Abstract

Behavioral changes in dementia, especially behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), may result in alterations in moral reasoning. Investigators have not clarified whether these alterations reflect differential impairment of care-based vs. rule-based moral behavior. This study investigated 18 bvFTD patients, 22 early onset Alzheimer’s disease (eAD) patients, and 20 healthy age-matched controls on care-based and rule-based items from the Moral Behavioral Inventory and the Social Norms Questionnaire, neuropsychological measures, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) regions of interest. There were significant group differences with the bvFTD patients rating care-based morality transgressions less severely than the eAD group and rule-based moral behavioral transgressions more severely than controls. Across groups, higher care-based morality ratings correlated with phonemic fluency on neuropsychological tests, whereas higher rule-based morality ratings correlated with increased difficulty set-shifting and learning new rules to tasks. On neuroimaging, severe care-based reasoning correlated with cortical volume in right anterior temporal lobe, and rule-based reasoning correlated with decreased cortical volume in the right orbitofrontal cortex. Together, these findings suggest that frontotemporal disease decreases care-based morality and facilitates rule-based morality possibly from disturbed contextual abstraction and set-shifting. Future research can examine whether frontal lobe disorders and bvFTD result in a shift from empathic morality to the strong adherence to conventional rules.

Keywords: morality, dementia, brain, neuropsychology, neuroimaging, frontotemporal

1. Introduction

Moral behavior, or rules of conduct for what is right or wrong, is a necessary component of human societies (Bzdok et al., 2012). This universality of moral behavior implies that it has origins in evolution and substrates in cognition and the human brain. Many of the cognitive processes involved in moral behavior are located in the frontal regions of the brain (Fumagalli & Priori, 2012). For example the prefrontal context has particular salience in adhering to social norms (Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, & Grafman, 2002), and it is generally more activated in those who are applying moral principles to moral dilemmas (Prehn et al., 2007). Frontal involvement is also implicated when determining moral value of actions (Shenhav & Greene, 2010). The medial frontal gyrus demonstrates increased activation when judging emotionally charged, unpleasant social scenes which represent moral violations (Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002). Thus frontal system functioning is crucial for moral judgments that involve emotional processes, cognitive control, and mediating between emotional and rational considerations.

In addition to frontal regions, several regions within the temporal lobe are implicated in moral reasoning. In particular, the area around the superior temporal sulcus plays a role in moral processing of emotion (Kédia, Berthoz, Wessa, Hilton, & Martinot, 2008; Young, Cushman, Hauser, & Saxe, 2007; Young & Saxe, 2009), social cognition (Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley, & Cohen, 2004; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002), and decision-making (Greene et al., 2004; Heekeren, Wartenburger, Schmidt, Schwintowski, & Villringer, 2003). Additionally, the identification of self-and group-oriented goals involves the anterior temporal cortex, particularly the superior temporal gyrus, where self-referential semantic knowledge converges with social perceptive processes (Allison, Puce, & McCarthy, 2000; Moll, Zahn, de Oliveira-Souza, Krueger, & Grafman, 2005; Zahn et al., 2009). Consequently, the temporal lobe seems to be important for cognitive processing of morally salient stimuli that involves social cues, complexity, and theory of mind (ToM).

Several cognitive processes underlie moral behavior. The capacity for empathy, both cognitive and emotions, and the presence of ToM, or the ability to appreciate that others have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, are essential for moral behavior. Social cognitive process like the attribution of intentionality or agency in right inferior parietal cortex (Castelli, Happé, Frith, & Frith, 2000), and mechanisms of reward-punishment and impulse control in orbitofrontal cortex For example, Kédia and colleagues (2008) asked participants to imagine senarios of violent actions order to evoke anger, guilt and compassion. Each senario activated in traditional ToM regions (dorsal medial prefrontal cortext, precuneus, and bilateral temporal-parietal junctions), but also, being concerned by a harmful action recruited emotion centers – the bilateral amyddala, anterior cingulate, and basal ganglia. In the case of J.S.’s “acquired sociopathy” degradation of the right orbitofrontal cortex inhibited appropriate social cognition and social norms while facilitated inappropriate emotional attribution (Blair & Cipolotti, 2000). Finally, the interplay between neural activity in brain regions associated cognitive and emotional process highlights the importance of cognitive control in moral reasoning (Greene, Paxton, & Raichle, 2009.

