Abstract:

To improve our understanding of the evidence-based literature supporting temperature management during adult cardiopulmonary bypass, The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiology and the American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology tasked the authors to conduct a review of the peer-reviewed literature, including 1) optimal site for temperature monitoring, 2) avoidance of hyperthermia, 3) peak cooling temperature gradient and cooling rate, and 4) peak warming temperature gradient and rewarming rate. Authors adopted the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association method for development clinical practice guidelines, and arrived at the following recommendation.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary bypass, perfusion, temperature management, cardiopulmonary bypass neurologic morbidity

CLASS I RECOMMENDATIONS

The oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature is recommended to be used as a surrogate for cerebral temperature measurement during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). (Class I, Level C)

To monitor cerebral perfusate temperature during warming, it should be assumed that the oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature underestimates cerebral perfusate temperature. (Class I, Level C)

Surgical teams should limit arterial outlet blood temperature to <37°C to avoid cerebral hyperthermia. (Class I, Level C)

Temperature gradients between the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB cooling should not exceed 10°C to avoid generation of gaseous emboli. (Class I, Level C)

Temperature gradients between the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB rewarming should not exceed 10°C to avoid outgassing when blood is returned to the patient. (Class I, Level C)

CLASS IIA RECOMMENDATIONS

Pulmonary artery (PA) or nasopharyngeal temperature recording is reasonable for weaning and immediate postbypass temperature measurement. (Class IIa, Level C)

- Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature ≥30° C:

- To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a temperature gradient between arterial outlet temperature and the venous inflow of ≤4°C. (Class IIa, Level B)

- To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a rewarming rate ≤.5°C/min. (Class IIa, Level B)

Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature <30°C: to achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a maximal gradient of 10°C between arterial outlet temperature and venous inflow. (Class IIa, Level C)

NO RECOMMENDATION

No recommendation for a guideline is provided concerning optimal temperature for weaning from CPB due to insufficient published evidence.

Numerous strategies are currently invoked by perfusion teams to manage the requirements of cooling, temperature maintenance, and rewarming patients during cardiac surgical procedures. To date there have been very few evidence-based recommendations for the conduct of temperature management during perfusion. Although Bartels et al. (1) found no supporting evidence for an evidence-based guideline for managing the temperature gradient during CPB, Shann et al. (2) recommended that “limiting arterial line temperature to 37°C might be useful for avoiding cerebral hyperthermia,” including checking “coupled temperature” ports for all oxygenators for accuracy and calibration (Class IIa, Level B).

Owing to differences in interpreting the literature and the paucity of published guidelines in this clinical area, there is extensive variability in the conduct of managing perfusate temperature during CPB. A recent survey of perfusionists found that 1) in more than 90% of centers, mildly hypothermic perfusion of 32°C to 34°C is routinely used and 63% achieve that temperature without active cooling; 2) during CPB, the most common sites for measuring temperature are nasopharyngeal (NP, 84%), venous return (75%), arterial line (72%), bladder (41%), and rectum (28%); 3) 19% of centers reported routinely calibrating their in-line temperature probes; and 4) 44% of centers exceed the 37°C peak temperature limit for the arterial line temperature during rewarming (3). Although temperature management strategies are frequently reported in the literature, the rationale for these practices is often underreported or absent.

To improve our understanding of the evidence-based literature supporting temperature management, we conducted a review of the peer-reviewed literature, including 1) optimal site for temperature monitoring, 2) avoidance of hyperthermia, 3) peak cooling temperature gradient and cooling rate, and 4) peak warming temperature gradient and rewarming rate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search

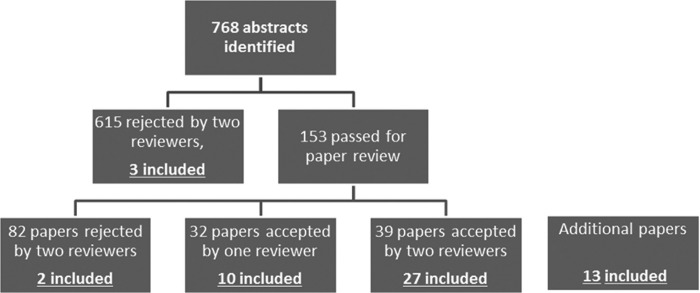

We used a systematic search of Medical Subject Heading terms to identify peer-reviewed articles related to temperature management in the setting of adult CPB (Appendix). Candidate articles were published in PubMed between January 1, 2000 and March 31, 2014. Our search revealed 768 abstracts, all of which were reviewed in duplicate by independent reviewers, with 153 abstracts selected for full paper review. To be included, each paper had to report data on each of the following: 1) optimal site for temperature monitoring, 2) avoidance of hyperthermia, 3) peak cooling temperature gradient and cooling rate, and 4) peak warming temperature gradient and rewarming rate.

