Abstract

Depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder are three of the four most burdensome problems in people aged under 25 years. In psychosis and depression, psychological interventions are effective, low-risk, and high-benefit approaches for patients at high risk of first-episode or early-onset disorders. We review the use of psychological interventions for early-stage bipolar disorder in patients aged 15–25 years. Because previous systematic reviews had struggled to identify information about this emerging sphere of research, we used evidence mapping to help us identify the extent, distribution, and methodological quality of evidence because the gold standard approaches were only slightly informative or appropriate. This strategy identified 29 studies in three target groups: ten studies in populations at high risk for bipolar disorder, five studies in patients with a first episode, and 14 studies in patients with early-onset bipolar disorder. Of the 20 completed studies, eight studies were randomised trials, but only two had sample sizes of more than 100 individuals. The main interventions used were family, cognitive behavioural, and interpersonal therapies. Only behavioural family therapies were tested across all of our three target groups. Although the available interventions were well adapted to the level of maturity and social environment of young people, few interventions target specific developmental psychological or physiological processes (eg, ruminative response style or delayed sleep phase), or offer detailed strategies for the management of substance use or physical health.

Introduction

Depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder are ranked as three of the four most burdensome problems worldwide in individuals aged 10–24 years.1 In psychosis and depression, early intervention strategies have been implemented to reduce disability.2–5 These programmes have begun to extend beyond individuals with illness episodes that fulfil established diagnostic criteria to include individuals from high-risk populations.6 The inclusion of these individuals is compatible with the clinical staging approach that underpins chronic disease management of other disorders such as cancer, diabetes, or ischaemic heart disease.7 A key element of clinical staging is that an individual can be placed on an illness continuum from a high-risk state (stage 0) to end-stage disease (stage 4). Interventions with a much lower risk-to-benefit ratio are offered to those individuals in the earliest stages (0–2) of any illness, with the prospect that these interventions will improve immediate outcomes and also prevent disease progression.6,8 Staging models are increasingly applied to depression and psychosis in youth mental health settings, where they are viewed as an especially useful refinement to traditional diagnosis. Staging models aid the selection of treatments for adolescents and young adults whose long-term outlook is less certain than that of adults (in terms of diagnostic stability and prediction of prognosis).6,8,9 Furthermore, the need to optimise benefits compared with risks of any interventions targeted at individuals who are in stage 0 or with subsyndromal symptoms (traditionally excluded from mental health services), and to maximise treatment acceptability for first-episode or early-onset patients (who are often ambivalent about committing to long-term medication use) has increased the interest of the health-care community in the role of psychological treatments for these patients.10–12

Since about 2005, clinicians and researchers have begun to translate staging and early-intervention models to bipolar disorder.6,8,13,14 However, this framework has not been used to explore psychological interventions for young people identified to be in the early stages of bipolar disorder. The purpose of this Review is to address this important gap in the scientific literature. We begin with a brief synopsis of staging, its application to bipolar disorder and the use of psychological therapies for bipolar disorder in clinical practice. Next, we use an evidence-mapping approach to examine the emerging scientific literature on psychological interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder. The strengths and weaknesses of different psychological interventions are highlighted.

Bipolar disorder: clinical staging and psychological therapies

Research on clinical staging indicates that in mental disorders such as psychosis, stage 0 refers to an asymptomatic but increased risk phase. Stage 1 represents subthreshold symptoms with diminished functioning. Stage 2 usually indicates a clinical state fulfilling recognised diagnostic criteria. Stages 3 and 4 represent established, severe, and persistent illness.6 The staging model is still evolving for bipolar disorder, but most advocates of staging agree that high-risk individuals are usually identified by a family history of bipolar disorder (stage 0); family history and non-specific symptoms (such as anxiety), or because they have subthreshold manic symptoms, mood instability, sometimes with a concurrent depressive episode (stage 1).6,8,13,14 Stage 2 is usually defined as the first hypomanic, manic, or mixed episode, with or without psychotic symptoms. The late stages of bipolar disorder are characterised by recurrent or chronic mood episodes accompanied by substantial functional disability. These individuals with stage 3–4 of the illness constitute most of the referrals for bipolar disorder to secondary or tertiary mental health services.6,8,13,14

The peak age of onset for bipolar disorder is 15–25 years, with 75% of first episodes occurring between 12 years and 30 years of age.15 Individuals with a late-adolescent or early-adult onset of bipolar disorder are under-represented in treatment settings and frequently have a poorer prognosis than do individuals with a later age of onset, implying that early detection and introduction of therapy might be beneficial.11,13 In the recent decades, almost all studies on bipolar disorder treatment recruited individuals outside this age range.16–18 Therefore, benefits of psychological treatments in bipolar disorder have been shown almost exclusively by randomised controlled trials RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews that have been dominated by samples of middle-aged adults with established bipolar disorder (mainly stages 3 and 4), most of whom were coprescribed mood stabilisers and other medications. At the opposite end of the age range, a small number of studies19–21 on interventions for children aged between 5 and 11 years diagnosed with paediatric or juvenile bipolar disorder have been reported. Since juvenile bipolar disorder is not a universally accepted diagnosis,22 and more pertinently, not necessarily an antecedent of adult-type bipolar disorder,23,24 the relevance of these studies to stage-appropriate interventions for young adults is unclear. Nevertheless, studies in children and in adults suggest that psychological therapies can play an important role in the improvement of outcomes of bipolar disorder. Three posthoc analyses of reported RCTs18,25,26 show indirectly that psychological therapy might be more effective in earlyonset bipolar disorder or young adults. However, these studies do not address the potential benefits of therapy to high-risk or subsyndromal cases of bipolar disorder (stages 0–1), or to first-episode cases in young people (stage 2). Four systematic reviews27–30 of psychological interventions for mixed populations of children, adolescents, young adults, and those people at high risk or having already had a first episode of bipolar disorder, have identified 0–5 completed and two ongoing studies at the time of writing. These findings might suggest that only few investigations are undertaken in this area. Alternatively, the search strategies or methods employed might have failed to capture all the data available from the wide range of settings where young people with recent-onset bipolar disorder or at high risk for bipolar disorder might have come into contact with different health-care systems. Many studies13 speculate that psychological interventions can play a key role in the management of the earliest stages of bipolar disorder, but what age-appropriate or stage-appropriate therapies are available for adolescents and young adults in stages 0–2 of bipolar disorder and what benefits might be expected remains unclear. One way to address these issues is to use evidence mapping.31 This method is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses approach to systematic enquiry32 but allows for a wider inclusion of ongoing studies and grey literature (panel 1, figure 1).

Panel 1. Development of the research questions.

We consulted international experts in the specialties of early intervention for mental disorders, psychological therapies, and mood disorders who identified the research questions a priori. The experts agreed on the parameters for the evidence map, including the key questions and the definitions to be used.

What evidence exists regarding the use of psychological interventions for the earliest stages of bipolar disorder?

Psychological interventions for bipolar disorder were operationalised in the following way: any non-pharmacological intervention delivered in individual, family, multifamily, or group settings, incorporating strategies to prevent or delay the onset of a first bipolar disorder episode (depression, hypomania, or mania), to improve the wellbeing of the off spring of parents with bipolar disorder, to relieve symptoms of mood disturbance, to improve functional (including vocational) outcomes.

For inclusion in the mapping exercise, the intervention had to be described in an original study document, data report, review article, or published manual (available as text or online) in sufficient detail that an experienced therapist could reproduce the intervention. As such, we excluded generic approaches that were only briefly reported (eg, support or supportive psychoeducation) and interventions that did not specify the number or content of sessions or describe specific components of the intervention. Integrated or multicomponent interventions, such as those offered in early intervention or youth mental health services, were included if data were available for cases of bipolar disorder or affective psychosis. These transdiagnostic programmes were also examined to identify if any specific modifications were made to meet the needs of our target subgroups.

