Abstract

Ventricular assist device patients (VAD) are at increased risk for thromboembolism. Biomarkers of hemolysis, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and poorly controlled INR has been identified as predictors of thromboembolism.

Patients aged 19 years and older who had a continuous flow VAD placed from 2006–2012 were included in this study (N=115). We assessed the relationship of LDH elevation (≥ 600 IU/L) at different time points and thromboembolism. Over the 51.3 person-years of follow-up, a total of 23 first thromboembolic events occurred. Patients with elevated LDH on the day of VAD implantation had an increased risk for thromboembolism (HR 4.72, 95% CI 1.44–15.4, p=0.01). There was an increased risk of thromboembolism with early LDH elevation within the first month post VAD (HR 4.95, 95%CI 1.69–14.4, p=0.003) and eGFR <30 prior to VAD implantation (HR 4.74, 95%CI 1.12–20.1, p=0.0346) while there was a decreased risk with good anticoagulation control (HR 0.30, 95%CI 0.10–0.86, p=0.0247).

Our study is the first to highlight the association between LDH elevation on the day of implantation and post VAD thromboembolism. This study details the increased risk of thromboembolism with early LDH elevation and the importance of maintaining time in therapeutic INR range.

Keywords: Thromboembolism, Ventricular Assist Device, risk factor, lactate dehydrogenase

The incidence of thromboembolism in VAD patients, particularly pump thrombosis, is a serious concern as has been highlighted in recent reports.1, 2 While VAD patients are initiated on chronic warfarin therapy, there is limited data on the relation between degree of anticoagulation control achieved and outcomes in these high-risk patients. Anticoagulation control is commonly assessed by measuring percent time spent in target range (PTTR) with PTTR ≥60% being considered good anticoagulation control. Achieving PTTR≥60% is the goal of anticoagulation management as it has been shown to minimize the risk of hemorrhage and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation.3–5 Despite the intense antithrombotic regimen, VAD patients remain at high risk for thromboembolic events, contributing to the morbidity and mortality in VAD patients.

Risk factors for thromboembolism post-VAD implant include impaired renal function, increased BMI, pre-operative atrial fibrillation, and international normalized ratio (INR) measurements below 1.5.2, 6,7 In populations at high risk for thromboembolism, such as patients with atrial fibrillation, risk scores such as the CHADS2 score (which assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75, diabetes and 2 points for prior history of stroke, transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism) and the CHA2DS2-VASc score (which assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, age 65–74, and female sex and 2 points each for age ≥ 75 and history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism) are widely used to assess risk of thromboembolism.8, 9

While these risk scores are informative in patients requiring chronic anticoagulation, their predictive ability has not been assessed in patients with VADs. Moreover, additional risk factors may need to be considered in VAD patients. As hemolysis is a harbinger of pump thrombosis, biomarkers associated with hemolysis can serve as an early warning for impending pump thrombosis.10 Elevation of one such marker, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), has been associated with increased risk of pump thrombosis.11 However, these investigations have been limited to cross-sectional assessments of LDH. Furthermore, while previous investigations have considered the INR at the time of a thromboembolic event in VAD patients, no study has accounted for anticoagulation control (PTTR) in the assessment of thromboembolism in VAD patients.2, 6,7 Herein, we assess the ability of the CHADS2 and the CHA2DS2-VASc score in predicting thromboembolism among VAD patients, assess the influence of PTTR on thromboembolic risk, evaluate the change in LDH over a 1-year follow-up, and assess the relationship between LDH and thromboembolism.

Methods

Study Setting and Inclusion and Exclusion

This study was conducted at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) under the approval of the Institutional Review Board. Consecutive patients aged 19 years and older who had a continuous flow VAD (HeartMate II (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA) or HeartWare (HeartWare Inc, Framingham, MA) device) placed at UAB from 2006–2012 were included in this study. Patients were followed for 1-year post VAD implantation to assess outcomes. Loss to follow up was minimal since both inpatient and outpatient care occurred at UAB with routine clinic visits at least monthly.

Data collection

For all patients, a detailed baseline (pre-VAD) clinical phenotype including demographics (e.g. gender, race, ethnicity etc.), medical history before VAD (e.g. co-morbidities, surgeries prior to VAD implant etc.), medications (e.g. antithrombotic medications), and laboratory assessments (e.g. LDH, kidney function tests etc.) was documented through retrospective medical record review. Post-VAD data including medications, laboratory assessments and outcomes was obtained through medical records review using definitions established by the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) Registry.12

Risk Factors for Thromboembolism

We also evaluated the influence of diabetes, atrial fibrillation, CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, decreased kidney function and PTTR on risk of thromboembolism. The thromboembolism risk scores, CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc, were evaluated as continuous variables and categorized into dichotomous risk groups.8, 9 The CHADS2 score was categorized into moderate risk (CHADS2 ≥ 1) compared to high risk (CHADS2 ≥ 2). The CHA2DS2-VASc score was categorized as moderate risk (CHA2DS2-VASc ≤3) compared to severe risk (CHA2DS2-VASc ≥4).

