Abstract

Vibration-reducing (VR) gloves have been used to reduce the hand-transmitted vibration exposures from machines and powered hand tools but their effectiveness remains unclear, especially for finger protection. The objectives of this study are to determine whether VR gloves can attenuate the vibration transmitted to the fingers and to enhance the understanding of the mechanisms of how these gloves work. Seven adult male subjects participated in the experiment. The fixed factors evaluated include hand force (four levels), glove condition (gel-filled, air bladder, no gloves), and location of the finger vibration measurement. A 3-D laser vibrometer was used to measure the vibrations on the fingers with and without wearing a glove on a 3-D hand-arm vibration test system. This study finds that the effect of VR gloves on the finger vibration depends on not only the gloves but also their influence on the distribution of the finger contact stiffness and the grip effort. As a result, the gloves increase the vibration in the fingertip area but marginally reduce the vibration in the proximal area at some frequencies below 100 Hz. On average, the gloves reduce the vibration of the entire fingers by less than 3% at frequencies below 80 Hz but increase at frequencies from 80 to 400 Hz. At higher frequencies, the gel-filled glove is more effective at reducing the finger vibration than the air bladder-filled glove. The implications of these findings are discussed.

Relevance to industry

Prolonged, intensive exposure to hand-transmitted vibration can cause hand-arm vibration syndrome. Vibration-reducing gloves have been used as an alternative approach to reduce the vibration exposure. However, their effectiveness for reducing finger-transmitted vibrations remains unclear. This study enhanced the understanding of the glove effects on finger vibration and provided useful information on the effectiveness of typical VR gloves at reducing the vibration transmitted to the fingers. The new results and knowledge can be used to help select appropriate gloves for the operations of powered hand tools, to help perform risk assessment of the vibration exposure, and to help design better VR gloves.

Keywords: Finger vibration, Anti-vibration glove, Vibration-reducing glove, Hand-arm vibration, Hand-transmitted vibration

1. Introduction

Prolonged, intensive exposure to hand-transmitted vibration is associated with hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS). Some vibration-reducing gloves have been developed and applied to attenuate the vibration transmitted to the hand-arm system (Rens et al., 1987; Goel and Rim, 1987; Reynolds and Jetzer, 1998). The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has set forth a standard for the testing and assessment of such gloves (ISO 10819, 1996). While a few studies reported that some of these gloves could be helpful (Brown, 1990; Jetzer et al., 2003; Mahbub et al., 2007), there is some doubt as to their usefulness for attenuating the vibration transmitted to the fingers (Griffin 1990; 1998; Paddan and Griffin, 2001; Dong et al., 2009). Also as a major concern, these gloves can substantially reduce the finger dexterity and increase handgrip effort (Wimer et al., 2010). As a result, some VR gloves may not be comfortable to wear and may cause hand fatigue. In the worst case, they could become one of the factors resulting in hand injuries due to overexertion or the cause of safety concerns such as loss of dexterity. Although wearing a glove when operating a tool is generally recommended for many good reasons, a VR glove may not be the best choice if its benefits from vibration reduction do not outweigh its adverse effects. The balance is likely to be tool-specific and working condition- or task-specific. To help determine the balance, it is important to find how much vibration the gloves can reduce. While many studies have investigated the vibration transmissibility of these gloves at the palm of the hand, the current study focused the examination on the glove transmissibility at the fingers.

Because vibration-induced finger injuries and disorders are the major components of HAVS (Griffin, 1990), the fingers are critical substructures in the hand-arm system. The assessment of VR gloves should be partially based on the level of vibration reduction at the fingers. Largely because of technical challenges, the study of the vibration transmissibility of the VR gloves at the fingers has been very limited (Griffin et al., 1982; Paddan and Griffin, 2001). Probably for the same reason, the standardized anti-vibration glove test is based on the vibration transmissibility of the glove at the palm of a hand along the forearm direction (ISO 10819, 19969, 2013) rather than that at the fingers. However, this standard does indirectly attempt to address the issue of finger vibration attenuation. This is reflected by one of the three criteria for defining anti-vibration gloves. This criterion requires that any anti-vibration glove must be a full-finger glove with the same materials and thickness at the palm and the fingers in the original standard (ISO 10819, 1996). The primary assumption is that if the palm and fingers are covered as per the specification, the glove can similarly reduce vibration transmitted to the palm and fingers; at least, such a glove should be better at attenuating the finger vibration than one that does not meet this criterion. While this assumption has not been sufficiently proven and is questionable, this criterion has a practical problem: the anti-vibration gloves that meet it are usually too bulky to wear. As a result, no glove manufacturer has actually fully implemented this criterion, although some gloves available on the market have been certified as anti-vibration gloves. To allow these gloves to fully comply with the criterion, the requirement in the revised version of the standard has been revised (ISO 10819, 2013); specifically, the thickness of the glove fingers has been relaxed from 100% to ≥55% of that at the palm of the glove. Obviously, this revision is not based on the finger vibration attenuation of the gloves but it simply accommodates reality.

Vibration-reducing gloves basically serve as a passive cushion between a hand and a tool at their interface to reduce the transmitted vibration, similar to the function of a suspension system (Dong et al., 2009). Like any passive suspension system, the vibration isolation effectiveness of the glove depends not only on the glove dynamic properties but also on the effective mass of the glove-hand-arm system. Because the effective mass distributed at the palm along the forearm direction is generally the highest for a given exposure condition, the glove is theoretically most effective at reducing the vibration transmitted to the palm in that direction (Dong et al., 2012). This means that the transmissibility measured with the standardized test method generally represents the best case for the vibration reduction capabilities of the glove, as confirmed in a recent study (McDowell et al., 2013). Its effectiveness could be overestimated if this transmissibility value is used for the assessment. Because the effective mass of each finger is small in comparison to that of the palm, the glove is likely only capable of minimal attenuation at the fingers, especially at the fingertips. Once the vibration transmissibility of the gloves at the fingers is reliably measured, the overall effectiveness of the glove for vibration attenuation can be better estimated.

One of the methods to measure the vibration transmissibility of the glove fingers is to insert a finger adapter equipped with a miniature tri-axial accelerometer between the fingers and the glove material, similar to the palm-adapter method used in the standardized glove test (ISO 10819, 19969, 2013). Because the mass and dimensions of each finger are relatively small, compared with the possible mass and dimensions of the finger adapter, the finger adapter equipped with a conventional miniature accelerometer could change the original coupling relationship; as a result, the measured transmissibility may not be sufficiently representative of the actual transmissibility of the glove fingers. Furthermore, the finger vibration transmissibility could vary greatly at different locations on each finger (Welcome et al., 2011). Therefore it is difficult to use the finger adapter method to reliably measure the transmissibility distribution.

Alternatively, the glove finger transmissibility can be indirectly estimated by measuring the vibrations on the fingers with and without wearing the anti-vibration gloves (Griffin et al., 1982; Cheng et al., 1999; Paddan and Griffin, 2001). A modeling study demonstrated that the transmissibility estimated using this relative method is acceptable to approximately represent that at the glove finger interface (Dong et al., 2009). The major concern of this on-the-finger method is similar to that of the adapter method: the mass of the accelerometer and its fixture may significantly affect the finger vibration. In addition, the installation of the accelerometer on a finger may also apply some artificial constraints to the finger and interact with and influence its dynamic properties, which may also render the measurement unreliable. These problems can be avoided by using a laser vibrometer in the measurement. While the use of a single-direction laser vibrometer for the measurement of hand vibration transmission has been reported by several researchers (Sörensson and Lundström, 1992; Rossi and Tomasini, 1995; Nataletti et al., 2005; Scalise et al., 2007; Concettoni and Griffin, 2009; Xu et al., 2011), a 3-D vibrometer has also been recently used to measure the vibration transmitted to the hand-arm system (Welcome et al., 2011). This technique has made it possible to conduct reliable 3-D measurement of the finger vibration for examining the effectiveness of the gloves for finger vibration exposure protection.

Based on these backgrounds, the objectives of this study are to determine whether the anti-vibration gloves defined by the criteria in the new version of the ISO standard (ISO 10819, 2013) can reduce the vibration transmitted to the fingers and to enhance the understanding of the mechanisms of these gloves. Specifically, the vibration transmissibility spectra of the human fingers with and without wearing a glove were measured in three orthogonal directions using a 3-D laser vibrometer on a 3-D hand-arm vibration test system. Two typical vibration-reducing glove types are considered in the experiment under several different grip forces. The experimental results are used to evaluate the effectiveness of these gloves for reducing the vibration transmitted to the fingers. To help understand the mechanisms of the glove effects, the role of the grip force in the finger transmissibility is also examined.

2. Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

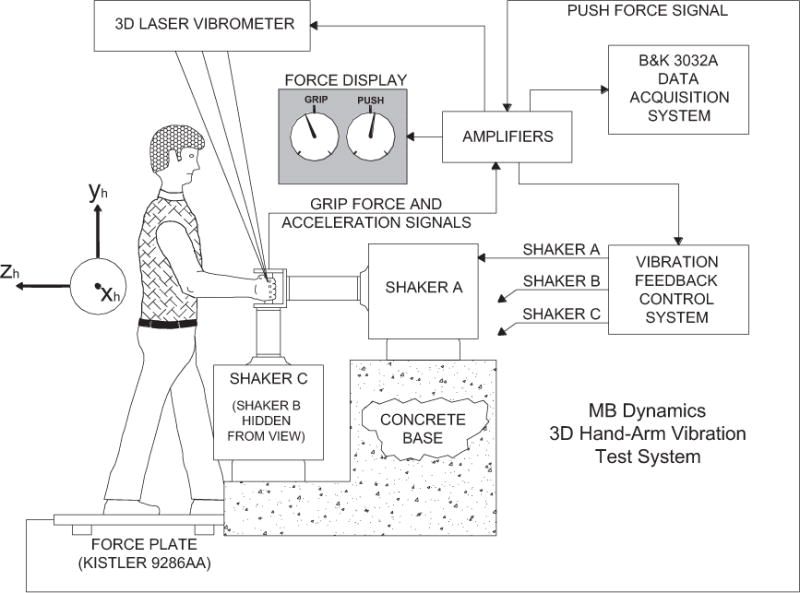

Fig. 1 shows a layout of the basic instrumentation and the subject posture used in this study. Fig. 2 shows a pictorial view of the experimental setup. A 3-D vibration test system (MB Dynamics, 3-D Hand-Arm Vibration Test System) was employed to generate the required vibration spectrum in each of the three directions: Zh is along the forearm; Yh is along the centerline of the instrumented handle in the vertical direction; and Xh is the direction normal to the Yh–Zh plane. An instrumented handle equipped with a tri-axial accelerometer (Endevco, 65–100) and a pair of force sensors (Interface, SML-50) were used to measure the 3-D accelerations and applied grip force. To assure a good signal, a retro-reflective tape was wrapped on the handle. A force plate (Kistler 9286AA) was used to measure the push force applied to the handle. The applied grip and push forces were displayed on two virtual dial gages on a computer monitor in front of the subject, as also shown in Fig. 1. A 3-D scanning laser vibrometer (Polytec, 3-D PSV-400) was used to measure the distributed 3-D vibrations on the surface of the instrumented handle and on the dorsal skin of the fingers. The measured vibration signals were input to the data acquisition system of the laser vibrometer for evaluating the vibration transmissibility.

Fig.1.

Subject and measurement setup that includes a 3-D closed-loop controlled vibration exposure system, a 3-D laser vibrometer, a vibration and response measurement system, a grip force measurement and display system, and a push force measurement and display system.

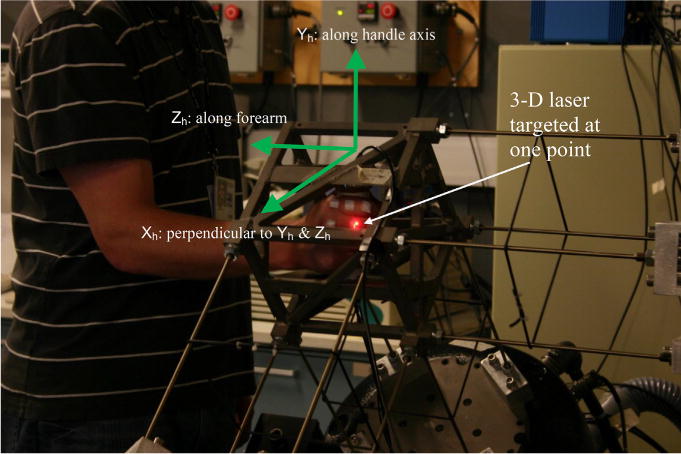

Fig. 2.

A pictorial view of the coordinate system, the subject posture in the experiment, the instrumented handle, and its fixture on the 3-D hand-arm vibration test system.

2.2. Measurement conditions and variables

Seven healthy adult males participated in the experiment with informed consent. Their major anthropometrics are listed in Table 1. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the NIOSH Human Subjects Review Board.

Table 1.

Subject anthropometry (hand length = tip middle finger to crease at wrist; hand breadth = width measured at metacarpals; circumference = circumference measured as specified in EN 420 (2003); hand size based on EN 420 (2003)).

| Subject ID | Height (cm) | Weight(kg) | Hand length (mm) | Hand breadth (mm) | Circumference (mm) | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177.8 | 63.5 | 193 | 87 | 205 | 9 |

| 2 | 176.5 | 79.4 | 195 | 84 | 205 | 9 |

| 3 | 180.3 | 82.2 | 199 | 90 | 215 | 9 |

| 4 | 180.3 | 73.94 | 188 | 87 | 214 | 9 |

| 5 | 182.9 | 88.45 | 195 | 93 | 213 | 9 |

| 6 | 182.9 | 90.26 | 197 | 96 | 234 | 10 |

| 7 | 185.4 | 88.4 | 189 | 89 | 212 | 9 |

| Mean | 180.9 | 80.9 | 193.7 | 89.4 | 214.0 | |

| SD | 3.09 | 9.63 | 4.03 | 4.04 | 9.73 |

As also shown in Fig. 1, the hand and arm postures used in this study were similar to those required in the standardized glove test (ISO 10819,19969, 2013). Specifically, each subject applied a power grip on the instrumented handle with a neutral wrist posture. The forearm was approximately parallel to the floor and aligned with the Zh axis, the elbow angled between 90° and 120°, and shoulder abducted between 0° and 30°. Because the finger biodynamic response is dependent on the applied finger force but largely independent of the remaining part of the hand-arm system (Dong et al., 2005), three grip-only actions (15 N, 30 N, and 50 N) were considered in this study, which are likely to be within the range of the finger forces in the operation of many powered hand tools. In addition, the combined 30 N grip and 50 N push required in the standardized glove test was also considered as one of the four hand actions used in this study.

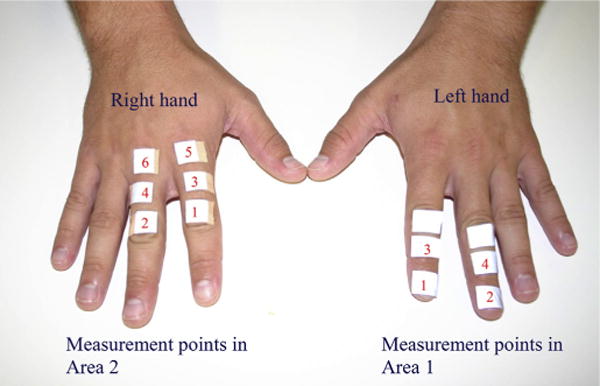

The handle fixture blocked part of the view of the fingers coupled on the handle for a given orientation of the laser vibrometer. The laser vibrometer would have had to be repositioned and realigned several times in the experiment for each subject if we measured the vibration over the full surface of the fingers. This would not only greatly increase the test time and expense but it could also reduce the consistency and reliability of the measurement. To maximize the test efficiency and the reliability of the experimental data, the 3-D laser vibrometer was fixed at an optimized position throughout the entire experiment, and the measurement was performed in the two areas on the index and middle fingers shown in Fig. 3, assuming that the transmissibility on the left and right hands are not significantly different under the same test conditions. Pieces of retro-reflective tape were used in the measurement in order to avoid the effect of hair on the measurement and to maintain good reflection of the laser, which is also shown in Fig. 3. To avoid any adverse effect of the retro-reflective tape on the subject skin, a piece of first-aid adhesive tape was placed between the reflective tape and the skin; this also assured a firm attachment of the reflective tape on the skin.

Fig. 3.

Six points/locations in each of the two measurement areas: Area 1 – fingernail, first knuckle, and middle phalangeal dorsum areas on the index and middle fingers of the left hand; Area 2 – middle knuckle, proximal phalangeal dorsum, and third knuckle areas on the index and middle fingers of the right hand.

To help evaluate the finger criterion of the anti-vibration glove defined in the standard (ISO 10819, 19969, 2013), this study considered two typical models of vibration-reducing gloves: a gelfilled glove (Glove 1) and an air bladder-filled glove (Glove 2), as shown in Fig. 4. The gel-filled glove cannot be classified as an antivibration glove primarily because its high-frequency transmissibility (from 200 to1250 Hz) measured in the standardized test is greater than 0.70 (Welcome et al., 2012), which is higher than that (<0.60) required in the standard. On the other hand, the air bladder-filled glove can be classified as an anti-vibration glove if the relaxed finger thickness criterion is used for the judgment (Welcome et al., 2012). To measure the vibration transmitted through the glove and fingers and reflected off the finger skin, the top part of the glove fingers was cut off, as also shown in Fig. 4. According to the major mechanisms of the VR glove (Dong et al., 2009), the major protection from the gloves comes from the vibration isolation materials between the hand and vibrating surface. The cut does not change the essential dynamic characteristics of these materials. The major effect of the cut is to reduce the constraints of the gloves on the fingers, which may change the finger dynamics. Because the tested VR glove fingers have ample space for each finger, the original glove constraints are actually small. Hence, the cut is unlikely to have substantial effect on the finger transmissibility.

