Abstract

Anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies play an important immunopathologic role in SLE patients. To analyze the cellular origin and the VH and VL structure of anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies, we generated five IgA1 mAbs to DNA using B lymphocytes from three SLE patients. Two mAbs bound to ssDNA only and one to both ssDNA and dsDNA (monoreactive antibodies). The remaining two mAbs bound to DNA (one to ssDNA and the other to both ssDNA and dsDNA) and to other self and foreign Ag (polyreactive antibodies). The IgA mAb relative avidity for DNA ranged from 7.5 × 10−8 to 8.0 × 10−10 g/μl. The anti-DNA IgA mAb used VH segments of the VHI (VI-3b), VHII (VH2-MC2), VHIII (WHG16G and VH26c), and VHIV (V71-2) families in conjunction with VΚI, VΚIIIb, or Vλl segments. All IgA mAb VH segments were juxtaposed with JH4b segments. The heavy chain CDR3 sequences were divergent in composition and length. When compared with those of the closest reported germ line genes, the IgA mAb VH and VL gene sequences displayed a number of differences. That these differences represented somatic point mutations was formally proved in both the monoreactive IgA mAb 412.67.F1.3 and the polyreactive IgA mAb 412.66.F1 VH segments by differential PCR amplification and cloning and sequencing of genomic DNA from the mAb-producing cell lines and autologous polymorphonuclear cells. The sequences of the germ line genes that putatively gave rise to the mAb 412.67.F1.3 and mAb 412.66.F1 VH segments were identical with those of the WHG16G and VH26c genes, respectively. In not only the monoreactive mAb 412.67.F1.3 but also the polyreactive mAb 412.66.F1 and mAb 448.9G.F1 VH segments, the higher concentration of replacement (R) mutations and the higher R:S (silent) mutation ratios in the complementarity-determining region (∞; 19:0) than in the framework region (1.0) (p = 0.00001, χ2 test) were highly consistent with selection by Ag. In the five IgA mAb VH and VL segments, the putative and verified somatic point mutations yielded 68 amino acid replacements, of which 38 were nonconserved. Twenty of these yielded positively charged or polar residues that play a major role in DNA binding, including seven Arg, five Lys, three Tyr, two Gin, two His, and a Thr. The conserved amino acid changes included seven Asn. These findings suggest that anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies use a broad selection of VH and VL genes and enhance their fit for Ag by undergoing somatic hypermutation and Ag selection. Such a hypermutation and Ag selection process would apply to originally polyreactive, in addition to monoreactive natural DNA binding IgA autoantibodies.

In SLE patients, the dominant autoimmune response consists of IgG, IgA, and IgM to various nuclear components, including DNA, RNA, histones, and proteins of the Sm complex (1). Most anti-DNA IgM autoantibodies display multiple reactivities to other cellular components and a variety of extracellular molecules (2–5). Thus, they resemble in class (IgM) and polyreactivity the DNA binding natural autoantibodies found in healthy subjects and patients with certain infectious diseases (6–12). Natural autoantibodies arise from a process of polyclonal B cell activation and use, in general, VH genes in germ-line configuration (12, 13). In contrast, possibly pathogenic anti-DNA IgG autoantibodies in SLE patients are thought to arise through a process of affinity maturation, as suggested by the distribution and nature of the verified (14–17) and putative (18) somatic point mutations in their V segments. Such an affinity maturation process entails oligoclonal B cell expansion, somatic lg V gene hypermutation, and Ag-directed clonal selection, as documented in autoimmune MRL/lpr and (NZB × NZW)F1 mice (19–22).

In both SLE patients and lupus mice, IgG anti-DNA autoantibodies are major constituents, along with Ag and C′ components, of circulating immune complexes (IC)5. Anti-DNA autoantibody avidity and IC formation correlate with disease activity; their deposition and/or in situ formation in kidneys, brain, and lungs can result in chronic inflammation and eventually tissue destruction (23-26). In addition to IgG, anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies contribute to IC formation and pathology (27–31). In SLE patients, anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies are present at high levels in the circulation and are deposited in the kidney as pre-formed and/or in situ formed IC. Their deposition in kidneys can induce proliferation of glomerular mesangia, glomerular lesions, and sclerosis, eventually progressing to end-stage renal failure (31, 32).

Despite the important role of anti-DNA IgA autoanti-bodies in kidney pathology and in other SLE lesions, the structure of only one IgA mAb has been reported (18). We generated five polyreactive and monoreactive anti-DNA IgAl mAb from three patients with active SLE. The anti-DNA IgA mAb VH and VL genes extensively overlapped with those of natural and disease-associated anti-DNA IgM and IgG autoantibodies. They also displayed a number of putative and verified somatic point mutations consistent in nature and distribution with those resulting from an Ag selection process. Thus, in SLE patients a process of somatic hypermutation and Ag selection may apply to B cells committed to the production of natural polyreactive or monoreactive DNA binding Ig, resulting in the generation of high affinity polyreactive or monoreactive IgA autoantibodies to DNA.

Materials and Methods

Patients, preparation, and culture of B lymphocytes, analysis of Ag binding activities, and generation of human mAb

PBMC were obtained from three women (30, 50, and 67 yr old) with clinically active SLE and presenting at least four of the American Rheumatism Association criteria for the disease. All patients were receiving prednisone (<20 mg/day), which was withdrawn 24 to 48 h before obtaining blood. None was receiving cytotoxic drugs. B cells were enriched from PBMC by depletion of T cells and monocytes. transformed with EBV and distributed at 500/well in 96-well microculture plates in the presence of 105 irradiated PBMC as feeders (3, 4, 13, 33-36). After a 3-wk culture, fluids were analyzed for binding to dsDNA and ssDNA using specific ELISA (3, 4, 13, 33-36). For the dsDNA-specific ELISA, plates were precoated with 2 μg/ml protamine sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, for 2 days at 4°C then coated with dsDNA (10 μg/ml) in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0.

EBV-transforrned B lymphocytes producing IgA autoantibodies to ssDNA or dsDNA were selected by sequential subculturing and cloning (3, 4, 33–36). To yield maximal mAb production rates, cloned cells were fused with the F3B6 cell line (3, 13, 33–36). The mAbs were analyzed for direct binding to ssDNA, dsDNA, cardiolipin, phosphorylcholine chlo-ride, actin, human recombinant insulin, human polyclonal IgG Fe fragment, and tetanus toxoid using specific ELISA (3, 4, 13, 33–36). Cardiolipin-specific ELISA plates were prepared by incubation with cardiolipin (Sigma Chemical Co.) (100 μg/ml) in ethanol that was then evaporated overnight at room temperature.

mAb relative avidity (Avrel) was measured by competitive inhibition ELISA (3, 4, 13, 33–36). Briefly, increasing amounts (0.025 to 400 μg) of soluble Ag were mixed with the same amount of mAb in 100 μl of PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween) and 1% BSA. After an 18-h incubalion at room temperature, the mixtures were transferred into ELISA plates precoated with either the same Ag that was used in the preincubation step or a different Ag (homologous and heterologous competition, respectively). After a l-h incubation and subsequent washing with PBS-Tween, the amount of mAb bound to the solid phase Ag was measured using a peroxidase-conjugated affinity-purified goat Ab to human Ig α heavy chain. For each mAb. the binding measured after incubation under identical conditions but in the absence of soluble Ag (always more than 1.00 OD at 492 nm; negative control less than 0.04 OD) represented 100% binding activity (3, 4, 33–36). The concentration (g/μl) of soluble Ag yielding 50% of inhibition of mAh binding to homologous solid phase Ag was used to express the mAb Avrel for Ag.

Cloning and sequencing of expressed lg VH and VL genes

Poly(A)+ RNA was purified from mAb-producing cells using the Micro Fast-Track mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA), and reverse transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Super-Script RNaseH-Reverse Transcriptase; GIBCO BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Specific VH or VL gene DNA was amplified by PCR using first-strand cDNA template (5 μl) in a 50-μ volume containing 200 μM of each dNTP, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer Corp., Norwalk, CT), and 10 pmol of each (sense and antisense) oligonucleotide primer. The degenerate sense oligonucleotide primers encompassed areas of the leader sequences of different VH gene families (plus an EcoR I site) as follows: VHI [5′ GGGAATTCATGGACTGGACCfGGAGG(AG)TC (CT)TCT(GT)C 3′]; VHIII [5′ GGGAATTCATGGAG(CT)TTGGGCT GA(CG)CTGG(CG)TIT(CT)T 3′]; VHIV [5′ GGGAATTCATGAA (AG)CA(TC)CTGTGGTTCTT(CI)(AC)T(CT)CT(CG)C 3′]; and HI-3 (VHIII family) (5′ ITGGGCTGTGCTGGGTITICCT 3′]. The Cα antisense primer specific for the 5′ sequence of the IgAl and lgA2 heavy chain constant region genes was [5′ GGGAATTCGACCTTGGGGCTG GTCGGGGAT 3′]. The sense oligonucleotides priming the leader regions of the Vκ and Vλ chain gene subgroups were as follows: VκI-II (VκI and VκII chains) [5′ AGCTCCTGGGGCT(GC)CT(AG)(AC)T GCTCT 3′]; VκIII [5′ TCTCTTCCTCCTGCTACTCTGGCT 3′]; VκIV [5′ ATGGTGTTGCAGACCCAGGTCTTC 3′]; VλI [5′ ATG(GA)CC (TG)GCT(CT)CCCTCTCCTCCT 3′]; VλII-VI (VλII. VλIII, VλIV; and VλVI chains [5λ ATG(AG)C(CT)TGGACCC(CT)(AT)CTC(CT)(TG) (TG)TT 3′].

