Abstract

Background

International travel continues to increase, particularly to Asia and Africa. Clinicians are increasingly likely to be consulted for advice before travel or by ill returned travelers.

Objective

To describe typical diseases in returned travelers according to region, travel reason, and patient demographic characteristics; describe the pattern of low-frequency travel-associated diseases; and refine key messages for care before and after travel.

Design

Descriptive, using GeoSentinel records.

Setting

53 tropical or travel disease units in 24 countries.

Patients

42 173 ill returned travelers seen between 2007 and 2011.

Measurements

Frequencies of demographic characteristics, regions visited, and illnesses reported.

Results

Asia (32.6%) and sub-Saharan Africa (26.7%) were the most common regions where illnesses were acquired. Three quarters of travel-related illness was due to gastrointestinal (34.0%), febrile (23.3%), and dermatologic (19.5%) diseases. Only 40.5% of all ill travelers reported pretravel medical visits. The relative frequency of many diseases varied with both travel destination and reason for travel, with travelers visiting friends and relatives in their country of origin having both a disproportionately high burden of serious febrile illness and very low rates of advice before travel (18.3%). Life-threatening diseases, such as Plasmodium falciparum malaria, melioidosis, and African trypanosomiasis, were reported.

Limitations

Sentinel surveillance data collected by specialist clinics do not reflect healthy returning travelers or those with mild or self-limited illness. Data cannot be used to infer quantitative risk for illness.

Conclusion

Many illnesses may have been preventable with appropriate advice, chemoprophylaxis, or vaccination. Clinicians can use these 5-year GeoSentinel data to help tailor more efficient pretravel preparation strategies and evaluate possible differential diagnoses of ill returned travelers according to destination and reason for travel.

Primary Funding Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

International travel has increased by 50% over the past decade, with 983 million tourist arrivals in 2011 (1). Long-distance travel, especially to countries with emerging economies in Asia and Africa, has increased disproportionately (1). Travel frequency is also increasing for persons with comorbid conditions, those traveling for business, or those visiting friends and relatives (2). Travelers visiting friends and relatives, defined as immigrants and their spouses or descendants traveling to their country or region of origin, are emerging as a group at substantial risk for travel illness (3, 4). Health practitioners are increasingly likely to be consulted by persons seeking advice before travel or who are ill after travel and should be aware of variations in the likelihood of particular familiar and unfamiliar illnesses according to traveler and itinerary characteristics (5).

GeoSentinel (www.geosentinel.org), with 53 clinical sites in 24 countries, hosts the largest available database of diseases reported in international travelers and immigrants, with more than 170 000 patient records collected since its founding in 1995 by the International Society of Travel Medicine and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

We present results from analysis of the most recent GeoSentinel data (2007 to 2011), highlighting key diagnostic messages for practitioners about common and low-frequency imported diseases according to region, travel reason, and patient demographic characteristics to refine important messages for care before and after travel.

Methods

GeoSentinel sites are specialized travel or tropical medicine clinics that have demonstrated training, experience, or significant publication in travel or tropical medicine. Sites contribute clinician-based sentinel surveillance on all patients seen during routine clinical care for a presumed travel-related illness. The 53 clinical sites are located in 24 countries (21 sites in North America, 17 in Europe, 10 in Australasia, 3 in Latin America, and 1 each in Southern Africa and the Middle East). Most sites are located in academic health centers; sites may be administratively independent or operate within broader infectious disease or community health services. Some sites provide pretravel care at the same location and some provide only outpatient care.

Anonymized patient data gathered during routine patient care are entered at each site directly into a Structured Query Language database. Standardized data collection forms capture patient demographic characteristics, detailed recent travel itinerary, list of countries visited within 5 years, reason for recent travel, symptom-based grouping by affected organ system, and presence or absence of a reported encounter with a health care provider before travel. Final diagnoses are coded by the attending physician from a list of 522 defined GeoSentinel diagnosis codes. Diagnoses involve syndromic groupings plus specific causes where possible and syndromic groupings only where no specific cause is defined. Specific diagnoses are made using the best available laboratory tests, according to national standard clinical practice in the site country. Country or region of acquisition is based on itinerary, patterns of disease endemicity, and incubation periods and is assigned only when ascertainable.

GeoSentinel's data collection protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board officer at the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the CDC and classified as public health surveillance and not as human subjects research requiring submission to institutional review boards.

This study includes travelers seen at GeoSentinel sites from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2011. We included only travelers who presented in their country of residence after return from travel and were diagnosed with 1 or more travel-related diseases. We excluded those whose only travel was for immigration and those whose final diagnosis was considered to be unrelated to travel. Data were analyzed in Access 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington); frequencies of demographic, diagnosis, and travel-related variables were determined.

Role of Funding Source

GeoSentinel Surveillance Network is funded through a cooperative agreement with the CDC and by the International Society of Travel Medicine. GeoSentinel has an independent Data Use and Publication Committee that oversees analyses of the database from concept sheet to final manuscript and comprises 5 site directors outside of the CDC. Staff from the CDC was involved in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and writing of the report. The final manuscript also had CDC internal clearance.

Results

There were 42 173 ill returned travelers with 49 379 diagnoses reported during the 5-year period. The largest proportion of travelers acquired their illness in Asia (32.6%), followed by sub-Saharan Africa (26.7%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (19.2%). North Africa and the Middle East; Europe; North America; and Oceania, Australia, and New Zealand accounted for the remainder (the region of illness acquisition was not ascertainable for 7.8% of patients) (Table 1). Overall, 40.5% of ill returned travelers reported a visit with a health professional for advice before travel, but this varied by destination region, travel reason, and diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Ill Returned Travelers

| Variable | Total | Gastrointestinal Diagnoses |

Febrile Illness |

Dermatologic Diagnoses |

Respiratory or Pharyngeal Diagnoses |

Neurologic Diagnoses |

GU, STI, and Gynecologic Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travelers, n (%) | 42 173 | 14 346 (34.0) | 9817 (23.3) | 8227(19.5) | 4613 (10.9) | 724 (1.7) | 1209 (2.9) |

| Diagnoses, n * | 49 379 | 14 837 | 10 092 | 9669 | 4851 | 738 | 1260 |

| Men, % † | 49.9 | 44.5 | 58.9 | 47.8 | 51.7 | 50.6 | 37.2 |

| Median age (range), y ‡ | 34 (0–95) | 32 (0–92) | 35 (0–91) | 35 (0–95) | 36 (0–93) | 38 (0–88) | 37 (0–88) |

| Travel reason, % § | |||||||

| Tourism | 55.7 | 59.3 | 45.1 | 68.2 | 53.6 | 55.4 | 51.9 |

| Business | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 9.5 | 17.0 | 12.8 | 13.9 |

| Visiting friends/relatives | 15.5 | 8.8 | 28.1 | 10.2 | 16.5 | 13.5 | 18.5 |

| Missionary | 11.6 | 13.9 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 9.2 | 13.5 | 13.1 |

| Student | 2.6 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| Region, % ∥ | |||||||

| Australia and New Zealand | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Southeast Asia | 16.3 | 13.8 | 18.1 | 22.0 | 17.4 | 10.1 | 17.3 |

| South-Central Asia | 13.6 | 19.1 | 13.2 | 9.1 | 10.6 | 7.6 | 11.1 |

| Northeast Asia | 2.7 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Europe | 4.7 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 7.4 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 19.2 | 20.4 | 14.3 | 27.3 | 14.2 | 23.6 | 15.6 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 6.1 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 6.5 | 6.1 |

| North America | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| Oceania | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 26.7 | 22.5 | 42.6 | 19.5 | 20.6 | 22.3 | 26.9 |

GU = genitourinary; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Some travelers had >1 diagnosis. Other diagnoses (adverse events to medication or vaccine, injury or musculoskeletal problems, opthalmologic or oral conditions, and psychological problems) are not shown (7932 diagnoses).