Fig. 4.

Four tested gloves, two for each of the two models: Glove 1 is a gel-filled vibration-reducing glove; Glove 2 is air bladder-filled vibration-reducing glove.

The multi-axis vibration controller of the 3-D hand-arm vibration test system was programmed to generate the same broadband random vibration from 16 to 500 Hz in each vibration direction. The overall root-mean-square value of the unweighted acceleration in each direction was 19.6 m/s2. While the mean coherence of the multi-axis vibrations on powered hand tools is unknown, the coherence for each pair of axes was taken as 0.9 in this study.

2.3. Measurement procedures

Before and after each subject test, the 3-D vibrations distributed on the instrumented handle were measured. The data were used to check the test and measurement systems and to establish the baseline for evaluating the finger vibration transmissibility with and without wearing a glove.

The objectives and testing procedures were explained to each subject upon arrival. After signing the required consent form, the reflective tapes were attached to the measuring points, and the subject was instructed to practice the grip and push actions with the posture shown in Figs.1 and 2. Whenever necessary, the height of the force platform was also adjusted so that the subject could comfortably grip the handle with the required hand and arm postures.

Two consecutive trials of the measurement for each of the 12 test treatments (four hand forces and three glove conditions including bare hand) were performed. While the measurement on four of the subjects started on the right hand, the sequence of the treatments for each hand was randomized. In each trial, the laser vibrometer scanned the defined measurement points sequentially when the subject was comfortable performing the required actions and maintaining the required hand forces. Guided by a researcher, the fingers of each subject with and without wearing a glove were positioned on the handle at similar locations. Partially because of the limitations of the 3-D vibrometer and partially because it was extremely difficult to maintain a stable and precise position of the fingers during the vibration exposure, the three laser beams of the 3-D vibrometer could not be targeted and focused at exactly the same location on each piece of tape. They were controlled within the taped area (≈0.6 cm2). The variable measurement duration for each scanning location was automatically controlled by the vibrometer to achieve sufficient validity of the measurement. The measurement process for each trial took about 1 minute to complete the scanning of the points on each hand. After each trial, the subject rested for about one minute before the next trial. The entire test took about three hours for each subject.

As also shown in Fig. 3, six measuring points were originally designed in each measuring area but only the first four points in Area 1 were fully measured for all the treatments of each subject. This was because some of the 3-D laser beams were blocked by the handle fixture in the treatments of the gloved hand (Fig. 2). The data measured on the four points in Area 1 and those at the six points in Area 2 were used in the evaluation of the finger and glove transmissibility spectra.

2.4. Transmissibility evaluation

In principle, the laser vibrometer directly measures the vibration velocity. It was converted into acceleration by the data acquisition system of the vibrometer. Together with the 3-D accelerations measured with the tri-axial accelerometer installed in the handle, the vibration transmissibility was evaluated using the function built in the software of the vibrometer. A linear average was taken during the measurement duration at each point.

The transmissibility spectrum on the handle surface (TrHandle) approximately at the corresponding measurement locations on the index and middle fingers in each direction (i) was evaluated from:

| (1) |

where AHandle is the handle surface acceleration measured with the laser vibrometer, AExcitation is the excitation acceleration measured using the accelerometer installed in the handle and controlled in the vibration generation, and ω is the vibration frequency in Rad/s. Because it was difficult to determine the exact corresponding points between the handle and the fingers, the average transmissibility spectrum of the six points measured on the handle in the finger contact area was used as the baseline transmissibility spectrum in this study.

The preliminary transmissibility spectrum at each point on the fingers (TrRaw) was evaluated from:

| (2) |

where AFinger is the acceleration measured on the fingers using the laser vibrometer.

These two transmissibility spectra were expressed in an equal frequency band with an increment of 1.25 Hz. After they were measured, the finger transmissibility spectrum at each measuring point in each direction (TrFinger) was evaluated using the following formula:

| (3) |

Because the vibration-reducing gloves can substantially increase the effective grip size and the grip effort (Wimer et al., 2010), the positions and orientations of the measuring points on the fingers relative to the handle may not be exactly the same with and without wearing a glove. This observation suggests that it may not be very reliable to assess the vibration attenuation effectiveness of the glove fingers based on the direction-specific transmissibility spectrum evaluated from Eq. (3). To avoid this problem and to be consistent with the three-axis method required in ISO 5349-1 (2001) for the measurement and assessment of the hand-transmitted vibration exposure, the finger transmissibility in this study was determined based on the magnitude of the total vibration transmissibility (TrTotal) defined as follows:

| (4) |

Because the handle vibration magnitude at each frequency in the three directions was controlled theoretically the same (i.e. AHandle_X(ω) = AHandle_Y(ω) = AHandle_Z(ω)), the magnitude of the total finger transmissibility function was also alternatively estimated from the direction-specific transmissibility functions evaluated from Eq. (3) using the following formula:

| (5) |

In reality, there were some minor differences (<5%) among the vibrations measured in the three axes. Several studies have demonstrated that the glove transmissibility is not substantially affected by the vibration spectra (Rakheja et al., 2002; Dong et al., 2002; McDowell et al., 2013; Welcome et al., 2012). For this reason, the two spectra used in the original glove test standard are replaced with a single spectrum (ISO 10819, 2013). These observations suggest that the possible minor differences among the three axes vibrations are unlikely to significantly affect the transmissibility in each axis. The transmissibility values evaluated using Eqs. (4) and (5) should be very similar. This was verified in this study.

After the magnitudes of the transmissibility spectra with and without wearing a glove (TrTotal_Gloved-hand and TrTotal_Bare-hand) were obtained, the glove finger transmissibility spectrum (TrTotal_-Glove) was computed using the following formula:

| (6) |

2.5. Statistical analyses

A general linear model for the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the significance of the effects of glove condition (gel-filled, air bladder, no gloves), measurement point (10 points shown in Fig. 3), and applied hand force (four levels) on the vibration transmissibility. Whenever necessary, stratified ANOVAs were also performed to determine the significance of the finger response differences in different frequency ranges. The ANOVAs were performed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0). Differences were considered significant at the p < 0.05 level.

3. Results

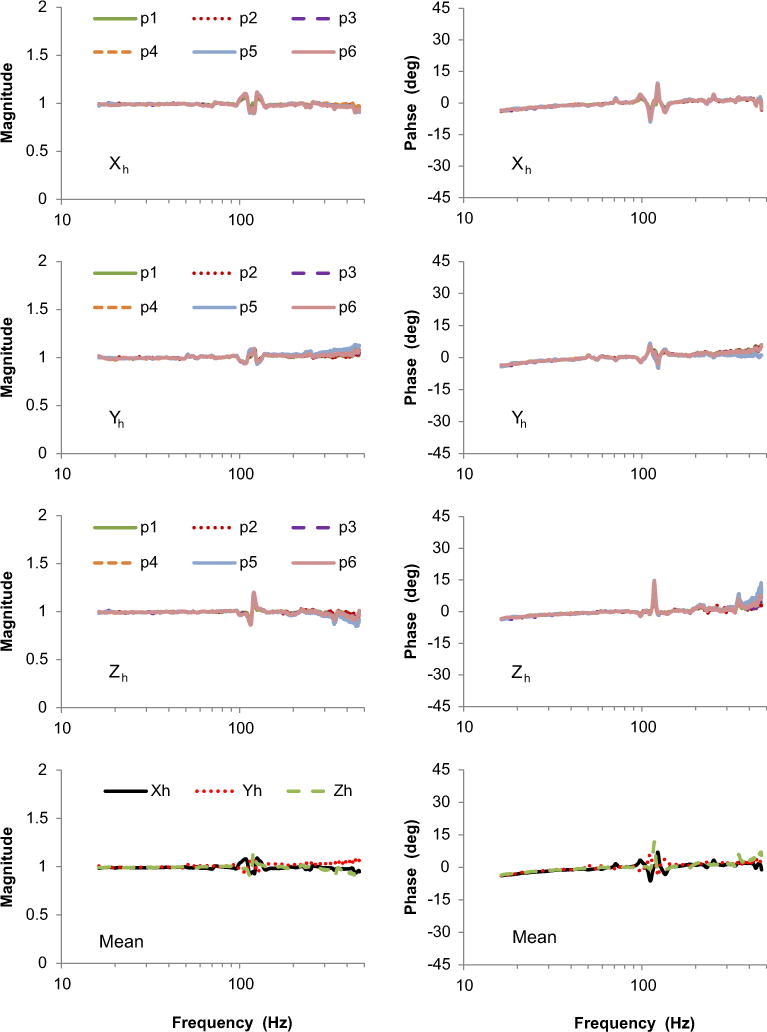

3.1. Dynamic responses of the handle surface

Fig. 5 shows the vibration transmissibility spectra of the six points on the handle in the finger contact area, together with the mean spectra in the three orthogonal directions. The magnitudes are generally in the range of 0.95–1.05 and the phase angles are generally in the range of −5° to 5°, except at some limited frequencies. The vibrations at all the points are very similar at less than 300 Hz in all the directions. Their differences generally increase with the increase in frequencies but they are generally within the range of 10% from their average values. This is partially because the major resonances of the handle are about 600 Hz, as identified on a 1-D test system with an excitation up to 1600 Hz. They have little influence on the responses of the handle base where the fingers contacted with the handle. Because the tape adds some constraints and damping to the split handle, it may also reduce the unevenness to the vibration distribution on the handle.