The study had to report symptomatic or functional outcomes, or have another clearly stated primary outcome measure (eg, employment status for vocational interventions). Studies that investigated interventions for comorbidities (eg, anxiety, substance use) were eligible if bipolar disorder symptom outcomes were also reported.

Early stage bipolar disorder was operationalised as individuals at increased risk for bipolar disorder, with a first episode of bipolar disorder or with early onset bipolar disorder. Consensus criteria were as follows:

Increased risk for bipolar disorder: studies of children and adolescents up to the age of 18 years (individuals aged >18 years are usually directed to adult clinical services) could be included if the study had recorded the absence or presence of any symptoms at baseline, and reported clinical or functional outcomes postintervention, or the rates of transition to bipolar disorder.

First episode bipolar disorder: studies were included if they represented a planned examination of first episode cases (post-hoc analyses of heterogeneous samples were excluded) and included individuals aged 15–25 years (or if data for this age group were reported separately or could be extracted or obtained).

- Early onset bipolar disorder: reports on early onset depression, psychosis, or early intervention, usually set an upper age limit of 30 years with eligible participants having had only 1–2 prior illness episodes. Using a similar approach, we included studies that represented a planned examination of adolescents or young adults with recent onset mental disorder and either of the following criteria:

- The mean age of participants with bipolar disorder was 12 years or more (selected as a proxy for puberty and the age at which adult rather than juvenile diagnostic criteria are usually applied) and data were available on participants who had their first bipolar disorder episode between the ages of 15 and 25 years.

- The mean age of participants was younger than 30 years, and data were available on cases who had their first bipolar disorder episode between the ages of 15 and 25 years.

Studies could include cases with psychotic symptoms, affective psychosis, or schizoaffective disorders. The reason for including both first episode and early onset categories was because of variations in how these terms are applied in the scientific literature. For example, if mania or hypomania was the first mood episode, many studies classified the case as first episode bipolar disorder. However, other studies described these cases as early onset bipolar disorder because many individuals had a depressive mood episode before their first hypomanic or manic episode.

Based on the emerging evidence, what are the most promising avenues for research and what gaps exist in our understanding?

To gain a detailed picture of the state of the art, the following criteria were agreed upon:

Emerging evidence encompassed data from ongoing and completed studies including masked or unmasked randomised controlled trials, pseudorandomised and clinical controlled trials (abbreviated as CCTs), and case series and small scale open studies.

Eligible publications included journal articles, conference proceedings and abstracts, clinical trials, and thesis registries that were written in English, French, Italian, Spanish, or German.

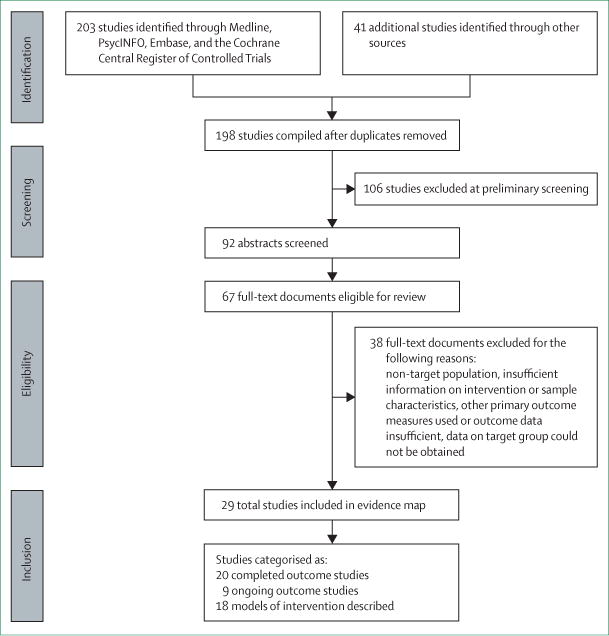

Figure 1.

Flowchart for study selection

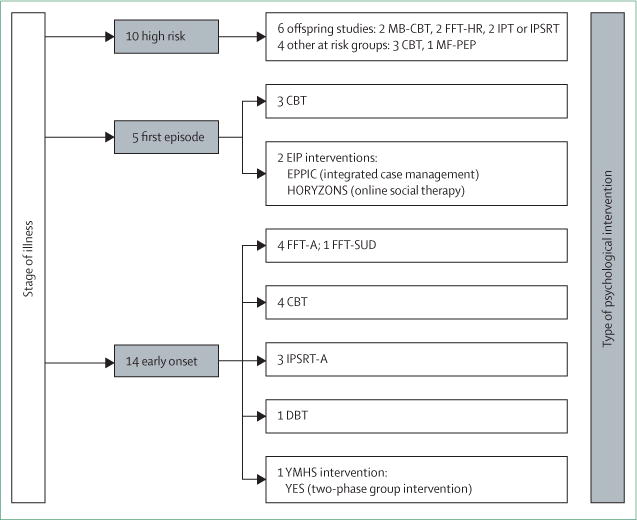

Overview of therapy models

18 models of interventions described in the scientific literature have been applied to the three target populations included in this Review. The therapies are evenly divided between high-risk,33,38 first-episode,39–43 and early-onset (usually adolescent) populations.44–50

To compare interventions, we reviewed the published descriptions to establish whether a particular strategy (eg, psychoeducation) was given as a clearly defined module (usually in several sessions) that was integral to the intervention, if techniques were specifically included in the description of the therapy, or if only brief details were provided about the need to address a target symptom or problem. The main components of each model are summarised in table 1 and in the appendix.

Table 1.

Key components of reported psychological therapies used for individuals with high risk, first episode, or early onset bipolar disorder

| Number of sessions |

Therapy components used in adults with established bipolar disorder

|

Theory driven components |

Additional components or modifications of adult therapies

|

Observations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psycho- education |

Individual*, group, or family problem solving |

Relapse prevention techniques (general) |

Risk factors for relapse

|

Family sessions |

Cognitive and emotional regulation |

Developmental adaptations |

Social functioning and relationships |

Educational and vocational functioning |

Communi- cation training |

|||||

| Medication adherence |

Social rhythms |

Substance misuse |

||||||||||||

|

High risk for bipolar disorder

| ||||||||||||||

| Group CBT (Pfennig)33 | 14 | +++ | +++ (group only) | ++ | .. | ++ | .. | .. | ++ | + | + | .. | .. | Group intervention adapted from adult CBT manuals and approaches for early-onset psychosis; specific components include education, stress management, mindfulness and cognitive techniques |

| CBT-R (Scott)34 | 24 | ++ | ++ | ++ | .. | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | Three-phase model with unique components to target regulation of developmental processes (eg, rumination and circadian abnormalities), physical activity, and general health |

| MB-CBT (DelBello)35 | 12 | + | ++ (group only) | + | .. | .. | .. | .. | +++ | ++ | .. | .. | .. | Group therapy using CBT and mindfulness techniques (eg, body scanning, meditation); one study targets anxiety and the other study targets mood dysregulation |

| FFT-HR (Miklowitz)36 | 12 | +++ | +++ (family only) | +++ | .. | .. | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | +++ | Manualised intervention partly derived from FFT-A with additional modules for comorbidities (eg, anxiety disorders) |

| IPSRT (Goldstein)37 | 12 | ++ | ++ | ++ | .. | +++ | .. | .. | .. | ++ | ++ | + | + | 12 sessions in 6 months that target social rhythms and use age-adapted techniques for interpersonal problems |

| MF-PEP (Nadkarni)38 | 8 | +++ | +++ (family and group only) | .. | .. | .. | .. | +++ | +++ | + | + | .. | + | 90 min group sessions for parents and children that emphasise education, social support, CBT, and family interventions |

