Abstract

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6, a major contributor to the metabolism and bioactivation of many clinically used drugs, is encoded by a complex, highly polymorphic gene locus. To aid in the characterization of CYP2D6 allelic variation, we developed allele-specific long-range PCR (ASXL-PCR) to amplify only the allele of interest for further characterization by PCR. This development was achieved utilizing single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the upstream region of CYP2D6 and a universal CYP2D6-specific reverse primer. This approach was assessed and optimized on samples with known genotypes. The application of ASXL-PCR clarified a case with a complex genotype (CYP2D6*2x2/*4N+*4) by amplifying the duplicated gene units separately for subsequent analysis. Furthermore, ASXL-PCR and subsequent sequence analysis also resolved genotype discord in a mother/daughter relationship by revealing the presence of the CYP2D6*59 allelic variant in both individuals. Finally, we demonstrated that the 2939G>A single-nucleotide polymorphism present on CYP2D6*59 interfered with the TaqMan genotype assay that detected 2850C>T, causing false genotype assignments. Assay interference was resolved using an alternative TaqMan genotype assay currently available as a custom-made assay. These examples demonstrate the utility of ASXL-PCR for improved CYP2D6 allele/haplotype characterization. This fast, easy-to-perform method is not limited to CYP2D6 but can be adapted to any gene locus for which polymorphic sites are known.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 is involved in the metabolism and disposition of many clinically used drugs.1, 2 The gene encoding CYP2D6 is highly polymorphic. Over 100 allelic variants and subvariants have been defined to date in the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database (http://www.cypalleles.ki.se, last accessed May 14, 2015).3 This count does not include numerous variants that have been published but not submitted to the Nomenclature Database or that did not meet the current requirements for star allele assignment. There is also a growing list of single-nucleotide variants for which no haplotype or functional consequence has been determined.

Genetic variation is the single most important factor contributing to a large range of variation in CYP2D6 enzymatic activity among individuals. At the extreme ends of the population distribution are poor metabolizers and ultrarapid metabolizers, presenting with no activity and elevated CYP2D6 activity, respectively; extensive metabolizers and intermediate metabolizers have normal activity and various degrees of reduced activity, respectively.4, 5, 6, 7 Poor metabolizers and ultrarapid metabolizers are at an elevated risk for dose-related adverse events or failing to achieve therapeutic levels, depending on whether the therapeutic activity of a drug is terminated by CYP2D6 or requires bioactivation through this pathway.

To avoid adverse events and to optimize drug treatment, CYP2D6 genotype analysis is increasingly utilized in the clinic,8, 9 and guidelines for aiding clinicians with genotype interpretation are being developed.10, 11 As summarized by Gaedigk,12 the CYP2D6 gene locus is affected by a large number of single-nucleotide variants, of which some are unique and can be utilized as markers for allele identification (eg, CYP2D6*3 carries 2549delA). Other SNPs, however, can occur on multiple haplotypes and thereby provide challenges to accurate haplotype assignment and phenotype prediction. This phenomenon is exemplified by 100C>T, which is a part of 19 defined haplotypes (CYP2D6*4, *10, *14, *36, *37, *47, *49, *52, *54, *56, *57, *64, *65, *68, *72, *94, *95, *100, and *101). The CYP2D6*10 reduced-function allele is characterized as having no consequential single-nucleotide variants in addition to 100C>T. The nonfunctional CYP2D6*4 haplotype, however, carries 1846G>A in addition to 100C>T, although, in rare cases, 1846G>A has been observed without 100C>T being present (referred to as CYP2D6*4M). A more complex example is the CYP2D6*64 allele, characterized by a haplotype that includes 100C>T as well as 1023C>T and 2850C>T, which are typically associated with the CYP2D6*17 haplotype.

Genotype calls are routinely accomplished by making allele assignments that reflect the greatest probability of SNP linkage. For example, if a subject is heterozygous for both 100C>T and 1846G>A, there is a high probability that these SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium, that is, that both are on the same chromosome and inherited together as an allele designated CYP2D6*4. Consequently, a CYP2D6*1/*4 genotype will be called. However, in rare instances, these two SNPs occur in trans, that is, are located on opposite chromosomes; in this case, the genotype should be called as CYP2D6*4M/*10 per the current Nomenclature Database guideline. The difference is a genotype call of one functional allele for CYP2D6*1/*4 and a reduced-function allele for CYP2D6*4M/*10 and is just one example illustrating the ambiguity of allele assignments and the challenge of making accurate genotype calls.12, 13

Resequencing is the method of choice for investigating and characterizing novel allelic variants or for validating genotype results. Resequencing can easily be achieved by generating a PCR fragment and subjecting it to sequencing. However, the phase of the SNPs observed, or haplotype, generally cannot be deduced from the sequencing data derived directly from genomic (g)DNA. Exceptions are those rare cases with particular CYP2D6 diplotypes, in which the allele of interest on one chromosome is paired with a chromosome that lacks the entire gene (CYP2D6*5) or features a CYP2D7/2D6 hybrid (CYP2D6*13). Because deletion alleles and CYP2D7/2D6 hybrid genes do not support amplification with CYP2D6-specific primers located upstream and downstream of the gene, the sequence directly obtained from a long-range (XL)-PCR template represents only one chromosome.

Although the linkage of SNPs in close proximity can tentatively be determined using allele-specific (AS) amplification,14, 15 the determination of haplotypes over a larger region, such as the entire CYP2D6 gene, including flanking 5′- and -3′ regions, requires cloning of XL-PCR fragments and subsequent sequencing. Although we have successfully used this approach to characterize novel CYP2D6 variants,14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 the procedure is cumbersome due to low cloning efficiencies and the potential presence of PCR errors in a given plasmid clone.