Fig. 5.

Vibration transmissibility spectra of the handle surface in the finger contact area in the three orthogonal directions.

Without affecting the basic trends of the near-unity transmissibility spectra, some limited fluctuations (within ±10%) in the range of 100–130 Hz can be observed in Fig. 5. They result from the global responses of the handle fixture assembly on the flexible linkages connected to the three shakers (Fig. 2). The mass of the assembly is more than 2.5 kg, which is more than 7 times of the effective mass of the hand-arm system at more than 100 Hz (about 0.33 kg according to Dong et al., 2012). As a result, the hand coupling cannot substantially affect the fluctuations and the fluctuations are also reflected in the finger response spectra in the same frequency range, as shown in Figs. 6–8. This nature makes it possible to reduce such errors in the normalization of the spectra using the handle response as a reference. Because the fluctuations are very similar in the finger responses with and without wearing a glove, they can be substantially eliminated when Eq. (6) is used to calculate the final glove transmissibility, as shown in Fig. 9. Similarly, the non-unity transmissibility (>5%) at some high frequencies (>300 Hz) observed in Fig. 5 can also be substantially reduced from the normalizations.

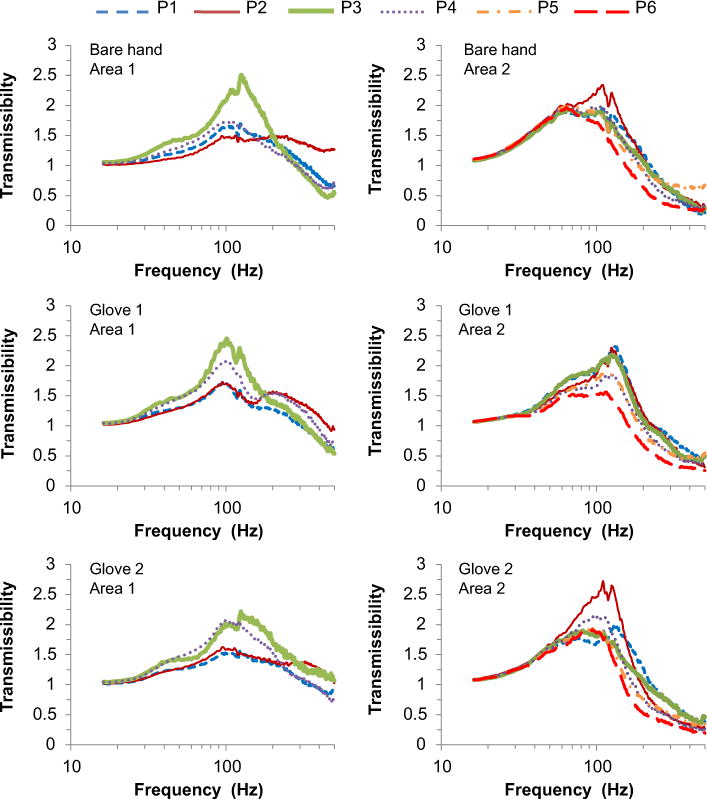

Fig. 6.

Comparisons of the mean total vibration transmissibility spectra at the six points in each of the two measurement areas of the fingers under the 30 N grip and 50 N push action. Only four points were visible to the laser for Gloves 1 and 2 for Area 1.

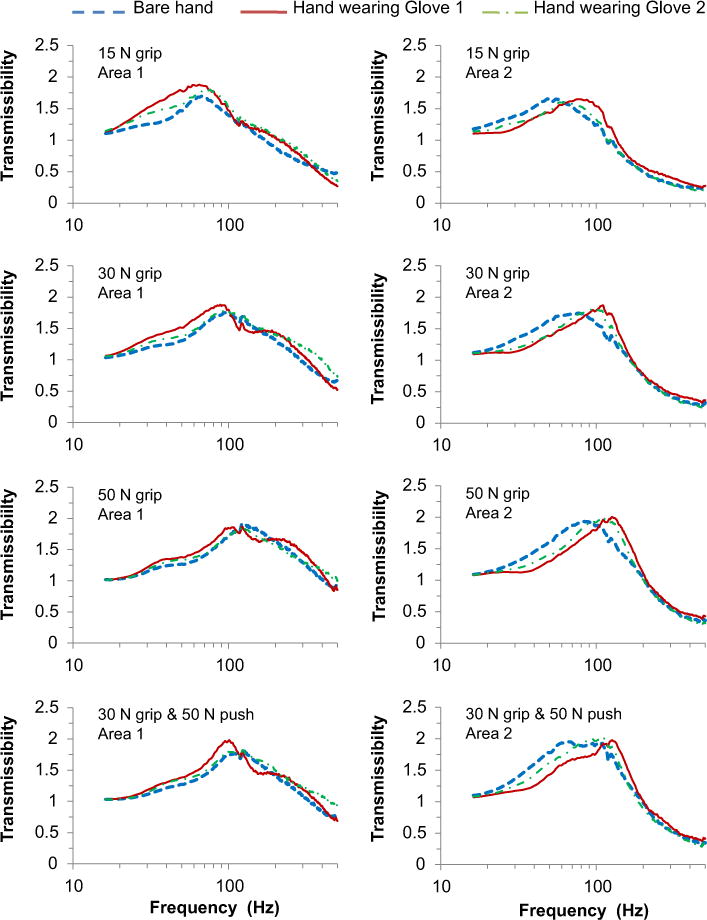

Fig. 8.

Comparisons of the finger vibration transmissibility spectra measured with and without wearing the vibration-reducing gloves under the four coupling actions (15 N, 30 N, 50 N, and combined 30 N grip and 50 N push).

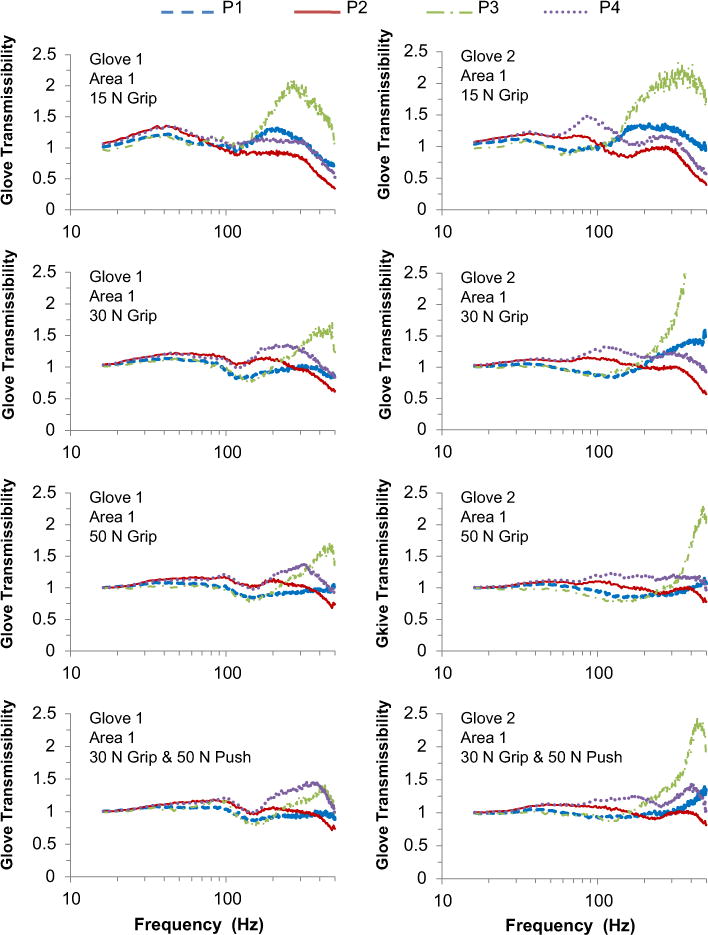

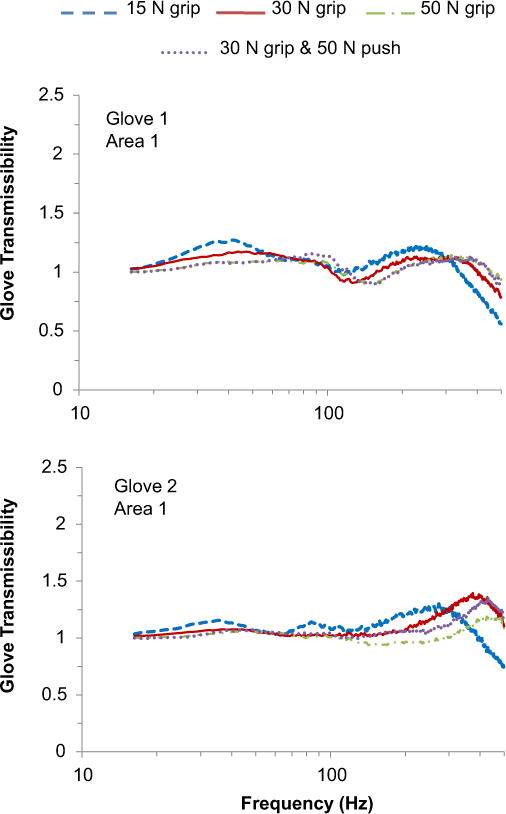

Fig. 9.

