Abstract

Purpose

Although guidelines indicate that routine dissection of the central lymph nodes in patients with thyroid carcinoma should include the right para-oesophageal lymph nodes (RPELNs), located between the right recurrent laryngeal nerve and the cervical oesophagus and posterior to the former, RPELN dissection is often omitted due to high risk of injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the right inferior parathyroid gland.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively identified all patients diagnosed with papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent total thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection, including the RPELNs, between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2013 at the Thyroid Cancer Center of Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Results

Of 5556 patients, 148 were positive for RPELN metastasis; of the latter, 91 had primary tumours greater than 1 cm (p<0.001). Extrathyroidal extension by the primary tumour (81.8%; p<0.001), bilaterality, and multifocality were more common in patients with than without RPELN metastasis; however, there were no significant differences in age and sex between groups. A total of 95.9% of patients with RPELN metastasis had central node (except right para-oesophageal lymph node) metastasis, and the incidence of lateral neck node metastasis was significantly higher in patients with than without RPELN metastasis (63.5% vs. 14.3%, p<0.001). Forty-one patients underwent mediastinal dissection, with 11 patients confirmed as having mediastinal lymph node metastasis with RPELN metastasis on pathological examination.

Conclusion

RPELN metastasis is significantly associated with lateral neck and mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

Keywords: RPELN, metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid carcinoma is the most common type of endocrine malignancy, and its incidence is rapidly increasing.1,2 Over 90% of all thyroid carcinomas exhibit a relatively indolent clinical course, with excellent prognosis.1,3 In contrast, cervical lymph node metastasis has been observed in 30% to 90% of patients with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and has been shown to be closely associated with persistent and recurrent disease.1,4,5,6,7,8,9 Most metastatic sites in patients with PTC are located in central compartment lymph nodes,10,11 and central lymph node dissection has been found to reduce loco-regional recurrence and improve disease-free survival in patients with PTC.11,12

The anatomical borders of the central compartment lymph nodes include the hyoid bone superiorly, the innominate artery inferiorly, and the common carotid arteries bilaterally. A consensus statement has listed the prelaryngeal (Delphian), pretracheal, and paratracheal nodal basins bilaterally as the central compartment lymph node group. Therapeutic and prophylactic central lymph node dissection requires the removal of all three lymph node groups at the minimum.4

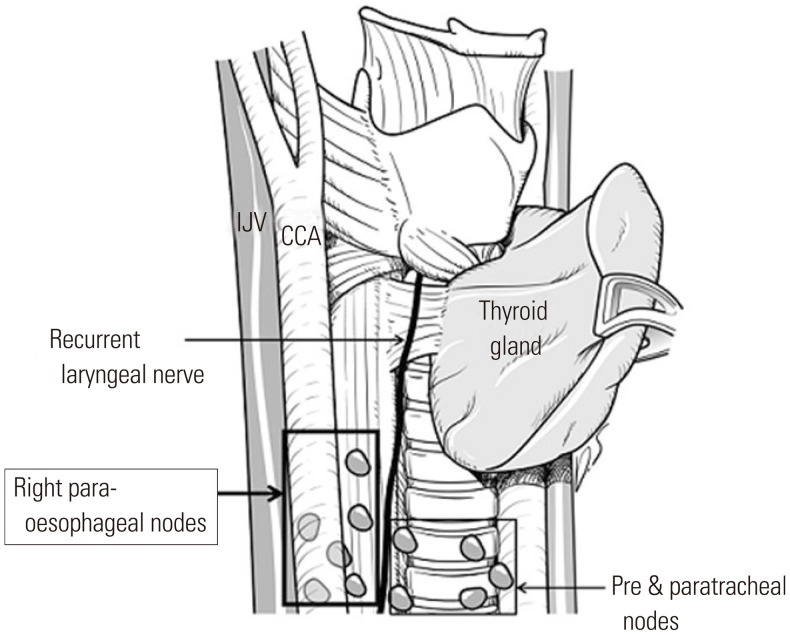

The lymph node located between the right recurrent laryngeal nerve and the cervical oesophagus is called the right paraoesophageal lymph node (RPELN). Due to its location, the RPELN is considered one of the central compartment lymph nodes. Although it has been recommended that routine central lymph node dissection should include the RPELN posterior to the right recurrent laryngeal nerve,13 dissection of the RPELN is often omitted due to high risk of injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the right inferior parathyroid gland (Fig. 1). To determine the necessity of RPELN dissection, we assessed the clinical significance of RPELN metastasis and the factors affecting it.