The Ig Cκ chain antisense oligonucleotide primer was [5′ CTGTCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAGA 3λ] and the Cλ chain antisense oligonucleotide primer was [5λ TTGGCITGAAGCTCCTCAGAGGA 3λ]. PCR entailed 25 cycles of denaturing, annealing. and extension at 94°C (1 min), 52°C (1 min), and 72°C (1 min), respectively. For Vκ gene amplification, an annealing temperature of 58°C was used. Amplified DNA was inserted into the pCR II plasmid vector (Invitrogen Corp.) and cloned in competent INVαF′ cells (Invitrogen Corp.) for sequencing.

Analysis of putative germ line Ig VH genes that gave rise to the IgA mAb 472.67.F1.3 and IgA mAb 412.66.F1 VH segments

Genomic DNA was extracted from the mAb 412.67.F1.3· and mAb 4l2.66.Fl-producing cell lines and from the polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) of the patient whose B cells were used to generate these mAb and subjected to PCR using different combinations of appropriate oligonucleotide primers. To assess the somatically mutated status of the mAb 412.67.FL3 VH gene, three pairs of oligonucleotide primers were used: 1) the sense 67b′ primer, encompassing a stretch of the CDR2 sequence [5′ GTAGTAATACTAACATATACTAC 3′] of the expressed VH gene differing in three nucleotides from the corresponding germ-line WHG16G sequence and the antisense 67a primer, encompassing a FR3 sequence [5′ TAAACAGCCGTGTCCTCGGCTCT 3′] shared by different VHIII family members (the 67a oligonucleotide is identical with HI-2, which is part of our collection of primers); 2) the sense 67b primer, encompassing a sequence [5′ TGGGTCTCATCCATTAGTAG 3′] of the FR2-CDR2 region shared by the expressed mAb VH gene and the WHG16G germ-line gene and the antisense 67a primer; 3) the sense HI-3 and the antisense 67c primers. The 67c oligonucleotide encompassed a FR3 sequence [5′ CAGTGAGTTCTTGGCCTTGTC 3′] of the WHG16G germ-line gene that differed in two nucleotides from the corresponding sequence of the mAb VH gene. The 67b and 67c oligonucleotides were designed based on a thorough analysis of the VHIII family genes, which suggested that they would preferentially amplify WHG16G and WHG16G-Iike genes over other VHIII family members. To assess the somatically mutated status of the mAb 412.66.FI VH gene, two pairs of oligonucleotide primers were used: 1) the sense 66b′ primer encompassing a stretch of the CDR2 sequence [5′ GGTATTAGTGGTAGTGGTTAT 3′] of the expressed mAb VH gene differing in three nucleotides from the corresponding area of the germ line VH26c sequence and the anti-sense 66a (HI-2) primer encompassing a FR3 sequence of the mAb 412.66.Fl gene dilfering in only two nucleotides from the corresponding area of the germ-line VH26c sequence; and 2) the sense VH26cl primer encompassing a portion of the VH26c gene leader sequence [5′ GGCTTTTTCTTGTGGCTATTT 3′] identical to the Corresponding portion of the mAb 412.66.Fl VH gene sequence and the antisense 66a primer.

In PCR amplifications of genomic mAb 412,67.F1.3 and mAb 412.66.FI VH segment DNA, the annealing temperature was optimized according to the melting temperature (Tm) of the individual 66a, 66b′, 67a, 67b, 67b′, or 67c oligonucleotide primer used. For Southern hybridization, amplified DNA was fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel and then blotted onto Hybond C nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Life Sciences, Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL) for reaction with the appropriate oligonucleotide probe labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Du Pont-NEN Research Products, Boston, MA) by T4 polynucleotide kinase. After hybridization at 48°C, membranes were washed twice with 2X SSC/0.5% SDS at room temperature for 30 min and twice with IX SSC/0.5% SDS at 52°C for 30 min.

Gene sequencing and data analysis

Sequencing was performed by the dideoxy chain termination method using [α-35S]dATP (Du Pont-NEN Research Products) and the TaqTrack Sequencing Systems (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), including the appropriate forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers. In some cases, a reverse JH consensus primer [5′ TGAGGAGACGGTGACC 3′] was also used. Each Ig V gene sequence was derived from the analysis of at least four independent clones. Nucleotide sequence differences among different recombinant clones were less than 0.001/bp. Such variant sequences were excluded from analysis. Sequence analysis and identity searches were performed using a model 6000-410 VAX computer (Digital Equipment Corp., Marlboro, MA), the software package of the Genetics Computer Group of the University of Wisconsin, Release 6, the GenBank database, and the FASTA program (37).

Results

Generation of the anti-DNA IgA mAb-producing cell lines and IgA mAb analysis

Five anti-DNA IgAl mAb-producing cell lines were generated using peripheral blood B cells from the three SLE patients and DNA as a selecting Ag (Table I). Of the three mAb selected for binding to ssDNA, two were monoreactive (mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 447.8H) and one was poly-reactive, binding to ssDNA, dsDNA, cardiolipin, and other self and foreign Ag (mAb 412.66.F1). Of the two mAb selected for binding to dsDNA, one bound also to ssDNA (mAb 412.67.F1.3) and the other was polyreactive (mAb 448.9G.F1). The binding of each IgA mAb to solid phase Ag was dose saturable (data not shown), The IgA mAb Avrel for ssDNA ranged from 7.5 × 10−8 to 8.0 × 10 −10 g/μl; those for dsDNA were 4.4 × 10×8 and 2.7 × 10−9 g/μl (Table I). The polyreactive IgA mAb Avrel for Ag other than ssDNA or dsDNA ranged from 2.2 × 10−7 (mAb 448.9G.F1 binding to tetanus toxoid) to 9.0 × 10−9 (mAb 412.66.F1 binding to actin) g/μl.

Table I.

Features and Avrel of the anti-DNA IgA1 mAb for different self and exogenous Aga

| mAb Chains |

Ag |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAb | Patient | Heavy, light | ssDNA | dsDNA | Cardiolipin | Phophorylcholine | Actin | Insulin | IgG Fc fragment | Tetanus toxoid |

| mAb 424.F6.24 | B | α1, κ | 7.0 × 10−9 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 |

| mAb 447.8H7 | B | α1, κ | 7.5 × 10−8 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 |

| mAb 412.67.F1.3 | A | α1, κ | 8.0 × 10−10 | 2.7 × 10−9 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 |

| mAb 41 2.66.F1 | A | α1, κ | 3.0 × 10−8 | >10−4 | 2.0 × 10−8 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 9.0 × 10−9 | 1.7 × 10−7 | >10−4 | 1.6 × 10−7 |

| mAb 448.9C.F1 | C | α1, λ | 2.2 × 10−9 | 4.4 × 10−8 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | 2.2 × 10−7 |

Avrel is expressed as the concentration of fluid phase Ag (g/μl) inhibiting by 50% the binding of mAb to homologous solid phase Ag. For each mAb, the binding measured in absence of soluble Ag represented 100% binding activity. This consisted in all cases of an OD of more than 1.00 at 492 nm; negative controls were always less than 0.040 OD (see Materials and Methods for details).

Anti-DNA IgA mAb VH segments

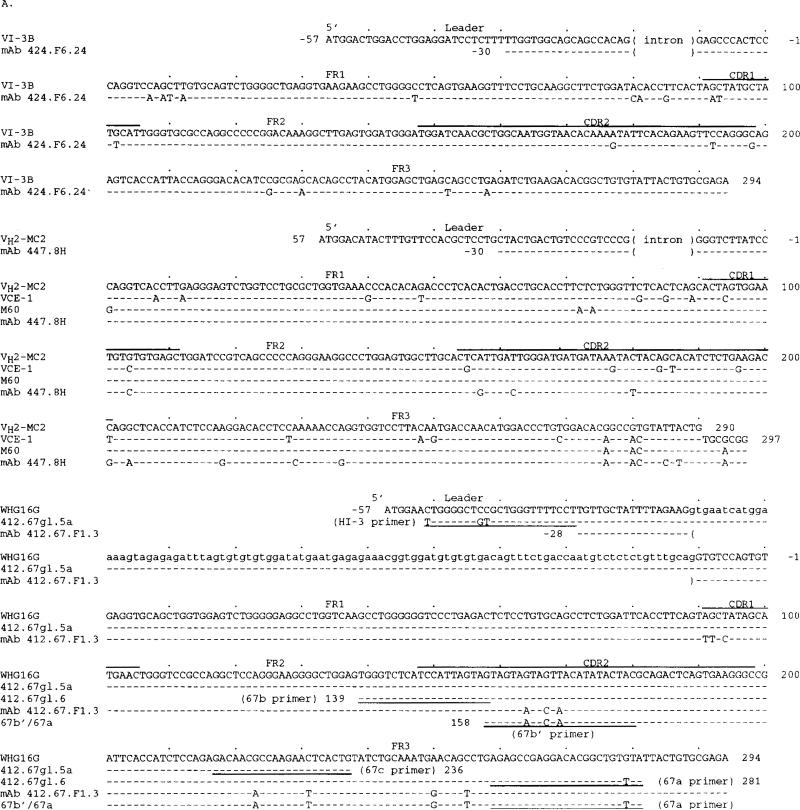

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the five mAb VH genes are depicted in Figure 1, A and B, respectively; their differences when compared with the closest germ line gene sequences are summarized in Table II. The mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 447.8H VH segment sequences were 93.9 and 96.6% identical with those of the germ-line (VHI) VI-3b (38) and (VHII) VH2-MC2 (39) genes, respectively. They displayed a significantly higher frequency of putative nucleotide changes in the CDR (8.1 × 10−2 change/base) than in the FR (3.9 × 10−2 change/base) (p 0.034, χ2 test) yielding, however, low and comparable R:S mutation ratios in the CDR (0.83) and FR (1.0), Because only two VHII germ-line gene sequences have been reported, the sequences of two expressed VHII genes, VCE-I (40) and M60 (41), are also shown (Fig. 1A). The three bases shared by the mAb 447.8H, VCE-1, and M60 but not the genomic VH2-MC2 gene sequences (A, A, and C at positions 276, 280, and 281, respectively) suggested that the mAb 447.8H VH gene represented a variant of VH2-MC2. Thus, the mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 447.8H VH segments could represent somatically mutated forms of the VI-3b and VH2-MC2 genes, respectively, or alternatively the expression of still uncharacterized VH genes.

