Abstract

BACKGROUND

Patch testing is an efficient method to identify the allergen responsible for allergic contact dermatitis.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the results of patch tests in children and adolescents comparing these two age groups' results.

METHODS

Cross-sectional study to assess patch test results of 125 children and adolescents aged 1-19 years, with suspected allergic contact dermatitis, in a dermatology clinic in Brazil. Two Brazilian standardized series were used.

RESULTS

Seventy four (59.2%) patients had "at least one positive reaction" to the patch test. Among these positive tests, 77.0% were deemed relevant. The most frequent allergens were nickel (36.8%), thimerosal (18.4%), tosylamide formaldehyde resin (6.8%), neomycin (6.4%), cobalt (4.0%) and fragrance mix I (4.0%). The most frequent positive tests came from adolescents (p=0.0014) and females (p=0.0002). There was no relevant statistical difference concerning contact sensitizations among patients with or without atopic history. However, there were significant differences regarding sensitization to nickel (p=0.029) and thimerosal (p=0.042) between the two age groups under study, while adolescents were the most affected.

CONCLUSION

Nickel and fragrances were the only positive (and relevant) allergens in children. Nickel and tosylamide formaldehyde resin were the most frequent and relevant allergens among adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescent; Allergens; Child; Dermatitis; Dermatitis, allergic contact; Patch tests

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have been published in the last 15 years describing the profile of patch tests in children and adolescents with suspected allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), showing a variation in contact sensitization (26.0-95.6%) and in the positive tests' clinical relevance (30.5-100.0%).1-35

However, most of these studies are European and few data on the subject exist in Brazil.15,31 Furthermore, few studies provide the respective data on both age groups for comparison.13,30,32 Most of the services mentioned use the standard allergens series.1-35 In Brazil, there are two available standard patch test series: standard and cosmetics. Usually, patients undergo patch testing with the standard series. When necessary, the cosmetics series is also applied. Using this complementary cosmetics series increases costs and complicates the technique in children due to their smaller back surfaces for test application and the increased annoyance caused by the greater number of substances administered.

This study seeks to evaluate patch test results in children and adolescents from a dermatology clinic in Brazil, identifying the most frequent allergens, comparing them across both age groups and evaluating the need to apply the complementary cosmetics series.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An observational, cross-sectional study was undertaken to assess the patch test results of 125 children and adolescents aged 1-19 years, with suspected ACD, at the Dermatology Clinic of the Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Charity Hospital, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

We examined records containing data on patch test results for children and adolescents carried out between 01/07/2003 and 30/06/2010. The sample was non-probabilistic and intentional, while patients were selected in sequential fashion according to the excluision and inclusion criteria established.

The data were collected and stored in the EpiInfo 3.5.1. Statistical program. The Chi- square test was used to analyze the categorical variables, along with Fisher Exact Test, when needed. The significance level for all analyses was 0.05.

The materials used for the patch tests comprised two series (FDA-Allergenic, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) standardized by the Brazilian Contact Dermatitis Study Group (Grupo Brasileiro de Estudo em Dermatite de Contato-GBEDC): the Brazilian Standard Patch Test Series, composed of 30 allergens, and the Brazilian Cosmetics Standard Patch Test Series, made up of 10 allergens, and the Finn Chambers (Epitest Ltd Oy Tuusula, Finland) on Scanpor tapes. Test procedures and readings were conducted in accordance with international recommendations from the ICDRG (International Contact Dermatitis Research Group).36 The tests were applied and left on patients' backs for 48 hours. The reading was carried out 48 and 96 hours after the test application. Only the latter reading was considered for the statistical analysis. Substance concentrations were the same as in adults.

Only current clinical relevance was considered in order to calculate the frequency of positive tests' relevance (if tests were positive for a certain substance and where it was possible, known, or proved that the substance was a component from products patients had contact with). Past clinical relevance was not considered to calculate the tests' relevance. Atopic history was taken into account if the patient had a history of at least one of the following items: allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis or asthma.

This study was approved by The Ethics Committee of the Charity Hospital of Belo Horizonte (Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Belo Horizonte) and The Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais-UFMG).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients:

Patch test results were evaluated in 125 patients, 96 girls (76.8%) and 29 boys (23.2%), aged 1-19, including 18 children, aged 1-9, in addition to 107 adolescents aged 10-19, with a mean age of 14.3 ±3.8 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of children’s and adolescents’ characteristics studied at the Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Dermatology Clinic (n=125)

| Variables | Category | Age | Age | Total | Statistical | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 9 years | 10 to 19 years | Test | value | |||

| n=18 | n=107 | n=125 | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Gender | Female | 12 (66.7) | 84 (78.5) | 96 (76.8) | Fisher* | 0.36 |

| Male | 6 (33.3) | 23 (21.5) | 29 (23.2) | |||

| Dermatitis | 1 to < 6 months | 1 (5.5) | 9 (8.4) | 10 (8.0) | χ2=10.50† | 0.0328 |

| evolution | 6 months to <1year | 0 (0.0) | 15 (14.0) | 15 (12.0) | ||

| time prior | 1 year to < 5years | 12 (66.7) | 60 (56.0) | 72 (57.6) | ||

| to the | 5 years to10 years | 5 (27.8) | 9 (8.4) | 14 (11.2) | ||

| Patch test | > 10 years | 0 (0.0) | 14 (13.0) | 14 (11.2) | ||

| Personal | Yes | 11 (61.1) | 54 (50.5) | 65 (52.0) | χ2=0.34 | 0.56 |

| Atopy | No | 7 (38.9) | 53 (49.5) | 60 (48.0) | ||

| Family | Yes | 7 (38.9) | 49 (45.8) | 56 (44.8) | χ2=0.0 | 0.96 |

| Atopy | No | 9 (50.0) | 56 (52.3) | 65 (52.0) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (11.1) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (3.2) |

