Abstract

We conducted five times surveys, in June, September and October in 2012; June and September 2013, to catalog the mushroom flora in Ulleung-gun, Republic of Korea. More than 400 specimens were collected, and 317 of the specimens were successfully sequenced using the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer barcode marker. We also surveyed the morphological characteristics of the sequenced specimens. The specimens were classified into 2 phyla, 7 classes, 21 orders, 59 families, 122 genera, and 221 species, and were deposited in the herbarium of Korea National Arboretum. Among the collected species, 72% were saprophytic, 25% were symbiotic, and 3% were parasitic. The most common order was Agaricales (189 specimens, 132 species), followed by Polyporales (47 specimens, 27 species), Russulales (31 specimens, 22 species), Boletales (10 specimens, 7 species), and so on. Herein, we also reported the first Bovista species in Korea, which was collected from Dokdo, the far-eastern island of Korea.

Keywords: Agaricales, Bovista, Dokdo, ITS sequences, Korea National Arboretum, New to Korea

Several indicators of biodiversity, such as changers in gene levels, populations, species, and ecosystems, show that biodiversity is dramatically decreasing [1]. Fungi can be found in almost every environment, and they are integral to many ecosystems. Mushroom-forming fungal species are prevalent in forests where they play critical roles in nutrient cycling, soil aggregation, and water retention and function as a food source for animals. In addition, mushrooms are economically important edible mushrooms are good food materials, and poisonous mushrooms can be utilized as medicinal resources [2]. In addition, mushrooms are used as biocontrol agents and as chemical producers of bioactive compounds used in industry, and they are useful in bioremediation [2,3,4,5]. Thus, it is important to understand the diversity, ecology, and evolution of mushrooms to advance our knowledge of current terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystems.

Mushroom biodiversity in Ulleung-gun, Korea is rich and it has been unexplored since 1995. Accoding to the sixth report of the "Fungal Flora of Ullung Island" series by Jung [6,7,8,9,10,11], there were 2 phyla, 4 classes, 18 orders, 53 families, 111 genera, and 161 species in Ulleung-gun. However, Jung's work was based solely on morphological identification, and there have been no additional reports of mushroom species since 1995. In the early 1990s, the introduction of molecular phylogeny into mushroom taxonomy drastically changed fungal nomenclature [12]. Therefore, today, morphology alone is insufficient for accurate identification, and these previously reported mushrooms need to be re-identified and re-evaluated in view of modern taxonomy, using a combination of molecular and morphological data.

The goal of this study was to evaluate and catalog the mushrooms in Ulleung-gun based on both molecular identification (using internal transcribed spacers of ribosomal DNA, a barcode marker for fungi) and morphological identification. In addition, we officially report a Bovista species that was incorrectly and unofficially reported as B. plumbea in 2012 in Dokdo, Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Macrofungi sampling sites

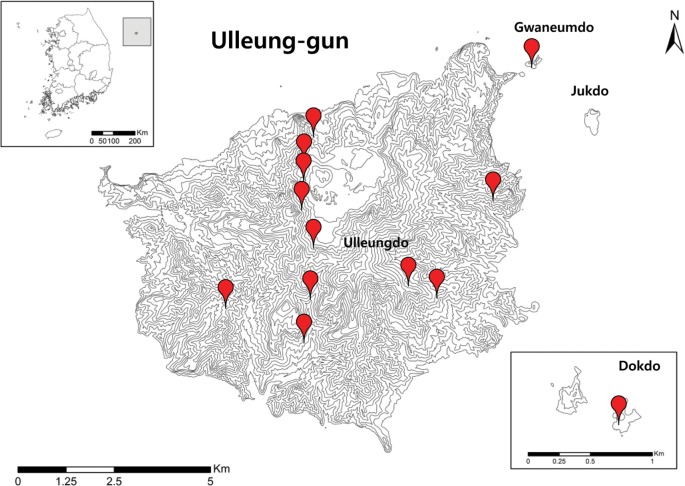

Ulleung-gun is a group of islands tha consists of the main island Ulleungdo, along with 44 other islands, including Dokdo. Ulleungdo, the eighth largest island in Korea, is located in the east side of the Korean Peninsula (coordinates 37°30' N, 130°52' E) [13]. Dokdo consists of two main islets (Dong-do and Seo-do) and 35 smaller rocks (coordinates 37°14'30'' N, 131°52'0'' E) (Fig. 1). These islands were creaded by a volcanic eruption between the Tertiary and early Quaternary Periods [6]. The climate of these islands is typically oceanic, with a warm average temperature (12.5℃) and ca. 1,200 mm of precipitation per year [6,13]. The sampling sites are indicated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Mushroom survey sites in Ulleung-gun. The points indicate the sites where specimens were collected.