Data were missing in 36 cases (0.09%).

Data were missing in 143 cases (0.3%).

Data were missing in 22 cases (0.05%), and alternate reason (military or medical tourism) accounted for 1%.

Region of illness acquisition not ascertainable in 3299 cases (7.8%).

Table 2.

Proportion of the 42 173 Ill Returned Travelers Reporting a Pretravel Visit

| Variable | Reported Pretravel Visit, % |

|---|---|

| Total * | 40.5 |

| Region | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 51.7 |

| Asia | 41.2 |

| Oceania | 39.5 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 37.2 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 28.3 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 23.2 |

| Europe | 11.5 |

| North America | 10.9 |

| Reason for travel | |

| Tourism | 41.0 |

| Business | 42.7 |

| Visiting friends/relatives | 18.3 |

| Missionary, volunteers, and researchers | 59.0 |

| Students | 60.2 |

| Other | |

| Military | 78.2 |

| Medical tourism | 36.7 |

| Diagnostic category | |

| Gastrointestinal diagnoses | 46.4 |

| Febrile illness | 38.6 |

| Dermatologic diagnoses | 39.9 |

| Respiratory and pharyngeal diagnoses | 34.6 |

| Neurologic diagnoses | 36.3 |

| GU, STI, and gynecologic diagnoses | 39.4 |

| Deaths | 17.9 |

GU = genitourinary; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

* No pretravel visit was reported in 32.9% and was recorded as unknown in 14.8%; data were missing in 11.8%.

Gastrointestinal Infections

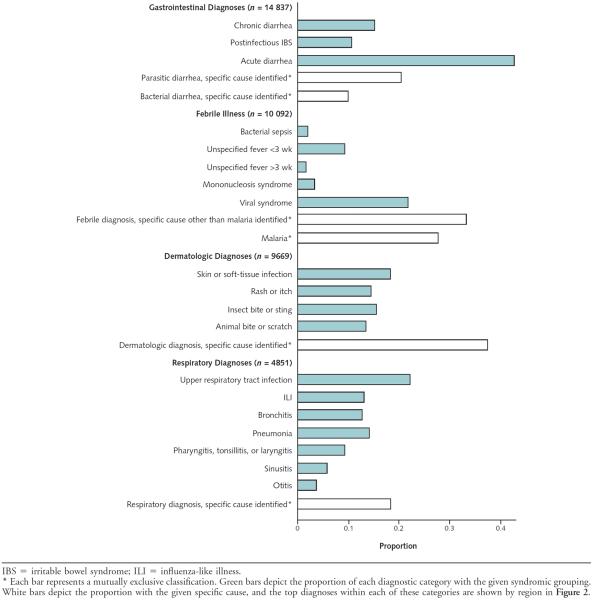

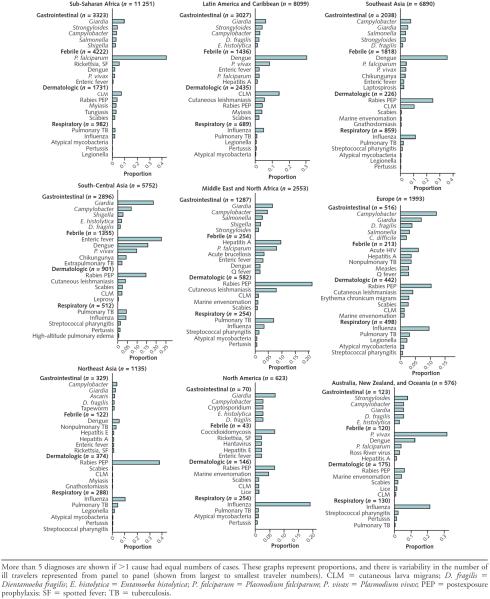

Gastrointestinal infections were the most common illnesses reported (34.0% of all travelers) (Table 1). More than 40% of travelers with gastrointestinal illness had an acute diarrheal syndrome and an additional 20% and 10% had specific parasitic and bacterial causes, respectively (Figure 1). The most commonly diagnosed bacterial gastrointestinal infections were Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella species; these infections were especially implicated among travelers returning from Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa (Figure 2). The most common parasite was Giardia, which was proportionately most common among people who had visited South-Central Asia (India and neighboring countries). More than 40% of persons with prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms after travel (lasting >2 weeks; shown as chronic diarrhea or postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome in Figure 1) had postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome.

Figure 1.

Proportion of major syndromic groupings for gastrointestinal, febrile, dermatologic, and respiratory illnesses among ill returned travelers.

Figure 2.

Top identified specific causes for gastrointestinal, febrile, dermatologic, and respiratory illnesses by region among ill returned travelers.

Febrile Illness

Febrile illness was reported in 23.3% of all travelers (Table 1). Malaria, diagnosed in 29% of those with fever and disproportionately in travelers returning from Africa, was the most common specific diagnosis, followed by dengue (15%), which was predominantly found in travelers returning from Southeast Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 2). Other notable specific causes of fever included enteric fever (typhoid and paratyphoid), chikungunya fever, rickettsial diseases, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis, tuberculosis, and acute HIV (Figure 2 and Table 3), with the proportional contribution varying by region. For example, enteric fever was most common after travel to South-Central Asia, whereas spotted fever rickettsiosis was diagnosed in 6% of travelers returning from sub-Saharan Africa (notably South Africa) with a febrile illness. Even at our specialized sites, nearly 40% of travelers diagnosed with a febrile syndrome had no specific cause identified (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Notable Specific Diagnoses Among Ill Returned Travelers

| Diagnoses | Cases, n | Median Age, y |

Man– Woman Ratio |

Reason for Travel, %* |

Reported Pretravel Visit, % |

Top Countries of Exposure† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism | Visiting Friends/ Relatives |

Business | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||||

| Giardia | 1426 | 31 | 0.9 | 59.2 | 6.8 | 14.3 | 53.9 | India, Thailand, Nepal, and Ghana |

| Campylobacter | 753 | 29 | 1.2 | 68.5 | 7.2 | 11.7 | 53.3 | India, Thailand, Indonesia, and Tanzania |

| Strongyloides | 483 | 40 | 1.1 | 28.6 | 40.6 | 9.9 | 37.1 | India, Vietnam, Ghana, and Dominican Republic |

| Salmonella enteritis | 367 | 31 | 1.0 | 62.7 | 11.7 | 13.6 | 47.4 | Thailand, India, Indonesia, and Egypt |

| Shigella | 271 | 34 | 0.9 | 62.3 | 8.9 | 18.5 | 51.3 | India, Egypt, Ghana, and Indonesia |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 340 | 38 | 1.3 | 50.9 | 10.9 | 17.1 | 41.5 | India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Thailand |

| Vibrio | 9 (cholera: 2, noncholera: 7) | 33 | 0.3 | 77.8 | 22.2 | - | 11.1 | 5 cases in Latin America (2 cases acquired in Mexico), 3 in Asia, 1 in sub-Saharan Africa |

| Anisakiasis | 1 | 56 | 1 woman | - | - | 100 | 100 | Senegal |

| Shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli | 1 | 40 | 1 man | 100 | - | - | 0 | Germany (May 2011) |