Fisher Exact Test;

Chi-Square Test

Dermatitis evolution time prior to the patch test varied from 1 month to over 10 years. In 72 (57.6%) children and adolescents, the time varied from 1 year to under 5 years, while among 100 patients it was equal to or over 1 year (Table 1).

Personal and family atopic history were detected in 65 (52.0%) and 56 (44.8%) of the children and adolescents (Table 1). No significant differences were found upon examining atopic association with the age groups of patients to be tested.

Among the patients studied, 102 (81.6%) were students, 8 (6.4%) were cleaners, 3 (2.4%) were cooks, 3 (2.4%) worked in esthetic care, 3 (2.4%) were office workers and 2 (1.6%) worked in construction.

The head and hands were the sites most affected by dermatitis, followed by the feet, trunk and neck. There were significant statistical differences concerning dermatitis rates in the neck and hands and the age groups studied, with a higher frequency of dermatitis in these locations among adolescents and greater absence of dermatitis in these locations among children (Table 2). Twenty-eight patients had dermatitis in more than three body areas.

Table 2.

Body locations affected by dermatitis in the children and adolescents studied at the Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Dermatology Clinic (n=125)

| Body | Dermatitis | 1 to 9 years | 10 to 19 years | Total | Statistical | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | n=18 | n=107 | n=125 | test | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Head | Yes | 7 | 50 | 57 (45.6) | χ2= 0.13* | 0.720 |

| No | 11 | 57 | 68 (54.4) | |||

| Neck | Yes | 1 | 39 | 40 (32.0) | χ2= 5.41 | 0.020 |

| No | 17 | 68 | 85 (68.0) | |||

| Trunk | Yes | 3 | 38 | 41 (32.8) | χ2= 1.70 | 0.190 |

| No | 15 | 69 | 84 (67.2) | |||

| Feet | Yes | 9 | 37 | 46 (36.8) | χ2= 0.98 | 0.320 |

| No | 9 | 70 | 79 (63.2) | |||

| Hands | Yes | 2 | 47 | 49 (39.2) | χ2= 5.65 | 0.017 |

| No | 16 | 60 | 76 (60.8) | |||

| Forearms | Yes | 2 | 33 | 35 (28.0) | χ2= 2.08 | 0.150 |

| No | 16 | 74 | 90 (72.0) | |||

| Arms | Yes | 2 | 23 | 25 (20.0) | Fisher† | 0.520 |

| No | 16 | 84 | 100 (80.0) | |||

| Legs | Yes | 3 | 20 | 23 (18.4) | Fisher | 1.000 |

| No | 15 | 87 | 102 (81.6) | |||

| Thighs | Yes | 4 | 12 | 16 (12.8) | Fisher | 0.240 |

| No | 14 | 95 | 109 (87.2) |

Chi-Square Test;

Fisher Exact Test

Regarding the initial dermatitis site, the greatest frequencies occurred on the face (n=31; 24.8%), feet (n=31; 24.8%), hands (n=21; 16.8%) and trunk (n=16; 12.8%).

Results of patch test performed:

Out of the 125 patients tested, 74 had "at least one positive reaction" (one or more positive tests), while the contact sensitization rate was 59.2% (74/125). The frequency of negative tests was 40.8% (51/125).

Among the 74 patients who had "at least one positive reaction", 57 (57/74; 77.0%) had presented current clinical relevance to their positive tests and had received a diagnosis of ACD (57/125; 45.6%). The frequency of clinical relevance (current) calculated from the total number of studied patients was 45.6%. Irritant contact dermatitis was diagnosed in 32 (25.6%) patients, while other dermatoses were diagnosed in 36 (28.8%) patients.

Positive tests were more common among females (p=0.0002) than males (Table 3). Further, there was a higher frequency of positive tests among adolescents (p=0.0014) than children (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of the variables studied in relation to the positivity of "at least one positive patch test" (n=125)

| Variables | Category | Negative | One or more | Statistical | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| test | Positive tests | test | |||

| Gender | Female | 30 | 66 | χ2=13.97* | 0.0002 |

| Male | 21 | 8 | |||

| Age groups | Children | 14 | 4 | χ2=10.18 | 0.0014 |

| Adolescents | 37 | 70 | |||

| Only Standard | Female | 15 | 16 | χ2= 4.32 | 0.0377 |

| Series | Male | 17 | 4 | ||

| Standard Series | Female | 15 | 50 | Fisher | 0.19 |

| and Cosmetics | Male | 4 | 4 | ||

| Personal Atopy | Yes | 25 | 40 | χ2= 0.14 | 0.71 |

| No | 26 | 34 | |||

| Family Atopy | Yes | 20 | 36 | χ2= 1.78 | 0.41 |

| No | 30 | 35 | |||

| Not reported | 1 | 3 |

Chi-Square Test

There was no significant statistical difference concerning contact sensitization among patients with atopic history (personal and family) and those without atopic history (Table 3).