Specimens and morphological observations

The 318 specimens used in the present study are listed in Table 1, and dried specimens were deposited in the herbarium of Korea National Arboretum (KH). The specimens were collected during June, September, and October 2012 and in June and September 2013. Macro-morphological characterstics were based on field notes and color photos of basidiomata. Micromorphological characteristics were obtained from the dried specimens after sectioning and rehydrating following the mothod of Largent et al. [14]. Microscopic observations were made using an Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a Jenoptik ProgRes C14 Plus Camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany). Measurements of microscopic characters were made using ProgRes Capture Pro v.2.8.8. software (Jenoptik). Morphological identifications were made based on reliable publications [15,16]. The current scientific names of the collected specimens were checked at the Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp) or MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org/defaultinfo.aspx?Page=Home).

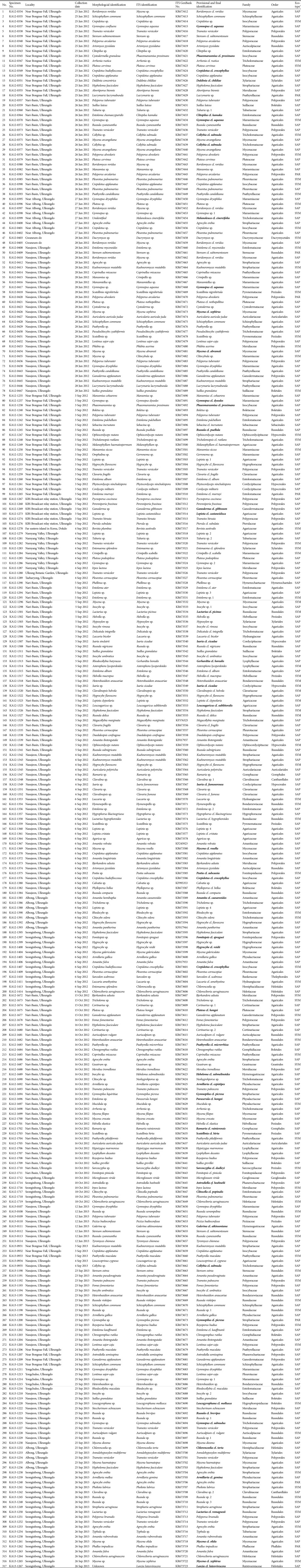

Table 1. Collected and sequenced mushroom specimens used in this study.

Bold-letters indicate the candidates of new to Korea.

ITS, internal transcribed spacer.

aEco-type (SAP, saprophytes; SYM, symbionts; PAR, parasites).

PCR amplification and sequencing

DNA was isolated from fresh fruiting bodies (approximately 0.1 g) using the DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. To amplify the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of ribosomal DNA, the ITS1F/ITS4 primer set was used. The PCR mixtures contained 0.5 pmol of each primer, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 15 ng of template DNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94℃ for 4 min, followed by 34 cycles of 94℃ for 40 sec, 55℃ for 40 sec, and 72℃ for 60 sec, and a final elongation step at 72℃ for 8min. PCR products were purified and sequenced by Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, Korea). All sequence data (318 sequences) were submitted to GenBank (KF17933, KF017937, KF017944, KF245923, KF576325, KF995353, and KR673412~KR673723) (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analyses of Bovista species

