Abstract

Inequalities in the social determinants of health (SDH), which drive avoidable health disparities between different individuals or groups, is a major concern for a number of international organisations, including the World Health Organization (WHO). Despite this, the pathways to changing inequalities in the SDH remain elusive. The methodologies and concepts within system science are now viewed as important domains of knowledge, ideas and skills for tackling issues of inequality, which are increasingly understood as emergent properties of complex systems. In this paper, we introduce and expand the concept of adaptive policies to reduce inequalities in the distribution of the SDH. The concept of adaptive policy for health equity was developed through reviewing the literature on learning and adaptive policies. Using a series of illustrative examples from education and poverty alleviation, which have their basis in real world policies, we demonstrate how an adaptive policy approach is more suited to the management of the emergent properties of inequalities in the SDH than traditional policy approaches. This is because they are better placed to handle future uncertainties. Our intention is that these examples are illustrative, rather than prescriptive, and serve to create a conversation regarding appropriate adaptive policies for progressing policy action on the SDH.

Keywords: Health Equity, Social Determinants of Health (SDH), Health Policy, Adaptive Policies

Introduction

Starting with the Black Report 35 years ago, many major government inquiries into population health have recommended policy change across a broad range of key areas in order to reduce inequality in the distribution of the social determinants of health (SDH). Popular targets for reform include: early childhood services; education and training; tackling poverty; and the redistribution of wealth.1-4 Policy recommendations regarding the SDH span changes to policy processes, such as advocating the use of health inequality impact assessments and encouraging the integration of health into diverse policies (ie, Health in All Policies),5 to changes in specific policies ranging from child and maternal nutrition to the provision of care to the elderly.1-4 The authors of these reports anticipate that implementation of such policy adjustments will move us closer to the goal of reducing inequalities in the distribution of the SDH.

Alongside these developments there has been a growing interest in systems science and the insights it might provide for action on the SDH.6,7 The health of individuals and populations is affected by broad social factors that influence the conditions in which people grow, live, work, and age.3,8 Hence, social inequalities – and the inequalities in health outcomes associated with them – are now understood to emerge from complex local, regional, national, and global systems which are inextricably linked.9,10 Increasingly, researchers in this field argue that inequalities in the SDH cannot be ameliorated “without an analytic focus on how these complex systems act together (and) coalesce to produce them.”10

Systems science is a broad term for a range of methodologies and perspectives that seek to elucidate the behavior of complex systems and inform efforts to address these problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that systems thinking provides a more complete understanding of real-world settings and ways to produce change.11 In healthcare, systems-based approaches have been applied in a range of areas, including general practice,12 and health service organisations.13,14 There have also been attempts to apply a systems lens to complex public health problems, such as tobacco control15 and obesity.16,17 Such approaches are a move away from linear and simple input/output models towards dynamic models, as a means to generate policies that are adaptive to changing state of the system.

The concept of ‘adaptive policies’ has received increasing attention in public policy as a means to generate policies that can deal with both the complexity and uncertainty involved in governing wicked problems.18,19 It is argued that a dynamic, self-adjusting feedback system (which characterises many of the wicked problems that drive poor social and, in turn, health inequalities) cannot be effectively governed by a static, unbending policy.20 That is, a static policy is unlikely to help decision-makers reach the desired ends, particularly over time. Static policies have no facility to deal with any unintended consequences of their implementation, including those which exacerbate the target problem, or the creation of new and unexpected problems.18,21,22 Adaptive policies which encompass a degree of ‘learning’ can shift according to the state of the system and are therefore seen as potentially being both more effective and cheaper (in the long run) than static policies.18,21

In particular, adaptive policies are considered to be a more appropriate policy design structure for dealing with uncertain future scenarios when compared to static policies.18,21 This is not because adaptive policies, or the people making them, are better able to predict outcomes. It is because adaptive policy refers to a policy structure that attempts to be flexible across a range of anticipated scenarios, and can reasonably expect to deal well with unanticipated changes in trends.22 The ‘adaptive policy’ response to managing the inherent risk of acting within a complex system, such as future dynamics changes in the social determinants to health, embraces the notion of shifting and responding to unanticipated change.

