Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis is a highly prevalent disease in the Western hemisphere. It is considered one of the most virulent primary fungal infections. Coccidioides species live in arid and semi-arid regions, causing mainly pulmonary infection through inhalation of arthroconidia although many other organs can be affected. Primary inoculation is rare. Since the first case of coccidioidomycosis was reported in 1892, the skin has been identified as an important target of this disease. Knowledge of cutaneous clinical forms of this infection is important and very useful for establishing prompt diagnosis and treatment. The purpose of this article is to provide a review of this infection, emphasizing its cutaneous manifestations, diagnostic methods and current treatment.

Keywords: Coccidioides, Coccidioidomycosis, Mycoses

INTRODUCTION

Coccidioidomycosis, also known as "San Joaquin Valley Fever" or "Desert Rheumatism", is the oldest of the major systemic mycoses, considered to be one of the most infectious fungal diseases.1,2 Two different species have been recognized as causative agents: Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii. The former appears to be limited to Southern California and Northern Mexico, while the latter occurs in all other endemic areas.1 It is almost exclusively prevalent in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in semiarid to arid life zones of Southwestern United States, north of Mexico, and some places in Central and South America.3 This fungal infection can cause a broad clinical spectrum: it can be asymptomatic, or it can range from a mild febrile illness to severe pulmonary manifestations or disseminated disease.4 In symptomatic patients, the most common manifestation is pulmonary disease, but many other organs can be affected. Cutaneous involvement of coccidioidomycosis entails a great significance because of its wide heterogeneity of clinical manifestations that can confuse the clinician.

HISTORICAL VIGNETTE

Coccidioidomycosis was first described in 1892 by Alejandro Posadas (a medical student from Argentina), when he evaluated Domingo Ezcurra, a soldier who presented with a verrucous papule on the right cheek. A diagnosis of mycosis fungoides with psorospermia was considered. After having observed spherical organisms with a double-refractile outer wall, that appeared similar to the protozoan Coccidia, Posadas and his mentor, Robert Wernicke, believed that these organisms had a parasitic origin. Ezcurra died in 1898 despite many topical treatments. His head is now conserved in a museum in Buenos Aires.5,6

Some years later, Rixford and Gilchrist, both pathologists, analyzed the biopsies of two similar cases in California, involving emigrants from the Azores, a group of islands belonging to Portugal, finding the same structures previously described by Posadas.5-7 In 1896, the organism was given the names Coccidioides ("resembling Coccidia") and immitis (meaning "not mild", since it was perceived as a lethal disease).4 In 1900, Ophüls and Moffitt defined the fungal etiology of this microorganism and established its dimorphism. In 1914, Cooks used the coccidioidin test for the first time and described the precipitin reaction.8

In 1929, the fatal outcome in patients with this disease was questioned after the report of Harold Chope's infection. This medical student, while working at Stanford University, accidentally inhaled C. immitis spores and developed severe pneumonia, but, surprisingly, he survived and recovered completely.4,9

In Mexico, the first case was presented in 1932 by Cicero and Perrin; and later, in 1945, González-Ochoa described the Northern states of the country as endemic zones, by epidemiological testing with coccidioidin cutaneous reactions.8

When the first cases were reported, coccidioidomycosis was considered a disfiguring, fatal illness, but nowadays it is known that most cases follow a benign course, and only around 5% of cases become symptomatic and chronic.5

ETIOLOGY

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by the dimorphic, soil-borne ascomycete fungi. It has two known genetic species: C. immitis and C. posadasii. The former seems to be restricted to California, Arizona, and Baja California (Mexico), while the latter is found in the remaining endemic regions. Both species differ genetically, but they are clinically and microbiologically indistinguishable.10

GEOGRAPHY AND ECOLOGY

Coccidioidomycosis is endemic in the Western hemisphere, particularly between the 40º latitudes north and south. There are two predominant regions, located in the Southwestern United States and the north of Mexico (Baja California, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas, all of them corresponding to the Sonoran Desert zone).10,11 Other areas have been described in central states of Mexico, as well as in Central and South America.11

Coccidioides spp. are found in alkaline, sandy soils from semi-desert regions with hot summers, gentle winters, and annual rainfall between 10 and 50 cm. These fungi are usually found 10 to 30 cm beneath the surface.4,12

Different types of cactus and bushes like Larrea tridentata ("creosote bush") have been identified as common vegetation in the type of soil where this fungus lives.5

EPIDEMIOLOGY

It is estimated that 150,000 new infections occur annually in areas of the Southwestern United States. Coccidioidomycosis is not a nationally reportable disease (it is only reported in the states of California and Arizona), therefore, the exact national incidence is unknown.1

