Abstract

Objective

Depression and chronic pain are common in persons chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), although little is known about the rate of co-occurrence or mechanisms by which they are associated. We evaluated whether pain-related anxiety mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and pain-related physical functioning in patients with HCV.

Methods

Patients with HCV (n=175) completed self-report measures assessing demographic characteristics, pain-related function, and mental health. Path analyses examined direct effects of cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms of depression on pain interference and indirect effects of these relationships via four subscales of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20.

Results

Cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms of depression were positively and significantly related to pain interference. Pain-related anxiety mediated the relationship between both cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms of depression, and this mediation was predominantly accounted for by the escape-avoidance component of pain-related anxiety.

Conclusions

Findings indicate a potential mediating role of pain-related anxiety, particularly escape-avoidance anxiety, on the relationship between depression and pain interference in patients with HCV. These findings suggest that escape-avoidance anxiety may be a particularly germane target for treatment in patients with HCV and chronic pain, particularly when depression, with characteristic features of withdrawal and inhibition, is a comorbid condition.

Keywords: Pain-related anxiety, Chronic pain, Depression, Hepatitis C virus, Comorbidity

Introduction

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common blood-borne infection in the United States, affecting nearly 2% of the general population [1]. Prevalence rates of HCV are elevated in specific subpopulations, including males, African Americans, lower income and education groups, and those with co-morbid psychiatric conditions or a history of injection drug use [1,2]. HCV infection is a leading cause of liver disease, cirrhosis, and the primary indication for liver transplantation [3]. Among veterans seeking care at Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, the prevalence rate is estimated to be 5.4% [4].

Pain is one of the most pervasive symptoms reported in the primary care setting [5,6]. Chronic pain impacts over 35% of adults in the United States [7] and is associated with decreased quality of life [8], increased medical utilization [9], and increased medical and psychiatric comorbidity [10]. Patients with HCV have disproportionately high rates of chronic pain and pain-related diagnoses [11–13] and high rates of comorbid substance use [2]. A history of substance use disorder has been linked with chronic pain [14]. Moreover, patients with HCV and chronic pain utilize more medical services than patients with HCV alone, including primary care visits, overall hospital services, and pain specialty services [15]. Research indicates that psychological factors are significantly associated with chronic pain in patients with HCV; notably, pain catastrophizing, perceived self-efficacy for managing pain, and depressive symptoms have been shown to be predictive of pain severity and declines in physical function [16,17].

Among individuals with chronic pain, depression is associated with a greater number of pain sites, higher pain intensity, longer duration of pain, and lower levels of treatment response [18]. Approximately 20% to 40% of patients with HCV experience clinically significant symptoms of depression [19–24]. Depressive symptoms are important contributors to fatigue, functional disability, and decreased health-related quality of life in patients with HCV [20,25,26]. Chronic inflammation and consequent higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with HCV itself may be a contributor to higher rates of depressive symptoms and pain [27,28].

Although depressive symptoms and chronic pain are both common among patients with HCV, the mechanisms by which depression is associated with pain and functional outcomes remain unclear and have not been studied in this population. Pain-related anxiety significantly contributes to self-reported suffering and disability [29–32]. Pain-specific anxiety symptoms, or fear responses to pain or pain-related events, are grouped into symptoms of cognitive anxiety, escape-avoidance, fearful thinking, and physiological anxiety. The repeating and self-perpetuating cycle of pain, avoidance, behavioral deactivation and physical deconditioning may compound one’s experience of pain [33]. These responses may be implicated further when coupled with depression, as prior research indicates that patients with comorbid depression and anxiety experience greater pain severity and pain-related disability, and poorer health-related quality of life, compared with patients with depression alone [34]. Thus, pain-related anxiety may play an important mediating role in the relationship between depressive symptoms and pain. This relationship may be particularly important in patients with HCV, given the high rate of these comorbid conditions.