Raw sequences were proofread, edited, and assembled into contigs using PHYDIT 3.2 [17]. DNA sequences were aligned using ClustalX 1.81 [18], and then manually adjusted using PHYDIT. Ambiguously aligned regions were excluded from subsequent analyses. To determine the phylogenetic positions of the specimens, datasets were analyzed using maximum parsimony (MP) in PAUP ver. 4.0b10 [19] and by Bayesian inference in MrBayes 3.1.2 [20]. Parsimony analysis was conducted using a heuristic search with 1,000 random addition replicates and tree bisection-reconnection branch-swapping. MP bootstrap support values (MPBS) for internal nodes were calculated from 1,000 replicates of the MP analysis. Posterior probabilities (PPs) were approximated using the metropolis-coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo method. Two parallel runs were conducted with one cold and three heated chains for 3 million generations, starting with a random tree. The trees were sampled every 100 generations. We interpreted the convergence of two independent runs when the average standard deviation of the split frequencies dropped below 0.01. The trees obtained before the convergence were discarded using the burn-in command, and the remaining trees were used to calculate a 50% majority consensus tree and estimate PP. Reliable DNA sequence data for the other reported Lycoperdaceae (especially Bovista species) and outgroup species for use in the phylogenetic analyses were derived from Larsson and Jeppson [21], Bates et al. [22], and Yousaf et al. [23].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mushroom flora of Ulleung-gun

The provisional and final identifications were conducted based on morphological observations and ITS sequence identification due to the large number of undescribed species and that fact that some species can be very difficult to identify. If the results of the morphological identification (mainly using the keys for macro-characteristics) and ITS identification (similarity > 97%) did not match, we chose and considered the most closely related species accordcing to either the morphological or ITS identification. Alternatively, some are showed with the taxonomical abbreviation "cf." (Latin for confer = compares with) because these species could not be confirmed due to technical difficulties, such as poor sampling or a lack of sufficient information for the species. These species require additional studies. However, in present study, we evaluated the mushroom flora in Ulleung-gun based on the provisional identification (Table 1).

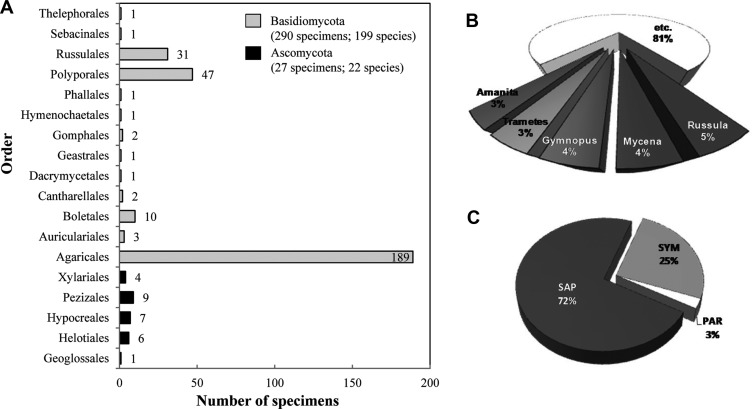

A total of 317 specimens were collected (2 phyla, 7 classes, 21 orders, 59 families, 122 genera, and 221 species). Of these 221 species, 199 (290 specimens) were in the phylum Bisidiomycota, and 22 (27 specimens) were in the phylum Ascomycota. The most common order was Agaricales (189 specimens; 132 species), followed by Polyporales (47 specimens, 27 species), Russulales (31 specimens, 22 species), Boletales (10 specimens, 7 species) and so on (Table 1, Fig. 2). Some specimens (54) could not be identified at the species level-we hypothesized that these may be new species; however more samples and additional phylogenetic studies are required. In addition, we discovered that 44 species were candidates for new species in Korea. Among these candidates, one species that is reported here for the first time (previously reported in 2012 as Bovista plumbea Pers. on Dokdo, a far-eastern Korean island) was intensively investigated. We report the taxonomical description of this species as a newly recorded Bovista species [B. aestivalis (Bonord.) Demoulin] in Korea.

Fig. 2. Orders and ampleness of collected specimens in Ulleung-gun. A, Number of specimens by order; B, Composition by genus; C, Composition by ecological type. SAP, saprophytes; SYM, symbionts; PAR, parasites.