The study of moral behavior has a history of competing dichotomies. The classic morality literature features the distinction between deontological - intuitive emotional judgments such as rights or duties (Kant, 1909) - vs. utilitarian reasoning - values actions that benefit the “greater good” (Mill, 1863). Modern neuroimaging studies associate deontological reasoning with ventromedial frontal functions and utilitarian reasoning with dorsolateral frontal functions (Chiong et al., 2013; Mendez et al., 2005, Mendez & Shapira, 2009). The moral dilemma literature presents a related distinction, with similar brain localizations, between actively causing another individual harm, or personal moral reasoning, from passively causing a person harm, or impersonal moral reasoning (Greene, 2009; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001). Two further themes that reoccur within these prior categories are care-based behavior and rule-based behavior. Care-based behaviors emphasize mutual responsiveness and moral actions that affect others, particularly the most vulnerable, such as a hungry mother’s choice to prioritize feeding her children (Gilligan, 2008). In contrast, rule-based emphasize societal heuristics or conventions regardless of situation, such as always stopping at road signs even in a rural area with high visibility (Greene, Paxton, & Raichle, 2009). Whereas the personal and impersonal moral reasoning examine agency, care-based and rule-based distinguishes behavior by empathy for others vs. adherence to social norms. Care-based may be an altruistic person-based reasoning as it seeks to protect and nurture others instead of merely avoiding harming them. Similarly, care-based reasoning may involve emotional processes associated with deontological reasoning, but without the “duty” component. In contrast, rule-based morality and impersonal reasoning connote then need to follow societal guidelines and an overlap with utilitarian reasoning in that social norms develop around doing the greater good for society over the individual. As care-based and rule-based methods differ in the interpretation and response to social information, identifying the predominant mode of moral reasoning may be helpful in determining how a person afflicted with dementia will act or which social norm they are likely to violate.

There is limited information on the neuroanatomical and neuropsychological correlates of care-based and rule-based moral behavior. Care-based morality may be associated with mechanisms of emotional empathy (Eslinger, 1998; Rankin et al., 2006), and rule-based morality may be associated with executive functions that mediate the application of rules in various tasks (Goodwin, Blackman, Sakellaridi, & Chafee, 2012). Neuroimaging studies have implicated the anterior temporal lobe (ATL) and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in moral cognition and socioemotional reasoning (Bzdok et al., 2012; Sevinc & Spreng, 2014). The right ATL may be responsible for maintaining knowledge of appropriate social behavior (Zahn et al., 2009) and the right temporal pole is involved in the processing of empathy (Rankin et al., 2006). In contrast, the OFC has been implicated in behaving in a socially appropriate manner and suppressing inappropriate behavior (Blair & Cipolotti, 2000). Taken together, these findings suggest that care and rule-based moral behavior rely on activity in the ATL and executive functions embedded within the OFC.

Given the focal involvement of frontal and anterior temporal disease, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) may be a particularly valuable model for clarifying the brain-behavior relationships of studying care-based vs. rule-based morality. BvFTD is the dementia most known for social disturbances. BvFTD is a progressive neurodegeneration of the frontal and anterior temporal lobes which results in alterations in social and emotional behavior. Specifically, the core features of bvFTD involve transgression of social norms including lack of concern for others, apathy, disinhibited behavior, a loss of awareness, and a loss of insight for their behavior and its consequences (Rascovsky et al., 2011). Alterations in the patient’s moral reasoning, results in formerly rule-abiding patients violating social norms and conventions and even resulting in law-breaking and antisocial acts (Mendez, Chen, Shapira, & Miller, 2005; Mendez & Shapira, 2009). BvFTD patients also fail to recognize when others violate social norms, and they are unable to identify instances in which their personal judgments transgress social conventions (Lough et al., 2006). Altered morality in bvFTD extends to atypical patterns in moral reasoning, as exemplified in moral scenarios such as the “Trolley Dilemma”. When these patients are presented with a runaway trolley barreling towards five people, distinct from normal controls, the bvFTD patients endorse pushing a man off a bridge to save five people on the trolley’s track (Mendez et al., 2005)., suggesting moral decisions biased toward rational rather than empathy-based behaviors

In addition to bvFTD, other dementia syndromes may impair cognitive reasoning with consequent alterations in moral reasoning (Irish, Hodges, & Piguet, 2014; Kemp, Després, Sellal, & Dufour, 2012). Patients with early-onset AD (eAD), beginning before age 65, may be particularly vulnerable to disturbed executive processes, which may impact on reasoning abilities (Smits et al., 2012). Executive and behavioral symptoms combined with decreased memory and language functioning affect an eAD patient’s capacity for sound decision-making in social settings (Gregory et al., 2002). EAD patients have demonstrated significant deficits in mundane moral decisions and social cognition tasks compared to age-matched controls (Torralva, Dorrego, Sabe, Chemerinski, & Starkstein, 2000). Although limited data suggest that the incidence rate of “sociopathic” behavior is as elevated in eAD as in bvFTD, those with eAD might behave in socially unacceptable manner in times when they are overwhelmed with complex tasks that require the integration of several social elements (Werner, Stein-Shvachman, & Korczyn, 2009).

