Abstract

Epothilones are natural compounds isolated from a myxobacterium at the beginning of the 1990s, and showed a remarkable anti-neoplastic activity. They act through the same mechanism of action of paclitaxel, by stabilizing microtubules and inducing apoptosis. Although, their chemical structure, simpler than taxanes, makes them more suitable for derivatization. Their interesting pharmacokinetic and bioavailabilty profiles, and the activity against paclitaxel-resistant cell lines make them interesting therapeutic agents. Here a brief historical perspective of epothilones is presented, since their isolation, the identification of their mechanism of action and activity, to the recent clinical trials.

Introduction

Natural products have been traditionally a valuable source of novel and interesting chemical compounds, and a remarkably high number of new structures keeps being identified each year.1

Despite the structural complexity often associated with them, they provide an undoubtful advantage from the perspective of scaffold novelty. Indeed, complexity itself, and the presence of stereogenic centers can significantly increase the success in designing new drugs.2

Epothilones are natural compounds belonging to the microtubule stabilizing antimitotic agents (MSAA) class, a series of anti-neoplastic molecules with a common mechanism of action involving tubulin binding. The first example of MSAA was paclitaxel3 (Taxol™, PTX, 1, scheme 1).

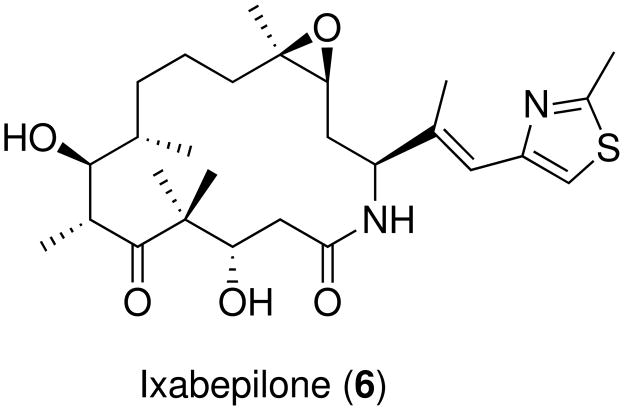

Scheme 1.

Paclitaxel and Epothilones A–D

Epothilones are 16-membered macrocyclic lactones identified by Höfle and co-workers4 in 1996. Epothilones A (EpoA, 2) and B (EpoB, 3) shown in scheme 1, are products of a myxobacterium (Sorangium cellulosum, strain So ce90) isolated from soil samples collected near the banks of Zambesi river in southern Africa.5 The molecules showed narrow antifungal activity, but most importantly, in vitro cytotoxic activity in breast and colon tumor cell lines in a National Cancer Institute anticancer screening program.6 In 1995, during a screening campaign searching for compounds with activity similar to PTX, Bollag and co-workers at Merck elucidated for the first time their mechanism of action.7 In their experiments, epothilones inhibited competitively the binding of [3H]-paclitaxel to tubulin, suggesting a common binding site. Their comparative assays presented a similar kinetic profile, but epothilones showed significantly higher potency. Further activity studies8 showed an influence in stabilized microtubule appearence, but 3 showed to be orders of magnitude more active than PTX on some paclitaxel-resistant cell lines. Eventually, two more derivatives lacking the epoxide groups, epothilones C (EpoC, 4) and D (EpoD, 5) were identified as biosynthetic precursors of 2 and 3,9 and showed an improved activity profile.10

Microtubules

Microtubules are structural proteins found in cytoskeleton in all eukaryotic cells.11 They play crucial roles in intracellular transport,12 secretion,13 cell motility,14 and most importantly in the mitosis process.15–17 The main structural component of microtubules is the α, β-tubulin heterodimer. Tubulin is a globular protein of about 55 kD and is present in different isoforms.18,19 Initially, α and β monomers form stable heterodimers (Kd = 10−6),20 that associate polymerizing to form protofilaments (initiation phase).21,22

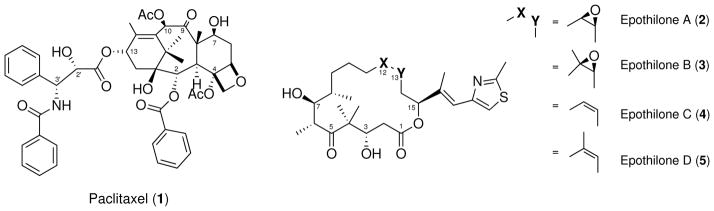

In the next phase (polymerization/elongation), protofilaments associate in a parallel fashion to form hollow cylinders.23–25 The growth is GTP-dependent,26,27 and polarized, occurring more rapidly at one extremity (plus end, figure 1).27,28 In humans and other mammalia microtubules are constituted by an average of 13 protofilaments, resulting in cylinders with a radius of 24 nm25 (Figure 1). Microtubules are highly dymamic structures,27 and the equilibrium between their growth (polymerization) and shrinkage (depolymerization) is strictly regulated by numerous associated proteins.28 Due to their critical role in mitosis, microtubules are an important target in anti-neoplastic therapies. Several molecules are known to affect the dynamic equilibrium of micro-tubules and they are subdivided in two main classes, stabilizers and destabilizers. Beside taxanes and epothilones, microtubule stabilizers include discodermolide,29 eleutherobin30 and sarcodic-tyins,31 laulimalide,32 peloruside33 and zampanolide.34 The most prominent microtubule destabilizing agents are colchicine,35 combretastin A-4,36 podophyllotoxin,37 vinblastine38 and other vinca alkaloids.39

Figure 1.

Microtubule schematic structure. α and β monomers are colored as green and azure, respectively. The arrow indicates indicates parallel alignment of tubulin protofilaments. The (+) and (−) symbols indicate protofilament polarization.