While depressive symptoms and chronic pain are common in persons with HCV infection, the rate of co-occurrence of clinically significant depressive symptoms and chronic pain has not been identified, and the mechanisms by which depression is associated with pain interference are not well understood. The current study was designed to explore the rate of comorbid chronic pain and depression in persons with HCV, as well as the extent to which pain-related anxiety may mediate the relationship between depressive symptoms and pain interference in patients with HCV.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study sample was composed of patients enrolled at a Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in the Pacific Northwest. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods including advertisements posted throughout the medical center, letters mailed to patients with HCV who had pending primary care appointments, announcements made in mental health classes conducted at the VA, and referrals of patients currently being treated in the hospital’s Hepatology clinic. All participants provided their written consent prior to enrollment; participation involved a one-time clinical interview and completion of a set of self-report questionnaires.

All participants met the criteria for a diagnosis of HCV, as confirmed by detectable HCV RNA level on polymerase chain reaction test. Other eligibility criteria included being fluent in English and between the ages of 18 to 70 years old. Participants were excluded if they were over the age of 70, had current suicidal ideation, untreated serious psychiatric illness (such as bipolar disorder or psychotic-spectrum disorder), any pending litigation or disability compensation for pain, a history of advanced liver disease, or any current or past treatment with antiviral therapy or chemotherapy.

Advanced liver disease was defined as having a current or past diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, Stage 4 liver disease on biopsy, cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, or prior liver transplantation. Using the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI), which is an estimate of liver disease severity, participants were also considered to have advanced liver disease if the APRI score was greater than 1.5 [35]. Individuals with advanced liver disease and those who had received antiviral therapy or chemotherapy were excluded as these conditions and treatments are associated with significant physical symptoms, which could confound the assessment of factors associated with chronic pain.

Measures

Demographic characteristics were collected by self-report. These included age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and yearly income. Information regarding participants’ pain diagnoses, prescription opioid status, and antidepressant medication use were obtained by self-report, and confirmed by electronic medical record.

Pain interference was assessed with the well-validated Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) Interference scale that was originally developed with a VA sample [36]. The MPI Interference Scale comprises 11 questions that rate the extent to which pain interfered with various domains of one’s life, including daily activities, work, recreation, and social relationships. Scores on individual items are averaged, and summary scores range from 0 to 6. The internal consistency of the MPI Interference scale for the present study was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91).

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) measured depressive symptoms [37]. The BDI-II outlines the following cutoff scores for symptom severity: 0–13=minimal, 14–19=mild, 20–28=moderate and 29–63=severe. A conservative cut-off score of ≥17 indicates clinically significant depressive symptoms [37]. Prior research with veterans with HCV suggests that depressive symptoms, as measured by the BDI-II, cluster in two domains for patients with HCV: cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms of depression [38]. Cognitive-affective symptoms include sadness, pessimism, past failure beliefs, guilty feelings, punishment feelings, self-dislike, self-criticality, suicidal thoughts, crying, agitation, and worthlessness. Somatic symptoms include loss of energy, sleep changes, irritability, appetite changes, concentration difficulty, tiredness/fatigue, and loss of libido. Summary scores are derived by summing scores of the individual items comprising each subscale. Cronbach’s alpha for cognitive-affective and somatic depressive symptom subscales were in the good to excellent range for the current study (0.90 for the cognitive-affective symptom subscale; 0.82 for the somatic symptom subscale).

Pain-related anxiety was assessed using the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20 (PASS-20) [39], a 20-item self-report measure of fear and anxiety responses specific to pain. This measure consists of four subscales measuring cognitive anxiety, escape-avoidance, fearful thinking, and physiological anxiety. All items are rated on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The PASS-20 demonstrates strong internal consistency and reliability, as well as good predictive and construct validity [39]. Internal consistency coefficients for the four PASS-20 subscales in the current study were: cognitive anxiety (0.91), escape and avoidance (0.78), fearful thinking (0.84), and physiological anxiety (0.81).