The current study sought to examine care-based and rule-based moral behavior in bvFTD and eAD patients in comparison to healthy controls. We desired to understand the neurocognitive processes involved in care and rule-based moral behavior both from a neuropsychological and neuroanatomical standpoint. This study assessed the relationship between ratings of moral transgressions with other neurocognitive measures and utilized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine cortical regions of interests (ROIs) previously implicated in social and moral behavior. The OFC and ATL were specifically chosen as a priori ROIs because they have been implicated in socioemotional reasoning (Bzdok et al., 2012; Sevinc & Spreng, 2014) and are vulnerable structures in bvFTD and AD (Yi, Bertoux, Mioshi, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013). Given prior studies in bvFTD, we hypothesized that bvFTD patients would demonstrate more apathetic (i.e. less severe) appraisals of care-based transgressions but harsher (i.e. more severe) ratings of rule-based moral transgressions compared to eAD and normal controls. We further hypothesized that increased ratings of severity of care-based moral transgressions would be associated with decreased cortical volume in the ATL whereas severe ratings rule-based transgressions would be associated with reductions in the OFC.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Sixty total participants (18 patients with bvFTD, 22 with eAD, 20 healthy controls) were recruited for this study from the Neurological Clinics of the University of California (UCLA) Medical Center. The patients with bvFTD were diagnosed according to International Consensus Criteria (Rascovsky et al., 2011). Diagnosis criteria included: apathy, loss of empathy, disinhibition, compulsive-like behaviors, and dietary changes that occur concurrently with disproportionate executive functioning in neuropsychological testing. Patients with eAD were diagnosed according to the guidelines of the National Institute of Communicable Disease and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association for clinically problem AD and subsequently verified with the National Institutes of Aging-Alzheimer Association criteria (McKhann et al., 2011). Additionally, in order to match with the younger bvFTD patients, only eAD patients were included. Individuals with major medical or non-dementia related psychiatric illnesses were excluded from the study (with the exception of hypertension and diabetes). None of the patients had a history of criminal behavior and were considered “good citizens” by their caregiver. The study was reviewed and approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) and participants were enrolled according to IRB procedures.

2.2. Procedures

Each participant completed an initial screening interview and standard neurological examination. The participants completed the Moral Behavioral Inventory (Mendez et al., 2005); the Social Norms Questionnaire (Rankin, 2008); Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; (Nasreddine et al., 2005), the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR; (Morris, 1993) auditory comprehension (modified from Boston Aphasia Battery) (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1983), DKEFS Proverbs (Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001), Trailmaking A & B (Tombaugh, 2004), Controlled Oral Word Associates Test (FAS) (Tombaugh, Kozak, & Rees, 1999); Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) (Kongs, Thompson, Iverson, & Heaton, 2000); and Western Aphasic Battery repetition subtest (Kertesz, 1982).

2.2.1. Neuroimaging

The bvFTD and eAD patients underwent MRI using a standardized protocol on a 1.5T high-resolution scanner. Images were acquired in the coronal plane using an MPRAGE sequence with the following acquisition parameters: TR=2000 ms, TE=2.49 ms, TI = 900ms, flip angle = 8°, slice thickness = 1mm, 25.6 cm field of view, voxel size = 1.0×1.0×1.0 mm3. Two cortical labels were extracted per hemisphere, from the Desikan-Killiany atlas from all native space T1-weighted structural MRI scans using FreeSurfer version 5.3 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/)(Desikan et al., 2006). For best results, the FreeSurfer cortical delineations were manually adjusted as needed using controls points in the white and gray matter structures. For each cortical label, or region of interest (ROI), we extracted the cortical thickness as output by FreeSurfer.

2.2.2. Instrumentation

The Moral Behavior Inventory is a questionnaire consisting of 24 items based on prior moral questionnaires and inventories but updated to the current U.S. population (Mendez et al., 2005). The participant was asked to rate various behaviors (e.g., driving after one drink) as “not wrong,” “mildly wrong,” “moderately wrong,” or “severely wrong,” on a 4-point Likert scale. In our preliminary study, the split-half reliability (Cronbach's coefficient alpha) for 78 participants was rk k= .73. The Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ, Rankin 2008) is a 22-item inventory used to measure perceptions of abnormal social behavior. Respondents are asked if a certain behavior is social acceptable, answering with either “yes” or “no.” In order to facilitate administration and comprehension in dementia patients, the items were read aloud to the participants. The items were repeated as many times as necessary to assure comprehension.

Subsequently, these items were analyzed by three members of the research team using an iterative, grounded theory process. Using Gilligan’s (1987) conceptual framework, care-based behaviors was defined grounded in mutuality, respect, and responsiveness for each involved party. In contrast, rule-based behaviors were grounded in Kohlberg’s (1971) notion of conventional behavior based on social norms that are to be followed all circumstances. MBI and SNQ directly tap into sociomoral behavior and, therefore, must be divisible into these literature derived care and rule-based items. Each item was coded to reflect the type of moral behavior reflected in each item. Each coded item was placed in its respective category (inter-rater reliability κ=.81). A category score was created by adding the sum of each individual item score. Each scale yielded adequate internal consistency (α’s = .76–.78) by the three person team. A group of 15 people comprised of physicians, students, and research assistants were asked to further validate these categorical scales. They were given a copy of the MBI and SNQ items with the operational definition of both care-based and rule-based behavior located at the top of the page, and they were asked to make a force choice decision whether the item was “care” or “rule” based moral behavior. These scales were analyzed using Hayes and Krippendorff (2007)’s macro yielding acceptable inter-rater reliability (care-based Krippendorff’s α =.79, LLCI .61, ULCI .85; rule-based Krippendorff’s α = .81, LLCI .60, ULCI .89).

