S prodrugs, and controlled-release H2S prodrugs.

2.1. Plant-derived natural products

Allium vegetables, represented by garlic and onions, have long been considered as salubrious foods that have anti-inflammatory functions, and their active ingredients have been shown to reduce the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases38, 39, 40. It was not until 2007 that studies from Kraus׳ group showed that the vasoactivity of garlic compounds was correlated with H2S production41, which suggested that the major beneficial effects of allium vegetable diets are mediated by the biological production of H2S from organic polysulfides.

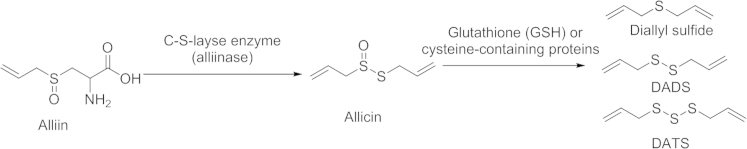

To date, several sulfur-containing components from garlic or garlic preparations have been identified (γ-glutamylcysteines and alliin in the intact garlic; ajoene and allyl mercaptan in the steam-distilled garlic oil; S-allyl-cysteine and S-allyl-mercaptocysteine in the aged garlic extract; and methiin in the garlic homogenate). Among all the different components, only three of them, S-allyl-cystein (SAC), diallyl disulfide (DADS), and diallyl trisulfide (DATS) have been shown to have pharma cological effects, which are correlated with the H2S signaling pathway41, 42. DADS and DATS are major components of garlic oil43, and are derived from allicin, which is unstable in water (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Sulfur-containing compounds in intact garlic resulting from conversion of amino acid alliin.

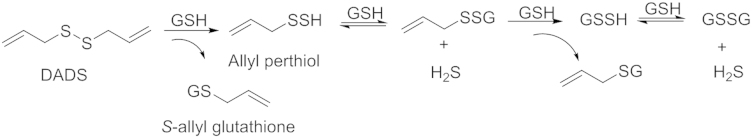

Organic polysulfides DADS and DATS act as H2S donors when they react with biological thiols including GSH, or by human red blood cells via glucose-supported reactions. It is proposed that DADS undergoes nucleophilic substitution at the α-carbon and yield a key intermediate allyl perthiol to form H2S (Scheme 3). The chemical conversion of organic polysulfides to H2S is facilitated by allyl substituents and dependent on the number of tethering sulfur atoms. Another study of DADS found that the hepatocyte cytotoxicity of DADS might be attributed to the inhibition effect of H2S on cytochrome oxidase44, suggesting biological production of H2S from DADS.

Scheme 3.

Proposed H2S production from DADS by reactions involving thiol.

The third sulfur-containing compound in allium vegetables related to H2S production is S-allyl-cysteine (SAC), a reduced form of alliin, which is the major component in aged garlic extract. Studies from Zhu′s group42, 45 showed that SAC and CR-SPRC, a cysteine analog of SAC, upregulated CSE expression and increased plasma H2S concentrations. Rats used in an acute myocardial infarction and heart failure model were treated with SAC or CR-SPRC, respectively. It was found that SAC and its analog significantly lowered mortality and improved cardiac function. The activity of CSE, CAT, GSH, and plasma H2S concentration were increased in SAC-pretreated and CR-SPRC-treated rats, suggesting its cardioprotection effect via a H2S-mediated pathway. However, there is no report on H2S production directly from SAC in the biological systems.

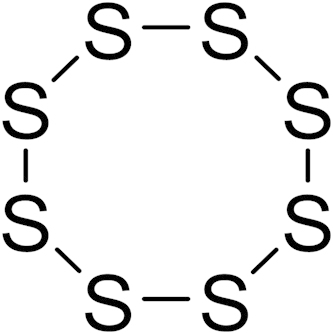

Recently, Kondo et al.46 published a H2S prodrugs: SG-1002 (Fig. 2), which is a polysulfur mixture containing 92% α sulfur, 7% sodium sulfate and a trace amount of other sulfur derivatives. In one study, SG-1002 was administered to C57BL/6J or CSE knockout mice to investigate the effects of genetic modulation of CSE and exogenous H2S in a pressure overload-induced heart failure model. It was found that CSE knockout mice exhibited significantly greater cardiac dilatation and dysfunction than wild-type mice after transverse aortic constriction, and cardiac-specific CSE transgenic mice maintained cardiac structure and function after transverse aortic constriction. H2S afforded by SG-1002 could upregulate the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-Akt-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-nitric oxide (no)-cGMP pathway with preserved mitochondrial functions, attenuated oxidative stress, and increased myocardial vascular density. The results show oral H2S therapy prevents the transition from compensated to decompensated heart failure in part via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and increased nitric oxide bioavailability. However what needs to be noted concerning these studies is that the mechanism of H2S release from SG-1002 is not described. More studies are needed to prove the correlation of H2S production and the observed pharmacological effects.

Figure 2.

The structure of α sulfur in SG-1002.

2.2. Hydrolysis-based H2S prodrugs

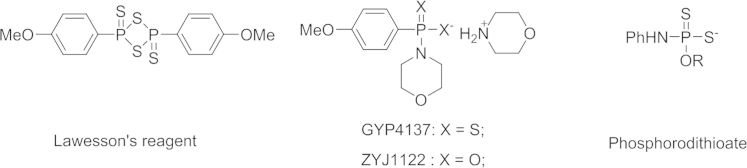

Hydrolysis-based H2S prodrugs primarily consist of four classes of analogs: namely, inorganic sulfite salts including NaHS, Na2S and CaS; Lawesson׳s reagent and analogs; 1,2-dithiole-3-thiones (DTTs); and arylthioamides derivatives. For arylthioamides derivatives, some classified them as thiol-activated H2S donors. Since these compounds are easily hydrolyzed to generate H2S in PBS buffer, they are summarized in this section.

2.2.1. Inorganic sulfite salts

NaHS and Na2S are two widely used H2S donors in basic research. Upon hydrolysis, both compounds could generate H2S quickly in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). In aqueous state under physiological pH, the ratio of HS−/H2S is around 3:119, 47.