According to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) rules (Table 1), any reviewer could select an abstract for inclusion in a paper review, but at least two reviewers had to agree to exclude a paper (4). At the paper review stage, at least two reviewers had to agree to exclude a paper. These rules were incorporated into Guideliner reviewing software (www.guideliner.org/default.aspx, accessed May 20, 2014). Thirteen articles considered relevant to the topic by the authors were included to provide method, context, or additional supporting evidence for the recommendations.

Table 1.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association: Classifications and level of evidence (4).

| Classification | Clinical recommendation |

|---|---|

| Class I | Benefit >>> risk |

| Conditions for which there is evidence and/or general agreement that a given procedure or treatment is useful and effective | |

| Class II | Conditions for which there is conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of a procedure or treatment. This is classified as IIa or IIb |

| Class IIa | Benefit >> risk |

| Weight of evidence/opinion is in favor of usefulness/efficacy | |

| Class IIb | Benefit ≥ risk |

| Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion | |

| Class III | Risk > benefit |

| Conditions for which there is evidence and/or general agreement that the procedure/treatment is not useful/effectiv and in some cases may be harmful. This is defined as: no benefit—procedure/test not helpful or treatment withou established proven benefit; harm—procedure/test/treatment leads to excess cost without benefit or is harmful | |

| Level of evidence | Type of evidence |

| Level A | Evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses |

| Level B | Evidence from single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies |

| Level C | Evidence from expert opinion, case studies, or standard of care |

RESULTS

Synthesizing the Evidence

Two reviewers rejected 615 abstracts based on a lack of relevance, leaving 153 abstracts for full paper review (Figure 1). Two panel members reviewed each paper, and 82 of these papers were found not to contribute to the topic by both reviewers, a further 32 had conflicting reviews and were individually resolved, and the final 39 were considered for inclusion in the guideline. Of the additional 13 articles relevant to the development of the Guideline 8 predated 2000.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrates the pathway of abstracts identified by the search strategy. Literature has been included in final selection (included) from various levels of the review process, including 13 papers not identified in the original search strategy.

Optimal Site for Temperature Measurement

A number of sites for routine core and cerebral temperature management have been reported, including NP, tympanic membrane, bladder, esophagus, rectum, PA, jugular bulb (JB), arterial inflow, and venous return (3). A single, easily monitored, optimal core temperature site has not been reported, although the intravascular and intracorporeal location of a PA catheter probably renders this site the best access for core temperature recording. However, PA catheters are used infrequently in many centers, necessitating a different core temperature measurement site. The measurement of the JB temperature is recognized as being the best indicator of cerebral temperature (5,6), but it is not routinely used as a monitor and its accuracy depends on the optimal positioning of this invasive temperature probe (6).

Akata et al. (7), in a study to evaluate monitoring of brain temperature during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, compared five sites with JB monitoring. The authors recommended the use of PA and NP locations for estimating cerebral temperature rather than forehead, bladder, and fingertip sites. Bladder and rectal temperatures are unreliable indicators of cerebral temperature during CPB and may be as much as 2°C to 4°C lower than the brain temperature when rewarming during CPB (6). Thus, use of NP temperature monitoring is preferable to bladder or rectal temperatures during rewarming to avoid potential cerebral hyperthermia (8–10).

Johnson et al. (11) highlighted, in a prospective study of 80 patients, the disparity in temperature measurement between the NP temperature and the arterial outlet temperature. In 2004, Kaukuntla et al. (12) demonstrated that commonly used core temperature monitoring sites (bladder, esophageal, and NP) were not accurate measures of cerebral temperature where JB temperature is used as the gold standard. The authors concluded that arterial outlet temperatures should be monitored to avoid cerebral hyperthermic inflow. Nussmeier et al. (6,8) demonstrated that arterial blood outlet temperature measurement provided the best correlate with JB temperature, followed by NP and esophageal locations. Nussmeier et al. (6) also demonstrated that all body sites overestimated JB temperature during cooling and underestimated JB temperature during rewarming, reporting that, “the arterial outlet site had the smallest average discrepancy of all temperature sites relative to the JB site.”

The accuracy of arterial blood outlet-coupled temperature ports has been reported in clinical and in vitro studies (13–16). These studies have consistently demonstrated variation between the temperature measured at the arterial outlet and a reference temperature measurement (a temperature probe placed distally within the circuit). Newland et al. (14) measured the arterial outlet temperature accuracy in four different oxygenators and reported that at 37° C, the arterial outlet temperature measurement underestimated the reference thermometer temperature by between .33°C and .67° C. These studies suggest that the maximum arterial blood outlet temperature target should be lower than 37°C to avoid perfusing the patient with blood temperatures higher than 37° C. Such corrections must be considered when using arterial outlet temperature as a surrogate site to monitor cerebral temperature.

