Abstract

Several theories posit that alcohol is consumed both in relation to one’s mood and in relation to different motives for drinking. However, there are mixed findings regarding the role of mood and motives in predicting drinking. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods provide an opportunity to evaluate near real-time changes in mood and motives within individuals to predict alcohol use. In addition, endorsement of criteria of an alcohol use disorder (AUD) may also be sensitive to changes within subjects. The current study used EMA with 74 moderate drinkers who responded to fixed and random mood, motive, alcohol use, and AUD criteria prompts over a 21-day assessment period. A temporal pattern of daytime mood, evening drinking motivation, and nighttime alcohol use and acute AUD symptoms on planned drinking days was modeled to examine how these associations unfold throughout the day. The results suggest considerable heterogeneity in drinking motivation across drinking days. Additionally, an affect regulation model of drinking to cope with negative mood was observed. Specifically, on planned drinking days, the temporal association between daytime negative mood and the experience of acute AUD symptoms was mediated via coping motives and alcohol use. The current study found that motives are dynamic, and that changes in motives may predict differential drinking patterns across days. Further, the study provides evidence that emotion-regulation-driven alcohol involvement may need to be examined at the event level to fully capture the ebb and flow of negative affect motivated drinking.

Keywords: alcohol motives, acute AUD symptoms, ecological momentary assessment

Both folk and scientific theories alike purport relationships between mood and alcohol use. The self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian & Galanter, 1990), tension reduction hypothesis (Conger, 1956), and affective processing model (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004) are just some examples of models that suggest individuals use alcohol to cope with negative affect. Support for these models range from cross-sectional research demonstrating a relationship between negative affect and alcohol misuse (Kalodner, Delucia, & Ursprung, 1989), longitudinal studies demonstrating prospective prediction of alcohol use (Kaplow, Curran, Angold, & Costello, 2001), epidemiological studies showing the comorbidity of mood/anxiety disorders with alcohol use disorders (AUDs; B. F. Grant et al., 2005), and experience sampling studies that show day-to-day relationships between affect and alcohol consumption (Simons, Dvorak, Batien, & Wray, 2010). However, much of this research fails to account for individual differences in self-reported drinking motivations.

The motivational model of alcohol use (Cox & Klinger, 1988) posits that drinking motives are the most proximal antecedents to alcohol use, and research shows that different drinking motives are associated with distinct use patterns (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992). The Cox–Klinger model purports that drinking motives differ across two primary dimensions: the source of the motivation (internal or external) and type of reinforcement (positive or negative). According to this model, internal motives are those directly related to affect regulation; therefore, internal motives can be referred to as mood-regulatory motives. External motives are indirectly related to affect regulation through incentives. For example, affiliative incentives may directly drive the motive of drinking to socialize, and affiliating with others can then have an effect on mood. Drinking to increase the likelihood of a desired outcome or decrease the likelihood of an unpleasant outcome defines positive and negative reinforcement motives, respectively. Enhancement motives are associated with drinking to enhance mood, whereas coping motives are associated with drinking to ameliorate negative mood. Further, social motives are associated with drinking to improve social interactions, whereas conformity motives are associated with drinking to avoid negative social interactions or to avoid peer disapproval (Cooper et al., 1992).

Based on cross-sectional studies (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005), negative reinforcement motives (especially coping motives) predict alcohol problems, even after controlling for the effects of alcohol use. However, associations between coping motives and alcohol use tend to be more complex, with null (Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005), and even inverse (V. V. Grant, Stewart, O’Connor, Blackwell, & Conrod, 2007; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2001), associations after controlling for other drinking motives.

Conversely, positive reinforcement motives are predictive of alcohol use, but are either unrelated (in the case of social motives) or indirectly related to alcohol problems via alcohol use (enhancement motives). However, work on drinking motives and alcohol use and problems fails to capture the immediate precursors that may affect drinking motivation (e.g., positive and negative mood) and the actual effect of current motivation on drinking behavior. In addition, motives such as drinking to cope have often been conceptualized as part of a more general pattern of behavior, and it is unclear if drinking to cope “in the moment” results in the same sorts of deleterious consequences. In other words, it is not clear whether the between-subjects findings could also be observed at the within-subjects level. Given the focus on affect regulation models of alcohol use, in the current study, we focus on the two internal (i.e., mood-related) drinking motives.

Recently, daily diary and ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies have examined drinking motives as moderators of the near real-time relationships between mood and alcohol use. Most of this research has been based on the theory-driven premise that the relationship between negative mood and drinking should be stronger for “coping drinkers.” However, these results have been inconsistent. For example, using a daily diary design, Mohr et al. (2005) found that negative event-drinking and negative mood-drinking relationships were stronger among those high in coping motives, but only for “drinking at home,” and not in other contexts. Multiple other studies have found weak or nonexistent moderation effects of coping motives (Armeli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010; Carney, Armeli, Tennen, Affleck, & O’Neil, 2000; Mohr et al., 2001; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004). and most studies that have found significant moderation effects are either not consistent with predictions (e.g., Hussong, Galloway, & Feagans, 2005; Todd, Armeli, Tennen, Carney, & Affleck, 2003) or have failed to replicate (Armeli, Todd, Conner, & Tennen, 2008; Hussong, 2007; Littlefield, Talley, & Jackson, 2012).

One potential explanation for these inconsistent results is that the measures used to assess drinking motivation rely on the assumption that drinking motives are best conceptualized as stable traits. However, there is evidence that motives vary within individuals and over time. In a recent longitudinal study, Littlefield, Vergés, Rosinski, Steinley, and Sher (2013) examined coping and enhancement motives across time in an attempt to identify distinct drinking classes based on these two forms of internally motivated drinking. However, they were unable to distinguish between coping and enhancement drinking, suggesting that individual drinking motivation may vary across situations and/or time. In a separate study, using a daily diary design, Arbeau, Kuiken, and Wild (2011) found that daily mood predicted coping and enhancement motives, suggesting not only that there is meaningful within-person variability in drinking motives but also that it may be related to mood. However, they did not report associations between drinking motives and alcohol outcomes. Nonetheless, these results suggest that drinking motives may mediate within-subject associations between daily mood and alcohol outcomes.

Both coping and enhancement motives have been cross-sectionally (Merrill & Read, 2010) and prospectively (Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014) linked to AUD symptoms (i.e., physical dependence and loss of control over use). Across several longitudinal studies, coping motives have been implicated in the development of an AUD (Beseler, Aharonovich, Keyes, & Hasin, 2008; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2001, 2003). Similarly, enhancement motives have been prospectively associated with AUD symptoms (Tragesser, Sher, Trull, & Park, 2007), though this may be a function of overlap with coping motives (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010). In addition, there is evidence that associations between problematic use patterns (consistent with an AUD) and drinking motives (particularly coping motives) may be more robust for men (Rutledge & Sher, 2001), suggesting that mood, motive, and use associations should be evaluated separately across gender.