NaHS and Na2S have been extensively used in studying the biological effect of hydrogen sulfide. For example, in an ovalbumin-treated rat model48, NaHS treatment could increase peak expiratory flow (PEF), and decrease goblet cell hyperplasia, collagen deposition score, the total cells recovered from bronchoalveolar fluid, and influx of eosinophils and neutrophils. Additionally, administration of NaHS also significantly attenuated activation of pulmonary inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Those results suggested that H2S possessed anti-inflammatory and anti-remodeling effect in asthma pathogenesis, presumably by the cystathionine-gamma-lyase (CSE)/H2S pathway. Using NaHS as a H2S donor, Du et al.8 examined the possible role of H2S in the pathogenesis of oleic acid (OA)-induced acute lung injury (ALI) and its regulatory effects on the inflammatory response. Intraperitoneal injection of NaHS (56 µmol/L) into OA-treated rats increased the pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood (PaO2), reduced the lung wet/dry ratio and alleviated the degree of ALI. Additionally, NaHS decreased inflammatory cytokine such as IL (interleukin)-6 and IL-8 levels and increased anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels in the plasma and lung tissues. Similarly, Na2S inhibited IL-1β levels and significantly increased anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels in an acute lung injury model49.

In addition to anti-inflammatory effect, NaHS or Na2S also showed pro-inflammatory50, 51, 52, ion channel regulation11, 12, cardiovascular53, and neurogenic regulation54 effects. Although NaHS and Na2S presented promising biological results both in vitro and in vivo, the likelihood of their use in clinical applications is small due to reasons such as release kinetics, smell, lack of ability to target, and difficulty in controlling its concentration because of hydrogen sulfide׳s volatility. Nevertheless, encouragingly, a sodium sulfide solution (IK-1001) for intravenous injection has successfully completed a phase I clinical trial, thus pointing to the possibility of applications in well-defined situations4.

Another potential inorganic H2S donor is calcium sulfide (CaS), which is one of the effective components in a traditional medicine, hepar sulphuris calcareum55. Compared to NaHS and Na2S, CaS is chemically more stable. However, there is only limited information on the effectiveness of CaS as H2S donor56.

2.2.2. Lawesson׳s reagent and analogs

Lawesson׳s reagent, which is widely used for sulfurization in organic synthesis57, also releases H2S upon hydrolysis, and it has been used as a H2S donor in some studies. Compared to inorganic sulfide, the release rate with Lawesson׳s regent is much slower. After incubation of Lawesson׳s reagent in buffer or rat liver homogenate for 60 min, the conversion to H2S was about 18% or 11%, respectively58. In work by Medeiros et al.59, Lawesson׳s reagent was used as H2S donor to evaluate its protective effect against alendronate (ALD)-induced gastric damage in rats. In this study, Lawesson′s reagent was orally administrated once daily for 4 days. Induction of gastric damage by ALD (30 mg/kg) was seen 30 min after ALD administration. The results showed that pretreatment with Lawesson׳s reagent (27 µmol/kg) attenuated ALD-mediated gastric damage, reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, and malondialdehyde formation; lowered myeloperoxidase activity; and increased the level of GSH in the gastric tissue. All those results suggested that Lawesson׳s reagent plays a protective role against ALD-induced gastric damage by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels. In another study60, Lawesson׳s reagent also attenuated ethanol-induced macroscopic damage in a dose-dependent fashion. However, Lawesson׳s reagent also releases H2S spontaneously upon hydrolysis in aqueous solution, and it suffers from poor water solubility, which may pose a limit for its further applications.

GYY4137, a water-soluble derivative of Lawesson׳s reagent, could also release H2S upon hydrolysis16. Compared to Lawesson׳s reagent and sulfide salts, it can generate H2S at a slower rate. With the use of the H2S microelectrode or the DTNB (5, 5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) assay, it was found that incubation of GYY4137 in aqueous solution (pH 7.4, 37 °C) resulted in the release H2S, and the concentration of H2S peaked at around 6–10 min, and remained at a low level (<10 µmol/L) over a sustained period of 100 min. In one experiment, the administration of GYY4137 (133 µmol/kg i.v. or intraperitoneal) to anesthetized rats could also boost the concentration of H2S in plasma to around 75 µmol/L at the 30 min point, and the concentration remained elevated (above 40 µmol/L) for more than 180 min. Additionally, GYY4137 did not cause any significant cytotoxic effect, or alter the cell cycle profile or p53 expression of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. However, NaHS was previously reported to induce apoptotic cell death of cultured fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. The differences in the safety profile between GYY4137 and NaHS may be attributed to the differences in H2S release rate and the concentration of H2S generated.

In work published by Liu et al.61, GYY4137 was employed as a H2S donor to investigate its effects on CVB3-induced myocarditis and possible underlying mechanisms. The results showed that GYY4137 suppressed CVB3-induced secretion of enzymes implicated in cardiocyte damage including LDH, CK-MB, and decreased the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6. Moreover, GYY4137 also inhibited the activation of NFκB and the IκBα degradation induced by CVB3. Notably, the phosphorylation of p38, ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 induced by CVB3 was also suppressed by GYY4137. Taken together, GYY4137 exerted its anti-inflammatory effect in CVB3-infected cardiomyocytes, which was possibly associated with H2S generation by GYY4137. The anti-inflammatory mechanism may be associated with the inhibition of NFκB and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway.

Additionally, at a concentration of 400 or 800 µmol/L, GYY4137 also showed some anti-cancer effect with 30%–70% death in seven different human cancer cell lines (HeLa, HCT-116, Hep G2, HL-60, MCF-7, MV4-11 and U2OS)62 and no effect on the survival of normal human lung fibroblasts (IMR90, WI-38). In contrast, NaHS did not showed any anticancer effect (400 µmol/L), and only showed less potent growth inhibition (15%–30%, 800 µmol/L). The author attributed such difference to the different H2S release rate between GYY4137 and NaHS. Incubation of GYY4137 (400 µmol/L) in culture medium released low concentrations (<20 µmol/L) of H2S, with the concentration sustained over a period of 7 days. In contrast, incubation of NaHS (400 µmol/L) in the same way led to much higher concentrations (up to 400 µmol/L) of H2S with a much shorter duration (1 h). It is well-known that the effect of H2S is concentration-dependent with high concentrations (above 250 µmol/L) being toxic63, thus it is easy to understand that release kinetics and peak concentration would make much difference to the overall effect of a H2S donor. The in vivo antitumor effect of GYY4137 was also evaluated. In a xenograft mice model (HL-60 and MV4-11 cells), GYY4137 could significantly inhibit tumor growth at dosages of 100–300 mg/kg/day.

