Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Colonoscopy is the most commonly used colorectal cancer screening test in the United States. Its quality, as measured by adenoma detection rates, varies widely between physicians with unknown consequences for the cost and benefits of screening programs.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate the lifetime benefits, complications and costs of a colonoscopy screening program at different levels of adenoma detection.

DESIGN, SETTING and PARTICIPANTS

This study used microsimulation modeling with data from a community-based healthcare system on adenoma detection rate variation and cancer risk among 136 physicians and 57,588 patients for 1998–2010.

EXPOSURE

Using modeling, no screening was compared to screening initiation with colonoscopy according to adenoma detection rate quintiles (averages 15.3, 21.3, 25.6, 30.9, and 38.7%) at ages 50, 60 and 70 with appropriate surveillance of adenoma patients.

MAIN OUTCOMES

Estimated lifetime colorectal cancer incidence, mortality, number of colonoscopies, complications and costs per 1,000 patients, all discounted at 3% per year and including 95% confidence intervals from multiway probabilistic sensitivity analysis (95%CI).

RESULTS

In simulation modeling, among unscreened patients, the lifetime risks of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality were 34.2 (95%CI:25.9–43.6) and 13.4 (95%CI:10.0–17.6) per 1,000, respectively. Among screened patients, simulated lifetime incidence decreased with lower to higher adenoma detection rates (quintile 1 versus 5: 26.6, 95%CI:20.0–34.3 versus 12.5, 95%CI:9.3–16.5) as did mortality (5.7, 95%CI:4.2–7.7 versus 2.3, 95%CI:1.7–3.1). Compared to quintile 1, simulated lifetime incidence and mortality were on average 11.4% (95%CI:10.3–11.9) and 12.8% (95%CI:11.1–13.7) lower, respectively, for every 5 percentage-point higher adenoma detection rate. Total colonoscopies and associated complications were higher from quintile 1 (2,777, 95%CI:2,626–2,943 and 6.0, 95%CI:4.0–8.5) to subsequent quintiles (quintile 5: 3,376, 95%CI:3,081–3,681 and 8.9, 95%CI:6.1–12.0). Estimated net screening costs were, however, lower from quintile 1 (US $2.1 million, 95%CI:1.8–2.4) to quintile 5 (US$1.8 million, 95%CI:1.3–2.3) due to averted cancer treatment costs. Results were stable across sensitivity analyses.

CONCLUSIONS-RELEVANCE

Using microsimulation modeling, we found that higher adenoma detection was associated with lower lifetime colorectal cancer incidence and mortality without higher overall costs. Future research is needed to assess if increasing adenoma detection would be associated with improved patient outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 Screening colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer mortality risk through detection and treatment of precursor adenomatous or early cancerous lesions,2–4 but its effectiveness depends upon exam quality.5–7 A currently recommended colonoscopy quality indicator, the adenoma detection rate (ADR), has been found to vary at least 3-fold across physicians.8–10 A recent large United States study found that this variation is associated with patient outcomes: compared to patients of physicians with the highest ADRs, patients of physicians with the lowest ADRs had a nearly 50% higher risk of colorectal cancer and a 60% higher risk of fatal disease during up to 10 years of follow-up after colonoscopy.10 This suggests that higher adenoma detection is associated with both disease detection and disease management. However, little is known about the consequences of different levels of ADR for the lifetime benefits, risks and cost in a program using colonoscopy as the initial and primary screening test in an average-risk population. Higher ADRs may accrue mostly from increased detection of small low-risk polyps, resulting in an increased number of subsequent surveillance colonoscopies and complications for polyps that may never cause fatal disease. Thus, any benefits of higher ADR may be outweighed by the corresponding harms.11

In the present study, we evaluated various outcomes for a colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening strategy according to different adenoma detection rate levels, including lifetime colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, the number of colonoscopies and related complications, and screening and treatment costs.

METHODS

We used microsimulation modeling of screening in a United States population cohort with community-based data on ADR variation and cancer risk. This study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) institutional review board, and conducted as part of the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded consortium Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR), which aims to conduct multi-site, coordinated, trans-disciplinary research to evaluate and improve cancer screening.

KPNC data

Physician-level (ADR) and patient-level (age, sex, race/ethnicity, cancer diagnosis) data were from KPNC, an integrated healthcare delivery system.10 The data for this study were confined to screening colonoscopies performed by 136 gastroenterologists between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2010. Outcomes were ascertained in the 6-month to 10-year period after initial colonoscopy through December 31, 2010. The screening indication excluded patients who had prior: adenomas or colorectal cancer; inflammatory bowel disease within 10 years; colonoscopy within 10 years, sigmoidoscopy within 5 years; positive fecal hemoglobin test within 1 year; or abdominal symptoms within 6 months. ADRs, the proportion of a physician’s screening colonoscopies that detect ≥1 histologically confirmed adenomas, ranged from 7.3% to 52.5%; the averages (and ranges) for ADR quintiles 1 through 5 were 15.32% (7.35–19.05%), 21.27% (19.06–23.85%), 25.61% (23.86–28.40%), 30.89% (28.41–33.50%) and 38.66% (33.51–52.51%), respectively.

