Abstract

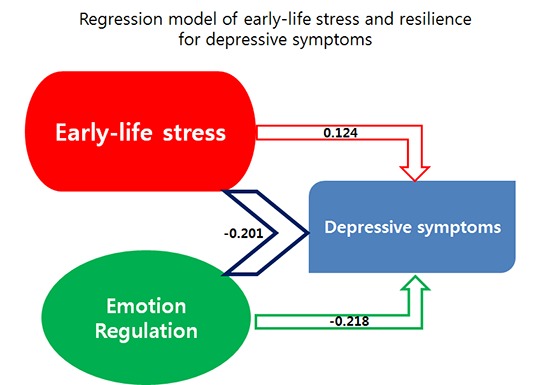

Early life stress (ELS) may induce long-lasting psychological complications in adulthood. The protective role of resilience against the development of psychopathology is also important. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships among ELS, resilience, depression, anxiety, and aggression in young adults. Four hundred sixty-one army inductees gave written informed consent and participated in this study. We assessed psychopathology using the Korea Military Personality Test, ELS using the Childhood Abuse Experience Scale, and resilience with the resilience scale. Analyses of variance, correlation analyses, and hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were conducted for statistical analyses. The regression model explained 35.8%, 41.0%, and 23.3% of the total variance in the depression, anxiety, and aggression indices, respectively. We can find that even though ELS experience is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and aggression, resilience may have significant attenuating effect against the ELS effect on severity of these psychopathologies. Emotion regulation showed the most beneficial effect among resilience factors on reducing severity of psychopathologies. To improve mental health for young adults, ELS assessment and resilience enhancement program should be considered.

Keywords: Depression, Anxiety, Aggression, Early-life Stress, Interparental Violence, Resilience, Emotion Regulation, Optimism

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Brain development is particularly robust during childhood and adolescence, a period in which a lifelong template of emotion, cognition, and behaviour has been made (1). Personality development is significantly influenced by parents and family environment. Early life stress (ELS) is defined as adverse early life experiences including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; neglect; and exposure to domestic violence (2). ELS may have a long-lasting harmful effect on cognitive and affective function in adulthood (3) and may be associated with increased risk for psychopathology such as depression, anxiety, and aggression later in life (3,4).

Unlike child abuse, of which deleterious effect is traditionally well-known, children's exposure to interparental violence has recently gathered attention from researchers because it is very common and associated with poor mental health in the exposed children (5). Children who witness interparental violence are more likely to perpetrate violence on an intimate partner in adulthood (6). Particularly in pre-schoolers, psychosocial outcomes are poorer in children who witnessed interparental violence than in children who did not (7). In a previous study we found that patients with major depressive disorder reported significantly more exposure to interparental violence than healthy controls (8).

Childhood maltreatment is also known to be associated with increased aggression in adulthood and an increased likelihood of becoming a physical abuser of one's own children or partner (9). Child abusers are more likely to have experienced parent-child aggression including physical maltreatment and a harsh and over-reactive parenting style (10). As compared to physical abuse, neglect is associated with a different profile of psychopathology that includes severe cognitive deficits and internalizing problems (11).

Resilience refers to the capacity to cope with stress and recover from adversity which has been filled with increasing implications from psychosocial and biological researches (12). Resilient individuals may not exhibit emotional or psychological problems despite exposure to adversity in their childhood. In a longitudinal study, Werner reported that one-third of a high-risk group of children who had experienced significant ELS grew into healthy, competent adults without serious psychopathology (13). Reivich and Schatte developed a test measuring resilience capacity and suggested that resilience is comprised of seven factors: emotion regulation, impulse control, realistic optimism, causal analysis, empathy, self-efficacy, and reaching out (14).

The relationship of psychopathology such as depression, anxiety, and aggression with ELS and resilience has not been sufficiently studied yet in Korea. Studies in a non-clinical setting are needed to develop management plans and prevention programs for use in the general population.

All Korean young men are required to undergo physical and psychological screening examination as a part of recruitment process into obligatory military service when they are 19 yr old. In the present study, we used the Korea Military Personality Test (KMPT) (15) to assess psychopathology including depression, anxiety, and aggression in military conscript candidates and ELS and resilience profiles were also measured to find significant association between ELS, resilience, and psychopathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The participants in this study were enlisted military service candidates who visited a Korean Regional Military Manpower Administration Office from April 27-30, 2009. All the examinees during this period were enrolled in this study. The percentage of the subjects in the present study was about 0.7 percent (487/70,126) of the examinees who had visited this office during 2009. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. We collected data on age, educational level, occupational status, average family income, and parents sharing a home with the enlistee (mother, father, or both), and administered surveys of ELS and resilience. All examinees took the KMPT, a comprehensive personality test developed by the Korea Ministry of National Defense and Korean Psychological Association (15,16).