To facilitate the characterization of novel allelic variants of CYP2D6 and to validate or determine haplotypes in samples with ambiguous diplotype calls, we developed a set of primers that support the generation of ASXL-PCR products that encompass the entire CYP2D6 gene. AS-PCR products can be sequenced directly using standard procedures. This report describes the method of ASXL-PCR and provides two examples of its application: i) resolution of discordant genotype calls involving the CYP2D6*59 allele within a family pedigree and ii) characterization of a subject carrying gene-duplication events on both chromosomes.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Subjects were enrolled in a repository for DNA usage in studies of genes involved in drug absorption, disposition, metabolism, and excretion. The protocol was approved by the Children's Mercy Hospital Pediatric Institutional Review Board (Kansas City, MO). Data were deidentified, but subjects' relatedness was captured at the time of enrollment.

Samples suspected of harboring novel variants, obtained from an ongoing study (Exogenous and Endogenous Markers of CYP2D6 in Pediatrics; study number R01 HD058556-05), were also evaluated using a protocol approved by the Children's Mercy Hospital Pediatric Institutional Review Board. The urinary metabolic ratio of dextromethorphan/dextrorphan, also obtained from the ongoing study, was utilized for assessing the functional consequences and in vivo phenotypes associated with revised genotypes determined in the current investigation.

DNA Isolation

gDNA was isolated from white blood cells, using a sodium chloride precipitation protocol, or from whole blood, using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After gDNA quality was ensured by agarose gel electrophoresis, concentration was determined using a Synergy HT spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT) and was adjusted to 15 ng/μL. gDNA samples used as controls in this investigation were previously extensively genotyped for CYP2D6 and/or sequenced (see XL-PCR).

XL-PCR

XL-PCR reactions contained 1X Long Range HotStart Ready Mix (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA), 10 ng of gDNA, 0.5 μmol/L each primer, and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide. Cycling conditions included an initial denaturation for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 68°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 68°C for 7.5 or 13 minutes (Table 1). Primer sequence, location of binding, and lengths of XL-PCR products are provided in Table 1. After cycling was complete, 1 to 2 μL of PCR product was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 1.

List of Primer Sequences, Fragment Lengths, and PCR Conditions

| Primer sequences | SNP position | Length, bp | Tann, °C |

|---|---|---|---|

| F: 5′-TCACCCCCAGCGGACTTATCAACC-3′∗ | Universal fragment A forward primer† | ||

| F: 5′-TGGAGAGAGGCCACCTGAGGTAGTC-3′ | -2609A>C | 7388 | 63 |

| F: 5′-CGTCAAGCTTTCCGACATACACG-3′ | -2523G>A | 7300 | 68 |

| F: 5′-CCTCCCAAATCTGATGAAAAATATTAATCC-3′ | -2421T>C | 7205 | 63 |

| F: 5′-GAGGCAACCTGCTCGGG-3′ | -2178G>A | 6949 | 63 |

| F: 5′-CCTGGACAACTTGGAAGAACCC-3′ | -1584C>G | 6360 | 65 |

| F: 5′-CCTGGACAACTTGGAAGAACCG-3′ | -1584C>G | 6360 | 70 |

| F: 5′-CATGGTGAAACCCTATCTCTACTGAAAATAC-3′ | -1426C>T | 6211 | 63 |

| F: 5′-CAGAAAGCAGTGGAGGAGGACG-3′ | -1000G>A | 5776 | 70 |

| F: 5′-TGTGTGTGAGAGAGAATGTGTGCC-3′ | -740C>T | 5518 | 68 |

| R: 5′-CGACTGAGCCCTGGGAGGTAGGTAG-3′ | Universal fragment A reverse primer† | ||

| F: 5′-CCAGAAGGCTTTGCAGGCTTCAG-3′ | Universal fragment D forward primer† | ||

| R: 5′-CGGCAGTGGTCAGCTAATGAC-3′ | Universal fragment D reverse primer†‡ | ||

Only the primers yielding allele-specific (AS) amplification are listed. Length in bp indicates the length of the long-range AS-PCR product when paired with the universal fragment A reverse primer. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) positions correspond to AY545216 (+1 = A in the ATG translation start codon). Nucleotides providing AS amplification are underlined. Tann (°C) denotes the annealing temperature at which the primer produced AS amplification.

F, forward; R, reverse.

The forward primer was modified from that described previously for amplification of fragment A.21

Primer is not allele-specific.

PCR extension time for the universal duplication primer paired with the AS forward primer was 13 minutes.

To achieve AS amplification, eight SNPs in the upstream region [-2609, -2523, -2421, -2178, -1584, -1426, -1000, and -740; numbering in reference to GenBank Accession numbers AY545216 and M33388 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)] were chosen as targets for AS priming. We designed a pair of primers for these SNP positions that differed at their 3′ ends to match to either the wild-type or variant nucleotide, as shown in Table 1. Each AS forward primer was paired with a CYP2D6-specific universal reverse primer that we routinely use for amplifying XL-PCR fragment A21 and tested for specificity with a series of amplification reactions at increasing annealing temperatures, ranging from 63°C to 70°C. A universal fragment A forward primer was utilized for amplifying both alleles simultaneously.

The primer specific for the SNP at -740 was also successfully paired with the reverse primer amplifying duplicated genes (fragment D21) to discriminate between duplicated genes located on both chromosomes, or potentially in tandem.

Sanger Sequencing

XL-PCR products were generated as described above (see XL-PCR) and purified with a GenElute PCR Clean-Up Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO). XL-PCR products were diluted to 10 ng/μL and 1 μL used for each sequencing reaction. Sequencing was performed with BigDye Terminator version 3.1 chemistry and a capillary 3730 DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rochester, NY; formerly, Life Technologies Corporation). Sequence traces were aligned and analyzed using Sequencher software version 5.2.4 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI). GenBank accession numbers AY545216 and M33388 were used as reference sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore).