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

First episode of bipolar disorder

| ||||||||||||||

| CBT (Jones)39 | 14–18 | + | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | .. | .. | + | .. | .. | .. | .. | Standard CBT approach as applied to adults with established bipolar disorder; limited adaptations such as home based CBT sessions |

| CBT-based, multimodal therapy (Macneil)40 | 24 or more | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | Manualised intervention for use with bipolar disorder with or without psychosis; CBT and recovery focus, plus up to eight additional modules (eg, to target substance abuse) |

| CB model-TEAMS (Searson)41 | 12 | +++ | ++ | + | .. | .. | .. | .. | + | .. | ++ | .. | .. | CBT approach to help clientwith bipolar disorder to identify extreme appraisals of internal states and develop more effective approaches to mood control |

| HORYZONS (Alvarez-Jimenez)42 | Varies; open access | +++ | + | +++ | .. | .. | .. | .. | ++ | + | +++ | + | ++ | Online intervention for psychosis that integrates several components, predominantly uses CBT strategies but also peer-to-peer networking |

| EPPIC integrated intervention (Conus)43 | Varies; input for about 2 years | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | .. | + | + | .. | +++ | + | ++ | .. | Multidisciplinary case management of young people with any first-episode psychotic disorder |

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

Early-onset bipolar disorder

| ||||||||||||||

| SR-CBT (Fowler)44 | 12 | + | +++ | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | + | .. | +++ | ++ | +++ | CBT aimed at the improvement of vocational outcomes for any psychotic disorder |

| CBTpA‡ (Browning)45 | ~20 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | .. | + | .. | +++ | ++ | + | .. | .. | Standard CBT for adult psychosis with some modifications for adolescent inpatients |

| DBT (Goldstein)46 | 36 | ++ | ++ (individual and family) | + | + | ++ | .. | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | Therapy based on DBT used with adults and adolescents who engage in self-harm; includes family skills training and individual therapy with or without skills coaching by telephone |

| FFT-A (Miklowitz)47 | 21 | ++ | +++ (family only) | + | + | + | + | +++ | .. | +++ | + | ++ | +++ | Manualised intervention using the main elements of adult FFT with additional age-specific adaptations and the option of some individual sessions |

| FFT-SUD (Goldstein)48 | 21 | +++ | ++ (family), + (individual) | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | .. | +++ | + | + | +++ | FFT-A with substance-specific modules and an emphasis on adherence |

| IPSRT-A (Hlastala)49 | 21 | + | + | ++ | + | +++ | + | + | .. | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | Similar to the adult IPSRT model, but considersthe school environment and uses self-monitoring instruments adapted for teenagers |

| YES (Gehue)50 | 16 | ++ | ++ (group) | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | Group intervention for young people referred to mental health services; two phase programme: eight sessionstargeting cognitive coping strategies and social functioning, and eight sessions that focus on physical health and developmental physiology (eg, circadian rhythms) |

CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. CBTpA=CBT for psychosis in adolescents. CBT-R=CBT-regulation. MB-CBT-C=mindfulness-based CBT Children. SR-CBT=social recovery-CBTTEAMS=Thinking Effectively About Mood Swings. DBT=dialectical behaviour therapy. EPPIC=Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre. FFT=family focused treatment. FFT-A=FFT-adolescent. FFT-HR=FFT-high risk. FFT-SUD=FFT-substance use disorders. IPSRT=interpersonal social rhythms therapy. IPSRT-A=IPSRT-adolescents. MF-PEP=multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy. YES=Youth Early-intervention Study +++Module described in intervention manual or publications. ++Techniques specifically included in the therapy. +Mentioned as a therapy goal, but limited detail provided about the strategy. *Problem-solving interventions focused on individual work unless otherwise indicated. †Although social rhythm dysregulation is a core component of the theoretical model of IPSRT and CBT-R, other therapies incorporate sessions on social rhythms or circadian rhythms for relapse prevention. ‡The study offered CBTpA or family therapy, but the description of the adaptation of family therapy for adolescents with psychosis did not meet the inclusion criteria for the evidence map.

Most therapies were described as interventions specific for bipolar disorder, but five therapies (two for patients with first episode and three for patients with early onset) were aimed at young people with affective and non-affective psychoses (online interventions such as so-called HORYZONS,42 Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre,43 social recovery cognitive behavioural therapy [CBT],44 CBT for psychosis for adolescents45) or other transdiagnostic populations (Youth Early-intervention Study50). The number of sessions offered varied between eight and 36 and depended mostly on the type of therapy being provided rather than the stage of illness. Whatever the underlying theoretical model used, almost all interventions incorporate psychoeducation and problem solving, symptom-management or relapseprevention strategies, and some advice on sleep, social rhythms and cognitive regulation. The adaptation of adult interventions for youth populations mainly focuses on making the material and aspects of the intervention accessible to the age range being treated and on considerations of the social context (eg, focusing on peer relationships in school). There are fewer modifications that addressed specific needs of young people or other normative developmental processes that could increase the likelihood of onset of bipolar disorder in susceptible individuals. An example would be interventions that improve sleep patterns: although simple sleep hygiene or sleep regulation are frequently described, few therapies use particular strategies that directly target specific sleep or circadian disruptions (such as delayed sleep phase) that are more common in younger compared to older adults in general and also show a particular association with emerging bipolar disorder.34,51

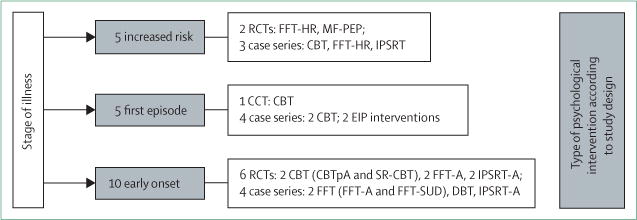

Overview of outcomes

As shown in table 2 and figure 2, the evidence map shows that psychological interventions have been used in 29 completed or ongoing intervention studies. However, only 20 are completed studies (figure 3) and just eight are completed RCTs. If we restricted the review to RCTs meeting more stringent standards for inclusion (such as applied for many systematic reviews), then only three studies would be eligible.

Table 2.

Evidence map of studies of psychological therapies used for high risk, first-episode and early-onset bipolar disorder

| Location | Sample | Number and description of participants | Study design | Type of therapy and duration | Comparison group | Duration of follow-up (months) | Outcomes or trial identifiers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reported studies for individuals at high risk for bipolar disorder

| ||||||||

| Nadkarni (2010)38 | Ohio State University, USA | Children with mood disorders: bipolar spectrum disorder, depressive spectrum disorder with transient manic symptoms, depressive spectrum disorder only | 165 total participants (9–11 years of age) with 50 individuals at high risk for bipolar disorder; 37 participants with depressive spectrum disorder and transient manic symptoms, 13 participants with depressive spectrum disorder only | RCT | Multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy for 8 weeks | Waiting list control | 18 | Conversion rates to bipolar spectrum disorder were 45% in the waiting list control group and 12% in the multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy group; family history of bipolar disorder, ongoing transient manic symptoms, and lower baseline functioning were associated with a greater likelihood of conversion to bipolar spectrum disorder; subanalyses have low statistical power |

| Miklowitz (2011)36 | Universities of Stanford and Colorado, specialist clinics, USA | Offspring of parent with bipolar disorder: children or adolescents with active mood symptoms in the past month | 13 participants (9–16 years of age, mean 13·4 years); four girls, nine boys | CS | FFT-HR for 4 months | .. | 12 | Young people who received FFT showed significant improvements in depression, hypomania, and global functioning; most families were adherent to the treatment protocol |

