Abstract

Enteral feeding is the preferred method of nutritional therapy. Mucosal lack of contact with nutrients leads do lymphoid tissue atrophy, immune system functional decline, and intensification in bacterial translocation. Currently, it is assumed that microbiome is one of the body organs that has a significant impact on health. The composition of microbiome is not affected by age, sex, or place of residence, although it changes rapidly after diet modification. The composition of the microbiome is determined by enterotype, which is specific for each organism. It has a significant impact on the risk of diabetes, cancer, atherosclerosis, and other diseases. This review gathers data on interaction between gut-associated lymphoid tissue, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, microbiome, and the intestinal mucosal barrier. Usually, the information on the aforementioned is scattered in specialist-subject magazines such as gastroenterology, microbiology, genetics, biochemistry, and others.

Keywords: enteral feeding, intestinal immune function

Introduction

The introduction of Parenteral Nutrition into clinical practice in the United States in the 1960s was a giant step forward in the development of nutritional therapy. It took many years to prove that enteral nutrition (EN) causes fewer complications, is cheaper, and is as effective as parenteral nutrition (PN).

Clinical practice often entails situations in which the underlying disease and its complications interfere with nutrient absorption and intestinal peristalsis. Persistence of these disorders leads to malnutrition, impaired immunological response, and many other negative effects. These are the reasons why patients with intestinal failure require the implementation of EN, PN, or concomitant use of both methods of nutrition therapy.

The condition for the maintenance of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in the state of full efficiency is the use of EN, because the mucosal lack of contact with nutrients and inhabiting microbiome inhibits the development of neonatal GALT and in mature individuals causes its atrophy.

This review gathers data on the mechanisms that influence the effectiveness of nutritional therapy in order to facilitate rational planning and its implementation individually adapted to the needs and condition of each patient.

Microbiome

GI mucosa is in permanent contact with the microbiota and its genome, which together is called the microbiome. The composition of the microbiome in humans is different. For this reason there are enterotypes, which are named after the dominant type of bacteria. Based on this principle, there are the following enterotypes: Bacteroides, Prevotella and Ruminococcus, and others. Diet affects changes in enterotype, but age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) do not. Wu et al. proved that a change in diet from high-fat to low-fibre and from low-fat to high-fibre changes the microbiome within 24 h and the enterotype after a longer period of time [1].

A landmark step towards the knowledge of the relationship between the host and the microbiota is the research conducted since 2007 as part of the Human Microbiome Project (HMP). At this stage, they rely on the analysis of 16S rRNA gene microbiota. Comparison of the nucleotide sequence in a particular gene with data stored in the HMP enables microorganism identification without the need for bacterial culture. DNA analysis provides more information than RNA analysis because 80% of the gene encodes a protein. Moreover, it determines the type of microorganism and its phenotype.

The initial colonisation of the mucous membranes occurs during childbirth – this is why the composition of the microbiome of infants born from caesarean section is different than the ones born from natural childbirth [2]. Neonatal nutrition determines their immune profile and susceptibility to diseases in adulthood [3]. The composition of the child microbiome is already set at the age of 1 year and is basically unchanged for the rest of its life [4].

The development of surgical techniques and transplantology has made intestine transplantation possible. A fistula created during these operations to graft control allows the determination of changes in the composition of the microbiome caused by an anaerobic environment change into the oxygen environment. Hartman et al. noted that oxygen supply to the gut through the fistula vitally reduces the ratio of anaerobic bacteria to aerobic, and the closure of the fistula restores the original microbiome composition [5]. Drugs such as antibiotics and chemotherapy also affect changes in the microbiome composition. Chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukaemia causes a 100-fold decrease in the total number of bacteria. This is a result of the 10,000-fold decrease in the number of anaerobic bacteria and 100-fold increase in the number of streptococci [6]. Zwielehner et al. showed a decrease in the number of enteral bacteria after one chemotherapy course and a restoration to baseline after a few days of its completion [7]. Benus et al. observed a change in the number of certain bacteria strains and a ten-fold quantity increase of short chain fatty acid (SCFA) synthesis due to consuming a fibre-rich diet for 2 weeks [8].

A beneficial effect of synbiotics on health was the stimulus for the development of research on microbiome and its interactive relation with its host. Their findings led to attempts at faeces transplantation, an organ treated as obtained from a healthy individual, transplanted to a patient [9, 10]. The idea of this original method of therapy was the change the microbiome together with its microenvironment, instead of changing single strains of probiotic bacteria.

