Abstract

The authors of "Management matters: a leverage point for health systems strengthening in global health," raise a crucial issue. Because more effective management can contribute to better performing health systems, attempts to strengthen health systems require attention to management. As a guide toward management capacity building, the authors outline a comprehensive set of core management competencies needed for managing global health efforts. Although, I agree with the authors’ central premise about the important role of management in improving global health and concur that focusing on competencies can guide management capacity building, I think it is important to recognize that a set of relevant competencies is not the only way to conceptualize and organize efforts to teach, learn, practice, or conduct research on management. I argue the added utility of also viewing management as a set of functions or activities as an alternative paradigm and suggest that the greatest utility could lie in some hybrid that combines various ways of conceptualizing management for study, practice, and research.

Keywords: Management, Competencies, Functions and Activities, Developing/Strategizing, Designing, Leading

In their insightful editorial, Bradley et al1 observe that management has received inadequate attention as a critical element in the global quest for better performing health systems. They see effective management as essential to ensuring success in the application of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) “health systems strengthening framework,” with its 6 “building blocks” of successful health systems: service delivery, leadership and governance, healthcare financing, health workforce, medical products and technologies, and information and research.2

Following others,3,4 these authors define management as “the process of achieving predetermined objectives through human, financial, and technical resources.” The process can apply to almost any human activity, including the establishment and operation of health systems. They note that management occurs at various levels of systems including top management and policy levels, middle management, and operational front line levels, and that it is important at all levels.

Conceptually similar to others before them,5-7 Bradley et al1 advocate for a set of 8 core management competencies: (1) strategic thinking and problem solving, (2) human resource management, (3) financial management, (4) operations management, (5) performance management and accountability, (6) governance and leadership, (7) political analysis and dialogue, and (8) community and customer assessment and engagement.1 They propose a tri-part strategy incorporating education and training, practice, and research “to build the field of management as a key pillar of global health.”1 The proposed strategy features developing and offering curricula that emphasize the 8 competencies at undergraduate and graduate levels globally.

The competency approach to considering management is a constructive way to think about what effective managers for the world’s health systems should be good at doing, especially taking into account the observation that, “while the competencies apply across levels of management, the level of control and portion of time spent in each area will vary based on the structure and level of the hierarchy within the larger health system.”1 However, although management can certainly be conceptualized – and it can be taught, learned, practiced, and researched – using core management competencies as an organizing principle, this is not the only way. It may be useful to conceptualize management in other ways. In fact, the greatest utility could lie in some hybrid that combines various ways of conceptualizing management for study, practice, and research.

More Than One Way to Conceptualize Management

The management literature is replete with examples of conceptualizing management in terms of managers performing an interrelated set of functions or activities,8,9 or in terms of managers fulfilling a variety of interconnected roles.10 When taking either of these conceptual approaches, competencies can be thought of as variables that can assist or hinder managers in carrying out their managerial activities or in playing their managerial roles. To provide an alternative to conceptualizing management in terms of competencies, I provide a conceptualization of management as a set of functions or activities that managers must engage in if they are to manage effectively. This discussion draws upon some of my previous work.11 Space constraints prohibit elucidating the interrelated roles played by managers herein, although it is yet another way to conceptualize management.

Management as a Set of Functions or Activities

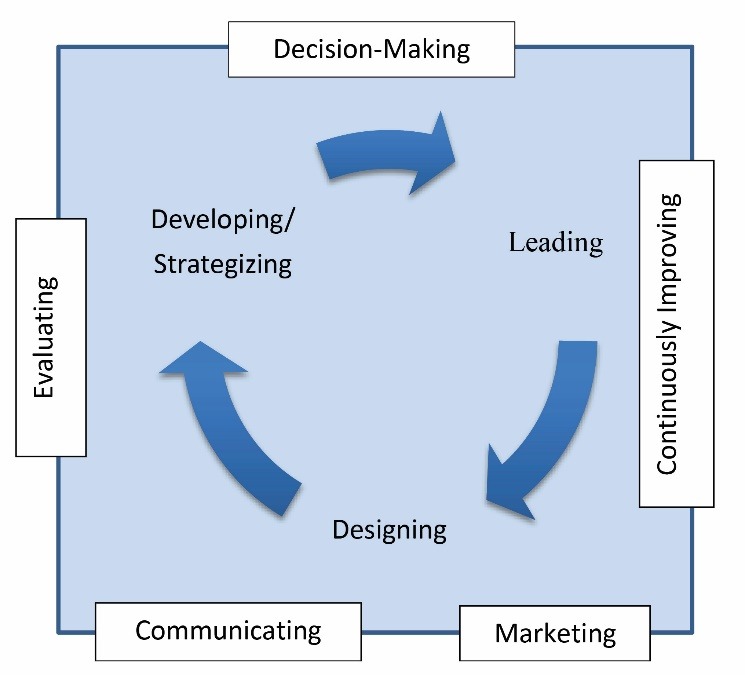

All successful managers in health systems, no matter what their organizational level, engage in three core activities: developing/strategizing, designing, and leading. This is the heart of what managers must do to succeed in their work. These core activities are facilitated and supported by other activities: decision-making, communicating, continually improving, marketing, and evaluating. These core and facilitative management functions or activities, as modeled in Figure 1, must be performed well if health systems, or components of them, are to be well-managed.

