Abstract

Background

Dermatological diseases, among which acne vulgaris, have psychological impact on the affected generating feelings of guilt, shame and social isolation.

Objectives

To compare quality of life, self-esteem and other psychosocial variables amongst adolescents with and without acne vulgaris, and between levels of severity.

Methods

Cross-sectional observational study in a sample of 355 high school students from the city of João Pessoa. Data collection was performed with questionnaires and clinical-dermatological evaluation. The primary variables were the incidence of AV; quality of life, set by the Children's Dermatology Quality of Life Index and Dermatology Quality of Life Index; and self-esteem, measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. For calculation of statistical tests, we used the SPSS 20.0 software, considering p=0.05.

Results

The sample, with an average age of 16, showed 89.3% prevalence of acne vulgaris. The most prevalent psychosocial issue was "afraid that acne will never cease", present in 58% of affected youth. The median score of Quality of Life in Children's Dermatology Index was different amongst students with and without acne vulgaris (p=0.003), as well as the Quality of Life in Dermatology (p=0.038) scores, so that students with acne vulgaris have worse QoL. There was a correlation between the severity of acne vulgaris and worse quality of life. Self-esteem was not significantly associated with the occurrence or severity of acne vulgaris.

Conclusions

acne vulgaris assumes significance in view of its high prevalence and the effect on quality of life of adolescents, more severe at the more pronounced stages of disease (p<0.001). The psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris should be valued in the management of patients with this condition.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, Psychosocial impact, Quality of life, Self concept

INTRODUCTION

Appearance is important in our society and influences the way in which we are perceived by others. The skin is the most visible organ of the body and determines, to a large extent, our appearance, with a wide function in social and sexual communication.1

Skin diseases have had a negative impact on human beings, both in acceptance of their own image and in quality of life.2 According to epidemiological studies, acne vulgaris (AV) is a quite common condition, affecting approximately 80% of adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age. It is the most frequent cutaneous disorder seen by American dermatologists.3

AV is a dermatological genetic-hormonal illness, self-limited, in pilosebaceous locations, with formation of comedones, papules and cysts in which evolution to a greater inflammatory process is added, leading to formation of pustules and abscesses, with frequent cicatricial success, causing great psychological impact in patients affected by this disease.4

AV lesions predominate in exposed areas such as face and thorax, which leads to feelings of guilt, shame and social isolation. Facial appearance has an important role in self-perceptioon, as well as in the interaction with others; face lesions cause a significant impact in women's quality of life.5 According to Thomas, "In the long run acne may cause cutaneous as well as psychological scars".2

Additionally, the age bracket of greatest incidence is adolescence and young adulthood, a period of identity formation and sexual maturation, frequently marked by lack of self-confidence and changes in social dynamics.2 The presence of acneic lesions, therefore, leads to greater decrease in self-esteem and behavioral alterations, for in this age bracket patients do not have the maturity to face the psychological impact caused by AV deforming lesions.6

Considering all negative repercussions in a psychological and social context, AV has a great potential for jeopardizing quality of life (QoL). There are reports suggesting that the emotional impact from AV may be equivalent to asthma or epilepsy, diseases whose interference on QoL are already a stigma.7

This article aims to measure and compare quality of life, self-esteem and other psychosocial variables among adolescents with and without AV, as well as among adolescents with different severity levels of this dermatosis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Subjects and Study Design

This is a transversal observational study with non-probabilistic sampling. The final sample evaluated was composed of 355 students who were enrolled in high school at a public school in Joao Pessoa/PB.

Data Collection

Weekly visits to the school were made during the first school semester of 2013. Initially a pre-test was applied to a group of 46 students, allowing the evaluation of inconsistencies and looking for potential adjustments to the questionnaire being used. The research subjects were first contacted in the classroom, where after accepting to participate in the study and signing the informed consent form, they answered the questionnaire and were submitted to clinical evaluation of skin.

Variables

The first primary variables are occurrence of AV, quality of life and self-esteem. Researchers classified the sample according to presence of AV, site of involvement and degree of severity, which was categorized according to the classification of acne vulgaris proposed by Leeds and revised by Cunliffe 2003 (Table 1).8,9

Table 1.