Fig. 1. Location of right para-oesophageal lymph nodes. IJV, internal jugular vein; CCA, common carotid artery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed our database to identify all patients who were diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma and underwent total thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection, including RPELN dissection, between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013 at the Thyroid Cancer Center, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. Dissection of the central nodes was performed routinely. Lateral neck metastasis was diagnosed based on preoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology or intraoperative frozen sectioning and sampling of suspicious lymph nodes, and patients with lateral neck metastasis underwent lateral neck dissection. Mediastinal dissection was performed if mediastinal metastasis was confirmed after the intraoperative frozen sectioning of suspicious nodes that had been evaluated by preoperative radiologic findings.

Postoperative histopathologic results were confirmed by a single specialized endocrine pathologist (S. W. Hong); the patients were then divided into two groups according to whether the histopathologic records indicated pathologically proven RPELN metastasis. The clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups were compared, including sex, age, tumour size, location, multiplicity, bilateral involvement, extrathyroidal extension, and central, lateral, and mediastinal lymph node invasion. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were compared using Student's t-test, a chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the statistical significance of the associations between RPELN metastasis and clinicopathologic factors. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% relative confidence intervals were calculated to determine the relevance of all potential predictors. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, which waived the requirements for patient approval and informed consent due to the retrospective nature of this study.

RESULTS

Of the 5556 patients who underwent RPELN dissection, all patients had PTC. Table 1 shows the demographic and pathologic characteristics of these patients. Final pathology reports indicated that 148 (2.7%) patients were diagnosed as positive (RPELN+) and 5408 (97.3%) as negative (RPELN-) for RPELN. Mean tumour size was larger in the RPELN+ group than in the RPELN- group (p<0.001). Mean age was younger in the RPELN+ group than in the RPELN- group (43.4±11.6 years vs. 46.2±11.5 years; p=0.003). Patients older than 45 years were dominant in the RPELN- group (RPELN+: 40.5%; RPELN-: 53.7%; p=0.002).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Thyroid Surgery Plus RPELN Dissection.

| Variables | RPELN+ n=148 |

RPELN- n= 5408 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male/female (%) | 52/96 (35.1/64.9) | 1119/4289 (20.7/79.3) | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| Mean age, yrs | 43.4±11.6 | 46.2±11.5 | 0.003 |

| ≥45 (%) | 60 (40.5) | 2903 (53.7) | 0.002 |

| Primary tumor | |||

| Mean tumour size (cm) | 1.49±1.07 | 0.99±0.69 | <0.001 |

| >1 cm (%) | 91 (61.5) | 1791 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Thyroiditis (%) | 53 (35.8) | 2090 (38.6) | 0.549 |

| Extrathyroidal extension (%) | 121 (81.8) | 3338 (61.7) | <0.001 |

| Multifocality (%) | 79 (52.7) | 2072 (38.3) | 0.001 |

| Bilaterality (%) | 52 (35.1) | 1381 (25.5) | 0.01 |

| Psammomatous calcification (%) | 97 (65.5) | 2110 (39.0) | <0.001 |

RPELN, right para-oesophageal lymph node; RPELN+, with RPELN metastasis; RPELN-, without RPELN metastasis.

Values are expressed as the number and percent or the mean±SD.

Of the 148 patients in the RPELN+ group, 91 (61.5%) had primary tumours greater than 1 cm in size (p=0.008). Extrathyroidal extension by the primary tumour (81.8%; p<0.001) and multifocality (52.7%; p=0.001) were more common in the RPELN+ group than in the RPELN- group.

Central node metastases, excluding RPELNs metastasis (95.9% vs. 44.2%; p<0.001) and lateral neck node metastasis (63.5% vs. 14.3%; p<0.001), were significantly more frequent in the RPELN+ group than in the RPELN- group (Table 2).

Table 2. Association between Metastases in the RPELNs and Other Lymph Nodes.

| Variables | RPELN+ n=148 |

RPELN- n=5408 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central node metastasis (excluding RPELN metastasis) (%) | 142 (95.9) | 2390 (44.2) | <0.001 |

| Lateral neck node metastasis (%) | 94 (63.5) | 773 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Mediastinal metastasis (%) | 11 (7.4) | 30 (0.6) | <0.001 |

RPELN, right para-oesophageal lymph node; RPELN+, with RPELN metastasis; RPELN-, without RPELN metastasis.