Despite all the success described above, other independent studies sometimes showed opposite effect when NaHS was used as a donor. For example, H2S in the form of NaHS showed protective effect for colon cancer cells64, increased proliferation of colon cancer cells, and reduced apoptosis in several cell lines65. These disparate observations may be due to the use of different H2S donors, which release H2S at different rates, give different byproducts, and have different peak concentrations. Although ZYJ1122 (Fig. 3), an analog of GYY4137 lacking sulfur, was inactive in all cancer cell lines tested, it is unclear what byproducts GYY4137 would generate in cells, because the metabolism for GYY4137 is expected to be complicated. Additionally, it should be kept in mind that the percentage of hydrolysis for GYY4137 is low, which means that the majority of GYY4137 remained in the cells. Since relatively high concentrations of GYY4137 was used (400 and 800 µmol/L), it is entirely possible that the observed anticancer effect may be caused by GYY4137 itself or its metabolism products, and not necessarily the released H2S. The convoluted situation with the observed effects of “H2S” is a strong indication that future experiments need to be benchmarked against a standard and standard conditions with careful control and documentation of concentrations.

Figure 3.

The chemical structures for Lawesson׳s reagent-based H2S donors.

In order to tune the H2S release capability of GYY4137, structural modifications on the phosphorodithioate moiety were made to GYY4137 to afford a series of O-substituted phosphorodithioate-based H2S donors (Fig. 3)66. Their H2S releasing properties were evaluated by fluorescence methods. After incubation (100 µmol/L) in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) for 3 h at room temperature, N,O-diarylated donors and GYY4137 could release H2S with a final concentration of around 800 nmol/L. However, the O-alkylated donors showed very weak H2S production (data not shown in the paper). The protective effects of N,O-diarylated donors against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in H9C2 cells were investigated. Specifically, the donors were incubated with the cells for 24 h before H2O2 was added. Then cell viability was determined by the CCK-8 assay after incubation for another 5 h. The results showed that in the absence of a H2S donor, cell viability decreased by about 65%. In the presence of H2S donors (N,O-diarylated donors, GYY4137 and NaHS), a much higher level cell viability was observed, especially for one N,O-diarylated donor, which increased the cell viability to about 95% at the concentration of 100 µmol/L. These results suggested that the H2S donors did present protective effects against oxidative injury. As mentioned above, the biological results obtained for these donors should be carefully associated with the generation of H2S. Further experiments may be needed to clarify this.

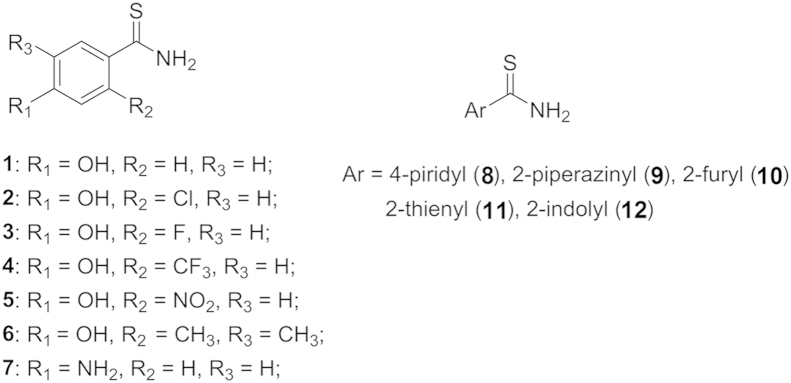

2.2.3. Arylthioamides derivatives

A series of arylthioamides were synthesized by Vincenzo Calderone et al.67, and their H2S release properties were evaluated. The synthesized compounds were incubated with or without l-cysteine in PBS buffer at 37 °C, and H2S release was recorded by amperometry. The results showed that compounds 1–3 (Fig. 4) did not generate a detectable level of H2S (<2 µmol/L) in the absence of l-cysteine; however, they did release H2S in the presence of l-cysteine with Cmax of about 10 µmol/L. For compounds 4 and 5 with strong electron-withdrawing substituents, no detectable levels of H2S were observed with or without l-cysteine. Based on those results, it seems that the H2S release mechanism for arylthioamides is thiol-activated, and Xian et al.68 did classify arylthioamides as thiol-activated H2S donors. However, some analogs in this series also generated detectable amounts of H2S in the absence of l-cysteine, especially compound 12, which did not show any difference in the amount of H2S released with or without l-cysteine. It is well characterized that hydrolysis of thioacetamide would lead to H2S formation. So it could be concluded that the hydrolysis of arylthioamides could also give H2S. Actually, Wallace et al.69 classified these compounds as hydrolysis-based H2S donors. It may be more reasonable to say that both mechanisms contribute to H2S generation because there is no clear evidence to exclude either.

Figure 4.

The chemical structures for arylthioamides.

After confirmation of H2S release from arylthioamides, compound 1 was chosen for further pharmacological studies. It strongly abolished the noradrenaline-induced vasoconstriction in isolated rat aortic rings and hyperpolarized the membranes of human vascular smooth muscle cells in a dose-dependent fashion. After oral administration of compound 1, the systolic blood pressure of the animals was significantly reduced. These findings make arylthioamides promising H2S donors for further study.

No matter what the H2S release mechanism for arylthioamides is, it should be noted that incubation of 1 mmol/L of the donors only release H2S with a Cmax value of about 10 µmol/L, which means that the major species in solution is still the donor itself. Thus it is still premature to associate the observed bioactivities with the generation of H2S alone, because the bioactivities may be caused by the donor itself or a combination of various species. Actually, this issue is quite common among the organic H2S donors. More detailed and well-designed control experiments are needed to address this issue.

