Abstract

Background

Structured care processes that provide a framework for how oncologists can incorporate geriatric assessment (GA) into clinical practice could improve outcomes for vulnerable older adults with cancer, a growing population at high risk of toxicity from cancer treatment. We sought to obtain consensus from an expert panel on the use of GA in clinical practice and to develop algorithms of GA-guided care processes.

Methods

The Delphi technique, a well-recognized structured and reiterative process to reach consensus, was used. Participants were geriatric oncology experts who attended NIH-funded U13 or Cancer and Aging Research Group conferences. Consensus was defined as an interquartile range of ≤2 units, or ≥66.7%, selecting a utility/helpfulness rating of ≥7 on a 10-point Likert scale. For nominal data, consensus was defined as agreement among ≥66.7% of the group.

Results

From 33 invited, 30 participants completed all three rounds. The majority of experts (75%) used GA in clinical care, and the rest were involved in geriatric oncology research. The panel met consensus that “all patients aged ≥75 years and those who are younger with age-related health concerns” should undergo GA and all domains (function, physical performance, comorbidity/polypharmacy, cognition, nutrition, psychological status, and social support) should be included. Consensus was met for how GA could guide non-oncologic interventions and cancer treatment decisions. Algorithms for GA-guided care processes were developed.

Conclusion

This Delphi investigation of geriatric oncology experts demonstrated that GA should be performed for older patients with cancer to guide care processes.

INTRODUCTION

Vulnerable older patients with cancer are at high risk for adverse outcomes, including serious toxicities from cancer treatments.1,2 Despite a dramatic increase in the number of new cancer diagnoses in older patients projected over the next 20 years,3 there is a critical gap in knowledge regarding how to improve outcomes for these patients.4,5 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend a geriatric assessment (GA) for older (≥65 years) patients with cancer to identify health status issues that increase the risk of adverse outcomes.6 A GA is a comprehensive evaluation of a patient’s physical, functional, social, and psychological well-being that predicts morbidity and mortality in community-dwelling older adults.7 A GA can also predict chemotherapy toxicity and survival in patients with cancer.1,8–11 Although GA has been extensively studied, incorporating GA results into oncology clinical practice have not been standardized.

Most oncologists have received little training in the care of older patients.12 The development of structured care processes that provide a framework for how oncologists can incorporate GA into clinical practice could improve outcomes of vulnerable older adults with cancer.13 Care processes refer to the tasks done to and for the patient by practitioners during treatment. Outcome measures are the desired states resulting from care processes, which may include reduction in morbidity and mortality and improvement in quality of life. In geriatric oncology, care processes utilize GA in two distinct, but related, ways. First, GA is used to identify specific evidence-based geriatric interventions to be implemented, such as ordering physical therapy (PT) for a patient with mobility deficits. Second, GA is used to guide cancer treatment decisions, such as modification of chemotherapy dosing in a patient with physical or functional impairments. Thus, a “GA-guided care process” is the use of GA to select targeted geriatric interventions and to guide choices for cancer treatment.

The U13 conferences, “Geriatric Oncology Research to Improve Clinical Care,” sponsored by the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) and the National Institute of Health (NIH, U13 AG038151), have highlighted the need for developing GA-guided care processes that could be incorporated into oncology clinical practice.4–7,14 A dedicated group of geriatric oncology teams has developed clinical and research programs that utilize GA-guided care processes.15 The aim of this study was to obtain expert consensus, using a modified Delphi approach, from leaders in geriatric oncology in the United States (U.S.) on how to best to translate information from GA into care processes (interventions and treatment decisions) for older cancer patients.

METHODS

The Delphi method is a flexible iterative survey process with the goal of transforming individual opinions into a group consensus on issues where the exact solutions are unknown.16,17 In this study, a three round Delphi process was performed consisting of brainstorming, narrowing down, and quantification of the opinions of expert participants. Data were collected and stored in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a software toolset for electronic collection and management of research data.18 University of Rochester provided IRB approval of the study.