Finally, all of these studies linking drinking motivation to pathological use utilize a between-subjects design for both motives and pathological symptoms. However, as noted, drinking motives appear to vary within person, across time, and across situations (Arbeau et al., 2011; Littlefield et al., 2013). The same may hold true for AUD symptoms. For example, in a recent EMA study, Simons et al. (2010) found that acute alcohol dependence symptoms could be modeled at the individual level. Despite the fact that AUD symptoms are typically assessed using retrospective self-report measures, and are intended to reflect behaviors that occur chronically over time, the symptoms involve specific behaviors and experiences that must occur at specific moments in time, and are thus appropriate for investigation via EMA. Further, modeling acute AUD symptoms within subjects may provide insight into the development of an AUD across subjects. It remains to be seen whether the observed between-subjects associations between AUD symptoms and drinking motives follow a similar pattern at the micro (i.e., within-subject) level. The current study addresses this issue.

Study Overview

The present study examines a theoretical model in which both the within-subjects and between-subjects effects of positive and negative mood on alcohol outcomes are mediated by mood-related (i.e., internal) drinking motives. We also examine the predictive effects of mood and internalizing (i.e., mood specific) motives on acute AUD symptoms as they occur in situ (see Simons et al., 2010). The current study had two primary hypotheses derived from the broader between-subjects literature.

Hypothesis 1: Daytime negative mood would be associated with drinking to cope, which, in turn, would be directly associated with acute AUD symptoms, but not alcohol use.

Hypothesis 2: Daytime positive mood would be associated with enhancement motives, which, in turn, would be associated with acute AUD symptoms via alcohol use.

Importantly, the present study is the first study of which we are aware to examine these hypotheses at both the within-subjects and between-subjects levels. Given that this is the first study to examine these hypotheses simultaneously at distinct levels, model parameters were examined for gender variance, though no specific hypotheses were made regarding gender differences.

Method

Participants

Participants (n = 74; 58.11% female) were recruited from a Midwest university for a study examining emotion and alcohol use. The sample ranged in age from 18 to 29 years (M = 21.30, SD = 2.07). Ninety-one percent of the sample was White, 1% was Black, 3% was Native American/Alaskan Native, 4% was Asian, and 1% was other.

Procedure

Screened participants (n = 1,895) completed an online survey assessing demographic information as well as various indices of alcohol use, including typical weekly alcohol use (assessed via the Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire; DDQ-M), problematic alcohol use (assessed via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT), and drinking motives (assessed via the Drinking Motives Questionnaire; DMQ). Participants who endorsed drinking 2 to 4 times per month (score of 2 or greater on the first item of the AUDIT) were invited to participate in the EMA study (n = 460). The first 80 individuals who responded to the invite were enrolled in the EMA portion. One participant had compliance <1% and reported no drinking episodes; these data were removed prior to analysis. Two individuals reported no alcohol use, and one individual reported alcohol use, but no daytime mood. Two individuals never reported on drinking motives (i.e., never endorsed a plan to drink). These five observations were also removed, resulting in a final analysis sample of n = 74. For the EMA study, participants carried a personal data device (PDD) for 21 days of self-monitoring. Participants were compensated for each completed assessment and could earn up to $150 for participation. Full descriptive data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data by Gender

| Variables | Men (n = 31)

|

Women (n = 43)

|

t(72) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | ||

| Screen data | |||||||

| Age | 21.07 | 1.88 | 18–27 | 21.47 | 2.21 | 18–29 | 0.82 |

| DDQ-M | 15.97 | 18.97 | 0–64 | 10.95 | 11.03 | 0–41 | −1.43 |

| AUDIT-Use | 8.13 | 1.65 | 4–12 | 6.91 | 1.78 | 4–11 | −3.01* |

| AUDIT-Prob | 4.30 | 3.52 | 0–16 | 5.19 | 3.89 | 0–14 | −1.03 |

| AUDIT-Total Score | 13.32 | 4.92 | 5–24 | 11.21 | 4.63 | 5–27 | 1.89 |

| PANAS-PAa | 3.53 | 0.80 | 1.50–4.60 | 3.24 | 0.68 | 1.70–4.10 | −1.12 |

| PANAS-NAa | 2.24 | 0.91 | 1.20–4.00 | 2.04 | 0.76 | 1.20–3.7 | −0.67 |

| DMQ-Cope | 2.32 | 0.89 | 1.20–4.80 | 2.52 | 1.00 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.90 |

| DMQ-Enhance | 3.26 | 0.88 | 1.60–5.00 | 3.28 | 0.73 | 1.00–4.40 | 0.14 |

| EMA datab | |||||||

| EMA Drinks | 7.76 | 6.38 | 0–24 | 5.13 | 4.69 | 0–24 | 5.09* |

| EMA AUD | 1.11 | 1.46 | 0–7 | 0.95 | 1.52 | 0–10 | 1.13 |

| EMA PM | 5.52 | 1.80 | 0.75–9.30 | 4.25 | 2.13 | 0.00–9.45 | 6.45* |

| EMA NM | 1.48 | 1.25 | 0.00–7.20 | 1.95 | 1.72 | 0.00–7.57 | −3.17* |

| EMA Cope | 1.50 | 1.17 | 0–4 | 1.85 | 1.24 | 0–4 | −3.04* |

| EMA Enhance | 3.04 | 0.78 | 0–4 | 3.13 | 0.80 | 0–4 | −1.12 |

Note. DDQ-M = Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire; AUDIT-Use = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Use Scale (Items 1 to 3); AUDIT-Prob = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Problems Scale (Items 4 to 10); PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Positive Affect; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Negative Affect; DMQ-Cope = Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Coping Scale; DMQ-Enhance = Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Enhancement Scale; EMA = ecological momentary assessment; EMA AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms assessed daily; PM = Daytime Positive Mood; NM = Daytime Negative Mood; Cope = Evening Coping Motives; Enhance = Evening Enhancement Motives.

PANAS was added after the start of the study; thus, these data are only available for n = 33 (n = 15 men; n = 18 women).

Generalized estimating equations used to compare EMA data.

p < .05.

Measures and Apparatus

Between-subjects screen

DDQ-M

The DDQ-M (Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) assesses typical weekly alcohol consumption. Individuals indicate the number of drinks consumed for each day of the week on a typical day in the last 6 months. They also indicate the number of hours they typically drink for that day. Previous research supports the validity and reliability of the DDQ-M as a measure of typical weekly alcohol consumption among college student samples (Dvorak, Simons, & Wray, 2011; Miller et al., 1998; Simons & Carey, 2006).

