Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and its main feature, chronic intermittent hypoxia (IH) during sleep, is closely associated with insulin resistance (IR) and diabetes. Rimonabant can regulate glucose metabolism and improve IR. The present study aimed to assess the effect of IH and rimonabant on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, and to explore the possible mechanisms.

Material/Methods

Thirty-two rats were randomly assigned into 4 groups: Control group, subjected to intermittent air only; IH group, subjected to IH only; IH+NS group, subjected to IH and treated with normal saline; and IH+Rim group, subjected to IH and treated with 10 mg/kg/day of rimonabant. All rats were killed after 28 days of exposure. Then, the blood and skeletal muscle were collected. We measured fasting blood glucose levels, fasting blood insulin levels, and the expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) in both mRNA and protein levels in skeletal muscle.

Results

IH can slow weight gain, increase serum insulin level, and reduce insulin sensitivity in rats. The expressions of GLUT4 mRNA, total GLUT4, and plasma membrane protein of GLUT4 (PM GLUT4) in skeletal muscle were decreased. Rimonabant treatment was demonstrated to improve weight gain and insulin sensitivity of the rats induced by IH. Rimonabant significantly upregulated the expression of GLUT4 mRNA, PM GLUT4, and total GLUT4 in skeletal muscle.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that IH can cause IR and reduced expression of GLUT4 in both mRNA and protein levels in skeletal muscle of rats. Rimonabant treatment can improve IH – induced IR, and the upregulation of GLUT4 expression may be involved in this process.

MeSH Keywords: Anoxia; Glucose Transporter Type 4; Insulin Resistance; Receptor, Cannabinoid, CB1; Sleep Apnea, Obstructive

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), characterized by complete or partial upper airway collapse occurring repeatedly during sleep, is a condition that affects 10% of men and 3% of women in the general population [1].

OSA is closely associated with insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 diabetes and has been shown to be an independent risk factor for incident diabetes [2]. Population studies have shown that OSA was positively related to the degree of IR, and the more severe the OSA, the greater the IR [3]. Furthermore, several studies sustain the hypothesis that sleep apnea per se deteriorates insulin sensitivity, independent of obesity and other important confounding factors of IR [1]. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can reverse the IR of OSA [4]. Moreover, healthy volunteers in intermittent hypoxia (IH) condition simulating moderate OSA showed a trend of decreased insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness after 5 hours [5] and similar results were observed in an animal model. In a non-obese rodent model of OSA, chronic IH led to IR and impaired glucose tolerance [6].

Skeletal muscle accounts for 70–80% of the insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in healthy humans, exerting a key role in regulating whole-body glucose homeostasis, and IR in skeletal muscle has long been recognized as a characteristic feature of type 2 diabetes and plays a major role in the pathogenesis of the disease [7]. IR at the level of the skeletal muscle is associated with decrease in glucose uptake into skeletal muscle cells through glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) [8], which is the main glucose transporter isoform expressed in skeletal muscle. Under normal resting conditions, most of the GLUT4 molecules reside in membrane vesicles inside the muscle cell. In response to insulin or muscle contractions, GLUT4 translocates to the cell membrane, where it is inserted to increase glucose transport [9]. Several early studies indicated that the amount of plasma membrane protein of GLUT4(PM GLUT4) expressed is strongly correlated with maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle [10]. The impaired GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle may mediate IR and is widely accepted as an IR mechanism [11]. The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is crucial in the regulation of metabolism and energy homeostasis [12]. It consists of cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids, and the enzymes involved in their biosynthesis and degradation, and is present both in the brain and peripheral tissues, including skeletal muscle [13]. There are 2 G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors: CB1 and CB2. CB1 activation is associated with IR and dyslipidemia. Activation of CB1 results in increased food intake and IR by inhibiting glucose uptake into skeletal muscle [14]. CB1 blockade or genetic knockout of CB1 results in decreased food intake and body weight, increased insulin sensitivity, and improvements in glucose homeostasis through increased insulin-mediated glucose transport in skeletal muscles [15,16], and similar effects were reported in obese subjects treated with the CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant [17].

