Abstract

Traditional vaccination against infectious diseases relies on generation of cellular and humoral immune responses that act to protect the host from overt disease even although they do not induce sterilizing immunity. More recently, attempts have been made with mixed success to generate therapeutic vaccines against a wide range of non-infectious diseases including neurodegenerative disorders. Following the exciting first report of successful vaccine prevention of progression of an AD animal model in 1999, various epitope-based vaccines targeting beta-amyloid (Aβ) have proceeded to human clinical trials, with varied results. More recently, AD vaccines based on tau protein have advanced into clinical testing too. This review seeks to put perspective to the mixed results obtained so far in clinical trials of AD vaccines, and discuss the many pitfalls and misconceptions encountered on the path to a successful AD vaccine, including better standardization of immunological efficacy measures of antibodies, immunogenicity of platform/carrier and adjuvants.

1. Conventional and Unconventional Vaccines

The history of vaccination began in 1798 when Edward Jenner published his study showing that a person previously infected by cowpox (the Latin root “vaccinus” meaning “from the cow”) was protected from smallpox and, moreover, deliberate infection with cowpox could protect against smallpox too[1, 2]. Eighty years later Louis Pasteur used a similar strategy based on attenuated bacteria to fight chicken cholera (anthrax bacteria)[2].

Today we have two categories of conventional vaccines: “attenuated live vaccines” and “inactivated or subunit vaccines”. Attenuated live vaccines stimulate strong cellular and humoral (antibody) immunity but have the disadvantage being “live”, thereby running the risk of causing serious infection in immunosuppressed individuals. They are also less stable than inactivated or subunit vaccines. Inactivated or recombinant vaccines are more stable and safe, but often at the price of reduced immunogenicity. To compensate for this reduced immunogenicity they are formulated with immune boosting compounds called adjuvants[3].

The major goal of conventional vaccines is to generate protective immunity, thereby protecting against overt clinical disease, even if not sterilizing. Different types of immune cells are involved in generation of such protective immunity. Normally, after administration of vaccines, professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) engulf, process and present vaccine-derived peptides through their MHC class I and II molecules. Subsequently, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells are activated when their antigen receptors (TCR) bind these peptides presented by MHC class I and II molecules, respectively. The CD4+ T cells become T helper (Th) cells that assist B-cell to produce antibodies and CD8 T-cell to differentiate into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). However, first B cells must receive an activating signal via cross-linking of their B cell receptors (BCR) by the relevant antigen. B cells internalize and present the processed antigen via their MHC class II to Th cells (so called “antigenic bridge”), thereby obtaining the second signal they need to start producing antigen-specific antibodies.

While conventional vaccines target foreign antigens expressed by infectious organisms, it is now recognized that the same basic process can be used to generate immune responses against either self-antigens, such as expressed for instance by cancer cells, or against completely synthetic antigens such as nicotine or cocaine. This has led to the field of “unconventional vaccines”. Thus, vaccines are no longer restricted to infectious disease applications, but potentially can be applied to treatment of a wide range of chronic diseases that include cancer, allergy, asthma, diabetes mellitus, autoimmunity, atherosclerosis, obesity, drug addiction and degenerative neurological diseases[4]. These vaccines work by stimulating neutralizing antibodies, or in some cases T cells, against relevant self or non-self molecules. Currently, the vast majority of approved vaccines are conventional[5–8]. Only two therapeutic vaccines (one conventional and one non-conventional) have been approved by FDA so far. More specifically, a conventional Varicella Zoster Vaccine (VZV) is used for treatment of herpes zoster in infected adults[9]. In addition, Sipuleucel-T is an approved therapeutic vaccine for advanced prostate cancer that targets the self-antigen, prostatic acid phosphatase and increases the median survival time by up to 4.5 months[10].

The generation of effective and safe therapeutic vaccines (both conventional and unconventional) is not simple and requires knowledge of the mechanism/s involved in activation and inhibition of cellular and humoral immune responses. As an alternative, passive vaccination strategies with humanized or fully human monoclonal antibodies (Mab) are widely used, for example in therapy of cancers, pneumonia due to respiratory syncytial virus, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, with over 40 Mab-based immunotherapeutics on the market or under review in US and EU [11], with many additional Mab in Phase II-III trials[12]. Other therapeutic approaches include adoptive cell transfer (ACT), where ex vivo activated/engineered and expanded clones of antigen-specific T cells are used for therapy of infections or cancer. However, passive administration of Mab and/or immune T cells is unlikely to be applicable to people not yet suffering from a disease even if at increased risk, because of the inconvenience, as passive vaccination generally provides only short-lived effects, thereby requiring regular injections as frequently as monthly in some cases. In addition, administrations of high concentrations of Mab (3–10mg/kg), or large numbers of immune T cells in the case of ACT, can have serious side effects including hypertension, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding, blood clotting, and organ damage. In addition, these remedies are extremely expensive, the cost of treatment with Mab being over $150K and cost of ACT potentially ~10 times higher again. We believe that, if safe and effective, an active immunization approach could potentially overcome many of these obstacles.

2. Active vaccines for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

In order to develop successful immunotherapeutic interventions for AD, it is first necessary to identify the molecules that are the key drivers of AD development, that can then be targeted by immune-therapy. For over two decades, Aβ peptides have been thought central to the onset and progression of AD, through the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’. This hypothesis suggests that toxic forms of Aβ (oligomers and fibrils) are associated with synaptic failure and neuronal death and initiate AD pathology [13–16]. Support for this hypothesis was spurred by the identification of mutations in APP in patients with AD[17], and also by development of AD-like pathology in mouse models overexpressing APP[18, 19]. Based on these findings, therapeutic strategies have been directed to reducing the level of Aβ in the brain, and/or blocking the assembly of Aβ peptides into pathological forms that disrupt cognitive function[20–22]. The seminal report of Schenk, et al. demonstrated that active immunization of APP transgenic (APP/Tg) mice with fibrillar Aβ42 antigen induced antibodies specific to Aβ and prevented the development of AD-like pathology in older animals[23, 24]. In addition, when older mice with preexisting Aβ plaques were immunized with Aβ42 they were able to clear the Aβ deposits from the brain[23–25]. Active immunization with Aβ42 protected APP/Tg mice from developing functional memory deficits[25–27] and passive administration of anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies to APP/Tg mice reduced Aβ levels in the brain[28, 29] and reversed memory deficits[30, 31]. Two possible mechanisms for antibody-mediated clearance of Aβ have been suggested: “Aβ clearance by entry of anti-Aβ antibodies into the CNS”[23, 28, 32–38] and “Aβ clearance by a peripheral sink whereby reduced systemic levels of Aβ result in increased transport of Aβ out of the CNS”[29, 39–42]. Regardless of the exact mechanism of action, such immunotherapeutic strategies have displayed strong disease modulating effects in animal models of AD, leading to attempts by industry to use active or passive anti-Aβ immunotherapy strategies in AD clinical trials[42–49]. Whilst these trials have had mixed results, recent excitement has been generated by early results from a BIIB037 phase 1 trial using a natural human Aβ Mab (aducanumab) cloned from a healthy human subject that recognized the disease-causing fibrillar form of Aβ[50, 51]. Hence, this recent trial provides strong support for the ongoing use of Aβ as a therapeutic target, but in current perspective we will focus primarily on active AD vaccination strategies as this is likely to be the most practical mean of protecting the broader population at risk of AD and, if safe enough, could potentially be used as a prophylactic measure across the entire elderly population, just as is currently the practice for infectious disease vaccines.