Comparisons of the glove vibration transmissibility spectra at the four locations (P1–P4) in Area 1.

3.2. Vibration transmissibility of the fingers

As examples, Fig. 6 shows the averaged magnitudes of the total vibration transmissibility spectra measured with the seven subjects for the force treatment of 30 N grip and 50 N push. Each column in the figure displays each of three hand treatments (Bare hand, Wearing Glove 1, and Wearing Glove 2). Both Eqs. (4) and (5) were used in the evaluation of these spectra. Their differences were generally less than 1% in the frequency range of concern in this study, with the maximum difference less than 2%. For simplicity, the data evaluated using Eq. (5) were applied in the remaining analyses.

Fig. 6 demonstrates that the shape of the finger transmissibility spectrum generally varied with the measurement point and the measurement area. A statistical analysis of the mean values of the finger transmissibility over the entire frequency range for the test treatments was performed. The results are listed in Table 2. They confirmed that the transmissibility varied significantly with the glove treatment, measurement location/point, and applied hand force. The interaction between measurement location and applied hand force was significant as was the interaction between measurement location and glove condition. The interaction between glove treatment and applied hand force was not significant.

Table 2.

Results of ANOVA with the mean transmissibility values of the seven subjects.

| Source | Degrees of freedom | F-factor | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glove | 2 | 6.53 | 0.002 |

| Force | 3 | 341.82 | 0.000 |

| Location (point) | 9 | 223.62 | 0.000 |

| Glove × force | 6 | 0.29 | 0.941 |

| Force × location | 27 | 3.57 | 0.000 |

| Glove × location | 18 | 7.37 | 0.000 |

3.2.1. Effects of measurement location on finger vibration transmissibility

As also shown in Fig. 6, the transmissibility spectra on the index and middle fingernails (P1 and P2 in Area 1) were similar at frequencies less than 125 Hz, regardless of the glove condition. While their resonant frequencies peaked at lower magnitudes than the other measurement points, the vibration at the fingernails was amplified over a wider frequency band than the others. The highest transmissibility was observed at the points in the neighborhood of the second knuckle area (P3–P4 in Area 1 and P1–P4 in Area 2). In the major finger resonance range, the peak vibration in this finger region was twice that of the handle regardless of glove condition.

3.2.2. Effects of grip force on finger vibration transmissibility

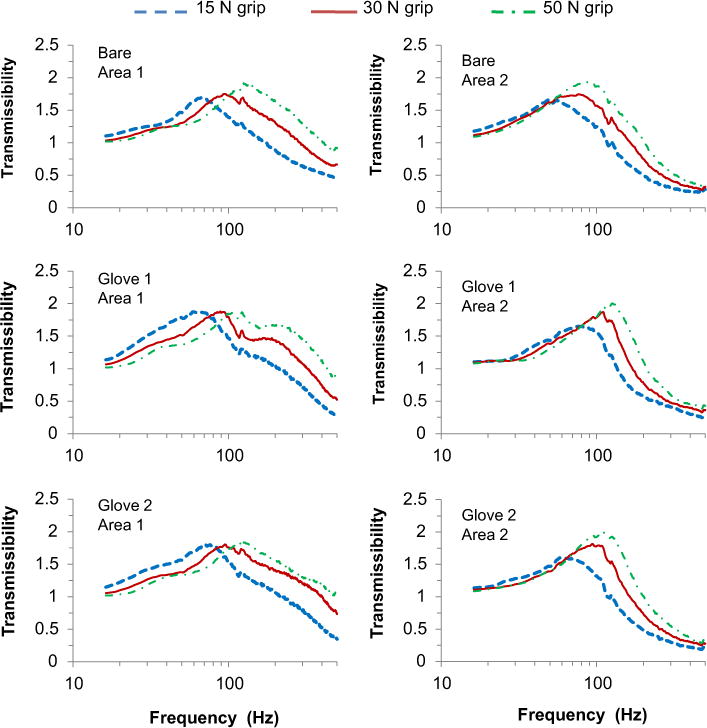

To clearly demonstrate the grip force effect, the transmissibility spectra at the four points (P1–P4) in Area 1 for each test treatment were averaged to represent the mean transmissibility in Area 1. Similarly, the spectra at the six points in Area 2 were averaged to represent that in Area 2. The results are plotted in Fig. 7. The major resonant frequencies were identified from the spectra shown in these figures, which are listed in Table 3. Increasing the grip force increases the resonant frequency in both areas, regardless of the glove condition. While the peak magnitudes for different forces in Area 1 are similar to each other, the peak transmissibility amplitude in Area 2 was increased with the higher grip force. While the transmissibility values at most frequencies in Area 1 are different (p < 0.05), the transmissibility values at most frequencies in Area 2 below 50 Hz were not significantly affected by the grip force (p > 0.05). The results shown in Fig. 7 also indicate that increasing grip force generally reduces the finger vibration at frequencies lower than the finger fundamental resonance frequency but increases the vibration at higher frequencies.

Fig. 7.

Comparisons of the finger vibration transmissibility spectra measured under the three grip forces (15 N, 30 N, and 50 N).

Table 3.

Average resonance frequencies of the finger responses in the two measurement areas.

| Area 1 (Hz) | Area 2 (Hz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grip force (N) | 15 | 30 | 50 | 15 | 30 | 50 |

| Bare hand | 68 | 95 | 124 | 49 | 76 | 88 |

| Wear Glove 1 | 65 | 89 | 108 | 78 | 110 | 126 |

| Wear Glove 2 | 70 | 95 | 123 | 61 | 94 | 110 |

3.2.3. Effects of glove on finger vibration transmissibility

As shown in Fig. 8, the gloves affected the vibration transmissibility in the two measurement areas differently. In Area 1, both gloves generally increased the vibration transmitted to the fingers but the effects of Glove 2 on the finger vibration were very small at the grip force equal to or higher than 30 N. In Area 2, the gloves reduced the finger vibration at frequencies below the major resonant frequency but generally increased the vibration at higher frequencies, which is similar to the effect of grip force on the finger vibration transmissibility shown in Fig. 7. As also shown in Fig. 8, the differences – both for amplification and attenuation – from the bare hand for Glove 1 were generally greater than those of Glove 2 in both finger areas at each force level.

3.3. Vibration transmissibility of glove fingers

Using Eq. (6), the vibration transmissibility spectra of the glove fingers at the four points (P1–P4) in Area 1 were calculated from the data shown in Fig. 6. The four spectra are plotted in Fig. 9, which shows the effects of measurement location on the glove finger transmissibility. As expected, the transmissibility spectra at low frequencies are very similar to each other and are close to unity. Their major differences appear at frequencies greater than 100 Hz.

To clearly identify the effects of hand force on the glove finger transmissibility, the four transmissibility spectra in Area 1 for each force treatment shown in the left column of Fig. 9 were averaged. The results are shown in Fig.10. There are two major resonances for each glove. The first one is below100 Hz and the second is at higher frequencies. Both resonances generally shifted to higher frequencies with the larger grip force actions for both gloves. At the lowest grip force (15 N) the vibration was amplified over a broad band up to about 350 Hz for Glove 1 and 400 Hz for Glove 2. At the higher force levels, the level of amplification tended to be reduced in a large frequency range. However, the second resonance for Glove 2 was at a higher magnitude for the 30 N grip and the combination of 30 N grip and 50 N push. There was some vibration attenuation for Glove 1 at some frequencies in the range of 100–200 Hz. There was also some vibration attenuation for Glove 2 at the 50 N grip force in the frequency range of 100–300 Hz.

Fig. 10.

Effects of the force on the mean glove vibration transmissibility spectra in Area 1.