Classification of acne vulgaris of Leeds revised by Cunliffe 2003

| Degree I | Predomiance of comedones, papules and pustules (small and < 10) | Mild |

| Degree II | 10-40 papules and pustules (comedones) | Moderate |

| Degree III | 40-100 papules and pustules, >40 comedones, presence of nodules | Moderate Severe |

| Degree IV | Nodulocystic and conglobata AV with severe, painful l esions, papules, pustules and comedones | Severe |

Source: O’Brien SC et al, 19989

Students were also investigated regarding sociodemographic (age; gender; family income), clinical (family history of AV; previous specific treatment; previous appointments with a dermatologist) and psychosocial variables (stress self-report; frequent manipulation of lesions; feelings of distress and embarrassment; fear that lesions will never cease; fear of being photographed or meeting acquaintances; impression when looking in the mirror; impact of AV in personal relationships. These behavioral attitudes and feelings related to acne were defined as psychosocial variables, based on previous reports about this issue.6,10

Research Instruments

The questionnaire was structured by researchers and composed of four parts:

1) Clinical and sociocultural questionnaire, with sociodemographic, clinical and psychosocial variables;

2) Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) for students up to 16 years of age and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), for those older than 16. Both are validated questionnaires, specific for skin diseases and adapted to Brazil. DLQI was developed by Finlay and Khan11 in 1994 and translated and validated to Portuguese, in Brazil, in 2004, by Martins, Arruda and Mugnaini.12 It includes the following domains: symptoms and feelings; daily activities; leisure; work/school; personal relationships and treatment. Patients must answer the questions having in mind the obstacles faced during the previous week. Scores on the questionnaire's scale vary from 0 to 30, and the higher the score, the worse the quality of life. A 0-1 score means the disease has no effect over the quality of life of the patient, 2-5 means a small effect, 6-10 a moderate effect, 11-20 a great effect and a 21-30 score means a very important effect of the disease over quality of life. CDLQI was created by Lewis-Jones and Finlay13 in 1995 to evaluate the quality of life of 4 to 16 year-old patients. In 2010, it was validated to Brazilian Portuguese by Prati et al.14 It includes the following domains: symptoms and feelings, interpersonal relationships, leisure, school, sleep and treatment. Similarly to DLQI, questionnaire scale scores vary from 0 to 30 and the higher the score, the worse the quality of life of the patient. A 0-1 score indicates no effect of the disease over the quality of life of the patient, a 2-6 score means a little effect, 7-12 a moderate one, 13-18 a great effect and a 19-30 score means a very important effect over quality of life.

3) Rosenberg's Self Esteem Scale (RSES) has been used worldwide since it was developed by Rosenberg in 1965 and revised by Hutz in 2011 as a one-dimensional tool capable of classifying the self-esteem level in low, medium and high.15,16 The original scale was developed for teenagers and has ten closed sentences, with five evaluating positive feelings and five evaluating negative feelings of the individual about himself The possible interval of this scale is 10 to 40.

The clinical evaluation form, filled by researchers during the dermatological physical examination, presented the following items: presence of AV, site of involvement and severity degree.

Inclusion criteria

The research sample was formed by high school students from a Joao Pessoa/PB school who accepted to participate in the study with the consent of their legal guardians.

Exclusion criteria

Students who carried any disease which compromised quality of life or self-esteem, who failed to answer two or more questions from validated questionnaires or who did not allow researchers to perform the dermatological physical examination were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, categorical variables were described through frequencies, interval variables of normal distribution by average and standard deviation and interval variables of non-normal distribution by median and quartiles.

For inferential analysis, the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied initially to verify normality of data distribution. Once the model was verified not to be parametric, quantitative variables were analyzed through Mann-Whitney test. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to verify associations between scores of CDLQI, DLQI and EAR tools with the degree of AV severity. Categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square independence test with Yates correction and by Fisher's exact test. For all analyses, a value p <0.05 was established as the cutoff point.

In all statistical calculations, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 for Windows software was used.