Colitis is a common complication of antibiotic treatment caused by Clostridium difficile. Unfortunately, the sole withdrawal of the antibiotic and administration of the vancomycin with metronidazole is not as effective as a graft stool collected from a healthy donor. The change in the microbiome by a faecal transplantation improves the efficiency of the immune system, and increases the effectiveness of Clostridium difficile elimination and lowers the risk of reinfection [11]. Although the faecal transplantation is an effective method of treatment for Clostridium difficile infection, it is a rather unappealing technique. It exposes the patient to complications such as perforation, bleeding, bacteria translocation, sepsis, and septic shock. Furthermore, it was found that stool collected from donors with type 1 diabetes, and breast or liver cancer markedly increases the risk of developing these diseases in transplant recipients [12, 13].

Intestinal mucosal barrier

Mucosa protects the organism very efficiently against invasion of pathogens and harmful dietary elements. Moreover, they are involved in the excretion of metabolic products and communication between the enteric nervous system (ENS), GALT, and microbiome. The apical junctional complex (AJC) is located between the epithelial cells covering the intestinal mucous membranes. It is formed of specific construction protein complexes and functions differently. These include tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions (AJs), and desmosomes located on the top of the side surface of epithelial cells. They mediate in the substance exchange between the organism and the environment. It is estimated that approximately 85% of dietary components penetrate epithelium by diffusion and the remaining 15% by transcytosis. Diffusion loses its selective character in the course of viral, bacterial, and inflammatory bowel disease [14]. TJs and AJs permeability is highly selective due claudin, which barrier properties support occludin and immunoglobulins [15] (Figure 1).

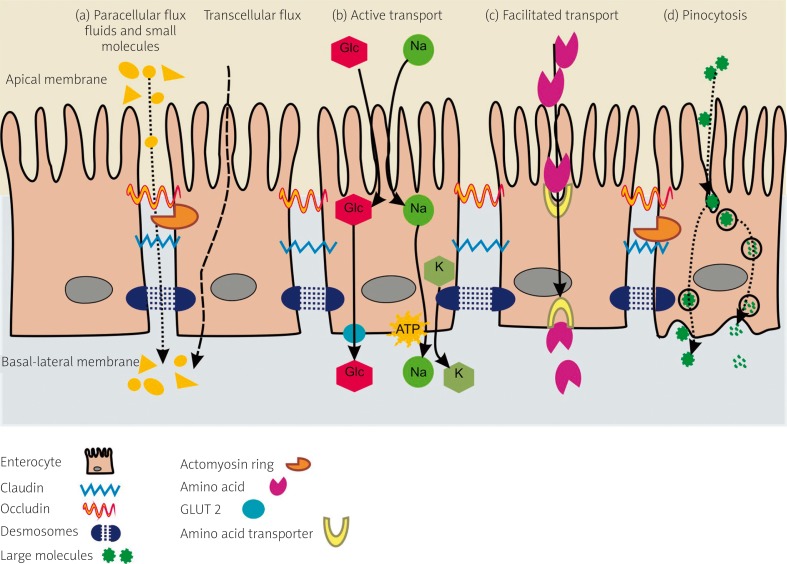

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of nutrient absorption. Nutrients are absorbed into enterocytes by diffusion through paracellular flux, and through transcellular flux by active transport, facilitated transport, and by pinocytosis. (a) Some substances, such as water and small molecules, cross membranes feely. (b) Active transport requires energy expenditure. The energy is supplied by ATP and Na+/K+ pump. (c) Other compounds cannot cross cell membranes without a specific carrier, which affects the permeability of the membrane. Facilitated diffusion, like simple diffusion, allows on equalisation of the substance on both sides of the membrane. (d) Some large molecules are moved into the cell via engulfment of the cell membrane

The functions of these proteins are modulated by growth factors (EGF, HGF, VEGF, FGF, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)), cytokines, hormones, and certain drugs [16, 17].