Expert Panel Selection and Recruitment

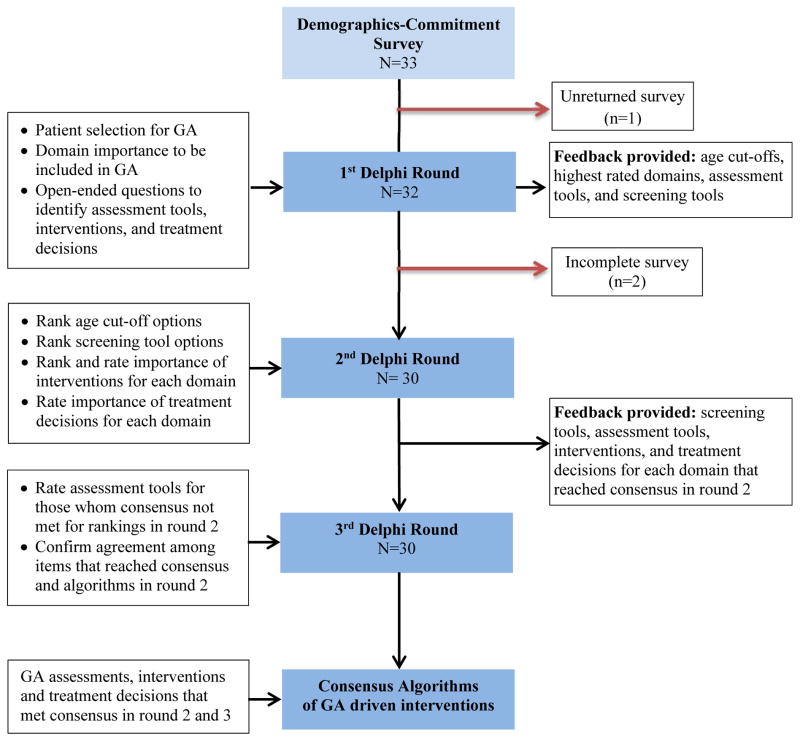

Participants included researchers, oncologists, and geriatricians who attended the geriatric oncology U13 conferences.4,5 Participants had to be located in the U.S., have research or clinical interests in geriatric oncology, and be two or more years from fellowship. Experts were contacted via e-mail, with a link to a survey with three parts: a consent form, a demographics section, and a commitment agreement that explained the importance of their continued participation throughout the Delphi process. Participants who consented were sent the first round (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Delphi Process to Reach Consensus.

A standard Delphi process was used to reach consensus over three rounds. Items that did not meet consensus during round two were sent back to the panel to reach consensus. Qualitative questions were used in the first round, and quantitative questions were used in the second and third rounds.

Study Procedures and Analysis

The three Delphi rounds were sent to participants eight to twelve weeks apart. Round 1 (R1) started on 8/16/2012 and Round 3 (R3) ended on 7/30/2013. All responses were quasi-anonymous in that the participants might know the group composition given attendance at a common conference, but could not identify response to any given participant. Similarly, data analysts were blinded to the identity of participants. A flow chart illustrating the Delphi process is shown in Figure 1.

In R1, participants rated the importance of particular domains to be included in a full GA as well as to develop criteria to determine who should get the full GA. Participants answered open-ended questions to identify screening tools and high priority interventions that should be implemented based on GA results. In round two (R2), participants rated the criteria and screening tools for selecting patients for GA, assessments for each domain, and GA-guided care processes. Areas of agreement and disagreement helped inform R3. Between rounds, group responses were quantified, summarized and re-presented to the panel, along with individual responses. Panelists were asked to either confirm their agreement on items that met consensus or provide reasons for responses remaining outside consensus. After R3, the analysis team finalized the algorithms for each GA domain.

In concordance with previous work, p predetermined threshold for consensus was chosen: an interquartile range (IQR) of ≤2 units or ≥66.7% providing a utility or helpfulness rating of ≥7 on a 10 point Likert scale.17 For nominal data, consensus was defined as agreement among ≥66.7% of the group. Data in REDCap were exported to SAS 9.3 and Excel worksheets for statistical analysis.

CONSENSUS FINDINGS

Demographics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Delphi participants (N=30)

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, range) | 46 (35–71) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23 (77%) |

| Asian | 5 (17%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3%) |

| African American | 1 (3%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 18 (60%) |

| Male | 12 (40%) |

| Years in Practice Post Fellowship (mean, range) | 12 (2–41) |

| Both a clinician and researcher | 20 (67%) |

| Board-certified in geriatric medicine | 16 (53%) |

| Funded to do research in geriatric oncology | 21 (70%) |

| Institution has an outpatient clinic in geriatrics | 23 (77%) |

| Institution has a designated outpatient clinical program for older cancer patients | 16 (53%) |

| Institution has a dual training program in geriatrics and oncology | 8 (27%) |

| Have forum to present geriatric oncology research concepts | 17 (57%) |

Notes:

Data are presented as number and percentage unless otherwise indicated.