The final analysis included 461 out of 487 examinees. Twenty-six examinees were excluded because we suspected that they provided unreliable responses, based on scores on the "feigning-bad response" and "infrequent response" indices of the KMPT (see Method) exceeding a standardized score of 70 (15). All subjects were male. The mean age of the participants was 18.4 ± 0.5 yr and the age range of subjects was between 18 and 20 yr. Most were students (76.1%) and lived with both parents (86.8%).

The Korea Military Personality Test (KMPT)

The Korean Psychological Association had developed the KMPT through research funded by the Korea Ministry of National Defence (15). The purpose of the KMPT is to identify soldiers who are at risk for maladjustment problems in the military or who may need further diagnostic screening, to exclude enlisted soldiers who are likely to have difficulty adjusting to military life, and to provide commanders with psychological data about potential maladjustment soldiers who show abnormal profiles. This test has been part of the routine conscription examination since 1999 in Korea.

The KMPT is comprised of 365 items with 'yes' or 'no' answers. There are three subsections examining validity, clinical psychopathology, and military adjustment in the KMPT. Each subsection consists of three validity scales (feigning-good response, FG; feigning-bad response, FB; infrequent response, INF), ten clinical scales (anxiety, AX; depression, DEP; somatization, SOM; schizophrenia, SCZ; personality disorder, PD; behavioural retardation, BR; criminality, CRI; aggression-hostility, AGG; desertion of duty, AWL; paranoia, PA), and six content scales (problems with preparedness for military life, MPE; problems with working in a group, GR; self-avoidance, SA; expression of hostility, HE; somatic symptoms, SMS; resistance to discipline or problems with conformity, CON), relatively. The validity scales are designed to detect feigning of insanity by healthy soldiers, hiding of mental illness by mentally ill soldiers. The clinical scales provide information about psychopathology. The content scales provide information about psychological or behavioural patterns associated with adjustment problems in the military. Standardized scores are used for statistical analyses. To study the relationship of psychopathology such as depression, anxiety, and aggression with ELS and resilience, we used scores on the DEP, AX, and AGG clinical scales as the primary outcome variables in this study. Test-retest reliability of each clinical scale factor was 0.77 for AX, 0.78 for DEP, 0.80 for SOM, 0.58 for SCZ, 0.80 for PD, 0.79 for BR, 0.81 for CRI, 0.81 for AGG, 0.83 for AWL, 0.75 for PA. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of each clinical scale factor was 0.61 for AX, 0.85 for DEP, 0.77 for SOM, 0.69 for SCZ, 0.72 for PD, 0.89 for BR, 0.79 for CRI, 0.86 for AGG, 0.81 for AWL, 0.82 for PA, respectively in the original study (15).

The Korean Childhood Abuse Experience Questionnaire

We assessed ELS using the Korean Childhood Abuse Experience Questionnaire (17) designed by Oh to assess abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual), neglect, and exposure to domestic violence during childhood and adolescence. The questionnaire consists of 34 questions about physical (5 questions) and emotional abuse (9 questions), neglect (10 questions), and exposure to interparental violence (10 questions), which were drawn from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (18) and modified in accordance with Korean culture. The questionnaire also includes 10 questions about sexual abuse drawn from a Korean scale developed by another researcher (19). All items have a 7-point Likert scale with weighted values. In the present study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's Alpha) was 0.787 for emotional abuse, 0.812 for physical abuse, 0.875 for neglect, 0.802 for sexual abuse, and 0.951 for exposure to domestic violence.