The first clinical trial of an AD vaccine, AN-1792, which used fibrillar Aβ42 formulated in QS21 saponin-based adjuvant was halted when ~6% of the trial subjects receiving the active vaccine developed some degree of aseptic meningoencephalitis[52–54]. Case reports of patients coming to autopsy from these trial suggested that aseptic meningoencephalitis was associated with autoreactive T-cell infiltration into the brains of immunized subjects[52, 54–57]. While these data suggest that meningoencephalitis was induced by active vaccination, still we do not know which component(s) of the vaccine was responsible for the adverse events: Aβ42 antigen itself, the pro-inflammatory saponin adjuvant, QS-21, or a combination of both. Speculation has also centered on the polysorbate 80 excipient, added as a component of vaccine formulation[42, 52, 53, 58] despite the fact that this emulsifier have been safely used as an excipient for many other medications[59]. Interestingly, suspicion has also fallen on polysorbate 80 in the aetiology of narcolepsy caused by the Pandemrix pandemic influenza vaccine[60, 61]. Again, the pro-inflammatory squalene oil AS03 emulsion adjuvant in the Pandemrix vaccine was also likely to have played a key role, given that similar pandemic influenza vaccines not containing AS03 adjuvant were not shown to be associated with narcolepsy[62, 63]. It was suggested that in people with the HLA subtype DQB1*0602, Pandemrix vaccine may have activated a subpopulation of CD4+T cells to the epitope/s mimicking the epitope in hypocretin. CNS penetration of these pathogenic T cells, possibly facilitated by polysorbate 80, might lead to recognition of hypocretin-producing neurons thereby causing narcolepsy[60, 61]. Therefore, as in case of Pandemrix, it could be suggested that formulation of Aβ42 vaccine in the pro-inflammatory QS21 adjuvant may have activated a high frequency of autoreactive T cells that in the presence of polysorbate 80 were able to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and thereby induce meningoencephalitis.

With respect to anti-Aβ antibody titers, responder subjects in the phase 1 trial were defined as those with Aβ42 IgG titers ≥1:1000 at 4 weeks after immunization or ≥1:5000 at any time point after an injection[64], whereas in the phase 2a trial this criteria was changed to Aβ42 IgG titers ≥1:2200 at any time after an injection 1[58, 65–67]. The number of responders was higher in the Phase 1 trial (56.9% of patients who entered the protocol extension likely because addition of polysorbate 80) compared to the phase 2a trial (19.7%) which may have occurred because patients received up to 8 doses of AN-1792 in the Phase 1 trial, while no patient received more than 3 doses in the Phase 2a trial[42, 58, 64, 65]. Although, data demonstrated significant individual variability of humoral immune responses in trial subjects, it was shown that relatively high anti-Aβ antibody titers correlated with a reduction in AD brain pathology in patients that later came to autopsy[52, 54, 55], suggesting a possible therapeutic benefit of the AN-1792 vaccine[58, 64, 65]. Notably, some AD patients with high anti-Aβ antibody titers also showed a trend toward slowing of cognitive decline[68], improvement in the memory domain of the neuropsychological test battery (NTB) and decreased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau levels[58]. The low percentage of responders and low overall anti-Aβ antibody titers (only 23.7% of AN-1792 responders generated titers > 1:10,000)[58, 64–66], likely reflect the reduced immunogenicity due to self-tolerance seen when vaccinating against any self-antigen [69] together with the low vaccine responsiveness typically seen in elderly people, a phenomena known as immunosenescence[70]. Interestingly, only AD patients with relatively high titers of anti-Aβ antibodies cleared amyloid plaques[67], although soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ were not reduced, and progressive neurodegeneration was not prevented[56, 57].