CYP2D6 Genotype Analysis

CYP2D6 genotyping was performed according to procedures described in detail elsewhere.14, 21, 22, 23 Briefly, a 6.6-Kb fragment was amplified with the CYP2D6-specific universal fragment A forward and reverse primers (Table 1). Formation of the product was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis before it was diluted 2000-fold with 10 mmol/L Tris pH 8 and used as a template to detect SNPs and other sequence variations, including nucleotide deletions and insertions. TaqMan SNP genotyping assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for the detection of sequence variations. Six-microliter reactions were performed in 96-well plates using the TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or the Probe qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems). Cycling was performed on a 7900 PCR System (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA; formerly, Applied Biosystems Inc.) according to the manufacturer's specifications, and data were analyzed with SDS software version 2.4 (MSDSpro LLC, Anchorage, AK). The CYP2D6*5 gene deletion, the presence of gene duplications/multiplications (XL-PCR fragment B), and CYP2D6*13-like CYP2D7/2D6 hybrid genes (fragment H) were assayed by XL-PCR as well. Copy number variation was assessed by quantitative multiplex PCR interrogating four different gene regions previously described.24 Subjects' samples were genotyped to detect CYP*2, *3, *4, *6, *7, *9, *10, *11, *12, *15, *17, *35, *29, *36, *40, *41, and *42. SNPs, rs numbers, and TaqMan assay IDs are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Based on the presence or absence of 2850C>T, subjects were tested for additional SNPs as indicated in Supplemental Table S1. In subjects carrying a gene duplication or a multiplication event, an 8-Kb XL-PCR product encompassing the duplicated gene was generated to determine which of the two alleles carries the copy number variation.21 This fragment was genotyped for the presence of sequence variations as described above (see CYP2D6 Genotype Analysis). Alleles are defined according to the Nomenclature Database.

Genotyping was performed on the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System, whereas assay comparison was performed with a QuantStudio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA).

High Resolution Melt Analysis

To detect the CYP2D6*59 tag SNP 2939G>A, high-resolution melt analysis was performed on universal fragment A, ASXL-PCR products, and gDNA as a template, using the following primers: forward, 5′-CCTCCTGCTCATGATCCTAC-3′; reverse, 5′-CGGCCCCTGCACTGTTT-3′. Six-microliter reaction volumes contained the following (final component concentrations): 1X Kapa HRM Fast Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems), 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.4 μmol/L each primer, and 0.6 μL of 2000-fold diluted XL-PCR template or 8 to 12 ng of gDNA. Cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C denaturation for five seconds, 59°C annealing for 10 seconds, and 60°C extension for 20 seconds. Cycling and data capture was performed on an Eco Real-Time PCR instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and analyzed using EcoStudy software version 5.0.

To detect the CYP2D7 exon 9 conversion, high resolution melt analysis was performed on fragments A and/or D, using the following primers: forward, 5′-ACCTCCCTGCTGCAGCA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGGCTGGGCCGGGGCT-3′. Reaction conditions were as described herein.

Results

Design, Optimization, and Validation of ASXL-PCR

AS amplification of the entire gene was achieved by exploiting SNPs located upstream of the gene. Although SNP information on some alleles and suballeles is available through the Nomenclature Database, on numerous variants this information remains unknown [whether SNP(s) are absent because no information was submitted for the upstream region is also not always obvious].

For ASXL-PCR, a pair of forward primers were designed, one matching the reference and one the variant allele (Figure 1A). Primer specificity was tested using gDNA samples of known CYP2D6 genotypes/SNP status. The -1584C>G primer amplified a 6358-bp fragment from a sample with a CYP2D6*1/*1 genotype (-1584C/C) but did not amplify when a CYP2D6*2A/*2A sample (-1584G/G) was used as template (Figure 1B). Other alleles with -1584C, such as CYP2D6*4, will also amplify with this primer. In contrast, primer -1584C>G amplified the CYP2D6*2A/*2A sample but was negative for the CYP2D6*1/*1 sample (not shown). This primer will not amplify from, for example, CYP2D6*4 alleles. It needs to be noted that the common CYP2D6*2A allele carries -1584G and therefore can be discriminated from other alleles using this SNP. Other CYP2D6*2 subvariants, however, lack this SNP, and other polymorphic loci may have to be exploited for ASXL-PCR. For all other primer pairs, including -740C>T (Figure 1C), specific amplification was achieved for only one of the forward primers. Figure 1D shows the respective SNP positions that can be exploited to discriminate among CYP2D6*1, *2, and *4 allelic variants. For instance, primers -2609A>C and -2421T>C can be used for amplifying the CYP2D6*4 allele from a CYP2D6*1/*4 sample, whereas -2523G>A, -2178G>A, -1426C>T, and -1000G>A can be used for amplifying the CYP2D6*1 allele. AS amplification was confirmed by genotyping and/or sequence analysis (data not shown). The specificity of each primer was tested on at least three DNA samples of known genotype.

Figure 1.