The resilience quotient test

We used a modified Korean version of resilience test which was originally developed by Reivich and Schatte to assess resilience (14). It contains 56 questions with 5-point Likert scale including 7 factors regarding emotion regulation (ER, the ability to manage our internal emotional state), impulse control (IC, the ability to manage impulsive behavioral expression), optimism (OP, the ability to maintain positive attitude about the future), causal analysis (CA, the ability to identify the causes of adversity), empathy (EM, the ability to understand other's emotional state), self-efficacy (SE, the sense that he/she are successful in his/her life or he/she can manage a problem which he/she are faced with), and reaching out (RO, the ability to enhance the positive aspects of life). The Korean version of this test was developed by Kim (20). To ensure the consistency of meaning between the original and the Korean versions, the translated items were back-translated into English by a bilingual graduate student. Two independent judges checked the equivalence of the original and the back-translated versions of the items. After discussing any issues of non-equivalence, the authors did the final editing of the translated versions. In the original data of the standardization study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's Alpha) of each factor with the general population was as following: ER (0.729), IC (0.705), OP (0.662), CA (0.702), EM (0.733), SE (0.755), and RO (0.774) (20).

Statistical analysis

We used analyses of variance and Duncan's post-hoc tests to compare scores on the DEP, AX, and AGG clinical scales of the KMPT among subgroups of participants based on demographic characteristics, such as education, occupation, socio-economic status, and parental status. We used correlation analyses and stepwise hierarchical multiple regression analyses to find significant modulating effect of resilience factors against ELS experience on severity of psychopathologies including DEP, AX, and AGG. Statistical significance threshold was set at P<0.05 (two-tailed test). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 20 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No. 2009-I010). Written informed consent was given from all the individual participants.

RESULTS

Psychopathology in demographic subgroups

Table 1 presents scores on the DEP, AX, and AGG scales of the KMPT in subgroups of participants based on demographics. Participants with a high school education or under reported significantly more depressive symptoms than did college students. When considering occupational status, participants who were unemployed reported more depression and anxiety symptoms than did students.

Table 1. Comparison of depression, anxiety, and aggression scores of KMPT by demographic subgroups.

| Demographic variables | No. (%) | Depression | Anxiety | Aggression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level† | ≤ High school in College in University | 129 (28.4) | 47.4 ± 0.7a | 46.8 ± 0.7 | 46.6 ± 0.8 |

| 190 (41.7) | 45.2 ± 0.5b | 44.4 ± 0.6 | 46.0 ± 0.5 | ||

| 136 (29.9) | 45.5 ± 0.7a,b | 45.3 ± 0.8 | 44.9 ± 0.8 | ||

| (df = 2) | F | 3.262 | 2.900 | 1.337 | |

| P | 0.039 | 0.056 | 0.264 | ||

| Occupational status* | None student employed | 64 (13.9) | 48.3 ± 0.9a | 48.3 ± 1.0a | 47.9 ± 1.1 |

| 351 (76.1) | 45.5 ± 0.4b | 44.8 ± 0.4b | 45.5 ± 0.4 | ||

| 46 (10) | 46.7 ± 1.1a,b | 45.8 ± 1.2a,b | 46.3 ± 1.2 | ||

| (df = 2) | F | 3.478 | 4.223 | 2.005 | |

| P | 0.032 | 0.015 | 0.136 | ||

| Socio-economic status | Low | 213 (46.6) | 46.8 ± 0.5 | 46.3 ± 0.6 | 46.2 ± 0.6 |

| Middle | 214 (46.8) | 45.3 ± 0.5 | 44.6 ± 0.5 | 45.7 ± 0.6 | |

| High | 30 (6.6) | 45.2 ± 1.3 | 44.8 ± 1.7 | 46.8 ± 1.6 | |

| (df = 2) | F | 2.040 | 2.190 | 0.324 | |

| P | 0.131 | 0.113 | 0.723 | ||

| Parental status | Both parents | 400 (86.8) | 45.9 ± 0.3 | 45.4 ± 0.4 | 45.9 ± 0.4 |

| Father only | 27 (5.8) | 46.2 ± 1.8 | 44.3 ± 2.0 | 47.7 ± 1.8 | |

| Mother only | 34 (7.4) | 46.5 ± 1.4 | 46.1 ± 1.8 | 45.1 ± 1.3 | |

| (df = 2) | F | 0.074 | 0.322 | 0.710 | |

| P | 0.928 | 0.725 | 0.492 |

Data are presented as mean±standard error. Duncan's post-hoc test was used. *Student subgroup report lower anxiety and depression score than jobless subgroup. Employed subgroup showed no significant difference with the other two subgroups; †College student group report lower depression score than high school education subgroup. df, degree of freedom; KMPT, Korea Military Personality Test.