Although the association between OSA, IH, ECS, and IR has been clearly documented, the mechanisms remain largely unknown. Because the regulation of glucose uptake is mainly achieved through the recruitment of the GLUT4 glucose transporter from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane, analysis of GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle is helpful in understanding the changes of insulin sensitivity. However, the respective contributions of IH and ECS to GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle tissue are not clearly established. To further clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms of CB1 receptor antagonist for treating IR in patients with OSA, an IH model in rats was generated and the effects and mechanism of IH and rimonabant on glucose metabolism and expression of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle were investigated.

Material and Methods

Animals

A total of 32 eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, were used in this study. Rats were purchased from the Animal Center of Gansu Traditional Medical University. Each rat was fed standard rat chow and provided drinking water ad libitum. All of the rats were allowed to acclimatize to their surroundings for at least 1 week, and were randomly assigned into 4 different groups with 8 rats in each group: i) Control group: rats were exposed to intermittent oxygen conditions without rimonabant treatment; ii) IH group: rats were exposed to intermittent hypoxic conditions without rimonabant treatment; iii) IH+NS group: rats were exposed to intermittent hypoxic conditions and administered intragastrically daily with 3 ml normal saline; and iv) IH+Rim group: rats were exposed to intermittent hypoxic conditions and intragastrically administered with 10 mg/kg/day of rimonabant daily, which was prepared by adding 3 ml normal saline. The body weight of animals was recorded every day for all animals. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Lanzhou, China).

Hypoxic exposure

Rats in the IH group, IH+Rim group, and IH+NS group were placed into a specially designed chamber, which contained a gas control delivery system to regulate the flow of oxygen and nitrogen into the chamber. During each 2-min period of IH, the oxygen concentration in the chamber was set at between 7% and 21%. Nitrogen was introduced at a rate sufficient to achieve a FiO2 of 6–8% within 20 s and to maintain this level of FiO2 for 10 s; then, oxygen was introduced at a rate to achieve a FiO2 of 21% within 20 s and maintain this level until the next cycle. The rats were placed into this chamber every day from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. for 28 days. At all other times, the rats were kept in chambers with an oxygen concentration of 21%. The oxygen concentration in each chamber was measured continuously with an oxygen analyzer (CY-12C, Zhuhai City, China). The control group was handled in the same manner as the IH group, except the oxygen concentration in the control chambers was maintained at a constant 21% throughout the experiment.

Sample collection

On the 29th day, after body weight measurement, every rat was anesthetized intraperitoneally with 3% pentobarbital at a dose of 30 mg/kg body weight after fasting for 12 h overnight. After complete anesthesia, the abdominal cavity was rapidly opened along the median line of the abdomen. Blood was rapidly drawn from the abdominal vena cava into syringes and immediately sent for chemical examination. The soleus muscle of the left limb was collected immediately from each rat and was frozen and stored at −80°C until the analytical assay was performed.

Measurement of fasting blood glucose and serum insulin

The fasting blood glucose (FBG) and fasting insulin (FINS) of all rats were measured at a laboratory in the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Lanzhou, China) with routine standardized methodologies on day 29. Glucose was measured in plasma and insulin analysis was performed on serum. IR was assessed using the Homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR). Insulin sensitivity was assessed using Insulin sensitivity index (ISI). HOMA-IR=(FBG×FINS)/22.5 and ISI=1/(FBG×FINS). All of the measurements were performed at the same time in order to avoid procedural variations. All samples were measured in duplicate.