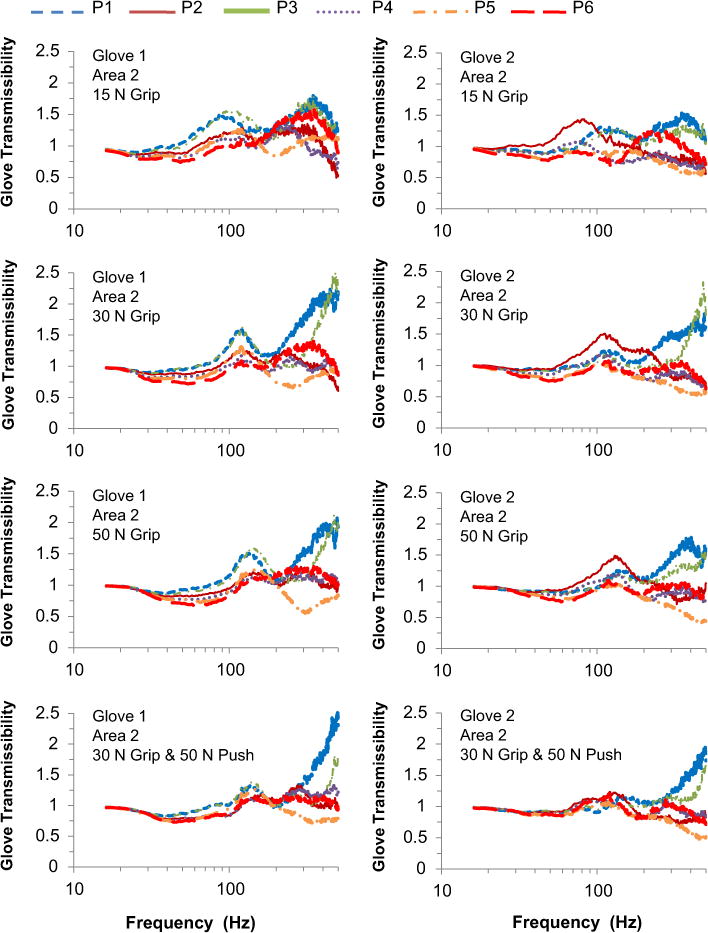

Similarly, the effects of the measurement location on the vibration transmissibility spectra of the glove fingers in Area 2 are shown in Fig. 11. The effects of hand force on the mean transmissibility spectra of the six points in Area 2 are shown in Fig. 12. Similar to those in Area 1, the transmissibility spectra in Area 2 at the low frequencies are similar to each other and they are close to unity; the major location effects are evident in the high frequency range (>100 Hz). As also shown in Fig. 11, there was strong amplification at the middle knuckle of the index finger for both gloves, which is also similar to the larger amplification at the first knuckle of the index finger in Area 1 at frequencies above 300 Hz for both gloves shown in Fig. 9. As shown in Fig. 12, the resonances also generally shifted to a higher frequency with the larger forces. However, unlike that observed in Area 1, the first major resonant peak in Area 2 was shifted to more than 100 Hz; the gloves also surprisingly reduced the vibration transmitted to the fingers between 20 and 80 Hz. The maximum mean reduction was 22% for Glove 1 and 15% for Glove 2. The specific frequency range of the reduction depended on the applied grip force. Increasing the force generally shifted the resonances to higher frequencies.

Fig. 11.

Comparisons of the glove vibration transmissibility spectra at the six locations (P1–P6) in Area 2.

Fig. 12.

Effects of the force on the mean glove vibration transmissibility spectra in Area 2.

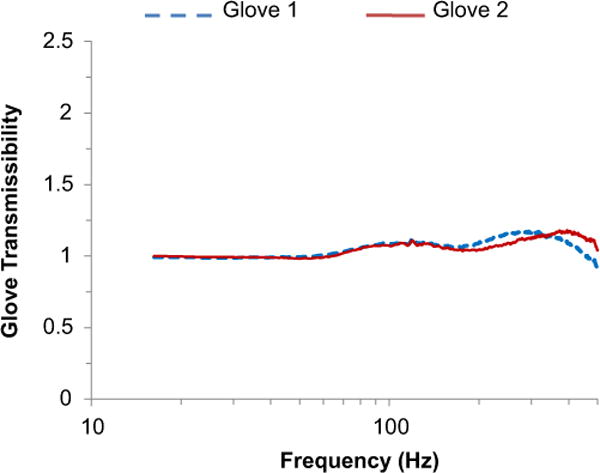

To clearly demonstrate the glove effect, the overall mean transmissibility spectrum for each glove was averaged over those measured on all the points at both Areas 1 and 2 for all four hand/force actions. The results are shown in Fig. 13. Surprisingly, the mean transmissibility spectra of these two gloves below 150 Hz are very similar to each other. On average, neither glove significantly (>5%) reduced the vibration transmitted to the fingers at frequencies below 400 Hz but marginally amplifies (<17%) the vibration through much of the exposure bandwidth tested. Fig. 13 indicates that Glove 1 is only effective at reducing finger-transmitted vibration at frequencies above 400 Hz. Similarly, the transmissibility trend shown in the figure suggests that Glove 2 may only effectively reduce the finger-transmitted vibration at frequencies above 500 Hz.

Fig. 13.

Comparison of the overall mean transmissibility spectra at the fingers of the two gloves.

4. Discussions

This study used a 3-D laser vibrometer to investigate the effectiveness of the vibration-reducing gloves for attenuating the vibration transmitted to the fingers. The fingers of the subjects were exposed to simultaneous random vibration in the three orthogonal directions over a range including frequencies typical for many tools. The results of this study provide very useful information to enhance the understanding of the mechanisms of the glove effects, including the influence of grip force on the mechanisms. They also provide useful information for assessing whether such gloves are helpful for reducing finger-transmitted vibration. They may also help better design and evaluate vibration-reducing gloves.

4.1. Mechanisms of bare finger vibration responses

Similar to the hand model proposed before (Dong et al., 2009, 2012), each bare finger in a grip action can be conceptually considered as a flexible curved beam flexibly connected to a finger base (the remaining hand substructures) and flexibly attached to the foundation of motion (handle) along the beam. The fingertip is at the free end of the beam; its effective mass is smaller than any other finger section and its contact stiffness is likely to be more than that at other finger contact locations because the highest contact pressure on a smooth cylindrical handle is usually at the fingertip contact area (Wimer et al., 2010). For these reasons, the resonant frequency of the fingertip (Area 1) should be higher than that at the proximal area (Area 2). This prediction was confirmed from the measured vibration transmissibility spectra of the bare fingers, as shown in Fig. 7 and Table 3. Increasing the grip force basically increases the stiffness and damping of the finger structure and its contacts and connections; hence, increasing the grip force increases the finger resonant frequency, as also confirmed from the results shown in Fig. 7 and Table 3. This is also consistent with that observed in the driving-point biodynamic responses of the fingers (Dong et al., 2008, 2012).

4.2. Mechanisms of glove effects on the finger vibration responses

A major functional mechanism of the VR gloves is their passive suspension effect by reducing the contact stiffness and providing damping at the hand–handle interface (Dong et al., 2009). This mechanism seems to play a dominant role in determining the effect of gloves on the vibration transmissibility at the fingertip area (Area 1). On both gloves, increasing the grip force increased not only the finger contact stiffness but also the glove contact stiffness (Dong et al., 2008). As a result, increasing the grip force generally made the glove suspension function less effective, as also shown in Fig. 10. This is consistent with the theoretical prediction (Dong et al., 2009). Also consistent with the general principle of the passive suspension (Harris, 1996), the reduced contact stiffness by the gel-filled glove (Glove 1) slightly reduced the resonance at Area 1, as shown in Table 3, and increased the responses in the resonant regions, as shown in Fig. 10. These phenomena are also consistent with those predicted using a glove model established based on this cushion mechanism (Dong et al., 2012). The basic effects of the air bladder glove (Glove 2) on the glove transmissibility shown in Fig. 10 are similar to those of Glove 1. However, Glove 2 (air bladder glove) had little effect on the resonance frequency of the fingers at the fingertip area, as shown in Table 3. Its effects on the finger vibration are also generally small, especially at the grip force equal to or greater than 30 N, as shown in Fig. 8. These are partially because the pressure at the fingertip area (Area 1) is usually higher than that at many other locations in the hand contact area (Aldien et al., 2005; Wimer et al., 2010); the pressure difference makes the air in the fingertip area of this glove partially move to other locations, especially at the higher force levels. As a result, the air glove fingers cannot effectively suspend the fingers. This is one of the reasons this glove cannot significantly isolate the vibration transmitted to the fingers.