Correlation between ELS, resilience and psychopathology

Depression and anxiety severity were correlated with education level, and job status. ELS experience was positively correlated with depression, anxiety, and aggression but almost resilience factors showed significant negative correlations with anxiety, depression, and aggression as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Correlation of early-life stress and resilience factors scores with depression, anxiety and aggression in the KMPT (n = 461).

| Variables | Depression | Anxiety | Aggression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | r | P | ||

| Demographics | Age | 0.053 | 0.252 | 0.014 | 0.796 | 0.010 | 0.828 |

| Education level | -0.118 | 0.012 | -0.104 | 0.026 | -0.055 | 0.244 | |

| Job | -0.114 | 0.014 | -0.130 | 0.005 | -0.089 | 0.055 | |

| ELS resilience factors | Total ELS score | 0.224 | < 0.001 | 0.196 | < 0.001 | 0.201 | < 0.001 |

| Emotion regulation | -0.470 | < 0.001 | -0.511 | < 0.001 | -0.388 | < 0.001 | |

| Impulse control | -0.317 | < 0.001 | -0.390 | < 0.001 | -0.283 | < 0.001 | |

| Optimism | -0.460 | < 0.001 | -0.455 | < 0.001 | -0.296 | < 0.001 | |

| Causal analysis | -0.354 | < 0.001 | -0.401 | < 0.001 | -0.296 | < 0.001 | |

| Empathy | -0.240 | < 0.001 | -0.289 | < 0.001 | -0.198 | < 0.001 | |

| Self-efficacy | -0.431 | < 0.001 | -0.493 | < 0.001 | -0.171 | < 0.001 | |

| Reaching out | -0.376 | < 0.001 | -0.448 | < 0.001 | -0.032 | 0.487 | |

The significant correlation coefficient of variables in the correlation analyses are shown in bold. ELS, early-life stress; KMPT, The Korea Military Personality Test.

Modulation effect of resilience factors on the relationship between ELS and psychopathology

Table 3 presents the data explaining association of depression with other variables including demographics, ELS and resilience factors. The regression model for depression considering demographic variables, ELS, and resilience factors was significant and explained 35.8% of the total variance in the DEP scores. Even though ELS scores showed significant association in the second step, only resilience factor scores including ER, OP, and RO factors were significantly associated with reducing depressive symptom scores. Interaction effect was significant between ELS and ER.

Table 3. Modulating effect of resilience factors on the relationship between early-life stress and depression.

| Variable | 1st step | 2nd step | 3rd step | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | ||

| Demographics | Age | 0.064 | 1.371 | 0.034 | 0.877 | 0.040 | 1.037 |

| Education level | -0.082 | -1.462 | -0.092 | -1.978* | -0.089 | -1.897 | |

| Job | -0.073 | -1.296 | 0.001 | 0.031 | -0.012 | -0.267 | |

| ELS resilience ractors | Total ELS score | 0.163 | 4.201† | 0.124 | 1.212 | ||

| Emotion regulation | -0.294 | -5.639† | -0.218 | -3.694† | |||

| Impulse control | -0.048 | -1.008 | -0.093 | -1.524 | |||

| Optimism | -0.213 | -4.290† | -0.228 | -3.6897† | |||

| Causal analysis | 0.004 | 0.084 | -0.024 | -0.363 | |||

| Empathy | 0.138 | 2.852† | 0.109 | 1.807 | |||

| Self efficacy | -0.110 | -1.982* | -0.040 | -0.563 | |||

| Reaching out | -0.152 | -3.254† | -0.201 | -3.486† | |||

| ELS × ER | -0.179 | -2.243* | |||||

| ELS × IC | 0.056 | 0.773 | |||||

| ELS × OP | 0.043 | 0.587 | |||||

| ELS × CA | 0.082 | 1.053 | |||||

| ELS × EM | 0.085 | 0.760 | |||||

| ELS × SE | -0.148 | -1.701 | |||||

| ELS × RO | 0.093 | 1.107 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.015 | 0.350 | 0.358 | ||||

| F | 3.365* | 23.207† | 15.071† | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.022 | 0.344 | 0.018 | ||||

| ΔF | 3.365 | 29.998 | 1.817 | ||||

*P<0.05; †P<0.01 (two-tailed). ELS, early-life stress; ER, emotion regulation; IC, impulse control; OP, realistic optimism; CA, causal analysis; EM, empathy; SE, self-efficacy; RO, reaching out.

