Abstract

Objective

To characterize the clinical response and identify predictors of clinical stabilization after intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) support in patients with chronic systolic heart failure in cardiogenic shock prior to implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Background

Limited data exist regarding the clinical response to IABP in patients with chronic heart failure in cardiogenic shock.

Methods

We identified 54 patients supported with IABP prior to LVAD implantation. Criteria for clinical decompensation after IABP insertion and before LVAD included the need for more advanced temporary support, initiation of mechanical ventilation or dialysis, increase in vasopressors/inotropes, refractory ventricular arrhythmias, or worsening acidosis. The absence of these indicated stabilization.

Results

Clinical decompensation after IABP occurred in 23 (43%) patients. Both patients who decompensated and those who stabilized had similar hemodynamic improvements after IABP support but patients who decompensated required more vasopressors/inotropes. Clinical decompensation after IABP was associated with worse outcomes after LVAD implantation, including a 3-fold longer intensive care unit stay and 5-fold longer time on mechanical ventilation (p<0.01 for both). While baseline characteristics were similar between groups, right and left ventricular cardiac power indices (Cardiac power Index= Cardiac Index × Mean arterial pressure / 451)identified patients who were likely to stabilize (AUC=0.82).

Conclusions

Among patients with chronic systolic heart failure who develop cardiogenic shock, more than half of patients stabilized with IABP support as a bridge to LVAD. Baseline measures of right and left ventricular cardiac power, both measures of work performed for a given flow and pressure, may allow clinicians to identify patients with sufficient contractile reserve who will be likely to stabilize with an IABP versus those who may need more aggressive ventricular support.

Keywords: Intra-aortic Balloon Counterpulsation, Cardiogenic Shock, Left Ventricular Device implantation, IABP, Heart failure, percutaneous support

Introduction

Implantation of left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) has markedly increased during the last decade(1). Patients with severe, chronic heart failure who develop cardiogenic shock (CS) are currently supported with vasopressors, inotropes and/or temporary mechanical circulatory support prior to LVAD implantation. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) has been a common form of mechanical circulatory support for more than 50 years(2). More recently, enhanced percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices have emerged as alternatives to IABP, including Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, MA; USA), Tandem Heart (CardiacAssist Inc., Pittsburgh, PA; USA), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as they are more complete surrogates for ventricular pump function(3). Although these devices provide more hemodynamic support, they are more complicated to insert and manage, and carry a higher risk of adverse vascular events(4). The benefit and role IABP plays in chronic heart failure patients with CS who require mechanical hemodynamic support as a bridge to LVAD implantation remains unclear.

We investigated the hemodynamic and clinical effects of IABP support instituted prior to planned LVAD implantation in a population of chronic heart failure patients with a depressed ejection faction and CS refractory to standard medical therapy.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, single center analysis of patients receiving IABP support prior to implantation of an LVAD. The Barnes Jewish Hospital electronic medical record was queried to identify all patients who had undergone LVAD (continuous) placement from 1998-2013. Patients who had an IABP placed prior to LVAD implantation were included with the median year of support being 2011 (range 2003-2013). We classified patients into two groups: 1) those who clinically decompensated further after IABP insertion; and 2) those who clinically stabilized after IABP insertion. Our classification criteria were selected to reflect an assessment of end organ perfusion and the level of support required to provide adequate end organ perfusion. End organ hypoperfusion is a known determinant of mortality in CS(5), along with measures of cardiac flow(5,6) and levels of vasopressor support(7). Patients were considered to have clinical decompensation if they met any of the following criteria at any time point after IABP insertion: 1) the need for any other form of temporary mechanical support (eg. Impella, Tandem Heart, temporary LVAD or ECMO); 2) any increase in dose or number of vasopressor or inotrope support; 3) initiation of renal replacement therapy; 4) initiation of mechanical ventilation; 5) refractory ventricular arrhythmias; or 6) severe or worsening metabolic acidosis as determined by serum bicarbonate level(Table 1). Patients who did not meet any of these criteria of decompensation were considered to be stabilized after IABP placement. Patients were excluded if they had acute myocardial infarction within the index hospitalization, cardiogenic shock post cardiac surgery or had placement of a total artificial heart as a bridge to transplant.