Kidney function was assessed through the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Formula (CKD-EPI)13 which incorporates gender, race, age, and serum creatinine (Scr; mg/dL). Kidney function was characterized with eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 considered to be no/mild kidney disease (CKD stage 1, 2); those with eGFR =30–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 (CKD stage 3) considered to be moderate kidney disease and those with eGFR<30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (or on dialysis) considered to be severe kidney disease (CKD stage 4, 5).14, 15

Amongst patients on warfarin, the proportion of time spent in target INR range (PTTR) was estimated for each patient using the Rosendaal linear interpolation method.16 This method, which assumes a linear relationship exists between two consecutively measured INR values, allows one to allocate a specific INR value to each day for each patient. Time in target range for each patient was assessed by the percentage of interpolated INR values within the target range of 2.0–3.0 after attainment of first INR in target range. We also assessed proportion of time spent in extended target range (PTTRe; INR1.8–3.2) since deviations beyond this range usually trigger dose adjustments to minimize the increased risk of thrombosis and hemorrhage. PTTRe was categorized into Good control>60%, Moderate control 50<60% and Poor control <50%.17

LDH Monitoring and Assay

Lactate dehydrogenase was measured in VAD patients on the day of VAD implantation prior to surgery, and then 2 weeks ± 2 days, 1 month ± 2 days, 3 months ± 7 days, 6 months ± 7 days, 9 months ± 7 days and 12 months ± 7 days after VAD implantation. All samples were collected from a peripheral blood draw with special attention to specimen handling to avoid hemolysis. LDH levels were assessed by an enzymatic rate method, 18 that measures the change in absorbance at 340 nanometers (Beckman Coulter DCX 800 pro with SYNCHRON system, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA) which is directly proportional to the activity of LDH in the sample. For adults, the reference range at UAB hospital laboratories is 120–240 IU/L for LDH. Based on the previously reported sensitivity and specificity of LDH as a predictor of thromboembolism, we defined elevated LDH as ≥ 600 IU/L, which is consistent with prior studies on LDH levels in VAD populations.11, 19

Definition of Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was any thromboembolic event, defined as pump thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, deep vein thrombosis and ischemic stroke. As some patients experienced multiple events within the 1-year follow-up period, only the first event was included in the analysis. We also assessed predictors of early thromboembolic (occurring within the first 30 days post-VAD implant) and late thromboembolism (occurring after 30 days post-VAD implant) event.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test of independence was used to assess group differences for baseline demographic categorical variables and Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to compare the ability of the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc score (as a continuous variable) to predict thromboembolism using the area under the curve (AUC). Kaplan-Meier curves with log rank tests were used to assess time to thromboembolic event. Cox-proportional hazard modeling was conducted to evaluate the association of predictors on risk of thromboembolism. Patients were censored at the time of the first hemorrhage event, explantation (due to death, recovery or transplant) or at 1 year after VAD implantation. Due to a small number of patients implanted with a HeartWare device we did not stratify on device type.

Repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess change in LDH over time among patients who experienced vs. did not experience thromboembolism. As early elevation of LDH (within the first month) is considered a risk factor for pump thrombosis, patients exhibiting elevation at VAD implantation, 14 days post implantation or 1 month post implantation were categorized as Early LDH Elevation. 14 Only LDH measurements prior to early thromboembolic events were included. Patients without this measurement were excluded from the analyses (N=18). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) at a non-directional alpha of 0.05.

