Abstract

Family members in the United States, especially mothers, are frequently caregivers and provide housing for their adult relatives and children with mental illness. They often do so with little support from the mental health system. The purpose of this analysis was to explore mothers’ experiences related to housing options available to their adult children who have a mental illness and a history of violence (MIHV) toward the mothers. The results of this study reveal a complex mixing of desires, feelings, internal factors and external forces experienced by mothers of adult children with MIHV when considering whether or not these children can live in their homes. The findings from this study illuminate needs for greater familial involvement in mental health treatment decisions, respite for caregiving families, and housing as a crucial element of a comprehensive mental health treatment plan.

Keywords: decision making, families, caregiving, grounded theory, mental health and illness, violence

Although individuals with a mental illness are no more likely to be violent than the general public, when they do become violent, they are typically hospitalized. Psychiatric hospitalization, initiated for any reason, is generally for a short period, and average length of stay in psychiatric hospital based care is three to five days (Bostrom, 2007). When not hospitalized, roughly half of the adults with a severe mental illness live with their families (Fontaine, 2009). Additionally, if an individual with mental illness becomes violent, family members are most often the victims, especially mothers (Estroff & Zimmer, 1994; Steadman et al., 1998; Straznickas, McNeil, & Binder, 1993). Even psychiatrically hospitalized individuals who have been violent toward family members return home in most cases (Binder & McNeil, 1986). Their mothers might be at particularly high risk for revictimization in light of evidence that the majority of psychiatric patients who were violent both before and after hospital discharge attacked the same person each time, typically a family member (Tardiff, Marzuk, Leon, & Portera, 1997).

Since the deinstitutionalization of state psychiatric hospitals in the late 1950s and 1960s (Urff, 2004), family members, particularly mothers, have assumed whether by choice or by necessity, greater caregiving roles for their relatives with mental illness. They have done so with little support from the mental health system (Biegel, Milligan, Putnam, & Song, 1994; Saunders, 2003), despite evidence based treatment recommendations to involve family members in psychosocial education (Dixon, 1999). Unfortunately, increased caregiving responsibilities have been associated with increased psychological distress among familial caregivers (Saunders, 2003). Family members of individuals with mental illness report feeling isolated, seeing no resolution to their situations, maintaining constant vigilance, and living with fear and anxiety while wishing to maintain the safety of their ill relatives (Champlin, 2009). Thus, families attempting to provide in-home care for their mentally ill relative who has a history of violence might need more, or different, support than families whose relative does not have such a history. The results presented here describe the feelings and desires experienced by mothers who have been victims of violence perpetrated by their adult children with mental illness in combination with internal factors and external forces that influence their decisions of whether or not they will allow their children to live in their homes.

Literature Review

Burden among caregivers of individuals with mental illness has been the focus of much research (Bibou-Nakou, Dikaiou, & Bairactaris, 1997; Horwitz & Reinhard, 1995; Jungbauer, Wittmund, Dietrich, & Angermeyer, 2003; Stueve, Vine, & Struening, 1997; Winefield & Harvey, 1994), partly because it has been linked to behavior problems, including violent behavior, of individuals with mental illness (Biegel et al., 1994; Jungbauer et al., 2003). The experience of caregiver burden, and associated disruptive behavior, combined with a lack of support from the mental health system creates a very difficult situation for caregiving mothers who are attempting to care for relatives with mental illness in the home. If families reach a point where they are unable or unwilling to continue caring for their ill relatives, caregiving responsibilities would be shifted back to an already overburdened mental health system. If no services or support is available, homelessness of the relative with mental illness might be the result.

It is estimated that nearly two million adults in the United States are homeless (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2006a), and 22% of homeless individuals have a mental illness (National Coalition for the Homeless, 2006b). Consequently, recent evidence based care recommendations for homeless individuals with a mental illness have included not just mental health treatment but housing support as well (Young & Magnabosco, 2004). Housing is a critical element in reducing psychiatric hospitalization rates (Rosenfield, 1990). In the absence of quality housing, mental health treatment and rehabilitation for adults is jeopardized (Moxam & Pegg, 2000; Stroul, 1989). Indeed, Baker and Douglas (1990) reported a causal relationship between appropriate housing and quality of life and global functioning in consumers of mental health services.

If individuals with a mental illness are not homeless or living with their family, they might live independently or in structured living facilities. Living independently is typically more desirable than structured living among individuals with mental illness (Fischer, Shumway, & Owen, 2002; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Tanzman, 1993). A study of group home versus independent living among individuals with mental illness found that people assigned to group homes experienced more days homeless than did those assigned to independent living during the study period (Goldfinger, et al.). However, family members, including caregiving mothers, and mental health professionals are more likely to believe that structured living arrangements are more appropriate than independent living (Rogers, Canley, Anthony, Martin, & Walsh, 1994; Wasow, 1993).

Mothers are often primary caregivers for their adult children with mental illness. Nonetheless, the family’s home has not been included as an option in studies of family member housing preferences for relatives with mental illness. For example, one of the few studies examining family and client residential preferences and perspectives included options for housing such as independent living, supported housing with visitation from on-site staff, and housing with 24-hour on-site support as options, but it did not include the family’s home as a potentially preferred housing option for the clients or their family members (Friedrich, Hollingworth, Hradek, Friedrich, & Culp, 1999). Also, other studies on the effect of housing arrangements on homelessness (Goldfinger et al., 1999) and functioning (Browne & Courtney, 2004) only included comparisons of individuals living independently and those living in staffed group or boarding homes. Because many individuals with mental illness receive care from and reside with family, studies addressing housing preferences and the effects of various housing scenarios on clinical outcomes could be improved by the inclusion of living with family as an option.

The purpose of this analysis was to explore mothers’ experiences related to housing options available to their adult children with mental illness and a history of violence (MIHV). The results of this study illuminate a complex mixing of emotions and desires with internal factors and external forces experienced by mothers of adult children with mental illness and a history of violence when they consider whether or not these adult children may live in their homes.

Method

Design

Grounded theory methodology is useful for understanding social processes and the ways in which individuals understand and manage their lives in ever-changing environments (Streubert Speziale & Rinaldi Carpenter, 2003). It recognizes the multidimensionality of human existence and our ability to make sense of our lives and world (Charmaz, 2003). Therefore, grounded theory methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used here to guide data collection and analysis.