Mechanism of action

The activity of epothilones, like other MSAA, is associated to the binding to specific loci on the tubulin surface, promoting its polymerization.40 Stabilized microtubules are more tightly packed, formed by only 12 protofilaments,41,42 and with a diameter of only 22 nm.42

Epothilones also prevent microtubules depolymerization induced by calcium.7 This results in hyperstable microtubules that halt the mitosis process at the G2/M phase, and trigger the apoptosis process.7,40,43 For this reason, MSAA are then often referred to as mitotic spindle poisons.44 They inhibit competitively binding of [3H]-paclitaxel to β-tubulin with IC50 of 2.3 μM.45 In general, the activity of epothilones is reported to be 2 to 4 times higher than that of PTX, with a EC0.01 of 5 μM in the standard Bristol-Myers Squibb assay.46 Some experiments show that they can also induce apoptosis at concentrations that are lower than those required to induce the arrest of mitotic cell cycle. For this reason, it has been hypothesized that epothilones can act also by altering the dynamic equilibrium of the intracellular microtubule components (α, β-heterodimers vs. polymers).47 Computational modeling experiments48 suggested that epothilones not only stabilize the structure of microtubules, but also modulate their function and mechanics, resulting in less stiff structures. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation results49 predicted that epothilones can traverse the pores present in the microtubule walls easier than PTX; this was ascribed to the more flexible structure of epothilone macrolactone ring compared to the rigid core of PTX. They are effective against a wide range of cancer cell lines, including prostate, colon, lung, breast, ovarian bladder, squamous cell, leukemia and fibroblast.50

Most notably, they showed a potency between 2000 and 5000 times higher than PTX against taxane-resistant cell lines.40,51 The mechanism of resistance to MSAA and other anti-neoplastic agents is mainly ascribed to two factors: P-glycoprotein overexpression and tubulin mutations. P-glycoprotein 1 (PGP, or MDR1)52 is a membrane-associated protein involved in multidrug resistance. PGP is an active cellular transport pump that reduces the absorption of drugs and their intracellular concentration.52 Many cancer cell lines overexpress PGP, resulting in resistance to drugs.7 Epothilones are very poor substrate for PGP, and therefore are less sensitive to MDR1-resistance, resulting more effective than PTX.7 Mutations occurring on the tubulin M loop40 are mainly responsible for the resistance to PTX, but epothilones and taxanes have different resistance profile.40 Mutations on βPhe272, for example, can result in 24-fold reduction of PTX activity, while EpoB conserves its activity.40 Instead, mutations on residue βThr276 reduces considerably the activity of epothilones, while PTX is only minimally affected. Also, epothilone resistance was reported to be much harder to induce than PTX resistance in vitro experiments.40

These differences in mutation sensitivity have been used to infer the interaction pattern of the two molecular classes with tubulin, and help predicting their binding mode.40,53–55 (see Common pharmacophores). Another cause of resistance can be the expression of different β-tubulin isoforms. The most abundant and commonly expressed isoform is the βI, while βIII is prevalently present in neuronal tissues.18 PTX shows higher affinity for the βI isoform than for the βIII isoform,19 and for this reason, cancer cells can develop resistance to PTX by over-expressing βIII isoforms. Epothilones, on the other hand, bind equally to both isoforms18 and maintain their activity on PTX-resistant cell lines.

Synthesis and Structure-activity relationship

Following the identification of epothilones, Höfle et al.56 reported structure and absolute stereochemistry of EpoA obtained by combined X-ray crystallography and NMR. A name was proposed for the newly discovered compounds that was based on the chemical features identified in the molecule: epoxyde, thiazole, ketone. The structure was found to be more simple than PTX, but still challenging due to the presence of several stereogenic centers and the epoxide group. Nevertheless, shortly after the structure determination, several groups57–59 attempted the total synthesis.

The first to succeed was Danishefsky’s group, providing a viable synthetic route to obtain 2 through an intramolecular ester enolate-aldehyde condensation.57 During years, many alternative methods were suggested,46,51,60–73 including combinatorial synthesis,51 and bacterial fermentation,74 enabling the production of a large number of analogs in significant quantities, and a vast amount of data on the structure-activity relationships (SAR). This allowed also statistical computational methods, like quantitative SAR (QSAR), to be applied to rationalization of the activity.53,75–78

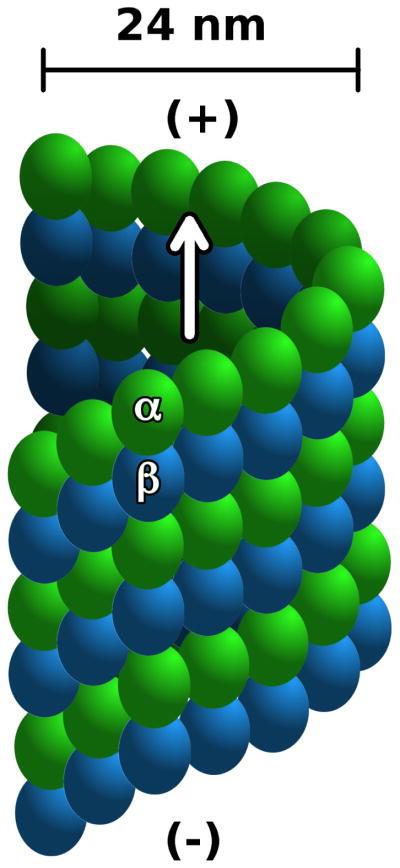

A brief summary of the SAR of epothilones is reported, following the region subdivision proposed by Nicolaou et al.51 (see Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Epothilone SAR regions.

Ring size is essential to the activity and 16-membered rings are the most active ones. Derivatives with smaller rings are inactive,40,44,76,79 and naturally occurring 18-membered ring epothilones are between 10 and 100 times less active.80

Region A

7-hydroxyl is essential to the activity;40,51,81 stereochemistry of 7(S) and 8(S) carbons is essential;51 rigidified and C9–C10 bridged derivatives are inactive;82 8,8 di-methyl and 8,8 di-hydroxyl are not tolerated.51,83

Region B

12–13-desoxy derivatives show increased activity, better pharmacokinetics and bioavailability; 10,44,54 methyl group in 12 increases activity over hydrogen; C12 substituents larger than methyl group (ethyl, propyl, acetal cyclohexyl) are tolerated;51 C12–C13 oxazoline bridged are tolerated; 82 rigidified and C10–C12 bridged derivatives are inactive;82 derivatives containing nitrogen in position 12 (azathilones) are tolerated;67,84 C12–C13 cyclopropyl derivatives are tolerated.

Region C

Substituents containing aromatic groups are essential in C15;51,62 chirality of C15 is essential; aromatic groups attached directly to C15 are not tolerated;53,62 oxazole and pyridine rings tolerated;40,64 heterocycles fused with C27 (benzimidazole, benzothiazole, quinoline) are tolerated;53,84 bulky groups attached to C27 are not tolerated; position of hydrogen-bond acceptor atoms in heterocycles is important;53,85 substituents attached to C21 are tolerated.85

Region D

C1-carbonyl essential to activity;40,54 3-hydroxyl not essential;85 4,4-gem-diethyl is not tolerated; chirality of C6 essential; larger groups attached to C6 are tolerated; C6–C8 bridged derivatives are not tolerated;86–88 large groups attached to C22 are not tolerated;89 lactone oxygen can be replaced with nitrogen.53 To date, an estimate of more than 400 epothilone derivatives have been synthesized.