Ethical considerations

The school board where the study was performed issued a letter of consent with the necessary authorization. The study obtained approval from the Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital Lauro Wanderley, process numbers 03561712.4.0000.5183 and 03556112.5.0000.5183. The informed consent form was signed by the subjects or by their legal guardians, in the case of persons under the age of 18. They were guaranteed anonymity, confidentiality of information and the possibility of abandoning the study if so desired.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 355 students enrolled in a public high school in Joao Pessoa/PB, averaging 16 years of age (±1.1). Female gender predominated over male gender, with a frequency of 53% and 47%, respectively. Family income of 1 to 2 minimum wages was the most frequent (40.3% of sample).

Prevalence of students with acne vulgaris was of 89.3% (n=317), with a greater number for males (91%) than females (87.8%). Median duration of AV was 3 years (IIQ=2), with a minimum of 1 year and a maximum of 7 years.

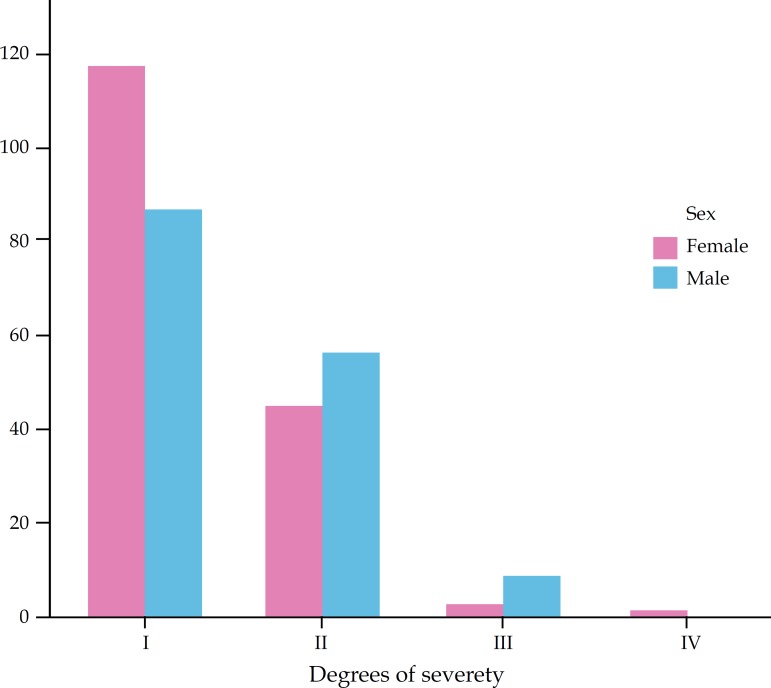

According to Leeds' classification revised by Cunliffe 2003, the majority of the sample with AV presented degree 1 (65%), followed by degree 2 (31.5%), degree 3 (2.8%) and only 1 individual with degree 4 (0.3%). Moderate and severe forms were most prevalent in males (ratio of prevalence of 1.47, CI 95%: 1.085-2.003) and the light degree in females, as demonstrated in graph 1. Fisher's exact test showed significant association between higher severity of AV and males (p=0.016), with correlation of moderate magnitude (Cramer's V = 0.171).

Graph 1.

Severity of acne vulgaris by gender in public school students of João Pessoa-PB, according to classification of Leeds revised by Cunliffe 2003. (n=317)

Regarding sites of involvement, 19.6% had acneic lesions on the anterior thorax, 30.9% on the dorsum, and 99.4% on the face, with 82.6% on the forehead, 77.6% on the jugal region, 44.8% on the mento and 60.6% in the nasal region.

From the AV group, 72.9% reported family history of AV, in contrast with the group without AV, whose prevalence was of 27.2%. Chi-square independence test with Yates correction demonstrated significant association of small effect between presence of acne vulgaris and family history of acne vulgaris, X2 = 13.754, p<0.001, phi=0.21.

Only 5% of AV patients had already visited the dermatologist with acneic lesions as the main complaint. However, 56.8% reported having used or having been using specific treatment for AV, with 87.2% as self-medication. Among those who consulted a dermatologist, half did not follow treatment as medically oriented, due to unfavorable financial conditions.

The most prevalent psychosocial variable among the students who carried AV was "fear that acne will never cease", observed in 58% of the cases, followed by "frequent manipulation of pimples", in 53.9% and next, "feeling distressed for having pimples" in 52.1% of the cases.