In this paper, we introduce and expand the concept of adaptive policies to reduce inequalities in the distribution of the SDH. We then outline two illustrative examples of adaptive policies to demonstrate their potential for reducing SDH inequality. We anticipate that this paper will contribute to creative thinking for policy change in this area.

Adaptive Policies

Policy is defined as “what governments choose to do and or not to do. Hence, public policy is concerned primarily with governmental action and inaction.”23,24 In an extension of this definition, ‘adaptive policy’ introduces the notion that a policy includes within itself instruments for monitoring and adaptation in the face of uncertainty. Adaptive policies are, therefore policies that have both (a) Internal instruments or methods to responds to change over time, and (b) An explicit learning orientation for the people charged with policy implementation.19

The term ‘adaptive policy’ did not arise until the 1980s, though the concepts at the heart of adaptive approaches were first articulated in the early 1900s with regard to the need for experimentation in policy to encourage continual learning and adjustments.25,26 In the 1980s, Rondinelli argued that policy must “cope more effectively with… uncertainty and complexity… requiring an adaptive approach that relies on strategic planning, on administrative procedures that facilitate innovation, responsiveness and experimentation and decision-making processes that join learning with action.”27 Since this time, the need for learning and adaptation have become well-acknowledged in natural resource management and environmental policy discourse,28 public policy,29-31 and in public health policy discourse.11

Swanson et al18,22 outlines 4 key features of adaptive policies:

They can perform well under a range of anticipated conditions with little or no alteration.

They include monitoring processes and identify when changes in context are significant enough to affect performance.

They have built-in triggers for adjustment (these can include deliberations for determining policy adjustments, review process and so forth) which means that they can maintain performance or terminate when no longer needed.

Ideally, they can also accommodate unforseen changes in context, for which the policy was not originally designed, ensuring that policy goals can be achieved despite unanticipated issues.

A commonly understood illustrative example of an adaptive policy, which uses built-in triggers and monitoring processes to adapt and adjust, is the monetary system and the function of the Reserve Bank of Australia. The role of the Reserve Bank is to stabilise the currency under uncertain shifting global economic conditions, thereby protecting the welfare of citizens. This role is adaptive because it has a built-in monitoring process – the Board of the Reserve Bank meets every month to evaluate economic conditions – and a flexible policy lever – the Reserve Bank can choose to raise or lower interest rates. Without requiring any additional policy to be passed by any level of government in Australia, the Reserve Bank can push or pull its policy lever in the direction it believes will be most effective at placing saving, spending and investment behaviour within optimal parameters.

Adaptive Policies for Addressing Inequalities in the Social Determinants of Health

In the remainder of the paper, we provide illustrative examples of adaptive policy approaches for addressing inequalities in the SDH. These examples are designed to be illustrative, rather than prescriptive, and to broaden the discourse on the potential benefits of adaptive policies. As inequalities in the SDH are dynamic (ie, they change over time and across location), the strategic use of adaptive policies may help to mitigate them without the need for successive changes to legislation or regulation. Indeed, research has shown that static policies, over time, can drift substantially from their original mandate.32 Adaptive policies, in this situation, can be self-adjusting. A recent WHO report20 notes the potential of adaptive policies for addressing SDH (in this instance, alcohol). Drawing on systems science, the report argues that policies must be dynamic if they are to address the complexity of current health challenges.

1. An Adaptive Approach to Food and Fuel Subsidisation – an Extension of the Indian Ration Card

India is home to 400 million people living on incomes under $1.25 per day and 190 million people who are chronically under-nourished.33 Since 1960 the Indian Government has administered a ration card system with the aim of providing a subsidised minimum of food and fuel to the entire Indian population.34 The ration card is available to all households and has three different categories based on household income level. Each ration card entitles households to a set amount of subsidised wheat, rice, sugar, kerosene and LP Gas which is purchased from government-run Fair Price Stores.34 There are some 500 000 Fair Price Stores across India which operate in parallel to traditional stores in which prices are set by the market.