FIGURE 1.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the VH genes used by the anti-DNA IgA mAb. In each cluster, the top sequence represents the germ-line VH gene sequence displaying the highest degree of identity to the expressed VH gene sequences of the cluster. The VI-3b, VH2-MC2, VH26c, WHG16G, and V71-2 genes belong to the VHI, VHII, VHIII, VHIII, and VHIV families, respectively. Dashes indicate identities. Solid lines on the top of each cluster depict CDR. Small letters denote intron sequences. VCE-1 is a VHII genomic sequence. M60 is a VH gene expressed in fetal liver. Oligonucleotide (sense) primer sequences or reverse complementary (antisense) primer sequences are underlined. 412.67gl.5a is the portion of the germ-line VH gene sequence derived from PMN genomic DNA using the combination of the Hl-3 and 67c primers; 412.67gl.6 is the sequence derived from PMN genomic DNA using the combination of 67b and 67a primers (see Materials and Methods and Results). The 67b′/67a is the sequence derived from mAb 412.67.F1.3-producing B cell genomic DNA using the combination of 67b′ and 67a primers. The 412.66gl is the germ-line VH gene sequence amplified from PMN genomic DNA using the combination of the VH26cl and 66a primers. The 66b′/66a is the sequence derived from mAb 412.66.F1-producing B cell genomic DNA using the combination of the 66b′ and 66a primers. These sequences are available from the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L28049, L28050, L28051, L28052, and L28053.

Table II.

Anti-DNA IgA1 mAb V, D, and J genes

| VH Segment |

VL Segment |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closest VH gene (family)a | Nucleotide (amino acid) identityb % | Nucleotide differences |

Closest VL gene (family)d | Nucleotide (amino acid) identity % | Nucleotide differences |

||||||||||

| CDR |

FR |

D genec | JH genec | CDR |

FR |

JL Gene | |||||||||

| mAb | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | S | |||||||

| mAb 424.F6.24 | VI-3b (VHI) | 93.9 (91.8) | 3 (3.2)e | 3 | 5 (10.5) | 7 | DN1 | JH4b | HumKv325 (VκIIIb) | 98.6 (97.9) | 2 (0.7) | 1 | 0 (2.3) | 1 | Jκ2 |

| mAb 447.8Hf | VH2-MC2 (VHII) | 96.6 (93.9) | 2 (2.0) | 3 | 4 (6.3) | 2 | D21-7 | JH4b | HumKv325 (VκIIIb) | 94.8 (90.7) | 6 (2.6) | 2 | 4 (8.7) | 3 | Jκ4 |

| mAb 412.67.F1.3 | WHC16G (VHIII) | 96.6 (92.8) | 6 (1.8) | 0 | 2 (5.7) | 2 | DM2 | JH4b | HumKv325 VκIIIb) | 97.9 (96.9) | 2g (1.2) | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 2 | Jκ1 |

| mAb 412.66.F1 | VH26c (VHIII) | 95.9 (92.8) | 5 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (5.2) | 2 | DxP′4 | JH4b | kalc6h (VκI) | 99.3 (100.0) | 0 (0.4) | 1 | 0 (1.1) | 1 | Jκ2 |

| mAb 448.9C.F1 | V71-2 (VHIV) | 93.3 (85.8) | 8 (3.7) | 0 | 6 (11.1) | 6 | DLR2 | JH4b | YM-17 (VλI) | 93.2 (87.4) | 11i (3.9) | 6 | 3 (11.7) | 1 | Jλ2 |

The sequences of the germ line VH genes have been reported as follows: VI-3b (38), WHG16G (42), VH26c (43), V71-2 (44), and VH2-MC2 (39).

Compared with the germ line genomic sequences.

The DN1, DM2, DxP′4, and DLR2 genes have been reported by Ichihara et al. (45); the D21-7 gene has been reported by Buluwela et al. (46). The JH4b has been reported by Yamada et al. (47).

The sequences of the genomic germ line VL genes have been reported as follows: HumKv325 (51), kalc6 (52), and YM-1 (54).

Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of putative R mutations expected based on chance alone (see Results).

The mAb 448.9C.F1 Vλ sequence comparison is reported as the number of nucleotides not shared with either of the related genes YM-1 or T1 (55).

Does not include the nucleotide changes yielding the replacement of the W with an R at position 97 (first codon of the Jκ-encoded portion of CDR3).

mAb kalc6 is an expressed gene sharing the highest degree of homology with the mAb 412.66.F1 Vκ sequence.

Does not include the nucleotide changes yielding the replacement of the V with a W at position 97 (first codon of the Jκ-encoded portion of CDR3).

The mAb 412.67.F1.3, mAb 412.66.F1, and mAb 448.9G.F1 VH gene sequences were 93.3 to 96.6% identical to those of the germ-line (VHIII) WHG16G (42), (VHIII) VH26c (43), and (VHIV) V71-2 (44) genes, respectively. They displayed a significantly higher frequency of putative nucleotide changes in the CDR (28.3 × 10−2 change/base) than in the FR (8.7 × 10−2 change/base) (p 0.001, χ2 test), yielding significantly higher R:S mutation ratios in the CDR (∞; 19:0) than in the FR (1.0) (p = 0.00001, χ2 test). Thus, the mAb 412.67.F1.3, mAb 412.66.F1, and mAb 448.9G.F1 VH segments probably represented somatically mutated forms of the WHG16G, VH26c, and V71-2 genes, respectively. Alternatively these mAb VH segments constituted the expression of still uncharacterized VH genes.

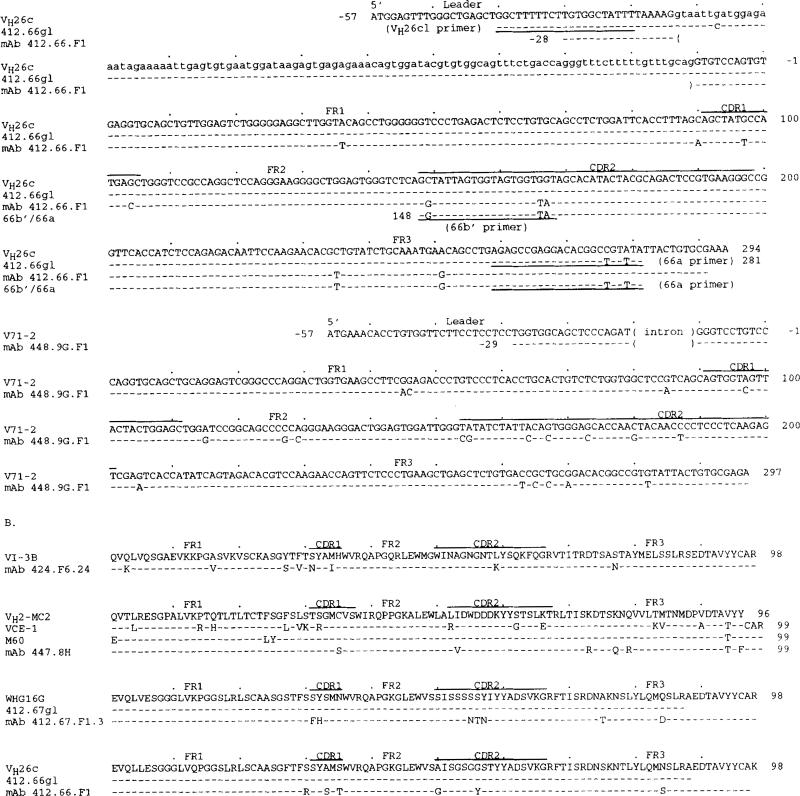

IgA mAb D and JH genes and CDR3 segments

The expressed D segment sequences were compared with those of the reported germ-line D and DIR genes (Fig. 2A). All expressed D genes were 3′ flanked by nontemplated residues (N additions) and all but that encoding mAb 448.9G.F1 were also 5′ flanked by nontemplated nucleotides. The mAb 424.F6.24 D gene contained a 16-base sequence similar to a portion of the DNl gene (45) and the mAb 447.8H D gene sequence displayed an 8-base stretch identical to a portion of the D21-7 gene (46). The mAb 412.67.F1.3, mAb 412.66.F1, and mAb 448.9G.F1 D gene sequences contained stretches of similarity to those of the DM2, DxP′ 4, and DLR2 genes, respectively (45). All five mAbs used the JH4b gene (Fig. 2.4.) (47) whose sequence is considered the prototypic JH4 sequence (42, 47, 48) rather than the original JH4 sequence reported in a single individual (49). mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 448.9G.F1 used full-length forms of JH4b, each with two mutations; mAb 447.8H, mAb 412.66.F1, and mAb 412.67.F1.3 used variously truncated forms of JH4b (Fig. 2A) containing two, two, and no mutations, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences of the D-JH segments of the five mAb were divided into CDR3 and FR4 stretches (Fig. 2B) according to Kabat et al. (50). The CDR3 sequences were highly divergent in composition and ranged in length from 10 to 15 amino acids; the FR4 sequences were invariable in length and displayed little diversity.

FIGURE 2.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) junctional VH-D-JH sequences of the anti-DNA IgA mAb heavy chain genes. Germ-line D genes are given for comparison. Dashes indicated identities. The VH, D, JH gene and unencoded (N) origin of the individual nucleotides are indicated. The deduced amino acid sequences are depicted as segregated into CDR3 and FR4. These data are available from the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L28049, L28050, L28051, L28052, and L28053.