Immunohistochemical staining for GLUT4 protein expression

The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, followed by rehydration in decreasing ethanol concentrations at room temperature. After antigen retrieval with high-temperature heating in citrate buffer (10 mM citrate, pH 6.0), the slides were incubated with inhibitor buffer (3% H2O2) and washed with PBS (0.01mol/L), then reacted with goat anti-rat GLUT4 primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C. After another washing with PBS, the slides were incubated with rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody polymer-based EnVision-HRP-enzyme conjugate (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at room temperature. The slides were observed under an optical microscope and 10 non-overlapped high-magnification fields were selected after 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. Average optical density values of every field were measured using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

RNA isolation and real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from frozen skeletal muscle specimens using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GLUT4 mRNA expression in skeletal muscle tissues was measured by RT-qPCR using an ABI7900HT instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RT-qPCR was done using a SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. β-actin was used as an internal control. The sequences of the primer pairs that were specific for each gene are shown in Table 1. Relative mRNA levels were calculated based on the Ct values and normalized using β-actin expression, according to the equation:

Table 1.

Forward and reverse oligonucleotide primer sequences.

| Gene | Genbank ID | Forward primer (5′----3′) | Reverse primer (5′----3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | 81822 | TGTCACCAACTGGGACGATA | GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA |

| GLUT4 | 25139 | TTGGGTTTGGAGTCTATGCTG | GACAGAAGGGCAACAGAAGC |

Fluorescence was measured for each amplification cycle, and the data were analyzed for the relative quantification of expression. All experiments were done in triplicate.

Purification of plasma membrane proteins of skeletal muscle

Plasma membrane protein of the soleus muscle was extracted using a plasma membrane protein extraction kit (Catalog number K268-50, BioVision Inc., USA) and following the manufacturer’s protocols and description [11]. The BioVision kit was specifically designed to purify the plasma membrane proteins, which can be utilized in a variety of applications, such as Western blotting, 2-D gels, and enzyme analyses. Briefly, the muscle tissue (100 mg) was homogenized on ice in Homogenizing Buffer with 1 mM phenyl methanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) until completely lysed (30–50 times). The homogenate was centrifuged at 700×g for 10 min and then the supernatant was centrifuged at 14 000×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant (the cytosol fraction) was collected and resuspended in the Upper-Phase Solution with 1 mM PMSF, then we added the Lower Phase Solution, incubated it on ice for 5 min, and centrifuged it at 1000×g for 5 min at 4°C. The upper phase was carefully collected, then centrifuged at 14 000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet, which contained the plasma membrane protein, was determined with BCA protein assay and was stored at −80°C for subsequent Western blotting.

Western blotting analysis for GLUT4

As described previously [18], 100 mg of soleus muscle kept in −80°C from soleus muscle of different groups were homogenized in 10–20 volumes, with a buffer containing 1% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), 100 mmol/L Tris HCl (pH6.8), 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 0.1 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12 000×g for 50 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined with BCA protein assay. For each sample, proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 10% sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane (Bio-Rad Instruments, CA, USA) in a transfer buffer containing 25 mmol/L Tris, 192 mmol/L glycine, and 20% methanol. The NC membranes were blocked using PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% Tween-20 at 4°C for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were incubated with anti-GLUT4 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with the corresponding goat anti-rabbit-HRP secondary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at room temperature for 1 h. Photos were acquired using a gel imaging analysis system (VersaDoc4000; Bio-Rad). Quantification analysis of blots was performed with NIH Image J software. The same procedure can also be used to detect the expression of PM GLUT4. The relative amount of GLUT4 was represented by the GLUT4/β-actin gray-scale ratio.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 19 program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. For a comparison between groups, the t test or one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference (SLD) was used. The confidence interval was set at 95% and statistical difference was set at P<0.05.