Of 33 invited, 30 participants completed R1–3; two participants completed R1 only. The majority (75%) use GA in clinical care. The expert panel was primarily White, non-Hispanic (77%) and female (60%), with an average of 12 years in practice post-fellowship. Most had funding to conduct geriatric oncology research (70%).

Selection Criteria for Full GA (Table 2)

Table 2.

Usefulness of Age cut-offs vs. Screening Tools to Select Patients for GA (N=30)

| Age Cut-Off | IQRa | % of panelb |

|---|---|---|

| All patients aged 75 and over and those who are younger with age-related issues or concerns | 1 | 93% |

| All patients aged 70 and over and those who are younger with age-related issues or concerns | 4 | 60% |

| Screening Tool | ||

| Functional Status | 3 | 64% |

| VES-13 | 1 | 59% |

| Objective Physical Performance | 2 | 59% |

| Self-rated health | 5 | 48% |

| CARG | 2 | 48% |

| Karnofsky Performance | 4 | 39% |

| ECOG Performance | 4 | 36% |

| G8 | 2 | 35% |

| CRASH | 1 | 34% |

| Groningen Frailty Index | 4 | 24% |

| Age Cut-Offs vs Screening Tools | ||

| All patients aged 75 and over and those who are younger with age-related issues or concerns | 1 | 100% |

| Screening tools where consensus was met (VES-13, objective physical performance, CARG, and CRASH) | 3 | 89% |

| All patients aged 70 and over and those who are younger with age-related issues or concerns | 4 | 56% |

Notes:

IQR= Interquartile range, or the 75th percentile minus the 25th percentile. Consensus defined as ≤ 2 units.

Percent of respondents that chose a usefulness rating of 7 or higher for that item, where 0= not at all useful and 10= most useful. Consensus defined as ≥ 66.7%.

At the completion of R3, 73% of the panelists agreed there should be an age cut-off to establish a standard for which patients should get a full GA. When required to choose an age cut-off, 93% of panels rated “All patients aged 75 and over and those who are younger with age-related issues or concerns” highly for getting a full GA (IQR=1, meeting consensus). Ninety percent of the panelists agreed that screening with a short geriatric-based tool should be instituted in oncology clinics to determine who should get a full GA.19 However, opinion varied regarding which screening tool was best to use. In this U.S. based sample, the Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (VES-13),20 CARG1 and Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH)8 chemotherapy risk tools and objective physical performance (no specific test) all met consensus by IQR criteria but not by rating criteria.

Geriatric Assessment Domains and Specific Measures (Table 3)

Table 3.

Utility of Assessment Tools for Incorporation in Geriatric Assessment that Met Consensus (N=30)

| Domain | Assessment | IQRa | % of panelb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both ADL/IADL | 2 | 93% | |

| Functional Status | Gait Speed | 2 | 90% |

| IADL | 2 | 80% | |

| ADL | 2 | 40% | |

| Mini Mental State Examination | 2 | 80% | |

| Cognition | Montreal Cognitive Assessment | 2 | 80% |

| Blessed OMC | 3 | 75% | |

| Caregiver burden/support | 2 | 87% | |

| Social Support | Medical Outcomes Study Survey | 3 | 72% |

| Social Support from Medical History | 3 | 67% | |

| Gait Speed | 2 | 93% | |

| Objective Physical Performance | Timed Up and Go | 2 | 90% |

| Short Physical Performance Battery | 3 | 85% | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 3 | 83% | |

| Psychological Status | Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale | 3 | 72% |

| Mental Health Inventory | 2 | 63% | |

| Nutrition | Weight loss | 1 | 90% |

| Mini-Nutritional Assessment | 3 | 79% |

Notes:

IQR= Interquartile range, or the 75th percentile minus the 25th percentile. Consensus defined as ≤2 units.

Percent of respondents that chose a utility rating of 7 or higher for that item, where 0=not at all important and 10= the most important. Consensus defined as ≥66.7%.