Substance use disorders (SUDs) were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) [40], a semi-structured clinical interview designed to assess criteria for diagnosis. A substance use disorder was considered current if the participant met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence to the substance within the past month. SCID interviews were conducted by masters-level research clinicians; all interviewers received extensive training by a licensed psychologist. Regular supervision of SCID interviews was implemented to reduce the likelihood of coder drift.

Statistical Analyses

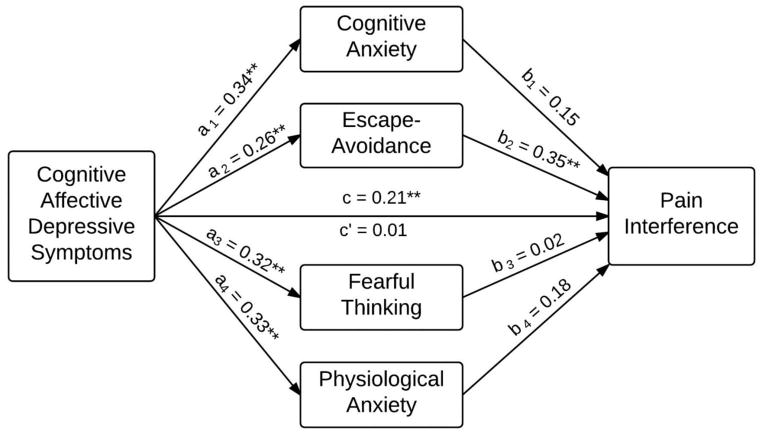

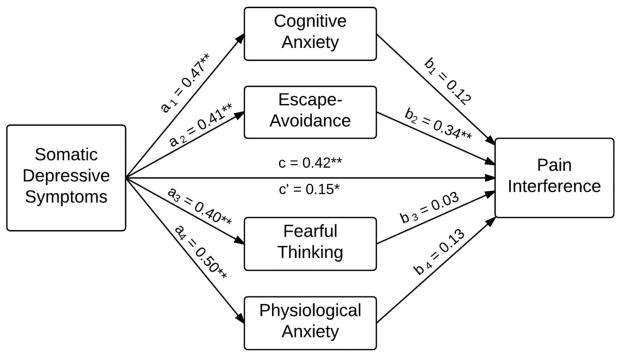

Descriptive statistics characterized the sample across demographic and clinical variables. Pain interference, as opposed to pain severity, was selected a priori as the primary variable of interest as interference is a better predictor of functioning than the severity of pain levels. Pearson product moment correlations examined bivariate relationships of depressive symptoms (i.e., cognitive-affective and somatic BDI-II subscales) with pain-related anxiety and pain interference, as measured by the four PASS-20 anxiety subscales and MPI Interference scale, respectively. We employed path analysis and multiple mediation to assess both the direct effect of depressive symptoms on pain interference and the indirect effect of depressive symptoms on pain interference via pain anxiety. Multiple mediation allows for the simultaneous testing of two or more candidate mediators [41]. Consistent with the mediation literature, we use the following labels in figures depicting mediation models: a denotes the effect of the independent variable on the mediator, b denotes the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable, c denotes the unmediated effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, and c′ denotes the mediated effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (i.e., the direct effect). All mediation models account for intercorrelations between candidate mediators; however, intercorrelations are not depicted in mediation figures below.

Separate multiple mediation models were conducted for cognitive-affective depressive symptoms and somatic-depressive symptoms. We assessed the combined mediating effect of all four PASS-20 subscales, as well as the individual mediating effect of each PASS-20 subscale. The product-of-coefficients approach [42] evaluated the significance of indirect effects. In this analytic technique, the effect of the independent variable on the mediator (i.e., the a path coefficient) is multiplied by the corresponding effect of the mediator on the dependent variable (i.e., the b path coefficient). The ab product is divided by the standard error of the estimate, and the quotient is compared to a critical value using a z-test. As recommended by Preacher and Hayes [43], we used bootstrapping procedures to corroborate findings from the products-of-coefficients analyses. All statistical tests used an alpha-level of 0.05 and two-tailed tests of significance.