Principle and optimization of allele-specific amplification combined with long-range (ASXL)-PCR. A: The sequence context of the -1584C>G single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (black; SNP is in bold). Primer sequences amplifying either -1584C or -1584G are shown in gray, with matching and mismatching nucleotides at their respective -3′ ends in black and bold. The arrow indicates that a perfectly matching primer is extended; primers with mismatches are not extended, as indicated by an X in the arrow. B: Summary of SNP positions that can be utilized to discriminate CYP2D6*1, *2A, and *4 alleles. SNP positions are shown in reference to AY545216 (+1 = A in the ATG translation start codon). The nucleotide for which AS amplification was achieved is in bold. Gray boxes denote the primers designed based on sequence information for that allele and the alleles that will be amplified with a given AS primer. For example, the CYP2D6*1 and *4 alleles can be separated utilizing positions -2609 (amplifies *4), -2523 (amplifies *1), -2421 (amplifies *4), -2178 (amplifies *1), -1426 (amplifies *1), and -1000 (amplifies *1). CYP2D6*1/*1 and *2A/*2A gDNA samples were amplified with primer -1584C>G (C). The -1584C>G primer amplified a 6358-bp fragment from the CYP2D6*1 (-1584C), but not the CYP2D6*2A (-1584G) allele. D: Real-time ASXL-PCR with primer -740C>T amplifies from the CYP2D6*4 allele (-740C) but not the *1 allele (-740T). Nucleotides providing AS amplification are underlined. var, variant; wt, wild type.

Application of ASXL-PCR To Resolve Genotype Discord within a Pedigree

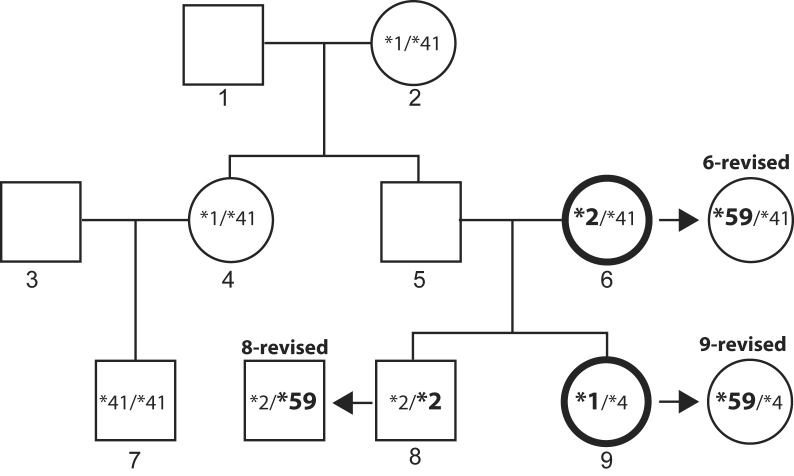

We reevaluated the genotype results of a six-member family of European descent in which the original genotype calls were discordant with the known biological relationship between a mother/daughter pair. (Certain allelic variants of CYP2D6 are only, or predominantly, present in certain populations/ethnicities. For completeness, the ethnicity of the studied family is therefore indicated.) The sample from the mother (subject 6) was genotyped as CYP2D6*2/*41 and did not share any alleles with the sample from her daughter (subject 9), which was genotyped as CYP2D6*1/*4 (Figure 2). Notably, samples from both subjects were heterozygous for -1584, which was expected in the mother (genotyped as CYP2D6*2/*41), but not the daughter (genotyped as CYP2D6*1/*4). This SNP is found on almost all CYP2D6*2 alleles in whites, subtyping the allele as CYP2D6*2A, but rarely on CYP2D6*1 or *4 alleles. Regardless, this SNP allowed us to generate ASXL-PCR fragments for separate analysis of both alleles by genotyping and sequencing samples from both subjects. The allele amplified using the -1584C primer revealed SNPs that were consistent with the presence of a CYP2D6*41 allele in the mother and a CYP2D6*4 allele in the daughter. The allele amplified using the -1584G primer genotyped positive for 2850C>T, which was compatible with the mother's CYP2D6*2A assignment. However, discordant results for the 2850C>T SNP were obtained in the daughter's sample, depending on whether the template for subsequent 2850C>T genotype was the -1584G ASXL-PCR product (2850T detected) or the XL-PCR fragment A containing products from both chromosomes (no 2850T detected). The inability to detect the 2850T allele using the fragment A template resulted in a default CYP2D6*1 allele assignment and was consistent with the genotype obtained directly on gDNA. In addition, sample mix-up as a source of genotype discord was ruled out by repetition of the genotype analysis on freshly isolated DNA samples from each subject.

Figure 2.

Pedigree of a family with initial genotype discord. The genotypes of subjects 6 and 9, mother and daughter, shown with bold circles, were discordant when originally tested. The son's (subject 8) genotype was initially not discordant. Revised genotypes for subjects 6, 8, and 9 containing a CYP2D6*59 allele are indicated with an arrow. Alleles revised are shown in bold and larger font.

Against expectations, sequence analysis of heterozygous fragment A XL-PCR products and ASXL-PCR products did not reveal any novel SNPs that could explain the failure of the TaqMan assay to detect 2850C>T in the samples from the daughter. We did, however, find that samples from both the mother and daughter also carried 2291G>A and 2939G>A. In agreement with the Nomenclature Database, these CYP2D6*59 signature SNPs were both located on the same allele as 2850C>T. Supplemental Figure S1 shows sequencing results for the 2850C>T and 2939G>A SNP positions on the heterozygous fragment A template and the sequence traces for the CYP2D6*4 and *59 ASXL-PCR products. Because 2850C>T, 2291G>A, and 2939G>A were on the allele generated with the -1584G primer, we also mapped the -1584C>G SNP to CYP2D6*59.

