Abstract

The purpose of this study was to report predictors and prevalence of home and workplace smoking bans in 5 European countries.

We conducted a population-based telephone survey of 4977 women, ascertaining factors associated with smoking bans. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were derived using unconditional logistic regression.

A complete home smoking ban was reported by 59.5% of French, 63.5% of Irish, 61.3% of Italian, 74.4% of Czech, and 87.0% of Swedish women. Home smoking bans were associated with younger age and being bothered by secondhand smoke, and among smokers, inversely associated with greater tobacco dependence. Among nonsmokers, bans were also related to believing smoking is harmful (OR=1.20, CI: 1.11, 1.30) and having parents who smoke (OR=0.62, CI: 0.52, 0.73). Workplace bans were reported by 92.6% of French, 96.5% of Irish, 77.9% of Italian, 79.1% of Czech, and 88.1% of Swedish women. Workplace smoking bans were reported less often among those in technical positions (OR=0.64, CI: 0.50, 0.82) and among skilled workers (OR=0.53, CI: 0.32, 0.88) than among professional workers.

Workplace smoking bans are in place for most workers in these countries. Having a home smoking ban was based on smoking behavior, demographics, beliefs, and personal preference.

Keywords: Passive smoking, Social class, Tobacco, Women, Family, Tobacco dependence

Introduction

The health consequences of secondhand smoke are well documented. Secondhand smoke is particularly detrimental to respiratory and cardiovascular health and is also a cause of lung cancer and asthma and impacts immune function and other diseases [1, 2]. Based on these health risks, legislation banning tobacco smoking in public places has been passed in several European countries. There is increasing evidence that these smoking bans decrease exposure to secondhand smoke and its subsequent health effects, including respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular disease [3].

In addition to lessening exposure to secondhand smoke, smoking bans may have broader public health impacts. Although the evidence has been conflicting, smoking bans may discourage youth from initiating smoking or may encourage smokers to reduce cigarette consumption, quit smoking, may assist quit attempts and prevent relapse [4].

The proportion of persons who report their workplace being smoke-free has increased over time [5]. US-based studies report that individuals exposed to secondhand smoke at work are more likely to be young, to have fewer years of education, to be smokers themselves, and to be employed as manual laborers or to work in service positions [6, 7]. It is not known if these variations in secondhand smoke exposure are present in European countries that have enacted broad legislation to limit smoke exposure in workplaces.

In the general population and also among smokers in particular, there is evidence in some countries of an increase over time in the proportion of persons living in smoke-free homes [5]. Although this trend is driven in part by a drop in the number of smokers, it is likely that social norms which discourage smoking have also played a role. Home smoking bans appear to be more common in households where fewer smokers are living, among younger persons, those of higher socioeconomic status (SES), and in homes where there are children present [7–9]. Smokers who work in smoke-free workplaces may be more likely to make their home smoke-free [10].

The majority of studies which have examined the prevalence and predictors of smoking bans have been in non-European countries. The purpose of this paper was to describe the prevalence and predictors of home and workplace smoking bans in five European countries at different stages of implementing comprehensive smoke-free legislation.

Methods

A population-based telephone survey was conducted in June and July 2008 among 5000 women ages 18 and older in France, Italy, Ireland, Sweden, and the Czech Republic (1000 per country). These countries were selected because they are at differing stages of enacting tobacco control legislation. Smoking was banned in bars and restaurants in Ireland on 29 March 2004; in Italy on 10 January 2005; in Sweden on 1 June 2005; and in France on 1 January 2008, while the Czech Republic currently allows smoking in these venues. These countries have varying policies on other tobacco control measures, such as increasing taxes on tobacco products; taking steps to limit sales to minors or to combat smuggling; limiting tobacco advertising or sponsorship; and providing support for those who wish to quit.

A stratified sampling approach was undertaken in order to enroll a sample that would be nationally representative with regards to age, smoking status, and city size. Telephone numbers were taken from country-wide phone lists. Of the women reached who were eligible for participation, response rates were 64.8% in France, 41.4% in Italy, 59.0% in Sweden, 54.6% in Ireland, and 30.6% in the Czech Republic. Of the 5000 participants, 23 (<1%) were excluded from the present analysis due to missing information on age, education, or whether they had a home smoking ban. The final sample included 4977 participants.

In the survey, trained interviewers asked participants questions on their demographics, smoking behaviors, and on their attitudes and beliefs about tobacco, lung cancer, and smoke-free policies in public places. All interviews were conducted in the language native to each country. To improve robustness, smokers were oversampled in all countries to reach 28% of subjects, and all results were weighted to account for the oversampling. Participants were asked if anyone was allowed to smoke inside their home and, among women employed outside the home, whether smoking was allowed in their immediate work area. Having a home smoking ban was defined as the preference to not allow smoking inside the home, which was assumed to be based on the woman’s choice or the agreement of family members, rather than enforced by an outside entity such as due to a local ordinance. It should be noted that only persons with a complete indoor home smoking ban, with no persons allowed to smoke, are included in this group, although there were also subjects who indicated certain, but not all, persons were allowed to smoke in their home. In addition, it is possible that some subjects allowed smoking but took steps to lower ambient smoke in their home, such as by opening windows.

We report factors associated with having home and workplace smoking bans. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 (Cary, USA). For the multivariable model of factors related to home smoking bans, variables considered for inclusion in the model were those previously associated with the use of such bans, including age, marital status, SES, urban/rural residence, smoking behaviors, degree of tobacco dependence, and beliefs about the harm of tobacco smoke [8, 9, 11–14]. Tobacco dependence was measured using time to first cigarette [15] and the number of cigarettes per day. After it was determined that number of cigarettes per day added little to analyses, it was left out of the final model. Tobacco dependence questions were asked of both daily and occasional smokers. Because of variation across countries in the number of years required to achieve educational degrees, and in differences in the equivalence of degrees, we measured educational attainment as the age at which women finished their education. Several health behavior theories, such as the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Reasoned Action, state that the adoption of a healthy lifestyle change is dependant on one’s perception of risk [16, 17]. Thus we included perceived risk of lung cancer in the model. Because women’s perceptions of health risks are influenced by having a family history of disease [18], we included family history of lung cancer in the model. As familial smoking has been associated with young women’s smoking behaviors and the decision to have a smoke-free home [19, 20], we also included parental smoking in the model. The questions regarding beliefs about the harms of tobacco were scored on a four-point Likert scale. To improve robustness of the measure, Likert items were analyzed as continuous variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were derived using unconditional logistic regression. For the analysis of home smoking bans, we conducted separate analyses for smokers and nonsmokers.

For the model of predictors of workplace smoking bans, factors considered were age, marital status, smoking status, country, educational attainment and job classification, which have been seen in other studies as being associated with workplace secondhand smoke exposure [5, 7]. Job classification was measured using the International Standard Classification of Occupation, 1988 version (ISCO-88) [21]. As workers who are bothered by secondhand smoke may choose to leave a job or request a transfer to a smoke-free work area, we also included in the model if participants were bothered by secondhand smoke. Due to the small number of participants in some countries who were exposed to secondhand smoke at work, models were underpowered to examine results by each country separately. We therefore provided a summary model for all 5 European countries.