Results

The mean age of participants (n=175) was 56.2 years (SD = 5.8 years). The sample was composed predominantly of male (93%) and Caucasian, non-Hispanic (70%) participants. Ethnic minority participants included 14% African-American, 5% Latino, 6% American Indian, and 5% mixed/other ethnicity. Twenty-three percent of participants were married, 49% were separated or divorced, 5% were widowed, and 23% were single, never married. Seventy-five percent had completed high school or its equivalent, and approximately 61% reported annual income less than $15,000. Eighteen percent of participants met criteria for a current alcohol or other substance use disorder.

Forty-three percent (n = 76) of participants endorsed moderate to severe depressive symptoms based on BDI-II scores ≥ 17, while 48% (n=84) were currently prescribed antidepressant medication. Fifty-eight percent (n=102) reported ever having been diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and currently experiencing pain. Twenty-six percent (n = 45) of participants met criteria for both chronic pain and moderate to severe depression. Among participants with pain, the most common general pain-related diagnoses were neck or joint pain (87%; n = 89), low back pain (74%; n = 75), and arthritis (71%; n = 72). Fifty-eight percent (n = 59) of participants with pain had two or three pain-related diagnoses in their medical record and 26% (n = 27) had four or more pain diagnoses. Among participants with chronic pain, the average duration of pain was 13.0 (SD = 12.0) years. One-third of the sample (57 of 175 participants) self-reported use of prescription opioid medications in the past month.

Mediation Analyses

Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for variables contained in the mediation analysis, as well as bivariate correlations between independent variables (depressive symptoms), candidate pain-anxiety mediators, and pain interference. Figure 1 illustrates that cognitive-affective depressive symptoms had a significant effect on pain interference (c = 0.21, p < 0.01). This effect was jointly mediated by pain-anxiety symptoms (total indirect effect = 0.20, p < 0.01). Only escape-avoidance pain anxiety produced significant indirect effects (specific indirect effect = 0.09, p < 0.01). After accounting for mediation, the direct effect of cognitive-affective depressive symptoms on pain-related interference was no longer significant and near zero (c′ = 0.01, p = 0.91), indicating full mediation. Table 2 provides model statistics for indirect effects using the product of coefficients approach and bootstrapping procedures, which corroborated the products of coefficients results. Specifically, the 95% confidence intervals for total indirect effects and specific indirect effects via escape-avoidance pain-anxiety did not contain zero, whereas 95% confidence intervals for all other specific indirect effects contained zero.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for, and bivariate correlations between, depressive symptoms, pain anxiety, and pain interference.

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||||||||

| 1. Cognitive-affective depressive symptoms | 7.1 (6.3) | — | ||||||

| 2. Somatic depressive symptoms | 6.7 (4.2) | 0.70** | — | |||||

| Mediators | ||||||||

| 3. Pain anxiety cognitions | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.34** | 0.47** | — | ||||

| 4. Pain anxiety escape | 2.5 (1.2) | 0.26** | 0.41** | 0.72** | — | |||

| 5. Pain anxiety fear | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.32** | 0.40** | 0.72** | 0.61** | — | ||

| 6. Pain anxiety physical | 1.7 (1.2) | 0.33** | 0.50** | 0.78** | 0.69** | 0.79** | — | |

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

| 7. Pain interference | 3.3 (1.8) | 0.21** | 0.42** | 0.56** | 0.59** | 0.48** | 0.55** | — |

Note.

p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Mediation model for cognitive-affective depressive symptoms and pain interference. ** p < 0.01

Table 2.