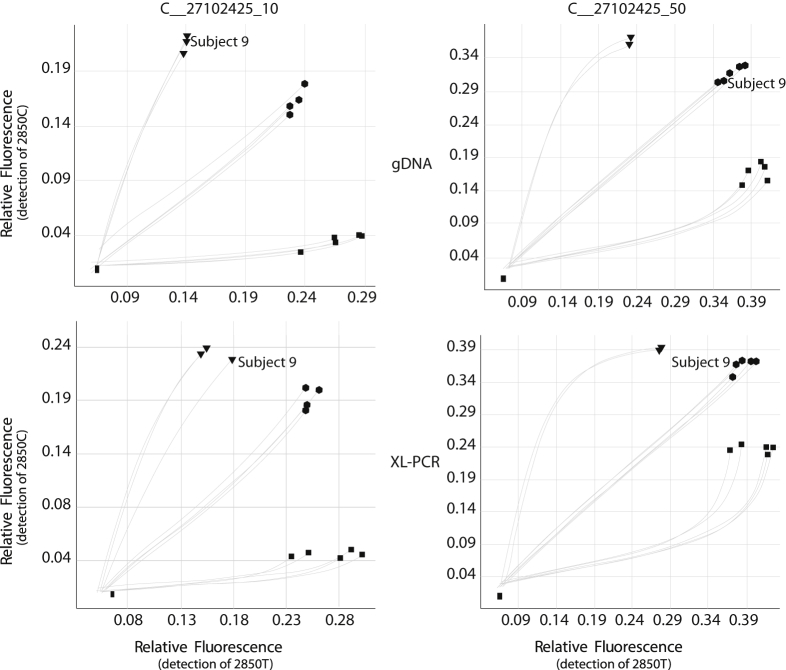

Although TaqMan genotyping and sequencing ASXL-PCR products allowed us to resolve the initial inconsistent genotype calls and to revise the daughter's genotype (Figure 2), we could not explain the initial failure to detect the 2850C>T SNP in this subject's sample. Thermo Fisher was consulted (Toinette Hartshorne, personal communication), but no known SNPs that directly interfered with TaqMan assay primer or probe binding were identified. Thermo Fisher designed and provided, at no cost, an alternate assay for 2850C>T detection that uses a different binding site for one of the PCR primers. This assay returned calls that were in agreement with the results obtained by sequencing ASXL-PCR products. Scatterplots for the initial and alternate assays performed on gDNA and XL-PCR (heterozygous fragment A) are provided in Figure 3. The CYP2D6*59 tagSNP (3027G>A) was also present in another descendant (Figure 2). Ultimately, genotype assignments were revised for all three subjects.

Figure 3.

TaqMan (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) cluster plots with the original (C__27102425_10) and alternate (C__27102425_50) assays for 2850C>T (rs16947). The x and y axes show relative fluorescence for 2850T (variant) and 2850C (wild type), respectively. Clusters are shown with trajectory lines. Pedigree subject 9 clusters with other homozygous wild-type samples (2850C/C) with the initial assay (C__27102425_10) while clustering with heterozygous samples (2850C/T) when run with the alternate assay (C__27102425_50). The homozygous variant cluster (2850T/T) is also shown. gDNA, genomic DNA; XL-PCR, long-range PCR.

Our genotype data also revealed that -1584C>G is a component of the CYP2D6*59 haplotype, as the SNP was consistently found in samples from all three subjects who carried this allele. A 5302-bp sequence containing all introns and exons and 675 and 248 bp of upstream and downstream sequences, respectively, was deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore; GenBank accession number KR005632).

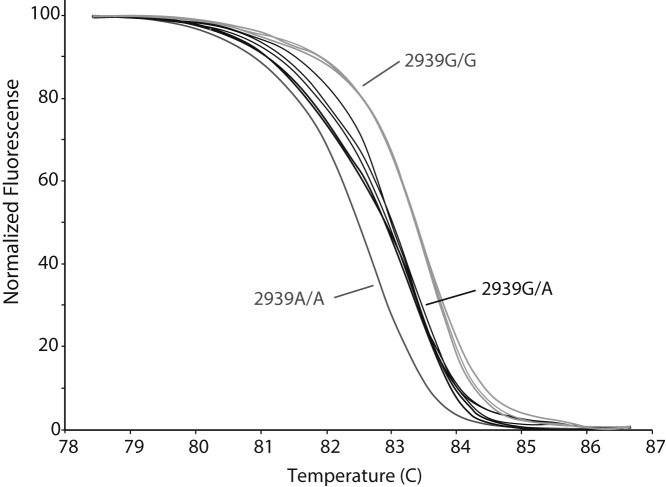

Because a TaqMan assay for screening for either CYP2D6*59 tagSNP (2291G>A or 2939G>A) is not commercially available, we designed and evaluated a high-resolution melt analysis assay for 2939G>A to repeat genotyping in samples from subjects in other studies (unpublished data). This SNP was chosen over 2291G>A because it has been shown to be the SNP involved in reducing mRNA expression levels.25 Figure 4 shows the melt curves, differentiating samples with different genotypes. Using this assay, we identified heterozygous samples from two Caucasian subjects among an ethnically diverse population of 189 subjects (89 Caucasian, 80 African American, 20 mixed ethnicities). The original CYP2D6*1/*4 and *2/*2 genotype assignments were revised to CYP2D6*4/*59 and *2/*59. The corresponding dextromethorphan/dextrorphan urinary metabolic ratios, 0.165 and 0.024, were consistent with intermediate and extensive metabolizer phenotypes, reflecting activity scores of 0.5 and 1.5, respectively, using cutoff values as described by Gaedigk et al.26

Figure 4.

Normalized high-resolution melt curve analysis of the CYP2D6*59 2939G>A tag single-nucleotide polymorphism. Curves represent individuals with 2939G/G, 2939G/A, and 2939A/A genotypes, as indicated. The assay was performed on long-range PCR templates.