Fig. 2A shows that almost all of our collected specimens belong to the Basidiomycota, which were nearly 10 times more mumerous than the Ascomycota (Table 1, Fig. 2). In the previous record of mushrooms in Ulleung-gun, Basidiomycota were nine times more abundant than Ascomycota (total: 2 phyla, 4 classes, 18 orders, 53 families, 111 genera, and 161 species [6,7,8,9,10,11]) (Table 2). The reason for this might be that Ascomycota which form smaller fruiting bodies, are generally duffucult to find using the naked eyes, and some species quickly disappear. However, according to Blackwell [24], the number of recorded Ascomycota (ca. 60,000 species) is two times greater than the number of Basidiomycota (ca. 30,000 species), even though most Ascomycota do not make fruiting bodies or are indistinct. Current DNA methodologies (e.g., pyrosequencing) make it possible to discover more fungi, especially Ascomycta, to evaluate fungal diversity. In addition, constant effort is required to secure the uncollected mushrooms recorded in Jung's reports [6,7,8,9,10,11] as well as small-sized mushrooms, especially those that belong to the Ascomycota, to accurately assess the biodiversity of mushroom flora.

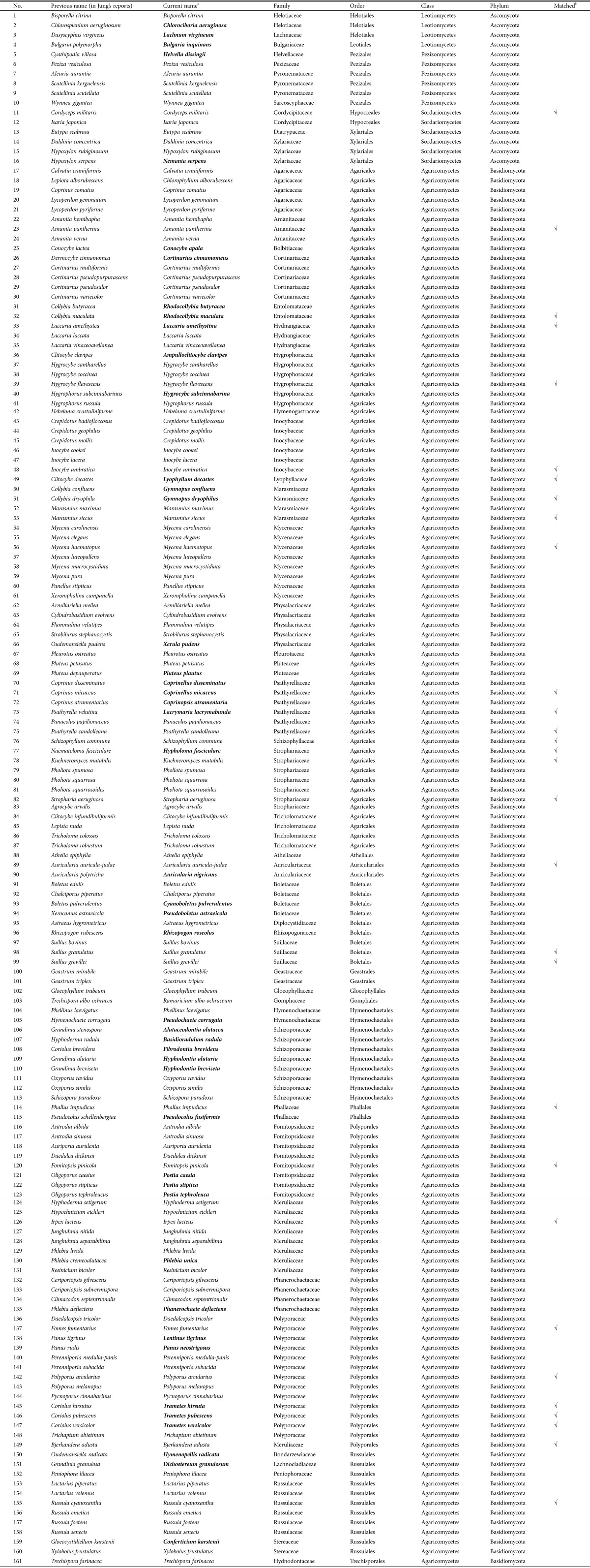

Table 2. Mushroom species previously recoreded in Ulleung-gun by Jung [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Bold letters indicate changed names.

aCurrent names were confirmed with referenced to the Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp) or MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org/defaultinfo.aspx?Page=Home).

bSpecies that matched our surveyed species.