Results

Effects of IH and rimonabant on body weight

Body weight of all rats was measured daily for a period of 28 days at 8 a.m. everyday (before hypoxia exposure). Compared with the control group, the body weight in rats decreased in the IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group. Early in the experiment, body weight increase was slower in rats in the IH+Rim group compared to the IH+NS group, but at the later stage of the experiment, the body weight of rats in IH+Rim group increased faster than that of IH+NS group. At day 29, the body weight of control rats was 369.1±16.4 g and that of IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group were 337.8±19.1 g, 339.0±25.9 g, and 356.0±26.0 g, respectively. Compared with the control group, the weights of the IH group and IH+NS group were significantly lower (P<0.05). Compared with the IH+NS group, the weight of the IH+Rim group rats were significantly higher (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in body weight between IH and IH+NS groups or between control group and IH+Rim group (P>0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weight gain of rats in control group, IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group.

Effects of IH and rimonabant on glucose metabolism

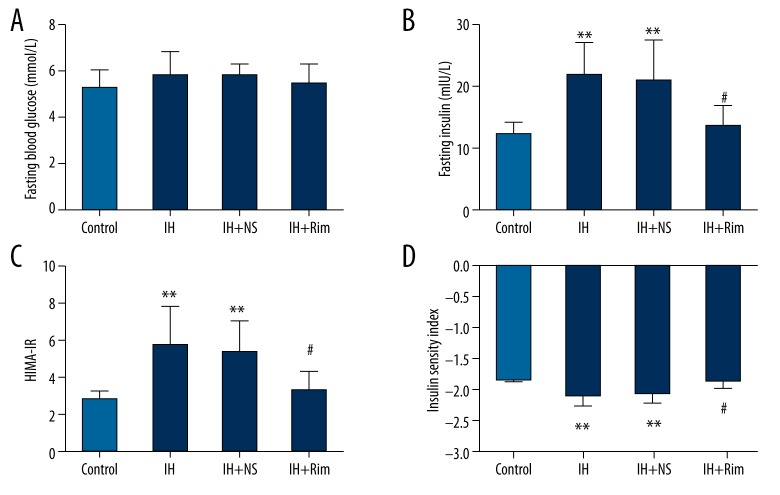

There was no significant difference in fasting blood glucose levels among groups (P>0.05). Compared with the control group, the fasting insulin level and HOMA-IR of the IH group and IH+NS group were significantly higher (P<0.01) and ISI was significantly lower (P<0.01). Compared with the IH+NS group, the fasting insulin level and HOMA-IR of the IH+Rim group were significantly lower (P<0.05) and ISI was significantly higher (P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in fasting insulin level, HOMA-IR, or ISI between the IH+Rim group and control group or between the control group and IH+Rim group (P>0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of IH and rimonabant on glucose metabolism in rats. (A) Blood glucose levels in the 4 groups. (B) Fasting insulin levels in the 4 groups. (C) HOMA-IR in the 4 groups. (D) ISI in the 4 groups. ** Compare with control group, P<0.01. # Compared with IH+NS group, P<0.05.

GLUT4 immunocytochemistry

Signals were visualized by DAB; brown staining represents GLUT4 and blue staining represents nuclei. The value of GLUT4 average optical density in control group, IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group were 0.29±0.01, 0.24±0.04, 0.24±0.03, and 0.25±0.02, respectively. The value of GLUT4 average optical density in the skeletal muscle was similar in rats of the IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group (P>0.05), and much less than that of the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical localization of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle for all groups (×400). * Compared with control group, P<0.05.

Effects of IH and rimonabant on GLUT4 mRNA expression

The mRNA of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle of the control group, IH group, IH+NS group, and IH+Rim group were 3.81±0.83, 0.75±0.23, 0.72±0.08, and 2.74±0.72, respectively. Compared with the control group, the GLUT4 mRNA levels in the IH groups and IH+NS group were significantly lower (P<0.05). Compared with the IH+NS group, the GLUT4 mRNA levels of the IH+Rim group were significantly increased (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in the GLUT4 mRNA levels between IH and IH+NS groups or between the control group and IH+Rim group (P>0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of IH and rimonabant on GLUT4 mRNA levels in skeletal muscle of rats. * Compared with control group, P<0.05. # Compared with IH+NS group, P<0.05.