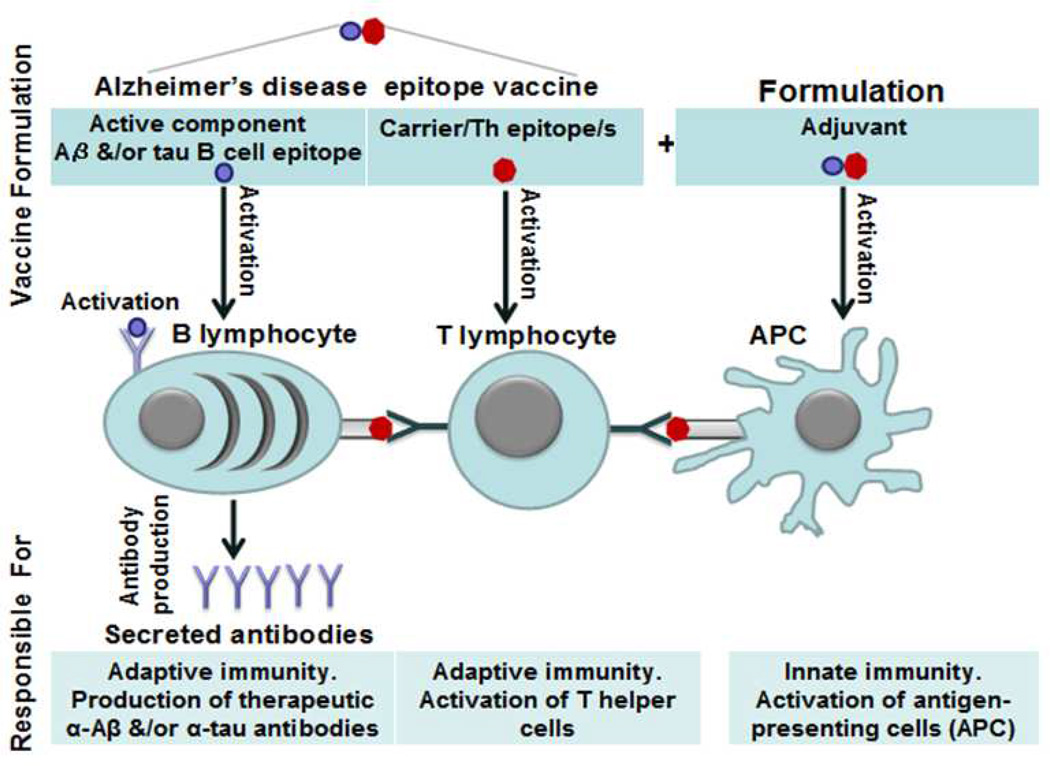

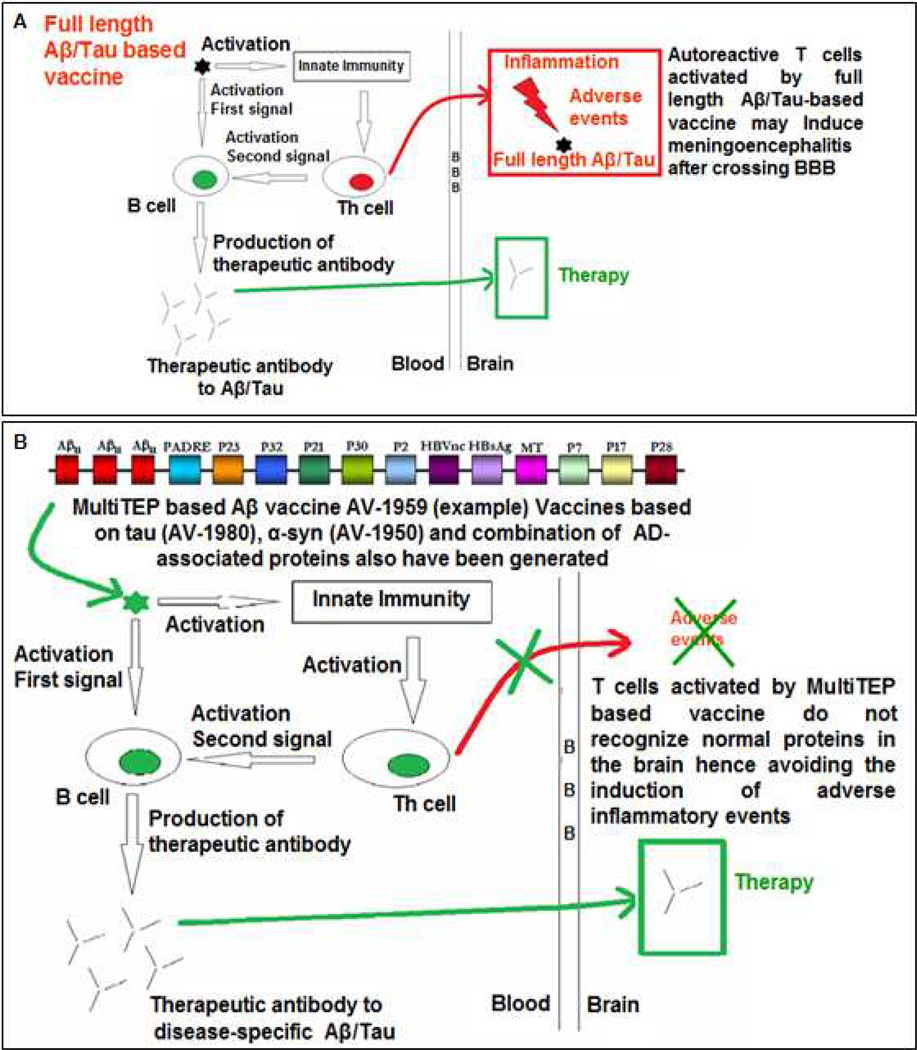

In sum, data from the AN-1792 trial somewhat suggested that an anti-Aβ vaccine could be effective if it is initiated before toxic forms of the Aβ peptide accumulate in the brain[48, 71, 72] and the vaccine is sufficiently immunogenic and able to induce high anti-Aβ antibody titers. It is also critical that any successful anti-Aβ vaccine avoid activation of autoreactive T-cells, or at the very least not induce autoreactive T cells able to cross the BBB. To avoid autoreactive T cells against Aβ various groups, including ourselves, have developed B-cell epitope AD vaccines composed of the more restricted B-cell epitope regions from within Aβ42 thereby omitting the key T-cell epitopes thought to have been responsible for initiation of meningoencephalitis[42, 45, 73–77]. As shown in Figure 1, an AD epitope vaccine needs an active B-cell epitope of the Aβ peptide that will bind to B cell receptors (BCR) and thereby induce production of protective anti-Aβ antibodies. As mentioned above for maximal antibody production and isotype switching, these anti-Aβ specific B cells require additional T-cell help, provided via T-cell recognition of peptides presented by B cells on their MHC class II molecules. It is thereby necessary to trick T cells to provide help to the Aβ-specific B cells, and this is done by creating a fusion protein expressing native Aβ B-cell epitopes fused to potent foreign T-cell epitopes, ideally derived from proteins to which individuals have previously been sensitized either through previous immunizations such as with tetanus toxoid, hepatitis B surface antigen, or non-toxic mutant form of diphtheria toxin (CRM197), or via previous infections, e.g. influenza antigens. Such epitope vaccines should be able generating of therapeutic concentrations of antibodies targeting pathological self-molecules responsible for AD pathology, while only boosting harmless T-cell responses against the foreign carrier molecule (Compare Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of T-cell dependent antigens and design of AD epitope vaccines. Normally Th lymphocytes recognized antigen that have been engulfed, processed and presented to these cells by APC (antigen presenting cells). These antigen-specific Th cells interact with activated antigen-specific B cells by binding to antigenic peptides presented on their MHC II molecules. Thereby such B cells after obtaining the second signal start production of high affinity antibodies.

Figure 2.

A. Full-length Aβ-based vaccine used in the AN-1792 trial induced therapeutic anti-Aβ IgG antibodies. However, this vaccine likely had induced Aβ specific T cells that crossed the BBB and caused meningoencephalitis. Such autoreactive T cells might recognize Aβ that have been picked-up, processed, and presented to them by activated microglia through their MHC class II/I molecules.

B. A safe Aβ-based epitope vaccine should not contain any self T-cell epitopes but instead should comprise foreign (non-self) Th-cell epitopes. These foreign Th cells activated by the vaccine will help Aβ specific B cells to secrete high, therapeutically effective levels of antibodies without the risk of inducing T-cell mediated meningoencephalitis. The same immunologically-potent foreign T-cell epitope bearing carrier can conveniently be used for the development of vaccines targeting other molecules involved in pathology of AD (e.g. tau, p-tau, α-syn, etc), by simply substitution of the self B-cell epitope in the vaccine construct.

2.1. Assessment of Aβ-based vaccine trials from an immunology standpoint

Based on the fact that switching of immunoglobulin heavy chain µ to γ in B cells requires a second signal from activated Th cells[78], the strategy described above has been used in development of various epitope vaccines that have subsequently been tested in mild to moderate AD subjects. All these vaccines have included a minimal B-cell epitope from Aβ comprising the unmodified or a modified N-terminus of Aβ conjugated to various carrier proteins or peptides designed to activate foreign Th cells[42–44, 79–81]. As mentioned above, aside from the safety issue of T-cell mediated meningoencephalitis, another major problem with the AN-1792 vaccine was its modest immunogenicity; high enough anti-Aβ antibodies required for a therapeutic effect were only seen in a small minority of subjects (see above and[65]). Hence even with redesign of the Aβ vaccine to remove self T-cell epitopes, further strategies may still be required to boost vaccine immunogenicity to a sufficient level. This will likely best be achieved by incorporation of a suitable adjuvant to boost the vaccine response. Whilst there are numerous adjuvants in various stages of development including the oil and water emulsions (e.g. incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, MF59, AS03, Montanide, Mas-1/MER5), saponins (e.g. QS21, ISCOMS), TLR agonists (e.g. monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), flagellin, CpG oligonucleotides), immunostimulatory particles (e.g. virosomes) and toxins (e.g. cholera toxin, E-coli latent toxin)[82, 83], it is still only the alum (aluminium salts/gels) class of adjuvants that is widely used in human vaccines. Not surprisingly, the majority of Aβ-based epitope vaccines, CAD-106, AD03, LU AF20513, that are in various stages of clinical trials are formulated in alum, while one of them, UB311 is formulated in the mixture of alum with CpG (see Table). Another vaccine in clinical trials, ACI-24 is utilizing the ability of the TLR4 agonist MPLA adjuvant to enhance immune responses and to induce T-cell independent B cell isotype switching from low affinity IgM to high affinity IgG[84]. We should also mention here the Neuroimmune’s DNA epitope vaccine, AV-1959D, which is planned to enter the clinical trials in three-four years, does not require an adjuvant, but requires electroporation-mediated delivery system to generate strong immune responses[76, 85]. At the same time, in three vaccine trials that have been recently halted for lack of efficacy, e.g. AD02[86], or for unknown reasons (e.g. ACC-001 and V-950[81, 87, 88]) companies used not only alum, but also QS21 and ISCOMS (see Table). Unfortunately, only limited data from clinical trials have been published so far in peer-reviewed journals[89–91], and without such comprehensive data it is extremely hard to evaluate the relative immunological efficacy of different AD vaccines formulated in abovementioned adjuvants. It is unfortunate, because the some preliminary results with fully human monoclonal IgG1 antibody, aducanumab specific to Aβ plaques, but not monomers have been reported at AD/PD conference in France[50, 51]. Although, comprehensive clinical data on aducanumab are not published yet, dose-dependent reduction of amyloid deposition in 6 cortical regions of the brain of prodromal or mild AD patients was reported. Importantly, after 1 year, the highest dose of aducanumab induced the greatest reduction in brain amyloid, resulting in standardized uptake value (SUV) ratio close to a commonly used threshold of positivity. Data for the mini–mental state examination (MMSE) and clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes scores (CDR-SB) measures showed slower worsening compared with placebo group by one year. These early unpublished results were statistically significant for aducanumab doses of 3mg/kg and 10mg/kg supporting the hypothesis that amyloid reduction confers a clinical benefit[50]. At the same time, data presented at AD/PD conference indicated that the incidence of cerebral edema (ARIA-E) was dose-dependent with incidences of 5%, 43%, 55% in the 1–3mg/kg, 6mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg, respectively, in ApoE4-carriers, and 9%, 11%, 17% in the 3 mg/kg, 6 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively, in ApoE4 non-carriers[51].

Table.