Microsimulation model

The Microsimulation Screening Analysis-colon (MISCAN-colon) model is part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) sponsored by the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) and has informed United States Preventive Services Task Force screening recommendations.12 The model is described extensively in the eAppendix. In short, MISCAN-colon generates an average-risk screening population with similar life expectancy and risk of colorectal cancer as the United States population. It specifies, with individual variability, the risk of developing ≥1 colorectal neoplasia through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, and potential cancer-related reductions in life expectancy. Different scenarios can be evaluated. The modeled effectiveness of screening shows good concordance with observed interval cancer rates from trials of fecal occult blood tests and endoscopy (eFigure 4).13–16

Natural history of colorectal cancer

The MISCAN-colon model assumes that colorectal cancer develops progressively from small (≤5mm) through medium (6–9 mm) or large adenomas (≥10mm). An early stage tumor may progress to an advanced-stage tumor without symptoms, or become symptomatic during any stage and be clinically diagnosed. Some patients die of the disease and lose life-years, while others die from competing causes before or after developing cancer. Serrated adenomas are not modeled distinct from conventional adenomas.17 Adenoma prevalence and age-, stage- and location-specific incidence of CRC in the absence of screening utilized data from the era before screening became commonly used (Table 1, eAppendix). Age-, stage- and location-specific survival utilized cancer registry data on patients diagnosed in 2000–2003 with follow-up to 2010; mortality from competing causes was estimated from 2010 US lifetables.

Table 1.

Key modeling assumptions.

| Input parameter | Base-case assumption | PSA assumptiona | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | |||

| All-cause mortality | U.S. Lifetables | CDC 2010h | |

| Natural history | |||

| Adenoma onset | Age-dependent (non- homogeneous Poisson) | Unif(−20%+20%) | h |

| Adenoma progression | |||

| State transitions | Age-dependent | Unif(−10%+10%) | h |

| State duration, years (total) | Exp(λ=130) | λ~Unif(−10%+10%) | h |

| Cancer progression (preclinical) | |||

| Stage transitions | Age-dependent | Unif(−10%+10%) | h |

| Stage durations, years | Exp (λ=2.5) | λ~Unif(−10%+10%) | h |

| Colorectal cancer incidence (without exposure to screening) | Age-/Stage-/Location-dependent | SEER 1975–79h | |

| Colorectal cancer survival | Age-/Stage-/Location-dependent | SEER 2000–10h | |

| Colonoscopy quality | |||

| Sensitivity, % b | ADR quintile-dependent: | ||

| adenomas 0–5mm | 14.7-29.6-41.0-66.2-98 | Beta;SE:3.5 | h |

| adenomas 6–9mm | 39.6-65.8-85.0-94.3-98 | Beta;SE:3.5 | h,5 |

| adenomas ≥10mm | 88.0-92.2-95.0-96.8-98 | Beta;SE:2.5 | h,5 |

| malignant neoplasia | 98 | Beta;SE:2.5 | h |

| Specificity, % c | 85 | Beta;SE:5 | 36, 37 |

| Complete colonoscopy examination, % d | 98 | Beta;SE:2.5 | 38, 39 |

| Complication rates, % | |||

| with polypectomy | Age-dependent (50–100 years): | 19, 20 | |

| Serious GI complications | 0.2–2.9 | LogN;SE:10% | |

| Fatal complications | 0.0033 | LogN;SE:50% | |

| Other GI complications | 0.2–2.6 | LogN;SE:10% | |

| Cardiovascular complications | 0.1–2.5 | LogN;SE:10% | |

| without polypectomy e | - | ||

| Costs, US $ f | |||

| Colonoscopy | CMS 200721 | ||

| without polypectomy | 899 | LogN;SE:5% | |

| with polypectomy | 1,140–1,270 for ADR q1-5 | LogN;SE:5% | |

| Complication | 6,129 | CMS 200722 | |

| Per life-year with cancer care g | Stage-dependent (I–IV): | CMS 200723 | |

| Initial year, stage I–IV | 37,185–78,876 | LogN;SE:1.1–1.9% | |

| Ongoing, stage I–IV | 3,092–12,350 | LogN;SE:4.4–5.7% | |

| Terminal year, stage I–IV | 64,693–89,600 | LogN;SE:1.2–2.2% | |

| Terminal year, stage I–IV | 19,427–50,552 | LogN;SE:8.4–10% | |

Abbreviations: PSA= probabilistic sensitivity analysis; CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Poisson = Poisson distribution; Unif = uniform distribution; Exp = exponential distribution; SEER = Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program; ADR = adenoma detection rate; Beta = beta distribution; SE = standard error; GI = gastrointestinal; LogN = lognormal distribution; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In multiway probabilistic sensitivity analyses the model parameters were varied randomly according to Uniform, Beta or Lognormal distributions. To limit the degrees of freedom, several parameters were assumed to be perfectly correlated: sensitivity for small adenomas with sensitivity for medium adenomas, sensitivity for large adenomas with sensitivity for cancer, all complication types, costs of colonoscopy with and without polypectomy, and all treatment costs. Other parameters were varied independently.

Sensitivity was defined as the probability of detecting an adenoma that was present at the time of exam. Based on baseline-detection rates in our data, sensitivity for colorectal cancers was assumed to be unrelated to ADR.

The lack of specificity indicates how many of the exams that did not detect adenomatous lesions included polypectomy for non-adenomatous lesions.

Colonoscopy was considered complete if the cecum was reached. In the 2% incomplete examinations, the endpoint was assumed to be distributed uniformly over the colon/rectum.

We assumed that colonoscopy without polypectomy was not associated with a higher risk of complications. The risk of complications for polypectomy was assumed to increase exponentially with age. Serious GI events included perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding requiring blood transfusions; other GI events included paralytic ileus, nausea, vomiting and dehydration, abdominal pain; and cardiovascular events included myocardial infarction or angina, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, cardiac or respiratory arrest, or syncope, hypotension, or shock. The fatal perforation rate was derived from estimates of the incidence of perforation and case-fatality for perforation.19,20

Screen- and treatment costs include patient time costs (opportunity costs of spending time on screening or being treated for a complication or colorectal cancer), but do not include travel costs, costs of lost productivity, and unrelated health care and non-health care costs in added years of life. Patient time was valued at the median US wage in May 2013 ($16.87 per hour), and we assumed that colonoscopies involve 8 hours of patient time. Patient time costs were already included in the estimates for the costs of life-years with cancer care obtained from a study by Yabroff et al.23

Care for colorectal cancer was divided in three clinically relevant phases: the initial, continuing, and terminal care phase. The initial care phase was defined as the first 12 months after diagnosis; the terminal care phase was defined as the final 12 months of life; the continuing care phase was defined as all months in between. In the terminal care phase, we distinguished between cancer patients dying from the disease and cancer patients dying from another cause. For patients surviving less than 24 months, the final 12 months were allocated to the terminal care phase and the remaining months were allocated to the initial care phase.