In patients with protective ileostomy, mucosal lack of contact with the ingest leads to atrophy, and the absorption and motility of the distal intestine decreases [18]. The closure of the fistula restores intestinal passage to the original state after 6 months on average [19]. Williams et al. showed that 34 weeks after creating protective ileostomy, the force of contraction and quiescent voltage decreased significantly in the distal loop. The index of villous atrophy decreased twice, although the depth of the intestinal crypts did not change [20]. Brinkman et al. analysed the impact of TPN, EN, and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2), administered in various combinations, on weight gain and regeneration of the mucosa in patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS) [21]. It appeared that after massive intestinal resection the adaptation to the new conditions of the rest of the small intestine occurred solely in the group receiving EN and GLP-2 simultaneously.

The increase in permeability of the intestinal mucosal barrier, called leaky gut syndrome, often occurs in the course of inflammatory bowel disease [22]. It has been proven that, contrary to widespread opinion, oral administration of fluids to patients not only protects from fluid loss, but allows for reduction in the volume of infusion [23].

Mucositis occurs in about 40% of patients receiving standard chemotherapy and in 100% of patients after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation receiving high doses of chemotherapy. Keefe et al. found that the chemotherapy combined with autologous stem cell transplantation increases the apoptosis of epithelial cells sevenfold, resulting in a 25% reduction in the area of the intestinal villi after one day [24]. The Mucositis Study Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) recommends the oral administration of palifermin, a humanised recombinant keratinocyte growth factor (rHuKGF), before each cycle of chemotherapy due to oral cancers. It causes proliferative capacity recovery of intestinal epithelial cells, reduced apoptosis rate and a reduction in the number of inflammatory cytokines synthesised [25].

Acute radiation toxicity (ART) includes diarrhoea and abdominal pain. The pathophysiology includes enterocytes apoptosis, mucosal barrier injury, and dysbiosis. Diabetes, hypertension, and atherosclerosis reduce visceral blood flow and, therefore, increase the risk of radiation enteritis [26]. Chronic radiation syndrome symptoms appear 6–12 months after radiotherapy, or even later. The pathophysiology includes intestinal wall fibrosis and blood vessels damage by radicals formed by the photons of radioactive energy. They interfere with the stability of the genome, causing DNA strand breakage and increase in the synthesis of TGF-β [27, 28]. As a result of fibrosis the intestinal motility weakens and Auerbach's plexus neurons undergo a compensatory hypertrophy. Due to anal sphincter muscle fibrosis, 1/5 of patients after radiotherapy suffer faecal incontinence [29] (Table I).

Table I.

Features of acute and chronic radiation toxicity

| Parameter | Acute radiation toxicity | Chronic radiation toxicity |

|---|---|---|

| Effects | Cells with high proliferation rate (stem cells, Paneth cells, enteroendocrine cells, etc.) | Mostly fibroblasts |

| Pathogenesis | Inhibition of stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Intensification of apoptosis and intestinal epithelial stem cell impairment | Fibroblast stimulation to proliferation and accumulation in the submucosa. Submucosal fibrosis is related to increase of collagen synthesis. Increase in secretion of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β1), and cytokines. Mesenteric thrombosis and vasculitis leads to intestinal ischaemia |

| Time since start of radiotherapy to onset of symptoms | 2–4 weeks | Months – years |

| Symptoms and complications | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, water and electrolyte disturbances, mucositis, dysbiosis | Ileus, fistulas, bleeding, ulceration, perforations |

| Treatment | Conservative | Mainly surgical |

| Disease course | Acute – resolves spontaneously after radiotherapy | Chronic, irreversible. Natural mechanisms are not able to repair the damage |

A treatment method of radiation-induced fibrosis has not yet been developed, but its effects can be reduced by administering pentoxifylline with high doses of vitamin E [30]. The combined administration of the two antioxidants may partially reverse the fibrosis. Attempts at radiation-induced fibrosis treatment with anti-TGF, anti-platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and statins are promising for the future [31].

The intestinal immune system

Toll-like receptors are located on the apical surface of the intestinal epithelium. They collect pathogen-associated molecular patterns and transfer them to antigen-presenting cells. On the basis of obtained information, GALT differentiates commensal bacteria from pathogenic and either tolerates or destroys them. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue is composed of lymphoid aggregates, Peyer's patches, isolated lymphoid follicles diffusely distributed along the lamina propria, and intraepithelial lymphocytes. It is estimated that GALT contains approximately 70% of total immune system cells. Malnutrition and chronic inflammatory bowel disease cause lymphocyte apoptosis and inhibition of thymocyte proliferation [32]. The fact that the thymus regenerates and cellular immunity normalises as nutritional status improves shows that those reactions are reversible [33]. As well as recognition and neutralisation of harmful antigens, GALT is responsible for oral tolerance, which in essence is the lack of hypersensitivity reactions to harmless food and bacterial antigens [34]. Dendritic cells (DC) play an important role in forming the oral tolerance. It migrates from lamina propria to GALT and transmits the information to regulatory lymphocytes (Treg) on the emergence of a specific antigen. The essence of tolerance is the elimination of the antigen by sensitised lymphocytes via clonal anergy, clonal deletion, sequestration, antigen ignorance, or preventing lymphocytes from contact with the antigen [35].