| Febrile | ||||||||

| Malaria | 2820 | |||||||

| Plasmodium falciparum | 1990 | 38 | 2.0 | 12.1 | 62.1 | 14.9 | 27.4 | Ghana, Comoros, Nigeria, and Côte d'Ivoire |

| Plasmodium vivax | 480 | 30 | 3.0 | 25.0 | 32.5 | 14.4 | 43.3 | India, French Guyana, Myanmar, and Papua New Guinea |

| Plasmodium knowlesi | 2 | 29.5 | 2 men | - | - | 50.0 | 0 | Both acquired in Asia (1 in Malaysia and 1 in an unspecified Asian country) |

| Dengue | 1473 | 34 | 1.1 | 61.6 | 15.3 | 11.5 | 36.9 | Thailand, Indonesia, India, and Brazil |

| Enteric fever | 467 | 28 | 1.3 | 43.0 | 39.8 | 7.7 | 30.5 | India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh |

| Spotted fever rickettsia | 267 | 48 | 1.3 | 84.2 | 1.5 | 9.0 | 44.6 | South Africa (68.9%), Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Swaziland |

| Chikungunya | 164 | 41 | 0.8 | 53.0 | 21.3 | 17.1 | 29.9 | India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand |

| Hepatitis A | 120 | 30 | 1.3 | 48.3 | 32.5 | 10.8 | 18.3 | India, Morocco, Egypt, and Mexico |

| Acute HIV | 84 | 40 | 4.3 | 52.4 | 23.8 | 15.5 | 20.2 | Thailand, Brazil, Guinea, and Germany |

| Leptospirosis | 83 | 32 | 4.2 | 78.3 | 6.0 | 9.6 | 38.6 | Thailand, Laos, and Costa Rica |

| Hepatitis E | 45 | 38 | 2.0 | 51.1 | 31.1 | 11.1 | 28.9 | India (40%), Pakistan, and Bangladesh |

| Brucellosis, acute | 33 | 39 | 1.4 | 27.3 | 45.5 | 6.1 | 39.4 | India, Sudan, and Iraq |

| Measles | 33 | 34 | 2.7 | 54.5 | 24.2 | 12.1 | 24.2 | India, Thailand, and France |

| Histoplasmosis | 23 | 35 | 1.9 | 69.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 26.1 | Guatemala and Costa Rica |

| Rickettsia typhi (flea-borne) | 17 | 23 | 1.8 | 47.1 | 23.5 | 11.8 | 23.5 | Cambodia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Nepal |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | 16 | 30 | 2.2 | 56.3 | 31.3 | - | 31.3 | India, Greece, Portugal, and Spain |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi (scrub typhus) | 14 | 38.5 | 2.5 | 71.4 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 21.4 | Thailand and Vietnam |

| Rubella | 11 | 33 | 4.5 | 54.5 | 27.3 | 18.2 | 9.1 | Vietnam and Thailand |

| Melioidosis | 9 | 37 | 3.5 | 44.4 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 11.1 | Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia |

| Mumps | 8 | 43.5 | 0.6 | 62.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 37.5 | Different country for each case (2 in Western Europe, 4 in sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in Latin America, and 1 in Asia) |

| African trypanosomiasis | 6 | |||||||

| Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | 5 | 49 | 0.7 | 60.0 | - | 20.0 | 20 | Zambia (3 cases), Tanzania, and Zimbabwe |

| Trypanosoma brucei gambiense | 1 | 20 | 1 woman | - | 0 | Burkina Faso | ||

| Relapsing fever | 6 | 33.5 | 2.0 | 50.0 | - | 16.7 | 66.7 | Senegal, South Africa, and Morocco |

| Ross River virus | 5 | 32 | 0.7 | 80.0 | - | 20.0 | 0 | Australia |

| Coccidioidomycosis | 3 | 62 | 2.0 | 66.7 | - | 33.3 | 33.3 | United States (2 cases acquired in Arizona) |

| Babesiosis | 2 | 63.5 | 2 women | 100 | 50.0 | United States and Caribbean (country unknown) | ||

| Blastomycosis | 1 | 31 | 1 man | 100 | - | - | 0 | Peru |

| Chagas, acute | 1 | 26 | 1 woman | 100 | - | - | 0 | Mexico |

| Ehrlichiosis | 1 | 32 | 1 woman | 100 | - | - | 100 | Unknown |

| Hantavirus | 1 | 43 | 1 man | 100 | - | - | 0 | Canada |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | 1 | 35 | 1 man | - | 100 | - | 100 | Mexico |

| Rift Valley fever | 1 | 21 | 1 woman | 100 | - | - | 100 | Kenya |

| Tularemia | 1 | 57 | 1 man | 100 | - | - | 0 | France |

| Dermatologic | ||||||||

| Rabies PEP after bite or scratch | 1249 | 31 | 1.0 | 68.9 | 17.7 | 7.1 | 25.5 | Thailand, Indonesia, China, and India |

| Cutaneous larva migrans | 806 | 30 | 0.9 | 80.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 42.1 | Thailand, Brazil, Mexico, and Malaysia |

| Leishmaniasis (cutaneous or mucocutaneous) | 264 | 23 | 1.9 | 49.6 | 17.0 | 7.2 | 49.6 | Bolivia, Afghanistan, and Costa Rica |

| Myiasis | 174 | 36 | 1.3 | 71.8 | 6.3 | 11.5 | 46.9 | Senegal, Brazil, Costa Rica, and Belize |

| Tungiasis | 87 | 30 | 1.1 | 52.9 | 5.7 | 10.3 | 54.0 | Brazil, Madagascar, Uganda, and Ethiopia |

| Gnathostomiasis | 12 | 26.1 | 1 | 50.0 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 33.3 | Cambodia and Indonesia (92% from Asia) |

| Leprosy | 11 | 44 | 4.5 | 90.9 | - | 9.1 | 18.2 | Pakistan and Vietnam |

| Cutaneous atypical mycobacteria | 6 | 36.5 | 2.0 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 16.7 | 16.7 | All different (Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and South-Central Asia) |

| Sporotrichosis | 1 | 14 | 1 woman | - | 100 | - | 0 | Mexico |

| Yaws | 1 | 67 | 1 woman | - | 100 | - | 0 | Jamaica |

| Respiratory or pharyngeal | ||||||||

| Influenza | 367 | |||||||

| H1N1 | 176 | 16 | 1.2 | 59.7 | 10.2 | 19.9 | 37.5 | United States, Australia, United Kingdom, and Philippines |

| Influenza A or B | 191 | 36 | 1.1 | 59.7 | 10.5 | 22.0 | 9.1 | Indonesia, Thailand, India, and China |

| TB | 170 | |||||||

| MDR or XDR pulmonary TB | 3 | 35 | 0.5 | - | 100 | - | 66.7 | 1 case each for Nigeria and India (1 case unknown) |

| Legionellosis | 35 | 59 | 1.9 | 74.3 | 5.7 | 17.1 | 17.1 | China, Italy, and Spain |

| Pulmonary atypical mycobacteria | 35 | 62 | 0.7 | 54.3 | 28.6 | 11.4 | 8.6 | China, Thailand, Kenya, South Africa, and North America |

| Pertussis | 30 | 42 | 0.8 | 60.0 | 6.7 | 26.7 | 33.3 | India and China |

| Diphtheria | 2 | 20.5 | 1.0 | - | 100 | - | 0 | Latvia |

| Neurologic | ||||||||

| Ciguatera intoxication | 51 | 41 | 0.7 | 78.4 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 13.7 | Bahamas and Dominican Republic |

