Abstract

Background:

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) is one of the most common congenital anomalies and the etiology of orofacial clefts is multifactorial. Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFA) is expressed at the medial edge epithelium of fusing palatal shelves during craniofacial development. In this study, the association of two important TGFA gene polymorphisms, BamHI (rs11466297) and RsaI (rs3732248), with CL/P was evaluated in an Iranian population.

Methods:

The frequencies of BamHI and RsaI variations were determined in 105 unrelated Iranian subjects with nonsyndromic CL/P and 218 control subjects using PCR and RFLP methods, and the results were compared with healthy controls. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The BamHI AC genotype was significantly higher (p=0.016) in the patients (12.4%) than the control group (5.0%). The BamHI C allele was significantly higher (p=0.001; OR=3.4, 95% CI: 1.6–7.4) in the cases (8.0%) compared with the control group (2.5%).

Conclusion:

Our study showed that there was an association between the TGFA BamHI variation and nonsyndromic CL/P in Iranian population.

Keywords: Association Study, Cleft lip/palate, Polymorphism, Transforming Growth Factor Alpha

Introduction

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) is one of the most common birth defects1. The worldwide prevalence of CL and CL/P is 3.28 and 6.64 per 10.000 cases, respectively2–4. Genetic factors are thought to contribute to the development of this disorder, because the risk of recurrence of CL/P within a family is approximately 28–40-fold greater for the general population5–6. Nonsyndromic cleft in humans is most likely due to combination of genetic and environmental factors 7–8. Population based candidate gene studies as well as linkage disequilibrium has been used to identify the etiology of CL/P so as to predict its occurrence and to prevent it from occurring in the future. Identification of the genes involved in the development of the human craniofacial region can serve as a first step towards developing a better understanding of the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of developmental anomalies of this region9,10.

The association between CL/P and specific alleles in the transforming growth factor alpha (TGFA) gene suggests that TGFA could be a candidate gene for CL/P11–15.

In 1989, Ardinger et al published the first association study of CL/P with five candidate genes which were involved in palate formation. Analysis of 80 unrelated patients from Iowa showed that there were significant associations of CL/P with TaqI and BamHI RFLPs at the TGFA locus 34. Holder et al in a British population24, Tanabe et al in a Japanese population 30 and Stoll et al in the French population 25 indicated that the TGFA gene variant contributes to the occurrence of nonsyndromic CL/P. However, this is contrary to a study done by Lidral et al in the Philippines36, which may be due to genetic differences in different populations.

TGFA is, both structurally and functionally, similar to Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), and induces a mitogenic response by binding to and stimulating the tyrosine kinase activity of EGF receptor 16,17. During craniofacial development, TGFA is expressed at the medial edge epithelium of fusing palatal shelves 18,19. In palatal cultures, TGFA promotes synthesis of extracellular matrix and migration of mesenchymal cells to ensure the strength of the fused palate during seam disruption 20–24.

The TGFA gene is located on chromosome 2p1311, contains six exons and spans 80 kb of genomic DNA. Three common polymorphisms of the TNFA gene (RsaI, and TaqI in intron 5 and BamHI in exon 6) have been investigated with susceptibility to the CL/P25–27. The results of the association studies of TGFA gene polymorphisms and the risk of nonsyndromic CL/P have been contradictory and conflicting28–31. The aim of the present study was to investigate the association of the two common polymorphisms of the TGFA gene, BamHI and RsaI, in the development of nonsyndromic CL/P in an Iranian population for the first time.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

To determine the possible role of BamHI and RsaI polymorphisms in the TGFA gene in developing oral clefts in an Iranian population, a case-control study was performed. A sample of 105 newborns with nonsyndromic CL/P and 218 control subjects were included. A clinical examination to look for dysmorphic features (such as lip pits) was undertaken. The exclusion criteria of this study were evidence of other facial or skeletal malformations (such as lip pits, congenital heart lesion, etc), metabolic or neurologic disorders or anomalies of other organ systems. Samples were recruited from Mofid Hospital, a referral pediatrics center in Tehran, Iran in 2013–15. A control group consisted of 218 Iranian newborns, without cleft, who were born in or around Tehran between the years 2013 and 2015 were selected and their blood samples were stored. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Dental Research Center of the University of Shahid Beheshti. Informed consent was obtained from all parents.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Five ml of peripheral blood samples were collected in tubes containing 200 μl of 0.5 M EDTA and genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the salting out method32. Genotyping of the BamHI (rs11466297) and RsaI (rs3732248) polymorphisms in the TGFA gene was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) methods, according to the previous study. The primer sequences are shown in table 1. Briefly, a total volume of 25 μl containing 30 ng of genomic DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, 1 μl dNTPs mix (Fermentas, Life Science), 2.5 μl 10×buffer and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas Life Science, Lithuania) with 1.5 mM MgCl2 was prepared in the 0.5 ml Eppendorf microtube for amplification of the target sequences. Amplification conditions started with an initial denaturation step of 4 min at 95°C, followed by 33 cycles of 45 s denaturation (94°C), 30 s annealing (60°C) and 40 s extension (72°C), ended by a final extension for 5 min (72°C) and finally cooling to 4°C. The PCR products of the rs11466297 and rs3732248 polymorphisms were digested with the IU BamHI and RsaI restriction enzymes at 37°C overnight, respectively (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA). All PCR products were subjected to 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with silver nitrate. The pattern of restriction fragments for both BamHI and RsaI are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and their PCR product sizes, restriction enzymes, and RFLP fragments for the TGFA BamHI and RsaI polymorphisms