Participants reached consensus on all domains to be included in GA (each with IQR=2 or less and a mean rating of 8.8 or higher out of 10.0). These domains included functional status, cognition, social support, objective physical performance, psychological status (anxiety and depression), nutrition, comorbidity and polypharmacy. Consensus was often met for more than one tool to assess each domain in clinical practice as part of a GA. The highest rated tools21 were as follows: Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living for functional status (ADLs and IADLs), gait speed and “Timed Up and Go” (TUG) for physical performance, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depression, weight loss for nutritional status, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for cognition.21

GA-guided Care Processes

Several high priority care processes for each geriatric domain reached consensus (Table 4). GA-guided interventions are illustrated in Figure 2 as algorithms that can be followed for impairments in each of the domains.

Table 4.

Importance of Interventions and Treatment Decisions that met Consensus (N=30)

| Interventions for Domain Impairment | IQRa | % of panelb | Changes to Treatment decisions | IQRa | % of panelb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Status | |||||

| Physical Therapy | 2 | 97% | Modify treatment regimen | 2 | 93% |

| Occupational Therapy | 2 | 89% | Evaluate fall risk | 2 | 92% |

| Home Safety Evaluation | 2 | 86% | Assure presence of social support | 2 | 85% |

| Evaluate Fall Risk | 3 | 81% | Improve functional status prior to treatment | 2 | 78% |

| Refer to social work | 2 | 80% | Avoid aggressive therapy | 3 | 74% |

| Exercise | 3 | 79% | Recommend personal emergency response service | 3 | 65% |

| Cognition | |||||

| Involve caregiver | 1 | 100% | Make sure caregiver is involved and present with patient | 1 | 100% |

| Assess/minimize medications | 2 | 100% | Assess safety of treatment | 2 | 96% |

| Delirium prevention | 2 | 97% | Limit complexity of treatment | 3 | 96% |

| Refer to social work | 2 | 97% | Modify therapy delivery | 2 | 88% |

| Assess capacity and ability to consent to treatment | 2 | 89% | |||

| Identify health care proxy | 2 | 88% | Avoid aggressive therapy | 3 | 70% |

| Cognitive testing/Neuropsychology referral | 3 | 76% | |||

| Social Support | |||||

| Refer to social work | 1 | 100% | Assess patient safety/tolerability | 1 | 100% |

| Nursing/Home Health | 2 | 97% | Assess caregiver support | 2 | 96% |

| Transportation Assistance | 1 | 93% | Modify treatment regimen | 2 | 88% |

| Caregiver Management | 2 | 90% | Consider less aggressive treatment | 1 | 85% |

| Home Safety Evaluation | 3 | 76% | |||

| Support Groups | 2 | 64% | Modify therapy delivery | 1 | 84% |

| Spiritual Care | 2 | 50% | |||

| Psychiatry/Psychology | 2 | 45% | |||

| Objective Physical Performance | |||||

| Physical Therapy | 2 | 97% | Address safety during treatment | 2 | 93% |

| Exercise | 2 | 89% | Modify treatment regimen | 3 | 82% |

| Occupational Therapy | 2 | 89% | Consider less aggressive treatment | 2 | 77% |

| Home Safety Evaluation | 2 | 86% | Assess comorbidity/medication | 2 | 77% |

| Modify dosage of standard | 3 | 73% | |||

| Rehabilitation | 3 | 72% | Modify delivery of standard | 3 | 71% |

| Nursing/Home Health | 4 | 68% | |||

| Psychological Status – Anxiety/ Depressionc | |||||

| Refer to social work | 1 | 100% | |||

| Counseling | 2 | 100% | |||

| Refer to Psychiatry/Psychology | 1 | 85% | |||

| Support Programs | 2 | 82% | |||

| Start Medications | 2 | 81% | |||

| Spiritual Care | 2 | 56% | |||

| Nutrition | |||||

| Nutrition consult | 2 | 90% | Address supportive care | 2 | 89% |

| Make Specific Dietary Recommendations | 1 | 89% | Evaluate drug tolerance (e.g. dehydration) | 2 | 81% |

| Oral Care | 2 | 78% | Remediate malnutrition prior to treatment | 3.75 | 71% |

| Supplements | 2.75 | 75% | |||

| Refer to social work | 2 | 52% | Discuss alternate feeding routes for some cancers (e.g. H&N) | 4 | 67% |

| Physical/Occupational Therapy | 2 | 32% | |||

IQR= Interquartile range, or the 75th percentile minus the 25th percentile. Consensus defined as ≤2 units.