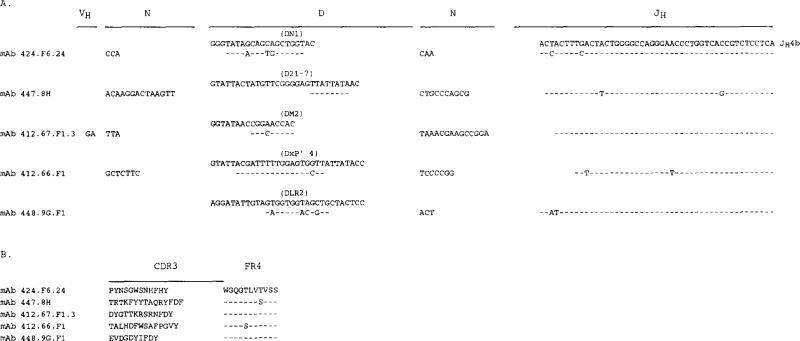

Anti-DNA IgA mAb VL and JL segments

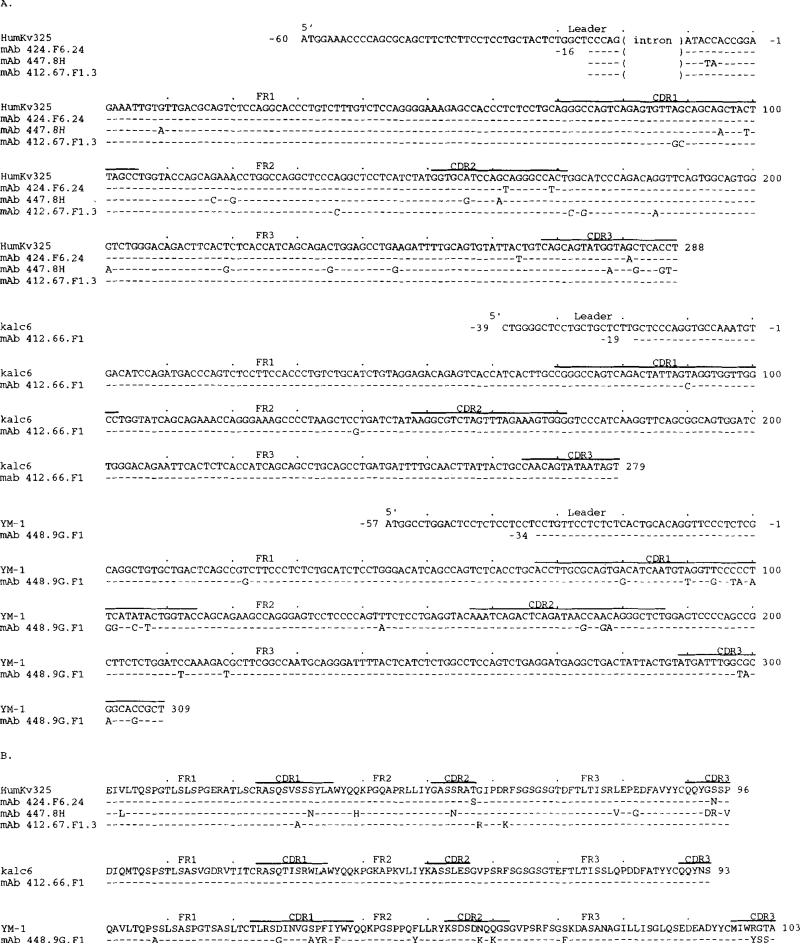

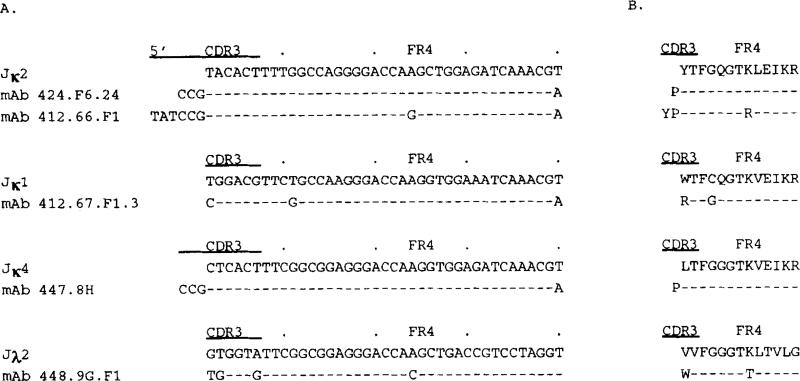

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the five anti-DNA IgA mAb VL segments are depicted in Figure 3, A and B, respectively; their differences when compared with the sequences of the closest reported VL genes are summarized in Table II. Both mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 412.67.F1.3 used the HumKv325 (VκIIIb) gene (51) with minimal changes. mAb 447.8H used the HumKv325 gene with 15 base differences, 8 of which were in the CDR. The mAb 412.66.F1 Vκ gene deduced amino acid sequence was identical to that of the expressed kalc6 gene (52) whose nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were 98.2 and 99.0% identical, respectively, to those of the germ-line HK102 VκI gene (53). mAb 448.9G.F1 used a Vλ segment with a sequence similar to that of the bone marrow-derived, possibly unmutated YM-1 gene (54). Of the 13 amino acid differences, 6 are shared by the related Vλ segment T1 sequence (55), suggesting that the mAb 448.9G.F1 Vλ segment represents the expression of a polymorphic member of the novel YM-1 Vλ subgroup. The sequences of the JL segments used by the anti-DNA IgA mAb are depicted in Figure 4. mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 412.66.F1 used mutated forms of the Jκ2 gene (56), both 5′ flanked by nontemplated nucleotides, encoding a Pro residue and Pro-Tyr residues, respectively. The mAb 447.8H used an unmutated Jκ4 segment (56), also 5′ flanked by a nontemplated triplet encoding a Pro. Finally, mAb 412.67.F1.3 and mAb 448.9G.F1 used mutated forms of the Jκ1 (56) and Jκ2 (57) genes, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the VL genes used by the anti-DNA autoantibodies. In each cluster, the top sequence represents the germ line VL gene sequence displaying the highest degree of identity to the expressed VL gene sequences of the cluster. The HumKv325 and kalc6 genes belong to the VκIII and VκI subgroups, respectively. The YM-1 gene is most likely a member of a novel Vλ. subgroup. The kalc6 and YM-1 are an expressed RF gene and a bone marrow-derived gene. Dashes indicate identities. Solid lines on the top of each cluster depict CDR. Oligonucleotide primer sequences (sense) or reverse complementary primer sequences (antisense) are underlined. These sequences are available from the EMBL/GenBankDDBJ under accession numbers L28043, L28045, L28046, L28047, and L28048.

FIGURE 4.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) JL sequences of the anti-DNA IgA mAb. Germ line JL genes are given for comparison. Dashes indicated identities. The deduced amino acid sequences are depicted as segregated into CDR3 and FR4. These data are available from the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L28043, L28045, L28046, L28047, and L28048.

Somatic mutations in the anti-DNA monoreactive IgA mAb 412.67.F1.3 and polyreactive IgA mAb 412.66.F1 VH segments

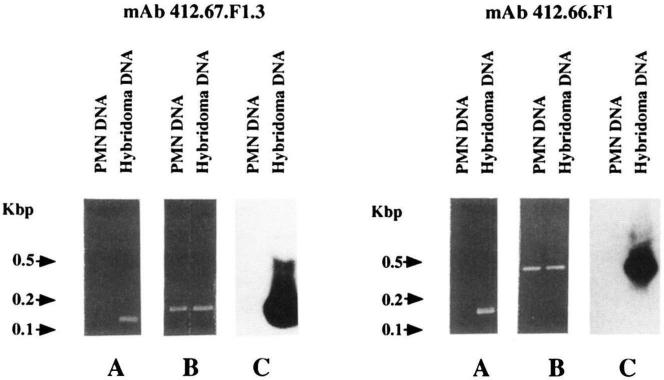

In spite of the high degree of conservation of many human Ig VH genes (11), we set out to verify the somatic point mutations in both monoreactive and polyreactive anti-DNA IgA mAb. Using the sense 67b′ primer encompassing a stretch of the monoreactive mAb 412.67.F1.3 VH gene CDR2 sequence differing in three bases from the corresponding germ-line WHG16G gene sequence, in conjunction with the antisense 67a primer, encompassing a FR3 sequence shared by the expressed and germ line VH genes (Fig. 1A), we amplified by PCR a DNA product from the hybridoma but not from autologous PMN genomic DNA (Fig. 5, mAb 412.67.F1.3, lane A). The amplified DNA (124 bp) was identical with the sequence spanning residues 158-281 of the mAb 412.67.F1.3 VH gene (Fig. 1A, 67b′/67a sequence). A second PCR using the antisense 67a primer and the sense 67b primer encompassing a FR2-CDR2 sequence shared by the mAb 412.67.F1.3 and WHG16G VH genes but different from the corresponding sequence of other VHIII genes amplified products from both hybridoma and PMN genomic DNA (Fig. 5, mAb 412.67.F1.3, lane B). The size of the amplified DNA (~140 bp) was consistent with that of the sequence spanning residues 139–281 of the mAb 412.67.F1.3 VH gene sequence (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 5.

