Abstract

We investigated serotype 6A/6C invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence, genetic diversity, and carriage before and after 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) introduction in Alaska. IPD cases (1986–2009) were identified through population-based laboratory surveillance. Isolates were initially serotyped by conventional methods, and 6C isolates were differentiated from 6A by polymerase chain reaction. Among invasive and carriage isolates initially typed as 6A, 35% and 50% were identified as 6C, respectively. IPD rates caused by serotype 6A or 6C among children <5 years did not change from the pre- to post-PCV7 period (P = 0.71 and P = 0.09, respectively). Multilocus sequence typing of IPD isolates revealed 28 sequence types. The proportion of serotype 6A carriage isolates decreased from 7.4% pre-PCV7 to 1.8% (P < 0.001) during 2008–2009; the proportion of serotype 6C carriage isolates increased from 3.0% to 8.4% (P = 0.004) among children <5 years. Continued surveillance is warranted to monitor changes in serotype distribution and prevalence.

Keywords: Pneumococci, Surveillance, Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Multilocus sequence typing

1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains a leading cause of bacterial pneumonia, otitis media, sepsis, meningitis, and bacteremia worldwide, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. The most important virulence factor of the pneumococcus is the polysaccharide capsule which surrounds the bacterium and protects it from phagocytosis by host immune cells. The polysaccharide capsule of S. pneumoniae is antigenically diverse and has formed the basis for serologic classification of pneumococci. Greater than 90 different serotypes have been described, including the recently discovered serotype 6C (Park et al., 2007a, 2007b). This serotype is phenotypically indistinguishable from serotype 6A when using the Quellung reaction for serotyping but has a chemical structure distinct from 6A by virtue of the change in the wciN gene region of the capsular locus encoding for galactosyl transferase (Park et al., 2007a).

One of the strategies used to reduce the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease is vaccination directed against the pneumococcal polysaccharide capsule. In children <2 years of age, where the greatest burden of disease exists, recent efforts to develop effective pneumococcal vaccines have been concentrated on conjugate vaccines in which the capsular polysaccharides are covalently coupled to carrier proteins. The first such conjugate vaccine (PCV7), which was introduced into the universal immunization program in the United States in 2000, contains the 7 most common pneumococcal serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) causing invasive disease in infants and young children prior to its introduction in 2000. This vaccine confers protection against serotype 6B, and most (Dagan et al., 1996, 2002; Eskola et al., 2001) but not all (Mbelle et al., 1999) studies have found that PCV7 provides cross-protection against serotype 6A. More recently, IPD data suggest that PCV7 does not provide cross-protection against serotype 6C (Carvalho et al., 2009; Green et al., 2011; Millar et al., 2010; Park et al., 2008b). The next-generation pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV13, which contains the PCV7 serotypes plus serotypes 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, and 19A, was introduced into the routine vaccination schedule for children in the USA in 2010.

In Alaska, pneumococcal disease rates have been among the highest reported in the world, particularly among Alaska Native children less than 2 years of age (Davidson et al., 1994). Studies in Alaska have also demonstrated pneumococcal carriage to be high among Alaska Native children (Hennessy et al., 2005; Park et al., 2008b). PCV7 was introduced into the routine childhood vaccination schedule in Alaska in 2001. Uptake of this vaccine was rapid with 92% and 67% of 19–35-month-old Alaska Native and non-native children, respectively, having received this vaccine by 2003 (Hennessy et al., 2002). Coverage of PCV7 has remained high (Park et al., 2008b; Singleton et al., 2007; Wenger et al., 2010), and since introduction, rates of IPD caused by serotypes present in the vaccine decreased rapidly, but IPD rates caused by nonvaccine serotypes subsequently increased, specifically in Alaska Native children less than 5 years of age (Singleton et al., 2007; Wenger et al., 2010). In these studies, serotype 6A was not differentiated from serotype 6C. Here we describe the impact of the PCV7 introduction in Alaska (2001) on serotypes 6A and 6C by 1) re-serotyping all invasive and carriage isolates previously characterized as serotype 6A, 2) determining antimicrobial resistance among isolates, and 3) characterizing the genetic diversity of serotype 6A and serotype 6C invasive isolates using multilocus sequence typing (MLST).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Invasive disease surveillance (1986–2009)