More details regarding the calibrated natural history parameters and other model elements are provided in the eAppendix.

Performance characteristics of colonoscopy

The modeled effectiveness of colonoscopy screening depends on assumptions regarding its completeness and sensitivity for adenomatous lesions (Table 1). For this study, we used observed data from KPNC to derive sensitivities for colonoscopy at the five ADR quintiles, while assuming no underlying differences in adenoma prevalence.18

In a separate analysis, patient populations in each ADR quintile were simulated using the age distribution at screening (eMethods). We derived 5 different sets of parameters for per-lesion sensitivity by polyp size to reproduce the average ADR for each quintile. These were constrained by assuming: (1) sensitivity for cancer was 98% across all quintiles; (2) sensitivity for medium to large adenomas varied less than for small adenomas, and increased according to a fixed rule from the lowest to the highest quintile (fixed detection likelihood (sensitivity/[1−sensitivity]) ratios for adjacent quintiles) while matching estimates for average practice in the middle quintile (85% for medium adenomas, 95% for large adenomas)5; (3) maximum sensitivity for adenomas was 98%. Sensitivity for adenomas was then varied to match ADR values with 0.1 point precision. The estimates were independent of adenoma location. KPNC data on cancer diagnoses after colonoscopy were compared to the cancer incidence predicted by the model.

Complication risk of colonoscopy

Adverse events for colonoscopy including polypectomy used age-specific complication rates derived from published literature (Table 1).19, 20

Costs of screening and treatment

Approximate societal costs of colonoscopy, complications and colorectal cancer treatment utilized 2007 Medicare payment rates and co-payments (Table 1).21–23 All costs included patient time valued at median US wage in 2013, updated to December 2013 based on general Consumer Price Index.24 Costs of colonoscopy with polypectomy included a variable component for polyp resection and pathology based on number of polyps resected.

Outcomes

Outcomes included were colorectal cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, number of colonoscopies, complications, and the costs of screening and treatment in unscreened persons and in those screened according to ADR quintiles. In addition, we estimated the average outcome differences associated with 5 percentage-point higher ADRs using linear regression. Outcomes were discounted to 2010 at a fixed annual rate of 3% and reported with uncertainty ranges.

Analysis

We simulated a US population cohort of 10 million men and women born January 1, 1960. For patients reaching the age of 50 without having colorectal cancer diagnosed (9.4 million), we compared the outcomes of no screening, or of screening colonoscopy at ages 50, 60 and 70 by physicians from one of the five ADR quintiles.12 Patients with adenomas detected were assumed to receive surveillance according to current United States guidelines.25 We assumed that the same physician performed all screening and surveillance colonoscopies in each individual patient, and thus, ADR exposure level remained constant during the life-course.

Multiway probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to derive 95% CI’s for all outcomes evaluated.26, 27 In 1,000 simulation runs of 10 million persons we varied 13 key parameters along uniform, beta, or lognormal distributions (Table 1).

Sensitivity analysis

We evaluated the robustness of results using several alternative modeling scenarios. Between-quintile ADR variation was attributed either: entirely to exam sensitivity for small lower-risk adenomas; equally to exam sensitivity for small, medium and large adenomas; or partially to exam sensitivity and to adenoma prevalence or colonoscopy completion rates (~1% higher per percentage-point higher ADR). Adenoma patients received either more intensive or no surveillance. We also evaluated a 50% increased colonoscopy cost level and undiscounted outcomes.

To evaluate data uncertainty, we performed a bootstrap analysis on the association between observed average ADR and interval cancer rates across ADR quintiles and contrasted the resulting weak and strong association samples (2.5–97.5th percentile) to the modeling scenarios.

Statistical Software

For microsimulation modeling we used Delphi 7.0 (Borland Software Corp). Additional data analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

A total of 57,588 screening colonoscopies were performed by 136 KPNC physicians during 1998–2010 (Table 2). After exclusion of patients with less than 6 months follow-up (n=7,718), there were 179,812 person-years of follow-up time. Interval colorectal cancer incidence per 100,000 person-years varied from 66.6 (95% CI: 43.2–97.0) in ADR quintile 1 to 39.0 (95% CI: 22.7–62.4) in quintile 4, but was 49.7 (95% CI 27.8–81.9) in quintile 5.

Table 2.

Kaiser Permanente Northern California patient and physician characteristics according to quintile of adenoma detection rate.