Evidence for somatic mutations in the IgA mAb 412.67.F1.3 (left panels) and IgA mAb 412.66.F1 (right panels) VH genes. Lanes A depict ethidium bromide staining of DNA PCR amplified from hybridomas and fractionated in agarose gel electrophoresis (right lanes). A 124-bp PCR product was obtained from the genomic DNA of the B cell hybridoma producing mAb 412.67.F1.3 using the sense CDR2 (67b′) and the antisense FR3 (67a) oligonucleotide primers, and a 134-bp PCR product was obtained from the genomic DNA of the B cell hybridoma producing mAb 412.66.F1 using the sense CDR2 (66b′) and antisense FR3 (66a) oligonucleotide primers (see Materials and Methods). The same combinations of primers failed to amplify PMN DNA from the same patient whose B cells were used for the generation of mAb 412.67.F1.3 and mAb 412.66.F1 (left lanes). Lanes B depict ethidium bromide staining of DNA amplified from PMN and hybridoma genomic DNA and fractionated in agarose gel electrophoresis. The sense CDR2 (67b) and the antisense FR3 (67a) oligonucleotide primers whose sequences are shared by the mAb 412.67.F1.3 and WHG16G genes yielded a 143-bp PCR product from both PMN (left lane) and mAb 412.67.F1.3-producing cell lines (right lane). Accordingly, the sense VH26cl and antisense 66a oligonucleotide primers whose sequences are shared by the mAb 412.66.F1 and VH26c genes yielded amplification products of 422 bp from both autologous PMN (left lane) and mAb 412.66.F1-producing cell DNA (right lane). Lanes C depict Southern hybridization of the PCR products shown in lanes B with the appropriate [γ-32P]-labeled 67b′ or 66b′ oligonucleotide used as a probe. In both cases, a strong positive hybridization signal was detected with DNA amplified from the hybridoma cell line but not with that amplified from autologous PMN genomic DNA (right lanes).

Southern blot analysis showed that the product amplified from hybridoma but not PMN DNA strongly hybridized with the [γ-32P]-labeled 67b′ oligonucleotide used as a probe (Fig. 5, mAb 412.67.F1.3, lane C). To identify the germ-line gene that putatively gave rise to the mAb VH gene, PMN genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using the sense HI-3 VHIII leader primer and the antisense 67c primer (specific for a FR3 area of the WHG16G gene). The amplified DNA was cloned and 10 independent isolates sequenced. Seven were identical to one another and 92.2% identical to WHG16G (data not shown); one was 89.4% identical to WHG16G (data not shown). The sequences of the remaining two isolates were identical to that of the WHG16G gene (Fig. 1A; 412.67gl.5a sequence) and different in three bases from that of the expressed VH gene throughout the overlapping area. Because the 412.67gl.5a sequence excluded the four putative 3′ FR3 base changes, the 143-bp germ-line segment amplified from PMN genomic DNA using the 67b and 67a primers was cloned, sequenced (four isolates), and found to be identical to the WHG16G and 412.67gl.5a genes throughout the 98-bp overlapping area (Fig. 1A; 412.67g1.6 sequence). These experiments demonstrated that the mAb 412.67.F1.3 VH segment was somatically mutated and strongly suggested that it arose from a germ-line gene identical to WHG16G.

The concentration of the putative R mutations and high R:S mutation ratio (∞; 5:0) in the CDR of the polyreactive anti-DNA IgA mAb 412.66.F1 and mAb 448.9G.F1 VH segments (Table II) were inconsistent with the accepted notion that polyreactivity is a function of unmutated V genes. To verify the configuration of the mAb 412.66.F1 VH gene, we used the sense 66b′ primer encompassing a stretch of the CDR2 sequence of the expressed gene and differing in three bases from the corresponding area of the germ-line VH26c gene in conjunction with the antisense 66a primer. With PCR we amplified a DNA product from hybridoma but not autologous PMN genomic DNA (Fig. 5, mAb 412.66.F1, lane A). The amplified DNA (134 bp) was identical with the sequence spanning residues 148-281 of the mAb 412.66.F1 VH gene (Fig. 1A, 66b′/66a sequence). Use of the sense VH26cl leader primer and the antisense 66a primer amplified products from both hybridoma and PMN genomic DNA (Fig. 5, mAb 412.66.F1, lane B). The size of these DNA (~400 bp) was consistent with that of the sequence spanning residues −38 to 281, including the 103-bp intron, of the VH26c gene (Fig. 1A). Southern blot analysis showed that the product amplified from hybridoma but not PMN DNA strongly hybridized with the [γ-32P]-labeled 66b′ oligonucleotide used as a probe (Fig. 5, mAb 412.66.F1, lane C). The DNA amplified from PMN was cloned. The sequences of seven independent isolates were identical to one another and to that of VH26c throughout the overlapping area (Fig. 1A, 412.66gl sequence). These experiments demonstrated that the mAb 412.66.F1 VH segment was somatically mutated and strongly suggested that it arose from a germ line gene identical to VH26c.

R mutations and Ag selection of the anti-DNA IgA mAb

In the absence of negative or positive selective pressure on a gene product, R and S mutations were randomly distributed throughout the coding sequence. If a DNA segment displays a number of R mutations higher than that expected by chance alone, it is likely that a positive pressure was exerted on the gene product to select for mutations. Conversely, if a DNA segment displays a number of R mutations lower than that expected by chance, it is likely that a positive pressure was exerted on the gene product to select against mutations such that the protein structure is preserved. We calculated the number of expected R mutations in the anti-DNA IgA mAb VH and VL segments using the formula n × Rf × CDRf or FRf, where n is the total number of observed mutations, Rf is the expected proportion of R mutations, and CDRf or FR is the relative size of the CDR or FR. In our calculations we substituted the general Rf value of 0.75, originally calculated by Jukes and King (58) for random hypermutation of a gene product that need not be conserved in structure, with the values we derived from the analysis of each individual putative germ-line VH or VL gene sequence (59), as listed in Table III. The introduced correction yields a more accurate estimate of the frequency of R mutations that were putatively selected by Ag because as a number of human Ig V gene segments display nucleotide sequences that are inherently more prone to R mutations. Relative sizes of the CDR and FR were 0.22 and 0.78, respectively, in the VI-3b, WHG16G, and VH26c genes; 0.23 and 0.77, respectively, in the VH2-MC2 and V71-2 genes; 0.20 and 0.80, respectively, in the HumKv325 gene; 0.19 and 0.81, respectively, in the kalc6 gene; and 0.24 and 0.76, respectively, in the YM-1 gene.

Table III.

Inherent R mutation frequency (Ri) of the sequences of the putative anti-DNA IgA1 autoantibody germ line VH and VL genesa

| Germ line VH Gene |

Germ line VH Gene |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAb | CDR | FR | CDR | FR | ||

| mAb 424.F6.24 | VI-3b | 0.8118 | 0.7504 | HumKv325 | 0.7713 | 0.7504 |

| mAb 447.8H7 | VH2-MC2 | 0.8020 | 0.7433 | HumKv325 | 0.7713 | 0.7504 |

| mAb 412.67.F1.3 | WHG16G | 0.8144 | 0.7376 | HumKv325 | 0.7713 | 0.7504 |

| mAb 412.66.F1 | VH26c | 0.7801 | 0.7423 | kalc6 | 0.8000 | 0.7549 |

| mAb 448.9G.F1 | V71-2 | 0.8177 | 0.7217 | YM-1 | 0.7831 | 0.7341 |

Consistent with selection by Ag, all mAb VH and VL segments but the VL segment of mAb 412.66.F1 displayed higher and lower numbers of R mutations in the CDR and FR, respectively, than those theoretically expected (Table II). The probability that the excess of putative and verified R mutations in the CDR or FR arose by chance was calculated according to the binomial distribution model p = [n!/k! (n-k)!] qk (l-q)n-k where q = probability a R mutation will localize to CDR or FR (q = CDRf or FRf × CDR or FR Rf) and k = number of observed R mutations in the CDR or FR (19). The likelihood that the excess of putative and verified R mutations in the CDR arose by chance was p = 0.241 (VH) and p = 0.127 (Vκ) in mAb 424.F6.24; p = 0.286 (VH) and p = 0.026 (Vκ) in mAb 447.8H; p = 0.00345 (VH) and p = 0.216 (Vκ) in mAb 412.67.F1.3; p = 0.0088 (VH) and no R mutations in mAb 412.66.F1 Vκ segment CDR; and p = 0.0015 (VH) and p = 0.000454 (Vλ) in mAb 448.9G.F1. The likelihood that the scarcity of putative and verified R mutations in the FR was due to chance was p = 0.006 (VH) and p = 0 (Vκ) in mAb 424.F6.24; p = 0.033 (VH) and p = 0.0162 (V κ) in mAb 447.8H; p = 0.0157 (VH) and p = 0.159 (Vκ) in mAb 412.67.F1.3; p = 0.0214 (VH) and p = 0 (Vκ) in mAb 412.66.F1; and p = 0.0132 (VH) and p = 0.000096 (Vλ) in mAb 448.9G.F1. Thus, the anti-DNA mAb-producing cells were under negative pressure to mutate the Ig V FR structure. mAb 412.67.F1.3-, 412.66.F1-, and 448.9G.F1-producing cells were under positive pressure to mutate the Ig V CDR structure.

Discussion

IgA account for less than 15% of the total circulating Ig but they represent the predominant Ig class in external secretions. They are crucial in protecting mucosal surfaces from invasion by infectious agents and in protecting, through colostrum, the suckling newborn from infection. In addition, IgA, mainly IgA1, provide autoantibodies in different autoimmune responses, including those in patients with SLE (27-31), IgA nephropathy (31), rheumatoid arthritis (60-62), dermatitis herpetiformis (63), linear IgA dermatosis (63), and, possibly, diabetes mellitus (64). In SLE patients, IgA autoantibodies contribute to IC formation and pathology. The present findings show that the structure of the IgA participating in the response to DNA reflect those of the anti-DNA IgG that are thought to dominate the autoimmune response in these patients. They also suggest that not only monoreactive but also polyreactive DNA binding IgA autoantibodies can accumulate somatic point mutations and possibly undergo an Ag-driven selection process.

