Abstract

Background: Priority setting in healthcare is a key determinant of health system performance. However, there is no widely accepted priority setting evaluation framework. We reviewed literature with the aim of developing and proposing a framework for the evaluation of macro and meso level healthcare priority setting practices.

Methods: We systematically searched Econlit, PubMed, CINAHL, and EBSCOhost databases and supplemented this with searches in Google Scholar, relevant websites and reference lists of relevant papers. A total of 31 papers on evaluation of priority setting were identified. These were supplemented by broader theoretical literature related to evaluation of priority setting. A conceptual review of selected papers was undertaken.

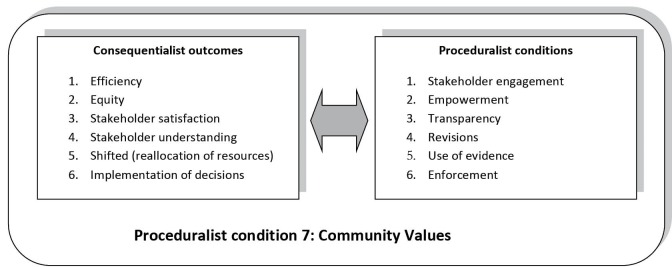

Results: Based on a synthesis of the selected literature, we propose an evaluative framework that requires that priority setting practices at the macro and meso levels of the health system meet the following conditions: (1) Priority setting decisions should incorporate both efficiency and equity considerations as well as the following outcomes; (a) Stakeholder satisfaction, (b) Stakeholder understanding, (c) Shifted priorities (reallocation of resources), and (d) Implementation of decisions. (2) Priority setting processes should also meet the procedural conditions of (a) Stakeholder engagement, (b) Stakeholder empowerment, (c) Transparency, (d) Use of evidence, (e) Revisions, (f) Enforcement, and (g) Being grounded on community values.

Conclusion: Available frameworks for the evaluation of priority setting are mostly grounded on procedural requirements, while few have included outcome requirements. There is, however, increasing recognition of the need to incorporate both consequential and procedural considerations in priority setting practices. In this review, we adapt an integrative approach to develop and propose a framework for the evaluation of priority setting practices at the macro and meso levels that draws from these complementary schools of thought.

Keywords: Priority Setting, Healthcare Rationing, Resource Allocation, Priority Setting Evaluation, Communitarianism

Background

Despite recognition of the importance of priority setting in healthcare, priority setting exercises in most settings are ad hoc rather than systematic.1,2 This has led to calls for strategies to improve priority setting practices in healthcare.3,4 Essential to improving priority setting practices is having a sense of direction; a standard to be aimed for, and against which to evaluate performance. The term evaluation is used here to refer to the systematic process whereby data are collected and analyzed to inform a judgment of worth or merit about an evaluand such as a process, programme or policy.5 Findings from evaluations find utility in improving decision-making, accountability, and resource allocation.6 An evaluation framework can provide concrete guidance to priority setting processes, highlight specific opportunities for improvement and determine whether priority setting practice has improved.6 However, there is no widely accepted priority setting evaluation framework, with challenges including little agreement on what counts as priority setting success,7,8 and different views on the underlying values that should be espoused in priority setting exercises.

In this paper, we conducted an interpretive thematic review of theoretical and empirical literature on and related to the evaluation of priority setting to develop a framework for the evaluation of priority setting practice at the macro (national) and meso (decentralized health systems and health facilities such as hospitals) levels. We aim to contribute to the relatively scarce literature and debate on frameworks for the evaluation of priority setting in healthcare.

Methods

Literature Search

We searched for 2 sets of literature; the first set aimed to obtain empirical and theoretical papers that focused on the evaluation of priority setting in healthcare while the second set aimed to obtain theoretical literature on related concepts. This second literature was necessitated by the observation that there is a dearth of literature on the evaluation of priority setting.

For the first set of literature, we searched in EBSCOhost, PubMed, CINAHL, and Econlit databases, as well as Google Scholar using the following key words: ‘evaluation’ or ‘evaluate’ or ‘success’ or ‘successful’ and ‘rationing’ or ‘planning’ or ‘priority setting’ or ‘health care rationing’ or ‘strategic planning’ or ‘decision making’ or ‘resource allocation’ or ‘budgeting’ or ‘health technology assessment.’ We carried out a manual search for relevant papers in the reference lists of selected papers. We then reviewed the titles and abstracts and full texts of identified papers to decide on final inclusion. We included papers that described and/or applied an evaluative framework for priority setting in healthcare and were written in the English language. Papers that did not meet these criteria were excluded. We did not apply any other exclusion criteria.

For the second set of literature we searched for theoretical literature on related concepts such as ethics, justice, deliberative democracy and procedural justice in healthcare. These concepts were identified from reading the papers identified in the first step. The following key words were used in the second step: ‘ethics’ or ‘ethical’ or ‘accountability for reasonableness’ or ‘justice’ or ‘just’ or ‘procedural justice’ or ‘deliberative democracy’ and ‘rationing’ or ‘priority setting’ or ‘health care rationing’ or ‘decision making’ or ‘planning’ or ‘resource allocation’ or ‘strategic planning’ or ‘budgeting’ or ‘health technology assessment.’

The selection of papers to include in the review was purposive rather than exhaustive because our aim was conceptual interpretation rather than prediction.9 It was therefore not necessary to locate every available paper given that the interpretations of our conceptual synthesis would not change if for example 10 rather than 5 papers containing the same concept were included, but rather would depend on the range of concepts found in the papers, their context, and whether they are in agreement or not. The number of papers reviewed was therefore dependent on ‘conceptual saturation.’9

Synthesis of Obtained Literature

We conducted a thematic review of theoretical and empirical literature on and related to the evaluation of priority setting. Thematic review involves the identification of prominent or recurrent themes in the literature, and summarizing the findings of different papers under thematic headings.9,10 We began with reading the selected papers, gradually identifying recurring ideas and concepts. We then constructed themes from these emergent concepts and ideas in an interpretive stage of the analysis that sought to integrate findings from across the papers into a coherent theoretical framework comprising a network of constructs and the relationships between them.11 Our approach to the thematic review is therefore interpretive rather than descriptive, and draws from “line of argument” approaches used in meta-ethnography12 and critical interpretive synthesis.11 This approach was applied to both sets of literature selected for this review.