Procedures and Setting

After approval was obtained from the human subjects review boards at two institutions, the purpose of the study was explained to charge nurses and social workers on two locked adult inpatient psychiatric units in California. After training, these individuals served as recruitment staff for the study. One study site was a small unit at a large nonprofit medical center. The other study site was a large unit at a free-standing, for-profit psychiatric hospital. Recruitment staff identified patients with a known history of violence toward their mothers and contacted the mothers, explained the purpose of the study, invited them to participate, and provided them with the telephone contact information of the first author. Participants also were recruited at one meeting of the local National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter.

Participants

As potential participants called and inquired about the study, they were screened for eligibility. However, recruitment staff noted that the topic of violence was considered taboo and mothers’ desires to protect the reputations of their sons and daughters seemed to override desires to confide personal experiences dealing with an adult child with MIHV. Additionally, mothers were often overwhelmed with their hectic lives and how little time they had available. Thus, only 14 women called to inquire about the study and of them, only eight met inclusion criteria. Mothers were eligible if they had a biological, adopted, or step-child over age 17, who had been violent toward them and who had a DSM –IV Axis I psychotic, mood, or anxiety disorder without a comorbid personality or substance abuse disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Mothers age 65 or older were excluded to avoid a situation that could result because of elder abuse laws in California requiring nurses to report violence toward persons aged 65 or older. Because a central element of the study was a history of violence perpetrated by a son or daughter with mental illness the topic would be discussed during interviews, potentially creating a conflict that a mother could not have foreseen. We felt it was ethically irresponsible to recruit such women into the study, inviting them to discuss their experiences of violence, only to find that we were obligated to report the incident once it was shared. The first author is a monolingual English speaker and conducted all interviews; therefore, participation was limited to mothers able to be interviewed in English.

Six of the 14 women who called did not meet inclusion criteria because of current drug use of the adult child with mental illness, mother’s primary language was other than English, or mother’s age was more than 65 (two were in their 80s) so the final number of participants for this convenience sample was eight. The mothers’ ages ranged from 42 to 60. Half of the women were uninsured. Two of the mothers had not graduated from high school, three had completed high school, and the other three had some college education. Half of the women reported that their monthly income was not adequate to meet their needs. Three women reported that their adult children with MIHV were living with them at the time of the interview. The eight women had a total of nine adult children with MIHV.

All of the adult children had a reported psychotic disorder (four schizophrenia, three schizoaffective disorder, one bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and one psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). The adult children ranged in age from 20–38. Six of the adult children were men, three were women. With the exception of one adopted nephew, all of the adult children were biological sons or daughters of the mothers interviewed. Two of the adult children were uninsured. Three of the children had not graduated from high school, five had graduated from high school, and one had some college education.

Data Collection

One or two interviews were conducted with the mothers in a safe and private location of their choosing. Written informed consent was obtained and sociodemographic information was collected from the women prior to the interview. Each interview lasted 1.5–2 hours and was audio-taped. Participants received $20 at the end of each interview. The open-ended interviews were conducted using a guide we developed to elicit mothers’ experiences of getting help when they were victims of violence perpetrated by their adult children with mental illness; results have been reported elsewhere (Copeland & Heilemann, 2008). Although not originally on the interview guide, the subject of housing options for their adult children was raised by each mother who participated in the study; therefore, the topic was explored further as data collection and analysis continued, consistent with grounded theory research methodology. Probes were developed and used to explore the mothers’ perceptions of treatment needed by their adult children, including housing, and their experiences with different housing options for their adult children.

Observational, theoretical, and methodological field notes were written following each interview to record details about the behavior of the participant, the interactions with the women, and general reactions to the interviews. This often led to the development of new questions for future interviews (Levy & Hollan, 1998). Consistent with grounded theory techniques, participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis occurred concurrently (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and verified against the audiotapes for accuracy. We independently analyzed each transcript before engaging in collaborative analysis. Transcripts were coded line by line using techniques articulated by Strauss and Corbin (1998). Open coding was used to break each sentence into codes that identified processes, similarities, and differences present in the data. These codes were related to one another conceptually and grouped together as categories. Axial coding involved more abstract analysis including identifying properties and dimensions of the categories and articulating relationships between the categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We both comparatively analyzed existing and incoming interview data to illuminate and expand developing categories including dimensions and properties of the categories, and to explore relationships between categories. With a small convenience sample of eight participants, saturation was not the goal of analysis. Rather, depth of understanding of the process experienced by these eight women and the various elements that complicated the process of confronting housing dilemmas were the focus. Throughout the independent and collaborative coding and analysis, an audit trail was created by using notes and memos allowing self-reflection and critique related to our assumptions about the phenomenon and descriptions of the interviews.

Results

The way mothers understood their decisions regarding whether or not to allow their adult children to live in their homes was influenced by their day to day experiences. On one day, the idea of allowing the adult child to live with her might have been an option, but if the child became violent the next day, the situation would need to change because the meaning of having the adult child in the home would have changed. Mothers of adult children with mental illness and a history of violence (MIHV) often were faced with deciding whether or not to allow their adult child to live in their home during a period of the child’s homelessness or immediately post hospitalization. All of the mothers in our sample wanted stable long-term placement for their adult children, and many wanted their children hospitalized long-term to optimally stabilize their mental disorders. However, to have their children hospitalized, most often it would have to be done against their will. For this, the adult children with MIHV needed to be imminently dangerous, or the mothers needed an existing court order, or conservatorship of the adult child. Several of the women wanted to be their adult child’s conservator, but despite their efforts, none were able to accomplish this.

In California, in order for a person to be conserved, he or she must be gravely disabled as a result of a mental disorder; the definition of grave disability holds that the person is unable to independently provide food, clothing and shelter for themselves. A petition must be filed with the court, typically by a psychiatrist, and a legal hearing is held to determine whether or not conservatorship is necessary. Depending on the stipulations of the conservatorship, a conservator has the authority to determine if, when, and where involuntary treatment occurs, for what length of time, and whether or not involuntary medications can be administered. Conservatorship lasts one year at which time the need for ongoing conservatorship is assessed (California Welfare & Institution Code § 5350, 2009). No doctor known to any of the women in our sample was willing to file a petition for a conservatorship hearing. Over and over, hospital staff told mothers that their adult children did not need a conservator.