The five anti-DNA IgA mAbs we generated used five distinct VH genes. With the exception of the WHG16G gene that gave rise to the mAb 412.67.F1.3 VH segment and that has not been reported, to our knowledge, to encode other anti-DNA antibodies, the assortment of the anti-DNA IgA mAb VH genes was similar to that of anti-DNA IgG and IgM antibodies. The germ-line (VHI) V-I3b gene that possibly gave rise to the mAb 424.F6.24 VH segment also encodes the anti-DNA IgM mAb 21/28 and mAb 8E10, isolated from patients with SLE and leprosy, respectively (6). The VH2-MC2, used by the mAb 447.8H, belongs to the same and relatively small family of genes (VHII) that provided the template for the anti-DNA IgM mAb T33-2 VH segment (65). Possibly somatically mutated variants of the (VHIV) V71-2 gene that likely gave rise to the mAb 448.9G.F1 VH segment encode three additional anti-DNA mAb, the IgG mAb T33-4 derived from a SLE patient (65), the IgG mAb 2A4 from a patient with multiple myeloma (14), and the IgM mAb C6B2 from a patient with sickle cell anemia (7). Somatically mutated variants of the (VHIII) VH26c gene that gave rise to the mutated anti-DNA IgA mAb 412.66.F1 VH segment encode the SLE-derived IgG mAb 32.B9 (16) and IgG mAb H2F (18), as well as the only other reported anti-DNA IgA, mAb 1X7RG1 (18). In addition, VH26c encodes in germ-line form a number of anti-DNA mAb including the IgM mAb 18/2 (6), mAb 18/7 (6), and mAb 46 (M. T. Kasaian and P. Casali, unpublished observations) from SLE patients. VH26c is one of the VH genes expressed in the developmentally restricted fetal repertoire (30p1) (48) and in the adult specifies the anti-DNA-related 16/6 idiotype (6, 43). Its use best exemplifies how the VH genes of the anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies belong to the same pool of genes used by not only other classes of anti-DNA autoantibodies but also those of other specific autoantibodies, natural antibodies, and specific antibodies induced by foreign Ag. For instance, virtually unmutated forms of the VH26c gene encode the natural polyreactive mAb18 (8) and the monoreactive anti-thyroglobulin mAb25 (8). Variously mutated forms of VH26c encode the monoreactive high affinity RF IgM RF-KL1 autoantibody (61) and the specific Abs induced by complex foreign Ag, even very different in nature, including the high affinity IgG mAb58 to rabies virus (66, 67) and the high affinity IgG mAb SB1/D8 to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide (68). Finally, at least three of the D genes, DxP′ 4, D21-7, and DN1, and the only JH gene used by the anti-DNA IgA mAb, JH4b, are predominantly expressed in the neonatal and adult B cell repertoires (47, 69), further emphasizing a relative lack of restriction in the Ig gene utilization by the anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies.

Four of the five IgA anti-DNA autoantibodies used Vκ segments that are associated with RF activity. Three (mAb 424.F6.24, mAb 447.8H, and mAb 412.67.F1.3) Vκ segments constituted variously mutated forms of a germ-line VκIII gene, HumKv325, which along with another VκIII gene, HumKv328, encode a variety of RF in healthy subjects and rheumatoid patients (36, 52, 70); the fourth (mAb 412.66.F1) Vκ segment probably constituted the expression of the same VκI germ-line gene encoding the IgG RF kalc6 (52). The use of RF-related Vκ segments was complemented by the presence of nontemplated nucleotides encoding Pro or Tyr-Pro residues at the Vκ-Jκ junctions, similar to those that we (36) and others (71) have reported in the Vκ segments of RF isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The failure of the anti-DNA IgA mAb with RF-associated Vκ segments (mAb 424.F6.24, mAb 447.8H, mAb 412.67.F1.3, and mAb 412.66.F1) to display any RF-like activity (Fig. 1) is consistent with the major role of the Ig VH segment in DNA (72, 73), and, possibly, IgG (77) binding.

The notable overlap of the V genes used by these IgA and the reported IgG or IgM autoantibodies to DNA, as well as natural Abs and foreign Ag-induced Abs suggest that V gene polymorphism is not required for high affinity DNA binding. Anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies may arise from natural IgM Abs through a process of affinity maturation, as exemplified by the verified clonal relationship between anti-DNA IgG and IgM autoantibody-producing cells in (NZB × NZW)F1 mice (22). Affinity maturation entails preferential accumulation of R mutations in CDR over FR and high CDR R:S mutation ratios in clonotypes that underwent clonal expansion and selection, dependent on the specificity of the surface receptor for Ag, and resulting in the production of Abs with better fit for the inducing Ag. The somatically mutated status of not only the monoreactive DNA-specific IgA mAb 412.67.F1.3 but also of the polyreactive DNA binding IgA mAb 412.66.F1 was ascertained and the autologous putative germ-line genes that gave rise to them were identified. Consistent with an Ag-driven selection, the mAb 412.67.F1.3 and mAb 412.66.F1 IgA VH segments displayed overall CDR and FR R:S mutation ratios of 13:0 (all CDR base changes were R mutations) and 1.0, respectively. These quotients are at least comparable to those of the V genes of some high affinity anti-DNA and other self-Ag autoantibodies, as well as of foreign Ag-induced IgG and IgA Abs that underwent a process of affinity maturation in humans and mice (15-22, 36, 67, 75-79). Likewise, the VH gene that encoded the polyreactive mAb 448.9G.F1 constituted a somatically mutated form of the V71-2 gene, displaying putative CDR and FR R:S mutation ratios of 8:0 (all CDR base changes were R mutations) and 1.0, respectively. The demonstration of somatic point mutations in the polyreactive anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies extends our previous observations of somatic hypermutation in polyreactive IgG mAb (80) and further questions the accepted notion that polyreactivity is a function of germ-line Ig V genes. It also suggests that polyreactivity, which has been long considered associated primarily with natural IgM Abs but not pathogenic autoantibodies, may in fact represent an originally inherent feature of a large proportion of natural DNA binding autoantibodies that underwent an Ag selection process and possibly acquired pathogenic potential.

The analysis of reported human anti-DNA Abs shows that there is no single paradigm for explaining structural or molecular genetic features of these autoantibodies (6-10, 14-18, 65, 81). However, the unique characteristics of DNA make it particularly suited for binding by certain amino acids. From the structural analysis of DNA binding proteins (59) and that of murine anti-DNA autoantibodies (17-22, 72, 73, 82), it has been proposed that the positively charged amino acid residues Arg, Lys, and His play an important role in DNA binding by interacting electrostatically with the DNA phosphate backbone. In addition, Arg can form hydrogen-bonds with base-paired guanine and unpaired and base-paired cytosine. It is considered the most efficient amino acid to mediate binding to DNA and has been found to be a dominant substituted residue in murine anti-DNA Abs (19-22). The polar residues Asn, Gln, and, possibly, Tyr and Thr could also bind DNA by virtue of their ability to form hydrogen bonds with purine and pyrimidine bases (65, 81-83). In the five anti-DNA IgA mAb, the putative and verified R mutations yielded a total of 68 amino acid replacements: 41 in the VH and 27 in the V L segments. Twenty amino acid replacements in the VH and 18 in the VL segments were nonconserved. Of the total 38 putative and verified nonconserved amino acid changes, 14 were positively charged residues (seven Arg, five Lys, two His), three were Tyr, two Gln, and a Thr. In the mAb 412.67.F1.3 an additional change to Arg was present in the Vκ segment CDR3 portion contributed by the 5′ sequence of the Jκ1 gene. The conserved amino acid changes included an Arg, a Lys, seven Asn, four Thr, and a Tyr.

Although in vitro mutagenesis of the murine anti-DNA Ab VH3H9 segment has clearly shown that one to three Arg residue substitutions result in additive contributions to DNA binding (72), a high frequency of Arg substitutions has been found in the VH and/or VL segments of some human anti-DNA autoantibodies but not others (81). A total of nine Arg substitutions (including that at position 97 of the mAb 412.67.F1.3 Vκ CDR3 contributed by the Jκ sequence) were present in the VH and/or VL segments of four IgA mAb (mAb 447.8H, mAb 412.67.F1.3, mAb 412.66.F1, and mAb 448.9G.F1). Five Arg substitutions were in the Ag contact areas, i.e., CDR, two were at residues immediately preceding (position 30 of the mAb 412.66.F1 VH segment) or after a CDR (position 58 of the mAb 412.67.FL3 VκIII segment) and two were in VH segment FR3 sequence (mAb 447.8H at positions 73 and 79), which has also been implicated in DNA binding (15). These Arg were complemented by a total of four Arg in the somatically generated heavy chain CDR3. As a result of the somatic hypermutation and/or original composition of the heavy chain CDR3, the monoreactive mAb 412.67.F1 and the polyreactive mAb 448.9G.F1, which displayed the highest relative avidities for DNA (8.0 × 10–10 and 2.2 × 10–9 g/μl, respectively), contained four and three Arg, respectively. However, the monoreactive mAb 447.8H, which displayed the lowest Avrel for DNA (7.5 × 10–8 g/μl), contained three Arg substitutions in the V segments and two Arg in the heavy chain CDR3; the mAb 424.F6.24, which displayed an Avrel for DNA of 7.0 × 10–9 g/μl, contained no Arg substitutions in the V segments nor did it display any Arg in the heavy chain CDR3.