After equilibration of core temperature after CPB, bladder temperature has been recommended as a good, noninvasive approach for monitoring core temperature (17). Bladder temperature probes have been shown to be reliable and correlate well with PA catheters in reflecting core body temperature in children (18). Khan et al. (19) demonstrated that tympanic membrane and axillary temperature measurements did not accurately reflect bladder temperature after CPB and suggested that clinical decisions should not be based on the former two temperature measurements.

Recommendation:

The oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature is recommended to be used as a surrogate for cerebral temperature measurement during CPB. (Class I, Level C)

To accurately monitor cerebral perfusate temperature during warming, it should be assumed that the oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature underestimates cerebral perfusate temperature. (Class I, Level C)

PA or NP temperature recording is reasonable for core temperature measurement. (Class IIa, Level C)

Avoidance of Hyperthermia

Avoidance of cerebral hyperthermia in the setting of CPB has been promoted to avoid cerebral injury (10,12,20–22). Scheffer and Sanders (10) highlight that although the independent relationship between cerebral hyperthermia during CPB and neurologic injury has not been unequivocally proven, sufficient and compelling indirect evidence supports extreme caution. Shann et al. (2) applied evidence from the stroke literature to support a recommendation to limit the arterial blood outlet temperature to 37°C to avoid cerebral hyperthermia. Several reports have noted the association of increased cerebral temperature and rapid CPB rewarming with JB desaturation (23–25). Numerous authors have suggested that cerebral temperatures higher than 37°C should be avoided at any time during the rewarming phase of CPB and that this may be performed by careful monitoring and maintenance of arterial blood outlet temperatures lower than 37°C (15,20–22,26).

Grocott et al. (27) evaluated the effect of intraoperative temperature management in a randomized trial of 300 patients and found that the maximum postoperative temperature was weakly associated with increased cognitive dysfunction at 4–6 weeks. Hyperthermia has also been reported to influence other outcomes after cardiac operations. Groom et al. (28) reported an association with hyperthermia (defined as a peak core temperature >37.9° C) and an increased rate of mediastinitis. Newland et al. (29) reported in 2013 that an arterial outlet temperature exceeding 37°C during CPB is an independent predictor of acute kidney injury.

Recommendation:

Surgical teams should limit arterial outlet blood temperature to less than 37°C to avoid cerebral hyperthermia. (Class I, Level C)

Peak Cooling Temperature Gradient and Cooling Rate

In 1997, Geissler et al. (30) demonstrated that temperature gradients (differential temperature between arterial outlet and venous inflow blood temperature) on cooling of more than 10°C were associated with gas emboli formation. They also reported no gaseous microemboli production when rapid cooling was used; however, this finding has not been reproduced. No contemporary literature has addressed this issue; however, a unique study in dogs in 1964 by Almond et al. (31) documented severe brain injury when an arterial-venous gradient of 20°C was used for cooling and significantly less injury when the cooling gradient was limited to 4° C. The authors proposed that rapid, high gradient cooling might not provide adequate cerebral hypothermia, preventing cerebral protection during induced cardiac arrest (the usual approach to cardiac operations in that era).

Recommendation:

Temperature gradients between the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB cooling should not exceed 10°C to avoid generation of gaseous emboli. (Class I, Level C)

Peak Warming Temperature Gradient and Rewarming Rate

The rate of rewarming during CPB and the temperature gradient to achieve this rewarming goal produces a conundrum for clinicians: the team must balance the deleterious effects of an extended duration of CPB and operative times with those that may be associated with rapid rewarming rates. A seminal issue has related to the potential for outgassing when warm blood is returned to the hypothermic patient, because dissolved gases come out of the blood when rapid rewarming takes place. Outgassing may be prevented by maintaining a maximal 10°C gradient between the arterial blood outlet and the venous inlet blood temperature (32). A number of studies have evaluated rewarming and temperature gradients, with a recommended gradient of not more than 10°C being most commonly reported (Table 2). Five clinical studies reported the influence of the rewarming rate (Table 3). Grigore et al. (45), in a cohort study evaluating cognitive performance of patients post-CPB, demonstrated a benefit associated with “slow” rewarming compared with “rapid” rewarming in the post-CPB cognitive performance of patients. In this study, slow rewarming (.49°C ± .17°C/min) was achieved with a maximal gradient of 2°C between the NP temperature and the CPB arterial blood outlet temperature, whereas rapid rewarming (.56°C ± .22°C/min) was achieved with a 4° Cto6°C maximal gradient. The slow rewarming group also avoided some of the exposure to excess hyperthermia and had temperatures in excess of 37°C for shorter periods. In this study, the gradient driving rewarming was between the NP temperature and the arterial blood outlet temperature. Borger and Rao (43) reported an observational study in which patients were evaluated for neurocognitive outcomes based on post hoc rewarming rates. The authors reported a decreased risk of neurocognitive decline with slow rewarming within one postoperative week, although this advantage was not present at 3 months.