Common pharmacophores

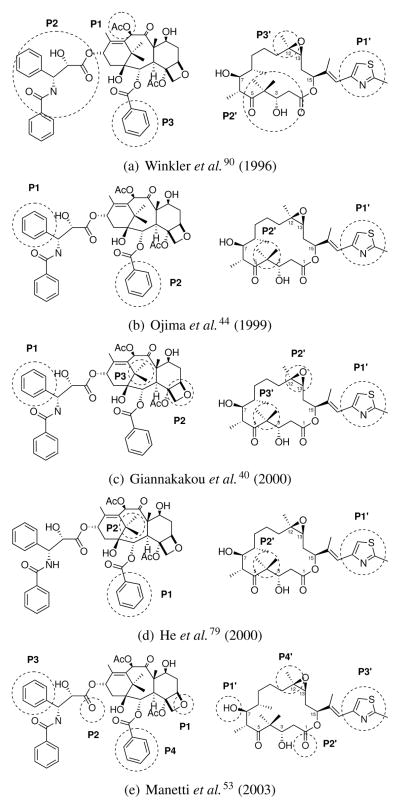

The identification of a competitive binding for taxanes and epothilones drew a lot of interest in trying to identify structural commonalities between such different molecular structures. Since the availability of experimental evidence supporting a shared binding site, attempts were made to suggest a common pharmacophore: a model able to recapitulate structural similarities between the two chemical classes and identify their shared features. A summary of common pharmacophores discussed here is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Common pharmacophore models proposed for taxanes and epothilones, with publication dates in parentheses. Pharmacophoric features are shown on structures of PTX (1, left) and EpoB (2, right), and labeled P and P′, respectively.

The first common pharmacophore was suggested by Winkler and Axelsen in 199690 (Figure 2(a)). Their pharmacophore was solely based on the steric hindrance and conformational similarities between different molecular portions, since no SAR was available at the time. The model suggested the overlap of PTX features 10-acetyl (P1), C13 side chain (P2) and 2-benzoyl ring (P3) on epothilone thiazole ring (P1′), C1–C6 region (P2′) and C12 (P3′).

With the identification of other MSAA, common pharmacophores extended to include them were proposed.54,75,79,91

In 1999, Ojima et al.44 used a taxane derivative as a template to generate their common pharmacophore. The template conformation was obtained by 2D-NOE spectroscopy analysis, while conformations of epothilones and other MSAA44 were generated by short high-temperature MD simulations, then aligned over the template. In their model, PTX 3′-benzamide (P1) and 2-benzoyl ring (P2) overlap epothilone thiazole ring (P1′) and 4-gem-dimethyl group (P2′), respectively (Figure 2(b)). The model explained the role of C3 hydroxyl group, and the improved activity profile of 12,13-desoxy epothilones.

Mutagenesis studies and structural data were used to build the common pharmacophore proposed by Giannakakou et al.40 in 2000. In particular, three main mutations β276T→I, β284R→Q, β272P→V were known to influence dramatically the activity and induce resistance to both PTX and epothilones, affecting their ability to stabilize microtubules and inhibit cell proliferation.92 The coordinates of docetaxel extracted from the EC model of tubulin93 were minimized and used as a template for taxanes. Multiple conformations of EpoB were obtained by sampling low-energy conformations generated with MD simulations.40 Conformational analysis suggested a conserved pattern in distances between features of taxane and epothilone. The distance patterns were then used as reference points for generating two alternative alignments. Further molecular docking and explicit solvent MD simulations on the EC model, and mutagenesis data, were used to discriminate between the two, resulting in alignment shown in Figure 2(c): 3′-phenyl ring (P1), oxetane ring (P2) and 15-gem-dimethyl (P1) of PTX overlap thiazole ring (P1′), epoxyde (P2′) and 4-gem-dimethyl (P3′) of epothilones, respectively.

In the same year, another model was proposed by He et al.79 based on baccatin III,94 a taxane derivative missing the C13 chain. Baccatin III has an activity profile similar to paclitaxel, although significantly lower; their docking results in the EC structure suggested the lack of the C13 chain does not affect the overall binding mode, implying that C13 chain is not essential to binding. For this reason, they considered the taxane 2-benzoyl ring (P1) as corresponding pharmacophoric feature for thiazole ring (P1′), and the 15-gem-dimethyl (P2) for the 4-gem-dimethyl (P2′), (Figure 2(d)). Their model showed some similarities to one of the alternative models identified by Giannakakou et al.40) providing a rationalization for variations on the C15 chain.51,62 The model was also extended to include other MSAA.79