The Arctic Investigations Program (AIP) established a population-based statewide surveillance system to monitor invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in 1986. Isolates of S. pneumoniae are received at the AIP laboratory in Anchorage, AK, from 23 regional hospital laboratories processing sterile site specimens (blood and cerebrospinal, pleural, peritoneal, or joint fluid) in the state. From 1986 through 2009, 2815 isolates of invasive S. pneumoniae were submitted to AIP. Pneumococci were confirmed by colony morphology, susceptibility to optochin (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA), and bile solubility. All isolates were serotyped by slide agglutination and confirmed by the Quellung reaction using group- and type-specific antisera (Staten Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark).

2.2. Carriage study (2000–2004, 2008–2009)

Detailed methods of the carriage study conducted prior to 2008 have been described (Hammitt et al., 2006; Hennessy et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2004). In 2008 and 2009, we conducted community-wide surveys of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization in 4 rural villages during April and May that had been surveyed from 2000 to 2004. In addition, we conducted observational, cross-sectional carriage surveys at 3 Anchorage pediatric clinics during February and March. Laboratory methods for the carriage study were as previously described except for during 2008–2009 where STGG (skim milk, tryptone, glucose, and glycerine) was used as the transport media. These studies were approved by the Alaska Area and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from adult study participants for themselves and for their children in the rural arm of the study and from the parent or guardian of children enrolled in the Anchorage arm of the study.

2.3. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined for each IPD isolate by microbroth dilution and for colonizing pneumococci by Etest (AB BIODISK, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Isolates with penicillin MICs of ≥2 and 0.12–1.0 μg/mL were considered to be resistant and intermediately resistant to penicillin, respectively (CLSI, 2007 guidelines). Multidrug-resistant isolates were defined as having intermediate or full resistance to 3 or more different classes of antibiotics.

2.4. Serotype 6C determination

Crude DNA extracts from all invasive pneumococcal isolates and carriage isolates previously reported as serotype 6A were prepared and subjected to a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay containing primer pairs specific for cpsA and serogroup 6, as previously described (Pai et al., 2006). Serotype 6C was differentiated from serotypes 6A and 6B by a third primer pair specific for the wciN gene (Carvalho et al., 2009).

2.5. MLST analysis

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed as previously described (Enright and Spratt, 1998), with modifications (Moore et al., 2008) on invasive serotype 6A and 6C isolates recovered from 1986 to 2009. The sequence types (ST) were determined by comparing the sequences with alleles downloaded from the pneumococcal MLST database (http://spneumoniae.mlst.net). Clonal complexes were assigned using the eBURST algorithm with the software available at the MLST website (http://www.mlst.net).

2.6. Statistical analysis

To compare rates of IPD, we used 1986–1993 and 1994–2000 as pre-PCV7 vaccine periods and 2001–2009 as the post-PCV7 period. To calculate incidence, population estimates were obtained from the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development website. We assessed changes in IPD incidence of serotype 6A and 6C by use of a trend test for Poisson rates. We assessed the proportion of carriage isolates that were serotype 6A and 6C among pneumococcal carriers using the Cochran–Armitage test for trend. We compared antimicrobial resistance and clonal complex distribution between 2 periods by use of the likelihood ratio chi-square test. All P values were exact when sample size necessitated. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and StatXact 8.0 (Cytel Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Incidence and distribution of IPD caused by serotype 6A and 6C isolates