2.3. Statistical analyses

Each statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 21.0 software. Demographic (age, race, education) descriptive statistics were generated for each group. Next, these characteristics were compared between the groups using Chi-square and t-test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Pearson correlations were computed to examine the relations between the moral behaviors and demographic variables to identify any covariants. The formal hypotheses that postulated group differences in moral behavior were tested by analyses of variance (ANOVAs). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVAs) was utilized when the correlation analyses identified study variables with significant relationships with demographic variables. The main effects were compared using the Sidak confidence interval adjustment set at 95%. A series of bivariate correlations were used to explore possible neuropsychological and neuroantomical correlates. A Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons. To further test for any potential mediational properties, Hayes (2012) bootstrapping macro process was used. Confidence intervals were set at 95%.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

There were no significant participant group differences on any of the demographic variables (See Table 2). There was only one significant correlation between study and demographic variables; patient education had a positive correlation with severity of care-based moral judgments, r = .33, p = .010. In terms of neuropsychological profiles, as noted on Table 3, the bvFTD and eAD only differed by their CDR score, p = .009, after correcting for multiple comparisons. BvFTD patients were significantly more impaired on the CDR than their eAD counterparts. Compared to their eAD counterparts, bvFTD patients had a less right ATL (p = .004) and right OFC (p = .005) volume.

Table 2.

Group Demographics and Morality Ratings by Frequency or Means and Standard Deviations

| Demographic Variable | bvFTD N = 18 |

eAD N = 22 |

Healthy Control N = 20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.44 (10.78) | 59.59 (5.24) | 55.57(8.81) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 (55%) | 8 (33%) | 7 (34%) |

| Female | 8 (45%) | 14 (67%) | 14 (66%) |

| Education | 15.67 (2.64) | 16.41(2.00) | 16.00 (1.75) |

| Handedness | |||

| Right | 16 (89%) | 20 (91%) | 18 (90%) |

| Left | 2(11%) | 2 (9%) | 2 (10%) |

| Years since onset | 3.67 (3.03) | 3.64 (2.17) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 16 (89%) | 21 (95%) | 17 (81%) |

| Non-white | 2 (11%) | 1 (5%) | 4 (19%) |

| Care-based | 15.86 (8.23)* | 21.77 (4.50)* | 19.23 (3.68) |

| Rule-based | 13.00 (6.15)* | 10.45 (3.47) | 9.04 (3.15)* |

Note.

p<.05 according to Sidak pairwise comparison. Age, Education and Time since onset measured in years, M (SD). Gender and ethnicity measured by frequency of participants, n (percentage of sample). No significant differences exist by group on any demographic variable.

Table 3.

Neurocognitve Performance and Region of Interest Cortical Volume by Dementia Group

| bvFTD | eAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| MOCA | 18.67 | 6.04 | 19.17 | 5.61 | ||

| CDR** | 1.11 | 0.44 | 0.71 | 0.29 | ||

| Comprehension | −1.03 | 0.98 | −0.72 | 1.44 | ||

| Proverbs | −1.44 | 3.05 | −0.83 | 2.58 | −0.79 | 1.67 |

| Trails B | −1.88 | 1.70 | −1.83 | 0.93 | ||

| FAS*+ | −2.03 | 1.09 | −0.72 | 1.67 | ||

| WCST | 31.82 | 10.21 | 35.57 | 13.90 | ||

| WAB | 5.50 | 0.90 | 5.35 | 0.86 | ||

| L. ATL | 1516.06 | 689.03 | 1992.00 | 291.92 | ||

| R. ATL** | 1378.47 | 565.74 | 1934.41 | 296.48 | ||

| L. OFC*+ | 5110.18 | 1532.60 | 6253.05 | 838.79 | ||

| R. OFC** | 5291.35 | 1307.57 | 6083.68 | 898.16 | ||

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05

Not significant after Bonferroni correction. All anatomical volumes are calculated in mm3 units.

3.2. Group Differences on Care-Based vs. Rule-Based Items (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Standardized Ratings of Care-Based and Rule-Based Judgments of Moral Behavior

Note. * Group differences between bvFTD and eAD on care-based morality at p<.05 level according to Sidak pairwise comparison. ** Indicates group differences between bvFTD and healthy controls by rule-based morality at the p<.05 level according to Sidak pairwise comparison. Vertical axis represents total severity of rating moral behaviors in the Moral Behavioral Inventory and Social Norms Questionnaire. Error bars represent 1 SD.

An ANCOVA with patient education as covariate revealed significant overall group differences (ηp2= .07, F (1, 58) = 4.32, p <.05). For care-based moral behaviors, there was a significant group effect (ηp2= .16, F (2, 58) =3.74, p = .007). Sidak comparison procedure indicated that the bvFTD group rated care-based items significantly lower (less severe) than the eAD patients, p = .026. For rule-based moral behaviors, there was also a significant group effect (ηp2= .12, F (2, 59)= 3.93, p = .025). BvFTD patients rated rule-based behaviors more severely than healthy controls according to pairwise comparisons, p = .021.

3.3. Neuropsychological correlates

Correlations of moral behaviors and neuropsychological tests were demonstrated on Table 4. Care-based morality was associated with FAS, r = .48 p = .009. Rule-based behaviors were inversely associated with WAB Repetition, p = .021; and WCST total, p = .015. However only the relationships between WCST with rule-based morality and FAS with care-based morality remained significant after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 4.