Figure 1.

Core and Facilitative Management Functions and Activities in Health Systems

In considering management in terms of functions or activities it is convenient to separate them so that each can be discussed independently; but management should not be viewed as a series of separate activities sequentially performed. In practice, managers perform these activities simultaneously, not sequentially, and as part of an interdependent mosaic of activities. The separation of management activities is necessary for purposes of discussion, but it is an artificial treatment of the reality of managing. It is also important to remember that managers at different levels of health systems will perform different sets or “mixes” of these activities. Each of the functions or activities modeled in Figure 1 is briefly described in the following sections, beginning with the 3 core activities.

Developing/Strategizing

Health systems, and components of them, come into existence because people develop or initiate them, and then strategize their futures on an ongoing basis. Development triggers strategizing, which is the establishment or revision of a specific mission and objectives and planning the means of achieving them. The mission and objectives become targets or goals which provide guidance in controlling operations and performance.

Although the relative degree of complexity may vary, managers at all levels and in all components of health systems engage in developing/strategizing as part of managing their domains of responsibility. This activity not only results in decisions about existence, revision, purpose, and direction of health systems or components of them, it also helps managers adapt to the challenges and opportunities presented by their dynamic external environments.12 Finally, effective developing/strategizing lays the foundation for the other core management activities: designing effective relationships among people and other resources and leading others to contribute to achieving the mission and objectives.

Designing

Designing means establishing and revising the intentional patterns of relationships among human and other resources within health systems and establishing and revising relationships with their external environments. This activity permits managers to establish an organizational structure or design. Creating these structures entails designating individual positions and aggregating or clustering these positions into work groups, departments, larger units of organizations, entire organizations, and eventually systems comprised of inter-connected organizations. Particularly vexing design challenges in health systems include achieving coordination among diverse participants and component parts and finding ways to minimize and resolve conflict between and among them.

Leading

Leading, as a core management activity, means influencing other participants in a manager’s domain of responsibility. This requires managers to instill in other participants a shared understanding of mission and objectives and to help them be motivated to contribute to their accomplishment. As leaders, managers focus on the various decisions and actions that affect the entire undertaking, including those intended to ensure survival and overall well-being. Leading in any setting is challenging, especially so in settings such as health systems where managers must seek to satisfy diverse constituencies with sometimes conflicting wishes or perspectives.

As illustrated in the center of Figure 1, the core functions or activities of managers are interrelated. Leading is not done in isolation from designing or developing/strategizing. How managers engage in one core management activity affects their performance in others.

In addition to these core activities, managers must also engage in a number of other facilitative activities, which are considered next, and which permit us to create a more complete model of what successful managers actually do. We begin with the ubiquitous decision-making.

Decision-Making

This activity permeates everything managers do. Managers make decisions when mission and objectives are established through developing/strategizing, or when alterations are made in an organization design. In fact, not only are designs subject to change, but all management is performed in a dynamic context that requires continual decision-making to modify such variables as mission and objectives as well as the means to accomplish them.

Although decision-making is fundamentally making a choice between 2 or more alternatives,13 making these choices is often extraordinarily complex in health systems. Managers face myriad decisions. Some are problem-solving decisions; others are opportunistic decisions. Problem-solving decisions are made in order to solve existing or anticipated problems. Opportunistic decisions are typically sporadic and arise with opportunities to reshape or advance accomplishment of mission and objectives. An example is identifying and finding a way to meet unmet health needs in a population. In making both problem-solving and opportunistic decisions, managers follow a defined decision-making process. This process begins with identifying a problem or opportunity requiring a decision and proceeds through developing and assessing relevant alternatives, choosing an alternative and then implementing and evaluating the decision.

Communicating

Just as decision-making permeates management, communicating is also ubiquitous in facilitating a manager’s performance of all other managerial activities. For example, managers who can effectively articulate and communicate their ideas and preferences have a distinct advantage in leading others. If other participants are to be involved in establishing and changing organization designs, communicating is vital, and if these designs are to be understood by those affected by them, details of the designs must be effectively communicated. Communicating is essential in developing strategies and in sharing the strategies with stakeholders, whether internal or external to the health system or component.