All children and adolescents (n=125) in this study were tested using the Brazilian Standard Patch Test Series. Seventy-three patients were tested with both series (the Brazilian Standard and Brazilian Cosmetics Standard Patch Test Series). Fifty-two patients were tested with the Brazilian Standard Series alone, while no patient was tested only with the Brazilian Cosmetics Series.

Regarding the number of substances tested, among the 52 patients who were tested only with 30 substances (Brazilian Standard Series), just 20 (38.5%) patients had positive tests and there was a significant statistical difference related to gender (Table 3). Out of 73 patients tested with 40 substances (Brazilian Standard Series and Standard Cosmetics), 54 (74.0%) had positive tests, with no significant statistical difference concerning gender (Table 3).

One hundred and seventeen positive tests were found: 111 from the Brazilian Standard Series and 6 from the Cosmetics Series (Tables 4 and 5). In patients with positive tests, the average number of positive tests per patient was 1.58 (117/74). Polysensitization ocurred in 29 patients (29/125; 23.2%).

Table 4.

Distribution of patch test results from the Brazilian Standard Series for children and adolescents, according to the age groups studied (n= 125)

| Substances/ | Test Results | 1 to 9 years | 10 to 19 years | Total n=125 n (%) | p* Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | n=18 n (%) | n=107 n (%) | |||

| Nickel sulfatef | Positive | 2 (11.1) | 44 (41.1) | 46 (36.8) | 0.029 |

| 5.0% | Negative | 16 (88.9) | 63 (58.9) | 79 (63.2) | |

| Thimerosal | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 23 (21.5) | 23 (18.4) | 0.042 |

| 0.05% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 84 (78.5) | 102 (81.6) | |

| Neomycin | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 8 (7.5) | 8 (6.4) | 0.60 |

| 20.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 99 (92.5) | 117 (93.6) | |

| Cobalt chloride | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.7) | 5 (4.0) | 1.00 |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 102 (95.3) | 120 (96.0) | |

| Fragrance mix | Positive | 2 (11.1) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (4.0) | 0.15 |

| 7.0% | Negative | 16 (88.9) | 104 (97.2) | 120 (96.0) | |

| Formaldehyde | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.7) | 4 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 103 (96.3) | 121 (96.8) | |

| Potassium | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | 1.00 |

| dichromate 0.5% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 104 (97.2) | 122 (97.6) | |

| Ethylenediamine | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | 1.00 |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 104 (97.2) | 122 (97.6) | |

| Myroxylon | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| pereirae 25.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 105 (98.1) | 123 (98.4) | |

| PPD mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| 0.4% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 105 (98.1) | 123 (98.4) | |

| Quinoline mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| 6.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 105 (98.1) | 123 (98.4) | |

| Antraquinone | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 2.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Hydroquinone | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Kathon CG | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 0.5% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Mercapto mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 2.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Quaternium-15 | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 0.5% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Carba mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 3.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Promethazine | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Colophony | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| 20.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 106 (99.1) | 124 (99.2) | |

| Propylene glycol | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0,0) | -‡ |

| 10.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125(100,0) | |

| p-tert-Butylphenol | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100,0) | |

| Irgasan | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Lanolin | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 30.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Thiuram mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Benzocaine | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 5.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Nitrofurazone | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Paraben mix | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 15.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Epoxy resin | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| Turpentine | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 10.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) | |

| para-Phenylene | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| diamine 1.0% | Negative | 18 (100.0) | 107 (100.0) | 125 (100.0) |

Fisher Exact Test;†The vehicle used is solid petrolatum, except for formaldehyde, for which water is used.

Statistical Test not applicable MIX composition: PPD mix (N-isopropyl, N-phenyl, paraphenylenediamine, N-N-diphenyl-, paraphenylenediamine); Kathon CG (methylchloroisothiazolinone, methylisothiazolinone); Thiuram mix (tetramethylthiuram disulfite, tetramethyltiuram monosulfite); Fragrance mix I (eugenol, isoeugenol, geraniol, cinnamic alcohol, alpha aldehyde amyl cinnamic, absolute oak moss, hydroxycitronellal; Mercapto mix (NCyclohexyl 2 benzothiazolesulfenamide, morpholinylmercaptobenzothiazole, dibenzothiazyl disulfide, mercaptobenzothiazole); Quinoline mix (clioquinol, clorquinaldol); Paraben mix (butyl, ethyl, propyl, benzyl, methyl parabens); Carba mix (diphenylguanidine, zinc dimethhylcarbamate, zinc diethylcarbamate).

Table 5.