Table 1.

Clinical Decompensation Criteria.

| Criteria for further clinical decompensation after IABP placement |

| 1. Need for temporary mechanical circulatory support other than IABP |

| 2. Any increase in dose or addition of vasopressors or inotropes |

| 3. Initiation of renal replacement therapy |

| 4. Initiation of mechanical ventilation |

| 5. Refractory ventricular arrhythmias: Ventricular arrhythmias not controlled by conventional medications |

| 6. Worsening metabolic acidosis: sustained severe acidosis as defined by serum bicarbonate < 17 mg/dl that did not improve |

Clinical data were obtained from the medical record and the most recent echocardiogram and electrocardiogram prior to IABP placement were reviewed. Clinical decompensation or stabilization was determined after extraction of hemodynamic and clinical variables. For echocardiographic variables, all measurements were made in triplicate (when available) by readers who were blinded to clinical outcomes. All measurements were made according to current American Society of Echocardiography guidelines. Hemodynamic measurements were abstracted from the medical record and averaged for the 6 hours prior to IABP insertion and up to 12 hours following IABP insertion. Laboratory values were abstracted from the medical record and averaged for the time period prior to IABP insertion and post IABP insertion. Cardiac power index was calculated according to Fincke et. al(6,8,9) and stroke work index was calculated according to Ochiai et. al(10). Both parameters were calculated for the right (RV) and left (LV) ventricles using the relevant hemodynamic measurements.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables were summarized as mean±SD and evaluated using an independent or paired Student’s t-test as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or chi-square as indicated. In order to identify clinically useful cut-points, an optimal cut-point to discriminate patients who decompensated versus stabilized after IABP was determined for those variables that were different between the two groups using Youden’s index in an analysis of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Positive and negative predictive values for these cut-points were calculated using the prevalence of IABP stabilization in our population. Missing data was not imputed and analyses were performed on the data available. Kaplan-Meier (KM) analyses and the log-rank test were utilized to evaluate the association between clinical decompensation after IABP placement and clinically meaningful endpoints, including death, length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), and length of time on a ventilator. ICU and ventilator time were censored at death or transplantation.

Results

We identified 56 patients who had IABP support prior to LVAD implantation between the years 2003-2013. Two patients were excluded (Figure 1). No patients had an acute myocardial infarction resulting in CS during the index hospitalization and all were INTERMACS levels 1 or 2 prior to LVAD implant. Of the 54 patients that formed our analysis population, 23 patients (43%) met criteria for further clinical decompensation after IABP, whereas 31 (57%) clinically stabilized. The most common criteria met for clinical decompensation was an increased requirement for vasopressors or inotropes (n=14; 61%) followed by additional temporary mechanical support (n=6; 26%). During the study period, 11.1%(n=32) of 289 patients who received an LVAD without IABP were on at least one vasopressor on the day prior to LVAD implant compared to 37% (n=20) of patients who were on at least one vasopressor prior to IABP insertion(p <0.001).

Figure 1.

Patient Selection and Study Design

*See table 1 for clinical decompensation criteria. 15 patients met only 1 criterion; 4 met 2 criteria, 3 met 3 criteria and 1 met 4 criteria.

Baseline Clinical and Echocardiographic Characteristics

There were no differences in baseline clinical characteristics between patients who decompensated versus stabilized after IABP placement (Table 2). Echocardiograms performed prior to IABP placement were available for review on 49 patients (91%). Median days from echocardiogram to IABP placement was 2 days (range 0-192 days). Stabilized patients showed a higher peak tricuspid regurgitant velocity but otherwise all echo parameters were similar between groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic Variables Pre-IABP Insertion

| IABP Stabilized |

IABP Decompensated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| (n=31) | (n=23) | P value | |