| SNPs | Global MAF* | Primer Sequence (5′→ 3) | Product Size (bp) | RFLP Fragments (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BamHI (rs11466297 A/C) | C=0.0238 | F: GCCTGGCTTATTTGGGGATT | 174 | A allele=120+54 | 33 |

| R: AAGGGCAAGGAAACACAGG | C allele=174 | ||||

| RsaI (rs3732248 C/T) | A=0.2075 | F: TGCCTTCCTTCTGCTATCACT | 166 | C allele=91+75 | 33 |

| R: CAGAGCCAATGTCACCAAGT | T allele=166 |

Global Minor Allele Frequency

Statistical analysis

Chi square (χ2) and Fisher’s exact test with Open Epi Version 2.2 (free statistical software) were performed to compare genotype and allele frequencies in the study groups. The p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical significance was corrected for multiple testing comparisons.

Results

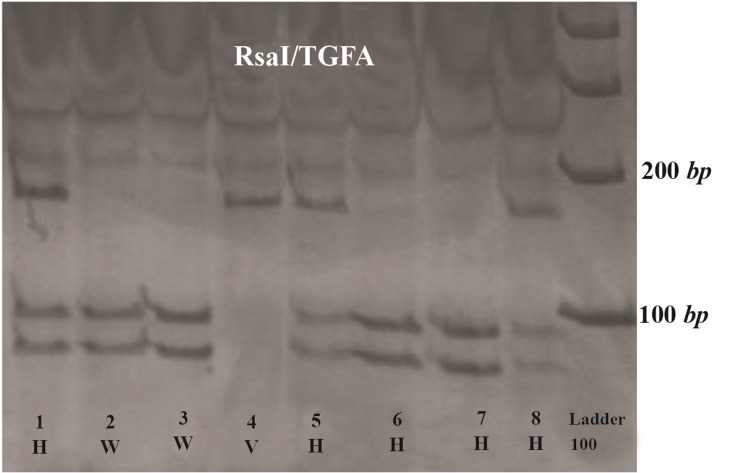

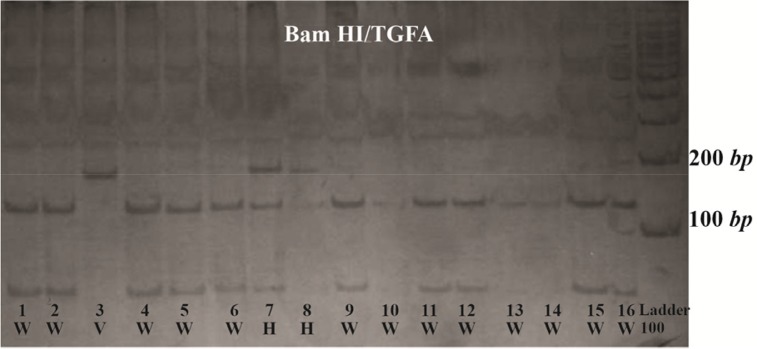

The samples consisted of 105 patients with cleft lip with or without cleft palate and 218 healthy controls. The CL/P samples consisted of 65 males (62.0%) and 40 females (38.0%). A positive family history of cleft was observed in 38 CL/P cases (36.19%). There were 34 (32.3%) patients with unilateral CL/P, 27 (25.7%) with bilateral CL/P, 15(14.2 %) cleft lip only and 29 (27.6%) with cleft palate only. The distributions of genotypes using chi-square showed that in both case and control groups, for the TGFA BamHI polymorphism, they were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p>0.05). For the TGFA RsaI polymorphism, the distributions of genotypes in the case group were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p=0.625). The genotype distributions and allele frequencies of the TGFA BamHI and RsaI polymorphisms are shown in table 2. The results of the genotyping for the BamHI and Rsa1 RFLP are shown in figures 1 and 2. Our results showed that there was a significant difference in the genotype distribution and allele frequency of the BamHI polymorphism between the case and control groups. The BamHI AC genotype was significantly higher (p=0.016; OR=2.1, 95% CI:1.2–6.3) in the patients (12.4%) than the control group (5.0%). The BamHI C allele was significantly higher (p=0.001; OR=3.4, 95% CI:1.6–7.4) in the cases (8.0%) compared with the control group (2.5%). In contrast, no significant difference in the genotype and allele frequencies of the RsaI polymorphism was found between the case and control groups.

Table 2.

The genotype and allele frequencies of the TGFA BamHI and RsaI polymorphisms in nonsyndromic CL±P patients and controls

| SNPs | Genotype/Allele | Cases (n=105) | Controls (n=218) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BamHI (rs11466297) | |||||

| AA | 90 (85.7%) | 207 (95.0%) | Reference Genotype | ||