| Variable | Quintiles of adenoma detection rate

|

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Physician characteristics | ||||||

| Physicians, n | 27 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 136 |

| Adenoma detection rate | ||||||

| Mean | 15.32 | 21.27 | 25.61 | 30.89 | 38.66 | 26.45 |

| Median | 16.56 | 21.50 | 25.70 | 30.96 | 38.86 | 25.70 |

| Range | 7.35–19.05 | 19.06–23.85 | 23.86–28.40 | 28.41–33.50 | 33.51–52.51 | 7.35–52.51 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Screened adults, n | 11,799 | 10,579 | 10,978 | 12,918 | 11,314 | 57,588 |

| Cancer diagnosed within 6 months | 114 | 93 | 106 | 176 | 119 | 608 |

| Less than 6 months of follow-up | 1,452 | 1,253 | 1,179 | 1,421 | 1,805 | 7,110 |

| Proportion male, % 95% CI | 42.8 (34.6,51) | 43.4 (36,50.8) | 44.1 (36.2,51.9) | 45.0 (37.3,52.7) | 44.5 (37.1,51.9) | 44.0 (36.1,51.8) |

| Mean age, years 95% CI | 61.3 (59.3,63.2) | 61.3 (59.5,63.1) | 62.0 (59.1,64.9) | 62.0 (60.1,64) | 61.9 (59.5,64.3) | 61.7 (59.3,64.1) |

| Age groups, % | ||||||

| 50–54 years | 25.6 | 25.4 | 23.5 | 23.6 | 24.0 | 24.4 |

| 55–59 years | 21.4 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 20.3 |

| 60–64 years | 20.7 | 21.9 | 20.7 | 20.2 | 20.8 | 20.8 |

| 65–69 years | 14.9 | 15.4 | 15.0 | 16.2 | 15.4 | 15.4 |

| 70–74 years | 9.7 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.3 |

| 75–84 years | 6.9 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 7.9 |

| >85 years | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 69.0 | 73.0 | 67.9 | 65.7 | 66.5 | 68.3 |

| Hispanic | 5.9 | 5.5 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 7.0 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.8 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.2 |

| Asian | 7.4 | 7.8 | 10.2 | 14.5 | 13.0 | 10.7 |

| Native Americans | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Other | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 |

| Unknown | 7.2 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 6.0 |

| Patients with adenomas detected, na | 1,808 | 2,250 | 2,811 | 3,991 | 4,374 | 15,234 |

| Person-years of follow-up b | 39,033 | 33,251 | 33,564 | 43,635 | 30,200 | 179,682 |

| Interval cancers diagnosed c | 26 | 18 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 90 |

| Incidence per 100,000 yr−1 95% CI | 66.6 (43.2,97.0) | 54.1 (32,85.3) | 41.7 (23.1,70.8) | 39.0 (22.7,62.4) | 49.7 (27.8,81.9) | 50.1 (40.3,61.6) |

Abbreviations: yr−1= per person-year; CI = confidence interval.

Including only histologically confirmed adenomas by pathologists.

Patients were followed from the date of their index colonoscopy until the first of the following events: negative follow-up colonoscopy, diagnosed cancer, death or departure from membership, 10 years follow-up, or study end (31 December 2010).

Interval cancers were colorectal adenocarcinomas diagnosed ≥6 months and ≤10 years of the index colonoscopy

Simulated interval cancer incidence

To replicate the average detection rate per ADR quintile in the KPNC cohort in the model, colonoscopy sensitivity was varied according to adenoma size from: 14.7% in quintile 1, 41.0% in quintile 3 to 98% in quintile 5 for small adenomas; 39.6 to 98% for medium adenomas; and 88.0 to 98% for large adenomas (see Table 1 for estimates per ADR quintile). The model closely reproduced observed colorectal cancer incidence in the lower four ADR quintiles, but underestimated incidence in the upper quintile (eFigure 7).

Lifetime colorectal cancer outcomes without and with screening

The model estimated average overall life expectancy without exposure to screening and surveillance was 81.1 years, the lifetime colorectal cancer risk was 34.2/1,000 (95%CI:25.9–43.6), lifetime colorectal cancer mortality risk was 13.4/1,000 (95%CI:10.0–17.6), and 138.7 life-years per 1,000 patients (95%CI:103.0–184.0) were lost due to colorectal cancer, which is 10.4 years per cancer death (Table 3). Among screened patients, simulated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer incidence was on average 19.1/1,000 (95%CI:14.3–24.8), mortality was 3.8/1,000 (95%CI:2.8–5.2); and 42.7 (95%CI:30.9–57.5) life-years per 1,000 patients were lost to the disease.

Table 3.

Modeling results: Outcomes associated with colonoscopy screening according to quintile of adenoma detection rate.a b

| Lifetime health outcomes per 1,000 patients | No screening

|

Screening; Quintiles of adenoma detection rate

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95%CIc | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | |||

| Colorectal cancer outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Colorectal cancer cases | 34.2 | (25.9–43.6) | 26.6 | (20–34.3) | 21.9 | (16.3–28.1) | 19.0 | (14–24.7) | 15.6 | (11.6–20.3) | 12.5 | (9.3–16.5) |

| Advanced cancer cases d | 16.8 | (12.3–22.6) | 7.3 | (5.2–9.9) | 5.6 | (4–7.7) | 4.7 | (3.4–6.3) | 3.7 | (2.6–5.1) | 2.9 | (2.1–3.9) |

| Colorectal cancer deaths | 13.4 | (10–17.6) | 5.7 | (4.2–7.7) | 4.5 | (3.2–6) | 3.7 | (2.7–5) | 3.0 | (2.1–4) | 2.3 | (1.7–3.1) |

| Years of life lost e | 138.7 | (103–184) | 61.4 | (44.4–82.9) | 49.2 | (35.6–66.1) | 41.8 | (30.4–55.9) | 33.9 | (24.4–46.3) | 27.0 | (19.5–36.2) |

| Effectiveness of screening | ||||||||||||

| Prevented cancer cases | - | - | 7.7 | (5.4–10.3) | 12.3 | (9.1–16.2) | 15.3 | (11.4–19.8) | 18.7 | (14–24) | 21.7 | (16.2–27.8) |

| Prevented cancer deaths | - | - | 7.7 | (5.8–10) | 8.9 | (6.7–11.6) | 9.6 | (7.2–12.6) | 10.4 | (7.8–13.8) | 11.1 | (8.2–14.6) |

| Years of life saved | - | - | 77.3 | (58–102.3) | 89.5 | (66.5–117.1) | 96.8 | (71.8–127.4) | 104.8 | (78.2–139.1) | 111.7 | (82.8–148.4) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval.