Dendritic cells identifies antigens collected from the intestinal lumen or from the M cells. Then DC migrates to the mesenteric lymph nodes, where antigens are processed and presented to effector lymphocytes. Besides DC, M cells (microfold cells) are involved in the antigen transport. M cells are mostly localised close to follicle-associated epithelium. M cells, like DC, migrate and present antigens to lymphocytes, although their main function is transcytosis [36]. M cells are able to carry (apart from antigens) bacteria, viruses, and other particles into the subepithelial space without changing their morphology or features. This feature is used by a few microorganisms to invade the organism. This specific feature of M cells is the reason for their use as a means of transport for some vaccines and drugs into the organism. Its advantage is the ability of drugs and vaccines to be administered in an oral, non-invasive, safe way and at low-cost (Table II).

Table II.

Characteristics of intestinal mucosal cells

| Cell type | Function | Specific products |

|---|---|---|

| Dendritic cells | Antigen absorption from the intestinal lumen and mucosal lamina propria. Antigen-presenting cell. Cell maturation after contact with antigen and migration to lymph nodes and spleen | IL-12, IFN-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-15 |

| Paneth cells | Innate, non-specific immunity. Substance synthesis that coats and disables pathogens and diet antigens. Impact on the maintenance of intestinal microbiota. Stem cell protection | α-Defensin-5 HD5 and HD6, secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) |

| Stem cells | Differentiate into intestinal epithelial cells | |

| M (microfold) cells | Macromolecules transcytosis (pathogens, commensal microorganisms, and antigens) from intestinal lumen to submucosa | |

| Enteroendocrine cells | Hormones synthesis and secretion | 5-HT, somatostatin, peptide YY, GLP-1, glicentine, oxyntomoduline, glucose-dependent insulinotropic hormone (GIP) |

| Goblet cells | Innate immunity component. Secreted mucus is the first line of defence against pathogens | Mucin 2, trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) and resistin-like molecule β (Relmβ) |

| Enterocytes | Nutrients absorption. Induction of immune tolerance of protein intake. Induction of oral tolerance contributes to the formation of the microenvironment. Maintaining balance between antigen tolerance and inflammation | |

| B Cells | Antigen-presenting cell via Toll-like receptor, homing to lymph nodes and conversion to plasmocytes, which return intestinal mucosa and produce antibodies | IgA, IgM |

| Macrophages | The first phagocytic cells of innate immunity that microorganisms come into contact with after passing through the intestinal epithelium. Phagocytosis, bactericidal, and bacteriostatic properties without inducing an inflammatory reaction | IL-10, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen intermediates, cathepsins and metalloproteases |

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue defence functions support the innate immune components, such as low gastric pH, bile acids, mucus, lysozyme, and defensins. A secretory immunoglobin A2 (sIgA) is the first line of immune defence of the organism against harmful agents. The contact of B cells with antigen triggers the synthesis of sIgA. Sensitised B cells proliferate and differentiate into plasmocytes. This process is coordinated by T helper cells, TGF-β, and IL-10. SIgA is secreted by plasma cells as a dimer, which, after binding to the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR), is transmitted via transcytosis by the M cells to mucosal surfaces [37]. SIgA causes agglutination and inhibits bacterial adhesion to epithelium. It absorbs antigens and deactivates viruses, toxins, and enzymes produced by microorganisms. As SIgA is resistant to proteolytic enzymes, as much as 40% of anaerobic bacteria excreted with the faeces is covered with it. SIgA, unlike other immunoglobulins, does not activate, complement, or cause the inflammatory response due to contact with an antigen. This phenomenon is called an “immune exclusion” (Figure 2).