Results

Given that the search for the first set of literature was more “systematic,” characteristics will be presented only for these. The second set of literature was broader and will be referenced and integrated with the first set of literature in the results and discussion sections of this review.

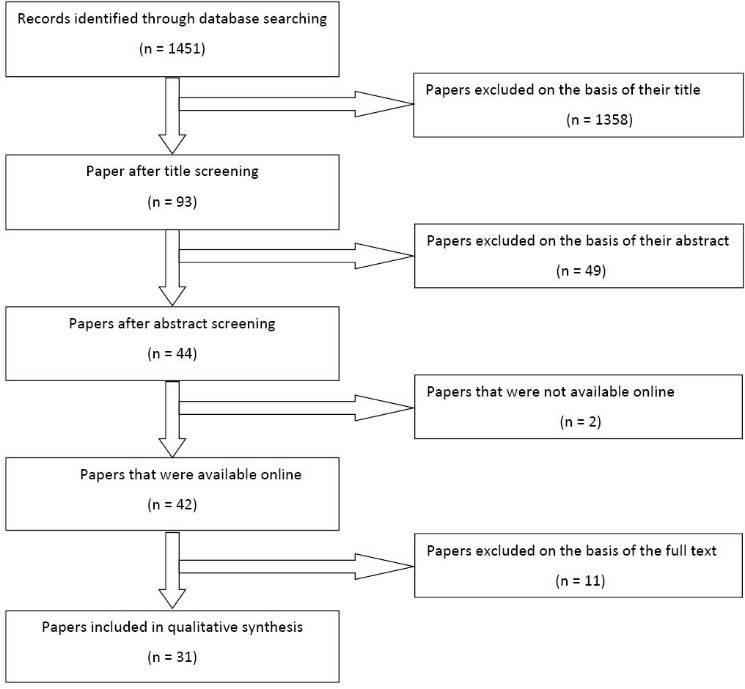

We identified a total of 1451 papers in the first step of the literature search. Of these, we excluded 1358 papers based on a review of their titles. We assessed the abstracts of the remaining 93 papers and excluded a further 49 papers. We excluded 2 more papers that were not available online. We then excluded 11 more papers, after assessing the full-text formats of the remaining 42 papers. We therefore included a total of 31 papers as part of the first set of literature for this review (Table 1). Figure 1 outlines the screening process of papers obtained through searches.

Table 1. Characteristics of Selected Papers .

| Paper | Type of Paper | Country | Setting | Priority Setting Activity | Study Objective a |

| Baerøe17 2009 | Conceptual | - | - | Resource allocation among patient groups | To develop a clinical decision-making framework |

| Bell et al18 2004 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian tertiary hospital | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process in a Canadian hospital in response to the SARS outbreak |

| Bruni et al19 2007 | Empirical | Canada | The Wait Times Strategy of Ontario, Canada | Resource allocation among patient groups | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process in a Canadian hospital |

| Danjoux et al20 2007 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian urban university academic health sciences centre | Adoption of new technology (endovascular aneurysm repair) | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process for the adoption of a new technology for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in a Canadian academic health sciences center |

| Dolan et al21 2007 | Conceptual | - | - | Resource allocation at all levels of the healthcare system | To explore the relevance of procedural characteristics that are important in legal studies and social psychology to social choice contexts and provide evidence on their relative importance. To explore why certain procedural conditions are considered important |

| Friedman22 2008 | Conceptual | - | - | No specific priority setting activity | To critically examine the accountability for reasonableness framework |

| Gallego23 2007 | Empirical | Australia | An Australian teaching and tertiary care hospital | Medicine selection | To describe and evaluate the medicine selection process for high cost drugs in an Australian hospital |

| Gibson et al24 2004 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian academic health science center | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To assist decision-makers in a Canadian academic health center to develop fair priority setting processes |

| Gibson et al25 2005 | Empirical | Canada | An Canadian urban academic health center | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To examine the influence of power dynamics among actors to the priority setting processes in a Canadian hospital |

| Gibson et al26 2006 | Empirical | Canada | A health region in Canada | Allocation of healthcare resources within the district/region | To evaluate the use of PBMA at a health region in Canada |

| Gordon et al27 2009 | Empirical | Argentina | An Argentinean acute care tertiary hospital | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process in an Argentinean hospital with particular attention to the appeal process |

| Greenberg et al28 2005 | Empirical | Israel | The National health insurer in Israel | Medicine selection | To evaluate the adoption of new technologies at the hospital level in Israel |

| Kapiriri and Martin29 2006 | Empirical | Uganda | A 1500 bed tertiary hospital in Uganda | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe the priority setting practice in a tertiary care hospital in Uganda and evaluate the process |

| Kapiriri and Martin30 2007 | Empirical | Uganda | Three hospitals, one in Norway, one Uganda, and one in Canada | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate priority setting practices at the macro, meso and micro levels of the health systems in Uganda, Norway, and Canada |

| Kapiriri and Martin6 2010 | Empirical | LMICs | LMICs | Resource allocation at all levels of the healthcare system | To develop a framework for successful priority setting in LMICs |

| Madden et al31 2005 | Empirical | Canada | Three Canadian teaching hospitals | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process in a Canadian hospital with particular attention to the appeal process |

| Maluka et al32 2011 | Empirical | Tanzania | A district in Tanzania | Allocation of healthcare resources within the district/region | To evaluate healthcare resource allocation at the district level in Tanzania |

| Martin et al33 2002 | Empirical | Canada | The advisory committee for the Ontario drug funding program of cancer care and the expert panel on Intracoronary Stents and Abciximab of the Ontario Cardiac Care Network | Assessment of health technology adoption in cardiac and cancer care | To evaluate the priority setting processes in a cardiac and cancer care center in Canada |

| Martin et al34 2003 | Empirical | Canada | Three Canadian teaching hospitals | Medicines selection | To describe and evaluate priority setting for medicine selection in a Canadian hospital |

| Martin et al35 2003 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian tertiary-care teaching hospital | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate the strategic planning process in a Canadian hospital |

| Mitton and Donaldson36 2003 | Empirical | Canada | Three Canadian health regions | Resource allocation within the district/region | To examine lessons learned from the evaluation of the implementation of PBMA in a Canadian health region |