The incidence of Coccidioides spp. infection has increased in recent years. In a recent summary by the California Department of Health, it rose from 4.3 to 11.6 per 100,000 population from 2001 to 2010.3,13 In Arizona, it rose from 12 to 58.2 per 100,000 population over the same time period.3,14 Overall, it is estimated that 70% of all Coccidioidomycosis cases in USA occur in Arizona, and 25% in California.15

In Latin America there are no reliable statistics. In Mexico, Coccidioidomycosis is not a reportable disease and its true incidence is unknown, though most clinical case reports originate in the northern region of the country. Regional skin test surveys with coccidioidin in Mexico have shown positive skin reactions between 10% (in Tijuana and Baja California, 1991) and 93% (in Coahuila, 2005).11,16,17 Historically, Argentina is of great interest, since it was the place where the first case of Coccidioidomycosis was reported in 1892. Even though the magnitude of infection in this country is unknown, a prevalence from 14.8 to 16% has been estimated according to some coccidioidin surveys.1,18,19

The exponential rise in Coccidioidomycosis, particularly in endemic places, has been attributed to many factors, including a growing population, migration of susceptible people to endemic areas, an increase in individuals of advanced age or with immunosuppression, soil disturbances caused by construction and businesses, and climate changes.10,14,20

RISK FACTORS FOR INFECTION

The most important risk factor is dust exposure in endemic areas, usually due to occupational and recreational activities.1 Populations at greater risk for infection are those with intense exposure to aerosolized arthroconidia, including agricultural or construction workers, or people who participate in outdoor activities such as hunting or digging in the soil.4,21,22 Oubreaks of coccidioidomycosis have been described in military personnel training in endemic areas, armadillo hunting expeditions, construction work, and model airplane competitions.23-25 Other risk factors include natural disasters such as earthquakes and windstorms.4,26

Coccidioidomycosis affects all age groups, though higher incidence rates have been documented among adults, ranging from 40-49 years in California, to >65 years in Arizona.14,27 It has a predilection for men over women (with an estimated incidence of 54% versus 46% of cases in Arizona, respectively).28 Gender disparities are thought to be mostly related to occupational factors (since men tend to participate more in high risk, outdoor activities); however, males also have greater risk for dissemination, suggesting a hormonal or genetic component.1,29

Certain groups are considered more vulnerable to coccidioidal infection. Racial predilection for Filipino or African American patients has been reported.30,31 These groups have higher rates for infection and dissemination of disease, ranging from 10 to 175 times higher than other ethnicities.32 Pregnant women are also considered a high risk group for severe or disseminated disease, especially during later stages of pregnancy (usually during the third trimester), presumably associated with immunologic and hormonal factors.33,34 Immunosuppressed patients, predominantly those with alteration of T cell function, are at higher risk of infection and dissemination of disease. This group includes patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hematologic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), inflammatory arthritis, and diabetes.32,35-37 Organ transplantation and subsequent use of immunosuppressive agents have also been described as important risk factors for the disease.1

MICROBIOLOGY, LIFE CYCLE AND IMMUNOLOGY

Coccidioides species exist in two phases: the mycelial phase, and the spherule phase. (12)They are found as mycelia in the soil, made of septate and ramified hyphae, which proliferate rapidly after a rainy period. Then, as the environment dries, mycelia reproduce asexually, breaking the hyphae and releasing small, thick-walled spores named arthroconidia. These spores can spread from the soil by wind, natural disasters, and human activities. Infection occurs with the inhalation of arthroconidia, which later reach the human bronchioles and alveoli. There, they can enlarge and form spherules, which develop internal endospores. The endospores are released and spread to nearby or distant tissues and can develop again into spherules, continuing their life cycle.10,38-40

Immunological aspects are complex and involve the participation of many cell types. The acute immunologic response to infection consists mainly of an early influx of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, monocytes and natural killer cells; eosinophilia may also be present during this phase. During a later stage, a granulomatous reaction may develop, with increased number of lymphocytes, plasma cells and multinucleated giant cells. Other immune mechanisms involve the presentation of coccidioidal antigens by dendritic cells, the activation of B lymphocytes and CD4+ T lymphocytes, and the development of a delayed-type hypersensitivity and cellular immunity.10,40,41 Once developed, cellular immunity appears to be protective and long lived.41

CLASSIFICATION AND CLINICAL PICTURE

Coccidioidomycosis may cause a heterogeneous clinical spectrum and be classified into primary and secondary disease. Primary disease generally affects the lungs, which is by far the most common site involved. In this case, it is acquired by direct inhalation of arthroconidia. Primary involvement of the skin is quite uncommon. It is acquired by direct inoculation of the fungus by means of splinters and abrasions. Secondary disease can affect the lungs and become a chronic process. On the other hand, disseminated disease (usually resulting from hematogenous spread of a primary lung infection) can involve many organs, among them: the skin, bones, joints, nervous system and meninges.8