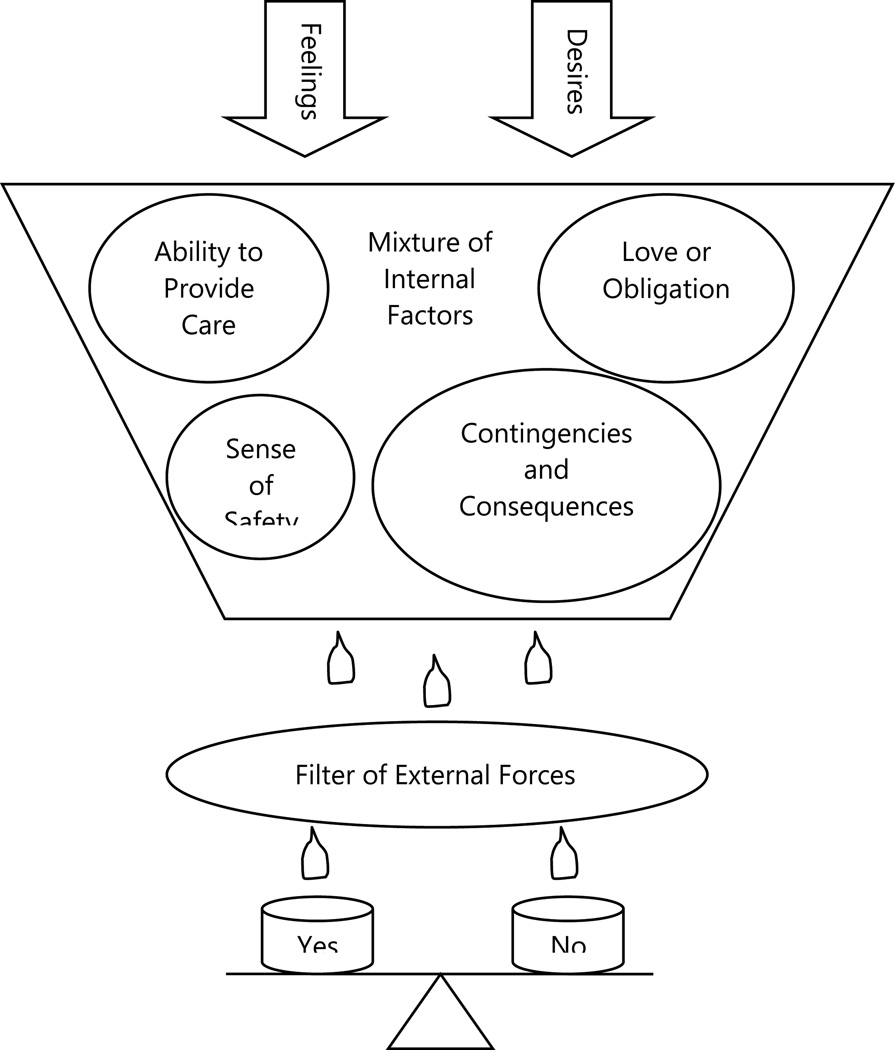

Therefore, mothers were faced with having to make a decision about allowing their adult children with MIHV to live in their homes. This decision making process occurred in the context of ever-changing, often conflicting, feelings and desires that helped inform the mothers’ understanding of four additional internal factors that influenced the process. These internal factors included the mother’s sense of safety, her perceived ability to provide care for her adult child, determining contingencies and imposing consequences, and maternal love or obligation.

The influence of these internal factors mixed together with feelings and desires in different ways for different women. Eventually, all of these internal experiences were filtered through a network of external forces including whether or not their children refused placements offered to them, the quality of available placement options, and advice received from others. Together, the internal experiences and external forces fueled a complex and ever changing decision making process regarding whether or not mothers would allow their adult children with MIHV to live in their homes, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ decision making process regarding whether or not adult children with MIHV can live in their homes

Mothers’ Desires

The mothers in this sample discussed several desires they had for their adult children with MIHV in the context of their child’s condition. Most of the women mentioned a progressive deterioration in their adult child’s ability to function. As one woman shared, “the older she’s getting the worse it’s getting. I don’t think it’s getting better, I think it’s going more downhill than it is uphill.” While the mental health system’s criteria for successful treatment of the adult children was that they were no longer threatening or violent, the mothers’ perceptions of successful treatment were different. They wanted their adult children’s mental disorders to be stabilized so that they would experience an improvement in their day to day functioning, an increased ability to maintain their independence, an improvement in their overall health, the potential to achieve happiness that was otherwise absent, and an ability to make friends or find a mate.

The route to stabilization that the women most readily identified was long term mental health treatment involving more than medication; it also included consistency in their adult children’s living environment. These women perceived housing as integral to their adult children’s long term prognoses. One woman stated, “I got involved basically to help him have a place to live because I know that in a state of mind when he feels pressure about not having a place to live that’s when he goes totally off.” One mother said of her two adult children with MIHV,

I’m hoping that sometime in the future they can live somewhere where they’re well taken care of without me being the only caregiver 100% of the time, but I don’t know if that’ll happen or not. I would hope it would, but I kind of doubt it.

The women also wanted their adult children to accept and/or want the treatment that was available to them. Although the adult children could not be forced into treatment, mothers believed that any mental health treatment would be beneficial to their adult children. The adult children, however, often lacked that insight and refused available treatment.

Greater independence for their adult children was a goal for every one of the mothers. In each case, however, total independence was not a possibility, at least at the time of the interviews. Most of the children had tried to live independently but each had failed in his or her attempts at independent living and ended up either hospitalized or homeless. The children were too impaired to be independent. Even the mother of the only child who was stable in board and care placement said, “He’ll say, ‘I’m so independent I’m ready to move on.’ And in his mind that’s what he thinks. But he’s nowhere near it.” Mothers wanted their children to be more independent because they thought it would be best for their children, but they also wanted their children to be more independent for their own sakes.

In addition to their desires for their adult children, the women expressed desires they had for themselves. They described their day to day lives as “going around and around in circles” with their adult children with MIHV. Their lives were characterized by struggle and frustration. They desired a break from their oftentimes futile attempts at getting their adult children mental health treatment they perceived as adequate. They desired respite from the caregiving responsibilities that were forced on them because of the lack of adequate treatment for their children. They desired assistance, affirmation, and validation from the mental health community for their sacrifices and caregiving efforts. As primary caregivers for their adult children they desired more opportunity to participate in mental health treatment decisions, if not more rights related to mental health treatment decision making affecting their adult children.