The effects of the glove on the finger vibration transmissibility at the proximal area (Area 2) are basically opposite to those at Area 1. Specifically, the gloves increased the major resonant frequency, as shown in Table 3; the gloves did not increase the finger vibration at frequencies lower than the resonant frequency but reduced the vibration relative to the bare hand. These phenomena suggest that the effects of the gloves have another mechanism: they do not function as a cushion but they actually increase the system stiffness of the fingers at Area 2. The stiffness increase is likely to result from the re-distribution of the finger contact pressure and increased grip effort induced from wearing a glove. Specifically, the gloves usually wrinkle in a grip action, particularly in Area 2 where the bare finger contact pressure is usually lower than that in some other areas (Wimer et al., 2010). Unlike the desired glove cushion function, the wrinkles may actually increase the contact stiffness of the fingers in Area 2. Furthermore, to reach the same grip force measured on the handle as that in the bare hand test, the hand must also grip harder; usually by more than 20% (Wimer et al., 2010). This may increase not only the finger contact stiffness but also the structural stiffness of each finger and their connections with the remaining hand-arm substructures. The increased overall system stiffness increases the resonance frequency of the fingers. This explains why both gloves increased the resonant frequency at Area 2. This also explains why the effects of gloves on the finger transmissibility in Area 2 shown in Figs.11 and 12 are similar to the effects of grip force on the finger transmissibility. Probably because Glove 1 requires more grip effort (about 35%) than Glove 2 (about 25%) (Wimer et al., 2010; Welcome et al., 2012), the resonant frequency of the fingers at each force level with Glove 1 is higher than that with Glove 2, as also shown in Table 3.

According to the resonant frequency formula and the suspension mechanism (Harris, 1996; Dong et al., 2009), the major reason for the ineffectiveness of the gloves for reducing the fingertip-transmitted vibration at less than 400 Hz is the effective mass of the fingertip is too small, relative to the contact stiffness for gloves that are feasible for practical applications. The suspended effective mass of the glove is also too small to play an important role except at high frequencies. However, the importance of the fingertip and glove effective mass generally increases with the increase in frequency as the vibration becomes more and more concentrated in the contact region with the increase in frequency. Because the gel-filled glove has more mass than the air bladder-filled glove, the former generally has a lower cutoff frequency and reduces more high frequency vibration, as shown in Fig. 13. This explanation is also consistent with that found in a previous study on the glove material vibration transmission (Xu et al., 2011).

4.3. Implications of the mechanisms and findings

4.3.1. Applied grip force

The results of this study, as shown in Fig. 7, suggest that the effect of the grip force on finger-transmitted vibration is frequency-specific. If the tool’s dominant vibration is below 80 Hz, a tighter grip may marginally reduce the finger-transmitted vibration. However, the tighter grip in this frequency range may increase the overall vibration transmitted to the entire hand-arm system, as reflected from the increased biodynamic response of the system (Kihlberg, 1995). Furthermore, increasing the grip force also increases hand fatigue and the potential for hand injuries (Silverstein et al., 1987). Hence, increasing the grip force is not an acceptable approach to reduce the finger vibration in this frequency range. The results shown in Fig. 7 also indicate that the increased grip can greatly increase the finger vibration at more than 100 Hz, especially in the major finger resonance range (100–300 Hz) (Dong et al., 2012). While the high finger biodynamic frequency weighting is also in this frequency range, it may be useful to reduce the finger vibration by applying a grip force to a tool handle as lightly as possible, especially on high frequency tools, provided that this is consistent with safe work practice and control of the tool. This is also consistent with general ergonomic recommendations on the grip force.

4.3.2. The vibration reduction of the gloves in the proximal area

The results of this study suggest that the VR gloves cannot significantly reduce the vibration at frequencies less than 400 Hz in the fingertip area, but the gloves can reduce the vibration in the finger proximal area below 80 Hz. This is in the range of dominant vibrations of some tools such as chipping hammers, rivet hammers, and low-frequency grinders. If the finger health effects are closely related to the vibration in this area, the glove effect may play a certain role in reducing the health effects. While this hypothesis remains unproven, the above-described vibration reduction mechanism for the proximal area suggests that some regular work gloves can be used to achieve the same reduction. This has also been reported in a study (Cheng et al., 1999). Hence, such vibration reduction is unlikely to be a unique feature of the VR gloves.

It should also be noted that the effect of the glove on the contact stiffness re-distribution is likely to be affected by the geometrical shape and size of a tool handle. Hence, the glove effect on the 40 mm cylindrical handle observed in this study may not be the same as that on other handles. However, the re-distribution mechanism dictates that the glove may reduce the finger vibration at some locations in a certain frequency range but the changed contact stiffness and damping may also increase the vibration at some other locations or at other frequencies. Whether these changes are beneficial may depend primarily on the tool vibration spectra and the mechanisms of vibration-induced finger injuries and disorders, which remain formidable research tasks.

4.3.3. The criterion on the fingers of an anti-vibration glove defined in ISO 10819

According to the anti-vibration glove criteria defined in the new version of the standard (ISO 10819, 2013), Glove 2 (air bladder-filled glove) is among the best glove designs (Welcome et al., 2012). However, its overall reduction of the vibration on the fingers at less than 80 Hz was less than 2%, as shown in Fig. 13. In a large frequency range (80–400 Hz), this glove amplified the vibration by more than 10% at some frequencies. Its vibration attenuation at the high frequencies (>400 Hz) is less than that of Glove 1, as also shown in Fig. 13. A previous study also found that the materials of Glove 1 were more effective for attenuating high frequency vibrations (Xu et al., 2011).

These observations suggest that the glove finger criterion defined in ISO 10819 (1996 (2013) is not well founded. While the results of this study suggest that using any practical glove is unlikely to significantly reduce the finger-transmitted vibration, it is not necessary to require the same materials for every part of the anti-vibration glove. This, however, does not mean that a full-finger glove is not the best choice, because, in addition to its high frequency vibration attenuation, the full-finger glove can also provide some other benefits such as keeping the fingers warm and dry, reducing friction on the skin, and protecting the fingers from cuts and abrasions. On the other hand, it is excessive to require that the anti-vibration gloves must be full-fingered. Sufficient finger dexterity is required on some jobs, such as placing rivets in aircraft maintenance, and it is impossible to perform some tasks with a full-finger glove not only for working efficiency but also for safety in some cases. If the task cannot be modified to make it feasible to use a full-finger glove, a partial-finger vibration-reducing glove may be a better option than a bare hand, which can at least keep the core part of the hand warm and provide some other protection. Excluding such gloves from anti-vibration glove designation in the standard could discourage making the best choice for such situations. Allowing different materials, methods (for instance air bladder or bubble versus viscoelastic gel or traditional glove materials for warmth etc.), and thicknesses of materials for the fingers and palm may offer better possibilities for optimizing the design of the vibration-reducing gloves. For example, the gel-filled strategy of Glove 1 may be advantageous for higher frequency tools at the tips of the fingers while the air bladder may offer advantages to the proximal portion of the fingers and the palm.

4.3.4. Additional comments on glove selection

Considering the vast majority of the powered hand tools generating their dominant vibrations at less than 250 Hz (Griffin, 1990; 1997), the results of this study suggest that it is very difficult to find or make a glove that could reduce the vibrations transmitted to the fingers in this frequency range. Therefore, strategies for reducing the finger-transmitted vibration should primarily depend on the development and/or selection of better vibration tools, suspended handles, or suspended adapters (Dong et al., 2009). Once the transmissibility at the palm of a glove meets the critical high-frequency criterion of the standard (ISO 10819, 19969, 2013), one may pay major attention to the finger and hand comfort, contact stress reduction, minimizing the increased grip effort, and finger dexterity in glove selection.

If possible, a combination of a better tool and an appropriate glove is generally considered as a better strategy. However, the selection of the gloves does not have to be made among the certified anti-vibration gloves. For example, in the cases of low-frequency (<25 Hz) vibration tools such as vibrating forks, sand rammers, and tampers, the use of certified anti-vibration gloves is unlikely to be beneficial. If a suspended handle or adapter is flexible enough to cancel out the tool vibration, it may then be difficult to control a tool by wearing a certified anti-vibration glove. In such a case, other less cushioned gloves may be a better choice. While such gloves may be less effective for vibration reduction at the palm of the hand, they may not reduce grip strength as much (Welcome et al., 2011). Because the resilient features of such gloves may be similar to that of Glove 1, their finger vibration reductions at the high frequencies may be better than that with Glove 2.

The results of this study also suggest that a thick finger glove (Glove 1) can be helpful when a tool generates significant vibrations at more than 400 Hz. This is primarily because it has larger suspended effective mass than Glove 2. This suggests that the high frequency performance of a VR glove may be increased by adding some mass to the VR glove–finger interface. However, such a modified glove is also likely to further increase the grip effort because of the further increase in glove thickness (Wimer et al., 2010). A thick or bulky glove is not a good option if a forceful grip action is required in the tool operation.