Table 2.

Rewarming rates and temperature gradients.*

| First author | Study design | Number | Rewarming rate (° C/min) | Temperature gradient (° C) | Gradient between | Max arterial outlet | Monitoring site driving temperature management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croughwell (25) | Prospective observational | 133 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NP |

| Cook (23) | Prospective observational | 10 | .56°C/min observational (estimated))† | 10°C | H/E to blood | NR | NP, venous return |

| Geissler (30) | Animal | 8 | NR | 0°C, 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C | Venous and arterial blood | NR | Thermodilution catheter placed in superior vena cava, arterial blood outlet (oxygenator) |

| Ginsberg (33) | Prospective, randomized | 101 | 1°C every 3–5 minutes, achieved .2°C± .09°C, .19°C ± .07°C, .18°C ± .07°C | <10°C | H/E to venous | NR | PA catheter thermistor |

| Nathan (34) | Prospective, randomized | 223 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NP |

| Johnson (11) | Prospective, randomized | 80 | NR | NR | NR | 38°C | NP |

| Schmid (35) | 5°C | H/E to venous | |||||

| Lindholm (36) | Prospective, randomized | 30 | NR | 10°C | H/E to venous | 37–39°C | NP cooling, bladder rewarming |

| Ali (37) | Prospective, randomized | 60 | .33°C/min | NR | NR | NR | NR (“CPB temperature” perhaps arterial blood outlet) |

| Kaukuntla (12) | Prospective, randomized | 60 | NR | 10°C | H/E to arterial inlet? | 37.5°C | NP (hypothermic), bladder (normothermic) |

| Nussmeier (8) | Review | NA | .2° C/min | NR | NR | NR | NP, arterial line temperature? |

| Nussmeier (6) | Prospective observational | 12/30 | NR | NR | NR | 37°C | JB, NP, esophageus, bladder, rectum, arterial blood outlet |

| Boodhwani (38) | Prospective, randomized | 267 | N/A | NR | NR | 37.5°C/34.5°C | NP |

| Rasmussen (39) | Prospective, randomized | 30 | NR | 10°C | H/E to venous | NR | NR |

| Hong (40) | Prospective observational | 103 | 1°C every 5 minutes | NR | NR | 37°C | NR |

| Akata (7) | Prospective observational | 20 | NR | Varying, as high as 20–25°C | JB to H/E | 37.5°C | JB cooling, bladder rewarming |

| Boodhwani (41) | Prospective, randomized | 223/267 | NR | NR | NR | 37.5°C/34.5°C | NP |

| Sahu(42) | Prospective, randomized | 80 | NR | 2–4°C | H/E to blood | NR | NP |

| Newland (29) | Prospective observational | 1393 | <l°C/min | NR | NR | 37.5°C/37°C | NP |

A description of reported trials (patient and animal) on rates of rewarming and arterial-venous temperature gradients (1992–2013).

Calculated, not stated in original publication. H/E, heat exchanger; NR, not reported.

Table 3.

Slow vs. fast rewarming: rates, gradients, and outcomes.a

| Slow Rewarming |

Fast Rewarming |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Study design | No. | Rate/duration | Gradient | Rate/duration | Gradient | Gradient between | Max arterial outlet | Monitoring site driving temperature management | Outcome measure |

| Cook 199623 | Prospective obsevational | 10 | .45°C/min (estimated)b | NR | .71°C/min (estimated)b | NR | H/E to blood | NR | NP | Cerebral venous oxygen desaturation less in slow group |

| Borger 200243 | Prospective observational | 146 | 30 ± 9 min | NR | 15 ± 4 min | NR | NR | NP | Neurocognitive function, benefit with slower rewarming rate | |

| Diephuis 200244 | RCT | 50 | .24°C ± .08°C/min | 5 | .5°C ± .36° C/min | 10 | NP to H/E | NP | Cerebral pressure flow index unaffected by rewarming rate | |

| Grigore 200245 | Prospective cohort blinded | 165 | .49°C ± .17°C/min | 2 | .56°C ± .22°C/min | 4–6 | NP and arterial outlet | NR | NP | Neurocognitive function, benefit with slower rewarming rate |

| Kawahara 200346 | RCT | 100 | .24°C/min | 1–2 | .48°C/min | 4–5 | Tympanic and arterial outlet | NR | Tympanic, PA | Jugular venous oxygen hemoglobin saturation, less decrease with slower rewarming rate |

| Saleh 200547 | RCT | 30 | .196°C ± .016°C/min | 3 | .34°C ± .027°C/min | 7 | NP to H/E | NP | Cardiac performance (cardiac index and peak velocity), blood lactate level, early homeostasis, ICU stays, improved with slower rewarming (medium rate, .248°C± .023°C) | |

Abbreviations: H/E = heat exchanger; ICU = Intensive care unit; NP = nasopharyngeal; NR = not reported; PA = pulmonary artery; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

A description of reported trials (patients only) specific to slow vs. fast rewarming rates, arterial-venous gradients, and outcomes (1996–2005).