Neuropsychological Correlates of Care-Based and Rule-Based Moral Behavior

| Care-Based | Rule-Based | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .12 | .08 |

| Education | .33* | .01 |

| MoCA | .16 | −.04 |

| CDR | .09 | .14 |

| Comprehension | −.10 | .05 |

| Proverbs | .18 | −.28 |

| Trails A | .01 | −.05 |

| Trails B | .20 | −.03 |

| FAS | .48** | .11 |

| WAB – Repetition | −.25 | −.41*+ |

| WCST | .11 | −.43* |

Note.

p< .05;

p< .01.

Not significant after Bonferroni correction.

3.4. Cortical volume correlates

Correlations of moral behaviors and cortical volume were demonstrated on Table 5 for the both dementia groups. Across groups, care-based morality was initially negatively related to volume in the left ATL lobe, p = .020, and right ATL, p = .009. Only the relationship with the right anterior lobe remained significant after multiple comparison correction. Rule-based morality however, had a negative relationship with the right OFC, p = .008. However, we did additional analyses to determine the strength of each relationship for each group. In bvFTD patients, rule-based morality was negatively linked to the right OFC, r = −.49 p = .010, but not left OFC, p = .135. Also in bvFTD, care-based morality was linked to the right ATL, r = .38, p = .031, but not the left ATL, p =.257. For eAD patients, rule-based morality was negatively linked to the right OFC, r = −.39, p = .015, but not to the left OFC, p = .091. Care-based morality was related to both the left ATL, r =.46, p = .017, and right ATL, r =.51, p=.004.

Table 5.

Regional Volume Correlations with Care-based and Rule-based Moral Behavior

| Care-based | Rule-based | |

|---|---|---|

| Left Orbitofrontal Cortex | .15 | −.28 |

| Right Orbitofrontal Cortex | .01 | −.41** |

| Left Anterior Temporal Lobe | .36*+ | −.10 |

| Right Anterior Temporal Lobe | .40** | −.15 |

Note.

p< .05;

p< .01.

Not significant after Bonferroni correction.

3.5. Neurocognitive mechanisms in morality

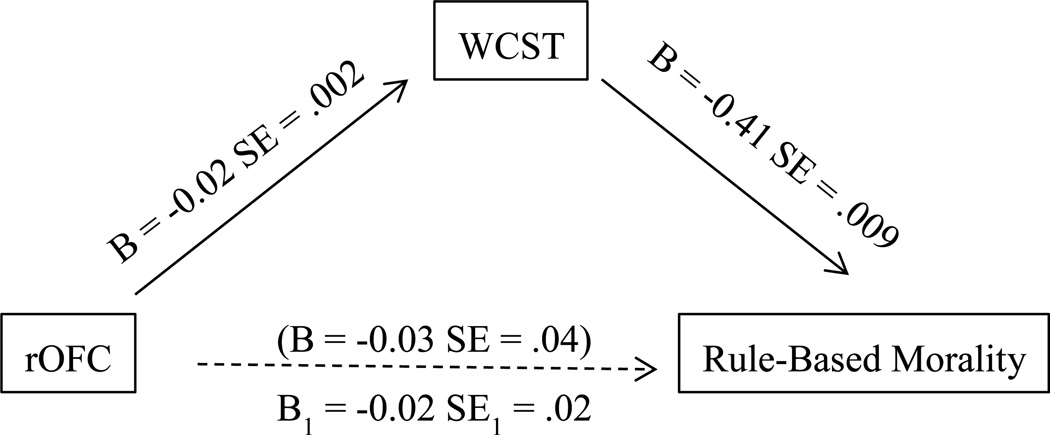

The neurocognitive mechanisms in rule and care-based morality were examined by mediation models using Hayes’s Model process. We first tested whether verbal fluency mediated the relationship between care-based morality and right ATL volume. However the right ATL did not significantly predict performance on verbal fluency (FAS), p = .584. Thus, mediation procedures were terminated. As illustrated in Figure 2, there was evidence that cognitive flexibility (WCST) mediated the relationship between rule-based morality and the right OFC (95% LCI = .05, 95% UCI .80).

Figure 2.

Mediation of Right Orbital Frontal Cortex on Rule-based Morality by WCST

Note. B is the effect size generated by bootstrapping procures. Figure in parenthesis indicates original relationship between rOFC and rule-based morality that was no longer significant when accounting for the WCST. B1 indicates the indirect effect of rOFC on Rule-Based Morality

4. Discussion

This study explored care-based and rule-based moral reasoning using bvFTD, in comparison to eAD and HC, as a window to their neuropsychological and neuroanatomical correlates. We found that bvFTD patients rated care-based morality transgressions less severely than the eAD patients and rule-based transgressions more severely than healthy controls. Severe care-based judgments correlated with increased verbal fluency and thinning volume in the right ATL, whereas rule-based reasoning correlated with increased difficulty on a set-shifting task and decreased cortical volume in the right OFC. Together, these findings suggest that disease involving right ATL and OFC in bvFTD results in a shift from empathic, care-based morality to an adherence to conventional rules.