The remaining questions occurred among the minority of adolescents with AV: "consider himself as a stressed person" in 48.3%, "feels embarrassed due to pimples" and "does not like his/her own appearance when looking in the mirror" in 23.3%; "afraid of meeting people for the first time" in 21.8%; "fear of being photographed" in 19.2%; "believe AV negatively affects treatment received from other people" in 18.3%, and finally, "afraid of meeting acquaintances" in 8.5%. The questions did not get a statistically significant difference between groups with and without acne vulgaris, as seen in table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of psychosocial variables in students with and without AV in a public school of João Pessoa-PB (n=355)

| Psychosocial Issues | Presence of Acne | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With acne (n=317) | Withoout acne (n=38) | ||

| Considers himself a stressed person | 153 (48.6%) | 22 (57.9%) | 0.361 (NS) |

| Is afraid to have his picture taken | 61 (19.4%) | 8 (21.1%) | 0.975 (NS) |

| Likes his appearance when he looks in a mirror | 242 (76.6%) | 31 (81.6%) | 0.625 (NS) |

| Is afraid of meeting people for the first time | 69 (220%) | 7 (18,9%) | 0.822 (NS) |

| Is afraid of meeting acquaintances | 27 (8.5%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.356 (NS) |

p= statistical significnce. NS = Not Significant.

However, upon comparing the group with severity degree 1 (mild) with groups 2, 3 and 4 (moderate to severe), a statistically significant difference of low magnitude was observed in "Frequently manipulates pimples", "Feels distress for having pimples", "Afraid that acne will never cease" variables, which are more frequent in the moderate to severe degrees, and "Likes own appearance when looking in the mirror", which occurs with greater frequency in individuals with mild acne (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of psychosocial variables in students of a public school of João Pessoa-PB, according to degree of severity of acne (n=317)

| Variables | AV leve* | AV | p | X2 | V of Cramer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| moderate to severe** | |||||

| Considers himself a stressed person | 49.5% | 46.3% | 0.672 (NS) | 0.179 | 0.031 |

| Frequently manipulates pimples | 46.1% | 70.6% | <0.001 | 16.318 | 0.235 |

| Feels distressed for having pimples | 46.3% | 63.9% | 0.005 | 8.043 | 0.167 |

| Fears that lesions will never cease | 53.5% | 71.7% | 0.003 | 8.866 | 0.177 |

| Feels embarrassed regarding family and friends because of pimples | 19,9% | 30% | 0,060(NS) | 3,533 | 0,114 |

| Believes that his acne negatively affects the way others treat him | 18.1% | 20.2% | 0.767(NS) | 0.088 | 0.026 |

| Is afraid to have his picture taken | 17.1% | 23.9% | 0.195 (NS) | 1.679 | 0.082 |

| Likes his appearance when he looks in a mirror | 80.5% | 69.1% | 0.03 | 4.559 | -0.128 |

| Is afraid of meeting people for the first time | 20.6% | 25% | 0.453(NS) | 0.562 | 0.051 |

| Is afraid of meeting acquaintances | 8.3% | 9.2% | 0.947(NS) | 0.004 | 0.016 |

AV = Acne Vulgaris. p= statistical significance. X2= Chi-square value with correction of Yates. NS = Not Significant.

Degree 1 in the classification of Sampaio and Rivitii is considered as "mild AV".

Degrees 2, 3 and 4 in the classification of Sampaio and Rivitii are considered as "moderate to severe AV".