Distribution of patchtest results from the Brazilian Cosmetics Series for children and adolescents, according to the age groups studied (n=73)

| Substances/ | Test Results | 1 to 9 years | 10 to 19 years | Total | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | n= 4 n (%) | n= 69 n (%) | n=73 n (%) | Value | |

| Tosylamide | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.2) | 5 (6.8) | 1.00 |

| formaldehyde resin10.0%f | Negative | 4 (100.0) | 64 (92.8) | 68 (93.2) | |

| Chloroacetamide 0.2% | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1.00 |

| Negative | 4 (100.0) | 68 (98.6) | 72 (98.6) | ||

| Germal 115 | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -‡ |

| (imidazolidinylurea) 2.0% | Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | |

| BHT (Butylhydroxy- | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| toluene) 2.0% | Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | |

| Triethanolamine 2.5% | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | ||

| Bronopol (2-Bromo-2- | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| nitropropane-1,3-diol) 0.5% | Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | |

| Sorbic acid 2.0% | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | ||

| Ammonium thioglycolate | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 2.5% | Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | |

| Amerchol L- 101 100.0% | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) | ||

| Chlorhexidine 0.5% | Positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Negative | 4 (100.0) | 69 (100.0) | 73(100.0) |

Fisher Exact Test; †the vehicle used is solid petrolatum, except for chlorhexidine, for which water is applied;

Statistical Test not applicable

In the Brazilian Standard Series, the substances with the highest sensitization frequency in children and adolescents (n=125), were as follows (in descending order): nickel sulfate (n=46; 36.8%), thimerosal (n=23, 18.4%), neomycin (n=8; 6.4%), cobalt chloride and fragrance mix (n=5; 4.0% each), formaldehyde (n=4; 3.2%), potassium dichromate and ethylenediamine (n=3; 2.4% each). The less frequent substances, showing no positive reaction to this series, were as follows: propylene glycol, p-tert-Butylphenol, irgasan, lanolin, thiuram mix, benzocaine, nitrofurazone, paraben mix, epoxy resin, turpentine and para-Phenylenediamine (Table 4).

Children (n=18) had positive reactions only to nickel and fragrance mix (two positive tests each), both components of the Brazilian Standard Series (Table 4).

There was a significant statistical difference (p=0.029) between the two age groups concerning sensitization to nickel: 2 positive tests (2/18; 11.1%) in children versus 44 positive tests (44/107; 41.1%) in adolescents. The same occurred with thimerosal (p=0.042): no positive test (0/18; 0.0) in children versus 23 (23/107; 21.5%) in adolescents (Table 4).

Among the substances tested with the Brazilian Cosmetics Series, with respect to children and adolescents (n= 73), no positive reactions emerged in children and only two substances entailed positive reactions in adolescents: tosylamide formaldehyde resin (n=5; 6.8%) and chloroacetamide (n=1; 1.4%) (Table 5).

As for the allergen sources concerning the positive tests, not all the information was available in the patients' records (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sources of the most common allergens in the children and adolescents tested

| Allergens | Allergen sources | Number of children and adolescents |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel sulfate | jewelry, piercings | 13 |

| metals on clothes and shoes | 6 | |

| nail clippers | 1 | |

| razor blade | 3 | |

| cosmetics | 1 | |

| Thimerosa! | vaccines | 23 |

| Tosylamide formaldehyde* | nail polish | 5 |

| Neomycin | topical medicine | 8 |

| Cobalt chloride | jewelry | 4 |

| metals on clothes | 1 | |

| Fragrance mix | cosmetics, fragrances | 2 |

| Formaldehyde | cosmetics, nail polish | 3 |

| Potassium dichromate | cement | 1 |

| magnet | 1 | |

| shoes | 1 | |

| Ethylenediamine | cosmetics | 2 |

| Myroxylon pereirae | cosmetics, fragrances | 2 |

| Carba mix, PPD mix | rubber glove | 2 |

tosylamide formaldehyde resin

With respect to the nine most frequent allergens, positive tests were more common in females. Potassium dichromate was more common among males. Out of 46 positive tests for nickel, 37 were deemed relevant. It was difficult to determine the relevance of cobalt as it had no positivity alone (4 of its 5 positive tests were found in the same patients who also had positive tests for nickel). All the positive tests for potassium dichromate, Myroxylon pereirae and tosylamide formaldehyde resin, were deemed relevant. However, positive tests for thimerosal and neomycin had no current clinical relevance (Table 7).

Table 7.

Most frequent allergens and current clinical relevance in children and adolescents

| Substances | Patients | Positive | Positive | Positive | Relevance* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tested | tests | tests | tests | present | ||

| F† | M‡ | |||||

| n | n | n | n | % | n (%) | |

| Nickel sulfate | 125 | 46 | 43 | 3 | 36.8 | 37 (80.4) |

| Thimerosal | 125 | 23 | 20 | 3 | 18.4 | 0 (0.0) |

| Tosylamide resin§ | 73 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 6.8 | 5 (100.0) |

| Neomycin | 125 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 6.4 | 0 (0.0) |

| Cobalt chloride | 125 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4.0 | 5 (100.0)| |

| Fragrance mix | 125 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4.0 | 2 (40.0) |

| Formaldehyde | 125 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3.2 | 3 (75.0) |

| Potassium dichromate | 125 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2.4 | 3 (100.0) |

| Ethylenediamine | 125 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2.4 | 2 (66.7) |

| Myroxylon pereirae | 125 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1.6 | 2 (100.0) |

Relevance calculated based on the number of positive tests ;

female;

male;

tosylamide formaldehyde resin;

relevance of cobalt together with another metal: relevance questioned

As regards the intensity of the relevant positive reactions, 48 relevant tests were found, with intensity reaction 1+, including the 27 nickel tests and all the 5 positive tosylamide formaldehyde resin tests.