As predicted group differences occurred with respect to both care-based and rule-based morality. Although neither group reached significant differences from healthy controls, the bvFTD patients rated care-based morality less severely than the eAD patients. Larger numbers might have revealed a significance difference from the HC as a directional trend appeared for bvFTD to rate care-based moral behaviors less severely. The discrepancy in care-based morality between bvFTD and eAD may be accounted for a number of ways. From a clinical syndrome perspective, decreased empathy is characteristic of bvFTD (Rascovsky et al., 2011); thus they would be likely to have decreased care-based moral reasoning which is reliant upon empathy.

Neuroanatomically, care-based moral transgressions were associated with reductions in right ATL volume, and the bvFTD patients had less volume in the right ATL. Several prior studies have indicated the prominence of the vmPFC-right ATL in empathy based moral functioning (Fumagalli & Priori, 2012; Gu, Hof, Friston, & Fan, 2013). In addition, given the right ATL lobe’s involvement in ToM (Irish et al., 2014), bvFTD patients may also have impaired moral reasoning from decreased social cognition. An impairment of the ATL, which lies next to and has strong bidirectional connection with temporal operculum of the insular and other limbic structures, may be enough to cause deficit in emotion awareness and empathy and lead to decreased care-based morality. This is partially supported by evidences showing a correlation between volume of ATL with empathy score (Rankin et al., 2006), and an altered neural activity in the temporal operculum, superior temporal sulcus, has been associated with callousness and psychopathy (Decety, Chen, Harenski, & Kiehl, 2015). In contrast, in eAD, the emotion-relevant Salience Network, which directly involves fronto-insular and anterior cingulate, (Seeley, Crawford, Zhou, Miller, & Greicius, 2009; Seeley et al., 2007; Seeley, Zhou, & Kim, 2012) tends to be spared and has recently been implicated in heightened emotional experiences or contagion among patients with AD (Sturm et al., 2013). In sum, lesions of the ATL may mediate impaired care-based morality, whereas, a release of Salience Network in eAD may heighten care-based moral reasoning.

Our hypothesis that bvFTD patients would rate rule-based moral transgressions more severely than their peers is also partially supported. The bvFTD patients have higher mean scores than other groups; this difference was statistically significant when compared to the healthy controls. This performance is consistent with prior studies that have found bvFTD patients tend to make calculated and impersonal moral decisions (Lough et al., 2006; Mendez & Shapira, 2009). This study further finds an inverse correlation between ratings of rule-based transgressions and volume in the right OFC, a region involved in social functioning. The correlation suggests that those with frontal lesions rely upon absolute principles as guides in complex cognitive and emotional social situations. However, as the mediation analysis indicates, this relationship depends upon the ability to set shift and learn from feedback. In this case, those with severe frontal dysfunction, held onto to the social norms unable to shift sets due to executive dysfunction. Thus when people are unable to understand the social context they rigidly apply the same logic, or rule-based reasoning, in impersonal ways.

Although the bvFTD patients were most rule-based, the absence of difference in rule-based moral behavior between bvFTD and eAD suggests that the eAD patients also tend towards rule-based moral reasoning. Both groups have deficits in social problem solving and ToM (Gregory et al., 2002; Kemp et al., 2012; Le Bouc et al., 2012). Both dementia groups may fall back to social rules on how to behave. The eAD patients, not as much as the bvFTD patients, have frontal dysfunction and might have a proclivity towards rule-based decisions.

Moreover, previous studies have highlighted the importance of the frontal executive system in rule tasks (Edwards, Balldin, & O’Bryant, 2014; Goodwin et al., 2012). This study demonstrates that when these executive functions become compromised, people become rigid in their application of particular social norms. When taken in tandem with the positive correlation of verbal fluency and care-based ratings, intact frontal-executive systems may enable prosocial socioemotional reasoning, regulate emotional states, and integrate information from social contexts. If these systems are compromised, people may have an inability to consider contextual information in making moral decisions thus rely upon previously learned social rules.

This study has potential limitations. Foremost, our study examines the behavior of a small and somewhat homogenous sample size. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates group differences in care-based and rule-based reasoning. Expanding the sample size in future studies can further elucidate these patterns noted in this study. Second, this study relies on behavioral scales to measure morality instead of clinical observation or responses to moral vignettes. These inventories represent subjects’ perception of behavior rather than observed occurrences. Behavioral inventories have demonstrated considerable reliability as stand-ins whenever direct observation is unavailable. Although caregivers reported the study participants were previously “good citizens” having no forensic history, this design did not assess moral behavior in real life. Future studies can compare similar inventories to real world moral behavior.

In summary, this investigation highlights differences in care-based vs. rule-based moral reasoning in two early onset dementia samples. Deterioration in areas involved in empathy seems to mitigate a person’s indignation of empathic-based judgments while increasing their reliance on social conventions. This pattern is particularly characteristic of bvFTD, but qualitative evidence indicates eAD patients react to rule-based infractions as well. These findings suggest examining moral behavior in dementia patients may be a window for understanding the neurological substrates of morality.

Table 1.