| Mitton et al37 2003 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian hospitals’ surgical department | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To evaluate the priority setting process in a surgical programme in a Canadian hospital |

| Mori et al38 2012 | Empirical | Tanzania | Respondents from the Tanzanian health sector | Medicine selection | To evaluate the policy change to artemisinin combination therapy for the management of uncomplicated malaria |

| Peacock et al39 2006 | Conceptual | - | - | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | We describe checklists that can be used by decision-makers and clinicians for priority setting |

| Reeleder et al40 2005 | Empirical | Canada | Forty-six Canadian hospitals | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To evaluate hospital managers assessment on the fairness of priority setting process in their hospitals |

| Sharma et al41 2006 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian community hospital | Adoption health technology (advanced laparoscopic surgery) | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process for the adoption of advanced laparoscopic surgery at a Canadian hospital |

| Shayo et al42 2012 | Empirical | Tanzania | District health system | Resource allocation within the district/region | To examine challenges to fair priority setting in healthcare with a special focus on the role of ethnicity, gender, education, and wealth in Tanzania |

| Sibbald et al7 2009 | Empirical | Canada | International, national, and local respondents in the Canadian health system | Resource allocation at all levels of the healthcare system | To develop a framework for successful priority setting in healthcare |

| Sibbald et al8 2010 | Empirical | Canada | A Canadian urban community hospital | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To pilot a framework for successful priority setting in healthcare |

| Valdebenito43 et al 2009 | Empirical | Chile | A referral and teaching hospital in Chile | Resource allocation across hospital service areas and departments | To describe and evaluate the priority setting process in a Chilean hospital |

| Wailoo and Anand44 2005 | Empirical | United Kingdom | The public in a district in the United Kingdom | Resource allocation at all levels of the healthcare system | To explore the application of procedural preferences in healthcare priority setting processes |

Abbreviations: SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; PBMA, programme budgeting and marginal analysis; LMICs, low and middle income countries.

a The study objective column of the table are based on quotes from the respective papers

Figure 1.

Screening Process of Papers Obtained Through Searches.

Characteristics of Selected Papers

Of the 31 selected papers, 4 were conceptual papers, while the remaining 27 were based on empirical research. Of the 27 empirical papers, 7 were from developing country contexts, 19 were from developed countries while 1 documented cases from 1 developing country and 2 developed countries. Sixteen studies were carried out in Canada, 3 in Tanzania, 2 in Uganda, 1 each in Australia, Chile, Israel, United Kingdom, and Argentina and 1 was a multi-country study in Canada, Norway, and Uganda. Of the selected empirical papers, 18 focused on priority setting in hospitals, 6 on regional/district health systems, while 5 on national health systems.

Of the 18 papers that focused on hospitals, 12 evaluated the allocation of resources between hospital departments and service areas, 2 evaluated the allocation of resources among specified patient groups and 4 evaluated health technology acquisition decisions (Table 2). Of the 6 studies that focused on regional/district health systems, 5 evaluated allocation of resources within the region/district while 1 evaluated health technology assessment in a region/district. Of the 5 papers that focused on national health systems, 4 focused on allocation of resources at all levels of the healthcare system while 1 focused on health technology assessment. The paper that focused on a national health insurer also focused on health technology acquisition.

Table 2. Characteristics of Frameworks Used to Evaluate Priority Setting Practices in Selected Papers .

| Paper | Evaluative Framework Employed | Process Measures of Priority Setting | Outcome Measures of Priority Setting |

| Baerøe 2009 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Bell et al 2004 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Bruni et al 2007 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Danjuox et al 2007 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Dolan et al 2007 | An evaluative framework that employs procedural conditions |

Voice Consistency Accuracy Reversibility Transparency Neutrality |

- |

| Friedman 2008 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Gallego 2007 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Gibson et al 2004 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting |

Increase in the ease or resource allocation Improvement in decision-making capacity Optimized return on time invested, Fairness Feeling of engagement by stakeholders Use of reasonable justifications for decisions Consistency of process and decision-making, Publicity Relevance Appeals and revisions Enforcement |

Efficiency Shift in resources or Priorities Decisions support organizational strategic plan Decisions create conditions for organizational growth The organizational budget is balanced Stakeholder understanding The Staff are satisfied, positive or neutral to decisions The understanding of the organization is improved, The perception by the media and the public is positive or neutral, Improved support by the public, Improvement in the perception of the public of the organizations institutional accountability Improved healthcare integration through partnerships improved peer research/education peer recognition Emulation by other organizations |

| Gibson et al 2005 | Accountability for Reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Gibson et al 2006 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Gordon et al 2009 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Greenberg et al 2009 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Kapiriri and Martin 2006 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Kapiriri et al 2007 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Kapiriri et al 2010 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting | Involvement of a wide range of stakeholders, The use of appropriate and relevant rationales for decision-making publicity, The provision for an appeals mechanism | Efficiency, The quality of decisions is improved Resources are allocated more appropriately, Decision-making is based on evidence, Increases in the acceptance and confidence of the public of priority setting decisions, Increase in the satisfaction of stakeholder with decision-making processes, Public values are incorporated, Increase in awareness of priority setting processes by stakeholders, Reduction in disagreements, Reduction in resource wastage, Increase in internal accountability, Achievement of organizational goals and objectives, Increased priority setting capacity, Impact on health and practice Increase in healthcare investment |

| Madden et al 2005 | Accountability for Reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Maluka et al 2010 | Accountability for Reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Martin et al 2002 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Martin et al 2003 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Martin et al 2003 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Mitton and Donaldson 2003 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting |

One on one meetings Data should not be mechanically used Decision-making panel should choose their own decision-making criteria, Use of evidence in decision-making Decision-making panel should be representative |

Perceived usefulness of the process by participants increased uptake of the use of PBMA Improvement in knowledge among participants Proposals for re-design options Shifted priorities, Improvement in patient outcomes |

| Mitton et al 2003 | An evaluative framework that employs outcome measures | - | Usefulness re-allocation Improved patient outcomes |

| Mori et al 2012 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Peacock et al 2006 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting |

Publicity Appeals |

Establish organizational objectives Ensure implementation |

| Reeleder et al 2005 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Sharma et al 2006 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

| Shayo et al 2012 | An evaluative framework that employs procedural conditions | Stakeholder involvement Shared decision-making | - |

| Sibbald 2009 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting |

Engagement of stakeholders Transparency of processes Appropriate management of information, Values and context are considered, Revisions and appeals mechanisms |