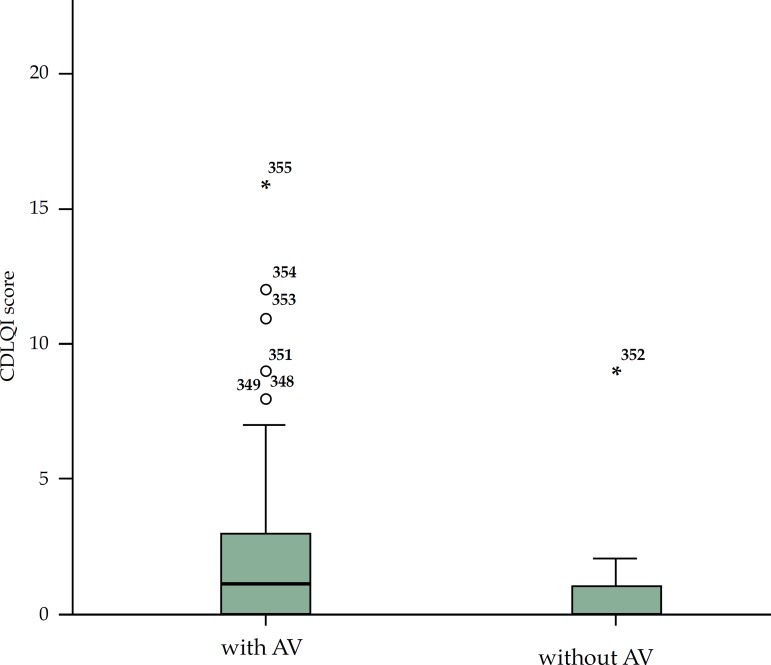

The CDLQI and DLQI scores were represented in graphs 2 and 3. Judging by the evaluation of the group of students who used the CDLQI score, AV had a small effect on 32.1%, moderate effect on 5.4%, great effect on 0.5% and no effect on 62%. The Mann-Whitney test demonstrated that the median of CDLQI score of students with AV 1 (IIQ: 0-3) was significantly different from those without AV 0 (IIQ: 0-1), p=0.003.

Graph 2.

Box diagram of CDLQI score in students younger than 16 years of age, with and without acne vulgaris, in a public school of João Pessoa-PB (n=247)

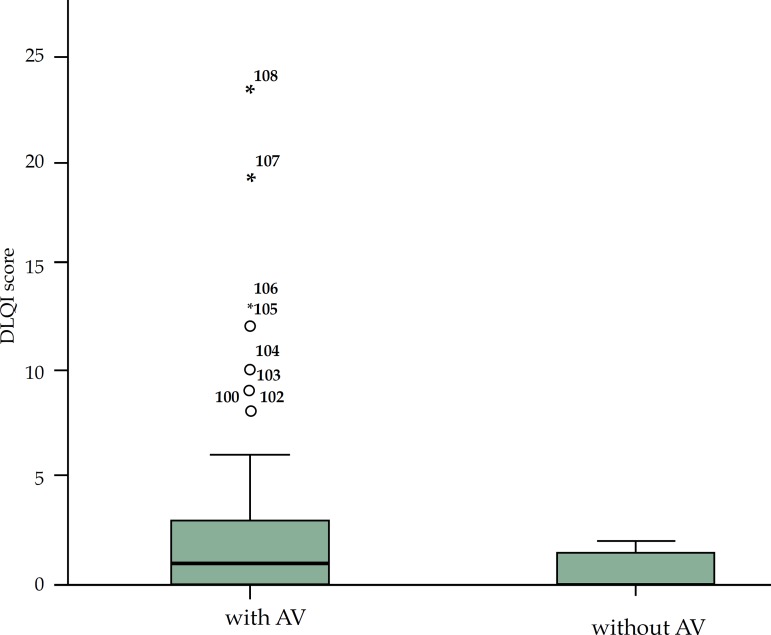

Graph 3.

Box diagram of DLQI score in students younger than 16 years of age, with and without acne vulgaris, in a public school of João Pessoa-PB (n=247) (n=108)

Judging by the evaluation of the group of students who used the DLQI score, AV had a small effect on 33.3%, moderate on 9.4%, great on 3.1%, very important on 1% and no effect on 53.1%. In an also significant way (p=0.038), the median of DLQI score of students with AV 1 (IIQ: 0-3) was different from those with AV 0 (IIQ: 0-1.5).

Adding the groups evaluated by the CDLQI and DLQI scores, the Mann-Whitney test demonstrated that the median of the scores of students with AV 1 (IIQ: 0-3) was significantly different from those without AV 0 (IIQ: 0-1), p<0.001.