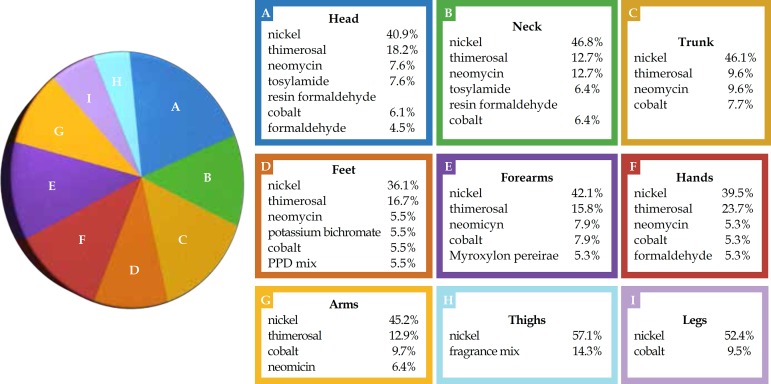

In patients with positive tests, the head and trunk were the body areas most commonly affected by dermatitis. There was a significant difference concerning dermatitis location in the thighs of patients who had positive tests, with higher positivity in children's thighs than in other areas (p=0.0068). Among the most frequent and relevant allergens, nickel, tosylamide formaldehyde resin and formaldehyde were particularly prominent in head involvement; nickel, potassium dichromate and PPD mix significantly affected the feet, while nickel and fragrances had clear impacts on the forearms and thighs (Graph 1). Twenty-eight patients had four or more areas affected, regarded as dermatitis generalization,37 out of which 16 had relevant positive tests (12 for nickel), while 3 had irrelevant positive tests and 9 had negative tests.

Graph 1.

Positive reactions of the most frequent allergens in relation to body location affected by dermatitis in the children and adolescents tested (n=74)

With respect to the frequency of relevant positive tests and the initial dermatitis location, all cases that presented initial involvement on the neck entailed relevant positive tests (100.0%). Twelve out of 16 patients (75.0%) whose lesions appeared initially on the trunk had relevant positive tests, especially those with initial lesions on the armpit (71.0% cases; 5/7). The thighs and legs also exhibited high positivity: 66.7% (6/9) of cases of initial dermatitis in the thighs and legs returned relevant positive tests. About half the initial dermatitis on the face entailed relevant positive tests, particularly lesions in the periorbital area/eyelids (71.0% of cases; 10/14).

DISCUSSION

This study uncovered a frequency of 59.2% for "at least one positive reaction" (74/125), consistent with the literature regarding patch test results in selected samples (children and adolescents suspected of ACD) that showed a variation of 26.0-95.6%.1-35 The clinical relevance (current) frequency of 77.0%, calculated based on the number of patients with one or more positive tests (57/74; 77.0%) proved to be consistent with the literature data, which varied from 30.5% to 100.0%.1-35 These relatively high frequencies may be due to: the sample type selected, the number of substances tested and the age group studied. Between 30 and 40 substances were tested and this study included children as young as 12 months, as well as adolescents aged up to 19 years. Several studies have been carried out in patients with suspected ACD. Of these, some focused only on children17,23,28, others examined mostly children and adolescents aged up to 12 years2,12,31 whereas another study analyzed only adolescents15. Others studied patients from both age groups, aged up to 19-201,3-11,13,14,16,18-22,24-27,29,30,32,33-35, and tested a smaller or greater number of substances than in this study: 17 substances for children under 5 years old11; a pediatric series of 30 substances23,24,25; 30 substances for children under 10 years old12; and series of 10 substances.30 Other studies have used standardized series for adults1,2,5-11,13-16,19-22,25,27,28,31,33-35, with variation in the number of substances tested.

A diagnosis of ACD occurred in 45.6% of the patients tested, virtually half the total number of cases, thus demonstrating the importance of carrying out the contact test when this diagnosis is suspected so as to differente it from other, common childhood skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, and check their concomitance.

In this study, there was a higher frequency of positive tests among female adolescents, perhaps attributable to the use of piercings, cosmetics, fragrances, etc., which are common in this age group and gender. Three studies showed a significant difference concerning contact sensitization frequency and gender, two of which revealed a higher frequency in girls14, while the other found a greater frequency in boys.23 However, there are five studies that did not uncover any significant difference in this respect.3,12,16,20,29 Furthermore, as regards age, seven studies demonstrated that there was no difference regarding contact sensitization related to this aspect.13,16,19,20,22,23,29 Three studies found a greater frequency of positive tests among higher age groups: 11-16 years old1,9,14, and three in children under 3.2,11,12

The lengthy evolution of dermatitis prior to the patch test (equal to or higher than one year in 100 patients), can be explained by: the lack of suspected ACD diagnosis, non-differentiation between ACD and atopic dermatitis, ignorance about the patch test's relevance, reluctance to refer children for the test due to its technical difficulties. This delay in performing the patch test can delay improvement of these patients' quality of life.