Increased understanding by stakeholders Resources or priorities are reallocated or shifted Improvement in the quality of decision-making Increased satisfaction and acceptance by stakeholders Positive externalities |

| Sibbald 2010 | An evaluative framework that employs a combination of procedural conditions and outcome measures to evaluate priority setting |

Engagement of stakeholders Transparency of processes Appropriate management of information, Values and context are considered, Revisions and appeals mechanisms |

Increased understanding by stakeholders Resources or priorities are reallocated or shifted Improvement in the quality of decision-making Increased satisfaction and acceptance by stakeholders Positive externalities |

| Valdebenito et al 2009 | Accountability for reasonableness | Publicity of decisions and rationales, Relevance of decision-making rationales, Mechanism for revisions and appeals, Mechanism for enforcement of the first 3 conditions and the decisions | - |

Abbreviation: PBMA, programme budgeting and marginal analysis.

Evaluating Priority Setting

There is no universally agreed upon framework for the evaluation priority setting in healthcare and literature on this is scarce. Available literature mirrors the landscape of healthcare priority setting frameworks where 2 schools of thought dominate; consequentialism and proceduralism.2 Consequential frameworks focus on the outcomes of priority setting practices while procedural frameworks focus on the procedural aspects of priority setting practices.13 There is, however, increasing recognition of the need to adopt frameworks that draw from both these schools of thought.2,14 Of the 31 papers selected in the first set of literature for this review, 24 proposed the use of frameworks based on procedural conditions only, 1 proposed the use of a framework focused on outcomes only while 6 proposed the use of frameworks based on a combination of the two. Based on both sets of literature selected for this review, a number of consequentialist and proceduralist issues appear pertinent to priority setting process. These will be discussed in turn.

Consequential Approaches to Priority Setting

Consequential approaches to priority setting prescribe the use of a set of rational rules to set priorities and allocate resources in healthcare. Given that priority setting is a complex and value laden process, consensus on rational rules has been problematic.2 Despite this, allocative efficiency and equity feature prominently in normative literature as being relevant in the distribution of scarce healthcare resources.14,15

Allocative efficiency is achieved when resources are allocated so as to maximize the welfare of the community.16 Two main tools have been used to allocate resources-based on economic criteria.45-47 The first, cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) (which in this review shall subsequently be used to refer to both cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses as is common practice in literature) has been used to allocate resources in both developing and developed countries.48 The second economic tool is programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA), a systematic priority setting framework that aims to help decision-makers to identify the most efficient use of available resources while taking into consideration the opportunity costs of choices.49,50

However, the employment of allocative efficiency as the sole principle for priority setting could result in undesired outcomes.45,51 For example, allocatively efficient decisions would result in the treatment of the elderly having less preference because of their lower life-expectancy or the disabled given less preference because they have a lower capacity to benefit from treatment. Further, the current methods used to assess efficiency in healthcare resource allocation, such as CEA, employ simple aggregative algorithms that can result in undesired outcomes.14,45 The pitfalls of such aggregation rules are best exemplified by the case of the initial ranking lists of the Oregon Health Services Commission where tooth capping was found to be more cost effective than appendectomy, and was therefore given higher priority.51 There is significant consensus therefore that while maximizing outcomes is an important concern in allocating resources, it is also important that scarce resources are distributed equitably.14,45 There is no consensus in literature however on the conceptualization of equity in allocation of healthcare resources. There is, however, general agreement that, in publicly-funded healthcare systems, individuals or groups of individuals (patient groups) should make healthcare payments based on their ability to pay and receive healthcare benefits based on their healthcare needs.52 Norheim and colleagues14 have also proposed that resource allocation practices in healthcare should have a special concern for the worst off and should not be based on simple aggregation rules.

The prominence given to allocative efficiency and equity in normative literature on consequential principles of priority setting is however not reflected in empirical literature. Of the 31 papers in the first set of literature, only 2 prescribed the use of efficiency,while none prescribed the use of equity as a principle for the evaluation of priority setting. Of the two that prescribed the use of efficiency, none conceptualized it as allocative efficiency. Further, a range of outcome measures were used to evaluate priority setting process across different settings. The most commonly proposed outcomes (or consequences) of healthcare priority setting in the first set of reviewed literature are stakeholder satisfaction with the process, improvement in stakeholder understanding of the process, and that priority setting exercises result in reallocation (shifting) of resources (Table 3). The first two underline the recognition of the importance of stakeholders to not only accept or approve the adopted priority setting process, but also understand it. The requirement for the shifting of resources in essence means that priority setting procedures should be responsive to the dynamic environment of changing healthcare needs rather than perpetrate static historic considerations. It has also been proposed that priority setting procedures should reflect public values and/or gain public acceptance.6,24 Other priority setting outcomes that have been used to assess healthcare priority setting practices are the extent to which they further the achievement of the goals of the healthcare organization,39 the extent to which decisions are implemented,39 the extent to which decisions are based on evidence,6 improvements in decision-making quality and health outcomes.6,7,36

Table 3. Frequency of Use/Proposal of Procedural and Outcome Measures in Selected Papers .

| Process Measures of Priority Setting (No. of Use) | Outcome Measures of Priority Setting (No. of Use) |

|

Stakeholder engagement (27) Transparency (25) Provision for revision (25) Use of evidence/information (26) Enforcement (22) Empowerment (3) Consistency (2) Accuracy (1) Neutrality (1) Increase in the ease of resource allocation (1) Optimized return on time invested (1) One on one meetings (1) Data should not be mechanically used (1) Values and context are considered (2) |

Increased stakeholder understanding (3) Shifted or reallocated resources (6) Increased stakeholder satisfaction (4) Implementation of decisions (3) Improved patient outcomes (2) Efficiency (2) Improved quality of decision-making (1) Promotion of organizational objectives (1) Increased stakeholder acceptance (1) Increased stakeholder agreements (1) Reduction in resource wastage (1) Increased internal accountability (1) Increased priority setting capacity (1) Increased healthcare investment (1) Emulation by other organizations (1) Balanced budget (1) |

Procedural Measures of Priority Setting

Of the 31 papers selected in the first set of literature, 30 prescribe a range of procedural conditions for evaluation of priority setting practices. Based on these papers and on the broader literature selected in the second set of literature, procedural conditions that have received significant attention both in theory and practice include wider stakeholder engagement, empowerment of stakeholders, provisions for revisions of decisions, transparency of procedures, the use of relevant criteria, and the use of good quality evidence/information (Table 3). Other aspects of procedures that have been considered important include consistency in decision-making and enforcement of decisions. Even though some of these procedural measures appear to overlap with consequentialist rules, the distinction lies in where value is attached: procedural approaches value procedures as an end in itself, while consequentialist approaches value procedures to the extent that they are instrumental in achieving desired outcomes.