AUDIT

The AUDIT (α = .77; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, & de la Fuente, 1993) is a 10-item questionnaire used to assess problematic alcohol use. This measure consists of two separate scales: alcohol use (Items 1 to 3) and alcohol-related consequences (Items 4 to 10). The use scale items assess current alcohol use and the alcohol-related consequences assess consequences over the last year. Items are scored on a 5-point response scale. Research indicates that AUDIT scores from 8 to 15 represent a moderate level of alcohol-related consequences, with scores ≥16 being representative of more pathological use, and scores ≥20 indicating likely alcohol dependence (Donovan, Kivlahan, Doyle, Longabaugh, & Greenfield, 2006). Previous research indicates that AUDIT is a valid and reliable measure of alcohol use and related consequences in college student samples (Demartini & Carey, 2009, 2012).

DMQ

The DMQ is a 20-item measure used to assess stable (i.e., trait-like) drinking motivation. The DMQ is comprised of four subscales that index drinking motives across two domains: internal versus external, and positive reinforcement versus negative reinforcement. Individuals endorse reasons for drinking on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost never/never to 5 = almost always/always). For the current study, the internal motives (enhancement and coping) were of primary interest. Enhancement motives (α = .74; internal/positive reinforcement) represent motivation to drink in order to enhance positive mood (sample item, “Because it’s exciting”). Coping motives (α = .85; internal/negative reinforcement) represent the motivation to drink in order to ameliorate negative emotion (sample item, “To forget your worries”). The DMQ has shown good reliability, internal consistency, and predictive validity (Cooper, 1994).

Positive and Negative Affect Scales X (PANAS-X)

The PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1999), administered using the “in general” instructions, provides a measure of stable, or trait-like, positive and negative affect. The positive (α = .90) and negative (α = .91) affect scales consist of 10 items each. Individuals indicate the extent to which they experience each state “in general.” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely). There is a considerable amount of research supporting the psychometric properties of the 20-item positive and negative scales of the PANAS (Watson & Clark, 1999; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). In the current study, the PANAS was added after the start of data collection, and thus data are only available for 33 individuals (see Table 1).

Within-subjects EMA

PDD

The PDD used in the study was a Samsung Galaxy Player 4.0. This device uses the Android 2.3.5 operating system. The device measures 4.87 × 2.53 × 0.39 in. (H × W × D), weighs 4.27 oz, has a 1-GHz processor, 8 GB of internal storage, and is powered by a rechargeable lithium ion battery. Participants respond by pressing directly on the 4-in. WVGA LCD touch screen.

Overview of in situ assessments

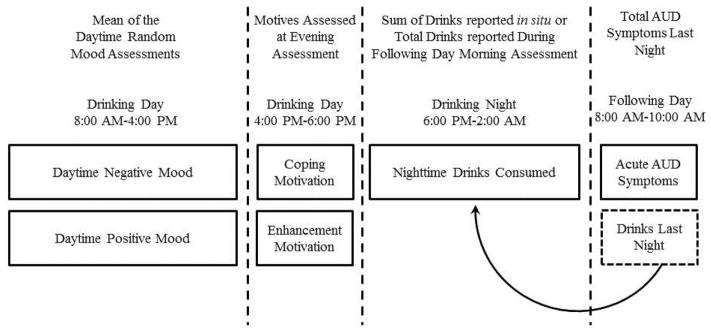

Participants in the EMA portion of the study carried a PDD and responded to three different assessments: morning (a self-initiated assessment occurring between 8:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m.), evening (a self-initiated assessment occurring between 4:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m.), and random mood and drinking assessments (occurring randomly nine times per day between 8:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.). Morning assessments primarily examined alcohol use and acute AUD symptoms that occurred the previous night (e.g., tolerance) or that morning (e.g., hangover). Evening assessments examined plans to drink, and on nights when participants reported plans to drink, drinking motives were assessed. Random assessments primarily assessed current mood and drinks consumed since last assessment (if currently drinking). To ensure temporal precedence, daytime mood was the mean of daily mood assessments from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Assessments of motives occurred from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. Only days in which drinking (assed during random prompts) occurred after the motives assessments were included in the analysis (i.e., from 6:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. the following day). Acute AUD symptoms were reported the following morning (see Figure 1). Participants could set the PDD to “vibrate” during inopportune times, and postpone random assessments for up to 10 min.

Figure 1.

Temporal ordering flowchart of discrete drinking day assessments.

Daytime mood was assessed with 15 items (“How ____ are you feeling right now?”) on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 11 (extremely). Negative mood was the mean of anxious, nervous, jittery, irritable, angry, frustrated, down, blue, depressed, and sad (α = .98). Positive mood was the mean of excited, enthusiastic, energetic, happy, and joyful (α = .93). Indicators for stressed, relaxed, and tired were also assessed, but are not included in the analysis. Previous research supports the use of these and similar scales to assess in situ mood states (Mohr et al., 2005; Simons et al., 2010).

Drinking motives were assessed with three items modified from existing measures (Cooper, 1994; V. V. Grant et al., 2007) to assess sadness coping (“I want to drink tonight to forget my worries, or because it helps me when I feel depressed”), anxiety coping (“I want to drink tonight to reduce my anxiety, and because it helps me when I’m feeling nervous”), and enhancement (“I want to drink tonight because it’s fun, and I like the way I feel when I drink”). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). In the current analysis, the coping motive was the mean of the sadness and anxiety coping items (α = .81).

Alcohol use was assessed using two different methods. During random assessments, participants were asked if they had consumed alcohol since the last assessment. If they responded in the affirmative, they were asked how many standard drinks they had consumed since the last assessment. During the initial lab session, participants were trained in the use of the PDD, and were given the traditional description for standard drinks (i.e., 1.5 fl. oz of spirits, 12 fl. oz traditional beer, 8 to 9 fl. oz malt liquor, and 5 fl. oz wine). Nightly alcohol use was the sum of the typical number of drinks reported in situ. In addition, during the morning assessment, participants were asked how many standard drinks they consumed the previous night. For nights in which all in situ drink reports were missing, the number of drinks reported in the morning assessment was used.

Acute AUD symptoms were based on AUD symptoms indexing a loss of control over alcohol use (e.g., “drank when promised self not to”), tolerance (e.g., “had to drink more to feel same effects”), and withdrawal (“experience withdrawal symptoms”). Participants were asked, “Did any of the following occur last night or this morning?” They were shown 10 items in a scrolling list, and asked to check off items that occurred. At the initial lab appointment, occurring prior to the 21-day data collection period, all items were discussed with participants to ensure they fully understood the meaning of each symptom and could accurately report on them during the self-monitoring period.