PULMONARY COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is the most common infection. Up to 60% of the affected individuals are usually asymptomatic, and the remaining 40% can present with pulmonary and systemic manifestations that usually appear one to three weeks after inhalation of arthroconidia.12,42 Most symptomatic patients can develop a flu-like syndrome (fever, headache, profound fatigue, cough, pleuritic pain, and arthralgias), commonly known as "The Valley Fever of San Joaquin".42 Cough and fever appear in 75% of patients; the skin is affected in up to 50% of cases during this acute phase, most commonly in the form of a non-pruritic papular rash, erythema nodosum, and erythema multiforme.1 Radiographically, it may be similar to other forms of pneumonia, showing lobar segmental or subsegmental infiltrates. Hilar adenopathy and pleural effusions may also be observed.43

Chronic and progressive pneumonia may occur in a small percentage of cases. The patients present symptoms that last for more than 3 months (persistent cough, hemoptysis, and weight loss). Radiographically, cavitations and solitary pulmonary nodules are detected.38

DISSEMINATED COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Disseminated disease occurs in 1% to 5% of all patients affected by coccidioidomycosis, and it usually is clinically manifested within 2 years of exposure. Dissemination can affect any organ, with the skin, central nervous system and musculoskeletal system being reported as the most prevalent.12 Many different cutaneous manifestations may be seen in disseminated disease and will be reviewed in detail later on this article. Osteoarticular infection is usually monoarticular (affecting the knee) or it can affect the vertebrae. These can be difficult to treat.44 Central nervous system involvement most commonly presents as meningeal infection, which can be fatal if left untreated (95% of patients die within 2 years of diagnosis), and requires life-long therapy.45,46

Some factors that entail a higher risk for dissemination of coccidioidomycosis are Filipino and African patients, HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, use of immunosuppressive medications, older age, diabetes and late-stage pregnancy.4,31,33,37

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS AND THE SKIN

Since the first described case of coccidioidomycosis in Argentina, cutaneous involvement has been present. Among the organs most commonly affected after pulmonary infection, the skin is often involved. Due to the wide variety of clinical presentations, this disease may be included in the group of "great imitators". Knowledge and evaluation of cutaneous manifestations could be of great utility and significance for accurate and early diagnosis and treatment of this disease.47

CUTANEOUS MAN IFESTATIONS OF COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Skin manifestations can be seen in three different scenarios of coccidioidal infection: 1)they can be a part of the acute pulmonary infection and present as an "acute pulmonary exanthema"; 2)they can reflect the presence of a disseminated infection (secondary cutaneous infection); or, in rare occasions, 3)they can represent a primary infection due to direct inoculation (primary cutaneous infection). Despite their variability and heterogeneity, cutaneous manifestations of C. immitis differ between these three forms of disease.8

Cutaneous manifestations can be further categorized as reactive and organism-specific.48 Reactive manifestations do not contain visible microorganisms, and occur during acute primary pulmonary infection in up to 50% of patients.49 They include erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, acute generalized exanthema, reactive interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and Sweet's syndrome.47 Organism-specific manifestations present with lesions that contain the organism, which can be identified in cultures or histopathology; they result from hematogenous spread of a primary pulmonary infection (secondary cutaneous disease) or, very rarely, as a result of direct trauma to the skin (primary cutaneous disease).49

REACTIVE CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS

ERYTHEMA NODOSUM

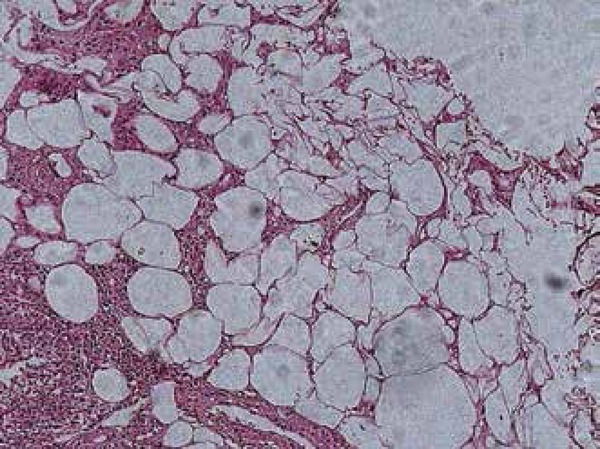

Erythema nodosum is considered the most frequent reactive cutaneous manifestation, appearing one to three weeks after the initial respiratory symptoms.50,51 It is a self-limited, inflammatory disorder of the skin and subcutaneous tissues characterized by multiple erythematous, painful nodules usually limited to the extremities (Figure 1).52 Gender and ethnicity play an important role in the onset of erythema nodosum; it is more commonly seen in white females, and it is rare in African American men.53 In some endemic sites, in the presence of erythema nodosum, Coccidioides must be ruled out.50,54 It represents a delayed hypersensitivity reaction (cell-mediated immunity) which may confer protection against the organism.55 It is associated with a favorable prognosis (with less dissemination and chronicity rates). Histologically, septal fibrosis, thickened vessels with mononuclear cells in fat lobules and focal granulomatous inflammation with occasional multinucleated giant cells may be seen, and no pathogens are found within the specimen (Figure 2).56

Figure 1.