Forty-one patients underwent mediastinal dissection, with all confirmed as having mediastinal lymph node metastasis on pathological examination; 11 (7.4%) of these patients were in the RPELN+ group (7.4% vs. 0.6%; p<0.001), indicating that RPELN is closely associated with mediastinal lymph node metastasis (Table 2).

The results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Following adjustment for other predictors, tumour size, bilateral involvement, and extrathyroidal extension were no longer significantly predictive of RPELN metastasis. However, central node metastasis, excluding RPELN metastasis (OR=14.715; p<0.001) and lateral neck node (OR=4.383; p=0.016) metastasis, were significantly predictive of RPELN metastasis. Other results are shown in Table 4. In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mediastinal metastasis, RPELN metastasis was significantly predictive of mediastinal metastasis.

Table 3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with RPELN Metastasis.

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 1.315 (0.917-1.886) | 0.136 |

| Age ≥45 | 1.405 (0.735-1.485) | 0.808 |

| Primary tumour | ||

| Tumour size (>1 cm vs. ≤1 cm) | 1.406 (0.974-2.031) | 0.069 |

| Extrathyroidal extension | 1.274 (0.816-1.990) | 0.286 |

| Psammomatous calcification | 1.373 (0.954-1.976) | 0.088 |

| Multifocality | 1.376 (0.852-2.222) | 0.192 |

| Bilaterality | 0.936 (0.566-1.546) | 0.795 |

| Nodal status | ||

| Central node metastasis (excluding RPELN metastasis) | 14.715 (6.363-34.032) | <0.001 |

| Lateral node metastasis | 4.383 (3.016-6.370) | <0.001 |

RPELN, right para-oesophageal lymph node; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Mediastinal Metastasis.

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 2.774 (1.445-5.324) | 0.002 |

| Primary tumor | ||

| Tumour size (>1 cm vs. ≤1 cm) | 5.594 (1.929-16.223) | 0.002 |

| Extrathyroidal extension | 0.997 (0.370-2.684) | 0.994 |

| Psammomatous calcification | 0.903 (0.451-1.808) | 0.773 |

| Multifocality | 1.525 (0.595-3.910) | 0.38 |

| Bilaterality | 1.109 (0.439-2.800) | 0.827 |

| Nodal status | ||

| Central node metastasis (except RPELN metastasis) | 1.321 (0.448-3.894) | 0.614 |

| RPELN metastasis | 2.388 (1.111-5.131) | 0.026 |

RPELN, right para-oesophageal lymph node.

Twenty-seven patients experienced postoperative hoarseness, 24 of whom had undergone shaving-off procedures for recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion due to thyroid cancer. Overall, 64 patients (1.15%) were diagnosed with permanent hypoparathyroidism, defined as an s-PTH concentration <10.0 pg/mL, and persistent hypocalcaemic symptoms of a tingling sensation and numbness requiring oral calcium supplements at 3 months.

DISCUSSION

Cervical lymph node metastasis is a factor associated with poor prognosis in patients with thyroid carcinoma.5,14,15,16 Extranodal invasion in PTC was found to be strongly associated with later development of distant metastasis and with a significantly higher mortality rate.14 Moreover, a population-based, nested case-control study demonstrated that lymph node metastasis increases mortality rates in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma.16 Other factors independently associated with persistent disease and recurrence are a tumour size >3 cm, extra-capsular extension, and the locations of metastatic lymph nodes,5,15 with central compartment lymph nodes being the most frequently involved site.4,5,6,15,16,17 Thus, complete surgical removal of lymph nodes in the central compartment during thyroid cancer surgery is needed to reduce disease persistence and recurrence as well as mortality.11

Although RPELNs are located within the central compartment, they are frequently not removed during thyroid cancer surgery due to the high risk of injuries to the right recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid gland. In investigating the clinicopathologic features of PTC patients with RPELN metastasis, we found that pathologically confirmed RPELN metastasis was associated with a larger tumour size and extrathyroidal extension. Additionally, both central and lateral neck node metastases showed significant correlations with RPELN metastasis on both univariate and multivariate analyses, findings that were consistent with previous results.18,19