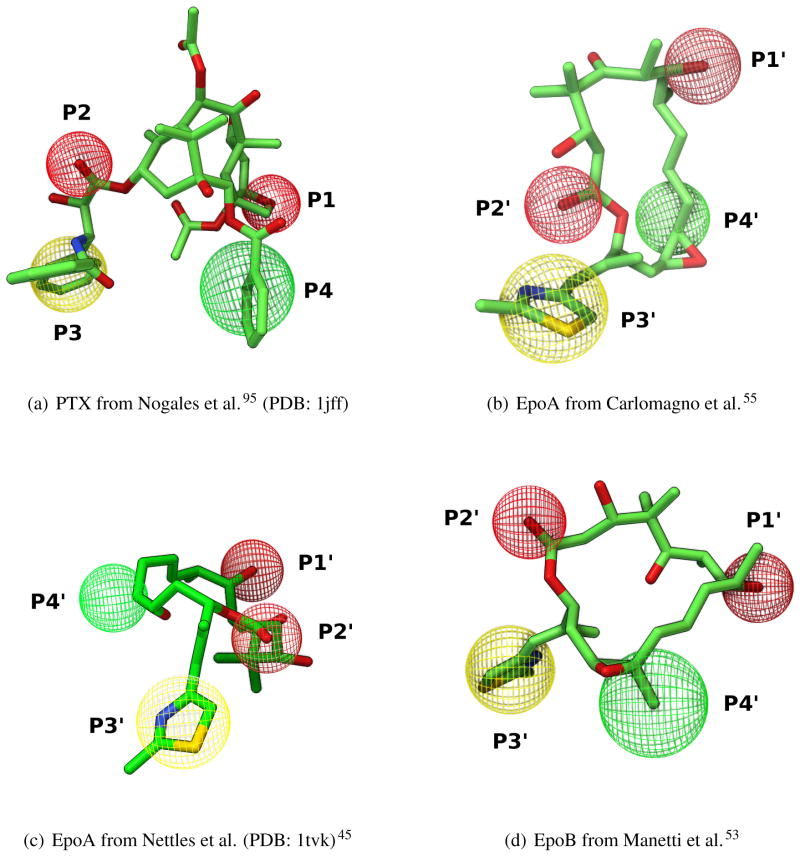

In 2001, with Manetti et al.,53 we proposed a common pharmacophore based on the combination of SAR and structural data. The structure of tubulin95 refined at 3.5 Å was used to extract the minimal set of essential residues to build a pseudoreceptor model.96,97 Interactions established by PTX in its bound conformation were used to identify which pharmacophoric features to include in the model (Figure 3(a)). These features were then used to find an optimal overlap for epothilones by filtering a set of pre-generated conformations. The proposed common pharmacophore (Figures 2(e)) links PTX polar groups oxetane (P1) and 1′-carbonyl (P2), with corresponding epothilone groups 7-hydroxyl (P1′) and 1-carbonyl (P2′). Consequently, PTX 3′-phenyl (P3) and 2-benzoyl (P4) overlap with epothilone thiazole (P3′) and C12 substituent (P4′). Tridimensional representation of the pharmacophoric features of the model are showin in Figure 3(a) and 3(d). The resulting superposition was in agreement with mutagenesis40,92 and SAR (especially for 7-hydroxyl group).53,54 The alignment allowed to generate a predictive 3D-QSAR model for taxane and epothilones,53 that eventually was applied with success to evaluate a series of newly synthesized derivatives.77 Overall, it is possible to appreciate a progressive increase during years in accuracy in the definitions of features of common pharmacophores proposed. The trend reflects the increase of knowledge gathered by investigators, especially with the availability of efficient synthetic routes able to generate a large number of epothilone derivatives.

Figure 3.

Comparison of tridimensional pharmacophoric features defined in the model of Manetti et al.54 mapped on PTX (a) and epothilones (b–c). Ligand conformations were aligned and oriented on the structure of tubulin 1jff as template, and are shown as sticks colored by atom type: carbon green; oxygen: red; nitrogen blue; sulfur: yellow. Features are shown as labeled wireframe spheres (hydrogen bond acceptor red; aromatic yellow; aliphatic green.)

Molecular structure data

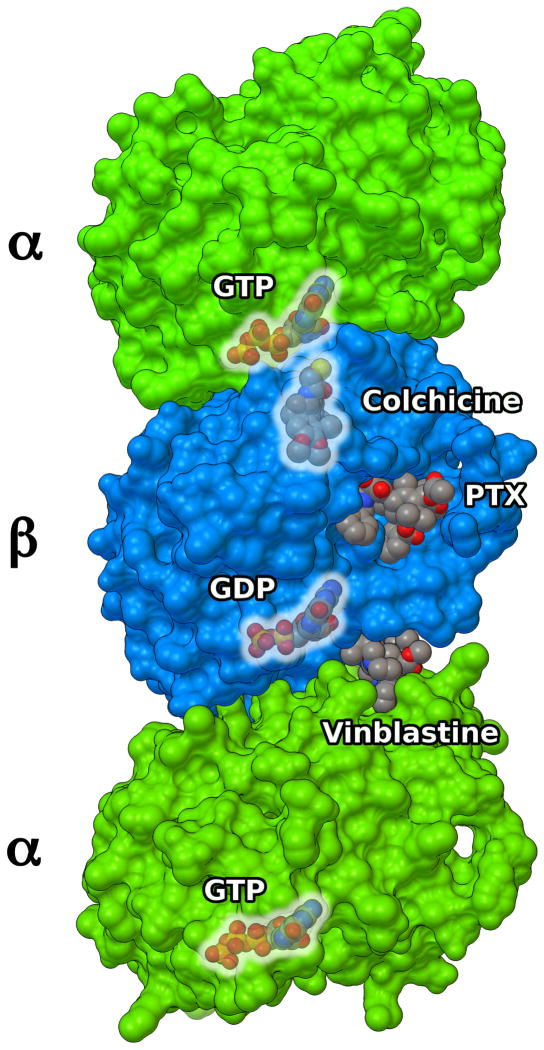

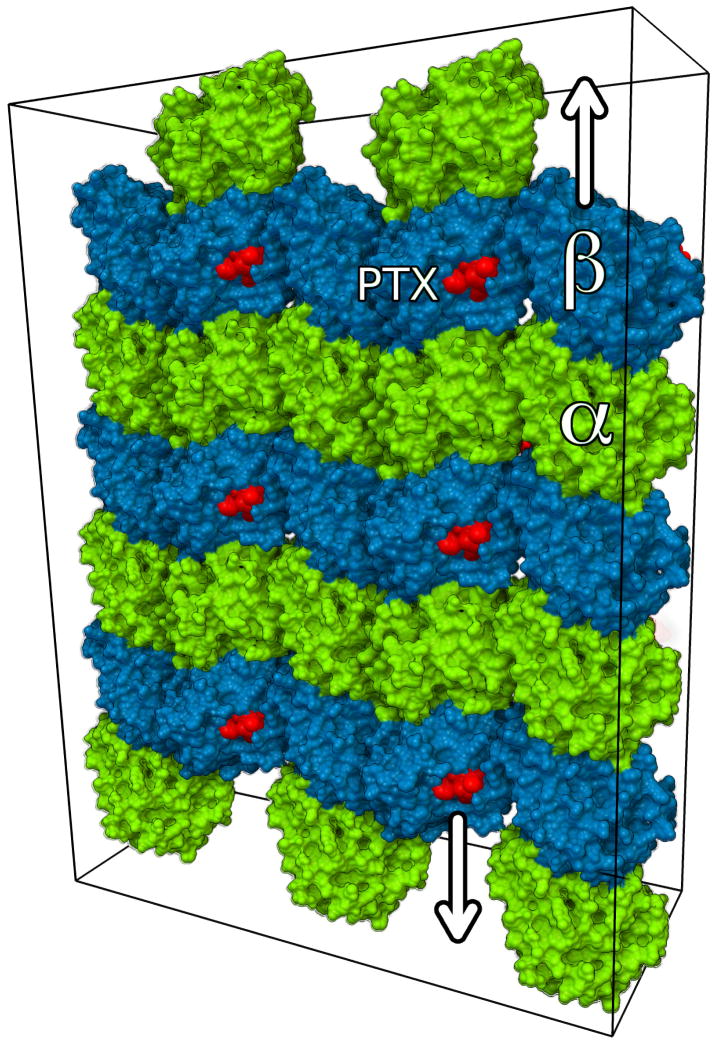

The first atomic model of the complex between tubulin and a ligand was determined by Nogales and co-workers,93 and deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB)98 as 1tub (Figure 4). The model showed the structure of the α, β-tubulin dimers fitted to a low resolution (3.7 Å) density map obtained by electron crystallography (EC) of Zn-stabilized sheets (Figure 5), where tubulin filaments are arranged in anti-parallel fashion.93

Figure 4.