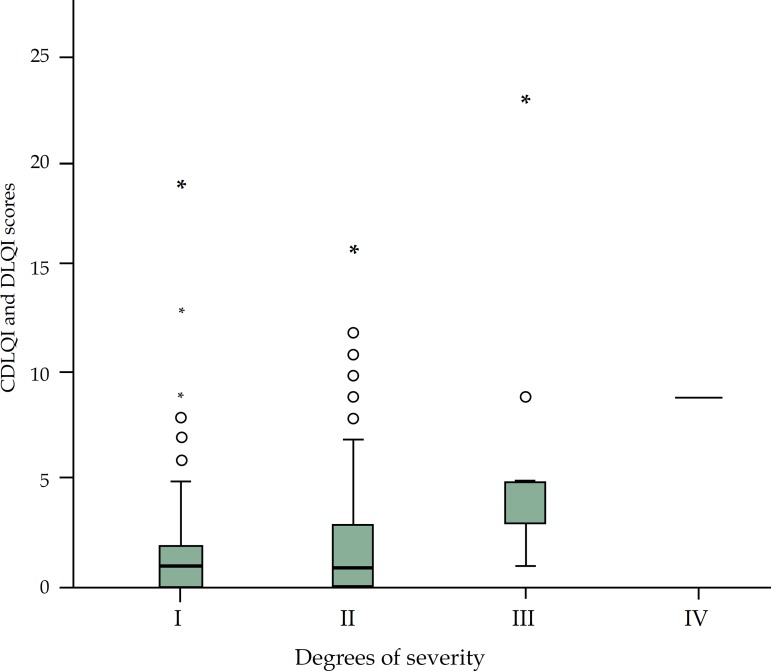

The medians of CDLQI and DLQI scores for mild AV were 1 and 1 respectively, moderate AV 1 and 2.5; with 5 and 3 for severe AV. There was significant positive correlation (p<0.001) of low magnitude (rho=0.197), so that the greater the degree of AV severity according to Sampaio and Rivitii classification, the greater the negative impact of AV on the quality of life of the patient (Graph 4).

Graph 4.

Quality of life according to CDLQI and DLQI scores / degrees of severity of acne vulgaris in students of a public school of João Pessoa-PB(n=355)

Self-esteem of students with AV, according to Rosenberg's score, presented a median of 7 (IIQ 4-11), with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 22. There was no statistically significant difference in Rosenberg's scale for groups with and without AV (p=0.551). There was no correlation between Rosenberg's scale and AV degrees of severity according to Spearman's correlation (p=0.689; rho=0.023).

DISCUSSION

According to literature, AV has a high frequency, with a prevalence varying between 39.9% and 96%, depending on the age bracket and the population studied.17 There was high prevalence of AV (89%), with predominance of the male sex, which also had higher onset of moderate to severe forms in comparison with the female sex. In the literature, the higher susceptibility of the male sex to the severe forms has already been well documented, but there are disagreements regarding prevalence including all degrees17-20 There was a higher number of adolescents with AV degree 1 (comedogenic), a prevalence that decreased with increased severity, so that only one individual in the sample presented degree 4. Several authors also described predominance of mild forms.10,17,19

Family health history was more frequent in the group with AV than in the group without AV, with prevalence of 72.9% and 27.2% respectively, an association statistically significant. Another study, with 1002 young Iranians, showed that AV risk doubled for those with a positive family history.21 The current hypothesis of the pathogenesis of AV in genetically predisposed adolescents consists of the combined action of androgens and specific ligands in the pilosebaceous unit, which influence in a complex form the differentiation/proliferation of infrainfundibular sebocytes and keratinocytes, leading to lipogenesis and comedogenesis.22

Actually, knowledge about the physiopathology of AV has been making considerable progress. In addition to the role of androgens, several other factors are involved. Hyperkeratosis by terminal keratinocyte differentiation disorder leads to retention of closed comedones. Propionibacterium acnes, acting on toll-like receptors, may stimulate cytokine secretion, such as interleukin (IL) -6 and IL-8 by follicular keratinocytes and IL-8 and -12 by macrophages, which originate inflammation. Certain P. acnes species may also induce an immunological reaction, stimulating production of antimicrobial peptides by sebocytes and keratinocytes that play an important role in the innate immunity of the follicle. These new aspects of AV pathogenesis, in their amplitude of linked factors, may offer strategies for individualized therapeutic plans in the future.22

Among the adolescents with AV, only 5% looked for medical care for specific treatment. We highlight the relevance of this information, as despite the fact of being such a prevalent dermatological illness, with severe forms of presentation, implications in quality of life and psychosocial impact, most of those affected do not receive medical care. This reflects on the lack of medical information regarding skin care, as detected by the high prevalence of inadequate behavior, such as frequent manipulation of lesions (present in 58%), use of inadequate products and self-medication (mentioned by 87.2% of the young people who had AV oriented treatment). Another factor is the social aspect, since besides the lack of access, half of the students who have already had appointments did not follow the treatment according to medical orientation due to unfavorable financial conditions. These issues constitute a warning regarding the need to develop awareness programs and to increase access to AV treatment through the health care system.