The number of tested patients with atopic history was similar to the number of tested patients without atopic history. Our study revealed no significant statistical difference regarding contact sensitization between patients with or without atopic history, which is consistent with other studies.4,10-12,15,16,18,23,35 A study of adults (with no suspected ACD) showed that contact sensitization was significantly correlated with atopic dermatitis (nickel and thimerosal were excluded to avoid bias), though the reading only occurred 48 hours after the patch test application, favoring false-positive and false-negative results.38

Polysensitization occurred in 29 (23.2%) of the 125 patients under study, consistent with the literature. Six studies had the following polysensitization rates: 51.0%, 42.0%, 29.6%, 19.6%, 17.8% of the tested children and 54.0%, 51.0% of the positive test cases.2,7, 12,16,19,23,35

In our study, the most common allergens were nickel, thimerosal, tosylamide formaldehyde resin, neomycin, cobalt, fragrance mix, formaldehyde, potassium dichromate, ethylenediamine and Myroxylon pereirae. Except for the tosyilamide formaldehyde resin and ethylenediamine, these findings are consistent with most studies of selected samples for these age groups. Other allergens are mentioned in the literature among the ten most frequent in children and adolescents' patch-tests: lanolin,1,2,11,12,14,16,18,19,27,28,31,33,34 para-Phe nylenediamine,2,5,7,8,13-6,28,29 colophony,1,4,5,14,16,29-31,33,34 quaternium-15,8,15,16,25,31 p-tert-Butylphenol,2,5,12,25,33,34 Kathon CG,2,12,23,30,35 rubber derivatives4,6-8,14,19,22,26 gold thiosulphate,16,20,21 disperse dyes,23,26 cocamidopropylbetaine,23,26 tixocortol pivalate7,33,34 propolis12,32,35 and paraben mix.28,29 Five of these last allergens mentioned as the most common in the literature (p-tert-Butylphenol, lanolin, thiuram mix, paraben mix and para-Phenylenediamine) had no positive reaction at all for children and adolescents in this study and some have not been tested with the Brazilian Series (gold thiosulphate, disperse dyes, cocamidopropylbetaine, tixocortol pivalate and propolis).

The most frequent allergens found in children were nickel and fragrance mix, whereas in adolescents, the most common were nickel, thimerosal, tosylamide formaldehyde resin, neomycin, cobalt, formaldehyde, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix and ethylenediamine. The statistical difference between the two age groups as regards nickel can be explained by the greater use of piercings among adolescents. Studies show a significant association between nickel and piercing39,40 and demonstrate that multiple piercings increase the risk of contact sensitization to nickel.41 In addition, the statistical difference between the two age groups studied with respect to thimerosal is attributable to the higher number of vaccinations received by the adolescents compared with children.42,43

Nickel was the most common allergen in this study, for both age groups, with a contact sensitization frequency of 36.8%, thus consistent with the literature about suspected ACD patients, in which frequency varies from 7.76% to 46.0%.1,8 Its clinical relevance in this study was 80.4% of the positive tests, and can be explained by the use of jewelry, clothing accessories and footwear, nail clippers, razor blade and cosmetics. Nickel was the most frequent allergen in 30 studies and was among the 10 most common in 35 studies of suspected ACD patients.1-35 Most studies tested nickel at 5.0% but others tested it at 2.5%,21,30,32 which can interfere in the allergen's sensitization frequency.

The second most frequent allergen in this study was thimerosal, with a sensitization frequency of 18.4%, in line with the literature (0.9-37.6%).23,32 This relatively high frequency can be explained by thimerosal-containing vaccines.42,43 The current clinical relevance of these positive tests was null in this study. Thimerosal was the most common substance in 4 studies, placed among the 10 most frequent allergens in 29 studies, among 35 studies in selected samples.1-34 It was deemed clinically irrelevant in most of these studies. Thimerosal test concentration varied in some studies: in most, it was 0.1%, while in others it was 1.0% and 0.05%, which might have affected the allergen's sensitization frequency variation.3,15,17,23,31,32

The third most frequent allergen in this study was tosylamide formaldehyde resin with a contact sensitization frequency of 6.8%, in line with some studies where the frequency was 0.0%, 0.8%, 3.8%, 4.8% and 12.0%.2,15,21,22,31 Its clinical relevance was 100.0% in this study, showing this test's importance when there is suspected ACD, especially in the eyelids and periorbital region lesions. This can be explained by the frequent use of nail polish by adolescents. Tosylamide formaldehyde resin was placed among the eight most common allergens in two Brazilian studies, but it was tested only in some of the studies published between 1997 and May 2012.2,15,21,22,31

Neomycin was the fourth most common allergen in this study, with a frequency of 6.4%, consonant with the literature. It was the most common allergen in one study12 and was placed among the 10 most frequent allergens in 19 studies, with a frequency variation of 2.6-16.3%.1,2,5,8,11,12,16,18,20-24,26,29,31,33-35 Interestingly, in this study, positive tests for neomycin only occurred concomitantly with other substances and its current clinical relevance was null, perhaps due to the sensitization passed on to the neomycin present in topical medications (pure or associated with corticosteroids) used to treat the eczema provoking dermatological consultation, as well as in vaccines.42

Cobalt was the fifth most frequent allergen in this study, with a frequency of 4.0%. Its clinical relevance was difficult to establish as it had no positivity alone, suggesting co-reaction with metals, as described in other studies.44 There were reports in the literature of positive reactions to cobalt together with nickel in 68.0% and 71.0% of cases.16,22 Pure sensitization to cobalt was uncommon.1,15

Fragrance mix and Myroxylon pereirae were among the 10 most common allergens in this study, with frequencies of 4.0% and 1.6% and clinical relevance of 40.0% and 100.0%, respectively. These findings can be explained by the use of personal hygiene products and perfumed cosmetics and fragrances, among the age groups concerned. In the literature, fragrance mix and Myroxylon pereirae were among the 10 most frequent allergens in 29 and 12 studies, respectively.1-35

Several positive and relevant tests were related to allergen sources, as previously described, though data were incomplete, probably because of errors in the notes from patients' medical records and the non-confirmation of these sources due to a lack of patient follow-up.