India has undergone a sustained period of development characterised by increasing per capita gross domestic product (GDP), urbanisation and some widening of inequalities.35,36 As a result of this development, more households consume a larger amount of unsubsidised food and a smaller proportion of households are reliant on ration cards than was the case 20 years ago.

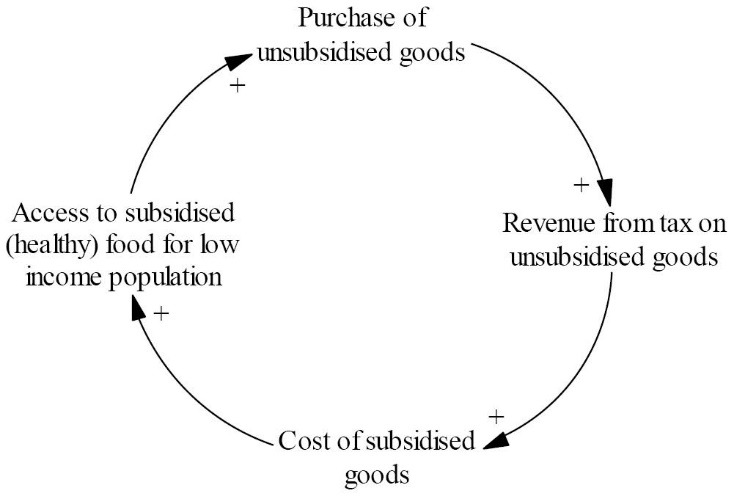

This change in consumption patterns presents an opportunity for the implementation of an adaptive policy. At present, each of the States in India sets the prices of the ration goods. Prices are changed infrequently and price increases are the occasion of much political debate, even among wealthier middle-classes. A small tax on the sale of unsubsidised goods could be directed to reducing the cost of subsidised goods. The positive feedback loop of such a policy is presented in Figure.

Figure.

Positive Feedback Loop Illustrating the Potential for the Subsidy to Act as an Adaptive Policy to Drive up Access to Health Food Overall.

This would be an ‘adaptive’ policy because the amount of the subsidy would increase in line with increases in unsubsidised consumption. Thus consumption of market priced grains by the middle class would further reduce the cost of subsidised grains for the poor. In effect the successes of India’s development are utilised to reduce the inequality caused by that development.

Technological advancements in the ration card system also make a policy of this type feasible. To combat corruption Indian states have begun to link ration cards to bank accounts and other forms of identification.34 When the ration cardholder purchases goods from a Fair Price Store, they do so at full price and the subsidy is automatically credited to a nominated bank account. The subsidy credited to the consumer could increase incrementally as consumption of market price grains increase. Of course a minimum subsidy level would need to be set to ensure that the subsidy did not decrease from existing levels.

This policy fits the criteria for adaptive policies outlined above in that: (1) It performs well under changing conditions as the economic circumstances of the country change, (2) Monitors consumption of unsubsidised goods, (3) Triggers an increase in the amount of subsidy given on subsidised goods.

2. An Adaptive Approach to Educational Inequalities

Education is now understood to be both a key determinant of health and an important source of social and health inequalities, due to differences in the quality of education received by different groups.3,4 Inequalities in educational access, quality and outcomes affects physical and mental health, as well as later income and employment.4 Many western industrialised countries have developed dual, or tiered, education systems. In addition to universally available public systems, countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia have private schooling systems which, in addition to sourcing income from private sources through fees, can also receive government funding.37

As private services grow, however, public services have tended to deteriorate, leaving those without the means to purchase private ones with a lower quality of service.38-41 Dual education systems can drive inequalities, as those without the means to buy private education receive an increasingly lower standard of education, which has flow-on effects for the types of employment they can secure later and the income employment provides.38,39 These tiered systems can, over time, generate very large disparities between groups, as public education systems become ‘residualised.’ That is, a public service only provided for the poor, as a minimum safety net.38,42