α, β, α-tubulin trimer showing locations of different binders. Protein structure is shown as MSMS surface,99 with α and β monomers colored as green and azure, respectively. Ligands (GTP, GDP, PTX, vinblastine and colchicine) are shown as CPK spheres and colored by atom type (gray: carbons, blue: nitrogen, red: oxygen, orange: phosphate; yellow sulfur). Structures of colchicine and vinblastine were obtained by superimposing PDB structures from 1sa022 and 1z2B100 on 1jff.93

Figure 5.

Section of anti-parallel zinc-stabilized α, β-tubulin sheets (PDB: 1jff). Protein structure is shown as MSMS surface,99 with α and β monomers colored as green and azure, respectively. PTX is shown as CPK spheres (red). Arrows show anti-parallel alignment of protofilaments.

They identified two main functional domains on each monomer (GTP binding domain; motor/MAP-binding domain)93 and, on the β-monomer only, a drug-binding domain where the structure of the taxane derivative docetaxel was resolved. The model was further refined with a slightly increase in resolution (3.5 Å), improved residue conformation accuracy, and with PTX bound in the active site (PDB: 1jff).95

These structures represented a tremendous improvement in the understanding interactions between taxanes and tubulin, but there was still great uncertainty about which of these interactions were conserved in epothilone binding.

Nettles et al. in 2004 presented an atomic model of 2 bound to α, β-tubulin (PDB: 1tvk).45 The model was obtained with a combined approach of EC, NMR conformational analysis and molecular modeling. The ligand conformation in the structure showed a minimal overlap with the PTX binding mode, implying a promiscuous binding for the tubulin pocket.45

It was already hypothesized that epothilones and taxanes could bind tubulin in a slightly different fashion, given the different effect of mutations on the two classes.40,92 The structural data from the complex suggested that despite the fact that epothilones and taxanes indeed shared the same binding site, it was not possible to define any common pharmacophore.

Although, the resulting interactions pattern between the ligand and the protein did not match with most available mutagenesis data,40,51,62,92 nor structure-activity relationships.77,101 Also, the ligand conformation (Figure 3(c)) was unlike other epothilone conformations previously reported,102 as determined in solid-state,56 in solution103 or bound to CytP450.104

Eventually, the conformation of 2 and 3 bound to non-polymerized tubulin in solution were determined also by NMR by Carlomagno et al.101,105,106 Interestingly, the macrolide ring conformation (Figure 3(b)) determined for the two ligands strongly disagreed with conformation of EpoA in the EC model,106 while being in good agreement with the common pharmacophore and receptor interactions proposed by Manetti et al77 (Figure 3(d)).

The model was further questioned when rigidified C6–C8 epothilone derivatives designed to mimic the proposed EC-derived bioactive conformation showed minimal or no biological activity.87 Assays against A2780 human ovarian cancer, PC3 prostate cancer,86 and other cell lines88 were all unsuccessful, prompting the re-examination of the model.88

Discrepancies between the different experimental models, and failures in derivative design revamped the hypothesis of a similar interaction pattern and a common pharmacophore.55,77,107

The results of another combined approach with experimental methods (mutagenesis, cytotoxicity) on in vivo microtubules, and computational models108 suggested that amino acids critical for paclitaxel activity are also essential for the cytotoxicity of EpoB. One of the goals of the work was to try to address the limitations of the current models (non-polymerized tubulin or zinc-induced sheets).108 The results remarked once more that similar interactions are responsible for the biological activity of the two classes, even though some differences were found.108

Recently, two crystallographic models109 of α, β-tubulin complexed with stathmin-like protein RB3, tubulin tyrosine ligase were published: one model was complexed with EpoA and the other with zampanolide, covalently bound to tubulin.34 The complexes suggest a mechanism of action involving a secondary structure re-arrangement of the M-loop adjacent to the taxane binding site.109 The curved structure in the models is consistent with the unassembled tubulin, while the taxane site presented only small differences. The orientation of EpoA reported in the structure is different from the one in the EC structure, while being consistent with the NMR experiments.101,106,110

Clinical trials and side effects

One of the main advantages of epothilones over PTX is their water solubility. In fact, taxanes are usually poorly soluble and require to be delivered with solvents, like CremophorEL111 and polysorbate 80,112 that can cause severe hypersensitivity and affect cardiac function.111 Moreover, epothilones do not present endotoxin activity; paclitaxel induces macrophage-mediated activation that results in the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide.113 However, severe side effects have been reported in several clinical trials, including neutropenia,114 fatigue, mucositis, peripheral toxicity,115,116 diarrhea.117

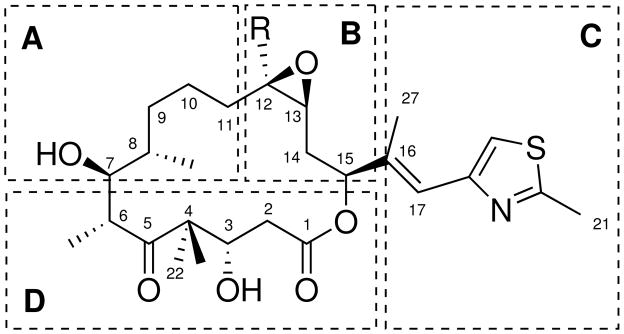

Epothilone derivatives were tested in clinical trials as anticancer chemotherapic agents,118–120 in a variety of tumor types, notably prostate,121 non-small-cell lung cancer,122 breast, colon, pancreatic, cervical and gastric cancers.122 In particular, KOS1585 (4) from Kosan Biosciences is undergoing phase I evaluation for advanced solid tumors;123 patupilone (EpoB, Epo906) from Novartis124 and sagopilone, a derivative of EpoB from Bayer125 are in phase II clinical trials. Notably, ixabepilone (Ixempra™, azaepothilone B, BMS-247550, 6, scheme 3) from Bristol-Myers-Squibb was the first epothilone approved by FDA for usage outside clinical trials. 6 is a lactam derivative of 5: due its resistance to esterase cleavage, it shows an increased metabolic stability coupled with potent polymerization activity and retained activity against PTX-resistant cell lines.126 In 2007, 6 was approved for the treatment of aggressive metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer.126,127

Scheme 3.