“They don’t listen to me” was a common description of mental health providers. One mother described her discussions with doctors by saying,

They’re not willing to help me. I keep telling them and telling them … I’m not getting nowhere. I’m the one who’s struggling with her … but they don’t listen to me. They drown me out because well she has her rights or whatever and it frustrates me…. I’m only interested in my daughter’s health and it just frustrates me that they don’t listen.

Mothers reported that mental health professionals automatically assumed that they were not only willing and able to care for their adult children with mental illness, but to provide housing too. In addition to making personal sacrifices to provide a safe place for their children, the women did so with no perceived appreciation from their children and no assistance from the mental health system. Their children were unaware and/or ungrateful for the care their mothers provided for them, and the mental health system provided no compensation or support. As one woman shared,

I don’t think my daughter even thinks about it, that we’ve tolerated her and have put up with her for many years and I don’t even think she’s, I think she’s very clueless about that. You know, that it doesn’t even dawn on her to even think about that part. We’ve given her shelter, a home.

The mothers were not seeking gratitude as much as they were admitting a desire for some acknowledgment of their efforts from anybody, their children or the mental health community.

The women also wanted time and energy to devote to themselves. At this stage in their lives, the mothers had hoped they would be moving toward retirement when they would visit with their grandchildren and relax with their spouses at home. They had expected that their children would be living lives of their own, independent of them. Instead, however, these mothers were still engaged in active parenting. One woman said,

It’d be nice for her to be in a home, a nice home, make her friends if she can. She’s capable of doing that. Have her own life, come and visit us. It would be like ideal, but she just won’t do it so she’s becoming like a thorn in our side because we just don’t want her around…. Maybe he [the mother’s husband] could pay attention to himself and I could pay attention more to myself, if we could just get her settled somewhere then we could all have lives.

Mothers’ Feelings

Mothers described a variety of emotions associated with their experiences as caregivers for their adult children with MIHV. They did not describe any affirmative emotional states. Rather, they described feeling powerless, voiceless, anxious, frustrated, isolated, tired, desperate, trapped, guilty, worried, scared, sad, grief, trapped, unhappy, a sense of loss, and confused.

When their children were at home, the women were unable to focus attention on their own needs. One mother said, “It’s draining to me. It keeps me from doing what I need to focus on doing.” Their feelings were of grief for the loss of the life they had envisioned for their children and feelings of being cheated out of the life they had expected for themselves. During periods when their adult children were not living with them, the mothers realized how tired they actually were and how much they needed rest. One mother, whose son had recently been placed in his first board and care, said about life without him in her home, “I’m less stressful. I’m kind of tired. I think I was just numb then. I’m kind of trying to rest ‘cause I think I was just numb when I was taking care of him in that situation.” Another woman said that when her daughter was in the hospital, “It’s so peaceful and nice and quiet. It kind of makes me feel guilty, but it’s nice. We both feel guilty about it. We wish we could help her, but we can’t.” A sense of guilt and helplessness intruded on this woman and her husband’s lived experience even during “nice” times.

Mothers also felt a tremendous sense of responsibility to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the children in the years ahead as they aged. Because none of the adult children with MIHV were capable of living independently and the mothers had assumed primary caregiving roles for them, they feared for their children’s future once they were deceased or no longer capable of providing care. As one mother expressed, “I’m not gonna live forever. Who will take care of her then?”

The mothers experienced sadness and grief when watching their adult children struggle with mental illness. Many of the adult children experienced disturbing auditory hallucinations. One mother observed that her son, “hurts terribly inside…. In my heart I know he’s struggling.” Refusal to bathe or eat and extreme isolation were other common symptoms described. One mother described her daughter’s existence as, “not living, it’s not life, it’s not happiness. I see her crying…. You can see the pain, the pain in her. That disturbs me.”

The sadness of watching their children suffer was exacerbated by the mothers’ inability to find “that little loophole or that little system that I can get in, or the right connection, somebody to really help me out with this.” They repeatedly described their frustrating attempts at getting their adult children adequate mental health treatment as “going around in circles.” They were desperate for somebody, anybody to help them help their children. The mothers witnessed the “vicious cycle” of their adult children’s decompensating mental health. They felt voiceless when attempting to communicate their concerns with mental health providers. They felt helpless and powerless to affect any change. There was guilt associated with the mothers’ inability to access treatment for their adult children. These feelings of fear, sadness, grief, guilt, helplessness, and frustration were not experienced in isolation of one another, but compounded one another.

Internal Factors

These desires and feelings informed the ways that mothers understood four critical factors experienced internally; factors that influenced their decisions about which housing arrangement was most suitable for them and their adult children with MIHV at various points in time. The four internal factors included the mother’s sense of safety for herself and her adult child, her perception of her ability to provide care to her adult child, her ability to determine contingencies and impose consequences, and her sense of maternal love or obligation. The mothers’ understandings of these factors mixed together. Each internal factor played a role in the mothers’ decisions but were experienced and prioritized differently by different women.

Sense of safety

Mothers were often in a position in which the decision to allow their adult children with MIVH into their homes involved choosing between protecting themselves and protecting their children. Having been victims of violence perpetrated by their adult children in the past, the mothers always were faced with the potential threat of future violence if they allowed the children back into their homes. If the adult children were not allowed back into the mothers’ homes, the children risked potential victimization on the streets. One mother, whose child’s safety superseded her own said, “I wasn’t even thinking about my interests, I was thinking about his.” Another mother said,

I don’t think he can survive on the street…. We [the mother’s family] have just been afraid that somebody’s gonna kill him or hurt him and he’s out there at all times of night…and if he stays out on the street, somebody’s gonna kill him or he’s gonna do something.

Alternately, some mothers decided that to maintain their own safety, their adult children could not return home. One mother said of her daughter, who was being released from a hospital,

The social workers would tell me, “We try to place her but she doesn’t want to be placed. We’re just going to let her out.” I go, “Don’t let her out in the streets. She doesn’t know how to take care of herself.” “Oh well, it’s our obligation to.” ”Fine, okay then fine, tell her we’re not gonna take her back.” We got to the point where we took her back many, many times and she would attack me.

Such decisions were difficult for mothers to make because they knew that it meant their children would likely be homeless and vulnerable to victimization themselves. Either choice felt like a trap.