An adaptive approach to removing disparities between public and private systems would be to make public funding of private schools contingent on public school performance. When public schools perform well (thereby closing the gap in education outcomes, and their subsequent flow-on effects for social inequalities), private schools receive more funds. When public schools perform poorly, private schools receive less funds. In turn, government funding of public schools would need to be performance-based in a way that provides additional support for low socio-economic areas or schools where students are ‘falling behind.’ Here a set of review processes is triggered, as occurs with the Reserve Bank, with the authority to authorise further action (eg, more resources such as teachers, a change in structure and so on).

Taking the Australian context as an example, government funding of public and private schools could be distributed inversely on the basis of standardised test performance. Currently, all Australian Schools take part in the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).43 The NAPLAN tests aim to establish the proficiency of students in a range of skills deemed essential for children to progress, both through school, and their later working life. They are undertaken nationwide on a yearly basis. An adaptive education policy in Australia would establish a funding scheme for public schools whereby schools that perform poorly on NAPLAN’s receive additional resources. This is in stark difference to American systems, for example, where performance-based funding (where funding is given only when students perform well) has led to ‘gaming’ of the system and a failure to raise or equalise educational outcomes.44,45

In addition, a set of contingency measures could be ‘triggered’ through the monitoring of an individual school’s performance over time. If a school continues to perform poorly despite increased investment further support measures, or review processes, could be triggered when certain thresholds are reached (ie, a failure to improve performance three years in a row). Review committees would be able to authorise further action (eg, more resources such as teachers, a change in structure and so on). These contingency policies, plans and programs might target non-school dimensions of students’ lives, in addition to the school environment, in recognition of the fact that school performance is influenced by a wide range of social and cultural factors. Similarly, poor performing schools that receive an influx of resources could be encouraged to invest in outreach efforts, in addition to measures that secure high quality teachers and learning environments within the school. Finally, such an approach would need to be accompanied by a capping on the amount of revenue that private schools could source from private sources (ie, fees), to stop inequalities growing at the ‘top end’ of the social gradient. Indeed, adaptation was arguably at the heart of the Gonski Review of the education system in the Australian context, which suggested that school resourcing needed to be reviewed on a regular basis to enable schools and teachers to adapt to local needs and changes in the environment.46

The adaptive approach to tackling educationally driven inequities described above is not dissimilar from educational reforms proposed in the United States in the 1970s. At the time, over 50% of US education funding was localised – drawn from property taxes in local school districts. This approach perpetuates inequalities, driven by variations in property taxes and values between poor and wealthy neighbourhoods. Here, schools in low socio-economic districts with low property values are able to raise less funds relative to school districts in wealthier areas, thereby creating and driving inequalities in education standards. A ground-breaking report on educational inequalities in the United States, known as the Fleischmann Report,47 argued that more equality could be achieved through a centralised funding scheme; the “Fleischmann Commission proposed that New York become the first state in the nation to take over all the financial powers of its many local school boards.”47,48 Once state governments acquired the funds, they would redistribute the money so that the lower 65% of the state’s school districts would rise to the spending levels of those that were in the upper 35%. Initially, rich districts could keep spending at current rates while the poor districts catch up. After that, a cap would be placed whereby wealthy areas would be forbidden to raise more money – preventing inequity from reentering the system. Moreover, districts with substantial numbers of children performing poorly in key areas, were to receive a 50% bonus for each such child.47

While this example deals somewhat narrowly with the issue of disparities between public and private education, it exhibits the following characteristics: (1) requires little alteration once put in place, (2) monitors school performance and (3) triggers adjustments to school funding in accordance to this performance, and (4) has safeguards against unexpected outcomes through triggering review processes (thus dealing with future uncertainty by ensuring that issues are considered as they arise).