Results

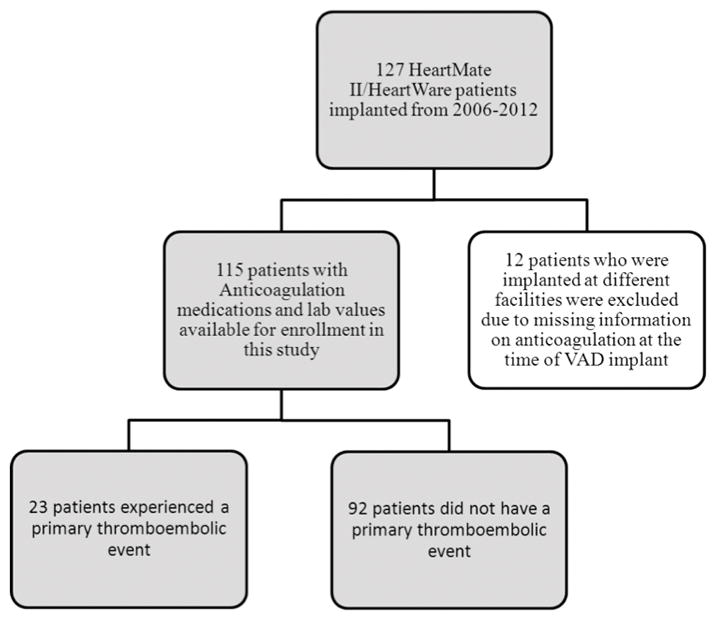

Of the sample of 127 patients with continuous flow VAD implants at treated at UAB between 2006 and 2012, a total of 115 patients with HeartMate II (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA) or HeartWare (HeartWare Inc, Framingham, MA) devices were included in this study (Figure 1). Twelve patients implanted outside UAB were excluded as early data on anticoagulant control and warfarin dosing was not available. The mean age at implant was 52 years (±14.6), and the majority of patients were male (78.3%), white (67.8%) and implanted as a bridge to transplant (56.6%; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Used to Establish the Cohort

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics for the Entire Cohort Stratified by Thromboembolism

| All Patients (N=115) | No Thromboembolism (N=92) | Thromboembolism (N=23) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age at Implant | 52± 15 | 53 ±14 | 49 ±15 | 0.20 |

| Body Mass Index at Implant | 28 ± 8 | 29±7 | 29±7 | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Male | 90 (78.3%) | 74 (80.4%) | 16 (69.6%) | 0.26 |

| Black Race | 37 (32.2%) | 29 (31.5%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.76 |

| Status in the first year | 0.50 | |||

| Deceased | 19 (16.5%) | 13 (14.1%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Transplanted | 23 (20.0%) | 20 (21.7%) | 3 (13.0%) | |

| Recovered | 4 (3.5%) | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Etiology of Heart Failure | 0.25 | |||

| Ischemic | 60 (53.1%) | 50 (55.5%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| Idiopathic | 45 (39.8%) | 35 (38.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| Indication for VAD | 0.14 | |||

| Bridge to transplant | 64 (56.6%) | 49 (54.5%) | 15 (65.2%) | |

| Bridge to candidacy | 2 (1.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 | |

| Bridge to recovery | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Destination | 46 (40.7%) | 39 (43.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| Comorbid Conditions | ||||

| Diabetes | 45 (39.1%) | 40 (43.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.031 |

| Right Ventricular Dysfunction | 28 (24.4%) | 21 (22.8%) | 7 (30.4%) | 0.45 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 46 (40.0%) | 37 (40.2%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.92 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 23 (20.0%) | 19 (20.7%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.73 |

| Hypertension | 71 (61.7%) | 59 (64.1%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.29 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 43 (37.4%) | 44 (47.8%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.26 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 26 (22.6%) | 39 (42.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.016 |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | 19 (16.5%) | 45 (48.9%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.64 |

| Concurrent Meds at VAD Implantation | ||||

| Warfarin | 115 (100%) | 92 (100%) | 23 (100%) | - |

| Aspirin | 113 (98.2%) | 90 (97.8%) | 23 (100%) | 0.48 |

| Plavix | 67 (58.3%) | 53 (57.6%) | 14 (60.9%) | 0.78 |

| Colchicine | 6 (5.2%) | 5 (5.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.84 |

| Amiodarone | 70 (60.9%) | 54 (58.7%) | 16 (69.6%) | 0.34 |

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration rate (eGFR ml/min/1.73m2) prior to VAD implantation | 0.014 | |||

| eGFR ≥60 | 47 (42.3%) | 40 (44.4%) | 7 (33.3%) | |

| eGFR 30 to 59 | 54 (48.7%) | 44 (48.9%) | 10 (47.6%) | |

| eGFR < 30 | 10 (9.0%) | 6 (6.7%) | 4 (19.1%) | |

| CHADS2 Score | 0.75 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 25 (21.7%) | 18 (19.6%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| 2 | 51 (44.3%) | 41 (44.6%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| 3 | 34 (29.6%) | 29 (31.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| 4 | 4 (3.5%) | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (4.4%) | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 | |

| CHADS2 Category | 0.26 | |||

| CHADS2 <2 | 25 (21.7%) | 18 (19.6%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| CHADS2 ≥2 | 90 (78.3%) | 74 (80.4%) | 16 (69.6%) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 0.94 | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 17 (14.8%) | 13 (14.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | |

| 3 | 38 (33.0%) | 30 (32.6%) | 8 (34.8%) | |

| 4 | 38(33.0%) | 30 (32.6%) | 8 (34.8%) | |

| 5 | 17 (14.8%) | 15 (16.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| 6 | 4 (3.5%) | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (4.4%) | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Category | 0.64 | |||

| CHA2DS2-VASc <4 | 55 (47.8%) | 43 (46.7%) | 12 (52.2%) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc ≥4 | 60 (52.2%) | 49 (53.3%) | 11 (47.8%) | |

Of the 115 patients in this study, 23 (20%) experienced a thromboembolic event during the first year, with 11 thromboembolic events occurring within the first 30 days post-VAD implant. Patients experiencing thromboembolic events within the first year were less likely to have diabetes (21.7% vs 43.5%, p=0.031), atrial fibrillation (17.4% vs 42.4%, p=0.016) and more likely to have poor kidney function (eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2; 19.1% vs 6.7%, p=0.0136) at VAD implantation.