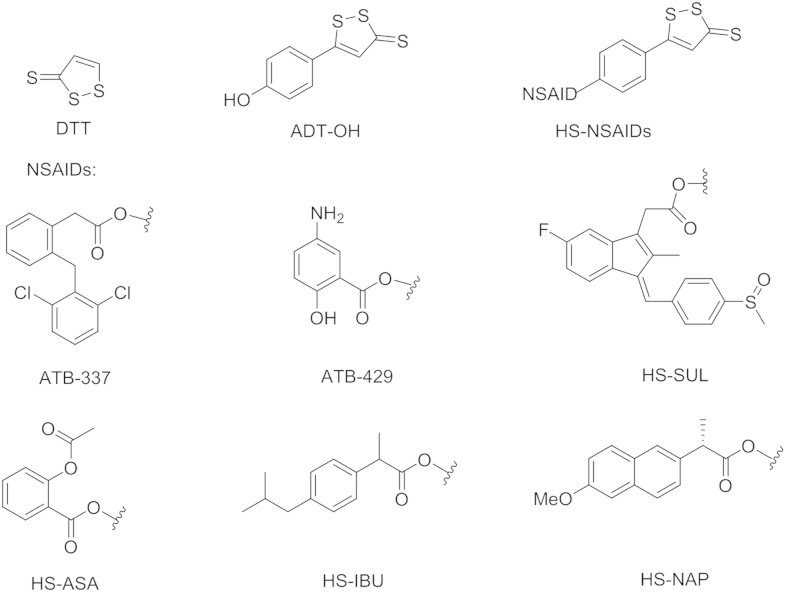

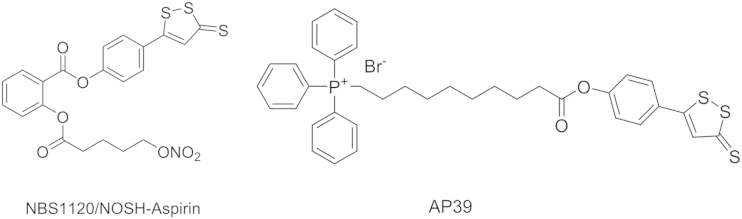

2.2.4. 1,2-Dithiole-3-thiones and H2S-hybrid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

1,2-Dithiole-3-thiones (DTT) has also been used as a H2S donor. Although its H2S-release mechanism is still not fully clarified, it is widely accepted that hydrolysis is part of the underlying mechanism for the generation of H2S from DTT57.

The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) suffers from unacceptable risk of gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding70, 71, 72, 73. In order to reduce such side effects, DTTs have been conjugated to NSAIDs to form HS-hybrid NSAIDs (HS-NSAIDs, Fig. 5), which showed significant reduction of gastrointestinal damage compared to the parent NSAIDs73, 74. In addition, HS-NSAIDs also boosted the anti-inflammatory effect of their NSAIDs counterparts. In a work by Fiorucci et al.75, DTT was conjugated to diclofenac to afford a HS-NSAID-hybrid ATB337, and its anti-inflammatory effect was investigated along with diclofenac in rats. In a rat air pouch model, orally administrated ATB-337 dose-dependently suppressed the activity of both COX-1 and COX-2, and the efficiency was comparable to that of the diclofenac. Additionally, pretreatment with ATB-337 and diclofenac led to a reduction of carrageenan-induced paw swelling volume. Notably, pretreatment with ATB-337 at 10 µmol/kg achieved a reduction in edema formation comparable to that seen with diclofenac at 30 µmol/kg. This enhanced potency was probably associated with the generation of H2S from ATB-337.

Figure 5.

The chemical structures for HS NSAID hybrids.

An enhanced anti-inflammatory effect was also observed for ATB-42976. In addition to their anti-inflammatory effect, other HS-NSAIDs including HS-sulindac (HS-SUL), HA-aspirin (HS-ASA), HS-ibuprofen (HS-IBU), and HS-naproxen (HS-NAP), were also reported to exhibit anti-proliferative effect against human colon, breast, pancreatic, prostate, lung, and leukemia cancer cell lines. The conjugation with 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2-dithiol-3-thione (ADT-OH) significantly increased the growth inhibitory effect of NSAID by 28- to >3000-fold77.

Along the line of NSAID׳s antiproliferation effect, Kashfi et al.78 prepared a compound NBS-1120 (Fig. 6), which could release NO, H2S and aspirin at the same time. NBS-1120 inhibited HT-29 colon cancer growth with IC50 values of 45.5±2.5, 19.7±3.3, and 7.7±2.2 nmol/L at 24, 48, and 72 h time points, respectively. This is the most potent NSAID-based anticancer agent so far. Mechanistic studies showed that NBS-1120 induced apoptosis, and arrested the cells at G0/G1 phase. NBS-1120 also showed promising in vivo antitumor effect. It significantly inhibited tumor growth by 85% in mice bearing a human colon cancer xenograft.

Figure 6.

The chemical structure for NBS112079 and AP39.

Accumulating evidence supports that H2S plays a vital role in the modulation of mitochondrial cell death pathways and in the regulation of cellular bioenergetics3, 4, 80. Multiple studies revealed that H2S donors help maintain mitochondrial integrity, reduce the release of mitochondrial death signals, and attenuate mitochondrially-regulated cell death responses of various types79, 81, 82. Szabo et al.83 prepared a compound AP39 (Fig. 6) with two moieties: ADT-OH for H2S generation and triphenylphophinium (TPP) for mitochondrial targeting. Cell imaging studies confirmed that AP39 was primarily internalized in mitochondria84. After confirming the mitochondria-targeting H2S delivery, compound AP39 was employed to investigate its effect on bioenergetics, viability, and mitochondrial DNA integrity in bEnd.3 murine microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. At a concentration of 100 nmol/L, incubation of AP39 with bEnd.3 cells caused an increase in basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR), which represented respiratory reserve capacity, a key bioenergetic parameter. Meanwhile, AP39 (30 and 100 nmol/L) could also induce an increase in FCCP (carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone)-stimulated OCR. However, when the concentration of AP39 was increased to 300 nmol/L, an inhibitory effect was observed instead. AP39 could also attenuate the loss of cellular bioenergetics during oxidative stress caused by glucose oxidase. Additionally, Co-treatment of ADT-OH with TPP targeting moiety did not show any antioxidant or cytoprotective effect in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells even at a concentration of 300 nM, which is attributed to its inability to enter mitochondrial compartment. In contrast, ADT-OH without the TPP targeting moiety did not show any antioxidant or cytoprotective effect in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells even at a concentration of 300 nmol/L, which is attributed to its inability to enter mitochondrial compartment. In summary, the various mitochondrial effects observed for AP39 are consistent with the role of H2S in the regulation of mitochondrial function.