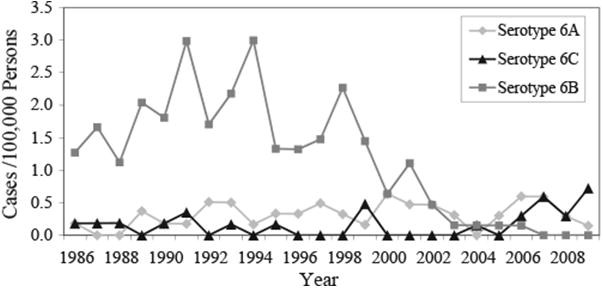

From 1986 to 2009, 2815 invasive pneumococcal isolates were received at AIP. Of these, 72 (2.6%) were conventionally serotyped as 6A. With the use of multiplexed PCR assay to differentiate serotype 6C from serotype 6A isolates, 35% (25/72) of isolates conventionally serotyped as 6A were identified as 6C. Overall rates of IPD caused by serotype 6A did not change significantly from the pre- (1986–1993, 0.25/100,000; 1994–2000, 0.35/100,000) to the post-PCV7 period (2001–2009, 0.35/100,000). Likewise, rates of IPD caused by serotype 6C showed no significant differences in the pre-PCV7 periods (0.16/100,000 and 0.09/100,000) and post-PCV7 periods (0.24/100,000). IPD rates in children <5 years of age were 1.81 per 100,000 persons for serotype 6A versus 0.24 per 100,000 persons for serotype 6C for all years of surveillance combined. When we stratified by race and age group, no statistically significant changes in rates of invasive disease caused by serotype 6A or 6C were noted over the study period and pre- to post-vaccine years. Prior to the introduction of PCV7, the majority of IPD cases in Alaska due to serogroup 6 were caused by serotype 6B (81%); since 2004, only 3 cases of serotype 6B were seen compared to 13 cases of serotype 6A and 14 cases of serotype 6C (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of invasive pneumococcal serotype 6A, 6B, and 6C isolates in Alaska over time (1986–2009), all ages.

Among serotype 6A and 6C cases, 60% had a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, 31% had bacteremia and there were a total of 3 cases of meningitis. We found no difference between serotype 6A and 6C IPD with regard to gender, clinical presentation, or the case fatality ratio, however, serotype 6A isolates were more likely to be from children <5 years of age (49% [23/27]) than serotype 6C isolates (12% [3/25], P = 0.001).

3.2. Antimicrobial susceptibility

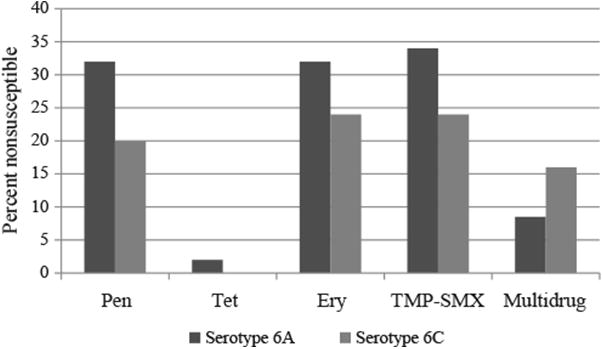

Susceptibility results for the invasive pneumococcal isolates are shown in Fig. 2. Among serotype 6A isolates, 49% (23/47) were susceptible to all antibiotics tested. Of the 15 penicillin-nonsusceptible 6A isolates, 13 showed intermediate resistance to penicillin. In addition, 34% (16/47) were trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) nonsusceptible, 32% (15/47) were erythromycin resistant, and 8.5% (4/47) were multidrug resistant. Among the serotype 6C isolates, 64% (16/25) were susceptible to all antibiotics tested. Five isolates (20%) were nonsusceptible to penicillin, 24% (6/25) were erythromycin- and TMP-SMX resistant, and 16% (4/25) were multidrug resistant.

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial resistance (% nonsusceptible) among invasive S. pneumoniae serotype 6A and 6C isolates from 1986 to 2009 in Alaska.

Prior to the introduction of PCV7 in 2001, 8% (2/26) of serotype 6A isolates were penicillin or erythromycin nonsusceptible. After the introduction of PCV7, the proportion of serotype 6A isolates nonsusceptible to penicillin or erythromycin increased to 62% (13/21) (P < 0.01). For serotype 6C isolates, nonsusceptibility to penicillin increased from 0% (0/11) to 36% (5/14) (P = 0.05) and nonsusceptibility to TMP-SMX increased from 0% (0/11) to 43% (6/14).