Erythema nodosum, considered the most frequent reactive manifestation and commonly involving the lower extremities

Figure 2.

Histopathologic image of erythema nodosum in a patient with coccidioidomycosis. No organisms were found within the specimen

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Erythema multiforme is another cutaneous manifestation that has been reported since a long time ago in association with coccidioidomycosis. It is characterized by target-like lesions that typically occur within the first 48 hours of the initial symptoms and apparently reflect a hypersensitivity response to the infection (Figure 3).49 Oral involvement, pruritus and palmar desquamation have also been described as part of this manifestation.57 It is unclear whether true erythema multiforme occurs in coccidioidomycosis or if it actually represents part of an acute exanthema or Sweet's syndrome, although EM-like lesions must be taken into consideration when evaluating a case suggesting coccidioidomycosis.47

Figure 3.

Erythema multiforme: another common cutaneous manifestation of coccidioidomycosis, characterized by target-like lesions

ACUTE EXANTHEMA

A generalized exanthema or "toxic erythema" can occur in approximately 10 to 12% of patients with symptomatic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis and it has been reported in up to 50% to 60% of patients during outbreaks. It usually appears during the first days of symptoms as papular, macular, urticarial, target-like or morbiliform lesions which may be pruritic and last for several weeks.57 Clinically, it may be mistaken for allergic contact dermatitis or erythema multiforme, and histopathological findings show a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with perivascular distribution that can also mislead the diagnosis.5,57,58 The exanthema usually resolves before medical evaluation, though it may persist for several weeks and occasionally be followed by desquamation of the palms.49,57

SWEET'S SYNDROME

Sweet's Syndrome, also called "acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis" has been reported as a very rare feature of coccidioidomycosis, with few cases reported in the literature.59,60 It is characterized by an acute eruption, consisting of painful erythematous, well-demarcated papules and plaques, in association with fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. In some cases, vesicles and pustules can be seen. The common topography involves the arms, face and neck, and the biopsy specimen shows a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis, with neutrophils and leukocytoclastic debris. Even though the mainstay of treatment for Sweet's syndrome are corticosteroids, they are not recommended in the setting of coccidioidal infection, since they could exacerbate the condition.60

INTERSTITIAL GRANULOMATOUS DERMATITIS

Granulomatous tissue reactions have been described as a reactive manifestation of a variety of systemic diseases. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been reported in 5 patients with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. This eruption resembles Sweet's syndrome or a disseminated infection, with edematous and indurated cutaneous papules, nodules, and plaques presenting at the beginning of the illness. Macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils and leukocytoclastic debris are seen in the biopsy. Resolution of the lesions occurs in a variable period of time, from days to two months.48

ORGANISM-SPECIFIC MANIFESTATIONS

SECONDARY CUTANEOUS DISEASE (DISSEMINATED COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS)

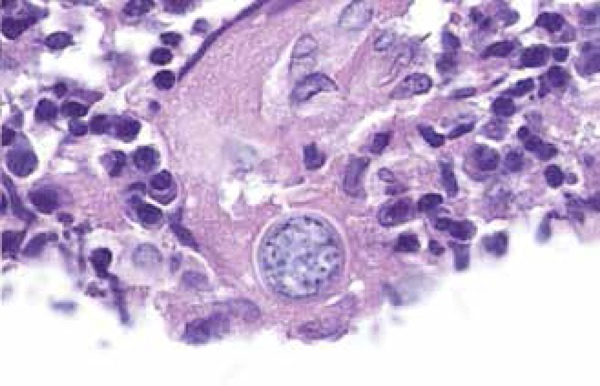

The skin has been recognized as one of the most common sites of disseminated coccidioidomycosis, and it is estimated that 15% to 67% of patients with disseminated disease have skin involvement.49 The clinical appearance of lesions is widely heterogeneous, including papules, nodules, gummas, pustular acneiform lesions, ulcerated and verrucous plaques, scars, abscesses and fistulae (Figures 4-7).5 The usual finding are the nodules.42 The topography involves the face, neck, scalp, and chest wall.5,61 The nasolabial fold is a common site of infection.62-64 Facial lesions have been associated with meningitis in some patients.65 Cutaneous lesions typically present within several weeks or months after the primary infection, or they can be the initial manifestation of the disease.53,63 They may be solitary or multiple and are usually asymptomatic.47 Important differential diagnosis include histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and primary skin malignancies.42 Histopathology findings are variable, but usually show suppurative granulomas that contain double-walled refractile spherules (10 to 80 µm) with endospores (Figure 8).62

Figure 4.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis presenting as an erythematous, crusted plaque in the upper extremity

Figure 7.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis presenting as an erythemato-squamous plaque on the upper chest

Figures 8.