| Baseline Variable | |||

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 56 ±9 | 51±13 | 0.11 |

|

| |||

| Body Surface Area (m2) | 2.05 ±0.28 | 2.06 ±0.26 | 0.98 |

|

| |||

| Female (%) | 13 | 26 | 0.29 |

|

| |||

| Race: | |||

| Caucasian (%) | 71 | 61 | 0.43 |

| African American (%) | 29 | 35 | |

| Other (%) | 0 | 4 | |

|

| |||

| Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (%) | 35 | 30 | 0.70 |

|

| |||

| Non-ischemic Cardiomyopathy (%) | 65 | 70 | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Chronic Kidney Disease (%) | 58 | 61 | 0.83 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes Mellitus (%) | 45 | 40 | 0.66 |

|

| |||

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(%) |

19 | 13 | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| Current smoker (%) | 13 | 9 | 0.68 |

|

| |||

| Peripheral arterial disease (%) | 6 | 0 | 0.50 |

|

| |||

| Home medications (%): | |||

| Any inotrope | 35 | 30 | 0.70 |

| Beta blocker | 58 | 56 | 0.91 |

| ACE-I/ARB | 67 | 47 | 0.14 |

| Hydralazine | 16 | 17 | 1.0 |

| Nitrates | 19 | 13 | 0.72 |

| Aldosterone Antagonists | 55 | 43.5 | 0.41 |

| Warfarin | 32 | 48 | 0.40 |

| Aspirin | 71 | 61 | 0.44 |

|

| |||

| AST (IntUnits/L) ** | 396±948 | 582±1160 | 0.53 |

|

| |||

| ALT (IntUnits/L) ** | 387±749 | 608±1205 | 0.4 |

|

| |||

| Bicarbonate (mMol/L) | 26±6 | 23±5 | 0.59 |

|

| |||

| Lactate (mMol/L) # | 3.8±2.6 | 2.7±1.8 | 0.29 |

|

| |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.9±0.7 | 2.2±1.2 | 0.30 |

|

| |||

| BUN (mg/dL) | 43±21 | 51±28 | 0.21 |

|

| |||

| GFR MDRD (ml/min/1.73m2) | 44±18 | 46±34 | 0.80 |

|

| |||

| Vasoactive Medications prior to IABP * | |||

| Inotrope (#) | 1.10±0.60 | 0.95±0.65 | 0.41 |

| Vasopressors (#) | 0.48±0.62 | 0.36±0.58 | 0.48 |

|

| |||

| Left Bundle Branch Block (%) | 7 (2/30) | 14 (3/22) | 0.64 |

|

| |||

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 19 (6/31) | 9 (2/22) | 0.44 |

|

| |||

| IABP size (ml) | 42.6±4.8 | 41.5±4.3 | 0.44 |

|

| |||

| IABP size indexed to BSA (ml/m2) | 21±2.5 | 20.1±2.6 | 0.27 |

No significant difference in mean medication dose prior to IABP.

AST/ALT not available on total 2 patients.

Lactate available for 13 stabilized patients and 8 decompensated patients. Disease classifications and medications were based on admitting history and physical prior to IABP insertion. Mean ± standard deviation given for all continuous variables.

Table 3.

Pre IABP Clinical Variables.

| IABP Stabilized | IABP Decompensated | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (mean±SD) | n | (mean±SD) | ||

| Echocardiographic Variables | |||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 30 | 18±1.3 | 17 | 17±1.4 | 0.65 |