Results

Across the countries, 14–18% of participants were current daily smokers, while an additional 4% smoked some days or occasionally (Table 1); Ireland and the Czech Republic had a larger proportion of women who smoked occasionally. Among smokers, Ireland had a larger proportion with high levels of tobacco dependence (26% having a cigarette within 5 minutes of waking), while the Czech Republic had a large proportion of women with low tobacco dependence (58% having their first cigarette after 60 minutes). A quarter of women had worked in professional positions, while 40% were skilled workers and 15% homemakers. Over a third of all participants resided in urban areas.

Table 1.

Description of the population#

| France (N=993) |

Ireland (N=994) |

Italy (N=995) |

Czech Republic (N=998) |

Sweden (N=997) |

All (N=4977) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %a | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–24 | 8.2 | 11.4 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.5 |

| 25–34 | 17.2 | 22.0 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 15.2 | 18.8 |

| 35–44 | 18.6 | 19.9 | 18.9 | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.3 |

| 45–54 | 18.2 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 17.9 | 18.7 | 17.7 |

| + 55 | 37.8 | 29.8 | 38.3 | 37.7 | 39.7 | 36.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 46.4 | 36.9 | 51.9 | 38.0 | 31.8 | 41.0 |

| Divorced/ Separated | 20.5 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 16.9 | 17.6 | 14.2 |

| Widowed | 3.4 | 18.2 | 11.6 | 22.1 | 8.8 | 12.8 |

| Single, never married | 11.2 | 33.0 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 16.6 | 21.6 |

| Living with a partner | 18.6 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 25.2 | 10.4 |

| Age at completing education | ||||||

| <=19 | 38.3 | 63.8 | 59.3 | 55.0 | 49.3 | 53.1 |

| 20–25 | 49.5 | 28.4 | 29.8 | 35.0 | 26.7 | 33.9 |

| 26+ | 12.2 | 7.8 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 24.1 | 13.0 |

| Job category (ISCO-88)¶ | ||||||

| Professionals (ISCO 1, 2) | 15.5 | 28.8 | 22.4 | 42.6 | 19.9 | 25.9 |

| Technical positions (ISCO 3) | 3.1 | 8.0 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 7.4 | 4.5 |

| Skilled workers (ISCO 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10) | 34.3 | 27.3 | 45.3 | 35.6 | 59.4 | 40.4 |

| Unskilled workers (ISCO 9) | 30.7 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 9.4 |

| Homemaker | 12.5 | 28.4 | 24.2 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 14.5 |

| Full-time student | 4.0 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 5.3 |

| City size | ||||||

| <5000 persons | 28.2 | 28.1 | 13.1 | 29.1 | 36.4 | 27.0 |

| 5000 – 100000 | 31.6 | 35.7 | 33.8 | 37.4 | 32.9 | 34.3 |

| 100000+ | 40.2 | 36.2 | 53.1 | 33.5 | 30.7 | 38.7 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Smokes every day or almost | 17.7 | 16.8 | 15.3 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 15.8 |

| Smokes some days or occasionally | 2.8 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| Former smoker | 17.3 | 25.7 | 22.2 | 15.1 | 27.2 | 21.5 |

| Never smoker | 62.2 | 50.8 | 60.2 | 65.7 | 54.3 | 58.6 |

| One or both parents smoked | ||||||

| Yes | 58.6 | 63.8 | 56.9 | 49.1 | 56.2 | 56.9 |

| Family history of lung cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 24.1 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 22.8 | 16.3 | 19.7 |

| Perceived risk of lung cancer | ||||||

| Low | 40.3 | 51.1 | 40.1 | 44.6 | 59.9 | 47.2 |

| Medium | 36.4 | 20.0 | 28.7 | 23.8 | 20.8 | 26.0 |

| High | 15.2 | 10.5 | 18.2 | 5.2 | 13.7 | 12.6 |

| Don't know | 8.0 | 18.4 | 13.1 | 26.4 | 5.6 | 14.2 |

| Time to first cigarette in the morning+ | ||||||

| <5 minutes | 19.2 | 26.4 | 14.7 | 13.9 | 22.9 | 19.8 |

| 6–30 minutes | 30.3 | 19.5 | 28.5 | 19.2 | 33.8 | 25.9 |

| 31–60 minutes | 6.3 | 9.0 | 11.7 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 9.3 |

| Over 60 minutes | 44.2 | 45.1 | 45.1 | 57.7 | 32.6 | 45.0 |

| Cigarettes per day+ | ||||||

| 1–10 | 55.7 | 48.3 | 55.8 | 64.9 | 63.7 | 57.2 |

| 11–20 | 37.9 | 43.1 | 38.5 | 31.0 | 33.6 | 37.1 |

| 21+ | 6.3 | 8.7 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 5.6 |

All percents are weighted.

Occupation of current job; women not currently working were asked to identify their most recent job.

Current smokers only.

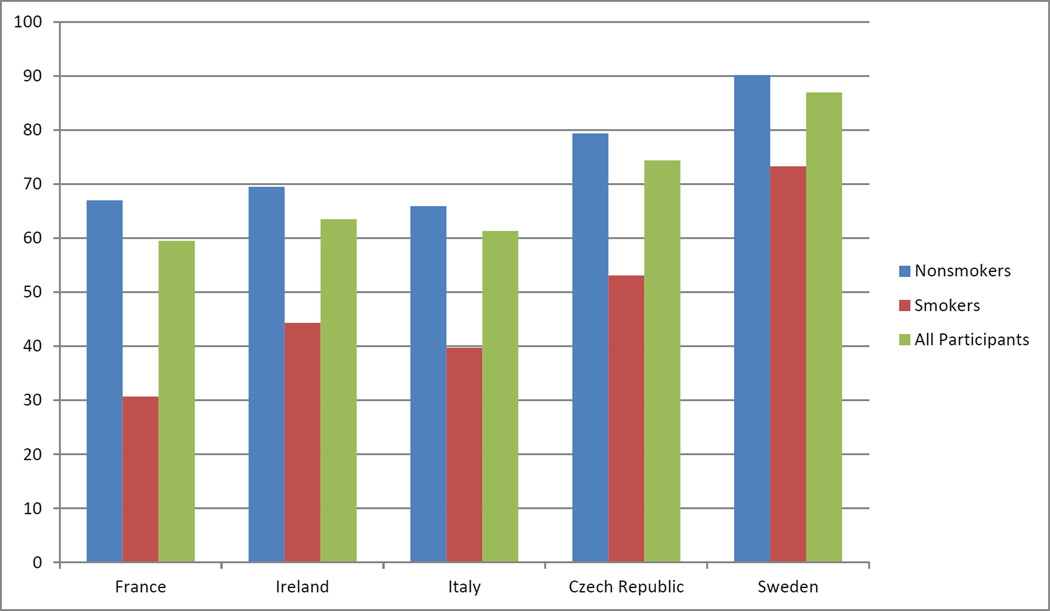

Considering all countries together, the prevalence of a smoking ban at home varied between smokers and nonsmokers (fig. 1). It was reported among 75% of the nonsmokers and 50% among smokers. Differences across countries were more apparent among smokers than among nonsmokers. Sweden had the largest proportion of participants who reported having a smokefree home, and this was the case both among smokers and nonsmokers (Table 2). Among nonsmoking participants, Italy had the lowest percent with a home smoking restriction (66%), while among smokers, France had the lowest percent of having a smoking restriction at home (31%). Among women employed outside of the home, Ireland had the lowest proportion of participants reporting that smoking allowed in their immediate working area, while Italy had the highest.