The regression model for anxiety was also significant and explained 41.0% of the total variance in the AX scores. In this model, ELS experience was also significant only in the second step. When adding resilience factors to the model, ELS effect was not significant but ER, IC, OP, and RO factors were inversely associated with anxiety. Interaction effect between ELS and resilience factors was significant only between ELS and SE as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Modulating effect of resilience factors on the relationship between early-life stress and anxiety.

| Variables | 1st step | 2nd step | 3rd step | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | ||

| Demographics | Age | 0.019 | 0.406 | -0.003 | -0.087 | 0.001 | 0.025 |

| Education level | -0.045 | -0.800 | -0.070 | -1.581 | -0.073 | -1.629 | |

| Job | -0.109 | -1.933 | -0.024 | -0.536 | -0.036 | -0.807 | |

| ELS resilience factors | Total ELS score | 0.128 | 3.445† | -0.003 | -0.033 | ||

| Emotion regulation | -0.298 | -5.964† | -0.237 | -4.188† | |||

| Impulse control | -0.110 | -2.420* | -0.152 | -2.607† | |||

| Optimism | -0.129 | -2.713† | -0.151 | -2.548* | |||

| Causal analysis | -0.009 | -0.171 | 0.002 | 0.039 | |||

| Empathy | 0.122 | 2.637† | 0.056 | 0.974 | |||

| Self efficacy | -0.139 | -2.617† | -0.056 | -0.826 | |||

| Reaching out | -0.216 | -4.851† | -0.273 | -4.950† | |||

| ELS × ER | -0.139 | -1.824 | |||||

| ELS × IC | 0.058 | 0.843 | |||||

| ELS × OP | 0.042 | 0.590 | |||||

| ELS × CA | 0.008 | 0.103 | |||||

| ELS × EM | 0.194 | 1.823 | |||||

| ELS × SE | -0.164 | -1.970* | |||||

| ELS × RO | 0.113 | 1.409 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.013 | 0.404 | 0.410 | ||||

| F | 2.990* | 28.978† | 18.526† | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.020 | 0.399 | 0.015 | ||||

| ΔF | 2.990 | 37.988 | 1.641 | ||||

*P<0.05; †P<0.01 (two-tailed). ELS, early-life stress; ER, emotion regulation; IC, impulse control; OP, realistic optimism; CA, causal analysis; EM, empathy; SE, self-efficacy; RO, reaching out.

The regression model for aggression was also significant and explained 23.3% of total variance in the AGG scores. Aggression showed inverse relationships only with resilience factors including ER, IC, OP, and CA in the same way. Interaction effects were significant between ELS and ER, and CA factors as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Modulating effect of resilience factors on the relationship between early-life stress and aggression.

| Variables | 1st step | 2nd step | 3rd step | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | ||

| Demographics | Age | 0.010 | 0.205 | -0.009 | -0.207 | 0.001 | 0.036 |

| Education level | -0.003 | -0.058 | 0.011 | 0.218 | 0.027 | 0.525 | |

| Job | -0.093 | -1.649 | -0.056 | -1.090 | -0.088 | -1.712 | |

| ELS resilience factors | Total ELS score | 0.156 | 3.637† | 0.118 | 1.059 | ||

| Emotion regulation | -0.300 | -5.196† | -0.174 | -2.695† | |||

| Impulse control | -0.109 | -2.075* | -0.142 | -2.133* | |||

| Optimism | -0.178 | -3.235† | -0.203 | -3.006† | |||

| Causal analysis | -0.068 | -1.175 | -0.143 | -2.001* | |||

| Empathy | 0.074 | 1.379 | 0.014 | 0.211 | |||

| Self efficacy | 0.076 | 1.237 | 0.151 | 1.968 | |||

| Reaching out | 0.134 | 2.593* | 0.099 | 1.575 | |||

| ELS × ER | -0.318 | -3.647† | |||||

| ELS × IC | 0.029 | 0.372 | |||||

| ELS × OP | 0.071 | 0.879 | |||||

| ELS × CA | 0.187 | 2.186* | |||||

| ELS × EM | 0.180 | 1.481 | |||||

| ELS × SE | -0.167 | -1.760 | |||||

| ELS × RO | 0.047 | 0.511 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.03 | 0.202 | 0.233 | ||||

| F | 1.382 | 11.416† | 8.678† | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.009 | 0.212 | 0.043 | ||||

| ΔF | 1.382 | 15.050 | 3.629 | ||||

*P<0.05; †P<0.01 (two-tailed). ELS, early-life stress; ER, emotion regulation; IC, impulse control; OP, realistic optimism; CA, causal analysis; EM, empathy; SE, self-efficacy; RO, reaching out.