Clinical trials with epitope vaccines targeting Aβ pathology in mild to moderate AD patients

| Sponsor | Vaccine | B cell epitope of self antigen, Aβ42 |

Carrier molecules/non self Th epitopes + Adjuvant |

Anti-Aβ antibody response |

Antigen Specific Th cell response |

Status | *Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD106 | Cytos/Novartis | Aβ1 –6 | Bacteriophage Qβ + Alum |

**+/− | NR | Phase 2 | [89] |

| ACI-24 | ACImmune/Roch e/Genentech |

Aβ1–15 | Liposomes+ MPLA |

NR | NR | Phase 2 | NA |

| UB-311 | United Biomedical |

Aβ1–-14 | Proprietary UBITh® epitopes +Alum/CpG |

NR | NR | Recently Initiated Phase 2 |

NA |

| AD03 | AFFiRiS GlaxoSmithKline |

Pyroglutamate- modified N-terminal Aβ |

KLH+ Alum | NR | NR | Phase 1 completed |

[90] |

| AD02 | AFFiRiS GlaxoSmithKline |

Mimicking Aβ1–6 | KLH + Alum | NR | NR | ***Discontinued | [90] |

| ACC001 | Pfizer/Jansen | Aβ1–7 | Diphtheria Toxin + QS21 |

**+ | NR | ***Discontinued | [91] |

| V950 | Merck | Aβ1–15 | Carrier Unknown + ISCOMATRIX™ |

NR | NR | ***Discontinued | NA |

| LUAF20513 | Lundbeck/Otsuka | Aβ1–12 | Th epitopes (P2 & P30 from Tetanus)+ Alum |

ND yet | ND yet | Phase 1 Recently Initiated |

Recently initiated NA |

Ref presented only for papers published in peer-reviewed journals, no abstract has been cited. NA-not available in PubMed and Cochrane Library.

Antibody titers were presented by Units, which are not completely clear. Even in these units the response is low.

See AlzForum

These data somewhat support “amyloid hypothesis” and may indicate the requirement of relatively high concentrations of anti-Aβ antibodies (≥3mg/kg) in prodromal subjects and mild AD patients. Interestingly, data from two phase 3 trials of the anti-Aβ based monoclonal antibodies, bapineuzumab and solanezumab[92, 93] also suggested that to be effective immunotherapy should be initiated at earlier stages of AD pathology. Interestingly, the National Alzheimer’s Project Act recently supported efficacy testing of anti-Aβ antibodies in subjects with very early stages of AD and in asymptomatic people at risk for AD (preclinical AD). The National Institute of Aging/Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) working groups and the International Working Group (IWG) have proposed guidelines for new definitions for such preclinical AD (subjects with risk factors, family history, and dominant mutations) and early clinical stage AD (prodromal)[94, 95]. Accordingly, three new anti-Aβ immunotherapy studies have been initiated: (i) a 770-patient Phase II/III study of gantenerumab in prodromal and mild AD[96], (ii) the 210-patient DIAN study in individuals with inherited autosomal-dominant Aβ mutations[97], and the ADCS/A4 trials in normal individuals with positive “Aβ/PetScan” test[98, 99].

Collectively, data from three clinical trials with aducanumab, solanezumab, bapineuzumab, and newly initiated immunotherapeutic studies outlined above suggest that to be effective an active vaccine (i) should be initiated in prodromal subjects or at earlier stages of AD pathology to minimize synaptic and neuronal loss; (ii) should induce anti-Aβ antibodies at concentrations that are comparable to that used in passive vaccinations trials. Unfortunately, despite the data presented above and the general consensus that anti-Aβ immunotherapy might be more effective if used “prophylactically” in asymptomatic subjects at risk of AD, so far all active vaccines outlined in the Table were conducted in subjects with mild-to-moderate AD (to the best of our knowledge, the exception is the Neuroimmune that planned to initiate the AV-1959D vaccine trials in prodromal AD subjects). Moreover, although vaccine formulations have been shown to generate potent concentrations of anti-Aβ antibodies that were able to clear AD-like pathology and improve cognitive functions in transgenic mice, there is no data yet reported on an active vaccine that has been uniformly effective in Phase 2 clinical trials. This begs the question: were AD vaccines sufficiently immunogenic (inducing adequate concentrations of antibodies) in elderly people with mild to moderate AD? If not, the negative trials results to date do not disprove the anti-Aβ antibody effectiveness, as this can only be disproved if a positive effect is still not seen despite use of a highly immunogenic vaccine. Only then should we accept anti-Aβ vaccine as the potential therapy and maybe consider moving on to alternative AD vaccine targets such as tau protein for later stages of AD[81, 100].

How immunogenic is “immunogenic enough”? In general, the amount and avidity of serum antibodies induced to Aβ in animal models has been shown to directly correlate with vaccine efficacy[75, 101–103]. To be effective, an AD epitope vaccine should induce strong Th cell responses to maximize B cell antibody secretion (Figure 1, Figure 2). Without strong Th cell responses the level and avidity of anti-Aβ antibody is unlikely to be capable of clearing Aβ-mediated pathology from the brains of AD subjects. Thus, to know if an AD vaccine is likely to be effective in patients it is necessary to be able to accurately measure both the extent of Th cell activation as well as exactly assess the quantity and quality (avidity, epitope specificity) of anti-Aβ antibody. Evaluation of antigen-specific Th cell responses in clinical trial subjects can be conducted using peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation assays (e.g. H3Td incorporation or CFSE flow cytometry assay); detection by ELISPOT of T cells producing specific cytokines (e.g. IFNγ ELISPOT assays); flow cytometric analyses of intracellular cytokines or measurement of antigen-specific T-cell frequencies using MHC tetramers[104]. Such evaluations are particularly important as in elderly people with immunosenescence the number of T cells that respond to vaccination is dramatically decreased[70, 105, 106]. Unfortunately, there is only one short report regarding antigen specific T-cell immunity in patients in the AN-1792 trial[107]. There are no T-cell immunogenicity reports for the AD epitope vaccines outlined in the Table, and hence it is impossible to know if these trials might have failed because they failed to induce sufficient T-cell help. Thus, we think that standardized, well-validated and generally accepted assays are required for measurement of T-cell responses specific to non self-epitopes presented in carrier/vaccine platform and such methods will allow full comparison of different AD vaccines. Such tests can be developed by immunologists and vaccine researchers from universities and companies with the help from national Neuroscience Associations, as well as NINDS, NIA-AA working groups and IWG.

The other important issue is how best to assess the immunogenicity of AD vaccines in the absence of well-standardized assays of humoral immunity to Aβ. Published data clearly suggest that Aβ antibody levels induced by AD vaccines correlate with the probability of a positive clinical outcome[67]. However, there is no agreement on the optimal methods for measurement of Aβ antibodies, or how the results of such assays should be reported. Many different methods can be used to measure titers and avidity of Aβ antibodies, including immunochemistry, Western blot, ELISA, competitive ELISA, and surface plasmon resonance. The simplest means of measuring Aβ antibodies in the serum of vaccinated individual is by ELISA. While many Aβ-based epitope vaccine human trials have been completed, only three papers, one on the AD02 trial[90], the CAD106 trial[89, 108], and more recently, ACC-001 trials [91] have been published[42, 43, 49, 81]. Unfortunately, these papers are either very brief and do not provide sufficient immunogenicity data[90], or report the immunogenicity of the vaccine using different measurement units[89, 91] that do not allow to enable benchmarking or comparison with the results of other AD vaccine studies. Hence, insufficient information is available on the level of anti-Aβ antibodies generated by vaccination and the method of assay used in the trial. For example, in the CAD106 trial, the quantification of Aβ antibody titers was stated to be performed relative to a calibration curve obtained from an IgG serum pool from rhesus macaques immunized with CAD106, in our opinion this approach is not correct[89]. In addition, mean antibody titers after vaccinations with CAD106 were calculated in a very complex way. Although the report concluded “CAD106 has acceptable antibody response in patients with AD”[89], it is not possible to know from the presented data what was considered by the investigators to be an ‘acceptable antibody response’ and how they reached this conclusion. It is unclear why endpoint titers of anti-Aβ antibodies were not presented in the CAD106 study report, as done in the AN-1792 trials[58, 64–67]. The CAD106 abstract states that “anti-Aβ antibodies display a higher binding affinity for antigen peptides after repeated CAD-106 injections”[109], however, neither the binding affinities, nor the methods used to measure the affinity were mentioned in this abstract, so it is not clear what the investigators considered as a higher binding affinity of anti-Aβ antibodies. In the recently published results of the ACC-001 (Vanutide Cridificar) Aβ vaccine Phase 2 trial in Japanese subjects antibody responses were measured in a simple ELISA and presented as geometric mean titers (GMT), as was done in AN-1792 trials[58], but again presented in undefined Units/mL[91]. Interestingly, authors mentioned that “ titers elicited by ACC-001 + QS-21 appear higher than those observed in the CAD106 phase 1 study, but methodological differences preclude any comparison”. Hence the way in which AD vaccines data is currently presented makes it impossible to compare between each trial the true magnitude of the humoral immune responses to Aβ. Importantly, this prevents any meta-analysis to link together data from various AD vaccine trials to try, for example, to identify a threshold level of anti-Aβ antibodies predictive of AD vaccine efficacy. Consequently, human data on the immunogenicity or lack thereof, both cellular and humoral, of current AD vaccines (see Table) remains completely obscure.