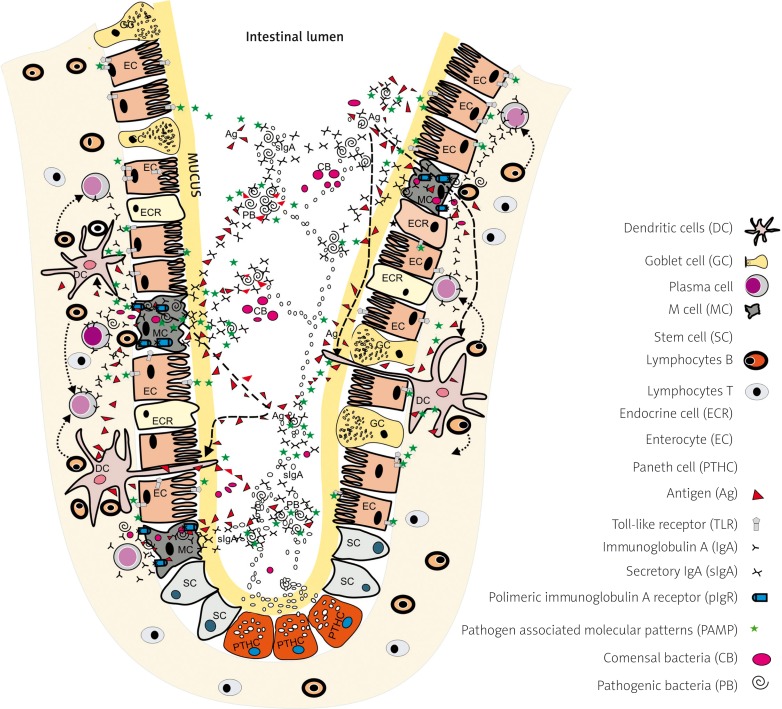

Figure 2.

The mechanisms of human immune defence system against pathogen invasion through the intestinal mucosa. (a) The antigens penetrate from the intestinal lumen into the epithelium via M-cell transcytosis, or are transported by dendritic cell veils (DC). Dendritic cell and B cells are activated by antigens and migrate to lymph nodes. In lymph nodes, B cells convert to plasmocytes. Dendritic cell matures, which results in their loss of the ability to present antigens. Plasmocytes and mature DC return to intestinal mucosa lamina propria, where they start to secrete immunoglobin A and many inflammatory cytokines. IgA is polymerised and then combined with the polymeric immunoglobulin A receptor (pIgR). These complexes are transferred through transcytosis. When sIgA reaches the apical cell side it is secreted into intestinal lumen, where it binds to the pathogens. (b) Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) bind to pattern recognition receptors (PRR), which include Toll-like receptors (mainly in the intestine: TLR3, 4 and 5) and Nod-like receptors. These complexes trigger a cascade reaction that leads to NF-κB activation and transport to the nucleus, as well as increased expression of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines. Toll-like receptors (TLR) are expressed mostly on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APC) – dendritic cells, macrophages, and B cells. Regulatory T cells, the main function of which is to maintain tolerance to self-antigens, also express TLR. (c) Paneth cells, located in the mucosa, synthesise and secrete antimicrobial peptides into the lumen. They present antibacterial, antiviral, as well as antifungal and anti-parasitic activity. These include α human defensins 5 and 6 (HD5, 6) and human β-defensin 1-3 (HBD1-3). The mechanism of their antimicrobial activity involves binding defensins to the targeted cell membrane followed by endocytosis and the triggering of metabolic processes that lead to cell apoptosis