Indirect effects of cognitive-affective and somatic depressive symptoms on pain interference via pain anxiety.

| Effect | Point Estimate | Product of Coefficients | Bootstrap 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | Lower 2.5% | Upper 2.5% | ||

| Cognitive-affective depressive symptoms | ||||

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.20** | 4.18 | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| Pain Anxiety Cognitions | 0.05 | 1.20 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Pain Anxiety Escape/Avoidance | 0.09** | 2.79 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Pain Anxiety Fear | 0.01 | 0.15 | −0.07 | 0.08 |

| Pain Anxiety Physical | 0.06 | 1.26 | −0.03 | 0.15 |

| Somatic Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.27** | 5.64 | 0.18 | 0.37 |

| Pain Anxiety Cognitions | 0.06 | 1.02 | −0.05 | 0.17 |

| Pain Anxiety Escape/Avoidance | 0.14** | 3.60 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Pain Anxiety Fear | 0.01 | 0.24 | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| Pain Anxiety Physical | 0.06 | 0.98 | −0.07 | 0.20 |

Note. In the product of coefficients approach, the indirect effect point estimate is divided by its standard error, and the quotient is compared to a critical value using a z-test. Z values greater than 1.96 correspond to p < 0.05, while z values greater than 2.58 correspond to p < 0.01.

p < 0.01.

Figure 2 depicts the mediation model for the independent variable somatic depressive symptoms. Somatic depressive symptoms had a significant effect on pain interference (c = 0.42, p < 0.01). The effect of somatic-depressive symptoms on pain interference was jointly mediated by pain-related anxiety symptoms (total indirect effect = 0.27, p < 0.01), and this joint effect was accounted for primarily by the specific indirect effect of escape-avoidance pain anxiety (specific indirect effect = 0.14, p < 0.01). After accounting for mediation, the direct effect of somatic-depressive symptoms on pain-related interference remained significant (c′ = 0.15, p = 0.05), indicating pain-related anxiety partially mediated the effect of somatic depressive symptoms on pain interference. The analyses based on the bootstrapping procedures confirmed these findings (see Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mediation model for somatic depressive symptoms and pain interference. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Discussion

The present study focuses on the relationship between depressive symptoms and pain-related interference in persons with HCV. Prior research demonstrates high comorbidity of major depressive disorder among patients with chronic pain and vice versa [18]. In this sample of veterans with HCV, 43% had clinically-significant symptoms of depression and 58% had chronic pain, rates which are consistent with prior research [11,13,17,21,24]. Twenty-six percent of patients had both depressive symptoms and chronic pain, a rate of comorbidity that is substantially higher than observed in the general population [44]. These results are important, as common characteristics of depression including low self-efficacy, negative thoughts, and learned helplessness, may negatively impact the way in which individuals cope with their pain. Thus, pain in this sample of patients with comorbid depression may be particularly recalcitrant to treat and may therefore require more specific treatment needs.

This study also examined potential mediators by which depression is associated with chronic pain in patients with HCV. We found that pain-related anxiety, particularly of the escape-avoidance type, may mediate the relationship between cognitive-affective symptoms of depression and pain-related interference. Escape-avoidance pain-anxiety was also a partial mediator of the relationship between somatic depressive symptoms and pain interference. Escape-avoidance anxiety is characterized by a drive to act in a way that will reduce a negative or uncomfortable state. In the case of pain-related anxiety, fearful appraisal of re-injury may lead to anticipatory fear and consequently behavioral inhibition or activity restriction. Many patients with chronic pain limit movement out of fear that activity will lead to injury and increased pain [30,45,46]. However, inactivity will lead to muscle atrophy, reduced mobility, and increased pain interference, and disability. Findings from this study suggest that escape-avoidance anxiety may be a particularly germane target for treatment in patients with HCV and chronic pain, particularly when depression, with characteristic features of withdrawal and inhibition, is a comorbid condition. If provider attention were directed towards addressing pain-related anxiety, the painful condition may be less likely to interfere with daily activities.

Several evidence-based treatments may be particularly helpful at reducing pain-related anxiety. Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is effective in reducing anxiety sensitivity and decreasing anxiety related to pain sensations [47–50]. Through psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and interoceptive exposure, participants are taught strategies for reducing tendencies to misinterpret about the consequences of arousal-related sensations. CBT further addresses pain-related appraisals of physiological symptoms, while teaching strategies to cope with pain, such as relaxation training. Other potentially-effective therapies that have garnered empirical support for targeting pain-related anxiety include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) [49,51–53].