Effects of IH and rimonabant on GLUT4 expression

The expressions of PM GLUT4 in control group, IH group, IH+NS group and IH+Rim group were 0.34±0.09 IU, 0.11±0.04 IU, 0.11±0.03 IU and 0.30±0.08 IU, respectively and the expressions of total GLUT4 were 0.68±0.08IU, 0.44±0.08 IU, 0.45±0.09 IU and 0.62±0.09 IU, respectively. Compared with control group, the expressions of PM GLUT4 and total GLUT4 were significantly lower in IH group and IH+NS group (P<0.01). Compared with IH+NS group, the expressions of PM GLUT4 and total GLUT4 were significantly higher in IH+Rim group (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in the expressions of PM GLUT4 and total GLUT4 between IH and IH+NS groups, as well as between control and IH+Rim group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of IH and rimonabant on GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle. (A) Western blots of PM GLUT4 and total GLUT4. (B) Ratios of PM GLUT4 to β-actin. (C) Ratios of total GLUT4 to β-actin. **: Compared with control group, P<0.01; ## Compared with IH+NS group, P<0.01 # Compared with IH+NS group, P<0.05.

Discussion

Numerous studies had shown an association between OSA and IR, as well as ECS and IR. However, the mechanisms by which OSA leads to IR and ECS regulates IR are not clearly known. So we aimed to assess the impact of IH, a main feature of OSA, and rimonabant, a CB1 receptor antagonist, on insulin sensitivity and expression of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle of rats. A number of findings have emerged from this study.

The impact of IH on weight change is very complex, and the results of different studies are inconsistent or even contradictory. Several laboratories have reported that compared with controls, body weight of mice or rats subjected to IH decreased [19,20]. Whereas other studies showed that body weight will continue to increase in mice or rats submitted to IH in a slower rate compared to control group [21,22].In this study, we observed the effect of IH on normal rats. Consistent with the later findings, we found less body weight gain in IH groups compared with control group rats for the 28 days of exposure. The different results may come from different IH paradigm, species of animal and age of animal, but the overall trend is that IH can cause relative weight loss. The factors that cause weight change are very complex and are not yet fully understood. The significant relatively weight loss observed in the IH group may be mediated by leptin increase and less food intake [23], because caloric restriction is protective against oxidative stress, potentially negating the injury of IH [21,24].

The contribution of IH on IR is debatable and some studies have different results. It was reported that chronic IH dramatically exacerbated pre-existing IR in diet-induced obesity mice, but have a minimal impact on lean mice without IR [25]. But other studies have shown that chronic IH can cause IR in both obesity and lean animals [6,26,27]. We have developed animal models to investigate the relationship between IH exposure and insulin sensitivity. It showed that IH will lead to higher levels of insulin concentrations, higher HOMA-IR and lower ISI, suggesting the presence of IR state after IH exposures. There are several potential mechanisms of IR during IH. First, under IH condition, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis was activated and then release more steroid hormone, which have effects leading to IR [16,28]. Second, IH can activate the sympathetic nervous system and lead to serum catecholamine concentrations increased, which can accelerate the lipolysis and result in the release of more free fatty acid (FFA). An evaluation of plasma FFA may result in accumulation of lipid in skeletal muscle and the liver [29]. At the same time, FFA may reduce the tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1(IRS-1) and insulin receptor substrate 2(IRS-2), and then decreasing insulin stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle and liver, and ultimately lead to IR [30]. In addition, overfull of catecholamines may inhibit secretion of insulin, prevent glucose uptake from muscle, increase gluconeogenesis and secretion of glucagon in the liver [31]. All of these are helpful in causing IR. Thirdly, IH may lead to IR by regulating secretion of adipokines, such as leptin and adiponectin [32]. Leptin may inhibit insulin secretion and decrease insulin sensitivity through both centrally and peripherally pathway [33]. Moreover, IH may decrease production of adiponectin [34]. As an insulin-sensitizing hormone, the decreased adiponectin level may further reduce insulin sensitivity. Fourthly, it is possible that IH induced IR comes from the IH induced oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Reactive oxygen species(ROS) molecules, the potential activators for inflammatory pathways, has been proved be a close relationship with inflammation and IR [35]. Lastly, the long-term hypoxia, which can damage pancreatic β-cells and reduce insulin secretion directly, may also contribute to development of glucose dysregulation [36].