Figure 1.

Proportion of women who reported having a smoking ban in their home

Table 2.

Percent of respondents with smoking bans at home and at work#

| France (n=993) |

Ireland (n=994) |

Italy (n=995) |

Czech Republic (n=998) |

Sweden (n=997) |

All (n=4977) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %a | % | % | % | % | % | p | |

| Is anyone allowed to smoke cigarettes inside your home? | |||||||

| All participants (n=4977) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No, no one | 59.5 | 63.5 | 61.3 | 74.4 | 87.0 | 69.2 | |

| Yes, but only certain persons are allowed | 12.7 | 14.9 | 13.8 | 15.1 | 7.1 | 12.7 | |

| Yes, anyone can smoke | 27.8 | 21.6 | 24.9 | 10.5 | 5.9 | 18.1 | |

| Nonsmokers (n=3563) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No, no one | 67.0 | 69.5 | 65.9 | 79.4 | 90.2 | 74.5 | |

| Yes, but only certain persons are allowed | 12.6 | 15.2 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 6.4 | 12.7 | |

| Yes, anyone can smoke | 20.4 | 15.3 | 19.9 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 12.9 | |

| Smokers (n=1414) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No, no one | 30.7 | 44.3 | 39.7 | 53.1 | 73.3 | 47.8 | |

| Yes, but only certain persons are allowed | 13.1 | 13.6 | 12.1 | 15.4 | 10.2 | 12.9 | |

| Yes, anyone can smoke | 56.1 | 42.2 | 48.3 | 31.5 | 16.5 | 39.3 | |

| Proportion of participants who reported that smoking is allowed in their immediate work area (among employed women who had a regular work area) | |||||||

| All participants | 7.4 | 3.5 | 22.1 | 20.9 | 11.9 | 13.4 | <0.0001 |

| Nonsmokers | 6.4 | 2.8 | 21.9 | 22.4 | 12.2 | 13.6 | <0.0001 |

| Smokers | 10.8 | 5.5 | 23.1 | 15.0 | 10.9 | 12.7 | 0.0002 |

All percents are weighted. P-values by chi-square.

When examining the prevalence of smoking bans across demographic variables, it could be seen that women aged 25–44 were among the most likely to have home smoking bans (Table 3). Bans were generally more common among married women and women living with a partner. In the Czech Republic, home smoking bans were seen more often among those with greater years of education. There was heterogeneity between countries with regards to job category and home smoking bans. In every country, smokers were less likely than nonsmokers to have home smoking bans. Smoking bans were more common among those who perceived the risk of lung cancer to be low. Home smoking bans were more common among women who believe smoking is harmful and that exposure to smoke is dangerous to pregnant women and their children. Having home smoking bans was strongly associated with being bothered by secondhand smoke.

Table 3.

Percent of subjects who reported having a smoking ban at home#

| France (N=993) |

Ireland (N=994) |

Italy (N=995) |

Czech Republic (N=998) |

Sweden (N=997) |

All (N=4977) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | |

| Age in years | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0003 | 0.5 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 18–24 | 55.0 | 61.1 | 55.3 | 73.1 | 92.0 | 67.4 | ||||||

| 25–34 | 64.3 | 69.3 | 67.7 | 79.1 | 90.2 | 73.5 | ||||||

| 35–44 | 60.7 | 67.0 | 72.3 | 74.7 | 94.3 | 73.6 | ||||||

| 45–54 | 59.0 | 62.5 | 58.3 | 73.9 | 89.4 | 69.0 | ||||||

| + 55 | 58.1 | 58.4 | 55.0 | 72.2 | 80.3 | 65.2 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.02 | 0.0008 | 0.02 | 0.4 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married | 63.6 | 71.1 | 65.9 | 76.2 | 91.1 | 72.2 | ||||||

| Divorced/Separated | 57.2 | 61.6 | 50.5 | 76.2 | 82.5 | 67.8 | ||||||

| Widowed | 74.2 | 63.3 | 56.4 | 72.7 | 79.0 | 68.0 | ||||||

| Single, never married | 48.4 | 55.1 | 57.4 | 70.0 | 80.4 | 61.9 | ||||||

| Living with a partner | 57.5 | 60.9 | 61.3 | 82.8 | 91.8 | 75.5 | ||||||

| Age at completion of education | 0.7 | 0.0003 | 0.4 | 0.005 | 0.4 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| <=19 years | 58.3 | 59.1 | 61.5 | 71.6 | 85.8 | 67.1 | ||||||

| 20–25 years | 60.8 | 72.9 | 59.1 | 75.1 | 89.4 | 70.0 | ||||||

| 26+ years | 58.3 | 66.0 | 66.1 | 87.1 | 86.9 | 75.6 | ||||||

| Job category (ISCO-88) | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Professionals (ISCO 1, 2) | 66.4 | 68.7 | 58.7 | 74.6 | 85.5 | 71.2 | ||||||

| Technical positions (ISCO 3) | 44.0 | 68.9 | 63.3 | 73.3 | 89.5 | 72.6 | ||||||

| Skilled workers (ISCO 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10) | 55.2 | 56.8 | 63.1 | 75.2 | 86.8 | 70.0 | ||||||

| Unskilled workers (ISCO 9) | 62.1 | 70.7 | 76.7 | 58.7 | 82.2 | 65.2 | ||||||

| Homemaker | 60.2 | 62.6 | 62.2 | 71.8 | 100.0 | 63.9 | ||||||

| Full-time student | 60.1 | 61.4 | 46.7 | 82.2 | 90.3 | 71.3 | ||||||

| City size | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| <5000 | 60.5 | 61.2 | 66.1 | 75.5 | 89.3 | 72.2 | ||||||

| 5000 – 100000 | 60.2 | 65.1 | 63.4 | 75.9 | 88.6 | 70.8 | ||||||

| 100000+ | 58.4 | 63.8 | 58.8 | 71.7 | 82.6 | 65.7 | ||||||

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Smokes every day or almost | 28.5 | 32.7 | 35.5 | 47.2 | 70.4 | 42.1 | ||||||

| Smokes some days | 44.8 | 73.0 | 67.2 | 69.9 | 84.8 | 69.9 | ||||||

| Former smoker | 57.2 | 61.7 | 63.3 | 66.4 | 89.5 | 69.0 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 69.7 | 73.4 | 66.9 | 82.4 | 90.5 | 76.5 | ||||||

| Time to first cigarette in the morning¶ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| <5 minutes | 18.8 | 33.4 | 16.7 | 31.8 | 73.6 | 36.8 | ||||||

| 6–30 minutes | 20.3 | 17.0 | 38.1 | 48.3 | 73.6 | 40.2 | ||||||

| 31–60 minutes | 21.4 | 44.9 | 34.4 | 41.6 | 79.4 | 46.1 | ||||||

| Over 60 minutes | 44.4 | 62.3 | 49.5 | 61.7 | 70.7 | 57.4 | ||||||

| Cigarettes per day+ | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.9 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 1–10 | 36.8 | 60.1 | 49.8 | 63.0 | 78.3 | 58.2 | ||||||