The 115 patients contributed 51.3 person years of follow-up time. Patients were seen at least once a month, with an average of 1.4 (± 0.96) visits per patient per month (Table 2). Anticoagulation control (PTTR) was similar between patients with and without thromboembolism regardless of whether the target INR range (2–3) was used or the extended INR range (1.8–3.2). At the time of thromboembolic event, the average INR was 2.4 (SD 0.91). INR was sub-therapeutic among 4 patients at the time of the event.

Table 2.

Anticoagulation Control for the Entire Cohort and Stratified by Thromboembolic Events using an INR range of 2–3 and an INR range of 1.8–3.2

| All | No Thromboembolism | Thromboembolism | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Number of Patients | 115 | 92 | 23 | |

| Number of Visits | 4902 | 4311 | 591 | 0.003 |

| Total Follow Up (months)* | 624.5 | 569.6 | 54.9 | <0.0001 |

| Follow Up Months/patient | 5.4 ± 4.8 | 8.4 ±4.5 | 2.4 ±2.8 | <0.0001 |

| Number of Visits/patient/month | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ±0.91 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Anticoagulation control for INR Range of 2–3 | ||||

| Percent Time Below Range | 41.6 ± 28.4 | 41.8±25.9 | 42.7±36.7 | 0.46 |

| Percent Time In Range | 42.9 ± 22.5 | 43.6 ±20.4 | 42.2±28.9 | 0.95 |

| Percent Time Above Range | 15.8 ± 13.9 | 15.1±12.1 | 18.5±19.4 | 0.93 |

| Anticoagulation Control for INR Range of 1.8–3.2 | ||||

| Percent Time Below Range | 30.3 ± 28.5 | 29.1 ±26.9 | 35.5 ±34.5 | 0.77 |

| Percent Time In Range | 59.2 ± 26.4 | 61.1±24.1 | 54.6±32.2 | 0.61 |

| Percent Time Above Range | 11.1 ± 11.5 | 10.5±9.7 | 13.8±16.9 | 0.92 |

Follow-up is calculated as time from VAD to first event, or in the circumstance of no event the end of study period (1 year), explantation, transplantation or death

Risk Factors for Thromboembolism

Over the 51.3 person-years of follow-up (Table 3), a total of 23 thromboembolic events were encountered (Incidence Rate [IR] 4.5 events per 10 patient years, 95% CI 29.1–66.2). Despite the difference in proportions, neither diabetes (HR 0.44, 95%CI 0.16–1.19, p=0.11), nor atrial fibrillation (HR 0.36, 95%CI 0.12–1.05, p=0.06) were significantly associated with thromboembolism when using time to event analyses. The CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were only marginally predictive of thromboembolism with an AUC of 0.572 and 0.544, respectively. When evaluated as a continuous variable neither the CHADS2 score (HR 0.82, 95%CI 0.50–1.34, p=0.42), nor the CHA2DS2-VASc (HR 0.91, 95%CI 0.63–1.31, p=0.61) score were associated with risk of thromboembolism. Neither the categorical CHADS2 score variable (CHADS2 score ≥2; HR 0.70, 95%CI 0.29–1.71, p=0.44) nor the categorized CHA2DS2-VASc score variable (CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 4; HR 0.89, 95%CI 0.39–2.02, p=0.78) were associated with the risk of thromboembolism.

Table 3.

Incidence of Thromboembolic Events in the First Year after Implantation

| N | Follow-up* | Incidence Rate (IR) (95%Confidence Interval (CI)) per 10 person years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All cause TE | |||

|

| |||

| Entire Sample (N=115) | 23 | 51.3 years | 4.5 (2.9–6.6) |

|

| |||

| TE Type | |||

| Ischemic Stroke | 6 | 51.3 years | 1.2 (0.5–2.4) |

| Pump Thrombosis | 6 | 51.3 years | 1.2 (0.5–2.4) |

| DVT | 5 | 51.3 years | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) |

| TIA | 2 | 51.3 years | 0.4 (0.07–1.3) |

| PE | 2 | 51.3 years | 0.4 (0.07–1.3) |

| Mediastinal Clot | 2 | 51.3 years | 0.4 (0.07–1.3) |

Follow-up is calculated as time from VAD to first event, or in the circumstance of no event the end of study period (1 year), explantation, transplantation or death