| Miklowitz (2013)52 | Universities of Stanford and Colorado, specialist clinics, USA | Individuals with prodromal symptoms (depressive, subthreshold manic, or hypomanic) and a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder | 40 individuals (9–17 years of age, mean 12·3 years); 20 received FFT, 20 TAU; 17 girls and 23 boys | RCT | FFT-HR for 4 months | TAU plus one psychoeducation session | 24 | Individuals who received FFT-HR showed significantly greater pretreatment to post-treatment improvements with better outcomes than controls for depression, time to recovery, and duration of remission; outcomes for participants from families with low expressed emotion were better than for high expressed emotion families |

| Goldstein (2014)37 | University of Pittsburgh specialist clinics and other research study participants, USA | Family history of bipolar disorder; at baseline, seven of 13 individuals had more than one Axis-I diagnosis (three individuals with depression, three with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) | 19 participants (13–28 years of age, mean 15 years) were offered IPSRT; outcomes reported on 13 participants who had attended one or more sessions | CS | IPSRT for 6 months | .. | 6 | Families were satisfied with the intervention. The 13 participants attended about 50% of the sessions; significant changes were reported in sleep and circadian patterns; no significant effect on severity of mood symptoms was noted; four individuals met criteria for depression at follow-up |

| French (2014)53 | University of Manchester, UK | Individuals identified as having increased risk for bipolar disorder and showed mood swings | Ten individuals | CS | CBT for 3 months | .. | 6 | Improvements in depression, self-esteem, functioning, but less improvement in manic symptoms |

|

| ||||||||

|

Ongoing studies for individuals at high risk for bipolar disorder

| ||||||||

| Verdeli (2009)54 | New York State Psychiatric Institute, USA | Offspring of parent with bipolar disorder | Target of 60 participants (12–17 years of age) | RCT | Interpersonal therapy for 12 weeks | Educational clinical monitoring (4–6 sessions) | 18 | NCT00338806 (very low recruitment, results not yet published; Verdeli, personal communication) |

| Scott (2010)34 | University of Newcastle, UK | Young people with mood disorders meeting criteria for being at risk of bipolar disorder | Target of 150 participants (16–25 years of age); target of 15 participants for the CBT-R pilot study | CS | Individual CBT-R for 24 weeks | .. | 18 | PB-PG-0609-16166 |

| Pfennig (2014)33,55 | University of Dresden and four other centres, Germany | Individuals with family history of affective or schizoaffective disorders, affective symptoms, and psychosocial impairment | Target of 100 individuals (15–30 years of age) | RCT | Group CBT for 14 weeks | Unstructured group | 18 | DRKS00000444 |

| DelBello (2014)35 | University of Cincinnati, USA | Offspring with mood dysregulation of parent with bipolar disorder | Target of 12 participants (10–17 years of age) | CS | MB-CBT-C group for 12 weeks | ·· | 3 | NCT02120937 |

| DelBello (2014)56 | University of Cincinnati, USA | Offspring with anxiety disorder of parent with bipolar disorder | Target of about 40 participants (10–17 years of age) | RCT | MB-CBT-C group for 12 weeks | Waiting list control plus educational materials | 3 | NCT02090595; conference report57 of ten cases with mean age of about 13 years showed significant decreases in anxiety with associated changes in mindfulness and emotional regulation; non-significant trends for reductions in depressive and manic symptoms |

|

| ||||||||

|

Reported studies of individuals with first episode bipolar disorder

| ||||||||

| Jones (2008)39 | Secondary Mental Health Services in the NHS England, Lancaster, UK | First diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1 | Seven participants (18–65 years of age); two male individuals were younger than 26 years of age | CS | CBT for 6 months | ·· | 6 | Improvements in detection of early prodromal signs; decrease in hopelessness scores |

| Conus (2010)43 | Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Australia | Individuals with first-episode mania and psychotic symptoms; after stabilisation, diagnostic review identified 87 individuals with bipolar disorder and 21 individuals with schizomania | 108 total individuals, 87 with bipolar disorder; 73 individuals aged 15–25 years; 39 women, 48 men | CS | Integrated intervention and medication for 18 months | ·· | 12 | 26 individuals (30%) with bipolar disorder did not complete therapy; compared to schizomania, individuals with bipolar disorders showed significantly better functioning and fewer negative symptoms |

| Searson (2012)41 | Secondary Mental Health Services in the NHS England, Manchester, UK | First diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1 or 2 | Seven individuals (aged 23–44 years); one 23-year-old woman meeting criteria | CS | CBT (Thinking Effectively About Mood Swings) for 3 months | ·· | 6 | Improvements in symptoms (depression), key cognition processes (self-criticism), and psychosocial functioning |

| Alverez-Jimenez (2012)42 | Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre: HORYZONS, Australia | First psychotic episode; <6 months of antipsychotic treatment before entry to Early Psychosis Prevention & Intervention Centre and remission of positive symptoms | 20 participants (15–25 years of age, mean ~20 years); two individuals with affective psychosis | CS | Online intervention | ·· | 1 | No dropouts reported; 70% of individuals participated for ≥3 weeks and 95% used the social networking features; significant reductions in depressive symptoms |

| Macneil (2012)40 | Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Australia | First manic episode with psychotic features | 40 participants (15–25 years of age, mean ~22 years); CBT=20, TAU=20; CBT group=seven women, 13 men | Non-blind CCT | CBT and TAU for 18 months | TAU=case management; individual and family input, and medication | 18 | Both groups improved; intervention group showed significantly better outcomes than controls on depression, global clinical improvement and functioning; no group differences in mania or relapses |

|

| ||||||||

|

Reported studies for individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder

| ||||||||

| Miklowitz (2006)36 | University of Colorado specialist clinic, USA | Recent episode of mania, mixed state, or depression | 20 participants (13–17 years of age, mean ~15 years) | CS | FFT-A for nine months | ·· | 18 | Significant reductions in total symptoms, depressive symptoms and problem behaviours; better outcomes for families with low expressed emotion than families with high expressed emotions |

| Goldstein (2007)46 | University of Pittsburgh specialist clinic, USA | Acute manic, mixed, or depressive episode in the three months preceding study entry | 10 participants (14–18 years of age) offered DBT, nine of whom attended | CS | DBT for 12 months | ·· | 12 | DBT was highly acceptable; significant changes noted in depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and emotional regulation |

| Miklowitz (2008)57 | Universities of Colorado and Pittsburgh specialist clinics, USA | Bipolar disorder 1, 2, or not otherwise specified with a mood disorder episode in the previous 3 months | 58 participants (12–17 years of age, mean of 15 years); FFT=30, enhanced care=28 | RCT | FFT-A for 9 months | TAU=enhanced care | 24 | FFT-A recovered 7 weeks earlier from the index depression than TAU group (hazard ratio 1.85); no group differences in manic symptoms or overall relapse rates |

| Fowler (2009)44 | Secondary mental health services in the NHS, UK | Diagnosis of non-affective or affective psychosis (eg, bipolar disorder or psychotic depression) | 77 participants (aged 18–52 years); 27 participants had affective psychosis and onset aged 15–25 years; CBT=12, TAU=15 | RCT | SR-CBT for 6 months | TAU=case management | ~9 | In the affective psychosis group, both CBT and control cases improved; effects greater but not significant in the CBT group for anxiety ratings and beliefs about the self |

| Hlastala (2010)49 | Seattle Children’s Hospital outpatient and inpatient psychiatry, USA | Bipolar spectrum disorder | 15 individuals screened (mean age ~16 years); 12 participants received IPSRT for adolescents | CS | IPSRT for adolescents for 6 months | ·· | Not reported | High adherence to therapy (97% sessions attended) with significant changes reported in symptoms and functioning |

| Hlastala (2010)58 | Seattle Children’s Hospital outpatient and inpatient psychiatry, USA | Bipolar spectrum disorder | 17 participants (aged 14–19 years); IPSRT for adolescents=12, TAU=5; nine girls and eight boys | RCT | IPSRT for adolescents for 9 months | TAU (1·5 h of psychoeducation | 5 | Significant improvements in psychiatric symptoms, manic and depressive symptoms, global, social and interpersonal functioning |