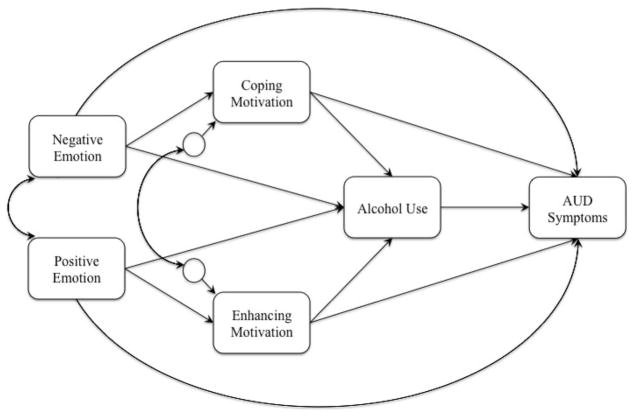

Analysis Overview

A multigroup multilevel path model was specified in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) such that the associations between mood, drinking motives, and alcohol outcomes were examined at both the within-subject and between-subjects levels across men and women. By parsing variance in the daily assessments across levels, we are able to examine both daily (state-like) associations as well as stable (trait-like) associations. At the within-subject level (i.e., Level 1), predictors were person-centered. At the between-subjects level (i.e., Level 2), predictors were grand-mean centered. The two mood indicators were the mean of lower order mood states. The hypothesized model is depicted in Figure 2. In order to compare within- and between-subjects associations, the same paths were modeled at both levels, with the exception of a day-of-week indicator, which was added as a covariate in the within-subjects model. As models are limited to estimating n−1 parameters (73 in this sample), and mirrored within-between subjects models require twice the number of parameters as a model at either level, we strived to maintain model parsimony whenever possible. Consistent with this, the day-of-week indicator was dummy coded (0 = Monday to Wednesday; 1 = Thursday to Sunday) to correspond to typical drinking days among college students. Age was initially added as a between-subjects covariate. However, age was not associated with alcohol use or acute AUD symptoms, and was thus dropped to maintain model parsimony. “Acute AUD symptoms” was highly skewed (skew = 2.79) and leptokurtic (kurtosis = 12.91). A square-root transformation was performed on this variable to normalize the distribution (skew = 1.49, kurtosis = 3.98) prior to analysis. Model intercepts were allowed to vary randomly; no model slopes had random variance components, and thus were fixed to zero. Participants rated motives only if they endorsed a plan to drink in the evening assessment. Nonplanned drinking occurred on 40% of drinking days, and, consequently, no motives were available for these days. As these data are not missing at random, we have excluded days in which individuals did not endorse a plan to drink. The analysis is separated by gender (i.e., multigroup) and evaluates associations between positive and negative mood, internal motives, alcohol consumption, and acute AUD symptoms at both the within- and between-subjects levels. We first estimate the hypothesized model with all paths constrained across gender. Modification indices were then used to identify and free significant gender differences in model paths. The final model estimated a total of 69 parameters.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of the association between emotion and alcohol outcomes via drinking motivation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics, separated by level and gender, are listed in Table 1. Bivariate correlations of between-subjects data are listed in Table 2. Most of the correlations showed similar associations between emotional predictors, drinking motives, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences. Two important distinctions stand out. First, there were robust positive associations between coping and enhancement motives assessed via the DMQ. However, the correlations between mean coping and enhancement motives assessed in near real-time via EMA were negative and not statistically significant. In addition, the respective correlations between motives assessed via the DMQ and via EMA showed little overlap in shared variance. AUDIT scores ranged from 5 to 27 (M = 12.10, SD = 4.84), suggesting a moderate level of problematic drinking in this sample, with at least some individuals likely meeting criteria for an AUD. Among women, 16.27% (n = 7) exceeded the diagnostic threshold AUDIT score of 15. Among men, 9.68% (n = 3) exceeded the diagnostic threshold AUDIT score of 19 (Donovan et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations of Between-Subjects Data

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | −.09 | −.09 | −.11 | −.00 | .19 | .09 | −.07 | .13 | −.05 | −.09 | .32* | .24 | −.02 |

| 2. DDQ-M | .19 | — | .50* | .32* | .16 | −.36* | .18 | .26 | .56* | .28 | .10 | −.19 | −.08 | .35* |

| 3. AUDIT-Use | .28 | .67* | — | .47* | .19 | −.24 | .31* | .42* | .05 | .34* | .43* | −.18 | .01 | .27 |

| 4. AUDIT-Prob | .33 | .62* | .50* | — | .29 | .11 | .53* | .50* | .08 | .44* | .14 | .02 | .19 | .31* |

| 5. PANAS-PAa | .21 | −.11 | −.21 | −.07 | — | −.32* | .11 | .11 | .36* | .48* | .28 | −.38* | .59* | .43* |

| 6. PANAS-NAa | .08 | .53* | .12 | .28 | −.17 | — | .25 | −.21 | .15 | −.01 | −.54* | .64* | .77* | −.36* |

| 7. DMQ-Cope | .32 | .41* | .11 | .64* | .00 | .42 | — | .58* | .10 | .25 | .03 | .37* | .48* | .33* |

| 8. DMQ-Enhance | −.29 | .22 | .14 | .42* | .20 | .24 | .53* | — | −.07 | .26 | .19 | −.03 | .16 | .62* |

| 9. Mean Drinks | .26 | .50* | .39* | .29 | .16 | .08 | .11 | −.06 | — | .48* | −.11 | .12 | .10 | .04 |

| 10. Mean AUD | .36* | .24 | .20 | .42* | .19 | .32 | .35 | .09 | .66* | — | .01 | .15 | .11 | .18 |

| 11. Mean PM | −.13 | −.26 | −.21 | −.37* | .63* | −.33 | −.36* | −.09 | −.17 | −.27 | — | −.19 | .22 | .21 |

| 12. Mean NM | .20 | .32 | .23 | .39* | .06 | .73* | .39* | .27 | .22 | .25 | −.37* | — | .59* | −.21 |

| 13. Mean Cope | .37* | .29 | .10 | .30 | .27 | .22 | .50* | .01 | .27 | .30 | −.09 | .46* | — | −.04 |

| 14. Mean Enhance | −.12 | −.01 | .19 | .28 | .26 | −.21 | −.06 | .45* | −.23 | −.15 | .22 | −.00 | −.14 | — |

Note. Variables 1 through 8 were assessed during the screen; Variables 9 through 14 were assessed daily. Men (n = 31) are below the diagonal, women (n = 43) are above the diagonal. DDQ-M = Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire; AUDIT-Use = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Use Scale (Items 1 to 3); AUDIT-Prob = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Problems Scale (Items 4 to 10); PANAS – PA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Positive Affect; PANAS – NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Negative Affect; DMQ-Cope = Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Coping Scale; DMQ-Enhance = Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Enhancement Scale; Mean = mean value across ecological momentary assessments; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms assessed daily; PM = Daytime Positive Mood; NM = Daytime Negative Mood; Cope = Evening Coping Motives; Enhance = Evening Enhancement Motives.