Among the collected specimens, the genus Russula was the most aboudant in Ulleung-gun (5%, 15 specimens, 12 species) followed by the genus Mycena (4%, 13 specimens, 11 species), the genus Gymnopus (4%, 14 specimens, 7 species), the genus Trametes (3%, 11 specimens, 3 species), the genus Amanita (3%, 10 specimens, 8 species), and so on (Fig. 2B). The composition of the ecological types of the collected mushrooms is 72% saprophytes, 25% symbionts, and 3% parasites (Table 1, Fig. 2C). We found that only 30 of the current mushroom species were previously recorded (Table 2). Nevertheless, our collected mushrooms were nearly 1.5 times more diverse than the previously recorded mushrooms at the speices level.

Phylogenetic analysis of Korean Bovista aestivalis

Among the candidate new species in Korea, we report a Bovista species (Bovista aestivalis; KA12-1278). Although our specimen had been unofficially previously reported as B. plumbea in 2012, we found that this species clearly differed from B. plumbea. We intensively investigated this specimen, because it was the first time it was discovered on Dokdo, a far-eastern Korean island. The other species are also valuable; however, we did not have enough samples and taxonomic data. We will be subsequently report the remaing species in the near future once we obtain enough specimen samples and taxonomic information.

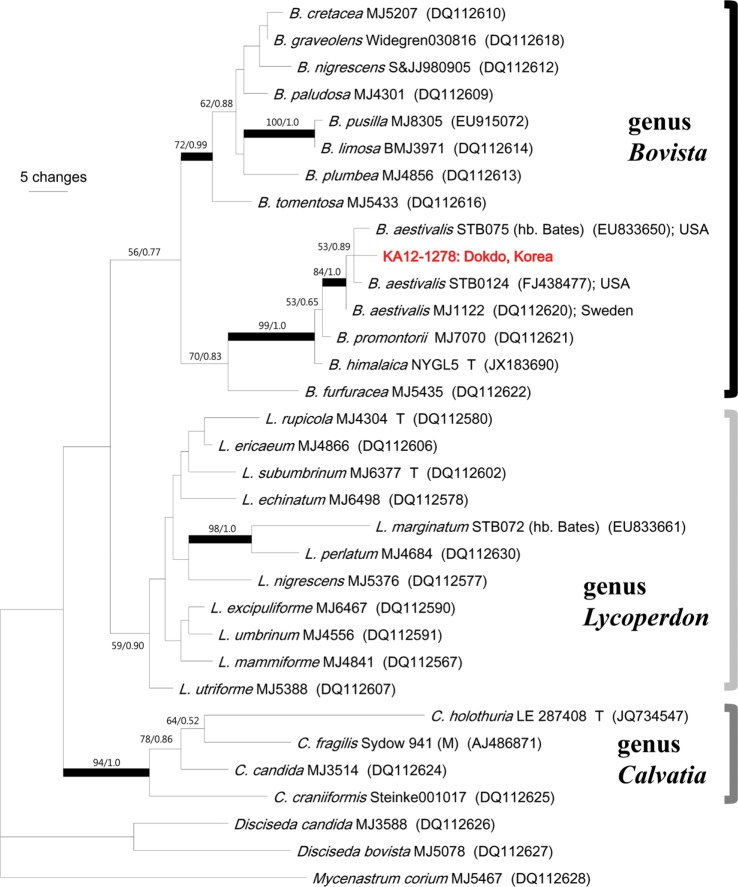

Alignment of the ITS sequences resulted in a total of 632 characters, which included 466 constant sites, 70 variable but parsimony-uninformative sites, and 96 parsimony-informative sites (Fig. 3). The MP tree was 358 steps with a consistency index of 0.62, a retention index of 0.71 and a homoplasy index of 0.38. Bayesian analysis used a GTR + I + G model, and the first 10,500 trees were discarded as burn-in (with a "burninfrac" value of 0.35). In the ITS tree, our specimens (KA12-1278, before considering B. plumbea), two American Bovista aestivalis strains (STB075 and STB0124), and a Swedish B. aestivalis stains formed a group with high supported values (MPBS/PP = 84/1.0). However, KA12-1278 was clearly distinct from B. plumbea MJ4856.