Biopsy specimen showing a Coccidioides spherule

PRIMARY CUTANEOUS COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Primary cutaneous infection is extremely rare, with about 25 cases previously reported in the literature since 1926. It is usually seen in adults, although a few cases have been reported in children.66 It results from direct traumatic inoculation of the organism into the skin by an external source and typically manifests as a painless, indurated nodule with ulceration (chancroid lesion) on an extremity.5 Secondary nodules may arise in a linear lymphatic sporotrichoid distribution (Figure 9).67 In 1953, Wilson et al established diagnostic criteria for primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis, including: absence of pulmonary disease, clear evidence of traumatic inoculation, an incubation period of 1 to 3 weeks, a chancriform lesion with a painless, ulcerated nodule or plaque; an early positive precipitin reaction, an early positive coccidioidin skin test, a negative or low complement fixation reaction, the presence of lymphadenopathy and sporotrichoid nodules, and spontaneous healing after some weeks.68 Presence of granulomas containing the spherules of the fungus is observed. Prognosis of this form of coccidioidomycosis is often excellent, usually with spontaneous resolution.69

Figures 9.

Primary coccidioidomycosis presenting as lesions in a typical sporothricoid pattern

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

Culture, microscopy and serology have been the mainstay for diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis.70 Other diagnostic tools such as cutaneous tests, PCR, and imaging studies are also used.5

CULTURE AND MICROSCOPY

C. immitis and C. posadasii grow in several culture media, such as brain-heart infusion, Sabouraud-dextrose, blood and chocolate agar. Growth can be fast, from 2-7 days, or take up to 2-3 weeks. They grow at room temperature as a white, cottony mold (Figure 10).5

Figures 10.

Coccidioidomycosis culture: white, cottony mold

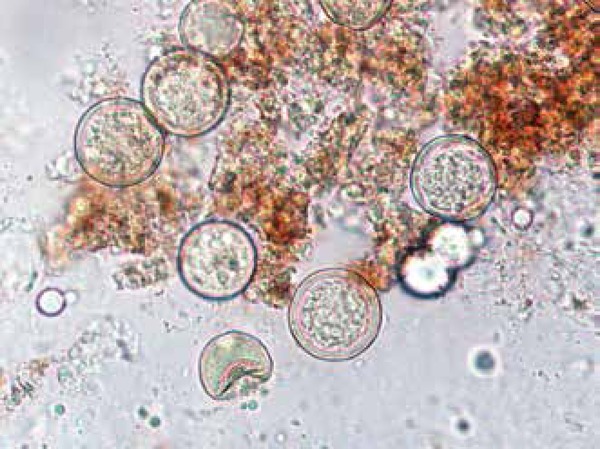

Spherules may be identified by direct mycology examination of the specimen (with potassium hydroxide and calcofluor) (Figure 11). The presence of septate hyphae, barrel-shaped arthroconidia, and double-walled refractile spherules measuring 10-80 µm with endosporulation is characteristic. Some stains like hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff and Gromori-Grocott can enhance the sensitivity for identification.5 (Figure 12)

Figures 11.

Direct microscopy study of coccidioidomycosis

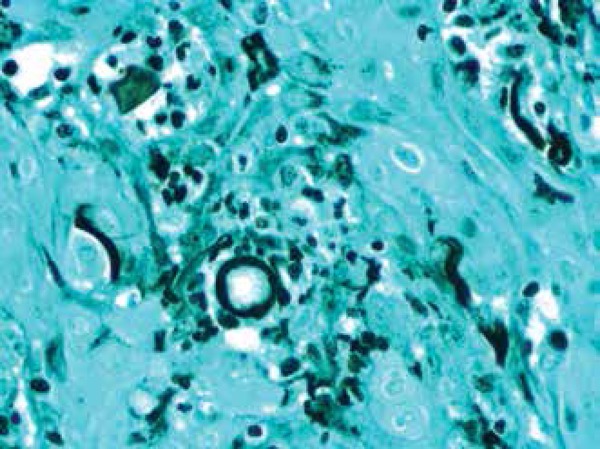

Figures 12.