3.3. Genotypes

MLST of the 47 serotype 6A isolates yielded 21 sequence types (STs), including 8 new STs (Table 1). Comparison of these STs with those present in the MLST database for S. pneumoniae by eBURST analysis showed that 17 of these STs fell into 7 clonal complexes (CCs) based on a minimum similarity of 5 identical loci and 3 singletons (Table 1). While the CC distribution of serotype 6A isolates changed from the pre-PCV7 and the post-PCV7 period, it was not significant. Prior to the introduction of PCV7 in Alaska, the majority (81%, 21/26) of serotype 6A isolates clustered into 4 CCs (395, 460, 473, and 690); of these, the majority were in CC460 (38.5%, 10/26) and CC473 (27%, 7/26). After the introduction of PCV7, serotype 6A isolates clustered into 4 CCs (395, 460, 473, and 2090), the majority of which were in CC473 (57%, 12/21).

Table 1.

Distribution of serotype 6A and 6C genotypes pre- and post-PVC7 in Alaska from 1986 to 2009.

| Clonal complex | ST (no.) | Number of isolates (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Serotype 6A | Serotype 6C | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Pre-PCV7a | Post-PCV7b | Pre-PCV7 | Post-PCV7 | ||

| CC395 | ST327 (3) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| ST4096 (1) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| CC460 | ST65 (1) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| ST460 (10) | 8 (30.8) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| ST1360 (1) | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| CC113 | ST1752 (1) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| CC473 | ST473 (14) | 3 (11.5) | 9 (42.9) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (7.1) |

| ST4093 (2) | 2 (7.7) | ||||

| ST4330 (1) | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| ST4094 (1) | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| ST4095 (1) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| ST4284 (1) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| ST4331 (1) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| CC690 | ST690 (1) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| ST2092 (1) | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| CC490 | ST490 (1) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| CC2090 | ST376 (2) | 2 (9.5) | |||

| ST1339 (1) | 1 (4.8) | ||||

| CC1390 | ST1390 (5) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (14.3) | ||

| ST4333 (1) | 1 (7.1) | ||||

| ST2899 (4) | 4 (36.4) | ||||

| ST4285 (1) | 1 (9.1) | ||||

| CC1379 | ST1379 (8) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (50) | ||

| ST1292 (3) | 3 (21.4) | ||||

| ST2064 (1) | 1 (9.1) | ||||

| Singleton | ST660 (3) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| ST4332 (1) | 1 (3.8) | ||||

| Total | 26 (100) | 21 (100) | 11 (100) | 14 (100) | |

Pre-PCV7 = 1986–2000.

Post-PCV7 = 2001–2009.

MLST of 25 serotype 6C isolates yielded 8 STs, including 2 new STs (Table 1). eBURST analysis revealed that all 8 STs fell into 3 CCs (CC473, CC1379, and CC1390). Eighteen (72%) serotype 6C isolates were related to STs associated with serotype 6A and included ST473 (n = 2), ST1390 (n = 5), ST1379 (n = 8), ST1292 (n = 3), and ST4333 (n = 1). The distribution of STs among the serotype 6C isolates differed significantly after the introduction of PCV7 (P = 0.002; Table 1). Prior to the introduction of PCV7, the majority (73%, 8/11) of serotype 6C isolates fell into CC1390. After the introduction of PCV7, the majority (71%, 10/14) of serotype 6C isolates fell into CC1379.

When we examined whether there was clustering of clonal complexes by epidemiologic characteristics, restricting our analysis to clonal complexes or STs with a sample size of ≥10 isolates, we found no association between clonal complex or STs and age, gender, case fatality ratio, or clinical syndromes. We did not find any clustering of individual clonal complexes or STs according to the village residence of cases either.

3.4. Trends in serotype 6A and 6C carriage

Over all years of the study, 38% of children (<5 years of age) in urban Anchorage were carriers of pneumococcus, compared to 58% of rural children (<5 years of age) and 33% of persons ≥5 years of age in rural Alaska. Among 4667 pneumococcal carriage isolates (from carriage studies performed in 2000–2004 and 2008–2009), 440 (9%) were serotyped as 6A; 50% (222/440) of isolates conventionally serotyped as 6A were subsequently identified as 6C. Over the 4 time periods (2000, 2001–2002–2003–2004, and 2008–2009), the proportion of 6A carriage isolates among children <5 years of age decreased from 7.4% to 1.8% (P < 0.001; Table 2). No statistically significant changes in the proportion of 6A carriage isolates were noted among participants ≥5 years of age in rural Alaska. However, statistically significant increases in the proportion of serotype 6C carriage isolates were noted among all study participants in all the study years following the introduction of PCV7 (Table 2). Forty-eight percent of serotype 6A (104/218) and 8% of serotype 6C (18/221) carriage isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin. For TMP-SMX, 47% (103/218) and 7% (16/221) of carriage isolates were nonsusceptible among serotypes 6A and 6C, respectively.