Fig. 3. One of the 18 most parsimonious trees from a heuristic analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences (33 taxa, 632 characters; tree length = 358, consistency index = 0.62, retention index = 0.71, homoplasy index = 0.38). Broad black branches indicate maximum parsimony bootstrap support value (MPBS) > 70% and Bayesian posterior probabilities > 0.95. Only MPBS > 50% are shown above or below branches. Mycenastrum corium MJ5467, Disciseda bovista MJ5078 and D. candida MJ3588 were used as outgroups.

Taxonomical description

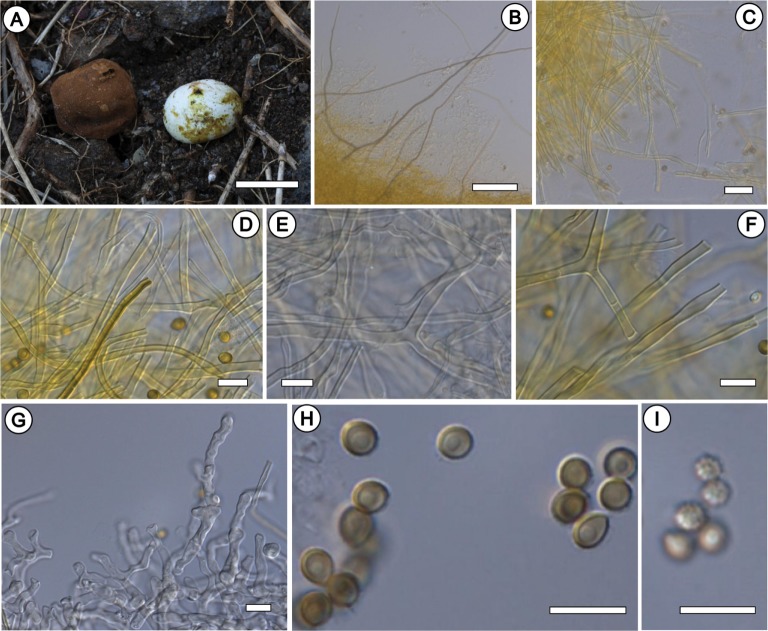

Bovista aestivalis (Bonord.) Demoulin, Beih. Sydowia 8: 143 (1979) (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. Bovista aestivalis KA12-1278. A, Fruiting bodies; B~E, Eucapillitial threads (mostly intermediate-type and rarely Lycoperdon-type); F, Paracapillitial threads (septate); G, Thick-walled hyphal elements of endoperidium (tightly interwoven and septate); H, I, Basidiospores (scale bars: A = 3 cm, B = 100 µm, C = 20 µm, D~I = 10 µm).

Basidiomata ca. 15~40 mm in diam., ca. 20~30 mm high, subglobose to pulvinate, a few thick rhizomorphs attached to substrate. Exoperidium minutely verruculose; whitish when young, becoming pale brown to brown when old. Endoperidium pale yellow to grayish yellow, papery. Gleba yellowish to olive-brown at maturity, and cottony. Subgleba yellowish-brown. Basidiospores released via a ragged apical pore.

Basidiospores 4.6~5.2 × 4.0~4.7 µm, length/width ratio 1.0~1.2 (n = 30), globose to subglobose, smooth to asperate, pedicel absent or slightly short (< 1.0 µm long), pale yellow to brown in 3% KOH mount, with a central oil drop. Basidia are not observed. Capillitium intermediate-type, rare Lycoperdon-type observed; eucapillitial threads ca. 3.0~4.0 µm in diam., thick-walled, subelastic near the ostiole, aseptate, straight, occasional dichotomous branching, irregular small-sized pores frequently present, yellow to pale brownish in 3% KOH mount; paracapillitial threads present, ca. 1.0~2.0 µm in diam., thin-walled, straight to subundulate, septate, hyaline to pale yellowish in 3% KOH mount.

Habitat

Humus soil with rocks and twig debris

Examined specimen

Korea, Gyeongbuk Province, Ulleung-gun, Dokdo, coll. S. K. Han, 4 Sep. 2012 (KA12-1278)

Comments

This specimen was identified as B. plumbea Pers. based on macro-morphological observations, and unofficially reported by S. K. Han in Dokdo, far-eastern island of Korea, for the first time in 2012. However, according to our ITS sequence analysis, our specimen formed a group with American (STB075 and STB0124) and Swedish (MJ1122) specimens of B. aestivalis, but it was clearly distinct from the ITS sequences of B. plumbea MJ4856 (Fig. 3) [21,22]. Microscopic characteristics also clearly distinguished B. aestivalis and B. plumbea, especially the size of basidiospores (B. plumbea: 5.6~6.4 × 4.8~5.6 µm, length/width 1.3, ovoid, long pedicel exist) and capillitium type (B. plumbea has a Bovista-type capillitium) [22]. Based on our intensive microscopic observations, our specimen was almost identical to the description of B. aestivalis, not B. plumbea.