| LV end diastolic dimension (cm) | 30 | 6.8±0.8 | 18 | 7.1±0.9 | 0.35 |

| LV end systolic dimension (cm) | 30 | 6.3±0.8 | 18 | 6.4±0.9 | 0.58 |

| LVOT VTI (cm) | 28 | 10.7±4.9 | 17 | 11.1±4.4 | 0.74 |

| E wave velocity (cm/sec) | 27 | 107±27 | 18 | 103±22 | 0.61 |

| Septal annular e’ velocity (cm/sec) | 24 | 4.3±2.6 | 18 | 4.5±2.0 | 0.77 |

| Septal E/e’ | 24 | 32±18 | 18 | 28±17 | 0.52 |

| LV Tei Index | 25 | 0.84±0.32 | 14 | 0.86±0.56 | 0.88 |

| TAPSE (cm) | 20 | 1.5±0.6 | 8 | 1.6±0.6 | 0.70 |

| Peak TR velocity (msec) | 28 | 3.1±0.4 | 18 | 2.8±0.5 | 0.05 |

| Inferior Vena Cava Diameter (cm) | 27 | 2.3±0.5 | 17 | 2.5±0.5 | 0.19 |

|

Moderate/Severe Mitral Regurgitation

(%) |

30 | 57 | 19 | 47 | 0.52 |

| Severe RV Failure (%) | 28 | 21 | 19 | 11 | 0.44 |

| Hemodynamic Variables | |||||

| Systolic Blood pressure(mmHg) | 31 | 97±14 | 23 | 95±14 | 0.51 |

| Diastolic Blood pressure(mmHg) | 31 | 66±10 | 23 | 64±10 | 0.41 |

| Mean arterial Pressure(mmHg) | 31 | 74±11 | 23 | 72±12 | 0.46 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 31 | 94±25 | 23 | 94±18 | 1.0 |

| Cardiac Index (l/min*m2) | 22 | 2.03±0.67 | 13 | 1.7±0.42 | 0.10 |

| Right atrial Pressure(mmHg) | 23 | 15±6 | 14 | 16±7 | 0.49 |

|

Pulmonary Artery Systolic pressure

(mmHg) |

15 | 54±10 | 9 | 44±7 | 0.02 |

|

Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure

(mmHg) |

23 | 39±7 | 14 | 34±12 | 0.18 |

|

Pulmonary Capillary wedge pressure

(mmHg) |

23 | 28±7 | 13 | 28±7 | 0.95 |

| Stroke Volume Index (ml/m2) | 22 | 22±9 | 13 | 19±8 | 0.33 |

| Systemic Vascular resistance (WU) | 22 | 16.5±6.5 | 13 | 18.9±7.4 | 0.38 |

| Pulmonary Vascular Resistance(WU) | 22 | 3.1±2.8 | 12 | 3.0±2.5 | 0.84 |

|

Left Ventricular Cardiac Power Index

(watts/m2) * |

22 | 0.33±0.11 | 13 | 0.27±0.04 | 0.05 |

|

Right Ventricular Cardiac Power Index

(watts/m2) ** |

22 | 0.17±0.05 | 13 | 0.125±0.04 | 0.02 |

|

Right Ventricular Stroke Work Index

(mmHg*ml/m2) ¥ |

22 | 514±260 | 13 | 354±198 | 0.07 |

|

Left Ventricular Stroke Work Index

(mmHg*ml/m2) ¥¥ |

22 | 1040±480 | 12 | 874±380 | 0.31 |

cardiac power = mean arterial pressure × cardiac index;

Right Ventricular cardiac power=mean pulmonary pressure × cardiac index

Right ventricular stroke work index= (mean PA-mean RA)*stroke volume index

left ventricular stroke work index=(mean arterial –pulmonary capillary wedge pressure)*stroke volume index.

All continuous values reported as Mean ± Standard Deviation

Baseline and Post-IABP Hemodynamics

At baseline, there were no significant differences in systolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, heart rate, systemic or pulmonary vascular resistance, right atrial pressure or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure between groups (Table 3). Compared to those that decompensated after IABP placement, patients that clinically stabilized after IABP placement had higher LV and RV ventricular cardiac power indices, a trend toward a higher cardiac index at baseline and higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure at baseline (Table 3).

When comparing post-IABP hemodynamic indices between those who clinically stabilized versus those who decompensated further, there were no significant differences between groups in LV or RV cardiac power indices, cardiac index, or pulmonary artery, right atrial, or pulmonary capillary wedge pressures (Figure 2a-f). However, those who decompensated further after IABP placement were on more vasopressors or inotropes, whereas those who stabilized clinically were on fewer (Figure 2g). Markers of renal function including GFR were not different between groups after IABP placement but there was increased urine output on the day after compared to the day prior to IABP insertion in the stabilized group (Figure 2h). Lactate levels were not routinely available after IABP placement.

Figure 2. Hemodynamic Improvements after IABP support.