Mother’s perception of her ability to provide care

Most often, when the adult children with MIHV were at home the mothers provided around-the-clock care. Several women did not work because their children needed constant monitoring and they chose to stay home to provide care. For some, however, as money ran out, this option became less feasible. Mothers also eventually reached a point where their caregiving was “too much” and they decided that they needed “a break.” One woman shared, “Everyone said, his doctors said you need respite, you really do, but nobody wanted to help me.” No formal or informal respite care existed to temporarily relieve mothers of their caregiving responsibilities. It was not merely routine caregiving that caused mothers to desire respite. During periods of decompensation in the past, the adult children had exhibited violent behavior directed toward their mothers. The only opportunity for mothers to experience a break from their caregiving responsibilities was if their children did not live with them.

Additionally, the level of care or supervision the children required often exceeded what mothers were able to provide. They recognized that they were not professionals and knew their limitations in their abilities to provide care for their children. One mother said,

He would call, and call, and call and I knew that he was in a condition where he couldn’t stay at home because he needed supervision as far as those meds and stuff and he needed a doctor constantly looking after him and he needed someone to you know to constantly give them to him.

One mother, who thought that she had done everything she could while caring for her daughter at home, decided to throw her daughter out of the house as a last resort. She had exhausted all available services that she was aware of but this did not provide nearly enough support to care for her daughter at home during periods of decompensation. She said,

I thought about it and thought about it and I said to myself, “Well, if this is what it takes, hopefully nothing bad happens to her.” But yes I’m willing, I’m willing to let her go. It was tough for me but I want to do the right thing for her. If this is what it takes to get help finally.

She hoped that by allowing her daughter to be homeless she would come in contact with or become eligible for services not otherwise available.

Determining contingencies and imposing consequences

Most of the women were willing to allow their adult children to live with them under certain circumstances such as when they were “not sick,” for example, when they were compliant with their medications/treatment, or when they were willing and able to comply with house rules and were not violent. Several women cited their children’s inability or unwillingness to do what she and her partner told them to do, as a reason they could not allow their adult children to stay in their homes. One mother said of her son,

I thought maybe he could stay here and we’d work things out, but [my son] had developed habits. He’s not compliant, he’s intrusive. I realized that we have different ideas of living. I had told him the rules and regulations of the household…. I didn’t feel safe in a sense.

For some mothers, not allowing their adult children back into the house was understood as imposing a consequence resulting from the child’s inability to follow rules in the home. When another woman’s daughter wanted to return home from the hospital she said,

We told her, “You got yourself in this predicament, you just stay there.” You can’t have a person around here living with you like that. Where can a person live like that? She has to have the consequences. I’m sorry and her consequence is that she can’t live here. And we’re sticking to it. It’s taken all this time for us to finally say no to her.

Typically it took years of disruptive and dangerous behavior before imposing this consequence.

Maternal love or obligation

The women knew that no one was connected to the children like they were as mothers. For most of the mothers, motherhood did not end when their children with MIHV turned 18. The mothers still felt ultimately responsible for their children’s wellbeing. No doctor, social worker, police officer, or sibling had that same responsibility. One mother shared, “I’m supposed to be mom and I’m supposed to take care and fix things.” Some of the spouses shared this sense of responsibility, but not all of them. One woman’s husband threatened to get a restraining order against her son. This woman had a great deal of resentment toward him for putting her in a position to make a choice between him and her son and described his threat as “slamming my face, putting a knife in my heart.” This mother attempted to pay for an apartment for her son. When she could no longer afford it, she slept in a car with him until he agreed to be hospitalized.

One woman said of her daughter, “She’s calling me from the bus station, so what am I supposed to do? What do you do? My husband and I go, ‘What do we do?’ Alright, we went to go get her and brought her back.” Days later this woman’s daughter assaulted her once more. Another woman described the difficult position she was in by saying,

Because you can’t sleep in a comfortable bed in a warm house, your son sleeping in the street. Who will be happy that way? It’s not easy, it’s not even easy. But it’s a very miserable life that way…. If he don’t have a place to go, what do I have to do? Leave him outside in the cold?

On learning that her daughter was homeless, one woman left her own home and other family members and temporarily stayed in a motel with her daughter. She was not willing to allow her daughter back into her house but was not willing to have her out on the streets alone either.

External Forces

As the desires and feelings of the mothers became mixed with internal factors including safety, care giving ability, consequences, and maternal love, eventually this mixture was filtered through a crisscrossing of external forces that were outside of the woman’s control. These external forces included the adult children refusing or leaving placement in board and care settings, the quality of available placement facilities, and advice received from others.

Adult children refuse or leave board and care placement

Most of the adult children with MIHV either refused board and care placement or left shortly after arriving at a placement site. One mother who was unable to work because she stayed home to care for her son who had left his board and care facility said,

He left there so he was on the street and I really was worried to death. I really was worried about that, but he said he wanted to come home, but I knew it wasn’t the best thing. I explained to him … that “even if you came back, if you came with me, it doesn’t make sense, if I can’t pay the rent then we’ll both be on the street. Why don’t you just stay there and you just, can try to maintain and hold on there until I get myself together … and then we’ll talk and when you get well, we’ll talk.”

As adults, in addition to refusing mental health treatment, the children had a right to refuse placement in any setting. The mothers had no control over their children’s refusals. The children’s refusals, however, frequently resulted in homelessness at which point the mothers needed to decide whether or not to allow the children back into their own homes.

Quality of available placements

Mothers complained about the conditions of board and care facilities and group homes in which their adult children with MIHV had been placed, describing the sites as “atrocious” and “extremely horrible.” One woman said,

I had to pull her out of there because one of the people that works there was threatening to kill her, and I know it’s true because I talked to another staff member who actually heard him say it so I had to pull her out…. I just can’t put her in jeopardy like that. I don’t want them in a place where they’re not being taken well care of and where people are mean, even the staff. It’s just, I just can’t handle it. I get too upset.

Drug use at board and care facilities was also problematic in these mother’s experiences. One woman whose daughter walked away from a board and care facility said,

I called the place up and I said, “My daughter is supposed to be there, there was an arrangement for her to show up over there, but she’s saying that there’s drugs.” And the lady said “Yeah.” “What kind of place is that?” I said. I don’t understand they’re sending her to a place with drugs, so I kept her. That’s it, I don’t want her to go to something like that, nor do I want her to go to skid row.