Calculated, not stated in original publication.

Kawahara et al. (46), in a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 100 patients, demonstrated a reduction in the decrease in JB venous oxygen saturation with slow rewarming compared to rapid rewarming; however, they were unable to demonstrate any biochemical or neurologic benefits. They used similar temperature gradients as Grigore et al. (45), with a 1°C to 2°C difference between tympanic membrane and perfusate temperatures in the slow group (.24°C ± .09°C/min) and a 4°C to 5°C difference in the fast group (.48°C ± .09°C/min).

Sahu et al. (42), in a RCT in which the rewarming rate was tightly managed with a gradient of 2°C to 4°C, found similar reductions in JB venous oxygen saturation whether patients were rewarmed to 37°C or to 33° C. However, the authors reported less neurocognitive decline in patients rewarmed to only 33° C. The findings from this study suggest that exposure to cerebral hyperthermia may be associated with rapid rewarming and increased neurocognitive decline.

Diephuis et al. (44) evaluated the influence of fast (.5°C/min) and slow (.24°C/min) rewarming rates on cerebral blood flow, measured by transcranial Doppler, finding no significant effect of rewarming on the relation between pressure and cerebral blood flow. The authors used a maximal gradient of 10°C between the NP and water temperature in the fast group and a gradient of 5°C in the slow rewarming group.

In addition, an advantage associated with slow rewarming was supported by studies conducted in a pediatric population and in a swine model. Saleh and Barr (47) studied the effect of three rewarming strategies in pediatric patients and found that the slowest rewarming rate was associated with improved indices of cardiac function (improved cardiac index and decreased lactate production) but was disadvantaged by longer bypass times and time to reach core temperature targets. Alam et al. (48), in a swine model of lethal hemorrhage, investigated three rewarming rates from profound hypothermic arrest, slow (.25°C/min), medium (.5°C/min), and fast (1°C/min), and found a significant survival advantage in the group that was rewarmed at the medium rate compared with the fast rate. The group undergoing the slow rewarming rate had rewarming durations that were 1.7 and 2.1 times as long as those of the medium and fast groups, respectively, which may account for the worse outcomes in the slow group compared with those in the medium group.

The Ottawa Heart Institute published a series of reports discussing neurocognitive findings in two randomized coronary artery bypass grafting trials, each with more than 200 patients. In the first study, patients were randomized to rapid rewarming either to 37°C or to 34° C. The authors reported a significant early cognitive benefit noted in the relatively hypothermic patients (34,49). In this study arterial outlet temperatures were not reported nor were the absolute rewarming rates, potentially exposing the normothermic group to cerebral hyperthermia. Patients in the second randomized study were maintained at 37°C throughout the operation or maintained at 34°C without rewarming, thereby avoiding the rewarming process entirely. The authors found no differences in neurocognitive function between the two management strategies (38). They concluded that in the absence of active rewarming, cerebral hyperthermia was avoided. Although the conclusion of the two trials warrants the recommendation to avoid “rapid” rewarming to 37° C, the actual rate of rewarming in this “rapid” group was not reported. The data also suggest that normothermia itself is not associated with neurocognitive decline, but rather, that rapid rewarming to normothermia may lead to inadvertent cerebral hyperthermia.

Boodhwani et al. (41) later reported the influence of rewarming on renal function and concluded that the process of rewarming from 34°C to 37°C on CPB is associated with increased renal injury. This finding was supported by Newland et al. (29), who reported an arterial outlet temperature higher than 37°C is an independent predictor of acute kidney injury.

Multiple authors, including Kaukuntla et al. (50), suggest slow rewarming to avoid heterogeneous changes in brain temperature, and similarly, Murphy et al. (22) support gradual rewarming compared with rapid rewarming. Scheffer and Sanders (10) promote slow rewarming for a number of reasons including 1) avoidance of excess cerebral oxygen extraction and jugular venous desaturation; 2) improved maintenance of the relationship between cerebral blood flow and the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen; and 3) increased time for better distribution of heat.

In a review paper comparing hypothermic with normothermic CPB, Grigore et al. (20) highlight the difficulty in assessing temperature management strategies as distinct from the confounder of rewarming rate. Only 4 of 15 RCTs reported information on rewarming rates. Cook (51) summarizes the case for slow rewarming most simply: its adoption increases the likelihood of preventing hyperthermia.