Thus, in the anti-DNA IgA mAb, the number of Arg substitutions did not directly correlate with DNA binding strength. This can be explained in at least four different ways. 1) The DNA binding of some of the Arg residues can be neutralized by the presence of immediately adjacent different amino acids, as suggested by the analysis of the mutagenized K64R variant of the murine VH3H9 segment in which the potential DNA binding activity of the Arg at position 64 was putatively neutralized by the Asp at position 65 (72). Interestingly, two of the three Arg substitutions in the relatively low avidity mAb 447.8H were flanked by Asp, Arg 73 was flanked with an Asp at position 74 in the VH segment FR3, and Arg 94 was flanked by the substituted Asp at position 93 in the VκIII segment. 2) Other amino acid substitutions may play a major rather than an ancillary role in complementing the DNA binding activity of Arg. For example, the most efficient DNA binding IgA, mAb 412.67.F1.3, displayed, in addition to Arg substitutions, an Asn-Thr-Asn triplet mutation in the VH segment CDR2 and an additional Asn in the heavy chain CDR3. The other mAb with comparable high affinity for DNA, the polyreactive anti-ssDNA and anti-dsDNA mAb 448.9G.F1, displayed, in addition to the three Arg substitutions in the VH and VλI CDR, two Thr and one Lys in the VH segment CDR2 and two Lys and two Tyr in the VλI segment CDR. Finally, mAb 424.F6.24 that accumulated no Arg substitutions and lacked any Arg in the heavy chain CDR3 displayed three Asn substitutions in the VH and VκIII segments and two Asn in the heavy chain CDR3. 3) As suggested by Diamond and Scharff (84) and more recently by Radic et al. (72), the substitution of a single amino acid can result in acquisition or loss of DNA binding. The polyreactive mAb 412.66.F1 with an RF Vκ chain (kalc6) in unmutated configuration and displaying no Arg in the heavy chain CDR3 might use for dsDNA binding the VH segment Arg 30, perhaps complemented in activity by the heavy chain CDR3 Thr, His, or Tyr, and the VH segment CDR1 Thr (at position 35) and/or CDR2 Tyr (at position 56) substitutions. 4) Finally, certain Arg residues may affect Ab DNA binding properties other than the relative rate of dissociation, as measured in the present mAb, such as a higher rate of association with Ag (kon), which has been shown to be a dominant feature of high affinity anti-phenyl-oxazolone in the tertiary response (85). A high kon may be critical for the rapid IC formation in vivo and was not measured here.

In vitro Ig V gene expression experiments and the inspection of the structure of 84 Abs with different specificities have suggested that, in addition to VH and/or VL segments, the somatically generated heavy chain CDR3 can provide the major structural correlate for binding to Ag (74, 86). Thus, in the anti-DNA IgA rnAb the positively charged residues or the DNA binding polar residues arising from somatic hypermutation in the VH and VL segments possibly complemented the activity of similar residues present in the mAb heavy chain CDR3. The VH segments of the monoreactive anti-ssDNA mAb 424.F6.24 and mAb 447.8H bore relatively few putative R mutations in the CDR. In these two mAb and the monoreactive anti-ssDNA and dsDNA mAb 412.67.F1.3, positively charged residues and Asn, Gln, Tyr, and/or Thr comprised 50, 66, and 61%, respectively, of the heavy chain CDR3 amino acids compared with 21 and 20% of similar residues in the two polyreactive anti-DNA IgA mAb 412.66.F1 and mAb 448.9G.F1 heavy chain CDR3, respectively. In all anti-DNA IgA mAb but mAb 447.8H, a Tyr was the terminal residue of the heavy chain CDR3 (Fig. 2B). Some of the DNA binding amino acids in the heavy chain CDR3 of the monoreactive IgA mAb might have arisen from somatic hypermutation but others, perhaps most of them, would have been encoded in the somatically generated VH-D-JH junction gene sequence. As such, they would have existed before and could have provided the structural correlate for the initial selection by Ag. Similarly, the heavy chain CDR3 of the two polyreactive IgA mAb might have also initially provided some DNA binding affinity and the basis for selection by Ag of the respective Ab-producing cell clones. The inherent original affinity for DNA of the polyreactive IgA Abs would have been increased through progressive selection by Ag of the emerging amino acid replacements in the V segments. The Ag and the other factors operating in such selection process remain to be determined.

Acknowledgment

We thank Ms. Nancy Pacheco for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service Grant AR-40908 and by Grant BRSC S07 RR05399-30 awarded by the Biomedical Research Support Grant Program, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. P.C. is a Kaplan Cancer Scholar. This is publication 20 from The Jeanette Greenspan Laboratory for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations used in this paper: IC, immune complex; Avrel relative avtdity; CDR, complementarity-determining region; FR, framework region; PMN, polymorphonuclear cells; R, replacement (mutation); RF, rheumatoid factor; S, silent (mutation).