PANAS was added after the start of the study; thus, these data are only available for n = 33 (n = 15 men; n = 18 women).

p < .05.

EMA Assessment and Compliance Statistics

There were a total of 1,575 days of self-monitoring in the data set. Of these days, 516 (32.76% of total days) were days in which individuals endorsed a plan to drink. However, on 62 different days, participants endorsed drinking prior to the assessment of drinking motives (i.e., daytime drinking prior to 4:00 p.m.). These 62 days were removed prior to analysis, resulting in a final analysis sample of 454 days. There were a total of 3,442 random prompts on analysis days, with participants responding to a total of 3,084 prompts (compliance = 89.60%). Participants completed 429 out of 454 morning assessments (compliance = 94.49%). Intentions to drink were assessed during the evening assessment; thus, all analysis days included an evening assessment.

Multilevel Path Analysis

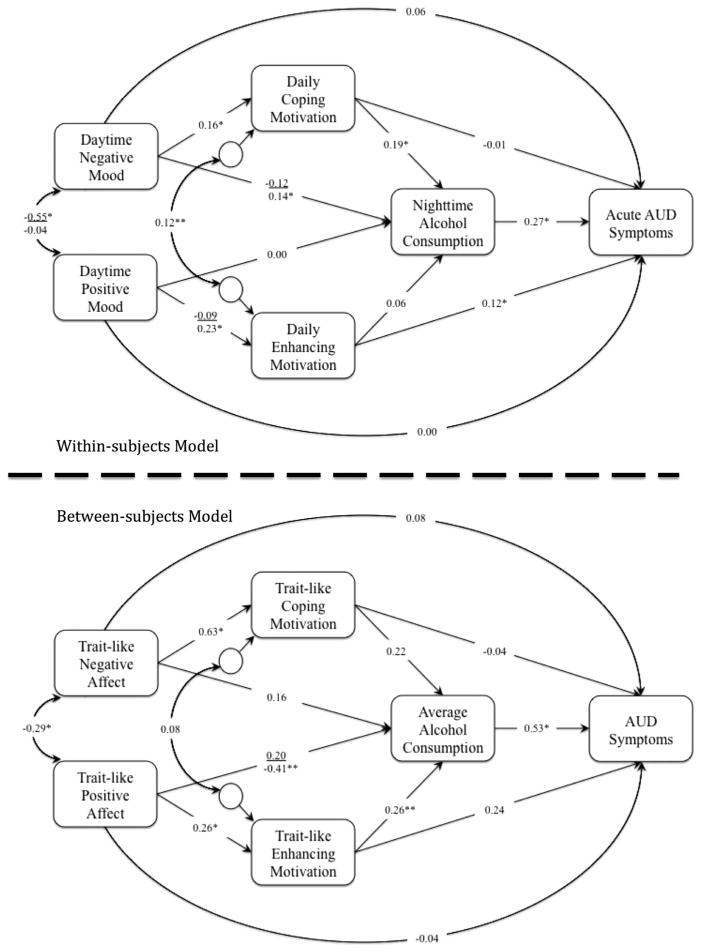

The hypothesized multigroup multilevel path model, depicted in Figure 2, was specified to test associations between daytime positive and negative mood, internal alcohol use motives, alcohol consumption, and subsequent acute AUD symptoms on planned drinking days. This fully constrained model showed reasonable fit to the data, χ2(43) = 58.88, p = .054, comparative fix index (CFI) = .925, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = .874, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .040, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) within = .071, SRMR between = .107. Examination of modification indices suggested four paths that varied by gender. These paths were sequentially freed, and the model reestimated, χ2(39) = 20.44, p = .994, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000, SRMR within = .037, SRMR between = .068. The final model, depicted in Figure 3, showed exceptional fit to the data and was a significantly better fit than the fully constrained model, Δχ2(4) = 38.44, p < .001. The four unconstrained path coefficients are listed in Figure 3, with female gender above, and male gender below, the vinculum.

Figure 3.

Multigroup multilevel path model. Women are above the vinculum. Coefficients are standardized. *p < .05. **p < .10.

Approximately half of the variance in drinking motives was at the within-subjects level (coping motive: male ICC = 0.63, female ICC = 0.61; enhancement motive: male ICC = 0.59, female ICC = 0.43). Additionally, the majority of variance in both alcohol use (male ICC = 0.09; female ICC = 0.20) and acute AUD symptoms (male ICC = 0.27; female ICC = 0.19) was at the within-subjects level. Among men, the model accounted for a significant proportion of the within-subjects variance for drinks consumed (11%, p = .006) and acute AUD symptoms (19%, p < .001). Similarly, among women, the model accounted for a significant proportion of the within-subjects variance for drinks consumed (6%, p = .050) and acute AUD symptoms (11%, p = .001). At the between subjects level, the model accounted for a significant proportion of variance in coping motives among men (23%, p = .015), and of both coping motives (40%, p < .001) and acute AUD symptoms (41%, p = .047) among women. Standardized slopes at the within- and between-subjects levels are depicted in Figure 3. Indirect and total effects are listed in Table 3 (within-subjects) and Table 4 (between-subjects).

Table 3.

Indirect and Total Effects for Men and Women at the Within-Subjects Level

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| PM → Drinks | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.000 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| PM → Enhance → Drinks | — | 0.011 | — | — | −0.005 | — |

| NM → Drinks | 0.139* | 0.030* | 0.160* | −0.117 | 0.030* | −0.087 |

| NM → Cope → Drinks | — | 0.030* | — | — | 0.030* | — |

| PM → AUD | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.037 | 0.000 | −0.012 | −0.012 |

| PM → Enhance → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.004 | — | — | −0.001 | — |

| PM → Enhance → AUD | — | 0.033** | — | — | −0.011 | — |

| PM → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.000 | — | — | 0.000 | — |

| NM → AUD | 0.059 | 0.057* | 0.114* | 0.059 | −0.026 | 0.033 |

| NM → Cope → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.008* | — | — | 0.008* | — |

| NM→ Cope → AUD | — | −0.002 | — | — | −0.002 | — |

| NM → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.052* | — | — | −0.032 | — |

| Cope → Drinks | 0.189* | — | 0.189* | 0.189* | — | 0.189* |

| Enhance → Drinks | 0.056 | — | 0.056 | 0.056 | — | 0.056 |

| Cope → AUD | −0.014 | 0.051* | 0.037 | −0.014 | 0.051* | 0.037 |

| Cope → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.051* | — | — | 0.051* | — |

| Enhance → AUD | 0.122* | 0.015 | 0.137* | 0.122* | 0.015 | 0.137* |

| Enhance → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.015 | — | — | 0.015 | — |

| Drinks → AUD | 0.271* | — | 0.271* | 0.271* | — | 0.271* |

Note. PM = Daytime Positive Mood; NM = Daytime Negative Mood; Cope = Evening Coping Motive; Enhance = Evening Enhancement Motive; Drinks = Nighttime Drinks Consumed; AUD = Acute Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms.

p < .05.

p < .10.

