Abstract

Health behavior change (HBC) refers to facilitating changes to habits and/or behavior related to health. In healthcare practice, it is quite common that the interactions between practitioner and patient involve conversations related to HBC. This could be mainly in relation to the practitioner trying to directly persuade the patients to make some changes in their health behavior. However, the patients may not be motivated to do so as they do not see this change as important. For this reason, direct persuasion may result in a breakdown of communication. In such instances, alternative approaches and means of indirect persuasion, such as empowering the patient and their family members, could be helpful. Furthermore, there are several models and/or theories proposed which explain the health behavior and also provide a structured framework for health behavior change. Many such models/approaches have been proven effective in facilitating HBC and health promotion in areas such as cessation of smoking, weight loss and so on. This paper provides an overview of main models/theories related to HBC and some insights into how these models/approaches could be adapted to facilitate behavior change in hearing healthcare, mainly in relation to: i) hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake; and ii) hearing conservation in relation to music-induced hearing loss (MIHL). In addition, elements of current research related to this area and future directions are highlighted.

Key words: health behavior change, health promotion, hearing help-seeking, hearing-aid uptake, music induced hearing loss, hearing loss, hearing impairment.

Introduction

In simple words, change refers to starting doing something we are not doing, to stop doing something we are doing and/or to do something in a different way. The process of change has been studied extensively and it is believed that the change related to problematic behaviors may occur in many stages (i.e. model of stages of change) which may include: pre-contemplative, contemplative, deterministic, active change, maintenance, and relapse.1 In addition, it is believed that a person only has the ability to change if they really want to and only if they think they can (i.e. self-efficacy).

Health behavior change (HBC) refers to facilitating changes to habits and/or behavior related to health. In healthcare practice, it is quite common that the interactions between practitioner and patient involve conversations related to HBC. In some cases, this could be related to the practitioner trying to directly persuade the patients to make some changes in their health behavior. However, if the patient is not motivated and does not see this change as important, this approach of direct persuasion may result in a breakdown of communication. These problems are usually attributed to patient's unwillingness and lack of motivation. More importantly, the patients may not progress with the treatment/management process. However, it is believed that quite often this can be related to How they were approached? and How they were spoken to? Some experienced clinicians and researchers (e.g. Rollnick, Mason and Butler2) argue that, during such instances, to some extent the culprit may be the approach of direct persuasion adopted by practitioners. For this reason, alternative approaches and ways of indirect persuasion, such as empowering the patient and their family members, and motivational interviewing could be helpful.3

There are several models and/or theories proposed which explain the health behavior, which also provide a structured framework for facilitating the health behavior change. Such approaches have been proven effective in areas such as cessation of smoking, weight loss, reducing alcohol consumption, healthy eating, and so on.2–5 Some recent review papers including those by Nieuwenhuijsen et al.6 and Ravensloot et al.7 provide good overviews of HBC models/theories and their relevance to rehabilitation. The present paper provides an overview of main models/theories related to HBC and some insights into how these models/approaches could be adapted to facilitate behavior change in hearing healthcare, mainly in relation to: i) hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake; and ii) hearing conservation in the context of music-induced hearing loss (MIHL). In addition, elements of current research related to this area and future directions are highlighted.

Models/theories of health behavior change

The health behavior research literature provides some useful insights into how this process of persuading the patients can be done clinically in simple steps. In general, it is clear that there is no magic bullet to break this resistance or barrier. However, alternative approaches such as advising on strategies, motivational interviewing,3 empowering the patients and their family members, and indirect persuasion by creating intrinsic motivation can be helpful.8 Few models of HBC seem to explain the reasons for resistance and lack of motivation towards behavior change. Moreover, some of them have been found to be effective in facilitating HBC. Table 1 provides information about the main HBC models/theories and their underlying principles.