Procedural approaches to priority setting have drawn significantly from principles of deliberative democracy and are aimed at achieving procedural fairness. Deliberative democracy is a type of democracy where deliberation is central to decision-making.53 This differs from aggregative democracy where voting is key.

Both theoretical and empirical literature on priority setting processes reveals an emphasis on deliberation and public argument. A framework for the evaluation of priority setting procedure would therefore, evaluate, among others, the extent to which the process espouses principles of deliberative democracy. Attempts at evaluating deliberative processes can be traced to Habermas’s concepts of ideal speech situation and communicative competence.54 Habermas argues for free and un-coerced discussions among all stakeholders in collaborative decision-making processes. Habermas specifies four conditions to be met for the ideal speech situation to be achieved namely (1) That each subject should be allowed to participate in deliberation, (2) Each subject should be allowed to question presented proposals, (3) Each subject should be allowed to introduce their proposal into the deliberations, and (4) Each subject should be allowed to express their wishes, needs and attitudes.54

Building on Habermas’s concepts, Renn and Webler developed an evaluative framework for deliberative processes that is grounded on a normative theory of public participation.55,56 In their evaluative framework, Renn and Webler propose that deliberative processes should be judged on 2 meta-principles namely fairness and competence.56 The fairness principle is met if all stakeholders are provided with equal opportunities to engage and contribute to deliberations.56 These aspects include developing procedural rules, agenda setting, selecting the information and expertise that will be used in decision-making and assessing the validity of information.56 The competence principle is met if the right understanding and knowledge of the issues is achieved by the use and appropriate interpretation of information.56 The importance of access and use of quality information and evidence is therefore important.

More recently, the Renn and Webler framework together with later work by Beierle,57 was adopted by Abelson and colleagues58 to develop an evaluative framework for deliberative processes, that is comprised of three key procedural components namely: (1) the structure of the procedures (reasonable, legitimate, fair and responsive), (2) representation, and (3) the use of information.

The representation component emphasizes the extent to which a wide range of relevant stakeholders are included. This component also emphasizes access to decision-making processes by providing equal opportunities to those affected and the legitimacy of the process of selecting participants. The structure of process component focuses on the legitimacy, reasonableness, responsiveness and fairness of the decision-making process.59,60 The information component emphasizes the selection, source, use and quality of information that is used to make decisions.

Related to these ideas, Gutmann and Thompson61 have proposed 3 principles of deliberative democratic processes namely publicity, accountability and reciprocity. Publicity is said to be achieved when the rationales for decision-making are made explicit and publicly available. Accountability is achieved when decision-makers are held responsible for their decisions, such that it minimizes fraud and bias, while reciprocity is achieved when the structure of procedures is such that everyone respects and listens to each other’s views and ideas during decision-making. For this to happen, they argue, an environment that encourages participation has to be created.

Drawing from deliberative democratic principles, a framework that has gained prominence in evaluating the priority setting process is the ethical framework Accountability for reasonableness (AFR).3,62 AFR was the framework of choice for 21 of the 31 papers selected by this review. AFR relies on ‘‘fair deliberative procedures that yield a range of acceptable answers.’’63 AFR proposes that a fair and legitimate decision-making process should meet the following 4 conditions63 ; (1) Relevance, (2) Publicity, (3) Revisions, and (4) Enforcement.

The relevance condition requires that the rationales used in decision-making are reasonable.63 The publicity condition requires priority setting decisions and their rationales are made available to the public.63 The revisions and appeals condition requires that priority setting processes provide for a mechanism to challenge decisions and opportunities for improvement and revision of decisions when new evidence is made available.63 The enforcement condition requires that there be a mechanism to ensure that the three conditions are met.63

Another recurrent procedural principle is the incorporation of community values in priority setting processes. Of the 31 papers selected in the first set of literature, 30 included the community as part of the relevant range of stakeholders that should be included in priority setting processes (data not shown). The participation of the public in priority setting processes has not only been shown to be minimal, but has also generated significant debate.64 Debating points include how public engagement should be obtained, when it should be sought, and how public views should be incorporated in decision-making.

It has been proposed that priority setting should be based on the values of the community.65,66 Health organizations are seen as social organizations that exist to, among others, meet society’s needs.65-67 Under the communitarian claims approach, the citizen is required to “set the stage” for policy-makers to allocate resources by determining the procedural rules that policy-makers are expected to play by.66 The relationship between citizens and policy-makers is here considered to be a principal-agent relationship at a social level.65 Here citizens, who are assumed to have limited capacity to make technical healthcare decisions entrust this responsibility to healthcare decision-makers.68

Rowe and Frewer69 have proposed a framework to assess the degree of public participation in decision-making which has three participation levels namely: (1) Communication, (2) Consultation, and (3) Participation. In communication, information is passed from the decision-maker to the public such as through newspaper advertisements or announcements on notice boards. In consultation, information is passed from the public to the decision-maker without dialogue or interaction such as through client surveys or suggestion boxes.69 In participation, there is negotiation and dialogue between decision-makers and the public.69 Examples of participation methods include citizen juries or planning cells.

Attempts at incorporating public participation methods in healthcare decision-making have experienced a number of challenges. It has been argued that the public is unlikely to be objective especially on issues that directly affect them.64 It has also been argued that the public might not be competent to contribute to technical debates on healthcare decision-making.34 It has also been shown that the empowerment of the public is not automatic and that a number of factors come into play. For example, in Tanzania, similar to most other settings, effective participation of the public in priority setting decisions was influenced by gender, wealth, ethnicity and education.42 Members of the public who were male, more educated, and wealthier or shared ethnicity with decision-makers were more empowered in decision-making spaces.