All outcomes were discounted to 2010 at a fixed rate of 3% per year. For undiscounted outcomes see eTable 2.

Adenoma detection rate (ADR) quintiles were derived from 57,588 colonoscopies performed by 136 gastroenterologists in Kaiser Permanente Northern California, a large integrated healthcare delivery system in the United States. The averages (and ranges) of ADR for quintiles 1 through 5 were 15.32% (7.35–19.05%), 21.27% (19.06–23.85%), 25.61% (23.86–28.40%), 30.89% (28.41–33.50%) and 38.66% (33.51–52.51%), respectively.

95% confidence intervals were derived by multiway probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Advanced-stage cancers were stage III–IV according to the 5th edition Cancer Staging Manual from the American Joint Committee on Cancer.40

Years of life lost to the disease were obtained by subtracting the simulated lifetimes with disease from the simulated lifetimes based on other-cause mortality rates.

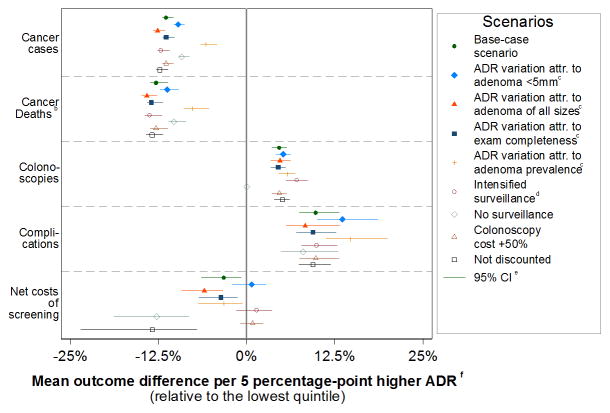

The modeled risks were inversely related to the level of adenoma detection (Table 3). The simulated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer per 1,000 was 26.6 (95%CI:20.0–34.3) for patients of physicians in ADR quintile 1, and was monotonically lower for subsequent quintiles; in ADR quintile 5, the simulated lifetime colorectal cancer risk was 12.5 (95%CI:9.3–16.5). Compared to ADR quintile 1, simulated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer was on average 11.4% (95%CI:10.3–11.9) lower per 5 percentage-point higher ADR (Figure 1). Similarly, the simulated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer death and associated years-of-life lost per 1,000 patients were lower from quintile 1 (5.7, 95%CI:4.2–7.7 and 61.4, 95%CI:44.4–82.9) to quintile 5 (2.3, 95%CI:1.7–3.1 and 27.0, 95%CI:19.5–36.2). The simulated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer death was on average 12.8% lower (95%CI:11.1–13.7) for every 5 percentage-point higher physician ADR.

Figure 1. Sensitivity analysis results: The adenoma detection rate-outcome relationship for various modeling scenarios.a.

Abbreviations: ADR = adenoma detection rate; attr. = attributed.

a95% confidence intervals were relatively narrow because we applied the same assumptions for the natural history of colorectal cancer to all patients (Table 1). Colonoscopy sensitivity was the only assumption varied independently for each ADR quintile.

bResults were similar for years of life lost to cancer.

cWe evaluated four alternative causal models for the observed cancer incidence differences across the ADR quintiles: in scenario 2 all variation in ADR was attributed to sensitivity of colonoscopy for small adenomas under 5 mm, which varied from 5.4 in the lowest quintile to 98% in the highest quintile; in scenario 3 all ADR variation was attributed equally to sensitivity for small, medium and large adenomas, which varied from 26.0 to 98%; in scenario 4 it was assumed that the rate of completeness of colonoscopy along with differences in colonoscopy sensitivity accounted for the observed ADR-variations, varying from 75% to 98%; in scenario 4 adenoma prevalence was assumed to be up to a relative 25% higher with higher ADR.

dUnder intensified surveillance, we assumed that all patients with adenomas detected at colonoscopy underwent surveillance at 3 years after the procedure, and patients with a negative surveillance colonoscopy underwent surveillance at 5 years. For reference, in the base-case analysis, patients with adenomas detected at colonoscopy were referred for surveillance after 3 or 5 years, depending on the number and size of the adenomas detected. Likewise, patients with a negative surveillance colonoscopy were referred for a follow-up colonoscopy in 5 or 10 years, depending on whether the preceding interval was 3 or 5 years.

e95% confidence intervals were derived by multiway probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

fThe mean differences in simulated outcomes per 5 percentage-point higher ADR were derived by linear regression, and presented relative to the model outcomes for ADR quintile 1 (formula: 5 × betaols/outcomeq1).

Colonoscopy volume and complications

The model’s total estimated number of colonoscopies per 1,000 patients was progressively higher from ADR quintile 1 (2,777, 95%CI:2,626–2,943) to quintile 5 (3,376, 95%CI:3,081–3,681) (Table 4), an average of 4.6% (95%CI:3.6–5.7) for every 5-point higher ADR (Figure 1). This difference was related to more frequent surveillance in patients of physicians with higher ADR. The simulated lifetime risk (per 1,000) of serious gastrointestinal complications such as post-polypectomy bleeding and perforation was also higher from ADR quintile 1 (2.2, 95%CI:1.5–3.1) to quintile 5 (3.2/1,000, 95%CI:2.3–4.4), as were the overall complications (6.0, 95%CI:4.0–8.5 to 8.9, 95%CI:6.1–12.0) and fatal complications (0.03 to 0.05). Overall, the simulated risk of complications was on average 9.8% (95%CI:7.5–13.2) higher for every 5-point higher ADR.

Table 4.