Table 1. Health behavior change models/theories and their underlying principles.

| Health behavior change models/theories | Underlying principles |

|---|---|

| Transtheoretical model (i.e. Stages of Change)9 | This model is based on the underlying principle that behavior change is achieved via various stages and focuses on individual's readiness to make a change |

| Health belief model10 | Identifies five important factors (i.e. perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, health motivation) that may influence an individual's decision to proactive health behavior |

| Protection motivation theory11 | Outlines the cognitive responses resulting from fear appeals (which can be due to various environmental and interpersonal factors) and can be applied in persuasive communication |

| Theory of reasoned action12 | This model is based on the underlying principle that there are three constructs (i.e. individual's attitude and perceived control over the behavior and the subjective norms) which may influence the plans for changes to risky behavior |

| Theory of planned behavior13 | This is an extension of Theory of reasoned action with an added construct of perceived behavior control (i.e, self-efficiency - importance of beliefs in one's own ability to perform) |

| Self-determination theory8 | Focuses on the individual's psychological needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness which may help to identify different motivators for predicting health behavior and for the maintenance of behavior change |

| Social cognitive theory (i.e. Interpersonal-level theories)14 | Attempts to predict behavior by measuring the interactions that take place within an individual's social environment |

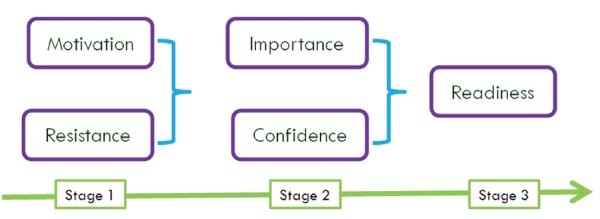

These theories/models provide a structured framework for thinking and understanding about various fields of HBC. More importantly, they provide simple steps/goals to work on to initiate behavior change in clinical situations. In general, the key tasks in consultation towards HBC may include: building rapport, setting an agenda, exploring multiple behaviors and considering one behavior for immediate change, assessment of importance, confidence and resistance, and finally to explore the importance of HBC and to build confidence.2 In addition, throughout this process the practitioner must exchange information with patients and work on reducing the resistance. However, this process can be seen in the three simple stages, as shown in the Figure 1, which may include: assessing the motivation and resistance in the first stage, exploring the importance and building confidence in the second stage, and assessing the readiness and initiating the HBC in the final stage.

Figure 1.

Simple stages to facilitate health behavior change.

The main uses of HBC models/theories are: i) to initiate a positive habit and/or behavior; and/or ii) to terminate a negative habit and/or behavior. Examples of effective use of HBC models can be seen in consultations related to various aspects including cessation of smoking,15,16 injury prevention,17 becoming more physically active, and/or change in eating habits for weight loss.18

Applications of health behavior change models in hearing healthcare

There are several areas in hearing healthcare in which HBC models/theories can be applicable. For example, parental counseling about treatment options for their hearing impaired child, to influence hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake in adults with hearing impairment, hearing conservation in the context of noise and music-induced hearing loss, tinnitus counseling, and so on. Table 2 identifies the key focus of a few papers in the area of hearing healthcare inrelation to use of HBC models/theories. However, in general, the literature on applications of HBC models/theories in hearing healthcare is rather limited. It is my belief that the following are the two areas that merit immediate considerations. This section provides some insights into why and how the aspects of HBC models/theories are applicable in these areas related to hearing healthcare.

Table 2. Key papers which suggest the use of health behavior change models/theories in hearing healthcare.

| Manuscript | Key focus in relation to health behavior change |

|---|---|

| Noh et al.19 | This paper provides an overview on how a theoretical model of HBC could have implications in audiological research and clinical practice. |

| Milstein and Weinstein20 | This work was aimed at exploring the effect of information sharing during hearing screening and how it may affect their compliance behavior towards hearing help-seeking. The authors briefly discussed the health belief model and used a readiness for change questionnaire in the study. |

| Babeu et al.21 | This paper provides a detailed overview on how a transtheoretical model of intentional behavior change could be incorporated into the delivery of audiological services. |

| Kaldo et al.22 | In this study the transtheoretical model has been used to develop Tinnitus Stages of Change Questionnaire (TSOCQ), which aims to access the readiness of tinnitus patients to change their behavior and their attitudes in relation to tinnitus. |

| Sobel and Meikle23 | This paper provides an overview of how various health behavior theories can be applied to a hearing conservation intervention program. |

| Rawool and Colligon-Wayne24 | The authors have used the health belief model to study the auditory lifestyle and belief of college students in relation to exposure to loud sounds. |

| Gilliver and Hickson25 | This study was aimed at understanding the attitudes of medical practitioners towards hearing rehabilitation of older adults. They developed a questionnaire to study this based on health belief model. |

HBC, health behavior change.

Hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake

Hearing impairment is known to be one of the most frequent sensory impairments and known to have consequences in physical, mental and social domains resulting in poor health related quality of life. The World Health Organization estimates there are 278 million people who have moderate to profound hearing impairment throughout the world.26 These numbers are expected to rise due to the increase in the elderly population. There are varieties of treatment and/or management options for hearing impairment, with hearing aids being the most frequently used and appropriate for most individuals with hearing impairment. Moreover, hearing aids have been found to be effective in reducing the negative effects of hearing impairment.27 However, in general, the evidence suggests that the hearing impairment is under recognized and under treated.28 Despite the known benefits of wearing a hearing aid, studies on hearing-aid uptake in developed countries show that only about 20% of those who could benefit from them use hearing aids.29 These figures could be even lower in developing countries, such as India, where the uptake of hearing aids is estimated to be between 1 to 8%.30 The help-seeking behavior and hearing-aid uptake could be related to various factors, including personal factors (e.g. source of motivation, expectation), demographic factors (e.g. age, gender), or external factors (e.g. cost, counseling).31

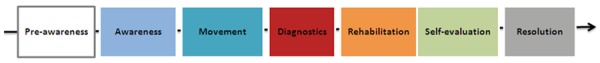

There are few approaches, such as informational counseling,32 motivational interviewing,33,34 shared decision making,35 which can help improve and facilitate help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake. However, there is a clear need for well controlled empirical studies to demonstrate the success of such approaches. In a recent study, Manchaiah et al. developed a patient journey template for adults with hearing impairment (Figure 2).36 The template defines seven main phases which include: pre-awareness, awareness, movement, diagnostics, rehabilitation, self-evaluation, and resolution. Moreover, Stephens and Kramer37 suggest that patients with hearing loss can be broadly categorized into 4 groups based on their rehabilitation types, which include: i) positively motivated without complicating factors; ii) positively motivated with complicating factors; iii) want help, but reject a key component; and iv) deny any problems. The patient journey model may help us to see these patients in the time domain. For example, the patients in category 3 could be in the movement and/or diagnostic phase and the patients in category 4 could be in pre-awareness phase.

Figure 2.

Main phases of the patient journey of adults with hearing impairment.22

Even though it appears that HBC in the hearing impaired population towards help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake can be initiated by working on transition or progression of patients in simple stages, there is no empirical evidence to support such an argument. In addition, Manchaiah et al. suggested that communication partners might play an important role in audiological enablement/rehabilitation of people with hearing impairment.38

These recent studies incorporate the simpler principles of the HBC models/theories described above. For example, the patient journey template can be related to Transtheoretical Model (i.e. Stages of Change) and involvement of communication partners that relate to social pressure as described in the Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action.

Hearing conservation in the context of music induced hearing loss

Listening to music is a very pleasant and enjoyable activity for most individuals. However, exposure to loud music for a significant duration either in a professional or recreational environment may cause hearing loss.39 In general, it is clear that exposure to loud music is one of the main recreational noise sources and the hearing loss due to music exposure has been referred to as MIHL).40 MIHL is known to be one of the fastest growing causes of hearing impairment. A study by Smith et al. indicates that noise exposure among adolescents in various social activities was approximately 18.8%, which is much higher than that from occupation noise and gunfire noise, which were 3.5 and 2.9%, respectively.41 It is the general consensus that many adolescents and young people are unaware of the dangers of exposure to loud music and how to reduce the risk of developing hearing loss, and they are at increased risk of developing MIHL due to increased music listening for leisure/entertainment purposes. A recent review paper by Zhao et al. suggested that, because the consequences are not immediate, it may be difficult for young people to perceive the seriousness of the problems related to MIHL.42 Moreover, the authors argued that conventional education may have little impact on raising awareness, and also that raised awareness of consequences of MIHL does not, in itself, lead to changes in their music listening behavior. These findings suggest that there is a need for new ways of educating and motivating adolescents and young adults to make changes to their listening habits. Such a need for hearing health education in young adults is also emphasised by Rawool and Colligon-Wayne.24

It is of vital importance that these groups are made aware of immediate and long-term dangers of MIHL. This can be achieved by increasing awareness and knowledge levels, motivating the individuals to change their attitude, behavior and music listening habits. However, this process can be facilitated by drawing ideas from HBC models/theories. Sobel and Meikle address the issue of applying health behavior theories to hearing conservation interventions.23 For example: i) applications of interpersonal theories in predicting the knowledge, attitude and beliefs which may help in altering the educational programmes related to hearing conservation; ii) applications of transtheoretical models to assess the individual's readiness to change; and iii) the five important factors described in the Health Belief Model may help in influencing the individuals to practice heath behavior.