As mentioned above, IH exhibits complex pathophysiologic mechanisms contribute to the progression of IR. In addition, our present study showed that the changes in GLUT4 mRNA expression and GLUT4 protein expression in skeletal muscle maybe a putative mechanism for the effects of IH on glucose dysregulation and insulin sensitivity. From our study, IH animals showed lower GLUT4 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in skeletal muscle, may also simultaneously happened in liver, adipose tissue and even throughout the body. The decreased expressions of GLUT4 mRNA level, total GLUT4 and PM GLUT4 may be an important mechanism for the inability to transport glucose to the intracellular space in animals under IH condition, resulting in higher blood insulin level and lower insulin sensitivity, as described in our experiments. One possible explanation for this finding may be related to decreased insulin effectiveness during IH. With the reduction of oxygen delivery to skeletal muscle in IH condition, the rate of oxidative metabolic and glycolysis slows down, thus the ability of insulin to dispose glucose decreases too [37]. Another explanation is related to ROS. In the process of IH, repeated hypoxia and re-oxygenation promotes the generation of ROS and induces oxidative stress [38]. ROS is not only a toxic by-product of material metabolism, but also a regulator of metabolic products, and can activate multiple inflammatory factors by NF-κB, such as IL-6 and TNF-α [3,31]. IL-6 and TNF-α can reduce the expression of GLUT4 and IRS-1, and reduce the glucose transport [39]. IH also leads to the catecholamine release increased by activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [40]. As mentioned before, the persistent excess catecholamine has been proved a powerful factor leading to IR through many ways. In addition, catecholamine can lead to IR through inhibition of translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface in muscles [28].

Many studies have indicated that CB1 antagonists contribute to improved IR. In rats, long-term treatment with rimonabant reduces weight gain and fat mass, and improves insulin sensitivity [41]. The effects of systemic rimonabant administration in the present study are consistent with those reported previously. As shown in this study, compared with the IH group and the IH+NS group, the weight gain of rats in the IH+Rim group was less early in the experiment and increased later in the experiment. We know of no reasonable explanation for this result. We speculate that the lower weight gain may result from the IH and rimonabant-induced feeding reduction, while the higher weight gain may be due to adaptation of rats to IH and the effects of rimonabant on the improving insulin sensitivity. In addition, the present study proved that taking the CB1 antagonist rimonabant can mitigate the effects of IH on weight gain and increase GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle of rats, especially the expression of PM GLUT4, thereby improving IH-induced IR. The immunohistochemistry result was different from that of Western blotting, suggesting that the effect of rimonabant on increasing expression of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle of rats subjected to IH was not statistically significant, but was only due to weakness in the quantitative detection of immunohistochemistry; however, we still believe that rimonabant can increase the expression of GLUT4 protein according to the results of Western blotting. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of the CB1 agonist on GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle have never been reported. Because skeletal muscle plays an important role in the regulation of glucose metabolism and CB1 receptor blockers can improve this function by increasing the glucose uptake, the actions of CB1 receptor antagonist are encouraging for the treatment of IR or diabetes mellitus in OSA patients [42]. However, the mechanism of the effect of CB1 receptor antagonist on the expression of GLUT4 is completely obscure, perhaps through a mechanism involving activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, modulation of plasma membrane Ca2+ and K+ channels, decreasing the binding activity of NF-κB and regulation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 ( SREBP-1) transcription [43,44].