Modeling results: Resources and complications for colonoscopy screening according to quintile of adenoma detection rate. a b

| Resources and complications per 1,000 patients | No screening

|

Screening; Quintiles of adenoma detection rate

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95%CIc | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | Mean | 95%CIc | |||

| Screening resources used | ||||||||||||

| Total colonoscopies | - | - | 2,777 | (2626–2943) | 2,980 | (2786–3197) | 3,094 | (2873–3329) | 3,252 | (2985–3533) | 3,376 | (3081–3681) |

| Screening colonoscopies | - | - | 2,008 | (1972–2041) | 1,948 | (1901–1993) | 1,912 | (1858–1964) | 1,857 | (1794–1921) | 1,807 | (1736–1885) |

| Surveillance colonoscopies d | - | - | 769 | (584–968) | 1,032 | (796–1290) | 1,182 | (915–1465) | 1,395 | (1074–1728) | 1,569 | (1204–1935) |

| Colonoscopies with polypectomy (screening and surveillance) | - | - | 956 | (742–1176) | 1,187 | (938–1424) | 1,312 | (1045–1553) | 1,479 | (1188–1733) | 1,599 | (1284–1862) |

| Colonoscopy-related complications | - | - | 6.0 | (4–8.5) | 7.4 | (5–10.1) | 8.0 | (5.4–10.8) | 8.6 | (5.9–11.7) | 8.9 | (6.1–12) |

| Serious GI complications | - | - | 2.2 | (1.5–3.1) | 2.7 | (1.8–3.7) | 2.9 | (2–4) | 3.2 | (2.2–4.3) | 3.2 | (2.3–4.4) |

| Fatal GI complications e | - | - | 0.03 | n.a. | 0.04 | n.a. | 0.04 | n.a. | 0.05 | n.a. | 0.05 | n.a. |

| Other GI complications | - | - | 2.2 | (1.4–3.1) | 2.6 | (1.8–3.6) | 2.8 | (2–3.9) | 3.1 | (2.1–4.2) | 3.2 | (2.2–4.3) |

| Cardiovascular complications | - | - | 1.6 | (1.1–2.3) | 2.0 | (1.4–2.7) | 2.1 | (1.5–2.9) | 2.3 | (1.6–3.2) | 2.4 | (1.7–3.2) |

| Financial resources used (US $ million) f | ||||||||||||

| Total medical costs | 3.1 | (2.3–4) | 5.2 | (4.4–6) | 5.1 | (4.3–5.9) | 5.0 | (4.2–5.8) | 4.9 | (4.2–5.7) | 4.9 | (4.1–5.6) |

| Screening costs | - | - | 2.8 | (2.5–3.1) | 3.1 | (2.7–3.4) | 3.2 | (2.8–3.7) | 3.5 | (3–4) | 3.7 | (3.2–4.2) |

| Colonoscopy costs | - | - | 2.7 | (2.4–3.1) | 3.0 | (2.6–3.4) | 3.2 | (2.8–3.6) | 3.4 | (3–3.9) | 3.6 | (3.1–4.2) |

| Complication costs | - | - | 0.0 | (0–0.1) | 0.0 | (0–0.1) | 0.0 | (0–0.1) | 0.1 | (0–0.1) | 0.1 | (0–0.1) |

| Treatment costs | 3.1 | (2.3–4) | 2.4 | (1.8–3.1) | 2.0 | (1.5–2.6) | 1.7 | (1.3–2.3) | 1.5 | (1.1–1.9) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) |

| Net screening costs g | - | - | 2.1 | (1.8–2.4) | 2.0 | (1.6–2.4) | 1.9 | (1.5–2.3) | 1.9 | (1.4–2.3) | 1.8 | (1.3–2.3) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; GI = gastrointestinal; n.a. = not assessed.

All outcomes were discounted to 2010 at a fixed rate of 3% per year. For undiscounted outcomes see eTable 3.

Adenoma detection rate (ADR) quintiles were derived from 57,588 colonoscopies performed by 136 gastroenterologists in Kaiser Permanente Northern California, a large integrated healthcare delivery system in the United States. The averages (and ranges) of ADR for quintiles 1 through 5 were 15.32% (7.35–19.05%), 21.27% (19.06–23.85%), 25.61% (23.86–28.40%), 30.89% (28.41–33.50%) and 38.66% (33.51–52.51%), respectively.

95% confidence intervals were derived by multiway probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Patients with adenomas detected had surveillance colonoscopies 3 years after the detection of ≥1 large adenoma or ≥3 adenomas of any size, and 5 years after the detection of ≤3 adenomas with a diameter of <10 mm. In case of a negative surveillance colonoscopy, the next interval was 5 or 10 years, depending on whether the length of the preceding interval was 3 or 5 years. Surveillance was continued until death or diagnosis of cancer.

For the simulated effect of fatal perforations on life-years lost, we assumed immediate death.

Besides resources for endoscopy and endoscopy-related complications, screening colonoscopy also influenced the modeled resources for cancer care. Higher ADR was associated in the model with a lower use of these resources, because of lower associated cancer incidence.

Net screening costs were derived by comparing the estimated total medical costs in case of screening (screening and cancer treatment costs) with the total medical costs in case of no screening. Minor inconsistencies in the resulting net costs are due to rounding.

Estimated costs of screening and treatment

For ADR quintile 1, estimated colonoscopy-related costs in US dollars per 1,000 patients were $2.7 million (95%CI:2.4–3.1), and estimated treatment costs were $2.4 million (95%CI:1.8–3.1), for an estimated total of $5.2 million (95%CI:4.4–6.0) without adjustment and $2.1 million (95%CI:1.8–2.4) with adjustment for the estimated costs without screening (Table 4). For higher ADR quintiles, estimated colonoscopy costs were higher, but estimated treatment costs were lower, for lower estimated total costs ($4.9 million, 95%CI:4.1–5.6) and net screening costs ($1.8 million, 95%CI:1.3–2.3) in quintile 5. Estimated net screening costs were on average 3.2% lower (95%CI:0.8–6.4) for every 5-point higher ADR.