(A)Left ventricular Cardiac power index and change after IABP, (B)Right ventricular cardiac power index and change after IABP, (C)Pulmonary artery systolic pressure and change after IABP, (D) Cardiac Index and change after IABP, (E) pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and change after IABP, (F) right atrial pressure and change after IABP, (G)vasoactive medication number and change after IABP, and (H)urine output and change after IABP support in those who stabilized and decompensated. Values represented as a mean with standard deviation bars shown. Minimum and maximum bars shown for the change in respective values with box plots representing the median, 25th and 75th percentiles. Significance for change in hemodynamic values and clinical variables was determined with a paired T test between IABP stabilized and decompensated groups. *denotes p value <0.05 for paired T test within the group (i.e. pre and post measurements for stabilized and decompensated groups). **Significance for change in vasoactive medications was determined by Mann-Whitney U test for changes between stabilized and decompensated groups and a matched samples Wilcoxon Ranked sign test for within group changes.

Clinical outcomes associated with response to IABP

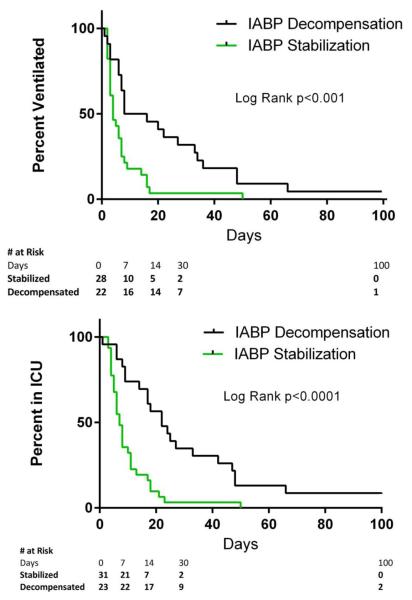

Both groups had a similar median duration of IABP support prior to LVAD or other forms of mechanical support (2 days for decompensated versus 3 days for stabilized; p=0.50). Patients who decompensated after IABP support had a longer median post-LVAD implantation intensive care unit stay than stabilized patients (25 days, 95% CI 17 to 266 vs. 8 days, 95% CI 6 to 11, p<0.001) (Figure 3). Similarly, time until extubation after LVAD implant was longer for patients who decompensated than those who stabilized (median = 20 days, 95% CI 7 to 36 vs. 4 days, 95% CI 3 to 7, p<0.001) (Figure 3). There was no difference in Kaplan Meir mortality estimates between groups (log rank p=0.32, 9 total deaths). Transfusion data was available for 44 patients treated with IABP and 288 patients who received an LVAD during the same time period but did not receive an IABP prior to LVAD implant. IABP before LVAD was associated with more post-operative red blood cell transfusions but no statistically significant increase in intra-operative or total packed red cell transfusions or post-operative platelet or fresh frozen plasma transfusions (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 3. Post LVAD outcomes.

(A) Intensive care unit days and (B) ventilator days post LVAD implantation for patients who stabilized or decompensated after IABP support. Ventilator and ICU days censored at death or transplantation. Univariate Mantle-Cox Log Rank test used to compare groups.

Identifying clinical responders to IABP

Using an optimal cut-point of 0.13 watts/m2, RV cardiac power index was associated with IABP response with an AUC (95% CI) = 0.74 (0.56, 0.93) and a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 69%, yielding a positive predictive value (PPV) of 82% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 69%. LV cardiac power index showed a very high specificity but lower sensitivity and discrimination with an AUC (95% CI) = 0.68 (0.50, 0.86); cutpoint = 0.33 watts/m2; sensitivity = 41%, specificity = 100%.. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure alone was highly predictive with an AUC (95% CI) =0.79 (0.61, 0.98); cutpoint = 52 mmHg; sensitivity = 60%, specificity =89%.. RV stroke work index showed reasonable predictive accuracy for stabilization (AUC (95%CI) 0.71(0.5,0.9) but was not as robust as the more simplified RV cardiac power index. Receiver operator characteristics are shown in the data supplement Figure 1. These findings suggest that differences in baseline LV and RV function had differing predictive capabilities. To explore this further, we combined hemodynamic parameters using ROC cutpoints into a simple score composed of RV and LV cardiac power indices.For each parameter above the ROC cutpoint, one point was awarded and scores were evaluated for predictive accuracy for no points versus any points. Having either one of both RV or LV ventricular cardiac power indices above the ROC cutpoint (score ≥1) resulted in a positive predictive value of 82% for stabilization, with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 69% (Figure 4).