Gomori-Grocott stain

SEROLOGY

Serologic tests identifying anticoccidioidal antibodies (IgM and IgG) are the most frequently employed assays for the diagnosis and prognosis of coccidioidomycosis. These tests are highly specific and relatively sensible. They include tube precipitin (TP) and complement fixation (CF) assays, as well as immunodiffusion tube precipitin (IDTP) and immunodiffusion complement fixation (IDCF), which are variants of these assays that employ immunodiffusion in agar.1

IgM antibodies appear between the first and third weeks after the initial symptoms. TP and IDTP tests are the most used methods for detecting IgM antibodies. They are positive usually between the first and third weeks of infection.1 A positive test may indicate a primary infection or reactivation. IgM antibodies tend to disappear after 4 months.69

CF and IDCF tests detect complement-fixing IgG antibodies. They appear 8-10 weeks after the initial symptoms, and last longer than tube precipitin antibodies. Titers greater than 1:32 indicate active disseminated disease. The titers usually correlate with severity; they have prognostic significance and can be used to follow progress during treatment. These antibodies tend to disappear after 6 to 8 months.69

In summary, a positive TP or IDTP test, with a negative or low CF or IDCF test, suggests primary disease. On the other hand, a negative TP or IDTP test, with a high titer of CF or IDCF suggests disseminated disease.71

OTHER METHODS

Molecular techniques such as in situ hybridization (ISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may assist in the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. They are not widely available and their sensitivity has not been determined (it may range from 80 to 98%, depending on the specimen site).70,72

Skin testing is a diagnostic method that can evaluate the overall incidence of coccidioidomycosis in endemic areas. However, its use is limited, since a positive skin test does not distinguish between current or previous infection.47

TREATMENT

Three important factors must be taken into consideration when treating coccidioidomycosis: the severity of pulmonary infection, the presence or absence of dissemination, and the patient's individual risk factors.47,73

Not every patient with coccidioidomycosis needs to be treated. In fact, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is often self-limited and some authors do not indicate treatment for immunocompetent patients without risk factors for dissemination.1 However, following the availability of triazoles, most clinicians favor treating all symptomatic patients with antifungal therapy; some of them claim that early treatment may reduce symptom duration and risk of dissemination, though there is no evidence for this assertion.3,74

For primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, immunocompetent patients without risk factors for dissemination may be treated with fluconazole or itraconazole at doses of 400 mg per day, for 3 to 6 months. Patients with severe symptoms lasting more than 6 weeks, or with risk factors for dissemination (immunosuppression, AIDS, African-American, Filipino, pregnant women and comorbidities) should also be treated. In pregnant women, the mainstay of treatment is amphotericin B (due to azoles teratogenicity). All other patients with primary coccidioidomycosis and risk factors for dissemination will be treated with azole therapy: fluconazole or itraconazole at doses of 400 mg per day for 4 to 12 months.3,73

In cases of chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, fluconazole or itraconazole at doses of 400 mg per day for 12 to 18 months or more are indicated, according to clinical response. Severe or refractory infections may be treated with amphotericin B, deoxycholate and liposomal forms.3,73 Posaconazol and voriconazol have been successful in treating some cases.11,75

Disseminated, meningeal forms of coccidioidomycosis require life-long treatment with drugs such as fluconazole 400 mg per day (with initial doses of up to 1000 mg per day) or itraconazole 400 to 600 mg per day. Intrathecal amphotericin has also been indicated.

Disseminated, non-meningeal forms of coccidioidomycosis should be treated with fluconazole or itraconazole at doses of 400 mg per day for 3 to 6 months, with the alternative of using amphotericin B in severe or rapidly progressing cases. In addition to medical treatment, surgical debridement of abscesses is indicated if needed.73

It is important to mention, however, that antifungal therapy has no role in the treatment of hyperreactive skin changes.49 In cases of primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis, treatment with itraconazole has been described, at doses of 400 mg per day for 6 months with excellent response.76

CONCLUSION

Skin involvement is one of the most common extrapulmonary manifestations of coccidioidomycosis. It involves a wide spectrum of clinical pictures. Recognizing them is very important to achieve a prompt and accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 5.

Verrucous plaques are also a common manifestation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis

Figure 6.

In this patient, disseminated coccidioidomycosis presented as an ulcerated nodule on the face

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Financial Support: None

How to cite this article: Garcia-Garcia SC, Salas-Alanis JC, Gomez-Flores M, Gonzalez-Gonzalez SE, Vera-Cabrera L, Ocampo-Candiani J. Coccidioidomycosis and the skin: a comprehensive review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):610-21.