Care-Based vs. Rule-Based Items from MBI and SNQ judged to be

| Care-based | Rule-based |

|---|---|

| MBI Items | MBI Items |

| Are mean to someone you don’t like. | Keep money found on the ground. |

| Drive out the homeless from your community. | Take the largest piece of a pie. |

| Not offer to help after an accident. | Ask another to do some of your homework. |

| Ignore a hungry stranger. | SNQ Items |

| Refuse to help people who don’t deserve it. | Spit on the floor |

| SNQ Items | Cry in a public place |

| Tell a stranger you don’t like their hairstyle. | Wear the same clothing every day. |

| Laugh when a stranger trips and falls | Hug a stranger without asking first |

Highlights.

Studied care vs. rule-based morality in early onset dementia patients and controls.

EAD patients rated care-based infractions more severely than bvFTD patients

BvFTD patients rated rule-based more severely than healthy controls.

Care-based linked to right anterior temporal lobe; inversely with phonemic fluency.

Rule-based linked to reductions in right orbitofrontal cortex and set-shifting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (grant number 5R01AG034499-05) and a V.A. Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Care fellowship (ARC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allison Truett, Puce Aina, McCarthy Gregory. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2000;4(7):267–278. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Cipolotti L. Impaired social response reversal. A case of 'acquired sociopathy'. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 6):1122–1141. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok Danilo, Schilbach Leonhard, Vogeley Kai, Schneider Karla, Laird Angela R, Langner Robert, Eickhoff Simon B. Parsing the neural correlates of moral cognition: ALE meta-analysis on morality, theory of mind, and empathy. Brain Structure and Function. 2012;217(4):783–796. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0380-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli Fulvia, Happé Francesca, Frith Uta, Frith Chris. Movement and mind: a functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. Neuroimage. 2000;12(3):314–325. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety Jean, Chen Chenyi, Harenski Carla L, Kiehl Kent A. Socioemotional processing of morally-laden behavior and their consequences on others in forensic psychopaths. Human brain mapping. 2015;36(6) doi: 10.1002/hbm.22752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis Dean, Kaplan Edith, Kramer Joel H. Delis-Kaplan executive function system (D-KEFS) Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Desikan Rahul S, Ségonne Florent, Fischl Bruce, Quinn Brian T, Dickerson Bradford C, Blacker Deborah, Hyman Bradley T. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Melissa L, Balldin Valerie Hobson, O’Bryant Sid E. Neuropsychological Assessment and Differential Diagnosis of Cortical Dementias. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger Paul J. Neurological and neuropsychological bases of empathy. European neurology. 1998;39(4):193–199. doi: 10.1159/000007933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli Manuela, Priori Alberto. Functional and clinical neuroanatomy of morality. Brain. 2012;135(7):2006–2021. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass Harold, Kaplan Edith. Boston diagnostic aphasia examination booklet. Lea & Febiger Philadelphia, PA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin Shikha J, Blackman Rachael K, Sakellaridi Sofia, Chafee Matthew V. Executive control over cognition: stronger and earlier rule-based modulation of spatial category signals in prefrontal cortex relative to parietal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(10):3499–3515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3585-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene. Dual-process morality and the personal/impersonal distinction: A reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(3):581–584. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Nystrom Leigh E, Engell Andrew D, Darley John M, Cohen Jonathan D. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron. 2004;44(2):389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Sommerville R Brian, Nystrom Leigh E, Darley John M, Cohen Jonathan D. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science. 2001;293(5537):2105–2108. doi: 10.1126/science.1062872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene Joshua D, Paxton Joseph M, Raichle Marcus E. Patterns of neural activity associated with honest and dishonest moral decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(30):12506–12511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900152106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory Carol, Lough Sinclair, Stone Valerie, Erzinclioglu Sharon, Martin Louise, Baron-Cohen Simon, Hodges John R. Theory of mind in patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: theoretical and practical implications. Brain. 2002;125(4):752–764. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Xiaosi, Hof Patrick R, Friston Karl J, Fan Jin. Anterior insular cortex and emotional awareness. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2013;521(15):3371–3388. doi: 10.1002/cne.23368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes Andrew F. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes Andrew F, Krippendorff Klaus. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication methods and measures. 2007;1(1):77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Heekeren Hauke R, Wartenburger Isabell, Schmidt Helge, Schwintowski Hans-Peter, Villringer Arno. An fMRI study of simple ethical decision-making. Neuroreport. 2003;14(9):1215–1219. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200307010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish Muireann, Hodges John R, Piguet Olivier. Right anterior temporal lobe dysfunction underlies theory of mind impairments in semantic dementia. Brain. 2014 doi: 10.1093/brain/awu003. awu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant Immanuel. Preface to the metaphysical elements of ethics. 1909 [Google Scholar]