Figure 4. IABP stabilization Score.

Patients received one point for a right ventricular cardiac power output ≥ 0.13 watts/m2 or left ventricular cardiac power index ≥ 0.33 watts/m2. Only patients with both values available prior to IABP insertion were included.

Discussion

In a group of patients with chronic heart failure and CS who had an IABP placed prior to LVAD implantation, 43% experienced further clinical decompensation whereas 57% were stabilized. Clinical decompensation after IABP had important clinical consequences, including a 3-fold longer ICU stay and a 5-fold longer time on mechanical ventilation after LVAD implantation. While patients who decompensated experienced similar hemodynamic changes after IABP support as those who were stabilized, they required an increase in vasopressors/inotropes. While most baseline characteristics were similar between those who decompensated versus stabilized with IABP support, we identified RV and LV cardiac power indices and pulmonary artery pressure as potentially helpful parameters to predict the clinical response to IABP insertion, suggesting that patients with some contractile reserve are more likely to benefit from IABP. Viewed together these findings may provide a novel way to determine which heart failure patients may benefit the most from differing temporary mechanical circulatory support therapies prior to LVAD implantation.

IABP utilization has shown limited or no clinical benefit in patients with CS complicating acute myocardial infarction[10,11,12]. IABP-SHOCKII(12), the largest randomized controlled to date evaluating IABP support in CS, enrolled 600 patients with CS complicating acute myocardial infarction and showed no mortality benefit. ISARSHOCK(13) compared IABP to percutaneous Impella support in 25 patients with CS complicating acute myocardial infarction and found only minimal improvement in hemodynamic values immediately after IABP support. These data suggest IABP has little clinical or hemodynamic benefit for patients with CS complicating acute myocardial infarction and as such many centers are seeing a decline in IABP utilization for all patients in CS. However, these trials did not address IABP use in patients with CS complicating chronic heart failure.

Patients with chronic systolic heart failure who develop CS are physiologically different than patients who develop CS as a complication of an acute myocardial infarction in that chronic heart failure has led to ventricular remodeling(14). IABP increases coronary blood flow, increases diastolic blood pressure, reduces isovolumetric contraction time and ventricular afterload(15). Although these characteristics are intuitively helpful to support patients in CS after infarction, IABP is chiefly a volume displacement pump and not a forward flow pump. Counterpulsation involves diastolic displacement of blood within a fixed intravascular space resulting in decreased aortic systolic pressure and impedance and in turn systolic unloading of the LV. As such, any increase in stroke volume is a result of better ventricular performance, not augmentation from the support device. These characteristics have not been associated with a decrease in left ventricular work(16,17). In chronic heart failure, IABP reduces arterial impedance(18) and the resultant increase in stroke volume may be enough to rescue patients from severe shock. As an example, Rosenbaum et. al(19) published a retrospective study on 55 patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, none having active unstable angina at the time of IABP placement. All hemodynamic parameters significantly improved suggesting a differential clinical response to IABP therapy in patients with chronic heart failure.

Our study provides additional evidence that IABP can provide clinical benefit in patients with chronic heart failure in shock. More than half of patients were clinically stabilized after IABP, showing a significant decrease in the number of inotropes and vasopressors and a trend towards improved cardiac power compared to those patients who deteriorated. Both factors have been associated with positive outcomes in previous clinical trials of cardiogenic shock, particularly cardiac power(6,7). Cardiac Power has also been shown to have prognostic importance for patients with chronic heart failure not in shock(20) Additionally, hemodynamic improvements mirror the results of Rosenbaum et. al(19) and show substantial improvement in indices of both left and right ventricular function. Importantly, while patients who decompensated experienced improvements in several hemodynamic indices, these improvements came at the expense of an increase in inotrope and vasopressor support. Analysis of the prospective randomized trial TRIUMPH suggested that in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by CS, for each additional vasopressor added the risk of death increased by 53%(7). This highlights, albeit in a different population than our study, the negative impact of an increased afterload in the management of cardiogenic shock.