Percent of respondents that chose a utility rating of 7 or higher for that item, where 0=not at all important and 10= the most important. Consensus defined as ≥66.7%.

Changes to treatment decisions for Psychological Status (depression and anxiety) were not evaluated; this was removed a priori to reduce length of the survey

Figure 2. Algorithm of Geriatric Assessment Guided Processes.

Geriatric assessment domains are identified in the first column. For each domain, assessment options are listed in the middle column. For each group of assessment options, specific care processes are identified to address the identified needs in the last column. These care processes are presented numerically in order of highest IQR and % of panel participants that chose a utility rating of 7 or higher for that item.

GA-guided interventions addressing impaired domains that reached consensus included: 1) PT and occupational therapy (OT) for impaired function; 2) caregiver engagement and minimizing medications for impaired cognition; 3) social work and home health referrals for poor social support; 4) PT and exercise for impaired objective physical performance; 5) social work and counseling for depression and/or anxiety; and 6) nutrition consult and oral care for poor nutrition.

The panel also met consensus on ways that impairment in a specific geriatric domain could influence cancer treatment decisions. Treatment decision changes to address impaired domains that met consensus included: 1) modification of cancer treatment regimen and evaluation of fall risk for impaired functional status; 2) assessing the presence of a caregiver and limiting the complexity of treatment for patients with impaired cognition; 3) assessing patient safety/tolerability and assessing caregiver support for poor social support; 4) assessing safety of treatment for impaired physical performance; and 5) addressing supportive care and evaluating drug tolerance for poor nutritional status.

Generalizing interventions for comorbidity/polypharmacy in this format was not undertaken due to the numerous comorbidities and drug interactions that would need to be considered. Preliminary results indicate that the panel believes a review of history and physical/medical records (IQR=3, % of panel ≥7= 83%), the Charlson Comorbidity Index (IQR=2, % of panel ≥7= 59%), and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale in Geriatrics (IQR=3, % of panel ≥7=72%) as the most useful tools to assess impairments in comorbidity/polypharmacy. In an open-ended question in R1, 70% of panelists who responded identified pharmacists or primary care providers as essential in developing and co-managing interventions.

DISCUSSION

Although use of GA in clinical practice for older adults with cancer has been advocated, more evidence-based information is needed to improve outcomes of this population. To our knowledge, this research is the first in the U.S. that addresses, using a formal consensus process with geriatric oncology experts, how GA can guide care processes in oncology clinical practice.

GA identifies risk factors for adverse outcomes in older patients and adds information to standard oncology performance measures used, which were validated in younger patients.22 Multicenter studies have found that items included in a GA identifies older patients at greatest risk for chemotherapy toxicity and mortality.1,8–10 GA has been found to be feasible not only in community oncology clinics.1,23,24 The geriatric oncology expert panelists felt that all GA domains were important to include, and several validated tools met consensus, which is consistent with the growing geriatric oncology literature and other expert panels.21,25,26 Ultimately, the choice of which tool to use should rest on the question being asked, how GA results will be utilized (e.g., for research or clinical practice), and the resources available for implementation.

Controversy still exists regarding how best to select patients for GA in clinical practice. Careful selection of patients, for whom GA is beneficial, is important to guide the use of GA results to inform treatment decision for vulnerable older patients and to “spare” fit older patients from unnecessary testing. The NCCN guidelines for older adults recommend that all patients aged ≥65 receive a GA.6 In contrast, the expert panelists supported both an age-based criterion (all patients aged ≥75 and/or younger patients with age-related health issues) and the use of short, functionally based tools to screen patients for GA.6,21 The panel did not quite meet consensus on which screening tool to utilize. In this U.S. study, VES-13 and chemotherapy toxicity tools (e.g., CARG and CRASH) scored the highest in terms of usefulness. In the literature, G8 which was developed from the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and is more widely tested in Europe, has been shown in some settings to have higher sensitivity and specificity than VES-13 for identifying older patients who would benefit from GA.27–30 In one study of 1,967 patients, 71% had an abnormal G8 score warranting GA, and the G8 was more or equally sensitive than other screening instruments.29 Our results are consistent with previous conclusions from geriatric oncology experts: screening tools do not replace GA but are recommended for use in a busy practice in order to identify those patients in need of full GA.31