| 11–20 | 26.8 | 31.7 | 29.2 | 34.5 | 68.2 | 36.9 | ||||||

| 21+ | 0.0 | 18.9 | 11.2 | 30.4 | 17.1 | 14.6 | ||||||

| One or both parents smoked | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 66.2 | 74.5 | 69.0 | 78.9 | 89.0 | 75.8 | ||||||

| Yes | 54.8 | 57.3 | 55.5 | 69.7 | 85.5 | 64.1 | ||||||

| Family history of lung cancer | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | ||||||

| No | 55.0 | 62.3 | 63.5 | 77.3 | 84.3 | 67.8 | ||||||

| Yes | 61.0 | 63.8 | 60.8 | 73.5 | 87.6 | 69.5 | ||||||

| Perceived risk of lung cancer | 0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.007 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Low | 67.0 | 69.9 | 67.0 | 77.9 | 89.8 | 75.5 | ||||||

| Medium | 56.8 | 56.5 | 55.7 | 73.1 | 84.6 | 64.0 | ||||||

| High | 50.3 | 50.2 | 59.6 | 55.9 | 79.6 | 59.9 | ||||||

| Don't know | 56.7 | 60.5 | 59.9 | 74.8 | 84.1 | 67.0 | ||||||

| The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated. | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 63.3 | 68.1 | 64.3 | 76.9 | 88.0 | 72.5 | ||||||

| Agree or strongly agree | 49.9 | 44.6 | 50.5 | 60.2 | 82.4 | 56.8 | ||||||

| Exposure to secondhand smoke is dangerous to a pregnant woman and her child. | 0.05 | 0.0004 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 36.6 | 37.5 | 22.1 | 45.2 | 70.3 | 42.8 | ||||||

| Agree or strongly agree | 60.1 | 65.4 | 62.0 | 75.0 | 87.8 | 70.1 | ||||||

| Are you bothered by secondhand smoke? | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 42.9 | 42.9 | 34.3 | 50.0 | 77.0 | 50.1 | ||||||

| Yes | 68.2 | 73.8 | 69.4 | 82.1 | 91.6 | 77.0 | ||||||

All percents are weighted. Smoking bans at home were defined as having a complete ban, with no persons allowed to smoke. P-values by chi-square or ANOVA.

Asked of current smokers only (n=1414).

In four of the five countries, workplace smoking bans were more common among women who finished their education after the age of 20 (Table 4). While there was no difference according to job category in France, Ireland, or Sweden, bans were more common among professional women in Italy and the Czech Republic.

Table 4.

Percent of subjects who reported having a smoking ban at work#

| France (n=833) |

Ireland (n=676) |

Italy (n=710) |

Czech Republic (n=862) |

Sweden (n=915) |

All (n=3996) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | |

| Age in years | 0.9 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 18–24 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 87.2 | 79.5 | 83.2 | 91.5 | ||||||

| 25–34 | 91.3 | 97.9 | 86.7 | 92.3 | 95.5 | 92.8 | ||||||

| 35–44 | 93.6 | 98.3 | 89.9 | 90.1 | 94.8 | 93.4 | ||||||

| 45–54 | 92.7 | 96.0 | 93.0 | 80.8 | 92.5 | 90.6 | ||||||

| + 55 | 92.3 | 87.3 | 53.3 | 65.9 | 80.7 | 74.5 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.0001 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married | 94.5 | 96.8 | 79.4 | 83.6 | 91.2 | 88.5 | ||||||

| Divorced/Separated | 91.4 | 95.1 | 80.7 | 81.6 | 85.5 | 86.3 | ||||||

| Widowed | 83.8 | 85.4 | 61.4 | 62.9 | 74.4 | 68.5 | ||||||

| Single, never married | 92.7 | 97.8 | 78.7 | 86.0 | 91.2 | 89.3 | ||||||

| Living with a partner | 90.2 | 100.0 | 78.9 | 100.0 | 89.3 | 89.9 | ||||||

| Age at completion of education | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.007 | 0.005 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| <=19 years | 91.6 | 94.7 | 73.9 | 75.0 | 82.2 | 82.5 | ||||||

| 20–25 years | 93.6 | 98.3 | 79.7 | 84.6 | 94.8 | 90.4 | ||||||

| 26+ years | 91.2 | 100.0 | 88.7 | 84.6 | 92.8 | 91.3 | ||||||

| Job category (ISCO-88)b | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Professionals (ISCO 1, 2) | 92.3 | 97.3 | 84.5 | 84.6 | 91.3 | 89.4 | ||||||

| Technical positions (ISCO 3) | 96.6 | 98.6 | 74.2 | 67.3 | 83.4 | 88.7 | ||||||

| Skilled workers (ISCO 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10) | 92.3 | 94.9 | 75.0 | 73.4 | 88.2 | 84.2 | ||||||

| Unskilled workers (ISCO 9) | 92.7 | 96.0 | 72.2 | 77.2 | 81.3 | 88.3 | ||||||

| City size | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.001 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.007 | ||||||

| <5000 | 91.2 | 97.9 | 88.9 | 80.6 | 88.8 | 88.9 | ||||||

| 5000 – 100000 | 92.7 | 95.5 | 81.9 | 79.7 | 87.7 | 87.2 | ||||||

| 100000+ | 93.5 | 96.5 | 73.0 | 77.1 | 87.6 | 84.6 | ||||||

| Smoking status | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.5 | <0.0001 | 0.3 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| Smokes every day or almost | 88.2 | 94.4 | 77.7 | 83.6 | 88.4 | 86.5 | ||||||

| Smokes some days | 95.9 | 94.6 | 71.3 | 90.0 | 92.4 | 90.6 | ||||||

| Former smoker | 89.9 | 96.5 | 74.1 | 61.0 | 84.9 | 82.0 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 94.5 | 97.5 | 79.7 | 81.7 | 89.3 | 88.0 | ||||||

| Are you bothered by secondhand smoke? | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.7 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.2 | ||||||

| No | 92.1 | 94.2 | 78.8 | 74.7 | 84.5 | 85.5 | ||||||

| Yes | 93.2 | 97.7 | 77.5 | 80.5 | 89.5 | 87.1 | ||||||

All percents are weighted. P-values by chi-square. The presence of work smoking bans was asked only of women (n=3996) who worked outside the home, had a regular work area, and were not full-time students.

In multivariate analyses, there were differences across countries in factors associated with smokers having home smoking bans (Table 5). Married women were more likely to have home bans than other women. There was heterogeneity by country, but younger smokers were in general more likely to have smoking bans than older smokers. A smoking ban in the workplace had little impact on the likelihood of having a home smoking ban. There was no association between smoking bans and SES, as measured by age at leaving education; there was similarly no association when we used the ISCO job classification to measure SES (data not shown). As in the unadjusted data, Swedish smokers were the most likely to have home bans.

Table 5.