Conclusion

Reducing inequalities in the distribution of the SDH is highly complex. While linear relationships are easy to conceptualise, focusing on linearity takes us further away from understanding how to create change in real world settings. Moving the agenda forward requires more sophisticated policy approaches that can deal with the complex, nonlinear relationships that drive inequality. In this paper, we have provided examples of policies that have built-in adaptation or learning. This, we contend, is a potentially useful feature for the design of effective policies for redressing inequalities in the SDH; social inequality is a dynamic problem, requiring flexible and adaptive policy responses. Care must be taken, however, to ensure that adaptive policies are themselves changed in the face of unanticipated future scenarios.

Of course, adaptive policies (like static ones) are not immune to the political process. Fleischmann’s recommendations, for example, were not implemented in full due to political resistance. However, once implemented such policies (theoretically) should withstand political pressure and lobbying better than policies which require continuous cycles of legislation – providing they are implemented in full at the outset. This is because once they are in place, there are fewer opportunities for political pressure and influence as they are not continuously open for review as static policies often are because of their need for updating through legislative change. Hence, despite the challenges of realpolitik, policy experts concerned with inequality should find adaptive approaches highly valuable.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GC drafted the manuscript, BC and NC assisted with the development of examples. EM designed the systems diagrams. All authors reviewed and refined the paper.

Authors’ affiliations

1Regulatory Institutions Network, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia. 2Centre for Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. 3Maths and Science Institute, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Citation: Carey G, Crammond B, Malbon E, Carey N. Adaptive policies for reducing inequalities in the social determinants of health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(11):763–767. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.170

References

- 1.Bambra C, Smith KE, Garthwaite K, Joyce KE, Hunter DJ. A labour of Sisyphus? Public policy and health inequalities research from the Black and Acheson Reports to the Marmot Review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:399–406. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.111195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Black D. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. London: Penguine; 1982.

- 3. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). Closing the Gap in a Generation. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

- 4. Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. Strategic Review of Health Inequalitites in England post-2010. London; 2010.

- 5.Carey G, Crammond B, Keast R. Creating change in government to address the social determinants of health: how can efforts be improved? BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1087. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baum F, Lawless A, Williams C. Health in All Policies from International Ideas to Local Implementation: Policies, Systems and Organizations. In: Clavier C, de Leeuw E, eds. Health Promotion and the Policy Process. London: Oxford University Press; 2013:188–217.

- 7.Fisher M, Milos D, Baum F, Friel S. Social determinants in an Australian urban region: a “complexity” lens. Health Promot Int. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lalonde M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians: A Working Document. Ottawa: Ministry of National Health and Welfare; 1974.

- 9.Mahamoud A, Roche B, Homer J. Modelling the social determinants of health and simulating short-term and long-term intervention impacts for the city of Toronto, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGibbon E, McPherson C. Applying Intersectionality & Complexity Theory to Address the Social Determinants of Women’s Health. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/27217. Accessed November 10, 2014. Published 2011.

- 11. De Savigny D, Adam T, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=476146. Accessed November 11, 2014. Published 2009.

- 12.Martin C, Sturmberg J. General practice - chaos, complexity and innovation. Med J Aust. 2005;183:106–109. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordon M, Lanham HJ, Anderson RA, McDaniel Jr RR. Implications of complex adaptive systems theory for interpreting research about health care organizations. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:228–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trochim WM, Cabrera DA, Milstein B, Gallagher RS, Leischow SJ. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:538. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Best A, Clark P, Leischow S, Trochim W. Greater than the sum of its parts. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007.

- 16.Johnston LM, Matteson CL, Finegood DT. Systems science and obesity policy: a novel framework for analyzing and rethinking population-level planning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1270–1278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vandenbroeck I, Goossens J, Clemens M. Foresight Tackling Obesities: Future Choices—Obesity System Atlas. UK: Foresight Study; 2007.

- 18.Swanson D, Barg S, Tyler S. et al. Seven tools for creating adaptive policies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2010;77:924–939. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2010.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker WE, Rahman SA, Cave J. Adaptive policies, policy analysis, and policy-making. Eur J Oper Res. 2001;128:282–289. doi: 10.1016/s0377-2217(00)00071-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on alcohol and health-2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112736. Accessed July 20, 2015. Published 2014.