Table 3 provides some insights into activities that may help in adapting HBC approach in hearing healthcare area such as: i) Hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake; and ii) hearing conservation of MIHL.

Table 3. Activities helpful in adapting health behavior change models in hearing healthcare.

| Hearing help-seeking and hearing-aid uptake | Hearing con- |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The key lessons which can be drawn from HBC models for use in hearing healthcare may include: promoting awareness about the disorder, understanding the predictive and/or influencing factors and using them in clinical situations to predict success of treatment/management, using cost-benefit analysis exercises during clinical consultations, motivational interviewing to create intrinsic motivations within patients, considering stages of change to facilitate a smooth transition in the patient's journey through the disease and its treatment regime, using social pressure (e.g. communication partners) to facilitate acceptance of the condition and its treatment, peer modeling, and adopting an individualistic approach to patient management. However, Bandura43 suggests that the self-efficacy of a person can be influenced by four main factors, which include: i) creating mastery experiences; ii) social models; iii) social persuasion; and iv) reducing stress reaction. Various elements discussed above in relation to HBC models relate to one or more of these four elements.

Even though various elements of HBC models seem appropriate, there are many constraints in adapting HBC models in hearing healthcare. This may include: i) limited research in this area related to hearing healthcare (i.e. understanding which models may be most effective in various aspects of hearing healthcare); ii) limited consultation time which makes it hard to spread the task of HBC in simple steps with achievable goals; and iii) limited training to hearing healthcare specialists about HBC resulting in limited clinical skills to facilitate HBC. For these reasons, it is important to develop creative ways of adopting HBC models for the applications to hearing healthcare. However, this can be possible by adopting new thinking among hearing healthcare clinicians and by research to consider alternative approaches to persuading patients about HBC. In addition, adapting new approaches to practice and mastering micro-skills (i.e. learning how to and how not to speak to patients about HBC), understanding the social construct of each individual (i.e. how different people perceive things differently) and tailoring the treatment/management approaches to suit them are important.

Final note

It is believed that the patient's knowledge of health conditions and their adverse effects does not in itself lead to changes to their health behavior. For this reason, it is important for healthcare practitioners to find ways of promoting health and facilitating HBC. There are several models and/or theories to explain health behavior change and many of them have been proven to be effective in facilitating HBC and health promotion in various health-related aspects of clinical situations. These models and approaches provide: i) a structured framework for thinking about and understanding patient's motivation and resistance to HBC; ii) predictive factors and/or indicators which may help practitioners to predict the outcome of the treatment/management; and iii) simple stages to effectively facilitate the HBC in clinical settings. Moreover, it appears that there are many elements of models that could be applied in hearing healthcare to facilitate HBC. However, more research is needed to understand which models and/or approaches are appropriate in facilitating HBC in various aspects related to hearing healthcare.

Acknowledgments:

the author likes to acknowledge Prof. Dafydd Stephens and Dr Lindsay St. Claire for their helpful comments on the manuscript. Elements of this paper were presented in the British Academy of Audiology (BAA) Conference during November 2011.