Although it has previously been reported that patients with end-stage heart failure can derive clinical benefit from the insertion of IABP, our findings are the first to offer guidance for appropriate patient selection. Ventricular function, in the form of various hemodynamic measures of flow and work, proved to be the most predictive of IABP response. IABP provides unloading to the failing ventricle, including the RV(21), in the form of volume displacement. Accordingly, it seems fitting that the magnitude of the response to IABP support would depend on intrinsic myocardial function to fill the displaced volume (i.e. contractile reserve). In animal models of acute left ventricular failure(22); as the contractile function becomes more severely impaired the hemodynamic benefits of IABP are lost. Our data also highlight the need for sufficient contractile reserve for both the RV and LV to benefit from the unloading mechanism of IABP. Although not directly measured, contractile reserve could be approximated with available invasive measures of ventricular function. The combination of both LV and RV function in the form of cardiac power indices provides a promising threshold of contractile reserve that could be expected to respond to IABP unloading. These measures of cardiac power couple both flow and pressure to uniquely and simply assess ventricular work. Patients who had either RV or LV power indices above the given cutpoints had an 81% chance of stabilizing with IABP prior to LVAD. Importantly, patients who do stabilize with IABP had shorter unadjusted ICU and ventilator days after LVAD implantation, outcomes that not only support the validity of the decompensation criteria but also indicate the significant economic implications of a patient’s response to IABP. Finally this improved morbidity is no doubt a reflection of improved baseline ventricular function and contractile reserve; both of which we believe are selected for by clinical stabilization after IABP support.

Clinical Implications

Not infrequently, patients with chronic heart failure who develop CS may remain refractory to aggressive medical therapy. Consideration is often given as to whether and which temporary mechanical support may be required as a bridge to LVAD implantation. Our findings suggest that a subgroup of patients with chronic heart failure and CS can be successfully stabilized with less invasive IABP. To guide this decision, we provide a simple score that incorporates hemodynamic cutpoints of cardiac power for both the right and left ventricles . Alternatively, those patients with a high probability of meeting our decompensation criteria (i.e. a IABP score <1) could potentially be treated sooner with more aggressive forms of mechanical support.

Study Limitations

This was a single center retrospective study and limited to the analysis of patients who went on to LVAD implantation. This restriction means our data are more clearly applicable to patients who are deemed candidates for permanent circulatory support and represents the evaluation of true cases of CS in patients with chronic heart failure. More detailed comparisons between patients who received an LVAD and no IABP during the study period were not available. Additionally we have no insight into the parameters the clinician used to make the decision for IABP support; experienced heart failure physicians selected these patients for increased circulatory support and the observations and predictions presented here are best taken in this context. Finally, given the small sample size we were unable to adjust for other important clinical variables. This study should serve as a basis for further prospective studies evaluating IABP in this population, including validation of the IABP score

Conclusion

IABP is a clinically useful support device for select patients with chronic heart failure in CS as a bridge to LVAD. It provides significant improvements in hemodynamic parameters for most patients but in those patients who clinically stabilize these improvements occur along with a decrease in inotrope and vasopressor support. RV and LV power indices, incorporated into a simple clinical score, offer a novel way to identify those patients who are likely to stabilize after IABP versus those who may have a better outcome with earlier, more aggressive forms of temporary mechanical support. Further studies are needed to refine these patient selection criteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge data management and acquisition support from the Clinical Investigation Data Repository (CIDER) and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants 5T32HL007081-39 (MAS), K23 HL116660 (BRL), KO8:HL123519 (KJL) Oliver Langenberg Physician Scientist Training Program (KJL), NIH R01 HL 111094 (DLM)