Sensitivity analyses

The simulations were stable to various assumptions regarding colorectal carcinogenesis, colonoscopy efficacy and surveillance intervals (Figure 1). Although simulated costs were more unstable, the absolute corresponding cost differences were small (eTable 1). Without discounting, the estimated benefits of higher ADR were approximately twice as large as with discounting (eTable 2–3).

For ADR quintiles 1 to 4, strong and weak association scenarios from the bootstrap analysis for observed ADR and cancer incidence data were within the predicted ranges of the sensitivity analysis models (eFigure 7b).

DISCUSSION

This study used data from a large community-based United States healthcare system in a microsimulation model to estimate the lifetime outcomes and costs of colonoscopy screening at different levels of adenoma detection.10 Our results suggest that higher adenoma detection rates may be associated with up to 50–60% lower lifetime colorectal cancer incidence and mortality without higher net screening costs despite a higher number of colonoscopies and polypectomy-associated complications.

The model’s differences in observed interval colorectal cancer incidence were assumed to result from differences in the sensitivity of the exam, particularly for small-to-medium-sized adenomas. However, ADR may act as a surrogate for other aspects of colonoscopy quality, such as the test completeness, adequacy of lesion resection, and removal of more aggressive lesions such as sessile serrated polyps.28 Although some of these alternative explanations were evaluated in sensitivity analyses, with similar long-term results (Figure 1), we could not establish which factors accounted for the observed differences (eFigure 7b), and whether others might be involved.

The frequency and intensity of surveillance of adenoma patients may also contribute to patient outcome differences, because higher ADRs increase the number of patients for active surveillance.25 However, sensitivity analyses indicated that surveillance did not account for the simulated survival benefits for patients of physicians with higher ADRs (Figure 1). Future research is needed to assess whether the current intensity of surveillance is still appropriate if test sensitivity further increases.

Prior studies have shown an inverse relationship between ADR level and the patient’s risk of colorectal cancer up to 5 years after colonoscopy.29–31 A recent large study found that patients of physicians in the highest ADR quintile had a 48% lower disease risk and a 62% lower mortality risk compared to the lowest quintile.10 Adenoma detection rates may relate to patient outcomes over a lifetime of colonoscopy screening and surveillance. Our model estimated that discounted lifetime incidence and mortality risks averaged 11–13% lower for every 5-point higher ADR, which translates to overall differences of 53–60% between the lowest and highest ADR quintiles. Higher ADR was associated in the model with up to 34.4 additional life-years saved per 1,000 patients, which represents about 10 years per prevented cancer death, 2 weeks per average patient, and one-third of the maximum potential mortality benefit derived from screening (5 weeks per patient).

Screening colonoscopy is considered cost-effective for preventing colorectal cancer through adenoma detection and removal.12, 32 However, it has been suggested that incentivizing higher adenoma detection, for example through value-based purchasing programs,33 could lead to unacceptably higher cost because of more frequent surveillance in patients with low-risk adenomas.11 Our model suggests that higher detection rates are associated with only a moderately higher total number of colonoscopies: although the average surveillance patient in the modeling analysis received about twice as many procedures as a patient without detected adenomas, the additional proportion of patients undergoing surveillance with higher detection rates was limited to a maximum of 17%. By evaluating the costs for screening, surveillance, screening-associated complications and cancer care, our model suggested that ADR is not associated with higher overall costs.

Another theoretical disadvantage of higher ADRs is a higher risk of complications due to more colonoscopies and polypectomies. The model suggested that for every 5-point higher ADR the lifetime complication risk is on average 10% higher. The corresponding absolute risk difference of 0.6/1,000 was counterbalanced in the model by a 3.0/1,000 lower risk of colorectal cancer and a 0.7/1,000 lower risk of disease-related mortality (eTable 1). Our model included mild gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or abdominal pain and rare fatal complications. The model’s complication rates are somewhat lower than those presented by other studies,28 because we adjusted our estimates for the risk of similar events in the group unexposed to colonoscopy.19

The model predicted all colorectal cancer outcomes to be lower for every higher quintile of adenoma detection. These predictions closely replicated the observed interval cancer incidence in the lower four ADR quintiles, but underestimated adenoma detection and interval cancer incidence for the highest quintile (eFigures 7–8). Although this suggests more uncertainty for the associations beyond approximately 30% (quintile 4 average), in a much larger sample of colonoscopies for all indications from the same data source, a plateau in outcome differences across ADR quintiles was not observed.10

This study has some other potential limitations. First, we confined the ADR estimates and analyses to screening colonoscopies. This decreased the number of interval cancers and therefore the precision. However, sensitivity analyses indicated that this did not have a strong effect on long-term model projections (eFigure 7b). Second, modeled colorectal adenomas and cancer risk without screening included >10-year-old data. Uncertainty in corresponding model parameters was assessed with probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Third, our findings for the average association between ADR and patient outcomes do not necessarily mean that modifying ADR alone in individual physicians would lead to fewer interval cancers for their patients, given modeling cannot prove causal relationships. Fourth, our estimates assumed compliance with screening and surveillance guidelines and that patients receive colonoscopies from physicians with similar ADRs throughout their lifetimes. Finally, our cost estimates used Medicare rates and co-payments without supplemental anesthesia costs, and thus may not represent true societal screening costs.34 We also assumed that there was no overuse of surveillance or screening.35 However, sensitivity analyses suggested that these surveillance and cost-related factors may not have a large net effect (Figure 1, eTable 1).