| Browning (2013)45 | Institute of Psychiatry, London specialist inpatient unit for adolescents, UK | Inpatients with ICD-10 psychotic disorder allocated sequentially to three interventions | 30 participants (aged 14–17 years); eight with bipolar disorder or affective psychosis | RCT | CBTpA or family therapy 10–12 weeks | TAU | 3 | CBTpA (or family therapy) was associated with greater reductions in symptoms, functioning, and higher satisfaction |

| Goldstein (2014)48 | Western Psychiatric Institute specialist clinic, Canada | Diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1, 2, or not otherwise specified and a diagnosis of alcohol or cannabis abuse or dependence; symptom exacerbation in the previous 3 months | Ten participants (aged 13–18 years, mean 16·9 years); seven girls, three boys | CS | FFT for substance use disorders plus medication for 9 months | ·· | 6 | Data for six individuals who completed mid-treatment assessment showed reductions in mood symptoms, particularly depression and improved global functioning, but only a modest decrease in substance use |

| Miklowitz (2014)59 | Universities of Colorado, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital specialist clinics, USA | Bipolar 1 or 2 with a manic, mixed, hypomanic or depressive episode within the previous 3 months | 145 participants (aged 12–18 years, mean 15·6 years); FFT=72, TAU=73; 79 girls, 76 boys | RCT | FFT-A for 9 months | TAU=enhanced care | 24 | 2 years of FFT and enhanced care did not show any differences in time to recovery or recurrence, nor in the percentage of time healthy; compared with controls, FFT-A showed greater reductions in severity of and in weeks without (hypo)manic symptoms |

| Inder (2014)60 | University of Otago local health services and bipolar disorder support network, New Zealand | Diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1, 2, or not otherwise specified | 100 participants (15–36 years of age; 47 participants aged <26 years); IPSRT=26, TAU=21 | RCT | IPSRT-A sessions for 18 months | Specialist supportive care (TAU and supportive counselling) | 36 | Depressive and manic symptoms, and social functioning improved over time; no significant differences between therapies |

|

| ||||||||

|

Ongoing studies for individuals with early onset bipolar disorder

| ||||||||

| Henin (2007)61 | Massachusetts General Hospital, USA | Diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1, 2, or not otherwise specified | Target of 40 participants (aged 18–24 years) | RCT | CBT for 14 weeks | TAU | ~9 | NCT01176825; trial recruitment and follow-up reported as completed |

| Gehue (2012)50 | University of Sydney, Brain and Mind Research Institute, Australia | Young people with psychotic, mood or anxiety disorders, and social or vocational impairment; randomised to begin with Youth Early Intervention Study I or II | Target of 120 participants (aged 15–25 years); 25 individuals with bipolar disorder | RCT | Youth Early–Intervention Study for 16 weeks (8 weeks Youth Early Intervention Study I then II, or vice versa) | Crossover design | 12 | ACTR1262400175673; recruitment completed, interventions and follow-up ongoing |

| Sharma (2014)62 | University of Newcastle: Child and Adolescent services, UK | Diagnosis of bipolar disorder 1, 2, or not otherwise specified; currently in remission and living with family | Target of 66 participants (range 11–18 years of age) | RCT | FFT-A for adolescents for 6 months | TAU | 6 | PB-PG-0212-27060; recruitment has commenced |

| Schwanner (2014)63 | University of Edinburgh, UK | Early-onset first or second episode of bipolar disorder in adolescents | Target of 20 participants | Pilot RCT | CBT | TAU | 6 | 51765/1 (database of the University of Edinburgh) |

No ongoing studies of individuals with first episode were detected. TAU=treatment as usual. CS=case series. CCT=controlled clinical trial. RCT=randomised controlled trial. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. CBTpA=CBT for psychosis in adolescents. CBT-R=CBT-regulation. MB-CBT-C=mindfulness-based CBT children. SR-CBT=social recovery-CBT. DBT=dialectical behaviour therapy. FFT=family focused treatment. FFT-A=FFT-adolescent. FFT-HR=FFT-high risk. IPSRT=Interpersonal Social Rhythms Therapy.

Figure 2. Evidence map of all 29 studies of psychological interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder.

CBT=cognitive behaviour therapy. CBTpA=CBT for psychosis in adolescents. CBT-R=CBT-regulation. MB-CBT-C=mindfulness-based CBT children. SR-CBT=social recovery-CBT. TEAMS=Thinking Effectively About Mood Swings. DBT=dialectical behaviour therapy. EPPIC=Early Psychosis Prevention & Intervention Centre. FFT=family focused treatment. FFT-A=FFT-adolescent. FFT-HR=FFT-high risk. FFT-SUD=FFT-substance use disorders. IPSRT=Interpersonal Social Rhythms Therapy. IPSRT-A=IPSRT-adolescents. MF-PEP= multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy. YES=Youth Early Intervention Study. YMHS=Youth Mental Health Service.

Figure 3. Evidence map of the 20 completed studies of psychological interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder.

CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. CBTpa=CBT for psychosis in adolescents. CCT=controlled clinical trial. DBT=dialectical behavioural therapy. FFT-A= family focused therapy-adolescents. FFT-HR=FFT-high risk. FFT-SUD=FFT-substance use disorder. IPSRT-A=Interpersonal Social Rhythms Therapy-adolescents. EIP=early intervention in psychosis. RCT=randomised controlled trial. SR-CBT=social recovery-CBT

Young people at high risk for developing bipolar disorder

Ten studies of individuals at high risk for developing bipolar disorder were identified; five of these studies (three case series and two RCTs) had been completed. The RCT from Nadkarni and Fristad38 is the only study that provides data for the transition from a high-risk status to the development of bipolar disorder. The sample included 50 individuals (from a sample of 165 people) who were deemed to be at high risk of developing bipolar disorder because of a depressive spectrum disorder with or without transient manic-like symptoms. Those patients who received the multifamily psychoeducation intervention were significantly less likely to meet criteria for a bipolar spectrum disorder at follow-up than were those patients allocated to the control group (12% vs 45%).

Two studies36,52 that used the family focused treatment-high risk (FFT-HR) intervention in individuals who had at least one biological parent with bipolar disorder have been reported. The initial case series36 included 13 participants (five of them did not take any drugs), with a mean age of about 13 years. 85% of families were adherent to the treatment protocol and significant reductions were noted in depressive (effect size [ES] 1·77) and manic (0·51) symptoms after 12 months. Significant functional improvements were also noted.

The RCT52 of FFT-HR is the first masked RCT of a psychosocial intervention for young people at risk for bipolar disorder. The 40 participants (mean age of about 12 years; 40% not receiving medication) were randomly allocated to the FFT-HR intervention (12 sessions of psychoeducation, communication training, and problem-solving skills) or to a control group that received brief psychoeducation (1–2 family education sessions). The FFT-HR group showed a faster recovery from mood symptoms and longer periods of remission than did the control group; medication status did not influence outcomes.

The case series that used interpersonal social rhythms therapy (IPSRT)37 and CBT53 represent small-scale studies with mixed outcomes.39,40 For example, IPSRT showed a strong trend in improving the sleep profile of young adults, but showed no significant benefits for mood disorders (eg, three patients met depression criteria at baseline and four patients met depression criteria at follow-up).37 CBT showed only weak effects on manic symptoms.53

Of the five ongoing studies,33–35,54–56 only one study64 has reported any interim outcome data. In that study, ten adolescents who were offered mindfulness-based CBT showed significant reductions in anxiety and associated changes in emotional regulation, but non-significant decreases in depressive or manic symptoms.