For the AD vaccine field to advance, it will be extremely important to develop standardized and well-validated assays for measurement of the functional activity of anti-Aβ antibodies. For example, it might be possible to develop assays to measure the functional ability of antibodies to neutralize toxicity of pathological AD molecules[85, 110–112], block their oligomerization[113–115], or compete with the binding to natural oligomers and/or fibrils (e.g. plaques, tangles). In addition, assays of antibody avidity such as surface plasmon resonance could also aid in the evaluation of AD vaccine efficacy[85, 110]. Importantly, standardized and well-validated assays need to be developed not only for vaccines targeting Aβ, but also for vaccines targeting other molecules involved in AD pathology, e.g. tau protein and α-synuclein. We would strongly argue that the measurement of anti-Aβ antibodies today is at the same stage as the measurement of islet cell autoantibodies in the type 1 diabetes mellitus field was 30 years ago. That was the time that international standardization workshops were recognized as being needed to co-ordinate efforts in the diabetes field to calibrate and standardize the various research assays being used in the field to measure islet cell antibodies[116], work that later extended to other specific antibodies including insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) and IA2 protein phosphate autoantibodies, as they were discovered[117]. These workshops by providing samples in a blind fashion for assay, confirmed which assays were truly predictive and which assays were completely useless in their claimed ability to measure such antibodies. These workshops were driven by the recognition that for type 1 diabetes clinical research to move forward, it was essential that the assays being used by the various research groups, even if not standardized to a common assay platform, be calibrated by establishment of a common panel of positive and negative control samples, thereby enabling the performance of all assays from which data was being published to be compared. Through an iterative process, which in the T1D autoantibody field has now extended over 30 years and is still ongoing[118], the best performing, most reproducible and sensitive assays are progressively identified, international positive and negative standards developed and regular workshops held to discuss the results[119]. In fact this standardization work has been so successful that it has even extended to international workshops to standardize T-cell assays for use in type 1 diabetes research[120].

There is, thus, an urgent need for similar efforts in the AD research field to establish common standards for Aβ antibody and Th cell assays for use in identifying the most sensitive and reproducible methods, and to allow results between different assays and different clinical trials to be directly compared. We suspect that most, if not all, previous active Aβ vaccine trials failed because they only induced low titers of functional anti-Aβ antibodies that are not comparable to therapeutic concentrations of aducanumab, but, of course without standardized antibody assays this cannot be proved one way or the other. We therefore hope that standardized assays will be developed and made publicly available in the nearest future, may be by newly established international standardization workshops with a strong leadership, that should ideally come from a representative body or institution with an interest in advancing the field of research, which in case of AD can be National Neuroscience Associations, NIA-AA working groups and IWG.

2.2. Anti-tau epitope vaccines for AD

While we were preparing this perspective, two anti-tau human vaccine trials have been initiated in AD patients [121–123] based on positive findings in pre-clinical studies outlined below. A major hallmark of AD is neurofibrillary tangles, which are twisted protein threads made up of abnormally phosphorylated tau (p-tau) protein. In human brain the alternative splicing of tau gene transcript leads to generation of six isoforms of protein that differ by the number of N-terminal inserts which consist of 29 amino acids (0N, 1N and 2N) and tubulin binding repeat domains of 31–32 amino acids (R3 and R4)[124, 125]. The relationship between tau and Aβ in progression of AD pathology is still controversial with the majority of data supporting Aβ being the primary event in AD pathogenesis with secondary triggering of pathological tau production[126–128]. Nonetheless, accumulation of pathological tau in the brains correlates well with dementia in AD patients[124, 129–131]. Thus, by the time AD clinical signs appear, there is already substantial tau pathology in the brain[132, 133]. Importantly, several studies have shown that tau can be released and internalized by neurons[134–140]. Hence self-propagating extracellular p-tau molecules may be a good target for immunotherapy[100, 141, 142].

The efficacy of an anti-tau vaccine was first shown in 2007 with the demonstration that immunization of JNPL3 mice over-expressing human mutated tau-P301L with a tau-derived peptide spanning amino acids 379–408 (p396/p404) generated antibodies against p-tau and reduced tau pathology with amelioration of associated sensory-motor deficits[143]. Subsequently, an antibody specific to the same tau epitopes was shown to improve cognitive performance in htau/PS1 mice[144]. Immunization of double mutant (K257T/P301L) mice with tau195–213 (p212/p214) and tau224–238 (p231) significantly reduced the levels of neurofibrillary tangles in the CNS of vaccinated animals, and they did not develop encephalomyelitis[145], a problem encountered after immunization of wild-type mice with unphosphorylated full-length tau[146]. Tau pathology was also reduced in young, middle aged and old tau-P301L transgenic mice immunized with tau391–401 (p396/p404) linked to a carrier protein[147]. More recently it was shown tau417–441 or tau420–426 (in both peptides they used p422) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) carrier protein reduced both pS422, as well as pY212/pS214 tau species and slightly, but significantly improved cognitive deficit in a very aggressive Thy-tau22 tauopathy mouse model, in which the transgenic mice express human 1N4R Tau mutated at sites G272V and P301S)[148–150]. Passive immunization with anti-tau antibodies specific to p-tau antigenic determinants similarly reduced tau pathology and improved motor function of JNPL3 mice[144, 151, 152].

Notably, the therapeutic efficacy of antibodies specific to non-phosphorylated tau was also demonstrated. More specifically, it was shown that monoclonal antibodies specific to tau25–35 that are capable of inhibiting propagation from cell to cell, may reduce tau pathology, and improve cognitive functions in PS19 mice after icv infusions[136, 153]. Infusion for 3 months of high concentrations of antibodies specific to N-terminal region of tau into the lateral ventricle of P301S mice reduced hyperphosphorylated aggregated insoluble tau, reduced microglial activation and improved cognitive deficits[136]. Another group tested the Mab specific to oligomeric tau conformational epitope in JNPL3 (P301L) mouse models of tauopathy. Remarkably, a single intravenous injection of Mab cleared oligomeric tau, rescued the locomotor phenotype, and reversed the memory deficits associated with oligomeric tau pathology[154].

Importantly, currently two active vaccines targeting both non-phosphorylated (AADVac1) and phosphorylated tau (ACI-35) peptides have entered phase 1 clinical trials based on positive efficacy studies in tau Tg rat and mouse models, respectively[121, 151]. AADVac1 (Axon Neuroscience SE) targeting the regulatory domain driving the oligomerization of tau (294–305aa fragment) incorporates the KLH carrier and aluminum hydroxide adjuvant is tested in mild to moderate AD subjects. Although the investigators propose to measure humoral immune responses to tau peptide and AADVac1, they have not indicated an intention to measure T-cell responses in these trials[122, 155]. AC-Immune have adapted their liposome-based vaccine platform currently used for targeting Aβ (ACI-24), by integrating tau393–408 (pS396/ps404) into liposomes using two palmitic acid chains attached to both peptide termini. As in case of their anti-Aβ1–15 vaccine (ACI-24), the ACI-35 vaccine incorporates TLR4 agonist, MPLA as an adjuvant to induce B-cell isotype switching from IgM, which dominates T-independent B-cell responses to the higher affinity IgG isotype. Although no information is available about the planned primary and secondary outcomes for the ACI-35 trials (http://www.wwctrials.com/ and https://clinicaltrials.gov/), and the vaccine does not contain Th cell epitopes, it will still be important to measure not only the antibody responses to tau but also Th cell responses to tau393–408 (both p-tau and tau peptides). Hence, development of standardized and well-validated methods for detection of anti-tau/p-tau antibody titers and Th cell responses is needed for future tau vaccine clinical trials similar to anti-Aβ vaccine trials discussed above.