Odds (95% confidence intervals) of having a smoking ban at home among smokers#

| France (n=327) |

Ireland (N=278) |

Italy (n=279) |

Czech Republic (n=299) |

Sweden (n=231) |

All countries (n=1414) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–24 | 1.98 (0.36, 10.8) | 9.21 (1.84, 46.2) | 3.75 (0.54, 26.3) | 7.95 (1.26, 50.2) | 6.07 (0.78, 47.3) | 3.57 (1.85, 6.91) |

| 25–34 | 5.40 (1.19, 24.5) | 5.30 (1.21, 23.3) | 4.41 (0.99, 19.5) | 6.25 (1.54, 25.3) | 2.02 (0.53, 7.76) | 3.16 (1.82, 5.46) |

| 35–44 | 5.19 (1.22, 22.1) | 1.07 (0.29, 4.03) | 2.47 (0.66, 9.23) | 3.04 (0.92, 9.98) | 2.88 (0.86, 9.59) | 2.25 (1.35, 3.73) |

| 45–54 | 2.31 (0.50, 10.7) | 0.86 (0.23, 3.21) | 0.87 (0.22, 3.45) | 1.34 (0.43, 4.16) | 3.20 (0.97, 10.5) | 1.39 (0.84, 2.28) |

| + 55 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Living with partner | 0.58 (0.22, 1.52) | 0.17 (0.02, 1.21) | 0.40 (0.05, 3.19) | 0.05 (0.00, 0.69) | 0.55 (0.16, 1.86) | 0.61 (0.35, 1.06) |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.39 (0.12, 1.28) | 1.06 (0.32, 3.56) | 0.87 (0.26, 2.92) | 1.05 (0.38, 2.90) | 0.58 (0.18, 1.91) | 0.81 (0.52, 1.28) |

| Never married | 0.28 (0.09, 0.87) | 0.23 (0.07, 0.69) | 0.48 (0.15, 1.53) | 0.32 (0.10, 1.05) | 0.30 (0.08, 1.07) | 0.42 (0.27, 0.65) |

| Widowed | 0.47 (0.03, 8.46) | 0.71 (0.15, 3.35) | 0.67 (0.09, 5.14) | 0.65 (0.17, 2.57) | 2.76 (0.20, 38.4) | 0.85 (0.42, 1.70) |

| Age at completion of education | ||||||

| <=19 | 1.39 (0.59, 3.26) | 1.03 (0.38, 2.78) | 0.60 (0.24, 1.47) | 1.05 (0.46, 2.42) | 1.79 (0.60, 5.35) | 1.12 (0.78, 1.59) |

| 20–25 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 26+ | 0.94 (0.29, 3.04) | 0.22 (0.03, 1.45) | 0.80 (0.23, 2.79) | 3.51 (0.80, 15.4) | 0.51 (0.15, 1.73) | 0.85 (0.50, 1.43) |

| City size | ||||||

| <5000 persons | 0.67 (0.26, 1.74) | 0.73 (0.28, 1.90) | 3.13 (0.98, 10.0) | 1.83 (0.71, 4.75) | 1.85 (0.68, 5.06) | 1.43 (0.98, 2.11) |

| 5000 – 100000 | 1.00 (0.41, 2.42) | 1.02 (0.45, 2.34) | 2.13 (0.88, 5.17) | 1.81 (0.75, 4.35) | 1.26 (0.43, 3.64) | 1.45 (1.02, 2.07) |

| 100000+ | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Smokes every day | 0.66 (0.23, 1.93) | 0.30 (0.12, 0.76) | 0.29 (0.08, 1.08) | 0.34 (0.13, 0.89) | 0.32 (0.09, 1.17) | 0.41 (0.27, 0.63) |

| Smokes some days | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| One or both parents smoked | ||||||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.44, 2.29) | 0.72 (0.33, 1.56) | 0.31 (0.14, 0.69) | 0.74 (0.33, 1.65) | 0.65 (0.24, 1.80) | 0.63 (0.46, 0.88) |

| Family history of lung cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 0.75 (0.32, 1.79) | 1.25 (0.50, 3.12) | 0.65 (0.23, 1.82) | 0.41 (0.15, 1.10) | 0.49 (0.16, 1.48) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.08) |

| Perceived risk of lung cancer | ||||||

| Low | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Medium | 1.04 (0.36, 2.98) | 1.69 (0.62, 4.62) | 0.57 (0.20, 1.67) | 1.52 (0.55, 4.26) | 3.36 (0.97, 11.6) | 1.27 (0.83, 1.95) |

| High | 0.89 (0.28, 2.86) | 0.85 (0.29, 2.52) | 0.85 (0.27, 2.73) | 0.64 (0.16, 2.44) | 2.03 (0.60, 6.91) | 0.96 (0.60, 1.53) |

| Don't know | 0.11 (0.01, 1.77) | 1.22 (0.35, 4.24) | 0.37 (0.06, 2.39) | 1.03 (0.34, 3.16) | 0.82 (0.15, 4.66) | 0.87 (0.49, 1.55) |

| The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated¶ | ||||||

| Mean Likert Score | 1.14 (0.81, 1.61) | 1.18 (0.86, 1.61) | 1.40 (0.91, 2.16) | 1.05 (0.73, 1.50) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.60) | 1.14 (0.99, 1.31) |

| Exposure to secondhand smoke is dangerous to a pregnant woman and her child¶ | ||||||

| Mean Likert Score | 0.60 (0.24, 1.46) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.34) | 1.68 (0.77, 3.65) | 0.46 (0.18, 1.17) | 0.66 (0.35, 1.27) | 0.76 (0.56, 1.01) |

| Are you bothered by secondhand smoke? | ||||||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.62, 3.04) | 2.02 (0.90, 4.55) | 2.79 (1.18, 6.58) | 1.69 (0.78, 3.66) | 0.79 (0.34, 1.81) | 1.48 (1.08, 2.03) |

| Participant has a smoking ban at their workplace | ||||||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.52, 3.56) | 0.48 (0.20, 1.16) | 1.03 (0.42, 2.50) | 1.40 (0.58, 3.39) | 0.79 (0.28, 2.23) | 0.99 (0.70, 1.41) |

| Time to first cigarette in the morning | ||||||

| Within 5 minutes | 0.36 (0.11, 1.11) | 0.64 (0.24, 1.69) | 0.42 (0.10, 1.72) | 0.59 (0.19, 1.87) | 1.85 (0.57, 5.97) | 0.63 (0.40, 0.98) |

| 6–30 minutes | 0.58 (0.23, 1.49) | 0.22 (0.08, 0.64) | 1.34 (0.49, 3.66) | 1.20 (0.44, 3.29) | 1.84 (0.64, 5.30) | 0.70 (0.47, 1.04) |

| 31–60 minutes | 0.46 (0.10, 2.20) | 1.01 (0.28, 3.62) | 0.57 (0.15, 2.10) | 1.02 (0.26, 4.02) | 1.79 (0.37, 8.66) | 0.83 (0.48, 1.43) |

| Over 60 minutes | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Country | ||||||

| Ireland | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | Referent |

| Czech Republic | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.13 (0.71, 1.81) |

| France | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.51 (0.31, 0.84) |

| Italy | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.80 (0.50, 1.29) |

| Sweden | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 4.77 (2.82, 8.05) |

All variables adjusted for all other factors in the model.

4 point Likert scale: 1=Strongly agree, 2=Agree, 3=Disagree, 4=Strongly disagree.