DISCUSSION

We found a significant attenuating effect of resilience against the ELS effect on the severity of psychopathology in this study. Even though ELS experience was positively associated with depression, anxiety, and aggression, ELS effect became insignificant when adding resilience factors in the final regression model. Among the resilience factors, ER factor showed the most beneficial effect on reducing severity of psychopathologies. Interaction effect with ELS scores was also significant. OP factor was also a significant protective factor for depression, anxiety, and aggression. CA factors showed a significant modulation effect for aggression.

ELS experience may contribute to develop psychopathology. Prolonged exposure to stressful life events during childhood and adolescence increases sensitivity to negative emotions such as anxiety and fear and induces changes in patterns of cognition, emotion, and behaviour, perhaps via alteration of brain development in such a way that vulnerability to psychopathology is increased (21). Inappropriate aggressive behaviours may be fostered by social deprivation and mediated via dysfunction of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin signalling (22). A multinational study of university students revealed that childhood neglect is associated with violence against dating partners later in life (23). Aggressive behaviour during adolescence and adulthood may be a long-term consequence of childhood physical abuse. A meta-analysis showed that witnesses to conjugal violence who also were physically abused have more emotional and behavioural problems than witnesses who were not physically abused (24). Other meta-analysis indicated that psychosocial outcomes of witnesses who were not physically abused are comparable to those of physically abused witnesses and physically abused non-witnesses (7).

Resilience is more important to maintain and promote mental health. Even though adversities, stress, or trauma, resilient people do not go on to exhibit serious psychopathology (13). Resilience may be related to neural networks underlying reward and motivation, fear responsiveness, and adaptive social behaviour (25) as well as a capacity for self-regulation including emotion regulation, interpersonal relationships, and psychological positivity or optimism. Positive affectivity, cognitive flexibility, coping, social support, and mastery may also be important resilience-related factors.

Emotion regulation is the critical component of resilience. It is often considered as a component of self-regulation in which effortful and voluntary processes are included (26). Emotion regulation is associated with increasing resilience in maltreated and non-maltreated children (27). Difficulty in regulating emotion may compromise the development of psychological well-being in children who have been maltreated or exposed to interparental violence (28).

Optimism is an especially important component of psychological resilience-related factors for facilitating psychological maturation after traumatic experiences (29,30). Optimism may be both a trait and a state characteristic. In a study of an internet-based intervention for patients suffering complicated grief, the treatment group exhibited significant posttraumatic growth but there was no treatment effect on optimism (31). In the present study, we found that reaching out, another resilience factor, had a protective effect against the development of emotional distress. Strengthening personal and social resource is another important aspect of resilience enhancement and prevention of mental illness (32).

Educational level and employment status also may modulate the development of psychopathology. In our study, unemployed, relatively less educated participants reported more depressive symptoms, although these effects were not statistically significant in the final regression model. Resilience can be developed through education or training programs. In a school-based randomized controlled study of a resilience enhancement program for teenagers, the program was associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms (33) and protection against depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assessed ELS using a self-report questionnaire, which depends on retrospective memories that are subject to distortion. However, in agreement with our findings, other prospective studies have found evidence for an association between ELS and mental disorders including depressive disorders and anxiety disorders later in life (34). In addition, a recent comparison study on childhood maltreatment found no difference in association strength between retrospective and prospective designs (35). Second, we did not conduct structured interviews for psychiatric diagnosis due to the limited number of researchers. We believe that the KMPT, a systematically developed and validated psychological test, provides sufficient information about psychopathology in examinees. Third, we gathered the data in a regional military manpower office. Hence, our study sample is not representative of the entire population of young adults in Korea, and our results of cannot be generalized to the national level or female population. Finally, the abuse experience questionnaire did not assess other stressful life events including disaster, bullying, and witnessing of death. Future studies should consider possible psychopathology-modulating effects of these types of stressful events in their early-life with standardized Korean inventories for early-life stress.

In summary, we found that resilience factors including emotion regulation and optimism may counteract the harmful effects of ELS for the development of psychopathology. In light of the burden of mental health problems including depression in our society at large, sophisticated programs for resilience enhancement should be developed for use in these populations with serious ELS experiences.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2013R1A1A2005546).