- Kédia Gayannée, Berthoz Sylvie, Wessa Michele, Hilton Denis, Martinot Jean-Luc. An agent harms a victim: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study on specific moral emotions. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2008;20(10):1788–1798. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp Jennifer, Després Olivier, Sellal François, Dufour André. Theory of Mind in normal ageing and neurodegenerative pathologies. Ageing research reviews. 2012;11(2):199–219. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz Andrew. Western aphasia battery test manual. Psychological Corp.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kongs Susan K, Thompson Laetitia L, Iverson Grant L, Heaton Robert K. Wisconsin card sorting test-64 card version (WCST-64) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bouc Raphaël, Lenfant Pierre, Delbeuck Xavier, Ravasi Laura, Lebert Florence, Semah Franck, Pasquier Florence. My belief or yours? Differential theory of mind deficits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2012;135(10):3026–3038. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lough Sinclair, Kipps Christopher M, Treise Cate, Watson Peter, Blair James R, Hodges John R. Social reasoning, emotion and empathy in frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(6):950–958. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez Mario F, Chen Andrew K, Shapira Jill S, Miller Bruce L. Acquired sociopathy and frontotemporal dementia. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2005;20(2–3):99–104. doi: 10.1159/000086474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez Mario F, Shapira Jill S. Altered emotional morality in frontotemporal dementia. Cognitive neuropsychiatry. 2009;14(3):165–179. doi: 10.1080/13546800902924122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill John Stuart. Utilitarianism. London, United Kingdom: Parker, Son & Bourn; 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Moll Jorge, de Oliveira-Souza Ricardo, Bramati Ivanei E, Grafman Jordan. Functional networks in emotional moral and nonmoral social judgments. Neuroimage. 2002;16(3):696–703. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll Jorge, de Oliveira-Souza Ricardo, Eslinger Paul J, Bramati Ivanei E, Mourão-Miranda Janaína, Andreiuolo Pedro Angelo, Pessoa Luiz. The neural correlates of moral sensitivity: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of basic and moral emotions. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(7):2730–2736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll Jorge, Zahn Roland, de Oliveira-Souza Ricardo, Krueger Frank, Grafman Jordan. The neural basis of human moral cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(10):799–809. doi: 10.1038/nrn1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris John C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993 doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Ziad S, Phillips Natalie A, Bédirian Valérie, Charbonneau Simon, Whitehead Victor, Collin Isabelle, Chertkow Howard. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehn Kristin, Wartenburger Isabell, Mériau Katja, Scheibe Christina, Goodenough Oliver R, Villringer Arno, Heekeren Hauke R. Individual differences in moral judgment competence influence neural correlates of socio-normative judgments. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2007 doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm037. nsm037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin KP. Social Norms Questionaire. NINDS: Domain Specific Tasks of Executive Function. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Rankin KP, Gorno-Tempini ML, Allison SC, Stanley CM, Glenn S, Weiner MW, Miller BL. Structural anatomy of empathy in neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 11):2945–2956. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky Katya, Hodges John R, Knopman David, Mendez Mario F, Kramer Joel H, Neuhaus John, Onyike Chiadi U. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(9):2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley William W, Crawford Richard K, Zhou Juan, Miller Bruce L, Greicius Michael D. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron. 2009;62(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley William W, Menon Vinod, Schatzberg Alan F, Keller Jennifer, Glover Gary H, Kenna Heather, Greicius Michael D. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley William W, Zhou Juan, Kim Eun-Joo. Frontotemporal Dementia What Can the Behavioral Variant Teach Us about Human Brain Organization? The Neuroscientist. 2012;18(4):373–385. doi: 10.1177/1073858411410354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevinc Gunes, Spreng R Nathan. Contextual and perceptual brain processes underlying moral cognition: a quantitative meta-analysis of moral reasoning and moral emotions. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e87427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav Amitai, Greene Joshua D. Moral judgments recruit domain-general valuation mechanisms to integrate representations of probability and magnitude. Neuron. 2010;67(4):667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits Lieke L, Pijnenburg Yolande AL, Koedam Esther LGE, van der Vlies Annelies E, Reuling Ilona EW, Koene Teddy, van der Flier Wiesje M. Early onset Alzheimer's disease is associated with a distinct neuropsychological profile. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2012;30(1):101. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm Virginia E, Yokoyama Jennifer S, Seeley William W, Kramer Joel H, Miller Bruce L, Rankin Katherine P. Heightened emotional contagion in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease is associated with temporal lobe degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(24):9944–9949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301119110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh Tom N. Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of clinical neuropsychology. 2004;19(2):203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh Tom N, Kozak Jean, Rees Laura. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Archives of clinical neuropsychology. 1999;14(2):167–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torralva Teresa, Dorrego Flavia, Sabe Liliana, Chemerinski Eran, Starkstein Sergio E. Impairments of social cognition and decision making in Alzheimer's disease. International psychogeriatrics. 2000;12(03):359–368. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner Perla, Stein-Shvachman Ifat, Korczyn Amos D. Early onset dementia: clinical and social aspects. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(04):631–636. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Dong Seok, Bertoux Maxime, Mioshi Eneida, Hodges John R, Hornberger Michael. Frontostriatal atrophy correlates of neuropsychiatric dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2013;7(1):75–82. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642013DN70100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Liane, Cushman Fiery, Hauser Marc, Saxe Rebecca. The neural basis of the interaction between theory of mind and moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(20):8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Liane, Saxe Rebecca. An fMRI investigation of spontaneous mental state inference for moral judgment. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2009;21(7):1396–1405. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn Moll, Jorge Iyengar, Vijeth Huey, Edward D, Tierney Michael, Krueger Frank, Grafman Jordan. Social conceptual impairments in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with right anterior temporal hypometabolism. Brain. 2009;132(3):604–616. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]