Work performed at the Dermatology Department, Hospital Universitario Dr. José Eleuterio González, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

REFERENCES

- 1.Laniado-Laborín R, Alcandar-Schramm JM, Cazares-Adame R. Coccidioidomycosis: An Update. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2012;6:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon DM. Coccidioides immitis as a Select Agent of bioterrorism. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91:602–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S, Thompson III GR. How I Treat Coccidioidomycosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2012;7:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J, Benedict K, Park BJ, Thompson 3rd GR. Coccidioidomycosis: epidemiology. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:185–197. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S34434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Rendon A, Gonzalez G, Bonifaz A. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:573–591. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis: a review of recent advances. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rixford E, Gilchrist T. Two cases of protozoon (coccidioidal) infection of the skin and other organs. Johns Hopkins Hosp Rep. 1896;1:209–268. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arenas R. Micología médica ilustrada. 3. ed. Mexico: McGraw Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschmann JV. The early history of coccidioidomycosis: 1892-1945. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1202–1207. doi: 10.1086/513202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy MH, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2009;3:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laniado-Laborín R. Coccidioidomycosis and other endemic mycoses in Mexico. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2007;24:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(07)70051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parish JM, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:343–348. doi: 10.4065/83.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Increase in Coccidioidomycosis - California, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunenshine RH, Anderson S, Erhart L, Vossbrink A, Kelly PC, Engelthaler D, et al. Public health surveillance for coccidioidomycosis in Arizona. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:96–102. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cdc.gov.br Prevention CCfDCa. Valley Fever: Coccidioidomycosis Statistics 2012. [2014 Aug 28]. Internet. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/statistics.html.