| Neurocysticercosis | 21 | 34 | 1.3 | 47.6 | 14.3 | 23.8 | 28.6 | India |

| TB meningitis or tuberculoma | 13 | 40 | 1.2 | 15.4 | 61.5 | 7.7 | 7.7 | India and Pakistan |

| Scombroid, neurotoxic or paralytic shellfish poisoning | 7 | 38 | 0.4 | 85.7 | - | - | 50 | Mauritius (2 cases) and other (2 cases in Western Europe and 2 cases in Southeast Asia) |

| West Nile virus | 5 | 53 | 1.5 | 60.0 | 20.0 | - | 0 | 1 case each in Afghanistan, Costa Rica, Greece, and Israel (1 unknown) |

| Angiostrongylus | 4 | 25 | 0.3 | 25.0 | - | - | 25 | 1 case each in Fiji, Philippines, Jamaica, and Panama |

| Botulism | 3 | 15 | 3 men | 100 | 0 | 2 cases in Argentina and 1 in United States | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis | 3 | 33 | 2.0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | - | 0 | 1 case each from Estonia and Sweden (1 case unknown) |

| Japanese encephalitis | 2 | 25.5 | 2 women | 50.0 | - | - | 50 | 1 case each from Cambodia and Thailand |

| Other | ||||||||

| Schistosomiasis | 792 | 32 | 1.4 | 36.1 | 17.6 | 10.2 | 58.7 | Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania, and Ghana |

| Filariasis (loiasis, onchocerciasis, Wuchereria bancrofti, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, and other or unknown species) | 113 | 41 | 1.1 | 20.4 | 33.6 | 8.8 | 30.1 | Cameroon, Gabon, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Central African Republic |

| Lyme disease | 77 | 40 | 0.5 | 71.4 | 11.7 | 13.0 | 19.5 | United States, Germany, and Italy |

| Visceral larva migrans | 16 | 38 | 1 | 62.5 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 31.3 | 6 cases in Southeast Asia (2 cases acquired in Thailand), 5 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 3 in sub-Saharan Africa, and 2 cases unknown |

| Fasciola | 14 | 43 | 0.6 | 57.1 | 14.3 | 7.1 | 28.6 | Australia, Germany, France, and the Netherlands |

| Clonorchis | 12 | 39.5 | 0.3 | 16.7 | 58.3 | 16.7 | 16.7 | Thailand, Laos, and China |

| Trichinellosis | 12 | 48 | 1.4 | 25 | 41.7 | - | 25.0 | Poland and Serbia |

MDR = multidrug-resistant; PEP = postexposure prophylaxis; TB = tuberculosis; XDR = extensively drug-resistant.

Reasons for travel included tourism (55.7%), visiting friends/relatives (15.5%), and business (13.6%). Students, missionaries and volunteers, medical tourism, and military service are not shown.

Countries reporting the most cases (or regions if countries were not specified) for each diagnosis.

Dermatologic Diagnoses

Dermatologic problems were reported in 19.5% of all travelers (Table 1). Animal bites or scratches or insect bites or stings, skin or soft-tissue infections, and rash or itch were most common (Figure 1). Specific dermatologic diagnoses by region are shown in Figure 2. More than 12% of all specific dermatologic presentations required rabies postexposure prophylaxis, and over 8% of all skin problems were due to cutaneous larva migrans, which was especially common among travelers returning from Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean.

Respiratory Illness

Upper and lower respiratory diagnoses were reported in 10.9% of all travelers (Table 1). Most respiratory illnesses were due to infections with a worldwide distribution, including nonspecific upper respiratory infections, influenza or influenza-like illness, bronchitis, and pneumonia (lobar and atypical) (Figure 1). Influenza A, B, or H1N1 was diagnosed in 8% of travelers with a respiratory illness. There were 35 cases of legionellosis.

Other Illnesses

Specific neurologic diagnoses were uncommon (1.7% of all travelers) but included some exotic and potentially life-threatening infections (Table 3). There were 132 cases of meningoencephalitis identified, mostly nonspecified, with 5 due to West Nile virus infection. Fifty-one cases of ciguatera intoxication, which causes a neurologic syndrome of paresthesia, nerve palsy, and hot or cold temperature reversal that can persist for several weeks, were identified (6). GeoSentinel sites typically specialize in tropical rather than sexually transmitted infections, so genitourinary infections and sexually transmitted infections were not commonly seen (2.9%). Over 8% of travelers had other travel-related diagnoses, including adverse reactions to medication or vaccine, injury or musculoskeletal problems, opthalmologic or oral conditions, and psychological problems (not further discussed).

Vaccine-Preventable Illnesses

Vaccine-preventable diseases were reported in 737 travelers, of whom only 19.7% had a health care encounter before travel. These included 367 cases of influenza (15.8% had had a pretravel visit), 161 cases of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (pretravel visit in 26.1%), 120 cases of hepatitis A (pretravel visit in 18.3%), 3 cases of tick-borne encephalitis (no pretravel visits), 2 cases of Japanese encephalitis (1 with pretravel visit), and 84 cases of childhood vaccine-preventable diseases (33 cases of measles, 30 cases of pertussis, 11 cases of rubella, 8 cases of mumps, and 2 cases of diphtheria [pretravel visit in 28.6%]).

Low-Frequency Illnesses

Low-frequency illnesses (<20 cases), some potentially serious, were reported (Table 3), including visceral leishmaniasis, scrub typhus, relapsing fever, angiostrongyliasis, botulism, melioidosis, tularemia, hantavirus infection, and Plasmodium knowlesi. We also saw East African sleeping sickness after travel to Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. No cases of yellow fever, Ebola virus, Lassa fever, Marburg virus, tetanus, polio, anthrax, or plague were reported, attesting to the rarity of these high-profile diseases in travelers. No cases of rabies were reported during the 5-year period; however, 2 cases were reported to GeoSentinel in 2006 and 2012 (data not shown).

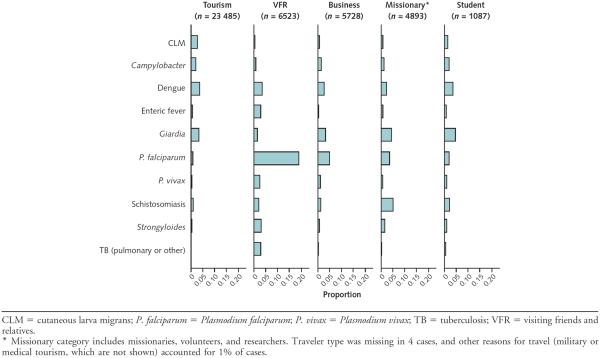

Illness by Reason for Travel and Region of Acquisition

Diagnoses varied according to reason for travel. For example, although 15.5% of ill returned travelers were visiting friends and relatives, 62.1% of P. falciparum malaria cases occurred among these travelers (Table 3) and nearly 20% of these travelers presented with P. falciparum (Figure 3). Enteric fever and Strongyloides species infections were also diagnosed disproportionately in travelers who visited friends and relatives, cutaneous larva migrans occurred predominantly in tourists, and schistosomiasis was most common among missionaries or volunteers (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Top 10 specific diagnoses, by main reasons for travel.