| AC | 13 (12.4%) | 11 (5.0%) | 0.016 | 2.1 (1.2–6.3) | |

| CC | 2 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.187* | undefined’ | |

| A | 193 (92.0%) | 425 (97.5%) | Reference Allele | ||

| C | 17 (8.0%) | 11 (2.5%) | 0.001 | 3.4 (1.6–7.4) | |

| RsaI (rs3732248) | |||||

| CC | 68 (64.8%) | 127 (58.3%) | Reference Genotype | ||

| CT | 32 (30.5%) | 69 (31.6%) | 0.582 | 0.87 (0.7–2.1) | |

| TT | 5 (4.7%) | 22 (10.1%) | 0.090 | 0.42 (0.6–3.3) | |

| C | 168 (80.0%) | 323 (74.0%) | Reference Allele | ||

| T | 42 (20.0%) | 113 (26.0%) | 0.099 | 0.71 (0.8–6.1) | |

Fisher’s exact test p-value

Figure 1.

TGFA BamHI RFLP. Three genotypes from CL/P cases demonstrating the wild type (W), Heterovariant (H) and HomoVariant (V). After digestion with the restriction enzyme BamHI, the amplified product was completely digested with one restriction site and two specific bands of 120 bp and 54 bp were indicated in wild type genotype.

Figure 2.

TGFA RsaI RFLP. Three genotypes from CL/P cases demonstrating the wild type (W), Heterovariant (H) and Homovariant (V). After digestion with the restriction enzyme RsaI, the amplified product was completely digested with one restriction site and two specific bands of 91 bp and 75 bp were indicated in wild type genotype.

Discussion

TGFA was chosen as a candidate gene in the preliminary association studies of CL/P, because it is expressed in palatal tissue in culture16,30. It subsequently revealed that TGFA was present at high levels in epithelial tissue of the medial edge of the palatal shelves at the time of shelf fusion17. The role of TGFA in lip and palate development was then evaluated in different populations.

This study was performed to examine whether the TGFA BamHI (rs11466297 A/C) and RsaI (rs3732248 C/T) variations are associated with the increased risk of CL/P in an Iranian population including 105 CL/P patients and 218 controls. Our results showed that TGFA BamHI polymorphism was associated with the CL/P in Iranian population. The frequency of the BamHI AC genotype in the patients (12.4%) was approximately twice more than that of control group (5.0%). The BamHI C allele was significantly higher in the CL/P patients (8.0%) compared with the control group (2.5%). This result suggests that the C allele may be a risk factor for CL/P in Iranian population. In contrast, no significant difference in the genotype and allele frequencies of the RsaI polymorphism was found between the case and control groups. The minor allele frequencies in the control groups, for the BamHI and RsaI polymorphisms were C=0.025 and A=0.260, respectively, which are very close to the global minor allele frequencies (0.024 and 0.208, respectively).