Our study has several limitations: First, our model of IH only imitated the main characteristics, and did not imitate all the features of OSA, which also include sleep fragmentation, sleep deprivation, and microarousal and all these features may have effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Second, our study failed to provide adequate and systematic evidence to fully elucidate the effects of IH and rimonabant on insulin sensitivity, such as activation of sympathetic system, activation of oxidative stress, disorder of lipid metabolism, and abnormal secretion of inflammatory mediators and cytokines. Third, the mechanisms involved in the etiopathogenesis of IR are extremely complex and the present study only explored the relationship between expression of GLUT4 in skeletal muscle and insulin sensitivity, and does not completely elucidate the mechanism. All these problems will be the focus of our future research.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that IH induces slowing of body weight gain, as well as increase of fasting insulin levels and IR. Furthermore, lower levels of GLUT4 mRNA, total GLUT4, and PM GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle may participate in the development of IH-induced IR. It also showed that IH promotes the progression of IR, at least partly via activation of the ECS and blockade of CB1 receptors, could improve IH-induced IR by modulation the GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Source of support: This study was supported by a grant from the Health Bureau of Gansu Province (No. GSWSKY-2014-28)

References

- 1.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, et al. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botros N, Concato J, Mohsenin V, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2009;122:1122–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T, Zhou YT, Chen XN, Zhu AX. Putative role of ischemic postconditioning in a rat model of limb ischemia and reperfusion: involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014;47:738–45. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20142910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang D, Liu Z, Yang H, Luo Q. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on glycemic control and insulin resistance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis M, Punjabi NM. Effects of acute intermittent hypoxia on glucose metabolism in awake healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:1538–44. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91523.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu C, Jiang L, Zhu F, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia leads to insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance through dysregulation of adipokines in non-obese rats. Sleep Breath. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1144-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell. 2012;148:852–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50230–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo CH, Hwang H, Lee MC, et al. Role of insulin on exercise-induced GLUT-4 protein expression and glycogen supercompensation in rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;96:621–27. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00830.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kern M, Wells JA, Stephens JM, et al. Insulin responsiveness in skeletal muscle is determined by glucose transporter (Glut4) protein level. Biochem J. 1990;270:397–400. doi: 10.1042/bj2700397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu PT, Song Z, Zhang WC, et al. Impaired translocation of GLUT4 results in insulin resistance of atrophic soleus muscle. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:291987. doi: 10.1155/2015/291987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silvestri C, Ligresti A, Di Marzo V. Peripheral effects of the endocannabinoid system in energy homeostasis: adipose tissue, liver and skeletal muscle. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011;12:153–62. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun LJ, Yu JW, Wan L, et al. Endocannabinoid system activation contributes to glucose metabolism disorders of hepatocytes and promotes hepatitis C virus replication. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song D, Bandsma RH, Xiao C, et al. Acute cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) modulation influences insulin sensitivity by an effect outside the central nervous system in mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1181–89. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam DH, Lee MH, Kim JE, et al. Blockade of cannabinoid receptor 1 improves insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, and diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1387–96. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam J, Godlewski G, Earley BJ, et al. Role of adiponectin in the metabolic effects of cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade in mice with diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E457–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00489.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergholm R, Sevastianova K, Santos A, et al. CB(1) blockade-induced weight loss over 48 weeks decreases liver fat in proportion to weight loss in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:699–703. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang L, Luo K, Liu C, et al. Decrease in myostatin by ladder-climbing training is associated with insulin resistance in diet-induced obese rats. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:2342–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez D, Vasconcellos LF, de Oliveira PG, Konrad SP. Weight loss and brown adipose tissue reduction in rat model of sleep apnea. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinke C, Bevans-Fonti S, Drager LF, et al. Effects of different acute hypoxic regimens on tissue oxygen profiles and metabolic outcomes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:881–90. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00492.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiarpotto E, Bergamini E, Poli G. Molecular mechanisms of calorie restriction’s protection against age-related sclerosis. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:695–702. doi: 10.1080/15216540601106365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CY, Tsai YL, Kao CL, et al. Effect of mild intermittent hypoxia on glucose tolerance, muscle morphology and AMPK-PGC-1alpha signaling. Chin J Physiol. 2010;53:62–71. doi: 10.4077/cjp.2010.amk078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatsumi K, Kasahara Y, Kurosu K, et al. Sleep oxygen desaturation and circulating leptin in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Chest. 2005;127:716–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goto S, Takahashi R, Radak Z, Sharma R. Beneficial biochemical outcomes of late-onset dietary restriction in rodents. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1100:431–41. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drager LF, Li J, Reinke C, et al. Intermittent hypoxia exacerbates metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2167–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee EJ, Alonso LC, Stefanovski D, et al. Time-dependent changes in glucose and insulin regulation during intermittent hypoxia and continuous hypoxia. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:467–78. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2452-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iiyori N, Alonso LC, Li J, et al. Intermittent hypoxia causes insulin resistance in lean mice independent of autonomic activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:851–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1527OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton NM. Obesity and corticosteroids: 11beta-hydroxysteroid type 1 as a cause and therapeutic target in metabolic disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:154–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unger RH, Clark GO, Scherer PE, Orci L. Lipid homeostasis, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachek LI. Free fatty acids and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;121:267–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800101-1.00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Q, Yang QC, Zhou Q, et al. Effects of varying degrees of intermittent hypoxia on proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines in rats and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Cao ZL, Han F, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia from pedo-stage decreases glucose transporter 4 expression in adipose tissue and causes insulin resistance. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kojima S, Asakawa A, Amitani H, et al. Central leptin gene therapy, a substitute for insulin therapy to ameliorate hyperglycemia and hyperphagia, and promote survival in insulin-deficient diabetic mice. Peptides. 2009;30:962–66. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magalang UJ, Cruff JP, Rajappan R, et al. Intermittent hypoxia suppresses adiponectin secretion by adipocytes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:129–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam JC, Mak JC, Ip MS. Obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea and metabolic syndrome. Respirology. 2012;17:223–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pallayova M, Lazurova I, Donic V. Hypoxic damage to pancreatic beta cells – the hidden link between sleep apnea and diabetes. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77:930–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuo L, Clanton TL. Reactive oxygen species formation in the transition to hypoxia in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C207–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00449.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuo TB, Yuan ZF, Lin YS, et al. Reactive oxygen species are the cause of the enhanced cardiorespiratory response induced by intermittent hypoxia in conscious rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;175:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is, like IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45777–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokoe T, Alonso LC, Romano LC, et al. Intermittent hypoxia reverses the diurnal glucose rhythm and causes pancreatic beta-cell replication in mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:899–911. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindborg KA, Jacob S, Henriksen EJ. Effects of chronic antagonism of endocannabinoid-1 receptors on glucose tolerance and insulin action in skeletal muscles of lean and obese zucker rats. Cardiorenal Med. 2011;1:31–44. doi: 10.1159/000322826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindborg KA, Teachey MK, Jacob S, Henriksen EJ. Effects of in vitro antagonism of endocannabinoid-1 receptors on the glucose transport system in normal and insulin-resistant rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:722–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kong D, Song G, Wang C, et al. Overexpression of mitofusin 2 improves translocation of glucose transporter 4 in skeletal muscle of highfat dietfed rats through AMPactivated protein kinase signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:205–10. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furuya DT, Poletto AC, Freitas HS, Machado UF. Inhibition of cannabinoid CB1 receptor upregulates Slc2a4 expression via nuclear factor-kappaB and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 in adipocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;49:97–106. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]