Individuals with a first episode of bipolar disorder

Five studies have been reported in individuals with first episode bipolar disorder: four case series39,41–43 and one clinical controlled trial (CCT)40. In two studies,39,41 CBT was provided in adult mental health settings, whereas in the other three studies,40,42,43 CBT was given as an early intervention in psychosis settings.

Only three of 14 patients who had first episodes in the two reported case series of CBT were younger than 26 years. The main findings for the Think Effectively About Mood Swings (TEAMS) approach were reductions in depressive symptoms (ES 2·35) and manic symptoms (0·89) along with cognitive and functional improvements.41 The other CBT study39 reported symptom reductions throughout treatment and follow-up, together with significant improvements in coping with early warning signs of depressive (ES 1·97) and manic episodes (1·62).

The open feasibility study by Alvarez-Jimenez and colleagues42 is unique in its use of the internet as the mode of delivery for individualised interventions. Only two of 20 patients had affective psychoses, but as with the whole sample of patients, they showed high uptake to the programme, improvements in social connectedness, and significant reductions in depressive symptoms.

Conus and colleagues43 published a 12 month follow-up of 108 individuals (mean age ~22 years; 55% male) who presented with psychotic mania. Patients were offered 18 months of integrated, individualised case management with various psychosocial and pharmacological treatments. 12 months after treatment initiation, clinical and functional outcomes were better in patients with bipolar disorder than they were in patients with schizoaffective disorder. However, 30% of patients in the bipolar disorder group were not available at the 18 month follow-up, possibly due to service disengagement.

One CCT40 offered therapy to 40 individuals with first-episode mania who were concurrently enrolled in a large open-label medication trial. 20 participants identified as controls (who received fewer than four of eight therapy modules) were matched on key demographic characteristics with participants who completed four or more modules (intervention group). Control participants received the same total number of health system contacts interactions with health-care professionals during the 18 months. Improvements in depressive symptoms, illness severity, and functioning were significantly greater in the intervention group, although manic symptoms and overall relapse rates were similar across groups.

Individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder

Of the 14 completed44–49,57–60 or ongoing50,61–63 studies, five studies used FFT (two case series were completed; two RCTs were completed and one RCT was ongoing), four studies used CBT (two studies were completed and two RCTs were ongoing), three studies used IPSRT (one case series and two RCTs were completed), one case series used dialectical behavioural therapy, and one ongoing RCT is using a two-phase group intervention (Youth Early-intervention Study). Outcomes are summarised only for the completed studies.

The case series of FFT for adolescents by Miklowitz and colleagues47 included 20 individuals (mean age ~15 years). Significant reductions were shown in total mood symptoms (ES 1·05) and depressive symptoms (0·87), and also in problem behaviours. Notably, particularly strong reductions in depressive symptoms were reported in the 14 participants from families with high levels of expressed emotion.

The case series48 of FFT for substance use disorders consisted of ten patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid alcohol or cannabis misuse (mean age ~17 years). Two individuals completed 21 sessions of FFT for substance use disorders and four other individuals had mid-therapy assessments. These individuals showed significant improvements in mood symptoms, particularly in depression, but only slight reductions in substance use.

The first RCT57 of FFT for adolescents included 58 individuals (mean age ~15 years), of whom 38 were diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder. No differences between adolescents with or without FFT were shown for bipolar disorder relapse rates, time to recovery from symptoms of mania, or time spent in manic episodes. However, those patients allocated to FFT for adolescents recovered from depression significantly earlier (difference of about 7 weeks; hazard ratio 1·85) than did those patients in the control group. In the second, multicentre RCT59 of similar design with 145 patients, FFT for adolescents had no effect on the time to recovery or episode recurrence, or on the percentage of time healthy, as compared with the control intervention. However, FFT for adolescents was associated with less severe manic symptoms during the second year of intervention, compared to enhanced care.

The case series49 that used IPSRT for adolescents included 12 individuals (mean age ~16 years) of whom nine completed 20 sessions of planned interventions. These interventions significantly reduced depressive (ES 0·77) and manic (0·97) symptoms. The small-scale open RCT58 of 17 new participants (12 participants received IPSRT for adolescents and five received treatment as usual) showed significant differences between groups in ES for changes in depressive (1·8 for IPSRT for adolescents vs 1·3 for treatment as usual) and manic symptoms (1·2 vs 0·5), together with improved social and interpersonal functioning.

Inder and colleagues60 randomised 100 individuals with bipolar 1 and 2 disorders (47 patients were aged <26 years) to receive either IPRST or specialist supportive care. Both groups of patients showed improvements in depressive and manic symptoms, and social functioning. However, no significant differences were found between therapies.

A case series46 that used dialectic behavioural therapy recruited ten individuals (mean age ~16 years) of whom nine individuals attended at least 90% of scheduled sessions. Significant reductions were noted for depressive (ES 0·7) but not for manic symptoms. Reductions in suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour, and emotional dysregulation were also noted.

The RCT by Fowler and colleagues44 used Social Recovery CBT that targeted vocational outcomes in 50 individuals with recent-onset psychosis. Subanalyses of 27 patients with affective psychoses, 12 of whom received Social Recovery CBT and 15 of whom received therapy as usual, showed that Social Recovery CBT was associated with significant reductions in anxiety and modifi cation of beliefs about the self.

An RCT45 of 30 adolescents, eight of whom had bipolar disorder or affective psychoses, who were admitted to a psychosis inpatient unit reported that patients allocated to CBT for psychosis in adolescents or family therapy showed significantly greater improvements in symptoms (ES 0·6) and functioning (0·2) compared with usual treatment alone. Post-therapy outcomes for CBT for psychosis in adolescents and family therapy were similar, with high levels of treatment satisfaction.

Discussion

The clinical imperative

We wrote this Review to explore whether the increased interest by the scientific and medical communities in the early identification of young people at risk of, or with recent onset of, bipolar disorder was matched by the development of low-risk, high-benefit interventions for the earliest stages of illness. We focused on psychological rather than pharmacological interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder for two key reasons. First, young people are often ambivalent about taking medications that are prescribed for mental disorders even when they meet diagnostic criteria. Young people are even less likely to engage with such treatments if they have subsyndromal symptoms or increased levels of risk in the development of bipolar disorder but no certainty that such a transition will occur.10,11,65 Second, many clinicians, even if they have identified individuals with early-stage bipolar disorder, are reluctant to offer the medications that are routinely prescribed for older adults or established cases of bipolar disorder because of the side-effect and adverse-effect profile.66 Thus, the exploration of alternative approaches, especially evidence based psychological interventions, is particularly important because young people are at the greatest risk of delayed treatment.13,66

Evidence mapping

Evidence mapping was used because it allows investigators to identify the extent, distribution, and methodological quality of data whenever the gold standard approaches of systematic reviews and meta-analyses are less informative or appropriate than usual.31 Our map identified more than four times as many studies of the early stages of bipolar disorder as the previous systematic reviews in the specialty (29 studies as compared with zero to seven studies identified in the systematic reviews)27–30. However, comparison with existing evidence maps of psychosis and depression indicates that work in bipolar disorder is lagging behind these areas of investigation. For example, our Review identified only eight completed RCTs of psychological interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder, compared with 17 RCTs in psychosis and 43 RCTs in depression.4,5

One challenge for our evidence map was that most data for individuals at high risk for bipolar disorder or with first-episode or early-onset bipolar disorder did not arise from studies that had applied a recognised clinical staging model to select patients. The lack of consistency in how high risk or other early onset subpopulations were defined means that it is not yet possible to identify any differential effects of a specific intervention used for different stages of bipolar disorder, nor to differentiate clearly between any benefits associated with different therapies offered at a particular stage of illness. The increasing understanding and application of staging models in bipolar disorder could allow these issues to be clarified. We encourage clinicians and investigators to provide more detailed information about different subtypes of patients and longitudinal illness trajectories, rather than focusing on cross-sectional diagnosis or generic definitions of high-risk patient groups.