Although DTT and its NSAID hybrids showed promising H2S-related bioactivities both in vitro and in vivo, it is still unclear how those agents release H2S in vivo. Hydrolysis for sure partially contributes to the release of H2S from DTT. Because of the presence of disulfide bonds in DTT, thiols could also activate DTT through reduction to release H2S. Therefore, further experiments are needed to elucidate its H2S release mechanism.

2.3. Controllable H2S prodrugs

The goal of controllable H2S prodrugs was to develop H2S prodrugs, which are stable in aqueous solutions and during sample preparation85. The prodrugs can release H2S in the presence of triggers, which could be enzymes, pH, biomolecules, UV-light, and others. However, this is still a great challenge in this field. Currently, there are three examples: thiol activation, light activation, and bicarbonate activation.

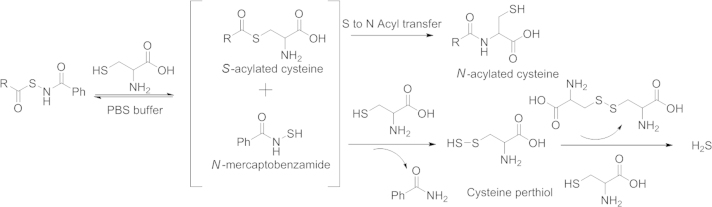

2.3.1. Thiol activation

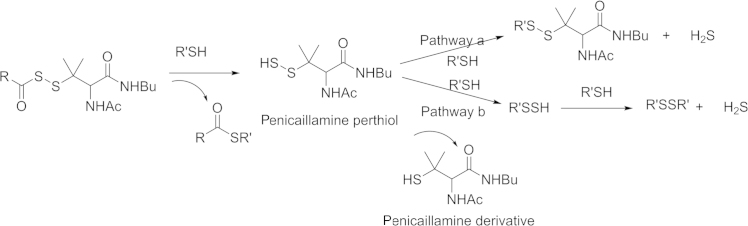

In 2011 Xian׳s group85 developed the first thiol activated H2S prodrugs: N-mercapto (N-SH)-based derivatives. The strategy was based on the instability of the N-SH bond. The thiol group was first protected with acyl groups, and then the protected nitrogen-sulfur bond could be stable to some degree. In the presence of thiol species in the biological system, H2S release can be triggered through reduction. A detail mechanism is shown in Scheme 4. The prodrug is first activated by thiol exchange between a thiol species (cysteine or GSH) and the prodrug to generate S-acylated cysteine and N-mercaptobenzamide. Then one of the intermediates, N-mercaptobenzamide, reacts with cysteine to form cysteine perthiol, which is followed by interaction with cysteine to release H2S. In this mechanistic study, the Xian's group found that perthiol could also be a key intermediate in H2S generation. In 2013, Xian׳s lab86 published a series of perthiol-based H2S prodrugs, with a release mechanism similar to that of the previous example. Briefly, thiol exchange initiates the reaction to form penicillamine perthiol intermediate, which is followed by thiol attack again to produce either a disulfide and H2S (Scheme 5, pathway a,), or a new perthiol, which would interact with another thiol species to release H2S (Scheme 5, pathway b).

Scheme 4.

Proposed N-SH H2S prodrugs H2S releasing mechanism.

Scheme 5.

Proposed perthiol H2S prodrugs H2S releasing mechanism.

To show the therapeutic potential of perthiol H2S prodrugs, Xian׳s laboratory also tested the protective effect of these prodrugs against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury in a murine model system, since H2S was proven to show such effects. In these experiments, mice were subjected to 45 min left ventricular ischemia followed by 24 h reperfusion. Then prodrugs or vehicles were administered into the left ventricular lumen at 22.5 min of myocardial ischemia. Compared to vehicle-treatment alone, mice treated with prodrugs displayed a significant reduction in circulating levels of cardiac troponin I and myocardial infarct size per area-at-risk, suggesting that perthiol H2S prodrugs indeed exhibit cardiac protection in MI/R injury. It should be noted that the reaction between prodrugs and cysteine yields many reactive sulfane sulfur species. Therefore, further studies on H2S-related and sulfane sulfur-related mechanisms are still needed.

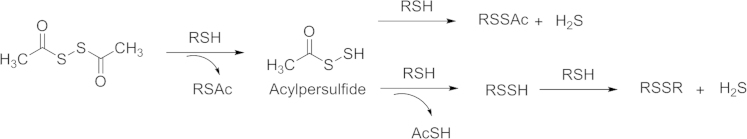

Based on similar strategies, Calderone and coworkers87 reported dithioperoxyanhydride as a thiol-activated H2S prodrugs in 2013. The acylpersulfides were proposed to be key intermediates. The H2S-releasing mechanism is the same as that of perthiol H2S prodrugs (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Proposed dithioperoxyanhydride H2S releasing mechanism.