Application of ASXL-PCR To Characterize Complex Gene Duplications

In some cases, gene duplications/multiplications may occur on both chromosomes, or one chromosome carries a duplication/multiplication and the other, a tandem gene arrangement. In such scenarios, ASXL amplification may considerably simplify allele characterization. The case we are describing here is detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Overview of a complex CYP2D6 genotype that was resolved using allele-specific long-range PCR. The graph displays the two allelic variants of the subject. CYP2D6, 2D7, and 2D8 are shown in different gray shades. REP denotes repetitive sequences located downstream of CYP2D6 and 2D7. REP-DUP refers to the REP sequence found downstream of a duplicated gene. REP7 is interrupted from common downstream sequences (dark-gray boxes) by a 1.6-Kb region, referred to as spacer. Extra-long PCR fragments are shown as lines under the genes that support their amplification; the X indicates that this fragment was not generated from this gene copy. The hatched line for fragment D indicates that amplification from the CYP2D6*4 allele was poor due to more efficient amplification from the CYP2D6*2 allele. Exon 1 (ex1) and intron 6 (in6) denote the regions amplified by quantitative PCR to determine gene copy number (regions in intron 5 and exon 9 that were also assessed are not shown).

The subject's genotype was determined by a commercial entity that offers clinical genotyping services as CYP2D6*2/*4 and duplication-positive. However, because the test did not determine which of the two alleles carried the duplication event, the patient's phenotype could not be predicted with certainty. To map the duplication, we amplified fragment D (Table 1), that is, an XL-PCR product encompassing the entire duplicated gene. This fragment genotyped as CYP2D6*2, indicating that a gene duplication or multiplication is located on the CYP2D6*2 allele. Quantitative copy number variation analysis, however, determined four copies probing the exon 1, intron 5, and intron 6 regions, but only three copies for the exon 9 region. We therefore suspected that the CYP2D6*4 allele also carried a duplication that was not detected via amplification and genotyping fragment D. XL-PCR was then performed to generate fragment D in an AS manner using primer -740C>T (amplifying CYP2D6*4 but not CYP2D6*2; Figures 1D and 5). The resulting amplicon had SNPs at positions 100C>T and 1846G>A and was positive for a CYP2D7-derived exon 9 (also referred to as exon 9 conversion); these results suggested the presence of a CYP2D6*4N subvariant within the duplication structure. This assignment was also supported by the finding that fragment D was about 1.6 Kb longer compared with that amplified from a CYP2D6*2x2 (the length difference is due to CYP2D7 extending downstream and containing a so-called spacer region that is absent in CYP2D6).21 When fragment D was amplified in a non-AS manner, the shorter CYP2D6*2x2-derived product was preferentially amplified, leading to a dropout of the CYP2D6*4N-derived amplicon, which explains why the latter was initially not detected. Because the exon 9 conversion was not found on fragment A, the duplication was subtyped as a CYP2D6*4N+*4 tandem structure, as depicted in Figure 5. The patient's genotype was revised to CYP2D6*2x2/*4N+*4, which predicted extensive metabolism.

Discussion

We have successfully designed and evaluated a set of primers that support the use of ASXL-PCR for generating fragments that encompass the entire CYP2D6 gene, including upstream and downstream flanking regions. In addition to reporting on the design of ASXL-PCR, we further demonstrate the utility of this method in practice through the resolution of discordant genotype results in a pedigree and through the characterization of gene duplications located on both chromosomes of a clinical case. We have also successfully applied ASXL-PCR to resolve another clinical case with a complex CYP2D6 genotype that repeatedly resulted in no-calls when tested with the AmpliChip27 and to resolve a TaqMan CYP2D6*17 assay conundrum.28 The CYP2D6 gene is relatively easily resequenced by generating a XL-PCR product that encompasses the entire gene and subsequent sequence analysis. However, this approach reveals only sequence variations and does not inform phasing and haplotype structure, except in situations in which the allele of interest is paired with the CYP2D6*5 deletion allele or CYP2D6*13 (CYP2D7-2D6 hybrid structures) in which the desired allele is the only one amplified. We have utilized a XL-PCR TOPO cloning kit (Life Technologies) to separate alleles and analyze the chromosomes separately,16, 18, 19, 20 but this approach was time consuming and often not efficient. Also, multiple clones needed to be analyzed to ensure that sequence variation(s) were not due to errors introduced by PCR. To minimize the risk for PCR errors, we performed ASXL-PCR in triplicate reactions and pooled the amplicons for sequence analysis.

Regarding the design of ASXL-PCR amplification, we successfully achieved AS amplification when targeting C>A, C>T, G>A, G>T, and C>G SNPs (Table 1). Primers with A or T at their 3′ ends did not, or did not sufficiently, discriminate between alleles under the conditions used. Specificity of these primers may be improved, however, by introducing penultimate bases to minimize amplification from the undesired allele.29 Although we utilized SNPs in the upstream region for designing AS forward primers, SNPs in the downstream region could certainly also be exploited for generating AS reverse primers. To achieve AS amplification from alleles containing A or T, using AS forward and reverse primers may also be an option to be explored.

ASXL-PCR in conjunction with sequencing allowed us to quickly resolve genotype discord within a pedigree that was caused by the presence of CYP2D6*59, specifically the 2939G>A SNP. This SNP interfered with the TaqMan assay that detected 2850C>T, such that the SNP was not detected under conventional assay conditions. Failure to detect 2850C>T led to a CYP2D6*1 allele assignment that was inconsistent with the genotype determined in the sample from the mother, pedigree subject 6 (Figure 2). We speculate that PCR amplification in pedigree subject 9 was more efficient for the allele carrying 2850C and 2939G (CYP2D6*4) compared with the allele carrying 2850T and 2939A (CYP2D6*59), causing allele dropout in the TaqMan assay that tested for 2850C>T and consequently clustered as wild type (Figure 3). In other words, the assay is detecting fluorescence derived only from the CYP2D6*4 allele and hence clusters the sample from pedigree subject 9 as wild-type 2850C. An alternate TaqMan assay provided by Thermo Fisher corrected the allele-dropout phenomenon and correctly genotyped the sample from pedigree subject 9 as 2850C/T heterozygous (Figure 3). We recently described a similar dropout phenomenon that affected the CYP2D6*17 TaqMan assay.28 In this instance, amplification of CYP2D6*17 outperformed that of CYP2D6*4, causing homozygous results for the SNP at position 1023 in a subset of CYP2D6*4/*17 samples. In this scenario, the allele-dropout phenomenon was also resolved by redesigning the CYP2D6*17 assay.