First FDA approved epothilone, ixabepilone.

Conclusions

Since their identification, epothilones drew a lot of interest from both academia and industry.

The remarkable chemical, biological and pharmacokinetic properties, the large activity spectrum against multiple cancer types and the ability to overcome MDR make epothilones an appealing target for drug design. In fact, one new drug was already approved by FDA, while many clinical trials are still running. Hundreds of derivatives have been synthesized and tested against numerous cancer types, providing potential new drugs to overcome drug-resistance.

Nevertheless, despite tremendous amount of research performed so far, many details of molecular basis of their mechanism of action and the emergence of drug resistance are yet unclear. Although, a deeper exploration of the structural aspects of the interactions with tubulin is still necessary, and more experimental evidence is necessary to fully clarify both interactions at atomistic level and the dynamic behavior of such a complex system as the microtubules.

The search for a well-defined common pharmacophore between taxanes and epothilones, revamped by the recent results from NMR and crystallography studies, is definitely an area deserving further investigation. Epothilones have been proven to bind competitively with PTX, therefore we believe a common pharmacophore for the two classes is likely. The availability of new experimental data and structural insights on tubulin is making its identification more feasible, allowing to recapitulate and rationalize the considerable amount of data collected in many years of research.

Likely, the common pharmacophore could be also be extended to include other MSAA stabilizing agents sharing the same mechanism of action. The ambitious goal would then be a general common pharmacophore that could boost significantly the drug design of future potent anti-neoplastic agents and overcome drug-resistance.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Teresa Carlomagno for kindly providing the NMR-derived structure of the tubulin-EpoA complex. Molecular structures in figures were made using Python Molecular Viewer v.1.5.6.128 This work is supported by grant R01-GM069832 from the National Institutes of Health. This is manuscript 26072 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- PTX