Patients with an eGFR <30ml/min/1.73m2 at baseline had an increased risk for thromboembolism (unadjusted HR 3.65, 95%CI 1.06–12.5, p=0.040; Table 4) as did patients who achieved poor anticoagulation control (PTTR<50%; unadjusted HR 2.91, 95%CI 1.18–7.14, p=0.0201; Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of Elevated LDH within the first month post VAD implantation and Risk (Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% Confidence interval (95%CI)) of Thromboembolism

| Crude Analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| No early LDH Elevation (<600 IU/L) | ref | ref | ref |

| Early LDH Elevation(≥600 IU/L) | 2.99 | 1.14–7.88 | 0.027 |

|

| |||

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration rate (eGFR ml/min/1.73m2) prior to VAD implantation | |||

| eGFR ≥60 | ref | ref | ref |

| eGFR 30 to 59 | 1.56 | 0.59–4.12 | 0.36 |

| eGFR < 30 | 3.65 | 1.06–12.5 | 0.040 |

|

| |||

| Anticoagulation Control | |||

| Good Control | ref | ref | ref |

| Moderate Control | 0.43 | 0.06–3.34 | 0.43 |

| Poor Control | 2.91 | 1.18–7.14 | 0.020 |

| Adjusted Analyses* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| No early LDH Elevation (<600 IU/L) | ref | ref | ref |

| Early LDH Elevation(≥600 IU/L) | 4.95 | 1.69–14.4 | 0.003 |

|

| |||

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration rate (eGFR ml/min/1.73m2) prior to VAD implantation | |||

| eGFR ≥60 | ref | ref | ref |

| eGFR 30 to 59 | 1.12 | 0.37–3.37 | 0.83 |

| eGFR < 30 | 4.74 | 1.12–20.1 | 0.035 |

|

| |||

| Anticoagulation Control | |||

| Good Control | ref | ref | ref |

| Moderate Control | 0.30 | 0.04–2.55 | 0.27 |

| Poor Control | 3.36 | 1.17–9.66 | 0.025 |

The full model includes early LDH elevation, eGFR at VAD implantation and anticoagulation control

Change in LDH over the Follow-up Period

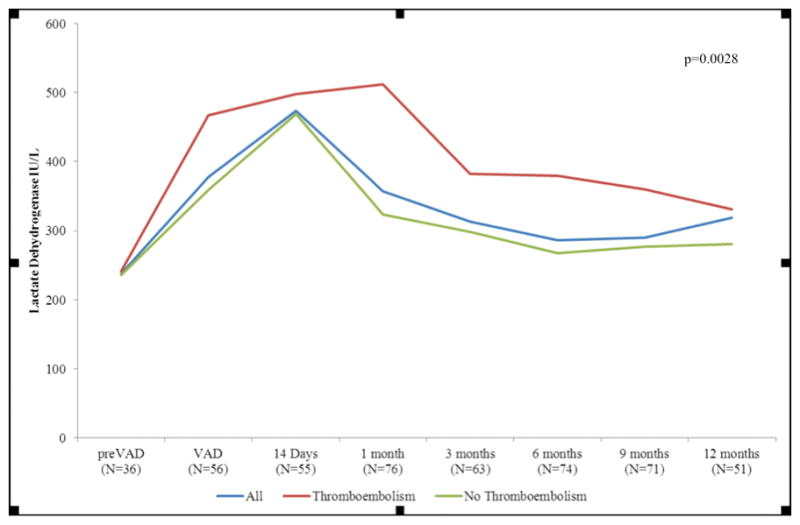

LDH was elevated in 7 (12.5%) of 56 patients who had an LDH measurement pre-VAD implantation and in 17 (17.5%) of 97 patients who had an early LDH measurement within the first month post-implantation. As illustrated in Figure 2, the mean LDH increases over the first14 days. Patients with a thromboembolic event continued to have a higher mean LDH post-implant than those without a thromboembolic event, and this pattern remained throughout the follow-up after the thromboembolic event (p=0.0028).

Figure 2.