Although mediastinal metastasis is fairly uncommon in differentiated thyroid carcinoma, it may result in a devastating clinical course by directly invading mediastinal organs.4,20,21 Several studies have assessed the possible risk factors related to mediastinal metastasis in thyroid carcinoma. For example, patients with central neck metastasis, a tumour size >1.5 cm, or lymphovascular invasion were found to have a significantly higher rate of lymph node metastasis in the anterior superior mediastinum and the tracheo-oesophageal grooves, extending from the suprasternal notch to the innominate artery,22 and poor tumour differentiation and distant metastases were found to be predictive of mediastinal metastasis.23 An evaluation of the pattern of nodal metastasis in thyroid carcinoma showed that a greater number of metastatic lymph nodes occurred in patients with distant metastasis.4 Lymph nodes in the lower third of the neck may function as a bridge between the cervical and mediastinal lymphatic chains.24 Indeed, we found that patients pathologically confirmed to have mediastinal metastasis were more likely to exhibit RPELN metastasis than patients without RPELN metastasis were likely to have mediastinal metastasis. These findings suggest that RPELNs may be the route from mediastinal lymph nodes to lateral neck node metastasis.

In addition to the close relationship between RPELN metastasis with lateral neck involvement,22 we found that patients with RPELN metastasis demonstrated a high rate of central neck node metastasis. These findings suggest that the presence of RPELN metastasis may be associated with a more aggressive disease course and strongly indicate that RPELNs should be included in routine central lymph nodes dissection (CLND). Moreover, a careful work-up of the lateral neck compartment should be considered in patients with RPELN metastasis. Future studies should assess the association between an aggressive disease pattern and RPELN metastasis.

The extent of surgical management in patients with thyroid cancer should include considerations of postoperative complications and morbidity. Extensive lymph node dissection may increase morbidity while not benefiting surgical outcomes and the survival rate.8,25,26 Although 27 of our patients experienced postoperative hoarseness, this could not be considered a direct result of RPELN dissection, as 24 of these patients underwent shaving-off procedures due to tumour invasion of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve. The incidence of permanent hypoparathyroidism was 1.15%, similar to previous studies.27,28

Several studies on morbidity following reoperation of the central compartment for recurrent or persistent thyroid cancer suggest that reoperation can be challenging and lead to high rates of complications, such as permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and hypoparathyroidism.29,30,31 Appropriate determination of the extent of primary surgery is therefore needed to reduce locoregional recurrence and persistent disease rates in patients with PTC. Postoperative morbidity rates can also be reduced by meticulous surgical techniques and competency in surgical skills.

This study had several limitations. First, the small sample size may be inadequate to draw conclusions on the association between RPELN and mediastinal metastasis. However, due to the rarity of mediastinal metastasis in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma, our findings may indicate a route between the cervical and mediastinal lymphatic channels. Second, only RPELNs in the central compartment group were considered. Recently, the prelaryngeal (Delphian) nodes were shown to be associated with extra-thyroidal tumour extension and an increased incidence of central and lateral neck metastasis,32 suggesting that central compartment lymph node groups other than RPELNs may be associated with lateral or mediastinal metastasis. Further studies are needed to investigate the correlations between different lymph node groups in the central compartment and lateral or mediastinal metastasis.

This study has shown that RPELN metastasis was significantly associated with lateral and mediastinal lymph nodes metastasis. RPELN metastasis may be associated with tumour aggressiveness and poor prognosis in patients with thyroid cancer. Patients with suspected RPELN metastasis should undergo complete node dissection, and those with confirmed RPELN metastasis should be evaluated for lateral neck and mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dong-Su Jang (Research Assistant, Department of Anatomy, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea) for his excellent support with the medical illustration.