paclitaxel

- EpoA

epothilone A

- EpoB

epothilone B

- EpoC

epothilone C

- EpoD

epothilone D

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- GDP

guanosine diphosphate

- EC

electron crystallography

- MD

molecular dynamics

- SAR

structure-activity relatioship

- QSAR

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

References

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Journal of natural products. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiff PB, Horwitz SB. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1980;77:1561–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerth K, Bedorf N, Höfle G, Irschik H, Reichenbach H. The Journal of antibiotics. 1996;49:560. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altmann K-H. The Epothilones: An Outstanding Family of Anti-tumour Agents: from Soil to the Clinic. Vol. 90 Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grever MA, Schepartz SA, ACB Seminars in oncology. 1992;19:622–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollag DM, McQueney PA, Zhu J, Hensens O, Koupal L, Liesch J, Goetz M, Lazarides E, Woods CM. Cancer Research. 1995;55:2325–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kowalski RJ, Giannakakou P, Hamel E. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:2534–2541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerth K, Steinmetz H, Höfle G, Reichenbach H. The Journal of antibiotics. 2001;54:144. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J, Kim SH, Bifano M, DiMarco J, Fairchild C, Gougoutas J, Lee F, Long B, Tokarski J, Vite G. Organic Letters. 2000;2:1537–1540. doi: 10.1021/ol0058240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conde C, Cáceres A. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrn2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang S, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG, Popov SV. Nature cell biology. 1999;1:399–403. doi: 10.1038/15629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wacker I, Kaether C, Kromer A, Migala A, Almers W, Gerdes HH. Journal of Cell Science. 1997;110:1453–1463. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennis JR, Howard J, Vogel V. Nanotechnology. 1999;10:232. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawin KE, LeGuellec K, Philippe M, Mitchison TJ. Nature. 1992;359:540–543. doi: 10.1038/359540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchison T, Evans L, Schulze E, Kirschner M. Cell. 1986;45:515–527. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. Nature. 2000;407:41–47. doi: 10.1038/35024000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnani M, Ortuso F, Soro S, Alcaro S, Tramontano A, Botta M. Febs Journal. 2006;273:3301–3310. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seve P, Dumontet C. Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:73–88. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian G, Bhamidipati A, Cowan NJ, Lewis SA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:24054–24058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson HP. Journal of supramolecular structure. 1974;2:393–411. doi: 10.1002/jss.400020228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Nature. 2004;428:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, DeRosier DJ, Nicholson WV, Nogales E, Downing KH. Structure. 2002;10:1317–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amos LA, Löwe J. Chemistry & biology. 1999;6:R65–R69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)89002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downing KH, Nogales E. Current opinion in cell biology. 1998;10:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplow M, Reid R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1985;82:3267–3271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard J, Hyman AA. Nature. 2003;422:753–758. doi: 10.1038/nature01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunasekera SP, Gunasekera M, Longley RE, Schulte GK. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1990;55:4912–4915. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindel T, Jensen PR, Fenical W, Long BH, Casazza AM, Carboni J, Fairchild CR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:8744–8745. [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Pietra F. Helvetica chimica acta. 1987;70:2019–2027. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mooberry SL, Tien G, Hernandez AH, Plubrukarn A, Davidson BS. Cancer research. 1999;59:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer research. 2002;62:3356–3360. others„ et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chemistry & biology. 2012;19:686–698. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.008. others„ et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borisy GG, Taylor E. The Journal of cell biology. 1967;34:525–533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettit G, Singh S, Hamel E, Lin CM, Alberts D, Garcia-Kendal D. Experientia. 1989;45:209–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01954881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canel C, Moraes RM, Dayan FE, Ferreira D. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neuss N, Gorman M, Hargrove W, Cone NJ, Biemann K, Buchi G, Manning R. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1964;86:1440–1442. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordan MA, Thrower D, Wilson L. Cancer research. 1991;51:2212–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giannakakou P, Gussio R, Nogales E, Downing KH, Zaharevitz D, Bollbuck B, Poy G, Sackett D, Nicolaou K, Fojo T. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:2904–2909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040546297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amos LA, Löwe J. Chemistry & biology. 1999;6:R65–R69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)89002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Díaz JF, Valpuesta JM, Chacón P, Diakun G, Andreu JM. Journal of Biological Chemistry. :273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Botta M, Forli S, Magnani M, Manetti F. Tubulin-Binding Agents. In: Carlomagno T, editor. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 286. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 279–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ojima I, Chakravarty S, Inoue T, Lin S, He L, Horwitz SB, Kuduk SD, Danishefsky SJ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96:4256–4261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nettles JH, Li H, Cornett B, Krahn JM, Snyder JP, Downing KH. Science. 2004;305:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1099190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee FY, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, Kim SH, Long BH, Reventos-Suarez C, Vite GD, Rose WC, Kramer RA. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7:1429–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JG, Horwitz SB. Cancer research. 2002;62:1935–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu D, Pessino V, Kuei S, Valentine MT. Cytoskeleton. 2012;70:74–84. doi: 10.1002/cm.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prussia AJ, Yang Y, Geballe MT, Snyder JP. Chem Bio Chem. 2010;11:101–109. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodin S, Kane MP, Rubin EH. Journal of clinical oncology. 2004;22:2015–2025. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicolaou K, Roschangar F, Vourloumis D. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1998;37:2014–2045. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<2014::AID-ANIE2014>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aller SG, Yu J, Ward A, Weng Y, Chittaboina S, Zhuo R, Harrell PM, Trinh YT, Zhang Q, Urbatsch IL, Chang G. Science. 2009;323:1718–1722. doi: 10.1126/science.1168750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manetti F, Forli S, Maccari L, Corelli F, Botta M. Il Farmaco. 2003;58:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manetti F, Maccari L, Corelli F, Botta M. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2004;4:203–217. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reese M, Sánchez-Pedregal VM, Kubicek K, Meiler J, Blommers MJ, Griesinger C, Carlomagno T. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2007;46:1864–1868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Höfle G, Bedorf N, Steinmetz H, Schomburg D, Gerth K, Reichenbach H. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1996;35:1567–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balog A, Meng D, Kamenecka T, Bertinato P, Su DS, Sorensen EJ, Danishefsky SJ. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1996;35:2801–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schinzer D, Bauer A, Böhm OM, Limberg A, Cordes M. Chemistry-A European Journal. 1999;5:2483–2491. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicolaou K, He Y, Vourloumis D, Vallberg H, Yang Z. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1996;35:2399–2401. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Z, He Y, Vourloumis D, Vallberg H, Nicolaou K. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1997;36:166–168. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su DS, Balog A, Meng D, Bertinato P, Danishefsky SJ, Zheng YH, Chou TC, He L, Horwitz SB. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1997;36:2093–2096. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicolaou K, Vourloumis D, Li T, Pastor J, Winssinger N, He Y, Ninkovic S, Sarabia F, Vallberg H, Roschangar F, King NP, Finlay MRV, Giannakakou V-PPP, Hamel H. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1997;36:2097–2103. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicolaou K, Winssinger N, Pastor J, Ninkovic S, Sarabia F, He Y, Vourloumis D, Yang Z, Li T, Giannakakou P, Hamel E. Nature. 1997;387:268–272. doi: 10.1038/387268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicolaou K, Scarpelli R, Bollbuck B, Werschkun B, Pereira M, Wartmann M, Altmann K, Zaharevitz D, Gussio R, Giannakakou P. Chemistry & biology. 2000;7:593–599. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicolaou K, Pratt BA, Arseniyadis S, Wartmann M, O’Brate A, Giannakakou P. Chem Med Chem. 2006;1:41–44. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200500056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolaou K, Namoto K, Ritzén A, Ulven T, Shoji M, Li J, D’Amico G, Liotta D, French CT, Wartmann M, Altmann GP, Karl-Heinz Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:9313–9323. doi: 10.1021/ja011338b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stachel SJ, Lee CB, Spassova M, Chappell MD, Bornmann WG, Danishefsky SJ, Chou TC, Guan Y. The Journal of organic chemistry. 