The mothers had no control over the cleanliness or safety of any living environment other than their own homes. Dissatisfaction with the quality of available housing options, by either the adult children or the mothers, was often a catalyst for the mothers to consider allowing their adult child to return to their homes.

Advice from others

Mothers were given advice from mental health professionals, police, and family members. Most of the advice they received was perceived as unhelpful. Nobody advised the women to allow their adult children with MIHV to remain in the home with them. Social workers and doctors sometimes advised the mothers that there was nothing more they could do for their children at home and advised board and care placement. One woman said,

It came up when he was in the hospital. I really wasn’t gonna do it at all, but one of the workers at one of the programs he was going to said, “you know what, you need to put him in a board and care because there’s no more you can do, you’ve done all you can do, you need to put him in board and care.”

This advice was only helpful when the adult children would accept or stay in board and care placements.

Other family members, fearing for the mothers’ safety, begged the women not to allow their adult children with MIHV to return home. One mother said,

When I would be here alone, [my sister] would come and stay with me ‘cause she would say, “I’m so afraid to leave you. I’m afraid what’s gonna happen. Please don’t let her come home.” Everybody that I talk to doesn’t want her to come home. And I said, “Well, you know, she’s my daughter, I love her.”

The police, and occasionally mental health professionals, advised the women to put their children out on the streets. For the mothers, this was harsh advice that was not perceived as useful. As one mother shared,

I don’t like it when they tell me “throw her out, let her in the street.” I mean I’m talking about the workers, people from the hospital. This is what the county says, “She’s an adult, throw her in the street.” I can’t. I don’t want her to be homeless. I want her to have a place, a safe place. I can’t do that. I just can’t throw her out knowing that she’s just walking around all day or something like that I just can’t. So maybe I am having a hard time, but that’s not the answer that I want … I want her [to have] a safe place and I want her to get the treatment that she needs.

The advice of others was not taken in by the women. It remained an external force. The mothers were situated within a mixture of their desires, feelings and internal experiences. Thus, the advice from external sources helped to form a kind of filter through which the mixture of internal processes passed, as the women worked toward a decision about whether or not to allow their adult children with MIHV to return home.

Choosing the Best of the Hells

Ultimately, the women perceived housing to be critically intertwined with mental health treatment. One could not occur without the other. Their reasoning held that if their child received the needed mental health treatment, their behavior would be under control and they would not be violent which would allow them to stay in the mother’s home. Alternatively, mothers felt that if their children received proper treatment, they could live on their own because they could “function more, and learn how to maintain and care for [themselves] to be independent.” According to some mothers, having a stable and safe roof over their children’s head was a form of treatment in and of itself. One woman deeply believed that her son “would be alright if he could be secure and have a place to live.” She felt that having a place to stay was therapeutic; it was exactly the thing that was needed to provide the stability to allow her child to consistently participate in treatment, to maintain a safe place to keep medication, and ultimately to enable him to work and continue living independently because his illness and behavior would be stable.

In the context of feelings and desires mixed with internal critical factors and filtered by external forces, the women wavered as they grappled with the choice of whether or not they should, would, or could provide a home for their adult child with MIHV. Choosing “yes” or choosing “no” both had unappealing qualities. For the mothers, it was a matter of choosing between what one woman termed “the best of the hells.” Neither option was desirable. Either choice had the potential to result in somebody being victimized. If the adult child was allowed home the mothers felt that they might be a victim of their child’s violence and that they could be in danger. If the adult child was not allowed home he or she might become victimized by others in some way. It was a no win decision. It was a complex decision making effort with no singular reason for choosing one undesirable option over the other.

Discussion

The children of the women in this study were all adults, and none of the mothers had a legal right to make decisions for them. Nevertheless, all mothers were actively involved in their adult children’s lives, had assumed caregiving roles, and faced the decision of “choosing the best of hells”, that is, whether or not to allow their adult children with mental illness and a history of violence to live in their homes. Regardless of which choice they made, there were consequences. Their decisions, directly or by default, determined their adult children’s housing situation. It was a frustrating dilemma and the mothers’ quality of life was affected whether or not their adult children lived with them. They could not rest knowing that their adult children were not safe. As some of the mothers became unable to allow their adult children to live with them, they felt like they were not fulfilling their role as a parent. For them, denying their adult children a place to stay felt like a denial of love. They felt they had abandoned their adult children, even if they were still involved in other ways. The mothers felt that deciding whether or not to allow their adult children to live with them was a decision either to be happy with their own living environment but feel guilty, or to be guilt-free but unhappy in their home, and in many cases unsafe if their adult children lived with them. Living a peaceful life without their adult children meant living with a guilty conscience.

Although other research has found that providing care to adult children with mental illness can provide parents with a sense of satisfaction and purpose (Schwartz & Gidron, 2002; Winefield & Harvey, 1994), the mothers in the current study did not describe their experiences living with and providing care to their adult children as rewarding. They felt an obligation to protect and care for their adult children, but that obligation was at odds with their desire to attain some of the other goals they had for themselves. The care they were providing consumed their time and energy and resulted in their own victimization when their adult children became violent. Less than a quarter of Winefield and Harvey’s (1994) sample wanted their relatives to live with them. Among those who did, almost half preferred the arrangement to avoid worse outcomes, such as medication noncompliance and their relatives’ unhappiness in other living arrangements, but not because of its intrinsic enjoyment. The adult children in our study required more intensive supervision at home and had been violent toward their mothers, which might have negated some of the satisfaction the mothers might otherwise have experienced.

The mothers of our sample felt that violence was inevitable if their adult children remained at home. At the same time, they were fearful of what might happen to their adult children if they were forced to live on the streets where they were likely to be victimized. Either way, the adult child or his or her mother was destined to be a victim. Most often, the women jeopardized their own safety, at least temporarily, by allowing their adult children to stay with them, rather than allowing their adult children to be vulnerable living in homelessness.