3. Perspective for AD-Immunotherapeutics

A critical step in developing therapeutic interventions for AD has been the identification of suitable targets. We should mention that although there are many pre-clinical strategies targeting various immunological molecules that are presumably involved in pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, such as TREM2[156, 157], CD40/CD40L[158–160], TLRs[161], ApoE4[162], IL-10[163, 164] and TGF-β pathway[165]. However, discussion of these immunotherapeutic strategies that are also mostly associated with a reduction of pathological Aβ is not the subject of this review.

Although pathological Aβ may be a primary event in AD pathogenesis, pathological tau also plays critical role in AD progression[124]. Importantly, by the time clinical signs of AD appear, there is already a considerable self-propagated tau pathology in the brain[134–137]. Hence, anti-Aβ immunotherapeutics are likely to be most effective if initiated at a very early stage of disease to minimize synaptic and neuronal loss, as supported by passive vaccinations trials[50, 93]. Accordingly, currently, several clinical trials are testing whether anti-Aβ Mab can decrease amyloid production in presymptomatic (cognitively normal) individuals at risk for AD, e.g. positive for AD-pathophysiological markers including detection of brain Aβ/PetScan, detection Tau/Aβ or pTau/Aβ ratio in CSF, detection of cerebral metabolic rates of glucose Pet FDG, or structural MRI[94, 95]. However, due to the costs associated with long-term treatment with Mab, a passive vaccination strategy may not be practical or affordable for the treatment of asymptomatic, prodromal AD, or even mildly cognitively impaired individuals. If it is confirmed that anti-Aβ Mab can significantly improve or, more realistically, slow cognitive declines, it would be much more practical to use knowledge of the B-cell epitopes recognized by successful Mab to design active vaccines using immunologically potent carriers. Regardless of the B-cell epitope used in active vaccines, it will be critical that they are able to generate therapeutically effective concentrations of anti-Aβ antibodies, which should be comparable to the concentration range generated by therapeutic Mab, namely 30–150µg/ml (approximate serum level achieved by 3–10mg/kg of Mab at time of injection). For that it will be central to develop standardized and well-validated methods for detection of anti-Aβ antibody concentrations.

In the next 3–5 years, we can anticipate more human trials of Mab and active vaccines targeting both p-tau and tau. Given the differing roles of pathological Aβ and tau during AD progression [132] anti-tau immunotherapies will be likely more effective in late stage disease with anti-Aβ immunotherapies most effective in presymptomatic AD, MCI and mild stages of AD. The chronological model of AD biomarkers indicates that there is a link between these two pathological processes, and targeting both biomarkers subsequently might be necessary for prevention/inhibition of disease progression and cognitive decline. If so, it would be beneficial to generate two vaccines composed of relevant B cell epitopes of Aβ or tau fused with the same immunogenic carrier responsible for activation of Th cells of identical specificity. In that case, one can initiate Aβ immunotherapy in the preclinical or very early stages of AD and switch or add tau immunotherapeutic when clinical symptoms become apparent. We should expect that such protocol would allow activating both naïve Th cells and preexisting memory Th cells specific to the same immunogenic carrier and quickly induce robust anti-tau responses. Ultimately, if positive clinical trial data continues to be forthcoming from both anti-Aβ and anti-tau strategies, it is also possible that dual-specificity vaccines will next be developed that target both Aβ and tau pathological molecules simultaneously. Development of such vaccines would be greatly assisted by identification of a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant able to boost Th responses and antibody titers to both Aβ and tau without compromising AD vaccine safety. Lastly, we believe that the AD vaccine field would benefit tremendously from greater efforts to develop and standardize immunological assays for use as surrogates of efficacy in preclinical models and human vaccine trials.

Box 1.

The immune system is complex with multiple cell types working together to provide protection from multiple foreign or self-threats. There are two types of adaptive immune responses: humoral immunity, mediated by B-cell produced antibodies and cellular immunity, mediated by T cells. To produce potent concentrations of high affinity IgG antibodies B cells normally require help from specific CD4+ T-helper (Th) cells[78].

Box 2.

Vaccines provide new opportunities for treatment of neurodegenerative disorders by targeting proteins involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Aβ, tau and α-synuclein[23, 24, 142, 166]. However a major unanswered question is whether vaccines targeting these proteins will be effective in elderly patients with AD pathology? To date, the AN-1792 and AD02 trials failed to improve cognitive function and at least two other Aβ epitope vaccines (ACC-001, V950) have been discontinued for various, sometimes unclear, reasons. While no active Aβ vaccines have yet to be tested in preclinical or prodromal AD subjects, some results from passive immunotherapy trials suggest that to be effective Aβ epitope vaccines should be (i) initiated as early as possible in prodromal AD subjects, people at AD risk, or at least in mild AD patients; and (ii) able to induce therapeutically potent titers of antibodies.

Box 3.

Recently, the NIA-AA working groups and the International Working Group (IWG) proposed research criteria for three preclinical stages, and clinical criteria for early clinical (prodromal AD) and clinical (mild, moderate, severe) stages of AD[94, 95]. Subjects in the preclinical stages are asymptomatic cognitively normal people that have a positive Aβ/PetScan (stage 1), positive Aβ/PetScan and neurodegeneration [(Tau, FDG, MRI); (satge 2)], positive Aβ/PetScan, neurodegeneration and very subtle cognitive changes (stage 3). Individuals with MCI and memory problems, but without dementia and who are positive for one or two AD pathophysiological biomarkers are characterized as having prodromal AD. Given the differing roles of pathological Aβ and tau during AD progression anti-tau immunotherapies may be more effective in late stage disease with anti-Aβ immunotherapies most effective in prodromal AD and mild stage of AD.

Box 4.

Based on data published within the last 15 years, the major AD treatment focus has shifted to use of active or passive immunotherapies. Active vaccines targeting pathological amyloid have produced equivocal results most likely because of inadequate vaccine immunogenicity (e.g., due to generation of low titers of therapeutically potent anti-Aβ antibodies). Unfortunately the way in which AD vaccines data is currently presented makes it impossible to identify a threshold level of anti-Aβ antibodies predictive of AD vaccine efficacy and compare between each trial the true magnitude of the humoral immune responses to Aβ. In fact, if an AD vaccine targeting Aβ and tau pathology is not inducing potent concentrations of antibodies in phase I trials, there is no reason to initiate phase 2 and 3 trials with such non immunogenic antigen. Instead, the vaccine antigen should be redesigned and/or a more powerful adjuvant substituted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. I. Petrushina for help with editing and valuable comments and Dr. K. Kazarian and Mr. K. Zagorski for help in preparing the figures.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid β

- APC

Antigen presenting cell

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- ACT

Adoptive cell transfer

- ApoE4

Apolipoprotein 4

- ARIA-E

Amyloid related imaging abnormality-edema

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CDR-SB

Clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes scores

- CD40

Costimulatory receptor, type I transmembrane protein

- CD40L

Ligand of CD40, type II transmembrane protein

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ELISOT

Enzyme-linked ImmunoSpot

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- GMT

Geometric mean titer

- GAD

Glutamic acid decarboxylase

- IFNγ

Interferon, Gamma

- IL-10

Interleukin 10

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IWG

International working group

- KLH

Keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- Mab

Monoclonal antibody

- MPLA

Monophosphoryl lipid A

- MMSE

Mini–mental state examination

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NINDS

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- NIA-AA

National Institute of Aging Alzheimer’s Association

- NTB

Neuropsychological test battery

- PET FDG

Positron emission tomography Fludeoxyglucose (18F)

- TCR

Th cell receptor

- Th

T helper

- Tg

Transgenic

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TREM2

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

- VZV

Varicella Zoster Vaccine;

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005 Jan;18(1):21–25. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan AJ, Parker S. Translational mini-review series on vaccines: The Edward Jenner Museum and the history of vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007 Mar;147(3):389–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrovsky N, Aguilar JC. Vaccine adjuvants: current state and future trends. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004 Oct;82(5):488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrovsky N. Unconventional Vaccines: Progress and Challenges. J Vaccines Vaccin. 2013;4:186. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines, Blood & Biologics. Vaccines Licensed for Immunization and Distribution in the US with Supporting Documents. 2015 [cited; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm093830.htm.