- 21. Meadows D. Thinking in Systems. USA: Sustainability Institute; 1999.

- 22. Swanson D, Bhadwal S. Creating Adaptive Policies a Guide for Policymaking in an Uncertain World. Los Angeles: SAGE, IISD/International Institute for Sustainable Development, International Development Research Centre; 2009.

- 23. Boston J, Bradstock A, Eng D. Public Policy: Why Ethics Matters. Canberra: Australian National University Press; 2010.

- 24. Przeworski A. Capitalism and Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1985.

- 25.Busenberg GJ. Learning in organizations and public policy. J Public Policy. 2001;21:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dewey J. The Public and its Problems. New York: Holt and Company; 1927.

- 27.Rondinelli DA. Government decentralization in comparative perspective: theory and practice in developing countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 1981;47:133–145. doi: 10.1177/002085238004700205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Institute for Sustainable Development. Designing Policies in a World of Uncertainty, Change and Surprise. Ottawa: Institute for Sustainable Development; 2006.

- 29. Sabel C. Learning by Monitoring. In: Smelser E, Swedberg R, eds. Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1995:135-165.

- 30.Dorf M, Sabel C. A constitution of democratic experimentalism. Columbia Law Rev. 1998;98:267–473. doi: 10.2307/1123411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noonan K, Sabel CE, Simon W. Legal accountability in the service-based welfare state: lessons from child welfare reform. Law and society inquiry. 2009;34:523–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4469.2009.01157.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kay A, Reid R. Sequences in health policy reform: reinforcement and reaction in universal health. Milan; 2013.

- 33. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). State of food insecurity in the world 2014: strengthening the enabling environment for food... security and nutrition. FAO; 2014.

- 34. MCAFPD. Department of Food and Public Distribution. http://dfpd.nic.in/?q=node/101. Published 2014.

- 35. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Special Focus: Inequality in Emerging Economies (EEs). http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/49170475.pdf. Published 2011.

- 36. Pal P, Ghosh J. Inequality in India: A survey of recent trends. Economic and Social Affairs Working http://www.chereum.umontreal.ca/activites_pdf/Session%201/Inequality%20in%20India%20(1).pdf. Accessed December 4, 2014. Published 2007.

- 37. Gwartney J. Economics: Private and Public Choice. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2014.

- 38.Carey G, Crammond B. A glossary of policy frameworks: the many forms of “universalism” and policy “targeting. ” J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014 doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hurley J, Vaithianathan R, Crossley TF, Cobb-Clark DA. Parallel private health insurance in Australia: A cautionary tale and lessons for Canada. IZA Discussion Paper; 2002. Report No. 515.

- 40.Spicker P. Understanding particularism. Crit Soc Policy. 1994;13:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson S, Hoggett P. Universalism, selectivism and particularism: towards a postmodern social policy. Crit Soc Policy. 1996;16:21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor-Gooby P. Postmodernism and social policy: a great leap backwards? J Soc Policy. 1994;23:385. [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy Achievement in Reading, Persuasive Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Government of Australia; 2013.

- 44. Peske HG, Haycock K. Teaching Inequality: How Poor and Minority Students Are Shortchanged on Teacher Quality: A Report and Recommendations by the Education Trust. Education Trust. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED494820. Accessed November 24, 2014. Published 2006.

- 45.Shin JC. Impacts of performance-based accountability on institutional performance in the US. Higher Education. 2010;60:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Australia, Department of Education of Education and Workplace Relations, Gonski DM. Review of Funding for Schooling Final Report. Canberra: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; 2012.

- 47. Fleischmann M. The Fleischmann report on the quality, cost, and financing of elementary and secondary education in New York State. New York: New York State Commission on the Quality, Cost, and Financing of Elementary and Secondary Education; 1973.

- 48. Education, who pays the bills? Time Magazine. February 07, 1972. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,905735,00.html.