Discussion

A number of recurrent concepts, that are considered critical in priority setting processes, can be drawn from the general literature on priority setting and evaluative frameworks.

First, priority setting is necessitated, and is an attempt to solve the fundamental economic problem of scarcity and choice.45,50 Frameworks for priority setting practice, and indeed their evaluation should therefore consider how best to achieve health system goals, given scarce resources.45 This essentially entails making choices such that desired outputs are maximized within the available resources. The choice of economic tools for priority setting is, however, dependent on, among others, the level of priority setting activity. For example, while CEA is more feasible at the national level, it might not be practical at the regional or hospital level. Challenges would include the limited technical capacity and availability of data required for these analyses.45 It is perhaps more feasible to use methods such as considering affordability alongside effectiveness and the budget impact of choices at lower levels of the health system (such as hospitals).

Second, the goal of maximizing desired outcomes must be traded-off against equity. Priority setting exercises in healthcare organizations should aim at achieving an appropriate balance between maximizing intended outcomes for a given resource level while considering equity.14,45 To achieve equity, the distribution of resources should be determined by needs rather than other factors such as ability to pay, favouritism or political consideration. Further, resource allocation should demonstrate a special concern for the worse off.14 The worse off can either be patient groups in a worse medical condition right now (eg, medical emergencies), or, alternatively, the ones whose complete life in terms of health will be worse if not treated now. The worse off should also include vulnerable patient groups. Vulnerability is often context dependent but could include groups such as the disabled, the elderly, children and women. Also, allocation should not be based on simple aggregating rules.

Third, in addition to efficiency and equity, other outcomes of priority setting processes are also important. While it is generally desirable to assess outcomes, attributing them to priority setting practices, especially in the short term, is likely to be problematic given that priority setting is a highly complex social process. Measures such as the achievement of health system/organizational goals and improvement of health outcomes cannot be easily attributed to specified priority setting activities except perhaps over the long run. Such measures would pose significant measurement challenges when adopted as measures for priority setting success. There is therefore a need for intermediate measures of outcomes that can be easily attributed to specified priority setting activities. Based on this, and on the frequency of recommendation from literature, we propose the following intermediate outcomes to be considered in the evaluation of priority setting practices: (1) Stakeholder satisfaction; the stakeholders should report their satisfaction with the priority setting process adopted, (2) Stakeholder understanding; each stakeholders should demonstrate an understanding of the structure, content and processes of priority setting, and (3) Shifted (reallocation of) resources; priority setting practices should result in real movement of resources and reflect change in priorities rather than historical allocations, and (4) Implementation; Priority setting processes should ultimately result in the accountable implementation of decisions.

Forth, given that priority setting entails adjudication over competing wants among groups of interested parties, procedural justice is a desired goal.33 We propose the following seven procedural conditions as key in evaluating priority setting process: (1) Stakeholder involvement; literature strongly suggests that policy-making processes and specifically priority setting processes are deemed to be fair and legitimate partly when the relevant stakeholders are effectively involved in the process. Specifically for priority setting, this relevant range of stakeholders include administrators/health managers, front line practitioners, patients and the community. As discussed previously however, the types of stakeholders that participate and the nature of participation is dependent on a number of considerations including the level of decision-making and the type of decision. (2) Empowerment; that the engagement of stakeholders should be such that they have the power to contribute to and influence decisions. Given the existence of power differences among actors in healthcare organizations,25 mechanisms should be there to minimize the effect of this power difference. These include for example giving each stakeholder equal opportunities to participate at different stages of the decision-making process such as establishing procedural rules, agenda setting, selecting the expertise and information to inform the process and providing an assessment of the validity of information, clearly defining and enshrining the role of the each stakeholder in priority setting rules and guidelines, ensuring accessibility of relevant information to each stakeholder to reduce information asymmetries and ongoing rather than one off or infrequent engagement of stakeholders since it has been shown that ongoing engagement builds trust over time. (3) Transparency; given that priority setting is a political process that affects a wide range of actors, the accountability and legitimacy of the process is enhanced by transparency. The procedures, decisions and reasons for the decisions should ideally be accessible to all stakeholders and communicated to them as well. (4) Revisions; the priority setting process should be dynamic enough to allow for revisions of decisions in the face of new information. To facilitate this, the process should have a provision for appeals to decisions. (5) Use of evidence; priority setting processes should endeavor to use quality information/evidence to inform decisions. (6) Enforcement; a legitimate priority setting process should provide mechanisms for an assurance that the other 6 conditions are met. (7) Incorporation of community values; priority setting is a highly political and value laden process.70 We are in favour of the communitarian claims argument that priority setting “rules” should be based on values determined by the community and then applied by decision-makers to set limits.65,66 We therefore see the incorporation of community values as an overarching procedural condition that should guide both the use of the aforementioned consequentialist and proceduralist principles in setting healthcare priorities.65,66 Priority setting practices should therefore provide for a process of obtaining citizen views about the principles of priority setting, which are then used by policy-makers as social agents to guide decision-making.

With regard to the mechanisms for incorporating community values, it should be appreciated that the suitability of public engagement mechanisms is highly context dependant and hence likely to vary across settings. For example, mechanisms that work in settings where individualism and equality are espoused are unlikely to work where society is characterized by hierarchy and interdependence.71 Similarly, settings characterized by sharp divisions based on wealth, ethnicity, power, and gender would also require different participation mechanisms compared to settings with less divisions. Further, community engagement mechanisms will also depend on the level of priority setting activity. While survey methods may find utility in eliciting community views at the national level, they might not be cost-effective or practical at the regional or hospital level. Similarly, it is perhaps more feasible to form decision-making committees that include community representatives at the regional or hospital level than at the national level. The types of decisions also influence the choice of community engagement mechanisms. Further, more “generic” decisions such as principles for decision-making in hospitals lend themselves better to community involvement compared to more specific and or/technical decisions such as selection of medicines to be included in the formulary list.

We propose that priority setting activities should incorporate participatory community engagement mechanisms rather than limit themselves to less interactive mechanisms such as one way communication. Examples include the incorporation of community members in hospital planning committees, the use of citizen juries72 and planning cells.58 While critics of community involvement in decision-making point out that community members lack understanding of technical issues and are hence incapable of meaningful contribution,34 we argue that the role of the community is not to directly contribute technical solutions, but rather to provide “meta-rules” or generic principles that guide decision-making .65,66 For example, the community is capable of providing meaningful input in eliciting the relative importance of principles such as severity of disease, efficiency and procedural conditions of priority setting.