Table 4.

Indirect and Total Effects for Men and Women at the Between-Subjects Level

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| PM → Drinks | −0.407** | 0.066 | −0.341 | 0.202 | 0.066 | 0.271 |

| PM → Enhance → Drinks | — | 0.066 | — | — | 0.066 | — |

| NM → Drinks | 0.105 | 0.092 | 0.197 | 0.105 | 0.092 | 0.197 |

| NM → Cope → Drinks | — | 0.092 | — | — | 0.092 | — |

| PM → AUD | −0.037 | −0.107 | −0.144 | −0.037 | 0.207 | 0.163 |

| PM → Enhance → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.031 | — | — | 0.031 | — |

| PM → Enhance → AUD | — | 0.053 | — | — | 0.053 | — |

| PM → Drinks → AUD | — | −0.191 | — | — | 0.107 | — |

| NM → AUD | 0.049 | 0.077 | 0.125 | 0.049 | 0.077 | 0.125 |

| NM → Cope → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.043 | — | — | 0.043 | — |

| NM → Cope → AUD | — | −0.016 | — | — | −0.016 | — |

| NM → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.049 | — | — | 0.049 | — |

| Cope → Drinks | 0.192 | — | 0.192 | 0.192 | — | 0.192 |

| Enhance → Drinks | 0.261** | — | 0.261** | 0.261** | — | 0.261** |

| Cope → AUD | −0.033 | 0.090 | 0.057 | −0.033 | 0.090 | 0.057 |

| Cope → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.090 | — | — | 0.090 | — |

| Enhance → AUD | 0.173 | 0.101 | 0.274* | 0.173 | 0.101 | 0.274* |

| Enhance → Drinks → AUD | — | 0.015 | — | — | 0.015 | — |

| Drinks → AUD | 0.531* | — | 0.531* | 0.531* | — | 0.531* |

Note. PM = Mean Positive Mood; NM = Mean Negative Mood; Cope = Trait-like Coping Motive; Enhance = Trait-like Enhancement Motive; Drinks = Average Drinks Consumed; AUD = Mean Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms.

p < .05.

p < .10.

Within-Subjects Associations

Alcohol consumption

At the within-subjects level, daytime negative mood was positively associated with drinks consumed that night among men, and with coping motives among both men and women. Among men, there was a marginal total indirect effect from negative daytime mood to drinks consumed via drinking motives, and a significant total effect, due largely to the direct effect between daytime negative mood and drinks consumed. Among women, there was a significant total indirect effect from daytime negative mood to drinks consumed via coping motives. Coping motives had a direct positive relationship with drinks consumed that did not vary by gender. Thus, at the within-subjects level, negative mood regulation appears to be a prominent feature of alcohol consumption on planned drinking nights for both men and women. Although there was a positive association between daytime positive mood and enhancement motives among men, this did not translate into increased drinks consumed. Neither positive daytime mood, nor enhancement motives, was related to alcohol consumption, and this finding was consistent across gender.

Acute AUD symptoms

Among men, there were significant indirect and total effects between negative mood and acute AUD symptoms via coping motives and alcohol use. Among women, there was an observed simple indirect effect from negative mood to acute AUD symptoms via coping motives and alcohol consumption (p = .026), which was masked by a nonsignificant direct, and numerous nonsignificant indirect, effects. There was a significant indirect effect from coping motives to acute AUD symptoms as well as a significant direct effect from enhancement motives to acute AUD symptoms, neither of which varied by gender. Consistent with previous within-subjects research, alcohol consumption was positively associated with acute AUD symptoms.

Between-Subjects Associations

Alcohol consumption

For men and women, trait-like (i.e., between-subjects) daytime negative mood was positively associated with mean coping motives. However, consistent with several studies examining coping motives at the between-subjects level, this did not translate into increased mean levels of alcohol consumption. Though mean daytime positive mood was positively associated with enhancement motives, it was neither directly, nor indirectly, associated with average alcohol consumption. In fact, there was a marginally negative direct association (p = .091) between mean daytime positive mood and average alcohol consumption, on planned drinking days, among men. However, trait-like levels of enhancement motives did exhibit a marginal positive association with alcohol consumption (B = 0.261, p = .051), which did not differ by gender.

Acute AUD symptoms

Neither positive mood, negative mood, nor coping motives were associated with acute AUD symptoms at the between-subjects level. There were significant total effects from enhancement motives to acute AUD symptoms that did not vary by gender. Average drinks consumed were positively associated with mean levels of AUD symptoms.

Discussion

The current study used EMA to examine how mood, alcohol use motives, alcohol consumption, and acute AUD symptoms unfold throughout a planned drinking day. This study is the first to model both within-subjects and between-subjects variation in drinking motives in an EMA design, while also assessing the experience of acute AUD symptoms. Our findings lend themselves to several important areas of interest, including mood regulation models of alcohol use, the measurement of drinking motivation, and the importance of modeling phenomena (e.g., mood, mechanisms, psychopathology) both within and between persons.

Although some research demonstrates a link between negative mood, coping motives, and alcohol use and problems (Kuntsche et al., 2005; Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008), there is also considerable recent research that does not support these connections, particularly when examining mood-drinking associations at the within-subjects level. For example, in an analysis of daily diary data, Littlefield and colleagues (2012) found no link between mood, coping motives, and time to drink. In fact, in some analyses, drinking to cope actually diminished the association between negative mood and alcohol use. Similarly, in a separate EMA study, the association between negative mood and solitary drinking was stronger among those with lower coping motives (Mohr et al., 2013). These results highlight a growing problem in the motives literature, namely, that drinking to cope seems to produce alcohol-related consequences while simultaneously being, at best, not associated with use, and, at worst, inversely associated with use. This theoretical inconsistency formed the basis of the current study.