Table 2.

Pneumococcal serotype 6A and 6C colonization by year and age in Alaska.

| Study year (no. of total isolates) | <5 years of age | Study year (no. of total isolates) | ≥5 years of age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| %a (no.) of isolates | % (no.) of isolates | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Serotype 6A | Serotype 6C | Serotype 6A | Serotype 6C | ||

| 2000 (393) | 7.4% (29) | 3.0% (12) | 2000 (617) | 1.6% (10) | 1.9% (12) |

| 2001–2002 (518) | 9.9% (51) | 6.4% (33) | 2001–2002 (757) | 5.0% (38) | 6.1% (46) |

| 2003–2004 (552) | 6.5% (36) | 4.5% (25) | 2003–2004 (1093) | 4.0% (44) | 3.1% (34) |

| 2008–2009 (393) | 1.8% (7) | 8.4% (33) | 2008–2009 (344) | 0.8% (3) | 7.9% (27) |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.004 | P value | 0.47 | 0.001 |

Percentages represent the proportion of pneumococcal carriers with serotype 6A or 6C.

4. Discussion

Serotype 6C was first described in 2007 (Park et al., 2007a). Since then, there have been a number of reports detailing the prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and genetic diversity among serotype 6C isolates collected from both invasive disease and nasopharyngeal colonization studies (Campos et al., 2009; Carvalho et al., 2009; du Plessis et al., 2008; Green et al., 2011; Hermans et al., 2008; Jacobs et al., 2008, 2009; Nahm et al., 2009; Nunes et al., 2009; Rolo et al., 2011a; Tocheva et al., 2010). In studies that looked at the prevalence of serotype 6C among invasive and carriage isolates, it was found that anywhere between 5% and 100% of isolates that originally typed as 6A were subsequently identified as serotype 6C (Campos et al., 2009; Carvalho et al., 2009; du Plessis et al., 2008; Hermans et al., 2008; Jacobs et al., 2009; Millar et al., 2010; Rolo et al., 2011a). This large range was primarily due to the fact that the proportion of serotype 6C isolates increased over time, while the proportion of serotype 6A isolates decreased. In Alaska, we have conducted statewide laboratory surveillance for IPD since 1986. Prior to the introduction of PCV7, the majority of IPD due to serogroup 6 was caused by serotype 6B with a small proportion caused by serotype 6A (Fig. 1). By 2002, the number of IPD cases caused by serotype 6B had decreased to levels not seen in the previous 16 years and continued to decrease until the last case in 2006. While others have reported significant increases in IPD caused by serotype 6C since the introduction of PCV7 along with significant decreases in serotype 6A IPD in the post-vaccine years, this has not been the case in our population (Carvalho et al., 2009; Millar et al., 2010). While we did see an increase in the incidence of serotype 6C IPD (0.16 to 0.24 cases per 100,000 population), it was not statistically significant. Over this same time period (1986–2009), the incidence of serotype 6A IPD remained stable at about 0.3 cases per 100,000 population. It is important to mention that while we did not see a significant decline in the rate of IPD caused by serotype 6A among children <5 years of age in the post-PCV7 era (2001–2009), we have not seen a case of 6A disease in children since 2006. Breakdown by age of patients and ethnicity did show that the incidence of serotype 6A IPD decreased from 6.1 to 1.62 cases per 100,000 population in Alaska Native children <5 years of age; however, there was no significant increase in serotype 6C IPD. It is interesting to note that the first case of invasive serotype 6C disease in children <5 years of age was not seen in Alaska until 2004, and only 2 cases (11%) in total were detected through 2009. This is in contrast to IPD caused by serotype 6A where 53% of disease was in children <5 years of age. These findings are similar to those reported by Millar et al. (2010) who found that only 4% of serotype 6C cases occurred among children <5 years of age, while >40% of serotype 6A cases were among children <2 years of age.