Not only do mothers of adult children with MIHV face challenges posed by the mere role of caregiver to individuals with mental illness, they must contend with a mental health system that is not structured to support their informal caregiving, and also live with the negative sequelae that results from this combination, such as fear, anxiety and vulnerability. Despite their desires to pursue their own activities and tend to their own needs, no respite from the mental health system is available so mothers are unable to recharge themselves to maintain their strength, ability, and desire to continue providing care for their adult children with MIHV. With the exception of caregivers of people with dementia/Alzheimer’s disease, respite care for family members of individuals with mental illness is rare despite the documented need for such supportive services for caregivers who intend to maintain their role as primary caregiver (Ward-Griffin et al., 2005; Veltman, Cameron, & Stewart, 2002). A lack of available research regarding the utility of respite for familial caregivers of individuals with mental illness (Jeon, Brodaty, & Chesterson, 2005) compounds the lack of understanding of this issue. In a literature review of respite care, Jeon and colleagues (2005) found that less than 3% of the articles published during a 35 year period (1967–2002) addressed respite and mental illnesses excluding dementia. In their review, respite care was identified as a critical area of support that decreased caregivers’ perceived burden and allowed families valuable opportunities to pursue other activities (Jeon et al., 2005).

Mothers viewed mental health treatment and housing as a single, complex issue, rather than two distinct problems for which their adult children needed assistance. While the burden of housing provision fell to them much of the time, the women in our sample did not receive any supportive services. This, in combination with their inability to care for their adult children in the context of their children’s violent behavior, resulted in some of the adult children being homeless. For some adult children of this sample, as was found with other samples (Ward-Griffin et al., 2005), inadequate placements in structured environments or poor living conditions in unstructured sites served to deepen the problems for those who were not homeless. Given these factors, it is possible that the simplest intervention would be to provide respite service to familial caregivers as part of the treatment plan for individuals with mental illness to prevent their homelessness and maintain their care in or outside of structured placement facilities. Currently, however, the provision of mental health services does not often incorporate housing as a treatment related need (Newman, 2001).

Another intervention that could have positively impacted the women and their adult children is conservatorship because it has been shown to decrease rates of hospitalization, violence, arrest, and homelessness (Lamb & Weinberger, 1992). Conservatorship can also reduce stress in families affected by mental illness because it results in stabilization and a reduction of chaos in the home (Lamb & Weinberger, 1993). Despite experiencing burden or distress and being violently victimized, the women of this sample were willing to continue taking care of their mentally ill adult children. However, they wanted their adult children to receive appropriate mental health services, services that would have been more easily available had their adult children been conserved. If some of the mothers in this sample were truly heard and their concerns were taken seriously by their children’s psychiatrists, it is possible that some of the psychiatrists would have been willing to file a petition for a conservatorship hearing. This would be an indication that the caregiving mothers’ needs had been recognized and respected. Additionally, it brings in a third neutral party, the legal system, which takes on the debate about the need for conservatorship. This removes the contentious debate from being caught between the psychiatrist and the mother and has the potential for decreasing animosity between the two parties. Involvement of the legal system might sharpen the focus onto the issue of rights, not just those of the adult with mental illness and a history of violence, but also those of the parent attempting to provide care because the mental health system is unable to do so. Taking the debate to a larger field is exactly what the women in this sample wanted because acknowledgement of their rights were so often overlooked, undervalued, and in some cases, completely erased.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a number of strengths. First, it is the only study that gives voice to the needs and experiences of a sample of mothers who assumed caregiving roles for their adult children with MIHV. This is the first time light has been shed on the complex decision making process some mothers endured when determining if their adult child with MIHV could live in their homes. Second, the interviews with all the mothers were conducted and transcribed by one person, ensuring consistency and continuity. Finally, the interviews were conducted in a face-to-face format. This allowed for immediate clarification of statements if needed. It was also compatible with the very personal and difficult subject matter.

Our study was limited by the difficulty encountered in recruiting participants to speak about a private matter that holds stigma for many people. Mental illness is considered taboo, but violence perpetrated by one’s child is an additional loaded and controversial factor. That we were able to recruit a small, convenience sample for this qualitative study is an indication of the courage of eight individual women who chose to speak about something very private, something that has the power to make them vulnerable not only emotionally and physically, but legally as well. The risks are high because the drive to protect their adult children with MIHV is so strong and because their children are so vulnerable. With a small sample limited to women under age 65 who speak English, comes insight into the experiences of a few, rather than of many. Therefore, the results cannot be widely generalized.

Conclusion

In sum, the women in this study were concerned enough for their adult children’s safety that they were, at times, willing to sacrifice their own safety by allowing their adult children to live with them despite the impending threat of violence. Although not directly examined in this study, it is possible that the refusal or rejection of placements by some of the adult children with MIHV was because they preferred living at home. However, if their mothers were willing to allow them to live at home, two services would be crucial for survival: adequate mental health treatment for the adult children and effective supportive services for the mothers so they have resources to continue caring for their adult children which could ultimately prevent their homelessness. Without these basic but crucial services, mothers will continue to face the painful dilemma of choosing between “the best of hells” and adult children will remain vulnerable and dangerous to themselves as well as to those who love them.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks dissertation committee members Nancy Anderson, MarySue Heilemann, and Sally Maliski from the UCLA School of Nursing and Doug Hollan from the UCLA Department of Anthropology for their assistance in conceptualizing and completing this research.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: A National Institute of Nursing Research Grant, 5T32 NR 07077, for Vulnerable Populations/Health Disparities Research at the UCLA School of Nursing and a Sigma Theta Tau, Gamma Tau Chapter research grant.

Biographies

Darcy A. Copeland, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor at the University of Portland, School of Nursing in Portland, Oregon, USA.

MarySue V. Heilemann, PhD, RN, is an associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Nursing, in Los Angeles, California, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Douglas C. Housing environments and community adjustment of severely mentally ill persons. Community Mental Health Journal. 1990;26(6):497–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00752454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibou-Nakou I, Dikaiou M, Baisactaris C. Psychosocial dimensions of family burden among two groups of carers looking after psychiatric patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1997;32:104–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00788928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel D, Milligan S, Putnam P, Song L. Predictors of burden among lower socioeconomic status caregivers of persons with chronic mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 1994;30(5):473–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02189064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder R, McNeil D. Victims and families of violent psychiatric patients. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 1986;14(2):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom C. Continuum of care. In: Keltner N, Hilyard Schwecke L, Bostrom CE, editors. Psychiatric Nursing. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Browne G, Courtney M. Measuring the impact of housing on people with schizophrenia. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2004;6:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2003.00172.x. Retrieved from http://0web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&hid=111&sid=1fb0ff7a-9b36-4b5f-a45b-dbcaeb616ad5%40sessionmgr114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Welfare & Institutions Code. Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, § 5350. 2009 Retrieved from http://law.onecle.com/california/welfare/5350.html. [Google Scholar]