There are several limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of study results. The cross-sectional design of this study prevents causal inference. Prospective research is needed to confirm these findings. Further, given the characteristics of our sample, generalizability of our results is limited. Specifically, all participants were U.S. military veterans with HCV who were treatment-naïve, and were predominantly Caucasian males. It remains unclear whether these findings would be found in patients without HCV, or among patients who had received antiviral therapy for HCV. Therefore, replication of these results in other samples and settings would increase confidence of the validity of study findings. Finally, we examined a single mechanism—pain-related anxiety—by which depression may be associated with pain interference. Although pain-related anxiety may mediate the relationship between cognitive-affective depressive symptoms and pain-related interference, additional mediating constructs may help explain the mechanism by which somatic-depressive symptoms are associated with interference.

In summary, we found that clinically significant comorbid depressive symptoms and chronic pain affect 26% of patients with HCV infection, and pain-related anxiety may mediate the relationship between depression and pain-related interference. This illustrates the importance of focusing on treatment interventions that target pain-related anxiety in order to improve the pain functioning among patients with HCV reporting depressive symptoms. Altogether, these findings enhance our understanding of how depression and pain-related anxiety may be associated with disability in patients with HCV who have chronic pain and suggest an important target for treatment in this population.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by grants 023467 and 034083 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. The work was also supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Portland Health Care System. During the past 12 months, Dr. Turk has received consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Mallincrodt, Nektar, Orexo, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Pfizer, Philips Respironics, and Xydinia, and receives research support from the National Institutes of Health and U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