Both serotype 6A and 6C isolates exhibited decreased susceptibility to penicillin after the introduction of PCV7. Others have reported finding significantly greater proportions of penicillin-resistant isolates within serotype 6A than within serotype 6C (Carvalho et al., 2009; Park et al., 2008a). In contrast, we found that 32% of serotype 6A and 18.5% of serotype 6C isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin. All of the serotype 6C isolates with reduced susceptibility to penicillin were found in the years (2007–2009) after the introduction of PCV7, and of those, 40% were fully resistant. In addition to decreased susceptibility to penicillin, we have also seen decreased susceptibility to erythromycin and TMP-SMX among our serotype 6A and 6C isolates since the introduction of PCV7. Multidrug resistance among serotype 6C isolates increased later in the PCV7 era which is similar to what has previously been reported by others (du Plessis et al., 2008; Jacobs et al., 2008; Rolo et al., 2011a). This increase in resistance to penicillin and multiple other antibiotics among serotype 6C isolates warrants close monitoring as we move into the new era of higher valency conjugate vaccines.

Among our collection of 47 invasive serotype 6A isolates, 21 different STs were found over this 30-year surveillance period. Two major lineages accounted for 66% of these isolates (CC473 and CC460). Similar findings have been reported by Jacobs et al. (2009) who found that among their serotype 6A isolates, the majority were STs 473, 460, 395, and 376. In the Carvalho et al. (2009) study, 4 STs (1292, 473, 395, and 376) were observed with ST376, accounting for approximately 30% of serotype 6As, including the majority of isolates fully resistant to penicillin and the majority of erythromycin-resistant isolates. In this study, the majority of penicillin-nonsusceptible serotype 6A isolates were ST473, ST660, or ST376, and only 1 ST473 isolate was fully resistant to penicillin.

The presence of 8 STs found among only 27 serotype 6C isolates in this study are consistent with other studies that have described a high degree of genetic diversity among this serotype (Campos et al., 2009; Carvalho et al., 2009; Green et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2009; Nunes et al., 2009; Rolo et al., 2011b). Of the 8 STs of serotype 6C isolates reported in this study, 4 (1390, 1379, 473, and 1292) have been previously associated with serotype 6A. While ST2899 and ST4285 found in this study are associated solely with serotype 6C, they are double- and triple-locus variants, respectively, of ST1390. Other studies have reported similar findings (Carvalho et al., 2009; Green et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2009). Among the serotype 6C isolates analyzed by Jacobs et al. (2009), 9 MLST clusters were identified. Five of these clusters were related to clonal complexes associated with serotype 6A (473, 1379, 490, 690, and 1390). Carvalho et al. (2009) reported that more than a third of the serotype 6C isolates they analyzed were sequence types associated primarily with serotype 6A isolates. In the study by Green et al. (2011), 50% of the serotype 6C isolates analyzed were STs previously associated with serotype 6A. It is interesting to note that among the serotype 6A and 6C isolates analyzed in this study, only isolates of ST473 were found within both serotypes and that ST1390 and ST1379, which are frequently found among serotype 6A isolates, were found exclusively among 6C isolates.

We have previously described the impact of PCV7 on nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci in community settings in the pre-PCV era (1998–2000) and the early PCV era (2001–2004) (Hammitt et al., 2006; Hennessy et al., 2005; Moore et al., 2004; Park et al. 2008b; Singleton et al., 2007). In these reports, we described a rapid and significant decrease in carriage of vaccine types followed by a significant increase in carriage of nonvaccine types across all age groups; however, carriage of serotypes 6A and 6C was unaffected during this time period. While our data on the epidemiology of IPD due to serotypes 6A and 6C showed little evidence of cross protection from PCV7, data from carriage studies performed in 2008–2009 showed a significant decrease in the proportion of serotype 6A isolates carried by children <5 years of age. It is important to note that the decline in carriage of serotype 6A was delayed and not observed in the 3 years following PCV7 introduction which is similar to what was observed for serotype 6A IPD. We also noted significant increases in the proportion of serotype 6C isolates carried among all study participants, regardless of age.