Illnesses were also reported in travelers to economically developed and temperate regions. One third of travel-related Legionella species infections were acquired in Europe, as were approximately 20% of measles and 15% of acute HIV cases. Europe was the destination for some travelers diagnosed with hepatitis A (8 cases), trichinellosis (7 cases), and vector-borne infections (5 visceral leishmaniasis cases, mainly from Spain, Portugal, and Greece; 18 cutaneous leishmaniasis cases, mainly from Spain, Malta, and Italy; 5 cases of spotted fever rickettsiosis from Spain, France, and Greece; and 27 cases of Lyme borreliosis, mainly from Germany and Italy). Lyme borreliosis (23 cases), coccidioidomycosis (3 cases), and babesiosis (1 case) were reported in travelers to the United States. Four travelers acquired Ross River virus in Australia.

Deaths

Overall, 28 deaths were reported, one quarter of which was due to P. falciparum malaria (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographic and Travel Characteristics of 28 Recorded Deaths Among Travelers

| Age, y | Sex | Traveler Type | Diagnosis | Region (Country) | Pretravel Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | Male | Visiting friends/relatives | Plasmodium falciparum | Sub-Saharan Africa (Ghana) | No |

| 66 | Male | Business | Plasmodium falciparum | Sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso) | No |

| 57 | Male | Missionary or volunteer | Plasmodium falciparum | Sub-Saharan Africa (Liberia) | Unknown |

| 49 | Male | Tourism | Plasmodium falciparum, acute renal failure | Southeast Asia (Indonesia) | No |

| 30 | Female | Business | Plasmodium falciparum | Sub-Saharan Africa (Equatorial Guinea) | Yes |

| 30 | Male | Business | Plasmodium falciparum | Unknown | Yes |

| 53 | Female | Tourism | Dengue | Southeast Asia (Thailand) | No |

| 24 | Female | Business | Dengue, Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi | Southeast Asia (Indonesia) | No |

| 42 | Male | Tourism | Dengue, Orientia tsutsugamushi, AIDS, CMV | Southeast Asia (Thailand) | Yes |

| 59 | Female | Visiting friends/relatives | Strongyloides hyperinfection, HTLV-1 or HTLV-2, bacterial meningitis | Caribbean (Haiti) | Unknown |

| 57 | Male | Business | Melioidosis | Southeast Asia (Thailand) | Yes |

| 35 | Male | Tourism | Melioidosis | Caribbean (Martinique) | Unknown |

| 34 | Female | Tourism | Sepsis, Clostridium difficile diarrhea | Caribbean (Cuba) | Unknown |

| 55 | Male | Tourism | Acute Salmonella diarrhea, sepsis | Caribbean (Puerto Rico) | Unknown |

| 26 | Female | Student | Influenza A, myocarditis | Northeast Asia (Taiwan) | Unknown |

| 84 | Female | Tourism | Lobar pneumonia, ARDS, sepsis | Western Europe (Spain) | No |

| 82 | Male | Business | Lobar pneumonia | South-Central Asia (India) | No |

| 86 | Male | Tourism | Lobar pneumonia, COPD, Parkinson disease | Western Europe (Spain) | Unknown |

| 53 | Male | Business | Atypical pneumonia, AIDS | Southeast Asia (Vietnam) | No |

| 40 | Male | Tourism | AIDS, pleural effusion, cancer | Southeast Asia (country not ascertainable) | No |

| 49 | Female | Tourism | Lobar pneumonia, acute renal failure | Middle East (Saudi Arabia) | Yes |

| 65 | Male | Tourism | Legionnaire disease, acute renal failure | Eastern Europe (Prague) | Unknown |

| 83 | Male | Tourism | Sepsis, atypical pneumonia | Northeast Asia (China) | No |

| 35 | Male | Tourism | Endocarditis | Northeast Asia (China) | Unknown |

| 78 | Female | Tourism | Acute urinary tract infection, sepsis | Western Europe (Spain) | No |

| 67 | Male | Tourism | Pyelonephritis, sepsis | Western Europe (Spain) | No |

| 5 | Female | Tourism | Sepsis, hematologic cancer | South-Central Asia (India) | No |

| 29 | Female | Tourism | Encephalitis (unknown cause) | Southeast Asia (country not ascertainable) | Unknown |

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CMV = cytomegalovirus; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HTLV = human T-lymphotropic virus.

Discussion

We present data captured by a global surveillance network about travel-associated illness that reflect the changing regional travel patterns. The nature of GeoSentinel and the unique size of our traveler sample have enabled diagnostic patterns for travel illnesses to be presented by region and reason and also allow description of patterns of low-frequency travel-associated diseases that are unfamiliar to many nonspecialists. The results highlight that the overall proportion of travelers reporting a visit with a health care professional before travel (even among those traveling to perceived risky destinations, such as Sub-Saharan Africa) remains suboptimal.

Overall, approximately 75% of illness in returned travelers is caused by gastrointestinal, febrile, and dermatologic disease (7–12). For travelers with a gastrointestinal syndrome, regional variations existed, but overall, Campylobacter species was the most common specific bacterial pathogen detected. Increasing quinolone resistance worldwide may have implications for the frequent use of these antibiotics for empirical therapy for acute travelers' diarrhea (13, 14). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, the most common overall cause of acute diarrhea as defined in prospective studies (15–17), is captured by GeoSentinel as acute diarrhea with no cause because this diagnosis requires specialized testing that is not used in routine clinical practice. Travel-related postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, which often results in extensive investigation and several clinic visits, is an increasingly recognized but inconsistently defined entity that accounted for nearly one half of travelers presenting with nonspecific chronic diarrhea (18–21). Given the frequency and duration of gastrointestinal illness in travelers, provision of preventive advice about food- and water-borne risks is strongly recommended (22).

Plasmodium falciparum malaria remains the most clinically important febrile illness (23–28) and must be considered in all travelers returning with fever from areas with potential malaria transmission. However, whereas P. falciparum malaria was the most common cause of fever among travelers returning from sub-Saharan Africa, dengue was more frequently the cause of fever among travelers returning from Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia (Figure 2). Viremic travelers can introduce dengue into new areas (29), and local transmission of dengue in such non-endemic areas as the United States (Texas and Florida) (30, 31) and Europe (32, 33) has occurred. Chikungunya virus, which can clinically resemble dengue, causes fever and occasionally intractable arthralgia and is a reemerging infection reported mainly in travelers returning from South-Central or Southeast Asia (34).

For enteric fever, management of cases is complicated by the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant isolates (35). Available vaccines are at best 70% effective against S. enterica serotype Typhi and do not adequately prevent S. enterica serotype Paratyphi, but nevertheless should be considered, particularly for travelers to South-Central Asia. Other clinically important causes of fever include acute HIV, acute hepatitis A and E, and leptospirosis. Among travelers returning from sub-Saharan Africa with a febrile illness, spotted fever rickettsiosis due to Rickettsia africae was a common cause, highlighting that a complete physical examination is needed to detect a necrotic eschar at the site of the tick bite (36). Fever with or without rash occurring soon after a safari trip to East Africa should lead to a prompt blood film for Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense to facilitate rapid diagnosis and reduce the risks for neuroinvasion and death (37, 38). Early referral of severely ill returned travelers to a clinician experienced in travel and tropical medicine may help mitigate the potential severe sequelae of these infections.

The profile of dermatologic problems is similar to that described in other studies (5, 7, 39–44). Clinicians should be educated to recognize the pathognomonic serpiginous lesions of hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans, which respond to therapy with ivermectin or albendazole (45). Animal bites or scratches (mainly from dogs or monkeys) requiring rabies postexposure prophylaxis were common, especially in tourists returning from Asia. Indonesia has been identified as a particular area of recent risk (46). Leishmaniasis, transmitted by sandflies in many tropical countries and southern Europe, was the most frequent cause of cutaneous ulcer in our study (47). The lesions are typically painless with a clean base and rolled-up edges surrounding the crater, and misdiagnosis is common.