- 6.Vazquez M, LaRussa PS, Gershon AA, Steinberg SP, Freudigman K, Shapiro ED. The effectiveness of the varicella vaccine in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 29;344(13):955–960. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 2;352(22):2271–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, Bialek SR. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Aug 22;63(33):729–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papaloukas O, Giannouli G, Papaevangelou V. Successes and challenges in varicella vaccine. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2014 Mar;2(2):39–55. doi: 10.1177/2051013613515621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 29;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichert JM. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies approved or in review in the European Union or United States. 2015 [cited; Available from: http://www.antibodysociety.org/news/approved_mabs.php.

- 12.Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2015. MAbs. 2015 Jan 2;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.4161/19420862.2015.988944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002 Jul 19;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayed R, Lasagna-Reeves CA. Molecular mechanisms of amyloid oligomers toxicity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S67–S78. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerpa W, Dinamarca MC, Inestrosa NC. Structure-function implications in Alzheimer’s disease: effect of Abeta oligomers at central synapses. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008 Jun;5(3):233–243. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granic A, Padmanabhan J, Norden M, Potter H. Alzheimer Abeta peptide induces chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy, including trisomy 21: requirement for tau and APP. Mol Biol Cell. 2010 Feb 15;21(4):511–520. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-10-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter H. Review and hypothesis: Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome--chromosome 21 nondisjunction may underlie both disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 1991 Jun;48(6):1192–1200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Shankar GM, Betts V, et al. Amyloid beta protein immunotherapy neutralizes Abeta oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo. Nat Med. 2005 Jun;11(6):556–561. doi: 10.1038/nm1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salomone S, Caraci F, Leggio GM, Fedotova J, Drago F. New pharmacological strategies for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: focus on disease modifying drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Apr;73(4):504–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadad BS, Britton GB, Rao KS. Targeting oligomers in neurodegenerative disorders: lessons from alpha-synuclein, tau, and amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(Suppl 2):223–232. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse [see comments] Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schenk D, Hagen M, Seubert P. Current progress in beta-amyloid immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004 Oct;16(5):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, Ugen KE, Dickey C, Hardy J, et al. A beta peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):982–985. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janus C, Chishti MA, Westaway D. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1502(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen G, Chen KS, Knox J, Inglis J, Bernard A, Martin SJ, Justice A, McConlogue L, Games D, Freedman SB, Morris RGM. A learning deficit related to age and beta-amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:975–979. doi: 10.1038/35050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodart JC, Bales KR, Gannon KS, Greene SJ, DeMattos RB, Mathis C, et al. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Abeta burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat Neurosci. 2002 May;5(5):452–457. doi: 10.1038/nn842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilcock DM, Rojiani A, Rosenthal A, Subbarao S, Freeman MJ, Gordon MN, et al. Passive immunotherapy against Abeta in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2004 Dec 8;1(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bard F, Barbour R, Cannon C, Carretto R, Fox M, Games D, et al. Epitope and isotype specificities of antibodies to beta -amyloid peptide for protection against Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(4):2023–2028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436286100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, Christie RH, Carter C, Games D, Seubert P, et al. Imaging of amyloid-beta deposits in brains of living mice permits direct observation of clearance of plaques with immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2001 Mar;7(3):369–372. doi: 10.1038/85525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcock DM, Munireddy SK, Rosenthal A, Ugen KE, Gordon MN, Morgan D. Microglial activation facilitates Abeta plaque removal following intracranial anti-Abeta antibody administration. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon B, Koppel R, Frankel D, Hanan-Aharon E. Disaggregation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid by site-directed mAb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(8):4109–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frenkel D, Balass M, Solomon B. N-terminal EFRH sequence of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide represents the epitope of its anti-aggregating antibodies. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1998;88(1–2):85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frenkel D, Balass M, Katchalski-Katzir E, Solomon B. High affinity binding of monoclonal antibodies to the sequential epitope EFRH of beta-amyloid peptide is essential for modulation of fibrillar aggregation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1999;95(1–2):136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, McLellan ME, Games D, Seubert P, Schenk D, et al. Non-Fc-mediated mechanisms are involved in clearance of amyloid-beta in vivo by immunotherapy. J Neurosci. 2002;22(18):7873–7878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07873.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Brain to plasma amyloid-beta efflux: a measure of brain amyloid burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2002 Mar 22;295(5563):2264–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.1067568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Parsadanian M, O’Dell MA, Foss EM, Paul SM, et al. Plaque-associated disruption of CSF and plasma amyloid-b (Ab) equlibrium in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochemistry. 2002;81:229–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eli Lilly and Company Announcement. Eli Lilly and Company Announces Top-Line Results on Solanezumab Phase 3 Clinical Trials in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. 2012 Available at http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=702211.

- 42.Lobello K, Ryan JM, Liu E, Rippon G, Black R. Targeting Beta amyloid: a clinical review of immunotherapeutic approaches in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:628070. doi: 10.1155/2012/628070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lannfelt L, Relkin NR, Siemers ER. Amyloid-β-directed immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med. 2014 Mar;275(3):284–295. doi: 10.1111/joim.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delrieu J, Ousset PJ, Caillaud C, Vellas B. ‘Clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease’: immunotherapy approaches. J Neurochem. 2012 Jan;120(Suppl 1):186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemere CA, Masliah E. Can Alzheimer disease be prevented by amyloid-beta immunotherapy? Nat Rev Neurol. 2010 Feb;6(2):108–119. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghochikyan A, Agadjanyan MG. CAD-106, a beta-amyloid-based immunotherapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease. Thompson Reuter. 2012 https://partnering.thomson-pharma.com.