Our findings on disease rates are limited by the small population size leading to small numbers of cases. The small number of IPD cases of individual serotypes 6A and 6C limits our power to detect trends over time in these 2 serotypes. Therefore, long-term surveillance is important to confirm the trends we report here. Samples sizes of individual clonal complexes of 6A and 6C IPD limited our ability to test for epidemiologic differences between them.

In summary, serotype 6C isolates have been circulating in Alaska since we began IPD surveillance in 1986. While others have reported the near disappearance of serotype 6A IPD in the post-PCV7 era presumably due to the cross-protection provided by serotype 6B, we did not see a similar decline in serotype 6A IPD, particularly among children <5 years of age, for several years after PCV7 introduction. However, we did observe an increase in the rates of serotype 6C IPD. Among older children and adults, we observed an increase in serotype 6A IPD but no change in the incidence of serotype 6C IPD. The prevalence and distribution of pneumococcal serotypes has changed considerably since the introduction of PCV7. With the introduction of PCV13 into the routine childhood vaccination schedule statewide in 2010, we expect to see further declines in serotype 6A IPD and perhaps declines in serotype 6C IPD as a result of cross-protecting antibodies to the 6A antigen (Cooper et al., 2011). Continued surveillance for IPD will help us better assess the impact of this new vaccine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinicians and microbiology laboratory personnel of the hospitals participating in statewide surveillance for IPD in Alaska as well as all the study participants and clinic staff who participated in the carriage studies. The authors also thank the entire staff at the Arctic Investigations Program for their contributions to this study, particularly Carolynn DeByle, Julie Morris, and Carolyn Zanis for the microbiology work.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Campos LC, Carvalho M, Beall BW, Cordeiro SM, Takahashi D, Reis MG, et al. Prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C among invasive and carriage isolates in metropolitan Salvador, Brazil, from 1996 to 2007. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;65:112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho MG, Pimenta FC, Gertz RE, Joshi HH, Trujillo AA, Keys LE, et al. PCR-based quantitation and clonal diversity of the current prevalent invasive serogroup 6 pneumococcal serotype, 6C, in the United States in 1999 and 2006 to 2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:554–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01919-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 15th informational supplement (M100-S17) Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Yu X, Sidhu M, Nahm MH, Fersten R, Jansen KU. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13 elicits cross-functional opsonophagocytic killing responses in humans to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6C and 7A. Vaccine. 2011;29:7207–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan R, Melamed R, Muallem M, Piglansky L, Greenberg D, Abramson O, et al. Reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci during the second year of life by a heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1271–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan R, Fivon-Lavi N, Zamir O, Sikuler-Cohen M, Guy L, Janco J, et al. Reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae after administration of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to toddlers attending day care centers. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:927–36. doi: 10.1086/339525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M, Parkinson AJ, Bulkow LR, Fitzgerald MA, Peters HV, Parks DJ. The epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Alaska, 1986–1990—ethnic differences and opportunities for prevention. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:368–76. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis M, von Gottberg A, Madhi SA, Hattingh O, de Gouveia L, Klugman KP. Serotype 6C is associated with penicillin-susceptible meningeal infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults among invasive pneumococcal isolates previously identified as serotype 6A in South Africa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:S66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright MC, Spratt BG. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144:3049–60. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, Jokinen J, Haapakoski J, Herva E, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:403–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Mason EO, Kaplan SL, Lamberth LB, Stovall SH, Givner LB, et al. Increase of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C at 8 children's hospitals in the United States from 1993–2009. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2097–101. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02207-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt LL, Bruden DL, Butler JC, Baggett HC, Hurlburt DA, Reasonover A, et al. Indirect effect of conjugate vaccine on adult carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: an explanation of trends in invasive pneumococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1487–94. doi: 10.1086/503805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy TW, Petersen KM, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Hurlburt DA, Getty M, et al. Changes in antibiotic-prescribing practices and carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: a controlled intervention trial in rural Alaska. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1543–50. doi: 10.1086/340534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy TW, Singleton RJ, Bulkow LR, Bruden DL, Hurlburt DA, Parks D, et al. Impact of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive disease, antimicrobial resistance and colonization in Alaska Natives: progress towards elimination of a health disparity. Vaccine. 2005;23:5464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans PW, Blommaart M, Park IH, Nahm MH, Bogaert D. Low prevalence of recently discovered pneumococcal serotype 6C isolates among healthy Dutch children in the pre-vaccination era. Vaccine. 2008;26:449–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MR, Good CE, Bajaksouzian S, Windau AR. Emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 19A, 6C, and 22F and serogroup 15 in Cleveland, Ohio, in relation to introduction of the protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1388–95. doi: 10.1086/592972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MR, Bajaksouzian S, Bonomo RA, Good CE, Windau AR, Hujer AM, et al. Occurrence, distribution, and origins of Streptococcus pneumonia serotype 6C, a recently recognized serotype. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:64–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01524-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbelle N, Huebner RE, Wasas AD, Kimura A, Chang I, Klugman KP. Immunogenicity and impact on nasopharyngeal carriage of a nonavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1171–6. doi: 10.1086/315009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar EV, Pimenta FC, Roundtree A, Jackson D, Carvalho MG, Perilla MJ, et al. Pre- and post-conjugate vaccine epidemiology of pneumococcal serotype 6C invasive disease and carriage within Navajo and White Mountain Apache communities. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1258–65. doi: 10.1086/657070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Hyde TB, Hennessy TW, Parks DJ, Reasonover AL, Harker-Jones M, et al. Impact of a conjugate vaccine on community-wide carriage of nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae in Alaska. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:2031–8. doi: 10.1086/425422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Gertz RE, Woodbury RL, Barkocy-Gallagher GA, Schaffner W, Lexau C, et al. Population snapshot of emergent Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in the United States, 2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1016–27. doi: 10.1086/528996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm MH, Lin J, Finkelstein JA, Pelton SI. Increase in the prevalence of the newly discovered pneumococcal serotype 6C in the nasopharynx after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:320–5. doi: 10.1086/596064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes S, Valente C, Sá-Leão R, de Lencastre H. Temporal trends and molecular epidemiology of the recently described serotype 6C of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:472–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01984-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai R, Gertz R, Beall B. Sequential multiplex PCR approach for determining capsular serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:124–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.124-131.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Pritchard DG, Cartee R, Brandao A, Brandileone M, Nahm MH. Discovery of a new capsular serotype (6C) within serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2007a;45:1225–33. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02199-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Park S, Hollingshead SK, Nahm MH. Genetic basis for the new pneumococcal serotype 6C. Infect Immun. 2007b;75:4482–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00510-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Moore M, Treanor JJ, Pelton SI, Pilishvili T, Beall B, et al. Differential effects of pneumococcal vaccines against serotypes 6A and 6C. J Infect Dis. 2008a;198:1–5. doi: 10.1086/593339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Moore MR, Bruden DL, Hyde TB, Reasonover AL, Harker-Jones M, et al. Impact of conjugate vaccine on transmission of antimicrobial-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among Alaskan children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008b;27:335–40. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318161434d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolo D, Fenoll A, Ardanuy C, Calatayud L, Cubero M, de la Campa AG, et al. Trends of invasive serotype 6C pneumococci in Spain: emergence of a new lineage. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011a;66:1712–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolo D, Ardanuy C, Calatayud L, Pallares R, Grau I, García E, et al. Characterization of invasive pneumococci of serogroup 6 from adults in Barcelona, Spain in 1994 to 2008. J Clin Microbiol. 2011b;49:2328–30. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02545-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RJ, Hennessy TW, Bulkow LR, Hammitt LL, Zulz T, Hurlburt DA, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes among Alaska Native children with high levels of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine coverage. JAMA. 2007;297:1784–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocheva AS, Jefferies JMC, Christodoulides M, Faust SN, Clarke SC. Increase in serotype 6C pneumococcal carriage, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:154–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger JD, Zulz T, Bruden D, Singleton R, Bruce MG, Bulkow L, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Alaskan children: impact of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and the role of water supply. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;J29:251–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181bdbed5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]