Regarding the number of substances tested and frequencies for positive tests, the percentage of patients with positive tests increased when the patch test was performed with 40 substances instead of 30 (38.5% versus 74.0%). This may be a coincidence as it cannot be justified by the number (only 6) of positive reactions from the Cosmetics Series.

Since there were only six positive reactions to the test with the Brazilian Cosmetics Series in the two age groups studied, and given that 6.8% of these positive tests concerned tosylamide formaldehyde resin, this substance can be considered more important than the other substances in this series, for the purposes of evaluating the necessary screening in patients.

Given the high proportion of positive and relevant tests with reaction intensity 1+ (48/57; 84.2%), tests with intensity reaction 1+ were not excluded from the positive results of this study, although a recent study considered positive tests with intensity 1+ unreliable when compared in two tests, with an interval of 12-60 months in 49 patients.45

In this study, although no significant differences emerged regarding atopic and non-atopic sensitization, among the 32 relevant positive tests for patients who had personal atopic histories, 20 had relevant positive tests for nickel, linked to jewelry, metal accessories in clothing and footwear, etc., suggesting that children and adolescents with atopic histories should avoid contact with metal.

With respect to occupation, most patients were students and their relevant positive tests were for nickel. Some patients' positive tests were attributable to their activities (masons, hairdressers, manicurists, for instance).

In patients with positive tests, the body areas most frequently affected by dermatitis were the head and trunk. There was a significant difference regarding dermatitis location in the thighs of patients with positive tests, with higher positivity in children's thighs than other areas (p=0.0068). In similar studies in children and adolescents with suspected ACD, the main locations were as follows: the trunk,2,4,12,23 followed by the face,2,4,12 hands,4,12,14 feet4,12,14 and generalized dermatitis4,12,23 This study involved 28 patients who had 4 or more affected areas. In another study of tested children and adults presenting generalized dermatitis caused by suspected ACD, the most common allergens came from personal use items and cosmetics (fragrances, propylene glycol and preservatives).37

In cases where the initial dermatitis locations were the neck and trunk, the frequency of relevant positive tests was high, followed by the thighs/legs and face, especially the eyelids/ periorbital region. Most of the relevant positive tests for patients presenting dermatitis on the neck, trunk and face as initial locations, were due to nickel. In the eyelids and periorbital regions, nickel and tosylamide formaldehyde resin were especially prevalent. Other studies found that the initial dermatitis location did not correspond to any specific allergen.14,16

CONCLUSION

In our study, the rates for contact sensitization (59.2%) and the clinical relevance of positive tests (77.0%) in children and adolescents indicate that contact sensitization and ACD are not uncommon in these age groups.

The most frequent allergens were nickel, thimerosal, tosylamide formaldehyde resin, neomycin, cobalt, fragrance mix I. There was a higher frequency of positive tests among adolescents and females. Furthermore, there was no relevant statistical difference regarding contact sensitization among patients with or without atopic history. However, there was a significant difference between the two age groups studied concerning sensitization to nickel and thimerosal, as adolescents were more affected.

Nickel and fragrances were the only positive (and relevant) allergens in children, while nickel and tosylamide formaldehyde resin were the most frequent and relevant allergens among adolescents.

The study's findings suggest that children and adolescents should avoid contact with metals, fragrances and nail cosmetics, in particular.

Follow-up of tested patients is necessary to verify effectively the likely sources of allergens and the clinical relevance of positive tests.

A multicenter study of children and adolescents in Brazil is recommended in order to better assess this issue.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Financial Support: None.

How to cite this article: Rodrigues DF, Goulart EMA. Patch test results in children and adolescents. Study from the Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Dermatology Clinic, Brazil, from 2003 to 2010. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):671-83.