To evaluate priority setting practice in healthcare organizations therefore, we propose a framework that views priority setting as being successful if (Figure 2): (1) the priority setting process take into consideration efficiency as well as equity and additionally, yield the following outcomes; (a) Stakeholder satisfaction, (b) Stakeholder understanding, (c) Shifted priorities (reallocation of resources), and (d) Implementation of decisions, (2) the priority setting process meets the procedural conditions of (a) Stakeholder engagement, (b) Stakeholder empowerment, (c) Transparency, (d) Use of quality information, (e) Revisions, (f) Enforcement, and (g) Incorporation of community values.

Figure 2.

Framework for Evaluation for Priority Setting.

Conclusion

We have proposed here a framework for the evaluation of priority setting practice in healthcare organizations that specifies both consequential and procedural conditional requirements for priority setting practices. It is unlikely that the consequential rules and procedural conditions proposed bear equal weight. Also, a major weakness of literature on evaluation of priority setting is their failure to engage with and incorporate evaluation theory.5 This weakness is indeed reflected in our proposed framework given that it is based on a synthesis of existing literature. Further work should look at the practical applicability of these conditions by relevant stakeholders in priority setting processes and their relative importance as well as explore the incorporation of evaluation theory. An overarching thesis of our framework is that priority setting practice should be guided by community values. We have anchored our proposed framework on this communitarian claims school of thought based on our belief that health organizations are social organizations that exist to serve citizens. What the communities need, and how this should be delivered to them should rightly come from the citizens themselves.

Acknowledgments

This work is published with the permission of the Director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Nairobi, Kenya.

Ethical issues

This study received ethics approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Nairobi, Kenya Ethics review committee.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The idea for the study and its design were conceived by EWB. EWB was responsible for the literature search. EWB and SC were responsible for the selection of papers for inclusion in the review and synthesis of the results. EWB was responsible for the preparation of the initial draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the draft manuscript and provided input to preparation of and approval for the final version of the report.

Authors’ affiliations

1KEMRI Centre for Geographic Medicine Research – Coast, and Welcome Trust Research Programme, Nairobi, Kenya. 2Health Economics Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. 3Centre for Tropical Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. 4Department of Paediatrics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Citation: Barasa EW, Molyneux S, English M, Cleary S. Setting healthcare priorities at the macro and meso levels: a framework for evaluation. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(11):719–732. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.167

References

- 1.Holm S. The second phase of priority setting. Goodbye to simple solutions BMJ. 2000;317:1000–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coulter A, Ham C. International experiences of rationing (or priority setting). In: Coulter A, Ham C, eds. The Global Challenge of Healthcare Rationing. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press; 2000.

- 3.Martin D, Singer P. A strategy to improve priority setting in health care institutions. Health Care Anal. 2003;11(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s108-006-0037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapiriri L, Martin DK. A Strategy to Improve Priority Setting in Developing Countries. Health Care Anal. 2007;15(3):159–167. doi: 10.1007/s108-006-0037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith N. Using evaluation theory in priority setting and resource allocation. J Health Organ Manag. 2012;26(5):655–671. doi: 10.1108/147761211256963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapiriri L, Martin D. Successful Priority Setting in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Framework for Evaluation. Health Care Anal. 2010;18(2):129–147. doi: 10.1007/s108-009-0115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK. Priority setting : what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:43. doi: 10.1186/14-6963-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibbald SL, Gibson JL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK. Evaluating priority setting success in healthcare: a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/14-6963-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1258/1355819052801804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S. et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noblit G, Hare R. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesising Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications; 1988.

- 13.Jan S. Proceduralism and its role in economic evaluation and priority setting in health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;108:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norheim OF, Cavallero E, Segall S. The ethics of priority setting in health: a review of principles, criteria and procedures we can all agree about. Bergen; 2007.

- 15. Brock D, Wikler D. Ethical Issues in Resource Allocation, Research, and New Product Development. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press and The World Bank; 2006. [PubMed]

- 16. Drummond M. Output measurement for resource allocation decisions in health care. In: McGuire A, Fenn P, Mayhew K, eds. Providing Health Care. The Economics of Alternative Systems of Finance and Delivery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991.