Several studies have used DLQI or CDLQI to compare quality of life in several dermatoses. Taborda et al, carried out a study with 1000 patients of a dermatological center in the south of the country and found altered QoL in melanocytic nevi, benign skin tumors, bacterial infections, contact eczemas, psoriasis, pruritus, hives and collagenoses. No reference was made to the association between QoL and AV, although this skin condition is present in 5.2% of the samples.23

Even more specific than DLQI or CDLQI, there is a questionnaire about QoL developed exclusively for patients with AV: the AcneQol. An article with its translation and validation into Portuguese was recently published, rendering it accurate for utilization in future Brazilian studies about QoL in this population.24

Average CDLQI scores were worse in the more advanced degrees: for mild AV it was 1.56, for moderate AV it was 2.18 and for severe AV it was 5.0, statistically significant. These findings were compatible with the study of Tasoula et al (2012), which investigated Greek adolescents with AV, whose average CDLQI scores were 2.94 for mild AV, 5.40 for moderate AV and 12.05 for severe AV, presenting significant correlation with higher averages at each stage. This study was carried out with 1531 adolescents between 11 and 19 years old, using a clinical questionnaire for acne severity self-mentioned by the adolescents. Only the CDLQI questionnaire was used regardless of the age of adolescents, extrapolating compatible age group, which would be up to 16 years old. Moreover, the classification of the sample into severity stages was done by the adolescent himself, generating information bias by classification error. Review studies about the psychosocial impact of AV point out to the incongruence between the assessment done by the patient and the medical evaluation of acne severity, the former being more subjective and influenced by factors such as anxiety, depression and loss of self-esteem.25 In this sense, the subject who believes he has more severe AV is possibly the one who will have the worst scores on self-esteem scales.19

The most prevalent psychosocial issue in our study was "fear that acne will never cease", present in 58% of cases. The study of Ribas et al presented different results: the most common attitude or feeling triggred by acne was "frequent manipulation of lesions", observed in 77% of cases, followed by "distress for having acne", in 73%. In our study, the issues: "fear that acne will never cease", "aversion to looking at himself in the mirror", "social inadequacy (embarrassed) by physical appearance" and "afraid of meeting people for the first time and meeting acquaintances" had greater prevalence than that found by Ribas et al. This may be a consequence of the fact that, while the sample of that study was composed of medical students, the sample of this study was composed of adolescents, an age group where interpersonal relationships are more conflicting. Social acceptance is an extremely relevant factor in the adolescent age group, and skin lesions such as AV may generate repercussions like inhibition, timidity and anxiety.10

According to a study by Tasoula et al, the body image of adolescents is modified by several factors, among which one of the most important is peer pressure, which makes the question: "Do you believe that your acne negatively affects the way others (acquaintances, parents, friends, teachers, the opposite sex, etc) treat you?" adequate to assess body image. As visualized in tables 2 and 3, the item "Do you believe that your acne negatively affects the way others treat you" had no statistical significance, therefore AV was not found to alter body image of adolescents. It was not informed which basis Tasoula et. al used to impart to this question the meaning of individual body image, which we consider quite simplistic. Among the study variables, we consider the question "Do you like your appearance when you look in the mirror" would be more pertinent to define alteration of body image by AV. In fact, the use of a questionnaire validated for this purpose would be required, but our review of the literature only found questionnaires about body image directed to body fat accumulation and overweight, with scarcity of questions about the skin, therefore incompatible with this study.19