Change in LDH Over Time for the Entire Cohort and Stratified by Thromboembolism

LDH and all thromboembolic events

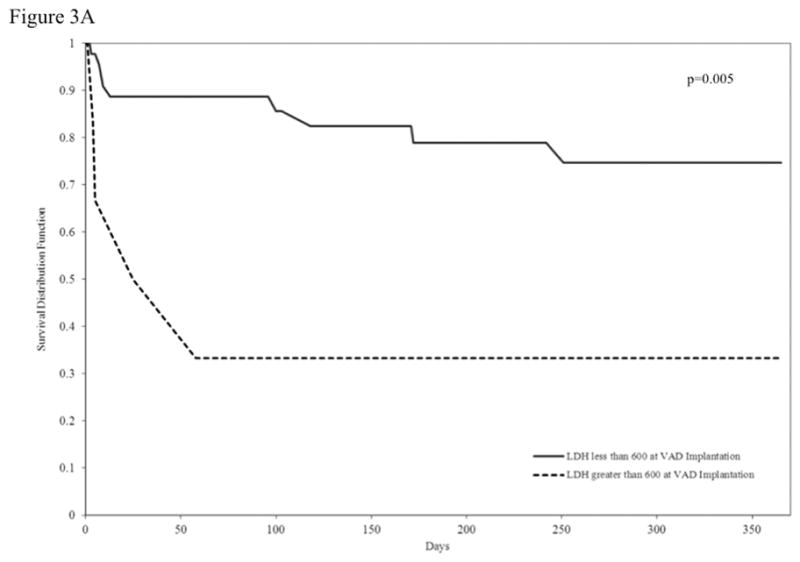

Patients with elevated LDH at VAD implantation experienced a shorter time to thromboembolism (p=0.0046; Figure 3a), and a 4.7 fold increase in risk for thromboembolism (HR 4.72, 95% CI 1.44–15.4, p=0.0103). Furthermore, elevated LDH at VAD implantation was associated with an increased risk of early thromboembolism (HR 5.55, 95%CI 1.32–23.3, p=0.0193). Although elevated LDH at VAD implantation increased the risk of late thromboembolism, this association was not statistically significant (HR 3.37, 95%CI 0.37–30.3, p=0.28).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Kaplan Meier Curve Illustrating Time to Thromboembolism Stratified by Elevated LDH at VAD Implantation

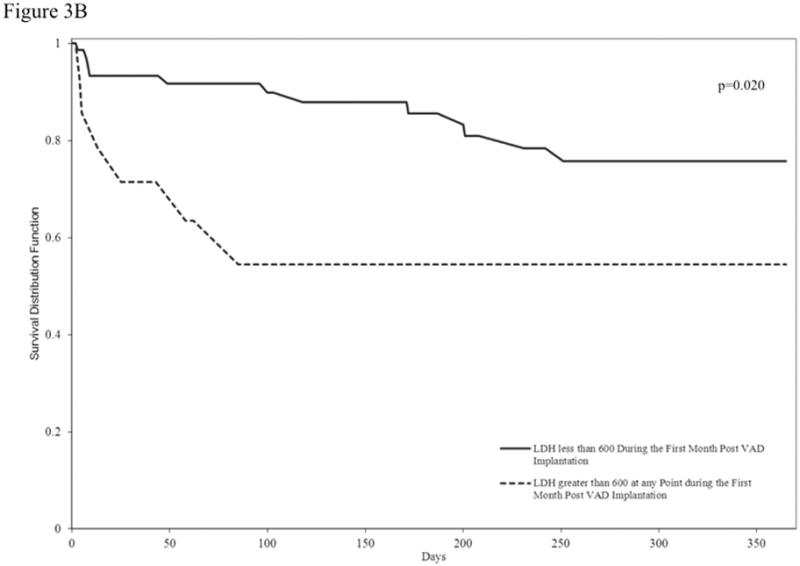

Figure 3b. Kaplan Meier Curve Illustrating Time to Thromboembolism Stratified by Early LDH Elevation

Patients with Early LDH Elevation (within 30 days) experienced a shorter time to thromboembolic events (Figure 3b; p=0.0198) and a 2.9 fold increase in risk for thromboembolism (HR 2.99, 95% CI 1.14–7.88, p=0.027; Table 4). Early LDH Elevation was associated with risk of late thromboembolism (HR 6.38, 95%CI 1.32–30.8, p=0.021).

As LDH was recently reported to increase the risk of pump thrombosis and ischemic stroke, we assessed the association of LDH and these events. During the 51.3 person years of follow-up the average time to first ischemic stroke was 118 days among the 6 patients with ischemic stroke (IR 11.7 events/100 patient years, 95% CI 4.7–24.3). Patients with LDH elevation at time of VAD implant were at an increased risk of ischemic stroke (HR 19.8, 95%CI 1.79–218, p=0.0148) as were patients with Early LDH Elevation (HR 6.6, 95%CI 1.37–32.8, p=0.0211). There were 6 pump thrombosis events during the 51.3 person years of follow-up (IR 11.7 events/100 patient years; 95% CI 4.7–24.3) with an average time to a first pump thrombosis 64 days. Patients with LDH elevation at time of VAD implant had an increased risk of pump thrombosis (HR 18.7, 95%CI 1.68–208, p=0.0172), as were patients with Early LDH Elevation (HR 9.6, 95%CI 1.6–57.5, p=0.0134).

The influence of LDH elevation, poor anticoagulation control and poor kidney function on risk of thromboembolism remained consistent in multivariable analysis (Table 4). After adjustment for these factors, elevated LDH (HR 4.95, 95%CI 1.69–14.4, p=0.003), poor kidney function (eGFR <30ml/min/1.73m2 HR 4.74, 95%CI 1.12–20.1, p=0.035) and poor anticoagulation control PTTR<50%; HR 3.36, 95%CI 1.17–9.66, p=0.025) were associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism.