References

- 1.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv. Immunol. 1989;44:93. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zouali M, Stollar BD, Schwartz RS. Origin and diversification of anti-DNA antibodies. Itnmunol. Rev. 1988;105:137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Ueki Y, Larrick JW, Notkins AL, Casali P. Probing the normal and autoimmune B cell repertoire with Epstein-Barr virus: frequency of B cells producing monoreactive high affinity autoantibodies in patients with Hashimoto's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 1988;141:4165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casali P, Burastero SE, Balow JE, Notkins AL. High affinity antibodies to ssDNA are produced by CD5− B cells in SLE patients. J. Immunol. 1989;143:3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki N, Sakane R, Engleman EG. Anti-DNA antibody production by CD5+ and CD5− cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:238. doi: 10.1172/JCI114418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dersimonian H, Schwartz RS, Barrett KJ, Stollar BD. Relationship of human variable region heavy chain germ-line genes to gene encoding anti-DNA autoantibodies. J. Immunol. 1987;139:2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoch S, Schwaber J. Identification and sequence of the VH gene elements encoding a human anti-DNA antibody. J. Immu-nol. 1987;139:1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanz I, Casali P, Thomas JW, Notkins AL, Capra JD. Nucleotide sequences of eight human natural autoantibody VH regions reveals apparent restricted use of VH families. J. Immunol. 1989;142:4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dersimonian H, McAdam KPWJ, Mackworth-Young C, Stollar BD. The recurrent expression of variable region segments in human IgM anti-DNA autoantibodies. J. Immunol. 1989;142:4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns E, Kwong PC, Misener V, Ip P, Bell DA, Siminovitch KA. Analysis of the variable region genes encoding a human anti-DNA antibody of normal origin. Implication for the molecular basis of human autoimmune responses. J. Immunol. 1989;143:685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual V, Capra JD. Human immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region genes: organization, polymorphism and expression. Adv. Immunol. 1991;49:l. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riboldi P, Kasaian MT, Mantovani L, Ikematsu H, Casali P. In: Natural antibodies. In The Molecular Pathology of Autoimmunity. Bona CA, Siminovitch K, Zanetti M, Theophilopoulos AN, editors. Harwood Academic Publishers; Langhorne, PA: 1993. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harindranath N, Ikematsu H, Notkins AL, Casali P. Structure of the VH and VL segments of polyreactive and monore-active human natural antibodies to HIV-1 and E. coli β-galactosidase. Int. Immunol. 1993;5:1523. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.12.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson A, Manheimer-Lory A, Aranow C, Peterson R, Hannigan N, Diamond B. Molecular characterization of a somatically mutated anti-DNA antibody bearing two systemic lupus crythematosus-related idiotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:1401. doi: 10.1172/JCI114584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Es JH, Gmelig Meyling FHJ, van de Akker WRM, Aanstoot H, Derksen RHWM, Logtenberg T. Somatic mutations in the variable regions of a human IgG anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibody suggest a role for antigen in the induction of systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:461. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkler TH, Fehr H, Kalden JR. Analysis of immunoglobulin variable region genes from human IgG anti-DNA hybridomas. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:1719. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Es JH, Aanstoot H, Gmelig-Meyling FHJ, Dersken RHWM, Logtenberg T. A human systemic lupus erythematosus-related anti-cardiolipin/single stranded DNA autoantibody is encoded by a somatically mutated variant of the developmentally restricted SIP1 VH gene. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manheimer-Lory A, Katz JB, Pillinger M, Ghossein C, Smith A, Diamond B. Molecular characteristics of antibodies bearing an anti-DNA-associated idiotype. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:1639. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shlomchik MJ, Aucoin AH, Pisetsky DS, Weigert MG. Structure and function of anti-DNA autoantibodies derived from a single autoimmune mouse. Proc. Nutl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:9150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shlomchik M, Mascelli M, Shan H, Radic MZ, Pisetsky D, Marshak-Rothstein A, Weigert MG. Anti-DNA antibodies from autoimmune mice arise by clonal expansion and somatic mutation. J. Exp. Med. 1990;171:265. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behar SM, Lustgarten DL, Corbet S, Scharff MD. Characterization of somatically mutated S107 VHll-encoded anti-DNA autoantibodies derived from autoimmune (NZB × NZW)F1 mice. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:731. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tillman DM, Jou N-T, Hill RJ, Marion TN. Both IgM and IgG anti-DNA antibodies are the products of clonally selective B cell stimulation in (NZB × NZW)F1 mice. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:761. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winfield JB, Faifermen I, Koffler D. Avidity of anti-DNA antibodies in serum and IgG glomerular eluates in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: association of high avidity anti-DNA antibody with glomerulonephritis. J. Clin. Invest. 1977;59:90. doi: 10.1172/JCI108626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson L, Lightfoot RW., Jr. Correlation of DNA-anti-DNA association rates with clinical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 1981;126:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallenberg CGM, ter Borg EJ, Horst G, Hummel F, Limburg PC. Predictive value of anti-double stranded DNA antibody levels in SLE: a long term prospective study. Clin. Rheumatol. 1989;8:49. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raz E, Brezis M, Rosenmann E, Eilat D. Anti-DNA antibodies bind directly to renal antigens and induce kidney dysfunction in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J. Immunol. 1989;142:3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall RP, Lawley TJ, Heck JA, Katz SI. IgA-containing circulating immune complexes in dermatitis herpetiformis, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1980;40:431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rifai A, Millard K. Glomerular deposition of immune complexes prepared with monomeric or polymeric IgA. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1985;60:363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gripenherg M, Helve T. Anti-DNA antibodies of the IgA class in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol. Int. 1986;6:53. doi: 10.1007/BF00541504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingsmore SF, Thompson JM, Crockard AD, Todd D, McKirgan J, Patterson C, Fay AC, McNeill TA. Measurement of circulating immune complexes containing IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE by flow cytometry: correlation with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Clin. Lab. Immunol. 1989;30:45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Amico G. The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q. J. Med. 1987;64:709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ootaka T, Suzuki M, Sudo K, Sato H, Seino J, Saito T, Yoshinaga K. Histologic localization of terminal complement complexes in renal diseases: an immunohistochemical study. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1989;91:144. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Notkins AL, Casali P. Human monoclonal rheumatoid factor-like antibodies from CD5 (Leu-1)+ B cells are polyreactive. J. Immunol. 1988;140:4180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasaian MT, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Identification and analysis of a novel human surface CD5− B lymphocyte subset producing natural antibodies. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura M, Casali P. Generation of human monoclonal antibody-producing cell lines by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformation of autoreactive B lymphocytes and by somatic cell hybridization techniques: application to the analysis of the autoimmune B cell repertoire. Immunomethods. 1992;1:159. doi: 10.1016/S1058-6687(05)80012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantovani L, Wilder RL, Casali P. Human rheumatoid B-la (CD5+ B) cells make somatically hypermutated high affinity IgM rheumatoid factors. J. Immunol. 1993;151:473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parson WR. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:63. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin EK, Matsuda F, Nagaoka H, Fukita Y, Imai T, Yokoyama K, Soeda E, Honjo T. Physical map of the 3′ region of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain locus: clustering of autoantibody-related variable segments in one haplotype. EMBO J. 1991;10:3641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell MJ, Zelenetz AD, Levy S, Levy R. Use of family specific leader region primers for PCR amplification of the human heavy chain variable region gene repertoire. Mol. Immunol. 1992;29:193. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90100-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi N, Noma T, Honjo T. Rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (VH) pseudogene that deletes the second complementarity-determining region. Proc. Narl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:5194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder HW, Jr., Wang JY. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuppers R, Fischer U, Rajewski K, Gause A. Immunoglobulin heavy and light chain gene sequences of a human CD5 positive immunocytoma and sequences of four novel VHIII germline genes. Immunol. Lett. 1992;34:57. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen PP, Liu M-F, Sinha S, Carson DA. A 16/6 idiotype-positive anti-DNA antibody is encoded by a conserved VH gene with no somatic mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1429. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee KH, Matsuda F, Kinashi T, Kodaira M, Honjo T. A novel family of variable region genes of the human immunoglohulin heavy chain. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:761. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichihara Y, Matsuoka H, Kurosawa Y. Organization of human immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci. EMBO J. 1988;7:4141. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buluwela L, Alhertson DG, Sherrington P, Rahbitts PH, Spurr N, Rahhitts TH. The use of chromosomal translocations to study human immunoglobulin gene organization: mapping DH segments within 35 kb of Cμ gene and identification of a new DH locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:2003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada M, Wasserman R, Richard BA, Shane S, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:395. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder HW, Jr., Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Early restriction of the human antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:791. doi: 10.1126/science.3118465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravetch JV, Siehenlist U, Korsmeyer S, Waldmann T, Leder P. Structure of the human immunoglobulin m locus: characterization of embryonic and rearranged J and D genes. Cell. 1981;27:583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. 5th Ed. U S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC.: 1991. p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kipps TJ, Tomhave E, Chen PP, Carson DA. Autoantibody-associated kappa light chain variable region gene expressed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with little or no somatic mutation: implications for etiology and immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:840. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ermel RW, Kenny TP, Chen PP, Rohbins DL. Molecular analysis of rheumatoid factors derived from rheumatoid synovium suggests an antigen-driven response in inflamed joints. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:380. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bentley DL, Rabbitts TH. Human immunoglobulin variable regions genes-DNA sequences of two V(k) genes and a pseudogene. Nature. 1980;288:730. doi: 10.1038/288730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsunetsusu-Yokota Y, Minekawa T, Shigemoto K, Shirasawa T, Takemori T. Characterization of a new subgroup of human 1g V1 cDNA clone and its expression. Mol. Immunol. 1992;29:723. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90182-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berinstein N, Levy S, Levy R. Activation of an excluded immunoglobulin allele in a human B lymphoma cell line. Science. 1989;244:337. doi: 10.1126/science.2496466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hieter PA, Maizel JV, Jr., Leder P. Evolution of human immunoglobulin k J region genes. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Udey JA, Blomberg B. Human A light chain locus: organization and DNA sequences of three genomic J regions. Immunogenetics. 1987;25:63. doi: 10.1007/BF00768834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jukes TH, King JL. Evolutionary nucleotide replacements in DNA. Nature. 1979;281:605. doi: 10.1038/281605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang B, Casae P. A structural source of Ig V gene hypervariability, A major proportion of human germline VH gene display CDRI inherently susceptible to amino acid replacement. Immunol. Today. 1994 doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90175-9. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pillemer SR, Reynolds WJ, Yoon SJ, Perera M, Newkirk M, Klein M. IgA related disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1987;14:880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pascual V, Randen I, Thompson K, Sioud M, Ferre O, Natvig J, Capra JD. The complete nucleotide sequences of the heavy chain variable regions of six monospecific rheumatoid factors derived from Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells isolated from the synovial tissue of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Ciin. Invest. 1990;86:1320. doi: 10.1172/JCI114841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harindranath N, Goldfarb IS, Ikematsu H, Burastero SE, Wilder RL, Notkins AL, Casali P. Complete sequence of the genes encoding the VH and VL-regions of low and high-affinity monoclonal IgM and IgAl rheumatoid factors produced by CDS+ B cells from a rheumatoid arthritis patient. Int. Immunol. 1991;3:865. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.9.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yancey KB, Lawley TJ. In: The immunology of the skin. In Allergy: Principles and Practice. 3rd Ed. Middleton E, Reed CE, Ellis EF, editors. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1988. pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Triolo G, Giardina E, Rinaldi A, Bompiani GD. IgA and insulin-containing (C3-fixing) circulating immune complexes in diabetes mellitus. Ciin. Immunoi. Immunopathoi. 1984;30:169. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(84)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zouali M. Development of human antibody variable genes in systemic autoimmunity. Immunoi. Rev. 1992;128:73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ueki Y, Goldfarb IS, Harindranath N, Gore M, Koprowski H, Notkins AL, Casali P. Clonal analysis of a human antibody response: quantitation of precursors of antibody-producing cells and generation and characterization of monoclonal IgM, IgG and IgA to rabies virus. J. Enp. Med. 1990;171:19. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikematsu H, Harindranath N, Ueki Y, Notkins AL, Casali P. Clonal analysis of a human antibody response. II. Sequences of the VH genes of human monoclonal IgM, IgG, and IgA to rabies virus reveal preferential utilization of VHIII segments and somatic hypermutation. J. Immunoi. 1993;150:1325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Caroll WL. Restricted Ig H chain V gene usage in the human antibody response to Haemophilus infienzae type b capsular polysaccharide. J. Immunol. 1991;147:1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mortari F, Wang J-Y, Schroeder HW., Jr. Human cord blood antibody repertoire. Mixed population of VH gene segments and CDR3 distribution in the expressed Cα and Cγ repertoires. J. Immunol. 1993;150:1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pascual V, Victor K, Randen I, Thomson K, Steinitz M, Forre O, Fu S-M, Natvig IB, Capra JD. Nucleotide sequence analysis of rheumatoid factors and polyreactive antibodies derived from patients with rheumatoid arthritis reveals diverse use of VH and VL gene segments and extensive variability in CDR3. Scand. J. Immunol. 1992;36:349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin T, Blaison G, Levallois H, Pasquali JL. Molecular analysis of the VκIII-Jκ junctional diversity of polyclonal rheumatoid factors during rheumatoid arthritis frequently reveals N addition. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:1773. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Radic MZ, Mackle J, Erikson J, Mol C, Anderson WF, Weigert M. Residues that mediate DNA binding of autoimmune antibodies. J. Immunoi. 1993;150:4966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Radic MZ, Mascelli MA, Erikson J, Shan H, Weigert M. Ig H and L chain contrihutions to autoimmune specificities. J. Immunol. 1991;146:176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martin T, Duffy SF, Carson DA, Kipps TJ. Evidence for somatic selection of natural antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1992;175:983. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McKean D, Huppi K, Bell M, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert M. Generation of antibody diversity in the immune response of Balb/c mice to influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:3180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Clarke HS, Huppi K, Ruezinsky D, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert M. Inter- and intraclonal diversity in the antibody response to influenza hemagglutinin. J. Exp. Med. 1985;161:687. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.4.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berek C, Milstein C. Mutation drift and repertoire shift in the maturation of the immune response. Immunol. Rev. 1987;46:23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Malipiero UV, Levy NS, Gearhart PJ. Somatic mutation in anti-phosphorylcholine antibodies. Immunol. Rev. 1987;46:59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ikematsu H, Schettino EW, Nakamura M, Casali P. VH and Vκ segment structure of anti-insulin IgG autoantibodies in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: evidence for somatic selection. J. Immunol. In Press. 1994 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ikematsu H, Kasaian MT, Schettino EW, Casali P. Structural analysis of the VH-D-JH segments of human polyreactive IgG mAb. Evidence for somatic selection. J. Immunoi. 1993;151:3604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Diamond B, Katz JB, Paul E, Aranow C, Lustgarten D, Scharff MD. The role of somatic mutation in the pathogenic anti-DNA response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1992;10:731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.003503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eilat D, Fischel R. Recurrent utilization of genetic elements in V regions of antinucleic acid antibodies from autoimmune mice. J. Immunoi. 1991;147:361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seeman NC, Rosenberg JM, Rich A. Sequence-specific recognition of double helical nucleic acids by proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Diamond B, Scharff MD. Somatic mutation of the T15 heavy chain gives rise to an antibody with autoantibody specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Foote J, Milstein C. Kinetic maturation of an immune response. Nature. 1991;352:530. doi: 10.1038/352530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen C, Stenzel-Poore MP, Rittenberg MB. Natural auto- and polyreactive antibodies differing from antigen-induced antibodies in the H chain CDR3. J. Immunoi. 1991;147:2354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]