There is no evidence-based approach for how to implement GA-guided care processes in oncology clinical care. Benefits of non-oncologic GA-guided interventions include prevention of geriatric syndromes, recognition of cognitive deficits, prevention of hospitalizations and nursing home admissions, and overall improvement of quality of life.32–35 A limited number of studies has shown that GA-guided care processes are feasible to implement in oncology.23,36–38 The ELCAPA study found that the initial oncology treatment plan was modified in 21% of patients based upon GA conducted by a geriatrician-led multidisciplinary team.37 In addition, geriatric consultation led to other non-oncologic interventions including a change in prescribed medications (31%), social support assistance (46%), physiotherapy (42%), nutritional care (70%), psychological care (36%), and memory evaluation (21%). In a study by McCorkle et al.,39 geriatric nurse practitioners conducted GA and implemented interventions for older patients with cancer, and this led to a survival advantage in the intervention group. In a study by Goodwin et al., breast cancer patients in the group who received GA with interventions were significantly more likely to return to normal functioning than controls.40 Each of these studies suggests the value of GA-guided care processes for older cancer patients.

A review from Hamaker et al. summarizes the current state of the literature with regards to GA-guided care processes.41 Ten observational cohort studies met the inclusion criteria for high quality studies. Median sample size was 50 patients (range 15–1967), and samples were heterogeneous with regards to underlying type and stage of cancer. Although there was selection bias in who was referred for GA, the prevalence of impairment was high in all geriatric domains. Non-oncologic GA-guided interventions were common (≥70% in all but one study) and included social interventions (38%), medication management (37%), and nutritional interventions (26%). Psychological, mobility, and comorbidity interventions were recommended for approximately 20% of patients. Although each study reported an approach to care, it is not clear if any specific algorithm was followed that guided interventions for impairment for each geriatric domain.

In addition to non-oncologic GA-guided interventions, GA information affected oncologic treatment decision-making. In six of the ten studies in the Hamaker review, the initial treatment plan was modified in 39% of patients after GA evaluation.41 Considering all studies, two thirds resulted in less intensive treatment. Lowering the intensity of treatment recommended is likely an attempt to adjust treatment in patients who have impairments.7 Still, it is important to note that one third of cancer treatment decisions were changed to be more intensive. In a study by Chaibi, 45 of 161 (28%) of patients received more intensive cancer treatment as a result of GA.42 Using GA to guide treatment options in clinical trials for older and frailer individuals may help determine if modifications are appropriate. Various approaches for chemotherapy selection and dosing for older and/or frailer patients are supported by the literature.4 For example, the FOCUS-2 trial found that chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer was safe and efficacious in the older and/or frail patient if started at a 20% dose reduction with escalation as tolerated.43

There are limitations to take into consideration when interpreting the results. Expert consensus is not as rigorous as randomized controlled studies. Nevertheless, these results could inform and help guide future efforts to study the impact of care processes on outcomes of older patients with cancer. Because of funding limitations, only U.S. experts were included. A parallel effort included experts outside of the U.S.,44 and future work will examine the similarities and differences between expert opinion in different parts of the world. Although the experts did come to consensus regarding many treatment-related decisions, the recommendations were often vague (e.g., “modify treatment”) which likely reflects the limited data available.

Despite these limitations, this Delphi study provides specific information from expert consensus on how GA should guide non-oncologic interventions as well as oncology treatment decisions. The recommended algorithms, based on expert consensus, presented here need further validation, but they are a first step in standardizing a model of care delivery for vulnerable older patients with cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has stated that to improve quality of care, oncologists and patients should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of cancer-directed therapy for patients with a low performance status, who are not eligible for a clinical trial, and for whom there is no strong evidence supporting the clinical value of treatment.45 These issues commonly affect older adults, and GA can help to identify the risks of treatment in older, frailer patients. In this study, experienced geriatric oncology experts came to consensus on how best to use GA to guide both non-oncologic and oncologic decisions. These recommendations can be incorporated into clinical oncology practice, including academic centers that are investing in new geriatric oncology programs. Several multicenter studies are underway to evaluate the effect of a multicomponent intervention using these algorithms on adverse clinical events and patient-reported outcomes. Until those results are known, these expert consensus positions provide our best evidence for GA-guided care processes for older cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute (U13 AG038151 from the National Institute on Aging and National Cancer Institute (NCI; National Institutes of Health); R03 AG042342 U10CA37420 and R01 CA177592). The work was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (4634). The work was also funded by the Susan H Green Memorial Grant (to Magnuson) and by the philanthropic donation of Sandy Lloyd to the Geriatric Oncology Program at the James Wilmot Cancer Institute.