Ardinger et al 1989 investigated the possible association of five candidate genes including TGFA, Nuclear Receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (NR3C1), Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and estrogen receptor (ESR) in an American population with nonsyndromic CL/P. They found a significant association between the TGFA BamHI and TaqI polymorphisms and the occurrence of cleft. Their results suggest that TGFA gene or adjacent DNA sequences may contribute to the development of a portion of cases with CL/P33. Holder et al 1992 studied the three variations of TGFA (BamHI, TaqI and RsaI) in a British population with CL/P, and they found a significant association between the TaqI polymorphism and occurrence of cleft24. Stoll et al (1992) detected a significant association with BamHI and not with TaqI in a French population of Alsatian ancestry with CL/P. They concluded that TGFA may be a modifier gene, not a major gene that may play a role in the development of bilateral cleft in some individuals25. Chenevix-Trench et al 1992 studied the two polymorphisms of TGFA in unrelated Australians with CL/P and a significant association between the TGFA TaqI and BamHI polymorphism and CL/P was confirmed34. Lidral et al 1997 evaluated the association of four candidate genes TGFA, TGFB2, TGFB3, homeobox 7 (MSX1) variations in a population from Philippines; however, no evidence for association of TGFA with nonsyndromic CL/P was found in non-Caucasian population35. Tanabe et al 2000 assessed the association of polymorphisms of candidate genes TGFA, TGFB and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor beta3 (GABRB3) with nonsyndromic CL/P in Japanese patients, and they found that the TGFA and TGFB2 polymorphisms were associated with CL/P30.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study showed that there was an association between the TGFA BamHI variation and nonsyndromic CL/P in Iranian population. Since common environmental exposures especially maternal smoking could play a role in the CL/P etiology, it is suggested that further works be done to explore the role of possible gene-environment interaction in the etiology of CL/P.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Roozrokh (Dean of Mofid Hospital) and Mofid hospital staff for their kind helps in recruiting study subjects. Moreover, this study was carried out as a part of a master of sciences thesis in Shahid Behehsti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran and Genetic Research Centre, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Mijiti A, Ling W, Guli, Moming A. Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the IRF6 gene with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the Xinjiang Uyghur population. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015; 53 (3): 268– 274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Niranjane PP, Kamble RH, Diagavane SP, Shrivastav SS, Batra P, Vasudevan SD, et al. Current status of presurgical infant orthopaedic treatment for cleft lip and palate patients: A critical review. Indian J Plast Surg 2014; 47 (3): 293– 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ranganathan K, Vercler CJ, Warschausky SA, MacEachern MP, Buchman SR, Waljee JF. Comparative effectiveness studies examining patient-reported outcomes among children with cleft lip and/or palate: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 135 (1): 198– 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crockett DJ, Goudy SL. Cleft lip and palate. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2014; 22 (4): 573– 586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aldhorae KA, Böhmer AC, Ludwig KU, Esmail AH, Al-Hebshi NN, Lippke B, et al. Nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in arab populations: genetic analysis of 15 risk loci in a novel case-control sample recruited in Yemen. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2014; 100 (4): 307– 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rajabian MH, Sherkat M. An epidemiologic study of oral clefts in Iran: analysis of 1,669 cases. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2000; 37 (2): 191– 196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalaskar R, Kalaskar A, Naqvi FS, Tawani GS, Walke DR. Prevalence and evaluation of environmental risk factors associated with cleft lip and palate in a central Indian population. Pediatr Dent 2013; 35 (3): 279– 283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ibarra-Lopez JJ, Duarte P, Antonio-Vejar V, Calderon-Aranda ES, Huerta-Beristain G, Flores-Alfaro E, et al. Maternal C677T MTHFR polymorphism and environmental factors are associated with cleft lip and palate in a Mexican population. J Investig Med 2013; 61 (6): 1030– 1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grosen D, Chevrier C, Skytthe A, Bille C, Mølsted K, Sivertsen A, et al. A cohort study of recurrence patterns among more than 54,000 relatives of oral cleft cases in Denmark: support for the multifactorial threshold model of inheritance. J Med Genet 2010; 47 (3): 162– 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beaty TH, Taub MA, Scott AF, Murray JC, Marazita ML, Schwender H, et al. Confirming genes influencing risk to cleft lip with/without cleft palate in a case-parent trio study. Hum Genet 2013; 132 (7): 771– 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brissenden JE, Derynck R, Francke U. Mapping of transforming growth factor alpha gene on human chromosome 2 close to the breakpoint of the Burkitt’s lymphoma t(2;8) variant translocation. Cancer Res 1985; 45 (11 Pt 2): 5593– 5597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tricoli JV, Nakai H, Byers MG, Rall LB, Bell GI, Shows TB. The gene for human transforming growth factor alpha is on the short arm of chromosome 2. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1986; 42 (1–2): 94– 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nemo R, Murcia N, Dell KM. Transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-alpha) and other targets of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme (TACE) in murine polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Res 2005; 57 (5 Pt 1): 732– 737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mydlo JH, Michaeli J, Cordon-Cardo C, Goldenberg AS, Heston WD, Fair WR. Expression of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA in neoplastic and nonneoplastic human kidney tissue. Cancer Res 1989; 49 (12): 3407– 3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beaty TH, Hetmanski JB, Zeiger JS, Fan YT, Liang KY, VanderKolk CA, et al. Testing candidate genes for non-syndromic oral clefts using a case-parent trio design. Genet Epidemiol 2002; 22 (1): 1– 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dixon MJ, Ferguson MW. The effects of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factors alpha and beta and platelet-derived growth factor on murine palatal shelves in organ culture. Arch Oral Biol 1992; 37 (5): 395– 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, Dixon MJ, Shaw WC. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 2009; 374 (9703): 1773– 1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitchell LE. Transforming growth factor alpha locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate: a reappraisal. Genet Epidemiol 1997; 14 (3): 231– 240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vieira AR, Orioli IM. Candidate genes for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. ASDC J Dent Child 2001; 68 (4): 272– 279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shiang R, Lidral AC, Ardinger HH, Buetow KH, Romitti PA, Munger RG, et al. Association of transforming growth-factor alpha gene polymorphisms with nonsyndromic cleft palate only (CPO). Am J Hum Genet 1993; 53 (4): 836– 843. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Machida J, Yoshiura Ki, Funkhauser CD, Natsume N, Kawai T, Murray JC. Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGFA): genomic structure, boundary sequences, and mutation analysis in nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate and cleft palate only. Genomics 1999; 61 (3): 237– 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qian JF, Feingold J, Stoll C, May E. Transforming growth factor-alpha: characterization of the BamHI, RsaI, and TaqI polymorphic regions. Am J Hum Genet 1993; 53 (1): 168– 175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vanderas AP. Incidence of cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip and palate among races: a review. Cleft Palate J 1987; 24 (3): 216– 225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holder SE, Vintiner GM, Farren B, Malcolm S, Winter RM. Confirmation of an association between RFLPs at the transforming growth factor-alpha locus and non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. J Med Genet 1992; 29 (6): 390– 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stoll C, Qian JF, Feingold J, Sauvage P, May E. Genetic variation in transforming growth factor alpha: possible association of BamHI polymorphism with bilateral sporadic cleft lip and palate. Hum Genet 1993; 92 (1): 81– 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jugessur A, Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Murray JC, Taylor JA, Saugstad OD, et al. Cleft palate, transforming growth factor alpha gene variants, and maternal exposures: assessing gene-environment interactions in case-parent triads. Genet Epidemiol 2003; 25 (4): 367– 374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Basart AM, Qian JF, May E, Murray JC. A PCR method for detecting polymorphism in the TGFA gene. Hum Mol Genet 1994; 3 (4): 678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jara L, Blanco R, Chiffelle I, Palomino H, Carreño H. Evidence for an association between RFLPs at the transforming growth factor alpha (locus) and nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate in a South American population. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 56 (1): 339– 341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jara L, Blanco R, Chiffelle I, Palomino H, Curtis D. [Cleft lip and palate in the Chilean population: association with BamH1 polymorphism of the transforming growth factor alpha (TGFA) gene]. Rev Med Chil 1993; 121 (4): 390– 395. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanabe A, Taketani S, Endo-Ichikawa Y, Tokunaga R, Ogawa Y, Hiramoto M. Analysis of the candidate genes responsible for non-syndromic cleft lip and palate in Japanese people. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000; 99 (2): 105– 111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vieira AR. Association between the transforming growth factor alpha gene and nonsyndromic oral clefts: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 163 (9): 790– 810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jawdat NG, Adnan FN, Akeel HA. Simple salting – out method for genomic DNA extraction from whole blood. Tikrit J Pure Sci 2011; 16 (2): 9– 11 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ardinger HH, Buetow KH, Bell GI, Bardach J, Van-Demark DR, Murray JC. Association of genetic variation of the transforming growth factor-alpha gene with cleft lip and palate. Am J Hum Genet 1989; 45 (3): 348– 353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chenevix-Trench G, Jones K, Green AC, Duffy DL, Martin NG. Cleft lip with or without cleft palate: associations with transforming growth factor alpha and retinoic acid receptor loci. Am J Hum Genet 1992; 51 (6): 1377– 1385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lidral AC, Murray JC, Buetow KH, Basart AM, Schearer H, Shiang R, et al. Studies of the candidate genes TGFB2, MSX1, TGFA, and TGFB3 in the etiology of cleft lip and palate in the Philippines. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1997; 34 (1): 1– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]