5. Conclusions

A 3-D laser vibrometer was used to measure the 3-D vibrations transmitted to the fingers with and without wearing a glove. The measured data were used to evaluate the total vibration transmissibility of the glove fingers. This study confirms that the sum of the 3-D vibrations on the fingers depends on the measurement location and the applied hand force. This study found that reducing the grip force can reduce the finger resonant frequency and thus the vibration at higher frequencies, because lowering the grip force reduces both the finger contact stiffness and the structural stiffness of the fingers themselves. This study also finds that the gloves’ effects on the finger-transmitted vibration depend not only on the passive suspension function of the gloves but also on their influences on the distributions of the contact pressure and stiffness and on the hand grip effort. However, the importance of each mechanism varies with the specific location on the fingers. Specifically, the glove suspension function plays a major role in determining the vibration at the fingertip area. The response in the proximal area of the fingers seems more affected by the glove-induced increase in the grip effort and the contact and structural stiffness in this area. This study also confirms that the suspended effective mass of the glove plays an important role in determining the high frequency response of the fingers.

The representative glove types examined in this study generally suggest that vibration-reducing gloves are unlikely to be effective for reducing finger-transmitted vibration exposure in the dominant vibration frequency range (<250 Hz) of the vast majority of powered hand tools. Specifically, for the test conditions used in this study, these gloves increase the fingertip vibration below 400 Hz. While they reduce the vibration in the proximal area at some frequencies below 80 Hz, the overall vibration reduction on the entire finger area is either minimal (<3%) or the vibration is amplified below 400 Hz. Therefore, although the VR gloves can reduce some vibration transmitted to the palm of the hand, it may be on the conservative side to not account for the glove contribution toward the vibration reduction in the exposure risk assessment, especially when the vibration-induced health effects of the fingers are of primary concern.

The results of this study also suggest that the VR glove fingers may only be effective for reducing finger-transmitted vibration at very high frequencies (>400 Hz or higher). Although the gel-filled glove is less effective than the air bladder-filled glove for reducing the palm-transmitted vibration along the forearm direction, the former one is more effective for reducing the high frequency vibration than the latter one. This suggests that using the same glove materials throughout the glove does not guarantee the same ranking of the glove effectiveness at the fingers and palm, which further suggests that the glove finger criteria defined in the current anti-vibration glove test are not well founded. In other words, it is not necessary to require the same materials for the fingers and palm of an antivibration glove. While the results of this study suggest that it is very difficult to design a feasible glove to effectively reduce the finger-transmitted, especially fingertip-transmitted, vibration in the tool dominant vibration frequency range, the design of the glove fingers should focus on the other functions of the glove such as keeping the fingers warm, dry, and clean, reducing finger contact stresses, minimizing the increase in the grip effort, and protecting the fingers from cuts and chemical exposures.

Footnotes

Disclaimers

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Aldien Y, Welcome DE, Rakheja S, Dong RG, Boileau PE. Contact pressure distribution at hand-handle interface: role of hand forces and handle size. Int J Ind Ergon. 2005;35:267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AP. The effects of anti-vibration gloves on vibration induced disorders: a case study. J Hand Ther. 1990;3:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CH, Wang MJJ, Lin SC. Evaluating the effects of wearing gloves and wrist support on hand-arm response while operating an in-line pneumatic screwdriver. Int J Ind Ergon. 1999;24:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Concettoni E, Griffin M. The apparent mass and mechanical impedance of the hand and the transmission of vibration to the fingers, hand, and arm. J Sound Vib. 2009;325(3):664–678. [Google Scholar]

- Dong JH, Dong RG, Rakheja S, Welcome DE, McDowell TW, Wu JZ. A method for analyzing absorbed power distribution in the hand and arm substructures when operating vibrating tools. J Sound Vib. 2008;311:1286–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Dong RG, McDowell TW, Welcome DE, Rakheja S, Caporali SA, Schopper AW. Effectiveness of a transfer function method for evaluating vibration isolation performance of gloves when used with chipping hammers. J Low Freq Sound Vibrat Cont. 2002;21(3):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dong RG, Wu JZ, McDowell TW, Welcome DE, Schopper AW. Distribution of mechanical impedance at the fingers and the palm of human hand. J Biomech. 2005;38(5):1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong RG, McDowell TW, Welcome DE, Warren C, Wu JZ, Rakheja S. Analysis of anti-vibration gloves mechanism and evaluation methods. J Sound Vib. 2009;321:435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Dong RG, Welcome DE, McDowell TW, Wu JZ. Modeling of the biodynamic responses distributed at the fingers and palm of the hand in three orthogonal directions. J Sound Vib. 2012;332:1125–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jsv.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EN 420. Protective Gloves. General Requirements and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization (CEN) 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Goel VK, Rim K. Role of gloves in reducing vibration: analysis for pneumatic chipping hammer. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1987;48(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MJ. Handbook of Human Vibration. Academic Press; London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MJ. Measurement, evaluation, and assessment of occupational exposures to hand-transmitted vibration. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54(2):73–89. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MJ. Evaluating the effectiveness of gloves in reducing hazards hand-transmitted vibration. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:340–348. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.5.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MJ, Macfarlane CR, Norman CD. The transmission of vibration to the hand and the influence of gloves. In: Brammer AJ, Taylor W, editors. Vibration Effects on the Hand and Arm in Industry. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1982. pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CM. Shock and Vibration Handbook. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 5349-1. Mechanical Vibration – Measurement and Evaluation of Human Exposure to Hand-Transmitted Vibration – Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10819 (original version) Mechanical Vibration and Shock – Hand-arm Vibration – Method for the Measurement and Evaluation of the Vibration Transmissibility of Gloves at the Palm of the Hand. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10819 (updated version) Mechanical Vibration and Shock – Hand-arm Vibration – Method for the Measurement and Evaluation of the Vibration Transmissibility of Gloves at the Palm of the Hand. International Organization for Standardization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jetzer T, Haydon P, Reynolds DD. Effective intervention with ergonomics, antivibration gloves, and medical surveillance to minimize hand-arm vibration hazards in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(12):1312–1317. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000099981.80004.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihlberg S. Biodynamic response of the hand-arm system to vibration from an impact hammer and a grinder. Int J Ind Ergon. 1995;16:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mahbub H, Yokoyama K, Laskar S, Inoue M, Takahashi Y, Yamamoto S. Assessing the influence of antivibration glove on digital vascular responses to acute hand-arm vibration. J Occup Health. 2007;49(3):165–171. doi: 10.1539/joh.49.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell TW, Welcome DE, Xu XS, Warren C, Dong RG. Vibration-reducing gloves: transmissibility at the palm of the hand in three orthogonal directions. Ergonomics. 2013 doi: 10.1080/00140139.2013.838642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0014139.2013.838642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nataletti P, Paone N, Scalise L. International Conference on Environmental Health Risk. Bologna, Italy: 2005. Measurement of hand-vibration transmissibility by non-contact measurement techniques; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Paddan GS, Griffin MJ. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Hand-arm Vibration, Section 15(6) Nancy, France: 2001. Measurement of glove and hand dynamics using knuckle vibration. [Google Scholar]

- Rakheja S, Dong RG, Welcome DE, Schopper AW. Estimation of tool-specific isolation performance of anti-vibration gloves. Int J Ind Ergon. 2002;30:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rens G, Dubrulle P, Malchaire J. Efficiency of conventional gloves against vibration. Ann Occup Hyg. 1987;31(2):249–254. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/31.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D, Jetzer T. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Hand-Arm Vibrations. Umea, Sweden: 1998. Use of air bladder technology to solve hand tool vibration problems. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi GL, Tomasini EP. Hand–arm vibration measurement by a laser scanning vibrometer. Measurement. 1995;16(22):113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Scalise L, Rossetti F, Paone N. Hand vibration: non-contact measurement of local transmissibility. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein BA, Fine LJ, Armstrong TJ. Occupational factors and the carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(3):343–358. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700110310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensson A, Lundström R. Transmission of vibration to the hand. J Low Freq Noise Vib. 1992;11:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome DE, Dong RG, McDowell TW, Xu XS, Warren C. An evaluation of the revision of ISO 10819. Int J Ind Ergon. 2012;42(1):143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome DE, Dong RG, Xu XS, Warren C, McDowell TW, Wu JZ. An investigation on the 3-D vibration transmissibility on the human hand-arm system using a 3-D scanning laser vibrometer. Can Acoust. 2011;39(2):44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wimer BM, McDowell TW, Xu XS, Welcome DE, Warren C, Dong RG. Effects of gloves on the total grip strength applied to cylindrical handles. Int J Ind Ergon. 2010;40(5):574–583. [Google Scholar]

- Xu XS, Riley DA, Persson M, Welcome DE, Krajnak K, Wu JZ, Govindaraju SR, Dong RG. Evaluation of anti-vibration effectiveness of glove materials using an animal model. Bio-med Mater Eng. 2011;21(4):193–211. doi: 10.3233/BME-2011-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]