According to Rosenberg, the low self-esteem is characterized by feelings of inadequacy, incompetence and incapability of facing challenges; the average is expressed by the oscilation of the individual between feelings of self-approval and rejection; and high self-esteem consists of self-judgement of value, competence and trust.15 It is expected that AV, being a dermatosis that compromises the esthetics of the face and other exposed areas, will negatively alter the self-esteem of those it affects, mainly those who are adolescents. However, in this low-income population sample, mainly concerned about its own subsistence, no association was found between self-esteem measured by Rosenberg›s scale and AV, nor with the severity of AV. It is supposed that this score will assess self-esteem in a wide scope, including general skills and feelings of uselessness, among others, different from the dermatology orientation expressed in questionnaires DLQI and CDLQI. This can be seen in the studty by Tasoula19, which evaluated each category in these scores, the most affected CDLQI field concerned self-esteem, showing the potential impact of the disease in this sense. Teixeira et al also emphasize the difficulty in foreseeing the real impact of AV on self-esteem, since it may be influenced by several factors, such as age, basal self-esteem, family support and subjacent psychiatric pathology.23,25

CONCLUSION

AV has a great importance among the dermatoses that affect adolescents, in view of its high prevalence in this age group and its effect on the QoL of those affected, which becomes more pronounced as the stage of the disease becomes more severe. Since adolescence is a period marked by conflicting relationships and difficulties in social acceptance, AV has the potential to generate inhibition, timidity and anxiety. This psychological implication should be approached and valued in the management of patients with this condition.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Financial Support: None.

How to cite this article: Vilar GN, Santos LA, Sobral Filho JF. Quality of life, self-esteem and psychosocial factors in adolescents with acne vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):622-9.

Study carried out at Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB) – João Pessoa (PB), Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ongenae K, Beelaert L, van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas DR. Psychosocial Effects of Acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:3–5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreno B, Daniel F, Allaert FA, Aube I. Acne: evolution of the clinical practice and therapeutic management of acne between 1996 and 2000. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azulay DA, Azulay RD, Azulay-Abulafia L. Azulay DA, Azulay RD, Azulay-Abulafia L. Dermatologia. 5 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2011. Acne e doenças afins; pp. 506–516. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkrishnan R, McMichael AJ, Hu JY, Camacho FT, Shew KR, Bouloc A, et al. Correlates of health-related quality of life in women with severe facial blemishes. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teixeira MAG, França ER. Mulheres adultas com acne: aspectos comportamentais, perfis hormonal e ultrassonográfico ovariano. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2007;7:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, Finlay AY. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke BM, Cunliffe WJ. The assessment of acne vulgaris - the Leeds technique. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien SC, Lewis JB, Cunliffe WJ. The Leeds revised acne grading system. J Dermatol Treat. 1998;9:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribas J, Oliveira CMPB. Acne vulgaris and well-being in medical students. An Bras Dermatol. 2008;83:520–525. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins GA, Arruda L, Mugnaini ASB. Validation of life quality questionnaires for psoriasis Patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:521–535. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): Initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prati C, Comparin C, Boza JC, Cestari TF. Validação para o português falado no Brasil do instrumento Escore da Qualidade de Vida na Dermatologia Infantil (CDLQI) Med Cutan Iber Lat Am. 2010;38:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutz CS, Zanon C. Revisão da adaptação, validação e normatização da escala de autoestima de Rosenberg. Aval Psicol. 2011;10:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa A, Alchorne MMA, Goldschmidt MCB. Etiopathogenic features of acne vulgaris. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2008;83:451–459. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobral JF, Filho, Nunes Maia HGS, Fonseca ESVB, Damião RS. Aspectos epidemiológicos da acne vulgar em universitários de João Pessoa - PB. An Bras Dermatol. 1993;68:225–228. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, Lazarou D, Danopoulou I, Katsambas A, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece: results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:862–869. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunliffe W. The acne. London: Dunitz; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghodsi SZ, Orawa H, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: a community-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2136–2141. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, Wang X, Xiang LF, Xia L, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:821–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taborda ML, Weber MB, Teixeira KA, Lisboa AP, Welter Ede Q. Evaluation of the quality of life and psychological distress of patients with different dermatoses in a dermatology referral center in southern Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:52–56. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamamoto Cde S, Hassun KM, Bagatin E, Tomimori J. Acne-specific quality of life questionnaire (AcneQol): translation, cultural adaptation and validation into Brazilian-Portuguese language. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:83–90. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teixeira V, Vieira R, Figueiredo A. Impacto psicossocial da acne. Revista SPDV. 2012;70:291–296. [Google Scholar]