Although the largest proportion of ill travelers had returned from Asia, Africa, or Latin America, our data highlight important illness encountered in travelers to developed countries in Europe; North America; and Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania. Vector-borne diseases in travelers to Europe, which mirror an overall increase in arthropod-borne diseases in Europe (48), are particularly notable, as are the cases of measles (49) and legionellosis (50). Travelers to western countries often consider their risk for disease to be low, as do health care professionals.

In addition to low proportions of travelers reporting a visit with a health care professional before travel, our data suggest that outcomes can be suboptimal, with vaccine-preventable diseases occurring even among those who reported a pretravel visit. For example, nearly 20% of travel-related hepatitis A infections occurred in patients with a pretravel encounter before travel. Because even a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine provides nearly 100% protection against infection (51), this may indicate a gap in staff knowledge or patient acceptance of recommendations. Influenza, the most common illness among those who had received advice before travel, is transmitted year-round in the tropics, October to March in the northern hemisphere, and May to September in the temperate southern hemisphere. Our data support current CDC recommendations to consider vaccination if traveling to a region where influenza transmission is occurring (52, 53). Cases of childhood vaccine-preventable diseases emphasize the importance of updating routine immunizations before travel according to national or international travel health guidelines (54–56). For non–vaccine-preventable diseases, the pretravel visit offers the opportunity for relevant education. For example, optimal personal protective measures against arthropod bites may help prevent vector-borne diseases. Such measures include skin repellents containing DEET (diethyltoluamide) or picaridin; permethrin-impregnated clothing (57); and for the night-biting vectors of Anopheles malaria, bed nets and screened or air-conditioned sleeping quarters (58).

The disproportionate burden of serious febrile illnesses, such as malaria and enteric fever, among travelers who visited friends and relatives juxtaposed with the low rates of advice before travel in this population represents a health disparity, highlighting the need for more effective delivery of preventive advice to this high-risk group (3, 4, 59, 60). Travelers who visited friends and relatives often adopt local health-related behaviors during their trip, and some who have emigrated from resource-poor countries may not have had routine vaccinations (61). Aversion to consultation and intervention costs as well as inadequate appreciation of potential travel risks are common obstacles to seeking preventive care. Proactive strategies by primary care clinicians are needed, such as routinely questioning immigrant patients about future travel plans and advising them of the importance of seeking care before travel when they visit for other reasons (62). Along with acute illnesses associated with recent travel, tuberculosis, strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis, filariasis, cysticercosis, and leprosy were also commonly diagnosed in travelers who visited friends and relatives. These conditions may have been unrelated to their clinical presentation and instead may have been acquired before their initial immigration, highlighting the importance of a full risk assessment that goes beyond the most recent trip, especially in this traveler group.

Risk for death related to travel cannot be calculated from GeoSentinel, but our data show a sample of deaths after return from travel that were reported to clinics specializing in management of travel or tropical diseases. Deaths during travel have been examined in other studies, with trauma, chronic diseases, injuries, suicide, and homicide described as predominant causes. Although infections have generally accounted for only 1% to 2% of deaths in some other reports (63–67), P. falciparum malaria, dengue, and respiratory agents were the most common underlying causes of the 28 deaths in our study. Most nontropical causes of death affected travelers who were older or had comorbid conditions, such as cancer or AIDS; 5 of these occurred after travel within Europe. Two deaths, 1 from Thailand and 1 from Martinique, were due to melioidosis, a frequently fatal septic illness caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei. This environmental gram-negative bacterium, found in soil and surface water, is being recognized increasingly outside its traditional foci in Asia and northern Australia (68). Seven additional cases from Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia were reported (Table 3). One quarter of deaths, but only 13.6% of all illnesses, occurred in business travelers, suggesting that employers should consider their potential liability if a consultation before travel is not provided.

The reported cases represent sentinel surveillance data among ill returned travelers visiting specialist clinics and do not reflect the experience of healthy travelers or those with mild or self-limited illness visiting primary care practices or other health care sites. In addition, there is some heterogeneity of referral patterns, patient populations, and travel demographic characteristics between GeoSentinel sites. The GeoSentinel surveillance form was designed primarily to tie diagnosis to exposure place and travel reason; detailed clinical information, such as comorbid conditions, physical findings, general laboratory or imaging data, treatment, or clinical course (except death), are not captured. We also cannot differentiate travelers who received a diagnosis related to screening tests done for demographic or itinerary-based considerations rather than one related to their presenting symptoms. The study design does not permit determination of absolute or relative risks. Nevertheless, our results show the relative frequency and range of illnesses seen in travelers.

In conclusion, this analysis will assist clinicians in framing potential differential diagnoses for ill returned travelers to facilitate either appropriate management plans or early referral for those who are seriously ill. Our results can also help clinicians and public health policymakers to think strategically about appropriate investment of time and resources during pretravel visits (54–56).

Context

International travel is increasing, as is illness by travelers after they return home.

Contribution

Through use of a large surveillance database, frequency and patterns of illness in ill returned travelers are described. Diagnoses varied widely by destination and reason for travel. Fewer than one half of ill returned travelers had medical evaluations before travel. Illness from vaccine-preventable diseases occurred even in patients who had been evaluated before travel.

Caution

Data were obtained at specialist travel medicine sites, not routine care sites.

Implication

Diagnosis and management of the ill returned traveler are complex. Appropriate evaluation before travel may be a missed opportunity to prevent illness and death in international travelers.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Elena Axelrod, Charles Miller, Kathy Smith, and the staff at each GeoSentinel site for data, programming, and administrative support; Surendra Karki, MD, for his assistance with the graphics; and Adam Plier for invaluable skills in network coordination and editorial support.

Grant Support: The GeoSentinel Surveillance Network is funded through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant 5U50CI000359) and with funding from the International Society of Travel Medicine.