Abbreviations

- IABP

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation

- LVAD

Left ventricular Assist Device

- CS

cardiogenic Shock

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- LV

Left Ventricle

- RV

Right Ventricle

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Pagani FD, Miller MA, et al. Fifth INTERMACS annual report: risk factor analysis from more than 6,000 mechanical circulatory support patients. J Heart Lung Transplant Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transplant. 2013 Feb;32(2):141–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantrowitz A, Tjonneland S, Freed PS, Phillips SJ, Butner AN, Sherman JL., Jr. Initial clinical experience with intraaortic balloon pumping in cardiogenic shock. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1968 Jan 8;203(2):113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werdan K, Gielen S, Ebelt H, Hochman JS. Mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2014 Jan;35(3):156–67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouweneel DM, Henriques JPS. Percutaneous cardiac support devices for cardiogenic shock: current indications and recommendations. Heart Br Card Soc. 2012 Aug;98(16):1246–54. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sleeper LA, Reynolds HR, White HD, Webb JG, Dzavík V, Hochman JS. A severity scoring system for risk assessment of patients with cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK Trial and Registry. Am Heart J. 2010 Sep;160(3):443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, Menon V, Slater JN, Webb JG, et al. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Jul 21;44(2):340–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz JN, Stebbins AL, Alexander JH, Reynolds HR, Pieper KS, Ruzyllo W, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality in patients with refractory cardiogenic shock following acute myocardial infarction despite a patent infarct artery. Am Heart J. 2009 Oct;158(4):680–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kussmaul WG, Altschuler JA, Matthai WH, Laskey WK. Right ventricular-vascular interaction in congestive heart failure. Importance of low-frequency impedance. Circulation. 1993 Sep;88(3):1010–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saouti N, Westerhof N, Helderman F, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Postmus PE, et al. Right ventricular oscillatory power is a constant fraction of total power irrespective of pulmonary artery pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Nov 15;182(10):1315–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1643OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochiai Y, McCarthy PM, Smedira NG, Banbury MK, Navia JL, Feng J, et al. Predictors of severe right ventricular failure after implantable left ventricular assist device insertion: analysis of 245 patients. Circulation. 2002 Sep 24;106(12 Suppl 1):I198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unverzagt S, Machemer M-T, Solms A, Thiele H, Burkhoff D, Seyfarth M, et al. Intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation (IABP) for myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. In: The Cochrane Collaboration; Prondzinsky R, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet] John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: [cited 2013 Mar 1]. 2011. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007398.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann F-J, Ferenc M, Olbrich H-G, Hausleiter J, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012 Oct 4;367(14):1287–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I, Fröhlich G, Bott-Flügel L, Byrne R, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intraaortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Nov 4;52(19):1584–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation. 2005 May 31;111(21):2837–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santa-Cruz RA, Cohen MG, Ohman EM. Aortic counterpulsation: a review of the hemodynamic effects and indications for use. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2006 Jan;67(1):68–77. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauren LDC, Accord RE, Hamzeh K, de Jong M, van der Nagel T, van der Veen FH, et al. Combined Impella and intra-aortic balloon pump support to improve both ventricular unloading and coronary blood flow for myocardial recovery: an experimental study. Artif Organs. 2007 Nov;31(11):839–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyce DL, Joyce LD, Loebe M. Mechanical circulatory support principles and applications. McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SY, Euler DE, Jacobs WR, Montoya A, Sullivan HJ, Lonchyna VA, et al. Arterial impedance in patients during intraaortic balloon counterpulsation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996 Mar;61(3):888–94. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum AM, Murali S, Uretsky BF. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation as a “bridge” to cardiac transplantation. Effects in nonischemic and ischemic cardiomyopathy. Chest. 1994 Dec;106(6):1683–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang CC, Karlin P, Haythe J, Lim TK, Mancini DM. Peak cardiac power output, measured noninvasively, is a powerful predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009 Jan;2(1):33–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.798611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordhaug D, Steensrud T, Muller S, Husnes KV, Myrmel T. Intraaortic balloon pumping improves hemodynamics and right ventricular efficiency in acute ischemic right ventricular failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Oct;78(4):1426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feola M, Haiderer O, Kennedy JH. Intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP) at different levels of experimental acute left ventricular failure. Chest. 1971 Jan;59(1):68–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.59.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.