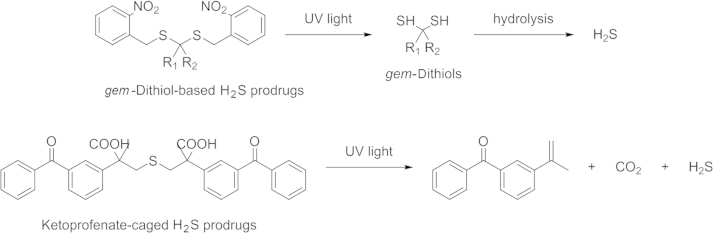

2.3.2. Photo-induced H2S prodrugs

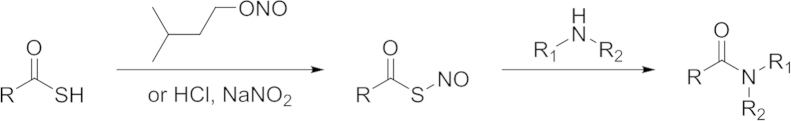

The second type of controllable H2S prodrugs is light-activated H2S prodrugs. Recently, there have been two example published. The first one is gem-dithiol-based-H2S prodrugs. In 2013, Xian and coworkers88 identified geminal-dithiol (gem-dithiol) as a structure, which could release H2S in aqueous solution. Then a photo-cleavable structure (a 2-nitrobenzyl group) was introduced to protect the gem-thiols group. When the molecules were exposed to UV-light, gem-dithiols were regenerated. Subsequent hydrolysis leads to H2S release. Based on this strategy, several gem-dithiol-based H2S prodrugs were prepared. Methylene Blue assay indicated that 200 μmol/L prodrugs could generate a peak concentration of 36 μmol/L H2S under UV irradiation (365 nm). However, there are two obvious drawbacks of these prodrugs. First, H2S release rate depends on the hydrolysis of gem-dithol, which is nearly fixed. Second, the reactive byproducts 2-nitrosobenzaldehyde can react with H2S, which results in diminishing H2S generation. Later, Nakagawa׳s group89 investigated another type of photo-induced H2S prodrugs: ketoprofenate-caged H2S prodrugs (Scheme 7). Upon UV irradiation (300–350 nm) for 10 min, 500 μmol/L of the prodrug would generate 30 μmol/L of H2S in fetal bovine serum together with 2-propenylbenzophenone and CO2. These two photo-induced H2S prodrugs successfully demonstrated the photo-triggering concept, but the cytotoxicity induced by UV-light could limit their applications.

Scheme 7.

H2S release from photo-induced H2S prodrugs.

2.3.3. Thiolamino acid

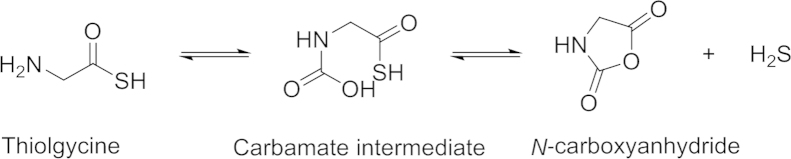

Thiolamino acids as the third class of controllable H2S-releasing prodrugs were first reported by Giannis and coworkers90 in 2012. Thioglycine and thiovaline were shown to release H2S in the presence of bicarbonate under physiological conditions. The mechanism is shown in Scheme 8.

Scheme 8.

Proposed mechanism of H2S release from thiolamino acids.

The thioamino acids interacted with bicarbonate to form carbamate intermediates, which undergoes a cyclization reaction leading to N-carboxyanhydride and H2S release (Scheme 8). 1H NMR spectroscopy studies were carried out to measure the decomposition of thioglycine in the presence of NaHCO3. In a 40 mmol/L bicarbonate solution at 40 °C, 35% N-carboxyanhydride were formed in 72 h. Since there is a high bicarbonate concentration (27 mmol/L) in blood at physiological pH, thiolamino acids can be an H2S prodrug candidate. Giannis and coworkers91 compared the H2S-releasing capacities of thiolamino acids with that of GYY4137. About 50 μmol/L H2S from 100 μmol/L of thioglycine could be detected by a fluorescent probe dibromobimane, while GYY4137 liberated less H2S at the same condition. Giannis and coworkers also tested the pharmacological benefits of such H2S prodrugs. Results showed that thioglycine and thiovaline could enhance intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) concentration and promote vasorelaxation. One possible limit of the bicarbonate activated H2S prodrugs stems from the reactivity of thiolamino acids, which could quickly undergo amidation reaction under aerobic conditions (Scheme 9)91.

Scheme 9.

Amidation of thiolacid.