Recommendation:

Temperature gradients between the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB rewarming should not exceed 10°C to avoid outgassing when warm blood is returned to the patient. (Class I, Level C)

- Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature ≥30°C:

- To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a temperature gradient between the arterial outlet and the venous inflow temperature of 4°C or less. (Class IIa, Level B)

- To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a rewarming rate of .5°C/min or less. (Class IIa, Level B)

Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature is lower than 30°C: to achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a maximal gradient of 10°C between the arterial outlet and venous inflow temperature. (Class IIa, Level C)

Optimal Temperature for Weaning from CPB

There have been few compelling studies focused on the relationship between the temperature at the discontinuation of CPB and adverse sequelae. In the randomized trial by Nathan et al. (34) published in 2001, patients were rewarmed to 37°C or 34°C before CPB was discontinued. Cognitive function was assessed at three time points: early post-CPB, 3 months, and 5 years. An initial benefit was seen early post-CPB in the 34°C group (48% vs. 62% decline), but this was largely overcome by 3 months, and no statistically significant benefit was noted by 5 years (34,49,52).

Although it seems that much of the literature supports a hypothermic separation from CPB to protect cerebral metabolism, Insler et al. (53) reported outcomes in approximately 1600 coronary artery bypass patients who had core temperatures lower than 36°C on arrival in the intensive care unit (ICU). Adjusting for preoperative conditions, hypothermic patients had increased mortality, more transfusions, increased intubation time, and a longer ICU stay.

An additional consideration in hypothermia is the presence of post-CPB core temperature after drop, which is associated with reduced blood flow during CPB to muscle and viscera, and post-CPB heat transfer from the core to the periphery, resulting in core temperature depression (54). These are well-known phenomena and have associated morbidities themselves (55). Given the paucity of data and conflicting literature on weaning temperature and outcome after CPB, no specific weaning temperature is recommended. In the absence of a specific recommendation, the choice of temperature for weaning from CPB should be balanced between avoidance of cerebral hyperthermia and minimization of coagulopathy and transfusion. Post-CPB surface heating can be used in the postoperative cardiac surgical patient, but these techniques are not in the purview of this guideline.

No Recommendation: No specific recommendation for an optimal temperature for weaning from CPB may be made due to inconsistent published evidence.

SUMMARY

The importance of accurately recording and reporting temperature management during CPB cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, many published articles fail to document temperature management strategies during and after CPB.

Temperature management during CPB remains controversial, with gaps in our knowledge concerning a variety of aspects of temperature management. The Institute of Medicine has identified the need to incorporate the best clinical evidence into practice. Importantly, these guidelines challenge the cardiac surgical community to conduct research to address these gaps in knowledge. The summary of recommendations for temperature management during CPB is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Recommendations for temperature management during cardiopulmonary bypass.*

| Recommendation | Classification |

|---|---|

| Optimal site for temperature measurement | |

| The oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature is recommended to be used as a surrogate for cerebral temperature measurement during CPB | Class I, Level C |

| To accurately monitor cerebral perfusate temperature during warming, it should be assumed that the oxygenator arterial outlet blood temperature underestimates cerebral perfusate temperature | Class I, Level C |

| PA catheter or NP temperature recording is reasonable for weaning and immediate postbypass temperature measurement | Class IIa, Level C |

| Avoidance of hyperthermia | |

| Surgical teams should limit arterial outlet blood temperature to <37°C to avoid cerebral hyperthermia | Class I, Level C |

| Peak cooling temperature gradient and cooling rate | |

| Temperature gradients from the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB cooling should not exceed 10°C to avoid generation of gaseous emboli | Class 1, Level C |

| Peak warming temperature gradient and rewarming rate | |

| Temperature gradients from the arterial outlet and venous inflow on the oxygenator during CPB rewarming should not exceed 10°C to avoid outgassing when warm blood is returned to the patient | Class I, Level C |

| Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature >30° C | |

| To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a temperature gradient between arterial outlet temperature and the venous inflow of ≤4° C | Class IIa, Level B |

| To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a rewarming rate of ≤.5°C/min | Class IIa, Level B |

| Rewarming when arterial blood outlet temperature is <30° C | |

| To achieve the desired temperature for separation from bypass, it is reasonable to maintain a maximal gradient of 10°C between arterial outlet temperature and venous inflow | Class IIa, Level C |

The summary of the recommendations for temperature management during CPB.