2001;66:4369–4378. doi: 10.1021/jo010275c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martin HJ, Pojarliev P, Kählig H, Mulzer J. Chemistry-A European Journal. 2001;7:2261–2271. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010518)7:10<2261::aid-chem2261>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.White JD, Carter RG, Sundermann KF. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1999;64:684–685. doi: 10.1021/jo982108r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su DS, Meng D, Bertinato P, Balog A, Sorensen EJ, Danishefsky SJ, Zheng YH, Chou TC, He L, Horwitz SB. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1997;36:757–759. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borzilleri RM, Zheng X, Schmidt RJ, Johnson JA, Kim SH, DiMarco JD, Fairchild CR, Gougoutas JZ, Lee FY, Long BH, Vite GD. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:8890–8897. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Altmann K-H, Pfeiffer B, Arseniyadis S, Pratt BA, Nicolaou Ke. Chem Med Chem. 2007;2:396–423. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee CB, Chou TC, Zhang XG, Wang ZG, Kuduk SD, Chappell MD, Stachel SJ, Danishefsky SJ. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2000;65:6525–6533. doi: 10.1021/jo000617z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Altmann K-H, Memmert K. Natural Compounds as Drugs. Springer; 2008. pp. 273–334. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang M, Xia X, Kim Y, Hwang D, Jansen JM, Botta M, Liotta DC, Snyder JP. Organic letters. 1999;1:43–46. doi: 10.1021/ol990521v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee KW, Briggs JM. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 2001;15:41–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1011140723828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Forli S, Manetti F, Altmann KH, Botta M. Chem Med Chem. 2010;5:35–40. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Botta M, Forli S, Magnani M, Manetti F. Tubulin-Binding Agents Topics in Current Chemistry. 2009;286:279–328. doi: 10.1007/128_2008_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.He L, Jagtap PG, Kingston DG, Shen HJ, Orr GA, Horwitz SB. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3972–3978. doi: 10.1021/bi992518p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu C, Liu X, Li Y, Shen Y. The Journal of antibiotics. 2010;63:571–574. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wartmann M, Altmann KH. Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents. 2002;2:123–148. doi: 10.2174/1568011023354489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pfeiffer B, Hauenstein K, Merz P, Gertsch J, Altmann KH. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2009;19:3760–3763. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Altmann KH, Bold G, Caravatti G, End N, Florsheimer A, Guagnano V, O’Reilly T, Wartmann M. CHIMIA International Journal for Chemistry. 2000;54:612–621. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feyen F, Gertsch J, Wartmann M, Altmann KH. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006;45:5880–5885. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Erdelyi M, Navarro-Vázquez A, Pfeiffer B, Kuzniewski CN, Felser A, Widmer T, Gertsch J, Pera B, Díaz JF, Altmann KH, Carlomagno T. Chem Med Chem. 2010;5:911–920. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhan W, Jiang Y, Sharma S, Brodie PJ, Bane S, Kingston DG, Liotta DC, Snyder JP. Chemistry-A European Journal. 2011;17:14792–14804. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen QH, Ganesh T, Brodie P, Slebodnick C, Jiang Y, Banerjee A, Bane S, Snyder JP, Kingston DG. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2008;6:4542–4552. doi: 10.1039/b814823f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhan W, Jiang Y, Brodie PJ, Kingston DG, Liotta DC, Snyder JP. Organic letters. 2008;10:1565–1568. doi: 10.1021/ol800422q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hutt OE, Inagaki J, Reddy BS, Nair SK, Reiff EA, Henri JT, Greiner JF, VanderVelde DG, Chiu TL, Amin EA, Himes RH, Georg GI. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2009;19:3293–3296. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Winkler JD, Axelsen PH. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1996;6:2963–2966. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pineda O, Farràs J, Maccari L, Manetti F, Botta M, Vilarrasa J. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2004;14:4825–4829. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rao S, Krauss NE, Heerding JM, Swindell CS, Ringel I, Orr GA, Horwitz S. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:3132–3134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Nature. 1998;391:199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Samaranayake G, Neidigh KA, Kingston DG. Journal of natural products. 1993;56:884–898. doi: 10.1021/np50096a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lowe J, Li H, Downing K, Nogales E. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zbinden P, Dobler M, Folkers G, Vedani A. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships. 1998;17:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tanrikulu Y, Schneider G. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:667–677. doi: 10.1038/nrd2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bernstein FC, Koetzle TF, Williams GJ, Meyer EF, Jr, Brice MD, Rodgers JR, Kennard O, Shimanouchi T, Tasumi M. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1978;185:584–591. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner JC. Biopolymers. 1996;38:305–320. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199603)38:3%3C305::AID-BIP4%3E3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ranaivoson FM, Gigant B, Berritt S, Joullie M, Knossow M. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2012;68:927–934. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912017143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kumar A, Heise H, Blommers MJ, Krastel P, Schmitt E, Petersen F, Jeganathan S, Mandelkow EM, Carlomagno T, Griesinger C, Baldus M. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2010;49:7504–7507. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Coderch C, Klett J, Morreale A, Díaz JF, Gago F. Chem Med Chem. 2012;7:836–843. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Taylor RE, Chen Y, Galvin GM, Pabba PK. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2004;2:127–132. doi: 10.1039/b312213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nagano S, Li H, Shimizu H, Nishida C, Ogura H, de Montellano PRO, Poulos TL. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:44886–44893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Erdélyi M, Pfeiffer B, Hauenstein K, Fohrer J, Gertsch J, Altmann KH, Carlomagno T. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2008;51:1469–1473. doi: 10.1021/jm7013452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Carlomagno T, Blommers MJ, Meiler J, Jahnke W, Schupp T, Petersen F, Schinzer D, Altmann KH, Griesinger C. Angewandte Chemie. 2003;115:2615–2619. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carlomagno T, Sánchez VM, Blommers MJ, Griesinger C. Angewandte Chemie. 2003;115:2619–2621. doi: 10.1002/anie.200350950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Entwistle RA, Rizk RS, Cheng DM, Lushington GH, Himes RH, Gupta ML. Chem Med Chem. 2012;7:1580–1586. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Prota AE, Bargsten K, Zurwerra D, Field JJ, Díaz JF, Altmann KH, Steinmetz MO. Science. 2013;339:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1230582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.ACS chemical biology. 2014 others„ et al. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rowinsky E, Eisenhauer E, Chaudhry V, Arbuck S, Donehower R. Clinical toxicities encountered with paclitaxel (Taxol) 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yared JA, Tkaczuk KH. Drug design, development and therapy. 2012;6:371. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S28997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mühlradt PF, Sasse F. Cancer research. 1997;57:3344–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mani S, McDaid H, Hamilton A, Hochster H, Cohen MB, Khabelle D, Griffin T, Lebwohl DE, Liebes L, Muggia F, Horwitz SB. Clinical cancer research. 2004;10:1289–1298. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0919-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.de Jonge M, Verweij J. Journal of clinical oncology. 2005;23:9048–9050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cheng KL, Bradley T, Budman DR. Biologics: targets & therapy. 2008;2:789. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Morales-Vasquez F, Hortobagyi GN. Breast Cancer Chemosensitivity. Springer; 2007. pp. 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Borzilleri RM, Vite GD. Drugs Future. 2002;27:1149–1163. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Katsetos DC, Draber P. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18:2778–2792. doi: 10.2174/138161212800626193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kavallaris M. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10:194–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dorff TB, Gross ME. The oncologist. 2011;16:1349–1358. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Klar U, Hoffmann J, Giurescu M. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2008;17:1735–1748. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.11.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lam ET, Goel S, Schaaf LJ, Cropp GF, Hannah AL, Zhou Y, McCracken B, Haley BI, Johnson RG, Mani S, Villalona-Calero MA. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2012;69:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1724-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ceresa C, Avan A, Giovannetti E, Geldof AA, Avan A, Cavalletti G, Peters GJ. Anticancer Research. 2014;34:517–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Campone M, Berton-Rigaud D, Joly-Lobbedez F, Baurain J-F, Rolland F, Stenzl A, Fabbro M, van Dijk M, Pinkert J, Schmelter T, de Bont PP, Natasja The oncologist. 2013;18:1190–1191. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hunt JT. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:275–281. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.FDA. [Accessd: 2014-02-01];Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products - Ixabepilone. 2007 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Set_Current_Drug&ApplNo=022065&DrugName=IXEMPRA%20KIT&ActiveIngred=IXABEPILONE&SponsorApplicant=BRISTOL%20MYERS%20SQUIBB&ProductMktStatus=1&goto=Search. DrugDetails.

- 128.Sanner MF. J Mol Graph Model. 1999;17:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]