Clinical implications

Overall effects are slight for the interventions that are being used in the early stages of bipolar disorder. Most therapies show a greater effect on depressive symptoms and on depressive relapses than on manic features. Descriptions of early-stage interventions suggest that interventions for young people are based heavily on adult therapies used in established stage 3 or stage 4 bipolar disorder (eg, FFT, IPSRT, CBT), but that age-appropriate adjustments are made. Other interventions, such as the online interventions (HORYZONS42), apply new technologies. Surprisingly, no reports on bipolar disorder-specific peer group psycho education, which is frequently deployed in late stages of bipolar disorder, exist.16 Only one ongoing study55 clearly uses a peer educational approach. The most likely explanation for so few studies is that many interventions include psychoeducational elements, although family or multifamily formats might be preferred. Also, many integrated interventions, such as early inter ventions in psychosis services, include various group approaches, many of which incorporate socialisation and psychoeducation at an implicit if not an explicit level.

In view of the shared features of many therapies, whether the absence of effect on the manic symptom spectrum is a consequence of the lower basal rate of manic symptoms and relapses (hence, the trends for reductions in manic symptoms might not reach statistical significance), a dose—response effect (interventions might not be of sufficient duration to reduce the risk of mania), or because the interventions lack a crucial factor (not yet identified) that would specifically reduce the risk of transition to mania, remains unclear. The absence of a crucial missing factor from these interventions is important to consider because our Review highlights potential deficiencies in interventions that were primarily designed for other age groups. The most obvious shortcoming is that these interventions do not explicitly target normative developmental processes, such as changes in sleep—wake cycle and cognitive—emotional regulation that peak in adolescence and might increase the risk of transition to stage 2 in those individuals at high risk of bipolar disorder. A further limitation of current models is the lack of detailed attention to the management of frequently reported problems in early-stage bipolar disorder, such as substance use, physical health issues, and inactivity. Since the course of mental disorders is theoretically more malleable in stages 0–2, working with these populations offers the opportunity to identify and rectify these potential missing components of interventions.

An interesting finding from our outcome analysis was that individuals receiving a psychological intervention are frequently prescribed medications. Although this prescribing might be expected in first-episode and early-onset bipolar disorder cases,20 we noted that up to 40% of participants in the studies with high risk participants were receiving psychotropics (although not necessarily a medication for the treatment of mood disorders). Therefore, we have only little information as to whether therapy alone for individuals who are at risk of or in the earliest stages of bipolar disorder is a realistic alternative option. New studies are needed to establish whether therapy for bipolar disorder will ever be the sole intervention or if it will always be seen as an adjunct intervention. In addition, the high risk populations included in the studies reviewed often consisted of asymptomatic (stage 0) and symptomatic (stage 1) participants. This will probably affect findings because we predict that transition rates from stage 0 to stage 1 will be lower in samples with a higher proportion of asymptomatic individuals. More importantly, whether individuals at high risk of bipolar disorder who are asymptomatic will engage with or require a therapy, whether interventions are offered, or whether the goal should be on health promotion (such as sleep hygiene or generic problem solving) or the focus should be on genetic counselling or other goals, remains entirely unclear.

Comment

At the time of writing, we did not identify any major differences in outcomes for early stage bipolar disorder between bipolar disorder-specific interventions and transdiagnostic or multimodal interventions. This absence of difference is intriguing since some reports6,8,9,11,13 have suggested that treatment advances for severe mental disorders might be accelerated if stage-specific rather than illness-specific treatments for young people with emerging disorders were developed. However, we deem this conclusion tentative in view of the state of the art for early stage psychological interventions for bipolar disorder and the various challenges that remain to be addressed in this specialty (panel 2). Multicentre, transdiagnostic studies of psychological interventions across various disorders at a similar stage of illness could clarify this issue and help to establish whether interventions have unique benefits or disorder-specific effects. Investigation of the interventions used to modify the developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder would likewise provide insights into the mediators and moderators of transitions between the stages of bipolar disorder, and also into the reasons that early stage bipolar disorder can evolve into other clinical presentations (eg, psychosis).

Panel 2. Key future challenges.

Populations are heterogeneous in studies for increased risk, first episode, and early-onset bipolar disorder. Consensus regarding definitions of the early stages of bipolar disorder and the clinicopathological boundaries between stages is needed.

The sample sizes and duration of follow-up for the available research indicate that all studies lack adequate statistical power to examine effects on manic symptoms and the transition rates between stages.

The translation of models of therapy used with older adults with bipolar disorder to younger populations has focused on age-appropriate modifications. A major challenge remains to incorporate stage-appropriate interventions or techniques that target specific developmental biopsychosocial processes such as the sleep—wake cycle or cognitive—emotional abnormalities that are more common in younger rather than older adults.

Increased dialogue is needed between investigators working on interventions for the early stages of bipolar disorder, depression, and psychosis to improve understanding of the relative merits of transdiagnostic interventions compared with disorder-specific interventions.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using relevant subject headings for each database. For bipolar disorder, we used the terms affective disorder, affective psychosis, bipolar, bipolar NOS, mania, hypomania, and manic depression. For the types of interventions, we used general terms including psychotherapy, psychological treatments, psychological therapy, prevention, intervention,* psychoeducation, and specific terms such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based CBT (MB-CBT), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), interpersonal social rhythms therapy (IPSRT), family focused treatment (FFT), group psychoeducation. We also used known abbreviations for adolescents (FFT-A; IPRST-A), psychosis (CBTp), or high risk cases (FFT-HR). We included the terms prodrome, ultra-high risk, at risk, antecedent,* off spring, and first episode, early onset, and early intervention (these are extensively used in searches on emerging psychosis). We manually searched reference lists, specific journals (eg, Developmental Psychopathology, Early Intervention in Psychiatry), websites that register clinical trials (eg, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry), conference proceedings (eg, Inside Conferences, International Society of Affective Disorders and of Bipolar Disorders, International Early Psychiatry Association) and dissertation abstracts. We searched particularly for grey literature and we contacted researchers in the discipline who provided copies of conference presentations, additional information from reports or ongoing studies and data on subsamples of cases that specifically met our inclusion criteria.

Titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the searches were screened, duplicates removed, abstracts examined, and full reports for all potentially relevant studies were obtained and reviewed according to prespecified criteria (by MV, CH, BE, JS). Broad inclusion criteria were applied during selection to reduce the risk of exclusion of publications with relevant data (eg, cohort studies that also included interventions). Studies on paediatric or juvenile bipolar disorder, with limited descriptions of interventions, or with samples outside the specified age groups were excluded at this point. If we had insufficient information to reach a decision regarding inclusion, study investigators were contacted for further details; if no information was provided by the investigators, the study was excluded.

We identified 203 potentially relevant records, and another 41 records were obtained from other sources. Of the 92 abstracts selected for screening, 67 were eligible for detailed review (figure 1). 18 reports described therapies applicable to increased risk for bipolar disorder,33–38 first-episode bipolar disorder,39–43 and early-onset bipolar disorder44–50 populations. Most approaches were interventions specific for bipolar disorder, but five reports (two for first episode and three for early onset) were aimed at young people with affective and non-affective psychoses (HORYZONS,42 EPPIC,43 SR-CBT,44 and CBTpA45) or individuals with many mental health problems (Youth Early-intervention Study50).

Acknowledgments

JS, CH, BE, and AB are members of the European Network of Bipolar Research and Expert Centres (ENBREC), which has been funded by a FP7 grant and the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Network Initiative.