Discussion

The concerning increase in the rate of thromboembolism in VAD patients with newer devices illustrates the need to identify patients at high risk of a thromboembolic event.2 The ability to detect a subgroup at high risk could enable clinicians to more stringently monitor and potentially prevent thromboembolism in these patients. Our study is the first to highlight the association between kidney function, anticoagulation control and early LDH elevation on thromboembolism. We found that patients with poor kidney function prior to VAD implant and early LDH elevation at VAD implantation are at a high risk of thromboembolism. Furthermore, we demonstrated that early LDH elevation was also associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke and pump thrombosis. Consistent with the anticoagulation literature, poor anticoagulation control (PTTR <50%) was associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism.17

Previously described risk factors for thromboembolism in VAD patients include history of diabetes, increased BMI and a history of atrial fibrillation; 2, 7 however, these factors were not statistically significantly associated with thromboembolism in our study. Furthermore, we assessed the ability of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores to predict thromboembolic risk in this high-risk patient population.8, 9 We found there was no significant relationship between these scores and risk of thromboembolism in VAD patients. This may be explained by the high risk/high disease burden in most of the patients.

Kidney function is a known risk factor for thromboembolism with an increased risk of thromboembolism for patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2.20 Chronic kidney disease is associated with an enhanced procoagulant profile; higher levels of fibrinogen, Factor VIII and vWF.21 Although, kidney function improves after VAD implantation due to improved perfusion, the association poor kidney function and thromboembolism in our study may signify the damage due to long-term under-perfusion sustained prior to VAD implant, in addition to the increased procoagulant profile.22, 23

Poor anticoagulation control was associated an increased risk of thromboembolism. Four thromboembolic events occurred at an INR below 1.5, with 2 events (mediastinal clots) occurring within 2 days after VAD implant while being treated with heparin. This could be due to clinically non-apparent fibrin deposits on the pump that occur during periods of suboptimal anticoagulation. Embolism resulting from dislodged deposits can lead to a thromboembolic event. This finding suggests that more emphasis should be place on early anticoagulation control to prevent the buildup of these fibrin deposits.

Although the dynamic hemostatic environment post VAD implant contributes to considerable variability in coagulation and fibrinolysis markers, 24 the biomarker LDH, as a sensitive predictor of hemolysis, has been associated with increased embolic events in VAD patients.11, 19 Our study is the first to assess LDH elevation prior to VAD implant as well as early LDH elevation as a primary predictor of thromboembolism, ischemic stroke and pump thrombosis.

The association between elevated LDH at the time of VAD implant with thromboembolism and ischemic stroke identified in our study has not been previously described. Prior studies in VAD patients have not analyzed LDH at the time of implantation and thromboembolic events, but rather the relationship of LDH elevation post-VAD and these events. The association between LDH and ischemic or embolic stroke has not been described in the general stroke literature either, likely because LDH is not a marker routinely measured in this population. Our observation, although not previously described, does have biologic plausibility. First, LDH itself is a non-specific enzyme and has five isoforms, which come from many sources including the heart, lungs, liver, kidney and reticuloendothelial system. Second, elevated LDH could be a marker of tissue breakdown due to cell injury with resultant fibrin clot formation; this would affect platelet function (and theoretically thromboembolic risk) prior to VAD implantation.25 This phenomenon could certainly be observed in advanced heart failure patients, where hypoperfusion could result in cell injury within the heart, lungs, spleen, kidneys and liver, thereby increasing LDH levels. Our finding suggests that LDH elevation prior to implant could be used to identify those at already at higher risk thromboembolism post-implant and warrants further study.

Furthermore, consistent with previous studies, elevated LDH at 1-month post implant was associated with late thromboembolic events.2 Using pre-VAD or early LDH elevation can enable identification of patients at highest risk for developing hemolysis or a thromboembolism enabling different or more stringent medical treatment strategies. The mean LDH remained higher over time for patients with a thromboembolic event than for patients without a thromboembolic event, even after the event occurred. This highlights the importance of regular LDH surveillance in the long-term management of VAD patients.

We recognize limitations of our study including inclusion of participants from a single center and inclusion of patients with HeartMate II and HeartWare devices. However this allowed us to minimize heterogeneity related to device technology and clinical care delivery. There was a low frequency of thromboembolic events. In addition we did not assess serum free hemoglobin and therefore cannot demonstrate its association with LDH. Among VAD patients, the routine assessment of LDH measurement was introduced in 2006 at our institution. Therefore we could not include patients who received their VAD prior to 2006. Further research is needed to assess if other factors such as early heparin bridging, primary hypercoagulable states, pump speed/pulsatility or specific devices are associated with increased risk of thromboembolism in VAD patients.