The authors wish to thank all the mentioned experts for their valuable time and inputs to the study: Andrew Artz, Arti Hurria, Beatriz Korc-Grodzicki, Stuart Lichtman, Aanand Naik, Lodovico Balducci, Andrew Chapman, Louise Walter, Arati Rao, Martine Extermann, Cary Gross, Martine Puts, Cynthia Owusu, Miriam Rodin, Efrat Dotan, Mary Sehl, Ajeet Gajra, N A Jackson McCleary, Abdo Haddad, Dale Shepard, Harvey Cohen, Sarah Kagan, Holly Holmes, Supriya Mohile, Heidi Klepin, William Tew, Hyman Muss, Tanya Wildes, Ilene Browner, Gjisberta Vanlonden, James Wallace, and William Dale.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions were as follows: SGM was involved in the literature search, figures, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing. CV was involved in the literature search, figures, study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing; AH was involved in the study design, data interpretation, and writing (editing manuscript); AM was involved in the literature search, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing; LL was involved in the data interpretation and writing of the manuscript; CP was involved in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and final manuscript approval; AO was involved in the study design and data interpretation; RGB was involved in the study design, methods on the Delphi technique; and WD was involved in the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Presented as an oral presentation at the “International Society of Geriatric Oncology” annual meeting in September of 2013.