APPENDIX

Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms used to identify peer-reviewed articles related to temperature management in the setting of adult cardiopulmonary bypass:

(“cardiopulmonary bypass” [MeSH Terms] or perfusion [TIAB]) and (“body temperature” [MeSH Terms] or “body temperature regulation”[MeSH Terms] or “rewarming” [MeSH Terms]) and (“humans” [MeSH Terms] and English [lang] and “adult” [MeSH Terms])

((“cardiopulmonary bypass” [MeSH Terms] or cardiopulmonary bypass [TIAB]) and (“hypothermia, induced/instrumentation” [MAJR:noexp] or “hypothermia, induced/methods” [MAJR:noexp] or “body temperature” [MeSH Terms] or “body temperature regulation” [MeSH Terms] or “rewarming”[MeSH Terms]) and (“humans”[MeSH Terms] and English [lang])) not ((“cardiopulmonary bypass”[MeSH Terms] or perfusion [TIAB]) and (“body temperature” [MeSH Terms] or “body temperature regulation” [MeSH Terms] or “rewarming” [MeSH Terms]) and (“humans” [MeSH Terms] and English [lang] and “adult” [MeSH Terms])).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartels C, Gerdes A, Babin-Ebell J, et al. . Cardiopulmonary bypass: Evidence or experience based? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:20–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shann KG, Likosky DS, Murkin JM, et al. . An evidence-based review of the practice of cardiopulmonary bypass in adults: A focus on neurologic injury, glycemic control, hemodilution, and the inflammatory response. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belway D, Tee R, Nathan HJ, et al. . Temperature management and monitoring practices during adult cardiac surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass: Results of a Canadian national survey. Perfusion. 2011;26:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association. Methodology Manual and Policies from the ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Available at: http://assets.cardiosource.com/Methodology_Manual_for_ACC_AHA_Writing_Committees.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowder CM, Tempelhoff R, Theard MA, Cheng MA, Todorov A, Dacey RG Jr.. Jugular bulb temperature: Comparison with brain surface and core temperatures in neurosurgical patients during mild hypothermia. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussmeier NA, Cheng W, Marino M, et al. . Temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass: The discrepancies between monitored sites. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akata T, Setoguchi H, Shirozu K, Yoshino J.. Reliability of temperatures measured at standard monitoring sites as an index of brain temperature during deep hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass conducted for thoracic aortic reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nussmeier NA.. Management of temperature during and after cardiac surgery. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:472–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook DJ.. Cerebral hyperthermia and cardiac surgery: Consequences and prevention. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;13:176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheffer T, Sanders B.. The neurologic sequelae of cardiopulmonary bypass-induced cerebral hyperthermia and cerebroprotective strategies. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2003;35:317–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RI, Fox MA, Grayson A, Jackson M, Fabri BM.. Should we rely on nasopharyngeal temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass? Perfusion. 2002;17:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaukuntla H, Harrington D, Bilkoo I, Clutton-Brock T, Jones T, Bonser RS.. Temperature monitoring during cardiopulmonary bypass—do we undercool or overheat the brain? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:580–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newland RF, Sanderson AJ, Baker RA.. Accuracy of temperature measurement in the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:32–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newland RF, Baker RA, Sanderson AJ, Tuble SC, Tully PJ.. Oxygenator safety evaluation: A focus on connection grip strength and arterial temperature measurement accuracy. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2012;44:53–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salah M, Sutton R, Tsarovsky G, Djuric M.. Temperature inaccuracies during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;373:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potger KC, McMillan D.. In vitro validation of the affinity NT oxygenator arterial outlet temperatures. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:207–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallis WM.. Monitoring bladder temperatures in the OR. AORN J. 2002;76:467–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxton FJ, Justin L, Gillies D.. Estimating core temperature in infants and children after cardiac surgery: A comparison of six methods. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan TA, Vohra HA, Paul S, Rosin MD, Patel RL.. Axillary and tympanic membrane temperature measurements are unreliable early after cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:551–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grigore AM, Murray CF, Ramakrishna H, Djaiani G.. A core review of temperature regimens and neuroprotection during cardiopulmonary bypass: Does rewarming rate matter? Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grocott HP.. PRO: Temperature regimens and neuroprotection during cardiopulmonary bypass: Does rewarming rate matter? Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1738–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy GS, Hessell EA, Groom RC.. Optimal perfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass: An evidence-based approach. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1394–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook DJ, Orszulak TA, Daly RC, Buda DA.. Cerebral hyperthermia during cardiopulmonary bypass in adults. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:268–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima T, Kuro M, Hayashi Y, Kitaguchi K, Uchida O, Takaki O.. Clinical evaluation of cerebral oxygen balance during cardiopulmonary bypass: On-line continuous monitoring of jugular venous oxyhemoglobin saturation. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croughwell ND, Frasco P, Blumenthal JA, Leone BJ, White WD, Reves JG.. Warming during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with jugular bulb desaturation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:827–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos JM, Paniagua P.. Hypothermia during cardiac surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22:695–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grocott HP, Mackensen GB, Grigore AM, et al. . Neurologic Outcome Research Group (NORG) Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Research Endeavors (CARE) Investigators’ of the Duke Heart Center. Postoperative hyperthermia is associated with cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Stroke. 2002;33:537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groom RC, Rassias AJ, Cormack JE, et al., Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Highest core temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass and rate of mediastinitis. Perfusion. 2004;19:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newland RF, Tully PJ, Baker RA.. Hyperthermic perfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative temperature are independent predictors of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2013;28:223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geissler HJ, Allen SJ, Mehlhorn U, et al. . Cooling gradients and formation of gaseous microemboli with cardiopulmonary bypass: An echocardiographic study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almond CH, Jones JC, Snyder HM, Grant SM, Myer BW.. Cooling gradients and brain damage with deep hypothermia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1964;48:890–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butler BD, Kurusz M. . Gaseous microemboli: A review. Perfusion. 1990;5:81–99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginsberg S, Solina A, Papp D, et al. . A prospective comparison of three heat preservation methods for patients undergoing hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nathan HJ, Wells GA, Munson JL, Wozny D.. Neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: A randomized trial. Circulation. 2001;104:I85–I91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid FX, Pjillip A, Foltan M, Juestock H, Wiesenack C, Birnbaum D.. Adequacy of perfusion during hypothermia: Regional distribution of cardiopulmonary bypass flow, mixed venous and regional venous oxygen saturation—hypothermia and distribution of flow and oxygen. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51:306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindholm L, Bengtsson A, Hansdottir V, Lundqvist M, Rosengren L, Jeppsson A.. Regional oxygenation and systemic inflammatory response during cardiopulmonary bypass: Influence of temperature and blood flow variations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali MS, Harmer M, Vaughan RS, et al. . Changes in cerebral oxygenation during cold (28_C) and warm (34_C) cardiopulmonary bypass using different blood gas strategies (alpha-stat and pH-stat) in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boodhwani M, Rubens FD, Wozny D, et al. . Effects of sustained mild hypothermia on neurocognitive function after coronary artery bypass surgery: A randomized, double-blind study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen BS, Sollid J, Knudsen L, et al. . The release of systemic inflammatory mediators is independent of cardiopulmonary bypass temperature. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21:191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong SW, Shim JK, Choi YS, et al. . Prediction of cognitive dysfunction and patients’ outcome following valvular heart surgery and the role of cerebral oximetry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:560–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boodhwani M, Rubens FD, Wozney D, Nathan HJ.. Effects of mild hypothermia and rewarming on renal function after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahu B, Chauhan S, Kiran U, et al. . Neurocognitive function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: The effect of two different rewarming strategies. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borger MA, Rao V.. Temperature management during cardiopulmonary bypass: Effect of rewarming rate on cognitive dysfunction. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;6:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diephuis JC, Balt J, van Dijk D, Moons KG, Knape JT.. Effect of rewarming speed during hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass on cerebral pressure-low relation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grigore AM, Grocott HP, Mathew JP, et al. . The rewarming rate and increased peak temperature alter neurocognitive outcome after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawahara F, Kadoi Y, Saitp S, Goto F, Fujita N.. Slow rewarming improves jugular venous oxygen saturation during rewarming. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saleh M, Barr TM.. The impact of slow rewarming on inotropy, tissue metabolism, and “after drop” of body temperature in pediatric patients. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:173–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alam HB, Rhee P, Honma K, et al. . Does the rate of rewarming from profound hypothermic arrest influence the outcome in a swine model of lethal hemorrhage? J Trauma. 2006;60:134–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubens FD, Nathan H.. Lessons learned on the path to a healthier brain: Dispelling the myths and challenging the hypotheses. Perfusion. 2007;22:153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaukuntla H, Walker A, Harrington D, Jones T, Bonser RS.. Differential brain and body temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass—a randomised clinical study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cook DJ.. CON: Temperature regimens and neuroprotection during cardiopulmonary bypass: Does rewarming rate matter? Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1733–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nathan HJ, Rodriguez R, Wozny D, et al. . Neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: Five year follow-up of a randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1206–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Insler SR, O’Connor MS, Leventhal MJ, Nelson DR, Starr NJ.. Association between postoperative hypothermia and adverse outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajek A, Lenhardt R, Sessler DI, et al. . Tissue heat content and distribution during and after cardiopulmonary bypass at 31 degrees C and 27 degrees C. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tindall MJ, Peletier MA, Severens NM, Veldman DJ, de Mol BA.. Understanding post-operative temperature drop in cardiac surgery: A mathematical model. Math Med Biol. 2008;25:323–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]