- 16.Laniado Laborin R1, Cárdenas Moreno RP, Alvarez Cerro M. Tijuana: zona endémicade infección por Coccidioides immitis. Salud Publica Mex. 1991;33:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondragón-González R, Méndez-Tovar LJ, Bernal-Vázquez E, Hernández-Hernández F, López-Martínez R, Manzano-Gayosso P, et al. Detección de infección por Coccidioides immitis en zonas del estado de Coahuila, México. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2005;37:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negroni P, Bravo C, Negroni R. Estudios sobre el Coccidoides immitis. Encuesta epidemiológica efectuada en la Provincia de Catamarca. Bol Acad Nal Med. 1978;56:237–239. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonardello NM, de Gagliardi CG. Intradermal reactions with coccidioidins in different towns of San Luis Province. Sabouraudia. 1979 Dec;17(4):371–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hector RF, Laniado-Laborin R. Coccidioidomycosis--a fungal disease of the Americas. PLoS Med. 2005;2: doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings KC, McDowell A, Wheeler C, McNary J, Das R, Vugia DJ, et al. Point-source outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in construction workers. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:507–511. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levan NE. Occupational aspects of coccidioidomycosis. Calif Med. 1954;80:294–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das R, McNary J, Fitzsimmons K, Dobraca D, Cummings K, Mohle-Boetani J, al Occupational coccidioidomycosis in California: outbreak investigation, respirator recommendations, and surveillance findings. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:564–571. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182480556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egeberg RO, Ely AF. Coccidioides immitis in the soil of the southern San Joaquin Valley. Am J Med Sci. 1956;231:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elconin AF, Egeberg RO, Egeberg MC. Significance of soil salinity on the ecology of coccidioides immitiS. J Bacteriol. 1964 Mar;87:500–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.3.500-503.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn NM, Hoeprich PD, Kawachi MM, Lee KK, Lawrence RM, Goldstein E, et al. An unusual outbreak of windborne coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:358–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908163010705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flynn NM, Hoeprich PD, Kawachi MM, Lee KK, Lawrence RM, Goldstein E, et al. Risk factors for acute symptomatic coccidioidomycosis among elderly persons in Arizona, 1996-1997. N Engl J Med. 1979;30:358–361. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang CA, Anderson SM, Imholte SB, Erhart LM, Chen S, Park BJ, et al. Enhanced surveillance of coccidioidomycosis, Arizona, USA, 2007-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1738–1744. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drutz DJ, Huppert M, Sun SH, McGuire WL. Human sex hormones stimulate the growth and maturation of Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1981;32:897–907. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.897-907.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruddy BE, Mayer AP, Ko MG, Labonte HR, Borovansky JA, Boroff ES, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in African Americans. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:63–69. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louie L, Ng S, Hajjeh R, Johnson R, Vugia D, Werner SB, et al. Influence of host genetics on the severity of coccidioidomycosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:672–680. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenstein NE, Emery KW, Werner SB, Kao A, Johnson R, Rogers D, et al. Risk factors for severe pulmonary and disseminated coccidioidomycosis: Kern County, California, 1995-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:708–715. doi: 10.1086/319203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, Pappagianis D, Watts DH, Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:363–368. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crum NF, Ballon-Landa G. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2006;119993:e11–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, Catanzaro A, Johnson RH, Stevens DA, et al. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217–1223. doi: 10.1086/496991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blair JE, Smilack JD, Caples SM. Coccidioidomycosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:113–117. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santelli AC, Blair JE, Roust LR. Coccidioidomycosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2006;119:964–969. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003 Mar;17(1):41–57. viii–viii. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher MC, Koenig GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Molecular and phenotypic description of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov., previously recognized as the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia. 2002;94:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hung CY, Xue J, Cole GT. Virulence mechanisms of coccidioides. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:225–235. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ampel NM. The complex immunology of human coccidioidomycosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:245–258. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crum NF, Lederman ER, Stafford CM, Parrish JS, Wallace MR. Coccidioidomycosis: a descriptive survey of a reemerging disease. Clinical characteristics and current controversies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:149–175. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000126762.91040.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Batra P. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. J Thorac Imaging. 1992;7:29–38. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galgiani JN, Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, Johnson RH, Williams PL, Mirels LF, et al. Comparison of oral fluconazole and itraconazole for progressive, nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis. A randomized, double-blind trial. Mycoses Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:676–686. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-9-200011070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent T, Galgiani JN, Huppert M, Salkin D. The natural history of coccidioidal meningitis: VA-Armed Forces cooperative studies, 1955-1958. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:247–254. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewsnup DH, Galgiani JN, Graybill JR, Diaz M, Rendon A, Cloud GA, et al. Is it ever safe to stop azole therapy for Coccidioides immitis meningitis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:305–310. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-3-199602010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:929–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis associated with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:840–845. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411–421. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drutz DJ, Catanzaro A. Coccidioidomycosis. Part II. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:727–771. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith CE. Epidemiology of Acute Coccidioidomycosis with Erythema Nodosum ("San Joaquin" or "Valley Fever") Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1940;30:600–611. doi: 10.2105/ajph.30.6.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cribier B, Caille A, Heid E, Grosshans E. Erythema nodosum and associated diseases. A study of 129 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:667–672. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith CE, Beard RR. Varieties of coccidioidal infection in relation to the epidemiology and control of the diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36:1394–1402. doi: 10.2105/ajph.36.12.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arsura EL, Kilgore WB, Ratnayake SN. Erythema nodosum in pregnant patients with coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1201–1203. doi: 10.1086/514985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braverman IM. Protective effects of erythema nodosum in coccidioidomycosis. Lancet. 1999;353:168–168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen C-M, Lee H-E, Li S-Y. Coccidioidomycosis with cutaneous manifestation of erythemanodosum in Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2010;28:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiCaudo DJ, Yiannias JA, Laman SD, Warschaw KE. The exanthem of acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis: Clinical and histopathologic features of 3 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:744–746. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Werner SB. Coccidioidomycosis misdiagnosed as contact dermatitis. Calif Med. 1972;117:59–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holemans X, Levecque P, Despontin K, Maton JP. First report of coccidioidomycosis associated with Sweet syndrome. Presse Med. 2000;29:1282–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DiCaudo DJ, Ortiz KJ, Mengden SJ, Lim KK. Sweet syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) associated with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:881–884. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.7.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forbus WD, Bestebreurtje AM. Coccidioidomycosis; a study of 95 cases of the disseminated type with special reference to the pathogenesis of the disease. Mil Surg. 1946;99:653–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, DiCaudo DJ. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwartz RA, Lamberts RJ. Isolated nodular cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. The initial manifestation of disseminated disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:38–46. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hobbs ER, Hempstead RW. Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis simulating lepromatous leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:334–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb04063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arsura EL, Kilgore WB, Caldwell JW, Freeman JC, Einstein HE, Johnson RH. Association between facial cutaneous coccidioidomycosis and meningitis. West J Med. 1998;169:13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rojas-García OC, Moreno-Treviño MG, González-Salazar F, Salas-Alanis JC. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in an infant. Gac Gac Med Mex. 2014;150:175–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winn WA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. Reevaluation of its potentiality based on study of three new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:221–228. doi: 10.1001/archderm.92.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson JW, Smith CE, Plunkett OA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis; the criteria for diagnosis and a report of a case. Calif Med. 1953;79:233–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, Bergfeld WF, Taylor JS. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:944–949. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ampel NM. The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. F1000 Med Rep. 2010;2:pii: 2–pii: 2. doi: 10.3410/M2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carroll GF, Haley LD, Brown JM. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: a review of the literature and a report of a new case. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:933–936. doi: 10.1001/archderm.113.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Macêdo RC, Rosado AS, da Mota FF, Cavalcante MA, Eulálio KD, Filho AD, et al. Molecular identification of Coccidioides spp. in soil samples from Brazil. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:108–108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, Johnson RH, Stevens DA, Williams PL. Practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658–661. doi: 10.1086/313747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ampel NM, Giblin A, Mourani JP, Galgiani JN. Factors and outcomes associated with the decision to treat primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:172–178. doi: 10.1086/595687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wollina U, Hansel G, Vennewald I, Schönlebe J, Tintelnot K, Seibold M, et al. Successful treatment of relapsing disseminated coccidioidomycosis with cutaneous involvement with posaconazole. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:46–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gildardo JM, Leobardo VA, Nora MO, Jorge OC. Primary cutaneous coccidiodomycosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:121–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]