Appendix: The GeoSentinel Surveillance Network

Additional members of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network who contributed data (in descending order) are Gerd-Dieter Burchard, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany; Brian J. Ward and J. Dick Maclean (deceased), McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Kevin C. Kain and Andrea K. Boggild, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Eric Caumes and Alice Pérignon, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Philippe Parola, Fabrice Simon, and Jean Delmont, Hôpital Nord and Hôpital Laveran, Marseille, France; Louis Loutan and François Chappuis, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; Mogens Jensenius, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway; Martin P. Grobusch, Peter J. de Vries, and Kartini Gadroen, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Anne E. McCarthy, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Graham V. Brown, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; Vanessa Field, InterHealth, London, United Kingdom; Shuzo Kanagawa, Yasuyuki Kato, and Yasutaka Mizunno, International Medical Center of Japan, Tokyo, Japan; William M. Stauffer and Patricia F. Walker, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Johan Ursing, Gabrielle Fröberg, and Helena Hervius Askling, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; Rainer Weber, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland; Natsuo Tachikawa, Hanako Kurai, and Hiroko Sagara, Yokohama Municipal Citizen's Hospital, Yokohama, Japan; Poh Lian Lim, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; N. Jean Haulman, David J. Roesel, and Elaine C. Jong, University of Washington and Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Washington; Bradley A. Connor, Cornell University, New York, New York; Giampiero Carosi, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy; DeVon C. Hale, Rahul Anand, and Stephanie S. Gelman, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Effrossyni Gkrania-Klotsas, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom; Rogelio López-Vélez and Jose A. Pérez-Molina, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain; Phyllis E. Kozarsky, Henry M. Wu, Jessica K. Fairley, and Carlos Franco-Paredes, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Christophe Rapp and Olivier Aoun, Hôpital d'Instruction des Armées Bégin, Saint-Mandé, France; Sarah Borwein, TravelSafe Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China; John D. Cahill and George McKinley, St. Luke's–Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, New York; Stefan Hag-mann, Michael Henry, and Andy O. Miller, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, Bronx, New York; Marc Mendelson and Peter Vincent, University of Cape Town and Tokai Medicross Travel Clinic, Cape Town, South Africa; Christina M. Coyle, Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, New York; Patrick W. Doyle and Wayne G. Ghesquiere, Vancouver General Hospital and Vancouver Island Health Authority, Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia, Canada; Lin H. Chen, Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Jean Vincelette, Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; Watcharapong Piyaphanee and Udomsak Silachamroon, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; Noreen A. Hynes, R. Bradley Sack, and Robin McKenzie, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; Cecilia Perret, School of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Marc T. Shaw and Annemarie Hern, Worldwise Travelers Health and Vaccination Centre, Auckland, New Zealand; Phi Truong Hoang Phu, Nicole M. Anderson, Trish Batchelor, and Dominique Meisch, International SOS Clinic, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; David G. Lalloo and Nicholas J. Beeching, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, United Kingdom; Andy Wang, Jane Eason, and Susan MacDonald, Beijing United Family Hospital and Clinics, Beijing, People's Republic of China; Carmelo Licitra and Antonio Crespo, Orlando Regional Health Center, Orlando, Florida; Susan Anderson, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Palo Alto, California; Johnnie A. Yates and Vernon E. Ans-dell, Kaiser Permanente, Honolulu, Hawaii; Prativa Pandey, Rashila Pradhan, and Holly Murphy, CIWEC Clinic Travel Medicine Center, Kathmandu, Nepal; Thomas B. Nutman and Amy D. Klion, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Catherine C. Smith and Alisdair A. MacConnachie, The Brownlee Centre at Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow, United Kingdom; Nancy P. Jenks and Christine A. Kerr, Hudson River HealthCare, Peekskill, New York; Luis M. Valdez and Hugo Siu, Clínica Anglo Americana, Lima, Peru; and Jose Flores-Figueroa and Pablo C. Okhuysen, Travel Medicine Research Clinic at Cuernavaca, University of Texas at Houston, Cuernavaca, Mexico.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M12-1036.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol and statistical code: Available from Dr. Freedman (freedman@uab.edu). Data set: Not available.

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: K. Leder, J. Torresi, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, A. Wilder-Smith, E. Schwartz, F. von Sonnenburg, A.C. Cheng, D.O. Freedman.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: K. Leder, J. Torresi, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, M.E. Wilson, J.S. Key-stone, E. Schwartz, E.D. Barnett, F. von Sonnenburg, J.S. Brownstein, A.C. Cheng, M.J. Sotir, D.H. Esposito, D.O. Freedman.

Drafting of the article: K. Leder, J. Torresi, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, A. Wilder-Smith, M.E. Wilson, J.S. Key-stone, E. Schwartz, J.S. Brownstein, A.C. Cheng, M.J. Sotir, D.O. Freedman.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: K. Leder, J. Torresi, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, A. Wilder-Smith, M.E. Wilson, E. Schwartz, E.D. Barnett, F. von Sonnenburg, J.S. Brownstein, A.C. Cheng, M.J. Sotir, D.H. Esposito, D.O. Freedman.

Final approval of the article: K. Leder, J. Torresi, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, A. Wilder-Smith, M.E. Wilson, J.S. Keystone, E. Schwartz, E.D. Barnett, F. von Sonnenburg, J.S. Brownstein, A.C. Cheng, M.J. Sotir, D.H. Esposito, D.O. Freedman.

Provision of study materials or patients: K. Leder, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, M.E. Wilson, J.S. Keystone, E. Schwartz, E.D. Barnett, F. von Sonnenburg, D.O. Freedman.

Statistical expertise: F. von Sonnenburg, A.C. Cheng, M.J. Sotir.

Obtaining of funding: D.O. Freedman.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: K. Leder, M.J. Sotir, D.O. Freedman.

Collection and assembly of data: K. Leder, J. Torresi, M.D. Libman, J.P. Cramer, F. Castelli, P. Schlagenhauf, M.E. Wilson, E. Schwartz, F. von Sonnenburg, J.S. Brownstein, D.O. Freedman.

References

- 1.United Nations World Tourism Organization UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2011 Edition. Accessed at http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights11enlr_1.pdf on 28 August 2012.