The results of the current study found support for an affect regulation model of drinking in which daytime negative mood has an indirect effect on nighttime drinking via increased coping motivation, though this was primarily a within-subjects phenomenon. In fact, negative mood was associated with coping motives at the between-subjects level, but this did not translate into increased alcohol use. Thus, on days in which individuals experienced more negative mood, they also endorsed higher rates of drinking to cope, and this translated to more alcohol use among both men and women, and greater acute AUD symptoms among men. In contrast, individuals with higher negative mood in general (i.e., trait-like negative affect) also had higher trait-like coping motivation; however, this did not result in generally higher rates of alcohol use or in greater alcohol-related consequences associated with an AUD, a finding that is inconsistent with the larger literature on coping motives.

The present results are consistent with the theoretical proposition that individuals may drink to cope to with negative mood, and that this form of drinking leads to higher rates of alcohol-related consequences. However, the findings are somewhat inconsistent with the bulk of research on negative mood, coping motives, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences. Consequently, our first hypothesis, that associations between coping and acute AUD symptoms would not involve a mediated relationship through alcohol use (a hypothesis grounded largely in the broader between-subjects literature), was not supported. Kuntsche and colleagues (2005), in a comprehensive review of the literature, indicated that coping motives are generally associated with alcohol-related consequences but seldom show direct associations with alcohol use. Consistent with this literature, the between-subjects bivariate correlations between alcohol use, alcohol problems, and coping motives, all assessed via self-report questionnaire, showed a similar pattern to those reported by Kuntsche and colleagues. However, these relationships became more nuanced, and were nonsignificant, when examined using between-subjects data gleaned from EMA reports.

In fact, between-subjects coping motivation assessed via questionnaire (i.e., the DMQ) and mean coping motivation assessed via EMA only shared 23% to 25% variance, less than coping and enhancement assessed by the DMQ share with each other (28% to 34%). In contrast, mean coping and enhancement motivation assessed in near real-time via EMA shared virtually no variance (0 to 2%), and for both men and women, were negatively, though not significantly, correlated. This suggests that these are not simply distinct ways to assess the same construct, but in fact, the two methods appear to tap two different processes. As nearly all previous research has assessed motives as trait-like constructs, this assessment method may account for at least some of the theoretically inconsistent findings. That is not to say that between-subjects drinking motives assessed via questionnaire are simply inaccurate or theoretically inconsistent. In fact, there is research showing that motives assessed in this manner do conform to theory, predicting actual consumption behavior (Kuntsche & Kuendig, 2012) as well as expected drinking outcomes following consumption (Piasecki et al., 2013). Perhaps drinking motives assessed via questionnaire are tapping into more pathological, chronic, or problematic established use patterns. It will be important for future research to identify (a) what is being assessed by questionnaire motives, (b) how these relate to motives that are assessed in real time, (c) how these two different methods of assessment relate to acute (i.e., daily) and chronic alcohol involvement, and (d) how these differences affect the theoretical understanding of drinking to cope with negative mood.

Across several studies, enhancement motives are generally associated with alcohol-related problems via alcohol use (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cooper et al., 2008; Kuntsche et al., 2005, 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill et al., 2014). Though we did find a marginal between-subjects association between enhancement motives and alcohol use, this did not translate to a significant indirect effect to AUD symptoms via use. However, enhancement motives were associated with AUD symptoms, both at the within- and between-subjects levels. This finding, too, did not conform to our original hypothesis that associations between enhancement motivation and acute AUD symptoms would operate via increased alcohol consumption. At the between-subjects level, the relationship between enhancement and AUD symptoms took the form of a total effect (though neither the direct nor indirect effects reached conventional levels of statistical significance independently). At the within-subjects level, this relationship took the form of a direct association between enhancement motivation and the experience of acute AUD symptoms. Thus, drinking to enhance positive mood on any given night may lead to higher rates of acute AUD symptoms. Consequently, over time, individuals with higher trait-like enhancement motives may be more prone to the development of an AUD, which is generally consistent with between-subjects research on enhancement motives, though the mechanisms differ.

Positive mood was only associated with trait-like enhancement motives among men, and the relationship was tenuous at best. EMA studies frequently show a positive association between positive mood and alcohol use, but we did not observe this relationship either directly or via enhancement motives. Perhaps our measurement of positive mood was not adequate to tap into positive emotions that may prompt enhancement; perhaps our assessment of enhancement motives was not adequate to capture the true nature of enhancement motivated drinking; or, perhaps this is a function of the fact that we only examine positive mood on planned drinking days. Interestingly, there is between-subjects research indicating that positive mood may act as a buffer against alcohol-related consequences (e.g., see Wray, Simons, Dvorak, & Gaher, 2012). Consistent with this finding, we found that a higher level of trait-like positive mood was inversely associated with alcohol use, but only among men. This may help to explain the theoretically inconsistent finding regarding positive mood motivated drinking. Perhaps enhancement motives measured in near-real time are actually a form of in-the-moment rash impulsivity or positive urgency (Cyders & Smith, 2008), and thus moderate, rather than mediate, associations between positive mood and alcohol involvement. This may also account for the negative and nonsignificant associations, across both levels, between positive mood and alcohol use after controlling for enhancement motives. An EMA study with a larger sample, better measures of mood and motives, and a comprehensive assessment of the facets of impulsive behavior is needed to fully explore enhancement motivation.

The current results are also potentially important in understanding the development of AUDs. Within-subject coping motives were indirectly associated with AUD symptoms via increased alcohol use, and this relationship was stronger among men. This finding is consistent with recent research suggesting differential patterns of negative mood motivated drinking across genders (Dvorak & Simons, in press). Further, drinking to enhance positive mood did not increase alcohol use, but was directly associated with experiencing acute AUD symptoms. These two associations are the opposite of that frequently observed in the broader between-subjects literature, which served as the basis of our hypotheses, in which coping motives are often directly associated with alcohol-consequences and enhancement motives are associated with alcohol consequences via use (for a review of these associations, see Kuntsche et al., 2005). Perhaps, this occurs via differential associations with AUD symptom clusters. This is an important question for future research, which highlights an interesting methodological issue associated with the measurement of AUD symptoms in real time.

Although none of this sample was assessed for an AUD, the range of AUDIT scores indicates that at least some of the sample would meet diagnostic criteria. Interestingly, the experience of AUD symptoms occurred primarily at the individual (i.e., within-subjects) level. This is consistent with the current diagnostic notion that psychopathology is polythetic. It would be interesting to examine how polythetic AUD truly is. For example, if individuals evidence multiple different symptoms across different days, with no clear symptom pattern, is this still an identifiable medical disorder? The fact that there was very little variance at the between-subjects level seems to suggest that it is not. Of course, an alternative explanation is simply that, among this fairly well adjusted college student sample, there is very little pathology related to AUD, and hence little between-subjects variance. A similar investigation in a clinical sample, or with a mix of AUD and non-AUD subjects, may provide additional insight into the nature of alcohol use pathology. From a clinical perspective, prevention or interventions that could modify daytime drinking motives, perhaps by altering outcome expectancies, and have an influence on that night’s experience of problems, is an intriguing possibility.