On discovery of the CYP2D6*59 allele in a pedigree within our repository, we screened samples from an ethnically diverse population of 189 subjects for CYP2D6*59 with a newly developed high resolution melt assay and identified heterozygous samples from two subjects, a pair of siblings of Caucasian ancestry. Toscano et al25 described a considerable reduction in activity for the CYP2D6*59 variant due to decreased mRNA expression levels. Reduced function is consistent with the urinary metabolic ratio of dextromethorphan/dextrorphan of 0.165 measured in the sample from subject 9. Because this subject carries the CYP2D6*59 variant in combination with a nonfunctional CYP2D6*4, metabolic capacity is mediated by CYP2D6*59 only and hence determines the activity of only this allele. The sample from the second subject, genotyped as CYP2D6*2/*59, had a dextromethorphan/dextrorphan ratio in the extensive metabolizer range, as was expected due to the presence of a functional CYP2D6*2.

Notably, the original TaqMan assay that detected 2850C>T did not cause any other genotype miscalls that might have interfered with the accuracy of allele assignment. Also, the alternate assay for 2850C>T is currently available as a custom TaqMan SNP assay (Supplemental Table S1) and avoids assay interference in the presence of CYP2D6*59. The CYP2D6*59 allele also appears to be relatively rare, with a frequency of 0.65% previously reported in a sample of Caucasians25 and 0.5% in our cohort of 89 Caucasians. Considering allele frequencies of about 20% and 0.5% for CYP2D6*4 and *59, respectively,30 about 1/1000 subjects would have been assigned a CYP2D6*1/*4 genotype instead of a CYP2D6*2/*4 genotype (with the original TaqMan assay and in the absence of testing for CYP2D6*59). Currently, CYP2D6*1 and *2 are both considered to be functional alleles10, 11 and thus not to affect phenotype prediction. However, to accurately predict a patient's phenotype, the inclusion of CYP2D6*59 in test panels might be considered.

We selected SNPs for allelic discrimination based on current allele definitions and knowledge. It needs to be noted, however, that information on SNPs in the upstream regions of all defined alleles is not available from the Nomenclature Database at this time. Although the SNPs we targeted appeared to have been in linkage disequilibrium with certain CYP2D6 haplotypes, this may not necessarily always be the case considering the highly polymorphic nature of this gene locus within and across populations.12 It may be prudent to obtain genotype and/or sequence information first to guide primer choice for ASXL-PCR. In cases in which SNP information is not available or SNP linkage/haplotypes are unknown or questionable, the generation of a series of ASXL-PCR products will likely capture both alleles for subsequent characterization.

In summary, ASXL-PCR facilitates the characterization of allelic variants, as demonstrated for the highly polymorphic CYP2D6 gene locus. In cases in which haplotype information is of the essence, sequencing or genotype analysis of ASXL-PCR fragments is a time-saving and simple approach to investigating regions that may well exceed 10 Kb, the longest product we have generated thus far. This strategy is also not limited to CYP2D6; it can be applied to virtually any region of interest as long as sequence variations that can be exploited for primer design are known.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Toinette Hartshorne (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for personal communication and for critically reading the manuscript and Dr. Roger Gaedigk (Children's Mercy, Kansas City, MO) for support with artwork.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Development grant R01 HD058556-05 (J.S.L.) and discretionary funding from the Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Toxiology, and Therapeutic Innovation, Children's Mercy (Kansas City, MO).

Disclosures: The authors received an alternate TaqMan genotyping assay at no cost from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.06.007.

Supplemental Data

Sequence analysis of a subject with a CYP2D6*4/*59 genotype. Amplicons were generated with the universal fragment A primers amplifying both alleles and with allele-specific amplification combined with long-range (ASXL)-PCR amplifying the CYP2D6*4 and *59 alleles separately. A–C: Sequence traces for single-nucleotide polymorphism 2850C>T (column 1) and 2939G>A (column 2), for heterozygous template (fragment A) (A), ASXL-generated CYP2D6*4 template (B), and ASXL-generated CYP2D6*59 template (C).