Continuously Improving

To successfully manage health systems, or components of them, managers must commit to continuously improving operations and performance, and know how to accomplish it. This requires them to continuously search for better ways to accomplish the mission and associated objectives. This activity is characterized by the use of robust process improvement techniques and by taking a systematic approach to the task. Among the numerous improvement approaches, Six Sigma, Lean, Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, and hybrids of these approaches play prominent roles.14 According to Chassin and Loeb,15 these and other systematic approaches require:

reliably measuring the magnitude of problems

identifying the root causes of problems

finding solutions for the most important causes

proving the effectiveness of those solutions

sustaining improvements over time

Given that various health services – whether preventive, acute, or chronic – are the raison d’etre of health systems, the commitment to continuously improving applies especially to the quality of those services. However, in the face of scarcity and alternative uses of resources the commitment extends to all operations and performance within health systems, no matter where they are located.

Marketing

Marketing is a facilitative management activity through which the needs of people can be identified and perhaps met.16 In global health systems, marketing can serve both commercial and social purposes. Marketing, whether commercial or social, can initiate voluntary exchanges that further the mission and objectives of health systems or their components. In addition to patients or clients, as individuals and populations, successful health systems engage in voluntary exchanges with physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers; with public and private insurers and health plans; with governments and their agencies; with potential employees; with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other non-profit organizations; and perhaps with donors and volunteers. All of these exchanges are supported and facilitated through marketing. Of course, managers in health systems must also enter into certain involuntary exchanges, especially in complying with laws and regulations or rules established by governmental agencies. Such involuntary exchanges, while important, are less ubiquitous than the voluntary exchanges the marketing function supports.

Evaluating

When managers engage in evaluating activities as shown in Figure 1, they collect and analyze information about some aspect of their domains of responsibility. At its basic level, evaluation, as a management activity, is “the application of systematic methods to address questions about … operations and results.”17 In the context of health systems and components of them, managers engage in this activity for a number of reasons, including (1) improving overall operations and performance, (2) demonstrating accountability to stakeholders and justifying use of resources, (3) demonstrating effectiveness in terms of accomplishing a mission and objectives, and (4) demonstrating effectiveness of specific health interventions.

Conclusion

Management in any setting is a complicated process, as much so in health systems, no matter where they are located, as in any imaginable setting. Given the importance of the mission and objectives being pursued and the scarcity and alternate uses of available, often limited, resources for achieving them, Bradley et al1 are absolutely correct in their view that management is a critical element in the global quest for better performing health systems and that it has received inadequate attention. Those who seek to rectify this inadequacy, whether through teaching, learning, practicing, or researching management, will benefit from these authors’ views on the relevant competencies needed by managers. However, efforts to improve health system management can be further enriched by considerations of the critical core and facilitative activities that managers must engage in if they are to manage well. It is likely that better managed health systems – and thus better performing health systems – will result from careful attention to developing requisite competencies of managers and to being certain they understand and can effectively engage in the core and facilitative functions and activities that comprise management.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contribution

BBL is the single author of the manuscript.

Citation: Longest BB. Management certainly matters, and there are multiple ways to conceptualize the process: Comment on "Management matters: a leverage point for health systems strengthening in global health." Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(11):777–780. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015

References

- 1.Bradley EH, Taylor LA, Cuellar CJ. Management matters: a leverage point for health systems strengthening in global health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(7):411–415. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO Health Systems Framework. http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/health_systems_framework/en/. Accessed June 2, 2015.

- 3. Banaszak-Holl J, Nembhard, Ingrid ME, Taylor L, Bradley EH. Leadership and management: a framework for action. In: Burns L, Bradley E, Weiner B, eds. Shortell and Kaluzny’s Healthcare Management: Organization Design and Behavior. Clifton Park, NJ: Cengage Learning; 2011.

- 4. Longest BB, Darr K. Managing Health Services Organizations and Systems. 6th ed. Baltimore: Health Professions Press; 2014.

- 5. National Center for Healthcare Leadership (NCHL). NCHL Healthcare Leadership Competency Model, version 2.0, 5–7. Chicago: NCHL; 2012.

- 6.Longest BB. Managerial competence at senior levels of integrated delivery systems. J Healthc Manag. 1998;43:115–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz RL. Skills of an effective administrator. Harv Bus Rev. 1974;52:90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daft RL. Management. 12th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western College Publishing; 2015.

- 9. Longest BB. Health Program Management: From Development Through Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2015.

- 10.Mintzberg H. The Manager’s Job: Folklore and Fact HBR Classic. Harv Bus Rev. 1990;68:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longest BB. Medical practice management in a nutshell. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(4):227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ginter PM, Duncan WJ, Swayne LE. Strategic Management of Health Care Organizations. 7th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013.

- 13. DuBrin AJ. Essentials of Management. 9th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning; 2012.

- 14. Lighter DE. Basics of Health Care Performance Improvement: A Lean Six Sigma Approach. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013.

- 15.Chassin MR, Loeb JM. The Ongoing Quality Improvement Journey: Next Stop, High Reliability. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):559–568. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kotler P, Keller KL. Framework for Marketing Management. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2015.

- 17. Wholey JS, Hatry HP, Newcomer KE. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.