Patterns differed slightly among nonsmokers (Table 6). Nonsmokers with home smoking bans tended to be younger. Having a ban was strongly associated with being bothered by secondhand smoke, and in most countries, with believing that smoking is harmful. In France and the Czech Republic, never smokers were more likely to have bans than former smokers. In Italy and Ireland bans were inversely associated with parental smoking. The Czech Republic was the only country where family history of lung cancer was associated with the choice to have bans. As in the unadjusted data, Swedish nonsmokers were the most likely to have home bans.

Table 6.

Odds (95% confidence intervals) of having a smoking ban at home among non-smokers#

| France (n=666) |

Ireland (n=716) |

Italy (n=716) |

Czech Republic (n=699) |

Sweden (n=766) |

All countries (n=3563) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–24 | 3.26 (1.37, 7.73) | 1.71 (0.79, 3.71) | 0.95 (0.43, 2.11) | 3.27 (1.05, 10.2) | 5.26 (1.56, 17.7) | 2.21 (1.52, 3.21) |

| 25–34 | 2.24 (1.27, 3.97) | 2.37 (1.19, 4.74) | 2.36 (1.32, 4.21) | 1.75 (0.84, 3.64) | 3.02 (1.14, 8.02) | 2.34 (1.76, 3.09) |

| 35–44 | 1.46 (0.86, 2.46) | 1.60 (0.85, 3.01) | 3.18 (1.78, 5.68) | 1.09 (0.56, 2.14) | 5.79 (1.73, 19.4) | 2.02 (1.54, 2.64) |

| 45–54 | 1.22 (0.76, 1.98) | 1.28 (0.71, 2.31) | 1.21 (0.72, 2.04) | 1.38 (0.70, 2.72) | 2.64 (1.17, 6.00) | 1.40 (1.10, 1.79) |

| + 55 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Living with partner | 0.79 (0.48, 1.30) | 0.63 (0.18, 2.23) | 0.91 (0.32, 2.60) | ------ | 0.77 (0.33, 1.83) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.92 (0.60, 1.40) | 0.87 (0.41, 1.82) | 0.76 (0.38, 1.52) | 1.01 (0.53, 1.95) | 0.84 (0.35, 2.00) | 0.90 (0.69, 1.17) |

| Never married | 0.66 (0.34, 1.27) | 0.36 (0.22, 0.60) | 0.85 (0.53, 1.37) | 0.58 (0.28, 1.20) | 0.30 (0.13, 0.68) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.70) |

| Widowed | 4.05 (1.10, 14.9) | 0.99 (0.55, 1.77) | 1.06 (0.60, 1.87) | 0.66 (0.37, 1.18) | 0.38 (0.16, 0.93) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) |

| Age at completion of education | ||||||

| <=19 | 1.17 (0.81, 1.68) | 0.78 (0.50, 1.21) | 1.18 (0.80, 1.73) | 0.87 (0.55, 1.40) | 0.83 (0.43, 1.62) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) |

| 20–25 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 26+ | 1.37 (0.76, 2.47) | 0.94 (0.44, 1.99) | 1.12 (0.60, 2.09) | 2.87 (1.08, 7.63) | 1.04 (0.48, 2.25) | 1.27 (0.95, 1.71) |

| City size | ||||||

| <5000 persons | 1.37 (0.90, 2.09) | 1.07 (0.67, 1.71) | 1.22 (0.71, 2.10) | 1.12 (0.66, 1.92) | 1.64 (0.84, 3.22) | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) |

| 5000 – 100000 | 1.35 (0.90, 2.03) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.70) | 1.09 (0.74, 1.60) | 1.16 (0.71, 1.89) | 1.79 (0.90, 3.55) | 1.18 (0.97, 1.43) |

| 100000+ | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Former smoker | 0.62 (0.41, 0.92) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.26) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.31) | 0.59 (0.35, 0.99) | 1.58 (0.85, 2.91) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) |

| One or both parents smoked | ||||||

| Yes | 0.72 (0.51, 1.02) | 0.45 (0.30, 0.67) | 0.60 (0.43, 0.85) | 0.70 (0.46, 1.06) | 0.60 (0.34, 1.04) | 0.62 (0.52, 0.73) |

| Family history of lung cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.63, 1.41) | 1.10 (0.68, 1.78) | 1.38 (0.88, 2.16) | 1.70 (1.00, 2.88) | 0.80 (0.41, 1.59) | 1.18 (0.96, 1.45) |

| Perceived risk of lung cancer | ||||||

| Low | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Medium | 0.90 (0.62, 1.32) | 0.60 (0.36, 0.99) | 0.50 (0.33, 0.77) | 1.08 (0.62, 1.91) | 0.73 (0.37, 1.43) | 0.73 (0.59, 0.89) |

| High | 1.58 (0.89, 2.80) | 1.74 (0.72, 4.23) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.16) | 2.23 (0.69, 7.20) | 0.84 (0.32, 2.19) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.55) |

| Don't know | 1.27 (0.68, 2.39) | 0.77 (0.47, 1.27) | 0.80 (0.48, 1.36) | 1.20 (0.73, 1.98) | 2.49 (0.52, 12.0) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.26) |

| The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated¶ | ||||||

| Likert scale | 1.22 (1.06, 1.42) | 1.25 (1.04, 1.51) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.58) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.41) | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30) |

| Exposure to secondhand smoke is dangerous to a pregnant woman and her child¶ | ||||||

| Likert scale | 1.13 (0.70, 1.83) | 0.76 (0.51, 1.13) | 0.62 (0.37, 1.05) | 0.43 (0.21, 0.90) | 1.57 (0.67, 3.67) | 0.82 (0.66, 1.02) |

| Are you bothered by secondhand smoke? | ||||||

| Yes | 2.56 (1.77, 3.70) | 2.74 (1.77, 4.23) | 5.08 (3.31, 7.80) | 4.77 (2.92, 7.79) | 4.80 (2.73, 8.46) | 3.46 (2.86, 4.18) |

| Participant has a smoking ban at their workplace | ||||||

| Yes | 1.42 (0.97, 2.08) | 1.22 (0.79, 1.90) | 1.07 (0.73, 1.56) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.70) | 0.80 (0.40, 1.59) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28) |

| Country | ||||||

| Ireland | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | Referent |

| Czech Republic | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.51 (1.15, 1.98) |

| France | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.99 (0.75, 1.30) |

| Italy | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08) |

| Sweden | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 4.55 (3.26, 6.35) |

All variables adjusted for all other factors in the model.

4 point Likert scale: 1=Strongly agree, 2=Agree, 3=Disagree, 4=Strongly disagree.

Women who worked outside the home in Ireland, France, and Sweden were more likely have a work smoking ban than workers in the Czech Republic (Table 7). Workers in technical positions and skilled workers were less likely than those in professional positions, and women who were widowed or living with a partner were less likely than married women to have smoking bans at work. All workers younger than 55 were more likely to have work smoking bans than workers over 55. Women who finished their education at an older age were less likely to have smoking bans, as were daily smokers and former smokers.

Table 7.