- 2.LaRocque RC, Rao SR, Lee J, Ansdell V, Yates JA, Schwartz BS, et al. Global TravEpiNet Consortium. Global TravEpiNet: a national consortium of clinics providing care to international travelers—analysis of demographic characteristics, travel destinations, and pretravel healthcare of high-risk US international travelers, 2009–2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:455–62. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir839. PMID: 22144534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacaner N, Stauffer B, Boulware DR, Walker PF, Keystone JS. Travel medicine considerations for North American immigrants visiting friends and relatives. JAMA. 2004;291:2856–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2856. PMID: 15199037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angell SY, Cetron MS. Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:67–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00013. PMID: 15630110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051331. PMID: 16407507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange WR, Snyder FR, Fudala PJ. Travel and ciguatera fish poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2049–53. PMID: 1417378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill DR. Health problems in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. J Travel Med. 2000;7:259–66. doi: 10.2310/7060.2000.00075. PMID: 11231210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Brien DP, Leder K, Matchett E, Brown GV, Torresi J. Illness in returned travelers and immigrants/refugees: the 6-year experience of two Australian infectious diseases units. J Travel Med. 2006;13:145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00033.x. PMID: 16706945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siikamäki HM, Kivelä PS, Sipilä PN, Kettunen A, Kainulainen MK, Ollgren JP, et al. Fever in travelers returning from malaria-endemic areas: don't look for malaria only. J Travel Med. 2011;18:239–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00532.x. PMID: 21722234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbinger KH, Drerup L, Alberer M, Nothdurft HD, Sonnenburg Fv, Löscher T. Spectrum of imported infectious diseases among children and adolescents returning from the tropics and subtropics. J Travel Med. 2012;19:150–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00589.x. PMID: 22530821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steffen R, Rickenbach M, Wilhelm U, Helminger A, Schär M. Health problems after travel to developing countries. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:84–91. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.84. PMID: 3598228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan ET, Wilson ME, Kain KC. Illness after international travel. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:505–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020118. PMID: 12181406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlieghe ER, Jacobs JA, Van Esbroeck M, Koole O, Van Gompel A. Trends of norfloxacin and erythromycin resistance of Campylobacter jejuni/Campylobacter coli isolates recovered from international travelers, 1994 to 2006. J Travel Med. 2008;15:419–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00236.x. PMID: 19090796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakanen A, Jousimies-Somer H, Siitonen A, Huovinen P, Kotilainen P. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates in travelers returning to Finland: association of ciprofloxacin resistance to travel destination. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:267–70. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020227. PMID: 12604004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castelli F, Pezzoli C, Tomasoni L. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2001;8:S26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2001.tb00543.x. PMID: 12186670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, Campbell-Forrester S, Ashley D, Thompson S, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler's diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA. 1999;281:811–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.811. PMID: 10071002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, Chatterjee S, Cavalcanti AM, Collard F, et al. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:231–7. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.19007. PMID: 15541226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor BA. Sequelae of traveler's diarrhea: focus on postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S577–86. doi: 10.1086/432956. PMID: 16267722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thabane M, Marshall JK. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3591–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3591. PMID: 19653335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupont AW. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:378–84. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0046-8. PMID: 17991338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thabane M, Kottachchi DT, Marshall JK. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:535–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03399.x. PMID: 17661757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:585–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.585. PMID: 11289669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, Keystone JS, Kain KC, von Sonnenburg F, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1560–8. doi: 10.1086/518173. PMID: 17516399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askling HH, Nilsson J, Tegnell A, Janzon R, Ekdahl K. Malaria risk in travelers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:436–41. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040677. PMID: 15757560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leder K, Black J, O'Brien D, Greenwood Z, Kain KC, Schwartz E, et al. Malaria in travelers: a review of the GeoSentinel surveillance network. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1104–12. doi: 10.1086/424510. PMID: 15486832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loutan L. Malaria: still a threat to travellers. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:158–63. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00367-9. PMID: 12615380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson ME, Freedman DO. Etiology of travel-related fever. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:449–53. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a95e27. PMID: 17762776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odolini S, Parola P, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Caumes E, Schlagenhauf P, López-Vélez R, et al. Travel-related imported infections in Europe, EuroTravNet 2009. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:468–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03596.x. PMID: 21848975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilder-Smith A, Gubler DJ. Geographic expansion of dengue: the impact of international travel. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:1377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.07.002. PMID: 19061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunkard JM, Robles López JL, Ramirez J, Cifuentes E, Rothenberg SJ, Hunsperger EA, et al. Dengue fever seroprevalence and risk factors, Texas-Mexico border, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1477–83. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.061586. PMID: 18257990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Locally acquired Dengue—Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:577–81. PMID: 20489680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gjenero-Margan I, Aleraj B, Krajcar D, Lesnikar V, Klobučar A, Pem-Novosel I, et al. Autochthonous dengue fever in Croatia, August–September 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011;16 PMID: 21392489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Ruche G, Souarès Y, Armengaud A, Peloux-Petiot F, Delaunay P, Desprès P, et al. First two autochthonous dengue virus infections in metropolitan France, September 2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19676. PMID: 20929659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burt FJ, Rolph MS, Rulli NE, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. Chikungunya: a re-emerging virus. Lancet. 2012;379:662–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60281-X. PMID: 22100854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaki SA, Karande S. Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever: a review. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:324–37. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1405. PMID: 21628808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensenius M, Davis X, von Sonnenburg F, Schwartz E, Keystone JS, Leder K, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Multicenter GeoSentinel analysis of rickettsial diseases in international travelers, 1996–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090677. PMID: 19891867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meltzer E, Leshem E, Steinlauf S, Michaeli S, Sidi Y, Schwartz E. Human African trypanosomiasis in a traveler: diagnostic pitfalls. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:264–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0512. PMID: 22855756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Migchelsen SJ, Büscher P, Hoepelman AI, Schallig HD, Adams ER. Human African trypanosomiasis: a review of non-endemic cases in the past 20 years. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.03.018. PMID: 21683638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lederman ER, Weld LH, Elyazar IR, von Sonnenburg F, Loutan L, Schwartz E, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Dermatologic conditions of the ill returned traveler: an analysis from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.12.008. PMID: 18343180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herbinger KH, Siess C, Nothdurft HD, von Sonnenburg F, Löscher T. Skin disorders among travellers returning from tropical and non-tropical countries consulting a travel medicine clinic. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1457–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02840.x. PMID: 21767336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon M, Benenson S, Baum S, Schwartz E. Tropical skin infections among Israeli travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:868–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0471. PMID: 22049040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris-Jones R, Morris-Jones S. Travel-associated skin disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:675–89. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.05.010. PMID: 22963777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ansart S, Perez L, Jaureguiberry S, Danis M, Bricaire F, Caumes E. Spectrum of dermatoses in 165 travelers returning from the tropics with skin diseases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:184–6. PMID: 17255251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caumes E, Carrière J, Guermonprez G, Bricaire F, Danis M, Gentilini M. Dermatoses associated with travel to tropical countries: a prospective study of the diagnosis and management of 269 patients presenting to a tropical disease unit. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:542–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.3.542. PMID: 7756473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:302–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70098-7. PMID: 18471775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gautret P, Schwartz E, Shaw M, Soula G, Gazin P, Delmont J, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Animal-associated injuries and related diseases among returned travellers: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Vaccine. 2007;25:2656–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.034. PMID: 17234310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El Hajj L, Thellier M, Carrière J, Bricaire F, Danis M, Caumes E. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis imported into Paris: a review of 39 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:120–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01991.x. PMID: 15125502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindgren E, Andersson Y, Suk JE, Sudre B, Semenza JC. Public health. Monitoring EU emerging infectious disease risk due to climate change. Science. 2012;336:418–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1215735. PMID: 22539705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Increased transmission and outbreaks of measles—European Region, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1605–10. PMID: 22129994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joseph CA, Ricketts KD, Yadav R, Patel S. European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Travel-associated Legionnaires disease in Europe in 2009. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19683. PMID: 20961516. [Google Scholar]

- 51.WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines—June 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:261–76. PMID: 22905367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1–62. PMID: 20689501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boggild AK, Castelli F, Gautret P, Torresi J, von Sonnenburg F, Barnett ED, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Latitudinal patterns of travel among returned travelers with influenza: results from the GeoSentinel Surveil-lance Network, 1997–2007. J Travel Med. 2012;19:4–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00579.x. PMID: 22221805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012: The Yellow Book. Oxford Univ Pr; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization . International Travel and Health 2012. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field V, Ford L, Hill DR, editors. Health Information for Overseas Travel. National Travel Health Network and Centre; London, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lalloo DG, Hill DR. Preventing malaria in travellers. BMJ. 2008;336:1362–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a153. PMID: 18556317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore SJ, Mordue Luntz AJ, Logan JG. Insect bite prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:655–73. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.07.002. PMID: 22963776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fulford M, Keystone JS. Health risks associated with visiting friends and relatives in developing countries. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0023-z. PMID: 15610671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1185–93. doi: 10.1086/507893. PMID: 17029140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Behrens RH, Barnett ED. Visiting friends and relatives. In: Keystone JS, Freedman DO, Kozarsky PE, Connor BA, Nothdurft HD, editors. Travel Medicine. 3rd ed Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hagmann S, Reddy N, Neugebauer R, Purswani M, Leder K. Identifying future VFR travelers among immigrant families in the Bronx, New York. J Travel Med. 2010;17:193–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00399.x. PMID: 20536889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hargarten SW, Baker TD, Guptill K. Overseas fatalities of United States citizen travelers: an analysis of deaths related to international travel. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:622–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82379-0. PMID: 2039100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prociv P. Deaths of Australian travellers overseas. Med J Aust. 1995;163:27–30. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124578.x. PMID: 7609684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tonellato DJ, Guse CE, Hargarten SW. Injury deaths of US citizens abroad: new data source, old travel problem. J Travel Med. 2009;16:304–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00318.x. PMID: 19796099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guse CE, Cortés LM, Hargarten SW, Hennes HM. Fatal injuries of US citizens abroad. J Travel Med. 2007;14:279–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00133.x. PMID: 17883458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD, Sandhu J. Death and international travel—the Canadian experience: 1996 to 2004. J Travel Med. 2007;14:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00107.x. PMID: 17367476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Currie BJ, Dance DA, Cheng AC. The global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis: an update. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(Suppl 1):S1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70002-6. PMID: 19121666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]