Conclusion

By conducting surveys in 2012 and 2013 and by organizing the specimens secured in the Division of Forest Biodiversity and Herbarium of the Korea National Arboretum (KH), in this study, we identified 221 species in Ulleungdo and the nearby island regions (Gwaneumdo, Jukdo, and Dokdo). Although we reported a species, Bovista aestivalis, as new to Korea, we still have 43 additional candidate species that may be new to Korea as well as 54 specimens that were not identified to the species level. Therefore, more intensive morphological observations and additional specimens are needed. In addition, we will investigate the phylogenetic relationships in each monophyletic or polyphyletic group at the genus level to establish their taxonomical position based on a barcode marker (ITS sequences) and several protein-coding regions. The results of this study improve our understanding of mushroom flora and ecosystem in Ulleung-gun, as well as Korean mushroom diversity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the research fund of Korea National Arboretum (Project No. KNA 1-1-10).

References

- 1.Butchart SH, Walpole M, Collen B, Van Strien A, Scharlemann JP, Almond RE, Baillie JE, Bomhard B, Brown C, Bruno J, et al. Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science. 2010;328:1164–1168. doi: 10.1126/science.1187512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duarte S, Pascoal C, Cássio F, Bärlocher F. Aquatic hyphomycete diversity and identity affect leaf litter decomposition in microcosms. Oecologia. 2006;147:658–666. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirbaş A. Accumulation of heavy metals in some edible mushrooms from Turkey. Food Chem. 2000;68:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalač P, Svoboda L, Havlíčková B. Contents of cadmium and mercury in edible mushrooms. J Appl Biomed. 2004;2:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karmakar M, Ray RR. Current trends in research and application of microbial cellulases. Res J Microbiol. 2011;6:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullung island (I): on some corticioid fungi. J Plant Biol. 1991;34:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullŭng island (II): on some resupinate fungi. Korean J Mycol. 1991;19:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullung island (III): on some polyporoid fungi. Korean J Mycol. 1992;20:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullung island (IV): on some agaric fungi. Korean J Mycol. 1993;21:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullung island (V): on additional agaric fungi. Korean J Mycol. 1994;22:196–208. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung HS. Fungal flora of Ullung island (VI): on ascomycetous, auriculariaceous, and gasteromycetous fungi. Korean J Mycol. 1995;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gams W. A new nomenclature for fungi. Mycol Iran. 2014;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung SY, Park SH, Nam CH, Lee HJ, Lee YM, Chang KS. The distribution of vascular plants in Ulleungdo and nearby island regions (Gwaneumdo, Jukdo), Korea. J Asia Pac Biodivers. 2013;6:123–156. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Largent DL, Jonhson D, Watling R. How to identify mushrooms to genus III: microscopic features. Eureka (CA): Mad River Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Largent DL, Thiers HD. How to identify mushrooms to genus II: field identification of genera. Eureka (CA): Mad River Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breitenbach J, Kränzlin F. The fungi of Switzerland. Vols. 1-5 Lucerne: Verlag Mykologia; 1984-2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chun J. Computer-assisted classification and identification of actinomycetes [dissertation] Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swofford DL. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson E, Jeppson M. Phylogenetic relationships among species and genera of Lycoperdaceae based on ITS and LSU sequence data from north European taxa. Mycol Res. 2008;112(Pt 1):4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates ST, Roberson RW, Desjardin DE. Arizona gasteroid fungi I: Lycoperdaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) Fungal Divers. 2009;37:153–207. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousaf N, Kreisel H, Khalid AN. Bovista himalaica sp. nov. (gasteroid fungi; Basidiomycetes) from Pakistan. Mycol Prog. 2013;12:569–574. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackwell M. The fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 million species? Am J Bot. 2011;98:426–438. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]