Footnotes

No other author reports having any potential conflict of interest with this study.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:172–174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominitz JA, Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Heagerty PJ, Maynard C, Sporleder JL. Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States Veterans medical centers. Hepatol. 2005;41:88–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2474–2480. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410210102011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhaak PFM, Schellevis FG, Nuijen J, Volkers AC. Patients with a psychiatric disorder in general practice: determinants of general practitioners’ psychological diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain and frequent use of health care. Pain. 2004;111:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S, Posada-Villa J, Kovess V, Angermeyer MC, Levinson D, de Girolamo G, Nakane H, Mneimneh Z, Lara C, de Graaf R, Scott KM, Gureje O, Stein DJ, Haro JM, Bromet EJ, Kessler RC, Alonso J, Von Korff M. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: Results from the world mental health surveys. Pain. 2007;129:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silberbogen AK, Janke EA, Hebenstreit C. A closer look at pain and hepatitis C: Preliminary data from a veteran population. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:231–244. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.05.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassilopoulos D, Calabrese LH. Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis C infection. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003;5:200–204. doi: 10.1007/s11926-003-0067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead AJ, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Ruimy S, Bussell C, Hauser P. Pain, substance use disorders and opioid analgesic prescription patterns in veterans with hepatitis C. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morasco BJ, Gritzner S, Lewis L, Oldham R, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain. 2011;152:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovejoy TI, Dobscha SK, Cavanagh R, Turk DC, Morasco BJ. Chronic pain treatment and health service utilization of veterans with hepatitis C virus infection. Pain Med. 2012;13:1407–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morasco BJ, Huckans M, Loftis JM, Woodhouse J, Seelye A, Turk DC, Hauser P. Predictors of pain intensity and pain functioning in patients with the hepatitis C virus. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morasco BJ, Lovejoy TI, Turk DC, Crain A, Hauser P, Dobscha SK. Biopsychosocial factors associated with pain in veterans with the hepatitis C virus. J Behav Med. 2014;37:902–911. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9549-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2433–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieperink E, Willenbring M, Ho SB. Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with hepatitis C and interferon alpha: A review. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:867–876. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwight MM, Kowdley KV, Russo JE, Ciechanowski PS, Larson AM, Katon WJ. Depression, fatigue, and functional disability in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:311–317. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fireman M, Indest D, Blackwell AD, Whitehead AJ, Hauser P. Addressing tri-morbidity (hepatitis C, psychiatric disorders, and substance use): The importance of routine mental health screening as a component of comanagement model of care. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:286–291. doi: 10.1086/427442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golden J, Conroy RM, O’Dwyer AM, Golden D, Hardouin J. Illness related stigma, mood and adjustment to illness in persons with hepatitis C. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3188–3198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golden J, O’Dwyer AM, Conroy RM. Depression and anxiety in patients with hepatitis C: Prevalence, detection rates and risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelligan J, Loftis JM, Matthews AM, Zucker BL, Linke AM, Hauser P. Depression comorbidity and antidepressant use in veterans with chronic hepatitis C: Results from a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:810–816. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dan AA, Martin LM, Crone C. Depression, anemia and health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowan PJ, Al-Jurdi R, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, Kunik ME, Satrom SL, El-Serag HB. Physical and psychosocial contributors to quality of life in veterans with hepatitis C not on antiviral therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:731–736. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000173860.08478.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loftis JM, Huckans M, Morasco BJ. Neuroimmune mechanisms of cytokine-induced depression: Current theories and novel treatment strategies. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loftis JM, Huckans M, Ruimy S, Hinrichs DJ, Hauser P. Depressive symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C are correlated with elevated plasma levels of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α. Neurosci Lett. 2008;430:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCracken LM, Zayfert C, Gross RT. The Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale: Development and validation of a scale to measure fear of pain. Pain. 1992;50:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90113-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vlaeyen JWS, Kole-Snijders AMJ, Boeren RGB, Van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363–372. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlaeyen JWS, Kole-Snijders AMJ, Rotteveel A, Ruesink R, Heuts PHTG. The role of fear of movement/(re)injury in pain disability. J Occup Rehabil. 1995;5:235–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02109988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JWS, Heuts PHTG, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling that pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80:329–339. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCracken LM, Gross RT. The Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) and the assessment of emotional responses to pain. In: VandeCreek L, Knapp S, Jackson TL, editors. Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook. Vol. 14. Sarasota: Professional Resources Press; 1995. pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bair MJ, Wu J, Damush TM, Sutherland JM, Kroenke K. Association of depression and anxiety alone and in combination with chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:890–897. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318185c510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson AL, Morasco BJ, Fuller BE, Indest DW, Loftis JM, Hauser P. Screening for depression in patients with hepatitis C using the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Do somatic symptoms compromise validity? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCracken LM, Dhingra L. A short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS--20): Preliminary development and validity. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7:45–50. doi: 10.1155/2002/517163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition. (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishop YMM, Fienberg SE, Holland PW. Discrete multivariate analysis: Theory and practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: A World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose M, Klenerman L, Atchinson L, Slade PD. An application of the fear-avoidance model to three chronic pain problems. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90047-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main C. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watt MC, Stewart SH, Lefaivre MJ, Uman LS. A brief cognitive-behavioral approach to reducing anxiety sensitivity decreases pain-related anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35:248–256. doi: 10.1080/16506070600898553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smits JA, Berry AC, Tart CD, Powers MB. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions for reducing anxiety sensitivity: A meta-analytic review. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailey KM, Carleton RN, Vlaeyen JW, Asmundson GJ. Treatments addressing pain-related fear and anxiety in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A preliminary review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2010;39:46–63. doi: 10.1080/16506070902980711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCracken LM, Gross RT, Eccleston C. Multimethod assessment of treatment process in chronic low back pain: comparison of reported pain-related anxiety with directly measured physical capacity. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:585–594. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tekur P, Nagarathna R, Chametcha S, Hankey A, Nagendra HR. A comprehensive yoga program improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: An RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wetherell JL, Afari N, Rutledge T, Sorrell JT, Stoddard JA, Petkus AJ, Solomon BC, Lehman DH, Liu L, Lang AJ, Atkinson JH. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2098–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong SY, Chan FW, Wong RL, Chu MC, Lam YY, Mercer SW, Ma SH. Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and multidisciplinary intervention programs for chronic pain: A randomized comparative trial. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:724–734. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182183c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]