Work performed at the Outpatient Center of the Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Dermatology Clinic – Belo Horizonte (MG), Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goon AT, Goh CL. Patch testing of Singapore children and adolescents: our experience over 18 years. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:117–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manzini BM, Ferdani G, Simonetti V, Donini M, Seidenari S. Contact sensitization in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:12–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasch J, Geier J. Patch test results in schoolchildren. Results from the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) and the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group (DKG) Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández Vozmediano JM, Armario Hita JC. Allergic contact dermatitis in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah M, Lewis FM, Gawkrodger DJ. Patch testing in children and adolescents: five years' experience and follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:964–968. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romaguera C, Vilaplana J. Contact dermatitis in children: 6 years' experience (1992-1997) Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:277–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis VJ, Statham BN, Chowdhury MM. Allergic contact dermatitis in 191 consecutively patch tested children. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:155–156. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.0426i.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onder M, Adisen E. Patch test results in a Turkish paediatric population. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:63–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milingou M, Tagka A, Armenaka M, Kimpouri K, Kouimintzis D, Katsarou A. Patch tests in children: a review of 13 years of experience in comparison with previous data. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:255–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuljanac I, Kneževic E, Cvitanovic H. Epicutaneous patch test results in children and adults with allergic contact dermatitis in Karlovac county: a retrospective survey. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011;19:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roul S, Ducombs G, Taieb A. Usefulness of the European standard series for patch testing in children. A 3-year single-centre study of 337 patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:232–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidenari S, Giusti F, Pepe P, Mantovani L. Contact sensitization in 1094 children undergoing patch testing over a 7-year period. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heine G, Schnuch A, Uter W, Worm M. Frequency of contact allergy in German children and adolescents patch tested between 1995 and 2002: results from the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology and the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:111–117. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton TH, Wilkinson SM, Rawcliffe C, Pollock B, Clark SM. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: should pattern of dermatitis determine referral? A retrospective study of 500 children tested between 1995 and 2004 in one U.K. centre. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:114–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarte I, Lazzarini R, Kobata CM. Contact Dermatitis in Adolescents. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:200–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogeling M, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: the Ottawa Hospital patchtesting clinic experience, 1996 to 2006. Dermatitis. 2008;19:86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wöhrl S, Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, Jarisch R. Patch testing in children, adults, and the elderly: influence of age and sex on sensitization patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:119–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giordano-Labadie F, Rancé F, Pellegrin F, Bazex J, Dutau G, Schwarze HP. Frequency of contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis: results of a prospective study of 137 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beattie PE, Green C, Lowe G, Lewis-Jones MS. Which children should we patch test? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammonds LM, Hall VC, Yiannias JA. Allergic contact dermatitis in 136 children patch tested between 2000 and 2006. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:271–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zug KA, McGinley-Smith D, Warshaw EM, Taylor JS, Rietschel RL, Maibach HI, et al. Contact allergy in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2004. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1329–1336. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.10.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob SE, Brod B, Crawford GH. Clinically relevant patch test reactions in children-a United States based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:520–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belloni Fortina A, Romano I, Peserico A, Eichenfield LF. Contact sensitization in very young children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moustafa M, Holden CR, Athavale P, Cork MJ, Messenger AG, Gawkrodger DJ. Patch testing is a useful investigation in children with eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:208–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Waard-van der Spek FB, Oranje AP. Patch tests in children with suspected allergic contact dermatitis: a prospective study and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2009;218:119–125. doi: 10.1159/000165629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob SE, Yang A, Herro E, Zhang C. Contact allergens in a pediatric population: association with atopic dermatitis and comparison with other north american referral centers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:29–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoskute L, Dubakiene R, Tamosiunas V. Allergic contact dermatitis and patch testing in children. Acta Med Litu. 2005;12:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belhadjali H, Mohamed M, Youssef M, Mandhouj S, Chakroun M, Zili J. Contact sensitization in atopic dermatitis: results of a prospective study of 89 cases in Tunisia. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:188–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarma N, Ghosh S. Clinico-allergological pattern of allergic contact dermatitis among 70 Indian children. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:38–44. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.58677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Czarnobilska E, Obtulowicz K, Dyga W, Wsolek-Wnek K, Spiewak R. Contact hypersensitivity and allergic contact dermatitis among school children and teenagers with eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:264–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobata CM. Patch tests in children with eczema. São Paulo, SP: Universidade de São Paulo; 2010. pp. 79p–79p. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarnobilska E, Obtulowicz K, Dyga W, Spiewak R. The most important contact sensitizers in Polish children and adolescents with atopy and chronic recurrent eczema as detected with the extended European Baseline Series. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:252–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacob SE, Herro EM, Sullivan K, Matiz C, Eichenfield L, Hamann C. Safety and efficacy evaluation of TRUE TEST panels 1.11, 2.1, and 3.1 in children and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2011;22:204–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herro EM, Matiz C, Sullivan K, Hamann C, Jacob SE. Frequency of contact allergens in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:39–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Tessari G, Peroni A, Sabbadini C, Girolomoni G. Allergic contact dermatitis in children with and without atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23:275–280. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e318273a3e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiewak R. Patch testing for contact allergy and allergic contact dermatitis. Open Allergy J. 2008;1:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zug KA, Rietschel RL, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV, Taylor JS, Maibach HI, et al. The value of patch testing patients with a scattered generalized distribution of dermatitis: retrospective cross-sectional analyses of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001 to 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Engkilde K, Menné T, Johansen JD. Contact sensitization to common haptens is associated with atopic dermatitis: new insight. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:1255–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, Andersen KE. Nickel sensitization in adolescents and association with ear piercing, use of dental braces and hand eczema. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:359–364. doi: 10.1080/000155502320624096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandão MH, Gontijo B, Girundi MA, de Castro MC. Ear piercing as a risk factor for contact allergy to nickel. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;86:149–154. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fors R, Persson M, Bergström E, Stenlund H, Stymne B, Stenberg B. Lifestyle and Nickel Allergy in a Swedish Adolescent Population: Effects of Piercing, Tattooing and Orthodontic Appliances. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:664–668. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidary N, Cohen DE. Hypersensitivity reactions to vaccine components. Dermatitis. 2005;16:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suneja T, Belsito DV. Thimerosal in the detection of clinically relevant allergic contact reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:23–27. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lisi P, Brunelli L, Stingeni L. Co-sensitivity between cobalt and other transition metals. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:172–173. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2003.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duarte I, Silva Mde F, Malvestiti AA, Machado Bde A, Lazzarini R. Evaluation of the permanence of skin sensitization to allergens in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:833–837. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]