- 17.Baerøe K. Priority-setting in healthcare: a framework for reasonable clinical judgements. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(8):488–496. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.022285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell JA, Hyland S, DePellegrin T, Upshur RE, Bernstein M, Martin DK. SARS and hospital priority setting: a qualitative case study and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruni RA, Laupacis A, Levinson W, Martin DK. Public involvement in the priority setting activities of a wait time management initiative: a qualitative case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:186. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danjoux NM, Martin DK, Lehoux PN. et al. Adoption of an innovation to repair aortic aneurysms at a Canadian hospital: a qualitative case study and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:182. doi: 10.1186/14-6963-7-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolan P, Edlin R, Tsuchiya A, Wailoo A. It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it: Characteristics of procedural justice and their importance in social decision-making. J Econ Behav Organ. 2007;64(1):157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2006.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman A. Beyond accountability for reasonableness. Bioethics. 2008;22(2):101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallego G, Taylor SJ, Brien JA. Priority setting for high cost medications (HCMs) in public hospitals in Australia: a case study. Health Policy. 2007;84(1):58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson JL, Martin DK, Singer PA. Setting priorities in health care organizations: criteria, processes, and parameters of success. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):25. doi: 10.1186/14-6963-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson JL, Martin DK, Singer PA. Priority setting in hospitals: fairness, inclusiveness, and the problem of institutional power differences. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(11):2355–2362. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson J, Mitton C, Martin D, Donaldson C, Singer P. Ethics and economics: does programme budgeting and marginal analysis contribute to fair priority setting? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(1):32–37. doi: 10.1258/135581906775094280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon H, Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Priority setting in an acute care hospital in Argentina : A qualitative case study. Acta Bioethica. 2009;15(2):184–192. doi: 10.4067/s16-569x2009000200009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg D, Peterburg Y, Vekstein D, Pliskin JS. Decisions to adopt new technologies at the hospital level: insights from Israeli medical centers. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Priority setting in developing countries health care institutions : the case of a Ugandan hospital. 2006;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/14-6963-6-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Martin DK. Priority setting at the micro- , meso- and macro-levels in Canada , Norway and Uganda. Health Policy (New York) 2007;82:78–94. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madden S, Martin DK, Downey D, Singer PA. Hospital priority setting with an appeals process: a qualitative case study and evaluation. Health Policy. 2005;73(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maluka S, Kamuzora P, San M. et al. Decentralized health care priority-setting in Tanzania: evaluating against the accountability for reasonableness framework. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin DK, Giacomini M, Singer PA. Fairness, accountability for reasonableness, and the views of priority setting decision-makers. Health Policy. 2002;61(3):279–290. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin DK, Hollenberg D, Macrae S, Madden S, Singer P. Priority setting in a hospital drug formulary: a qualitative case study and evaluation. Health Policy. 2003;66:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin DK, Shulman K, Santiago-Sorrell P, Singer P. Priority-setting and hospital strategic planning: a qualitative case study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(4):197–201. doi: 10.1258/135581903322403254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitton CR, Donaldson C. Setting priorities and allocating resources in health regions: lessons from a project evaluating program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) Health Policy. 2003;64(3):335–348. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitton C, Donaldson C, Shellian B, Pagenkopf C. Priority setting in a Canadian surgical department; a case study using program budgeting and marginal analysis. Can J Surg. 2003;46(1):23–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori AT, Kaale EA. Priority setting for the implementation of artemisinin-based combination therapy policy in Tanzania: evaluation against the accountability for reasonableness framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peacock S, Ruta D, Mitton C, Donaldson C, Bate A, Murtagh M. Using economics to set pragmatic and ethical priorities. BMJ. 2006;332(7539):482–485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7539.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeleder D, Martin DK, Keresztes C, Singer PA. What do hospital decision-makers in Ontario, Canada, have to say about the fairness of priority setting in their institutions? BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma B, Danjoux NM, Harnish JL, Urbach DR. How are decisions to introduce new surgical technologies made? Advanced laparoscopic surgery at a Canadian community hospital: A qualitative case study and evaluation. Surg Innov. 2006;13(4):250–256. doi: 10.1177/1553350606296341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shayo EH, Norheim OF, Mboera LE. et al. Challenges to fair decision-making processes in the context of health care services: a qualitative assessment from Tanzania. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valdebenito C, Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Hospital priority setting in a mixed public/private health system: a case study of a Chilean hospital. Acta bioethica. 2009;15(2):193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wailoo A, Anand P. The nature of procedural preferences for health-care rationing decisions. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hauck K, Smith PC, Goddard M. The Economics of Priority Setting for Health Care: A Literature Review. World Bank HNP discuss. Paper series. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2004/09/5584467/economics-priority-setting-health-care-literature-review. Published September 2014.

- 46.Mitton C, Donaldson C. Tools of the trade: a comparative analysis of approaches to priority setting in healthcare. Heal Serv Manag Res. 2003;16:96–105. doi: 10.1258/095148403321591410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitton C, Peacock S, Donaldson C, Bate A. Using PBMA in health care priority setting: description, challenges and experience. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(3):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baltussen R, Brouwer W, Niessen L. Cost-effectiveness analysis for priority setting in health: penny-wise but pound-foolish. Int J Technol Assess Heal Care. 2005;21(4):532–534. doi: 10.1017/s0266462305050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsourapas A, Frew E. Evaluating ‘success’ in programme budgeting and marginal analysis: a literature review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(3):177–183. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitton C, Donaldson C. Resource allocation in health care: health economics and beyond. Health Care Anal. 2003;11(3):245–257. doi: 10.1023/b:hcan.0000005496.74131.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardon D. Setting health care priorities in Oregon Cost-Effectiveness meets the rule of rescue. J Am Med Assoc. 1991;265:2218–2225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E. Equity in the finance and delivery of health care: concepts and definitions. In: Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Rutten F, eds. Equity in the Finance and Delivery of Health Care: An International Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- 53. Elster J. Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

- 54. Habermas J. The Theory of Communicative Action. Boston: Beacon Press; 1984.

- 55.Renn O. Risk communication: Towards a rational discourse with the public. J Hazard Mater. 1992;29(3):465–519. doi: 10.1016/0304-3894(92)85047-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Webler T. “Right” discourse in citizen participation: an evaluative yardstick. In: Renn NO, Wiedelmann P, eds. Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse. Boston, Ma: Kluwer Academic Press; 1995.

- 57. Beierle T, Cayford J. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions. Washington DC: Routledge; 2002.

- 58.Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):239–251. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pratchett L. New fashions in public participation: Towards greater democracy? Parliam Aff. 1999;52:617–633. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Crosby N. Citizens’ juries: One solution for difficult environmental questions. In: Renn NO, Wiedelmann P, eds. Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse. Boston, Ma: Kluwer Academic Press; 1995.

- 61. Gutmann A, Thompson D. Why Deliberative Democracy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Universiy Press; 2004.

- 62.Maluka S, Kamuzora P, Sansebastián M. et al. Implementing accountability for reasonableness framework at district level in Tanzania : a realist evaluation. Implement Sci. 2011;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Daniels N, Sabin J. Setting Limits Fairly: Can We Learn to Share Medical Resources? New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 64.Mitton C, Smith N, Peacock S, Evoy B, Abelson J. Public participation in health care priority setting: a scoping review. Health Policy. 2009;91(3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mooney G. Communitarian claims’ as an ethical basis for allocating health care resources. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(9):1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mooney G. Challenging Health Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

- 67.Mooney GH, Blackwell SH. Whose health service is it anyway? Community values in healthcare. Med J Aust. 2004;180(2):76–78. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mooney G. Communitarian claims and community capabilities: furthering priority setting? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rowe G, Frewer J. Public participation methods: a framework for evaluation. Sci Technol Hum Values. 2000;25(1):3–29. doi: 10.1177/016224390002500101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klein R. Puzzling out priorities. BMJ. 1998;317:959–960. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7164.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sepehri A, Pettigrew J. Primary health care, community participation and community-financing: experiences of two middle hill villages in Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(1):93–100. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lenaghan J. Involving the public in rationing decisions The experience of citizens juries. Health Policy. 1999;49:45–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]