Conclusions

Although the introduction of PN into medical practice has allowed many patients to return to an active lifestyle, it deprives the organism of the many benefits resulting from EN. For this reason, decision-making on the implementation of PN requires consideration of the possibility of administration, at least partially, of EN.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azad MB, Konya T, Maughan H, et al. Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ. 2013;185:385–94. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauta AJ, Ben Amor K, Knol J, et al. Relevance of pre- and postnatal nutrition to development and interplay between the microbiota and metabolic and immune systems. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:586S–93S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.039644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouhy F, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, et al. Composition of the early intestinal microbiota: knowledge, knowledge gaps and the use of high-throughput sequencing to address these gaps. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:203–20. doi: 10.4161/gmic.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman AL, Lough DM, Barupal DK, et al. Human gut microbiome adopts an alternative state following small bowel transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17187–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904847106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Vliet MJ, Tissing WJ, Dun CA, et al. Chemotherapy treatment in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving antimicrobial prophylaxis leads to a relative increase of colonization with potentially pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:262–70. doi: 10.1086/599346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwielehner J, Lassl C, Hippe B, et al. Changes in human fecal microbiota due to chemotherapy analyzed by TaqMan-PCR, 454 sequencing and PCR-DGGE fingerprinting. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benus RF, van der Werf TS, Welling GW, et al. Association between Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and dietary fibre in colonic fermentation in healthy human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:693–700. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grehan MJ, Borody TJ, Leis SM, et al. Durable alteration of the colonic microbiota by the administration of donor fecal flora. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:551–61. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e5d06b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly CR, de Leon L, Jasutkar N. Fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in 26 patients: methodology and results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:145–9. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318234570b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, et al. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1079–87. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapira I, Sultan K, Lee A, Taioli E. Evolving concepts: how diet and the intestinal microbiome act as modulators of breast malignancy. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:693920. doi: 10.1155/2013/693920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebnet K. Organization of multiprotein complexes at cell-cell junctions. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne CB, Vanhook MK, Gambling TM, et al. Regulation of airway tight junctions by proinflammatory cytokines. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3218–34. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng S, Adelman RA, Rizzolo LJ. Minimal effects of VEGF and anti-VEGF drugs on the permeability or selectivity of RPE tight junctions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3216–25. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miedema BW, Karlstrom L, Hanson RB, et al. Absorption and motility of the bypassed human ileum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:829–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02051917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallgren T, Oresland T, Cantor P, et al. Intestinal intraluminal continuity is a prerequisite for the distal bowel motility response to feeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:554–61. doi: 10.3109/00365529509089789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams L, Armstrong MJ, Finan P, et al. The effect of faecal diversion on human ileum. Gut. 2007;56:796–801. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.102046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkman AS, Murali SG, Hitt S, et al. Enteral nutrients potentiate glucagon-like peptide-2 action and reduce dependence on parenteral nutrition in a rat model of human intestinal failure. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G610–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42:71–8. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diggins KC. Treatment of mild to moderate dehydration in children with oral rehydration therapy. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:402–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keefe DM, Brealey J, Goland GJ, Cummins AG. Chemotherapy for cancer causes apoptosis that precedes hypoplasia in crypts of the small intestine in humans. Gut. 2000;47:632–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu J, Chang Z, Peng B, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor/fibroblast growth factor-7-regulated cell migration and invasion through activation of NF-kappaB transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6001–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrakis N, Athanassiou E, Vamvakopoulou D, et al. Practical approaches to effective management of intestinal radiation injury: benefit of resectional surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4013–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin S. Role of p53 in anticancer drug treatment- and radiation-induced injury in normal small intestine. Cancer Biol Med. 2012;9:1–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horiguchi M, Ota M, Rifkin DB. Matrix control of transforming growth factor-beta function. J Biochem. 2012;152:321–9. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varma JS, Smith AN, Busuttil A. Function of the anal sphincters after chronic radiation injury. Gut. 1986;27:528–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.5.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan S, Salib O, O'Shea C, Moriarty M. A randomized prospective study of extended tocopherol and pentoxifylline therapy, in addition to carbogen, in the treatment of radiation late effects. Ecancermedicalscience. 2008;2:81. doi: 10.3332/eCMS.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamama S, Delanian S, Monceau V, Vozenin MC. Therapeutic management of intestinal fibrosis induced by radiation therapy: from molecular profiling to new intervention strategies et vice et versa. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5(Suppl.1):S13. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savino W, Dardenne M, Velloso LA, Dayse Silva-Barbosa S. The thymus is a common target in malnutrition and infection. Br J Nutr. 2007;98(Suppl.1):S11–6. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507832880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chevalier P, Sevilla R, Zalles L, et al. Immuno-nutritional recovery of children with severe malnutrition [French] Sante. 1996;6:201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner HL, da Cunha AP, Quintana F, Wu H. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:241–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewkowicz N, Klink M, Mycko MP, Lewkowicz P. Neutrophil-CD4 + CD25+ T regulatory cell interactions: a possible new mechanism of infectious tolerance. Immunobiology. 2013;218:455–64. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuma P, Hubbard AL. Transcytosis: crossing cellular barriers. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:871–932. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corthesy B. Role of secretory IgA in infection and maintenance of homeostasis. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:661–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]