Conclusions

In this microsimulation modeling study, higher adenoma detection rates in screening colonoscopy were associated with lower lifetime risks of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality without being associated with substantially higher overall costs. Future research including other direct colonoscopy quality indicators is needed to assess why adenoma detection rates vary, and if increasing adenoma detection would be associated with improved patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the United States National Institutes of Health (# U54 CA163262, and also U01 CA152959, U01 CA151736, U24 CA171524). The funder played no role for this report.

Footnotes

Netherlands Institute of Health Sciences, Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Department of Public Health, Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Departments of Family Medicine and Community Health, and of Epidemiology in the Perelman School of Medicine, and the Leonard Davis Center for Health Economics and Center for Public Health Initiatives, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA, United States

Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Research & Evaluation, Pasadena, CA, United States

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, United States

CONTRIBUTORS:

Reinier G.S. Meester M.Sc.1,2 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting. He had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data.

Chyke A. Doubeni M.D. M.P.H.3 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, the interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content.

Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar Ph.D.2 made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Christopher D. Jensen Ph.D.4 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, and critical revision for important intellectual content;

M.P. van der Meulen M.D.2 made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data for the work, and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Theodore R. Levin M.D.4 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Virginia P. Quinn Ph.D.5 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Joanne E. Schottinger M.D.5 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Ann G. Zauber Ph.D.6 made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data for the work, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Douglas A. Corley M.D., Ph.D.4 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content;

Marjolein van Ballegooijen M.D., Ph.D.2 made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, the interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content. She had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data.

Wei K. Zhao M.P.H.4 made substantial contributions to the acquisition of the data for the work.

Amy R. Marks M.P.H.4 made substantial contributions to the acquisition of the data for the work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

None of the authors report conflicts of interest.

DISCLAIMERS:

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed September, 2014];SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Colon and Rectum Cancer. 2014 http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html/

- 2.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 19;369(12):1095–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doubeni CA, Weinmann S, Adams K, et al. Screening colonoscopy and risk for incident late-stage colorectal cancer diagnosis in average-risk adults: a nested case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Mar 5;158(5 Pt 1):312–320. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Jansen L, Knebel P, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer up to 10 years after screening, surveillance, or diagnostic colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2014 Mar;146(3):709–717. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Feb;101(2):343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson DJ, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, et al. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014 Jun;63(6):949–956. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrar WD, Sawhney MS, Nelson DB, Lederle FA, Bond JH. Colorectal cancers found after a complete colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Oct;4(10):1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2533–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adler A, Wegscheider K, Lieberman D, et al. Factors determining the quality of screening colonoscopy: a prospective study on adenoma detection rates, from 12,134 examinations (Berlin colonoscopy project 3, BECOP-3) Gut. 2013 Feb;62(2):236–241. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 3;370(14):1298–1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin GL, Fennimore B, Ahnen DJ. Can colonoscopy remain cost-effective for colorectal cancer screening? The impact of practice patterns and the Will Rogers phenomenon on costs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Mar;108(3):296–301. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Nov 4;149(9):627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Mar 3;91(5):434–437. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993 Dec 30;329(27):1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010 May 8;375(9726):1624–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Sep;107(9):1315–1329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. quiz 1314, 1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen CD, Doubeni CA, Quinn VP, et al. Adjusting for Patient Demographics Has Minimal Effects on Rates of Adenoma Detection in a Large, Community-based Setting. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Apr;13(4):739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jun 16;150(12):849–857. W152. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Feb 5;95(3):230–236. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zauber AG, Knudsen AB, Rutter CM, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of CT Colonography to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. 2007 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/downloads/id52TA.pdf. [PubMed]

- 22.Leffler DA, Kheraj R, Garud S, et al. The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Oct 25;170(19):1752–1757. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 May 7;100(9):630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Labor. [Accessed January 22, 2014];Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014 http://www.bls.gov/

- 25.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012 Sep;143(3):844–857. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning WG, Fryback DG, Weinstein MC. Reflecting uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. In: Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doubilet P, Begg CB, Weinstein MC, Braun P, McNeil BJ. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. A practical approach. Med Decis Making. 1985 Summer;5(2):157–177. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8500500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality Indicators for Colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 2; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminski MF, Regula J, Butruk E, et al. Quality Indicators for Colonoscopy and the Risk of Interval Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(19):9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baxter NN, Sutradhar R, Forbes SS, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Rabeneck L. Analysis of administrative data finds endoscopist quality measures associated with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011 Jan;140(1):65–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper GS, Xu F, Barnholtz Sloan JS, Schluchter MD, Koroukian SM. Prevalence and predictors of interval colorectal cancers in medicare beneficiaries. Cancer. 2012 Jun 15;118(12):3044–3052. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin B, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, et al. Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps, 2008: A Joint Guideline From the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewett DG, Rex DK. Improving colonoscopy quality through health-care payment reform. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):1925–1933. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladabaum U, Levin Z, Mannalithara A, Brill JV, Bundorf MK. Colorectal testing utilization and payments in a large cohort of commercially insured US adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1513–1525. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheffield KM, Han Y, Kuo YF, Riall TS, Goodwin JS. Potentially inappropriate screening colonoscopy in Medicare patients: variation by physician and geographic region. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):542–550. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gohel TD, Burke CA, Lankaala P, et al. Polypectomy rate: a surrogate for adenoma detection rate varies by colon segment, gender, and endoscopist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Jul;12(7):1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams JE, Holub JL, Faigel DO. Polypectomy rate is a valid quality measure for colonoscopy: results from a national endoscopy database. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Mar;75(3):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 20;343(3):169–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 20;343(3):162–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott - Raven Publishers; 1997. http://cancerstaging.org/references-tools/deskreferences/Documents/AJCC5thEdCancerStagingManual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.