Odds (95% confidence intervals) of having a smoking ban at work#

| All countries (n=3996) |

|

|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | |

| 18–24 years old | 3.24 (1.81, 5.78) |

| 25–34 years old | 3.74 (2.65, 5.28) |

| 35–44 years old | 4.05 (2.89, 5.70) |

| 45–54 years old | 2.98 (2.19, 4.06) |

| + 55 years old | Referent |

| Marital status | |

| Married | Referent |

| Living with partner | 0.62 (0.42, 0.92) |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.85 (0.62, 1.15) |

| Never married | 0.85 (0.61, 1.18) |

| Widowed | 0.61 (0.44, 0.83) |

| Age at finish of education | |

| <=19 | Referent |

| 20–25 | 0.86 (0.59, 1.26) |

| 26+ | 0.57 (0.40, 0.82) |

| Job category (ISCO-88) | |

| Professionals (ISCO 1, 2) | Referent |

| Technical positions (ISCO 3) | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) |

| Skilled workers (ISCO 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10) | 0.53 (0.32, 0.88) |

| Unskilled workers (ISCO 9) | 0.73 (0.49, 1.11) |

| City size | |

| <5000 persons | 1.27 (0.97, 1.52) |

| 5000 – 100000 | 1.19 (0.94, 1.52) |

| 100000+ | Referent |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | Referent |

| Former smoker | 0.63 (0.49, 0.81) |

| Smokes every day | 0.73 (0.54, 0.99) |

| Smokes some days | 0.87 (0.48, 1.61) |

| Are you bothered by secondhand smoke? | |

| Yes | 1.23 (0.97, 1.55) |

| Country | |

| Ireland | 6.14 (3.73, 10.1) |

| Czech Republic | Referent |

| France | 3.21 (2.19, 4.71) |

| Italy | 0.87 (0.65, 1.16) |

| Sweden | 2.46 (1.79, 3.37) |

Included only participants who worked outside the home, had a regular work area, and were not full-time students. All variables adjusted for all other factors in the model.

Discussion

Although this study reported differing factors across countries that were associated with indoor home smoking bans, some commonalities were seen. Across several countries, younger age, being married, dislike of secondhand smoke, and personal smoking behaviors were associated with having home and workplace smoking bans. Our findings suggest that to promote smoking bans among nonsmokers, it may be useful to appeal to nonsmokers with a family history of lung cancer, or through the reinforcement of social norms and beliefs that smoking is both bothersome and dangerous to health. Among smokers, the likelihood of taking up a home smoking ban was associated with smoking dependence, and to increase the prevalence of bans, the best method is likely to be through assisting smokers to quit.

Although age and marital status have been independently associated with having smoking bans [8, 9], it is not known to what degree these variables are in part proxies for having children in the home, a strong predictor of home smoking bans in other studies [12, 13, 19]. In some but not all studies, parents with younger children (age<6) in the home appear to have higher uptake of smoking bans than parents of older children or adolescents [9, 22]; this difference may have impacted the relationship between age and smoking bans observed in our study. Increasing prevalence of smoking bans over time [5] combined with a decreasing proportion of smokers who choose to smoke in front of children [23] also may suggest there may be cohort effects in the choice to have a home smoking ban.

When comparing the 5 countries to each other, home bans were more common among nonsmokers in the Czech Republic and among all participants in Sweden. The Czech Republic appeared to have a larger proportion of smokers with lower tobacco dependence. Uptake of smoking bans appears to be widespread in Sweden in comparison to other European countries. Little is known as to whether the uptake of smoking bans has affected the smoking behaviors of Swedes, although there is speculation that smokers may be switching to snus. Nonetheless, surveys indicate that the proportion of Swedish women using snus is low (<5%) [24].

Although studies in other countries report differences by SES in the likelihood of having a smoke-free home [14], we observed little association in multivariable analyses of any association with SES, with the exception of among nonsmoking women in the Czech Republic. We also found little association between city size and smoking bans, in contrast to that seen elsewhere [14].

In some countries, particularly among nonsmokers, there was evidence that female respondents’ choice to have home smoking bans was related to parental smoking or family history of lung cancer. The differences by country are likely due to cultural variation in family ties and living arrangements. In Italy, a larger proportion of young adults live with their parents than is seen in France, the UK, or in Scandinavian countries [25]. Women also may be more strongly influenced than men by parental smoking, both in their own tobacco use and their attitudes towards tobacco [26]. There is a scant literature on how familial norms and expectations and a family history of cancer may impact women’s choices to have home smoking bans.

To our knowledge, there are few other studies that have addressed these questions in these five countries. A 2001 survey of Parisian workers found 18% exposed to secondhand smoke [27], which suggests the 2008 smokefree legislation has made a strong impact in lowering smoke exposure in France. The proportion of Italians who said smoking bans exist in their workplaces was similar to that seen in a recent population based study, which found 75% of workers said that smoking bans were respected [28]. Workplace bans were more common in Ireland, France, and Sweden, countries that have adopted comprehensive public bans; as Italy has passed similar legislation, it is not known why this survey found more workers there were exposed to secondhand smoke. Italy, along with some other European countries, does allow bars, restaurants, and indoor workplaces to have special separate and ventilated rooms for smoking, however it is estimated that a small proportion (<10%) of businesses have set up such rooms [29]. It has been reported that the smoking ban is widely observed in Italian public places, despite the fact that restaurant and café owners are no longer held responsible for its enforcement [29].

Workplace smoking bans were related to demographic factors as well as ISCO job classification, smoking behaviors, and personal preference with regards to secondhand smoke exposure. In this study, skilled workers had only half the likelihood of having a smoking ban in their workplace in comparison to professionals. Part of this difference may be explained by coworkers’ smoking, as in many countries, individuals from lower social classes tend to smoke at higher rates than those from higher social classes [30]. Thus, the implementation of workplace bans may serve to lessen social class disparities related to tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke.

Workplace smoking bans appear to decrease cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence among workers [4, 31]. However, the possibility also exists that smokers consuming fewer cigarettes may alter their smoking behavior to compensate, perhaps by taking deeper puffs or smoking more of the cigarette, or via displacement of smoking to other environments. The cross-sectional nature of data collection left us unable to determine whether workplace smoking bans had any effect on smoking behaviors in the home. Some, but not all, studies have suggested that smokers working under bans are more likely to have a ban at home [9, 10, 32]. This study found no association between workplace smoking bans and the implementation of a ban in the home.

This survey was limited by its brief length, which did not allow us to collect additional information potentially relevant to the implementation of smoking bans, such as the presence of children or other smokers in the home. An additional limitation is that all data were collected by self-report. There have been concerns about the validity of self-reported data on home smoking bans, particularly in households with children [13, 33]. Strengths of the study include the large sample size and the population-based design. However the participation rates were suboptimal, and varied by country, perhaps due to cultural factors which influence willingness to participate in a telephone survey. It is not known whether any association exists between smoking bans and willingness to participate in telephone surveys. There was also evidence, in some countries, that our sample included a larger proportion of professional women than should be expected in a population-based sample [34]. This may be due to the requirement of having a home telephone, or due to differences by social class in the willingness to participate in our survey. Although only a small proportion of eligible women who refused participation also provided demographic information, refusers appeared to be generally younger than participants, and were more frequently employed as technical workers or as skilled workers.