Our study is the first to highlight the association between LDH and thromboembolism in VAD patients. Furthermore, we identified poor kidney function at baseline and poor anticoagulation control post-VAD as significant risk factors for thromboembolism. These findings need to be confirmed in larger independent cohorts of VAD patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work is supported in part by American Heart Association (Award number 13PRE13830003) and the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (RO1 HL092173). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHA. Dr. Levitan has received research support from Amgen, Inc., for unrelated projects.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Starling RC, Moazami N, Silvestry SC, Ewald G, Rogers JG, Milano CA, Rame JE, Acker MA, Blackstone EH, Ehrlinger J, Thuita L, Mountis MM, Soltesz EG, Lytle BW, Smedira NG. Unexpected abrupt increase in left ventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:33–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, Pagani FD, Myers SL, Stevenson LW, Acker MA, Goldstein DL, Silvestry SC, Milano CA, Timothy Baldwin J, Pinney S, Eduardo Rame J, Miller MA. Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) analysis of pump thrombosis in the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2014;33:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Dalen J, Bussey H, Anderson D, Poller L, Jacobson A, Deykin D, Matchar D. Managing oral anticoagulant therapy. Chest. 2001;119:22S–38S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.22s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansell J, Hollowell J, Pengo V, Martinez-Brotons F, Caro J, Drouet L. Descriptive analysis of the process and quality of oral anticoagulation management in real-life practice in patients with chronic non-valvular atrial fibrillation: the international study of anticoagulation management (ISAM) J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2007;23:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-9022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hylek EM, Skates SJ, Sheehan MA, Singer DE. An analysis of the lowest effective intensity of prophylactic anticoagulation for patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:540–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle AJ, Russell SD, Teuteberg JJ, Slaughter MS, Moazami N, Pagani FD, Frazier OH, Heatley G, Farrar DJ, John R. Low thromboembolism and pump thrombosis with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device: analysis of outpatient anti-coagulation. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2009;28:881–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stulak JM, Deo S, Schirger J, Aaronson KD, Park SJ, Joyce LD, Daly RC, Pagani FD. Preoperative atrial fibrillation increases risk of thromboembolic events after left ventricular assist device implantation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96:2161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gage BF, van Walraven C, Pearce L, Hart RG, Koudstaal PJ, Boode BS, Petersen P. Selecting patients with atrial fibrillation for anticoagulation: stroke risk stratification in patients taking aspirin. Circulation. 2004;110:2287–92. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145172.55640.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah P, Mehta VM, Cowger JA, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD. Diagnosis of hemolysis and device thrombosis with lactate dehydrogenase during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowger JA, Romano MA, Shah P, Shah N, Mehta V, Haft JW, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD. Hemolysis: a harbinger of adverse outcome after left ventricular assist device implant. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2014;33:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Schryver EL, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Algra A. Non-adherence to aspirin or oral anticoagulants in secondary prevention after ischaemic stroke. J Neurol. 2005;252:1316–21. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valente MA, Hillege HL, Navis G, Voors AA, Dunselman PH, van Veldhuisen DJ, Damman K. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation outperforms the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate in chronic systolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:86–94. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang SM, Temple R, Xiao S, Zhang L, Lesko LJ. When to conduct a renal impairment study during drug development: US Food and Drug Administration perspective. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:475–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansell J. New oral anticoagulants should not be used as first-line agents to prevent thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;125:165–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.031153. discussion 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amador E, Dorfman LE, Wacker WE. Serum Lactic Dehydrogenase Activity: An Analytical Assessment of Current Assays. Clin Chem. 1963;12:391–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah P, Mehta VM, Cowger JA, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD. Diagnosis of hemolysis and device thrombosis with lactate dehydrogenase during left ventricular assist device support. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2014;33:102–4. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wattanakit K, Cushman M, Stehman-Breen C, Heckbert SR, Folsom AR. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:135–40. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubin R, Cushman M, Folsom AR, Fried LF, Palmas W, Peralta CA, Wassel C, Shlipak MG. Kidney function and multiple hemostatic markers: cross sectional associations in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Coresh J, Macleod B, Salem DN, Griffith JL, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes in the elderly. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1121–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler J, Geisberg C, Howser R, Portner PM, Rogers JG, Deng MC, Pierson RN., 3rd Relationship between renal function and left ventricular assist device use. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;81:1745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majeed F, Kop WJ, Poston RS, Kallam S, Mehra MR. Prospective, observational study of antiplatelet and coagulation biomarkers as predictors of thromboembolic events after implantation of ventricular assist devices. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:147–57. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar R, Beguin S, Hemker HC. The effect of fibrin clots and clot-bound thrombin on the development of platelet procoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:962–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]