DJM reports book royalties (including for manuals on family focused treatment) from Guilford Press and John Wiley and Sons; research grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Carl and Roberta Deutsch Foundation, the Kayne Family Foundation, the Attias Family Foundation, the Danny Alberts Foundation, and the Robert Sutherland Foundation. AB reports grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb (outside the submitted work). BE reports personal fees from Otsuka France, personal fees from BMS France, and personal fees from AstraZeneca France (outside the submitted work). CH reports personal fees from Otsuka France, personal fees from BMS France, personal fees from AstraZeneca France, and personal fees from Lundbeck (outside the submitted work). EMS reports personal fees from St Vincent’s Private Hospital, non-financial support from Headspace Camperdown at the Brain and Mind Research Institute in Camperdown, NSW, Australia, grants from Servier, personal fees from Servier, personal fees from Eli Lilly, and personal fees from Pfizer (outside the submitted work). MF reports grants from National Institute of Mental Health, during the conduct of the study; American Psychiatric Press, Guilford Press, and Child & Family Psychological Services, outside the submitted work. JS reports grants from Research for Patient Benefit, UK (grant number PB-PG-0609-16166): Early identification and intervention in mood disorders in youth and grants from Medical Research Council Cohort grant: A Bipolar II Cohort (ABC study; outside the submitted work). MV received an Ivano Becchi Professional Grant from Banca del Monte di Lombardia Foundation and funded by this programme, she spent 6 months working with JS.

Footnotes

Contributors

MV and JS designed the study and drafted all versions of the manuscript. MV, JS, CH, and BE identified studies for review. All authors provided data and drafted subsections and provided feedback on all versions of the manuscript. JS is the sponsor of the publication.

Declarations of interest: The funders had no further role in the study. SAH, LJG, CM, and PC declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:2093–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smits N, Smit F. Screening and early psychological intervention for depression in schools: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:300–07. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu P, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, Callahan P, de Silva S, Purcell R. An evidence map of interventions across premorbid, ultra-high risk and first episode phases of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callahan P, Liu P, Purcell R, Parker AG, Hetrick SE. Evidence map of prevention and treatment interventions for depression in young people. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:820735. doi: 10.1155/2012/820735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:616–22. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonnella JS, Hornbrook MC, Louis DZ. Staging of disease. A case-mix measurement. JAMA. 1984;251:637–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, et al. Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:243–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickie IB, Scott EM, Hermens DF, et al. Applying clinical staging to young people who present for mental health care. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, Otto MW. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:595–602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott J, Hickie I, McGorry P. Invited editorial: Pre-emptive psychiatric treatments: pipe dream or a realistic outcome of clinical staging models? Neuropsychiatry. 2012;2:263–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Gaag M, Smit F, Bechdolf A, et al. Preventing a first episode of psychosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophr Res. 2013;149:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berk M, Conus P, Lucas N, et al. Setting the stage: from prodrome to treatment resistance in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:671–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapczinski F, Magalhães PV, Balanzá-Martinez V, et al. Staging systems in bipolar disorder: an International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force Report. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:354–63. doi: 10.1111/acps.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241–51. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:402–07. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, et al. Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:996–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott J, Paykel E, Morriss R, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for severe and recurrent bipolar disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:313–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavuluri MN, Graczyk PA, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Heidenreich J, Miklowitz DJ. Child-and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: development and preliminary results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:528–37. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feeny NC, Danielson CK, Schwartz L, Youngstrom EA, Findling RL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bipolar disorders in adolescents: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:508–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fristad MA, MacPherson HA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:339–55. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James A, Hoang U, Seagroatt V, Clacey J, Goldacre M, Leibenluft E. A comparison of American and English hospital discharge rates for pediatric bipolar disorder, 2000 to 2010. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:614–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas J, Scott J. A systematic review of gender-specific rates of unipolar and bipolar disorders in community studies of pre-pubertal children. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:5–15. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson GA, Meyer SE. Phenomenology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: complexities and developmental issues. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:939–69. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinares M, Colom F, Rosa AR, et al. The impact of staging bipolar disorder on treatment outcome of family psychoeducation. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessing LV, Hansen HV, Christensen EM, et al. Do young adults with bipolar disorder benefit from early intervention? J Affect Disord. 2014:152–154. 403–08. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González S, Artal J, Gómez E, et al. Early intervention in bipolar disorder: the Jano program at Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2012;40:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMurrich S, Sylvia LG, Dupuy JM, et al. Course, outcomes, and psychosocial interventions for first-episode mania. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:797–808. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNamara RK, Strawn JR, Chang KD, DelBello MP. Interventions for youth at high risk for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:739–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfennig A, Correll CU, Marx C, et al. Psychotherapeutic interventions in individuals at risk of developing bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;8:3–11. doi: 10.1111/eip.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Callahan P, Purcell R. Evidence mapping: illustrating an emerging methodology to improve evidence-based practice in youth mental health. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:1025–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfennig A, Leopold K, Bechdolf A, et al. Early specific cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy in subjects at high risk for bipolar disorders: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:161. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott J. Early identification of young people at high risk of recurrent mood disorders: A feasibility study. National Institute for Health Research; [PB-PG-0609-16166] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DelBello MP. Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy for Youth with Anxiety at Risk for Bipolar Disorder. ClinicalTrialsgov: National Institute of Health; [ NCT02090595]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miklowitz DJ, Chang KD, Taylor DO, et al. Early psychosocial intervention for youth at risk for bipolar I or II disorder: a one-year treatment development trial. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein TR, Fersch-Podrat R, Axelson DA, et al. Early intervention for adolescents at high risk for the development of bipolar disorder: pilot study of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) Psychotherapy (Chic) 2014;51:180–89. doi: 10.1037/a0034396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadkarni RB, Fristad MA. Clinical course of children with a depressive spectrum disorder and transient manic symptoms. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones SH, Burrell-Hodgson G. Cognitive-behavioural treatment of first diagnosis bipolar disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15:367–77. doi: 10.1002/cpp.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macneil CA, Hasty M, Cotton S, et al. Can a targeted psychological intervention be effective for young people following a first manic episode?Results from an 18-month pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6:380–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Searson R, Mansell W, Lowens I, Tai S. Think Effectively About Mood Swings (TEAMS): a case series of cognitive-behavioural therapy for bipolar disorders. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012;43:770–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Lederman R, et al. On the HORYZON: moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2013;143:143–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conus P, Abdel-Baki A, Harrigan S, Lambert M, McGorry PD, Berk M. Pre-morbid and outcome correlates of first episode mania with psychosis: is a distinction between schizoaffective and bipolar I disorder valid in the early phase of psychotic disorders? J Affect Disord. 2010;126:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Painter M, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for improving social recovery in psychosis: a report from the ISREP MRC Trial Platform Study (Improving Social Recovery in Early Psychosis) Psychol Med. 2009;39:1627–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Browning S, Corrigall R, Garety P, Emsley R, Jolley S. Psychological interventions for adolescent psychosis: a pilot controlled trial in routine care. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28:423–26. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein TR, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Brent DA. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: a 1-year open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:820–30. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31805c1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Richards JA. Early-onset bipolar disorder: a family treatment perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:1247–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldstein BI, Goldstein TR, Collinger KA, et al. Treatment development and feasibility study of family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder and comorbid substance use disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2014;20:237–48. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000450325.21791.7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hlastala SA, Kotler JS, McClellan JM, McCauley EA. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: treatment development and results from an open trial. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:457–64. doi: 10.1002/da.20668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gehue L, Scott E, Hermens D, Scott J, Hickie I. YES: Youth Early-intervention Study, a randomised control trial investigating group interventions as an adjunct to usual treatment; International Society of Affective Disorders; Berlin, Germany. April 28–30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51R.obillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, et al. Delayed sleep phase in young people with unipolar or bipolar affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:260–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]