References

- 1.McNamara E. Motivational interviewing: the gateway to pupil self management. Pastoral Care Educ. 1992;10:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. Health behaviour change: a guide to practitioner. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WR, Rollnick S. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prochaska JO. A stage paradigm for integrating clinical and public health approaches to smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1996;21:721–32. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieuwenhuijsen ER, Zemper E, Miner KR, Epstein M. Health behaviour change model and theories: contributions to rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:245–56. doi: 10.1080/09638280500197743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravesloot C, Ruggiero C, Ipsen C, Traci M, Seekins T, Boehm T, et al. Disability and health behaviour change. Disabil Health J. 2011;4:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prochaska JO, Velicer WE. The transtheoretical model of health behaviour change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol. 1975;91:93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Dec. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Guadagnoli E, Rossi JS, DiClemente CC. Patterns of change: dynamic typology applied to smoking cessation. Multivar Behav Res. 1991;26:83–107. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2601_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiClemente C, Prochaska J. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7:133–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gielen AC, Sleet D. Application of behavior-change theories and methods to injury prevention. Epidemiol Rev. 2003;25:65–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SS, Paiva AL, Cummins CO, Johnson JL, Dyment SJ, Wright JA, et al. Transtheoretical model-based multiple behavior intervention for weight management: effectiveness on a population basis. Prev Med. 2008;4:238–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noh S, Gagné JP, Kaspar V. Models of health behaviors and compliance: applications to audiological rehabilitation research. In: Gagné JP, Tye-Murray N, editors. Research in audiological rehabilitation: current trends and future directions. (Vol. XXVII) Gainesville, FL: J Acad Rehabil Audiol Monograph supplement; 1994. pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milstein D, Weinstein BE. Effects of information sharing on follow-up after screening for older adults. J Acad Rehabil Audiol. 2002;35:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babeu LA, Kricos PB, Lesner SA. Application of the stages-of-change model in audiology. J Acad Rehabil Audiol. 2004;37:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaldo V, Richards J, Andersson G. Tinnitus stages of change questionnaire: Psychometric development and validation. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:483–97. doi: 10.1080/13548500600726674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobel J, Meikle M. Applying health behaviour theory to hearing-conservation interventions. Sem Hear. 2008;29:81–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawool VW, Colligon-Wayne LA. Auditory lifestyles and beliefs related to hearing loss among college freshman in the USA. Noise Health. 2008;10:1–10. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.39002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilliver M, Hickson L. Medical practitioners' attitude to health rehabilitation for older adults. Int J Audiol. 2011;50:850–56. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.601468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organisation. Deafness and hearing impairment, Fact Sheet n. 300. 2005 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs300/en/

- 27.Star P, Hickson L. Outcomes of hearing aid fitting for older people with hearing impairment and their significant others. Int J Audiol. 2004;43:390–8. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hear It. Hearing loss under-diagnosed and under-treated. 20011 Available from: http://www.hear-it.org/page.dsp?page=2990.

- 29.NIDCD. Statistics about Hearing, Balance, Ear Infections, and Deafness. 2009 Available from: http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/hearing.html.

- 30.NSSO. New Delhi: National Sample Survey Organisation; 2002. Disabled persons in India. NSS 58th round. July-December. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudsen LV, Öberg M, Nielsen C, Naylor G, Kramer SE. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid sue and satisfaction with hearing aids: a review of literature. Trends Amplif. 2010;14:127–54. doi: 10.1177/1084713810385712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawool VW, Kiehl JM. Effectiveness of informational counseling on acceptance of hearing loss among older adults. Hear Rev. 2009;16:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck D. The art and science of motivational influence. BAA Magazine. 2011;19:12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck DL, Harvey MA, Schum DJ. Motivational interviewing and amplification. Hear Rev. 2007;4:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ida Institute. Goal sharing for partners strategy. 2010 Available from: http://idainstitute.com/tool_room/tools/goal_sharing_for_partners_strategy/

- 36.Manchaiah VKC, Stephens D, Meredith R. The patient journey of adults with hearing impairment: the patients' view. Clin Otol. 2011;6:227–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens D, Kramer SE. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Living with hearing difficulties: the process of enablement. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manchaiah VKC, Stephens D, Zhao F, Kramer SE. Role of communication partner in the audiological enablement/rehabilitation of person with hearing impairment: an overview. Aud Med. 2011 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao F, Manchaiah VKC, French D, Price S. Music exposure and hearing disorders: an overview. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:54–64. doi: 10.3109/14992020903202520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morata TC. Young people: their noise and music exposure and the risk of hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2007;49:54–64. doi: 10.1080/14992020601103079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith PA, Davis A, Ferguson M, Lutman ME. The prevalence and type of social noise exposure in young adults in England. Noise Health. 2000;2:41–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao F, French D, Manchaiah VKC, Liang M, Price S. Music exposure and hearing health education: knowledge, attitude and behavior in adolescents and young adults. Health Educ J. 2011 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior. (Vol. 4) New York: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]