- Champlin B. Being there for another with a serious mental illness. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(1):1525–1535. doi: 10.1177/1049732309349934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded Theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 2nd ed. @Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 249–291. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland D, Heilemann MV. Getting “to the point“: The experience of mothers getting assistance for their adult adult children who are violent and mentally ill. Nursing Research. 2008;57(3):136–143. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319500.90240.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Providing services to families of persons with schizophrenia: Present and future. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 1999;2:3–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199903)2:1<3::aid-mhp31>3.0.co;2-0. Retrieved from: http://www.icmpe.org/test1/journal/issues/v2pdf/2-003_text.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff S, Zimmer C. Social networks, social support, and violence among persons with severe, persistent mental illness. In: Monohan J, Steadman H, editors. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 259–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, Shumway M, Owen R. Priorities of consumers, providers, and family members in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(6):724–729. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.724. Retrieved from http://psychservices.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/53/6/724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine KL. Mental Health Nursing. 6th ed. @Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich R, Hollingsworth B, Hradek E, Friedrich H, Culp K. Family and client perspectives on alternative residential settings for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(4):509–514. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.509. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/50/4/509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger S, Schutt R, Tolomiczenko G, Seidman L, Penk W, Turner W, Caplan B. Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(5):674–679. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.674. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/50/5/674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A, Reinhard S. Ethnic differences in caregiving duties and burdens among parents and siblings of persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(2):138–150. Retrieved from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=7&hid=104&sid=1fb0ff7a-9b36-4b5f-a45b-dbcaeb616ad5%40sessionmgr114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon Y, Brodaty H, Chesterson J. Respite care for caregivers and people with severe mental illness: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(3):297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungbauer J, Wittmund B, Dietrich S, Angermeyer M. Subjective burden over 12 months in parents of patients with schizophrenia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2003;17(3):126–134. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(03)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H, Weinberger L. Conservatorship for gravely disabled psychiatric patients: A four-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(7):909–913. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.909. Retrieved from http://yz3ak5wb3z.search.serialssolutions.com/?genre=article&isbn=&issn=0002953X&title=The+American+Journal+Of+Psychiatry&volume=149&issue=7&date=19920701&atitle=Conservatorship+for+gravely+disabled+psychiatric+patients%3a+a+four-year+followup+study.&aulast=Lamb+HR&spage=909& pages=909-13&sid=EBSCO:MEDLINE&pid= [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H, Weinberger L. Therapeutic use of conservatorship in the treatment of gravely disabled psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(2):147–150. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Hollan D. Person-centered interviewing and observation. In: Bernard H, editor. Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press; 1998. pp. 333–364. [Google Scholar]

- Moxam L, Pegg S. Permanent and stable housing for individuals with a mental illness in the community: A paradigm shift in attitude for mental health nurses. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2000;9:82–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2000.00162.x. Retrieved from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&hid=104&sid=8f24ba9e-411a-4249-bcf7-60148915729c%40sessionmgr113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition for the Homeless. Who is homeless? NCH Fact Sheet #3. 2006a Jun; Retrieved from http://www.nationalhomeless.org/publications/facts/Whois.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition for the Homeless. Mental illness and homelessness. NCH Fact Sheet #5. 2006b Jun; Retrieved from http://www.nationalhomeless.org/publications/facts/Mental_Illness.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. Housing attributes and serious mental illness: Implications for research and practice. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(10):1309–1317. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1309. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/52/10/1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E, Danley K, Anthony W, Martin R, Walsh D. The residential needs and preferences of persons with serious mental illness: A comparison of consumers and family members. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1994;21(1):42–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02521344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. Homelessness and re-hospitalization: The importance of housing for the chronically mentally ill. Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;19:60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. Families living with severe mental illness: A literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003;24:175–198. doi: 10.1080/01612840305301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Gidron R. Parents of mentally ill adult adult children living at home: Rewards of caregiving. Health & Social Work. 2002;27(2):145–154. doi: 10.1093/hsw/27.2.145. Retrieved from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=7&hid=104&sid=8f24ba9e-411a-4249-bcf7-60148915729c%40sessionmgr113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steadman H, Mulvey E, Monahan J, Robbins P, Applebaum P, Grisso T, Silver E. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393–405. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.393. Retrieved from http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/55/5/393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Straznickas K, McNeil D, Binder R. Violence toward family caregivers by mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(4):385–387. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streubert Speziale H, Rinaldi Carpenter D. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stroul B. Community support systems for people with long-term mental illness: A conceptual framework. Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 1989;12:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, Vine P, Struening E. Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: Comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(2):199–209. doi: 10.1037/h0080223. Retrieved from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=9&hid=104&sid=8f24ba9e-411a-4249-bcf7-60148915729c%40sessionmgr113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzman B. An overview of surveys of mental health consumers’ preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(5):450–455. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff K, Marzuk P, Leon A, Portera L. A prospective study of violence by psychiatric patients after hospital discharge. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48(5):678–681. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.5.678. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/48/5/678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urff J. Public mental health systems: Structures, goals, and constraints. In: Levin B, Petrila J, Hennessy K, editors. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman A, Cameron J, Stewart D. The experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190(2):108–114. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200202000-00008. Retrieved from http://yz3ak5wb3z.search.serialssolutions.com/?genre=article&isbn=&issn=00223018&title=The+Journal+Of+Nervous+And+Mental+Disease&volume=190&issue=2&date=20020201&atitle=The+experience+of+providing+care+to+relatives+with+chronic+mental+illness.&aulast=Veltman+A&spage=108&pages=10814&sid=EBSCO:MEDLINE&pid= [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C, Schofield R, Vos S, Coatsworth-Puspoky R. Canadian families caring for members with mental illness: A vicious cycle. Journal of Family Nursing. 2005;11(2):140–161. doi: 10.1177/1074840705275464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasow M. The need for asylum revisited. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(3):207–208. 222. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winefield H, Harvey E. Needs of family caregivers in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1994;20(3):557–566. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.557. Retrieved from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.clark.up.edu/ehost/pdfviewer /pdfviewer?vid=15&hid=104&sid=8f24ba9e-411a-4249-bcf7-60148915729c%40sessionmgr113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A, Magnabosco J. Services for adults with mental illness. In: Levin B, Petrila J, Hennessy K, editors. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 177–208. [Google Scholar]