3. Conclusions

The review gives a brief summary of the current state of H2S prodrugs. These prodrugs not only play an important role as research tools but also are promising candidates for the development of therapeutic agents. All prodrugs have their advantages, and also limitations. The most challenging in this field is still the development of prodrugs with precise control of the release kinetics so that they mimic endogenous H2S generation. The effects of prodrugs themselves and the byproducts need to be taken into consideration in all the biological experiments. Thus, new hydrogen sulfide prodrugs with improved control of release kinetics are needed in this field.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandiver MS, Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide: a gasotransmitter of clinical relevance. J Mol Med. 2012;90:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0873-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowicka E, Beltowski J. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)—the third gas of interest for pharmacologists. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308:518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Moore PK. Putative biological roles of hydrogen sulfide in health and disease: a breath of not so fresh air? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Zhao B, Wang C, Wang H, Liu Z, Li W. Regulatory effects of hydrogen sulfide on IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 levels in the plasma and pulmonary tissue of rats with acute lung injury. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233:1081–1087. doi: 10.3181/0712-RM-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andruski B, McCafferty DM, Ignacy T, Millen B, McDougall JJ. Leukocyte trafficking and pain behavioral responses to a hydrogen sulfide donor in acute monoarthritis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R814–R820. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90524.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrotriya S, Kundu JK, Na HK, Surh YJ. Diallyl trisulfide inhibits phorbol ester-induced tumor promotion, activation of AP-1, and expression of COX-2 in mouse skin by blocking JNK and Akt signaling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1932–1940. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Liu H, Sun D, Qiao W, Qi Y, Sun H. Effects of H2S on myogenic responses in rat cerebral arterioles. Circ J. 2012;76:1012–1019. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckler KJ. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulphide on calcium signalling, background (TASK) K channel activity and mitochondrial function in chemoreceptor cells. Pflug Arch. 2012;463:743–754. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisjak M, Srivastava N, Teklic T, Civale L, Lewandowski K, Wilson I. A novel hydrogen sulfide donor causes stomatal opening and reduces nitric oxide accumulation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:931–935. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, Biggs TD, Xian M. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) releasing agents: chemistry and biological applications. Chem Commun. 2014;50:11788–11805. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee S. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008;117:2351–2360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osborne NN, Ji D, Majid AS, Del Soldata P, Sparatore A. Glutamate oxidative injury to RGC-5 cells in culture is necrostatin sensitive and blunted by a hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-releasing derivative of aspirin (ACS14) Neurochem Int. 2012;60:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H2S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:499–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giggenbach W. Optical spectra of highly alkaline sulfide solutions and the second dissociation constant of hydrogen sulfide. Inorg Chem. 1971;10:1333–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ungerer PW, Aurelie, Demoulin G, Bourasseau E, Mougin P. Application of Gibbs ensemble and NPT Monte Carlo simulation to the development of improved processes for H2S-rich gases. Mol Simul. 2004;30:631–648. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes MN, Centelles MN, Moore KP. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: the chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLeon ER, Stoy GF, Olson KR. Passive loss of hydrogen sulfide in biological experiments. Anal Biochem. 2012;421:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng B, Xian M. Hydrogen sulfide detection using nucleophilic substitution-cyclization-based fluorescent probes. Methods Enzymol. 2015;554:47–62. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng H, Cheng Y, Dai C, King AL, Predmore BL, Lefer DJ. A fluorescent probe for fast and quantitative detection of hydrogen sulfide in blood. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang K, Peng H, Wang B. Recent advances in thiol and sulfide reactive probes. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1007–1022. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin VS, Chang CJ. Fluorescent probes for sensing and imaging biological hydrogen sulfide. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian Y, Karpus J, Kabil O, Zhang S. Y, Zhu H. L, Banerjee R. Selective fluorescent probes for live-cell monitoring of sulphide. Nat Commun. 2011;2:495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lippert AR, New EJ, Chang CJ. Reaction-based fluorescent probes for selective imaging of hydrogen sulfide in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10078–10080. doi: 10.1021/ja203661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles EW, Kraus JP. Cystathionine beta-synthase: structure, function, regulation, and location of homocystinuria-causing mutations. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29871–29874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin LR, Francom D, Dieken FP, Taylor JD, Warenycia MW, Reiffenstein RJ. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography: postmortem studies and two case reports. J Anal Toxicol. 1989;13:105–109. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warenycia MW, Goodwin LR, Benishin CG, Reiffenstein RJ, Francom DM, Taylor JD. Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Demonstration of selective uptake of sulfide by the brainstem by measurement of brain sulfide levels. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:973–981. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage J.C, Gould D.H. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue and rumen fluid by ion-interaction reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1990;526:540–545. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stipanuk M.H, Beck P.W. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem J. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, Padovani D, Leslie R.A., Chiku T, Banerjee R. Relative contributions of cystathionine β-synthase and γ-cystathionase to H2S biogenesis via alternative trans-sulfuration reactions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22457–22466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiku T, Padovani D, Zhu W, Singh S, Vitvitsky V, Banerjee R. H2S biogenesis by human cystathionine γ-lyase leads to the novel sulfur metabolites lanthionine and homolanthionine and is responsive to the grade of hyperhomocysteinemia. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11601–11612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808026200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikami Y, Shibuya N, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Yamada M, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects the retina from light-induced degeneration by the modulation of Ca2+ influx. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39379–39386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milner JA. Mechanisms by which garlic and allyl sulfur compounds suppress carcinogen bioactivation. Garlic and carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;492:69–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1283-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman K. Historical perspective on garlic and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2001;131:977s–979s. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.977S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powolny AA, Singh SV. Multitargeted prevention and therapy of cancer by diallyl trisulfide and related Allium vegetable-derived organosulfur compounds. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuah SC, Moore PK, Zhu YZ. S-allylcysteine mediates cardioprotection in an acute myocardial infarction rat model via a hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2693–H2701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00853.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amagase H. Clarifying the real bioactive constituents of garlic. J Nutr. 2006;136:716s–725s. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.716S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Truong D, Hindmarsh W, O׳Brien PJ. The molecular mechanisms of diallyl disulfide and diallyl sulfide induced hepatocyte cytotoxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang C, Kan J, Liu X, Ma F, Tran B. H, Zou Y. Cardioprotective effects of a novel hydrogen sulfide agent—controlled release formulation of S-propargyl-cysteine on heart failure rats and molecular mechanisms. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondo K, Bhushan S, King AL, Prabhu SD, Hamid T, Koenig S. H2S protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2013;127:1116–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis AJ, Giggenbach W. Hydrogen sulphide ionization and sulphur hydrolysis in high temperature solution. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1971;35:247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YH, Wu R, Geng B, Qi Y. F, Wang PP, Yao W. Z. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide reduces airway inflammation and remodeling in a rat model of asthma. Cytokine. 2009;45:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esechie A, Kiss L, Olah G, Horvath EM, Hawkins H, Szabo C. Protective effect of hydrogen sulfide in a murine model of acute lung injury induced by combined burn and smoke inhalation. Clin Sci. 2008;115:91–97. doi: 10.1042/CS20080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhi L, Ang A. D, Zhang H, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide induces the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines in human monocyte cell line U937 via the ERK-NF-κB pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1322–1332. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1006599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang H, Zhi L, Moochhala SM, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulates leukocyte trafficking in cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:894–905. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Hegde A, Ng SW, Adhikari S, Moochhala SM, Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide up-regulates substance P in polymicrobial sepsis-associated lung injury. J Immunol. 2007;179:4153–4160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine γ-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghasemi M, Dehpour AR, Moore KP, Mani AR. Role of endogenous hydrogen sulfide in neurogenic relaxation of rat corpus cavernosum. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tumir H, Bosnir J, Vedrina-Dragojevic I, Dragun Z, Tomic S, Puntaric D. Preliminary investigation of metal and metalloid contamination of homeopathic products marketed in Croatia. Homeopathy. 2010;99:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li YF, Xiao CS, Hui RT. Calcium sulfide (CaS), a donor of hydrogen sulfide (H2S): a new antihypertensive drug? Med Hypotheses. 2009;73:445–447. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozturk T, Ertas E, Mert O. Use of Lawesson׳s reagent in organic syntheses. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5210–5278. doi: 10.1021/cr040650b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Lee LC, del Soldato P, Moore PK. Anti-inflammatory and gastrointestinal effects of a novel diclofenac derivative. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicolau LA, Silva RO, Damasceno SR, Carvalho NS, Costa NR, Aragao KS. The hydrogen sulfide donor, Lawesson׳s reagent, prevents alendronate-induced gastric damage in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:708–714. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20133030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Medeiros JV, Bezerra VH, Gomes AS, Barbosa AL, Lima-Junior RC, Soares PM. Hydrogen sulfide prevents ethanol-induced gastric damage in mice: role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels and capsaicin-sensitive primary afferent neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:764–770. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu Z, Peng H, Du Q, Lin W, Liu Y. GYY4137, a hydrogen sulfidereleasing molecule, inhibits the inflammatory response by suppressing the activation of nuclear factor κB and mitogenactivated protein kinases in Coxsackie virus B3infected rat cardiomyocytes. Mole Med Rep. 2015;11:1837–1844. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee ZW, Zhou J, Chen CS, Zhao Y, Tan CH, Li L. The slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor, GYY4137, exhibits novel anti-cancer effects in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing anti-inflammatory drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rose P, Moore PK, Ming SH, Nam OC, Armstrong JS, Whiteman M. Hydrogen sulfide protects colon cancer cells from chemopreventative agent β-phenylethyl isothiocyanate induced apoptosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3990–3997. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai W.J, Wang M.J, Ju L.H, Wang C, Zhu Y.C. Hydrogen sulfide induces human colon cancer cell proliferation: role of Akt, ERK and p21. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:565–572. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park CM, Zhao Y, Zhu Z, Pacheco A, Peng B, devarie-Baez NO. Synthesis and evaluation of phosphorodithioate-based hydrogen sulfide donors. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:2430–2434. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70145j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martelli A, Testai L, Citi V, Marino A, Pugliesi I, Barresi E. Arylthioamides as H2S donors: l-cysteine-activated releasing properties and vascular effects in vitro and in vivo. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:904–908. doi: 10.1021/ml400239a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao Y, Biggs TD, Xian M. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) releasing agents: chemistry and biological applications. Chem Commun. 2014;50:11788–11805. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Caliendo G, Cirino G, Santagada V, Wallace JL. Synthesis and biological effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S): development of H2S-releasing drugs as pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6275–6286. doi: 10.1021/jm901638j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schnitzer TJ, Burmester GR, Mysler E, Hochberg MC, Doherty M, Ehrsam E. Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the therapeutic arthritis research and gastrointestinal event trial (TARGET), reduction in ulcer complications: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:665–674. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16893-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh G, Fort JG, Goldstein JL, Levy RA, Hanrahan PS, Bello AE. Celecoxib versus naproxen and diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients: SUCCESS-I study. Am J Med. 2006;119:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kurahara K, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Honda K, Yao T, Fujishima M. Clinical and endoscopic features of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic ulcerations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sparatore A, Santus G, Giustarini D, Rossi R, Del Soldato P. Therapeutic potential of new hydrogen sulfide-releasing hybrids. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4:109–121. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chan MV, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics and gastrointestinal diseases: translating physiology to treatments. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G467–G473. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00169.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wallace J.L, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Cirino G, Fiorucci S. Gastrointestinal safety and anti-inflammatory effects of a hydrogen sulfide-releasing diclofenac derivative in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:261–271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fiorucci S, Orlandi S, Mencarelli A, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Distrutti E, Santucci L, Cirino G, Wallace J.L. Enhanced activity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of mesalamine (ATB-429) in a mouse model of colitis. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:996–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chattopadhyay M, Kodela R, Nath N, Dastagirzada YM, velazquez-Martinez CA, Boring D. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing NSAIDs inhibit the growth of human cancer cells: a general property and evidence of a tissue type-independent effect. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chattopadhyay M, Kodela R, Olson KR, Kashfi K. NOSH-aspirin (NBS-1120), a novel nitric oxide- and hydrogen sulfide-releasing hybrid is a potent inhibitor of colon cancer cell growth in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szabo C, Papapetropoulos A. Hydrogen sulphide and angiogenesis: mechanisms and applications. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:853–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suzuki K, Olah G, Modis K, Coletta C, Kulp G, Gero D. Hydrogen sulfide replacement therapy protects the vascular endothelium in hyperglycemia by preserving mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13829–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun WH, Liu F, Chen Y, Zhu YC. Hydrogen sulfide decreases the levels of ROS by inhibiting mitochondrial complex IV and increasing SOD activities in cardiomyocytes under ischemia/reperfusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Szczesny B, Modis K, Yanagi K, Coletta C, Le Trionnaire S, Perry A. AP39, a novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, stimulates cellular bioenergetics, exerts cytoprotective effects and protects against the loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells in vitro. Nitric Oxide. 2014;41:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Le Trionnaire S, Perry A, Szczesny B, Szabo C, Winyard PG, Whatmore JL. The synthesis and functional evaluation of a mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, (10-oxo-10-(4-(3-thioxo-3H-1,2-dithiol-5-yl)phenoxy)decyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (AP39) Med Chem Commun. 2014;5:728–736. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao Y, Wang H, Xian M. Cysteine-activated hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15–17. doi: 10.1021/ja1085723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhao Y, Bhushan S, Yang C, Otsuka H, Stein JD, Pacheco A. Controllable hydrogen sulfide donors and their activity against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1283–1290. doi: 10.1021/cb400090d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roger T, Raynaud F, Bouillaud F, Ransy C, Simonet S, Crespo C. New biologically active hydrogen sulfide donors. Chembiochem. 2013;14:2268–2271. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Devarie-Baez NO, Bagdon P.E., Peng B, Zhao Y, Park C.M., Xian M. Light-induced hydrogen sulfide release from “caged” gem-dithiols. Org Lett. 2013;15:2786–2789. doi: 10.1021/ol401118k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fukushima N, Ieda N, Sasakura K, Nagano T, Hanaoka K, Suzuki T. Synthesis of a photocontrollable hydrogen sulfide donor using ketoprofenate photocages. Chem Commun. 2014;50:587–589. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47421f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou Z, von Wantoch Rekowski M, Coletta C, Szabo C, Bucci M, Cirino G. Thioglycine and l-thiovaline: biologically active H2S-donors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:2675–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pan J, Devarie-Baez NO, Xian M. Facile amide formation viaS-nitrosothioacids. Org Lett. 2011;13:1092–1094. doi: 10.1021/ol1031393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]