References

- 1.Zhou S.F. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: part I. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:689–723. doi: 10.2165/11318030-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou S.F. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: part II. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:761–804. doi: 10.2165/11318070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim S.C., Ingelman-Sundberg M. Update on Allele Nomenclature for Human Cytochromes P450 and the Human Cytochrome P450 Allele (CYP-Allele) Nomenclature Database. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;987:251–259. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-321-3_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teh L.K., Bertilsson L. Pharmacogenomics of CYP2D6: molecular genetics, interethnic differences and clinical importance. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012;27:55–67. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-rv-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanger U.M., Raimundo S., Eichelbaum M. Cytochrome P450 2D6: overview and update on pharmacology, genetics, biochemistry. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:23–37. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanger U.M., Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanger U.M., Turpeinen M., Klein K., Schwab M. Functional pharmacogenetics/genomics of human cytochromes P450 involved in drug biotransformation. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;392:1093–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller D.J., Kekin I., Kao A.C., Brandl E.J. Towards the implementation of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes in clinical practice: update and report from a pharmacogenetic service clinic. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25:554–571. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.838944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner K.R., Brennan F.X., Scott R., Lombard J. The potential utility of pharmacogenetic testing in psychiatry. Psychiatry J. 2014;2014:730956. doi: 10.1155/2014/730956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews K.R., Gaedigk A., Dunnenberger H.M., Leeder J.S., Klein T.E., Caudle K.E., Haidar C.E., Shen D.D., Callaghan J.T., Sadhasivam S., Prows C.A., Kharasch E.D., Skaar T.C. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95:376–382. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hicks J.K., Swen J.J., Thorn C.F., Sangkuhl K., Kharasch E.D., Ellingrod V.L., Skaar T.C., Muller D.J., Gaedigk A., Stingl J.C., Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:402–408. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaedigk A. Complexities of CYP2D6 gene analysis and interpretation. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25:534–553. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.825581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks J.K., Swen J.J., Gaedigk A. Challenges in CYP2D6 phenotype assignment from genotype data: a critical assessment and call for standardization. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15:218–235. doi: 10.2174/1389200215666140202215316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaedigk A., Bradford L.D., Alander S.W., Leeder J.S. CYP2D6*36 gene arrangements within the CYP2D6 locus: association of CYP2D6*36 with poor metabolizer status. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:563–569. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott S.A., Tan Q., Baber U., Yang Y., Martis S., Bander J., Kornreich R., Hulot J.S., Desnick R.J. An allele-specific PCR system for rapid detection and discrimination of the CYP2C19 *4A, *4B, and *17 alleles: implications for clopidogrel response testing. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaedigk A., Ndjountche L., Gaedigk R., Leeder J.S., Bradford L.D. Discovery of a novel nonfunctional cytochrome P450 2D6 allele, CYP2D*42, in African American subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:575–576. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaedigk A., Bhathena A., Ndjountche L., Pearce R.E., Abdel-Rahman S.M., Alander S.W., Bradford L.D., Rogan P.K., Leeder J.S. Identification and characterization of novel sequence variations in the cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) gene in African Americans. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:173–182. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaedigk A., Eklund J.D., Pearce R.E., Leeder J.S., Alander S.W., Phillips M.S., Bradford L.D., Kennedy M.J. Identification and characterization of CYP2D6*56B, an allele associated with the poor metabolizer phenotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:817–820. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaedigk A., Isidoro-Garcia M., Pearce R.E., Sanchez S., Garcia-Solaesa V., Lorenzo-Romo C., Gonzalez-Tejera G., Corey S. Discovery of the nonfunctional CYP2D6*31 allele in Spanish, Puerto Rican, and US Hispanic populations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:859–864. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0831-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaedigk A., Frank D., Fuhr U. Identification of a novel non-functional CYP2D6 allele, CYP2D6*69, in a Caucasian poor metabolizer individual. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:97–100. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaedigk A., Ndjountche L., Divakaran K., Dianne Bradford L., Zineh I., Oberlander T.F., Brousseau D.C., McCarver D.G., Johnson J.A., Alander S.W., Wayne Riggs K., Steven Leeder J. Cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) gene locus heterogeneity: characterization of gene duplication events. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:242–251. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaedigk A., Montane Jaime L.K., Bertino J.S., Jr., Berard A., Pratt V.M., Bradfordand L.D., Leeder J.S. Identification of novel CYP2D7-2D6 hybrids: non-functional and functional variants. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:121. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2010.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaedigk A., Fuhr U., Johnson C., Berard L.A., Bradford D., Leeder J.S. CYP2D7-2D6 hybrid tandems: identification of novel CYP2D6 duplication arrangements and implications for phenotype prediction. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:43–53. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaedigk A., Twist G.P., Leeder J.S. CYP2D6, SULT1A1 and UGT2B17 copy number variation: quantitative detection by multiplex PCR. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:91–111. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toscano C., Raimundo S., Klein K., Eichelbaum M., Schwab M., Zanger U.M. A silent mutation (2939G>A, exon 6; CYP2D6*59) leading to impaired expression and function of CYP2D6. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:767–770. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000236331.03681.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaedigk A., Simon S.D., Pearce R.E., Bradford L.D., Kennedy M.J., Leeder J.S. The CYP2D6 activity score: translating genotype information into a qualitative measure of phenotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:234–242. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaedigk A., Garcia-Ribera C., Jeong H.E., Shin J.G., Hernandez-Sanchez J.T. Resolution of a clinical AmpliChip CYP450 Test no call: discovery and characterization of novel CYP2D6*1 haplotypes. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1175–1184. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaedigk A., Freeman N., Hartshorne T., Riffel A.K., Irwin D., Bishop J.R., Stein M.A., Newcorn J.H., Jaime L.K.M., Cherner M., Leeder J.S. SNP genotyping using TaqMan® technology: the CYP2D6*17 assay conundrum. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9257. doi: 10.1038/srep09257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadhouders R., Pas S.D., Anber J., Voermans J., Mes T.H.M., Schutten M. The effect of primer-template mismatches on the detection and quantification of nucleic acids using the 5′ nuclease assay. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:109–117. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hicks J.K., Bishop J.R., Sangkuhl K., Muller D.J., Ji Y., Leckband S.G., Leeder J.S., Graham R.L., Chiulli D.L., LLerena A., Skaar T.C., Scott S.A., Stingl J.C., Klein T.E., Caudle K.E., Gaedigk A. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guildeline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98:127–134. doi: 10.1002/cpt.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence analysis of a subject with a CYP2D6*4/*59 genotype. Amplicons were generated with the universal fragment A primers amplifying both alleles and with allele-specific amplification combined with long-range (ASXL)-PCR amplifying the CYP2D6*4 and *59 alleles separately. A–C: Sequence traces for single-nucleotide polymorphism 2850C>T (column 1) and 2939G>A (column 2), for heterozygous template (fragment A) (A), ASXL-generated CYP2D6*4 template (B), and ASXL-generated CYP2D6*59 template (C).