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study design: Kim J, Seok JH, Choi K. Data collection and analysis: Choi K, Lee E. Writing manuscript: Kim J, Seok JH, Choi K. Discussion and manuscript revision: Jon DI, Hong HJ, Hong N. Manuscript approval: Kim J, Seok JH, Choi K, Jon DI, Hong HJ, Hong NR, Lee E.

References

- 1.Giedd JN, Lalonde FM, Celano MJ, White SL, Wallace GL, Lee NR, Lenroot RK. Anatomical brain magnetic resonance imaging of typically developing children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:465–470. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pechtel P, Pizzagalli DA. Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:55–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duggan C, Sham P, Minne C, Lee A, Murray R. Quality of parenting and vulnerability to depression: results from a family study. Psychol Med. 1998;28:185–191. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggress Violent Behav. 2008;13:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Fitzmaurice G, Decker MR, Koenen KC. Witness of intimate partner violence in childhood and perpetration of intimate partner violence in adulthood. Epidemiology. 2010;21:809–818. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f39f03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seok JH, Lee KU, Kim W, Lee SH, Kang EH, Ham BJ, Yang JC, Chae JH. Impact of early-life stress and resilience on patients with major depressive disorder. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:1093–1098. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.6.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunday S, Kline M, Labruna V, Pelcovitz D, Salzinger S, Kaplan S. The role of adolescent physical abuse in adult intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:3773–3789. doi: 10.1177/0886260511403760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez CM. Parent-child aggression: association with child abuse potential and parenting styles. Violence Vict. 2010;25:728–741. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildyard KL, Wolfe DA. Child neglect: developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:679–695. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luthar SS, Brown PJ. Maximizing resilience through diverse levels of inquiry: Prevailing paradigms, possibilities, and priorities for the future. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:931–955. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner EE. Vulnerable but invincible: high risk children from birth to adulthood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;5:47–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00538544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reivich K, Shatte A. The resilience factor: Seven essential skills for overcoming life's inevitable obstacles. New York: Broadway Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Won HT, Han DW, Shin ES, Park KB, Lee YH, Yook SP. The final report on the development of Korea Military Personality Test. Seoul: Ministry of National Defense; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park DE, Yook SP. A study for screening effect and availability of the military personality test. J Korean Milit Med Assoc. 2004;35:157–169. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh HJ. Effects of childhood abuse and exposure to parental violence on problem drinking in later life. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University; 2004. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence : the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang HJ. The development of a child abuse assessment scale. Seoul, Korea: Sookmyung Women's University; 1998. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH. Resilience: pleasant secrets changing advesity into fortune. Koyang: Wisdomhouse; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry BD. The neurodevelopmental impact of violence in childhood. In: Schetky D, Benedek EP, editors. Textbook of child and adolescent forensic psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001. pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veenema AH. Early life stress, the development of aggression and neuroendocrine and neurobiological correlates: what can we learn from animal models? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:497–518. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straus MA, Savage SA. Neglectful behavior by parents in the life history of university students in 17 countries and its relation to violence against dating partners. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:124–135. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children's exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis and critique. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:171–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024910416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:195–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenberg N, Sulik MJ. Emotion-related self-regulation in children. Teach Psychol. 2012;39:77–83. doi: 10.1177/0098628311430172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis WJ, Cicchetti D. Emotion and resilience: a multilevel investigation of hemispheric electroencephalogram asymmetry and emotion regulation in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:811–840. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maughan A, Cicchetti D. Impact of child maltreatment and interadult violence on children's emotion regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment. Child Dev. 2002;73:1525–1542. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:255–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yehuda R, Flory JD, Southwick S, Charney DS. Developing an agenda for translational studies of resilience and vulnerability following trauma exposure. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:379–396. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner B, Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Post-traumatic growth and optimism as outcomes of an internet-based intervention for complicated grief. Cogn Behav Ther. 2007;36:156–161. doi: 10.1080/16506070701339713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wille N, Bettge S, Ravens-Sieberer U BELLA study group. Risk and protective factors for children's and adolescents' mental health: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17:133–147. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-1015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Freres DR, Chaplin TM, Shatté AJ, Samuels B, Elkon AG, Litzinger S, Lascher M, Gallop R, et al. School-based prevention of depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and specificity of the Penn Resiliency Program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:9–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott KM, Smith DR, Ellis PM. Prospectively ascertained child maltreatment and its association with DSM-IV mental disorders in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:712–719. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott KM, McLaughlin KA, Smith DA, Ellis PM. Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:469–475. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]