- 47.Agadjanyan M, Cribbs D, editors. G. Active and Passive Aβ-Immunotherapy: Positive and Negative Outcomes from Pre-Clinical and Clinical Trials and Future Directions. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8(1 & 2) doi: 10.2174/187152709787601849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisniewski T. AD vaccines: conclusions and future directions. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Apr;8(2):160–166. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wisniewski T, Goni F. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 Apr 15;88(4):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alzforum. Biogen Antibody Buoyed by Phase 1 Data and Hungry Investors. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neurimmune. Aducanumab (BIIB037) reduced brain amylooid plaque levels and slowed cognitive decline in patients with prodromal or mild Alzheimer’s disease in phase 1B study. Biogen Idec presents positive interim results from phase 1B study at 2015 AD/PD Conference. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JM, Laurent B, Puel M, Kirby LC, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61(1):46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073623.84147.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrer I, Rovira MB, Guerra MLS, Rey MJ, Costa-Jussa F. Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(1):11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masliah E, Hansen L, Adame A, Crews L, Bard F, Lee C, et al. Abeta vaccination effects on plaque pathology in the absence of encephalitis in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005 Jan 11;64(1):129–131. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148590.39911.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicoll JA, Barton E, Boche D, Neal JW, Ferrer I, Thompson P, et al. Abeta species removal after abeta42 immunization. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006 Nov;65(11):1040–1048. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240466.10758.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patton RL, Kalback WM, Esh CL, Kokjohn TA, Van Vickle GD, Luehrs DC, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide remnants in AN-1792-immunized Alzheimer’s disease patients: a biochemical analysis. Am J Pathol. 2006 Sep;169(3):1048–10463. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, Jenkins L, Griffith SG, Fox NC, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005 May 10;64(9):1553–1562. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grabenstein J. Vaccine Excipient & Media Summary. ImmunoFacts: Vaccines and Immunologic Drugs – 2013 1st ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1 edition (November 15, 2012) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mignot EJ. History of narcolepsy at Stanford University. Immunol Res. 2014 May;58(2–3):315–339. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmed SS, Schur PH, MacDonald NE, Steinman L. Narcolepsy, 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic influenza, and pandemic influenza vaccinations: what is known and unknown about the neurological disorder, the role for autoimmunity, and vaccine adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2014 May;50:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsai TF, Crucitti A, Nacci P, Nicolay U, Della Cioppa G, Ferguson J, et al. Explorations of clinical trials and pharmacovigilance databases of MF59(R)-adjuvanted influenza vaccines for associated cases of narcolepsy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011 Sep;43(9):702–706. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.580777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petrovsky N. Comparative safety of vaccine adjuvants: a summary of current evidence and future needs. Drug Safety in press. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0350-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bayer AJ, Bullock R, Jones RW, Wilkinson D, Paterson KR, Jenkins L, et al. Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of synthetic Abeta42 (AN1792) in patients with AD. Neurology. 2005 Jan 11;64(1):94–101. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148604.77591.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fox NC, Black RS, Gilman S, Rossor MN, Griffith SG, Jenkins L, et al. Effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005 May 10;64(9):1563–1572. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hock C, Konietzko U, Papassotiropoulos A, Wollmer A, Streffer J, Von Rotz RC, et al. Generation of antibodies specific for beta-amyloid by vaccination of patients with Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2002 Oct 15;8(11):1270–1275. doi: 10.1038/nm783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunization in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008 Jul 19;372(9634):216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hock C, Konietzko U, Streffer JR, Tracy J, Signorell A, Muller-Tillmanns B, et al. Antibodies against beta-Amyloid Slow Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron. 2003 May 22;38(4):547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Parijs L, Abbas AK. Homeostasis and self-tolerance in the immune system: turning lymphocytes off. Science. 1998 Apr 10;280(5361):243–248. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiskopf D, Weinberger B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. The aging of the immune system. Transpl Int. 2009 Nov;22(11):1041–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tarawneh R, Holtzman DM. Critical issues for successful immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s disease: development of biomarkers and methods for early detection and intervention. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Apr;8(2):144–159. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kokjohn TA, Roher AE. Antibody responses, amyloid-beta peptide remnants and clinical effects of AN-1792 immunization in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Apr;8(2):88–97. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang CY, Finstad CL, Walfield AM, Sia C, Sokoll KK, Chang TY, et al. Site-specific UBITh amyloid-beta vaccine for immunotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Vaccine. 2007 Apr 20;25(16):3041–3052. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winblad BG, Minthon L, Floesser A, Imbert G, Dumortier T, He Y, et al. Results of the first-in-man study with the active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 in Alzheimer’s patients. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Association. 2009;5(4, suppl.):113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petrushina I, Ghochikyan A, Mktrichyan M, Mamikonyan G, Movsesyan N, Davtyan H, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Peptide Epitope Vaccine Reduces Insoluble But Not Soluble/Oligomeric A{beta} Species in Amyloid Precursor Protein Transgenic Mice. J Neurosci. 2007 Nov 14;27(46):12721–12731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3201-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Cribbs DH, et al. The MultiTEP platform-based Alzheimer’s disease epitope vaccine activates a broad repertoire of T helper cells in nonhuman primates. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 May;10(3):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ryan JM, Grundman M. Anti-amyloid-beta immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s disease: ACC-001 clinical trials are ongoing. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17(2):243. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Janeway CA, Jr, Travers P, Walport MJ. Galand Science. 5th edition ed. 2001. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lemere CA. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: hoops and hurdles. Mol Neurodegener. 2013 Oct 22;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Imbimbo BP, Tortelli R, Santamato A, Logroscino G. Amyloid-based immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease in the time of prevention trials: the way forward. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014 Mar;10(3):405–419. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.883921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winblad B, Graf A, Riviere ME, Andreasen N, Ryan JM. Active immunotherapy options for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/alzrt237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reed SG, Orr MT, Fox CB. Key roles of adjuvants in modern vaccines. Nat Med. 2013 Dec;19(12):1597–1608. doi: 10.1038/nm.3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Petrovsky N. Freeing vaccine adjuvants from dangerous immunological dogma. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008 Feb;7(1):7–10. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Muhs A, Hickman DT, Pihlgren M, Chuard N, Giriens V, Meerschman C, et al. Liposomal vaccines with conformation-specific amyloid peptide antigens define immune response and efficacy in APP transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jun 5;104(23):9810–9815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703137104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Evans CF, Davtyan H, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Hannaman D, et al. Epitope-based DNA vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease: Translational study in macaques. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 May;10(3):284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.AlzForum. In Surprise, Placebo, not Aβ Vaccine, Said to Slow Alzheimer’s. 2014 [cited; Available from: http://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/surprise-placebo-not-av-vaccine-said-slow-alzheimers.

- 87.AlzForum. Vanutide cridificar. 2013 [cited; Available from: http://www.alzforum.org/therapeutics/vanutide-cridificar.

- 88.V950-001 AM7. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00464334. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Winblad B, Andreasen N, Minthon L, Floesser A, Imbert G, Dumortier T, et al. Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Jul;11(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schneeberger A, Mandler M, Mattner F, Schmidt W. AFFITOME(R) technology in neurodegenerative diseases: the doubling advantage. Hum Vaccin. 2010 Nov;6(11):948–952. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.11.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arai H, Suzuki H, Yoshiyama T. Vanutide Cridificar and the QS-21 Adjuvant in Japanese Subjects with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’ s Disease: Results from Two Phase 2 Studies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(3):242–254. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150302154121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 23;370(4):322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 23;370(4):311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chertkow H, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Massoud F. Definitions of dementia and predementia states in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment: consensus from the Canadian conference on diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013. Jul 8;5(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/alzrt198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Ayutyanont N, Lopera F, Quiroz YT, et al. Ushering in the study and treatment of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013 Jul;9(7):371–381. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoffmann-La Roche. A Study of Gantenerumab in Patients With Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. Identifier: NCT01224106. [Google Scholar]

- 97.DIAN study. Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trial: An Opportunity to Prevent Dementia. A Study of Potential Disease Modifying Treatments in Individuals at Risk for or With a Type of Early Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Caused by a Genetic Mutation. Identifier: NCT01760005. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014 Mar 19;6(228) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941. 228fs13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.ADCS/A4. NCT02008357: Clinical Trial of Solanezumab for Older Individuals Who May be at Risk for Memory Loss (A4) [Google Scholar]

- 100.Medina M, Avila J. New perspectives on the role of tau in Alzheimer’s diseaseImplications for therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 Apr 15;88(4):540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lemere CA, Maier M, Jiang L, Peng Y, Seabrook TJ. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer disease: lessons from mice, monkeys, and humans. Rejuvenation Res. 2006 Spring;9(1):77–84. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Maier M, Seabrook TJ, Lazo ND, Jiang L, Das P, Janus C, et al. Short amyloid-beta (Abeta) immunogens reduce cerebral Abeta load and learning deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model in the absence of an Abeta-specific cellular immune response. J Neurosci. 2006 May 3;26(18):4717–4728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0381-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nojima J, Maeda A, Aoki S, Suo S, Yanagihara D, Watanabe Y, et al. Effect of rice-expressed amyloid beta in the Tg2576 Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model. Vaccine. 2011 Aug 26;29(37):6252–6258. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Saade F, Gorski SA, Petrovsky N. Pushing the frontiers of T-cell vaccines: accurate measurement of human T-cell responses. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012 Dec;11(12):1459–1470. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Derhovanessian E, Solana R, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Immunity, ageing and cancer. Immun Ageing. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Understanding immunosenescence to improve responses to vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2013 May;14(5):428–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pride M, Seubert P, Grundman M, Hagen M, Eldridge J, Black RS. Progress in the active immunotherapeutic approach to Alzheimer’s disease: clinical investigations into AN1792-associated meningoencephalitis. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5(3–4):194–196. doi: 10.1159/000113700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Farlow MR, Andreasen N, Riviere ME, Vostiar I, Vitaliti A, Sovago J, et al. Long-term treatment with active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Winblad B, Farlow M, Blennow K, Vostiar I, Imbert G, Tomovic A, et al. Aβ-specific antibodies induced by active immunotherapy CAD106 engage Aβ in plasma in AD patients. ALZHEIMER DEMENTIA. 2011;7(4):P2-083. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ghochikyan A, Davtyan H, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Movsesyan N, Davtyan A, et al. Refinement of a DNA based Alzheimer’s disease epitope vaccine in rabbits. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Feb 11;9(5):1002–1010. doi: 10.4161/hv.23875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300(5618):486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]