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP, Lichtman SM, Gajra A, Bhatia S, Katheria V, Klapper S, Hansen K, Ramani R, Lachs M, Wong FL, Tew WP. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurria A. Chemotherapy and toxicity assessment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(Suppl 1):S2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal SK, Hurria A. Impact of age, sex, and comorbidity on cancer therapy and disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(26):4086–4093. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, Rowland JH, Ballman KV, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Schilsky RL, Ferrell B, Extermann M, Schmader KE, Mohile SG. Designing Therapeutic Clinical Trials for Older and Frail Adults With Cancer: U13 Conference Recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale W, Mohile SG, Eldadah BA, Trimble EL, Schilsky RL, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Schmader KE, Ferrell B, Extermann M, Nayfield SG, Hurria A Cancer Aging Research G. Biological, clinical, and psychosocial correlates at the interface of cancer and aging research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(8):581–589. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurria A, Mohile SG, Dale W. Research priorities in geriatric oncology: addressing the needs of an aging population. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(2):286–288. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohile S, Dale W, Hurria A. Geriatric oncology research to improve clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(10):571–578. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, Lyman GH, Brown RH, DeFelice J, Levine RM, Lubiner ET, Reyes P, Schreiber FJ, 3rd, Balducci L. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3377–3386. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanesvaran R, Li H, Koo KN, Poon D. Analysis of prognostic factors of comprehensive geriatric assessment and development of a clinical scoring system in elderly Asian patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3620–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildes TM, Ruwe AP, Fournier C, Gao F, Carson KR, Piccirillo JF, Tan B, Colditz GA. Geriatric assessment is associated with completion of chemotherapy, toxicity, and survival in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, Kritchevsky SB, Williamson JD, Pardee TS, Ellis LR, Powell BL. Geriatric assessment predicts survival for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(21):4287–4294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurria A, Balducci L, Naeim A, Gross C, Mohile S, Klepin H, Tew W, Downey L, Gajra A, Owusu C, Sanati H, Suh T, Figlin R. Mentoring junior faculty in geriatric oncology: report from the Cancer and Aging Research Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3125–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohile S, Dale W, Magnuson A, Kamath N, Hurria A. Research priorities in geriatric oncology for 2013 and beyond. Cancer Forum. 2013;37(3):216–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNeil C. Geriatric oncology clinics on the rise. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(9):585–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch L, Ravasco P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, Baracos VE. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, Wedding U, Basso U, Colloca G, Rostoft S, Overcash J, Wildiers H, Steer C, Kimmick G, Kanesvaran R, Luciani A, Terret C, Hurria A, Kenis C, Audisio R, Extermann M. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendationsdagger. Ann Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luciani A, Ascione G, Bertuzzi C, Marussi D, Codeca C, Di Maria G, Caldiera SE, Floriani I, Zonato S, Ferrari D, Foa P. Detecting disabilities in older patients with cancer: comparison between comprehensive geriatric assessment and vulnerable elders survey-13. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2046–2050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M, Falandry C, Artz A, Brain E, Colloca G, Flamaing J, Karnakis T, Kenis C, Audisio RA, Mohile S, Repetto L, Van Leeuwen B, Milisen K, Hurria A. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, Zuckerman EL, Cohen HJ, Muss H, Rodin M, Panageas KS, Holland JC, Saltz L, Kris MG, Noy A, Gomez J, Jakubowski A, Hudis C, Kornblith AB. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, Kornblith AB, Barry W, Artz AS, Schmieder L, Ansari R, Tew WP, Weckstein D, Kirshner J, Togawa K, Hansen K, Katheria V, Stone R, Galinsky I, Postiglione J, Cohen HJ. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1290–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Springall E, Alibhai SM. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(15):1133–1163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puts MT, Santos B, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Atenafu EG, Springall E, Alibhai SM. An update on a systematic review of the use of geriatric assessment for older adults in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):307–315. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baitar A, Van Fraeyenhove F, Vandebroek A, De Droogh E, Galdermans D, Mebis J, Schrijvers D. Evaluation of the Groningen Frailty Indicator and the G8 questionnaire as screening tools for frailty in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamaker ME, Mitrovic M, Stauder R. The G8 screening tool detects relevant geriatric impairments and predicts survival in elderly patients with a haematological malignancy. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-2001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenis C, Bron D, Libert Y, Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Scalliet P, Cornette P, Pepersack T, Luce S, Langenaeken C, Rasschaert M, Allepaerts S, Van Rijswijk R, Milisen K, Flamaing J, Lobelle JP, Wildiers H. Relevance of a systematic geriatric screening and assessment in older patients with cancer: results of a prospective multicentric study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(5):1306–1312. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenis C, Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, De Greve J, Conings G, Milisen K, Flamaing J, Lobelle JP, Wildiers H. Performance of two geriatric screening tools in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(1):19–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):e437–444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodin MB, Mohile SG. A practical approach to geriatric assessment in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1936–1944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, Alessi CA, Bula CJ, Gold MN, Yuhas KE, Nisenbaum R, Rubenstein LZ, Beck JC. A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1184–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C, Pennypacker L, Smith DM, Ainslie N, Hornick T, Brodkin K, Lavori P. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, Cohen HJ. Geriatric evaluation and management units in the care of the frail elderly cancer patient. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(6):798–803. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caillet P, Canoui-Poitrine F, Vouriot J, Berle M, Reinald N, Krypciak S, Bastuji-Garin S, Culine S, Paillaud E. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in the decision-making process in elderly patients with cancer: ELCAPA study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3636–3642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingram SS, Seo PH, Martell RE, Clipp EC, Doyle ME, Montana GS, Cohen HJ. Comprehensive assessment of the elderly cancer patient: the feasibility of self-report methodology. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(3):770–775. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, Adler DC, Cooley ME, Jepson C, Lusk EJ, Torosian M. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1707–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin JS, Satish S, Anderson ET, Nattinger AB, Freeman JL. Effect of nurse case management on the treatment of older women with breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1252–1259. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamaker ME, Schiphorst AH, ten Bokkel Huinink D, Schaar C, van Munster BC. The effect of a geriatric evaluation on treatment decisions for older cancer patients--a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(3):289–296. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.840741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaibi P, Magne N, Breton S, Chebib A, Watson S, Duron JJ, Hannoun L, Lefranc JP, Piette F, Menegaux F, Spano JP. Influence of geriatric consultation with comprehensive geriatric assessment on final therapeutic decision in elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79(3):302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seymour MT, Thompson LC, Wasan HS, Middleton G, Brewster AE, Shepherd SF, O'Mahony MS, Maughan TS, Parmar M, Langley RE. Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): an open-label, randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1749–1759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Donovan A, Mohile S, Leech M. Expert Consensus Panel on Geriatric Assessment Interventions in Oncology. European Journal of Cancer Care. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12302. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, Blayney DW, Ganz PA, Mulvey TM, Wollins DS. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1715–1724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]