Despite the novelty of this study, there are several limitations worth noting. The sample comprised only college students, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to other populations. Second, the sample was predominantly Caucasian, and a more ethnically diverse sample might evidence a different pattern of results. Third, all of the days included in the analysis were planned drinking days. One has to wonder whether the between-subjects motives are tapping into broader trait-like motives across drinking occasions, or are simply tapping into stable drinking motivation when drinking is planned. Along these lines, there are issues with the assessment of motives, which were not optimal. The motive items used a single indicator for enhancement and only two indicators for coping. There is always a balance between the amount of data that can be gathered using EMA and the demand required of participants. Given the establishment of “state” motivations here, future research could examine more comprehensive assessments of motives at the event level. Additionally, it is worth noting that the motives assessed, while temporally preceding alcohol use, may not fully capture drinking motivation. It is possible that motives for drinking changed between the time they were reported and the time the person actually began drinking. Consistent with this notion, 40% of drinking episodes were unplanned and thus had no motives assessed with them. Furthermore, it is quite possible that motives influence the likelihood that a person will drink. The current study fails to capture this, as we only assessed drinking motivation once a person reports drinking intentions. This represents a challenge, as it is unclear when (or if) to assess motivation to drink when there is no intention to drink. Perhaps future research could assess motives at multiple time points (e.g., evening prior to drinking regardless of intentions, at a self-initiated drinking onset assessment, retrospectively as soon as an individual acknowledges drinking, or the following day). Nonetheless, the current findings suggest there is much to be learned by examining event-level drinking motivation. Finally, we excluded a number of days due to temporal precedence mood, motives, and drinking (e.g., drinking before being asked why they are drinking).

Conclusions

Though our findings did not conform to the original hypotheses grounded in between-subjects research, the results do generally support an affect-regulation model of drinking on planned drinking days, in which negative mood is associated with nighttime drinking via adoption of coping motives. In addition, coping motives (among men and women) and negative mood (among men) are indirectly associated with the experience of acute AUD symptoms. Furthermore, enhancement motives, at both the day and trait levels, are associated with AUD symptoms irrespective of positive mood. At the broadest level, the current findings suggest that a conceptualization of drinking motivation as variable, within person and across time, may be necessary to reconcile the theoretically inconsistent findings throughout the literature.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a faculty start-up package from North Dakota State University (NDSU) to Robert D. Dvorak. NDSU had no other role other than financial support. This research was supported in part by a T32 AA007459 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Anne M. Day) and Grant T32 AA018108 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Matthew R. Pearson). Author order corresponds to their respective contributions on the project. All authors have reviewed and agreed upon this draft of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robert D. Dvorak, North Dakota State University

Matthew R. Pearson, University of New Mexico

Anne M. Day, Brown University

References

- Arbeau KJ, Kuiken D, Wild TC. Drinking to enhance and to cope: A daily process study of motive specificity. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Todd M, Conner TS, Tennen H. Drinking to cope with negative moods and the immediacy of drinking within the weekly cycle among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:313–322. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Aharonovich E, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Adult transition from at-risk drinking to alcohol dependence: The relationship of family history and drinking motives. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney MA, Armeli S, Tennen H, Affleck G, O’Neil TP. Positive and negative daily events, perceived stress, and alcohol use: A diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:788–798. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe S, Jackson M. Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:485–501. doi: 10.1037/a0012592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LM, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.4.2.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demartini KS, Carey KB. Correlates of AUDIT risk status for male and female college students. Journal of American College Health. 2009;58:233–239. doi: 10.1080/07448480903295342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demartini KS, Carey KB. Optimizing the Use of the AUDIT for Alcohol Screening in College Students. Psychological Assessment. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR, Doyle SR, Longabaugh R, Greenfield SF. Concurrent validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and AUDIT zones in defining levels of severity among out-patients with alcohol dependence in the COMBINE study. Addiction. 2006;101:1696–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Simons JS. Daily associations between anxiety and alcohol use: Variation by sustained attention, set shifting, and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0037642. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Simons JS, Wray TB. Alcohol use and problem severity: Associations with dual systems of self-control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:678–684. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM–IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire–Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: A ten-year model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:190–198. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Predictors of drinking immediacy following daily sadness: An application of survival analysis to experience sampling data. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1054–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Galloway CA, Feagans LA. Coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:344–353. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalodner CR, Delucia JL, Ursprung AW. An examination of the tension reduction hypothesis: The relationship between anxiety and alcohol in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:649–654. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, Galanter M. Self-regulation and self-medication factors in alcoholism and the addictions: Similarities and differences. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Kuendig H. Beyond self-reports: Drinking motives predict grams of consumed alcohol in wine-tasting sessions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:318–324. doi: 10.1037/a0027480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper ML. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Talley AE, Jackson KM. Coping motives, negative moods, and time-to-drink: Exploring alternative analytic models of coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1371–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Vergés A, Rosinski JM, Steinley D, Sher KJ. Motivational typologies of drinkers: Do enhancement and coping drinkers form two distinct groups? Addiction. 2013;108:497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Roberts LJ, Cressler SO, Metrik J, Neal DJ, Marlatt GA. Psychometric properties of alcohol measures. 1998 Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Hromi A. Daily interpersonal experiences, context, and alcohol consumption: Crying in your beer and toasting good times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:489–500. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, Carney MA. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Brannan D, Wendt S, Jacobs L, Wright R, Wang M. Daily mood-drinking slopes as predictors: A new take on drinking motives and related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:944–955. doi: 10.1037/a0032633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus statistical modeling software: Release 7.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Cooper ML, Wood PK, Sher KJ, Shiffman S, Heath AC. Dispositional drinking motives: Associations with appraised alcohol effects and alcohol consumption in an ecological momentary assessment investigation. Psychological Assessment. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0035153. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge PC, Sher KJ. Heavy drinking from the freshman year into early young adulthood: The roles of stress, tension-reduction drinking motives, gender and personality. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:457–466. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. An affective and cognitive model of marijuana and alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1578–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–171. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00213-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G. A daily diary validity test of drinking to cope measures. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:303–311. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Park A. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: Cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:282–292. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affective Schedule. University of Iowa; 1999. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Gaher RM. Trait-based affective processes in alcohol-involved “risk behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]