This study was financially supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine in 2011 (6-2011-0066).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Davidson HC, Park BJ, Johnson JT. Papillary thyroid cancer: controversies in the management of neck metastasis. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:2161–2165. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31818550f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:11–24. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadi N, Grewal A, Davidson BJ. Patterns of cervical lymph node metastases in primary and recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. J Oncol. 2011;2011:735678. doi: 10.1155/2011/735678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machens A, Hinze R, Thomusch O, Dralle H. Pattern of nodal metastasis for primary and reoperative thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:22–28. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leboulleux S, Rubino C, Baudin E, Caillou B, Hartl DM, Bidart JM, et al. Prognostic factors for persistent or recurrent disease of papillary thyroid carcinoma with neck lymph node metastases and/or tumor extension beyond the thyroid capsule at initial diagnosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5723–5729. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira JA, Jimeno J, Miquel J, Iglesias M, Munné A, Sancho JJ, et al. Nodal yield, morbidity, and recurrence after central neck dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 2005;138:1095–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White ML, Gauger PG, Doherty GM. Central lymph node dissection in differentiated thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:895–904. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roh JL, Park JY, Park CI. Total thyroidectomy plus neck dissection in differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma patients: pattern of nodal metastasis, morbidity, recurrence, and postoperative levels of serum parathyroid hormone. Ann Surg. 2007;245:604–610. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250451.59685.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Wei WJ, Ji QH, Zhu YX, Wang ZY, Wang Y, et al. Risk factors for neck nodal metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 1066 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1250–1257. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins KT, Clayman G, Levine PA, Medina J, Sessions R, Shaha A, et al. Neck dissection classification update: revisions proposed by the American Head and Neck Society and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:751–758. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Thyroid Association Surgery Working Group; American Association of Endocrine Surgeons; American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; American Head and Neck Society. Carty SE, Cooper DS, et al. Consensus statement on the terminology and classification of central neck dissection for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1153–1158. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang TS, Evans DB, Fareau GG, Carroll T, Yen TW. Effect of prophylactic central compartment neck dissection on serum thyroglobulin and recommendations for adjuvant radioactive iodine in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4217–4222. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2594-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grodski S, Cornford L, Sywak M, Sidhu S, Delbridge L. Routine level VI lymph node dissection for papillary thyroid cancer: surgical technique. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita H, Noguchi S, Murakami N, Kawamoto H, Watanabe S. Extracapsular invasion of lymph node metastasis is an indicator of distant metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:2268–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugitani I, Kasai N, Fujimoto Y, Yanagisawa A. A novel classification system for patients with PTC: addition of the new variables of large (3 cm or greater) nodal metastases and reclassification during the follow-up period. Surgery. 2004;135:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundgren CI, Hall P, Dickman PW, Zedenius J. Clinically significant prognostic factors for differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a population-based, nested case-control study. Cancer. 2006;106:524–531. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gemsenjäger E, Perren A, Seifert B, Schüler G, Schweizer I, Heitz PU. Lymph node surgery in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:182–190. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YS, Park WC. Clinical predictors of right upper paraesophageal lymph node metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:164. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae SY, Yang JH, Choi MY, Choe JH, Kim JH, Kim JS. Right paraesophageal lymph node dissection in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:996–1000. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machens A, Hinze R, Lautenschläger C, Thomusch O, Dralle H. Thyroid carcinoma invading the cervicovisceral axis: routes of invasion and clinical implications. Surgery. 2001;129:23–28. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.108699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honings J, Stephen AE, Marres HA, Gaissert HA. The management of thyroid carcinoma invading the larynx or trachea. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:682–689. doi: 10.1002/lary.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi JY, Choi YS, Park YH, Kim JH. Experience and analysis of level VII cervical lymph node metastases in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80:307–312. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.80.5.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machens A, Dralle H. Prediction of mediastinal lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:171–176. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johner CH, Ranniger K. Mediastinal lymphography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1968;127:1313–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum MA, McHenry CR. Central neck dissection for papillary thyroid cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teixeira G, Teixeira T, Gubert F, Chikota H, Tufano R. The incidence of central neck micrometastatic disease in patients with papillary thyroid cancer staged preoperatively and intraoperatively as N0. Surgery. 2011;150:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonçalves Filho J, Kowalski LP. Surgical complications after thyroid surgery performed in a cancer hospital. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosato L, Avenia N, Bernante P, De Palma M, Gulino G, Nasi PG, et al. Complications of thyroid surgery: analysis of a multicentric study on 14,934 patients operated on in Italy over 5 years. World J Surg. 2004;28:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6903-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lefevre JH, Tresallet C, Leenhardt L, Jublanc C, Chigot JP, Menegaux F. Reoperative surgery for thyroid disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:685–691. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pezzullo L, Delrio P, Losito NS, Caracò C, Mozzillo N. Post-operative complications after completion thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:215–218. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)92340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MK, Mandel SH, Baloch Z, Livolsi VA, Langer JE, Didonato L, et al. Morbidity following central compartment reoperation for recurrent or persistent thyroid cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1214–1216. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.10.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer NG, Kumar A, Nixon IJ, Patel SG, Ganly I, Tuttle RM, et al. Incidence and significance of Delphian node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;253:988–991. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821219ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]