A limitation of the study was data collection by telephone survey, leaving us unable to independently verify the statements of participants. We had chosen this data collection approach to be able to reach a large sample of women in each country. Results from previous studies indicate self-reported data on active and passive smoking are fairly reliable [35, 36]. Additionally, mobile phone users were not included in the phone lists from which we drew the numbers. Despite this, the stratified sampling approach allowed the study to include a proportionally representative sample of younger women. Nonetheless, there may be unknown differences between users of mobile phones and home phones which may affect study results.

In conclusion, we observed differences across the 5 European countries in uptake of home smoking bans and factors related to their use. While nonsmokers’ choice to have a home smoking ban was associated with beliefs and personal preferences, smokers were more often influenced by their tobacco dependence and regularity of cigarette use. The higher rates of home smoking bans among younger age groups were likely in part due to having young children in the home, but may also signal a demographic change in the acceptance of smoking bans. With regards to work bans, there were disparities evident by job classification and age. More widespread implementation of workplace bans may lessen these class disparities in secondhand smoke exposure.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs Maria Leon-Roux, Donna Vallone, and Jane Allen for their assistance. This study was a part of the Women in Europe Against Lung Cancer and Smoking (WELAS) project, which received funding from the European Union, in the framework of the Public Health Programme.

References

- 1.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, World Health Organization., International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heck JE, Jacobson JS. Asthma diagnosis among individuals in same-sex relationships. J Asthma. 2006;43:579–584. doi: 10.1080/02770900600878289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cesaroni G, Forastiere F, Agabiti N, Valente P, Zuccaro P, Perucci CA. Effect of the Italian smoking ban on population rates of acute coronary events. Circulation. 2008;117:1183–1188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. Bmj. 2002;325:188. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janson C, Kunzli N, de Marco R, Chinn S, Jarvis D, Svanes C, Heinrich J, Jogi R, Gislason T, Sunyer J, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Anto JM, Cerveri I, Kerhof M, Leynaert B, Luczynska C, Neukirch F, Vermeire P, Wjst M, Burney P. Changes in active and passive smoking in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:517–524. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00106605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweeney CT, Shopland DR, Hartman AM, Gibson JT, Anderson CM, Gower KB, Burns DM. Sex differences in workplace smoking policies: results from the current population survey. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2000;55:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shavers VL, Fagan P, Alexander LA, Clayton R, Doucet J, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Workplace and home smoking restrictions and racial/ethnic variation in the prevalence and intensity of current cigarette smoking among women by poverty status, TUS-CPS 1998–1999 and 2001–2002. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(Suppl 2):34–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.046979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzales M, Malcoe LH, Kegler MC, Espinoza J. Prevalence and predictors of home and automobile smoking bans and child environmental tobacco smoke exposure: a cross-sectional study of U.S.- and Mexico-born Hispanic women with young children. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merom D, Rissel C. Factors associated with smoke-free homes in NSW: results from the 1998 NSW Health Survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shopland DR, Anderson CM, Burns DM. Association between home smoking restrictions and changes in smoking behaviour among employed women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(Suppl 2):44–50. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.045724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kegler MC, Malcoe LH. Smoking restrictions in the home and car among rural Native American and white families with young children. Prev Med. 2002;35:334–342. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg CJ, Cox LS, Nazir N, Mussulman LM, Ahluwalia JS, Ellerbeck EF. Correlates of home smoking restrictions among rural smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:353–360. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilpin EA, White MM, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Home smoking restrictions: which smokers have them and how they are associated with smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:153–162. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolte G, Fromme H. Socioeconomic determinants of children's environmental tobacco smoke exposure and family's home smoking policy. Eur J Public Health. 2008 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino GA, Hatsukami D, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins KA, Toll BA. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior : an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Reading, Mass.; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran S, Glazier G, Armstrong K. Women smokers' perceptions of smoking-related health risks. J Womens Health. 2003;12:363–371. doi: 10.1089/154099903765448871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escoffery C, Kegler MC, Butler S. Formative research on creating smoke-free homes in rural communities. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:76–86. doi: 10.1093/her/cym095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenbaum L, Kanyas K, Karni O, Merbl Y, Olender T, Horowitz A, Yakir A, Lancet D, Ben-Asher E, Lerer B. Why do young women smoke? I. Direct and interactive effects of environment, psychological characteristics and nicotinic cholinergic receptor genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:312–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001774. 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Labour Office. International standard classification of occupations : ISCO-88. Geneva: International Labour Office; 1990. Rev. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Donate AP, Johnson-Kozlow M, Hovell MF, Gonzalez Perez GJ. Home smoking bans and secondhand smoke exposure in Mexico and the US. Prev Med. 2009;48:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borland R, Mullins R, Trotter L, White V. Trends in environmental tobacco smoke restrictions in the home in Victoria, Australia. Tob Control. 1999;8:266–271. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, Bulik C, Sullivan PF. Cigarettes and oral snuff use in Sweden: Prevalence and transitions. Addiction. 2006;101:1509–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giuliano P. Living arrangements in Western Europe: Does cultural origin matter? Journal of the European Economic Association. 2007;5:927–952. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyas SL, Pederson LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tob Control. 1998;7:409–420. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alcouffe J, Fau-Prudhomot P, Manillier P, Lidove E, Monteleon PY. Smoking among workers from small companies in the Paris area 10 years after the French tobacco law. Tob Control. 2003;12:239–240. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tramacere I, Gallus S, Fernandez E, Zuccaro P, Colombo P, La Vecchia C. Medium-term effects of Italian smoke-free legislation: findings from four annual population-based surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:559–562. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.084426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binkin N, Perra A, Aprile V, D'Argenzio A, Lopresti S, Mingozzi O, Scondotto S. Effects of a generalised ban on smoking in bars and restaurants, Italy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:522–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, Crialesi R, Grotvedt L, Helmert U, Lahelma E, Lundberg O, Matheson J, Mielck A, Rasmussen NK, Regidor E, do Rosario-Giraldes M, Spuhler T, Mackenbach JP. Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. Bmj. 2000;320:1102–1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7242.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullally BJ, Greiner BA, Allwright S, Paul G, Perry IJ. The effect of the Irish smoke-free workplace legislation on smoking among bar workers. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:206–211. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borland R, Yong HH, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Anderson S, Fong GT. Determinants and consequences of smoke-free homes: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii42–iii50. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumford EA, Levy DT, Romano EO. Home smoking restrictions. Problems in classification. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czech Statistical Office. Employment in national economy by regions. [cited January 30 2009];2008 Jul 15; 2008 Available from: http://www.czso.cz/csu/2008edicniplan.nsf/engt/810040222A/$File/31150821.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Assaf AR, Parker D, Lapane KL, McKenney JL, Carleton RA. Are there gender differences in self-reported smoking practices? Correlation with thiocyanate and cotinine levels in smokers and nonsmokers from the Pawtucket Heart Health Program. J Womens Health. 2002;11:899–906. doi: 10.1089/154099902762203731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivieri M, Poli A, Zuccaro P, Ferrari M, Lampronti G, de Marco R, Lo Cascio V, Pacifici R. Tobacco smoke exposure and serum cotinine in a random sample of adults living in Verona, Italy. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57:355–359. doi: 10.1080/00039890209601421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]